Abstract

Introduction:

To investigate the clinical characteristics in patients without traditional risk factors (TRFs) after transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke, who were recruited in the TIAregistry.org.

Patients and methods:

A total of 3847 patients were analyzed. TRFs included hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, current smoking, and atrial fibrillation. Background characteristics and outcomes at 1 and 5 years in patients without TRFs were compared to those in patients with TRFs. The primary outcome was major cardiovascular event (MACE), which was non-fatal stroke, non-fatal acute coronary syndrome, or vascular death. To evaluate the causes, we applied the ASCOD (atherosclerosis, small vessel disease, cardiac pathology, other causes or dissection) grading system.

Results:

One-year risk of MACE (5.3% vs 6.3%, hazard ratio (HR) 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.53–1.31) was comparable between patients without TRFs (n = 402) and those with TRFs (n = 3445). Five-year risk of MACE was significantly lower in patients without TRFs than in those with TRFs (7.9% vs 13.9%, HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39–0.82). In patients without TRFs, causal atherosclerosis was a potent risk factor (HR 5.67, 95% CI 2.68–12.02) and ipsilateral extra- or intra-cranial arterial stenosis was only significant predictor of MACE (interaction p = 0.0046) at 5 years.

Conclusion and discussion:

The 5-year risk of MACE was lower in patients without TRFs than those with TRFs, although a certain level of risk persisted in the absence of TRFs. The most significant predictor of MACE in patients without TRFs was arterial stenosis.

Keywords: Transient ischemic attack, stroke, prevention, risk factor, arterial stenosis

Graphical abstract.

Introduction

It is well recognized that the risk of recurrent stroke and vascular events is high in patients with traditional risk factors (TRFs) such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and atrial fibrillation after transient ischemic attack (TIA) or minor ischemic stroke (IS).1,2 On the other hand, risk of recurrent stroke and vascular events has not well been studied in patients without TRFs.3,4

Risk of recurrent stroke and vascular events in patients without TRFs after TIA or minor IS might be elevated because of the lack of TRF-specific managements after stroke. 3 In addition, the early risk of TIA patients without TRFs must be underestimated by ABCD 2 score since these TRFs are included in the score, and they may not receive adequate management to prevent recurrent stroke during an early period after TIA. 5 Therefore, it is important to understand potential factors and underlying causes explaining the residual risk of recurrent stroke and major vascular events in patients without TRFs after TIA or minor IS.6–8

This was a subgroup analysis of TIAregistry.org, an international, multicenter, cooperative registry in patients with TIA or minor IS. The purpose of this study was to investigate clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients without TRFs in comparison with those with TRFs.

Methods

Study design

We analyzed data of 3847 patients enrolled in the TIAregistry.org, which was an international, prospective, observational registry of patients with a recent (within the previous 7 days) TIA or minor IS from 61 specialized centers across 21 countries in Europe, Asia, Middle East, and Latin America.9,10 The protocol of the TIAregistry.org was approved by local institutional review boards. The methods of patient recruitment and evaluation for TIAregistry.org have been described previously.9,10

Participants

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the TIAregistry.org if they were aged 18 years or older, had been evaluated by stroke specialists between June 1, 2009 and Dec 29, 2011, and had been followed up for 5 years.9,10 Eligible patients also had to have either TIA or minor IS with a modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 0–1 (0 defined as no symptoms, 1 as no disability, and 6 as death) when first evaluated by a stroke specialist.

Procedures

Stroke specialists prospectively collected patient data, using a standardized web-based case report form, during face-to-face interviews at the time of evaluation of the qualifying event (baseline), at 1, 3, and 12 months after baseline, and every 12 months thereafter for 5 years.9,10 Patients were evaluated at baseline for clinical symptoms during the qualifying event, medical history, physical examination, investigations as recommended by stroke specialists (including brain, and intra- and extra-cranial arteries imaging and cardiac investigations), management (medical treatment and revascularization), occurrence of clinical events after the qualifying event, and mRS score. Patients were evaluated at follow-up for clinical events, medical treatment, and major risk factors. Any clinical event after the qualifying event (i.e. after the patient first sought medical attention), even if the event occurred before evaluation by a stroke specialist, was regarded as an outcome event, as judged by the individual investigators.9,10

TRFs were defined as hypertension (>140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive drugs), diabetes (HbA1c >7.0% or use of glucose-lowering drugs), hypercholesterolemia (low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol >140 mg/dl or use of statins), current cigarette smoking, and documented atrial fibrillation. 9 We did not include healthy diet, sleep disturbance and psychosocial stress because they were lacking in the database collection, and physical activity, because we concentrated on TRFs that are currently and systematically managed by stroke specialists.

