Abstract

Considering that men today face social and cultural pressures to behave in certain ways, the objective of this study was to analyze the construction of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) from the perspective of university students who identify themselves as male in a developing country. This is a qualitative study carried out through semi-structured interviews, with 15 students from the state of São Paulo, Brazil, from May to July 2021. The data were analyzed thematically and anchored in the ecological framework of understanding violence. Two final themes were identified: “‘A man has to show that he is a man from a young age’—Social construction of violence” and “‘At first it is hard to notice’—The subtlety of violence.” It was identified that this phenomenon is configured as a historical, social, and cultural construction, mainly sustained by what is attributed to “being a man” in society and, consequently, the actions expected by this attribution. These perceptions are transversal in relationships within society and go beyond generations—and they are a layer in addition to memories of violence experienced or witnessed taking place in determining IPV experiences. Living in communities that legitimize gender inequities, generally in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, is a prominent factor influencing IPV among the studied population. In this context, psychological violence emerges as preponderant and triggers other forms of violence, which are difficult to notice and veiled behind prejudices. Educational practices for healthy relationships are proposed and emphasized from basic to higher education as well as peer and professional support.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, interpersonal relationships, gender role, gender-based violence, young adult, qualitative research

Introduction

Violence may be classified in multiple ways, with specific characteristics according to gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and age group. The prevalence of abusive relationships among young people has been the subject of several studies (Antón et al., 2020; Nascimento et al., 2018; A. P. F. Oliveira et al., 2021; M. S. Souza et al., 2021). The term Teen Dating Violence (TDV) has been the most used to conceptualize Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) among people aged 10 to 24. TDV may occur through physical, psychological, or sexual violence, and may include stalking. It can occur in occasional or permanent relationships and is also common in digital media (Nascimento et al., 2018). Many young men committing acts of violence have few skills to face the complexities that intimate relationships may produce, which is expected as this is a time of experimentation. These issues may result in limited communicative and relational skills, leading to IPV (Grest et al., 2022).

A meta-analytic review of 101 studies, mainly North American, demonstrated that IPV is a common phenomenon among adolescents and young adults. In this review, there was a general prevalence (victimization or perpetration) of 20% of physical violence and 9% of sexual violence; physical violence ranged from 1% to 61%, while with sexual violence the variation was from 1% to 54% (Wincentak et al., 2017). According to this review, IPV affects both girls and boys, with girls committing more physical violence (25%) than boys (13%) but is more affected (14%) by sexual violence than boys (8%; Wincentak et al., 2017).

In a systematic review carried out to find out the prevalence of IPV in Europe, the authors found that victimization due to psychological violence ranged from 5.9% to 95.5% among girls and 5.6% to 94.5% among boys; regarding physical violence, the prevalence ranged from 2.2% to 32.9% among girls and 0.8% to 29.8% among boys. Regarding sexual violence, there was a prevalence of 4.8% to 41% among girls and 2.4% to 39% for boys; finally, internet violence affected between 0.6% and 48% of girls and 1% to 46% of boys (Tomaszewska & Schuster, 2021). It is understood that although the manifestations of violence are typified separately, this study assumes that they occur in conjunction, as will be discussed further subsequently.

IPV has consequences for people’s physical and mental health; when it happens in specific moments such as adolescence and youth, it may have greater impacts, even for future violence (Nascimento et al., 2018). In a systematic review of IPV among adolescents, the authors found that the consequences of gender-based violence range from psychiatric disorders, mainly depressive and anxiety disorders, sexual disorders, drug abuse, and even suicidal behavior (Taquette & Monteiro, 2019).

Gender inequities have been the subject of social movements and are discussed in different spheres; they are important elements for the construction of violent intimate relationships (A. P. F. Oliveira et al., 2021; Saffioti, 2015). Despite changes through women’s occupation of public spaces, patriarchy remains structured and veiled. There is, therefore, gender inequity resulting from social organization. The vestiges of the patriarchal system remain, with men’s dominance over women prevailing in all aspects, from economics to established sexual and reproductive rights. This hierarchy model promotes a power structure that goes beyond the field of ideology, also manifesting itself through violence, characterized by abusive behavior in affective relationships (Saffioti, 2015).

Living and growing up in developing and underdeveloped countries are posed as risk factors for the maintenance of a patriarchal culture, leading to greater gender inequities, including violence (Taquette & Monteiro, 2019; Wincentak et al., 2017). Brazil, for instance, has been experiencing an increasing concentration of power in highly conservative and religious fundamentalist politicians. As a result, there were important setbacks in policies and programs that promoted gender equity, sexual diversity, democracy, and access to comprehensive sexual education in a country where the majority of sexual violence against girls and women is perpetuated by male family members (Montenegro et al., 2020). Studies have looked at the perceptions of IPV mainly from the perspective of women, sexual minorities, and gender minorities; however, people who identify as male have little been approached (Silva et al., 2020, 2022).

A qualitative study that addressed IPV among adolescents from a region of high social vulnerability in São Paulo, Brazil, showed a prejudiced view regarding female behavior on the part of male participants. IPV becomes more visible in dating relationships, where commitment and exclusivity are seen as primary characteristics, justifying possession and control. This dynamic is not observed in relationships among young people who are not dating. Such violence is often subtle and is perceived as necessary for building trust within a dating relationship (A. P. F. Oliveira et al., 2021).

