Abstract

Background

Minimally invasive spine surgery has seen rapid development in recent years. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion (ULIF) versus minimally invasive surgery transforaminal interbody fusion (MIS-TLIF) for the treatment of single-segment lumbar degenerative disease (LDD) through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

In collaboration with various search terms, a comprehensive examination of the scientific literature was carried out using PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang, and other databases. A total of 9 studies were included retrospective cohort studies.

Results

We observed statistically significant differences in intraoperative blood loss, total hospital stay, postoperative hospital stays, and 1-month postoperative Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups, with the ULIF group being more dominant. MIS-TLIF group was statistically more advantageous in terms of operative time. There were no statistically significant differences in postoperative visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, 3-month postoperative and final ODI scores, excellent and good rate, complications, disc heights, and lumbar lordosis angle between the two groups.

Conclusions

Treatment of single-segment LDD with ULIF and MIS-TLIF is both safe and effective. ULIF has the advantage of less intraoperative blood loss, shorter total hospital stay, shorter postoperative hospital stay, and lower ODI scores at 1 month postoperatively compared to MIS-TLIF. There were no significant differences between ULIF and MIS-TLIF in the treatment of LDD in terms of postoperative VAS scores, 3-month postoperative and final ODI scores, satisfaction rates, fusion rates, complications, disc heights, and lumbar lordosis angle. MIS-TLIF has a shorter procedure time than ULIF.

Keywords: Unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion, Minimally invasive surgery transforaminal interbody fusion, Lumbar degenerative disease, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Lumbar degenerative disease are a group of diseases in which degeneration of the tissue structure of the lumbar spine occurs with aging. In cases of lumbar degenerative disease associated with instability, fusion surgery might be required [1]. Lumbar interbody fusion (LIF) is a commonly performed surgery that restores stability to the lumbar spine and treats lumbar spondylolisthesis [2–4].

MIS-TLIF has gained increased attention in the spinal community as a result of its small trauma, lower intraoperative blood loss and favorable clinical outcomes [5, 6]. A difference between MIS-TLIF and open procedures is that the surgeon can establish a channel through the paravertebral muscle space, avoiding excessive muscle and ligament damage, reducing bleeding, accelerating recuperation, and shortening hospitalization times [7, 8]. There are, however, some problems with MIS-TLIF. A limitation in the field of vision usually results from narrow working channels in MIS-TLIF surgery [9]. Furthermore, as well as limiting visual field and movement space, tubular retractors also cause muscular ischemia [10].

Combining TLIF surgery with an microscope can enhance surgical efficiency by providing a clear surgical field [11]. In 2017, Initially introduced by Heo et al., the Unilateral biportal endoscopy (UBE) spine technology has been successful in lumbar intervertebral fusion [12]. The unique advantages of UBE have led to its increasing popularity among spine surgeons. UBE has two viewing portals, so it has a broader surgical vision and more operational flexibility than coaxial single-port spinal endoscopy [13, 14]. By applying ULIF technology, spinal canal decompression and interbody fusion can be accomplished endoscopically [15].

ULIF and MIS-TLIF procedures are widely used in spine surgery, however, we found a paucity of literature examining studies comparing the safety and efficacy of the ULIF procedure with the MIS-TLIF procedure for single-segment LDD. The main objective of our meta-analysis was to provide evidence of relevant evidence-based medicine for the treatment and prevention of orthopedic diseases by comparing the outcomes of ULIF procedure and MIS-TLIF procedure for the treatment of single-segment LDD.

Materials and methods

Study selection and search strategy

As of August 2023, we searched PubMed, Web of Science, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, CNKI, and Wanfang for relevant studies. In order to identify and select studies, the search strategy followed guidelines established by PRISMA [16]. We searched for the following titles and keywords: “unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion”, “minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion”, “degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis”, “lumbar degenerative disease”, “ULIF”, “DLS”, “LDD”, and “MIS-TLIF”. These keywords were searched separately, while variations and synonyms can be explored by combining free words with subject headings. Use logical operators like ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ to connect keywords and free words. We searched for and evaluated the references lists of all eligible studies.

Inclusion criteria

Our study was subject to the following criteria: neurologic symptoms such as low back pain or concomitant radicular leg pain that had failed to respond to 3 months of conservative treatment or had not improved significantly; degenerative disease of the lumbar spine of a single segment (herniated lumbar discs and/or spinal stenosis combined with lumbar instability) that required decompression and fusion or fusion alone; and symptoms and signs consistent with imaging findings; Also our included studies included at least one of the following outcomes: operative time, VAS including back and legs, ODI score, complication rate, postoperative excellent and good rates, intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay, postoperative hospital stay, fusion rate, disc height, and lumbar lordosis angle. A retrospective cohort study was used for the study.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) history of previous lumbar spine surgery; (2) incomplete clinical data; (3) concomitant lumbar spine infections, lumbar spine tuberculosis, lumbar spine tumors, etc.; (4) multisegmental lumbar spine degenerative diseases; (5) lumbar spondylolisthesis greater than grade II; and (6) the number of patients in the study was less than 10 in both groups.

