Abstract

Reconstructing hydrological conditions of past warm periods, such as the Eocene ‘hot house’ provides empirical data to compare to state of the art climate models. However, reconstructing these changes in deep time is challenging, for example, given the complex interplay between evapotranspiration, precipitation and runoff. As a proxy for past changes in these hydrological systems, the dynamics of fresh water input into marginal seas can be used to identify the spatiotemporal distribution of riverine runoff. Elemental barium (Ba) and radiogenic strontium (87Sr) are, depending on the amount of runoff and the background geology of the catchment area, typically enriched in river waters in comparison to seawater and can thus be utilized to determine changes in riverine fresh water discharge. Here, we use barium to calcium ratios (Ba/Ca) and radiogenic strontium isotopes (87Sr/86Sr) measured in fossil bivalve shells to reconstruct patterns of fresh water input into the paleo North Sea during the early to middle Eocene. Our reconstruction shows the potential of Ba/Ca and 87Sr/86Sr to serve as proxies for riverine runoff and highlights the spatiotemporal complexity of Eocene hydrological conditions in western Europe. In particular, our results enable changes in riverine input along geological to perennial time scales for different coastal regions to be determined, revealing a steady influx of fresh water, but with distinct spatiotemporal differences.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-79779-0.

Subject terms: Biogeochemistry, Climate sciences, Environmental sciences, Hydrology, Ocean sciences

Introduction

Understanding the details of the hydrological cycle in warm periods in Earth’s geological past is key knowledge in understanding climate system dynamics and is useful empirical information which may be compared to climate simulations in order to ultimately improve predictions of future climate change1. In particular, the Eocene has been the target of numerous investigations as an informative interval to study ‘high CO2’ climate states, since this period experienced the warmest global temperatures during the Cenozoic2–4. However, developing a complete understanding of hydrological patterns in the geological past is challenging, due to the complex interplay and spatial patterns of evapotranspiration, precipitation and runoff1. To address this issue, an examination of the individual components of the hydrological system is needed to deduce reliable climate information.

Marginal seas can record freshwater runoff through riverine input, as these shallow marine areas are an intersection between the continents and the open ocean. The radiogenic isotope of strontium (87Sr) and barium are typically present in river waters at a relatively high concentration due to the weathering of bedrock material in the catchment area of rivers5–7. The radiogenic strontium (87Sr/86Sr) and the barium to calcium ratio (Ba/Ca) in fossil carbonate shells can therefore be employed as proxies to identify the influence of freshwater input and accompanied salinity changes8–11. Fossil mollusc shells are an ideal archive to track such 87Sr/86Sr and Ba/Ca variability in coastal waters across a range of spatiotemporal resolutions due to the time-discrete (tidal to annual) layer structure of their shells (growth increments)12 and their widespread abundance and temporal continuity in the geological record. Due to their quasi-sessile mode of life, they are able to record local variations in the barium to calcium ratio and strontium isotopic composition of seawater on geological time to sub-annual scales. Additionally, some bivalves can tolerate considerable changes in salinity through freshwater input. This is true, for example, of selected members of the order Carditida, including the genera Venericor and Crassatella, which thrived in very shallow coastal areas to open marine environments13–17 and which are utilized here.

In this study, we use laser ablation inductively-coupled-plasma mass-spectrometry to measure sub-annual resolved 87Sr/86Sr and Ba/Ca in thirteen pristinely preserved fossil bivalve shells (see “Materials and methods”) from the southern paleo North Sea (Fig. 1; Table 1). The proxy data is used to reconstruct riverine runoff signals in three contiguous marginal sea basins (Paris Basin, Hampshire Basin, Belgian Basin) during the early to middle Eocene (53 to 40 Ma). Using this approach we show changes in hydrological patterns on different spatiotemporal scales from regional to local, as well as along geological periods to perennial intervals, gaining further insight into Eocene hydrological variability.

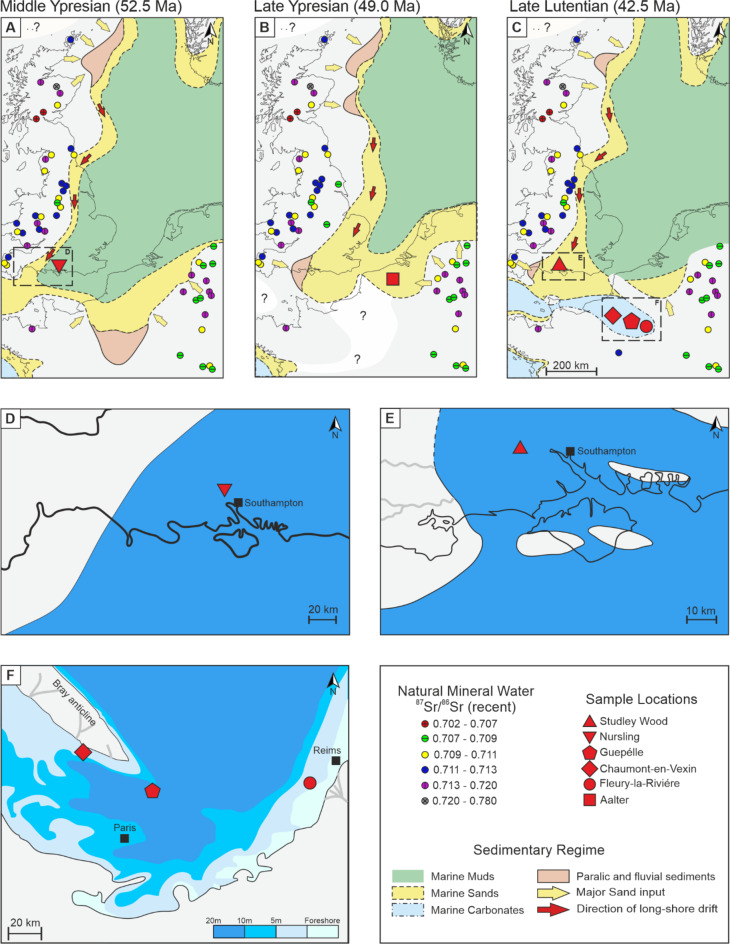

Fig. 1.

Palaeogeography of the Eocene North Sea basins with the 87Sr/86Sr of recent natural mineral waters overlain. (A–C) Evolution of the paleogeography and sedimentary regime of the paleo North Sea from the early to middle Eocene (edited after Knox et al.18). The 87Sr/86Sr of recent natural mineral waters is shown by the coloured symbols (edited after Voerkelius et al.19). (D,E) Reconstruction of the paleo coast line and sedimentary regime for the Hampshire basin (edited after Knox et al.18 and Gale et al.20). (F) Reconstruction of the paleo coast line and water depth of the Paris Basin (edited after Gely and Merle21 and Sanders et al.22).

