Abstract

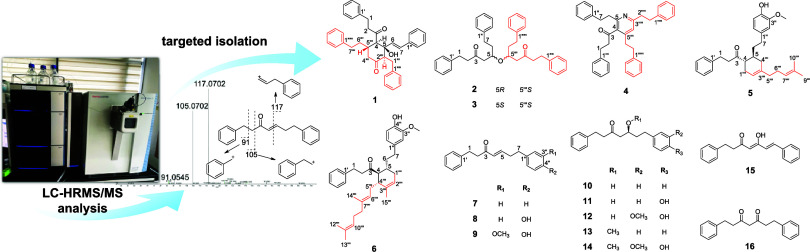

LC-HRMS/MS analysis facilitated the precise targeting, isolation, and identification of unusual dimeric diarylheptanoids from Alpinia officinarum (A. officinarum). The tandem MS data for (4E)-1,7-diphenyl-4-hepten-3-one (7) revealed fragment ions at m/z 91, 105, and 117, which are fragmentation patterns specific to diarylheptanoids. In the tandem MS data, peaks with m/z values ranging from 450 to 600 that exhibited these specific fragment ions were selected and isolated. Consequently, two previously undescribed dimeric diarylheptanoids (1 and 2) and four unusual diarylheptanoids (3–6) along with 10 monomeric diarylheptanoids (7–16) were isolated from the rhizomes of A. officinarum using various chromatographic techniques. The structures of the isolates were elucidated by an analysis of 1D/2D NMR and HRESIMS data, and a combination of DP4+ probability analysis and ECD calculations. To evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects of the isolated compounds, their inhibitory activity against nitric oxide production in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells was assessed. Compounds 1, 7, and 9 exhibited remarkable inhibitory effects with IC50 values of 14.7, 6.6, and 5.0 μM, respectively.

Introduction

Alpinia officinarum Hance, commonly known as lesser galangal, is a perennial herb of the Zingiberaceae family, native to Southeast and East Asia. The rhizomes of this plant have been traditionally used to treat various ailments, including rheumatism, bronchial catarrh, diabetes, and blood coagulation disorders. Phytochemical investigations of A. officinarum have identified a range of bioactive compounds, including diarylheptanoids, flavonoids, and diterpenoids, which contribute to its medicinal properties.1,2 Diarylheptanoids are a unique class of natural compounds characterized by a 1,7-diphenylheptane structure.

The C7 chain of diarylheptanoids contains a range of reactive functionalities, including double bonds, hydroxyl groups, and carbonyl groups, which can participate in various processes, such as intramolecular cyclization, polymerization, coupling with many functional groups, and hybridization, leading to substantial structural diversity.3 Diarylheptanoids are of particular interest in drug research and development owing to their diverse and significant biological effects, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective activities.4−8

The advancement of various spectroscopic techniques such as LC-MS/MS, NMR, and ECD, has markedly facilitated the development of pharmaceutical materials from natural products. In particular, LC-HRMS/MS analysis has proven to be an excellent too for dereplication. Tandem MS (MS/MS) involves multiple stages of mass spectrometry, whereby molecules are first ionized, and then selected precursor ions are fragmented to produce fragment ions. By analyzing the resultant fragmentation pattern and neutral losses, valuable structural information can be obtained, enabling the precise identification and characterization of compounds. Neutral loss analysis identifies common losses among related molecules, thereby enhancing molecular similarity analysis and facilitating the discovery of structurally related analogs.9−11 In this study, LC-HRMS/MS spectral data were interpreted by analyzing tandem MS fragment ion patterns and neutral losses, to specifically target, isolate, and identify unusual diarylheptanoids from the rhizomes of A. officinarum.

Results and Discussion

In the untargeted MS data obtained from the MeOH extract of A. officinarum, the major peak with an m/z value of 265.1586 was initially presumed to be a diarylheptanoid, based on the literature search. This major peak was subsequently identified as a diarylheptanoid, (4E)-1,7-diphenyl-4-hepten-3-one (7) ([M + H]+, 265.1586), which was chromatographically isolated. Its structure was confirmed by comparing the obtained 1D NMR data with previously reported values.13 The MS2 fragmentation spectral data for 7 revealed neutral losses at m/z 91, 105, and 117, which are the fragmentation patterns specific to diarylheptanoids (Figure 1).14

Figure 1.

UHPLC-MS/MS data and fragmentation pattern of C19H21O (m/z = 265.1586).