Considering the influence of historical, social, and cultural constructions of being a man in the context of a developing country, in addition to the scientific gaps in looking at IPV by people who identify as male, a guiding question is brought: What are the perceptions of young people who identify as male regarding the construction of IPV? To support the answer to this question, the conceptual framework of this study is the ecological framework for understanding violence proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2022). This framework is based on the evidence that no single factor can explain the greater risk of some people or groups to interpersonal violence, while others are more protected from it. This phenomenon is understood as a result of the interaction of multiple factors at four levels—individual, relational, community, and social (WHO, 2022). In this way, understandings, actions, and interventions in life contexts must be articulated to consider these multiple aspects.

In view of the above, this research aimed to analyze the construction of IPV from the perspective of university students who identify as male in a developing country.

Method

Qualitative approach research (Flick, 2009), based on the Ecological Framework for Understanding Violence (WHO, 2022).

The study was carried out at a university in the countryside of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Participants were selected based on the following inclusion criteria to be a university student who identifies as male, according to the age range recommended by the World Health Organization—between 15 and 24 years old (in the case of a university context, between 17 and 24 years old); to have electronic equipment with the possibility of internet access; to be enrolled and attending a major in STEM, which at this university would be Computer Science, Civil Engineering, Computer Engineering, Materials Engineering, Manufacturing Engineering, Electrical Engineering, Physical Engineering, Forest Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Chemical Engineering, Statistics, Physics, Mathematics, and Chemistry. The definition of this last criterion was to approach an area that generally does not bring discussions about violence as a curricular component and also because these are courses with a predominance of male students. The exclusion criterion was being in severe psychological distress and self-reported during the collection.

The invitation to participate and subsequent contact with students was mediated by the Academic Centers, which disseminated the research, as well as exposure on social networks, such as the university’s Facebook® and Whatsapp®, in March 2021. Thirty people were interested, but 15 continued by filling out the form, scheduling the interview, and actually participating in it.

The data collection strategy was a semi-structured interview, carried out through a freely accessible online communication platform. This interview, in accordance with the literature, started from questions previously established by the researchers to guide the conversation with a defined purpose but allowed new statements to emerge from the interaction with the participants (Minayo, 2014). In the case of this study, the interview script contained the following pre-established questions:

What do you understand about violence? What do you think about violent intimate relationships? Have you ever witnessed or do you know someone who has experienced some type of violence within intimate relationships? How do you think violence appears in relationships? How do you think it is constructed and materialized?

Before data collection, a form for sociodemographic and intimate relationship characterization was made available via Google Forms®. Data collection took place from May to July 2021 and was carried out by the first author of this article. A first interview was carried out and discussed with the last author of the study, with no need to adapt the script.

The interviews were mediated via the communication platforms Google Hangout® or WhatsApp®. The invitation to participate in the research occurred through contact via WhatsApp® message. At this point, the study, its objectives, and data collection strategy were presented and, upon demonstration of interest and availability to contribute, the link to the online form was sent via message. This form contained the Informed Consent Form (ICF) and, subsequently, the characterization form. Afterward, the date and time for the interview were scheduled.

Fictitious names were established for each interviewee so that their experiences and opinions could be shared without fear of being exposed. The interviews lasted between 25 and 40 min. Each interview was recorded in the application, saved with the consent of the participants, and later transcribed in full into a Word® document.

In this study, data saturation was sought through in-depth, detailed, and complex discussion of the data to ensure the understanding of a phenomenon of interest (Hennink & Kaiser, 2022). Such saturation was found in the 13th interview and two more interviews were carried out to compose the data.

The data were analyzed using the reflexive thematic analysis technique, a method aimed at identifying and analyzing qualitative data patterns (Clarke & Braun, 2019). The following steps were carried out in the analysis: data familiarization; coding; search for themes; review of themes; definition and naming of themes; and final writing (Clarke & Braun, 2019). To ensure greater validity and reliability, the construction of codes and themes was carried out by two independent researchers and validated by the first author’s research group. 73 initial codes; four intermediate and two final themes were generated.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in 2021, in accordance with Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council, with opinion number 4,795,400, which allowed data collection to begin. Also considering the precepts of this resolution, the ICF was used for all participants who agreed to participate in the research, and the interviewees were identified with fictitious names for non-identification.

Results

In total, 15 male students, aged between 21 and 24, participated in the study, all enrolled in different STEM undergraduate courses. Regarding skin color, 93.3% (n = 14) declared themselves White and 6.6% (n = 1) declared to be Brown. Among the participants, 66.6% (n = 10) said they had no religion, 20% (n = 3) declared themselves Catholic, 6.6% (n = 1) declared to be spiritist, and 6.6% (n = 1) declared to be evangelical. Most interviewees (73.3%, n = 11) declared themselves to be heterosexual (people who feel sexual and/or romantic attraction to people of the opposite gender), while 20% (n = 3) declared to be bisexual (people who feel sexual and/or romantic attraction to people of more than one gender), and 6.6% (n = 1) declared to homosexual (people who feel sexual and/or romantic attraction to a person of the same gender). Only 6.6% (n = 1) of those interviewed declared to be transgender. Of those interviewed, 20% (n = 3) said they were in a serious relationship and one had children.

When asked about the marital status of their guardians, 60% (n = 9) of participants responded that their parents live together, 26.6% (n = 4) of them said that their parents live separately, and 13.3% (n = 2) said that their mother is a widow. In total, 33.3% (n = 5) of respondents said that the female and male guardians had completed higher education. Considering the relationships experienced by students, the average age at which they started “hooking up”/dating was 15 years old, with the minimum age being 12 years old and the maximum age being 19 years old. All participants said they had already had sexual intercourse and the average age at first intercourse was 17.5 years old. Of the 15 students, 46.6% (n = 7) said they currently only have sexual relations with a steady partner.