Table 1.

Overview of sampling localities and age of the bivalve specimens utilized here.

| Basin | Age range | Sample Site | Stratigraphic unit | Species (number of specimens) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hampshire | 40.5–41.5 | Studley Wood | Huntingbridge Shell Bed, Elmore Member18 | Venericor planicosta (2) |

| 52.5–52.9 | Nursling | Nursling Member16 | Venericor sp. nov. (2) | |

| Paris | 43.4–44.0 | Chaumont-en-Vexin | Calcaire grossier moyen19 | Venericor planicosta (3) |

| 44.0–45.0 | Fleury-La-Rivière | Calcaire grossier moyen19 | Crassatella ponderosa (3) | |

| 39.3–41.03 | Le Guépelle | Sables du Guépelle19 | Venericor planicosta (1) | |

| Belgian | 47.5–49.0 | Aalter | Oedelem Sand Member20 | Venericor planicosta lerichei (2) |

Results

Thirteen individual bivalve shells originating from three separate basins along the southern margin of the paleo North Sea were analysed for this study. The three basins comprise several sample sites, detailed in Table 1. A more comprehensive overview of the age and stratigraphy for the different sample sites is given in supplementary data 3. Specimens from all locations are characterized by aragonitic preservation of the shell material (Supplementary Fig. S1d).

Strontium isotopic heterogeneity

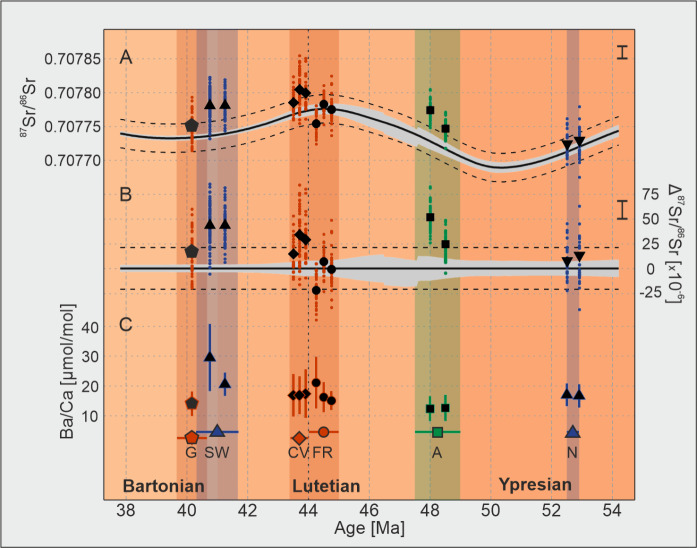

Mean 87Sr/86Sr shell values derived using laser ablation multi-collector inductively-coupled-plasma mass-spectrometry range from 0.707724 to 0.707804. The range of mean values from different specimens collected from the same sample site varies from less than 1.0 × 10−6 (far lower than analytical reproducibility) for the two specimens from Studley Wood up to 27.3 × 10−6 for the shells from Aalter. All specimens are characterised by internal variability beyond that which can be explained by the precision of the analytical technique, ranging from 53.4 to 104.2 × 10−6. In order to compare these values to the corresponding global 87Sr/86Sr seawater value, we use the data compilation of McArthur et al.23 to which we add an envelope of ± 21 × 10−6 which is the modern coastal seawater variability6 (Fig. 2a, b). Almost all specimens analysed here intersect with this 21 × 10−6 interval within their intra-shell 87Sr/86Sr variability, although the degree to which this heterogeneity overlaps with the temporally-equivalent open ocean values varies both within and among sample sites. In general, these fossil shells tend to more radiogenic values relative to the global seawater record, repeatedly exceeding the typical modern coastal seawater variability envelope. Exceptions to this are the samples from Nursling and Fleury-La-Rivière, which are characterised by mean 87Sr/86Sr within uncertainty of global seawater or in one case are less radiogenic (Fig. 2a, b). One important result from this dataset is the observation that the internal variation of 87Sr/86Sr isotopic values within a single shell can be larger than observed variation within modern coastal waters6 or known temporal variation across much of the Eocene23.

Fig. 2.

Strontium isotopic composition and barium baseline values of the fossil bivalve shells. (A) mean values (black symbols) and single measurements (coloured points) of 87Sr/86Sr from bivalve shells; the Eocene global seawater 87Sr/86Sr reconstruction is from McArthur et al.23 (black curve, grey shading—uncertainties of the LOWESS fit) with modern oceanic water 87Sr/86Sr variability (± 21 × 10−6, dashed lines)6; average standard error for single measurements is displayed by the black vertical bar (2 SE = 18 × 10−6); (B) mean values (black symbols) and single measurement (coloured points) of 87Sr/86Sr from bivalve shells normalised to the relevant Eocene seawater 87Sr/86Sr value23; the seawater 87Sr/86Sr value for normalisation is that for the mean age of each sampling site (Supplementary Material 2); average standard error for single measurements is displayed a black vertical bar (2 SE = 18 × 10−6); (C) bivalve shell Ba/Ca baseline (± 2SD); coloured symbols indicate mean age and horizontal bars, while the shaded areas show the age uncertainty for each sampling location, in which the plotted samples may fall (Table 1); G Le Guépelle, SW Studley Wood, CV Chaumont-en-Vexin, FR Fleury-La-Rivière, A Aalter, N Nursling; basins are indicated by colour: Paris Basin — red, Hampshire Basin — blue, Belgian Basin — green. Eocene stages are shown in the same colours as the geological time scale24.

Ba/Ca baseline

All analysed shells exhibit a similar pattern in terms of their Ba/Ca profiles in that they are characterised by a low and generally invariant baseline ratio (Ba/CaBL) punctuated by recurring peaks (Supplementary Fig. S1b), which exceed the background by a factor of up to 10 to 45 (Supplementary Data 1). On average, peak heights range between 100 and 300 µmol/mol with some rare exceptions reaching values > 500 µmol/mol. The determined Ba/CaBL values (s. “Methods”) for each of the examined shells range from 12.3 to 29.5 µmol/mol with an average variability of 5.8 µmol/mol (2σ of all Ba/CaBL values within a specimen, Fig. 2c). With two exceptions (see below), mean baseline values between individual specimens from the same sample site plot within a narrow range relative to the magnitude of intra-individual Ba/Ca heterogeneity, differing by less than 1.0 µmol/mol. Exceptions to this are the specimens from Fleury-La-Rivière and from Studley Wood, differing by 6.0 µmol/mol and 9.0 µmol/mol, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1c).