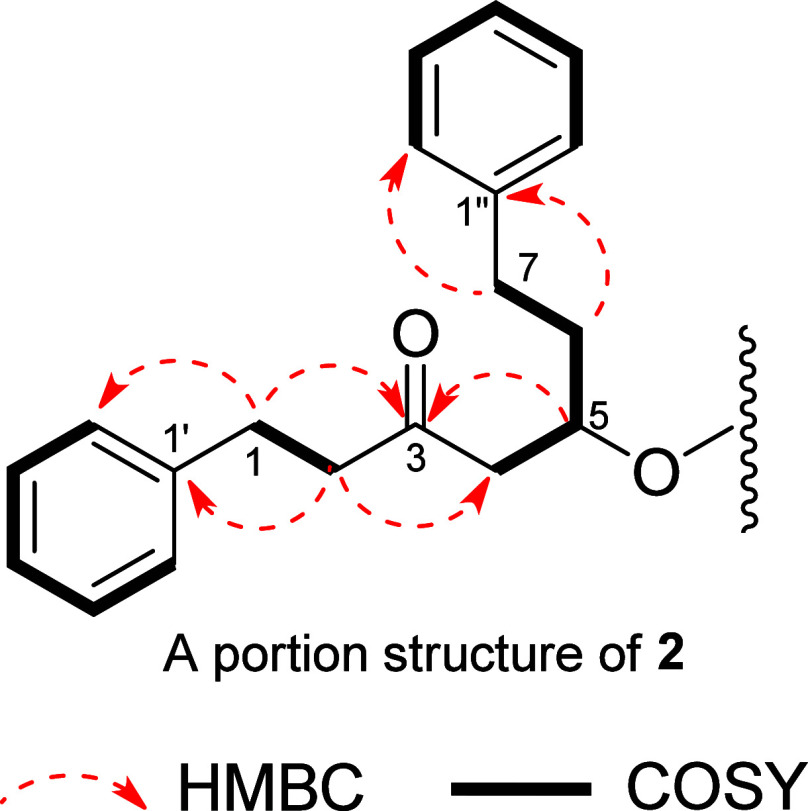

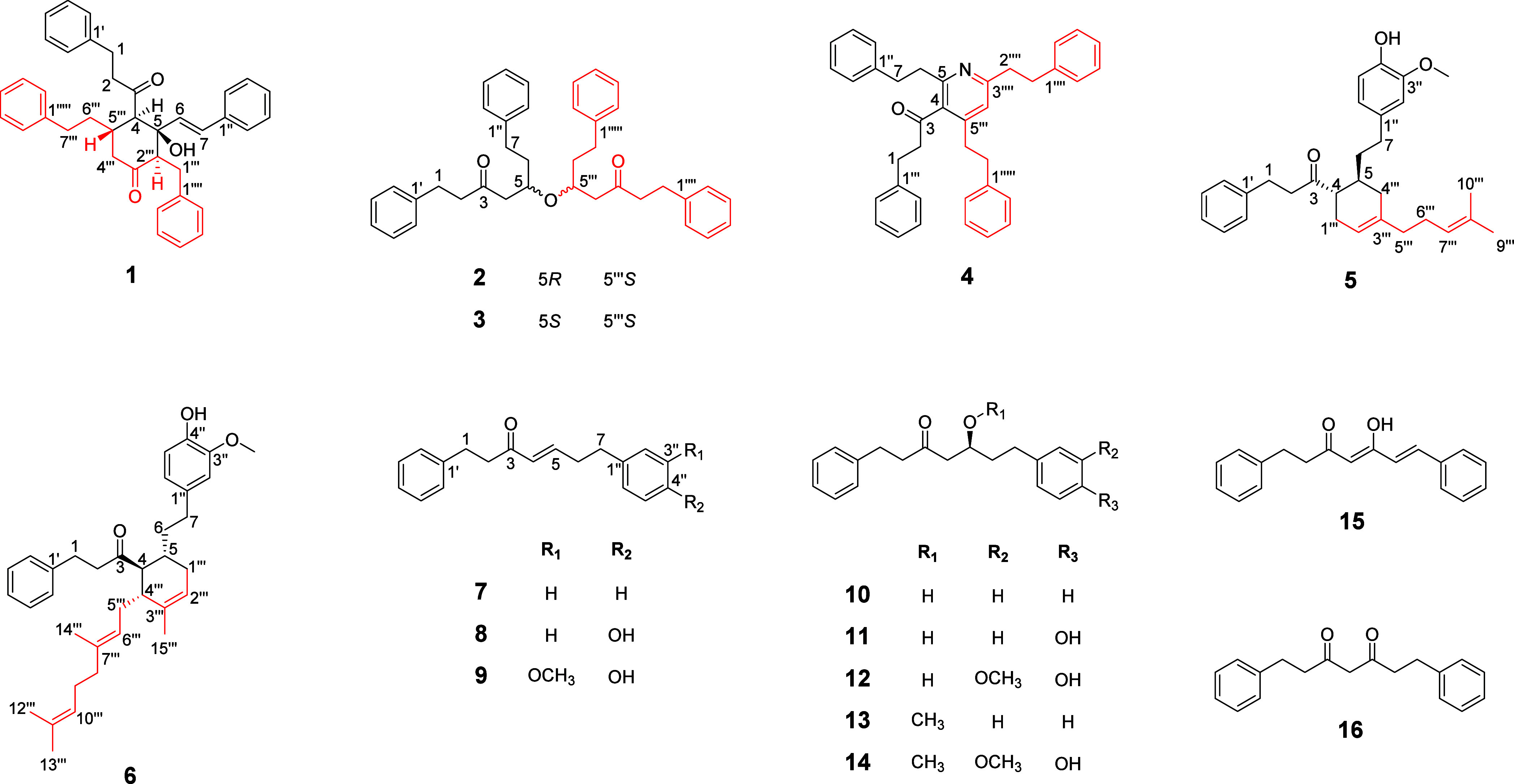

To target and isolate unusual dimeric diarylheptanoids, the MS2 fragmentations of peaks appearing in the m/z range of 450–600 were analyzed, and those showing the diarylheptanoid fragmentation pattern were selected for isolation. Consequently, two previously undescribed diarylheptanoid dimers (1-2), four unusual diarylheptanoids (3-6), and ten diarylheptanoid analogues (7-16) were isolated and identified (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Structures of isolated compounds 1–16.