When asked about the dynamics of recent relationships, 26.6% (n = 4) claimed that they used to argue often with their last partner, 40% (n = 6) said they rarely argued, and 33.3% (n = 5) said they never argued. Of the 15 interviewees, 13.3% (n = 2) said they had been victims of psychological violence by the person they had a relationship with and one participant said he had been violent toward his partner, committing psychological violence.

The analysis of qualitative data allowed the identification of two central themes: “‘A man has to show that he is a man from a young age’—Social construction of violence” and “‘At first it is hard to notice’—The subtlety of violence.”

“A Man Has to Show That He Is a Man From a Young Age”—Social Construction of Violence

In this category, the participants addressed the social, historical, and cultural construction of violence linked to the meaning of “being a man” in society. The participants brought up the fact that there is a normalization of this phenomenon, with it being even more common for men to practice it. Men learn how to respond within relationships daily, especially during childhood through their interactions with their parents. This guidance continues to shape their development as individuals who identify as male.

When asked about the construction of violent relationships, the participants related it to what they experienced and learned in childhood about being a man—an attitude of being superior to women, being strong, not communicating in a non-violent way, and not accepting “no” as an answer:

People have models, in the case of parents or guardians, that they tend to follow unconsciously. It is part of being human to follow a model, and that model is not always the healthiest for society. Sometimes it is an abusive, problematic model. (Felipe)B

I think that, most of the time, it is through the way we grow up that we are taught how to deal with things. To begin with, our patriarchal society. The man who, from a young age, has to show that he is a man, has to show that he is in charge, wants to teach people how to live according to the law of the strongest. However, he is not taught to lower his head, I’m not even saying that he is to lower his head, because that is wrong, but he is not taught to understand the side of other people, to understand a “no,” he is not taught how to [have a] dialogue. (Otávio)

According to the participants, this formation is a reflection of the cultural construction of a patriarchal society, even at a political level, which perpetuates gender inequities by maintaining structural machismo:

I’m answering this survey and I’m in the countryside of northeastern Brazil. There’s a lot of talk here about cultural behavior, where people think that, for example, if you have a female partner, she cannot go out alone, or something like that. And arguing, hitting, doing something with your partner would be justifiable. I am saying this as a cultural, regional issue. (Danilo)

I think violence is always linked to the history of humanity. If I were to link the various types of violence that we suffer, I would say that the primary cause is machismo. Homophobia, racism, transphobia, all these types of violence for me, are closely linked to machismo. A sexist society, in which no matter how much it says it is not sexist, “it is just an opinion,” we know it is not like that. It is something that will hurt the freedom, personality, and dignity of other people. People try to simplify violence, they try to beautify violence. (Regis)

Considering a continental country like Brazil, there are regions—as mentioned by Danilo—that have greater roots in traditional gender norms. These regions are also more socioeconomically disadvantaged. The Brazilian Northeast’s low per capita Gross Domestic Product and productivity growth are due to historical and political factors, with limited prospects for convergence with the national average.

Supported by family, social, and community constructions that give meaning to “being a man” in this violent perception, it is revealed that the phenomenon of violence spans generations. Further still, when children grow in spaces where the male figure uses different types of violence in their daily emotional relationships, these actions become normalized as aspects that are natural to “being a man”:

Well, I think it is something built, right, since your childhood. If you have contact with, for example, a sexist father who beats your mother, you tend to think that this is normal, to normalize this situation. And this applies to other forms of violence as well. (Allan)

So this often comes, especially from my father, as something violent, with racist, homophobic, and sexist comments, for example. So it is an idea that he has in his mind, from the education and upbringing he had, that he has to change (. . .) Then I think violence is very linked to our home. . . (Regis)

Experiencing violent situations in childhood also emerged as an aspect to be considered in the construction of violent intimate relationships. According to the participants, such experiences are common and bring emotional marks that need to be worked on:

It could be from a family sphere, which we see is more common. Maybe the person suffered some type of violence as a child, some type of trauma, not necessarily sexual. But maybe the person had some trauma and never anyone who maybe had a little more sense, because we are talking about a child here or a young person, no one identified it and tried to correct it. (Pedro)

I have already suffered some types of violence in family relationships, specifically. But it was nothing, so to speak, out of the ordinary, that is, it was naturalized (. . .) Unfortunately, dealing with these things involves rough therapy. (Danilo)

Some trauma, some psychological issue, an unresolved person, and this ends up generating violent behavior. Maybe this person was raised to believe that violent behavior is normal. (Felipe)

Issues like these are so normalized that they are not problematized and continue to inspire behavior for victims who suffer and live with violence. The following statement shows the feeling of ownership exercised over another person, which, due to the cultural construction of society, is generally the woman:

I think it is because I was raised in a context where, if I have a relationship with someone, that person is mine, I have power over that person. If nothing is right, the way I want it, it is wrong, and then I have the right to offend these people and commit violence, in this case. In my case, after I started the [gender] transition, I took my father as a male reference. So I ended up reproducing everything I saw in my entire childhood because I thought it was normal and I thought that was the role of a man, I thought that was the power I had. (Allan)

In this context, participants emphasized that, because people naturalize and live with violent acts since childhood, there is no perception and questioning about violent actions. The interviewees reinforced that these elements sustain the cycle of violence, its historical character, and its transgenerationality:

