Abstract

During differentiation of precursor cells into their destination cell type, cell fate decisions are enforced by a broad array of epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, which is reflected by the transcriptome. Thus, regulatory dendritic cells (DCregs) acquire specific epigenetic programs and immunomodulatory functions during their differentiation from monocytes. To define the epigenetic signature of human DCregs generated in vitamin D3 (vitD3) and IL-10 compared to immune stimulatory DCs (sDCs), we measured levels of DNA methylation by whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS). Distinct DNA methylation patterns were acquired by DCregs compared to sDCs. These patterns were located mainly in transcriptional regulatory regions. Associated genes were enriched in STAT3-signaling and valine catabolism in DCregs; conversely, pro-inflammatory pathways, e.g. pattern recognition receptor signaling, were enriched in sDCs. Further, DCreg differentially-methylated regions (DMRs) were enriched in binding motifs specific to the immunomodulatory transcription factor Krueppel-like factor 11 (KLF11), while activator protein-1 (AP-1) (Fos:Jun) transcription factor-binding motifs were enriched in sDC DMRs. Using publicly-available data-sets, we defined a common epigenetic signature shared between DCregs generated in vitD3 and IL-10, or dexamethasone or vitD3 alone. These insights may help pave the way for design of epigenetic-based approaches to enhance the production of DCregs as effective therapeutic agents.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Immunology, Gene regulation in immune cells, Innate immune cells

Introduction

The immune system is endowed with the capacity to maintain self-tolerance and to dampen undesired inflammatory responses in disease settings. This can be achieved via a wide range of immunoregulatory cell types, including regulatory T cells (Tregs)1 and B cells (Bregs)2, erythroid CD71+ cells3, and regulatory myeloid cells, i.e. regulatory DCs (DCregs)4, regulatory macrophages (Mregs)5 and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [MDSCs]6.

Monocyte derived-DCregs, maturation-resistant or “alternatively-activated” DCs generated from monocyte precursors4,7, are characterized by specific immunomodulatory functions. For instance, compared to stimulatory DCs (sDCs), DCregs express relatively high levels of the T cell co-inhibitory molecule programed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 and other immunoregulatory molecules4,7,8. Further, upon Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) or CD40 ligation in vitro, they fail to express the Th1 pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12p70. Moreover, they poorly induce allogeneic CD4 and CD8 T cell proliferation, as well as upregulation of proinflammatory IL-17 and IFNγ production compared to sDCs, and spare or induce Tregs9,10. In experimental animal models, adoptive transfer of DCregs suppresses autoimmune diseases11,12 and promotes organ allograft survival/transplant tolerance7,13,14. Moreover, in human volunteers, injection of immature DCs induces antigen (Ag)-specific inhibition of effector T cell function/Ag-specific Tregs15,16. Recently, we have shown that infusion of donor-derived DCregs increases the ratio of circulating Tregs to CD8 effector T cells in prospective human organ transplant recipients17, while also modulating effector CD8 T cell and NK cell responses post-transplant18.

Over the past decade, ex vivo generation of DCregs from monocyte precursors has emerged as an attractive approach in the nascent field of regulatory cell-based immunotherapy to improve clinical outcomes and reduce dependence on immunosuppressive drugs in organ transplantation and autoimmune diseases. Although there is no consensus regarding an optimal protocol for generation of human DCregs, or for validation of their tolerogenic properties, results of early phase clinical trials reporting the feasibility, safety and biological activity of DCregs in various autoimmune disorders have been reported19–21, while testing of DCregs has recently been instigated in clinical organ transplantation17,22–24.

While major strides have been taken towards clinical assessment of DCreg function, efforts have also been made to clarify how their functional specialization is regulated by distinct gene expression programs and signaling responses, both in the healthy steady-state and in the context of inflammation25,26. Recent work by Robertson et al. documented the transcriptomic signature of human DCregs using a bulk RNA-seq approach from publicly-available datasets27. However, there remains a critical gap in understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the development and maintenance of tolerogenic programs in DCregs. Elucidation of these mechanisms will not only aid in understanding the molecular regulation of DCreg tolerogenicity, but also help in development/design of next-generation DCregs for therapeutic assessment in organ transplantation or autoimmunity. Since transcriptional regulation is controlled in part by epigenetic programming, which is crucial in defining cell identity and fate, we hypothesized that epigenetic mechanisms that confer resistance of DCs to maturation are pivotal in controlling DCreg differentiation. DNA methylation is the covalent addition of methyl groups to CpG palindromes enriched in CpG islands,—hypermethylation of transcriptional regions is associated with downregulation of gene expression, while hypomethylation is associated with upregulation of gene expression28. Recently, Catala-Moll et al.demonstrated the interplay between the vitamin D receptor (VDR), downstream STAT3 signaling and the methylcytosine dioxygenase ten-eleven translocation 2 (Tet2) as a mechanism underlying vitamin D3 (vitD3)-induced human DC tolerogenicity29.

Here, we sought to extend discovery of epigenetic determinants/gene expression programs that may regulate the tolerogenic properties of DCregs during their in vitro generation from blood monocytes using a combination of vitD3 and IL-10 (vitD3/IL-10 DCregs). While the number of differentially-methylated regions (DMRs) was almost identical in DCregs and sDCs, the nature of these programs was different. Most of the programs in both populations were enriched in gene regulatory regions, including promoters and 5’ distal regions, suggesting their transcriptional regulatory role. Pathway analyses for the genes associated with these DMRs revealed anti-inflammatory/tolerogenic pathways enriched in vitD3/IL-10 DCregs compared to sDCs, including a novel branched chain amino acid (valine) catabolic pathway. Using mass-spectroscopy, we observed a trend toward less levels of valine in DCregs culture supernatant compared sDCs, which did not reach statistical significance due to heterogeneity in the healthy subjects (Suppl. Figure 2B). Hence, valine degradation might be important for the DCreg phenotype due to the observation of unmethylated genes in this metabolic pathway as well as amino acid levels but only for a sub-population of individuals. Further, transcription factor (TF) motif analyses demonstrated the enrichment of binding sites for immunosuppressive TFs e.g. Krueppel-like factor 11 (KLF11) in DCregs’ unmethylated DMRs, while AP-1 (FOS:JUN) TF binding sites were enriched in sDCs’ unmethylated DMRs. Additionally, we observed an inverse correlation between the levels of methylation and expression of key genes in vitD3/IL-10 DCregs compared to sDCs, including branched chain keto acid dehydrogenase E1 subunit alpha (BCKDHA), lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 3 (LAMP3), interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) and the high affinity scavenger receptor CD163. These findings may have implications for future targeting DCreg epigenetic programs using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas approaches to enhance their potential efficacy as cell therapy products in organ transplantation and autoimmunity.

