Abstract

Background

Both the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, a predictor of insulin resistance (IR), and inflammation are risk factors for stroke in hypertensive patients. However, only a handful of studies have coupled the TyG index and inflammation indices to predict stroke risk in hypertensive patients. The C-reactive protein-triglyceride-glucose index (CTI) is a novel marker that comprehensively assesses the severity of IR and inflammation. The present study explored the association between CTI and the risk of stroke in patients with hypertension.

Methods

A total of 3,834 hypertensive patients without a history of stroke at baseline were recruited from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Multivariate Cox regression and restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses were employed to assess the relationship between CTI and stroke risk in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the Boruta algorithm was applied to evaluate the importance of CTI and construct prediction models to forecast the incidence of stroke in the study cohort.

Results

After 7 years of follow-up, the incidence of stroke in hypertensive patients was 9.6% (368 cases). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed a 21% increase in stroke risk with an increase in each CTI unit (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.08–1.37). The top quartile group was 66% more likely to have a stroke than the bottom quartile group (HR = 1.66, 95% CI = 1.23–2.25). RCS analysis confirmed a linear relationship between CTI and stroke risk. The Boruta algorithm validated CTI as a crucial indicator of stroke risk. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) survival model exhibited the best predictive performance for stroke risk in hypertensive patients, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.956.

Conclusions

An increase in CTI levels is associated with a higher risk of stroke in hypertensive patients. This study suggests that CTI may emerge as a unique predictive marker for stroke risk.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13098-024-01529-z.

Keywords: Stroke, C-reactive protein-triglyceride-glucose index, Hypertension, Inflammation, Insulin resistance

Introduction

Stroke is a major public health concern worldwide. According to the 2021 estimates, the total number of stroke cases has exceeded 100 million globally, with over 7.3 million stroke-related fatalities per year, making it the third leading cause of death worldwide [1]. It is projected that stroke-related mortality may escalate to 9.7 million by 2050, creating significant global financial pressure [2]. High systolic blood pressure is one of the most significant risk factors for stroke, accounting for 56.8% of all stroke-related poor outcomes [1]. Chronic hypertension leads to vascular remodeling, atherosclerosis or plaque formation, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress, which all contribute to the development of stroke [3]. Consequently, early diagnosis of stroke risk in hypertensive individuals is critical for stroke prevention and improved patient outcomes.

Insulin resistance (IR) is defined as a decline in the body’s insulin sensitivity that affects glucose absorption and utilization [4]. IR is associated with metabolic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. IR impairs endothelial cell function in hypertensive individuals by promoting inflammation, oxidative stress, and platelet adhesion and aggregation, leading to the formation of thrombi [5]. IR-induced metabolic dysfunction also accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis [6]. Both thrombus and plaque formation play crucial roles in stroke development [7]. In recent years, the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, an emerging index for assessing IR [8], has been closely associated with hypertension [9], atherosclerosis [10], stroke [11], and the poor prognosis of cardiovascular diseases [12, 13]. Additionally, inflammation has been recognized as a risk factor for stroke [14]. Hypertension is correlated with elevated levels of inflammatory markers, which promote vasculopathy and thrombosis, ultimately contributing to poor stroke outcomes [15]. The non-specific inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (CRP) has emerged as a promising biomarker for stroke risk assessment [16, 17].

Although the TyG index has been used to predict stroke risk in hypertensive patients, the effect of inflammation on stroke risk is often overlooked [18, 19]. Considering that both IR and inflammation are strongly associated with the occurrence of adverse stroke outcomes in hypertensive patients, developing a composite index as a predictive tool is paramount. The C-reactive protein-triglyceride-glucose index (CTI) developed by Ruan et al. combined inflammation and IR to predict survival in cancer patients [20]. Accumulating evidence has supported CTI application as a measure of inflammation and IR. CTI demonstrated good predictive value in predicting the prognosis of patients with cancer cachexia [21], cancer mortality in the general population [22], and the risk of erectile dysfunction [23].

Therefore, the present study sought to investigate the effectiveness of the CTI as a predictive tool for stroke risk among patients with hypertension utilizing data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). This study provides a new perspective and evidence-based strategies for preventive care and therapeutic management of stroke.

Methods

Study population

The CHARLS database is an extensive research project designed to collect information on the social, economic, and health aspects of the Chinese population aged 45 and older. CHARLS employs multi-stage probability sampling to construct a representative longitudinal survey, and its data covers 150 districts throughout 28 provinces in China. The scope of the study encompasses various domains, including demographic information and blood tests, physical exams and health assessments. Beginning with its baseline survey in 2011, CHARLS has consistently conducted biannual follow-up surveys, resulting in five nationwide cycles of baseline and follow-up research [24].