Data extraction

Data were extracted and analyzed independently by two reviewers: Table 1 lists the authors, year of issue, study design, country, number of patients, age of the patient, patient gender, operative level, body mass index (BMI) and follow-up time. Objectionable results obtained are adjudicated by the third adjudicator.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study (auther yr) | Design | Country | Group | Sample size | Age | Sex (M/F) | Operative level | BMI (kg/m2) | FU (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo (2023) | Retrospective | China |

UBE-TLIF MMIS-TLIF |

26 23 |

64.15 ± 6.42 64.15 ± 6.42 |

12:14 10:13 |

L3/4 (5) L4/5 (12) L5/S1 (9) L3/4 (4) L4/5 (11) L5/S1 (8) |

NA NA |

24 24 |

| Huang (2023) | Retrospective | China |

BE-LIF MIS-TLIF |

38 44 |

60.13 ± 7.36 59.68 ± 6.94 |

22:16 26:18 |

L3/4 (0) L4/5 (28) L5/S1 (10) L3/4 (1) L4/5 (30) L5/S1 (13) |

24.96 ± 1.51 25.10 ± 1.25 |

> 12 > 12 |

| Jiang (2022) | Retrospective | China |

ULIF MIS-TLIF |

25 25 |

63.28 ± 8.51 59.68 ± 10.38 |

9:16 8:17 |

L4/5 (24) L5/S1 (1) L4/5 (23) L5/S1 (2) |

NA NA |

3 3 |

| Kim (2021) | Retrospective | South Korea |

BE-TLIF MI-TLIF |

32 55 |

70.5 ± 8.26 67.3 ± 10.7 |

17:15 25:30 |

L2/3 (1) L3/4 (3) L4/5 (20) L5/S1 (8) L2/3 (0) L3/4 (2) L4/5 (46) L5/S1 (7) |

NA NA |

27.2 ± 5.4 31.5 ± 7.3 |

| Song (2023) | Retrospective | China |

ULIF MIS-TLIF |

25 24 |

52.36 ± 10.69 56.38 ± 10.53 |

9:16 8:16 |

L3/4 (2) L4/5 (13) L5/S1 (10) L3/4 (2) L4/5 (10) L5/S1 (12) |

NA NA |

14.04 ± 1.51 14.79 ± 1.59 |

| Yang (2023) | Retrospective | China |

ULIF MIS-TLIF |

30 35 |

49.3 ± 3.5 50.9 ± 3.6 |

12:18 20:15 |

L3/4 (6) L4/5 (15) L5/S1 (9) L3/4 (7) L4/5 (21) L5/S1 (2) |

22.3 ± 1.4 22.5 ± 1.4 |

14.79 ± 1.59 14.79 ± 1.59 |

| Yu Q (2023) | Retrospective | China |

UBE-TLIF MIS-TLIF |

23 28 |

64.30 ± 7.37 61.25 ± 9.53 |

10:13 8:20 |

L2/3 (1) L3/4 (0) L4/5 (20) L5/S1 (2) L2/3 (0) L3/4 (1) L4/5 (21) L5/S1 (6) |

24.62 ± 2.30 24.62 ± 2.30 |

> 12 > 12 |

| Yu Y (2023) | Retrospective | China |

UBE-TLIF MIS-TLIF |

23 18 |

45–74 46–71 |

11:12 8:10 |

L3/4 (3) L4/5 (11) L5/S1 (9) L3/4 (3) L4/5 (8) L5/S1 (7) |

NA NA |

36 ~ 48 36 ~ 48 |

| Zhu (2023) | Retrospective | China |

ULIF MIS-TLIF |

62 58 |

52.1 ± 12.2 51.3 ± 11.4 |

34:28 29:29 |

L2/3 (4) L3/4 (6) L4/5 (33) L5/S1 (19) L1/2 (1) L2/3 (3) L3/4 (8) L4/5 (31) L5/S1 (15) |

NA NA |

24.92 ± 5.07 25.50 ± 4.81 |

Risk of bias assessment

The cohort studies in this paper were assessed for risk of bias using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS). Independently, two assessment authors evaluated each study’s bias risk. Disagreements arising during data extraction and quality assessment were resolved through a third author.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

For the analytical approach we followed previously published studies [17]. The analysis was conducted using Review Manager 5.4 software. When categorical data is dichotomous, odds ratio (OR) are calculated, while continuous data is calculated using mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). In order to examine heterogeneity in the joint study results, the Cochran Q test was used, as well as the degree of inconsistency (I2). Fixed effects models were used if p > 0.05 and I2 < 50% otherwise random effects models were used.

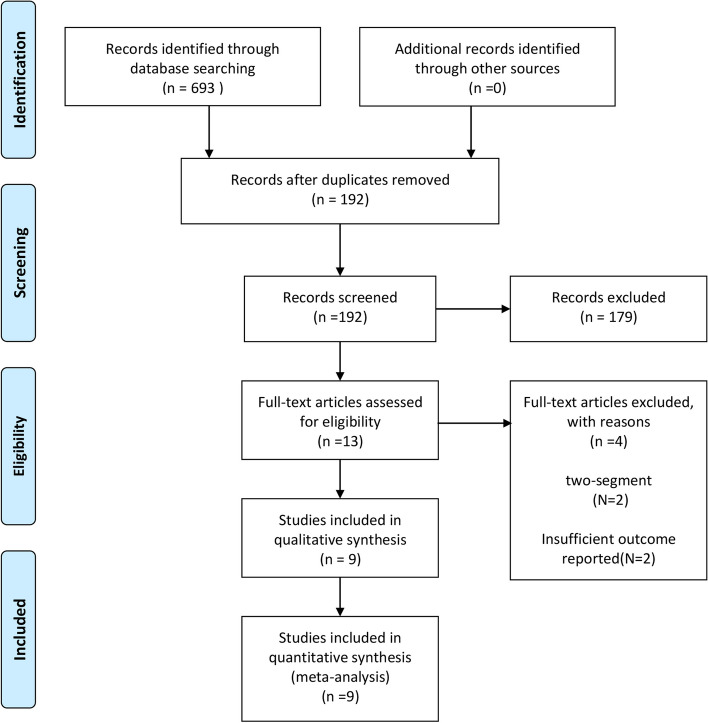

Study characteristics

Our database contained 693 studies, 192 of which were screened, and 13 of which met our criteria at the initial screening stage. The full texts of 13 articles were reviewed. There were four studies we excluded: (1) two-segment LDD (n = 2) and (2) insufficient outcome reported (n = 2). In this study, 9 retrospective studies including 594 patients were listed in the PRISMA flow diagram [1, 9, 18–24] (Fig. 1). Studies comparing ULIF and MIS-TLIF for the treatment of single-segment LDD were conducted in all studies.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting how selected articles were included in the meta-analysis

