Abstract

Purpose

In this first-in-human dose escalation study, the safety and efficacy of IO-108, a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2 (LILRB2), was investigated in patients with advanced solid tumors as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab, an anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) antibody.

Methods

The study included patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced and relapsed solid tumors, with measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) V.1.1. Patients were treated with escalating doses of IO-108 every 3 weeks (Q3W) as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab. Safety and tolerability were the primary objectives. Secondary and exploratory objectives included: pharmacokinetics, clinical efficacy, immunogenicity and biomarkers.

Results

Of 25 patients enrolled, 12 were treated with IO-108 monotherapy and 13 received combination therapy. IO-108 was well-tolerated up to the maximally administered dose of 1,800 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W) as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab. No dose-limiting toxicity was observed, and a maximum tolerated dose was not reached. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurred in 6 (50.0%) patients treated with IO-108 monotherapy and 6 (46.2%) patients treated with IO-108+pembrolizumab. All TRAEs were mild or moderate (Grade 1 or 2), and no TRAEs led to treatment discontinuation or death. IO-108 exhibited a dose-proportional increase in exposure. Full receptor occupancy (RO) in peripheral blood was achieved at doses ≥600 mg. The overall response rate was 9% (1/11) in the monotherapy and 23% (3/13) in the combination therapy. A patient with treatment-refractory Merkel cell carcinoma treated with IO-108 monotherapy achieved a durable complete response (CR) for more than 2 years. Pharmacodynamic gene expression changes reflecting increased tumor infiltration of T cells were associated with clinical benefits in both monotherapy and combination therapy. Additionally, baseline tumor inflammation gene signature (TIS) scores correlated with clinical benefit.

Conclusion

IO-108 is well tolerated and has led to objective response as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab. The complete response and the pharmacodynamic changes in the monotherapy cohort demonstrate single agent activity of IO-108 and provide proof of concept that targeting myeloid-suppressive pathways through LILRB2 inhibition may potentiate the clinical efficacy of anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Biomarker, Immune modulatory, Immunotherapy, Monoclonal antibody, Solid tumor

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2 (LILRB2) inhibitory receptor is an emerging immune checkpoint in myeloid cells, and LILRB2 antagonism was shown to re-program tumor myeloid cells to become immune stimulatory in preclinical studies.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The early clinical data presented here suggest single agent activity of IO-108 and provide initial proof of concept that targeting myeloid-suppressive pathways through LILRB2 inhibition might be efficacious in treating human cancers.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study has a broad influence on the clinical development of therapeutic LILRB2 inhibitors.

Introduction

The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies against programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) or its ligand, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), has improved outcomes in patients with advanced malignancies.1 However, despite these advances, with the exception of certain indications such as melanoma, their efficacy remains limited in most cancer types with a small subset of patients achieving durable responses. Novel immunotherapy approaches targeting different immune-regulatory pathways in the tumor microenvironment (TME) are needed to improve clinical outcomes.2

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) represent the most abundant innate immune cell population in tumors.3 TAMs support cancer cell growth, metastasis and mediate immunosuppressive effects on the adaptive immune cells of the TME. The presence of TAMs is generally associated with poor prognosis in solid tumors, and they are also known to suppress responses to standard-of-care therapeutics, including checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and angiogenesis inhibitors.4

Macrophages display remarkable plasticity. Within the TME, their intrinsic plasticity enables macrophages to perform a variety of functions in response to environmental cues. In most cases, the suppressive milieu in the TME shapes them to become immune suppressive instead of immune-activating macrophages.5 The plasticity of macrophages is also the basis for developing therapeutic interventions to block inhibitory signaling in myeloid cells and convert suppressive TAM to activating macrophages.

Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2 (LILRB2), also known as immunoglobulin-like transcript 4, is a member of the LILRB family of immune inhibitory receptors. LILRB2 is primarily expressed in myeloid cell lineages: monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and neutrophils. LILRB2 was shown to be expressed in TAM in tumors and LILRB2 blockade induces a proinflammatory phenotype in tumor macrophages.6

LILRB2 has multiple ligands (HLA-G, ANGPTL2, SEMA4A and CD1c/d), several of which are known to contribute to the immunosuppressive microenvironment in solid tumors.7,13 In addition to Human Leukocyte Antigen-G (HLA-G), LILRB2 was also shown to interact with classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I molecules including HLA-A and HLA-B.14 15 Classical MHC I is widely accessible for LILRB2 because of their ubiquitous and abundant expression in all nucleated cells, thus it is plausible that LILRB2 interaction with MHC I molecules may negatively regulate immune activation in the TME.

In published preclinical studies,6 16 two anti-LILRB4 antibodies were independently shown to have combined effects with anti-PD-1 in potentiating T-cell activation in mixed leukocyte reactions. In a human tumor ex vivo histoculture,16 LILRB2 blockade (as monotherapy and in combination with PD-1 blockade) promoted the interferon (IFN)-γ gene signature score. Additionally, LILRB2 blockade in combination with anti-PD-1 reduced tumor burden in humanized NSG-SGM3 mice bearing-A549 tumors as well as in human LILRB2-transgenic mice bearing-Lewis lung carcinoma tumors.6

IO-108 is a recombinant monoclonal antibody of the human immunoglobulin G4 subclass that specifically binds to LILRB2 without cross-reactivity with other family members. Our unpublished preclinical data showed that IO-108 binds LILRB2 expressed on monocytes, macrophages, DCs and neutrophils as well as tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells from patients with cancer. IO-108 blocked LILRB2 interaction with multiple known ligands including HLA-G, SEMA4A and ANGPTL2. In agreement with published functional data about LILRB2 blockade, IO-108 induced macrophages in vitro to exhibit enhanced inflammatory and stimulatory responses to innate agonists. Additionally, IO-108 promoted a proinflammatory phenotype of monocyte-derived DCs and enhanced T-cell activation in co-culture experiments with patient-derived myeloid cells. Thus, the collective preclinical evidence supports that LILRB2 is a significant negative regulator in myeloid cells, and IO-108 is able to activate tumor myeloid cells leading to enhanced T-cell activation (manuscript in preparation, 2024).

