Abstract

Background

Nemvaleukin alfa (nemvaleukin, ALKS 4230) is a novel, engineered cytokine that selectively binds to the intermediate-affinity interleukin-2 receptor, preferentially activating CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells, with minimal expansion of regulatory T cells, thereby mitigating the risk of toxicities associated with high-affinity interleukin-2 receptor activation. Clinical outcomes with nemvaleukin are unknown. ARTISTRY-1 investigated the safety, recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D), and antitumor activity of nemvaleukin in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Methods

This was a three-part, open-label, phase 1/2 study: part A, dose-escalation monotherapy, part B, dose-expansion monotherapy, and part C, combination therapy with pembrolizumab. The study was conducted at 32 sites in 7 countries. Adult patients with advanced solid tumors were enrolled and received intravenous nemvaleukin once daily on days 1–5 (21-day cycle) at 0.1–10 µg/kg/day (part A), or at the RP2D (part B), or with pembrolizumab (part C). Primary endpoints were RP2D selection and dose-limiting toxicities (part A), and overall response rate (ORR) and safety (parts B and C).

Results

From July 2016 to March 2023, 243 patients were enrolled and treated (46, 74, and 166 in parts A, B, and C, respectively). The maximum tolerated dose was not reached. RP2D was determined as 6 µg/kg/day. ORR with nemvaleukin monotherapy was 10% (7/68; 95% CI 4 to 20), with seven partial responses (melanoma, n=4; renal cell carcinoma, n=3). Robust CD8+ T and natural killer cell expansion, and minimal regulatory T cell expansion were observed following nemvaleukin treatment. ORR with nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab was 13% (19/144; 95% CI 8 to 20), with 5 complete and 14 partial responses; 6 responses were in PD-(L)1 inhibitor-approved and five in PD-(L)1 inhibitor-unapproved tumor types. Three responses were in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. The most common grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in parts B and C, respectively, were neutropenia (49%, 21%) and anemia (10%, 11%); 4% of patients in each part discontinued due to TRAEs.

Conclusions

Nemvaleukin was well tolerated and demonstrated promising antitumor activity across heavily pretreated advanced solid tumors. Phase 2/3 studies of nemvaleukin are ongoing.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Cytokine, Immunotherapy, Solid tumor, Skin Cancer, Ovarian Cancer

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The interleukin 2 (IL-2) pathway is a validated immuno-oncology treatment target. High-dose recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2) is approved for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and metastatic melanoma; however, it is associated with acute toxicities such as capillary leak syndrome that severely limit its clinical application to intensive care settings.

Nemvaleukin alfa (nemvaleukin, ALKS 4230) is a novel, engineered IL-2 cytokine designed to mitigate the risk of toxicities and immunosuppression associated with rhIL-2.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In the phase 1/2, non-randomized, first-in-human ARTISTRY-1 study of 243 patients, antitumor activity of nemvaleukin was observed when it was given as monotherapy and in combination with the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab across advanced solid tumors, including melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and, most notably, in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, which does not usually respond to immunotherapy.

Nemvaleukin was administered in an outpatient setting throughout treatment and had a manageable safety profile, with a low rate of discontinuation due to adverse events.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The manageable safety profile and antitumor activity of nemvaleukin in a broad range of solid tumors support its investigation in large phase 2/3 studies.

Introduction

Immunotherapies, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), have marked a paradigm shift in the treatment of some malignancies.1 Yet, a notable subset of patients does not benefit clinically, encounter tolerability challenges, or develop resistance to these treatments.1 2 These patients have few therapeutic options after treatment failure, representing a significant unmet clinical need.

The interleukin 2 (IL-2) pathway is a validated immuno-oncology treatment target.3 4 High-dose recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2, aldesleukin) was one of the first immunotherapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for advanced renal-cell carcinoma (RCC) in 1992, followed by metastatic melanoma, with durable efficacy in patients who had progressed on ICIs including antiprogrammed cell death protein-(ligand) 1 (PD-(L)1) inhibitors.4 5 However, high doses of IL-2 needed to achieve antitumor effects via activation of the intermediate-affinity IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) also result in a potent interaction with the high-affinity IL-2R leading to regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion-mediated immunosuppression and reduced antitumor activity.3 4 6 Furthermore, high-dose IL-2 is associated with potentially life-threatening acute toxicities such as capillary leak syndrome, thereby severely limiting its clinical application.4 7 8

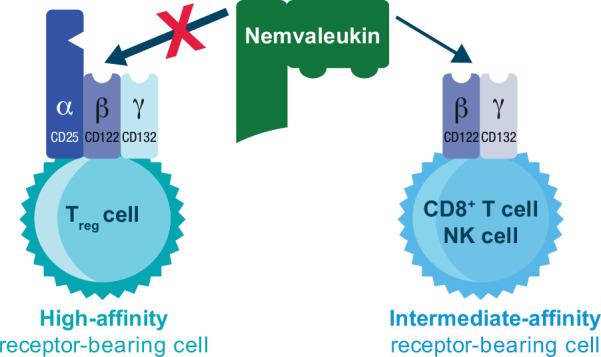

Nemvaleukin alfa (nemvaleukin, ALKS 4230) is a novel, engineered IL-2 cytokine that is a stable fusion of circularly permuted IL-2 to the extracellular portion of the IL-2Rα chain and is sterically occluded from binding to the high-affinity trimeric IL-2R.9 Nemvaleukin selectively binds to the intermediate-affinity IL-2R complex, preferentially activating and expanding tumor-killing CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, with minimal expansion of Tregs, thereby mitigating the risk of toxicities and immunosuppression associated with binding of IL-2 to the high-affinity IL-2R (figure 1).9 10 Furthermore, nemvaleukin is inherently active, does not require metabolic or proteolytic conversion and does not degrade into native IL-2.9 10 In preclinical studies, nemvaleukin showed enhanced pharmacokinetic and preferential pharmacodynamic properties, with improved antitumor efficacy and reduced toxicity relative to rhIL-2.9,11