Study quality assessment

Retrospective studies were evaluated using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) Table 2. The 9 studies received 6, 7, and 8 scores, with any disagreements resolved through group discussions.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of studies in the meta-analysis based on newcastle–ottawa scale

Meta-analysis results

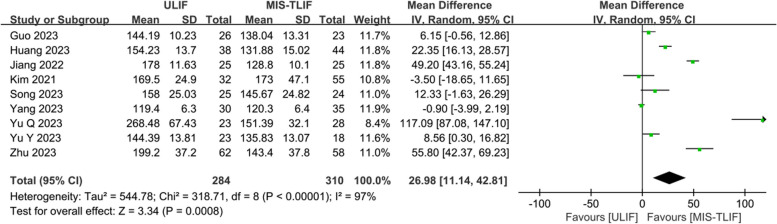

Operation time (min)

Nine studies were analyzed, including 284 ULIF patients and 310 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed high heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0.00001, I2 = 97%), so we used a random effect model for the analysis. The operative times was significantly shorter in the MIS-TLIF group than in the ULIF group for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: 26.98; 95% CI:11.14 to 42.81; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Here is a forest plot comparing operation time

Hospital stay

Four studies were analyzed, including 111 ULIF patients and 131 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed low heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0.32, I2 = 14%), so we used a fixed effects model for the analysis. The length of hospitalization was significantly shorter in the ULIF group than in the MIS-TLIF group for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -2.10; 95% CI: -2.54 to -1.67; Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Here is a forest plot comparing (A) hospital stay time and (B) postoperative hospital stay time

Postoperative hospital stays (days)

Four studies were analyzed, including 148 ULIF patients and 155 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed low heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0.94, I2 = 0%), so we used a fixed effects model for the analysis. The postoperative hospital stays was significantly shorter in the ULIF group than in the MIS-TLIF group for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -0.96; 95% CI: -1.29 to -0.64; Fig. 3B).

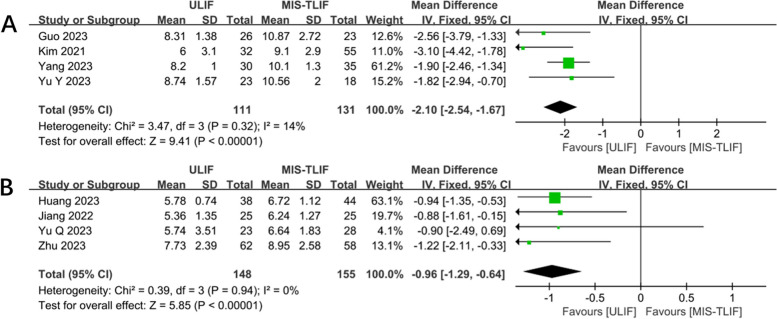

Intraoperative blood loss (ml)

Six studies were analyzed, including 197 ULIF patients and 195 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed high heterogeneity between the study groups (P < 0.00001; I2 = 98%), so we used a random effects model for the analysis. The intraoperative blood loss was significantly less in the ULIF group than in the MIS-TLIF group for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -32.67; 95% CI: -60.50 to -4.83; Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Here is a forest plot comparing (A) Intraoperative blood loss and (B) complications rates

Complications rates

Six studies were analyzed, including 211 ULIF patients and 233 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed low heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0.97; I2 = 0%), so we used a fixed effects model for the analysis. For the treatment of single-segment LDD, the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups showed no significant difference in complications (OR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0. 46 to 1.77; Fig. 4B).

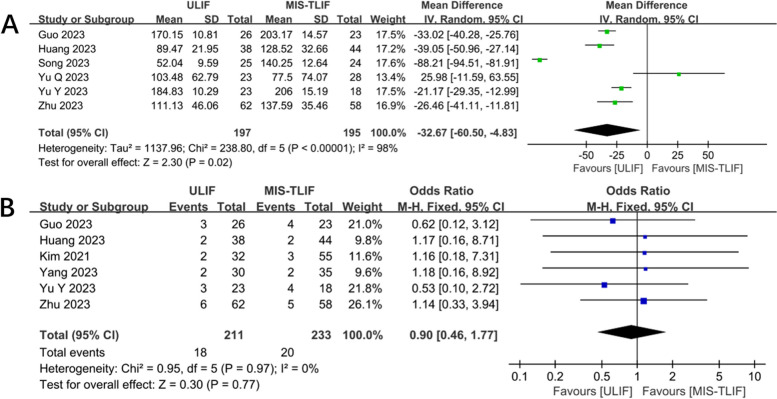

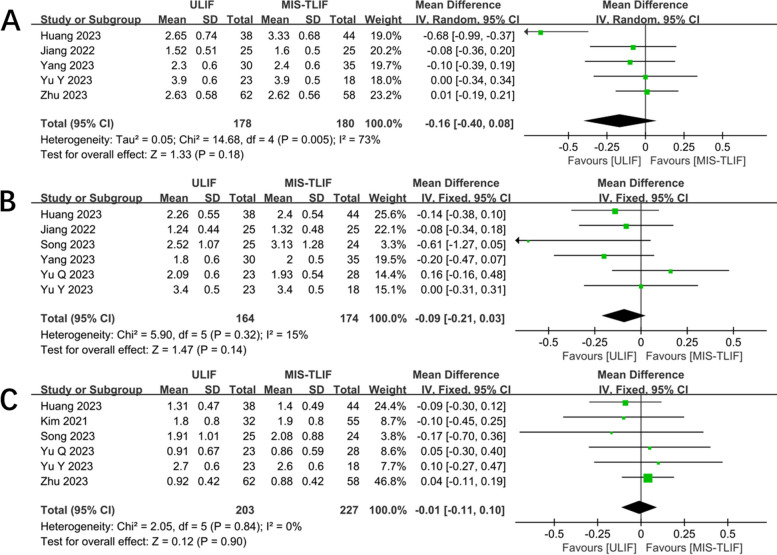

After operation 1 month VAS (back)