The primary outcome was major cardiovascular event (MACE), which was defined as the first event of non-fatal stroke, non-fatal acute coronary syndrome, or vascular death, and the secondary outcome was any death, stroke, TIA, intracranial hemorrhage, or major bleeding.9,10

All elements necessary to grade patients using the ASCOD criteria were captured in the electronic case report form. 11 In ASCOD, every patient should be graded into 5 predefined phenotypes: A (atherosclerosis); S (small-vessel disease); C (cardiac pathology); O (other cause); and D (dissection), and three degrees of causality between the index ischemic stroke and each category are considered: 1 if the disease is present and can potentially be a cause; 2 the disease is present, but the causal link is uncertain; 3 the disease is present but the causal link is unlikely; 0 if the disease is absent; 9 if the workup is insufficient to grade the disease. In addition to the ASCOD grading, we evaluated the absence or presence of ipsilateral 50% or more intracranial or extracranial arterial stenosis.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as means (±standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) in case of non-normal distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentage). Baseline characteristics and medication use at discharge and at 1 and 5 years were compared between patients with and without TRFs. Analysis of covariance was used for quantitative variables, logistic regression models for binary variables, and multinomial regression models for ⩾3 levels categorical variables.

The 5-year event rates were compared between the two study groups using the Cox proportional hazards regression model, including age, sex, mRS, and ABCD 2 score as pre-specified covariates. Cumulative incidence event curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method. We further assessed the association of ABCD 2 score, acute infarctions identified on brain imaging, and probable causes of initial TIA or minor stroke according to the ASCOD grading system with stroke recurrence and vascular events using Cox proportional-hazards model in the two study groups separately. The proportional-hazards assumptions were assessed using the Schoenfeld residuals plots.

Finally, we assessed the independent predictors of primary outcomes in patients without TRFs in Cox proportional-hazards regression models adjusted for age-, sex- and mRS. Candidate predictors were as follows: geographic region, time from symptom onset, TOAST classification, brain infarctions, ABCD 2 score, and ipsilateral 50% or more intracranial or extracranial arterial stenosis. Predictors associated at p-value <0.10 were further investigated into stepwise-backward multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

Five-year rates of recurrent stroke and MACE were estimated and compared according to ASCOD A1/A2 and ASCOD A0/A3/A9 by using Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. In all analyses, patients lost to follow-up at 5 years were treated as censored cases based on the last follow-up available and events that occurred after the 5-year follow-up period were not included in this analysis.

Statistical testing was performed at a two-tailed α level of 0.05. Data were analyzed using SAS software package, release 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 3847 patients were included in this study. The cumulative follow-up in person years was 17,190. The numbers of patients with MACE in no-TRF and TRF patients at 1 year were 21 and 214, respectively. At 5 years, 30 and 439 patients without and with TRFs had an event, respectively. Three thousand six hundred thirty-eight patients had follow-up completion at 1 year and three thousand one hundred seventy-four patients completed the 5 years follow-up. Four hundred forty-nine patients died during follow-up. The median was 5 (inter quartile range; 10) days from index event to enrollment.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics in patients without and with TRFs after TIA or minor IS. Age was younger, female was predominant, and physical activity was more common in patients without TRFs, while regular alcohol drinking, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease were fewer in patients without TRFs. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, LDL cholesterol, triglyceride, and body mass index were lower, while high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was higher in patients without TRFs.

Table 1.

