Abstract

Understanding precise structures of two-/three- dimensional (2D/3D) covalent organic polymers (COPs) through single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis is important. However, how to grow high-quality single crystals for 2D/3D COPs is of challenge due to poor reversibility and difficult self-correction of covalent bonds. In addition, the success of introducing tellurium into the backbone to construct 2D/3D COPs and obtaining their single crystals is rare. Here, utilizing the strategy that a heavy element (e.g., tellurium) can form dynamic linkages with a self-correction function, we develop a fast and universal method for growing large-sized single crystals (up to 500 µm) for 2D/3D COPs, especially for 2D COPs. Three 2D COPs and one 3D COP are harvested through dynamic -Te-O-P- bonds in two days, with structures clearly uncovered via the SCXRD analysis. These 2D/3D COPs also show promising photocatalytic activities (nearly 100% selectivity and 100% yield) in superoxide anion radical-mediated coupling of (arylmethyl)amines.

Subject terms: Photocatalysis, Polymers, Polymers

Understanding precise structures of two-/three- dimensional covalent organic polymers through single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis is interesting however, to grow high-quality single crystals of these materials is challenging. Here, the authors incorporate tellurium into the backbones covalent organic polymers as a concise and fast method to grow large single crystals.

Introduction

Accurate atomic-level information on two-/three- dimensional (2D/3D) covalent organic polymers (COPs), including covalent organic frameworks (COFs) that are a special kind of COPs with pores, is crucial to help design high-performance 2D/3D COPs for applications in catalysis, separation, energy storage and conversion, optoelectronics, and biosystems1–6. However, most 2D/3D COPs appear as polycrystalline or poorly crystalline powders due to the wrong or defective assembly of building units during synthesis. Although some 2D/3D COPs structures can be obtained through electron diffraction or the modeling of powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)7–11, atomic positions, bond lengths and angles, molecular interactions, and connecting methods of building units might not be precise enough for us to grasp the knowledge of structure-property relationships as well as kinetics and driving forces during 2D/3D COPs crystallization. Thus, it is necessary to grow high-quality single crystals of 2D/3D COPs with suitable sizes for single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis.

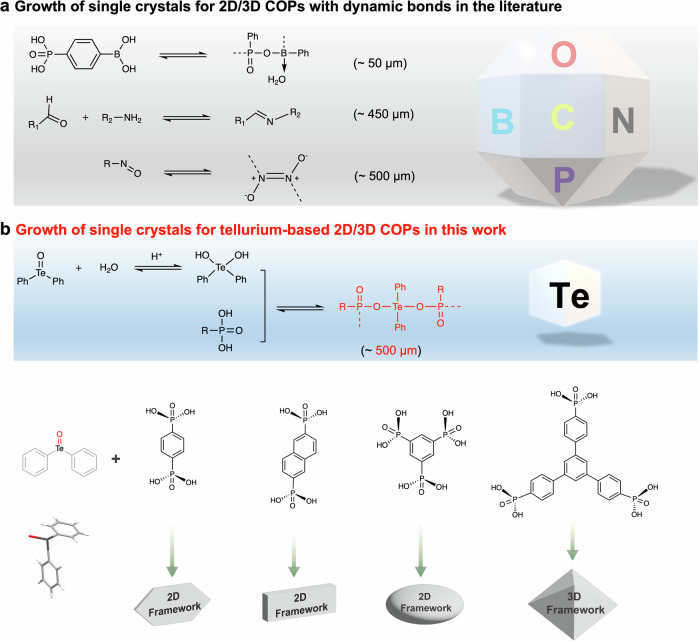

The challenge to growing large 2D/3D COPs single crystals is how to self-correct the wrong or defective assembly of building units. Such self-correction strongly depends on dynamic bonds. Among all the reported 2D/3D COPs with dynamic bonds, three kinds of dynamic linkages (-P-O-B-, -C = N- and -N(O) = N(O)-) can allow the growth of large single crystals for SCXRD analysis (Fig. 1a)12–17. However, up to date, the number of reported 2D/3D COPs constructed by dynamic bonds with confirmed structures via SCXRD is ~ 20, to the best of our knowledge, especially among which the number of 2D COFs constructed via dynamic bonds is only 1. Thus, developing dynamic linkages to enlarge this number is desirable and can bring new functions into 2D/3D COPs. Considering that heavy atoms can form weak or dynamic covalent bonds, we put forward a hypothesis that using heavy atoms to construct 2D/3D COPs may be beneficial to the formation of large single crystals.

