Abstract

Explorations of barriers and enablers (or barriers and facilitators) to a desired health practice, implementation process, or intervention outcome have become so prevalent that they seem to be a default in much health services and public health research. In this article, we argue that decisions to frame research questions or analyses using barriers and enablers (B&Es) should not be default. Contrary to the strengths of qualitative research, the B&Es approach often bypasses critical reflexivity and can lead to shallow research findings with poor understanding of the phenomena of interest. The B&Es approach is untheorised, relying on assumptions of linear, unidirectional processes, universally desirable outcomes, and binary thinking which are at odds with the rich understanding of context and complexity needed to respond to the challenges faced by health services and public health. We encourage researchers to develop research questions using informed deliberation that considers a range of approaches and their implications for producing meaningful knowledge. Alternatives and enhancements to the B&Es approach are explored, including using ‘whole package’ methodologies; theories, conceptual frameworks, and sensitising ideas; and participatory methods. We also consider ways of advancing existing research on B&Es rather than doing ‘more of the same’: researchers can usefully investigate how a barrier or enabler works in depth; develop and test implementation strategies for addressing B&Es; or synthesise the B&Es literature to develop a new model or theory. Illustrative examples from the literature are provided. We invite further discussion on this topic.

Keywords: facilitators, research questions, complexity, theory, context

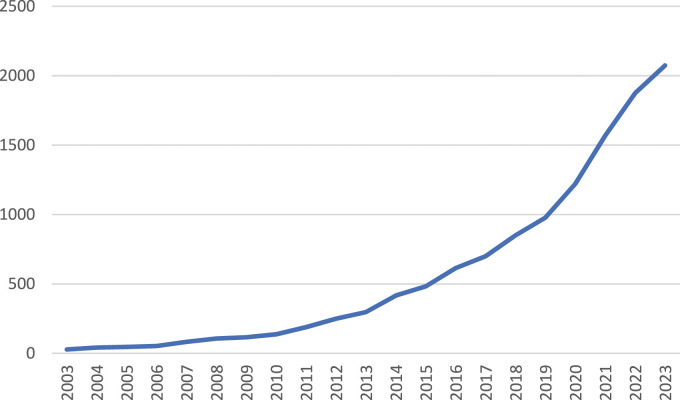

Research questions are pivotal in sound qualitative research design. They help to focus on a study’s goals and conceptual framework. They guide many facets of the research approach, shaping how we think about, collect, and analyse data, as well as how we present findings and recommendations. Research questions framed as an exploration of barriers and enablers (or barriers and facilitators) to a desired health practice, implementation process, or intervention outcome are increasingly prevalent. Explorations of barriers and enablers (B&Es) can be found in research relating to prevention and health promotion through to health services and clinical research, and studies conducted for different purposes including problem description, co-design, intervention studies, and evaluation. This increasing trend – illustrated in Figure 1 – has reached the point where a B&Es approach seems to be the default in much health services and public health research. In this article, we suggest that the decision to frame research questions using B&Es should not be a default. Rather, it should be the result of a process of informed deliberation that considers a range of approaches and their implications for producing findings.

Figure 1.

Scopus search (article title, abstract, keywords) for (‘barriers and enablers’ OR ‘barriers and facilitators’) health 2003–2023.

The Limitations of Barriers and Enablers

Maxwell (2013) identifies several pitfalls in developing qualitative research questions. The questions may be too broad and provide insufficient guidance or so specific that they create ‘tunnel vision’ which neglects important conceptual and practical aspects of the phenomenon. Research questions can also ‘smuggle unexamined assumptions’ into the study or be developed in response to perceived scientific or strategic norms that do not serve the underlying research goals. We believe that the B&Es approach can suffer all these pitfalls. It is a poorly defined abstraction that is too broad to offer sound structural or conceptual guidance. Yet it gives the impression of a conceptual framework, deflecting researchers from critical thinking and exploration of other ways of seeing or conceptualising phenomena. Further, it is an untheorised framing device that often rests on unexamined assumptions yet, because it is familiar, is chosen as a ‘safe’ approach by inexperienced qualitative researchers and those who seek ways of making qualitative research appear more palatable to reviewers, funders, and quantitatively orientated colleagues. In the sections below, we explore some of our concerns about the dominance of the B&Es approach in more detail and suggest some alternatives and enhancements.

Barriers and Enablers Can Lead to Shallow Research Findings

Barriers and enablers studies tend to generate lists of ‘good things’ and ‘bad things’, often with a lack of in-depth analysis and little explanation of precisely what those things are (Checkland et al., 2007). When exploring and synthesising research data, it is necessary to ask what class of phenomenon they relate to: individual, interpersonal, cultural, organisational, or structural? These details have huge implications for change because they point to different leverage points and different intervention strategies. For example, we recall supervising a thematic analysis that identified a list of enablers to high-quality patient education which were, in fact, all adaptive strategies developed by health professionals in challenging circumstances. Research findings that recognise this and provide recommendations which build on frontline innovation and support the development of champions are likely to provide more applicable and strategic direction than a generalised conclusion that we should strengthen enablers (get better at doing the ‘good things’) and tackle barriers (reduce the ‘bad things’).

A key strength of qualitative research methods is that they are inherently flexible, exploratory, and responsive to the phenomena they seek to understand (Renjith et al., 2021). The use of inductive and abductive analysis allows researchers to learn from the data, both noting and responding to new concepts. However, the B&Es approach is often used as a static deductive structure that data must fit into. There is nothing inherently wrong with using deductive structures to guide qualitative research (as we illustrate below) providing they serve a clear purpose and, in most cases, are ‘held lightly’, allowing them to be critiqued in response to emergent concepts in the data. But using a simple B&Es framework may result in reductive analysis which does little more than code data as a ‘barrier’ or ‘enabler’ and avoids the ‘interpretive leap’ (seeking meaning within the data) that high quality qualitative research often demands (Braun & Clarke, 2023; Järvinen & Mik-Meyer, 2020).