Five studies were analyzed, including 178 ULIF patients and 180 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed high heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0.005; I2 = 73%), so we used a random effects model for the analysis. For the treatment of single-segment LDD, the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups showed no significant difference in in the postoperative 1 month VAS scores (MD: -0.16; 95% CI: -0. 40 to 0.08; Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot showing VAS (back) at 1 month postoperative (A), 3 months postoperative (B), and final postoperative follow-ups (C)

After operation 3 month VAS (back)

Six studies were analyzed, including 164 ULIF patients and 174 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed low heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0.32; I2 = 15%), so we used a fixed effects model for the analysis. For the treatment of single-segment LDD, the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups showed no significant difference in the postoperative 3 month VAS scores (MD: -0.09; 95% CI: -0.21 to 0.03; Fig. 5B).

VAS at finial follow-up (back)

VAS of back pain at finial follow-up were analyzed in 203 patients with ULIF and 227 patients with MIS-TLIF. Statistically, VAS of back pain at finial follow-up study showed low heterogeneity (P = 0.84; I2 = 0%), and the analysis was performed using a fixed effects model. VAS of back pain at finial follow-up were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -0.01; 95% CI: -0.11 to 0.10; Fig. 5C).

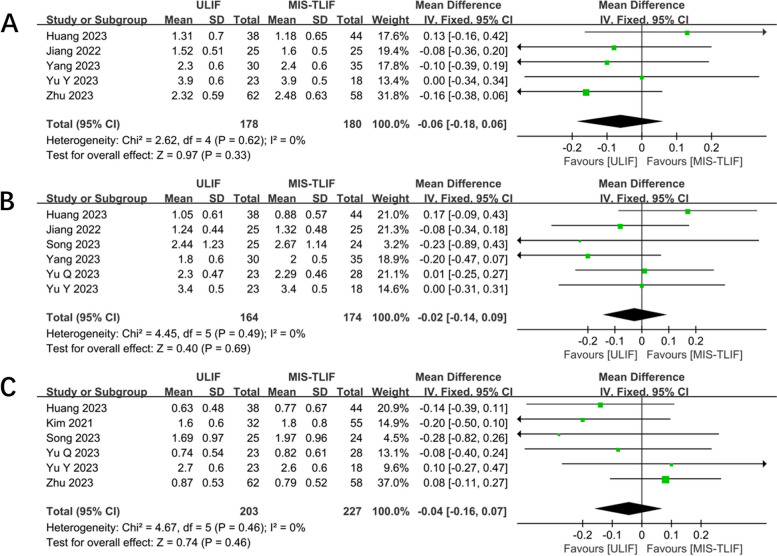

After operation 1 month VAS (leg)

In five studies, 178 patients in the ULIF group and 180 patients in the MIS-TLIF group were analyzed for 1 month postoperative VAS of leg pain. Fixed effects models were established based on low heterogeneity (P = 0.62; I2 = 0%). For the treatment of single-segment LDD, the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups showed no significant difference in the postoperative 1 month VAS of leg pain (MD: -0.06; 95% CI: -0. 18 to 0.06; Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot showing VAS (leg) at 1 month postoperative (A), 3 months postoperative (B), and final postoperative follow-ups (C)

After operation 3 month VAS (leg)

Six studies were analyzed, including 164 ULIF patients and 174 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed low heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0. 49; I2 = 0%), so we used a fixed effects model for the analysis. For the treatment of single-segment LDD, the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups showed no significant difference in the postoperative 3 month VAS of leg pain (MD: -0.02; 95% CI: -0.14 to 0.09; Fig. 6B).

VAS at finial follow-up (leg)

Six studies were analyzed, including 203 ULIF patients and 227 MIS-TLIF patients. The results showed low heterogeneity between the study groups (P = 0.46; I2 = 0%), so we used a fixed effects model for the analysis. VAS of leg pain at finial follow-up were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -0.04; 95% CI: -0.16 to 0.07; Fig. 6C).

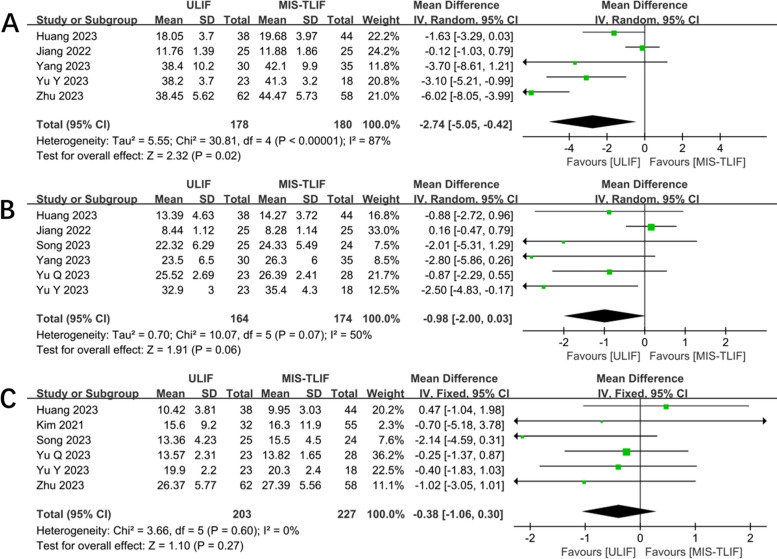

After operation 1 month ODI

Five studies analyzed 1 month postoperative ODI in 178 ULIF and 180 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was high (P < 0.00001; I2 = 87%), and random effects model was established. In the treatment of single-segment LDD, the 1-month postoperative ODI was lower in the ULIF group than in the MIS-TLIF group (MD: -2.74; 95% CI: -5. 05 to -0.42; Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot showing ODI at 1 month postoperative (A), 3 months postoperative (B), and final postoperative follow-ups (C)