Materials and methods

In vitro generation of human DCregs and sDCs

Leukapheresis products were obtained under an institutional review board-approved protocol (Institute for Transfusion Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA). Monocyte-enriched, elutriated fractions were recovered from 6 healthy human donors (4 males and 2 females) leukapheresis products and were used for generation of DCregs and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA; TLR4 ligand low toxicity derivative of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS))-matured sDC, as described previously10,17. In instances where the elutriated monocyte fraction purity was < 90%, CD14-specific immunobeads (Miltenyi, San Diego, CA) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to increase monocyte purity to > 90%. After 7 days culture, monocyte-derived DCregs and sDCs were harvested. The viability of DCregs and sDCs, determined by trypan blue staining, was routinely > 95%. A portion of each DC group was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) DNA Methylation analysis. Portions of the remaining DCs were antibody-stained for key surface molecules,- HLA-DR, CD11c, T cell costimulatory and coinhibitory molecules, the high affinity scavenger receptor CD163 (clone RM3/1, Biolegend), and CXCR4 (clone 12G5, ThermoFisher Scientific) and flow cytometry data analyzed using Flow Jo software.

Whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) data analysis

DNA was extracted from frozen cell pellets and underwent bisulfite treatment as described30. The bisulfite-modified DNA-sequencing library was generated using the Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq DNA library kit (Swift Biosciences) per the manufacturer’s instructions. WGBS data were collected from 6 sDC libraries and 6 corresponding DCreg libraries from the same donors. Per individual sample, quality control was first performed by tool FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Based on this, low-quality reads and adapter sequences were filtered out by tool Trimmomatic. Given the large file size, surviving reads were further split into subfiles. Reads from each subfile were then aligned to human reference genome hg19 by bisulfite aligner bismark. Then SAMtools was applied to merge the multiple aligned subfiles back into one library and sort files based on chromosomal locations. Picard tool (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) was employed on the sorted BAM file to mark duplicates. Eventually, methylation calling was performed by bismark methylation extractor to generate a list of chromosomal locations with corresponding methylation depth and rate. GEO database with accession number GSE244577.

Based on the methylation calling per library, downstream statistical analyses were performed comparing the 6 sDC and 6 DCreg libraries. DMR were called by R/Bioconductor package DSS, where the significant DMRs were defined by p-value (p.threshold) = 0.05, minimum region length (minlen) = 30 bps and minimum CpG sites (minCG) = 3. These DMRs were further annotated to gene regions by R/Bioconductor databases TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19.knownGene and org.Hs.eg.db, where promoter and downstream regions were defined by 1 kb upstream or downstream of the gene region, and the 5’ distal and 3’ distal were defined by 1–50 kb upstream or downstream of the gene region. Based on the gene annotation, in comparison with sDC methylation rate, unique genes annotated to promoter and 5’ distal regions with increasing (or decreasing) methylation rate in DCreg libraries were used for Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to detect significantly-enriched pathways and significant common upstream regulators/transcription factors. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on these DMRs to check the library grouping. Genes associated within unmethylated DMRs (DCreg and sDC) annotated to promoter regions were further used for motif analyses. DNA sequences of the 500 bp promoter regions of the DMR genes were extracted and applied into MEME to perform motif discovery. Common top motifs were further applied into TOMTOM to search for known TFs whose binding sites were similar to the discovered motifs.

Public data mining on gene expression data sets

We explored three public studies data sets for mRNA expression analysis31–33 and performed quantile normalization of the samples and differential expression analysis. The three studies were analyzed independently and subsequently integrated by checking their common regulated genes. Three public gene expression data set analyses of sDCs (or mature DCs or “mDCs”) and DCregs (or tolerogenic or “tolDCs”) were explored. GSE23371 data set contains three sDC and three IL-10/dexamethasone (DCreg) samples. GSE117946 data set has four sDC samples and four DC-10 (DCreg) samples. GSE52894 consists of four sDC specimens and four Dex + vitD3 (DCreg) specimens. Differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) were defined by FDR = 5% and fold-change > = 1.5. Using this cutoff, compared with sDCs, up- and down-regulated DEGs in DCregs were called from each individual study. Eventually, common up and down DEGs were called across all three studies. These DEGs were compared with the methylated and unmethylated genes detected from our WGBS data.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version 10). Unpaired non-parametric (Mann–Whitney test), parametric (Welch’s correction) and paired non-parametric t-test (Wilcoxon test) were used for two groups comparison *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01.

Results and discussion

Genome-wide changes in DNA methylation programming in both human DCregs and sDCs

DCregs exhibit anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive properties, even in the presence of potent inflammatory stimuli e.g., LPS or anti-CD40, which suggests the acquisition of stable epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, during their differentiation from monocytes. Hence, in order to potentially enhance the therapeutic potency/efficacy of DCregs, it is crucial first to understand the epigenetic determinants specific to DCregs that determine their tolerogenic properties10,34. Here, we performed DNA methylation analyses of DCregs generated in vitD3 and IL-10 compared with LPS-stimulated DCs (sDCs) using WGBS (Fig. 1A). WGBS is considered the gold standard approach for measuring DNA methylation at a single nucleotide resolution level compared to other approaches, such as reduced representation of bisulfite sequencing and bead chip array35–37.