Discussion

Strontium isotopes as proxy for riverine input

The radiogenic strontium isotopic composition of aragonitic bivalve shells reflects ambient water 87Sr/86Sr 6,25. The incorporation of radiogenic strontium does not dependend on species or ontogeny26. This is also evident in the recent specimens analysed here (Supplementary Data 1).

In coastal areas changes in the radiogenic strontium isotope ratio of seawater are predominately influenced by riverine input7. However, submarine groundwater incursion can also potentially influence coastal waters, although the rate of discharge is considerably lower and typically characterised by an isotopic composition more similar to seawater than riverine input27. Therefore, the magnitude of the isotopic deviation of coastal seawater from the global mean mainly depends on the rate of riverine runoff and the 87Sr/86Sr value of the river water. In general, the 87Sr/86Sr signal of river water is primarily determined by the background geology of the catchment area via the effect that this has on the strontium isotopic composition of the bedrock and the ease with which it is leached during weathering. However, the isotopic composition of the river water can be seasonally variable depending on the rates of runoff, thus the seasonal distribution and amount of precipitation in the catchment area. These annual hydrological variations can result in seasonal changes in the 87Sr/86Sr signal of several 1000 × 10−6 at the river mouth28,29. However, the high concentration of Sr in seawater compared to most rivers means that the variability of the river water isotopic endmember is readily dampened, typically to less than a few 100 × 10−6 along the mouth area of the river, depending on the coastal regime6. As a result, the mean strontium isotopic composition of riverine runoff is temporally more constant on geological time scales and rather predominantly shifts with changes in the geology and geomorphology of the hinterland. However, there is currently no data set that allows for the reconstruction and description of such variations in the strontium isotopic composition of seawater along different spatiotemporal resolutions for paleo coastal areas.

Nonetheless, the different factors influencing the radiogenic strontium isotopic composition of coastal seawater on different spatiotemporal scales are evident in the 87Sr/86Sr dataset presented here. On an inter-regional scale, i.e. considering the entire southern paleo North Sea, the strontium isotopic composition of the analysed shells mainly follows the global 87Sr/86Sr seawater curve of the early to middle Eocene23 (Fig. 2a). Assessing the three marginal basins studied here individually reveals a regionally more heterogeneous distribution in 87Sr/86Sr between and within the contiguous areas in terms of the inter/intra-specimen variability and deviation from the global mean values of the analysed specimens (Fig. 2b). In this context, the observed changes in strontium isotopic composition correlate with both the paleo-oceanographic evolution of the basins as well as the 87Sr/86Sr ratio of the hinterland geology (Fig. 1). Here, this latter control is assessed using the 87Sr/86Sr values of recent mineral waters originating from pre-Eocene rock units in order to approximate the strontium isotopic composition of riverine runoff during the Eocene19. This approach is independent from the strontium concentration of the exposed basement rock, since only the soluble portion of the strontium can affect the radiogenic signal of the runoff. However, we acknowledge that uncertainties concerning the riverine input signal remain, since only limited data regarding catchment size exists while there are also large local variations in the isotopic composition of the mineral waters in some regions. Nonetheless, catchment relevant mineral water springs exceed the corresponding Eocene seawater 87Sr/86Sr value by several 1000 × 10−6 (Supplementary data 2), such that substantial riverine input is expected to be identifiable via strontium isotope analysis of the bivalves utilised here.

Specifically, large differences of the radiogenic strontium composition between riverine runoff and seawater are present in the Belgian Basin, where the freshwater signal mainly derives from weathering of Palaeozoic rocks of the Ardennes and thereby could potentially have exceeded that of seawater by several 10,000 × 10−6. This high 87Sr/86Sr value is also observed in the two specimens from Aalter, which are shifted to more radiogenic values, falling substantially above the confidence interval of the global seawater curve and projected coastal variability.

The hinterland geology of the Hampshire Basin was also likely characterised by a more radiogenic strontium isotopic composition, similar to the Belgian Basin19. This is because the weathering of late Palaeozoic rocks of southern Wales and south-western England, including the Dartmoor granite, which has a especially radiogenic strontium isotope composition30,31. However, of the four shells from the Hampshire Basin studied here, only the two late Lutetian specimens (Studley Wood) are characterised by an increased radiogenic signal, despite the likely radiogenic 87Sr/86Sr composition of the freshwater endmember. We hypothesise that this more complex pattern observed in the isotopic composition of the shells is related to the paleo-geographic and -oceanographic development of the Hampshire Basin from the early to middle Eocene. During the Ypresian (specifically, during the termination of sequence C1 of the London Clay) the specimen from Nursling thrived in an open marine environment, an offshore very shallow-water sandbar running parallel to the coastline, where any freshwater influence was presumably strongly dampened (Fig. 1d)30,32–34. In contrast, towards the end of the Lutetian (when the basal Elmore Member was deposited), specimens from Studley Wood lived above the storm wave base in fully marine transgressive sandy muds. At this time, the region had a more complex paleo-geography with a major river system supplying fresh water from nearby land directly to the west20,30,33 (Fig. 1e).

In contrast to the Belgian and Hampshire Basins, the background geology of the Paris Basin during the Eocene was mainly determined by Cretaceous and Jurassic sediments with a low radiogenic strontium isotopic composition, which are characterised by an 87Sr/86Sr ratio more similar to or even below that of Eocene seawater19,35,36. In accordance with this, the specimens of the Paris Basin exhibit the lowest 87Sr/86Sr values of all analysed shells. Within the basin, the 87Sr/86Sr values systematically vary between the three sampling sites, with the lowest 87Sr/86Sr ratios observed in the eastern part of the basin (at Fleury-La-Rivière) and increasing in a western direction to Le Guépelle and Chaumont-en-Vexin. This spatial pattern in Δ87Sr/86Sr most likely relates to different catchment areas contributing freshwater to the western and eastern parts of the basin. In the eastern part of the basin near Fleury-La-Rivière, riverine input most likely sampled Cretaceous sediments with 87Sr/86Sr values lower than Eocene seawater, whereas in the west at Chaumont-en-Vexin the freshwater runoff signal may have been influenced by the elevation of the Bray anticline21,22 (Fig. 1f). The Bray anticline also mainly consists of Cretaceous and Jurassic rocks35,37. However, as indicated by the 87Sr/86Sr values of the bivalve shells, the strontium isotopic composition was presumably more radiogenic than the eastern part of the basin. In addition, we stress that the Paris Basin was not a static environment, but underwent considerable changes in the extent of marine to brackish regimes within the ~ 4 Ma time span represented by the three examined sampling sites38, which limits our ability to estimate rates of runoff across the entire basin within a given time interval.