Background characteristics at baseline in patients without and with traditional risk factors.

| Variables | Patients without TRFs n = 402 (10.4%) | Patients with TRFs n = 3445 (89.6%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 59.1 (16.7) | 67.3 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.0350 | ||

| Male | 220/401 (54.9) | 2075/3440 (60.3) | |

| Female | 181/401 (45.1) | 1365/3440 (39.7) | |

| Regular alcohol drinking, n (%) | 60/391 (15.4) | 738/3410 (21.6) | 0.0038 |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 111/381 (29.1) | 690/3331 (20.7) | 0.0002 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 12/398 (3.0) | 469/3435 (13.7) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 6/397 (1.5) | 107/3422 (3.1) | 0.0722 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 41/320 (12.8) | 699/2895 (24.2) | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 0/402 (0.0) | 109/3437 (3.2) | – |

| NIHSS, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 323 (80.3) | 2467 (71.6) | |

| 1–4 | 37 (9.2) | 627 (18.2) | |

| ⩾5 | 2 (0.050) | 20 (5.80) | |

| ASCOD, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| A1/A2 | 48 (11.9) | 950 (27.6) | |

| Other | 354 (88.1) | 2495 (72.4) | |

| Systolic BP, mean (SD), mmHg | 132 (17) | 148 (24) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP, mean (SD), mmHg | 75 (9) | 82 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Plasma glucose, median (IQR), mg/dl | 97 (88–110) | 105 (92–131) | 0.38 |

| HbA1c, median (IQR), % | 5.4 (5.2–5.8) | 5.7 (5.4–6.3) | <0.0001 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dl | 106 (24) | 121 (42) | <0.0001 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dl | 54 (17) | 50 (16) | 0.0004 |

| Triglyceride, median (IQR), mg/dl | 102 (72–143) | 119 (89–168) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m² | 24.9 (4.4) | 26.5 (4.6) | <0.0001 |

TRFs = traditional risk factors defined as hypertension (>140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive drugs), diabetes (HbA1c >7.0% or glucose-lowering drugs), hypercholesterolemia (LDL-cholesterol >140 mg/dl or use of statins), and documented atrial fibrillation.

BP: blood pressure; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; LDL: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL: high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

As shown in Table 2, uses of antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, statins, and glucose-lowering drugs were fewer at any of baseline, 1 year, and 5 years in patients without TRFs than in those with TRFs.

Table 2.

Uses of drugs at baseline, 1 year, and 5 years in patients without and with traditional risk factors.

| Variables | Patients without TRFs | Patients with TRFs | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n = 402 | n = 3445 | |

| Antiplatelets | 34/399 (8.5) | 1029/3431 (30.0) | <0.0001 |

| Anticoagulants | 8/399 (2.0) | 183/3433 (5.3) | 0.0039 |

| Antiplatelets + Anticoagulants | 0/399 (0.0) | 34/3432 (1.0) | – |

| Glucose-lowering drugs | 0/398 (0.0) | 637/3433 (18.6) | – |

| Statins | 0/398 (0.0) | 1081/3433 (31.5) | – |

| 1 year | n = 374 | n = 3191 | |

| Antiplatelets | 273/364 (75.0) | 2469/3074 (80.3) | 0.0169 |

| Anticoagulants | 36/364 (9.9) | 565/3060 (18.5) | <0.0001 |

| Antiplatelets + Anticoagulants | 4/362 (1.1) | 92/3047 (3.0) | 0.0374 |

| Glucose-lowering drugs | 6/362 (1.7) | 580/3029 (19.2) | <0.0001 |

| Statins | 161/363 (44.4) | 2132/3042 (70.1) | <0.0001 |

| 5 years | n = 323 | n = 2626 | |

| Antiplatelets | 180/292 (61.6) | 1743/2338 (74.6) | <0.0001 |

| Anticoagulants | 25/293 (8.5) | 436/2339 (18.6) | <0.0001 |

| Antiplatelets + Anticoagulants | 0/295 (0.0) | 62/2337 (2.7) | – |

| Glucose-lowering drugs | 12/295 (4.1) | 467/2335 (20.0) | <0.0001 |

| Statins | 114/295 (38.6) | 1566/2338 (67.0) | <0.0001 |

TRFs = traditional risk factors defined as hypertension (>140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive drugs), diabetes (HbA1c >7.0% or glucose-lowering drugs), hypercholesterolemia (LDL-cholesterol >140 mg/dl or use of statins), and documented atrial fibrillation.

Table 3 shows the primary and secondary outcomes at 1 and 5 years in patients without and with TRFs. While MACE, vascular death, and any death were significantly fewer in patients without TRFs than in those with TRFs at 5 years, there were no significant differences in any outcome at 1 year between patients with and without TRFs. However, the risk of recurrent stroke was non-significantly lower in patients without TRFs than in those with TRFs at 5 years (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.46–1.02).