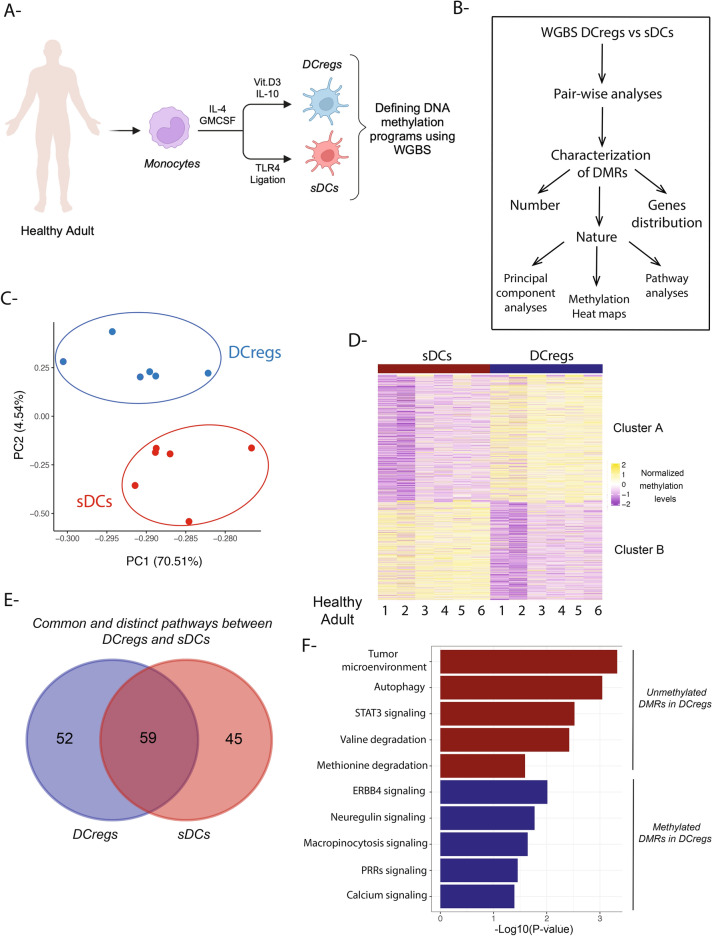

Fig. 1.

Genome-wide changes in DNA methylation of human DCregs compared with sDCs; (A) In vitro culture schema showing the generation of DCregs and sDCs from human peripheral blood monocytes; (B) Schematic overview showing DNA methylation computational analyses pipeline for DCregs vs sDCs; (C) Principal component analyses (PCA) of differentially-methylated regions (DMRs) in DCregs and sDCs; (D) DNA methylation heat map showing two clusters (A and B) representing levels of methylation in DMRs (DCregs vs sDCs) represented as normalized methylation levels (Z-score −2 to 2); (E) Venn diagram showing the common and distinct pathways in DCregs and sDCs using the genes annotated to DMRs within introns, exons, 5’ distal regions, intergenic, promoter, and other regions (other = 3UTR, 5UTR, 3’ distal, downstream) as an input in ingenuity pathway analyses (IPA); (F) the nature of the pathways enriched in DCregs and sDCs using IPA.

To investigate potential tolerogenic-associated epigenetic programs in vitD3/IL-10 DCregs compared to sDCs, we first performed a pair-wise comparison of the DNA methylation data sets from both cell populations (Fig. 1B). This type of analysis allowed us to identify methylation differences at individual CpG sites across the genome; hence, the number, distribution and nature of DMRs associated with each cell population were determined (Fig. 1B). We then performed principal component analyses (PCA) of the methylation profiles of both cell types across six healthy subjects. As shown in Fig. 1C, PCA of DCregs versus sDCs revealed that a major component of variance (PC1-70.51%) and a minor component (PC2-4.5%) accounted for DC population-specific methylation programs that clustered each population separately from each other. These data suggest that each DC population acquired distinct epigenetic programs during its differentiation from monocytes.

We next performed heat map analyses to visualize the status of DMRs in the DCregs versus sDCs and observed 2 clusters of DMRs: cluster A, a group of DMRs that underwent demethylation in sDCs compared to DCregs, and cluster B,—a distinct group of DMRs that underwent demethylation in DCregs compared to sDCs (Fig. 1D). We next thought to ask whether the DMRs undergo dynamic changes during differentiation from monocytes. Hence, we used a publicly available dataset for monocyte DNA methylation29 and examined their methylome compared to sDCs and DCregs in our dataset. As shown in suppl. Figure 2A, the blue circles represent DNA methylation values (using bead chip array) from the public dataset for monocytes, mDCs, and DCregs generated using Vit.D3, while the red circles represent our dataset representing DNA methylation (WGBS) levels in sDCs and DCregs generated in the presence of VitD3 and IL-10. We chose three representative genes (PDGFC, ACSL1, and UBL3) for positive direction (high in sDCs and low in DCregs), while FCGR2A, DIS3L2 and LPP represent the opposite direction. These observations prompted us to then identify the nature of the pathways enriched in each cell population. Since each population acquired a specific set of DMRs associated with a certain group of genes, we used genes annotated to the DMRs as an input for ingenuity pathway analyses (IPA). As expected, each cell population exhibited its own distinct pathway enrichment (52 for DCregs and 45 for sDCs), although they did concomitantly show overlap of other pathways (59) since they shared a common differentiation precursor i.e., monocytes (Fig. 1E). Additionally, we sought to define the nature of these distinct pathways in each population. Thus, we observed enrichment of immunosuppressive pathways, including the STAT3 signaling pathway that is downstream of IL-10, as well as enrichment of the tumor microenvironment pathway (which includes PD-L1, a ligand for PD-1 as well as LGALS9, galectin 9 which is ligand for Tim-3) in the unmethylated DMRs in DCregs compared to sDCs. On the other hand, enrichment of pathogen recognition receptor (PRR) inflammatory pathways was identified in the methylated DMRs in vitD3/IL-10 DCregs compared to sDCs (Fig. 1F, Suppl. table 1). Further, our data revealed an amino acid catabolic pathway,—valine degradation, that was enriched in the unmethylated DMRs of DCregs. These data suggest the involvement of amino acid catabolism pathways in generation of the immunosuppression properties of DCregs38,39. Indeed, a previous study demonstrated the importance of valine in the maturation and function of human sDCs40. Thus far, the DNA methylation analyses described herein reveal distinct, genome-wide changes in each DC population that may lead to discovery of novel pathways, that could contribute to VitD3/IL-10 DCreg tolerogenicity.