Violence is born from violence, which is when you grow up thinking it is natural, you grow up thinking it is the standard and that everything is fine, and that is it. These cycles are basically cycles like “oh, I grew up in this environment, violence was normal, I did not think it was special, that it was so serious” so the person kept repeating that. (Danilo)

Intimate relationships are developed, with violent contours not noticeable by victims and perpetrators. The difficulty of realizing that someone has problems is directly related to the naturalization of this problem. Coming from a context in which violence is common, living with it is not an impediment, that culminates in negative emotional experiences at this important stage of personal and social development:

There are many people who realize that they have a violent partner, but continue to think that this is isolated behavior or something like that. (Felipe)

“At First It Is Hard to Notice”—The Subtlety of Violence

In the scenario highlighted in the previous theme, elements that the participants once considered “subtle” but today are recognized as forms of violence. The interviewees reinforced that the difficulty in perceiving violence is linked to the subtlety with which it is manifested, very much based on the naturalization discussed in the previous theme. Psychological violence is the first to appear in relationships, materializing through jealousy, control, and possession, which is justified as care and concern:

I think that at first, it is hard to notice, in those first moments of the relationship. But some signs appear, such as excessive jealousy, or wanting to limit what the partner does in some situations. And, as time goes by and both people do not realize it, this kind of thing gets more and more profound and intense. (Éder)

The discourse of “care and concern” is what keeps the victim tied to the relationship, as there is a false idea that such action is an effective and healthy part of the relationship. The expectation may be accompanied by new types of violence, as pointed out in the following statement:

I think violence has several stages. I think that the beginning, I believe it is a more subtle stage, that sometimes people do not realize, that is, it is not violence yet, but it can be an attitude that can lead to violence, like a symptom. It comes in stages of little things, which sometimes you can even notice, but it is like “ah, it’s okay, it’s no big deal..” Or like, it is even acceptable and then, one day, things change, you know, and then it goes from something that was subtle, acceptable, tolerable to something that is no longer good, that already hurts, that already hurts, that already becomes aggression. (Renan)

In this context, the participants brought up particularities in the experience of psychological violence, when the partners sought to avoid ending the relationship through “emotional blackmail”:

I believe that I have experienced some more subtle type of violence, which is emotional blackmail. You force a person to be close all the time, or to behave in certain ways, through blackmail. In my case, the person said they were going to hurt themselves, kill themselves, etc (. . .) We lived through this pandemic period and I, having two older parents, a diabetic, hypertensive father, could not leave the house. So the person used to lie about being sick. (Felipe)

Then one day we were dating long distance, at the end of the relationship, I lived here in São Carlos and she wasn’t from here, and she cut herself off when we were talking about breaking up. (Leandro)

I remember her saying “oh I’m going to kill myself” (. . .) But I remember that day was very strong. She sent a photo of a drawer saying “this drawer has a false bottom with letters for several people. There is a letter for you. So after I do it, in a little while, go find your letter and read yours, give it to people and such.” (Pedro)

Ended up using expressions to weigh on the conscience that the victim would “be lost without him,” “would be nothing without him,” heavy things. (Vinicius)

In this context, the separation from friends is revealed as a movement typical of violent dynamics in intimate relationships, a fact that can leave the person more vulnerable and ill:

But that is exactly the damage. When a person begins to give in to this psychological pressure that they suffer, to this emotional blackmail, they move away from other people (. . .) The biggest damage is this, moving away in a somewhat irreversible way. Because the biggest damage is if one day they break up, then he will have the role and now he is the one who will be totally lost, totally dependent on her (girlfriend). I think this is the worst thing that can happen. (Leandro)

The participants highlighted that experiencing violent relationships produces insecurities that, if not understood and taken care of, can reflect on subsequent relationships. These insecurities might give rise to experiences and feelings that impact the mental health of those involved in violent relationships:

The most important thing to say is that people who suffer violence have a tendency, in my opinion, to, if they don’t get help, somehow repeat this in their next relationships. And it becomes a big cycle. One moment you are the abuser, the next you are the abused person. (Allan)

People get that suspicion that if it has already happened once, then it will happen again. This ends up even generating a potential psychological aggressor, where the person becomes so afraid that it can happen again that they end up being more possessive, restricting their partner more. (Vinicius)

Soon after I had another relationship in which I started doing these things. So I did all this and a little more with this other person, out of insecurity, maybe because of things that happened at the beginning of our relationship. . . (Allan)

In the last statements, it is important to highlight the ambivalence present toward IPV. At times, participants identify as either perpetrators or victims, denoting the need for attention for both victims and perpetrators of violence. In this sense, the participants brought up physical or mental illnesses lived by themselves or colleagues when experiencing IPV, such as anorexia, anxiety, losses in studies, guilt, and greater submission in relationships as part of the cycle of violence:

I saw a friend of mine suffer psychological violence from her boyfriend, the kind where he didn’t want her to talk to any of her friends, including me, anymore and made her feel bad. Then she stopped eating, lost weight, had to see a nutritionist. He was completely toxic towards her. (Diego)

Sometimes it creates that feeling of always being alert, you know? It generates a lot of anxiety. The person becomes more insecure, even with themselves, right? “How did this happen?” (Renan)

I feel like a lot of issues concerning the trust I have with people, in meeting new people, or in opening up to people, and also the issue about my appearance, about how I see myself (. . .) also issues about my sexuality. (Victor)

It ended up affecting my routine. So, if I had to hand in some assignment or take a test, I would always be thinking about what had happened. . . (Regis)