While the broad regional differences in the deviation of the 87Sr/86Sr values of the shells from global seawater can be largely attributed to the control of background geology on the likely composition of the fresh water flux, the local nuances in the pattern and short-term (intra-specimen) variations rather represent changes in catchment expansion and seasonally variable rate of runoff. The specimens from each sample site (except Studley Wood) show local variations in mean 87Sr/86Sr values. This short-term variability, in terms of geological time intervals, could result from millennial-scale movements of the catchment area, taking into account the likely amount of time averaging within the beds sampled at each site, which typically encompass several hundred thousand years in many or all cases. In addition, at the highest spatiotemporal resolution, the observed inter-shell 87Sr/86Sr heterogeneities, ranging from 53.4 to 104.2 × 10−6, likely reflects seasonal to perennial changes in the rate of runoff, since these are too large to result from analytical noise alone, which is on average 18 × 10−6 for each individual strontium isotope measurement (2× standard error; Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Data 1).

The intra-shell heterogeneity of the strontium isotopic composition of the shells analysed here can be used to estimate local salinity changes for each sampling site, by conducting a simple linear mixing model between river runoff and seawater. Here we apply a simple linear regression to assess the change in salinity as a function of 87Sr/86Sr variability. In order to do so, we use the global isotopic curve as the seawater 87Sr/86Sr endmember23, which is assumed to correspond to an open marine salinity value of 35. The strontium isotopic composition of the mineral waters described above19 represent the riverine endmember with a salinity of 0 (Supplementary Data 2). Using the maximum mineral water 87Sr/86Sr value for each basin results in a minimal estimate for salinity change and vice versa, since these short-term variations are influenced by both the rate of runoff and the strontium composition of the fresh water influx. We use the maximal range of 87Sr/86Sr within each shell to assess average perennial variability in salinity over the life time of the bivalves.

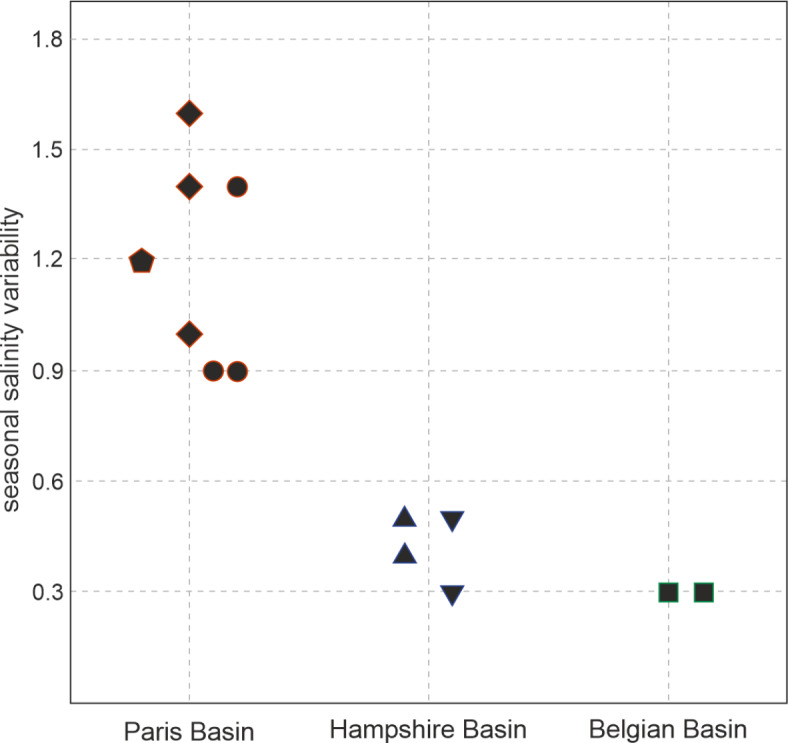

Following this approach, we find that the relative change in salinity for the paleo North Sea basin to range between 0.2 and 4.6 on the practical scale with no systematic long-term trend. However, a spatial difference between the three basins in the relative change in salinity driven by seasonal fresh water input can be observed (Fig. 3). In terms of intra-site/specimen variability, the shells from the Belgian Basin show the lowest degree, with reconstructed salinity 0.2 to 1.5 units below that of normal seawater. In this case, the comparatively small degree of intra-shell 87Sr/86Sr heterogeneity of ~ 77 × 10−6 in comparison to the large offset from the seawater composition reflects a riverine input with a low rate of runoff, but a more radiogenic strontium isotopic composition. In the case of the Hampshire Basin, the range of freshening estimates are greater than those from the Belgian Basin, from ~ 0.2 up to 2.8 units below normal seawater. These findings agree well with the previously discussed paleo-geographical and oceanographic conditions in the Hampshire Basin, which was determined by similar background geology 87Sr/86Sr values as in the Belgian Basin but therefore requiring a considerably greater degree of fluvial discharge at this site. The specimens from the Paris Basin reveal even higher salinity variations, ranging from 0.4 to 2.6 units below normal seawater in Fleury-La-Rivière to a 4.6 unit freshening in Chaumont-en-Vexin, again mirroring the hydrologically different conditions between the eastern and western part of the basin. Therefore, the observed differences in 87Sr/86Sr between the three investigated sampling sites cannot be attributed to the background geology alone, but must also be influenced by different amounts of freshwater input.

Fig. 3.

Mean perennial salinity variability. Mean salinity variations calculated for each individual shell using the maximum range of 87Sr/86Sr of each specimen (Fig. 2b) and the mean 87Sr/86Sr for the mineral waters19 of each of the three basins (Supplementary Data 2). Symbol and colour coding are the same as in Fig. 2.

Given the absence, to our knowledge, of a data set with comparably high temporal resolution, whether for fossil or recent bivalves, it is reasonable to question whether the observed short-term fluctuations in strontium isotopic composition might be influenced by factors other than seasonal variable fluvial discharge. However, the implied hydrological conditions are in good agreement with previous reconstructions of the Eocene Paleo North Sea (e.g. stable oxygen and clumped isotopes), revealing a heterogeneously distributed fresh water input between the different adjacent basins, geological periods and seasons39–41. Kniest et al.42 used seasonally resolved dual clumped isotopes (Δ47 + Δ48) to reconstruct sub-annual changes in salinity at Le Guépelle, analysing the same bivalve shell as presented in this study. The reconstructed δ18OSW revealed an enhanced summer runoff and shifts in salinity of 2.5 to 3.0 units, which agrees well with the freshening-driven decrease in salinity derived from the 87Sr/86Sr data of this study. However, local to regional conditions of the hydrological system appear to be well recorded by the radiogenic strontium composition, large changes in the climate system are not visible in the data set, i.e. as general trends due to global cooling during the early to middle Eocene2.