Figure 1. Mechanism of action of nemvaleukin. Nemvaleukin is designed to selectively bind to the intermediate-affinity dimeric interleukin-2 receptor and is sterically occluded from binding to the high-affinity trimeric interleukin-2 receptor. Adapted from Lopes et al.9 10 under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. NK, natural killer; Treg, regulatory T cell.

ARTISTRY-1 (NCT02799095) is a first-in-human study investigating the safety, recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D), and antitumor activity of intravenous nemvaleukin in heavily pretreated patients with advanced solid tumors, alone and in combination with the PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab. We present results from the primary analysis of ARTISTRY-1.

Methods

Study design and participants

ARTISTRY-1 is a global, multicenter, open-label, phase 1/2 study that enrolled patients at 32 sites in 7 countries: the USA, Australia, Canada, Belgium, Poland, Spain, and the Republic of Korea (see the online supplement). This was a three-part study comprising part A (dose-escalation monotherapy), part B (dose-expansion monotherapy), and part C (combination therapy with pembrolizumab).

In part C, patients were allocated to one of seven different predefined cohorts according to their tumor type (described in online supplemental methods). A safety run-in phase determined the safety of combination therapy with pembrolizumab. Patients in part A or part B who experienced progressive disease after two or more cycles or stable disease (SD) after at least four cycles of nemvaleukin monotherapy could also be enrolled in part C as a predefined monotherapy rollover cohort. An extension phase was planned for participants who were receiving clinical benefit and were completing or had completed 1 year of treatment in parts B or C to assess long-term safety and effectiveness of nemvaleukin monotherapy or combination with pembrolizumab.

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1. Patients were enrolled as follows: part A: advanced solid tumors including lymphomas, part B: advanced melanoma or RCC, and part C: any advanced solid tumor. Detailed eligibility criteria are provided in online supplemental methods.

Study treatment

Procedures in part A for determining dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) and maximum tolerated doses (MTDs) are described in online supplemental methods, as are dosing details for parts B and C. Briefly, patients in part B received nemvaleukin as a 30 min intravenous infusion at the RP2D once daily for five consecutive days; cycle 1 was 14 days (9 days off treatment), cycles 2+ were 21 days (16 days off treatment). In part C, a safety run-in cohort was implemented for the first three patients who received intravenous nemvaleukin 1 µg/kg/day plus pembrolizumab. Subsequently, patients were enrolled into cohorts 1–4 to receive intravenous nemvaleukin 3 µg/kg/day or at RP2D once daily for five consecutive days plus intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg on day 1 of a 21-day cycle. After RP2D determination, patients were enrolled into tumor-specific cohorts 5–7 to receive nemvaleukin at the RP2D plus intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg on day 1 of each cycle (pembrolizumab infusion administered before nemvaleukin).

Patients received combination treatment for a maximum of 2 years (initial plus extension phase). Beyond 2 years, patients could continue nemvaleukin as monotherapy if they did not meet any discontinuation criteria. Protocol-defined cycle delays and treatment discontinuations are described in online supplemental methods.

Safety was assessed throughout the treatment period and up to 30 days after last dose (up to 90 days for serious adverse events (AEs)). DLTs were nemvaleukin-related AEs that were observed during the interval from cycle 1 day 1 to cycle 2 day 15 (online supplemental methods). AEs were graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, versions 4.03 and 5.0.

Tumor assessments were conducted at baseline and at the end of even-numbered cycles (eg, cycles 2, 4, 6). Detailed pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessments are described in online supplemental methods.

Outcomes

The primary objectives of part A were to evaluate the safety and tolerability and determine the MTD and RP2D of nemvaleukin, and for part B to assess safety and antitumor activity of nemvaleukin monotherapy at the RP2D. For part C, the primary objective was to characterize the safety and antitumor activity of nemvaleukin in combination with pembrolizumab. The primary end point for part A was the incidence of DLTs and for parts B and C was overall response rate (ORR), defined as the proportion of patients with a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR). ORR was based on investigator review of the radiographic or photographic images, per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1. Secondary objectives and end points are described in online supplemental methods.

Statistical analysis

A 3+3 design was used to determine the MTD and RP2D dose in part A. A sample size of approximately 3–6 patients per cohort (36–54 in all) was planned assuming six or seven dose-escalation levels. In part B, the planned sample size was a maximum of 41 evaluable patients in each cohort, based on Simon’s two-stage design for phase 2 studies.12 The assumed alpha was 0.05 and power was 90%. In part C, a sample size of up to 20 per cohort was planned for cohorts 1, 2, and 3 based on clinical considerations; sample size for monotherapy rollover cohort 4 was not applicable. Sample sizes for cohorts 5, 6, and 7 were planned for up to 53, 42, and 36 patients, respectively, based on Simon’s two-stage design with an assumed alpha of 0.15 and power of 85%.