Pope and Mays (2009) stress the need to push qualitative analysis beyond superficial descriptions towards the work of interpretation in which deeper meanings are surfaced:

Everyone thinks they can do qualitative research now, and I’m not always convinced we do justice to what we were trying to achieve when I started doing health research …. those papers that report thematic analyses. The kind that report six themes and don’t explain what the relationship is between the themes and so don’t really go anywhere in terms of trying to explain the data. Sometimes the problem is the word limits set by journals, but sometimes it’s just superficial work …. A real strength of qualitative research is induction – interpreting the data. That’s where you find the unexpected. I sometimes worry that we don’t push qualitative research far enough. I’d like it to be less descriptive and for us to try harder to explain things …. Checkland and colleagues highlighted this in their study of the implementation of clinical best practice guidelines in general practices. The GPs they interviewed listed commonsense implementation barriers such as lack of time. However their accounts could not be understood literally; instead, they related to the GPs’ underlying beliefs about how work should be allocated in a general practice and what it meant to be a GP. The things that stopped GPs implementing guidelines actually had little to do with information management and shortage of time, the main reasons they gave to the interviewer. (Pope & Mays, 2009)

Some studies treat the categories which dominate the data in B&Es studies as more important than infrequently coded concepts (Graham-Rowe et al., 2018). This implies (erroneously) that the frequency with which a concept is coded reveals something significant about its magnitude, regardless of the different classes of phenomena involved and their relations to one another. Codes in qualitative data analysis act as containers for concepts (Braun & Clarke, 2019). The higher the level or the more abstract the code, the more the data is likely to be attached to it. B&Es are very high level. This offers little guidance for priority-setting in relation to policy or practice change, or further research. As Bach-Mortensen and Verboom (2020) argue:

… simply describing the most frequently reported factors may produce overly simple representations of the underlying issue being investigated. In other words, identifying barriers and facilitators to health-related phenomena will not, in isolation, provide insights on how this outcome can be improved through intervention.

The categorisation of a barrier or enabler as products of the research process is seldom reflected on in B&E studies, despite the fact that a recent review of systematic reviews which used the B&Es approach found a tendency towards identifying more salient, common, uncontroversial, and easily communicated factors, as well as those in which primary study authors had an a priori interest (Bach-Mortensen & Verboom, 2020). This suggests that data collection and analysis approaches which frame the research topic in terms of B&Es may be likely to elicit safe, ‘top of mind’ responses that potentially neglect messier and more hidden aspects of human experience. Further, as interview and focus group studies framed using B&Es become more ubiquitous, they are more likely to produce familiar findings. Do we really need more studies that tell us that information alone is seldom a catalyst for change, that health professionals struggle to perform everything that is asked of them optimally due to lack of time, or that people are more inclined to exercise if it is enjoyable?

Barriers and Enablers Can Bypass Critical Reflexivity

There is a tendency for the B&Es approach to bypass critical thinking about different ways of seeing the topic of interest. Taking the example of process evaluation in intervention research, the B&Es approach asks ‘What is getting in the way (of this intervention or ideal behaviour)?’ and ‘What is assisting it?’ (Checkland et al., 2007). These may be valid questions, but they are far from the only questions we should be asking if we want to understand complex socially embedded phenomena. We need to think critically about target behaviours and the interventions designed to generate them, including how fit-for-purpose and desirable they are within different settings; however, as Wellstead argues, “Categorizing any factor or process as a ‘barrier’ reduces complex and highly dynamic decision-making into simplified, static, and metaphorical statements about why current outcomes are ‘incorrect’” (Wellstead et al., 2018).

Consequently, questions such as ‘Why does the problem happen this way?’, ‘What exceptions are there and what causes them?’, ‘What other perspectives are there?’, ‘What do stakeholders gain and/or lose with this intervention?’, ‘Does the intervention address this community’s priority concerns?’, ‘How socially credible is it?’ ‘Are there any unintended consequences/potential harms from this intervention?’, and ‘How can we generate broader/deeper understanding?’ may be equally valid, depending on the research topic, aims, and context. Crucially, qualitative researchers need to be responsive to the phenomena they seek to understand. This often means trying out different ways of seeing and thinking about phenomena as the research progresses, and new learning deepens our understanding and challenges previous assumptions. So perhaps a better generic starting point is to ask, ‘What is going on here? What matters to people?’ rather than ‘What are the barriers and enablers to X?’.

Barriers and Enablers Are Untheorised (But May Not Appear So)

Understanding the complex socially embedded phenomena that health research seeks to tackle often demands some engagement with theory (Lynch et al., 2018; Meyer & Ward, 2014; Willis et al., 2007). Theory may be held lightly as sensitising ideas or used as a conceptual guide that structures the research. Theory can provide a taxonomy for the description of phenomena that allows for systematic explanation, new hypotheses, or recommendations that can then be further tested (May & Finch, 2009). Alternatively, theory may be developed within the research such as with grounded theory and theory-driven methods like realist evaluation. Well-theorised qualitative research and evaluation has greater transferability, positions the study better within what is already known, and allows others to build on it more effectively than a-theoretical studies that produce a list of findings (Maxwell & Chmiel, 2014).

Barriers and enablers can act as a false friend in this regard, appearing to offer a ‘common-sense’ conceptual framework that, in reality, may be little more than a convenient heuristic or pathway metaphor comprising obstacles and aids, rather like a game of snakes and ladders. The B&Es approach provides an illusion of theory-informed qualitative analysis. If it can claim any theoretical basis, arguably, it would be that the approach is loosely underpinned by a linear-rationalist behavioural paradigm which posits that people will enact a desired behaviour (e.g., implement a clinical guideline, collaborate more effectively, attend a health service, exercise more, or use a new technology in their work) if obstacles are minimised or removed and/or facilitators are enhanced or introduced. This assumes that the target behaviour and the intervention used to encourage it are both appropriate and desirable, irrespective of individual and contextual variations. This stance tips towards a positivist, reductive world view which is largely incompatible with qualitative approaches that seek to shed light on messy intersubjective realities.

The B&Es approach is also unable to provide an objective, a-theoretical methodology. No human knowledge is developed in a theoretical vacuum: we are all products of our culture and perceive the world through the lens of social and historical contexts (Korstjens & Moser, 2017). Theories are always present in the knowledge-making of both qualitative and quantitative research, even when they are not acknowledged (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2014). Research questions, data collection instruments, and analytical methods are inevitably informed by researchers’ ideas about how the world works (ontology) and what we can know about it (epistemology). As Carter and Little (2007) point out:

A reflexive researcher actively adopts a theory of knowledge. A less reflexive researcher implicitly adopts a theory of knowledge, as it is impossible to engage in knowledge creation without at least tacit assumptions about what knowledge is and how it is constructed.