Ba/Ca baseline as an additional freshwater tracer in Eocene bivalves

In bivalves, Ba/Ca profiles along the growth direction of the shell typically consists of a flat and almost invariant baseline with occasionally large and relatively sharp peaks, which can exceed the background by up to several orders of magnitude9,43–46. This is also the case for all specimens examined in this study. While the cause of these peaks is still debated9,43,45–47, the Ba/Ca baseline is well correlated to the Ba/Ca ratio of the seawater in which the organism lived9,43,48. Similar to the strontium, the major source of barium to seawater in marginal environments is via the input of terrestrial material by fluvial discharge and depends on the chemical composition of the hinterland geology and the rate of runoff10.

However, we observe considerably less Ba/CaBL variability between and among the basins compared to our strontium isotope results. In general, baseline values fall within an interval of 10 to 20 µmol/mol, independent of sample site. The lowest Ba/CaBL in the samples from the Belgian Basin with an average value of 12.4 µmol/mol, implying a lower rate of runoff compared to our estimate based on the strontium isotopic composition of the same shells. In the Paris Basin the geographical difference in the rate of runoff revealed by the locally different 87Sr/86Sr values is not reflected by the barium baselines of the shells. The mean values of Ba/CaBL between the western and eastern sampling sites are almost identical with 16.9 µmol/mol and 17.4 µmol/mol in Chaumont-en-Vexin and Fleury-la-Rivière, respectively. The specimen from Le Guépelle exhibits a slightly lower value of 13.9 µmol/mol. An exception to this overall discordant Ba/Ca and 87Sr/86Sr results are the specimens from the Hampshire Basin, which are characterised by substantially higher values of 16.8 µmol/mol to 25.0 µmol/mol on average from the early to the middle Eocene, similar to the increasing radiogenic 87Sr/86Sr values and suggesting a higher riverine input.

The low spatial variability of Ba/CaBL suggest that the soluble barium concentration in the background geology of the southern Paleo North Sea appears to have been less variable than the strontium isotopic composition. This is perhaps unsurprising on a regional scale, although we note that modern global rivers are characterised by very different [Ba]8. However, due to the relatively short residence time of barium in seawater of about 10 ka49, the identification of spatiotemporal deviations in Ba/Ca ratio from global seawater is more hallenging than for strontium isotopes. In this context, the low temporal variations along the examined 13 Ma time interval are rather unexpected, indicating a more constant Ba/Ca ratio of the seawater than implied by the residence time.

In addition, we note that comparing the barium baseline of the fossil shells presented here with values derived from recent bivalves (generally < 4 µmol/mol9,43–46) demonstrate that, Eocene Ba/CaBL is about three to ten times higher. While a higher species-specific apparent distribution coefficient (DBa) could result in a higher degree of barium incorporation into the shell, modern bivalves are characterised by only minor differences in DBa between species and shell mineralogies9,43,50. Modern surface waters are typically depleted in Ba compared to the deep sea and are therefore undersaturated with respect to barite (BaSO4)51,52. Given an Eocene Ba concentation an order of magnitude higher, as inferred by the bivalve Ba/CaBL values reported here, would - all else being equal - likely result in seawater oversaturated with respect to barite, resulting in precipitation, which should remove Ba from the seawater and limit its bioavailability. However, seawater major-ion chemistry, in particular Ca2+, Mg2+ or SO42-, have changed considerably during the Cenozoic. The Eocene Ca concentration was about twice as high as in modern oceans, while Mg and SO42- concentrations have almost doubled over the last 40 Ma53,54. These differences in seawater composition would have acted to shift barite saturation of the average ocean in the opposite direction, thereby allowing a higher seawater Ba concentration and thus greater-than-modern bivalve Ba/Ca.

Conclusion

In this study the barium concentration and isotopic composition of strontium of Eocene bivalves was used to reconstruct river runoff in three adjacent basins of the paleo North Sea. Laser ablation (multi-collector) inductively-coupled-plasma mass-spectrometry facilitated high resolution measurements on thirteen specimens from different geological stages, allowing a reconstruction along different spatiotemporal resolutions. The 87Sr/86Sr values of the analysed shells constrain pronounced riverine input with varying rates of runoff within and among the examined marginal sea basins. At the regional scale, deviations in the strontium isotopic composition of the shells from the global seawater record, accounting for spatial and temporal variability in the likely composition of Eocene river water, also reflects the oceanographic evolution of the different basins18,20,34. In addition, leveraging the spatially-resolved nature of our strontium isotope measurements enables us to demonstrate that short-term (seasonal scale) salinity fluctuations derived from the observed range in 87Sr/86Sr variability over perennial intervals agrees well with estimates based on other proxy systems, such as oxygen or clumped isotopes42. In contrast, we find that comparative barium baseline data (Ba/CaBL) exhibit only minor changes during the considered time period, being apparently less sensitive to hydrological changes despite its demonstrable utility as a salinity proxy in certain settings in the recent geological past10.

Using laser ablation allows the fast and precise measurement of radiogenic strontium isotopes in carbonate shells at a high spatial, and therefore temporal, resolution. This has enabled us to achieve a previously unavailable spatiotemporal characterisation of past riverine discharge systems, describing them at a resolution that is considerably higher than the typical output of climate model simulations42. We therefore advocate for the application of this proxy system for the reconstruction of paleo environments, especially in ocean settings likely to be characterised by substantial influx of fresh water. In particular, we demonstrate that while the strontium isotopic composition as measured in the bivalve shells is a function of both freshwater-derived salinity change and background geology, it can nonetheless be utilized to detect hydrological patterns in regions where the paleo strontium isotopic composition of river water can be reconstructed with a good degree of confidence. Therefore, the proxy may serve as a valuable addition to more time and material intensive techniques, such as oxygen or clumped isotopes, allowing more differentiated identification of hydrological systems for the prediction of future climate scenarios.

Materials and methods

Sample material

Fossil bivalve shells of the species Venericor planicosta (Lamarck), Venericor planicosta lerichei (Glibert & Van de Poel), Venericor sp. nov. and Crassatella ponderosa (Gmelin) were used as archives. All taxa produced aragonitic shells, lived as shallowly burrowing suspension feeders and were widespread in the southern paleo North Sea during the Eocene. The shells originate from three geological sites within the Paris Basin (Chaumont-en-Vexin, Fleury-La-Rivière, Le Guépelle), two locations in the Hampshire Basin (Studley Wood, Nursling) and one location within the Belgian basin (Aalter), representing a time span of ~ 13 Ma from the Middle Ypresian (53 Ma) to the early Bartonian (40 Ma)16,55–57,35,58–60. All examined locations represent shallow marine environments, which are dominated by fine sand sedimentation with intermitted calcareous beds in the Paris and Belgian Basin and recurring clay-rich layers in the Hampshire Basin55–57,38,58,60.