Fig. 1. Large-sized single-crystal 2D/3D COPs with dynamic bonds.

a Reported linkages for 2D/3D COPs with confirmed structures via SCXRD analysis and the largest crystal sizes in each kind of 2D/3D COPs. b The linkage for 2D/3D COPs with high-quality single crystals and design ideas for this work.

Since tellurium (Te), the heaviest non-radioactive member of the chalcogen family, has been employed to construct inorganic covalent polymers18,19, it should be a good candidate to form reversible bonds for the construction of single-crystal 2D/3D COPs. Our group recently demonstrated that the tellurium-based material (containing Te=O groups) could form dynamic bonds (-Te-O-P-) with phosphoric acid to produce chiral one-dimensional polymers20. This success strongly inspires us to employ dynamic -Te-O-P- bonds to grow large 2D/3D COPs single crystals. By reacting tellurinyldibenzene (TeDB) with four different organic phosphonic acids, three 2D COP single crystals (named CityU-17, 18, 19) and one 3D COP single crystals (named CityU-20) are obtained in two days (Fig. 1b). These high-quality and large-sized crystals (up to 500 µm) allow the data collection with SCXRD (the resolution up to 0.83 Å) to uncover their accurate and detailed structure information. Furthermore, these 2D/3D COPs have been demonstrated to show promising photocatalytic activity in superoxide anion radical-mediated coupling of (arylmethyl)amines. Among them, CityU-18 and CityU-20 show nearly 100% selectivity and yield for oxidative coupling of benzylamine as photocatalysts. Our strategy not only develops a dynamic bond to construct 2D/3D COPs but also enriches the family of 2D/3D COPs. The success of preparing large single crystals of 2D/3D COPs might provide some guidance for the future growth of large single crystals of COFs.

Results

Synthesis and structure analysis of 2D/3D COPs single crystals

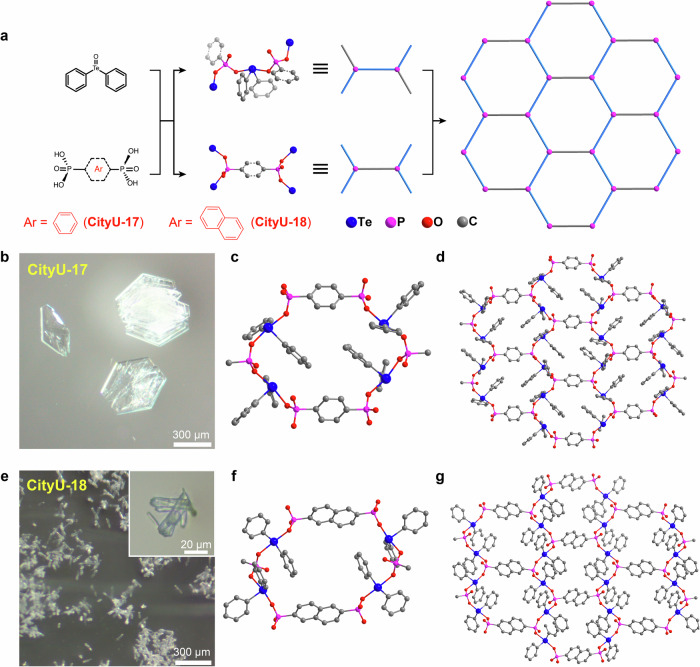

Following our previous success in obtaining chiral inorganic covalent polymers via a reaction between TeDB and H3PO4, we want to know the possibility of preparing 2D/3D COPs single crystals if H3PO4 is replaced with organic phosphonic acids. When 1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) is employed to react with TeDB, hexagonal colorless crystals (CityU-17) with a size of up to 500 µm are formed (Fig. 2a, b). SCXRD analysis with a resolution up to 0.83 Å discloses that CityU-17 is a 2D COP with repetitive linkages (-Te-O-P( = O)-), proving our hypothesis is feasible. The space group of CityU-17 is P21/c with an asymmetric unit containing four Te(phenyl)2 units, two 1,4-phenyl (PO3)2 moieties, and three guest molecules (one monomer 1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) and two solvent molecules ethanol, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1, 2, and 3). Each phosphite group (PO3) in the ligand connects two other ligands through Te atoms to form a 4-connected node, and these units further link together through -O-Te-P- bonds to generate a 2D hexagonal layer structure (Fig. 2c, d). In addition, the organic ligand (1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid)) and ethanol solvent display strong guest-host interactions within the framework. Supplementary Fig. 2 provides a detailed investigation of guest-host interaction in CityU-17. It reveals that there exist hydrogen bonding interactions (O-H···O = P distance of 1.656 Å-1.755 Å) between guest 1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) and the frameworks, as well as H-O···H-C interactions with the distance of 1.631 Å between building units and guest molecules (ethanol). Meanwhile, C-H···O = P (distance of 1.689 Å) interactions are found in solvent molecules (ethanol) and the framework. As a result, the guests (1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) and ethanol) are closely arranged between layers of the framework through guest-host interactions, generating a pseudo-3D structure (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Single crystals of CityU-17 and CityU-18.