Here we report safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), immunogenicity, efficacy, and biomarker data from the phase I dose escalation trial of IO-108 as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Methods

Study design

This is a first-in-human, multicenter, open-label, dose-escalation phase I trial (online supplemental file 1). The study evaluated the safety, PK, immunogenicity, clinical efficacy and biomarkers of intravenously administered IO-108 as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with solid tumors that failed prior therapies. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki; the protocol (IO-108-CL-001) was approved by the institutional review boards or ethics committees of all participating sites. All patients provided written informed consent to participate before enrollment.

Patients participating in a monotherapy cohort who developed disease progression were permitted to crossover to combination therapy with IO-108 and pembrolizumab. The decision to crossover was left to the discretion of the investigator and required authorization from the sponsor.

Patient population

Patients were at least 18 years old and had histologically or cytologically confirmed metastatic solid tumors with measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) V.1.1. Eligibility criteria required an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, measurable disease per RECIST V.1.1, baseline tumor biopsy (newly collected) and adequate organ function. Key exclusion criteria included previous treatment with an anti-LILRB2 or treatment with anticancer medication ≤4 weeks or ≤5 half-lives prior to IO-108 administration. Radiotherapy within 2 weeks prior to the first dose of IO-108 was exclusionary. The exclusionary conditions also included symptomatic central nervous system (CNS) metastasis, history of severe immune-related AEs from any prior immunotherapy, known hypersensitivity to any of the components of the IO-108 formulation or pembrolizumab or clinically significant conditions, such as active infections or cardiovascular diseases.

Treatment

The starting dose of 60 mg IO-108 was based on the Minimum Anticipated Biological Effect Level and was derived from in vitro dose-response assessment of RO of IO-108 in human whole blood. Monotherapy dose-escalation of 60 mg, 180 mg, 600 mg and 1,800 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W) was based on the modified toxicity probability interval (mTPI) method17 and the analysis of dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). The mTPI method targeted a DLT rate of 20% and applied an equivalence interval of 15%–25% for estimating the maximal tolerable dose during the IO-108 monotherapy dose-escalation phase. Combination dose-escalation of IO-108 from 180 mg to 600 mg and 1,800 mg Q3W (each with pembrolizumab 200 mg Q3W) followed a similar mTPI methodology as IO-108 monotherapy and was initiated after the first two IO-108 monotherapy dose levels (60 mg and 180 mg) had cleared the DLT period for safety. All patients were treated with the study drug(s) until disease progression (PD), unacceptable adverse events (AEs), patient or investigator decision to withdraw from participation, or completing 2 years of treatment duration.

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the safety and tolerability of IO-108 as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the PK of IO-108 as monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab, to evaluate for anti-drug (IO-108) antibodies (ADA) that reflect immunogenicity of IO-108, and to assess preliminary antitumor activity. The remaining objectives were to explore pharmacodynamic effects potentially indicative of clinical response or resistance, or mechanism of action of IO-108 as well as to identify baseline characteristics that may correlate with clinical activity.

Safety assessment

Safety and tolerability were assessed by incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs), the incidence of study drug discontinuation due to TEAEs and DLTs according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), V.5.0 (v5.0). The DLT evaluation period for IO-108 as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab was the first 21 days from Cycle 1 day 1. The development of any AEs was carefully monitored throughout the study from the signing of the informed consent to 30 days after the last dose of IO-108 or pembrolizumab. All AEs were graded using the NCI CTCAE V.5.0 grading system.

Clinical assessment

High-resolution computed tomography (CT) with contrast, or contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were used for assessing radiographic tumor response. Antitumor activity was measured by objective response rate (ORR) that was determined by RECIST V.1.1. Imaging assessments were performed at baseline during screening and at Cycle 3 day 1 (C3D1). After C3D1, tumor imaging assessments were performed every 6 weeks. Beyond the first year of study, disease assessments were conducted every 9 weeks while on active treatment.

Pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity and target engagement

Multiple serum samples were collected for PK assessment after the first dose during Cycle 1, followed by collection before and at the end of infusions for subsequent selective dosing cycles, and approximately 30 days after the last dose. A validated ELISA with a lower limit of qualification of 31.25 ng/mL was used to determine serum IO-108 concentrations. The preliminary PK assessment was performed through the use of the standard non-compartmental analysis method and the computer software Phoenix WinNonlin, V.8.0 (Certara USA, 100 Overlook Center, Suite 101, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 USA). Nominal dosing and nominal blood sampling times were used.

Serum samples for ADA analysis were obtained at baseline (pretreatment) and at multiple pre-dose time points on active treatment. A bridging electrochemiluminescence assay was validated to detect antibodies to IO-108 in human serum. The prevalence of ADAs at baseline was calculated by dividing the total number of patients in all study groups that tested positive for ADA at baseline by the total number of patients with a valid ADA test result at baseline. The incidence of ADAs post-baseline is the combination of treatment-induced (ie, they were ADA negative at baseline for ADA analysis) and treatment-enhanced ADAs (ie, they were ADA positive at baseline for ADA analysis).

A flow cytometry-based assay that measures unoccupied LILRB2 on peripheral blood myeloid cells (CD33+CD11b+) was used to measure RO. A fluorochrome‐labeled IO-108 antibody was used to detect unoccupied LILRB2 in whole blood samples.

The RO was calculated according to the following formula:

% RO=100 – (MOEFpost-dose sample / MOEFpre-dose sample) × 100%

Molecules of equivalent fluorescence (MOEF) was calculated by geometric mean fluorescence intensity values minus FMO (fluorescence minus one). Post-dose sample: samples collected after the first dose; pre-dose sample: samples collected before the first dose.

Biomarkers assessment

A total of 37 tumor biopsy samples were collected. Among them, there were 22 pretreatment samples and 15 post-treatment samples collected at day 8 of Cycle 2 treatment (C2D8). The tissues were subsequently formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE). PD-L1 protein expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) using PD-L1 pharmDx (Agilent) performed at Discovery Life Sciences.