Sample preparation and preservation screening

For each specimen, polished 150 μm-thick sections of the plane of maximum growth were produced. Analyses were conducted on the hinge plate (Supplementary Fig. S1a), due to the compactness and geometry of increments in this shell area, which means that this region of the shell is likely to be more resistant to diagenetic alteration and provides clear growth lines, such that spatially resolved analyses can be readily aligned perpendicular to the of shell growth pattern45.

To assess aragonitic preservation and to identify potential recrystallization of the shell material, the crystal structure of each specimen was determined by Raman spectroscopy. Raman analyses were performed using a WITec alpha 300R confocal micro-Raman microscope, located at the Institute of Geoscience at Goethe University in Frankfurt a.M. For the measurements the excitation laser (532 nm) was operated at 20–40 mW with an integration time of 0.2 s, 10 total accumulations and a holographic grating of 600 grooves mm−1. The resulting Raman spectra indicate aragonitic preservation in the case of all sampled shells (Supplementary Fig. S1d).

Elemental and isotopic analysis

Measurements of Ba/Ca and 87Sr/86Sr were conducted using laser ablation (MC)-ICPMS at the Frankfurt Isotope and Element Research Center (FIERCE), using a RESOlution S-155 193 nm ArF excimer laser system (formerly Resonetics LLC, now Applied Spectra Inc) coupled to either a single-collector (Ba/Ca) or multi-collector ICPMS (87Sr/86Sr).

For the analysis of Ba/Ca ratios the laser system was coupled to an Element XR sector field ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) tuned to ensure robust plasma conditions (Th/U = 1 ± 0.1, ThO+/Th+ < 0.5%, m/z 22/44 < 2%) while simultaneously maximising sensitivity (> 6 M cps 238U, NIST SRM612, 60 μm beam diameter, 6 Hz, ~ 6 J/cm2). Measurements were conducted in line scan mode with a beam diameter of 50 μm and a scan speed of 10 μm/s with a pulse rate of 10 Hz. All laser tracks were pre-ablated to remove possible surface contamination using a laser beam diameter, scan speed and pulse rate of 75 μm, 20 μm/s and 20 Hz, respectively. Samples and standard materials were analysed in an identical manner.

NIST SRM 612 was employed as external standard for the calibration. Monitored masses included 43Ca and 138Ba, with a NIST SRM612 Ba concentration of 39.7 µg/g used for calibration61. 43Ca was measured as internal standard and used for Ba/Ca calculation. The natural carbonate standards JCp-1-NP and JCt-1-NP and the synthetic USGS standard MACS-3-NP were used as external standards and repeatedly measured to assess accuracy and precision of the analyses. The results of the standard measurements are reported as averages across the three analytical sessions in which the samples were analysed. The measured Ba/Ca ratios for the three reference materials are well within reported values, yielding 7.8 ± 0.4 µmol/mol for JCp-1-NP (reference value = 7.1 ± 0.8 µmol/mol, accuracy: 9.86%), 5.0 ± 0.7 µmol/mol for JCt-1-NP (reference value = 4.1 ± 0.5 µmol/mol, accuracy: 21.95%) and 43.6 ± 2.0 µmol/mol for MACS3-NP (reference value = 46.2 ± 0.9 mmol/mol, accuracy: -5.63%)62,63.

Spatially resolved strontium isotope measurements were conducted using a Neptune Plus multi-collector ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to the same laser ablation system described above. The instrument was optimised for maximum sensitivity while ensuring the oxide formation rate (238U16O/238U) remained below 0.8%. Data were acquired in static mode using 1011 Ω amplifier for masses 83, 84, 85, 86, 87 and 88 on Faraday cups L4, L2, L1, C, H2, H3 and 1013 Ω amplifiers for masses 83.5 and 86.5 (L3, H1), which altogether allowed interferences from Kr and Rb, doubly-charged ions of Yb and Er, as well as any Ca dimers or argides to be monitored. All data were corrected using on-peak background measurements. Sample ablation was executed with 60 μm diameter quadratic laser spots, a fluence of 2.5 J/cm2 and a repetition rate of 8 Hz for 36.4 s. The laser spots were placed parallel to the Ba/Ca tracks with a spacing of 350 μm between the spots (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Instrumental mass bias was corrected using the exponential law and the natural 86Sr/88Sr ratio of 0.119464,65. Correction for the Kr interference on the masses 84 and 86, induced by impurities in the Ar plasma gas, was achieved by gas blank subtraction. The isobaric interference produced by Rb+ or Er2+ and Yb2+ were corrected applying empirical offset factors, which were determined from analyses of NIST SRM 612. Background, interference, and mass bias corrected 84Sr/86Sr and 87Sr/86Sr ratios outliers were removed by applying a 2SD criterion to all intensities with a 88Sr signal > 0.5 V. Following mass bias and interference correction, measurements yield the accepted natural 84Sr/86Sr of 0.05649 ± 0.00009 (2 SE). In order to assess the accuracy and precision of the method described above, the in-house standards MIR-A (Plagioclase megacryst, 3000 µg/g) and a recent oyster shell (Crassostrea gigas, Thunberg) from the Jade Bight (Germany) were measured repeatedly during the analysis in the same manner as the samples. On average, the measurements of MIR-A yield an 87Sr/86Sr value of 0.703082 ± 0.000037 (2SD), which is in good agreement with previously reported results from TIMS measurements of 0.703096 ± 0.000076 (2SD)66. The oyster shell yielded a mean 87Sr/86Sr of 0.709206 ± 0.000031 (2SD), which fits well with the mean modern seawater value of 0.709172 ± 0.000021 (2SD)6. Furthermore, the oyster shell value matches well with previously observed 87Sr/86Sr values for C. gigas from the southern North Sea and the English Channel, revealing average values ranging from 0.70917 to 0.709236 (supplementary data 4).