After operation 3 months ODI

Six studies analyzed 3 month postoperative ODI in 164 ULIF and 174 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was high (P = 0. 07; I2 = 50%), and random effects model was established. For the treatment of single-segment LDD, the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups showed no significant difference in the postoperative 3 month ODI (MD: -0.98; 95% CI: -2.00 to 0.03; Fig. 7B).

ODI at finial follow-up

Six studies analyzed finial follow-up ODI in 203 ULIF and 227 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was low (P = 0.60; I2 = 0%), and fixed effects model was established. ODI at finial follow-up were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -0.38; 95% CI: -1.06 to 0.30; Fig. 7C).

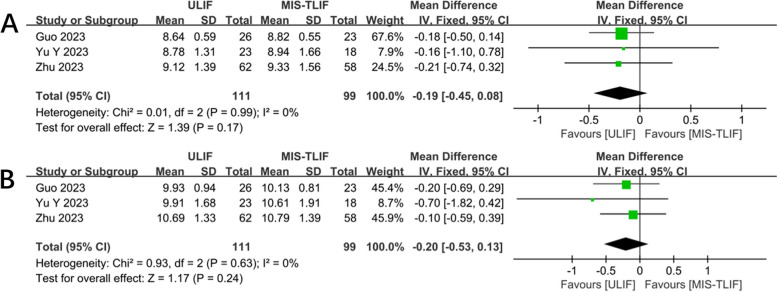

Pre disc height (DH)

Three studies analyzed pre disc height in 111 ULIF and 99 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was low (P = 0. 99; I2 = 0%), and fixed effects model was established. Pre disc height scores were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -0.19; 95% CI: -0.45 to 0.08; Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot for preoperative disc height (A) and after operation disc height (B) compared between two groups

After operation disc height (DH)

Three studies analyzed postoperation disc height in 111 ULIF and 99 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was low (P = 0. 63; I2 = 0%), and fixed effects model was established. Postoperation disc height scores were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -0.20; 95% CI: -0.53 to 0.13; Fig. 8B).

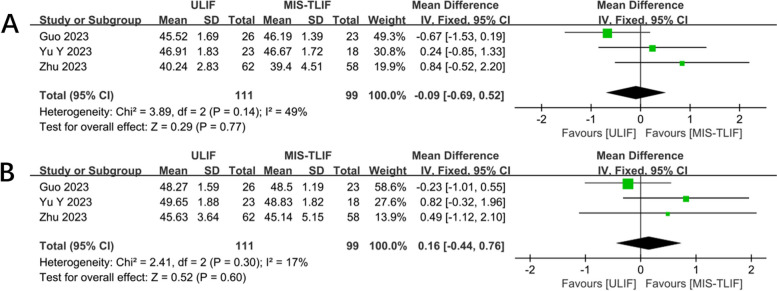

Pre the lumbar lordosis angle (LL)

Three studies analyzed pre the lumbar lordosis angle in 111 ULIF and 99 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was low (P = 0. 14; I2 = 49%), and fixed effects model was established. Pre the lumbar lordosis angle were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: -0.09; 95% CI: -0.69 to 0.52; Fig. 9A).

Fig. 9.

Forest plot for preoperative the lumbar lordosis angle (A) and after operation the lumbar lordosis angle (B) compared between two groups

After operation the lumbar lordosis angle (LL)

Three studies analyzed postoperation the lumbar lordosis angle in 111 ULIF and 99 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was low (P = 0. 30; I2 = 17%), and fixed effects model was established. Postoperation the lumbar lordosis angle were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: 0.16; 95% CI: -0.44 to 0.76; Fig. 9B).

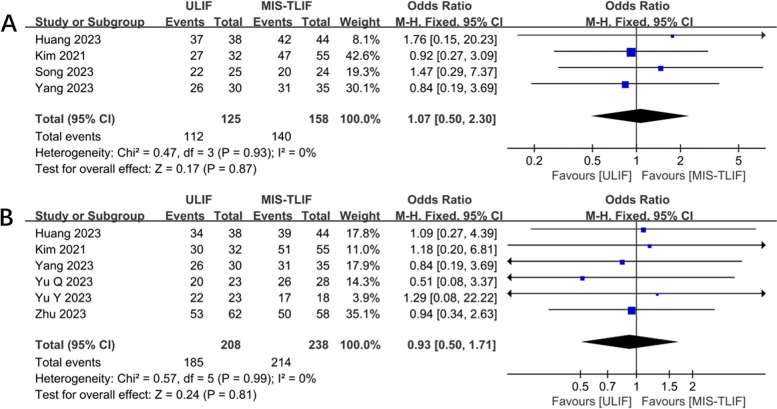

Excellent and good rate

Four studies analyzed excellent and good rate in 125 ULIF and 158 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was low (P = 0.93; I2 = 0%), and fixed effects model was established. Excellent and good rate were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.50 to 2.30; Fig. 10A).

Fig. 10.