A total of 11,847 individuals who provided blood information in the CHARLS database 2011 baseline survey were chosen as potential study participants of whom, 1,405 were excluded due to missing data, including fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), and CRP. In addition, 6,312 participants who were not diagnosed with hypertension or had missing information on the hypertension questionnaire, and 260 with a history of stroke or incomplete stroke information were excluded. Thirty-six aged < 45 years at baseline were also excluded. Finally, the cohort consisted of 3,834 hypertensive patients aged 45 or older at baseline without a stroke history, with complete data for CTI calculation. Follow-up data for stroke incidence were collected during visits in 2013, 2015, and 2018 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study population screening flowchart

Calculation of CTI

CTI was defined as 0.412* Ln (CRP [mg/L]) + Ln (TC [mg/dl] × FBG [mg/dl])/2 [20].

Hypertension and stroke diagnosis

Blood pressure measurements were conducted three times by a medical professional using a sphygmomanometer with subjects instructed to remain relaxed and quiet throughout the procedure. For data analysis, the mean values of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were calculated based on the three measurements obtained. Hypertension was defined as any of the following: SBP ≥ 140mmHg or DBP ≤ 90mmHg; participants who answered ‘yes’ to the following question in the household questionnaire: ‘Have you been diagnosed with hypertension by a doctor?’, ‘Do you know that you have hypertension?’ and ‘Are you now taking any treatments to treat hypertension?’.

The study outcome event was a stroke. Stroke was defined based on subjects who answered ‘yes’ to the following questions in the household questionnaire: ‘Have you been diagnosed with stroke by a doctor?’ and ‘Are you now taking any treatments to treat stroke?’ and the person who filled in the time of stroke diagnosis.

The date of stroke onset was defined as the “time of last stroke diagnosis” in the questionnaire or the date of follow-up for the reported stroke occurrence. The gap from the date of stroke onset to the baseline was used to calculate the time to stroke. Participants who did not report suffering a stroke during the follow-up period were identified based on the time between the date of the last examination and baseline [25].

Potential impact factor

Various potential predictors that may influence hypertensive stroke were selected, including demographic variables: gender (male, female), age, Hukou (agricultural, urban, other), education level (illiterate, junior high school and below, above junior high school), marital status (married, divorced, other). Health status: dyslipidemia, diabetes, heart disease, reduced blood lipid, cardiology treatment, hypertension treatment, diabetes treatment, smoking status (never, former, current), and drinking status (never, moderate, vigorous). Laboratory data: body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2)), SBP, DBP, CRP, TG, FBG, urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Scr), TC, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), glycosylated hemoglobin (HBA1C), hemoglobin (HGB), and uric acid (UA). Dyslipidemia was defined as TC ≥ 200 mg/dL, TG ≥ 200 mg/dL, LDL ≥ 130 mg/dL, or HDL ≤ 40 mg/dL, or diagnosed by a physician as dyslipidemia or receiving lipid-lowering therapy. Diabetes was defined as FBG ≥ 6 mmol/L, physician diagnosis of diabetes, or receiving hypoglycemic therapy.

Multicollinearity was detected before screening the covariates, and variables with a variance inflation factor (VIF) < 5 were included in the analysis (Table S1). The stepAIC (Akaike Information Criterion, AIC) was utilized for feature selection to assess the model’s quality of fit by computing the AIC value for each latent factor and selecting the model with the minimum AIC value for further investigation.

Missing data processing

Missing data included a history of heart disease (11, 0.29%), smoking status (2, 0.05%), drinking status (2, 0.05%), BMI (140, 3.65%), SBP (418, 10.90%), DBP (418, 10.90%), Scr (2, 0.05%), HBA1C (28, 0.73%), and HGB (23, 0.60%). To mitigate the impacts of missing values on data analysis and modeling, a random forest imputation method was applied to ensure data completeness and correctness.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using R version 4.2.1 and SPSS 27.0.1. Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using t-tests. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages and compared using the Pearson chi-squared test.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were utilized to determine the cumulative hazard of stroke based on the CTI quartile. The association between CTI and stroke incidence in hypertensive patients was studied using multivariate Cox regression analysis. The stepAIC algorithm was applied for variable selection, and four models were built: the unadjusted model; Model I: selected based on demographic variables and adjusted for age and educational level; Model II: selected from demographic variables and health status and adjusted for Huko, gender, heart disease, and hypertension treatment. Model III: selected from all predictors and adjusted for gender, heart disease, hypertension treatment, SBP, LDL, and UA. Subsequently, restricted cubic splines (RCS) curves were generated using the aforementioned models to test whether there is a nonlinear association between CTI and stroke risk in hypertensive patients. Subgroup analyses stratified by gender, age (45–60 years, ≥ 60 years), Hukou (agricultural, non-agricultural), education level (illiterate, non-illiterate), marital status (married, other), dyslipidemia, diabetes, and heart disease populations were performed to investigate the prediction of CTI in the different groups and potential interactions. Meanwhile, sensitivity analyses were performed to verify outcome stability, eliminating subjects with missing data. Subjects who died between 2011 and 2018 were also excluded in the reanalysis.