Ba/Ca baseline determination

The statistical distributions of measured Ba/Ca values are strongly right skewed for all shell records (Supplementary Fig. S1c), due to a dominant low Ba/Ca baseline punctuated by sharp peaks with Ba/Ca values 10 to 50 higher than the background. Here, we use the mode of the probability density function as a threshold to distinguish between background and peaks. Baseline values (Ba/CaBL) and its variability are then defined as the mean and 2SD variability of all values smaller than the mode of all measurements within a single shell.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded through the VeWA consortium by the LOEWE programme of the Hessen Ministry of Higher Education, Research and the Arts, Germany. The authors kindly thank Alan Woodland for technical support of the Raman spectroscopy. Furthermore, we thank Daniel Vigelius for assistance on the Raman measurements. We are grateful for sample preparation conducted by Sören Tholen, as well as technical support of Linda Marko and Alexander Schmidt during LA-(MC-)ICPMS measurements. FIERCE is financially supported by the Wilhelm and Else Heraeus Foundation and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG: INST 161/921-1 FUGG, INST 161/923-1 FUGG and INST 161/1073-1 FUGG), which is gratefully acknowledged. This is FIERCE contribution No. 178.

Author contributions

The study was initially conceived by J.F.K. under the supervision of J.R. Preservation screening was performed by J.F.K., as well as the determination of the increment growth pattern and age of the individual specimens, with support of S.V. Ba/Ca analysis and data processing were carried out by D.E. and J.F.K. Strontium isotope measurement and data processing was done by A.G., M.C. and J.F.K. The sample material was contributed by J.A.T., J.D.S. and J.V. The funding for the study was acquired through J.R., with support of W.M. and S.V. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.F.K. and revised with contributions of all authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository (zenodo.org/records/14178112).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tierney, J. E. et al. Past climates inform our future. Science370, 1 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zachos, J. C., Dickens, G. R. & Zeebe, R. E. An early cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature451, 279–283 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans, D., Brugger, J., Inglis, G. N. & Valdes, P. The temperature of the deep ocean is a robust proxy for global mean surface temperature during the cenozoic. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol.39 (2024).

- 4.Burke, K. D. et al. Pliocene and Eocene provide best analogs for near-future climates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.115, 13288–13293 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin, J. M. & Meybeck, M. Elemental mass-balance of material carried by major world rivers. Mar. Chem.7, 173–206 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Meknassi, S. et al. Sr isotope ratios of modern carbonate shells: good and bad news for chemostratigraphy. Geology46, 1003–1006 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. & Fiske, G. J. A continental perspective of the seawater 87Sr/86Sr record: a review. Chem. Geol.510, 140–165 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans, D., Bhatia, R., Stoll, H. & Müller, W. LA-ICPMS Ba/Ca analyses of planktic foraminifera from the Bay of Bengal: implications for late pleistocene orbital control on monsoon freshwater flux. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst.16, 2598–2618 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillikin, D. P. et al. Barium uptake into the shells of the common mussel (Mytilus edulis) and the potential for estuarine paleo-chemistry reconstruction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta70, 395–407 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weldeab, S., Lea, D. W., Schneider, R. R. & Andersen, N. 155,000 years of west African monsoon and ocean thermal evolution. Science316, 1303–1307 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCulloch, M. et al. Coral record of increased sediment flux to the inner great barrier reef since European settlement. Nature421, 727–730 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark, G. R. Growth lines in invertebrate skeletons. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci.2, 77–99 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keating-Bitonti, C. R., Ivany, L. C., Affek, H. P., Douglas, P. & Samson, S. D. Warm, not super-hot, temperatures in the early eocene subtropics. Geology39, 771–774 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivany, L. C. et al. Intra-annual isotopic variation in venericardia bivalves: implications for early eocene temperature, seasonality, and salinity on the US Gulf Coast. J. Sediment. Res.74, 7–19 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sessa, J. A., Ivany, L. C., Schlossnagle, T. H., Samson, S. D. & Schellenberg, S. A. The fidelity of oxygen and strontium isotope values from shallow shelf settings: implications for temperature and age reconstructions. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.342–343, 27–39 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todd, J. A. & Harper, E. M. Stereotypic boring behaviour inferred from the earliest known octopod feeding traces: early eocene, southern England. Lethaia44, 214–222 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piccoli, G., Priabona, I., Garoowe, S., Nanggulan, J. & Savazzi, E. Five shallow benthic faunas from the Upper Eocene (Baron, France; Takashima, Japan). Bollettino della Soc. Paleontol. Ital.22, 31–47 (1984).

- 18.Knox, R. et al. Petroleum Geological Atlas of the Southern Permian Basin Area—Overview SPB-Atlas Project—Organisation and Results 211–224 (eds Doornenbal, J. C.) (EAGE Publ, 2010).

- 19.Voerkelius, S. et al. Strontium isotopic signatures of natural mineral waters, the reference to a simple geological map and its potential for authentication of food. Food Chem.118, 933–940 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gale, A. S., Jeffery, P. A., Huggett, J. M. & Connelly, P. Eocene inversion history of the Sandown Pericline, Isle of Wight, southern England. JGS156, 327–339 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gély, J. P. & Merle, D. La Stratigraphie et la paléogéographie du Lutétien en France. Stratotype Lutétien 182–227 (2008).

- 22.Sanders, M. T., Merle, D. & Villier, L. The molluscs of the Falunière of Grignon (Middle Lutetian, Yvelines, France): quantification of lithification bias and its impact on the biodiversity assessment of the Middle Eocene of Western Europe. Geodiversitas37, 345–365 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.McArthur, J. M., Howarth, R. J. & Shields, G. A. The Geologic Time Scale 127–144 (eds Grabstein, F. M.) (Elsevier, 2012).

- 24.Grabstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., Schmitz, M. D. & Ogg, G. M. (eds) The Geologic Time Scale (Elsevier, 2012).

- 25.Liu, Y. W., Aciego, S. M. & Wanamaker, A. D. Environmental contrals on the boron and strontium isotopic compostion of aragonoitic shell material of cultured Arctica islandica. Biogeociences12, 1 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobra, K. S., Capo, R. C., Stewart, B. W. & Haag, W. R. Controls on the barium and strontium isotopic records of water chemistry preserved in freshwater bivalve shells. Environ. Sci. Technol.58, 1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayfield, K. K. et al. Groundwater discharge impacts marine isotope budgets of Li, mg, ca, Sr, and Ba. Nat. Commun.12, 148 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevenson, R., Pearce, C. R., Rosa, E., Hélie, J. F. & Hillaire-Marcel, C. Weathering processes, catchment geology and river management impacts on radiogenic (87Sr/86Sr) and stable (δ88/86Sr) strontium isotope compositions of Canadian boreal rivers. Chem. Geol.486, 50–60 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, J. P., Bullen, T. D., Brabander, D. J. & Olsen, C. R. Strontium isotope record of seasonal scale variations in sediment sources and accumulation in low-energy, subtidal areas of the lower Hudson River Estuary. Chem. Geol.264, 375–384 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbard, P. L. & Lewin, J. The history of the major rivers of southern Britain during the tertiary. JGS160, 829–845 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Müldner, G., Frémondeau, D., Evans, J., Jordan, A. & Rippon, S. Putting South-West England on the (strontium isotope) map: a possible origin for highly radiogenic 87Sr/86Sr values from southern Britain. J. Archaeol. Sci.144, 105628 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis, A. G. & Elliott, G. F. The palaeogeography of the London Clay Sea. Proc. Geol. Assoc.68, 255–277 (1957).

