Abstract

Commercial activity has positive and negative effects on health. Adverse commercial impacts on health are underpinned by corporate power and economic models and policy that prioritize economic growth, rather than a wellbeing economy that prioritizes health, equity and sustainability. Health in all policies (HiAP) aims to ensure that all policies promote health and health equity, using processes including health impact assessment (HIA). We aimed to explore the potential for HiAP and HIA to help address commercial determinants of health and promote a wellbeing economy. We completed a scoping review to identify how HiAP approaches, including HIA, could address commercial determinants, including challenges and implications for practice. This found synergy between the concepts of wellbeing economy and HiAP. However, corporate interests have sometimes co-opted HiAP to influence policy. We found some examples of HIAs of transnational corporations and international trade and investment agreements. We reviewed HIA frameworks for guidance to practitioners on managing corporate influence. This identified little guidance on identifying and managing corporate and other conflicts of interest or managing power differentials between stakeholders. We also mapped wellbeing economy outcomes against health determinants considered in selected HIA frameworks. This found that HIA frameworks with a comprehensive checklist of health determinants prompt consideration of most wellbeing economy outcomes. HIA could support the transition to a wellbeing economy if applied routinely to economic policies, but ideational change is also needed. HIA frameworks should provide guidance on corporate conflicts of interest and power differentials.

Keywords: commercial determinants of health, wellbeing economy, health impact assessment, health in all policies, social determinants of health, healthy public policy

Contribution to Health Promotion.

We explored whether health impact assessment (HIA) could influence commercial determinants of health.

HIAs have assessed transnational corporations and international trade and investment agreements.

HIA frameworks provide little guidance on commercial determinants but some prompt consideration of most wellbeing economy outcomes.

We advocate using HIA to assess economic policies and provide better guidance for practitioners on corporate conflicts of interest and power differentials.

To prioritize health, equity and sustainability, ideational change is needed to challenge the primacy of economic growth and power imbalance favouring corporate interests.

INTRODUCTION

Commercial determinants of health are the ‘systems, practices and pathways through which commercial actors drive health and equity’ (Gilmore et al., 2023). Commercial activity can promote health and wellbeing, for example by providing essential products and services or good quality employment (Gilmore et al., 2023). However commercial enterprises can have negative health impacts through multiple pathways (Mialon, 2020). Most public health research on commercial determinants has focused on unhealthy commodities, particularly the tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed food industries (de Lacy-Vawdon and Livingstone, 2020; Burgess et al., 2024). This has uncovered industry strategies to promote these commodities, oppose restrictions and shape public understanding to maintain and grow profits (Maani et al., 2022; Burgess et al., 2024). Other unhealthy commodity industries (UCIs) include breast milk substitutes (Robles et al., 2024), gambling (van Schalkwyk et al., 2021), fossil fuels (Friel, 2023), firearms (Maani et al., 2020a), social media (Zenone et al., 2023), mining (Millar, 2013) and the car industry (Douglas et al., 2011).

Adverse health impacts arise from the production and promotion of unhealthy commodities, and commercial activity can also impact health and health equity in other ways (Gilmore et al., 2023). For example, the extraction of raw materials, production and transportation of goods may cause environmental damage (Friel, 2023). Employment with poor safety standards, high job strain and low control or low job security may damage workers’ health (Frank et al., 2023; Rugulies et al., 2023). High pay differentials between executives and workers contribute to income inequality (Gilmore et al., 2023; Lacy-Nichols et al., 2023). Large transnational corporations (TNCs) operating across national borders may reduce their tax liabilities and extract profits and wealth from distant shareholders (Lacy-Nichols et al., 2023). This reduces funding for public services while increasing global and national wealth inequalities. These mechanisms particularly disadvantage people and communities with fewer resources and less power, causing adverse impacts on health, wellbeing and health equity.

These adverse effects are underpinned by corporate power, and by economic models that prioritize profits and economic growth, usually measured as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), above health, equity and planetary wellbeing (McCartney, 2022; Wood et al., 2022; Friel et al., 2023; Gilmore et al., 2023). The roots of commercial determinants lie in the global market-driven economic model and the assumptions shaping that over several decades (Maani et al., 2021; Loewenson et al., 2022; Friel et al., 2023; Gilmore et al., 2023). It has been argued that unrestrained economic growth is now causing more harm than benefits globally—termed ‘uneconomic growth’—so new economic approaches are needed (Hensher et al., 2024). Reversing the harms caused by commercial determinants of poor health should go beyond actions targeting individual corporations or industries, to address the power imbalances and economic systems supporting them (Friel et al., 2023). This means creating a ‘wellbeing economy’ in which the purpose of the economy is human and planetary health and equity rather than GDP growth for its own sake (Cylus and Smith, 2020; McCartney et al., 2022). Several governments have stated an intention to progress towards a wellbeing economy including Scotland, Iceland, New Zealand, Wales, Finland and Canada (Wellbeing Economy Alliance, 2022). This transition demands a change in mindset—challenging economic models, assumptions and norms that prioritize profits above other interests (Hensher, 2023; Trebeck, 2024). It also requires mechanisms to reshape regulations, processes and policies at national and international levels that affect corporate power and public health. These include trade and investment agreements (Barlow et al., 2017), the proposed international tax cooperation framework (United Nations Secretary General, 2023) and an international legally binding instrument on TNCs and human rights (United Nations, 2014).

Health in all policies (HiAP) is advocated as a way to re-orientate the policy environment to give higher priority to health rather than commercial interests (Valentine et al., 2023). HiAP is ‘an approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health and health systems implications of decisions, seeks synergies and avoids harmful health impacts, in order to improve population health and health equity’ (World Health Organization, 2014). HiAP involves partnership between public health and other sectors, to understand and influence the range of ways that a policy could impact health (Green et al., 2021). Explicitly considering health, wellbeing and equity in policy development should enhance their priority, despite commercial and other influences (Valentine et al., 2023). Applied to relevant policies this could help, for example to strengthen the regulation of unhealthy commodities, raise environmental standards, re-orientate taxation policies, improve workers’ rights and increase the transparency of decision-making (Friel et al., 2023).

A common approach to HiAP is using health impact assessment (HIA) (Green et al., 2021). HIA is a systematic, evidence-based and flexible process to assess the likely impacts of a plan or policy in any sector, before implementation, to promote health benefits and prevent or mitigate harmful impacts on health or health equity (Winkler et al., 2021). It also highlights the populations impacted, particularly populations at risk of poor health. HIAs use both quantitative and qualitative methods and involve stakeholders in identifying and assessing impacts (Winkler et al., 2021). Five best practice principles have been defined for HIA: Comprehensive approach to health, sustainability, equity, participation and ethical use of evidence (Winkler et al., 2021; McDermott et al., 2024). These align well with the goals of a wellbeing economy.

HIA has been applied to policies directly addressing unhealthy commodities, such as alcohol licensing policies (Marathon County Health Department, 2011; Health Promotion Agency, 2013; Mongru et al., 2017), tobacco control policy (Costa et al., 2018; Fuertes et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2023), food labelling (Feteira-Santos et al., 2021) and nutritional standards (Lott et al., 2020). HIA can also assess commercial developments—for example infrastructure development and extractive industry projects in low-income countries use HIA to assess whether they are meeting community health and safety standards required by international finance institutions (International Finance Corporation, 2009; Krieger et al., 2013). HIAs have assessed economic policies including employment policies governing pay and working conditions (Cincinnati Health Department Health Impact Assessment Committee, 2011; Human Impact Partners, 2011a), tax credits (Cook et al., 2019) and economic development proposals (Davis et al., 2013; Montachusett Regional Planning Commission, 2013).