Immunosuppressive transcription factors and regulators are associated with DCregs DMRs

As indicated in Fig. 1B, differential methylation analyses allowed us to define not only the nature of the DMRs, but also their numbers and distribution in each DC population relative to the other. Indeed, we detected 4036 and 3243 methylated DMRs in vitD3/IL-10 DCregs and sDCs, respectively (Fig. 2A, Suppl. table 2). Further, the levels of DNA methylation across autosomal chromosomes are depicted in Suppl. Figure 2D. Among the methylated DMRs that distinguished DCregs from sDCs was the nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB1),—a TF known for its role in regulation of DC maturation through augmentation of MHC and costimulatory molecule expression in response to inflammatory signals, such as LPS41,42. As shown in Suppl. Figure 1B, the NFkB1 promoter region was highly methylated in DCregs and predominantly unmethylated in sDCs. To further validate our DNA methylation findings, we examined NFkB1 gene expression levels in three publicly available data sets. As shown in Suppl. Figure 1C–D, we observed upregulation of NFkB1 in sDCs compared to DCregs, which inversely correlated with DNA methylation status in DCregs vs sDCs. Further, PD-L1 (CD274), which is known to be upregulated in DCregs, was one of the DMRs located in the 5’ distal region that is more methylated in sDCs compared to DCregs (Suppl. Figure 2C). When we examined the distribution of the DMRs in each cell population, we found that the majority of these DMRs were enriched in transcriptional regulatory regions, including promoters and 5’ distal regions (1–50 Kb upstream transcription starting site-TSS), suggesting their involvement in regulation of gene expression regardless of the cell population (Fig. 2A). Although the percentage of regulatory DMRs was almost the same between vitD3/IL-10 DCregs and sDCs (~ 41 vs 35%), the genes annotated to them were distinct from each other, with minimal overlap (Fig. 2B).

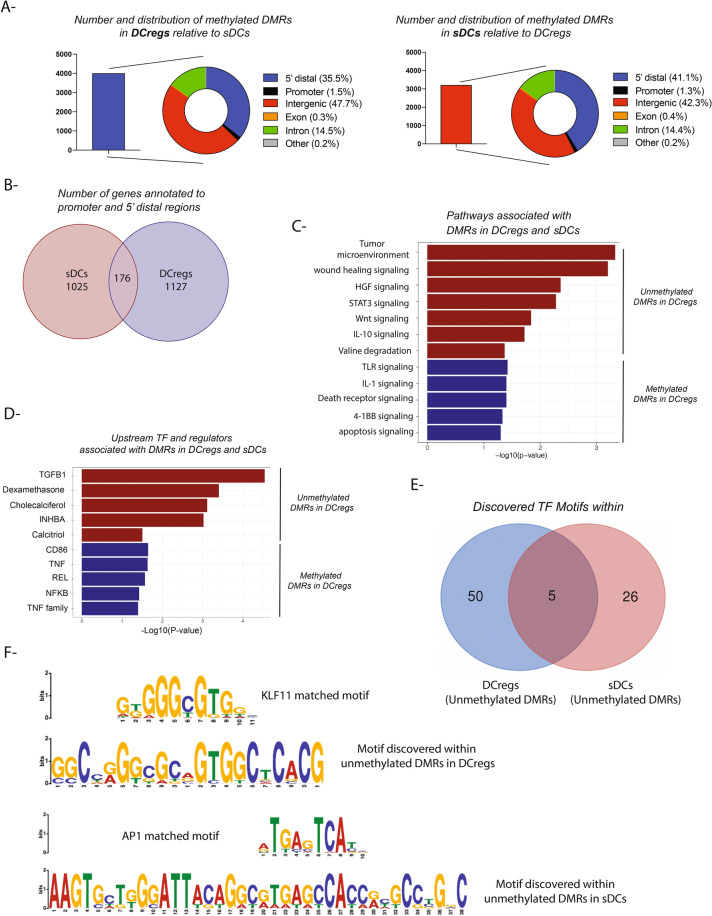

Fig. 2.

Nature, number and distribution of DMRs comparing DCregs and sDCs (A) Number and distribution of the DMRs in DCregs and sDCs (other = 3UTR, 5UTR, 3’ distal, downstream); (B) Venn diagram showing the common and distinct genes annotated to regulatory gene transcription regions including 5’ distal regions and promoters in DCregs and sDCs; (C) the nature of the pathways enriched in DCregs and sDCs using genes annotated in B; (D) Upstream transcription factors (TF) and regulators associated with genes annotated to regulatory transcription regions analyzed in B; (E) Venn diagram showing common and distinct discovered TF motifs within DMRs in DCregs vs sDCs (F) Motif discovery analyses showing enrichment of Krueppel-like factor 11 (KLF11) motif in unmethylated DMR of DCregs (upper panel) as well as activator protein-1 (AP1) TF motif enriched in unmethylated DMRs of sDCs (lower panel).

Next, we sought to characterize the nature of the pathways associated with vitD3/IL-10 DCreg tolerogenicity. Thus, we performed IPA of the genes linked to regulatory unmethylated and methylated DMRs in vitD3/IL-10 DCregs (Fig. 2C). The genes associated with unmethylated regulatory DMRs were enriched in pathways of immune suppression, including tumor microenvironment and hepatic growth factor signaling pathways. Further, we observed enrichment of STAT3 and IL-10 signaling pathways. By contrast, inflammatory signaling pathways enriched in sDCs included TLRs, IL-1, and 4-1BB pathways, confirming those discovered in Fig. 1D.

We then took our analyses one step further and analyzed the TFs and regulators upstream of the pathways defined in Fig. 2C. The rationale behind these analyses was to discover master regulators common to different gene pathways in each DC population that might help eventually in the design and manipulation of DCregs to enhance/maximize their tolerogenicity (Fig. 2D). For instance, in our analyses as shown (Fig. 2D), we observed that the biologically-active form of vitamin D, calcitriol, is enriched as major chemical regulator for unmethylated DMRs in DCregs, as well as the transcription regulator vitamin D receptor (VDR) and the growth factor TGF-β (Fig. 2D). Hence, DCreg tolerogenicity could potentially be induced/enhanced by maintaining the demethylation status of promoter regions of these regulators in monocytes during their differentiation into DCregs. In fact, a previous study demonstrated overlap of VDR canonical binding sites with unmethylated regions in tolerogenic DCs29. On the other hand, NFkB1 and TNF were enriched as regulators of inflammatory pathways in sDCs, as shown in Fig. 2D. Indeed, using 3 publicly available gene expression data sets, we observed an increase in NFkB1 gene expression in sDCs compared to DCregs confirming our observations in Suppl. Figure 1D.