For example, when we (and our research participants) explain phenomena in terms of good/bad or what works/doesn’t work, it is important to consider whether these are ontologically ‘real’ phenomena at work in policy, practice, and everyday life settings, or if we are using ‘barriers’ and ‘enablers’ as a metaphor or heuristic that helps us cope with complex underlying realities (or something else altogether) (Bach-Mortensen & Verboom, 2020).

The Barriers and Enablers Approach Struggles to Engage With Context

A key strength of qualitative research is its ability to explore questions of how, why, and under what circumstances phenomena arise (Liamputtong, 2020). This involves considering how themes and contextual features relate to one another: are there associations, dependencies, nested relationships, and causalities? Is a barrier always a barrier – in all contexts, for all people, in all circumstances? What mechanisms are at play when factors become barriers or enablers, and how are they mediated by context? And how does a barrier or enabler manifest – what does obstruction or facilitation actually entail? (Bach-Mortensen & Verboom, 2020). The B&Es approach has a tendency to present findings without the contextual, historical, and process-focused specificity that can help to answer these questions.

This is a particular concern in implementation research which seeks to identify and enhance factors that contribute to implementation success. Understanding local interactions between implementation strategies, people, and context is central to this endeavour. However, the B&Es conceptualisation of implementation suggests a linear, unidirectional process of ‘transfer’ in which contextual features are ‘sources of obduracy and interference’ that impede smooth implementation (May et al., 2016). Yet, context is not something that happens around social phenomena such as an intervention; it is intrinsic to it. As Greenhalgh et al. (2004) note:

Context and “confounders” lie at the very heart of the diffusion, dissemination, and implementation of complex innovations. They are not extraneous to the object of study; they are an integral part of it. The multiple (and often unpredictable) interactions that arise in particular contexts and settings are precisely what determine the success or failure of a dissemination initiative.

Contexts, and the interventions that interact with them, are dynamic. Contextual factors such as ‘social influence’ or ‘organisational culture’ which constitute normal conditions of practice may appear as barriers in some places or at some times but function as facilitators in others (May et al., 2016). During COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, for example, rapid changes to social and policy contexts meant that community-based prevention programs were forced to adapt to extraordinary circumstances, shifting goals as well as program activities. New modes of program delivery necessitated system-level adaptations such as new partnerships and funding agreements which, in turn, affected further program design and delivery (Loblay et al., 2022). Thus, just as interventions are often adapted in local contexts, interventions may reshape contexts in unplanned and unexpected ways through their implementation (Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019). In organisational research, history and unfolding change within the organisation are vitally important for understanding social phenomena and designing and evaluating intervention and implementation strategies. In these studies, B&Es are usually identified from interviews or focus groups are considered to provide insights into participants’ experienced reality. However, these perceptions may change over time, including over the duration of an implementation process (Petersen et al., 2021).

Barriers and Enablers Encourage Binary Thinking That Is Ill-Suited to Complexity

B&Es are a heuristic device: a mental shortcut that allows a simplified representation of the world (Bach-Mortensen & Verboom, 2020). The approach presents a binary framework driven by a dualistic logic. A binary framework may appear to offer a way of cutting through complexity to identify simple, tangible solutions; yet there is increasing recognition of the need to understand and respond to complexity in the challenges faced by health services and public health more broadly (Crane et al., 2022; McDaniel et al., 2003). This draws on the seminal distinction between simple, complicated, and complex problems outlined in Box 1.

Box 1: Differences Between Simple, Complicated, and Complex Problems

• Simple problems are like baking a cake. If you have the right ingredients and measurements and follow the recipe, you will probably produce a successful cake every time.

• Complicated problems are like sending a rocket to the moon. There are many different aspects which require careful planning and coordination and expert input, often from multiple people. Unanticipated challenges may arise, but once you learn how to send a rocket to the moon, you can repeat the process. What worked before should work again.

• Complex problems are like raising a child. Raising one child can provide valuable expertise, but this is not sufficient because each child is unique and may require quite different approaches which will need to evolve as each child grows and circumstances change. We know it is possible to raise a child well, yet outcomes are uncertain. Some core strategies are always likely to be useful, but there is no formula.

Glouberman and Zimmerman argue that we can approach all these problems productively providing we understand which type of problem we aim to solve. They note, however, that healthcare experts often “... implicitly describe complex problems as complicated ones and hence employ solutions that are wedded to rational planning approaches. These often lead to inappropriate solutions because they neglect many aspects of complexity” (Glouberman & Zimmerman, 2002). Masking complexity seems particularly inapt given the ‘wicked’ nature of so many issues in health which are characterised by emergence, uncertainty, and flux (Holmes et al., 2017; Roberto et al., 2015).

The things we categorise as B&Es will often be complex factors in complex settings; however, this approach guides us towards seeing dichotomies rather than dynamics and thus treats problems as if they are complicated and can be solved by minimising the correct obstacles and/or maximising the correct facilitators. This can feed into assumptions that there are static problems and solutions and that a universally applicable gold standard ‘best practice’ is achievable when in fact ‘good practice’ or even ‘emergent practice’ is often a more appropriate way of conceptualising quality healthcare (Gray, 2017). As Dobrow points out, the Cochrane Collaboration argues that in most cases:

… universal guidelines and prescriptions for the precise application of the evidence are neither wise nor workable. Local disease burdens and barriers to implementation vary widely from country to country and from place to place within countries, and local attention to these issues will help to ensure that the evidence will help those who can best benefit from it. (Cited in Dobrow et al., 2006)

Implementation is especially complex, focusing on non-linear processes that operate in dynamic, open systems across multiple levels. Research must attend to this complexity if we are to understand the conditions necessary for a successful intervention or policy (Hoddinott et al., 2010). Factors that affect outcomes are likely to change over time and in different contexts, and may be perceived differently by individuals, disciplines, and epistemic communities, to the extent that a barrier may become an enabler in some circumstances, and vice versa, or phenomena can be barriers and enablers.

The B&Es approach, however, often assumes a linear relationship between determinants and intervention outcomes and ignores how individual B&Es may be interacting and evolving: “For instance, there could be synergistic effects such that two seemingly minor barriers constitute an important obstacle to successful outcomes if they interact” (Nilsen, 2015). The complexity-attuned literature on fidelity assessment in process evaluation now focuses on the function (process effects) of an intervention rather than solely on its programmatic form and has shifted attention away from questions about implementation of B&Es towards interest in how interventions are championed, adapted, and reinterpreted in different contexts (Hawe, 2015; Loblay et al., 2022; Skivington et al., 2021). Bach-Mortensen and Verboom (2020) raise similar concerns about systematic reviews “… reducing potentially complex phenomena into simplified, discrete factors,” noting that in their metareview they found, “Few included studies critically investigated the potential dynamic features of and between identified factors and their contextual variability, even though this was commonly acknowledged to be an important feature of the barrier and facilitator concepts.”