HIA can be used for trade agreements, regulations and other policies that directly or indirectly affect the activities and impacts of commercial actors (Labonté, 2019; Townsend et al., 2021). However, HIA could also be subject to commercial influence. Powerful commercial actors have influenced policy norms and assumptions over many decades (Maani et al., 2022). These norms may affect the willingness of policymakers to support HIA, and the priority given to health compared to economic interests when HIAs identify adverse health impacts of corporate activities. Commercial actors may seek involvement as stakeholders in HIAs and influence the findings. Little guidance is available for HIA practitioners to acknowledge and address commercial influences.

This article aims to explore the potential for HiAP, particularly HIA, to help address commercial determinants of health and promote a wellbeing economy. Within this overall aim, it addresses three research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How can HIA or HiAP approaches help to address commercial determinants and what are the implications of commercial determinants for HIA and HiAP practice?

RQ2: What guidance do currently available HIA frameworks provide on managing corporate or other conflicts of interest in HIA?

RQ3: How well do HIA frameworks with a comprehensive checklist of health determinants prompt consideration of wellbeing economy outcomes?

We will present methods and findings for each of these and identify implications for practice and research.

METHODS

We used three methods to address the three research questions. These were: a scoping review of literature for RQ1; a review of HIA frameworks for RQ2 and a mapping of health determinants in selected HIA frameworks against wellbeing economy outcomes for RQ3.

Scoping review of HIA, HiAP and commercial determinants

We undertook a scoping review to address RQ1. A scoping review is appropriate for an overview of relevant literature (Munn et al., 2018) and we intended to capture both conceptual papers and examples including reported outcomes. We used an adapted version of Joanna Briggs Institute scoping reviews methodology (Peters et al., 2020). The protocol including the search strategy is published as a preprint (Douglas et al., 2024).

We searched for peer-reviewed papers on Medline, Embase, Proquest Public Health and Scopus, and for grey literature on websites including public health institutes in several, mostly high-income, countries and international HIA repositories. Our search strategy used terms for corporate or commercial determinants such as ‘corporat* determinant*’ and ‘corporat* power’ and terms for HIA or HiAP. We restricted the search to English with no date limit, with the last search on 28th March 2024. Eligible papers considered explicitly how HIA or HiAP could address commercial determinants and/or implications of commercial determinants for HIA practice. We also searched reference lists of included papers for additional relevant papers. The Supplementary File shows the search strategy and number of results for Ovid Medline, and the grey literature sources searched.

Citations were uploaded onto Covidence for screening and review. One reviewer (M.D.) screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria and those excluded were then checked by a further reviewer (C.F.). Both reviewers assessed the full text of selected citations against the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

We extracted data from the included studies into an Excel template. This captured: Citation, Setting, Type of paper, Scope of corporate determinants, Consideration of HiAP, HIA or both, Focus and Summary of key points. We did not critically appraise papers as we aimed to identify concepts, perspectives and relevant examples, rather than assess their validity. We grouped papers by focus and summarized findings narratively.

Review of HIA frameworks for guidance on managing corporate influence

To address RQ2, we reviewed HIA frameworks. In a previous 2022 review, we identified 24 English language HIA frameworks published since 2012 or being used in current practice. The review methods are published elsewhere (McDermott et al., 2024).

We reviewed HIA frameworks that were publicly available in May 2024 and searched each as follows. Firstly, we carried out a word search for ‘conflict’, ‘corp’, ‘commerc’, ‘transparen’, ‘profit’, ‘power’ and ‘stakeholder’. Then we read through the document, focusing particularly on guidance relating to scoping of the HIA, membership and conduct of the steering group, stakeholder engagement and reporting. Relevant data were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet with the headings: Citation; Conflict of interest; Power differentials between stakeholders; Corporate influence/Profit motive; Transparency; Comments. We defined the headings in advance as topics for which HIA practitioners may need guidance to identify and address corporate and other conflicts of interest. The data extracted were whether the framework provided any comment, and a summary of the guidance provided. Additional relevant information was captured in the comments column. One author (M.D.) reviewed all of the frameworks. A second author (R.M.) independently reviewed a sample of five frameworks and any differences in findings were resolved by discussion.

Findings were synthesized narratively to present whether the HIA frameworks recognized conflicts between health and economic or commercial interests, and the guidance provided on conflicts of interest; corporate interests and corporate stakeholders; power differences between stakeholder groups and transparency.

Mapping of HIA checklists to wellbeing economy outcomes

To address RQ3 we mapped health determinant checklists in selected HIA frameworks against outcomes identified in a published review of wellbeing economy frameworks. The Centre for Thriving Places has published a comparison of eight frameworks defining outcomes for a wellbeing economy (Zeidler et al., 2023). The frameworks reviewed included the Doughnut Economics model, the Thriving Places Index, the UN Sustainable Development goals and others. Some of these include economic growth as one element, which may seem to conflict with the wellbeing economy concept. However, the review concluded that they all promoted a shift from focusing solely on economic growth towards ‘a range of interconnected outcomes that improve lives’. They synthesized findings into a summary set of ‘shared ingredients’ described as ‘the core things that we need to prioritize if the aim is to grow the wellbeing of people and planet’. The report highlights that a wellbeing economy should promote a balance of all the core themes and ingredients. We aimed to assess the congruence between these shared ingredients of a wellbeing economy and the health determinants considered in selected HIA frameworks.

We selected seven HIA frameworks for mapping (Ministry of Health, 2007; International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010; Bhatia, 2011; Cooke et al., 2011; Chadderton et al., 2012; Douglas, 2019; Pyper et al., 2021). These all included a comprehensive table or checklist of prompts to identify potential health determinant impacts of the proposal being assessed. This was intended to show the potential of HIA to support wellbeing economy outcomes but is not representative of all available HIA frameworks, as not all frameworks include a detailed determinants checklist. For these frameworks, we mapped the prompts against the wellbeing economy shared ingredients. We used an Excel spreadsheet containing all the themes and ingredients. For the first two frameworks, three authors (M.D., L.G., L.B.) independently added prompts into the spreadsheet that closely matched each ingredient, and then compared findings. One author (M.D.) then mapped prompts from the other five frameworks and two other authors (L.G., L.B.) checked these findings. Differences were resolved by discussion.

RESULTS

Scoping review of HIA, HiAP and commercial determinants

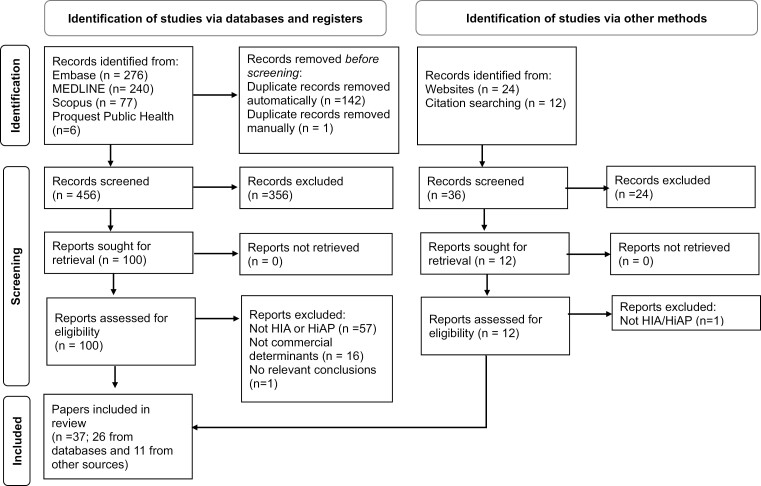

We identified 599 papers from bibliographic databases, 24 from grey literature sources and 12 from citation tracking. After removing duplicates, we screened 492 titles and abstracts and excluded 380 leaving 112 for full text review. We excluded 75 papers that did not meet the eligibility criteria. This left 37 papers in our review. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram.