NanoString profiling was performed at Canopy. RNA was extracted from tumor tissue on FFPE sides using Roche High Pure FFPE RNA and Qiagen RNeasy FFPE kits, as per-protocols. The quality and quantity of isolate RNA were determined by A260/A280 measurements with a NanoDrop. Approximately 100 ng of total RNA were run on the Human IO360 Panel Plus (Human IO360 Panel+PLS_Bruker_622) per the manufacturer’s recommendation. The Human IO360 Panel Plus includes probes for the IO-360 panel plus an additional 28 genes provided by Immune-Onc. Data analysis was performed using the nSolver V.4.0 analysis software from NanoString.

NanoString analyses were performed in the R language for statistical computing, V.4.3.1.18 Linear modeling was performed with the limma package.19 Graphics were created with the ggplot2 package.20

Sample processing, quality control, and normalization: NanoString samples marked as failed by the vendor were removed from the analysis. For the remaining samples, housekeeping probe selection was performed with the NormqPCR package.21 The geometric mean of housekeeping genes was used to derive normalization factors. Normalized data were then log2(x+1) transformed.

Linear modeling: a set of related linear models were created that included fixed effects of treatment (H, IO-108 monotherapy vs IO-108+anti-PD-1 combination therapy), time point (T, screening/pretreatment vs Cycle 2 day 8 samples), and therapeutic benefit (B), were created and evaluated in a fully-crossed design with the limma package.19 Intrasubject variability (S) was treated as a random effect.

In the first model, therapeutic benefit (B) compared disease control (including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and stable disease (SD)) to PD. A second model added additional detail about the therapeutic benefit, comparing objective response (CR and PR), SD, and PD. Finally, the effects of overall immune infiltrate levels in tumor samples were modeled by the addition of CD45 expression to the model.

For multiple testing adjustment of calculated p values, the false discovery rate of Benjamini and Hochberg was used.22

Results

Patients and baseline demographics

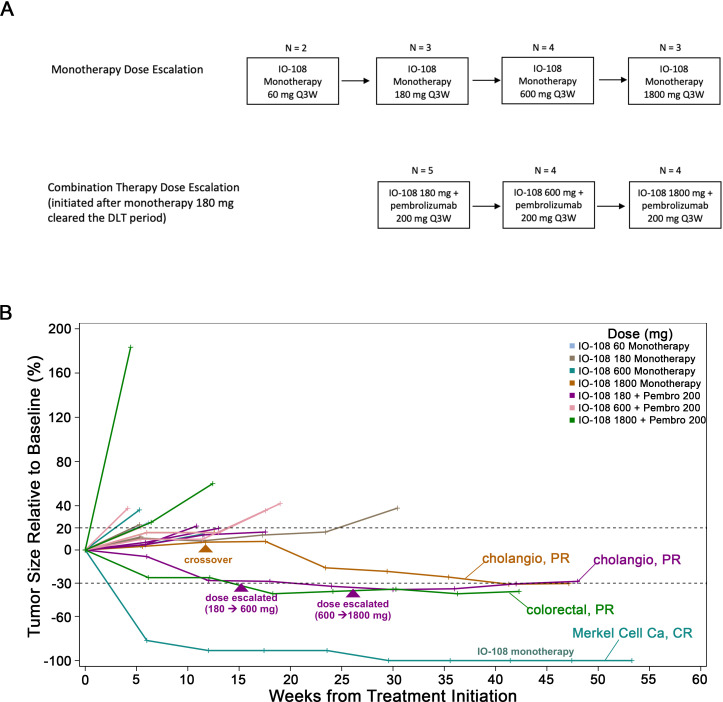

Between September 30, 2021, and May 25, 2022, 25 patients were enrolled and treated in the dose escalation phase of the trial with 12 patients treated with IO-108 monotherapy and 13 patients with 1O-108 in combination with pembrolizumab (figure 1A). The clinical characteristics and baseline demographics of the study patients are summarized in table 1 and online supplemental table 1, respectively. All patients received prior systemic anticancer therapy. Patients in the monotherapy cohorts received a median of 4.5 prior lines of therapy (range of 2–6), and patients in the combination cohorts received a median of 3 prior lines of therapy (range of 2–4, table 1).

Figure 1. Clinical trial design and outcomes. (A) Dose escalation diagram. (B) Percentage of target lesion change over time (RECIST V.1.1) in patients who received IO-108 monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab. Patients with objective responses (CR, PR) are marked on their respective curves. One intrapatient escalation (IO-108+pembrolizumab) indicated in purple triangles: the partial response was detected after escalation to 600 mg of IO-108 and lasted for 11+months. RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumours; CR, complete response; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; PR, partial response; Q3W, every 3 weeks.

Table 1. Patients baseline characteristics.

| IO-108 monotherapy | IO-108+pembrolizumab | Total | |

| N=12 | N=13 | N=25 | |

| Age, median (range), years | 54 (26–79) | 66 (54–71) | 66 (26–79) |

| Sex, F/M, n | 9/3 | 6/7 | 15/10 |

| ECOG PS, n | |||

| 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| 1 | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| # of prior lines of Tx | Median 4.5 | Median 3.5 | Median 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 3 or greater | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| Previous anti-PD-(L)1 Tx. (%) | 4 (33) | 6 (46) | 10 (40) |

| Tumor types(MSS status if known) | Colorectal adenocarcinoma (MSS) | 8 | |

| Colorectal neuroendocrine cancer (MSS) | 1 | ||

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 5 | ||

| Cholangiocarcinoma (MSS) | 2 | ||

| Merkel Cell Ca., Ovarian ca., Bladder ca., H&N ca., Appendiceal ca., Adrenocortical ca., Breast ca., ccRCC, Unknown primary ca | 9 | ||

ECOG PSEastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance statusMSSmicrosatellite stable PD-L1programmed death ligand 1 RECISTResponse Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors Txtreatment

In the monotherapy cohorts, patients were treated with IO-108 in ascending doses of 60 mg (n=2), 180 mg (n=3), 600 mg (n=4) and 1,800 mg (N=3) Q3W intravenously. In the combination cohorts, patients were treated with IO-108 in ascending doses of 180 mg (n=5), 600 mg (n=4) and 1,800 mg (n=4) in combination with pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously Q3W (figure 1A). One patient from the monotherapy cohorts treated with IO-108 1,800 mg crossed over to the combination cohorts upon radiological confirmation of the PD to receive the combination of IO-108 1,800 mg and pembrolizumab 200 mg (figure 1B).