The person does not trust anyone anymore, or they start to feel guilty about themselves, and sometimes they will think that this happened because they were to blame, so it’s very sad. The person ends up becoming submissive, because. . . I cannot understand it either. I think there is a lot of psychological loss, mainly. (Otávio)

Finally, the interviewees proposed preventive strategies that promote healthy intimate relationships. Self-knowledge, establishing limits in relationships, peer support, and psychological support were the aspects revealed:

We see ourselves as lost, so we often put the will of others above ourselves, out of fear (. . .) It would be important for us to learn when the limit of acceptable, of respect, is crossed. (Renan)

To deal with it, it is always good to have someone to talk to, someone you trust, several channels (. . .) It is necessary to have these support channels, people close to you to talk to when you may be afraid (. . .) because when you are the victim, it is very difficult for you to find the strength to react. . . (Vinicius)

What I believe is more rational would be dialogue, always. I believe this is the main thing for relationships, reciprocity, and honesty, of course. . . (Leandro)

Professional psychological help (. . .) Because there’s no point in having ideas, wanting to change, wanting to know, but not knowing how to do it without help. (Regis)

The students emphasized the importance of educational practices from childhood through university to prevent and to deal with violence, removing the theme of invisibility. They also brought up the need for support groups for survivors of violence and functioning legislation:

Well, I think the best prevention of violence is for people to be educated about it from a young age (. . .) for people to know what is correct or not within a relationship, how far love goes, in this case, how far it starts to turn into physical, psychological, emotional violence, what the other person is doing to you. (Éder)

I am president of the Academic Center. . . and, well, one thing that I always missed a lot and that I tried to implement in my one year of management was doing a social project, so we could have discussions, more discussions about other topics, you know? And the younger guys came with a more open mind and such. Because, oh man, I think there is no other way, we only get better by talking about it. (Otávio)

(. . .) we have to normalize this type of conversation, in all spaces. I think it would be a very effective way. (Allan)

(. . .) education is cool, but also support groups for adult people who have suffered some type of violence. . . (Danilo)

In Brazil things do not work as they should (. . .) the person reports it, but at the end of the day they go home and the person will be there waiting, and then what? (Caio)

Discussion

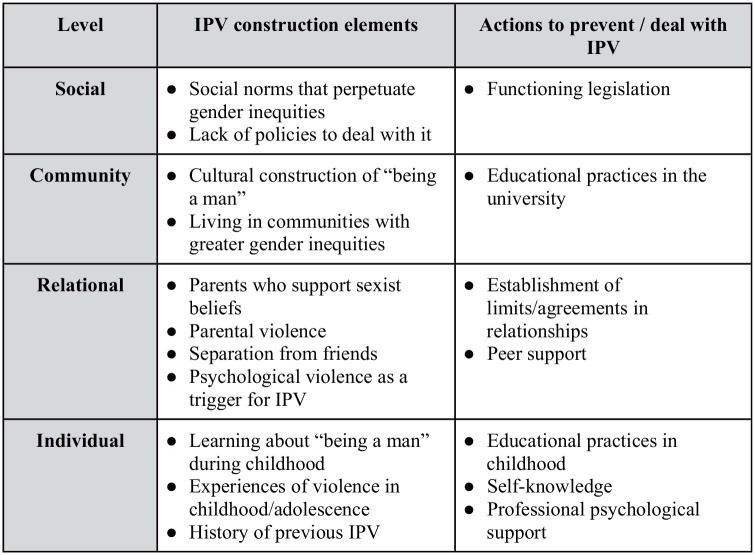

Examining the construction of IPV among young people who identify as male in a developing country has brought some diversity little explored in the scientific literature. It was revealed that this phenomenon is configured as a historical, social, and cultural construction, a phenomenon sustained mainly by what is attributed to “being a man” in society and, consequently, by the actions expected by this attribution. These perceptions are transversal in relationships within society and go beyond generations, in addition to memories of violence experienced or witnessed, which play a significant role in determining IPV experiences. In this sense, due to the naturalization of this process, rooted since childhood, IPV is difficult to be identified by those who live it. The synthesis of the elements pointed out by a population-based study with individuals of the same age as our interviewees who reported IPV for the construction of IPV as well as actions to prevent or to deal with it is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Synthesis of the Elements Pointed Out by the Interviewees for the Construction of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), as Well as Actions to Prevent Or to Deal With It. São Carlos, Brazil, 2023

The ecological model for understanding violence underscores the critical role that social norms around gender play in shaping dating violence. It explains how inequitable gender norms and the normalization of IPV contribute to sustaining violent relationships. The model also highlights how these social constructions are passed down through generations, directly impacting the individual behaviors and relationship dynamics of young people (WHO, 2022). The literature has corroborated these findings. A study carried out interviews with 13 men undergoing criminal prosecution for IPV in Brazil and found that infidelity, overvaluation of work, family provision, imposition of family norms, and detention of power in relation to women were constitutive elements of masculinity taught and learned in childhood and adolescence, in the family environment, and reproduced by these men (Silva et al., 2022).

Still in Brazil, a qualitative study conducted interviews with 12 adolescents of both biological sexes, revealing a relationship between violence and the male gender, which carries with them the feeling of superiority and domination over women (V. P. Souza et al., 2020). For these teenagers, this attitude is the result of a sexist culture, which is historically constructed by society (V. P. Souza et al., 2020). The expectations of the roles of being a man and being a woman in Brazilian society are reinforced by the adolescents in another article (A. P. F. Oliveira et al., 2021), in which interviewees understand that traditional gender norms foster beliefs that men should be in a dominant social position that gives them privileges and power over women.