Fig. 1:

PRISMA flow chart. Figure adapted from the PRISMA 2020 statement (Page et al., 2021).

The included papers were categorized as: 10 perspectives, 9 case studies, 8 reviews, 2 reports, 5 book chapters, 2 qualitative studies and 1 training manual. In 19 papers the setting was global, 9 Australia, 2 Australia and Southern Africa, 3 Europe, 1 Philippines, 1 Canada, 1 Wales and 1 sub-Saharan Africa. Twenty-one papers mainly concerned HIA, 15 mainly HiAP and one discussed both equally. Twelve papers discussed commercial entities or corporations including UCIs, six corporate influence and capture, six trade policy, eight commercial determinants frameworks, four wellbeing economy, one economic policy framing. In eight, the focus was using HIA to research UCIs, nine using HiAP and/or HIA for a wellbeing economy, five using HIA for trade policies, 15 challenges and implications for HIA or HiAP. Supplementary Table S1 presents the characteristics of the included papers.

Using health in all policies to support transition to a wellbeing economy

Although the scoping review focus was commercial determinants rather than wellbeing economy, we found nine papers proposing that HIA and/or other HiAP approaches could help address the roots of commercial determinants by supporting a transition to a wellbeing economy. They highlighted synergies between the aims of HiAP and the wellbeing economy, and the focus on collaboration and multi-sectoral governance (Krech, 2011; Baum et al., 2023; Porcelli et al., 2023; Valentine et al., 2023). Authors argued that public health could support a paradigm shift to a wellbeing economy (Freudenberg, 2023) and help hold private sector actors accountable for their impacts (Valentine et al., 2023). Some papers highlighted the need for HiAP in economic development (Krech, 2011; Loewenson et al., 2022; Hensher, 2023). However, none presented examples of using HIA or other HiAP approaches comprehensively to support a transition to a wellbeing economy in practice.

Specific HiAP methods discussed included HIA (Backholer et al., 2021; Iyer et al., 2021; Freudenberg, 2023), advocacy, partnerships and coalitions (Baum et al., 2023; Porcelli et al., 2023). One paper proposed using systems thinking frameworks to support economic transition for planetary health (Iyer et al., 2021). It discussed the doughnut economy model of wellbeing economy, which includes an inner social foundation, which everyone should achieve, and an outer ecological ceiling of planetary thresholds. The authors suggested using this framework in HIAs to assess multi-level impacts of policies on the elements in the doughnut. These papers were aspirational and few presented examples of applying methods in practice to support a wellbeing economy. Two referred to the programme of corporate HIAs (CHIAs) discussed below (Backholer et al., 2021; Freudenberg, 2023). One discussed partnerships that had successfully influenced policy and outcomes in other sectors but had yet to address economic policy (Porcelli et al., 2023).

Another author critiqued a recent extension of HiAP to become ‘health for all policies’ that seeks ‘win:wins’ for health and other interests to gain support from other sectors (Hensher, 2023). In economic policymaking this could mean, for example stressing that improving health will improve economic productivity. He argued that this framing is counterproductive to the transition to a wellbeing economy in which ‘health is an ultimate goal for economic and social policy, not a tool for improving productivity’. He highlighted that HiAP should support an ideological shift to view the economy as a social provisioning system, rather than a focus on GDP growth favouring overconsumption and commercial determinants (Hensher, 2023).

Examples using HIA to assess commercial determinants

We identified several case studies of HIA being used explicitly to address specific commercial determinants. These were case studies of HIA of TNCs and papers describing HIA of trade and investment agreements.

Seven papers reported on the development and implementation of CHIA. This uses an HIA process and methods to research impacts of the activities of TNCs on health and health equity (Baum and Anaf, 2015). Whereas most HIAs assess a proposed policy or plan in the national or regional context of that plan, CHIA assesses the range of activities of a TNC within and across jurisdictions (Anaf et al., 2022b). As the scoping step of CHIA, the authors held a workshop to develop an analysis framework (Baum et al., 2016). This includes: regulatory structures impacting the TNC; TNC political and business practices and their products, distribution and marketing; and the resulting health and equity impacts. The health impacts include workforce and working conditions, social conditions, natural environment, health related behaviours and economic conditions. The authors have published CHIAs assessing the impacts of McDonald’s in Australia (Anaf et al., 2017), Rio Tinto in Australia and Southern Africa (Anaf et al., 2019) and Carlton and United Breweries in Australia (Anaf et al., 2022a). These used media and documentary analysis, company literature and interviews to identify positive and negative impacts and make recommendations. They also held a citizen’s jury that developed further recommendations based on the McDonald CHIA (Anaf et al., 2018). The authors report that, while they had good engagement from civil society, industry actors refused to participate. However, they found sufficient corporate data and literature for analysis. They also discuss conflicts of interest in corporate and academic collaborations, and potential opposition from corporate interests (Anaf et al., 2022b). Although they made recommendations, these assessments formed a research programme rather than being part of a policymaking process, and their impact on decision-making is unclear.

Another paper proposed using a quantitative HIA approach to measure the health impacts of specific products and services (Singer and Downs, 2024). This would quantify health impacts on consumers through five behaviours—eating, physical activity, sleeping, social engagement and spending time outdoors. They suggested that making these impacts visible will encourage industries to produce healthier products and services. This has a narrower focus than CHIA and does not recognize or address the political and regulatory environment that supports these industries, which ultimately benefit from adopting a lifestyle focus.

Five papers described, or advocated, using HIA to influence international trade and investment policies and agreements. One presented a rapid appraisal HIA approach to assess the overall impacts of trade and investment agreements on global food transformation (Schram and Townsend, 2021). Two reported case study HIAs, of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in Australia (Hirono et al., 2016) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in Wales (Green et al., 2024). A review of strategies to advance health in trade policy found several examples where HIAs influenced national positions in trade negotiations, although most success related to medicines access rather than broader health determinants (Townsend et al., 2021). Similarly, a qualitative study of factors influencing attention to health in the Australian TPP negotiations found that medicines access and tobacco received attention, but other health issues did not (Townsend et al., 2023). Factors influencing this included national export interests, leadership and opportunities for coalitions. The authors highlighted the need for more transparency and suggested that mandatory HIA could help promote health interests. A further challenge highlighted in the CPTPP HIA was the geographical scale of impacts. The HIA was led by Public Health Wales and identified health and inequality impacts for the Welsh population (Green et al., 2024), but international agreements have global impacts and may differentially affect people in low-income countries. These impacts should also be considered to avoid increasing global health inequity.

Challenges and implications for HiAP and HIA

The scoping review identified several potential challenges and implications for HIA to address commercial determinants and progress transition to a wellbeing economy.

Currently, HIAs are more often applied to downstream projects than upstream macroeconomic determinants. One study focused on the health impacts of extractive industry activity in Canada, including HIA (Brisbois et al., 2021). The authors highlighted that HIAs often recognize that indigenous and other populations are vulnerable to adverse impacts because of wider macroeconomic determinants, but do not challenge these wider determinants. They criticized proponent-led HIA as a governance mechanism for acting as ‘tools for project approval’ and failing to challenge corporate power. They reported that HIAs rarely assess macroeconomic policies and argued for a shift in focus to upstream development models and macroeconomic policy at national and international levels (Brisbois et al., 2021).