a Growth of single-crystal CityU-17 and CityU-18. b Optical microscopic image for CityU-17. c Partial enlargement of CityU-17 to clarify the connection in the 2D framework. d Single-crystal structure of CityU-17. e Optical microscopic image for CityU-18. f, Partial enlargement of CityU-18 for clarifying the connection in the 2D framework. g Single-crystal structure of CityU-18. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

If 1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) is replaced with naphthalene-2,6-diylbis (phosphonic acid), rectangular colorless crystals (named CityU-18) with the size of 80 ~ 100 µm were obtained under a similar reaction condition (Fig. 2e). CityU-18 crystallized in the space group C2/c with an asymmetric unit containing one Te(phenyl)2 unit and a half naphthalene-2,6-(PO3)2 moiety (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 1, 4, and 5). In CityU-18, the connection type between Te and phosphite ligand is almost the same as that in CityU-17, which makes CityU-18 exhibit a 2D structure isomorphic to CityU-17 (Fig. 2f, g, and Supplementary Fig. 5).

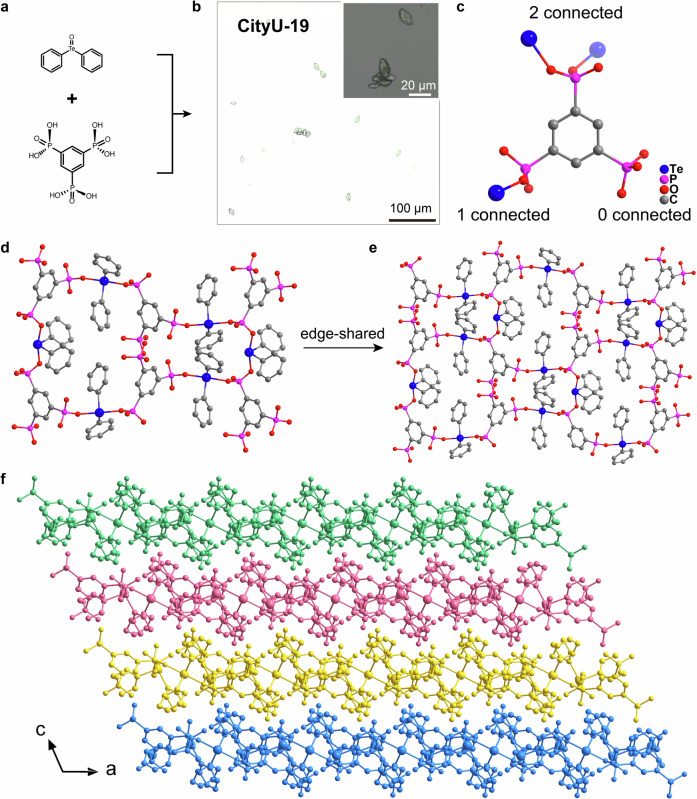

To verify the universality of this construction strategy, we further extend the configuration of the phosphite ligands (e.g., benzene-1,3,5-triyltris (phosphonic acid)). Using a similar method, CityU-19 crystalizes in elliptic colorless crystals with an average size of 30 ~ 50 µm (Fig. 3a, b). The space group of CityU-19 is determined to be C2/c with an asymmetric unit consisting of one benzene-1-[PO3]-3-[HPO3]-5-[H2PO3] moiety and 1.5 crystallographic independent Te(phenyl)2 units (Supplementary Fig. 6, and Supplementary Table 6, 7, and 8). These positions of H atoms of [HPO3] and [H2PO3] units are also determined through the different bond lengths of HO-P (1.530, 1.535 and 1.543 Å) and O = P (1.497 and 1.503 Å) (Supplementary Table 7). In this structure, six Te(phenyl)2 units and six benzene-1-[PO3]-3-[HPO3]-5-[H2PO3] moieties formed bowling-shaped macrocycles (Fig. 3c, d). Then, these bowling-shaped macrocycles constituted a 2D COP via an edge-shared manner (Fig. 3e, f, and Supplementary Fig. 7). The detailed analyses show that only three OH groups in the molecule of benzene-1,3,5-triyltris (phosphonic acid) are reacted with tellurinyldibenzene, and another three OH groups are left unreacted. The existence of unreacted OH groups may be caused by the large steric hindrance of tellurinyldibenzene on the small size of 1,3,5- tri-substituted benzene ring after some OH groups have already reacted.

