Abstract

Background

Sickle cell disease is a genetic disease with multisystem involvement. More than 300,000 children are born with sickle cell disease globally, with the majority of cases being in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Uganda, about 20,000 children are born with sickle cell disease annually, with more than three-quarters dying before the age of 5 years. Those who live beyond 5 years tend to have poor health-related quality of life, numerous complications, and recurrent hospitalizations. In developing countries, most symptomatic patients are diagnosed early in childhood. Few of those not screened in childhood tend to present in adulthood with variable symptoms.

Case presentation

This case reports a 22-year-old African male patient of Toro tribe who presented with paroxysms of multiple joint pain associated with generalized body malaise for about 6 months. He presented as a referral from a lower facility with an unestablished cause of symptoms. Physical examination revealed conjunctival pallor, icterus, and tenderness of joints. Cell counts showed anemia and hemoglobin electrophoresis revealed 87% of sickled hemoglobin.

Conclusion

This case report pinpoints the importance of considering the diagnosis of sickle cell disease even in adults presenting with symptoms of sickle cell disease. It also adds to the relevance of screening at all age groups, especially in high-endemic regions such as Africa and Asia.

Keywords: Adult, Sickle cell disease, Late diagnosis, Rural Uganda

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is among the commonest devastating hemoglobinopathies. Characteristically, it presents with chronic hemolytic anemia, paroxysms of vaso-occlusion, and progressive vascular injury with ultimate multiorgan derangement. Several genetic and environmental factors interplay an individual clinical presentation [1, 2]. The vaso-occlusive component is often the most common presentation. Most of the patients present with painful crises, hemolytic anemia, acute chest syndrome, and major organ failures. This multisystem organ derangement leads to a shortened lifespan survival of as little as 42 years and 48 years for men and women, respectively [3, 4]. The age at which sickle cell disease can be diagnosed varies from one patient to another, but generally most diagnoses are made in early childhood [4].

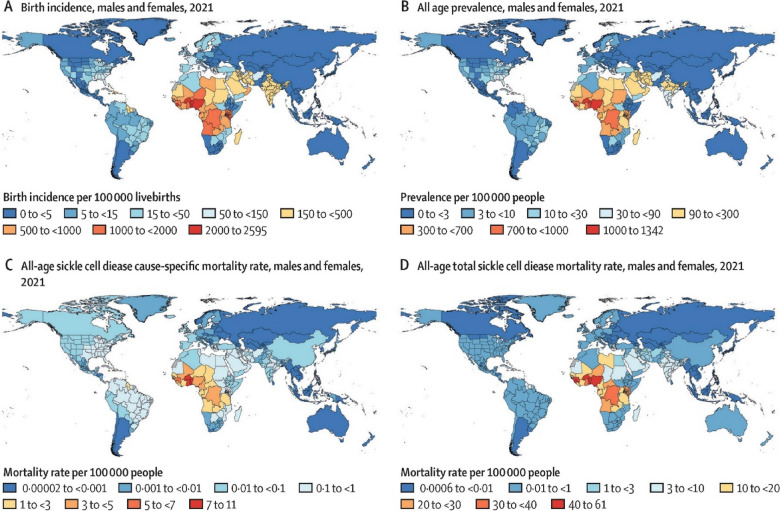

Globally, the prevalence of SCD in Sub-Saharan Africa is highest (Fig. 1), with more than 300,000 people born with SCD annually [2, 5]. The figures in Uganda are significantly higher than in the USA. The increasing figures are in part due to the newly introduced screening campaign in the country [6]. Being the fifth highest in Africa for SCD burden, 5000–20,000 children are born with SCD annually, with up to 80% estimated to die before their fifth birthday. The prevalence of sickle cell trait (SCT) is estimated to be as high as 13.3% in the general population and 5.8% among secondary school students [7].

Fig. 1.

Map showing the global, regional, and national burden of sickle cell disease. (A) Birth incidence. (B) All-age prevalence. (C) All-age cause-specific mortality. (D) All-age total sickle cell disease mortality among males and females combined in 2021. Adapted from Thomson et al. [5]

This case report highlights the importance of considering the diagnosis of SCD even in adults presenting with symptoms of SCD, especially in endemic areas.