Alpiniofficinoid A (1) was obtained as a yellow oil and its molecular formula was determined to be C38H38O3 based on the HRESIMS data, which indicated an m/z of 565.2713 [M + Na]+ (Calcd for C38H38O3Na, m/z 565.27132). The IR spectrum showed the presence of hydroxyl (3389 cm–1), carbonyl (1714 and 1650 cm–1), and aromatic ring (1495 cm–1) functional groups in 1. The 1H and 13C NMR data revealed the presence of two ketone carbonyls (δC 215.5, 205.9), four monosubstituted benzene rings [δH 6.84 (2H, m), 7.05 (2H, m), 7.07–7.08 (3H, overlapped), 7.09–7.11 (3H, overlapped), 7.16–7.19 (3H, overlapped), 7.27 (2H, m), 7.31–7.32 (2H, m), and 7.33–7.35 (3H, overlapped); δC 142.0, 140.9, 140.2, 135.7, 129.1 × 2, 128.8 × 2, 128.6 × 2, 128.4 × 2, 128.25 × 2, 128.19 × 2, 128.1 × 2, 126.6 × 3, 126.2, 126.1, and 125.7], a trans-disubstituted olefinic bond [δH 6.60 (1H, d, J = 15.8 Hz) and 6.12 (1H, d, J = 15.8 Hz); δC 131.3 and 131.0], three methines [δH 3.09 (1H, d, J = 11.3 Hz), 2.69 (1H, m), and 2.61 (1H, m); δC 62.1, 60.4, and 37.7], an oxygenated quaternary carbon (δC 79.9), and six methylene groups (Table 1). Eight spin-coupling systems were established based on the correlations observed in the 1H–1H COSY spectrum of 1 (Figure 3). Moreover, the HMBC correlations between H2-1 and C-3, C-2′/6′; H2-2 and C-3, C-4, C-1′; H-6 and C-4, C-1″; and between H-7 and C-5, C-2″/6″ led to the construction of the diarylheptanoid moiety, 5-hydroxy-1,7-diphenyl-6-hepten-3-one (1a). Additionally, the presence of a second diarylheptanoid portion, 1,7-diphenyl-3-heptanone (1b), was revealed by the HMBC correlations between H2-1‴ and C-5, C-3‴, C-2‴′/6‴′; H-2‴ and C-4‴, C-1‴′; H2-6‴ and C-4‴, C-1‴‴; and H2-7‴ and C-5‴, C-2‴‴/6‴‴. The two diarylheptanoid monomers 1a and 1b were bridged via two C–C single bonds between C-4/C-5‴ and C-5/C-2‴ to form a six-membered ring system, as established based on the COSY correlation between H-4 and H-5‴, and the HMBC correlations between H-4 and C-2‴, C-4‴; H-2‴ and C-4, C-5, C-6; and H-5‴ and C-3, C-3‴ (Figure 3).

Table 1. NMR Spectroscopic Data for Compounds 1 in CDCl3 (δ in ppm).

| Position | δH multi (J in Hz) | δC | Position | δH multi (J in Hz) | δC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a: 2.57 m | 28.4 | 1‴ | a: 2.64 dd (2.9, 14.4) | 28.4 |

| b: 2.77 overlapped | b: 3.33 dd (7.8, 14.4) | ||||

| 2 | 2.77 overlapped | 49.7 | 2‴ | 2.69 d (7.8) | 60.4 |

| 3 | 215.5 | 3‴ | 205.9 | ||

| 4 | 3.08 d (11.7) | 62.1 | 4‴ | a: 2.14 t (13.2) | 45.6 |

| b: 2.76 m | |||||

| 5 | 79.9 | 5‴ | 2.60 m | 37.7 | |

| 6 | 6.11 d (15.8) | 131.3 | 6‴ | 1.49 m | 36.4 |

| 7 | 6.60 d (15.8) | 131.0 | 7‴ | a: 2.45 m | 32.6 |

| b: 2.62–2.65 m | |||||

| 1′ | 140.2 | 1‴′ | 142.0 | ||

| 2′/6′ | 6.84 m | 128.1 | 2‴′/6‴′ | 7.09–7.12 overlapped | 129.1 |

| 3′/5′ | 7.08 m | 128.4 | 3‴′/5‴′ | 7.17 m | 128.2 |

| 4′ | 7.07 m | 126.1 | 4‴′ | 7.09–7.12 overlapped | 125.7 |

| 1″ | 135.7 | 1‴″ | 140.9 | ||

| 2″/6″ | 7.31 m | 126.6 | 2‴″/6‴″ | 7.05 m | 128.2 |

| 3″/5″ | 7.32–7.36 overlapped | 128.8 | 3‴″/5‴″ | 7.27 m | 128.6 |

| 4″ | 7.32–7.36 overlapped | 126.6 | 4‴″ | 7.20 m | 126.2 |

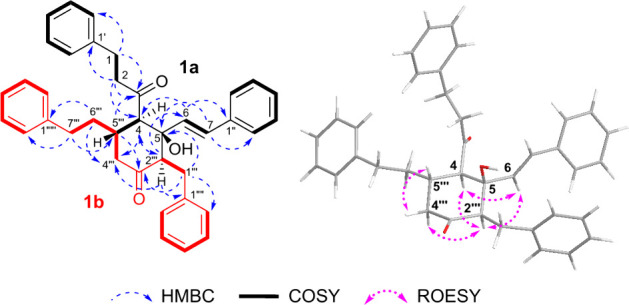

Figure 3.

1H–1H COSY, key HMBC, and ROESY correlations of 1.