This plot compares the (A) the (excellent and good) postoperative rates and (B) fusion rates between the two groups

Fusion rate

Six studies analyzed fusion rate in 208 ULIF and 238 MIS-TLIF patients. Heterogeneity of the studies was low (P = 0.99; I2 = 0%), and fixed effects model was established. Fusion rate were not significantly different between the ULIF and MIS-TLIF groups for the treatment of single-segment LDD (MD: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.50 to 1.71; Fig. 10B).

Sensitivity analysis

A random effects model was used for all. Combined effect sizes were performed after excluding one study in turn, and changes in overall effect sizes were observed. No studies were found in Fig. 11 that had a relatively large effect on the overall effect size.

Fig. 11.

Sensitivity analysis for results (A Sensitivity analysis of operation time in two groups; B sensitivity analysis of intraoperative bleeding in two groups; C Sensitivity analysis of back pain VAS score at 1 month after surgery in both groups; D Sensitivity analysis of ODI score at 1 month postoperatively in both groups; E Sensitivity analysis of ODI score at 3 months postoperatively in both groups)

Discussion

It is commonly found in patients with DLS that they also have lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS), based on anatomic and clinical manifestations [25]. Currently, LSS is generally thought to be treated by relieving nerve compression and restoring spine sequence and stability. A decompression-based interbody fusion and fixation is often needed when a patient has DLS at the same time [18].

There is no doubt that TLIF is the gold standard for interbody fusion surgery [26]. The traditional open TLIF, however, damages the posterior spine, which may result in spine instability and more complications postoperatively [27]. While reducing intraoperative blood loss, muscle damage, and postoperative pain, minimally invasive TLIF offers comparable fusion rates to conventional open surgery, enabling patients to ambulate sooner [28, 29]. The MIS-TLIF procedure has been proven to be as effective long-term as traditional surgery. It also produces less trauma, less blood loss, and faster recovery after the procedure [30, 31]. MIS-TLIF, however, has limitations as well. As a result of narrow and unclear surgical vision during MIS-TLIF surgery, Guo et al. found that the efficiency of surgery is greatly affected [18].

Uniportal biportal endoscopic procedures offer another method of nerve decompression and bony fusion [32]. With UBE, there are two portals: an operation portal and a viewing portal. Using UBE technique, surgical vision can be clarified and the operation space can be increased with the help of a water medium and an arthroscope [33]. First time UBE technology has been combined with TLIF, Heo et al. [12] found that a significant improvement in VAS and ODI can be achieved with ULIF. Using ULIF, Kim et al. found satisfactory fusion rates in patients with lumbar spondylolisthesis treated with ULIF [34].

Postoperative low back pain is associated with muscle denervation and atrophy, demonstrating the importance of minimizing muscle damage during surgery [35]. The MIS-TLIF technique was performed using a quadrant retractor system, and the surgery was completed with direct vision assisted by a channel. The paravertebral muscles will usually have to be stretched during contralateral decompression, causing muscle ischemia and low back pain in the patients after surgery [1, 36]. In the ULIF procedure, two channels are created to view and perform surgery on one side of the back. An interlaminar approach is used to perform spinal canal decompression and interbody fusion maneuvers. With these two channels, there is no interference and a wide field of view, reducing traction and injury to the paravertebral muscles, and consequently reducing low back pain postoperatively [37, 38].

A significant difference was found between ULIF and MIS-TLIF procedure times according to the results of this study. The operative time for the two groups differed statistically significantly. Meta-analysis [39] found UBE learning curves to be steep, particularly in their early stages because decompression takes a long time. A learning curve study by Chen et al [40] demonstrated that surgeons with extensive experience in both endoscopic and open surgery required approximately 24 procedures to overcome the learning curve of the UBE procedure, achieve a stable level of endoscopic surgery, and significantly reduce operative time. At the same time, the results of our meta-analysis of operative time and intraoperative bleeding were heterogeneous, and in the context of our clinical experience we consider that this may be related to the learning curve of the operator.

Soft tissues behind the spine can be protected using the ULIF treatment. A combination of continuous saline irrigation and radiofrequency electrocoagulation can reduce bleeding and improve surgical vision [8]. Despite the fact that 3D microscope-guided MIS-TLIF can offer a distinct surgical perspective, the extensive dissection of the soft tissues at the back of the spine will inevitably prolong patient recovery and result in an extended hospitalization period. The amount of bleeding in the ULIF group was low, which may be due to the fact that ULIF surgical decompression and intervertebral bone grafting require saline irrigation solution perfusion, which generates a certain amount of water pressure and plays a role in compression hemostasis. At the same time, ULIF enlarges the surgical field of view through the imaging system, and the bleeding of small blood vessels can be clearly seen through the monitor, and plasma coagulation is utilized for hemostasis, which exerts a better hemostatic effect [1]. Kawaguchi [41] reported that MIS-TLIF produces direct ischemic injury to the paravertebral muscles due to the continuous pulling of the tubular retractor. Although surgical muscle loss is unavoidable, ULIF has smaller incisions and less damage to the muscle such as stripping off the retractor, minimizing muscle damage as much as possible [32]. Meanwhile, according to Kang et al., the retention of a large amount of bony tissue reduced the bleeding of cancellous bone and bleeding was further reduced by hydrostatic lavage [42].

The main common intraoperative complications of surgery for lumbar degenerative diseases are nerve traction injuries, epidural hematomas, and dural tears [21]. Complications may be related to the operator’s proficiency in operating surgical instruments and the follow-up time. The results of our analysis suggested that there was no statistical significance of complications between the two groups. In this study, both groups showed significant improvement in VAS and ODI scores at 1 month postoperatively, 3 months postoperatively, and at the final follow-up. Thus, it seems that both surgical techniques have better surgical outcomes in patients with LDD. It also suggests that ULIF and MIS-TLIF can reduce postoperative lower back pain well. The results of our study showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the ULIF group and the MIS-TLIF group in terms of postoperative disc height and lumbar lordosis angle. By comparing with the preoperative period, both groups were able to achieve better clinical outcomes after surgery, and both could improve the stability of the spine after surgery and help restore the normal order of the lumbar spine.