Safety, antitumor activity, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic data were summarized descriptively. The safety population included patients who received at least one dose of study treatment. The efficacy-evaluable population comprised patients who completed two treatment cycles and had at least one follow-up scan. Disease control rate (see online supplemental methods for definition) and ORR data were summarized by number, percentage, and 95% CI. CIs were obtained using an exact approach given the small sample size. Additional statistical methods are provided in online supplemental methods.

Results

Patients

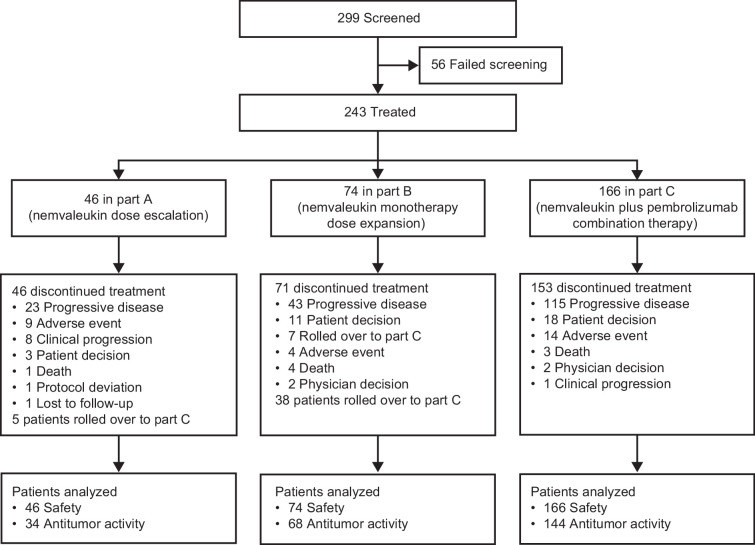

From July 2016 to March 2023, 299 patients were screened; 56 (19%) did not meet eligibility criteria. Of 243 patients, 46 were treated in part A, 74 in part B, and 166 in part C (figure 2). Five patients in part A and 38 in part B rolled over to part C. At data cut-off (March 27, 2023) for primary analysis, 100% of patients in part A, 96% in part B, and 92% in part C had discontinued treatment, the most common reason being progressive disease. 20 patients remained in study: 4 in part B, 16 in part C. Three patients continued on nemvaleukin monotherapy beyond 2 years of treatment.

Figure 2. ARTISTRY-1 study profile.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in table 1. The median age was 60 years (range 35–82) in part A, 67 years (37–82) in part B, and 62 years (24–85) in part C. The most common tumor types were melanoma in parts A and B, and melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer in part C. Most patients were heavily pretreated, with a median of two to three previous lines of therapy (range 1–9).

Table 1. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Characteristic | Part An=46 | Part Bn=74 | Part Cn=166 |

| Age, years, median (range) | 60 (35–82) | 67 (37–82) | 62 (24–85) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 27 (59) | 49 (66) | 85 (51) |

| Female | 19 (41) | 25 (34) | 81 (49) |

| Race | |||

| White | 41 (89) | 67 (91) | 142 (86) |

| Black or African American | 4 (9) | 1 (1) | 15 (9) |

| Asian | 0 | 6 (8) | 3 (2) |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 | 5 (3) |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0 | 18 (39) | 30 (40) | 53 (32) |

| 1 | 28 (61) | 44 (60) | 113 (68) |

| Previous lines of therapy, median (range) | 3 (1–8) | 2 (1–8) | 3 (1–9) |

| Primary tumor type | |||

| Melanoma | 10 (22) | 47 (64) | 30 (18) |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | 0 | 0 | 29 (18) |

| Ovarian | 2 (4) | 0 | 17 (10) |

| Colorectal cancer | 0 | 0 | 13 (8) |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 6 (13) | 27 (36) | 12 (7) |

| Small-cell lung cancer | 0 | 0 | 8 (5) |

| Bladder cancer | 0 | 0 | 7 (4) |

| Head and neck cancer | 0 | 0 | 7 (4) |

| Cervical cancer | 0 | 0 | 6 (4) |

| Breast cancer | 1 (2) | 0 | 6 (4) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (4) | 0 | 6 (4) |

| Esophageal cancer | 2 (4) | 0 | 4 (2) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 4 (9) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Uterine | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Gastric | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Other | 17 (37) | 0 | 17 (10) |

Data are presented as number of patients (%) unless otherwise noted. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor;ECOG, .

ECOGEastern Cooperative Oncology GroupICIimmune checkpoint inhibitor

Part A: determination of nemvaleukin RP2D

In part A, median duration of nemvaleukin monotherapy was 7.6 weeks and patients received a median of two treatment cycles (online supplemental table 1). The maximum dose tested was 10 µg/kg and the MTD was not reached. One DLT of grade 4 acute kidney injury was observed in the 10 µg/kg cohort. Treatment-emergent AEs at different escalating doses are shown in online supplemental table 2. Pharmacokinetic analyses showed that nemvaleukin exposure increased proportionally with increasing dose (online supplemental table 3). Based on the safety and pharmacokinetic data, the nemvaleukin RP2D was established as 6 µg/kg/day intravenously on days 1–5 of a 21-day cycle. Pharmacodynamic analysis during the first two cycles showed that nemvaleukin induced consistent and dose-dependent expansion of NK and CD8+ T cells over baseline, while the expansion of Tregs was minimal. Peak expansion was seen on day 8 of each cycle (online supplemental figure S1).