Case presentation

In October 2023, a 22-year-old African male patient of the Toro tribe from Bunyangabu district (Western Uganda) who works as a motorcycle rider presented to Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital in the Western region of Uganda with a history of non-traumatic multiple joint pain for 2 days. The patient reported the pain to score 7 on a scale of 0–10, with 10 being the worst pain of life. The pain was predominant at the knees, lower back, and elbows. He also had generalized body malaise accompanying the course of the pain. The joint pain was worsened with movement. However, the patient could walk with a normal gait. The patient had no joint swelling or reddening, headache, fever, palpitations, or dizziness. He had normal breathing bowel and micturition habits. He reported having not been diagnosed to have any chronic disease or being transfused with blood products, but to having similar intermittent pain episodes several times in the previous 6 months, which he scaled to range from 1 to 5 on a scale of 10 and generally relieved by over-the-counter medications whose names could not be ascertained. Dental history was unremarkable. He had four siblings, among whom none had similar symptoms. He had one maternal cousin with sickle cell disease. He had no history of smoking or alcohol use and came from a low socioeconomic status.

He had an average body build and a normal nutritional status on examination. He had moderate conjunctival pallor and icterus. However, he had no finger clubbing, no palpable lymph nodes, and no areas of skin hyper or hypopigmentation. The pulse rate was 84 beats per minute, blood pressure (BP) 108/70 mmHg, temperature 36.6 °C, R+respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and was saturating at 97% in ambient air. He was alert with a Glasgow coma scale of 15/15, and negative meningismus with normal motor and sensory findings. The knee and elbows had mild to moderate tenderness but no obvious swelling or deformity was noted. He had normal abdominal fullness with no palpable masses or splenomegaly. Chest examination had bilateral equal air entry with vesicular breath sounds and normal S1 and S2 were heard with no added sound.

At the referring facility, Kibito Health Centre IV, the malaria rapid diagnostic test (MRDT), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test provider initiated Testing and Counseling (PITC) were negative, while complete blood count (CBC) showed neutrophilia and lymphopenia (described in the referral letter the patient presented with) and the patient was given a stat dose of tramadol (00 mg).