The ultimate goal of lumbar fusion surgery is to help patients improve their symptoms and maintain spinal stability. The key to successful surgery is to achieve bone fusion at the final surgical level. The imaging results of the study by Guo et al. showed that the fusion rates of ULIF and MIS-TLIF were 96.2% and 95.7% [18], respectively, and Kim et al. [1] reported that the fusion rates of the UBE-LIF and MIS-TLIF groups were 93.7% and 92.7%, which is in consistent with previous studies [4]. There was no significant difference in the fusion rate between the two groups, indicating that both surgical methods can achieve a high fusion rate. There have been some reports [8, 43] that continuous saline flushing within the intervertebral space during ULIF surgery can decrease blood flow and osteogenic factors, lowering fusion rates. ULIF allows for the identification and complete removal of cartilaginous endplates under direct endoscopic visualization, which provides a favorable environment for interbody fusion [15, 44]. The vertebral body endplate cannot be clearly identified in open or MIS-TLIF, whereas it is well exposed under magnified view with an endoscope during ULIF, facilitating a meticulous endplate preparation. Such an advantage may offer a favorable fusion environment by complete removal of the cartilaginous portion [10, 12]. Huang et al. found an excellence and good rate of 97.3% for ULIF and 95.4% for MIS-TLIF based on the modified MacNab criteria [9]. Statistically, there was no difference between the two groups in the rate of fusion and excellence and good, which is a good indication that both techniques are safe and useful.

Our study has several limitations: first, heterogeneity is unavoidable in meta-analyses, so we used a random effects model to combine effect sizes for some of the highly heterogeneous findings. Second, we included only retrospective analyses although through a comprehensive search, and no randomized controlled related studies were found, which could lead to possible bias between the two sets of analyses and affect the results. Second, our search strategy was limited to articles published in English and Chinese.

Conclusion

Both ULIF and MIS-TLIF are safe and effective in the treatment of single-segment DLS. ULIF has the advantage of less intraoperative blood loss, shorter total hospital stay, shorter postoperative hospital stay, and lower ODI scores at 1 month postoperatively compared to MIS-TLIF. There were no significant differences between ULIF and MIS-TLIF in the treatment of DLS in terms of postoperative VAS scores, 3-month postoperative and final ODI scores, excellent and good rates, fusion rates, complications, disc heights, and lumbar lordosis angle. MIS-TLIF has a shorter procedure time than ULIF. However, the articles included in this paper are retrospective studies with limited sample size. In the future, these results still need to be further validated by prospective randomized controlled trials with multicenter and large samples.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ULIF

Unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion

- MIS-TLIF

Minimally invasive surgery transforaminal interbody fusion

- LDD

Lumbar degenerative disease

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- ODI

Oswestry disability index

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

- LIF

Lumbar interbody fusion

- UBE

Unilateral biportal endoscopy

- DLS

Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis

- BMI

Body mass index

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- NOS

Newcastle Ottawa Scale

- OR

Odds ratio

- MD

Mean difference

- CI

Confidence interval

- DH

Disc height

- LL

Lumbar lordosis

- LSS

Lumbar spinal stenosis

Authors’ contributions

Conception: YX H, QY C; Design: YX H, QY C, J S; Literature search: YX H, J S; Investigation: YX H, QY C; Manuscript draft preparation: YX H, QY C, J S; Final manuscript writing: YX H, QY C, J S; Manuscript approval: YX H, QY C J S.

Funding

None.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The review boards of Xi’an No. 9 Hospital approved the present study. Human Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations: not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yanxing He and Qianyue Cheng are co-first authors.