Part B: efficacy, safety and pharmacodynamic outcomes with nemvaleukin monotherapy

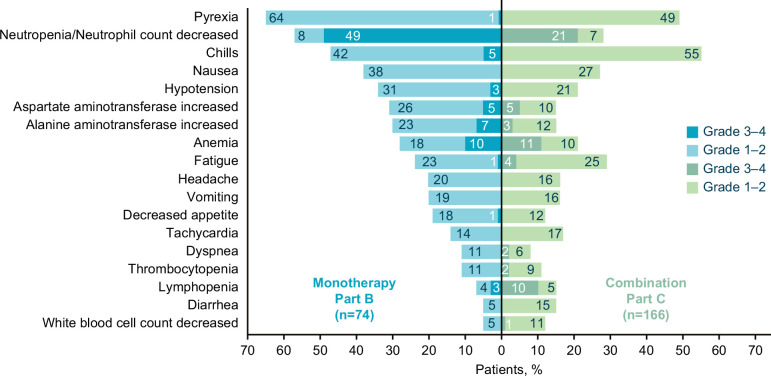

In part B, patients received a median of six treatment cycles over 18.1 weeks (online supplemental table 1). Dose interruptions and dose reductions due to AEs were reported in 37 (50%) and 6 (8%) patients, respectively. A total of 72 patients (97%) experienced at least one nemvaleukin-related treatment-emergent AE (TRAE) (table 2 and figure 3). Most TRAEs were grades 1–2 in severity. The most common TRAEs (≥20%) of any grade included fever (n=48 (65%)), neutropenia (42 (57%)), and chills (35 (47%)). Grade 3–4 TRAEs were reported in 56 (76%) patients, the most frequent being uncomplicated neutropenia (n=36 (49%)) and anemia (n=7 (10%)) (table 2). There were no grade 5 TRAEs. Serious TRAEs of grades 3 and 4 were reported in 10 (14%) and 3 (4%) patients, respectively. TRAEs leading to treatment discontinuation were reported in 3 (4%) patients. One death due to COVID-19 was reported in part B and was considered unrelated to study drug treatment.

Table 2. Summary of nemvaleukin-related treatment-emergent adverse events in parts B and C (safety populations).

| Event | Part Bn=74 | Part Cn=166 | ||||

| Grades 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grades 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| All events | 16 (22) | 41 (55) | 15 (20) | 66 (40) | 74 (45) | 11 (7) |

| Serious events | 2 (3) | 10 (14) | 3 (4) | 10 (6) | 16 (10) | 1 (1) |

| Led to discontinuation* | 3 (4) | 6 (4) | ||||

| Led to death | 0 | 1 (<1) | ||||

| Grade 1 or 2 events in ≥10% of patients in either group and corresponding grade 3–4 events | ||||||

| Pyrexia | 47 (64) | 1 (1) | 0 | 82 (49) | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 6 (8) | 22 (30) | 14 (19) | 12 (7) | 27 (16) | 8 (5) |

| Chills | 31 (42) | 4 (5) | 0 | 92 (55) | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 28 (38) | 0 | 0 | 44 (27) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 23 (31) | 2 (3) | 0 | 35 (21) | 0 | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 19 (26) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 16 (10) | 8 (5) | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 17 (23) | 5 (7) | 0 | 20 (12) | 5 (3) | 0 |

| Anemia | 13 (18) | 7 (10) | 0 | 16 (10) | 19 (11) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 17 (23) | 1 (1) | 0 | 42 (25) | 6 (4) | 0 |

| Headache | 15 (20) | 0 | 0 | 26 (16) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (5) | 0 | 0 | 24 (15) | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 13 (18) | 1 (1) | 0 | 20 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 14 (19) | 0 | 0 | 27 (16) | 0 | 0 |

| Tachycardia | 10 (14) | 0 | 0 | 28 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 8 (11) | 0 | 0 | 10 (6) | 4 (2) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 8 (11) | 0 | 0 | 15 (9) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Blood pressure increased | 4 (5) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 5 (7) | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Infusion-related reaction | 5 (7) | 0 | 0 | 12 (7) | 4 (2) | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 8 (5) | 13 (8) | 3 (2) |

| White blood cell count decreased | 4 (5) | 0 | 0 | 18 (11) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Blood creatinine increased | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 13 (8) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 4 (5) | 0 | 0 | 14 (8) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 5 (7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

Data as of March 27, 2023. Data are presented as number of patients (%).

Adverse events coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, V.25.0. The toxicity severity of adverse events was graded using National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, V.4.03 and V.5.0.