Boruta algorithm

The Boruta algorithm is a feature selection strategy based on the random forest framework that iteratively compares the significance (Z-value) of original features with their artificial counterparts (“shadow features”) generated by random forest. If the Z-value of the original features is significantly higher than the maximum Z-value of the shadow features at each step of the iteration, the feature is deemed important; otherwise, it is considered unimportant or tentative [26]. The selection of important characteristics for model refinement is thought to improve model accuracy and stability. The Boruta algorithm was utilized to determine essential variables and evaluate the role of CTI in predicting the risk of stroke in the hypertensive population.

Predictive models based on machine learning

Three machine learning-based predictive models were utilized to estimate the risk of stroke in hypertensive patients. The dataset was divided into two mutually exclusive subsets in a 7:3 ratio: the training and testing sets. Random Survival Forest (RSF) [27], Support Vector Machine (SVM) [28], and Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) [29] survival models were employed to predict stroke risk. Furthermore, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed via the prediction results, and the area under the curve (AUC) was determined to assess the predictive performance of each model.

Results

Participants baseline characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort are stratified by stroke (Table 1). A total of 3,834 hypertensive patients were enrolled, including 1,727 males (45%) and 2,107 females (55%), with an overall average age of 62 ± 10 years. The median CTI was 8.87. After a seven-year follow-up, 368 participants (9.6%) experienced a stroke. Compared with non-stroke individuals, stroke patients had significantly higher levels of CTI, BMI, TyG, CRP, TG, FBG, TC, LDL, and HGB and lower HDL levels (P < 0.05). Participants with a history of dyslipidemia, diabetes, or heart disease and those taking therapies for dyslipidemia, heart disease, or hypertension were more likely to have a stroke (P < 0.05). When stratified by CTI quartile, stroke incidence rates were 19.6% for the first quartile (Q1), 23.4% for the second (Q2), 25.3% for the third (Q3), and 31.8% for the fourth (Q4), with a notable increase in stroke incidence as CTI levels rose (P = 0.004). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were also stratified according to CTI quartile groupings (Table S2) .

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population based on stroke

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 3,834) | Non-stroke (N = 3,466) | Stroke (N = 368) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 62 ± 10 | 62 ± 10 | 62 ± 9 | 0.629 |

| CTI, median (IQR) | 8.87 (8.34, 9.48) | 8.86 (8.32, 9.45) | 8.99 (8.51, 9.60) | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg, mean ± SD | 148.03 ± 19.31 | 147.89 ± 19.16 | 149.35 ± 20.70 | 0.197 |

| DBP, mmHg, mean ± SD | 83.31 ± 11.51 | 83.26 ± 11.48 | 83.85 ± 11.78 | 0.355 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 24.30 (21.72, 26.97) | 24.22 (21.69, 26.94) | 24.82 (22.15, 27.31) | 0.030 |

| CRP, mg/L, median (IQR) | 1.23 (0.65, 2.61) | 1.22 (0.65, 2.58) | 1.42 (0.70, 2.80) | 0.025 |

| TG, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 115.93 (81.42, 169.04) | 115.05 (81.42, 167.26) | 125.23 (86.07, 188.50) | 0.013 |

| FBG, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 114.34 ± 41.05 | 113.86 ± 40.78 | 118.93 ± 43.31 | 0.032 |

| TyG, median (IQR) | 8.73 (8.34, 9.17) | 8.73 (8.33, 9.16) | 8.79 (8.41, 9.31) | 0.005 |

| BUN, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 15.85 ± 4.69 | 15.84 ± 4.68 | 16.01 ± 4.80 | 0.517 |

| Scr, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 0.80 ± 0.28 | 0.80 ± 0.28 | 0.82 ± 0.20 | 0.184 |

| TC, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 198.03 ± 39.78 | 197.60 ± 39.84 | 202.08 ± 39.99 | 0.037 |

| HDL, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 49.74 ± 15.17 | 49.92 ± 15.31 | 48.10 ± 13.70 | 0.017 |

| LDL, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 119.12 ± 36.83 | 118.71 ± 36.96 | 122.92 ± 35.32 | 0.031 |