Fig. 3. Single crystals of CityU-19.

a Growth of single-crystal CityU-19. b Optical microscopic image for CityU-19. c The detailed covalent connecting method in CityU-19. d Bowling-shaped macrocycle in the single-crystal structure of CityU-19. e Single-crystal structure of CityU-19. f, The packing diagram between different layers of CityU-19. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

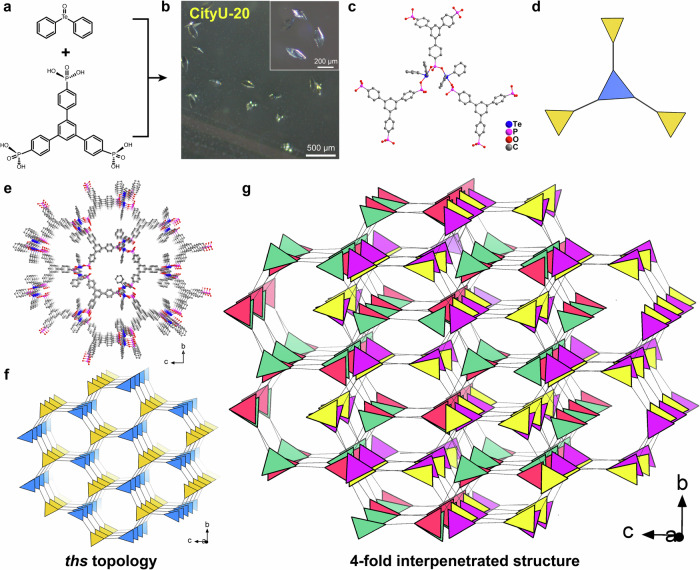

Furthermore, a larger organic ligand, 1,3,5-tris (4-phosphonophenyl) benzene, is used to produce CityU-20, single crystals with sizes larger than 200 µm (Fig. 4a, b). The space group of CityU-20 was determined as Fddd with an asymmetric unit containing two Te(phenyl)2 units and one benzene-1-[4-phenyl-PO3]-3,5-[4-phenyl-HPO3]2 moiety (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 9 and 10). Compared to benzene-1,3,5-triyltris (phosphonic acid) in CityU-19, the larger size and smaller spatial site resistance of the ligand in CityU-20 allow more phosphate groups to react with TeDB. Every two Te(phenyl)2 units and three phosphite groups form a triangular configuration of a 3-connection node (Fig. 4c, d). Every ligand is connected to three such nodes, and ultimately forms a 4- interpenetrated ths topology structure (Fig. 4e, f, g, and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Fig. 4. Single crystals of CityU-20.

a Growth of single-crystal CityU-20. b The optical microscopic images of CityU-20. c The detailed covalent connection of CityU-20. d Simplified diagram for clarifying the covalent connection in single-crystal of CityU-20. e ~ g Crystal structures and topological structures of CityU-20. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and mapping, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses are employed to further confirm the structures of these frameworks. SEM micrographs and the corresponding mappings suggest that these crystals contain carbon, oxygen, phosphorus, and tellurium elements (Supplementary Fig. 10). Meanwhile, according to FTIR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 11), the peaks in the range of 800-570 cm−1 and the peaks in the range of 950-850 cm−1, respectively, come from the stretching of Te-O bonds and P-O bonds in these frameworks19,20, further proving the formation of the linkage (-Te-O-P( = O)-) in these frameworks. PXRD characterization was carried out to confirm that all single crystals and accordingly bulk are in the same phase. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, these data from bulk samples match well with their simulated powder diffraction pattern from single-crystal diffraction data of CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19, and CityU-20, respectively, proving their high phase purity. In addition, according to the simulation calculation results based on the SCXRD data and the experimental data, the refined PXRD patterns fitted well to those in experiments with satisfying agreement factors (Supplementary Fig. 13), which further implies the phase purity of these four materials.

Stability and photocatalytic application

After being immersed in and washed with common solvents such as dichloromethane, hexane, methanol, 1,4-dioxane, dimethylformamide, water, and ethanol in turn for 30 min, all crystals remained insoluble and maintained their original crystallinity (Supplementary Fig. 12). Besides, thermal gravimetric analyses (TGA) indicate their high thermal stability (larger than 300 °C by considering 5% weight loss temperature (Td); Td = 340 °C, 344 °C, 353 °C, and 347 °C for CityU-17, 18, 19, and 20, respectively, Supplementary Fig. 13). The slight weight loss of CityU-17 around 240 °C could be attributed to the decomposition of the guest molecules (1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) and ethanol) in the framework. The light absorption of four compounds is studied using ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy (Fig. 5b). The absorption wavelengths of CityU-17 and CityU-18 are mainly in the range of 230-380 nm and 240-400 nm, respectively. The slight red-shift absorption of CityU-18 is caused by the larger conjugation of naphthalenyl parts in the CityU-18 than phenyl parts in the CityU-17. The absorptions of CityU-19 and CityU-20 are mainly located in the range of 230-457 nm and 280-420 nm, respectively. Accordingly, the band gaps for CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19, and CityU-20 were calculated to be 3.39 eV, 3.26 eV, 2.75 eV, and 2.95 eV, respectively.