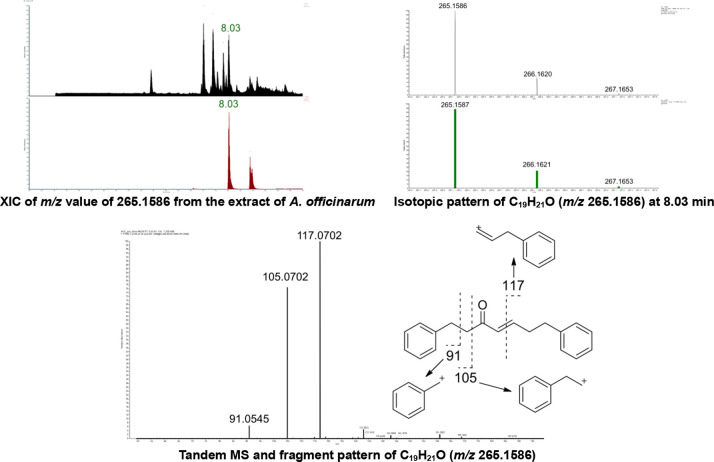

The relative configuration of the conjoined portion of 1a and 1b in compound 1 was determined by analyzing the ROESY spectrum. The correlations of H-4/H-6/H-2‴, H-2‴/H-4‴a, and H-4‴β/H-5‴ indicated that H-4, H-6, H-2‴, and H-4‴a were oriented in the same direction, and opposite to that of H-4‴β and H-5‴. Based on the above-mentioned spectroscopic data, the predicted absolute configurations of the four chiral centers (C-4, C-5, C-2‴, C-5‴) were confirmed to be 4R, 5S, 2‴R, and 5‴S, or 4S, 5R, 2‴S, and 5‴R, respectively. To ascertain the absolute configuration of 1, the ECD spectra of two reasonable stereoisomers, (4R, 5S, 2‴R, 5‴S)-1 and (4S, 5R, 2‴S, 5‴R)-1, were theoretically calculated using TD-DFT at B3LYP/6-31G+/(d,p) with the Gaussian 16 software. The theoretical ECD spectrum for (4R, 5S, 2‴R, 5‴S)-1 agreed well with the experimental ECD curve of 1 (Figure 4). Therefore, the absolute configuration of 1 was established as 4R, 5S, 2‴R, 5‴S.

Figure 4.

Comparison of experimental and calculated ECD spectra of 1.

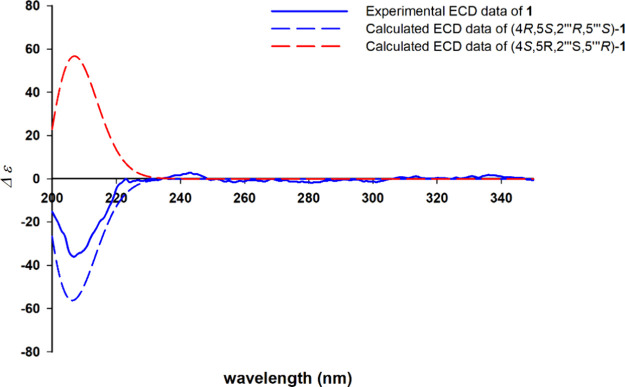

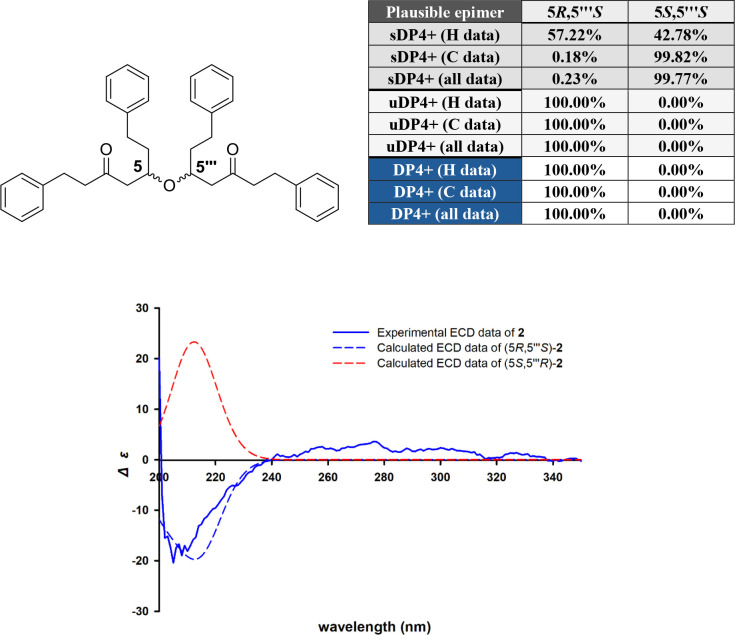

Alpiniofficinoid B (2) was isolated as a yellow oil. The molecular formula of 2, was determined to be C38H42O3 based on the HRESIMS data; m/z 569.3023 [M + Na]+ (Calcd for C38H42O3Na, m/z 569.30262). The IR spectrum showed the presence of carbonyl (1736 and 1647 cm–1) and aromatic ring (1467 cm–1) functional groups in 2. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 2 contained signals for only 21 hydrogens [δH 7.24–7.28 (4H, overlapped), 7.14–7.18 (6H, overlapped), 3.86 (1H, m), 2.85 (2H, t, J = 7.7 Hz), 2.70 (2H, t, J = 7.7 Hz), 2.62 (1H, dd, J = 6.6, 15.9 Hz), 2.55 (2H, m), 2.42 (1H, dd, J = 5.9, 15.9 Hz), and 1.72 (2H, m)], and 19 carbons [δC 208.4, 141.7, 141.0, 128.5 × 2, 128.4 × 4, 128.3 × 2, 126.1, 125.9, 72.4, 47.8, 45.6, 35.7, 31.3, 29.5], respectively (Table 2). This indicated that 2 is likely a dimeric diarylheptanoid with a symmetrical structure. The 2D NMR (HSQC, HMBC, and COSY) data revealed that one portion of the dimer is 5-hydroxy-1,7-diphenyl-3-heptanone, which is identical to that of alpinidinoid B (3) (Figure 5).13 A comparison of their 1D and 2D NMR as well as ECD data indicated that compounds 2 and 3 were determined to be stereoisomers, differing in the absolute configurations at C-5 and C-5‴. NMR calculation coupled with a DP4+ probability analysis was performed for the two possible isomers to determine the orientation of C-5 and C-5‴ of 2. The results indicated that (5R, 5‴S)-isomer was the more likely candidate structure, with a DP4+ probability (all data) of 100% (Figure 6). Therefore, the absolute configuration of 2 was predicted to be either (5R, 5‴S)-2 or (5S, 5‴R)-2. To determine the absolute configuration of 2, the ECD spectra of two plausible stereoisomers, (5R, 5‴S)-2 and (5S, 5‴R)-2, were theoretically calculated and the calculated ECD spectrum of (5R, 5‴S)-2 showed a strong correlation with the experimental ECD spectrum of 2. Consequently, the absolute configuration of 2 was confirmed as 5R, 5‴S (Figure 6).