Methods for international-level HIAs may be more complicated than project-level HIAs. One paper on global governance for health concluded that HiAP at the international level is limited because health ministers represent governments on WHO, preventing broader engagement (Ottersen et al., 2014). It may also need HIA methods that can assess multiple determinants at multiple levels (Buse et al., 2019; Iyer et al., 2021). One paper suggested that the HIA of wealth funds should consider the impacts of the entities they invest in, requiring methods to track these (Lacy-Nichols et al., 2023). A further paper identified a lack of commercial determinants in many conceptual frameworks of health, highlighting the need to identify and frame commercial determinants appropriately (Maani et al., 2020b). This has implications for the determinants considered in HIA.

In HiAP, the usual starting point is a proposed policy or policy area, with holistic consideration of the range of potentially relevant health impacts. One paper reported a case study that took an alternative approach trying to secure a whole of government approach to a specific health issue, obesity (van Eyk et al., 2019). The HiAP team thought that asking other agencies to work on a health priority would be seen as ‘health imperialism’, and to avoid this sought ‘win:win’ solutions by aligning actions to other agencies’ existing priorities. They also used an economic framing by stressing the economic consequences of obesity. They report that this allowed effective engagement but limited actions to those already reflecting the other agencies’ core business that did not challenge commercial interests (van Eyk et al., 2019).

Multiple papers identified conflict between health and economic goals as a challenge to HiAP, given the current priority given to GDP growth in most countries and the power imbalance in favour of corporations (Koivusalo, 2010; Smith et al., 2010; Dora et al., 2013; Koivusalo et al., 2013; Hensher, 2023; Ralston et al., 2023). Authors highlighted that both industry and governments may overestimate short-term economic gains and underestimate longer-term social, environmental and health costs of industrial activities (Dora et al., 2013). They argued for mandatory HIA to ensure that health impacts were recognized and could influence policy and project decisions (Dora et al., 2013; Ottersen et al., 2014).

There may be many powerful opponents to the shifts needed for a wellbeing economy (Hensher, 2023). Several papers discussed ‘corporate capture’ in HiAP including HIA and other impact assessments (Koivusalo, 2010; Smith et al., 2010; Bettcher and Luiza da Costa e Silva, 2013; Koivusalo et al., 2013; World Health Organization, 2015; Ralston et al., 2023). Several included examples from the European Union (EU), where HiAP was interpreted as a mechanism for multi-stakeholder governance, allowing industry stakeholders to influence policymaking (Koivusalo, 2010; Ralston et al., 2023). This reflected existing institutional norms and assumptions about corporate actors within EU institutions (Ralston et al., 2023). One author discussed the challenge of preserving policy space for health in the EU, saying ‘It is not a win‑win if we gain recognition of HiAP, but lose a high level of health protection and health in health policies’ (Koivusalo, 2010). The EU Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health was presented as a HiAP mechanism to achieve healthy weight (Kosinska and Palumbo, 2012). This brought together actors with different interests but raised issues including reputational risk for third-sector partners, resource imbalances and conflicts of interest. The use of impact assessment in the EU was also discussed, as the approach combined economic, social and environmental assessments (Smith et al., 2010). This was strongly influenced by commercial actors, prioritized business interests and delayed or prevented legislation seeking to promote public health or protect the environment. The authors reported that ‘IA does not necessarily facilitate linear, evidence-based policymaking and is rather a tool that can be creatively employed by a variety of interests’. They suggested that impact assessment can be a ‘framing device’ directing attention to some impacts but not others (Smith et al., 2010). This highlights the need for health determinants and health actors to be well represented in impact assessment processes that integrate assessments with different purposes.

Risks arising from industry engagement in HiAP were also identified in the Philippines, where HiAP was conflated with ‘whole of government’ approaches (Lencucha et al., 2015). This included an assumption of collaboration between all sectors including the private sector and a ‘balance’ of public and private interests. This led to industry representation on the national tobacco control body. The authors argued to disentangle actors motived by private profit from economic policy, saying ‘economic development does not necessarily require the uniform support of all private commercial activity, specifically when such activity poses a threat to broader public welfare’ (Lencucha et al., 2015).

Review of HIA frameworks for guidance on managing corporate influence

Of the 24 HIA frameworks previously identified (McDermott et al., 2024), 23 were publicly available in May 2024. They were published between 2001 and 2021. Many were for HIA of either projects or policies, but three were specifically for policies and six for projects, including three for resource extraction projects. Most were for high-income settings, but three were for low-middle-income settings. Two HIA frameworks for resource extraction could also be used in low-middle-income settings. Supplementary Table S2 presents the data extracted from the frameworks.

Our review found that few frameworks acknowledge conflicts between economic and health interests or their implications for HIA practice. Some implicitly recognize that health and economic interests may differ. For example, one noted that HIA was part of a ‘bigger picture including recommendations from other perspectives including economic analysis’ (Ministry of Health, 2007). Another stated that evaluation of projects should consider ‘whether the project has been both a commercial success (made profits) as well as a community success (improved health, wealth, education levels and social relationships in local communities)’ (International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010).

All HIA frameworks recommended stakeholder engagement, without clearly differentiating between corporate and other stakeholders. However, there were differences in the ways stakeholders were considered in frameworks designed for HIA of different kinds of proposals. Frameworks for HIA of industrial development projects, often in low-income settings (International Finance Corporation, 2009; International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010; International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, 2016; Asian Development Bank, 2018) implicitly defined stakeholders as affected communities, separate to the corporate proponent. For example, one described as a function of HIA: ‘Serving as a vehicle to engage companies and key stakeholders in a collaborative decision making process’ (International Finance Corporation, 2009). These frameworks implicitly recognized conflicts between the interests of a corporate proponent and affected communities. However, this conflict usually was not clearly stated and only one of these (Asian Development Bank, 2018) recommended that the HIA team should be independent of the proponent. HIA frameworks that were generic or focused on HIAs of public policy often recommended involving the proponent in the HIA as informants or on the HIA steering group, because they are likely to understand the proposal and alternatives. This may raise conflicts of interest and be less appropriate for HIA of commercial proposals.

Only five frameworks explicitly mentioned conflicts of interest in the conduct of an HIA. Of these, two said the HIA report should acknowledge conflicts of interest, and suggested these should be identified and addressed through a collaboration agreement among the partners (Human Impact Partners, 2011b) or deliberative processes (Bhatia, 2011). Two others recommended considering conflicts of interest when evaluating an HIA (Asian Development Bank, 2018; Pyper et al., 2021). These both noted the potential for the HIA to be influenced by the project proponent, who may have commissioned the HIA. One of these, for HIA of development projects, suggested that the consultant doing the HIA should ideally be independent of both the project owner and the bank to reduce this risk (Asian Development Bank, 2018). Two frameworks noted that stakeholders or informants may also have conflicts of interest (International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010; Pyper et al., 2021). Another highlighted the potential for lobby groups—either for or against a proposal—with ‘strongly held and well-argued views’. This framework highlighted that the HIA team should take account of these views but ‘remain independent and impartial’ (Douglas, 2019).

We also considered whether the frameworks identified power differentials between stakeholder groups. Several frameworks mentioned the potential for conflict or disagreement on the HIA steering group that the chair should manage (Scott-Samuel et al., 2001; Public Health Advisory Committee, 2004; Harris et al., 2007; Chadderton et al., 2012). Participation is a key value in HIA and frameworks commonly recommended community participation in HIA to support community empowerment. Several identified cultural or other barriers that may prevent participation of some communities and gave advice on reducing these barriers (Ministry of Health, 2007; State of Alaska Health Impact Assessment Program, 2011; Chadderton et al., 2012; Douglas, 2019). Four frameworks explicitly recognized that stakeholders may differ in power and influence (International Finance Corporation, 2009; International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010; Human Impact Partners, 2011b; International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, 2016) and two of these recommended including power relationships in a stakeholder analysis (International Finance Corporation, 2009; International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010).