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcomes at 1 and 5 years in patients without and with traditional risk factors.

| Variables | Patients without TRFs | Patients with TRFs | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | ||||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Major CV events | 21 (5.3) | 214 (6.3) | 0.84 (0.53–1.31) | 0.43 |

| Vascular death | 1(0.3) | 17 (0.5) | 0.50 (0.07–3.75) | 0.50 |

| Non-fatal stroke | 19 (4.7) | 160 (4.7) | 1.01 (0.63–1.63) | 0.95 |

| Non-fatal ACS | 1(0.3) | 30 (0.9) | 0.28 (0.04–2.08) | 0.22 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| Any death | 6 (1.5) | 70 (2.1) | 0.73 (0.32–1.69) | 0.46 |

| Stroke | 20 (5.0) | 176 (5.2) | 0.97 (0.61–1.54) | 0.90 |

| TIA | 200 (5.9) | 25 (6.3) | 1.08 (0.71–1.63) | 0.73 |

| ICH | 1 (0.3) | 11 (0.3) | 0.78 (0.10–6.02) | 0.81 |

| Major bleeding | 1 (0.3) | 12 (0.4) | 0.71 (0.09–5.48) | 0.74 |

| 5 years | ||||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Major CV events | 30 (7.9) | 439 (13.9) | 0.57 (0.39–0.82) | 0.0026 |

| Vascular death | 2 (0.5) | 94 (3.1) | 0.18 (0.04–0.73) | 0.0160 |

| Non-fatal stroke | 25 (6.5) | 276 (8.7) | 0.76 (0.51–1.15) | 0.19 |

| Non-fatal ACS | 3 (0.9) | 76 (2.5) | 0.33 (0.10–1.04) | 0.0589 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| Any death | 17 (4.5) | 356 (11.3) | 0.40 (0.25–0.65) | 0.0002 |

| Stroke | 26 (6.8) | 319 (10.1) | 0.68 (0.46–1.02) | 0.0625 |

| TIA | 26 (6.6) | 281 (8.7) | 0.79 (0.53–1.18) | 0.25 |

| ICH | 2 (0.6) | 37 (1.2) | 0.46 (0.11–1.89) | 0.28 |

| Major bleeding | 2 (0.6) | 51 (1.7) | 0.33 (0.08–1.35) | 0.12 |

Traditional risk factors (TRFs) were defined as hypertension (>140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive drugs, diabetes (hemoglobin A1c >7.0% or glucose-lowering drugs), hypercholesterolemia (low density lipoprotein cholesterol >140 mg/dl or use of statins), and documented atrial fibrillation.

Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, mRS, and ABCD 2 score. The number of patients with major CV events was that of those with the first event of cardiovascular death, non-fatal stroke, or non-fatal ACS.

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; CV: cardiovascular; ICH: intracranial hemorrhage; TIA: transient ischemic attack; TRFs: traditional risk factors.

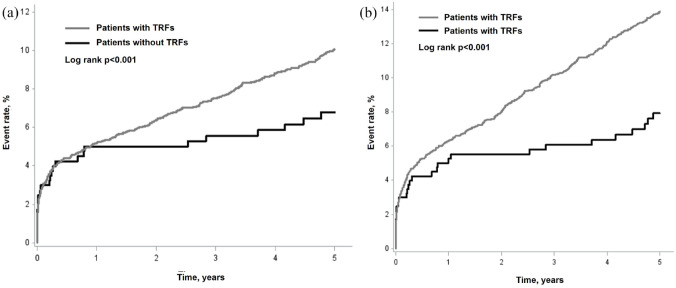

Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrent stroke and MACE. The curves were comparable between patients with and without TRFs during the first year, while the curves became separated, namely, the curve continuously increased in patients with TRFs, while almost plateaued in patients without TRFs during 1 to 5 years period.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrent stroke (a) and major cardiovascular events (b) in patients with and without traditional risk factors. Major cardiovascular event was defined as the first event of nonfatal stroke, nonfatal acute coronary syndrome, or vascular death.