It is important to highlight that in the country under study, in addition to the socioeconomic issues addressed below that interfere with the construction of sexist beliefs, there is an adverse political scenario. In addition to having experienced an extreme right-wing presidency until 2022—the moment in which this study was carried out—Brazil has been experiencing the growth of power in the bloc called BBB (standing for Bible, Beef, and Bullets), formed by highly conservative and religious fundamentalist politicians. This change has influenced public policies on sexual education and diversity. Some movements have suspended the distribution of educational materials on gender, sexuality, and human rights in public schools. The project “Escola Sem Partido” (“Schools Without Party”) has gained support, aiming to promote an agenda that prohibits discussions on gender identity, sexual education, and political debates. According to them, teachers are supposed to prioritize so-called “family values,” while the topics of sexual and reproductive rights should be discussed at home, in a country where it is known that the majority of sexual violence crimes are perpetrated by family members. Such aspects oppose scientific evidence that has supported the role of health education in basic education schools to combat gender-based violence (Montenegro et al., 2020).

This study demonstrates the possibility that living in contexts where gender inequalities are legitimized, which are generally scenarios of greater social vulnerability, may result in higher possibilities of IPV. In this sense, such results are corroborated by other countries. In Canada, a population-based study with individuals of the same age as our interviewees who reported IPV in the previous 12 months found that experiencing situations of social marginalization, such as poverty, increases the risk of experiencing IPV (Exner-Cortens et al., 2021). Other studies brought a relevant aspect in this sense: witnessing IPV was associated with IPV victimization and perpetration mediated by a greater acceptance of dating violence norms among Mexican American immigrants (Williams & Adams Rueda, 2022). A sample of high school students from the northeastern United States found that peer support for sexual violence and peer endorsement of rape-related myths had a significant contribution in association with the perpetration of dating aggression (Collibee et al., 2021).

For the interviewees, violence appeared as a phenomenon apprehended since childhood (individual and relational level), which goes through generations. This result is corroborated in several locations around the world. A study carried out in Wisconsin, in the United States, looked for parents who had a history of violent and negligent behavior toward their children (Kong et al., 2021). The sample included 727 low-income parents who, when asked about their childhoods and stages of development, reported that they experienced child abuse, neglect, and witnessed domestic violence, and that they currently and frequently used psychological and physical violence and neglect in the upbringing and development of their children (Kong et al., 2021). This study was confirmed by another, which shows that children can reproduce abusive behaviors in their interpersonal relationships in adulthood, based on family models where violence was manifested (Crepaldi & Becker, 2019).

Respecting the diversity included in this study, a transgender participant reported that, when beginning his transition, he drew on his childhood model of masculinity from what he lived with his father, even regarding the reproduction of violence. In a survey in which trans men were interviewed in Brazil and Portugal, the authors found that dominant masculinity continues to bring expressions that are fundamental for the social recognition and legitimization of these men (Soares et al., 2021). Violence can be one of these expressions of masculinity, due to the way it is manifested in society.

Another study demonstrating the transgenerationality of violence was carried out by researchers from the United Kingdom and Poland (Beyene et al., 2020). They interviewed 1,300 adolescents (639 boys and 661 girls) from two eastern Caribbean countries, Barbados and Grenada, to verify the association between exposure to violence throughout life and attitudes related to gender-based violence. It was concluded that there was a greater association between boys with a family history of violence and violent attitudes toward girls (Beyene et al., 2020).

When considering the violence present in relationships, a significant attention is given to cases of physical and sexual violence, as they are more evident and less veiled. However, as revealed in the interviewees’ statements, psychological violence appears before them with subtlety and normalization. Here it is important to highlight the ecological perspective on the phenomenon—the presence of risk factors for IPV at the social and community level has direct interference at the relational and individual level (WHO, 2022), as will be discussed below.

A study in Spain sought to understand the views of 137 students of both genders on the practice and experience of IPV. The study showed that psychological aggression was more prevalent, as it distorts concern and care and transforms them into feelings and attitudes based on possession, control, and emotional dependence (Antón et al., 2020).

Therefore, among the various types of violence, psychological violence is very common, as it is often not perceived, recognized, and treated as violence, as it is seen as a common act within an intimate relationship. A quantitative survey carried out with 224 university students from southern Brazil, using a semi-structured questionnaire on abusive behaviors, revealed the predominance of verbal aggression and marital irritation as the main types of violence among young people (Bobato et al., 2022). Another Brazilian study carried out focus groups with 19 boys and girls between 14 and 27 years old. In addition to psychological violence being the most common, control of the other and the feeling of ownership seem to be understood as indicators of a serious and trusting relationship (A. P. F. Oliveira et al., 2021). Jealousy was considered by those interviewed as a form of affection and there was no perception that, in fact, it contributes to the increase in violent actions (A. P. F. Oliveira et al., 2021), corroborating the findings of our study.

Studies have demonstrated the subtlety with which violence is revealed. Interviews with men undergoing criminal prosecution for IPV found that the domination of men over women is expressed through control of the places they go to, friendships, and cell phone use; that is, violence is revealed in a subtle way (Silva et al., 2020).

In this sense, the separation from peers brought by study participants and present in IPV situations could help in perceiving them, as well as minimizing consequent impacts on mental health. As demonstrated in Gracia-Leiva’s study (Gracia-Leiva et al., 2020), loneliness, lack of perceived care from loved ones, and lack of a sense of belonging increased suicidal thoughts in IPV victims. Furthermore, statistical models indicated that being closer to peers reduces the impact of IPV on the risk of suicidal behavior (Gracia-Leiva et al., 2020). Such aspects were revealed as relevant in this study, with separation from peers being identified as elements of risk at the relational level and the support of these peers being referenced as a strategy for preventing/dealing with IPV.

