Abstract

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease has a significantly worse prognosis than idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. According to a case series from France, the median survival time from diagnosis to death or lung transplantation was only 1 year, and in a more recent analysis, pulmonary arterial hypertension therapy had no significant effect on survival. There are case reports and case series describing both beneficial and adverse effects of pulmonary arterial hypertension-related medications. The most life-threatening complication of such a therapy is pulmonary oedema. In the long term, lung transplantation remains the best treatment option for suitable patients. However, elderly patients with concomitant or precipitating malignant disease are not considered transplant candidates. We describe a 59-year-old pulmonary veno-occlusive disease patient with multiple myeloma in World Health Organisation functional class IV who was successfully treated with sildenafil for almost 5 years.

Keywords: Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, sildenafil citrate, multiple myeloma, melphalan

Introduction

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) has a significantly worse prognosis than idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). According to a case series from France, the median survival time from diagnosis to death or lung transplantation was only 1 year, 1 and in a more recent analysis, PAH therapy had no significant effect on survival. 2 There are case reports and case series describing both beneficial and adverse effects of PAH-related medications. The most life-threatening complication of such therapy is pulmonary oedema. In the long term, lung transplantation remains the best treatment option for suitable patients. However, elderly patients with concomitant or precipitating malignant disease are not considered transplant candidates. We describe a 59-year-old PVOD patient with multiple myeloma (MM) in World Health Organisation functional class (WHO-FC) IV who was successfully treated with sildenafil for almost 5 years.

Case report

A 59-year-old woman complained of dyspnoea on exertion, which had been gradually increasing for several years but worsened 8 months before admission to our department. Five months before her admission, she was diagnosed with stage IIIa IgG-MM and received three cycles of melphalan and prednisolone. One month later, she was referred to our clinic for evaluation and treatment of pulmonary hypertension (PH) after an echocardiogram revealed a systolic pulmonary arterial pressure of 85 mmHg, a dilated right atrium and ventricle, a small left atrium and left ventricle with normal systolic function, and a small pericardial effusion.

Her past medical history included Guillain–Barré syndrome dating back 12 years, long-standing arterial hypertension and reactive depression. She was a never-smoker. Her cardiovascular medication included carvedilol and amlodipine.