Alternatives and Enhancements to the Barriers and Enablers Approach

There are many alternatives to the B&Es approach, most of which can also be used to enhance inquiry into B&Es by providing conceptual and methodological ‘scaffolding’. Here, we focus on pragmatic strategies for researchers who seek alternatives or strategies for enhancement. The latter may be because the researchers are not yet ready to embark on B&Es-free research due to unfamiliarity with qualitative traditions, or they are experiencing institutional pressure to use this apparently ‘safe’ approach, or because framing research questions in terms of B&Es seems appropriate for their study but could be strengthened.

Consider a ‘Whole Package’ Research Methodology

Unlike thematic analysis or content analysis which are a-theoretical and can be used in very different ways according to the research’s theoretical framework, some research approaches using qualitative methods provide a whole methodology. That is, in addition to the methods (what you are doing), they provide a rationale and theoretical basis for the overarching research strategy (why you are doing it that way). Grounded theory, phenomenology, realist evaluation, photovoice, and soft systems methodology are just some examples. These approaches can suggest alternatives to B&Es for framing research questions and design but can also accommodate an exploration of B&Es. For example, Huntingdon et al. (2020) explored B&Es within a grounded theory study which built a conceptual model that describes the process of sexual adjustment to HIV and intervention points for providing support. Erdem et al. (2020) conducted an interpretative phenomenological study exploring B&Es associated with male mental health help-seeking to develop in-depth understating around themes which included ‘denial as preservation’. Labbé et al. (2021) explored B&Es to social inclusion of people with disabilities using photovoice’s participatory methodology to develop themes such as ‘the paradox of accessibility’ which examines conflicting needs, while King et al. (2023) “go beyond a simple listing of barriers and facilitators” to identify context–mechanism–outcome configurations in their realist evaluation of AI use in pathology. Many realist studies also incorporate an investigation of B&Es, but the inquiry is underpinned by questions of what works for whom and under what circumstances (Fletcher et al., 2016). Realist evaluation also helps researchers “avoid being overwhelmed by the enormity of potentially important contextual factors by focusing on … [those] that affect the mechanisms ‘sparked’ (or inhibited) by an intervention …. rather than asking generic questions about contextual enablers and barriers” (Punton et al., 2020).

Use Theories and Conceptual Frameworks to Guide the Research

Formal theories and conceptual frameworks can offer an alternative way of guiding research questions, data collection, and analysis which can also increase the transferability of research findings (Willis et al., 2007). As Meyer and Ward (2014) argue, “The role of theory in qualitative health research is paramount for translation into practice and policy, since it moves beyond pure description of data, allowing interpretation of the social processes underpinning and potentially ‘explaining’ findings.” Importantly, theories and conceptual frameworks help researchers explore the relationships between concepts in their data and think critically about data that might be overlooked, misinterpreted, or uninterrogated without a theoretical framework (Collins & Stockton, 2018), including paying attention to political and power dynamics (Huffman & Tracy, 2018). For example, in their study of obesity in Cuba and Samoa, Garth and Hardin (2019) reject focusing on barriers to weight management. They argue that previous studies using a barriers lens conflated different classes of phenomena and risked compounding stigma and disempowerment because of the inherent assumption that once barriers are identified they should be surmountable and when they are not overcome, the individual is to blame. Instead, they use social visibility as an analytic lens to critique the persistent failure of most obesity interventions and draw on concepts that seek to explain contextual factors such as obesogenic environments.

Bacchi offers an analytic strategy for interrogating ‘solutions’ to social problems which is particularly helpful for planning and guiding research. The ‘What’s the Problem Represented to Be?’ approach comprises six questions that provoke critical scrutiny of how policies and programs implicitly frame (represent) the problems they purport to be tackling. The questions support researchers to examine problem and solution representations as socio-political constructions with power implications rather than natural phenomena which are ‘out there’ waiting to be discovered (Bacchi, 2012, 2016). A recent study using this approach analysed the representation of problems underpinning the introduction of routine mental health outcome measures, highlighting their neglect of social determinants of mental health in meeting consumer needs and expectations (Oster et al., 2023).

A priori theories and models such as self-determination theory (Tettero et al., 2022), social-ecological approaches (Brutzman et al., 2022; Lun et al., 2022), normalisation process theory (Kousgaard et al., 2022; Simpson et al., 2018), the theoretical domains framework and associated COM-B model (Akiba et al., 2022; Handley et al., 2016; McDermott et al., 2022; Petersen et al., 2021), and social cognitive theory (Fuller et al., 2019; van Rijen & ten Hoor, 2023) can also accommodate an exploration of B&Es, situating them within a broader conceptual context and ensuring attention is paid to different levels, classes, and dimensions of the phenomena, as well as providing a way of theorising about how the B&Es relate to one another. Critical perspectives which attend to structural inequities and power-based features, such as critical disability theory, can also be incorporated and have particular value in challenging cultural assumptions and revealing systemic barriers (Aylsworth et al., 2022; Lin & Melendez-Torres, 2017; Naidu et al., 2023). For example, van Heesewijk et al. (2022) use queer theory as a theoretical lens to investigate B&Es to implementation of transgender health education in medical school curricula, identifying normative gender ideologies that classify transgender people as ‘unhealthy Others’.

There are well-described frameworks for constructing effective qualitative research questions for clinical studies and research syntheses (Bennett & Bennett, 2000; Foster & Jewell, 2017) (including a useful overview provided here: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR/research_question). And implementation science boasts a huge range of tools for guiding nuanced implementation planning and evaluation (e.g., Proctor et al. (2011)). These include process models, determinant frameworks, classic theories, implementation theories, and evaluation frameworks (Nilsen, 2015). Researchers can use an open access website to select the most appropriate tool: https://dissemination-implementation.org/tool, and Lynch et al. provide guidance related to the ‘top ten’ approaches (Lynch et al., 2018). At the very least, a B&Es approach should be augmented with careful attention to acceptability. Sekhon et al.’s framework for evaluating acceptability of healthcare interventions is useful here as it includes concepts that B&Es may not capture such as feasibility, affective responses to the intervention, and opportunity costs (Sekhon et al., 2017). Tools are also available for assessment and planning of public health and clinical program sustainability in relation to key success factors: a more sophisticated way to consider ‘enablers’ (Center for Public Health Systems Science, 2023).