| HBA1C, %, median (IQR) | 5.20 (4.90, 5.50) | 5.20 (4.90, 5.50) | 5.20 (4.93, 5.60) | 0.026 |

| HGB, g/dL, median (IQR) | 14.40 (13.20, 15.70) | 14.40 (13.20, 15.70) | 14.70 (13.40, 15.80) | 0.011 |

| UA, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 4.64 ± 1.32 | 4.64 ± 1.32 | 4.65 ± 1.31 | 0.948 |

| Huko, N (%) | 0.604 | |||

| Agriculture | 3,016 (78.7%) | 2,721 (78.5%) | 295 (80.2%) | |

| Urban | 795 (20.7%) | 725 (20.9%) | 70 (19.0%) | |

| Other | 23 (0.6%) | 20 (0.6%) | 3 (0.8%) | |

| Gender, N (%) | 0.145 | |||

| Male | 1,727 (45.0%) | 1,548 (44.7%) | 179 (48.6%) | |

| Female | 2,107 (55.0%) | 1,918 (55.3%) | 189 (51.4%) | |

| Educational level, N (%) | 0.155 | |||

| Illiteracy | 1,232 (32.1%) | 1,130 (32.6%) | 102 (27.7%) | |

| Junior high school and below | 2,216 (57.8%) | 1,991 (57.4%) | 225 (61.1%) | |

| Above junior high school | 386 (10.1%) | 345 (10.0%) | 41 (11.1%) | |

| Marital status, N (%) | 0.706 | |||

| Married | 3,235 (84.4%) | 2,922 (84.3%) | 313 (85.1%) | |

| Other | 599 (15.6%) | 544 (15.7%) | 55 (14.9%) | |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 0.019 | |||

| No | 1,219 (31.8%) | 1,122 (32.4%) | 97 (26.4%) | |

| Yes | 2,615 (68.2%) | 2,344 (67.6%) | 271 (73.6%) | |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 0.003 | |||

| No | 3,053 (79.6%) | 2,782 (80.3%) | 271 (73.6%) | |

| Yes | 781 (20.4%) | 684 (19.7%) | 97 (26.4%) | |

| Heart disease, N (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 3,157 (82.3%) | 2,879 (83.1%) | 278 (75.5%) | |

| Yes | 677 (17.7%) | 587 (16.9%) | 90 (24.5%) | |

| Reduce blood lipid, N (%) | 0.003 | |||

| No | 3,476 (90.7%) | 3,158 (91.1%) | 318 (86.4%) | |

| Yes | 358 (9.3%) | 308 (8.9%) | 50 (13.6%) | |

| Cardiology treatment, N (%) | 0.009 | |||

| No | 3,352 (87.4%) | 3,046 (87.9%) | 306 (83.2%) | |

| Yes | 482 (12.6%) | 420 (12.1%) | 62 (16.8%) | |

| Hypertension treatment, N (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 1,908 (49.8%) | 1,763 (50.9%) | 145 (39.4%) | |

| Yes | 1,926 (50.2%) | 1,703 (49.1%) | 223 (60.6%) | |

| Diabetes treatment, N (%) | 0.051 | |||

| No | 3,582 (93.4%) | 3,247 (93.7%) | 335 (91.0%) | |

| Yes | 252 (6.6%) | 219 (6.3%) | 33 (9.0%) | |

| Smoking status, N (%) | 0.164 | |||

| Never | 2,389 (62.3%) | 2,172 (62.7%) | 217 (59.0%) | |

| Former | 352 (9.2%) | 309 (8.9%) | 43 (11.7%) | |

| Current | 1,093 (28.5%) | 985 (28.4%) | 108 (29.3%) | |

| Drinking status, N (%) | 0.132 | |||

| Never | 2,258 (58.9%) | 2,054 (59.3%) | 204 (55.4%) | |

| Moderate | 392 (10.2%) | 344 (9.9%) | 48 (13.0%) | |

| Vigorous | 1,184 (30.9%) | 1,068 (30.8%) | 116 (31.5%) | |

| CTI quartile, N (%) | 0.004 | |||

| Q1(6.85 ≤ CTI < 8.34) | 962 (25.1%) | 890 (25.7%) | 72 (19.6%) | |

| Q2(8.34 ≤ CTI < 8.87) | 948 (24.7%) | 862 (24.9%) | 86 (23.4%) | |

| Q3(8.87 ≤ CTI < 9.48) | 973 (25.4%) | 880 (25.4%) | 93 (25.3%) | |

| Q4(9.48 ≤ CTI ≤ 13.16) | 951 (24.8%) | 834 (24.1%) | 117 (31.8%) | |

Continuous variables are expressed as Mean ± SD or Median (IQR), categorical variables are expressed as number (percent)