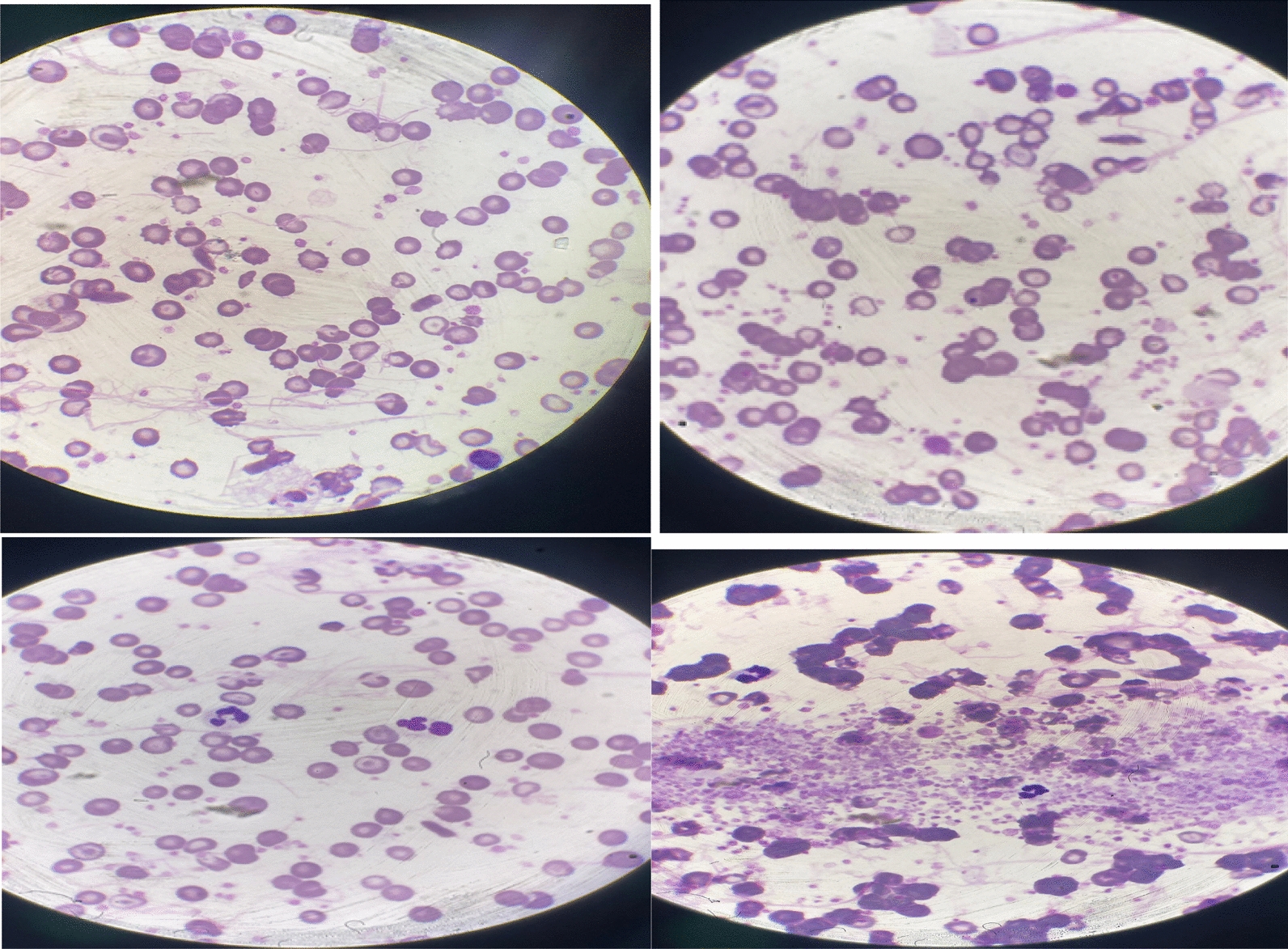

Further workups at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital included the following: complete blood count showed normocytic and normochromic anemia [hemoglobin (Hb) of 7.2 g/dl], with leukocytosis and thrombocytosis (Platelets (PLT): 781 × 109/L) (Table 1); peripheral film showed moderate anisopoikilocytosis with microcytic and hypochromic red blood cells (RBCs) with some nucleated RBCs, target cells, schistocytes, spherocytes, and Howell Jolly bodies; lymphocytosis and thrombocytosis with large platelets clumps (Fig. 2). Hb electrophoresis showed a sickled hemoglobin of 87% (Fig. 3). Iron studies and liver and renal functions were not done for financial reasons. More illustration of laboratory results is shown below. The patient received parenteral 2 L of normal saline, one liter of Ringer’s lactate, and oral ibuprofen 400 mg given twice for 1 day. During discharge, he was scheduled for regular reviews at the hospital’s sickle cell clinic where the patient was started on daily oral hydroxyurea 1000 mg and folic acid 5 mg. A month later the patient reported as having resumed his daily routine with no pain episodes, and 9 months later the patient reported no resurgence of pain.

Table 1.

Results of complete blood count showing anemia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis

| Results | Reference ranges | Flags | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 16.09 × 109/L | 4.0–12.0 | High | |

| Cell count | Percentage | |||

| LYMPH | 6.4 × 109/L | 39.8% | 1.0–4.0 | High |

| NEUT | 8.22 × 109/L | 51.1% | 2.0–7.5 | High |

| EOS | 0.19 × 109/L | 1.2% | 0.0–0.5 | |

| MONO | 0.84 × 109/L | 5.2% | 0.2–1.0 | |

| Basophils | 0.43 × 109/L | 2.7% | 0.0–0.3 | |

| HGB | 7.2 g/dl | 13.8–18.8 | Low | |

| RBC | 2.62 × 1012/L | 4.5–6.5 | Low | |

| HCT | 0.23 L/L | 0.40–0.56 | Low | |

| MCV | 89.3 fl | 79–100 | ||

| MCH | 27.5 pg | 27–35.0 | ||

| MCHC | 30.8 g/dl | 32.0–36.0 | ||

| PLT | 781 × 109/L | 150–450 | High | |

The bold is to indicate the abnormal findings

Fig. 2.

Peripheral film showing anisopoikilocytosis with microcytic and hypochromic red blood cells with some nucleated red blood cells, target cells, schistocytes, and thrombocytosis with large platelet clumps

Fig. 3.

Results of hemoglobin (Hb) electrophoresis show a predominance of hemoglobin S (87%) with the absence of hemoglobin A, A2, C, and E

Discussion

This patient presented with SCD at the age of 22 years. His key clinical presentation was episodic pain crises. He had never been screened for SCD or any hematological disease before that. This report identifies the gap in screening programs for SCD in resource-limited regions. The diagnosis of SCD should be suspected in a patient presenting with recurrent SCD-like symptoms regardless of age in endemic areas.

Sickle cell disease presenting for the first time in adulthood is not a common presentation in most of our settings. However, poor screening systems in resource-limited and rural settings seem to be the master-player in such cases. An extensive literature search failed to ascertain the exact incidence of such cases in Uganda or globally.