Since cross-talk between DNA methylation and TFs plays an important role in regulation of gene expression, as well as splicing and chromatin remodeling43, we sought to define the nature of TF motifs enriched in the DMRs. To achieve this, we performed TF motif enrichment analysis using DMRs as an input (methylation vs demethylation direction). In these analyses, we selected the DMRs within 500 bp of the TSS because of their function as regulatory regions for gene expression. We then looked for enrichment of binding motifs of known TF (described in publicly-available datasets) in these DMRs. Our initial assessment of the enrichment analyses revealed 50 TF motifs unique to the DMRs unmethylated in DCregs compared to sDCs, and 26 unique to the DMRs unmethylated in sDCs compared to DCregs. Only 5 TF motifs were shared between both populations (Fig. 2E). These data suggest that each population exploits a constellation of TFs unique to its differentiation pathway. We then thought to define the nature of these TF motifs and how they might contribute to the tolerogenic or pro-inflammatory properties of DCregs and sDCs, respectively. One of the TF motifs that we observed was enriched in unmethylated DMRs of DCregs was Kruppel-like zinc finger 11 (KLF11) (Fig. 2F, upper panel). KLF11 is also known as TGF-β-inducible early growth response protein 2. Thus, KLF11 decreases expression of Smad7, a negative regulator of the TGF-β signaling pathway, through binding to its promoter44–46. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 2D, TGF-β was one of the top regulators associated with unmethylated DMRs in DCregs, confirming our TF motif data. On the other hand, the activator protein-1 (AP-1) (Fos:Jun) TF motif, that has an important role in inflammatory responses, was enriched in unmethylated DMRs associated with sDCs (Fig. 2F, lower panel). Additionally, we observed CTCF (a methylation sensitive TF) that can bind to sDCs unmethylated DMRs in genes involved in the cell cycle such as CDKN1A, 2A, as well as integrin subunit ITGA8 and MYOG. Another TF ATF7 can bind to unmethylated DMRs in genes such as DUSP5,10. In the case of DCregs, we observed CREB1 as a DNA methylation sensitive TF. We also observed IRF426 as one of the TF upstream unmethylated DMRs in DCregs. The genes associated with the DMR are RUNX2, RORα, and ITGB1.

These data provide a basis for understanding the tolerogenic versus inflammatory epigenetic signatures of DCregs compared to sDCs, that could ultimately lead to technological advances in generation of these cells. However, the question remains, how to translate this into practice? For instance, in the context of the tumor microenvironment, DCregs’ tolerogenic properties could potentially be modulated and reverted epigenetically using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. This could be achieved using engineered cas9 with blunt activity i.e., dCas9. This form of Cas9 can be used as a scaffold for different epigenetic writers/ erasers guided to specific target genes complementary to the guide RNA47 in monocytes during their differentiation to DCregs. On the other hand, the pro-inflammatory potential of DCs could be altered to promote their tolerogenicity using the same approach in the context of transplantation and autoimmune diseases. Thus, our data reveal an opportunity to learn and apply the epigenetic properties of each cell population to one another. Consequently, future endeavors will be pursued to apply these approaches using CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

DCregs generated in vitD3 and IL-10 exhibit a tolerogenic epigenetic signature that correlates with publicly-available transcriptional signatures of DCregs