Use Participatory Methods to Better Understand Participants’ Lived Experiences

Researchers adopting a critical stance often strive to use their work and the process of conducting it as a tool for emancipation and so may prefer participatory or action research designs where participants become co-researchers (Pope & Mays, 2020). This is an especially important approach for populations who have been disenfranchised by traditional methods of research, such as First Nations people (Baum et al., 2006). Research which is co-produced in partnership with stakeholders asks questions that are most relevant to them, provides richer insights, and facilitates research translation because stakeholders are invested in the process and outcomes. Specific participatory action research methods such as health impact assessment (den Broeder et al., 2017), photovoice (Walker et al., 2020), soft systems thinking (Checkland & Poulter, 2007), and Our Voice citizen science (Wood et al., 2023) can provide a methodological framework which could be used instead of, or to enhance, a B&Es approach.

Use Sensitising Concepts to Guide Inquiry

Those who do not wish to adopt a full flung theory or to be constrained by an existing framework can engage with sensitising concepts: ‘background ideas’ that provide a point of departure for developing the research question and design without directing the scope or shape of the work (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2014; Kraus, 2018; Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). Again, these concepts may enable researchers to identify alternative approaches to B&Es, or they can be used to enhance a B&Es inquiry. For example, a study of B&Es to social inclusion experienced by children with disability which is informed by the social model of disability – in which environments are regarded as enabling or disabling (Barnes, 2003) – is far more likely to highlight structural and socio-political barriers than one which is informed by a biomedical model.

Qualitative research that investigates or explores interventions in health services could benefit from attention to sensitising ideas in the organisational and knowledge mobilisation literature. These include sensemaking (Weick, 1995), organisational learning (Argote, 2011), communities of practice (Brown & Duguid, 2001; le May, 2009), and various models of research utilisation that expose the fallacy of linear pipeline models of knowledge transfer (for which a B&Es inquiry would be appropriate) and focus instead on social, discursive models of knowledge transformation in context (Brown & Duguid, 2001; Glasgow et al., 2012; Haynes et al., 2011; Nutley et al., 2007; Weiss & Bucuvalas, 1980). Ecological metaphors and key ideas from systems thinking can help researchers move away from these unhelpful mechanistic or linear conceptions of change processes. These approaches raise questions such as: How does change happen in this setting? Do the people targeted accept the premise of the intervention/desired behavioural change? How does it intersect with their personal or professional identity, autonomy, values, wishes, and circumstances (what’s in it for them?)? How do people make sense of it? How is knowledge shared and legitimised in this setting? These questions may be particularly suited to understanding new interventions that have not been co-designed where researchers may have overlooked some of messier and inconveniently human aspects of the phenomena.

An example of research informed by a community-of-practice lens is the ethnographic study of guidelines use in GP practices conducted by Gabbay and le May (2004, 2011, 2016). Rather than asking what the B&Es were to using guidelines, the researchers sought to explore how GPs made everyday healthcare decisions in their practices. They found GPs developed ‘mindlines’: personal ‘guidelines-in-the-head’ that melded evidence from myriad sources with tacit knowledge, contextual understanding, and continual learning – shaped by coffee-room chats with colleagues – to form an internalised guide to practise. These findings illuminate the fluidity of ‘knowledge-in-practice-in-context’ in everyday healthcare and provide new ways of thinking about how to facilitate the use of guidelines in primary care.

Advance Existing Work on Barriers and Enablers

The existing literature provides many examples of B&Es that have been identified in previous studies, often repeatedly. This literature could be advanced in several ways:

Investigate How an Identified Barrier or Enabler Works in Depth

A commonly cited barrier to implementing interventions introduced in organisational settings such as hospitals and clinics is a lack of time. Findings typically reflect a sense among staff that they lack capacity to take on anything new but seldom examine this critically. Yet there may be numerous structural, systemic, or individual factors underlying this experience of ‘lack of time’ which are not volunteered (or even perceived) by participants. What if, for example, the ‘rush culture’ has convinced health staff that hospitals are not appropriate sites for health promotion (Kelley & Abraham, 2007) or that staff feel the need to be seen to be working at capacity irrespective of ebbs and flows in their practice? What if the underlying problem is burnout or compassion fatigue, or deep resentment about workplace dynamics, but it’s too hard to say those things? Thus, concepts of time – as with other B&Es – might better be understood not only in terms of good/bad but also as a point of departure for further analysis. This includes questioning the assumption that more time is needed at all. Légaré et al. (2008) address this in their systematic review of shared decision-making in clinical practice in which lack of time was identified as a ‘universal perceived barrier’. However, they note that:

… there is no robust evidence that compared to usual care, more time is required to engage in shared decision-making in clinical practice …. Therefore, it remains essential that future studies investigate whether engaging in shared decision-making actually takes more time or not ...

Whelehan et al.’s (2021) study of barriers to reducing fatigue in surgeons exemplifies this approach. They sought to better understand the problem of fatigue, asking about its causes and impacts, in order to rethink possible solutions including individual, team-based, and environmental-level interventions.

Develop and Test Implementation Strategies for Addressing Barriers and/or Enablers

Descriptive studies of B&Es frequently conclude with high-level recommendations about possible intervention strategies, but these may be left dangling with no research efforts to operationalise, implement, and evaluate them. Thompson and Reeve (2022) highlight this gap in the literature in their study of deprescribing in which they state that much research in this field:

… focused on identifying barriers to and facilitators of deprescribing in clinical practice … However, with continuing research around barriers and facilitators, we need to be mindful to undertake research that builds on existing knowledge, addresses known gaps, and advances the field … [by] translating existing knowledge into strategies and tools that can impact clinical practice and lead to practical and sustained deprescribing …

Martin Ginis et al. (2016) make a similar point in relation to studies of physical activity participation by people with physical disability:

… we urge researchers to move beyond conducting simple descriptive studies. If the ultimate goal is to increase LTPA [leisure-time physical activity] participation, then it is time to focus on selecting, developing, testing, and implementing interventions, rather than simply generating lists of barriers and facilitators. For this to occur, researchers must be able to address a variety of barriers/facilitators that cut across multi-level, multi-sector structures.