Events leading to treatment discontinuation in Part B included one event each of electrocardiogram T wave abnormal and troponin I increased in one , and bronchospasm and failure to thrive, each in one . Events leading to discontinuation in Part C included one event each of fatigue, cytokine release syndrome, infusion-related reaction, starvation, arthralgia, and pneumonitisIn part B, treatment discontinuation was prompted by individual events, including abnormal ECG T waves and elevated troponin I levels in one patient, as well as bronchospasm and failure to thrive, each in one patient. In part C, events leading to discontinuation included one instance each of fatigue, cytokine release syndrome, infusion-related reaction, starvation, arthralgia, and pneumonitis. Adverse events of grades 1–2 occurring in ≥10% of patients in any group and all grade 3 and 4 events are shown. In part B, other grade 3 events were as follows: hypophosphatemia, blood bilirubin increased, and hyperbilirubinemia in 2 (3%) patients each; hypokalemia, asthenia, hypertransaminasemia, presyncope, gamma-glutamyltransferase increased, transaminases increased, autoimmune anemia, bacteremia, bronchospasm, cellulitis, chest pain, failure to thrive, and hypoxia in 1 (1%) patient each; there was one grade 4 event of immune thrombocytopenia and no grade 5 events occurred. In part C, other grade 3 events were as follows: hypertension in 8 (5%) patients; hypophosphatemia, blood phosphorous decreased, hypokalemia, hypertransaminasemia, muscular weakness, supraventricular extrasystoles, and syncope in 2 (3%) patients each; asthenia, gamma-glutamyltransferase increased, musculoskeletal chest pain, cytokine release syndrome, abdominal pain, pain, rash maculopapular, dehydration, blood creatine phosphokinase increased, hyperhidrosis, hyponatremia, pleural effusion, confusional state, leukopenia, liver function test increased/abnormal, asthma, cholecystitis acute, hypovolemia, myelopathy, and pneumonitis in 1 (1%) patient each; there was one grade 5 event of starvation.

Figure 3. Summary of most frequent nemvaleukin-related treatment-emergent adverse events. Nemvaleukin-related treatment-emergent adverse events (≥10% in either cohort) in patients with advanced treatment-refractory solid tumors receiving nemvaleukin as monotherapy (part B; n=74) or in combination with pembrolizumab (part C; n=166). Part B includes patients who received nemvaleukin 6 µg/kg intravenous. Part C includes patients who received nemvaleukin at 1, 3, or 6 µg/kg intravenous in combination with pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenous.

At primary analysis, confirmed overall responses were observed in seven (10% (95% CI 4 to 20)) of 68 patients treated with nemvaleukin monotherapy; all were PRs (table 3). Of observed responses, four were in patients with melanoma, including cutaneous and mucosal subtypes (ORR 9% (95% CI 2% to 21%)) and three in patients with RCC (ORR 14% (95% CI 3% to 35%)). All responders had been treated previously with a PD-(L)1 inhibitor. The median duration of response was 18.4 weeks (95% CI 6.1 to not estimable). A total of 44 (65%) of 68 patients experienced SD, five of whom had SD for >6 months. Among patients with SD, two with melanoma and one with RCC had unconfirmed PR. Further, two of six responses (confirmed and unconfirmed) in melanoma were in mucosal melanoma.

Table 3. Summary of confirmed responses* and duration of response.

| Part C, PD-(L)1 cohorts | |||||

| Part Bn=68 | Part C, overalln=144 | PD-(L)1 inhibitor-unapproved† cohort 1n=36 | PD-(L)1 inhibitor-approved†, pretreated cohort 2n=22 | PD-(L)1 inhibitor-approved†, naive cohort 3n=21 | |

| Overall response rate, no. (%) (95% CI) | 7 (10) (4 to 20) | 19 (13) (8 to 20) | 5 (14) (5 to 30) | 0 (0 to 15) | 6 (29) (11 to 52) |

| Confirmed best overall response | |||||

| Complete response (CR) | 0 | 5 (4) | 2 (6) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Partial response (PR) | 7 (10) | 14 (10) | 3 (8) | 0 | 5 (24) |

| Stable disease (SD) | 44 (65) | 70 (49) | 15 (42) | 11 (50) | 8 (38) |

| Progressive disease | 17 (25) | 55 (38) | 16 (44) | 11 (50) | 7 (33) |

| Disease control, no. (%) (95% CI) | 33 (49) (36 to 61) | 57 (40) (32 to 48) | 11 (31) (16 to 48) | 5 (22) (8 to 45) | 10 (48) (26 to 70) |

| Median duration of response, weeks (range) | 18 (6 to NE) | 65.0 (21 to 160) | NA | NA | NA |

Investigator-assessed responses (RECIST vV.1.1) are shown with nemvaleukin monotherapy in Ppart B and nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab combination therapy in Ppart C. Data as of 27 March 2023. Except where noted, data are no. (%). Overall response rate is defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a CR or PR (where confirmation of CR/PR is required) using RECIST V.1.1 guidelines. Disease control rate is defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a CR, PR, or SD (occurred at cycle 4four or later) using RECIST V.1.1 guidelines.

PD-(L)1 inhibitor–approved/unapproved indication based on US FDA prescribing information at the time of the study design and could have changed over time Only confirmed responses are shown: among patients with SD, unconfirmed responses were reported in two with melanoma and in one with renal-cell carcinoma in part B, and in two patients with melanoma and one each with ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and cervical cancer in part C.

Only confirmed responses are shown: among with , unconfirmed responses were reported in two with melanoma and in one with renal-cell carcinoma in Part B, and in two with melanoma and one each with ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and cervical cancer in Part C.PD-(L)1 inhibitor-approved/unapproved indication based on US FDA prescribing information at the time of the study design and could have changed over time.

FDAUS Food and Drug AdministrationNA, not applicable; NE, not estimable; PD-(L)1, programmed cell death protein-(ligand) 1RECISTResponse Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

Pharmacodynamic analysis showed that nemvaleukin monotherapy induced the expansion of CD8+ T cells and NK cells with a maximum fold change of 6.52 for NK cells and 2.53 for CD8+ T cells during the first two cycles of treatment (online supplemental table 4). Peak expansion of CD8+ T cells and NK cells was noted on day 8 of the treatment cycle with minimal expansion of Tregs (online supplemental figure S2).