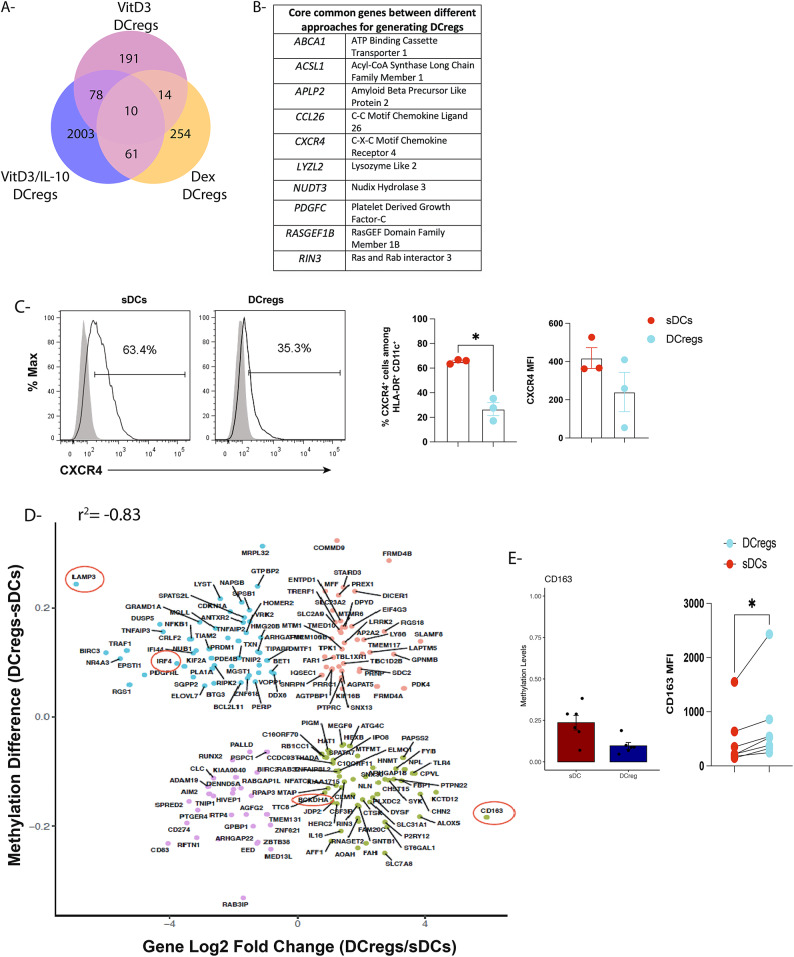

There is no consensus approach/protocol to generate human DCregs in vitro. Hence, we sought to define a common epigenetic signature core of DCregs generated using three different approaches i.e., vitD3 alone, dexamethasone alone29,48 and our approach using vitD3/IL-1010,17,34. Indeed, in the first assessment of the data, we observed 14 DMRs (unmethylated in DCregs) common between DCregs generated in vitD3 compared to dexamethasone alone. Additionally, 78 DMRs were detected upon comparing vitD3 alone to vitD3/IL-10, while 61 DMRs were common between dexamethasone and vitD3/IL-10 culture conditions. Further, we observed 10 DMRs common between all three DCreg culture conditions (Fig. 3A). One of these DMRs was the CXCL12 chemokine receptor- CXCR4 (Fig. 3B) engagement of which plays an important role in initiation of cutaneous immune responses49, promoting DC maturation and migration50. Indeed, we found higher expression of CXCR4 on sDCs compared to DCregs (Fig. 3C). ABCA1 was another unmethylated DMR that was enriched in DCregs generated using the three approaches. This gene plays an important role in autoimmunity by efflux of cholesterol where ABCA1-deficient DCs contribute to development of autoimmune diseases51. Additionally, CCL26 (Eotaxin-3) plays an immunoregulatory role, whereby its binding to CCR1 and 5 expressed by monocytes inhibits chemotaxis and intracellular calcium release52. Further, in vitro treatment of DCs with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) induces generation of Tregs expressing FoxP3 and IL-1053, indicating the role of this gene in skewing immune responses toward tolerance. These data indicate that specific immunomodulatory epigenetic programs may be imprinted during differentiation of monocytes to DCregs regardless of the culture conditions, -albeit we did not cover other approaches for generation of DCregs, including e.g., use of rapamycin or vitD3/dexamethasone due to lack of available data sets.

Fig. 3.

DCs generated in vitD3 and IL-10 exhibit a tolerogenic transcriptional and epigenetic signature (A) Venn diagram showing distinct and overlapping unmethylated DMRs in DCregs generated using three different culture conditions (VitD3 alone, VitD3/IL-10, and Dexamethasone alone); (B) Summary table showing common core epigenetic signature list between the three DCreg culture conditions (C) Histograms and bar graphs showing expression of CXCR4 (incidence of positive cells and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)) among CD11c + HLA-DR + DCs (DCregs vs sDCs); *p < 0.05 unpaired parametric t-test with Welch’s correction; (D) scatter plots showing the nature of the genes and correlation between methylation differences (DCregs-sDCs) and gene expression changes (Log2 DCregs-sDCs). Pearson’s correlation (r2 = − 0.83) was used by comparing highly methylated genes with low gene expression in the same set of genes; (E) Bar graph showing levels of methylation across CD163 promoter region (Chr12: 7665530–766596) in DCregs compared sDCs in six different healthy adult donors (Left panel), Unpaired non-parametric t-test (Mann–Whitney test) *p < 0.05 and paired analyses showing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)) on CD11c + HLA-DR + DCs (DCregs vs sDCs) [Right panel]. Non-parametric paired t-test (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test *p < 0.05).

Since epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, play important roles in regulation of gene expression patterns, we next sought to better define the DNA methylation signature in relation to the transcriptional signature of DCregs28. Thus, we performed an integration analysis between our DNA methylation data set and publicly-available transcriptional signatures of DCregs. The goal behind this approach was to define a set of specific DNA methylation programs that were unmethylated and associated with genes upregulated in DCregs compared to sDCs, and vice-versa. We first sought to re-analyze publicly-available DCreg and sDC gene expression data sets to integrate them later with our DNA methylation data. As shown in Suppl. Figure 1A, we analyzed expression profiles from 3 publicly-available studies, with a total of 11 samples of DCregs vs 11 sDCs. Since each study took a different approach to generate DCregs (IL-10, as well as combination of vitD3 and dexamethasone), we only included the differentially-expressed genes shared by the 3 studies of DCregs compared to sDCs. In these analyses, we observed a total of 549 and 512 genes that were upregulated and downregulated in DCregs compared to sDCs, respectively (Suppl. Figure 1A). Next, we performed integrative analyses between our DNA methylation and the public gene expression data sets. Hence, we used a simple linear regression test (Pearson’s correlation analysis) to draw relationships between two variables: (i) log2 fold-change in gene expression and (ii) methylation difference in DCregs relative to sDCs (Fig. 3D). We found an inverse correlation between the two variables using Pearson’s correlation (r2 = -0.83), in which 57 upregulated genes were associated with unmethylated DMRs in DCregs compared to sDCs (Fig. 3D). By contrast, 49 genes were down-regulated in DCregs compared to sDCs. These genes were associated with methylated DMRs in DCregs relative to sDCs.

We next sought to better define the nature of those DMRs associated with genes down-regulated in DCregs (upregulated in sDCs). For instance, in DCregs, we observed a decrease in gene expression levels of IRF4,—an important TF for the differentiation of sDCs and promotion of memory CD8 T cell differentiation54. Downregulation of IRF4 gene expression correlated with high levels of IRF4 methylation in its transcription regulatory region (Fig. 3D). Indeed, we previously reported lower levels of IRF4 protein expression by DCregs as compared to sDCs17. We also observed a similar pattern in the lysosomal-associated membrane protein-3 (LAMP3) gene, known to be one target of vitD355 as well as NFkB1 (Fig. 3D). On the other hand, upregulation in CD163 gene expression in DCregs was inversely correlated with levels of DNA methylation in CD163 promoter region (Fig. 3D, 3E-left panel). Upon examining cell surface expression of CD163 at the protein level by flow cytometry, we detected significant upregulation of CD163 by DCregs compared to sDCs (Fig. 3E-right panel).

These data confirm results of earlier studies showing expression of CD163 by human tolerogenic DCs expressing IL-10 (DC-10) as well as tolerogenic DCs generated in the presence of dexamethasone31,56,57. Further, the branched chain alpha keto-acid dehydrogenase (BCKDHA), a crucial enzyme in the catabolic pathway of the amino acid valine, was upregulated in DCregs at the transcriptional level, whereas it was unmethylated compared to sDCs.