Several frameworks highlighted the need for transparency and some suggested that stakeholder participation would support this (Public Health Advisory Committee, 2004; West Lothian Council, 2017). Frameworks suggested sharing draft reports with the community for comment (State of Alaska Health Impact Assessment Program, 2011), consulting them on mitigation measures (International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010) and involving the community in risk scoring (International Finance Corporation, 2009; International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010). Other suggestions to increase transparency included employing external HIA consultants (International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, 2016) and using external quality assurance reviewers (International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010).

Mapping of HIA checklists to wellbeing economy outcomes

This section presents findings from our mapping of the ‘shared ingredients’ of a wellbeing economy (Zeidler et al., 2023) against the checklists of health determinants provided in selected HIA frameworks (Ministry of Health, 2007; International Council on Mining and Metals, 2010; Bhatia, 2011; Cooke et al., 2011; Chadderton et al., 2012; Douglas, 2019; Pyper et al., 2021). Supplementary Table S3 presents the full mapping and Table 1 presents a summary.

Table 1:

Mapping of wellbeing economy themes and ingredients against HIA checklists

| Wellbeing economy themes and ingredients | Whanua Ora New Zealand 2007 |

International Council on Mining and Minerals 2010 | Cooke Mental Wellbeing IA 2011 |

Bhatia USA 2011 |

Scottish HIA Network 2016 |

Wales HIA Support Unit 2020 | Pyper Ireland 2021 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Local environment | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Housing | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Transport | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Safety | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Proximity to services | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Personal wellbeing | Personal wellbeing | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Loneliness | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Health | Physical health | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Mental health | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Education | Children’s education | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Adult education | √ | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | |

| Economic eecurity | Income/Basic needs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Employment/Jobs | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Local economy | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Community and democracy | Cohesion and belonging | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Connectivity | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Culture | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Community Participation | √ | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | |

| Political voice/Influence | √ | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | ||

| Equity | Disability | √ | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ |

| Gender and sexuality | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | |||

| Social and economic | √ | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | |

| Ethnicity | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Human rights | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | ||

| Environmental sustainability | Energy and emissions | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Waste | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | |||

| Land | √ | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | |

| Water | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | ||

| Nature | √ | √ | √ | √ | V | √ | √ | |

| Air | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

There was a close match between the 30 wellbeing economy ‘shared ingredients’ and the populations and determinants in the seven HIA checklists. Two frameworks included prompts for all 30 ingredients, two had prompts for 29, two covered 27 and one covered 26 ingredients. The environmental sustainability theme was the least well covered as three frameworks missed one or more of these ingredients. One framework only considered two of the six environmental sustainability ingredients but included prompts for all the other ingredients. Most frameworks also included populations and determinants that did not map to any of the wellbeing economy ingredients.

Of the seven frameworks, six included factors such as diet and substance use under the headings ‘lifestyle’ or ‘health-related behaviours’. This suggests that the framing of these health determinants in the checklists could be improved, to prompt greater consideration of the commercial and other factors that drive consumption.

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

Our scoping review found that several authors have identified links between the concepts of HiAP and wellbeing economy. HiAP approaches, including HIA, could potentially encourage a holistic approach to policymaking, make externalities explicit and create a policy environment that supports health and equity. Case examples exist using HIA to understand and address commercial determinants, including trade policy. However, aspirations for systematic use of HiAP approaches to support transition to a wellbeing economy have not (yet) been realised in practice. Challenges include conflict between health and economic goals, power imbalance between corporate and other interests, corporate capture and risks of industry involvement as stakeholders and the need for more focus on upstream macroeconomic policies. Our review of HIA frameworks found little recognition of corporate interests or power differences between stakeholders and little guidance on managing conflicts of interest. There is congruence between wellbeing economy ‘shared ingredients’ and the health determinants considered in selected HIA frameworks. This suggests that HIA could be a practical way to scrutinize and assess whether economic and other policies are supporting the transition to a wellbeing economy. However, other actions are needed to address power imbalances and the perceived imperative of economic growth.

Comparison with other literature

A previous scoping review of mechanisms for addressing corporate influence in public health policy research and practice focused on managing the influence of specific health-harming industries (Mialon et al., 2020). It identified 49 mechanisms, including policies on conflicts of interest and engagement, disclosure and codes of conduct. It did not discuss HIA or HiAP but the mechanisms could help identify and address corporate influence in HIA practice. A ‘public health playbook’ identifies ways to counteract commercial influences that are damaging to health (Lacy-Nichols et al., 2022). These include training, coalitions and developing conflict of interest safeguards, which would also strengthen HIA practice. Other authors have discussed public health roles in addressing commercial determinants, which include reducing exposure to harmful practices, market regulation, fiscal policies, citizen or consumer activism and litigation (Lee and Freudenberg, 2022). They argue for greater policy coherence and an integrated approach that does not address individual industries in isolation but addresses the social structures that maintain them. This chimes with the papers in our review that expressed an aspiration for HiAP to support this change.

The scoping review also corroborates suggestions that both wellbeing economy and HiAP are concepts that can be misunderstood or misused (Green et al., 2021; McCartney et al., 2022; McCartney et al., 2023; Hensher et al., 2024). Wellbeing economy could become a ‘glittering generality’ that policy and commercial actors claim to support while still prioritizing corporate interests and presenting the economy as an end in itself, rather than a means to improve human and planetary wellbeing (McCartney et al., 2023). Scrutiny and assessment may help ensure that plans and policies genuinely support the transition to wellbeing economy and improve health and equity, rather than preserving the status quo. However, alongside evidence, assessment and scrutiny, a change in mindset is also needed, to shift the focus from economic development and GDP growth (Hensher et al., 2024; Trebeck, 2024). Similarly, our review found that in some cases the concept of HiAP was conflated with multi-stakeholderism (Koivusalo, 2010; Lencucha et al., 2015; Ralston et al., 2023). This enabled powerful corporate actors to gain involvement in setting policies and regulations that affected their interests. Other research has highlighted the risks of corporate involvement in health policy and health partnerships. These include the involvement of industry actors in community alcohol partnerships (Petticrew et al., 2018), public health responsibility deals (Knai et al., 2015) and pharmaceutical regulatory agencies (Mindell et al., 2012). There is a need to reaffirm the definition and purpose of HiAP and adopt mechanisms to avoid corporate capture.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this work include the systematic search and breadth of papers in the scoping review, including grey literature. The mapping and review of frameworks used systematic processes with authors independently checking the findings. However, there are limitations. Our scoping review was completed rapidly using non-independent double screening of papers, and our protocol was published after the screening and selection of papers had begun, although before they were completed. Our search did not find HIAs of policies relating to unhealthy commodities such as tobacco or alcohol policies, although examples exist. This may be because we sought papers that discussed implications of commercial determinants and corporate actors and these HIAs may not explicitly have recognized or discussed these influences. However further work would be needed to confirm this. A further limitation is that our mapping of determinants listed in HIA frameworks against wellbeing economy outcomes only mapped seven HIA frameworks. We purposively selected frameworks with a comprehensive checklist or table of health determinants. This means that the mapping does not represent all HIA frameworks but does show the potential for HIA to support wellbeing economy outcomes.

Implications for HIA practice

Our findings raise the question of how to manage the involvement of corporate stakeholders in project, plan and policy-level HIAs. Participation is a key principle underpinning HIA (Winkler et al., 2021). Commercial actors may offer a legitimate perspective and useful insights, and range from small businesses to large TNCs. It would be inappropriate to exclude them all from any involvement in HIA, but management of conflicts of interest and power differences between stakeholder groups must be strengthened.