Part C: outcomes with nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab

Of 166 patients in part C, three received nemvaleukin at 1 µg/kg/day during the safety run-in, 137 received nemvaleukin at 3 µg/kg/day, and 26 received nemvaleukin at 6 µg/kg/day daily for 5 days in addition to pembrolizumab. Patients received a median of four treatment cycles over 12.4 weeks (online supplemental table 1). Dose interruptions and dose reductions due to AEs were reported in 81 (49%) and 3 (2%) patients, respectively. A total of 162 patients (98%) had at least one TRAE (table 2). The most common (≥20%) TRAEs of any grade included chills (n=92 (55%)), fever (82 (49%)), and fatigue (48 (29%)). Grade 3–4 TRAEs were reported in 85 (52%) patients; the most frequent were neutropenia (n=35 (21%)) and anemia (19 (11%)) (table 2). Grade 3 serious TRAEs were reported in 16 (10%) patients and grade 4 in 1 (1%). TRAEs leading to discontinuation were reported in six patients (4%). Four deaths were reported of which three (one each due to cardiac arrest, pancreatic carcinoma, and large intestine perforation) were considered unrelated to nemvaleukin by the investigator. One death from inanition and progression of disease in a patient with pancreatic cancer was assessed by the investigator as related to nemvaleukin.

Comprehensive evaluation of the onset and duration of neutropenia was limited by the low frequency of planned laboratory sampling in the later cycles of nemvaleukin treatment. A subset analysis of neutropenia events during cycle 1 (n=27), when increased monitoring was required (days 1, 3, 5, 8, and 15), showed that the median time to onset of neutropenia was 4 days, with 74% of the events resolving by day 8 of the cycle (3 days after the last planned dose for the cycle) and an additional 15% of events were reported as resolved on days 9/10 (5 days after the last planned dose for the cycle). There was one case of febrile neutropenia in part A. Growth factors were administered in some cases for the management of neutropenia. In part B, 4 (5%) patients received filgrastim, and in part C, 4 (2%) patients received filgrastim, 3 (2%) patients received filgrastim-sndz, and 1 (1%) patient received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

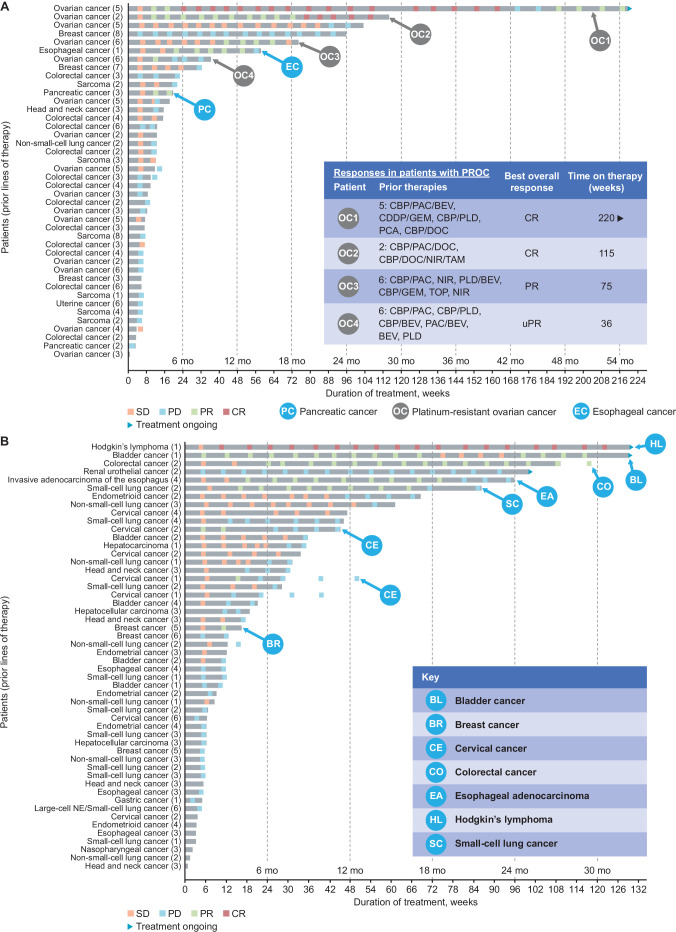

Antitumor activity of nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab was observed across various tumor types, including both PD-(L)1 inhibitor approved and unapproved (figure 4, table 3), with confirmed overall responses in 19 (13% (95% CI 8% to 20%)) of 144 patients (table 3). Overall, 5 (4%) patients had a CR and 14 (10%) had PRs. The median duration of response was 65.0 weeks (95% CI 21 to 160). Seventy (49%) patients had SD, 15 (10%) for >6 months. Confirmed CRs were observed in two patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROC), two with melanoma, and one with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Confirmed PRs were observed in two patients each with RCC, non-small-cell lung cancer, and esophageal cancer, and in one patient each with bladder cancer, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, small-cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, melanoma, and PROC (figure 4). Durable SD for >6 months was observed in cervical cancer, bladder cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, PROC, and endometrioid cancer (figure 4). Among patients with SD, two with melanoma and one each with ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and cervical cancer had unconfirmed PR.