Use the Existing Barriers and Enablers Literature to Develop a New Model or Theory

Given the plethora of B&Es studies, synthesis of this literature may be warranted. Herber et al. (2019) used meta-synthesis techniques to integrate identified barriers and facilitators to heart failure self-care and developed a new theoretical model expressed in a series of propositions that can be tested in further research. Noyes et al. (2014) developed a model for reconceptualising children’s complex discharge, drawing on B&Es and existing theory. Nilson (2015) points out that many frameworks that focus on implementation determinants were developed synthesising results from empirical studies of B&Es to implementation success.

Conclusion

There are strengths and weaknesses to all approaches. This commentary seeks to highlight some weaknesses to the B&Es approach to encourage researchers to think critically about using it to frame their research questions. Arguments as to the strengths of the B&Es approach are not required here due to its dominance in health research. We argue that the relative simplicity and ‘common-sense’ feel of B&Es may be a false friend, appearing to offer a pragmatic framework for inquiry and analysis but leading to research which is shallow and untheorised and which fails to really engage with critical reflexivity, context, or complexity.

Myriad alternatives are available, drawing on the rich, diverse, and often creative traditions that comprise qualitative research. We encourage researchers to read widely and explore the vast range of approaches in order to develop research questions that are most meaningful and fit-for-purpose in their context. If B&Es are to be included, we suggest they are scaffolded with methodologies, theories, frameworks, or sensitising concepts. This could be supplemented with conversations with colleagues in other disciplines and fields, and with stakeholders with professional or lived expertise who can reveal new ways of thinking about what really matters and how it can best be researched. Forming the right research questions should be seen as an iterative process that occurs through critical thinking and refining ones ideas at all stages of the research process (Maxwell, 2013). We invite further discussion on this topic.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the qualitative communities of practice at the Institute for Musculoskeletal Health and the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre where we presented some of the ideas in this paper and received feedback that contributed to its development. Thanks also to Louise Nash for discussing an early draft of this paper.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Abby Haynes https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5703-5683

Victoria Loblay https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4094-9619

References

- Akiba C. F., Powell B. J., Pence B. W., Muessig K., Golin C. E., Go V. (2022). “We start where we are”: A qualitative study of barriers and pragmatic solutions to the assessment and reporting of implementation strategy fidelity. Implementation Science Communications, 3(1), 117. 10.1186/s43058-022-00365-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argote L. (2011). Organizational learning research: Past, present and future. Management Learning, 42(4), 439–446. 10.1177/1350507611408217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aylsworth L., Manca T., Dubé È., Labbé F., Driedger S. M., Benzies K., MacDonald N., Graham J., MacDonald S. E. (2022). A qualitative investigation of facilitators and barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines among Racialized and Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(6), Article 2129827. 10.1080/21645515.2022.2129827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi C. (2012). Introducing the ‘What's the Problem Represented to be?’ approach. In Bletsas A., Beasley C. (Eds.), Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic interventions and exchanges (pp. 21–24). The University of Adelaide Press. 10.1017/UPO9780987171856.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi C. (2016). Problematizations in health policy: Questioning how “problems” are constituted in policies. Sage Open, 6(2), 2158244016653986. 10.1177/2158244016653986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bach-Mortensen A. M., Verboom B. (2020). Barriers and facilitators systematic reviews in health: A methodological review and recommendations for reviewers. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(6), 743–759. 10.1002/jrsm.1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. (2003). What a difference a decade makes: Reflections on doing ‘emancipatory’ disability research. Disability & Society, 18(1), 3–17. 10.1080/713662197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baum F., MacDougall C., Smith D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(10), 854–857. 10.1136/jech.2004.028662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S., Bennett J. W. (2000). The process of evidence-based practice in occupational therapy: Informing clinical decisions. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 47(4), 171–180. 10.1046/j.1440-1630.2000.00237.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C., Taylor J., Herber O. (2014). How theory is used and articulated in qualitative research: Development of a new typology. Social Science & Medicine, 120(November), 135–141. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2019). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 1–16. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2023). Is thematic analysis used well in health psychology? A critical review of published research, with recommendations for quality practice and reporting. Health Psychology Review, 17(4), 694–718. 10.1080/17437199.2022.2161594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. S., Duguid P. (2001). Knowledge and organization: A social-practice perspective. Organization Science, 12(2), 198–213. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3086055 [Google Scholar]

- Brutzman B., Bustos T. E., Hart M. J., Neal J. W. (2022). A new wave of context: Introduction to the special issue on socioecological approaches to psychology. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 8(2), 177–184. 10.1037/tps0000337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S. M., Little M. (2007). Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: Epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1316–1328. 10.1177/1049732307306927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Public Health Systems Science . (2023). The program sustainability assessment tool. Brown School, Washington University. https://sustaintool.org [Google Scholar]

- Checkland K., Harrison S., Marshall M. (2007). Is the metaphor of ‘barriers to change' useful in understanding implementation? Evidence from general medical practice. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 12(2), 95–100. 10.1258/135581907780279657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkland P., Poulter J. (2007). Learning for action: A short definitive account of soft systems methodology, and its use for practitioners, teachers and students. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. S., Stockton C. M. (2018). The central role of theory in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1609406918797475. 10.1177/1609406918797475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crane M., Nathan N., McKay H., Lee K., Wiggers J., Bauman A. (2022). Understanding the sustainment of population health programmes from a whole-of-system approach. Health Research Policy and Systems, 20(1), 37. 10.1186/s12961-022-00843-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Broeder L., Uiters E., ten Have W., Wagemakers A., Schuit A. J. (2017). Community participation in Health Impact Assessment. A scoping review of the literature. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 66(September), 33–42. 10.1016/j.eiar.2017.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrow M. J., Goel V., Lemieux-Charles L., Black N. A. (2006). The impact of context on evidence utilization: A framework for expert groups developing health policy recommendations. Social Science & Medicine, 63(7), 1811–1824. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdem H., Wilson G., Limbrick H., Swainston K. (2020, November). An interpretive phenomenological exploration of the barriers, facilitators and benefits to male mental health help-seeking. BPS North of England Bulletin. https://shop.bps.org.uk/the-north-of-england-bulletin-issue-1-spring-2020-19369.html [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher A., Jamal F., Moore G., Evans R. E., Murphy S., Bonell C. (2016). Realist complex intervention science: Applying realist principles across all phases of the Medical Research Council framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions. Evaluation, 22(3), 286–303. 10.1177/1356389016652743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster M. J., Jewell S. T. (2017). Assembling the pieces of a systematic review : Guide for librarians. Rowman & Littlefield. https://lib.myilibrary.com?id=992315 [Google Scholar]