Overall, our study highlights important findings that could enhance our understanding of human DC molecular biology through the lens of epigenetics: (i) both DCregs and sDCs acquire distinct epigenetic programs during their differentiation from monocytes,- albeit they share a few common ones, (ii) these programs are enriched in gene regulatory regions controlling immunosuppressive pathways e.g., IL-10/STAT3 and valine degradation in the case of DCregs and NFkB1 in the case of sDCs, (iii) inverse correlation between the DNA methylation status of these programs and gene expression, (iv) enrichment of immunomodulatory TF binding motifs such as KLF11 in DCreg DMRs and AP-1 in the case of sDCs, and (v) identification of a common DCreg epigenetic core signature across three different generation approaches.

Limitations of the study

Despite the methylome-based clustering for each DC population (Fig. 1C), we also observed heterogeneity within the same cell population between different healthy subjects. This could be attributed to performing bulk epigenetic analyses rather than single cell analysis. Further, these data hint at the heterogeneity in pattern of DNA methylation between healthy individuals, which could be attributed to heterogeneity of monocytes with different capacities to give rise to DCregs versus sDCs. Thus, subpopulation(s) of monocytes may be pre-programmed to differentiate into DCregs compared to others that differentiate into sDCs. The balance of such monocyte subpopulations could define propensity for DCreg differentiation and hence the efficacy of the cell therapy product. Future single cell multiomics studies will be implemented to further understand the nature of DC heterogeneity in healthy subjects. Additionally, we only observed 10 overlapping DMRs between our study and two public studies, as shown in Fig. 3A. In our study, we performed whole genome bisulfite sequencing, which covers the majority of the genome, while the other two (public) datasets were generated using the bead array approach, where only a certain number of probes are designed against a limited number of CpGs. This may explain why we only see 10 overlapping genes, but we would certainly expect a higher number of overlapping genes if whole genome data sets were available using other approaches for generation of DCregs. Due to lack of publicly-available DNA methylation data sets, we were only able to compare two approaches (vitD3 alone and dexamethasone alone) to our method using vitD3/IL-10. Finally, our analyses are based on the common DMRs among all six healthy individuals, which could be missing biologically-relevant DNA methylation programs that are specific to each individual.

In conclusion, identifying tolerogenic epigenetic targets represents a potential opportunity for translational approaches given the feasibility/safety of DCreg therapy that has been established in early phase autoimmune disease and organ transplant trials17,20–22,24. Manipulating these epigenetic programs could enhance the efficacy of DCregs as a cell therapy product in the future.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported in part by the Pittsburgh Liver Research Centre supported by NIH/NIDDK Digestive Disease Research Core Center grant P30DK120531(SL and HAA), National Institutes of Health grant U01 AI136779 (AWT). This research was also supported in part by the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing through the resources provided. Specifically, this work used the HTC cluster, which is supported by NIH award number S10OD028483.

Author contributions

S.L, H.A, D.M and A.T wrote the paper. S.L and H.A performed the analyses. A.Z performed in vitro experiments. S.D performed the Valine mass spectroscopy analyses. S.L, H.A, D.M, A.Z, S.D, A.T read and edit the paper.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the GEO repository, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nig.gov/geo//query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE244577 (GEO accession GSE244577).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Angus W. Thomson, Email: thomsonaw@upmc.edu

Hossam A. Abdelsamed, Email: abdelsamedha@upmc.edu, Email: habdelsamed@augusta.edu

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-79299-x.