At the data cut-off of January 27, 2023, the median treatment duration was 46.5 days (range of 42.0–159.5 days) with 42% of patients receiving ≥4 doses of IO-108 as monotherapy. Patients treated with the combination of IO-108 and pembrolizumab had a median treatment duration of 89.0 days (range of 42.0–133.0 days) with 62% of patients receiving ≥4 doses of investigational therapy.

Safety

The safety data are available for all 25 patients that were enrolled. 12 patients (100.0%) in IO-108 monotherapy dose escalation and 12 out of 13 patients (92.3%) in IO-108+pembrolizumab dose escalation experienced TEAEs (table 2). The most common (>30%) TEAEs in IO-108 monotherapy were increased aspartate aminotransferase (41.7%), increased alanine aminotransferase (33.3%) and myalgia (33.3%). In patients treated with the combination of IO-108+pembrolizumab the most common TEAEs were ascites (30.8%), diarrhea (30.8%), and fatigue (30.8%).

Table 2. Summary of adverse events.

| AE, n (%) | IO-108 MonotherapyN=12 | IO-108+PembrolizumabN=13 |

| Any grade treatment-emergent AE | 12 (100) | 12 (92.3) |

| Grade 3–5 | 3 (25.0) | 8 (61.5) |

| Led to discontinuation | 1 (8.3) | 2 (15.4) |

| Serious adverse events | 1 (8.3) | 8 (61.5) |

| Serious and led to treatment discontinuation | 1 (8.3) | 2 (15.4) |

| Led to death | 0 | 2 (15.4) |

| Any grade treatment-related AE | 6 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) |

| Grade 3–4 TRAE | 0 | 0 |

| TRAE led to discontinuation | 0 | 0 |

| Serious TRAE | 0 | 0 |

| Serious TRAE and led to discontinuation | 0 | 0 |

| Led to death | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-related AEs in two or more patients in any cohort | ||

| Myalgia | 3 (25.0) | 1 (7.7) |

| Pruritus | 2 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 2 (15.4) |

AEadverse eventTRAEtreatment-related adverse events

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) occurred in 6 (50.0%) patients treated with IO-108 monotherapy and 6 (46.2%) patients treated with IO-108+pembrolizumab. All TRAEs were mild or moderate (Grade 1 or 2) (table 2). No patients experienced serious TRAEs, nor did TRAEs lead to treatment discontinuation or death. The most common (two or more events) TRAEs reported with IO-108 monotherapy were: myalgia (25.0%) and pruritus (16.7%); IO-108+pembrolizumab were: pruritus (15.4%) and diarrhea (15.4%).

Overall, IO-108 was well tolerated in patients treated with IO-108 monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab. No SAEs or deaths were related to IO-108 administration. No DLTs were reported, and a maximum tolerated dose (an MTD) was not reached at the pre-planned highest dose (1,800 mg). No safety concerns have been identified and the safety profile of IO-108 supports continuation of the clinical development of IO-108.

Pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity and target engagement

IO-108 had comparable PK profiles between monotherapy and combination therapy with pembrolizumab (online supplemental figure 1A). IO-108 exhibited a dose-proportional increase in exposure: (1) the maximum observed concentration; (2) the area under the concentration versus time curve from 180 mg to 1,800 mg (online supplemental table 2). The accumulation ratio for trough concentration is less than 1.5, suggesting a mild accumulation of IO-108 with a Q3W administration schedule. At doses ≥600 mg, the estimated mean half-life (t1/2) ranges from 11 to 15 days (online supplemental table 2).

IO-108 immunogenicity assessment is ongoing. The baseline prevalence of ADAs was 16% in the overall study population (4/25 patients). The preliminary incidence of ADAs was determined to be 21.7% (five out of 23) that included treatment enhanced ADA (13%, three out of 23) or treatment induced ADA (8.7%, two out of 23). However, these ADAs had no impact on the overall exposure of IO-108.

LILRB2 RO was evaluated in whole blood samples collected before the first dose and at several time points post-treatment during the first treatment cycle. Full RO has been achieved at 600 mg and 1,800 mg dose levels for the entire duration of the first cycle (online supplemental figure 1B). The half-life (t1/2) and RO data support an IO-108 dosing interval of Q3W at ≥600 mg.