We highlight that, at the individual level of the ecological framework, we found the so-called insecurity as an important factor. This feeling is the result of the experience with violent relationships (whether in their own relationships or witnessed in childhood and adolescence), which can lead to the internalization and repetition of violent behavior. The interviewees indicated that the individual can sometimes be a victim, and sometimes a perpetrator. In a literature review that sought to verify the violence suffered by men, it was found that the majority of men affected by violence were also violent toward their partners (Kolbe & Büttner, 2020). The negative consequences of violence that affect young people in Brazilian society are worrying, and cases of homicide are becoming increasingly common (R. N. G. Oliveira & Fonseca, 2019), being more frequent between the ages of 15 and 29, when these individuals are in full productive capacity both in professional and in personal life (Cerqueira, 2021).

Finally, strategies to prevent IPV and promote healthy intimate relationships were proposed. A survey of 1,200 men and women from rural areas of Bangladesh revealed that younger, single men have more egalitarian gender beliefs and attitudes, highlighting that masculinity norms acquired throughout life can change due to factors such as life experience, social environment, and media influence, among others. Therefore, it is essential to carry out interventions, especially to provide guidance to younger men with the aim of preventing gender-based violence in adulthood (Fattah & Camellia, 2020). Such actions can be part of interprofessional actions, especially in education and health. The Health in School Program, an important initiative in the Brazilian context that aligns with Health Promoting Schools, seeks to contribute to the comprehensive education of students and the promotion of a culture of peace, citizenship, and human rights (Brasil, 2007). In this sense, it must encompass actions that respond to current demands, such as IPV prevention in early adolescence, which has been indicated by the literature as an opportune period (M. S. Souza et al., 2021).

Preventive interventions can help young people to problematize violent norms in relationships and deal with violence experienced in their homes, among their peers, and communities (Collibee et al., 2021; Williams & Adams Rueda, 2022). A meta-analysis systematized the available evidence on risk and protective factors for sexual violence perpetrated by men in higher education institutions. Previous history of perpetrating sexual violence was the strongest predictor of new perpetration of violence. A study suggests interventions aimed at problematizing violent norms among peers, such as interventions for spectators of violence, and comprehensive education for early sexuality, as well as interventions on consent in primary and secondary schools (Steele et al., 2022). In this context, leading participants in a peer-based program to prevent IPV revealed a lasting effect on their relationships, identity formation, and professional lives. They brought up skills to avoid unhealthy relationships and to help friends and family in this regard (Johnson et al., 2022).

This research has limitations. First, the method used to recruit participants privileged those with access to social networks. The study also did not consider particularities that could mean singularities—differences in gender identity, experiences in intimate relationships, and geographic location. Furthermore, there was no participation of non-White people, except for one who declared himself Brown. New studies that explore such singularities, as well as delve deeper into the experience of psychological violence and ways to prevent and deal with it, are recommended.

Despite the limitations, the study has implications for professional practice, in particular the need to understand the views on IPV from the perspective of people who identify as male in a developing country. In this sense, it brings some elements that should make up actions, especially within the scope of communities and schools, together with Primary Health Care, such as the deconstruction of traditional gender norms, the perception of violent relationships, the need to build support networks for those involved in them, and the expanded discussion of IPV in the academic environment.

Final Considerations

This study allowed us to conclude that the violence affecting the intimacy of young people, from the perspective of those who identify as male, is based on the construction of concepts and thoughts that were acquired throughout life, within society and in the family environment in which they live. The construction of “being a man” brings the normalization of violent behaviors, essentially based on traditional gender norms with transgenerational maintenance. Living in communities that legitimize gender inequities, generally in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, has a prominent place as an element for building IPV among the population studied.

The violence experienced can lead to significant psychological impairments for everyone involved in it, reinforcing its relevance as a public health issue. In this context, psychological violence emerges as preponderant and triggers other forms of violence, veiled behind prejudices and difficult to notice. Educational practices for healthy relationships are proposed and emphasized from basic to higher education, in addition to peer and professional support.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, grant #233534/2014-8) and Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES, Finance Code 001).

Ethical Statement: The research meets ethical guidelines, and approval was provided by the institutional review board.

ORCID iD: Diene Monique Carlos  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4950-7350