- Fuller A. B., Byrne R. A., Golley R. K., Trost S. G. (2019). Supporting healthy lifestyle behaviours in families attending community playgroups: Parents’ perceptions of facilitators and barriers. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1740. 10.1186/s12889-019-8041-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay J., le May A. (2004). Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. BMJ, 329(7473), 1013. 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay J., le May A. (2011). Practice-based evidence for healthcare: Clinical mindlines. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay J., le May A. (2016). Mindlines: Making sense of evidence in practice. British Journal of General Practice, 66(649), 402–403. 10.3399/bjgp16X686221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garth H., Hardin J. (2019). On the limitations of barriers: Social visibility and weight management in Cuba and Samoa. Social Science & Medicine, 239(October), Article 112501. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Green L. W., Taylor M. V., Stange K. C. (2012). An evidence integration triangle for aligning science with policy and practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(6), 646–654. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glouberman S., Zimmerman B. (2002). Complicated and complex systems: What would successful reform of medicare look like? (Vol. 8). Commission on the future of health care in Canada Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Rowe E., Lorencatto F., Lawrenson J. G., Burr J. M., Grimshaw J. M., Ivers N. M., Presseau J., Vale L., Peto T., Bunce C., Francis J. J. (2018). Barriers to and enablers of diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: A systematic review of published and grey literature. Diabetic Medicine, 35(10), 1308–1319. 10.1111/dme.13686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray B. (2017). The Cynefin framework: Applying an understanding of complexity to medicine. Journal of Primary Health Care, 9(4), 258–261. 10.1071/HC17002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Robert G., Macfarlane F., Bate P., Kyriakidou O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley M. A., Harleman E., Gonzalez-Mendez E., Stotland N. E., Althavale P., Fisher L., Martinez D., Ko J., Sausjord I., Rios C. (2016). Applying the COM-B model to creation of an IT-enabled health coaching and resource linkage program for low-income Latina moms with recent gestational diabetes: The STAR MAMA program. Implementation Science, 11(1), 73. 10.1186/s13012-016-0426-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P. (2015). Lessons from complex interventions to improve health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36(1), 307–323. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes A., Gillespie J. A., Derrick G. E., Hall W. D., Sally R., Simon C., Heidi S. (2011). Galvanizers, guides, champions, and shields: The many ways that policymakers use public health researchers. The Milbank Quarterly, 89(4), 564–598. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00643.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herber O. R., Kastaun S., Wilm S., Barroso J. (2019). From qualitative meta-summary to qualitative meta-synthesis: Introducing a new situation-specific theory of barriers and facilitators for self-care in patients with heart failure. Qualitative Health Research, 29(1), 96–106. 10.1177/1049732318800290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P., Britten J., Pill R. (2010). Why do interventions work in some places and not others: A breastfeeding support group trial. Social Science & Medicine, 70(5), 769–778. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes B. J., Best A., Davies H., Hunter D., Kelly M. P., Marshall M., Rycroft-Malone J. (2017). Mobilising knowledge in complex health systems: A call to action. Evidence & Policy, 13(3), 539–560. 10.1332/174426416X14712553750311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman T., Tracy S. J. (2018). Making claims that matter: Heuristics for theoretical and social impact in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(8), 558–570. 10.1177/1077800417742411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huntingdon B., Sharpe L., de Wit J., Duracinsky M., Juraskova I. (2020). A new grounded theory model of sexual adjustment to HIV: Facilitators of sexual adjustment and recommendations for clinical practice. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20(1), 31. 10.1186/s12879-019-4727-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järvinen M., Mik-Meyer N. (2020). Qualitative analysis: Eight approaches for the social sciences (1st ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K., Abraham C. (2007). Health promotion for people aged over 65 years in hospitals: Nurses’ perceptions about their role. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(3), 569–579. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King H., Wright J., Treanor D., Williams B., Randell R. (2023). What works where and how for uptake and impact of artificial intelligence in pathology: Review of theories for a realist evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, Article e38039. 10.2196/38039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korstjens I., Moser A. (2017). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 2: Context, research questions and designs. The European Journal of General Practice, 23(1), 274–279. 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousgaard M. B., Olesen J. A., Arnold S. H. (2022). Implementing an intervention to reduce use of antibiotics for suspected urinary tract infection in nursing homes—A qualitative study of barriers and enablers based on normalization process theory. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 265. 10.1186/s12877-022-02977-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus R. (2018). Qualitative research and interviewing. In Kite M. E., Whitley B. E., Kraus R. (Eds.), Principles of research in behavioral science (4th ed., pp. 531–566). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Labbé D., Mahmood A., Routhier F., Prescott M., Lacroix É., Miller W. C., Mortenson W. B. (2021). Using photovoice to increase social inclusion of people with disabilities: Reflections on the benefits and challenges. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(1), 44–57. 10.1002/jcop.22354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le May A. (2009). Communities of practice in health and social care. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Légaré F., Ratté S., Gravel K., Graham I. D. (2008). Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: Update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Education and Counseling, 73(3), 526–535. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong P. (2020). Qualitative inquiry. In Liamputtong P. (Ed.), Qualitative research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Melendez-Torres G. J. (2017). Critical interpretive synthesis of barriers and facilitators to TB treatment in immigrant populations. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 22(10), 1206–1222. 10.1111/tmi.12938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loblay V., Garvey K., Shiell A., Kavanagh S., Hawe P. (2022). Can adaptation to ‘extraordinary’ times teach us about ways to strengthen community-based chronic disease prevention? Insights from the COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Public Health, 32(1), 127–138. 10.1080/09581596.2021.2006147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lun P., Gao J., Tang B., Yu C. C., Jabbar K. A., Low J. A., George P. P. (2022). A social ecological approach to identify the barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 vaccination acceptance: A scoping review. PLoS One, 17(10), Article e0272642. 10.1371/journal.pone.0272642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch E. A., Mudge A., Knowles S., Kitson A. L., Hunter S. C., Harvey G. (2018). “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”: A pragmatic guide for selecting theoretical approaches for implementation projects. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 857. 10.1186/s12913-018-3671-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Ginis K. A., Ma J. K., Latimer-Cheung A. E., Rimmer J. H. (2016). A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychology Review, 10(4), 478–494. 10.1080/17437199.2016.1198240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J. A. (2013). Research questions: What do you want to understand? In Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed., pp. 73–86). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J. A., Chmiel M. (2014). Generalization in and from qualitative analysis. In Uwe F. (Ed.), The Sage handbook of qualitative data analysis (p. 540). Sage Publications Ltd. 10.4135/9781446282243.n37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- May C., Finch T. (2009). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554. 10.1177/0038038509103208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- May C. R., Johnson M., Finch T. (2016). Implementation, context and complexity. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel J. R. R., Jordan M. E., Fleeman B. F. (2003). Surprise, surprise, surprise! A complexity science view of the unexpected. Health Care Management Review, 28(3), 266–278. 10.1097/00004010-200307000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott G., Brick N. E., Shannon S., Fitzpatrick B., Taggart L. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in adolescents with intellectual disabilities: An analysis informed by the COM-B model. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 35(3), 800–825. 10.1111/jar.12985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S., Ward P. (2014). ‘How to' use social theory within and throughout qualitative research in healthcare contexts. Sociology Compass, 8(5), 525–539. 10.1111/soc4.12155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu J., Paolucci E. O., Turin T. C. (2023). A critical lens on health: Key principles of critical discourse analysis and its benefits to anti-racism in population public health research. Societies, 13(2), 42. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/13/2/42 [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes J., Brenner M., Fox P., Guerin A. (2014). Reconceptualizing children's complex discharge with health systems theory: Novel integrative review with embedded expert consultation and theory development. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(5), 975–996. 10.1111/jan.12278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutley S. M., Walter I., Davies H. T. (2007). Using evidence: How research can inform public services. The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oster C., Dawson S., Kernot J., Lawn S. (2023). Mental health outcome measures in the Australian context: What is the problem represented to be? BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 24. 10.1186/s12888-022-04459-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen H. V., Sivertsen D. M., Jørgensen L. M., Petersen J., Kirk J. W. (2021). From expected to actual barriers and facilitators when implementing a new screening tool: A qualitative study applying the theoretical domains framework. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(11-12), 2867–2879. 10.1111/jocn.16410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C., Mays N. (2009). Critical reflections on the rise of qualitative research. BMJ, 339, b3425. 10.1136/bmj.b3425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C., Mays N. (2020). The role of theory in qualitative research. In Pope C., Mays N. (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care (4th ed., pp. 15–26). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Griffey R., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punton M., Isabel V., Leavy J., Michaelis C., Boydell E. (2020). Reality bites: Making realist evaluation useful in the real world (CDI practice paper). https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/reality-bites-making-realist-evaluation-useful-in-the-real-world/