In univariable regression analysis, age, stroke, coronary artery disease, primary education, ABCD 2 score 4–5, acute infarction, multiple infarctions, NIHSS ≧1, mRS ≧1, and ASCOD A1/A2 were associated with 5-year risk of stroke and vascular events in patients without TRFs (Supplemental Table). In multivariable regression analysis, NIHSS 1 or more at discharge, ASCOD A1/A2, and mRS ≧1 were independent risks for MACE at 1 year, while NIHSS 1 or more at discharge, mRS ≧1, ASCOD A1/A2, age per 10-year increase, and diastolic blood pressure per 9-mmHg increase were significant risks for MACE at 5 years among patients without TRFs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable regression analysis for 1- and 5-year risks of major cardiovascular events in patients without traditional risk factors.

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1-year risk | ||

| NIHSS at discharge | ||

| 0 | 1 (reference) | |

| ⩾1 | 2.65 (1.13–6.22) | <0.01 |

| ASCOD A | ||

| A0/A3/A9 | 1 (reference) | |

| A1/A2 | 5.21 (2.36–11.50) | <0.01 |

| mRS at discharge >1 | 13.84 (2.30–81.58) | <0.01 |

| 5-year risk | ||

| NIHSS at discharge | ||

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| ⩾1 | 3.31 (1.41–7.73) | <0.01 |

| ASCOD A | ||

| A0/A3/A9 | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| A1/A2 | 5.67 (2.68–12.02) | <0.01 |

| mRS at discharge >1 | 7.33 (1.31–40.93) | 0.024 |

| Age per 10 years increase | 1.28 (1.00–2.42) | 0.049 |

| Diastolic BP, per 9 mmHg increase | 1.59 (1.05–2.42) | 0.029 |

The criteria for ASCOD are shown in the manuscript. Variables included in the model were coronary artery disease, acute infarction, mRS at discharge >1, NIHSS at discharge, ASCOD classification, and age per 10 years increase at 1 year, and qualifying event, coronary artery disease, ABCD 2 score, acute infarction, mRS at discharge >1, NIHSS at discharge, ASCOD classification, age per 10 years increase, and diastolic blood pressure per 9 mmHg increase at 5 years.

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS: modified Rankin scale score; BP: blood pressure.