Abbreviation CTI: C-reactive protein-triglyceride-glucose index; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; BMI: body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; TG: total cholesterol; FBG: fast blood glucose; TyG: triglyceride-glucose; BUN: urea nitrogen; Scr: serum creatinine; TC: total cholesterol; HDL: high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HBA1C, glycated hemoglobin; HGB: hemoglobin; UA: uric acid

Associations between CTI and stroke in the hypertensive population

According to the Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis (Figure S1), the cumulative risk of stroke increased considerably as CTI rose (Log-rank P = 0.003). Four Cox regression models revealed a positive association between CTI and stroke risk (Table 2). Using the stepAIC approach for covariate selection, the fully adjusted model revealed a 21% increase in stroke risk for each additional unit of CTI (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.08–1.37). Subsequently, after converting CTI into quartile variables, the unadjusted model showed that participants in Q4 had a 70% higher risk of stroke than those in Q1 (HR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.26–2.26, P < 0.001). This strong trend remained in the fully adjusted model, with participants in the highest CTI quartile having a 66% higher risk of stroke than those in the lowest quartile (HR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.23–2.25, P = 0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariate COX regression of the relationship between CTI and stroke in hypertensive population

| Variable | Unadjusted model | Model 1† | Model 2‡ | Model 3§ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value | |

| CTI | 1.21(1.08–1.35) | < 0.001 | 1.21(1.08–1.35) | < 0.001 | 1.19(1.06–1.33) | 0.003 | 1.21(1.08–1.37) | 0.001 |

| CTI (quartile) | ||||||||

| Q1(6.85 ≤ CTI < 8.34) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Q2(8.34 ≤ CTI < 8.87) | 1.21(0.88–1.64) | 0.226 | 1.20(0.88–1.64) | 0.258 | 1.21(0.88–1.65) | 0.241 | 1.19(0.87–1.63) | 0.278 |

| Q3(8.87 ≤ CTI < 9.48) | 1.28(0.94-1,74) | 0.111 | 1.28(0.94–1.47) | 0.121 | 1.26(0.93–1.72) | 0.143 | 1.25(0.91–1.71) | 0.170 |

| Q4(9.48 ≤ CTI ≤ 13.16) | 1.70(1.26–2.26) | < 0.001 | 1.69(1.26–2.26) | < 0.001 | 1.63(1.21–2.19) | 0.001 | 1.66(1.23–2.25) | 0.001 |

| P for trend | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.008 | ||||

†Adjust for: age and educational level

‡Adjusted for: Huko, gender, heart disease, and hypertension treatment

§Adjust for: gender, heart disease, hypertension treatment, SBP, LDL, and UA

Abbreviation HR: hazard ratios; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; CTI: C-reactive protein-triglyceride-glucose index; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; LDL: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; UA: uric acid

RCS curves were drawn to investigate the trends between CTI and stroke risk (Fig. 2). All four models demonstrated a linear association between CTI and stroke risk. The P for nonlinear terms was 0.164 in the fully adjusted model, whereas the P-value for the overall models was 0.003.

Fig. 2.

Restricted cubic spline of relationship between CTI and stroke events in hypertensive population. Curves represents the hazard ratios, and the audiovisual section represents the 95% confidence interval. (A) Unadjusted model. (B) Adjust for: age and educational level. (C) Adjusted for: Huko, gender, heart disease, and hypertension treatment. (D) Adjust for: gender, heart disease, hypertension treatment, SBP, LDL, and UA

Subgroup analysis

Subsequently, we examined possible variations in the relationship between CTI, a continuous variable, and stroke risk within different subgroups (Fig. 3). Subgroup analysis of gender, age, Hukou, education level, marital status, diabetes, and heart disease revealed a positive correlation between CTI and the risk of stroke in hypertensive patients. Intriguingly, a significant interaction effect was only observed in the dyslipidemia subgroup (P-value for interaction = 0.002).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis for the association between CTI and stroke incidence in hypertensive population. Adjust for: gender, heart disease, hypertension treatment, SBP, LDL, and UA

Boruta algorithm

The results of the evaluation of variables related to stroke risk in hypertensive patients via the Boruta feature selection algorithm are depicted in Fig. 4. The screened important variables were heart disease, CTI, HDL, and SBP. Cox regression analysis was further performed on the key variables identified by the Boruta algorithm. The results revealed a positive association between CTI (continuous variable) and stroke risk (HR = 1.18, 95% CI 1.03–1.34, P = 0.015) (Table S2).

Fig. 4.