- 33.Doornenbal, J. C., Abbink, O. A., Pagnier, H. & van Wees, J. D. (eds) Petroleum Geological Atlas of the Southern Permian Basin Area—Overview SPB-Atlas Project—Organisation and Results (EAGE Publ, 2010).

- 34.King, C. The Stratigraphy of the London Clay and Associated Deposits (Backhuys, 1981).

- 35.Huyghe, D., Lartaud, F., Emmanuel, L., Merle, D. & Renard, M. Palaeogene climate evolution in the Paris Basin from oxygen stable isotope (δ18O) compositions of marine molluscs. JGS172, 576–587 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Briard, J. et al. Seawater paleotemperature and paleosalinity evolution in neritic environments of the Mediterranean margin: insights from isotope analysis of bivalve shells. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.543, 1 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larue, J. P. The status of ravine-like incisions in the dry valleys of the pays de Thelle (Paris basin, France). Geomorphology68, 242–256 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gély, J. P. & Lorenz, C. Analyse séquentielle de l’Eocène et de l’Oligocène du bassin Parisien (France). Rev. Inst. Fr. Pét.46, 713–747 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marchegiano, M. & John, C. M. Disentangling the impact of global and regional climate changes during the middle eocene in the hampshire basin: new insights from carbonate clumped isotopes and ostracod assemblages. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol.37, 1 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark, A. J., Vellekoop, J. & Speijer, R. P. Hydrological differences between the Lutetian Paris and Hampshire basins revealed by stable isotopes of conid gastropods. BSGF Earth Sci. Bull.193, 3 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zacke, A. et al. Surface-water freshening and high-latitude river discharge in the Eocene North Sea. JGS166, 969–980 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kniest, J. F. et al. Dual clumped isotopes from Mid-eocene bivalve shell reveal a hot and summer wet climate of the Paris Basin. Commun. Earth Environ.5, 1 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gillikin, D. P., Lorrain, A., Paulet, Y. M., André, L. & Dehairs, F. Synchronous barium peaks in high-resolution profiles of calcite and aragonite marine bivalve shells. Geo-Mar. Lett.28, 351–358 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatch, M. B. A., Schellenberg, S. A. & Carter, M. L. Ba/Ca variations in the modern intertidal bean clam Donax gouldii: an upwelling proxy? Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.373, 98–107 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marali, S. et al. Ba/Ca ratios in shells of Arctica islandica—potential environmental proxy and crossdating tool. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.465, 347–361 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markulin, K. et al. Trace and minor element records in aragonitic bivalve shells as environmental proxies. Chem. Geol.507, 120–133 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stecher, H. A., Krantz, I. I. I., Lord, D. E., Luther, C. J. I. I. I., Bock, K. W. III & G. W., & Profiles of strontium and barium in Mercenaria mercenaria and Spisula solidissima shells. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 60, 3445–3456 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poulain, C. et al. An evaluation of Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca, and Ba/Ca ratios as environmental proxies in aragonite bivalve shells. Chem. Geol.396, 42–50 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan, L. H. et al. Radium and barium at GEOSECS stations in the Atlantic and Pacific. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.32, 258–267 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao, L., Schöne, B. R. & Mertz-Kraus, R. Controls on strontium and barium incorporation into freshwater bivalve shells (Corbicula fluminea). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.465, 386–394 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monnin, C., Jeandel, C., Cattaldo, T. & Dehairs, F. The marine barite saturation state of the world’s oceans. Mar. Chem.65, 253–261 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mete, Ö. Z. et al. Barium in seawater: dissolved distribution, relationship to silicon, and barite saturation state determined using machine learning. Earth Syst. Sci. Data15, 4023–4045 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brennan, S. T., Lowenstein, T. K. & Cendon, D. I. The major-ion composition of cenozoic seawater: the past 36 million years from fluid inclusions in marine halite. Am. J. Sci.313, 713–775 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evans, D. et al. Eocene greenhouse climate revealed by coupled clumped isotope-Mg/Ca thermometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.115, 1174–1179 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Todd, J. A. The stratigraphy and correlation of the selsey formation and Barton Clay Formation (M. Eocene) of Studley Wood, Hampshire. Tertiary Res.12, 37–50 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 56.King, C., Gale, A. S. & Barry, T. L. A Revised Correlation of Tertiary Rocks in the British Isles and Adjacent Areas of NW Europe (The Geological Society of London, 2016).

- 57.Steurbaut, E. & Nolf, D. The Mont-des-Récollets section (N France): a key site for the Ypresian-Lutetian transition at mid-latitudes—reassessment of the boundary criterion for the base-lutetian GSSP. Geodiversitas43, 1 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schuler, M. et al. The Paleogene of the Paris and Belgian basins. Standard-stages and regional stratotypes. Cahiers De Mircopaléontol.7, 29–92 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Winter, N. J. et al. The giant marine gastropod Campanile giganteum (Lamarck, 1804) as a high-resolution archive of seasonality in the eocene greenhouse world. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst.21 (2020).

- 60.Dominici, S. & Zuschin, M. Palaeocommunities, diversity and sea-level change from middle Eocene shell beds of the Paris Basin. JGS173, 889–900 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Evans, D. & Müller, W. Automated extraction of a five-year LA-ICP-MS trace element data set of ten common glass and carbonate reference materials: long-term data quality, optimisation and laser cell homogeneity. Geostand. Geoanal. Res.42, 159–188 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jochum, K. P. et al. Nano-powdered calcium carbonate reference materials: significant progress for microanalysis? Geostand. Geoanal. Res.43, 595–609 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sekimoto, S. et al. Neutron activation analysis of carbonate reference materials: coral (JCp-1) and giant clam (JCt-1). J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem.322, 1579–1583 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nier, A. O. The isotopic constitution of strontium, barium, bismuth, thallium and mercury. Phys. Rev.54, 275–278 (1938). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steiger, R. H. & Jäger, E. Subcommission on geochronology: convention on the use of decay constants in geo- and cosmochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett.36, 359–362 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rankenburg, K. Doctoral dissertation. Geothe-University (2002).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository (zenodo.org/records/14178112).