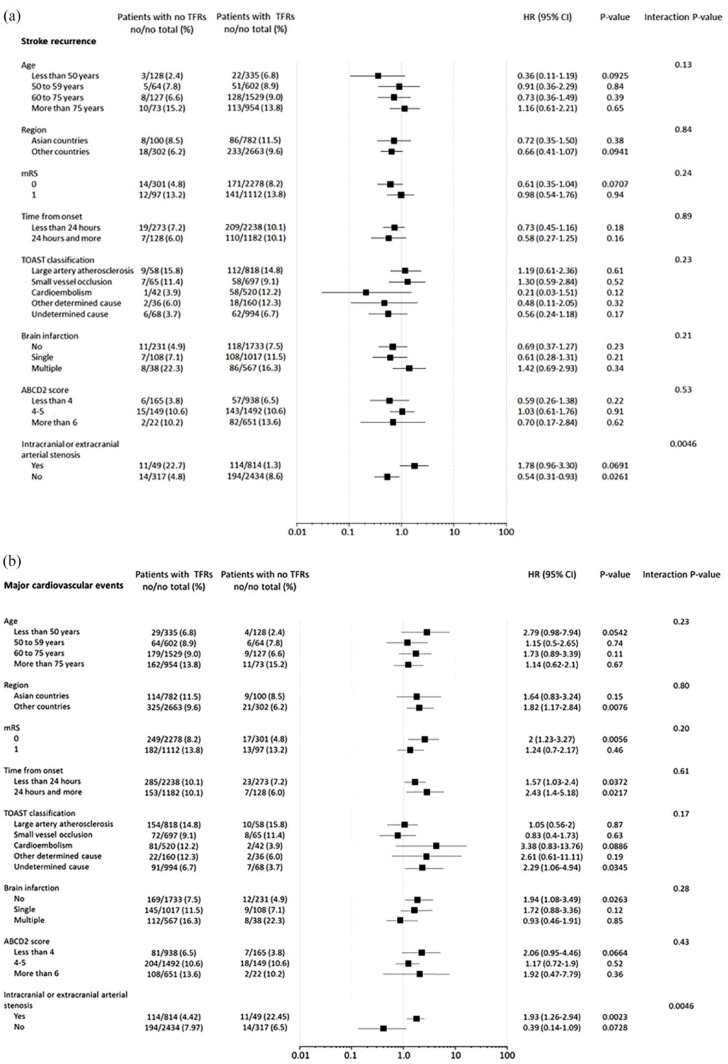

Figure 2 represents multivariable subgroup analysis for predictors of recurrent stroke and MACE at 5 years in patients without TRFs. There was a significant interaction only between the presence and absence of ipsilateral 50% or more stenosis in intracranial or extracranial arteries. That is, the risk tended to be higher in patients with arterial stenosis, and was significantly lower in those without arterial stenosis among patients without TRFs.

Figure 2.

Multivariable subgroup analysis for predictors of recurrent stroke (a) and major vascular events (b) at 5 years in patients without traditional risk factors. Major cardiovascular event was defined as the first event of nonfatal stroke, nonfatal acute coronary syndrome, or vascular death.

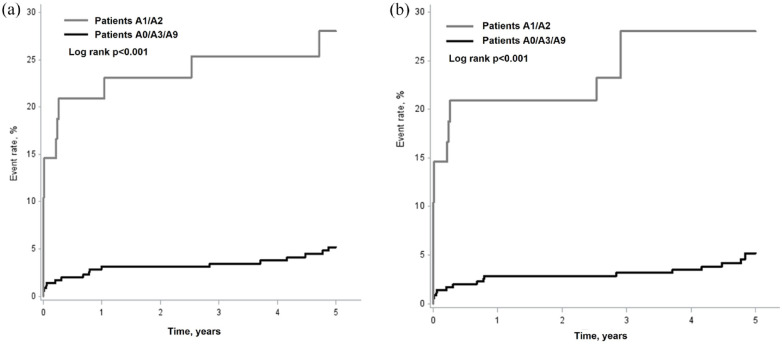

Figure 3 shows Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrent stroke and MACE according to ASCOD grading in patients without TRFs. The curves already separated during the first year after TIA or minor IS, and continued to more separate during 1–5 years, which showed that cumulative risk of recurrent stroke and MACE became higher as the observation period became longer in patients with causal atherosclerosis (ASCOD A1/A2) than in those without (ASCOD A0/A3/A9), in whom the risk plateaued overtime.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of recurrent stroke (a) and major cardiovascular events (b) according to ASCOD grading in patients without traditional risk factors. Major cardiovascular event was defined as the first event of nonfatal stroke, nonfatal acute coronary syndrome, or vascular death. See the ASCOD criteria in the manuscript.

Discussion

The risk of MACE did not differ at 1 year, while it was significantly lower at 5 years in those without than with TRFs. In subgroup analyses for recurrent stroke and MACE, an interaction was significant only in the presence or absence of intracranial or extracranial arterial stenosis ipsilateral to the cerebral ischemia in patients without TRFs. The association between ipsilateral intracranial/extracranial stenosis and risk of recurrent stroke/MACE in no-TRF patients is probably largely in line with the association found between ASCOD-A grading and outcome.

The use of antiplatelet agents and statins were fewer in patients without TRFs than in those with TRFs despite a similar risk of recurrent stroke and vascular events during the first year after TIA or minor IS. We reported that the risk of recurrent stroke is very high during an early period after a TIA or a minor IS. 9 Therefore, dual antiplatelet therapy during early period after acute event is recommended for the prevention of stroke in patients with TIA or minor IS, and statin therapy is also recommended in patients with symptomatic intracranial or extracranial arterial stenosis. 12 However, initiation of antiplatelet and statin treatments might be delayed or not prioritized in patients without TRFs.

ABCD 2 score did not differ between patients without and with TRFs despite the subtraction of two points (hypertension and diabetes) in patients without TRFs. 5 These results suggest that early risk of recurrent stroke and vascular events was underestimated, and thus less strictly treated in patients without TRFs. However, the results of our study implicate that aggressive strategy against early recurrence of stroke is crucial not only in patients with TRFs but also in those without TRFs regardless ABCD 2 score.