Evaluating the importance of variables based on Boruta algorithm. Green for important variables, yellow for tentative ones and red for unimportant ones

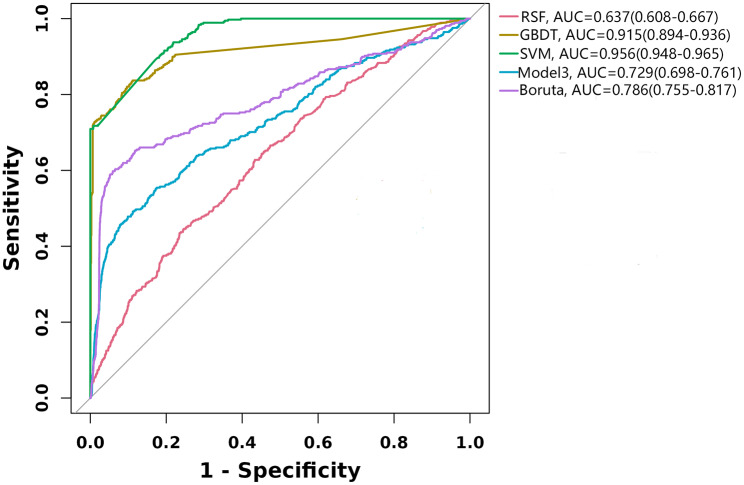

Predictive modeling

Three prediction models were constructed utilizing machine learning methods. Additionally, the capacity of CTI to predict stroke risk was evaluated using model 3 and Boruta algorithm-adjusted models, respectively. ROC curves were plotted based on the five predictions (Fig. 5). The SVM survival model performed extremely well in predicting stroke risk, with an AUC of 0.956 (95% CI = 0.948–0.965), followed by the GBDT survival model (AUC = 0.915, 95% CI = 0.894–0.936) and Boruta’s algorithm model (AUC = 0.786, 95% CI = 0.755–0.817).

Fig. 5.

ROC curves. RSF: Random Survival Forest model; SVM: Support vector machine survival model; GBDT: Gradient boosting decision tree survival model; Boruta algorithm adjust for: Heart disease, HDL, SBP; Model 3 adjust for: gender, heart disease, hypertension treatment, SBP, LDL, and UA

Sensitivity analysis

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to substantiate the reliability of the results. Initially, to ensure data accuracy, it was found that CTI (continuous and categorical quartiles) was positively correlated with stroke risk after the exclusion of 461 individuals with incomplete data. The fully adjusted model revealed the Q4 group was 71% more likely to have a stroke than the Q1 group (HR = 1.71, 95% CI = 1.24–2.37) (Table S4). Furthermore, after excluding the 94 participants who died between 2011 and 2018, the results were consistent with the main analysis (Table S5).

Discussion

The current prospective cohort study identified CTI as a novel composite indicator of inflammation and IR levels that predicts the risk of stroke in hypertensive patients. Additionally, our data revealed a linear association between CTI and stroke outcomes, indicating that higher CTI values are correlated with a higher stroke risk. The introduction of the Boruta algorithm for feature selection confirmed the significant effect of CTI on stroke risk prediction in hypertensive individuals. The model adjusted with variables selected by the Boruta algorithm further validated the role of CTI as a predictor of stroke risk. Multiple prediction models, constructed by machine learning algorithms, demonstrated effectiveness in predicting stroke risk. This study provides an innovative perspective on the evaluation of stroke risk in individuals with hypertension.

Association between TyG and stroke

CTI, created by Ruan and colleagues, is a tool for the prognostic assessment of cancer patients [20]. It combines an inflammatory biomarker CRP with the IR index TyG. Previous research has demonstrated a significant association between the TyG index and inflammatory markers with stroke risk. A series of cohort studies conducted in various types of populations, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [30], the Kailuan cohort [31], the CHARLS [11], and the Rural Chinese Cohort Study [32], have also reported the connection between TyG levels and risk for stroke. A meta-analysis of data from 18 studies confirmed TyG as a prognostic marker for ischemic stroke [33]. The TyG index is a reliable predictor of stroke risk in the general population and certain populations, including non-diabetics [34], hypertensives [18], and liver transplant recipients [35].

Association between CRP and stroke

Inflammation plays a crucial role in the formation, development, and burst of atherosclerotic plaques, all of which critically influence stroke incidence [5, 36]. The non-specific inflammatory marker CRP was linked to an increased risk of ischemic stroke in healthy men [37]. A previous study found that the risk of ischemic stroke increased significantly among individuals with elevated CRP levels in the highest quartile in the aged population (over 65 years) (HR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.23–2.08) [38]. A systematic meta-analysis of over 160,000 participants reported a log-linear association between CRP levels and stroke risk, with a 27% increase in risk for every threefold increase in CRP levels (risk ratio (RR) = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.15–1.40) [16]. Elevated CRP levels also predict an increased risk of recurrent strokes, with a 14% risk increase for each standard deviation elevation in CRP levels (HR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.06–1.22) [39]. Numerous studies have highlighted the prognostic significance of CRP for stroke risk, which may be attributable to its activation of inflammatory cascades, vascular dysfunction, thrombotic promotion, and plaque instability, all of which contribute to stroke risk. However, further research is needed to clarify this complex system.