Efficacy

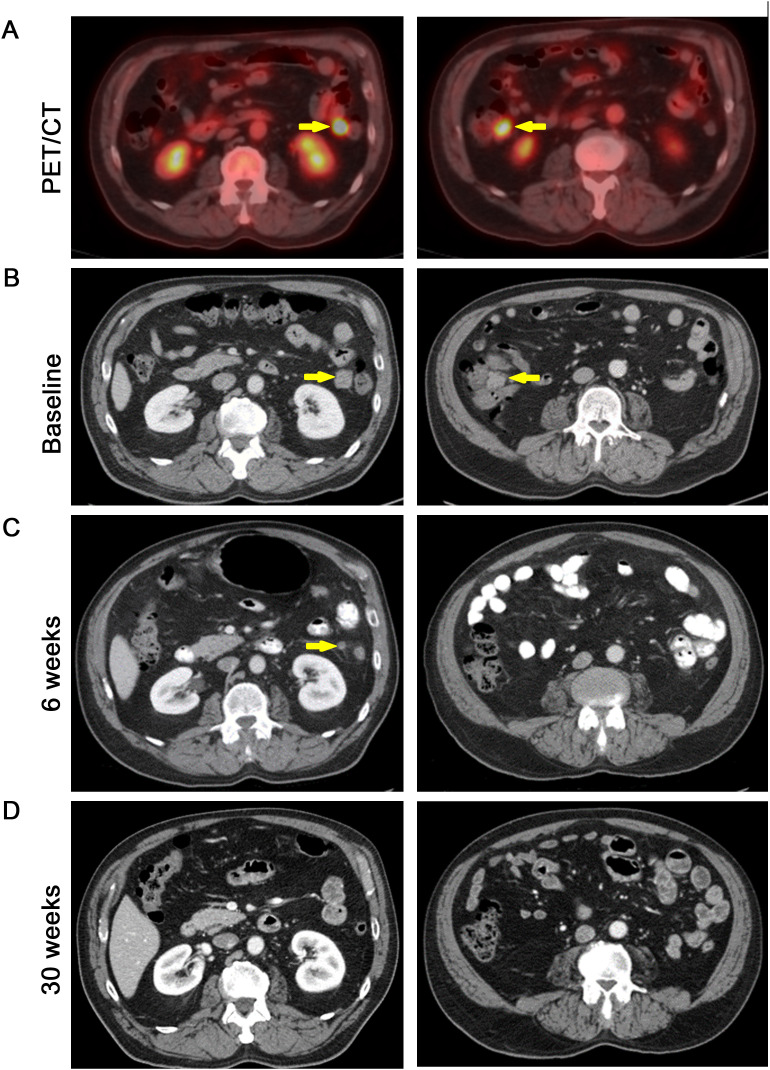

Among the 11 efficacy evaluable patients in the monotherapy cohorts, one patient with Merkel cell carcinoma (positive for Merkel cell polyoma virus; online supplemental figure 2) achieved a CR on IO-108 treatment (figure 1B). This patient was previously treated with surgical resection of the primary lesion followed by adjuvant radiotherapy. He subsequently developed distant metastases and was treated with pembrolizumab. At the time of disease progression (PD), he was treated with ipilimumab/nivolumab in addition to palliative radiation therapy. After further PD (figure 2), he was enrolled in the IO-108 monotherapy cohorts. The first dose of IO-108 was given 82 days after his last dose of nivolumab. The patient achieved an 82% reduction in the size of target lesions (mesenteric metastases) after only 6 weeks on IO-108. At 30 weeks, he achieved a CR which has remained durable for more than 2 years (figures1B 2).

Figure 2. Evidence of antitumor activity in IO-108 monotherapy. A patient with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (positive for Merkel cell polyoma virus) had disease progression through two lines of cancer immunotherapy before enrollment in the IO-108 clinical trial. PET/CT (18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose) scan showing mesenteric metastases (arrows) (A). CT images of the patient at baseline (B), 6 weeks (C) and 30 weeks (D) after IO-108 monotherapy. The arrows denote disappearing target lesions (mesenteric metastases). CT: computed tomography; PET: positron emission tomography.

In the monotherapy cohorts, four patients achieved SD, two of which were microsatellite stable (MSS) colorectal cancers. It is worth noting that four out of five patients with the best overall responses of CR and SD in the monotherapy arm received IO-108 at dose levels of ≥600 mg (one patient with SD was treated at the 180 mg dose level). The patient with Merkel cell carcinoma who achieved a CR was treated with 600 mg of IO-108 alone and the patient with cholangiocarcinoma who crossed over to the combination therapy cohorts was initially treated with 1,800 mg of IO-108 as a single agent and developed SD.

Among 13 efficacy evaluable subjects treated with the combination of IO-108 plus pembrolizumab, three subjects (23.1%) achieved a PR, and four subjects (30.8%) had SD (table 3). All three patients with an objective response remained on study treatment for 8–12+ months (figure 1B). One patient with cholangiocarcinoma initially had the best overall response of SD and then became a PR after crossing over to the combination therapy (figure 1B). The other two patients who achieved PRs included a patient with colon cancer (neuroendocrine type; treated with IO-108 at 1,800 mg and pembrolizumab 200 mg) and a patient with cholangiocarcinoma who was treated initially with IO-108 at 60 mg and subsequently escalated to 1,800 mg in combination with pembrolizumab (200 mg) (figure 1B). All three patients with objective responses were previously heavily treated with anticancer agents but were naïve to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Table 3. Summary of confirmed tumor response per RECIST V.1.1 by investigator assessment.

| IO-108 monotherapyN=12 | IO-108+pembrolizumabN=13 | |

| Efficacy evaluable, n | 11 | 12+1 crossover |

| ORR (%) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (23.1) |

| DCR (%) | 5 (45.5) | 7 (53.9) |

| CR | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) |

| PR | 0 (0) | 3 (23.1) |

| SD | 4 (36.4) | 4 (30.8) |

| PD | 6 (54.5) | 6 (46.1) |

| Not evaluable | 1 | 1 |

CRcomplete responseDCR, disease control rateORRobjective response ratePDdisease progressionPRpartial responseRECISTResponse Evaluation Criteria In Solid TumorsSDstable disease

Biomarkers

Pharmacodynamic changes after IO-108 monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab

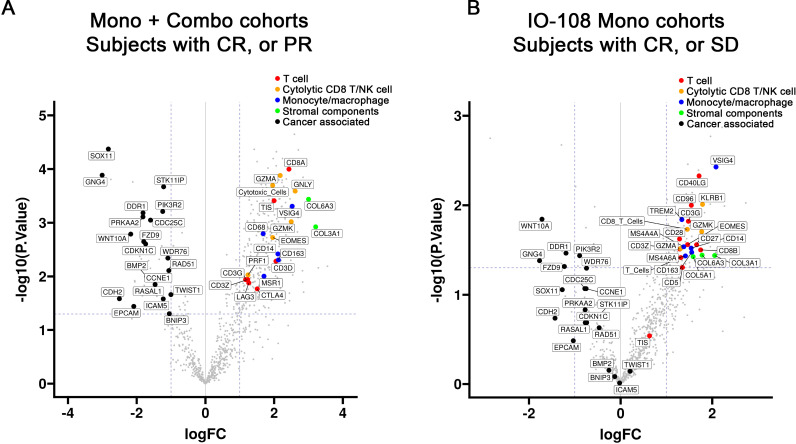

To investigate potential pharmacodynamic changes, pre-treatment versus post-treatment samples in subjects with objective responses (CR or PR) from the combined cohorts of monotherapy and combination therapy were analyzed. As shown in figure 3A, the pharmacodynamic gene expression changes in the responders include increased gene expression (relative to baseline) of T-cell markers and cytolytic markers of T and natural killer (NK) cells such as granulysin (GNLY). Tumor inflammation gene signature (TIS) score was also increased relative to baseline (figure 3A). In order to understand the IO-108 contribution to the above pharmacodynamic changes, we conducted a similar analysis for the monotherapy cohorts. For the IO-108 monotherapy cohort analysis, we compared subjects who achieved clinical benefit (CR or SD) with those who developed PD. As shown in figure 3B, a similar trend of upregulated gene expression of T cell and NK markers relative to baseline was observed after IO-108 treatment.