References

- 1.Kim JE, Yoo HS, Choi DJ, et al. Comparison of minimal invasive versus biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for single-level lumbar disease. Clin Spine Surg. 2021;34(2):E64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz J, Zimmerman Z, Mass H, et al. Diagnosis and management of lumbar spinal stenosis: a review. JAMA. 2022;327(17):1688–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katuch V, Grega R, Knorovsky K, et al. Comparison between posterior lumbar interbody fusion and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in the management of lumbar spondylolisthesis. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2021;122(9):653–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heemskerk J, OluwadaraAkinduro O, Clifton W, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of minimally invasive versus open single-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar diseases: a meta-analysis. Spine J. 2021;21(12):2049–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An B, Ren B, Liu Y, et al. Clinical efficacy and complications of MIS-TLIF and TLIF in the treatment of upper lumbar disc herniation: a comparative study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19(1):317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phani Kiran S, Sudhir G. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion - a narrative review on the present status. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;8(22):101592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang M, You K, Choi J, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion using the biportal endoscopic techniques versus microscopic tubular technique. Spine J. 2021;21(12):2066–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han Q, Meng F, Chen M, et al. Comparison between PE-TLIF and MIS-TLIF in the treatment of middle-aged and elderly patients with single-level lumbar disc herniation. J Pain Res. 2022;29(15):1271–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang X, Wang W, Chen G, et al. Comparison of surgical invasiveness, hidden blood loss, and clinical outcome between unilateral biportal endoscopic and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar degenerative disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JE, Choi DJ. Biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with arthroscopy. Clin Orthop Surg. 2018;10(2):248–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu Y, Wang Y, Xie Y, et al. Comparison of mid-term effectiveness of unilateral biportal endoscopy-transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with minimally invasive surgery-transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion assisted with three-dimensional microscope in treating lumbar spondylolisthesis. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2023;37(1):52–8 Chinese. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo D, Son S, Eum J, et al. Fully endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion using a percutaneous unilateral biportal endoscopic technique: technical note and preliminary clinical results. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43(2):E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He D, Cheng X, Zheng S, et al. Unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy versus percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2023;173:e509–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng B, Zhang XL, Li P. Transforaminal interbody fusion using the unilateral biportal endoscopic technique compared with transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of lumbar spine diseases: analysis of clinical and radiological outcomes. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2023;24(6):e395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heo D, Hong Y, Lee D, et al. Technique of biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Neurospine. 2020;17(Suppl 1):S129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;21(339):b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Y, Wang H, Yu Z, et al. Unilateral biportal endoscopic versus uniportal full-endoscopic for lumbar degenerative disease: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sci. 2024;29(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo W, Li T, Yu T, et al. Clinical comparison of unilateral biportal endoscopic transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion verse 3D microscope-assisted transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in the treatment of single-segment lumbar spondylolisthesis with lumbar spinal stenosis: a retrospective study with 24-month follow-up. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chao J, Yonghui H, Hua Z, et al. Early clinical efficacy of unilateral dual-channel endoscopic lumbar fusion and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar fusion in the treatment of single-level lumbar spinal stenosis with instability. J Chin Acad Med Sci. 2022;44(04):563–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song X, Ren Z, Cao S, et al. Clinical efficacy of bilateral decompression using biportal endoscopic versus minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of lumbar degenerative diseases. World Neurosurg. 2023;173:e371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang Y, Shuai P, Lei C, et al. Comparative observation of unilateral dual-channel endoscopic lumbar fusion and minimally invasive transforaminal approach lumbar fusion in the treatment of single-level lumbar degenerative diseases. Shandong Med. 2023;63(08):71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi Y, Xuqi H, Xuekang P, et al. Short-term efficacy of unilateral dual-channel endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar fusion in the treatment of single-level lumbar degenerative diseases. J Spine Surg. 2023;21(04):236–41+274. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Yongtao W, Yizhou X, et al. Comparison of the medium-term efficacy of unilateral dual-channel spine endoscopy and 3D microscope-assisted lumbar interbody fusion through the intervertebral foramina in the treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis. Chin J Reconstruct Reconstruct Surg. 2023;37(01):52–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yihao Z, Xiaofei C, Zhentian W, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of unilateral dual-channel endoscopy and minimally invasive transforaminal approach lumbar interbody fusion on single-level lumbar disc herniation complicated with spinal stenosis. J Med Forum. 2023;44(09):10–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkaldy-Willis W, Wedge J, Yong-Hing K, et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1978;3(4):319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karsy M, Bisson EF. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019;30(3):333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim C, Easley K, Lee J, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive versus open transforaminal interbody lumbar fusion. Global Spine J. 2020;10(2 Suppl):143S-150S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng C, Yue W, Poh S, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes of minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(13):1385–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Zhou Y, Zhang Z, et al. Comparison of one-level minimally invasive and open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in degenerative and isthmic spondylolisthesis grades 1 and 2. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(10):1780–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao J, Zhang S, Li X, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive and open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar disc herniation: a retrospective cohort study. Med Sci Monit. 2018;1(24):8693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao G, Cao L, Du X, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive surgery transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and TLIF for treatment of lumbar spine stenosis. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:9389239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gatam AR, Gatam L, Mahadhipta H, et al. Unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion: a technical note and an outcome comparison with the conventional minimally invasive fusion. Orthop Res Rev. 2021;13:229–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pao J, Lin S, Chen W, et al. Unilateral biportal endoscopic decompression for degenerative lumbar canal stenosis. J Spine Surg. 2020;6(2):438–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J, Yoo H, Choi D, et al. Learning curve and clinical outcome of biportal endoscopic-assisted lumbar interbody fusion. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8815432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ao S, Zheng W, Wu J, et al. Comparison of preliminary clinical outcomes between percutaneous endoscopic and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar degenerative diseases in a tertiary hospital: Is percutaneous endoscopic procedure superior to MIS-TLIF? A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2020;76:136–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hua W, Wang B, Ke W, et al. Corrigendum: comparison of clinical outcomes following lumbar endoscopic unilateral laminotomy bilateral decompression and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for one-level lumbar spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Front Surg. 2021;30(8):723200. 10.3389/fsurg.2021.723200.Erratumfor:FrontSurg.2021Feb26;7:596327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pranata R, Lim M, Vania R, et al. Biportal endoscopic spinal surgery versus microscopic decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020;138:e450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, Kang S, Hong Y, et al. Clinical comparison of unilateral biportal endoscopic technique versus open microdiscectomy for single-level lumbar discectomy: a multicenter, retrospective analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin G, Yao Z, Zhang X, et al. Evaluation of the outcomes of biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion compared with conventional fusion operations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2022;160:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L, Zhu B, Zhong H, et al. The learning Curve of Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic (UBE) spinal surgery by CUSUM analysis. Front Surg. 2022;29(9):873691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawaguchi Y, Gejo R, Kanamori M, et al. Quantitative analysis of the effect of lumbar orthosis on trunk muscle strength and muscle activity in normal subjects. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7(4):483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang T, Park S, Lee S, et al. Assessing changes in cervical epidural pressure during biportal endoscopic lumbar discectomy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2020;34(2):196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi CM. Biportal endoscopic spine surgery (BESS): considering merits and pitfalls. J Spine Surg. 2020;6(2):457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park M, Park S, Son S, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes of unilateral biportal endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion (ULIF) compared with conventional posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF): 1-year follow-up. Neurosurg Rev. 2019;42(3):753–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.