Figure 4. Summary of responses. (A) Duration of nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab therapy (part C) for patients in PD-(L)1 inhibitor-unapproved cohort.* (B) Duration of nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab therapy (part C) for patients in PD-(L)1 inhibitor-approved cohort.* *PD-(L)1 inhibitor-approved/unapproved indication based on US FDA prescribing information at the time of the study design and could have changed over time. Responses per investigator-assessed Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1. Swimmer plots show both confirmed and unconfirmed responses. BEV, bevacizumab; BL, bladder cancer; BR, breast cancer; CBP, carboplatin; CDDP, cisplatin; CE, cervical cancer; CO, colorectal cancer; CR, complete response; DOC, docetaxel; EA, esophageal adenocarcinoma; ER, estrogen receptor; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GEM, gemcitabine; HER, human epidermal growth factor; Mo, month; NIR, niraparib; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; PAC, paclitaxel; PCA, paclitaxel albumin; PD, progressive disease; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride; PR, partial response; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; SD, stable disease; TAM, tamoxifen; TOP, topotecan; uPR, unconfirmed partial response.

Subgroup analysis of part C by cohort and tumor type was conducted. The median number of prior lines of therapies was three in the PD-(L)1 inhibitor-unapproved cohort 1 and PD-(L)1 inhibitor-pretreated cohort 2, and two in the PD-(L)1 inhibitor-naive cohort 3. ORR among 36 patients in cohort 1 was 14%, with two CRs and three PRs (figure 4). No responses were reported in the 22 patients in cohort 2; 11 had SD, 3 of whom had SD for >6 months. ORR among 21 patients in cohort 3 was 29%, with 1 CR and 5 PRs; 8 patients had SD, 2 for >6 months. Of the 14 evaluable patients with PROC in cohort 1, two achieved a CR and one achieved a PR (ORR 21% for patients with PROC). One patient each with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, bladder cancer, and renal urothelial cancer in the PD-(L)1 inhibitor-approved cohort had ongoing treatment and clinical benefit for >2 years (figure 4). Of the 39 evaluable patients who rolled over to combination therapy in cohort 4, 3 achieved PR, and 23 had SD, 6 of whom had SD for >6 months.

Discussion

Interleukin-2 cytokine therapy has led to long-term remissions in patients with RCC and melanoma.5 However, the therapy is only suitable for a small proportion of patients owing to the increased risk of capillary leak syndrome.4 The current primary analysis of ARTISTRY-1 demonstrated a manageable safety and tolerability profile and promising antitumor activity of nemvaleukin alone and in combination with pembrolizumab in heavily pretreated patients with advanced solid tumors. Durable responses were observed with nemvaleukin and nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab across a wide range of tumors, including those that had not responded to or progressed with anti-PD-(L)1 treatment or that were anti-PD-(L)1 unapproved. The study also provided proof of the principle for preferential expansion of immunostimulatory effector cells with minimal expansion of immunosuppressive Tregs, thus confirming the design hypothesis of nemvaleukin.

In this study, nemvaleukin was administered in an outpatient setting in parts B and C and demonstrated an acceptable safety profile. Across escalating doses, only one DLT of acute kidney injury was observed at the 10 µg/kg dose. The MTD was not reached. The safety profile of nemvaleukin monotherapy at the RP2D of 6 µg/kg/d was consistent with that reported during dose escalation. TRAEs reported in all three parts were manageable with or without nemvaleukin dose modifications and supportive treatment. Neutropenia events were transient and only one case of febrile neutropenia was reported. Nemvaleukin at all doses administered in combination with pembrolizumab did not demonstrate any additive toxicity to the established safety profile of pembrolizumab alone.13 14 This tolerability profile of nemvaleukin allows for outpatient administration unlike high-dose rhIL-2, which requires hospitalization.8 Further, pharmacodynamic analyses demonstrated that selective binding of nemvaleukin to the intermediate-affinity IL-2R appeared to have a positive impact on tolerability and is also likely to mitigate the risk of toxicities associated with binding to the high-affinity IL2-R such as capillary leak syndrome,7 9 thereby enhancing the efficacy of nemvaleukin and expanding the potential therapeutic window of IL-2.

Nemvaleukin exhibited encouraging antitumor activity alone and in combination with pembrolizumab, especially in heavily pretreated patients with solid tumors. Nemvaleukin monotherapy demonstrated antitumor activity in advanced cutaneous or mucosal melanoma and RCC, tumor types in which high-dose rhIL-2 has proven activity; notably, all responders were ICI pretreated. Antitumor activity was also observed with nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab across diverse tumor types that do not typically respond well to ICI therapy (including ICI-unapproved and post-ICI failure).2 15 Responses were observed across different tumor types, including RCC, esophageal cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, bladder cancer, and, most notably, PROC, which does not typically respond to immunotherapy.15 16

This study had a few limitations. There were multiple amendments to the study resulting in changes to the definition of DLTs and efficacy parameters, including updates in timing of samples/data collection. Limited tissue samples were collected for pharmacodynamic assessment. Additionally, the execution of the study and some aspects of continuum of patient care were impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, owing to the phase 1/2 study design, the sample sizes for each tumor type were small and there was no comparator arm. Patients receiving combination therapy were enrolled in cohorts based on pembrolizumab-approved or pembrolizumab-unapproved indications at the time of the study design; however, these indications have since changed. Lastly, immune cell expansion for pharmacodynamic analyses was only measured in periphery due to the limited availability of tumor tissue.