- Renjith V., Yesodharan R., Noronha J. A., Ladd E., George A. (2021). Qualitative methods in health care research. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 12(20), 20. 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_321_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T., Lancaster K. (2019). Evidence-making interventions in health: A conceptual framing. Social Science & Medicine, 238(October), Article 112488. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto C. A., Swinburn B., Hawkes C., Huang T. T. K., Costa S. A., Ashe M., Zwicker L., Cawley J. H., Brownell K. D. (2015). Patchy progress on obesity prevention: Emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. The Lancet, 385(9985), 2400–2409. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61744-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon M., Cartwright M., Francis J. J. (2017). Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 88. 10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson R., Simpson S., Wood K., Mercer S. W., Mair F. S. (2018). Using normalisation process theory to understand barriers and facilitators to implementing mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illness, 15(4), 306–318. 10.1177/1742395318769354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skivington K., Matthews L., Simpson S. A., Craig P., Baird J., Blazeby J. M., Boyd K. A., Craig N., French D. P., McIntosh E., Petticrew M., Rycroft-Malone J., White M., Moore L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of medical research council guidance. BMJ, 374, n2061. 10.1136/bmj.n2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettero O. M., Westerman M. J., van Stralen M. M., van den Beuken M., Monpellier V. M., Janssen I. M. C., Steenhuis I. H. M. (2022). Barriers to and facilitators of participation in weight loss intervention for patients with suboptimal weight loss after bariatric surgery: A qualitative study among patients, physicians, and therapists. Obesity Facts, 15(5), 674–684. 10.1159/000526259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson W., Reeve E. (2022). Deprescribing: Moving beyond barriers and facilitators. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 18(3), 2547–2549. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans S., Tavory I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186. 10.1177/0735275112457914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Heesewijk J., Kent A., van de Grift T. C., Harleman A., Muntinga M. (2022). Transgender health content in medical education: A theory-guided systematic review of current training practices and implementation barriers & facilitators. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 27(3), 817–846. 10.1007/s10459-022-10112-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijen D., ten Hoor G. A. (2023). A qualitative analysis of facilitators and barriers to physical activity among patients with moderate mental disorders. Journal of Public Health, 31, 1401–1416. 10.1007/s10389-022-01720-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A., Colquitt G., Elliott S., Emter M., Li L. (2020). Using participatory action research to examine barriers and facilitators to physical activity among rural adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disability & Rehabilitation, 42(26), 3838–3849. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1611952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C. H., Bucuvalas M. J. (1980). Truth tests and utility tests: Decision-makers' frames of reference for social science research. American Sociological Review, 45(2), 302–313. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2095127 [Google Scholar]

- Wellstead A., Biesbroek R., Cairney P., Davidson D., Dupuis J., Howlett M., Rayner J., Stedman R. (2018). Comment on “Barriers to enhanced and integrated climate change adaptation and mitigation in Canadian forest management”. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 48(10), 1241–1245. 10.1139/cjfr-2017-0465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whelehan D. F., Brown D. J., Connelly T. M., Ridgway P. F. (2021). Fatigued surgeons: A thematic analysis of the causes, effects and opportunities for fatigue mitigation in surgery. International Journal of Surgery Open, 35(September), Article 100382. 10.1016/j.ijso.2021.100382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis K., Daly J., Kealy M., Small R., Koutroulis G., Green J., Gibbs L., Thomas S. (2007). The essential role of social theory in qualitative public health research. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 31(5), 438–443. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood G., Pykett J., Banchoff A., King A., Stathi A. & Improving Your Local Area Citizen Scientists and Community Stakeholders (2023). Employing citizen science to enhance active and healthy ageing in urban environments. Health & Place, 79(January), Article 102954. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2022.102954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]