References

- 1.Sakaguchi, S. et al. Regulatory T cells and human disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol.38, 541–566 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alhabbab, R. Y. et al. Regulatory B cells: Development, phenotypes, functions, and role in transplantation. Immunol. Rev.292 (1), 164–179 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grzywa, T. M. et al. Potent but transient immunosuppression of T-cells is a general feature of CD71(+) erythroid cells. Commun. Biol.4 (1), 1384 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ochando, J. et al. Tolerogenic dendritic cells in organ transplantation. Transpl. Int.33 (2), 113–127 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riquelme, P. et al. TIGIT(+) iTregs elicited by human regulatory macrophages control T cell immunity. Nat. Commun.9 (1), 2858 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veglia, F., Sanseviero, E. & Gabrilovich, D. I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol.21 (8), 485–498 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morelli, A. E. & Thomson, A. W. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat. Rev. Immunol.7 (8), 610–621 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ness, S., Lin, S. & Gordon, J. R. Regulatory dendritic cells, T cell tolerance, and dendritic cell therapy for immunologic disease. Front. Immunol.12, 633436 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raker, V. K., Domogalla, M. P. & Steinbrink, K. Tolerogenic dendritic cells for regulatory T cell induction in man. Front. Immunol.6, 569 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zahorchak, A. F. et al. High PD-L1/CD86 MFI ratio and IL-10 secretion characterize human regulatory dendritic cells generated for clinical testing in organ transplantation. Cell Immunol.323, 9–18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoop, J. N., Robinson, J. H. & Hilkens, C. M. Developing tolerogenic dendritic cell therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: what can we learn from mouse models?. Ann. Rheum. Dis.70 (9), 1526–1533 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Brussel, I. et al. Tolerogenic dendritic cell vaccines to treat autoimmune diseases: can the unattainable dream turn into reality?. Autoimmun. Rev.13 (2), 138–150 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezzelarab, M. B. et al. Regulatory dendritic cell infusion prolongs kidney allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am. J. Transpl.13 (8), 1989–2005 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marin, E., Cuturi, M. C. & Moreau, A. Tolerogenic dendritic cells in solid organ transplantation: Where do we stand?. Front. Immunol.9, 274 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhodapkar, M. V. & Steinman, R. M. Antigen-bearing immature dendritic cells induce peptide-specific CD8(+) regulatory T cells in vivo in humans. Blood100 (1), 174–177 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhodapkar, M. V. et al. Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T cell function in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med.193 (2), 233–238 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macedo, C. et al. Donor-derived regulatory dendritic cell infusion results in host cell cross-dressing and T cell subset changes in prospective living donor liver transplant recipients. Am. J. Transpl.21 (7), 2372–2386 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran, L. M. et al. Donor-derived regulatory dendritic cell infusion modulates effector CD8(+) T cell and NK cell responses after liver transplantation. Sci. Transl. Med.15, 4287 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell, G. M. et al. Autologous tolerogenic dendritic cells for rheumatoid and inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis.76 (1), 227–234 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benham, H. et al. Citrullinated peptide dendritic cell immunotherapy in HLA risk genotype-positive rheumatoid arthritis patients. Sci. Transl. Med.7, 29087 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zubizarreta, I. et al. Immune tolerance in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica with peptide-loaded tolerogenic dendritic cells in a phase 1b trial. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116(17), 8463–8470 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawitzki, B. et al. Regulatory cell therapy in kidney transplantation (The ONE Study): a harmonised design and analysis of seven non-randomised, single-arm, phase 1/2A trials. Lancet395 (10237), 1627–1639 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson, A. W. et al. Regulatory dendritic cells for human organ transplantation. Transpl. Rev. (Orlando)33 (3), 130–136 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau, A. et al. A Phase I/IIa study of autologous tolerogenic dendritic cells immunotherapy in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int.103 (3), 627–637 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalod, M. et al. Dendritic cell maturation: functional specialization through signaling specificity and transcriptional programming. EMBO J.33 (10), 1104–1116 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vander Lugt, B. et al. Transcriptional determinants of tolerogenic and immunogenic states during dendritic cell maturation. J. Cell Biol.216 (3), 779–792 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson, H. et al. Transcriptomic analysis identifies a tolerogenic dendritic cell signature. Front. Immunol.12, 733231 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones, P. A. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet.13 (7), 484–492 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catala-Moll, F. et al. Vitamin D receptor, STAT3, and TET2 cooperate to establish tolerogenesis. Cell Rep.38 (3), 110244 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdelsamed, H. A. et al. Human memory CD8 T cell effector potential is epigenetically preserved during in vivo homeostasis. J. Exp. Med.214 (6), 1593–1606 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comi, M. et al. Coexpression of CD163 and CD141 identifies human circulating IL-10-producing dendritic cells (DC-10). Cell Mol. Immunol.17 (1), 95–107 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen, B. J. et al. MicroRNA genes preferentially expressed in dendritic cells contain sites for conserved transcription factor binding motifs in their promoters. BMC Genom.12, 330 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malinarich, F. et al. High mitochondrial respiration and glycolytic capacity represent a metabolic phenotype of human tolerogenic dendritic cells. J. Immunol.194 (11), 5174–5186 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zahorchak, A. F. et al. Manufacturing and validation of good manufacturing practice-compliant regulatory dendritic cells for infusion into organ transplant recipients. Cytotherapy25 (4), 432–441 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, Y. A. et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the illumina infinium humanmethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics8 (2), 203–209 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dedeurwaerder, S. et al. A comprehensive overview of Infinium HumanMethylation450 data processing. Br. Bioinform.15 (6), 929–941 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harper, K. N., Peters, B. A. & Gamble, M. V. Batch effects and pathway analysis: two potential perils in cancer studies involving DNA methylation array analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.22 (6), 1052–1060 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Correale, J. Immunosuppressive amino-acid catabolizing enzymes in multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol11, 600428 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castellano, F., Correale, J. & Molinier-Frenkel, V. Editorial: immunosuppressive amino acid catabolizing enzymes in heallth and disease. Front. Immunol.12, 689864 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kakazu, E. et al. Extracellular branched-chain amino acids, especially valine, regulate maturation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Immunol.179 (10), 7137–7146 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rescigno, M. et al. Dendritic cell survival and maturation are regulated by different signaling pathways. J. Exp. Med.188 (11), 2175–2180 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ade, N. et al. NF-kappaB plays a major role in the maturation of human dendritic cells induced by NiSO(4) but not by DNCB. Toxicol. Sci.99 (2), 488–501 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu, H., Wang, G. & Qian, J. Transcription factors as readers and effectors of DNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet.17 (9), 551–565 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellenrieder, V. et al. KLF11 mediates a critical mechanism in TGF-beta signaling that is inactivated by Erk-MAPK in pancreatic cancer cells. Gastroenterology127 (2), 607–620 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gohla, G., Krieglstein, K. & Spittau, B. Tieg3/Klf11 induces apoptosis in OLI-neu cells and enhances the TGF-beta signaling pathway by transcriptional repression of Smad7. J. Cell. Biochem.104 (3), 850–861 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spittau, B. & Krieglstein, K. Klf10 and Klf11 as mediators of TGF-beta superfamily signaling. Cell Tissue Res.347 (1), 65–72 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brocken, D. J. W., Tark-Dame, M. & Dame, R. T. dCas9: A versatile tool for epigenome editing. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol.26, 15–32 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morante-Palacios, O. et al. Coordinated glucocorticoid receptor and MAFB action induces tolerogenesis and epigenome remodeling in dendritic cells. Nucleic Acids Res.50 (1), 108–126 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kabashima, K. et al. CXCL12-CXCR4 engagement is required for migration of cutaneous dendritic cells. Am. J. Pathol.171 (4), 1249–1257 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabashima, K. et al. CXCR4 engagement promotes dendritic cell survival and maturation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.361 (4), 1012–1016 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westerterp, M. et al. Cholesterol accumulation in dendritic cells links the inflammasome to acquired immunity. Cell Metab.25 (6), 1294-1304 e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petkovic, V. et al. Eotaxin-3/CCL26 is a natural antagonist for CC chemokine receptors 1 and 5. A human chemokine with a regulatory role. J. Biol. Chem.279 (22), 23357–23363 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agrawal, S. et al. PDGF upregulates CLEC-2 to induce T regulatory cells. Oncotarget6 (30), 28621–28632 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ainsua-Enrich, E. et al. IRF4-dependent dendritic cells regulate CD8(+) T-cell differentiation and memory responses in influenza infection. Mucosal Immunol.12 (4), 1025–1037 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malaguarnera, L. et al. Vitamin D3 regulates LAMP3 expression in monocyte derived dendritic cells. Cell Immunol.311, 13–21 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navarro-Barriuso, J. et al. Comparative transcriptomic profile of tolerogenic dendritic cells differentiated with vitamin D3, dexamethasone and rapamycin. Sci. Rep.8 (1), 14985 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Avancini, D. et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity downstream of IL-10 signaling is required to promote regulatory functions in human dendritic cells. Cell Rep.42 (3), 112193 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the GEO repository, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nig.gov/geo//query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE244577 (GEO accession GSE244577).