ARTISTRY-1 demonstrated proof of the principle of nemvaleukin antitumor activity alone and in combination with pembrolizumab in a broad range of refractory, pretreated malignancies. The manageable safety profile enables nemvaleukin application in the majority of patients with cancer regardless of their cardiovascular fitness. Further clinical investigation of nemvaleukin monotherapy in mucosal and cutaneous melanoma (ARTISTRY-6; NCT04830124) and nemvaleukin plus pembrolizumab in PROC (ARTISTRY-7; NCT05092360) is ongoing.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families who made this study possible, and the investigators and the clinical study teams for study support. Professional medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Madeeha Aqil, PhD, MWC, CMPP, of Parexel International and funded by Mural Oncology. Results reported in this manuscript were previously presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) congress (June 3, 2022–June 7, 2022) as an oral presentation (abstract # 2500).

Footnotes

Funding: The study was sponsored by Mural Oncology (part of Alkermes, Inc. at the time of study design and conduct).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: The study protocol and all amendments were approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each site. A safety review committee monitored safety in part A and supported dose-escalation decisions and RP2D selection, and an independent data-monitoring committee monitored safety and efficacy data and overall study conduct in parts B and C. All participants provided written informed consent according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability free text: The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study will be available after review of the request and approval from sponsor and coauthors.

Contributor Information

Ulka N Vaishampayan, Email: vaishamu@med.umich.edu.

Jameel Muzaffar, Email: jameel.muzaffar@duke.edu.

Ira Winer, Email: iwiner@med.wayne.edu.

Seth D Rosen, Email: srosen@hemoncfl.com.

Christoper J Hoimes, Email: christopher.hoimes@duke.edu.

Aman Chauhan, Email: axc3268@med.miami.edu.

Anna Spreafico, Email: Anna.Spreafico@uhn.ca.

Karl D Lewis, Email: lewiskarld@gmail.com.

Debora S Bruno, Email: Debora.bruno@UHhospitals.org.

Olivier Dumas, Email: Olivier.dumas.med@ssss.gouv.qc.ca.

David F McDermott, Email: dmcdermo@bidmc.harvard.edu.

James F Strauss, Email: jstrauss@marycrowley.org.

Quincy S Chu, Email: quincy.chu@albertahealthservices.ca.

Lucy Gilbert, Email: lucy.gilbert@mcgill.ca.

Arvind Chaudhry, Email: arvind.chaudhry@aoncology.com.

Emiliano Calvo, Email: emiliano.calvo@startmadrid.com.

Rita Dalal, Email: Dalal.rita@gmail.com.

Valentina Boni, Email: vboni@nextoncology.eu.

Marc S Ernstoff, Email: marc.ernstoff@nih.gov.

Vamsidhar Velcheti, Email: vamsidhar.velcheti@nyulangone.org.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Johnson DB, Nebhan CA, Moslehi JJ, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:254–67. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00600-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Miguel M, Calvo E. Clinical challenges of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sim GC, Radvanyi L. The IL-2 cytokine family in cancer immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25:377–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald A, Wu T-C, Hung C-F. Interleukin 2-based fusion proteins for the treatment of cancer. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:1-11. doi: 10.1155/2021/7855808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchbinder EI, Dutcher JP, Daniels GA, et al. Therapy with high-dose interleukin-2 (HD IL-2) in metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma following PD1 or PDL1 inhibition. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:49. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sim GC, Martin-Orozco N, Jin L, et al. IL-2 therapy promotes suppressive ICOS+ Treg expansion in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:99–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI46266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amaria RN, Reuben A, Cooper ZA, et al. Update on use of aldesleukin for treatment of high-risk metastatic melanoma. Immunotargets Ther. 2015;4:79–89. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S61590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dutcher JP, Schwartzentruber DJ, Kaufman HL, et al. High dose interleukin-2 (aldesleukin) - expert consensus on best management practices-2014. J Immunother Cancer. 2014;2:26. doi: 10.1186/s40425-014-0026-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes JE, Fisher JL, Flick HL, et al. ALKS 4230: a novel engineered IL-2 fusion protein with an improved cellular selectivity profile for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000673. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes JE, Sun L, Flick HL, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects of nemvaleukin alfa, a selective agonist of the intermediate-affinity IL-2 receptor, in cynomolgus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2021;379:203–10. doi: 10.1124/jpet.121.000612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Losey HC, Lopes JE, Dean RL, et al. Abstract 591: Efficacy of ALKS 4230, a novel immunotherapeutic agent, in murine syngeneic tumor models alone and in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:591. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M, Ma X, Guo L, et al. Safety and efficacy profile of pembrolizumab in solid cancer: pooled reanalysis based on randomized controlled trials. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:2851–60. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S146286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahmer JR, Long GV, Hamid O, et al. Safety profile of pembrolizumab monotherapy based on an aggregate safety evaluation of 8937 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2024;199:113530. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2024.113530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore KN, Bookman M, Sehouli J, et al. Atezolizumab, bevacizumab, and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed stage III or IV ovarian cancer: placebo-controlled randomized phase III trial (IMagyn050/GOG 3015/ENGOT-OV39) J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1842–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morand S, Devanaboyina M, Staats H, et al. Ovarian cancer immunotherapy and personalized medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6532. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.