Table 2. NMR Spectroscopic Data for Compounds 2 and 3 in CDCl3 (δ in ppm).

|

2 |

3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δH multi (J in Hz) | δC | δH multi (J in Hz) | δC |

| 1/1‴ | 2.85 t (7.7) | 29.5 | 2.88 t (7.5) | 29.5 |

| 2/2‴ | 2.70 t (7.7) | 45.6 | a: 2.77 dt (7.5, 17.5) | 45.5 |

| b: 2.68–2.72 overlapped | ||||

| 3/3‴ | 208.4 | 208.8 | ||

| 4/4‴ | a: 2.62 dd (6.6, 15.9) | 47.8 | a: 2.70 dd overlapped | 47.4 |

| b: 2.42 dd (5.6, 15.9) | b: 2.33 dd (5.2, 16.4) | |||

| 5/5‴ | 3.86 dd (5.6, 6.6) | 72.4 | 3.86 dd (5.2, 6.5) | 72.4 |

| 6/6‴ | 1.72 m | 35.7 | 1.74 m | 36.3 |

| 7/7‴ | 2.55 m | 31.3 | 2.61 m | 31.6 |

| 1′/1‴′ | 141.0 | 141.1 | ||

| 2′/2‴′/6′/6‴′ | 7.14–7.18 overlapped | 128.3 | 7.16–7.19 overlapped | 128.3 |

| 3′/3‴′/5′/5‴′ | 7.24–7.28 overlapped | 128.4 | 7.24–7.27 overlapped | 128.4 |

| 4′/4‴′ | 7.14–7.18 overlapped | 126.1 | 7.16–7.19 overlapped | 126.1 |

| 1″/1‴″ | 141.7 | 141.8 | ||

| 2″/2‴″/6″/6‴″ | 7.14–7.18 overlapped | 128.4 | 7.13 m | 128.4 |

| 3″/3‴″/5″/5‴″ | 7.24–7.28 overlapped | 128.5 | 7.24–7.27 overlapped | 128.5 |

| 4″/4‴″ | 7.14–7.18 overlapped | 125.9 | 7.16–7.19 overlapped | 125.9 |

Figure 5.

1H–1H COSY and key HMBC correlations of 2.

Figure 6.

DP4+ possibilities of possible isomer of 2 and ECD calculation spectra of 2.

The remaining known compounds 3-17 were identified as alpinidinoid B (3),13 alpinidinoid C (4),13 alpininoid B (5),8 alpininoid D (6),8 (4E)-1,7-diphenyl-4-hepten-3-one (7),15 (4E)-7-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-4-hepten-3-one (8),14 7-(4″-hydroxy-3′′-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenylhept-4-en-3-one (9),16 5-hydroxy-1,7-diphenyl-3-heptanone (10),14 5-hydroxy-7-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-3-heptanone (11),17 5-hydroxy-7-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-3-heptanone (12),14 5-methoxy-1,7-diphenyl-3-heptanone (13),14 5-methoxy-7-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-3-heptanone (14),16 (4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-diphenyl-4,6-heptadien-3-one (15),18 and 1,7-diphenyl-3,5-heptanedione (16)12 based on comparisons of the obtained HRESIMS and 1D NMR data with the published literature values (Figure 2).

To evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects of the isolated compounds, their inhibitory activity of NO production in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells was investigated (Table 3). None of the compounds showed cytotoxicity to RAW 264.7 cells at their effective concentrations. Remarkable inhibitory effects were noted for compounds 1, 7, and 9 with IC50 values of 14.7, 6.6, and 5.0 μM, respectively (the IC50 value of the positive control, aminoguanidine was 10.6 μM). Among the unusual diarylheptanoids, compound 1 demonstrated significantly higher inhibitory activity than the other five compounds 2-6. Within the monomeric diarylheptanoids, the presence of an olefinic bond between C-4 and C-5 was found to significantly enhance the inhibitory activity. However, hydroxylation at the C-4” position (compound 8, IC50 value: > 50 μM) resulted in a loss of activity, which was recovered by further methoxylation at the C-3” position (compound 9, IC50 value: 5.0 μM).

Table 3. Inhibitory Effects of Compounds 1–16 on NO Production in LPS-Induced RAW 264.7 Cellsa.

| Compound | IC50 (μM)a | Compound | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.7 ± 1.1 | 9 | 5.0 ± 1.2 |

| 2 | >50 | 10 | >50 |

| 3 | >50 | 11 | >50 |

| 4 | 26.0 ± 0.9 | 12 | 29.8 ± 5.2 |

| 5 | >50 | 13 | 48.1 ± 3.9 |

| 6 | 25.9 ± 1.2 | 14 | 33.6 ± 4.3 |

| 7 | 6.6 ± 2.7 | 15 | 45.2 ± 5.0 |

| 8 | >50 | 16 | 40.0 ± 2.4 |

| Aminoguanidine | 10.6 ± 1.4 |

Results are indicated as the mean IC50 ± SD values in μM from triplicate experiments.