Both the scoping review of literature and the review of HIA frameworks highlighted that ‘stakeholder’ can be used in different ways. In different contexts, it may imply the involvement of powerful corporate actors or less powerful affected populations, or these may be conflated, obscuring their differences. The term ‘stakeholder’ has been criticized for this ambiguity and for perpetuating colonial narratives (Reed et al., 2024). Rather than using stakeholder as an all-encompassing term, HIA practitioners should clearly identify groups with different interests. As the scoping review highlighted, just aiming for ‘balance’ of views is inappropriate because the profit motive differentiates corporate interest from other groups (Lencucha et al., 2015; World Health Organization, 2015; Backholer et al., 2021). HIA teams must consider these issues when defining the groups involved and mechanisms of involvement and set appropriate boundaries to avoid influence from powerful commercial interests. HIA frameworks must provide better guidance about this. This should include how to recognize, report and prevent conflicts of interest in the HIA process. Transparency alone is not sufficient to avoid conflict of interest influencing results (Goldberg, 2018; Lexchin and Fugh-Berman, 2021). This suggests that the HIA steering group should by default exclude corporate representatives, especially from health-harming commodities.

HIA guidance could also more explicitly identify commercial determinants in framing health and wellbeing determinants during HIA screening and scoping. The authors are involved in revising two of the HIA frameworks presented here (Chadderton et al., 2012; Douglas, 2019). In one of these, as a result of this review, we are adding prompts to the checklist for: Wealth circulation and community benefits; Ownership of assets and Commercial practices and marketing. The other will prompt consideration of specific health-harming commodities, macroeconomic determinants and commercial influence. Other revisions will reinforce the need to recognize and address conflicts of interest and imbalance of power between groups.

It is unsurprising that the determinants considered in HIA closely match the outcomes defined in wellbeing economy frameworks, as both adopt a holistic understanding of wellbeing. HIA offers a way to consider these elements systematically and promote better outcomes across the range of potential unintended impacts that a policy may create. However, other actions are needed to redress power imbalances and challenge the primacy of economic growth. HIA also needs to be used more routinely, using evidence critically to enable meaningful changes to policy and avoid depoliticizing and decontextualizing health and wellbeing impacts. The review highlighted the need for more HIAs of upstream policies, especially economic policies. Governance of international HIAs may need to be negotiated to allow them to influence relevant international policies, rules and regulations while protecting the interests of low-income countries and populations with lower levels of power and influence (Koivusalo et al., 2013; Ottersen et al., 2014).

Future research

Further research should aim to understand whether and how HIA practitioners recognize and address corporate interests in their practice. This should investigate how HIAs have managed corporate interests and conflict between stakeholders, and the implications for their assessment findings and recommendations, especially for promoting equity. This should study HIAs of different kinds of projects, plans and policies at different levels, including those directly relating to UCIs.

Comparative research of proponent-led and other models of HIA governance would help to understand whether the governance of an HIA affects the involvement of other stakeholders, whether and how conflicts of interest are recognized and addressed, the impacts identified and the recommendations made.

An exploration of practitioners’ and policymakers’ views should identify barriers and facilitators to greater use of HIA and other HiAP approaches for economic and related policies. This could inform future HiAP and HIA practices to influence the regulatory environment that sustains corporate power and commercial determinants.

Research on processes that sustain and reinforce different forms of power related to economic status, social class and other characteristics, and on ways to challenge these, is needed to inform the ideational change needed for the transition to a wellbeing economy.

CONCLUSION

Addressing commercial determinants should involve changing the norms, assumptions and regulatory context that reinforce corporate power in ways that harm health. This means supporting a wellbeing economy which prioritizes health and equity instead of GDP growth and corporate interests. There is a strong synergy between the concepts of wellbeing economy and HiAP, and HIA could be a useful mechanism to support change, particularly if applied to economic and related policies. Creating this transition requires not just mechanisms like HIA but an ideational change to shift the primacy of GDP growth (Trebeck, 2024). HIA practitioners also need guidance on how to recognize and address corporate power and conflicts of interest. Perhaps the biggest challenge is to enable HIAs to be used meaningfully and more routinely as ‘part of comprehensive whole of government and whole of society networks and systems that promote wellbeing, equity and health at all levels’ (Valentine et al., 2023).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Margaret J Douglas, Public Health Scotland, Economy and Poverty Programme, Gyle Square, 1 South Gyle Crescent, Edinburgh EH12 9EB, UK; School of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, 90 Byres Road, Glasgow G12 8TB, UK; Department of International Health, Care and Public Health Research Institute—CAPHRI, Maastricht University, Universiteitssingel 40, 6229 ER Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Catherine Foster, Public Health Scotland, Economy and Poverty Programme, Gyle Square, 1 South Gyle Crescent, Edinburgh EH12 9EB, UK.

Rosalind McDermott, Public Health Department, Southwark Council, 160 Tooley Street, London SE1 2QH, UK.

Lukas Bunse, WEAll Scotland, Princes House, 51 West Campbell Street, Glasgow G2 6SE, UK.

Timo Clemens, Department of International Health, Care and Public Health Research Institute—CAPHRI, Maastricht University, Universiteitssingel 40, 6229 ER Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Jodie Walker, Public Health Scotland, Economy and Poverty Programme, Gyle Square, 1 South Gyle Crescent, Edinburgh EH12 9EB, UK.

Liz Green, Policy and International Health Directorate, WHO Collaborating Centre on ‘Investment in Health and Well-being’, Public Health Wales, Number 2 Capital Quarter, Tyndall Street, Cardiff CF10 4BZ, UK.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.D. and L.G. conceived the article and discussed initial ideas. M.D. developed the scoping review protocol with input from J.W., L.G., T.C. and C.F. J.W. designed the scoping review search strategy and performed the searches. M.D. and C.F. performed screening and selection of papers for the scoping review. M.D. and R.M. reviewed HIA frameworks. M.D., L.G. and L.B. mapped wellbeing economy ingredients against health determinants. M.D. drafted the initial manuscript and all authors provided critical input and approved the final draft.

FUNDING

This work did not receive any specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

M.D. and L.G. have been involved in developing two of the HIA frameworks reviewed in this article. We have no other interests to declare.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data underlying this article are available in the online supplementary material.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This work used only published evidence and did not require ethical approval.