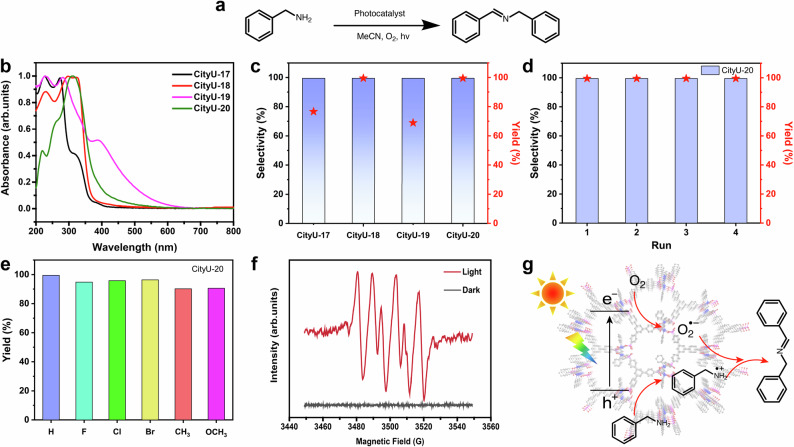

Fig. 5. Photocatalytic performance.

a CityU-17, 18, 19, and 20 catalyzed the aerobic oxidation from amines to imines (acetonitrile (abbreviation, MeCN)). b UV-vis spectra of CityU-17, 18, 19, and 20. c Photocatalytic performance of CityU-17, 18, 19, and 20. d Cycle experiment of aerobic oxidation of benzylamine with CityU-20 as photocatalyst. e Photocatalytic performance for CityU-20 catalyzed the aerobic oxidation of benzylamine derivatives. f EPR signals of the reaction solution under light irradiation and the dark with DMPO as the spin-trapping reagent. g Schematic diagram of the photocatalytic process.

Inspired by the above UV-Vis results and the metalloid property of tellurium element, we speculate that CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19, and CityU-20 could absorb UV-visible light energy and be a possible energy-reservoir, suggesting that these frameworks might exhibit photocatalytic performance. As shown in Fig. 5a, we focus on the photocatalytic activities in superoxide anion-mediated coupling of arylmethyl amines to explore the photocatalytic performance of these frameworks. Firstly, 10 mg fresh samples of CityU-17 ~ 20 crystals are used as photocatalysts in the system of 3 mL acetonitrile (CH3CN) as the solvent and 0.1 mmol benzylamine as substrate. Then, the reaction is performed under an oxygen atmosphere at room temperature, irradiating with a xenon lamp of the light source (320-780 nm). The yield and selectivity of the products for the reaction are determined by gas chromatography (GC) spectrometry.

After a 10-hour reaction, all four materials showed satisfying performance as photocatalysts for the oxidation of primary amines to imines. Among them, CityU-18 and CityU-20 exhibit performance with nearly 100% selectivity and 100% yield (Fig. 5c). Additionally, no noticeable alteration appeared in the PXRD spectra of CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19 and CityU-20 after photocatalytic reactions (Supplementary Fig. 15), which implies that the structures of these four materials remained unchanged after photocatalytic reactions. Notably, CityU-20 maintains sustained photocatalytic activity after five runs of the catalytic reaction (Fig. 5d). In addition, several derivatives of benzylamine as substrates are further studied under the same condition with CityU-20 as the photocatalyst (Fig. 5e). When the substrates decorate with electron-withdrawing groups such as p-F, p-Cl, p-Br, the targeted yields can keep between 95% ~ 100%. When the substrate contains electron-donating groups such as p-CH3 and p-OCH3, the targeted yield has a slight decrease but still can reach 90%. To further demonstrate the superiority of photocatalytic performance for CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19 and CityU-20, the linkers (tellurinyldibenzene (T1), 1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) (L1), naphthalene-2,6-diylbis (phosphonic acid) (L2), benzene-1,3,5-triyltris (phosphonic acid) (L3) and 1,3,5-tris (4-phosphonophenyl) benzene (L4)) used to synthesize them were adopted as photocatalysts under the same photocatalytic reaction conditions. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16 and Table S11, the performance using CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19 or CityU-20 as photocatalysts is much better than that using their linkers under the same reaction conditions, further illustrating the promising photocatalytic ability of these materials.