Potential mechanisms underlying CTI prediction of stroke in hypertensive patients

Considering that IR and inflammation have been identified as independent risk factors for stroke, and hypertension is known to cause arterial endothelial dysfunction, increase the expression of inflammatory mediators and adhesion molecules, and accelerate atherosclerotic plaque formation [40], the impact of inflammatory variables should be considered when evaluating stroke risk in hypertensive individuals. We hypothesized that CTI, which combines IR and an inflammatory marker (CRP), may predict stroke risk among hypertensive patients. Previous research has demonstrated that inflammation mediates the relationship between IR and cardiovascular outcomes. For example, Cui et al. reported that CRP significantly mediated the association between TyG and cardiovascular events [41]. Furthermore, the role of CRP in the predictive potential of TyG for cardiovascular events in diabetic individuals with chronic coronary syndrome has been validated [42]. These studies highlight the complex relationship between TyG, inflammation, and cardiovascular outcomes. Our findings further support the association between stroke risk and the combined CRP-TyG index, with the linear association between CTI and stroke emphasizing the importance of carefully monitoring CRP and TyG levels in hypertensive patients. Regular physical exercise, dietary changes, weight control, and prudent pharmacological therapies to reduce IR and inflammation may all assist in reducing stroke risk. The present study provides a new perspective for predicting stroke outcomes. Furthermore, based on previous studies, we hypothesized that the combined assessment of inflammation and IR may have predictive value for cardiovascular events. Further research into the combined impact of CRP and TyG on cardiovascular disease is warranted in the future.

While our study has pointed to the potential utility of a combined assessment of IR and CRP in predicting stroke risk in hypertensive patients, the specific mechanism remains unknown. IR and inflammation may both trigger endothelial dysfunction, thereby compromising arterial integrity, accelerating atherosclerosis progression, and increasing the risk of stroke [43, 44]. Moreover, inflammation can exacerbate IR, since IR represents a persistent low-grade inflammatory state capable of releasing inflammatory mediators from tissues, thereby intensifying the inflammatory response throughout the body. These factors interact to create a vicious cycle that ultimately leads to an aggravation of vascular occlusion and plaque instability [45].

Limitations

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the study sample was restricted to a Chinese population aged ≥ 45 years, necessitating further research that includes different cohorts from various regions and age groups to further validate the predictive effectiveness of CTI. Secondly, this study focused on the hypertensive cohort rather than stroke risk assessment in the overall population. Thirdly, the CHARLS database is based on self-reporting for stroke diagnosis and does not distinguish between stroke types. Thus, further details regarding stroke types are required to ascertain the potential predictive value of CTI for different forms of stroke. Fourthly, we did not fully adjust all confounding variables due to the lack of comprehensive, detailed medication histories in CHARLS, which may influence CRP and TyG measures. Fifthly, the exclusion of 461 participants due to missing data may have introduced a greater degree of error. Although we attempted to address the missing values through data interpolation, this approach still resulted in a certain degree of error. Furthermore, the lack of tracking of changes in IR and inflammation over time made it unable to determine the association between CTI trajectory and stroke risk. Lastly, given that this was an observational study, causality between the risk of stroke and CTI was not established.

Conclusion

In summary, the present utilized the CHARLS database and a novel composite indicator of IR and inflammation, termed CTI, to predict the risk of stroke in a hypertensive population. The findings revealed a significant association between a higher CTI level and an increased risk of stroke, suggesting that CTI may serve as a predictive biomarker for stroke in hypertensive patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1. Multicollinearity detection. Table S2. Characteristics of the study population based on CTI quartiles. Table S3. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the relationship between CTI and stroke based on boruata algorithm. Table S4. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the relationship between CTI and stroke in uninterpolated data. Table S5. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the relationship between CTI and stroke excluded exit data. Figure S1. Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative stroke prevalence risk in hypertensive patients

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the participants in the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) and the staff responsible for the related programs.