Figure 3. Pharmacodynamic gene expression changes. Volcano plots showing relative fold change (post vs pre) of messenger RNA for genes associated with T cells, myeloid cells, tumor cells and stromal cells. (A) objective responders (CR, PR) in the combined monotherapy and combination cohorts of all patients. (B) changes observed in patients with the objective response or stable disease from the monotherapy cohorts. The horizontal axes represent the log2 transformed fold changes (logFC). The vertical axes represent the −log10 transformed p values (unadjusted). The dotted lines denote p value=0.05 and twofold changes in gene expression. Colors indicate suggested classifications of lymphoid, myeloid, stromal and tumor-associated markers. CR, complete response; NK, natural killer; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

The aforementioned upregulated gene expression of T-cell markers appears to be associated with clinical responses, because samples from patients with PD did not reveal similar changes (online supplemental figure 3A,B). In contrast to the upregulated T-cell markers, transcripts of genes mostly associated with tumor cells were downregulated in responders such as discoidin domain receptor 1, G protein subunit gamma 4 and frizzled-9 (figure 3A,B).

Along with the gene expression changes in markers associated with T cells and tumor cells, markers of monocytes and/or macrophages, such as CD14 and VSIG4, as well as stromal components (collagens COL6A3 and COL3A1), were increased relative to baseline (figure 3A,B). An additional set of analyses tried to determine whether the pharmacodynamic changes observed could be explained by overall increases in immune infiltration, or changes in specific immune cell types. We extended our analysis model to try to remove the effect of overall immune cell levels by a normalization (regression) with CD45, a marker of all immune cells. As a result, the immune markers, including the markers of T cell, cytolytic CD8/NK cells and monocytes/macrophages, shown in figure 3A,B were reduced in the CD45 normalization (regression) analysis (online supplemental figure 3C,D), reflecting a general leukocyte infiltration on IO-108 treatment or IO-108 in combination with anti-PD-1.

Baseline tumor inflammation associated with clinical response

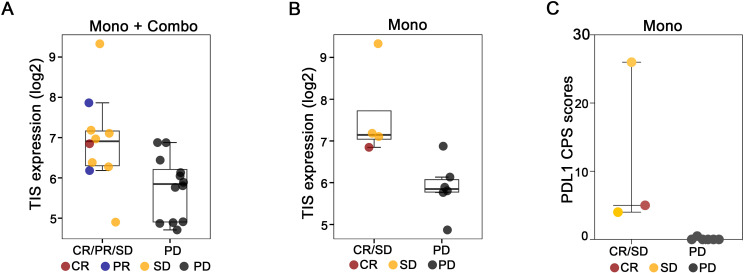

There was a total of 22 baseline tumor samples available for NanoString analysis, including 10 patients that received IO-108 monotherapy, and 12 patients treated with the combination of IO-108 and pembrolizumab. The analysis showed that baseline TIS signature scores were positively associated with clinical response in the combined monotherapy and combination cohorts (figure 4A). We also analyzed the TIS score in the monotherapy cohorts. Despite limited sample numbers in the monotherapy cohorts, there was a trend of correlation between TIS scores and clinical benefits (figure 4B).

Figure 4. Baseline tumor inflammation positively correlated with clinical benefits. Baseline TIS scores associated with the clinical responses in the combined monotherapy and combination cohorts (A), and associated with the clinical benefits in the IO-108 monotherapy cohorts (B). Boxes indicate the second and third quartile ranges of the data, with the center line indicating the median. The y-axes represent log2(n+1) transformed probe expression values. All markers shown passed nominal criteria of twofold change in expression and unadjusted p value<0.05. C, baseline PD-L1 immunohistochemistry combined positivity score (CPS) in IO-108 monotherapy cohorts. A p value<0.05 was calculated using an unpaired t-test. CR, complete response; PD, disease progression; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; TIS, tumor inflammation gene signature.

We also examined the relationship between pre-treatment expression of selected genes that are expressed in T cells or NK cells and therapeutic responses. Both TIGIT (T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains), a co-inhibitory receptor expressed in T cells and NK, and TNFRSF9 (CD137, 4-1BB), a co-stimulatory receptor expressed in T cells, showed a positive correlation with clinical benefits in the combined cohorts of monotherapy and combination therapy (online supplemental figure 4A) as well as in the IO-108 monotherapy cohorts (online supplemental figure 4B). GNLY, a pore-forming protein expressed in cytotoxic granules of CD8 T cells and NK cells, was also positively associated with benefit in the combined cohorts (online supplemental figure 4A) and monotherapy cohorts (online supplemental figure 4B). Among IFN-γ regulated markers, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9, a chemokine known to attract cytotoxic T cells,23 was correlated with the objective responses in the combined monotherapy and combination cohorts (online supplemental figure 4A) and the clinical benefits in the IO-108 monotherapy cohorts (online supplemental figure 4B).

To study the correlation between PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) and clinical response to IO-108, we performed PD-L1 IHC across baseline tumor samples in the IO-108 monotherapy cohorts. A trend of higher CPS score was observed in patients with the CR or SD (figure 4C).

Discussion

In this first-in-human phase I dose escalation trial, a heavily pretreated patient population with advanced solid tumors was treated with the anti-LILRB2 antibody IO-108. At dose levels ranging from 60 mg to 1,800 mg intravenously Q3W, IO-108 was well tolerated as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab. No SAEs or deaths were related to IO-108 administration and no DLT was reported in the study. An MTD was not reached through the pre-planned highest dose (1,800 mg). IO-108 exhibited a dose-proportional increase in exposure from 180 mg to 1,800 mg in the monotherapy and combination therapy cohorts. Full RO was achieved at 600 mg and 1,800 mg dose levels for the first treatment cycle. Of note, four of the five patients who achieved the best overall responses in the monotherapy cohorts received IO-108 at 600 mg or 1,800 mg.