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4950-7350

References

- Antón M. J. G., Aribas-Rey A., Miguel J. M., Garcia-Collantes A. (2020). Violence in the relationships of young couples: Prevalence, victimization, perpetration and bidirectionality. LogosCyT, 12(2), 8–19. 10.22335/rlct.v12i2.1168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beyene A. S., Chojenta C., Loxton D. J. (2020). Gender-based violence perpetration by male high school students in Eastern Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 5536. 10.3390/ijerph17155536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobato S. T., Alves B., Becker A. P. S. (2022). Violence in the love relationships of university students. Psicologia Argumento, 39(107), 1199–1219. 10.7213/psicolargum.39.107.AO10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. (2007, December 5). Decree n. 6,286, of December 5, 2007. Establishes the School Health Program (PSE) and provides additional measures (p. 2). Diário Oficial da União. [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira D. (2021). Atlas of violence 2021. Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública /Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada / Instituto Jones dos Santos Neves. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke V., Braun V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collibee C., Rizzo C., Bleiweiss K., Orchowski L. M. (2021). The influence of peer support for violence and peer acceptance of rape myths on multiple forms of interpersonal violence among youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15–16), 7185–7201. 10.1177/0886260519832925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaldi M. A., Becker P. S. (2019). The attachment developed in childhood and the conjugal and parental relationship: A review of the literature. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, 19(1), 238–260. [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D., Baker E., Craig W. (2021). The National Prevalence of Adolescent dating violence in Canada. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(3), 495–502. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattah K. N., Camellia S. (2020). Gender norms and beliefs, and men’s violence against women in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(3–4), 771–793. 10.1177/0886260517690875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick U. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Leiva M., Puente-Martínez A., Ubillos-Landa S., González-Castro J. L., Páez-Rovira D. (2020). Off- and online heterosexual dating violence, perceived attachment to parents and peers and suicide risk in young women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3174. 10.3390/ijerph17093174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grest C. V., Cederbaum J. A., Lee D. S., Choi Y. J., Cho H., Hong S., Yun S. H., Lee J. O. (2022). Cumulative violence exposure and alcohol use among college students: Adverse childhood experiences and dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(1–2), 557–577. 10.1177/0886260520913212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink M., Kaiser B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. P., Sundaram M. A., Alder J., Miller E., Ragavan M. I. (2022). The lasting influence of a peer-led adolescent relationship abuse prevention program on former peer leaders’ relationships, identities, and trajectories in emerging adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9–10), NP7580–NP7604. 10.1177/0886260520967909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe V., Büttner A. (2020). Domestic violence against men-prevalence and risk factors. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 117(31–32), 534–541. 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J., Lee H., Slack K. S., Lee E. (2021). The moderating role of three-generation households in the intergenerational transmission of violence. Child Abuse and Neglect, 117, 105117. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minayo C. S. (2014). The challenge of knowledge: qualitative research in health. HUCITEC. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro L., Velasque L., LeGrand S., Whetten K., Rafael R. M. R., Malta M. (2020). Public health, HIV care and prevention, human rights and democracy at a crossroad in Brazil. AIDS and Behavior, 24, 1–4. 10.1007/s10461-019-02470-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento C. O., Costa M. C. O., Costa A. M., Cunha B. S. G. (2018). Violent love path and mental health in adolescent - young: Integrative literature review. Revista de Saúde Coletiva da UEFS, 8, 30–38. 10.13102/rscdauefs.v8i1.3505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira A. P. F., Silva A. M. C., Campeiz A. B., Oliveira W. A., Silva M. A. I., Carlos D. M. (2021). Dating violence among adolescents from a region of high social vulnerability. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 29, e3499. 10.1590/1518-8345.5353.3499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira R. N. G., Fonseca R. M. G. S. (2019). Love and violence at play: Revealing the affective-sexual relations between young people using the gender lens. Interface Comunicação, Saúde e Educação, 23(1), 1–16. 10.1590/Interface.180354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saffioti I. B. (2015). Gender, patriarchy, violence. Expressão Popular, Fundação Perseu Abramo. [Google Scholar]

- Silva A. F., Estrela M., Magalhães R. F., Gomes N. P., Pereira A., Carneiro J. B., Cruz M. A., Costa M. S. G. (2022). Constituent elements of masculinity taught/learned in childhood and adolescence of men who are being criminally prosecuted of violence agains women/partners. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, 27(06), 2123–2131. 10.1590/1413-81232022276.18412021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A. F., Gomes N. P., Pereira A., Magalhães R. F., Estrela F. M., Sousa A. R., Carneiro J. B. (2020). Social attributes of the male that incite the violence by intimate partner. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73(6), e20190470. 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares M., Moreira C., Rodrigues L., Nogueira C. (2021). (De)construction of masculinities of trans men, between Portugal and Brazil. Ex æquo, 43, 113–129. 10.22355/exaequo.2021.43.08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza M. S., Silva S. M. C., Komatsu A. V., Gonçalves M. S., Salim N. R., Carlos D. M. (2021). Preventing violence and promoting healthy intimate relationships: Interventional analysis with adolescents. Research, Society and Development, 10(16), e551101624075. 10.33448/rsd-v10i16.24075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza V. P., Gusmão L. A., Frazão R. S. B., Guedes T. G., Monteiro E. M. L. M. (2020). Protagonism of adolescents in planning actions to prevent sexual violence. Texto & Contexto Enfermagem, 29, e20180481. 10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2018-0481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steele B., Martin M., Yakubovich A., Humphreys D. K., Nye E. (2022). Risk and protective factors for men’s sexual violence against women at higher education institutions: A systematic and meta-analytic review of the longitudinal evidence. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 23(3), 716–732. 10.1177/1524838020970900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taquette S. R., Monteiro D. L. M. (2019). Causes and consequences of adolescent dating violence: A systematic review. Journal of Injury and Violence Research, 11(2), 137–147. 10.5249/jivr.v11i2.1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska P., Schuster I. (2021). Prevalence of teen dating violence in Europe: A systematic review of studies since 2010. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 178, 11–37. 10.1002/cad.20437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. R., Adams Rueda H. (2022). Witnessing Intimate Partner Violence across contexts: Mental health, delinquency, and dating violence outcomes among Mexican heritage youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5–6), NP3152–NP3174. 10.1177/0886260520946818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincentak K., Connolly J., Card N. (2017). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 224–241. 10.1037/a0040194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Violence Prevention Alliance (VPA): Definition and typology of violence. [Google Scholar]