To elucidate the reaction mechanism, in-situ electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy of CityU-20 is further exploited. As shown in Fig. 5f, there is no obvious signal in the oxygen atmosphere under dark conditions. However, after 30 min of illumination, the signals of superoxide radical (O2•-) appear clearly with the presence of 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO), indicating that CityU-20 can activate oxygen molecules to superoxide radicals in a short time under light irradiation for the subsequent oxidation of the substrates to products (Fig. 5g). Furthermore, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to further understand the differences in photocatalytic performance among these four materials. For the oxidative coupling reaction of benzylamines, the adsorption capacity of the materials for the reactant molecules is a crucial factor affecting the reaction activity21–23. The calculation results indicated that the adsorption energy barriers of O2 are 2.61 eV (CityU-17), 1.30 eV (CityU-18), 2.94 eV (CityU-19), and 1.29 eV (CityU-20), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 17 and 19). Meanwhile, the adsorption energy barriers of benzylamine are -0.63 eV (CityU-17), -0.93 eV (CityU-18), -0.64 eV (CityU-19), and -1.39 eV (CityU-20), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18 and 19). The adsorption energy reflects the difficulty of the adsorption of reactant molecules on the active sites. A lower adsorption energy value indicates a more stable adsorption state. These results indicate that in the structures of CityU-18 and CityU-20, O2 and benzylamine are more likely adsorbed onto the surface of these materials to form the benzylamine radical cation and O2•-, thereby promoting the coupling reaction, which is consistent with the experimental results.

Discussion

Here, we introduce a heavy element (tellurium) to form dynamic covalent bonds for the fast construction of 2D/3D COPs single crystals for SCXRD analysis. This strategy can overcome the dilemma of general covalent bonds, which are too irreversible to realize the error-correction during the crystal growth of 2D/3D COPs. The detailed structure information of three 2D COPs and one 3D COP has been precisely uncovered via SCXRD analysis, which provides us with a solid understanding of their structure-property relationship. These 2D/3D COPs have been demonstrated as promising photocatalysts for superoxide anion-mediated coupling of arylmethyl amines. Based on the results, our method is universal for fast-growing large-sized single crystals for 2D/3D COPs, especially for 2D COPs. Our work successfully introduced tellurium into the backbone of 2D/3D COPs and obtained their single crystals. Our finding broadens the diversity of traditional 2D/3D COPs and opens up a road to constructing 2D/3D COPs and their single crystals.

Methods

All raw materials are commercially available and bought from Dieckmann (Hong Kong) Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. The purities for commercial chemicals are > 97%, and they are used without further purification. All solvents are purchased from Anaqua (Hong Kong) Company Limited.

NMR characterization was performed on the Bruker Avance-400 spectrometers (400 MHz for 1H, 101 MHz for 13C). Chemical shifts (δ) were reported in parts per million (ppm) with the following abbreviation to describe peak splitting patterns (m = multiplet). TMS was used as an internal standard.

SCXRD characterization was conducted on the Rigaku X-ray Single Crystal Diffractometer System (Rigaku SmartLab 9kW-Advance) at 150 K. The crystal structures for CityU-17, 18, 19, and 20 were solved and refined by full-matrix least-squares methods against F2 with the SHELXL-2014 program package24,25 and Olex-2 software26. The topological analysis was carried out on the TOPOS program27. PXRD data were collected by Rigaku X-ray Diffractometer SmatlabTM 9 kW at room temperature.

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra from 4000 to 400 cm-1 were performed on a Perkin Elmer Spectrum II. UV-vis spectra in the range of 200-800 nm were collected by the Hitachi UH4150 UV-VIS-NIR Spectrophotometer. Optical pictures of these crystals were taken by the Zeiss microscope. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) and elemental mappings were carried out on the Thermo Fisher Quattro S Environmental SEM.

Thermal gravimetric analyses (TGA) data were measured by a Perkin-Elmer Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer STA 6000 under nitrogen flow (20 mL/min) with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker EMXnano spectrometer. The product of the photocatalytic oxidation reaction was detected and analysed via gas chromatography (with mode GC, 8890, Agilent).

The crystals of CityU-17, 18, 19, and 20 were soaked in and washed with dichloromethane, hexane, methanol, 1,4-dioxane, dimethylformamide, deionized water, and ethanol for 30 mins in turn. Then, these crystals were dried under a vacuum. The solvent-treated, washed, and dried crystals were further used for measurements of PXRD, FTIR, TGA, UV-Vis, EPR, and photocatalyst properties. SCXRD measurement was carried out with a crude suspension. That is, the as-synthesized single crystals were picked up directly from a crude suspension for SCXRD measurements. The optical microscopy, SEM, and mapping were carried out with a crude suspension after gentle sonication and solution replacement with ethanol. Pawley-refined and relevant simulations were conducted via Materials Studio (MS).