Conclusions

In this study, the targeted isolation of unusual dimeric diarylheptanoids was applied based on tandem MS fragment analysis. The major diarylheptanoid compound 7 displayed MS2 fragmentation patterns specific to diarylheptanoids at m/z 91, 105, and 117. Among the peaks with m/z values ranging from 450 to 600, those displaying fragment ions at m/z 91, 105, and 117 were selected and isolated. As a result, two previously undescribed dimeric diarylheptanoids (1-2) and four unusual diarylheptanoids (3-6) along with ten monomeric diarylheptanoids (7-16) were isolated through various chromatographic techniques from the rhizomes of A. officinarum. Compound 1 showed significantly higher inhibitory activity against NO production in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells with an IC50 value of 14.7 μM than the other unusual diarylheptanoids 2-6. Moreover, the inhibitory effects of the monomeric diarylheptanoids were significantly influenced by the presence of an olefinic bond between C-4 and C-5, as well as by the substituent group on the aromatic ring.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured using a JASCO DIP-1000 polarimeter. UV spectra were recorded using a JASCO UV-550 spectrophotometer. Experimental ECD spectra were measured using a JASCO J-715 spectrometer. NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE 400, 500, 800, and 900 MHz spectrometers using CDCl3 as the solvent. HRESIMS data were collected using an Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer coupled with a Vanquish UHPLC system and a diode array detector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Column chromatography was performed using silica gel (70–230 mesh and 230–400 mesh, Merck) and Lichroprep RP-18 (40–63 μm, Merck). MPLC was performed using a Biotage Isolera Prime chromatography system. Preparative HPLC was performed using a Waters HPLC system equipped with two Waters 515 pumps, a 2996 photodiode-array detector, and YMC J’sphere ODS-H80 columns (4 μm, 150 × 20 mm, i.d., flow rate 6 mL/min). TLC was performed using precoated silica gel 60 F254 (0.25 mm, Merck) plates, and the spots were visualized using a 10% vanillin-H2SO4 in water spray reagent.

Plant Material

Dried rhizomes of A. officinarum were purchased from the Kyungdong Herbal market (Seoul, South Korea) in January 2021 and authenticated by one of the authors (B. Y. Hwang). A voucher specimen (CBNU-2021–01-AO) was deposited at the Herbarium of the College of Pharmacy, Chungbuk National University, South Korea.

Extraction and Isolation

The dried rhizomes of A. officinarum (3.0 kg) were extracted with MeOH (3 × 18 L) by maceration for 3 days, at 25 °C, followed by filtration and evaporation of the filtrate under reduced pressure to obtain the MeOH extract. A suspension of the extract (300 g) in distilled water was sequentially partitioned using n-hexane (2 × 4 L), CH2Cl2 (2 × 4 L), EtOAc (2 × 4 L), and n-BuOH (2 × 4 L). In the n-hexane- and CH2Cl2-soluble fractions, the LC-MS peaks appearing in the m/z range of 450–600, which showed the fragmentation patterns at m/z 91, 105, and 117, specific to diaryheptanoids, were targeted for isolation (Figure S17). The n-hexane-soluble fraction (27.1 g) was subjected to silica open column chromatography and eluted using an n-hexane–EtOAc gradient system (50:1 to 1:1) to obtain seven fractions (AOH1 – AOH7). AOH3 (2.4 g) was further separated via RP-MPLC, using a MeOH–H2O gradient elution system (40:60 to 100:0) to obtain 7 subfractions (AOH3–1 – AOH3–7) and alpininoid D (6). AOH4 (2.6 g) was subjected to silica gel column chromatography (100% CH2Cl2, isocratic) to obtain 7 subfractions (AOH4–1 – AOH4–7). AOH4–4 (162 mg) was further purified using preparative HPLC (MeCN–H2O, 85:15, isocratic) to yield compound 1 (tR = 10.2 min, 0.5 mg), alpininoid B (5) (tR = 13.6 min, 5.5 mg), compound 2 (tR = 18.6 min, 0.5 mg), and alpinidinoid B (3) (tR = 19.5 min, 0.9 mg). AOH4–7 (513 mg) was further separated via RP-MPLC using a MeOH–H2O gradient elution system (30:70 to 100:0) to obtain 7 subfractions (AOH4–7–1 – AOH4–7–7). AOH4–7–5 (33.9 mg) was further purified using preparative HPLC (MeCN–H2O, 90:10, isocratic) to yield alpinidinoid C (4) (tR = 21.1 min, 1.2 mg). The CH2Cl2-soluble fraction (61.2 g) was subjected to silica gel column chromatography, eluting with a CH2Cl2–MeOH gradient system (100:0 to 0:100) to obtain 7 fractions (AOC1 – AOC7). AOC2 (2.2 g) was further separated using RP-MPLC, using a MeOH–H2O gradient elution system (45:55 – 100:0) to obtain 4 subfractions (AOC2–1 – AOC2–4). AOC2–3 (580 mg) was further purified via preparative HPLC (MeCN–H2O, 75:25, isocratic) to yield 5 compounds, 1,7-diphenyl-3,5-heptanedione (16) (tR = 11.2 min, 12.5 mg), 5-methoxy-1,7-diphenyl-3-heptanone (13) (tR = 19.8 min, 1.2 mg), (4E)-1,7-diphenyl-4-hepten-3-one (7) (tR = 20.5 min, 23.8 mg), and (4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-diphenyl-4,6-heptadien-3-one (15) (tR = 31.1 min, 2.3 mg). A previous study confirmed that compound 16 exists as a mixture of keto-enol tautomers.12 AOC3 (3.1 g) was further separated using RP-MPLC (MeOH–H2O gradient system, 50:50 – 100:0) to obtain 4 subfractions (AOC3–1 – AOC3–4). AOC3–2 (1.87 g) was separated using Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 1:1, isocratic) to derive 2 subfractions (AOC3–2–1 and AOC3–2–2). AOC3–2–2 (22 mg) was subsequently purified using preparative HPLC (MeCN–H2O, 60:40, isocratic) to acquire 7-(4″-hydroxy-3′′-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenylhept-4-en-3-one (9) (tR = 19.5 min, 1.5 mg), and 5-hydroxy-1,7-diphenyl-3-heptanone (10) (tR = 22.3 min, 1.5 mg). AOC5 (40.4 g) was separated using silica gel chromatography and fractionated using a CH2Cl2–MeOH gradient elution system (30:1 to 1:1) to obtain 6 subfractions (AOC5–1 – AOC5–6). AOC5–3 (3.68 g) was subsequently isolated via RP-MPLC under MeCN–H2O gradient elution (55:45 – 100:0) to derive 5 subfractions (AOC5–3–1 – AOC5–3–5). AOC5–3–4 (1.1 g) was further purified using preparative HPLC (MeCN–H2O, 50:50, isocratic) to obtain 5-methoxy-7-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-3-heptanone (14) (tR = 36.0 min, 34.8 mg), and (4E)-7-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-4-hepten-3-one (8) (tR = 38.0 min, 20.1 mg). AOC5–6 (2.69 g) was subjected to RP-MPLC and eluted using a MeOH–H2O gradient system (30:70 – 100:0) to yield 5 subfractions (AOC5–6–1 – AOC5–6–5). AOC5–6–2 (507 mg) was subsequently separated using Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 1:1, isocratic) to obtain 5 subfractions (AOC5–6–2–1 – AOC5–6–2–5). AOC5–6–2–2 (316 mg) was further purified using preparative HPLC, eluting with a MeCN–H2O gradient elution system (20:80 – 60:40) to obtain 5-hydroxy-7-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-3-heptanone (11) (tR = 29.5 min, 5.8 mg), and 5-hydroxy-7-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-3-heptanone (12) (tR = 30.9 min, 4.3 mg).