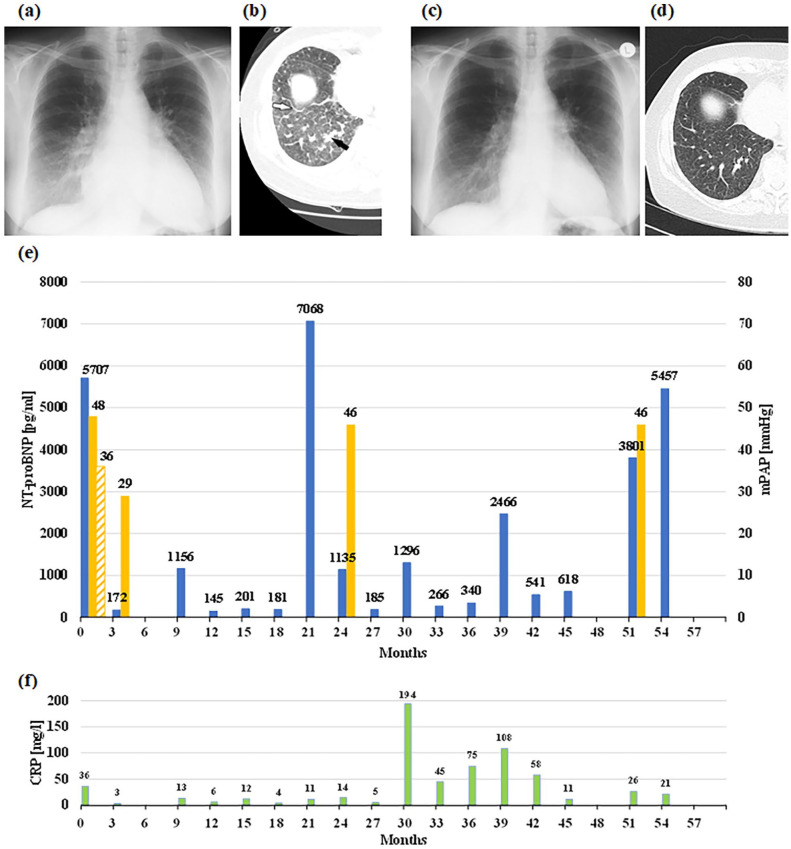

The patient presented with weakness and dyspnoea on minimal exertion, WHO-FC IV. She had a normal body temperature and systemic blood pressure, but central cyanosis. Auscultation of lungs and heart was normal except for a loud second heart sound. There was no peripheral oedema. Pulmonary function testing revealed mild restrictive ventilatory dysfunction, arterial blood gases showed severe hypoxaemia (Table 1). The ECG showed a sinus rhythm with signs of right ventricular overload. Right heart catheterisation (RHC) confirmed severe PH with a remarkable acute vasodilator response to sildenafil (Table 1 and Figure 1(e)) without adverse effects. Diffusion capacity assessment and 6-minute walk test 3 were not possible due to weakness. Chest radiographs and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) are shown in the figure. HRCT showed enlarged lymph nodes, thickened interlobular septal lines in the basal lung areas (Figure 1(b)), sparse centrilobular ground-glass opacities and a region of consolidation due to confluent interstitial oedema. Pulmonary embolism and other diseases associated with PH were systematically excluded. The N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was highly elevated (Figure 1(e)). Creatinine, leucocytes and C-reactive protein were in the normal range. Pathological laboratory findings were mild anaemia (Hb 10.5 g/dL), a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate and paraproteinaemia with an M-component in the electrophoresis.

Table 1.

Right heart catheter and functional characteristics over 4.5 years after diagnosis of PVOD.

| Baseline | Acute testing a | 3 months | 2 years | 4.5 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention+O2 L/min | 0 | Sil+2L | Sil+0 | Sil+1.5L | Sil+Bos+3L |

| mSAP, mmHg | 102 | 92 | 86 | 96 | 79 |

| mPAP, mmHg | 48 | 36 | 29 | 46 | 46 |

| PAWP, mmHg | 11 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| RAP, mmHg | 7 | 3 | 1 | −1 | 2 |

| CO, L/min | 4.5 | 5.1 | 4.02 | 3.96 | 4.24 |

| PVR, WU | 8.43 | 5.66 | 5.98 | 10.86 | 10.14 |

| SaO2, % | 90 | 92 | 95 | 95.2 | 94.5 |

| SvO2, % | 45 | 59 | 68.4 | 64 | 66.6 |

| PaO2, mmHg | 54.6 | 68 | 70.2 | 64.6 | |

| DLCO/VA, % predicted | NA | 62.4 | NA | NA | |

| WHO-FC | IV | II | IV | ||

| 6-MWD, m | NA | 327 | NA b | NA b |

mSAP: mean systemic arterial pressure; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PAWP: pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; RAP: right atrial pressure; CO: cardiac output; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; WU: Wood Units; SaO2: arterial oxygen saturation; SvO2: mixed venous (pulmonary arterial) oxygen saturation; PaO2: partial pressure of arterial oxygen; DLCO/VA: diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide/alveolar volume; WHO-FC: World Health Organisation functional class; 6-MWD: 6-minute walk distance; NA: not available; PVOD: pulmonary veno-occlusive disease.

At baseline, the patient did not receive any vasoactive medication or oxygen.

Acute examination 30 min after 50 mg sildenafil with nasal oxygen (2 L/min); follow-up examination after 3 months and 2 years under continuous therapy with sildenafil 50 mg BID and oxygen (0 or 1.5 L/min) and after 4.5 years with sildenafil 50 mg BID, bosentan 125 mg BID and oxygen (3 L/min).