Single-agent antitumor activity of IO-108 was observed in a patient with treatment-refractory Merkel cell carcinoma (positive for Merkel cell polyoma virus) who achieved a CR that is ongoing for over 2 years. This patient had previously been treated with pembrolizumab, ipilimumab/nivolumab and radiation therapy and had developed further disease progression. Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare, highly aggressive, neuroendocrine cutaneous tumor. Advanced Merkel cell carcinoma is known to respond to anti-PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint inhibitors24 25 with ORRs ranging from 33% to 56%. However, durable CRs are uncommon with these therapies in this patient population. The durable CR in the patient with Merkel cell carcinoma treated with IO-108 monotherapy suggests that more extensive evaluation of IO-108 therapy in patients with advanced Merkel cell carcinoma is needed.

IO-108 in combination with pembrolizumab demonstrated a 23% ORR (table 3). All three responders in the combination cohorts were naïve to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy but were heavily treated with other anticancer agents. Among the three patients with an objective response in the combination arm, one patient with cholangiocarcinoma was initially treated with IO-108 in a monotherapy cohort. When she developed a PD, she crossed over to the combination arm and subsequently achieved a PR. This observation suggests that the combination of IO-108 with anti-PD-1 was necessary to achieve an objective response in this patient. Preclinical studies also provided evidence that LILRB2 blockade enhanced immune responses of T-cell immune checkpoint inhibitors.6 16 Collectively, the evidence suggests that combined blockade of LILRB2 and PD-1 may generate more effective antitumor immune responses.

In the NanoString-based transcriptional analysis of pharmacodynamic changes, we observed increased post-treatment CD8+ T cell and NK cell markers relative to baseline that correlated with clinical efficacy (figure 3). In contrast, transcripts associated with tumor cells were downregulated relative to baseline in patients who experienced clinical benefit. The relative increase of immune cell and decrease of tumor cell RNA markers relative to baseline due to treatment has been reported previously in other immunotherapy trials.26 It is plausible that activated immune cells, particularly activated cytolytic CD8+ T cells, are killing and removing tumor cells in responding patients, consistent with the mechanism of action of anti-LILRB2 and anti-PD-1 therapies.

In a search for immune cell subtypes specifically enriched in post-treatment samples, we attempted to remove the effect of overall immune infiltrate by normalizing RNA expression through the pan-immune marker CD45. We found that after CD45 normalization, the specific pharmacodynamic changes of leukocyte subtypes were largely absent, suggesting that the treatment promoted a general immune cell infiltration into tumors. Altogether, the dynamic immune microenvironment changes observed in the study support the clinical efficacy observed with IO-108 monotherapy and IO-108/anti-PD-1 combination therapy.

Figure 3A,B illustrate other pharmacodynamic changes: (1) upregulated myeloid genes relative to baseline, especially those expressed in macrophages and/or monocytes, such as CD14 and VSIG4; (2) upregulation of stromal components (collagens COL6A3 and COL3A1) relative to baseline. These pharmacodynamic changes were observed in both monotherapy and combination cohorts. This could be a general property of enhanced infiltration of certain myeloid populations and fibroblast-mediated tissue remodeling following immune activation in TME induced by cancer immunotherapy.27

We also analyzed baseline gene expression to correlate with clinical response or benefit. TIS is an 18-gene signature that measures a pre-existing but suppressed adaptive immune response within tumors. High baseline TIS scores have been shown to positively correlate with the clinical response in multiple studies evaluating anti-PD (L)-1 cancer immunotherapy.28 We found that the baseline TIS scores were correlated with clinical efficacy in subjects treated with IO-108 monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab. The association of baseline TIS scores with the IO-108 clinical response is consistent with what was reported from the phase I study of MK-4830 (anti-LILRB2 monoclonal antibody) in combination with pembrolizumab.29 The collective evidence suggests that anti-LILRB2-based therapy benefits patients with higher T-cell tumor infiltration, and that IO-108-based therapy can overcome some myeloid-driven resistance mechanisms in the TME to enhance T-cell mediated antitumor responses.

PD-L1 IHC assays are approved as companion diagnostics for immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors in several tumor types, and PD-L1 CPS or tumor proportion score is a way to assess baseline tumor inflammation.30 Despite the limited sample numbers in the monotherapy cohorts, a trend of higher CPS scores was observed in patients who experienced clinical benefit from treatment with IO-108 monotherapy.

The limitations of this study include the small number of patients, the heterogeneous cancer types in the patient population, and the various dose levels of IO-108 (as is required for dose escalation trials). These shortcomings will be overcome in dose expansion cohort studies by evaluating adequate exposure in more homogenous populations. In spite of the limitations, it is worth noting that these patients were heavily pretreated with anticancer agents, and some of them were treated with T-cell immune checkpoint inhibitors prior to participation in the IO-108 trial. Moreover, most cancer patients in the study had less-immunogenic cancer types such as pancreatic cancers and MSS colorectal cancers for which immunotherapy is not a standard of care. Nevertheless, one CR was observed in the monotherapy arm in a patient who had developed resistance to T-cell immune checkpoint inhibitors, and three patients in the combination arm achieved objective responses, notably all three with MSS tumors.

In summary, IO-108 was well tolerated and demonstrated clinical benefit as a monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Preliminary baseline biomarker studies suggest a possible role for predictive biomarkers that may facilitate improved patient selection in subsequent clinical trials. The early clinical data support further development of IO-108 in combination with other anticancer immunotherapies in patients with advanced cancers.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients, their families and site personnel for participating in this study. The authors also thank John Bergan for providing regulatory guidance, Roya Nawabi for managing clinical operations, and Penny Dong for project and alliance management.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was sponsored by Immune-Onc Therapeutics, Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involved human participants. Multiple committees and IRBs were involved. The trial protocol and amendments were approved by an independent ethics committee for each trial site, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. Information below is specific to each institute’s IRB: (1) Name of the ethics committee: Advarra for Earle A. Chiles Research Institute, Providence Cancer Institute (ID# Pro00056066). (2) Name of the ethics committee: Advarra for Carolina BioOncology Institute, Huntersville (ID# Pro00056066). (3) Name of the ethics committee: WCG IRB for Florida Cancer Specialists/Sarah Cannon Research Institute (ID# 20215021). (4) Name of the ethics committee: Office of Human Subject Protection for MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas (ID# 2021-0614).