Alpiniofficinoid A (1)

Pale yellow oil; [α]D25 + 25 (c 0.05, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 209 (1.6), 260 (0.4) nm; FT-IR νmax 3389, 3026, 2967, 2923, 1714, 1650, 1495, 1437, 1368, 1317, 1016, 952, 746, 689 cm–1; ECD (c 0.05, EtOH) λmax (Δε) 208 (−37.2) nm; 1H NMR (900 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (225 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 565.2714 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C38H38O323Na, 565.27132).

Alpiniofficinoid B (2)

Yellowish oil; [α]D25 + 27 (c 0.08, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (1.8), 267 (0.2) nm; FT-IR νmax 2919, 2850, 1736, 1647, 1467, 1374, 1247, 1081 cm–1; ECD (c 0.08, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 203 (−20.5) nm; 1H NMR (900 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (225 MHz, CDCl3), see Table 2; HRESIMS m/z 569.3022 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C38H42O323Na, 569.30262).

LC-HRMS/MS Analysis

LC-HRMS/MS analysis was performed using an Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer coupled with a Vanquish UHPLC system and a diode array detector. The n-hexane and CH2Cl2-soluble fractions were subjected to LC-MS/MS on a YMC-Triart C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) using a gradient elution system (A:B, 90:10 to 0:100 over 11 min, flow rate 0.3 mL/min) wherein the mobile phase comprised H2O (A) and CH3CN (B), both containing 0.1% formic acid. The sample injection volume was fixed at 2 μL, and the column oven temperature was set to 30 °C. Mass detection was performed in the m/z range of 100–2000, and the resolution of the Orbitrap mass analyzer was fixed at 60,000 for the full MS scan, and at 15,000 for the data-dependent MSn scan. The HESI ion source parameters were configured as follows: spray voltage, 3.5 kV; vaporizer temperature, 275 °C; ion transfer tube temperature, 320 °C; sheath gas flow rate, 50 L/min; aux gas flow rate, 15 L/min; and sweep gas flow rate, 1 L/min. A normalized higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) energy of 30% was used for ion collisions in the Orbitrap detector. MS/MS fragmentation was achieved using the data-dependent MSn mode to obtain an MS2 spectrum with the four most intense ions. A dynamic exclusion filter was implemented to exclude repeated fragmentation of ions within 2.5 s after acquiring the MS2 spectrum.

NMR and ECD Calculations

The NMR data for compounds 2 and 3, as well as the ECD data for compounds 1 and 2, were calculated using the method described by Liu et al.13 The Spartan’24 software was used for conformational analysis. Conformer distribution was calculated using a systematic method under a molecular mechanics force field (MMFF) by applying an energy window of 10 kJ/mol. In the conformer distribution, conformers above 3% of the Boltzmann population were optimized using the Gaussian 16 W package for density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d) level. The optimized conformers were subjected to theoretical NMR and ECD calculations with the gauge-independent atomic orbital (GIAO) method at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level in CHCl3 with PCM, and time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) at the B3LYP/6-31+G (d, p) level in MeOH with CPCM, respectively, using the Gaussian 16 W program. The calculated NMR chemical shifts were performed statistical analyses with experimental chemical shifts by using DP4+ method. Calculated ECD spectra were obtained by summing the spectra of each conformer after the Boltzmann weighting. The resulting ECD spectra were corrected based on the UV and simulated spectra using SpecDis 1.71.

Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Production and Cytotoxicity

The inhibitory effects of the isolated compounds on nitric oxide (NO) production were evaluated using RAW 264.7 cells. The purity of the isolated compounds was verified as >97% by HPLC (Figures S18–S20). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. RAW 264.7 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well and incubated for 6 h. The cells were stimulated with 1 μg/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to induce NO production. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the nitrite concentration in the cell culture supernatant was measured using the Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid and 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride). Absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a microplate reader against a calibration curve of sodium nitrite standards. To assess cytotoxicity, cell viability was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. After the removal of the supernatant for the NO assay, 50 μL of the MTT solution (5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37 °C. DMSO (100 μL) was then added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals formed by metabolically active cells. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MIST) (No. 2020R1A2C1008406). The authors wish to thank the Korea Basic Science Institute for the NMR spectroscopic measurements.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c07987.

1D NMR, 2D NMR, HRESIMS, and FT-IR of compounds 1 and 2, NMR computational details of compound 2, and ECD computational details of compounds 1 and 2 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abubakar I. B.; Malami I.; Yahaya Y.; Sule S. M. A review on the ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Alpinia officinarum Hance. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 224, 45–62. 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basri A. M.; Taha H.; Ahmad N. A review on the pharmacological activities and phytochemicals of Alpinia officinarum (Galangal) extracts derived from bioassay-guided fractionation and isolation. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2017, 11, 43–56. 10.4103/phrev.phrev_55_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. J.; Zhu L. J.; Zhao Y. Q.; Zhen Y. Q.; Zhang L.; Lin C. C.; Chen L. X. Diarylheptanoid: A privileged structure in drug discovery. Fitoterapia 2020, 142, 104490 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao F.; Huang Y.; Wang Y.; He X. Anti-inflammatory diarylheptanoids and phenolics from the rhizomes of kencur (Kaempferia galanga L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 125, 454–461. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Youn I.; Han A. R.; Piao D.; Lee H.; Kwak H.; Lee Y.; Nam J. W.; Seo E. K. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of the genus Alpinia from 2016 to 2023. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2024, 41, 1346. 10.1039/D4NP00004H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Pan D. B.; Pang Q. Q.; Zhou M.; Yao X. J.; Yao X. S.; Li H. B.; Yu Y. Diarylheptanoid analogues from the rhizomes of Zingiber officinale and their anti-tumour activity. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 29376–29384. 10.1039/D1RA03592D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung N. H.; Kim S. K.; Ra J. C.; Zhao Y. Z.; Sohn D. H.; Kim Y. H. Antioxidative and hepatoprotective diarylheptanoids from the bark of Alnus japonica. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 626–629. 10.1055/s-0029-1240595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Wu Z. L.; Huang X. J.; Peng Y.; Huang X.; Shi L.; Wang Y.; Ye W. C. Evaluation of diarylheptanoid–terpene adduct enantiomers from Alpinia officinarum for neuroprotective activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 162–170. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. H.Tandem mass spectrometry. In Mass Spectrometry, 3rd ed.; Gross J. H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017, pp 539–612. [Google Scholar]

- Bittremieux W.; Schmid R.; Huber F.; van der Hooft J. J. J.; Wang M.; Dorrestein P. C. Comparison of cosine, modified cosine, and neutral loss based spectrum alignment for discovery of structurally related molecules. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 33, 1733–1744. 10.1021/jasms.2c00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisporna A.; Benton H. P.; Chen A.; Derks R. J. E.; Galano J. M.; Giera M.; Siuzdak G. Neutral loss mass spectral data enhances molecular similarity analysis in METLIN. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 33, 530–534. 10.1021/jasms.1c00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athamaprasangsa S.; Buntrarongroj U.; Dampawan P.; Ongkavoranan N.; Rukachaisirikul V.; Sethijinda S.; Sornnarintra M.; Sriwub P.; Taylor W. C. A 17-diarylheptanoid from Alpinia conchigera. Phytochemistry 1994, 37, 871–873. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)90374-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Wang X.; Shi Q.; Li L.; Zhang Q.; Wu Z. L.; Huang X. J.; Zhang Q. W.; Ye W. C.; Wang Y.; Shi L. Dimeric diarylheptanoids with neuroprotective activities from rhizomes of Alpinia officinarum. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10167–10175. 10.1021/acsomega.0c01019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itokawa H.; Morita H.; Midorikawa I.; Aiyama R.; Morita M. Diarylheptanoids from the rhizome of Alpinia officinarum Hance. Chem. Pham. Bull. 1985, 33, 4889–4893. 10.1248/cpb.33.4889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tori M.; Hashimoto A.; Hirose K.; Asakawa Y. Diarylheptanoids, flavonoids, stilbenoids, sesquiterpenoids and a phenanthrene from Alnus maximowiczii. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 1263–1264. 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00439-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Rafi M. M.; Zhu N.; Ryu K.; Sang S.; Ho C. T.; Rosen R. T.. Separation and bioactivity of diarylheptanoids from lesser galangal (Alpinia officinarum). In Food Factors in Health Promotion and Disease Prevention; Shahidi F.; Ho C. T.; Osawa T.; Watanabe T., Ed.; ACS Symposium Series, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC., 2003, pp 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi F.; Iwakami S.; Shibuya M.; Hanaoka F.; Sankawa U. Inhibition of prostaglandin and leukotriene biosynthesis by gingerols and diarylheptanoids. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1992, 40, 387–391. 10.1248/cpb.40.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroyanagi M.; Noro T.; Fukushima S.; Aiyama R.; Ikuta A.; Itokawa H.; Morita M. Studies on the constituents of the seeds of Alpinia katsumadai Hayata. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1983, 31, 1544–1550. 10.1248/cpb.31.1544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.