According to a meta-analysis of 13,766 TIA patients showed that ABCD 2 score ≧4 was sensitive (86.7%) but not specific (35.4%), and 20% of patients with ABCD 2 score <4 had >50% carotid stenosis or atrial fibrillation. 13 It was concluded in this study that ABCD 2 score does not reliably discriminate those at low and high risk of early recurrent stroke, identify patients with carotid stenosis or atrial fibrillation needing urgent intervention. This must be true especially in patients without TRFs since the risk of recurrent stroke is underestimated by ABCD 2 score, and arterial stenosis is likely to be overlooked because of the absence of TRFs.

There is mounting evidence that “non-TRFs” such as unhealthy diet, insufficient exercise, sleep deprivation, obesity, excessive alcohol drinking, and stressful life, which were identified in the INTERSTROKE 1 and the AHA/ASA Life’s Essential 8 14 studies, have been neglected or underestimated as risk factors for stroke and MACE. The relatively high residual risk observed in our group of patients without TRFs in the TIAregistry.org concurs with the need to include these non-TRFs.

The carotid sub-study of the Northern Manhattan Stroke study showed that TRFs explain only a minority of the variability in carotid plaque, suggesting a possible role for unaccounted non-TRFs such as environmental and genetic factors in the development of atherosclerotic plaque.3,15 Particularly, evidence to support the importance of genetic factors for intracranial and extracranial atherosclerosis is rapidly growing with the development of genetic analyses.16–19 Genetic roles should be considered in future studies in TIA patients with atherosclerosis without TRFs. The emerging role of inflammatory mechanisms is also important as independent risk factors for stroke and vascular events.20,21 Because, atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease, in which the immune system has a prominent role in its development and progression, 20 and is driven by not only TRFs but also non-TRFs. 21 NIHSS was strongly associated with recurrence of stroke in this study. There are emerging data that infarcts can induce chronic immune dysfunction and pro-inflammatory signaling, which may increase the risk of stroke through cardiac inflammation and atheroprogression. 22 It remains uncertain why the risk of vascular events did not continue to accumulate during the 1–5 years follow-up period in patients without TRFs, unlike those with TRFs. Atherothrombosis is a poly-vascular disease and, hence, TRFs may increase the risk of total vascular events in systemic vascular beds, mainly driven by TRFs.23,24 However, we have no follow-up data on the trajectory of atherosclerosis in this registry.

Potential risk factors other than TRFs evaluated in this study included physical activity, obesity, alcohol drinking and CKD.1,2,25 However, physical activity was more common and obesity (evaluated by BMI), alcohol drinking, and CKD were less common in patients without TRFs than in those with TRFs. It is interesting that patients in the no-TRF group were younger and predominantly female.

There are some limitations in this study. The etiologies of arterial stenosis remain uncertain in patients without TRFs since these data were not available. Residual risk factors such as lipoprotein (a), remnant lipoprotein cholesterol, vasculitis, infection, and inflammation also should be considered as the causes of arterial stenosis and were not excluded in this study.2,4,14 Genetic factors for atherosclerosis were also not available.16–19 The number of patients without TRFs was relatively small, especially for the ASCOD sub-analysis, which might have increased the chance of type I or II error. Missing data on the TOAST classification were more frequent in the no-TRF group (33%) compared to the TRF group (7%) probably because of difficulty in the classification, which might have influenced the reported association.

In conclusion, the 5-year risk of MACE was lower in patients without TRFs than in those with TRFs, although a certain level of risk persisted in the absence of TRF, suggesting that factors other than TRFs are involved in their residual risk. Extracranial or intracranial arterial stenosis was only significant predictor of recurrent stroke and MACE at 5 years in patients without TRFs. The implication may be made that more rigorous early and continued medical management is required. They include antiplatelet therapy and statins, which were underutilized here, but recommended for the prevention of recurrent stroke regardless ABCD 2 score in patients without TRFs after TIA or minor IS. 11 Further studies are needed to elucidate additional risk factors for arterial stenosis if progress is to be made in the prevention of recurrent stroke in patients without TRFs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241300071 for Risk of major vascular events in patients without traditional risk factors after transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke: An international prospective cohort by Shinichiro Uchiyama, Takao Hoshino, Kazuo Minematsu, Marie-Laure Meledje, Hugo Charles, Gregory W Albers, Louis R Caplan, Geoffrey A Donnan, José M Ferro, Michael G Hennerici, Carlos Molina, Peter M Rothwell, Lawrence KS Wong and Pierre Amarenco in European Stroke Journal

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all collaborators of TIAregistry.org for patients’ recruitment, follow-up, and data collection.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Statistical analysis, and writing and submitting manuscript for this study were supported by a grant from the Japan Cardiovascular Research Foundation. The TIA registry.org was funded by SOS-ATTAQUE Cérébrale Association through an unrestricted grant from SANOFI and Bristol Myers Squibb, and from AstraZeneca.