The density functional theoretical calculation results were calculated using GaussView6.0 and Gaussian16. The structures of CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19 and CityU-20 are derived from single crystal structure data. The necessary structural parts are selected, including Te atoms and their adjacent organic ligand structures, and the ends of the structures are saturated with H atoms. M06-2X functional and def2-SVP basis sets are selected for structural optimization and energy calculation. All calculations were performed using DFT-D3(BJ) dispersion correction to describe the dispersion of structure.

Synthesis of CityU-17

Tellurinyldibenzene (15.0 mg, 0.05 mmol), 1,4-phenylenebis (phosphonic acid) (5.0 mg, 0.021 mmol) and 100 μL acetic acid dissolved in a mixture solvent containing 0.7 ml of absolute ethanol and 0.2 mL of 1,4-dioxane. After ultrasonicated for 3 minutes, the glass ampoule was frozen in an aqueous liquid nitrogen bath and evacuated three times before being sealed under a vacuum atmosphere. After heating at 100 °C for 2 days, large-sized colorless crystals were formed in the glass ampoule. Then, the glass ampoule was cooled to room temperature, and crystals were collected through filtration. These crystals were further soaked in and washed with dichloromethane, hexane, methanol, 1,4-dioxane, dimethylformamide, deionized water, and ethanol in turn. After drying under a vacuum, CityU-17 crystals were obtained (15.5 mg, yield 77.5%).

Synthesis of CityU-18

Tellurinyldibenzene (15.0 mg, 0.05 mmol), naphthalene-2,6-diylbis (phosphonic acid) (6.0 mg, 0.021 mmol) and 100 μL acetic acid dissolved in a mixture solvent of 0.7 ml of absolute ethanol and 0.2 mL of 1,4-dioxane. Following the similar procedure to that of CityU-17, CityU-18 was obtained (12.5 mg, yield 59.5%).

Synthesis of CityU-19

Tellurinyldibenzene (12.5 mg, 0.042 mmol), benzene-1,3,5-triyltris (phosphonic acid) (4.4 mg, 0.014 mmol) and 150 μL acetic acid dissolved in a mixture solvent of 0.7 ml of absolute ethanol and 0.2 mL of 1,4-dioxane. The following steps to get CityU-19 (11.0 mg, yield 65.0%) are similar to those of CityU-17.

Synthesis of CityU-20

Tellurinyldibenzene (12.5 mg, 0.042 mmol), 1,3,5-tris (4-phosphonophenyl) benzene (7.3 mg, 0.014 mmol) and 150 μL acetic acid dissolved in a mixture solvent of 0.7 ml of absolute ethanol and 0.2 mL of 1,4-dioxane. Accordingly, we harvested single crystals of CityU-20 (12.8 mg, yield 64.6%) after using a similar procedure to that of CityU-17.

Photocatalysis measurement

10 mg of a photocatalyst (CityU-17, CityU-18, CityU-19, CityU-20, T1, L1, L2, L3, or L4) and 3 mL CH3CN (GR) were placed in a 50 mL quartz tube, and the mixture was degassed with high pure N2/O2 ( > 99.995%, a flow rate of 0.1 L/min) for 5 min. Then, 0.1 mmol of benzylamine was quickly added to the tube under the gas flow. A 300 W Xenon lamp with the light intensity of 200 mW cm−2 and wavelength range of 320-780 nm was used as the light source. The cooling water circulation was used to maintain the reaction temperature at 298 K. After reaction, the solution was centrifuged and filtered via a syringe filter to remove catalyst particles. For photocatalytic cycle measurements, photocatalysts were centrifuged, filtered, recollected, and washed with CH3CN after every reaction and before the next test.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

Q.Z. acknowledges the funding support from the City University of Hong Kong (9380117 and 7020089) Hong Kong, P. R. China. C.-S.L. and Q.Z. thank the funding support from the Innovation and Technology Fund (ITF, ITS/322/22). Q.Z. also thanks the funding support from the State Key Laboratory of Supramolecular Structure and Materials, Jilin University (sklssm2024039), P. R. China.