Due to paraplegia.

Figure 1.

Imaging, hemodynamics, NT-proBNP and CRP before and after start of sildenafil, reflecting the patient`s clinical course over 4.5 years. The deterioration at month 21 was due to a cessation of diuretics. Bosentan was added after right-heart catheterisation at month 24. (a) Chest X-ray at baseline with enlarged heart silhouette due to right heart dilatation, dilated proximal pulmonary arteries, and peripheral interstitial markings, such as Kerley-B lines. (b) Corresponding high-resolution chest CT showing a right basal view with thickened interlobular septal lines (white arrow), centrilobular ground-glass opacities and a consolidation area due to interstitial oedema (black arrow). Furthermore, there was a small bilateral pleural effusion. (c) Chest X-ray after treatment with diuretics and sildenafil reveals decrease in heart size and marked improvement of the interstitial markings, which are also apparent from the chest CT (d). (e) Course of NT-proBNP levels (blue columns), meanPAP during RHC measurements (yellow columns). The shaded yellow column depicts meanPAP during acute testing with sildenafil. (f) Impact of infections is reflected by increased CRP levels (green columns).

CT: computed tomography; RHC: right heart catheterisation; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; CRP: C-reactive protein; PAP: pulmonary arterial pressure.

Administration of furosemide and spironolacton was started before baseline RHC and resulted in a moderate improvement in clinical findings. After RHC, we started therapy with sildenafil 50 mg BID. Dyspnoea improved within a few days. After 3 months, the clinical improvement was impressive, including radiological findings and haemodynamics. The patient was able to complete the 6-minute walk test again, hypoxaemia and NT-proBNP were significantly improved (Table 1 and Figure 1(e)). She then developed generalised paralysis (recurrent Guillain–Barré syndrome) following an enteral infection, which also affected the respiratory muscles and required mechanical ventilation for 5 weeks. The paralysis then improved, except in the lower limbs. From then on, the patient was confined to a wheelchair. Her cardiopulmonary condition recovered and the NT-proBNP decreased continuously (Figure 1(e)). Twelve months after starting sildenafil treatment, there were no signs of right-heart decompensation, and the patient did not require oxygen for another 9 months. According to her haematologists, there was no indication for specific MM therapy. When the patient arbitrarily stopped the diuretics, the symptoms worsened with a significant increase in NT-proBNP (month 21). The resumption of diuretic therapy improved the symptoms without reaching the previous clinical status. A re-evaluation by RHC (Table 1), 24 months after the start of sildenafil treatment, confirmed haemodynamic deterioration, and we added bosentan as oral combination therapy. Again, respiratory symptoms improved significantly, chest X-ray showed an improvement in heart size and NT-proBNP decreased (Figure 1(e)). In the following year, the cardiorespiratory situation was stable, although respiratory infections led to a deterioration with a temporary increase in NT-proBNP (Figure 1(e) and (f)). In the second year of combination therapy, a sacral ulcer developed due to paraplegia. In addition, increasing anaemia and infections, some of unknown origin, necessitated repeated blood transfusions and antibiotics. Although the general condition deteriorated again, there were no clinical signs of right-heart decompensation, and also the RHC performed at month 51 after initiation of PAH-targeted medication did not indicate right-heart decompensation (Table 1). Therefore, therapy was continued with sildenafil, bosentan, and oral diuretics. Fifty-seven months after initiation of PAH-targeted therapy, the patient died of sepsis.

Discussion

In contrast to idiopathic PAH, in which the distal pulmonary arteries are affected, PVOD primarily affects the small postcapillary vessels (preseptal venules, septal veins) but the pulmonary capillaries and the precapillary vessels are also heavily affected. Although postcapillary fibro-proliferative remodelling is often the predominant pathological feature of the disease, 4 vasodilator drugs have been used because they show a significant vasodilator response. 5 However, vasodilator treatment that leads to a reduction in precapillary but not postcapillary resistance increases pulmonary capillary pressure and may cause interstitial and even alveolar pulmonary oedema.