In India, a case report reported a 22-year-old pregnant woman who presented with an acute painful crisis had her first diagnosis of SCD in the third trimester. The late diagnosis was in part due to her financial constraint to afford the diagnostics [8]. In Nigeria, one case reported the diagnosis at the age of 52 years; this patient had also presented with pain and anemia, and the late diagnosis was linked to socioeconomic reasons [9]. Our patient also presented a delay in being diagnosed even while having recurrent painful episodes because of financial constraints.

In Uganda, the sickle cell screening program is now at work, with a focus on young patients and rooted in high-burden districts [10]. This program may help pick many patients with SCD who were not screened in the early days. However, it may miss asymptomatic adults in low-endemic districts. Our patient was asymptomatic and residing in a rural district where this screening could not be done.

In low- and middle-income countries the role of SCD in poor health-related quality of life, morbidity, and mortality among noncommunicable diseases cannot be underestimated [1, 11, 12]. Our patient had not been going to work whenever the pain would become unbearable. Chronic anemia and general disease state had made him too weak to continue with most of the activities of daily living.

Diagnosis of SCD is mainly done using cell counts, peripheral film, Hb electrophoresis, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Given the financial breakdown, we could afford to do Hb electrophoresis, which revealed sickled hemoglobin (HbS) of 87%. The 13% of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) might have played a part in the delayed clinical onset of symptoms.

SCD stands to be the most prevalent genetic disorder globally. In under-resourced areas, the diagnosis is often made when the complications have already occurred, and the existing supportive therapy is often of low-quality [6, 12]. Our patient was treated with fluids and analgesics and was scheduled for further regular reviews at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital Sickle Cell Disease Clinic, where hydroxyurea and folic acid were initiated.

Conclusion

Despite its typical presentation in childhood, sickle cell disease can present later in life, as evidenced by the 22-year-old male patient presenting with joint pain and anemia. This underscores the importance of considering sickle cell disease in adults presenting with features of sickle cell disease as a differential diagnosis. Timely recognition and management of sickle cell disease are crucial to prevent complications and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the patient and his family, and the internal medicine department of Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital.

Abbreviations

- PITC

Provider initiated Testing and Counseling

- PLT

Platelets

- RBC

Red blood cell

- SCD

Sickle cell disease

- SCT

Sickle cell trait

- WBC

White blood cell

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and writing of the case reports.

Funding

This study had no funding.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available in supplemental materials.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Renedo A, Miles S, Chakravorty S, Leigh A, Jo W, Marston C. Understanding the health-care experiences of people with sickle cell disorder transitioning from paediatric to adult services: this sickle cell life, a longitudinal qualitative study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2020. 10.3310/hsdr08440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017. 10.1056/NEJMra1510865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Report C. Clinical images and medical case reports sickle cell disease - Impact of delayed diagnosis and non compliance to treatment. 2023;

- 4.Claeys A, Steijn S Van, Kesteren L Van, Damen E, Akker M Van Den. Case series varied age of first presentation of sickle cell disease: case presentations and review. 2021;2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Thomson AM, McHugh TA, Oron AP, Teply C, Lonberg N, Vilchis Tella VM, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000–2021: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(8):e585–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiyaga C, Hernandez AG, Ssewanyana I, Mcelhinney KE, Ndeezi G, Howard TA, et al. Building a sickle cell disease screening program in the Republic of Uganda: the Uganda sickle surveillance study (US3) with 3 years of follow-up screening results. Blood Adv. 2018;2(November):4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Id SN, Id RM, Id SN, Among G, Id MS. Prevalence of sickle cell trait and needs assessment for uptake of sickle cell screening among secondary school students in Kampala. PLoS ONE. 2024;29:1–16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0296119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma A, Gaur K, Tiwari VP, Shukla S. Sickle cell disease presenting in the third trimester of pregnancy: delayed detection heralding a public health problem? Indian J Public Health. 2020. 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_223_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmanuel E, Centre FM, Elendu C, Amosu O. Socioeconomic status as a determinant of delayed diagnosis of sickle cell disease - A case report of newly diagnosed sickle cell disease in a 52-year-old woman. 2023;(April).

- 10.Hernandez AG, Kiyaga C, Howard TA, Ssewanyana I, Ndeezi G, Aceng JR, et al. Trends in sickle cell trait and disease screening in the Republic of Uganda, 2014–2019. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(1):23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ndeezi G, Kiyaga C, Hernandez AG, Munube D, Howard TA, Ssewanyana I, et al. Burden of sickle cell trait and disease in the Uganda sickle surveillance study (US3): a cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Heal. 1949;4(3):e195-200. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obaro S. Is integrating sickle cell disease and HIV screening logical ? Lancet Glob Heal. 2016;4(3):e144-5. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available in supplemental materials.