Author contributions

Q.Z. led the project. Q.Z. and M.X. conceived the idea. M.X. conducted the synthesis and crystal growth of 2D/3D COPs and did the SCXRD, PXRD, UV-Vis, OP, TGA, and in-situ EPR measurements. L.Z., M.X., and Q.D. analyzed the SCXRD data. F.K. and C.-S.L. carried out the FTIR measurement. M.X. and X.W. (Xiang Wang) performed SEM and mapping characterization. Z.C. conducted the DFT calculation. X.W. (Xin Wang) did the Pawley-refined and relevant simulations. L.Z., F.K., and M.X. analyzed the synthesis mechanism. L.Z. and X.-X.L. made the photocatalytic application for 2D/3D COPs under the guidance of Y.-Q.L. Q.Z., M.X., and L.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the manuscript revision.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The crystallographic data reported in this paper are available in the supplementary materials and deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) with CCDC numbers 2339861, 2339863, 2339865, and 2339866. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via “www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif”. All other data generated in this study are provided in the main text or the Supplementary Information. The raw data are available in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Miaomiao Xue, Lei Zhang.

Contributor Information

Ya-Qian Lan, Email: yqlan@m.scnu.edu.cn.

Qichun Zhang, Email: qiczhang@cityu.edu.hk.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-54235-9.

References

- 1.Huang, N., Wang, P. & Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks: a materials platform for structural and functional designs. Nat. Rev. Mater.1, 1–19 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang, S. et al. Covalent organic framework with multiple redox active sites for high-performance aqueous calcium ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 17309–17320 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans, A. M. et al. Seeded growth of single-crystal two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Science361, 52–57 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colson, J. W. et al. Oriented 2D covalent organic framework thin films on single-layer graphene. Science332, 228–231 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue, M. et al. Recent progress in single-crystal structures of organic polymers. J. Mater. Chem. C.10, 17027–17047 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kandambeth, S., Dey, K. & Banerjee, R. Covalent organic frameworks: chemistry beyond the structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 1807–1822 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu, H., Gao, J. & Jiang, D. Stable, crystalline, porous, covalent organic frameworks as a platform for chiral organocatalysts. Nat. Chem.7, 905–912 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Abadía, M. et al. A wavy two-dimensional covalent organic framework from core-twisted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 14403–14410 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin, Y. et al. Single-crystal three-dimensional covalent organic framework constructed from 6-connected triangular prism node. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 22329–22334 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang, F. et al. Construction of crystalline nitrone-linked covalent organic frameworks via kröhnke oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 15465–15472 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Côté, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science310, 1166–1170 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaudoin, D., Maris, T. & Wuest, J. D. Constructing monocrystalline covalent organic networks by polymerization. Nat. Chem.5, 830–834 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gropp, C., Ma, T., Hanikel, N. & Yaghi, O. M. Design of higher valency in covalent organic frameworks. Science370, eabd6406 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou, Z. et al. Growth of single-crystal imine-linked covalent organic frameworks using amphiphilic amino-acid derivatives in water. Nat. Chem.15, 841–847 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu, B. et al. Linkage conversions in single-crystalline covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem.16, 114–121 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma, T. et al. Single-crystal x-ray diffraction structures of covalent organic frameworks. Science361, 48–52 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han, J. et al. Fast growth of single-crystal covalent organic frameworks for laboratory x-ray diffraction. Science383, 1014–1019 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai, Y. et al. Oxidative polymerization in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc.143, 10709–10717 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai, Y. et al. Polytelluoxane: A chalcogen polymer that bridges the gap between inorganic oxides and macromolecules. Chem9, 2006–2015 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue, M. et al. A metal-free helical covalent inorganic polymer: preparation, crystal structure and optical properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.63, e202315338 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu, Q. et al. Achieving high photo/thermocatalytic product selectivity and conversion via thorium clusters with switchable functional ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 18586–18594 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, H., Xu, C., Li, D. & Jiang, H.-L. Photocatalytic hydrogen production coupled with selective benzylamine oxidation over MOF composites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 5379–5383 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, J. A. et al. Porphyrin-metalation-mediated tuning of photoredox catalytic properties in metal-organic frameworks. ACS Catal5, 5283–5291 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C71, 3–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheldrick, G. SHELXT-integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A71, 3–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolomanov, O. V. et al. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr.42, 339–341 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexandrov, E. V., Blatov, V. A., Kochetkov, A. V. & Proserpio, D. M. Underlying nets in three-periodic coordination polymers: topology, taxonomy and prediction from a computer aided analysis of the Cambridge Structural Database. Cryst. Eng. Comm.13, 3947–3958 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The crystallographic data reported in this paper are available in the supplementary materials and deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) with CCDC numbers 2339861, 2339863, 2339865, and 2339866. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via “www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif”. All other data generated in this study are provided in the main text or the Supplementary Information. The raw data are available in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.