In our patient, we made the diagnosis of PVOD based on chest X-ray, showing a dilated heart with Kerley-B lines, echocardiography, showing PH with a small left atrium and ventricle, and HRCT 6 showing some typical findings like enlarged lymph nodes, ground-glass opacities and dilated septal lines in the basal parts of the lung in conjunction with RHC results and a disproportionately low partial pressure of arterial oxygen as described in the literature. 1 Biopsies or bronchoalveolar lavage are not recommended for safety reasons, although they may provide important diagnostic features of PVOD like abundant iron-loaded macrophages. 7 Genetic testing is established and identifies most hereditary PVOD cases; however, EIF2AK4 mutations are very rare in older PVOD patients. 8 Our patient had been suffering from dyspnoea for a long time, but PVOD was only diagnosed after chemotherapy. Therefore, it is possible that the chemotherapy with melphalan may have contributed to the disease. Chemotherapy-associated PVOD has been described in the literature, and the molecular mechanisms may be associated not only with alkylating agents but also with other cancer therapies including radiotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. 9

After diuretic therapy, we performed a RHC examination and found severe PH with normal pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP). This is typical of PVOD, as the elevated pulmonary capillary pressures are not visible in the PAWP readings and reflect the mean left atrial pressure. 10 For safety reasons, we administered a dose of sildenafil as a pharmacological test during the RHC, although this is not recommended in the current ESC/ERS guidelines. 11 According to long-term experience with non-PAH PH patients, the reasons for performing such a test in our centre are occasional patients who show a hypotensive response or develop transient hypoxaemia after a single dose of sildenafil, while the majority of patients only show a decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). This acute response pattern may help guide treatment decisions, keeping in mind the ‘no harm’ mandate. 12 Our patient showed a relatively strong vasodilator response with a 33% decrease in PVR with no acute adverse effects. On this basis, we started regular sildenafil therapy, which led to an impressive improvement in symptoms, functional findings, exercise capacity and haemodynamics without signs of pulmonary oedema. Radiological changes indicated decreased capillary pressure, suggesting reduced postcapillary resistance.

The pre- and post-capillary resistance of the pulmonary vasculature is controlled by pulmonary arterial and pulmonary venous tone. In the case of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, both pre- and post-capillary tone increase in parallel. 13 However, the different responses to vasoactive substances and pharmacological agents are poorly understood. Using precision-cut lung slices, Rieg et al. demonstrated a much stronger vasoactive response in the pulmonary veins than in the pulmonary arteries in guinea pigs. 14 By far the strongest vasodilatory effect on venous tone was obtained with nitric oxide (NO). This suggests that postcapillary tone is highly dependent on NO signalling, which may explain why sildenafil, which enhances the effect of NO, has a strong relaxing effect on postcapillary pulmonary tone and prevents a large increase in pulmonary capillary pressure.

MM and Guillain–Barré syndrome with its sequelae were important comorbidities for our patient. Melphalan therapy may have contributed to the manifestation of PVOD, but this would be the first report of a causal relationship. Temporary worsening of cardiopulmonary status occurred during periods of infection (Figure 1(e) and (f)). Nevertheless, the survival time was remarkably long, considering that the patient had initially presented more or less bedridden in WHO-FC IV. We are convinced that sildenafil played a key role in the short-term and long-term stabilisation of this patient.