Ethical approval: All patients provided written or oral informed consent according to country regulations.

Informed consent: All patients gave written or oral infromed consent according to country regulation.

Guarantor: Shinichiro Uchiyama.

Contributorship: SU planned the subgroup analysis and wrote the original draft of the manuscript and revisions. PA was the Principal Investigator of the study, and reviewed, supervised, and revised the manuscript. HC and ML analyzed and interpreted the data. TH and KM reviewed and advised the manuscript. Other authors were steering committee members of the study, who reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Shinichiro Uchiyama  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6280-8190

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6280-8190

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. O’Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, et al. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet 2016; 388: 761–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol 2021; 20: 795–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bang OY, Ovbiagele B, Kim JS. Nontraditional risk factors for stroke. Stroke 2015; 46: 3571–3578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ionita CC, Xavier AR, Kirmani JF, et al. What proportion of stroke is not explained by classic risk factors? Prev Cardiol 2005; 8: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to 301 predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2007; 369: 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prabhakaran S, Messé SR, Kleindorfer D, et al. Cryptogenic stroke: contemporary trends, treatments, and outcomes in the United States. Neurol Clin Pract 2020; 10: 396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xu J, Mo J, Zhang X, et al. Nontraditional risk factors for residual recurrence risk in patients with ischemic stroke of different etiologies. Cerebrovasc Dis 2022; 51: 630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang W. Residual recurrence risk of ischaemic cerebrovascular events: concept, classification, and implications. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2021; 6: 155–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med 2016; 174: 1533–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 2182–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, et al. The ASCOD phenotyping of ischemic stroke (Updated ASCO Phenotyping). Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 36: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a Guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021; 52: e364–e467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wardlaw JM, Brazzelli M, Chappell FM, et al. ABCD2 score and secondary stroke prevention. Meta-analysis and effect per 1,000 patients triaged. Neurology 2015; 85: 373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, et al. Life’s Essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from American Heart Association. Circulation 2022; 146: e18–e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kuo F, Gardener H, Dong C, et al. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors explain the minority of the variability in carotid plaque. Stroke 2012; 43: 1755–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bellomo TR, Bone WP, Chen BY, et al. Multi-trait genome-wide association study of atherosclerosis detects novel pleiotropic loci. Front Genet 2022; 12: 787545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Örd T, Lönnberg T, Nurminen V, et al. Dissecting the polygenic basis of atherosclerosis via disease-associated cell state signatures. Am J Hum Genet 2023; 110: 722–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malka K, Liaw L. NOTCH 3 as a modulator of vascular disease: a target in elastin deficiency and vascular pathology. J Clin Invest 2022; 132: e157007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koizumi A, Kobayashi H, Hitomi T, et al. A new horizon of moyamoya disease and associated with health risks explored through RNF213. Environ Health Prev Med 2016; 21: 55–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henein MY, Vancheri S, Longo G, et al. The role of inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23: 12906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kong P, Cui Z, Huang X, et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022; 7: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shimats A, Liesz A. Systemic inflammation after stroke: implications for post-stroke comorbidities. EMBO Mol Med 2022; 14: e16269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uchiyama S. Intensive medical management of intracranial arterial stenosis. Lancet Neurol 2020; 19: 371–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2006; 295: 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sarikaya H, Ferro J, Arnold M. Stroke prevention: medical and life style measures. Eur Neurol 2015; 73: 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241300071 for Risk of major vascular events in patients without traditional risk factors after transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke: An international prospective cohort by Shinichiro Uchiyama, Takao Hoshino, Kazuo Minematsu, Marie-Laure Meledje, Hugo Charles, Gregory W Albers, Louis R Caplan, Geoffrey A Donnan, José M Ferro, Michael G Hennerici, Carlos Molina, Peter M Rothwell, Lawrence KS Wong and Pierre Amarenco in European Stroke Journal