REFERENCES

- Anaf, J., Baum, F. and Fisher, M. (2018) A citizens’ jury on regulation of McDonald’s products and operations in Australia in response to a corporate health impact assessment. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42, 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaf, J., Baum, F., Fisher, M., Haigh, F., Miller, E., Gesesew, H.. et al. (2022a) Assessing the health impacts of transnational corporations: a case study of Carlton and United Breweries in Australia. Globalization and Health, 18, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaf, J., Baum, F. E., Fisher, M., Harris, E. and Friel, S. (2017) Assessing the health impact of transnational corporations: a case study on McDonald’s Australia. Globalization and Health, 13, 4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaf, J., Baum, F., Fisher, M. and London, L. (2019) The health impacts of extractive industry transnational corporations: a study of Rio Tinto in Australia and Southern Africa. Globalization and Health, 15, 13–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaf, J., Fisher, M. and Baum, F. (2022b) Using critical theory to research commercial determinants of health: health impact assessment of the practices and products of transnational corporations. In Potvin, L. and Jourdan, D. (eds), Global Handbook of Health Promotion Research, Vol. 1: Mapping Health Promotion Research. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 497–511. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank. (2018) Health Impact Assessment: A Good Practice Sourcebook. Asian Development Bank, Manila. https://www.adb.org/documents/health-impact-assessment-sourcebook (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Backholer, K., Baum, F., Finlay, S. M., Friel, S., Giles-Corti, B., Jones, A.. et al. (2021) Australia in 2030: what is our path to health for all? The Medical Journal of Australia, 214, S5–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, P., McKee, M., Basu, S. and Stuckler, D. (2017) The health impact of trade and investment agreements: a quantitative systematic review and network co-citation analysis. Globalization and Health, 13, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, F., Friel, S., Liberman, J., de Leeuw, E., Smith, J. A., Herriot, M.. et al. (2023) Why action on the commercial determinants of health is vital. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 34, 725–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, F. E. and Anaf, J. M. (2015) Transnational corporations and health: a research agenda. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 45, 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, F. E., Sanders, D. M., Fisher, M., Anaf, J., Freudenberg, N., Friel, S.. et al. (2016) Assessing the health impact of transnational corporations: its importance and a framework. Globalization and Health, 12, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettcher, D. and Luiza da Costa e Silva, V. (2013) Tobacco or health. In Leppo, K., Ollila, E. and Cook, S. (eds), Health in All Policies: Seizing Opportunities, Implementing Policies. WHO European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels, pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, R. (2011) Health Impact Assessment: A Guide for Practice. Human Impact Partners, Oakland, CA. https://humanimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/HIA-Guide-for-Practice.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Brisbois, B., Hoogeveen, D., Allison, S., Cole, D., Fyfe, T. M., Harder, H. G.. et al. (2021) Storylines of research on resource extraction and health in Canada: a modified metanarrative synthesis. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 277, 113899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, R. C., Nyhan, K., Dharia, N., Freudenberg, N. and Ransome, Y. (2024) Characteristics of commercial determinants of health research on corporate activities: a scoping review. PLoS One, 19, e0300699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse, C. G., Lai, V., Cornish, K. and Parkes, M. W. (2019) Towards environmental health equity in health impact assessment: innovations and opportunities. International Journal of Public Health, 64, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadderton, C., Elliott, E., Green, L., Lester, J. and Williams, G. (2012) Health Impact Assessment a Practical Guide. Public Health Wales, Cardiff. https://phwwhocc.co.uk/whiasu/resources/?category=78 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Cincinnati Health Department Health Impact Assessment Committee. (2011) Health Impact Assessment of the Layoff and Bumping Process. Community Commons, Cincinnati. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/ddd573d4-2ae4-4035-8007-03e36f126a75 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J., Sheward, R., Showers, B. and Ochoa, E. (2019) Health Impact Assessment of Creating a State-Level Refundable Earned Income Tax Credit in Arkansas. Community Commons. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/765c4e77-c339-4467-94e6-c5011d4df6c7 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, A., Friedli, L., Coggins, T., Edmonds, N., Michaelson, J., O’Hara, K., et al. (2011) Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment: A Toolkit for Wellbeing. National MWIA Collaborative, London. https://healthycampuses.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/MentalWellbeingImpactAssessmentAtoolkitforwellbe-1.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A., Cortes, M., Sena, C., Nunes, E., Nogueira, P. and Shivaji, T. (2018) Equity-focused health impact assessment of Portuguese tobacco control legislation. Health Promotion International, 33, 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cylus, J. and Smith, P. C. (2020) The economy of wellbeing: what is it and what are the implications for health? British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 369, m1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K., Morris-Compton, S., Chandran, A., Barbot, O., Castillo-Salgrado, C., Pollack, K., et al. (2013) Health Impact Assessment of the Lexington Market Revitalization Initiative. Community Commons. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/58145071-4373-4b41-b77b-e02d1e075158 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- de Lacy-Vawdon, C. and Livingstone, C. (2020) Defining the commercial determinants of health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 20, 1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dora, C., Pfeiffer, M. and Racioppi, F. (2013) Lessons for environment and health for HiAP. In Leppo, K., Olillo, E., Pena, S., Wismar, M. and Cook, S. (eds), Health in All Policies: Seizing Opportunities, Implementing Policies. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, WHO European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Finland, pp. 255–286. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. (2019) Health Impact Assessment Guidance for Practitioners. Scottish Public Health Network, Edinburgh. https://www.scotphn.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Health-Impact-Assessment-Guidance-for-Practitioners-SHIIAN-updated-2022.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M., Walker, J., Foster, C., Clemens, T. and Green, L. (2024) Implications of commercial determinants for Health Impact Assessment and Health in All Policies: a scoping review protocol. https://doi.org/ 10.6084/m9.figshare.25897030.v3 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. J., Watkins, S. J., Gorman, D. R. and Higgins, M. (2011) Are cars the new tobacco? Journal of Public Health, 33, 160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feteira-Santos, R., Alarcão, V., Santos, O., Virgolino, A., Fernandes, J., Vieira, C. P.. et al. (2021) Looking ahead: Health Impact Assessment of Front-Of-Pack Nutrition Labelling Schema as a public health measure. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J., Mustard, C., Smith, P., Siddiqi, A., Cheng, Y., Burdorf, A.. et al. (2023) Work as a social determinant of health in high-income countries: past, present, and future. Lancet (London, England), 402, 1357–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg, N. (2023) Framing commercial determinants of health: an assessment of potential for guiding more effective responses to the public health crises of the 21(st) century. The Milbank Quarterly, 101, 83–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel, S. (2023) Climate change mitigation: tackling the commercial determinants of planetary health inequity. The Lancet, 402, 2269–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel, S., Collin, J., Daube, M., Depoux, A., Freudenberg, N., Gilmore, A. B.. et al. (2023) Commercial determinants of health: future directions. Lancet (London, England), 401, 1229–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes, E., Marcon, A., Potts, L., Pesce, G., Lhachimi, S. K., Jani, V.. et al. (2021) Health impact assessment to predict the impact of tobacco price increases on COPD burden in Italy, England and Sweden. Scientific Reports, 11, 2311–2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, A. B., Fabbri, A., Baum, F., Bertscher, A., Bondy, K., Chang, H.. et al. (2023) Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. Lancet (London, England), 401, 1194–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D. S. (2018) The shadows of sunlight: why disclosure should not be a priority in addressing conflicts of interest. Public Health Ethics, 12, 202–212. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L., Ashton, K., Bellis, M. A., Clemens, T. and Douglas, M. (2021) ‘Health in All Policies’—a key driver for health and well-being in a post-COVID-19 pandemic world. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, L., Ashton, K., Silva, L., McNamara, C., Fletcher, M., Petchey, L.. et al. (2024) Assessing public health implications of free trade agreements: the comprehensive and progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. Global Policy, 15, 676–688. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P., Harris-Roxas, B., Harris, E. and Kemp, L. (2007) Health Impact Assessment: A Practical Guide. University of New South Wales, Sydney. https://hiaconnect.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Health_Impact_Assessment_A_Practical_Guide.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Health Promotion Agency. (2013) Guidelines for Conducting a Health Impact Assessment for Local Alcohol Planning. Health Promotion Agency, Wellington, New Zealand. https://resources.alcohol.org.nz/assets/Uploads/Health_Impact_Assessment_Guidelines_FA03_LR.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, M. (2023) The economics of the wellbeing economy: understanding heterodox economics for health-in-all-policies and co-benefits. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 34, 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, M., McCartney, G. and Ochodo, E. (2024) Health economics in a world of uneconomic growth. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 22, 427–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirono, K., Haigh, F., Gleeson, D., Harris, P., Thow, A. M. and Friel, S. (2016) Is health impact assessment useful in the context of trade negotiations? A case study of the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement. BMJ Open, 6, e010339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Impact Partners. (2011a) A Health Impact Assessment of Paid Sick Days Policies in New Jersey summary of findings. Community Commons. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/8681a4f1-7091-4ee3-ae9d-3aac03207658 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Human Impact Partners. (2011b) A Health Impact Assessment Toolkit: A Handbook to Conducting HIA, 3rd edition, Human Impact Partners, Oakland, CA. https://humanimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/A-HIA-Toolkit_February-2011_Rev.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Oil & Gas Producers. (2016) Health Impact Assessment: A Guide for the Oil and Gas Industry. International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, London. https://www.iogp.org/bookstore/product/health-impact-assessment-a-guide-for-the-oil-and-gas-industry/ (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Mining and Metals. (2010) Good Practice Guidance on Health Impact Assessment. International Council on Mining and Metals. https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/health-and-safety/2010/guidance_health-impact-assessment.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation. (2009) Introduction to Health Impact Assessment. https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2000/publications-handbook-healthimpactassessment--wci--1319578475704 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, H. S., DeVille, N. V., Stoddard, O., Cole, J., Myers, S. S., Li, H.. et al. (2021) Sustaining planetary health through systems thinking: public health’s critical role. SSM - Population Health, 15, 100844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knai, C., Petticrew, M., Durand, M. A., Eastmure, E. and Mays, N. (2015) Are the public health responsibility deal alcohol pledges likely to improve public health? An evidence synthesis. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 110, 1232–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivusalo, M. (2010) The state of Health in All policies (HiAP) in the European Union: potential and pitfalls. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 64, 500–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivusalo, M., Labonte, R., Wibulpolprasert, S. and Kanchanachitra, C. (2013) Globalisation and national policy space for health and a HiAP approach. In Leppo, K., Ollila, E. and Cook, S. (eds), Health in All Policies: Seizing Opportunities, Implementing Policies. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, WHO European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Finland, pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kosinska, M. and Palumbo, L. (2012) Industry engagement. In McQueen, D., Wismar, M., Lin, V., Jones, C. M. and Maggie, D. (eds), Intersectoral Governance for Health in All Policies: Structures, Actions and Experiences. WHO European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Copenhagen, Denmark, pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Krech, R. (2011) Healthy public policies: looking ahead. Health Promotion International, 26, ii268–ii272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, G., Singer, B., Winkler, M., Divall, M., Tanner, M. and Utzinger, J. (2013) Health impact assessment in developing countries. In Kemm, J. (ed), Health Impact Assessment Past Achievement, Current Understanding, and Future Progress. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Labonté, R. (2019) Trade, investment and public health: compiling the evidence, assembling the arguments. Globalization and Health, 15, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy-Nichols, J., Marten, R., Crosbie, E. and Moodie, R. (2022) The public health playbook: ideas for challenging the corporate playbook. The Lancet Global Health, 10, e1067–e1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy-Nichols, J., Nandi, S., Mialon, M., McCambridge, J., Lee, K., Jones, A.. et al. (2023) Conceptualising commercial entities in public health: beyond unhealthy commodities and transnational corporations. Lancet (London, England), 401, 1214–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. and Freudenberg, N. (2022) Public health roles in addressing commercial determinants of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 43, 375–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencucha, R., Drope, J. and Chavez, J. J. (2015) Whole-of-government approaches to NCDs: the case of the Philippines Interagency Committee-Tobacco. Health Policy and Planning, 30, 844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexchin, J. and Fugh-Berman, A. (2021) A ray of sunshine: transparency in physician-industry relationships is not enough. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36, 3194–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenson, R., Godt, S. and Chanda-Kapata, P. (2022) Asserting public health interest in acting on commercial determinants of health in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from a discourse analysis. BMJ Global Health, 7, e009271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott, M., Miller, L., Arm, K. and Story, M. (2020) Rapid Health Impact Assessment on USDA Proposed Changes to School Nutrition Standards. Healthy Eating Research, Durham, NC. https://healthyeatingresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/her-hia-report-final-1.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Maani, N., Abdalla, S. M. and Galea, S. (2020a) The firearm industry as a commercial determinant of health. American Journal of Public Health, 110, 1182–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maani, N., Collin, J., Friel, S., Gilmore, A. B., McCambridge, J., Robertson, L.. et al. (2020b) Bringing the commercial determinants of health out of the shadows: a review of how the commercial determinants are represented in conceptual frameworks. European Journal of Public Health, 30, 660–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maani, N., van Schalkwyk, M. C., Petticrew, M. and Buse, K. (2022) The pollution of health discourse and the need for effective counter-framing. British Medical Journal, 377, o1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maani, N., Van Schalkwyk, M. C. I., Petticrew, M. and Galea, S. (2021) The commercial determinants of three contemporary national crises: how corporate practices intersect with the COVID-19 pandemic, economic downturn, and racial inequity. The Milbank Quarterly, 99, 503–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathon County Health Department. (2011) Health Impact Assessment Report Alcohol Environment—Village of Weston, WI. Community Commons. https://hia.communitycommons.org/cc_resource/health-impact-assessment-report-alcohol-environment-village-of-weston-wi/ (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, G. (2022) Putting economic policy in service of ‘health for all’. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 377, o1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, G., Hensher, M. and Trebeck, K. (2023) How to measure progress towards a wellbeing economy: distinguishing genuine advances from ‘window dressing’. Public Health Research & Practice, 33, 3322309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, G., McMaster, R., Shipton, D., Harding, O. and Hearty, W. (2022) Glossary: economics and health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 76, 518–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, R., Douglas, M. J., Haigh, F., Takemon, N. and Green, L. (2024) A systematic review of whether health impact assessment frameworks support best practice principles. Public Health, 233, 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mialon, M. (2020) An overview of the commercial determinants of health. Globalization and Health, 16, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mialon, M., Vandevijvere, S., Carriedo-Lutzenkirchen, A., Bero, L., Gomes, F., Petticrew, M.. et al. (2020) Mechanisms for addressing and managing the influence of corporations on public health policy, research and practice: a scoping review. BMJ Open, 10, e034082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar, J. S. (2013) The corporate determinants of health: how big business affects our health, and the need for government action! Canadian Journal of Public Health, 104, e327–e329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell, J. S., Reynolds, L., Cohen, D. L. and McKee, M. (2012) All in this together: the corporate capture of public health. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 345, e8082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. (2007) Whānau Ora Health Impact Assessment. Ministry of Health, Wellington. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/whanau-ora-health-impact-assessment-2007 (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Mongru, R., Omnes, S., Wilson, H. and Shivaji, T. (2017) Health Impact Assessment of the Aberdeen City Licensing Board Statement of Licensing Policy. Aberdeen City Council, Aberdeen. https://committees.aberdeencity.gov.uk/documents/s78921/HIA%20Statement%20of%20Licensing%20Policy%20report.pdf (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Montachusett Regional Planning Commission. (2013) Fitchburg Health Impact Assessment. Community Commons. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/6b289110-3dd5-46bd-8ff8-58c461d8585f (last accessed 15 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A. and Aromataris, E. (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottersen, O. P., Dasgupta, J., Blouin, C., Buss, P., Chongsuvivatwong, V., Frenk, J.. et al. (2014) The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. Lancet (London, England), 383, 630–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D.. et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 372, n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C. and Khalil, H. (2020) Scoping reviews. In Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B. and Jordan, Z. (eds), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. 10.46658/JBIMES-24-09(last accessed 1 October 2024). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M., Douglas, N., D’Souza, P., Shi, Y. M., Durand, M. A., Knai, C.. et al. (2018) Community alcohol partnerships with the alcohol industry: what is their purpose and are they effective in reducing alcohol harms? Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 40, 16–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli, A., D’Onise, K. and Pontifex, K. (2023) Public health partner authorities—How a health in all policies approach could support the development of a wellbeing economy. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 34, 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]