Our case is reminiscent of a patient with mitomycin-induced PVOD who improved significantly after bosentan therapy. 15 There are several reports of beneficial effects of sildenafil in mono, dual, or multiple combination therapy with various PAH drugs, but most of them involved less than 4 years of follow-up. 16 Nakamura et al. 17 reported a retrospective analysis of PVOD/PCH patients treated with oral pulmonary vasodilators as monotherapy or combination therapy and found a remarkable median survival of 3.9 years. The most commonly used drugs were phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. In comparison, the most commonly used drugs in the French registry were endothelin receptor antagonists 2, and no significant effect on survival was observed. Imatinib is not approved for PAH but has been used successfully in PVOD, 18 suggesting that the Platelet-derived growth factor receptor may be involved in postcapillary pathology. Montani et al. reported severe pulmonary oedema associated with PAH therapy, 19 which is consistent with previous reports. 20

Our case shows that sildenafil in PVOD in combination with chemotherapy for MM can have impressive haemodynamic and clinical effects and that patients can benefit from such therapy for a long time. It should be noted that vasodilator therapy should always be used with great caution in PVOD, even if first-line monotherapy has not been complicated by pulmonary oedema, which can occur with combination therapy. Lower doses of vasodilators may be preferable.

Conclusion

Sildenafil may be an option for the treatment of severe PVOD with decompensated right heart function after diuretic therapy has been established. Sildenafil in combination with diuretics, cautious dose adjustment, and careful monitoring may be suitable options for the treatment of PVOD. Such a therapy should be reserved for experienced PH centres.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christopher Gradwohl for providing technical help in preparing the Diagrams and Artwork.

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.H. contributed by patient care and drafting and editing the manuscript. G.K., S.S. and H.O. contributed by patient care and editing the manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorised representative for anonymised patient information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Christian Hesse  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-4871-9169

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-4871-9169

References

- 1. Montani D, Achouh L, Dorfmuller P, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: clinical, functional, radiologic, and hemodynamic characteristics and outcome of 24 cases confirmed by histology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008; 87: 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boucly A, Solinas S, Beurnier A, et al. Outcomes and risk assessment in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. ERJ Open Res 2024; 10: 20240115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166: 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dorfmuller P, Humbert M, Perros F, et al. Fibrous remodeling of the pulmonary venous system in pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue diseases. Hum Pathol 2007; 38: 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palevsky HI, Pietra GG, Fishman AP. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and its response to vasodilator agents. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 142: 426–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Resten A, Maitre S, Humbert M, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: CT of the chest in pulmonary venoocclusive disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rabiller A, Jais X, Hamid A, et al. Occult alveolar haemorrhage in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2006; 27: 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Girerd B, Montani D, Jais X, et al. Genetic counselling in a national referral centre for pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ranchoux B, Gunther S, Quarck R, et al. Chemotherapy-induced pulmonary hypertension: role of alkylating agents. Am J Pathol 2015; 185: 356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montani D, Lau EM, Dorfmüller P, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 1518–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2023; 61: 20230106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moser KM. Idiopathic pulmonary hypertension: therapeutic opportunities and pitfalls. JAMA 1982; 247: 3119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weissmann N, Grimminger F, Walmrath D, et al. Hypoxic vasoconstriction in buffer-perfused rabbit lungs. Respir Physiol 1995; 100: 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rieg AD, Rossaint R, Uhlig S, et al. Cardiovascular agents affect the tone of pulmonary arteries and veins in precision-cut lung slices. PLoS One 2011; 6: e29698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Botros L, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Vonk NA, et al. Recovery from mitomycin-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11: 468–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ogawa A, Sakao S, Tanabe N, et al. Use of vasodilators for the treatment of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis: a systematic review. Respir Investig 2019; 57: 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakamura J, Tsujino I, Shima H, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral pulmonary vasodilators in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Pulm Circ 2022; 12: e12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakamura J, Tsujino I, Shima H, et al. Clinical and hemodynamic responses to imatinib in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease/pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis: a retrospective pilot study of five cases and review of the literature. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2023; 23: 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Montani D, Girerd B, Jaïs X, et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcomes of heritable and sporadic pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: a population-based study. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mandel J, Mark EJ, Hales CA. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162: 1964–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]