Contributor Information

Matthew H Taylor, Email: matthew.taylor@providence.org.

Aung Naing, Email: anaing@mdanderson.org.

John Powderly, Email: jpowderly@carolinabiooncology.org.

Paul Woodard, Email: woodardp4072@gmail.com.

Luke Chung, Email: Lukechung2006@yahoo.com.

Wen Hong Lin, Email: wenhong.lin@immuneonc.com.

Hongyu Tian, Email: hongyu.tian@immuneonc.com.

Nathan Siemers, Email: nosmicrosoft@fiveprime.org.

Hong Xiang, Email: hong.xiang@immuneonc.com.

Rong Deng, Email: rongdengub05@gmail.com.

Kyu Hong, Email: kyu.hong@immuneonc.com.

Donna Valencia, Email: donna.valencia@immuneonc.com.

Tao Huang, Email: tao.huang@immuneonc.com.

Ying Zhu, Email: ying.zhu@immuneonc.com.

X Charlene Liao, Email: charlene.liao@immuneonc.com.

Xiao Min Schebye, Email: xiaomin.schebye@immuneonc.com.

Manish R Patel, Email: mpatel@flcancer.com.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Xiang Z, Li J, Zhang Z, et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of Anti-PD-1, Anti-PD-L1, Anti-CTLA-4 and Their Combined Immunotherapy in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:883655. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.883655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh RJ, Sundar R, Lim JSJ. Immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations-current and emerging strategies. Br J Cancer. 2023;128:1415–7. doi: 10.1038/s41416-023-02181-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christofides A, Strauss L, Yeo A, et al. The complex role of tumor-infiltrating macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:1148–56. doi: 10.1038/s41590-022-01267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeNardo DG, Ruffell B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:369–82. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin T, Li X, Li Y, et al. Macrophage plasticity and function in cancer and pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1333549. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1333549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H-M, van der Touw W, Wang YS, et al. Blocking immunoinhibitory receptor LILRB2 reprograms tumor-associated myeloid cells and promotes antitumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:5647–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI97570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agaugué S, Carosella ED, Rouas-Freiss N. Role of HLA-G in tumor escape through expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and cytokinic balance in favor of Th2 versus Th1/Th17. Blood. 2011;117:7021–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben Amor A, Beauchemin K, Faucher MC, et al. Human Leukocyte Antigen G Polymorphism and Expression Are Associated with an Increased Risk of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Advanced Disease Stage. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He J, Xu J, Yu X, et al. Overexpression of ANGPTL2 and LILRB2 as predictive and therapeutic biomarkers for metastasis and prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11:2281–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyer AS, Chapoval SP. Neuroimmune Semaphorin 4A in Cancer Angiogenesis and Inflammation: A Promoter or a Suppressor? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;20:124. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D, Wang L, Yu L, et al. Ig-like transcript 4 inhibits lipid antigen presentation through direct CD1d interaction. J Immunol. 2009;182:1033–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li D, Hong A, Lu Q, et al. A novel role of CD1c in regulating CD1d-mediated NKT cell recognition by competitive binding to Ig-like transcript 4. Int Immunol. 2012;24:729–37. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng J, Umikawa M, Cui C, et al. Inhibitory receptors bind ANGPTLs and support blood stem cells and leukaemia development. Nature New Biol. 2012;485:656–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colonna M, Samaridis J, Cella M, et al. Human myelomonocytic cells express an inhibitory receptor for classical and nonclassical MHC class I molecules. J Immunol. 1998;160:3096–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiroishi M, Tsumoto K, Amano K, et al. Human inhibitory receptors Ig-like transcript 2 (ILT2) and ILT4 compete with CD8 for MHC class I binding and bind preferentially to HLA-G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8856–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1431057100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umiker B, Hashambhoy-Ramsay Y, Smith J, et al. Inhibition of LILRB2 by a Novel Blocking Antibody Designed to Reprogram Immunosuppressive Macrophages to Drive T-Cell Activation in Tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023;22:471–84. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-22-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji Y, Liu P, Li Y, et al. A modified toxicity probability interval method for dose-finding trials. Clin Trials. 2010;7:653–63. doi: 10.1177/1740774510382799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Team RC . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wickham H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Use R!. 1 online resource (XVI, 260 pages 32 illustrations, 140 illustrations in color. 2nd. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer; 2016. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkins JR, Dawes JM, McMahon SB, et al. ReadqPCR and NormqPCR: R packages for the reading, quality checking and normalisation of RT-qPCR quantification cycle (Cq) data. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:296. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karin N. CXCR3 Ligands in Cancer and Autoimmunity, Chemoattraction of Effector T Cells, and Beyond. Front Immunol. 2020;11:976. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman HL, Russell JS, Hamid O, et al. Updated efficacy of avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma after ≥1 year of follow-up: JAVELIN Merkel 200, a phase 2 clinical trial. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:7. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0310-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2542–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji R-R, Chasalow SD, Wang L, et al. An immune-active tumor microenvironment favors clinical response to ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1019–31. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Wu C, Hu H, et al. Remodeling of the immune and stromal cell compartment by PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1152–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danaher P, Warren S, Lu R, et al. Pan-cancer adaptive immune resistance as defined by the Tumor Inflammation Signature (TIS): results from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:63. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0367-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siu LL, Wang D, Hilton J, et al. First-in-Class Anti-immunoglobulin-like Transcript 4 Myeloid-Specific Antibody MK-4830 Abrogates a PD-1 Resistance Mechanism in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:57–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doroshow DB, Bhalla S, Beasley MB, et al. PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:345–62. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.