Abbreviations

- CTI

C-reactive protein-triglyceride-glucose index

- TyG

Triglyceride-glucose

- BMI

Body mass index

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- TG

Total cholesterol

- FBG

Fast blood glucose

- BUN

Urea nitrogen

- Scr

Serum creatinine

- TC

Total cholesterol

- HDL

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HBA1C

Glycated hemoglobin

- HGB

Hemoglobin

- UA

Uric acid

- HR

Hazard ratios

- 95%CI

95% confidence interval

- RSF

Random survival forest

- SVM

Support vector machine

- GBDT

Gradient boosting decision tree

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

Author contributions

S. T: conducted research, data calculation and article writing. H. W: conceptualization, supervision and editing. K. L and Y. Q: analyzed data. Q. Z. and JM: data collection. X. C had primary responsibility for final content, designed research and review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Chengdu Third People’s Hospital independent research project [No. CSY-YN-01-2023-017], Chengdu medical research project [No. 202313052863] and Southwest Jiaotong University medical and industrial training project [No. 2682024ZTPY001].

Data availability

Data for this study were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/), and specific analyzed data are available through the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The CHARLS survey was approved by Peking University’s Biomedical Ethics Committee, and all participants signed informed consent forms.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Songyuan Tang and Han Wang are co-first authors and contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.GBD 2021 Stroke Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024;23:973–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feigin VL, Owolabi MO, World Stroke Organization–Lancet Neurology Commission Stroke Collaboration Group. Pragmatic solutions to reduce the global burden of stroke: a World Stroke Organization-Lancet Neurology Commission. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:1160–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J-G, Zhou R-R, Cai G-J. From hypertension to stroke: mechanisms and potential prevention strategies. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:577–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill MA, Yang Y, Zhang L, Sun Z, Jia G, Parrish AR, et al. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. 2021;119:154766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spagnoli LG, Mauriello A, Sangiorgi G, Fratoni S, Bonanno E, Schwartz RS, et al. Extracranial thrombotically active carotid plaque as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2004;292:1845–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas I, Tall A, Accili D. The impact of macrophage insulin resistance on advanced atherosclerotic plaque progression. Circ Res. 2010;106:58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maida CD, Daidone M, Pacinella G, Norrito RL, Pinto A, Tuttolomondo A. Diabetes and ischemic stroke: An Old and New Relationship an overview of the Close Interaction between these diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simental-Mendía LE, Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Q, Lin Y, Xu R, Luo F, Chen R, Li P, et al. Positive association of triglyceride-glucose index with new-onset hypertension among adults: a national cohort study in China. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu Y-W, Chang C-C, Chou R-H, Tsai Y-L, Liu L-K, Chen L-K, et al. Gender difference in the association between TyG index and subclinical atherosclerosis: results from the I-Lan Longitudinal Aging Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Yang Y, Zhang J, Liu S, Zhuang W. The change of triglyceride-glucose index may predict incidence of stroke in the general population over 45 years old. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui C, Qi Y, Song J, Shang X, Han T, Han N, et al. Comparison of triglyceride glucose index and modified triglyceride glucose indices in prediction of cardiovascular diseases in middle aged and older Chinese adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C, Liang D. The association between the triglyceride-glucose index and the risk of cardiovascular disease in US population aged ≤ 65 years with prediabetes or diabetes: a population-based study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaturvedi S, De Marchis GM. Inflammatory biomarkers and stroke subtype: an important New Frontier. Neurology. 2024;102:e208098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzoulaki I, Murray GD, Lee AJ, Rumley A, Lowe GDO, Fowkes FGR. Relative value of inflammatory, hemostatic, and rheological factors for incident myocardial infarction and stroke: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Circulation. 2007;115:2119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, Pepys MB, Thompson SG, et al. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:132–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCabe JJ, Walsh C, Gorey S, Harris K, Hervella P, Iglesias-Rey R, et al. C-Reactive protein, Interleukin-6, and vascular recurrence after stroke: an Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Stroke. 2023;54:1289–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang N, Chi X, Zhou Z, Song Y, Li S, Xu J, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index is associated with a higher risk of stroke in a hypertensive population. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Z, Ding X, Yue Q, Wang X, Chen Z, Cai Z, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index trajectory and stroke incidence in patients with hypertension: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruan G-T, Xie H-L, Zhang H-Y, Liu C-A, Ge Y-Z, Zhang Q, et al. A novel inflammation and insulin resistance related Indicator to predict the survival of patients with Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:905266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruan G-T, Deng L, Xie H-L, Shi J-Y, Liu X-Y, Zheng X, et al. Systemic inflammation and insulin resistance-related indicator predicts poor outcome in patients with cancer cachexia. Cancer Metab. 2024;12:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao D-F. Value of C-Reactive protein-triglyceride glucose index in Predicting Cancer Mortality in the General Population: results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr Cancer. 2023;75:1934–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mei Y, Li Y, Zhang B, Xu R, Feng X. Association between the C-reactive protein-triglyceride glucose index and erectile dysfunction in US males: results from NHANES 2001–2004. Int J Impot Res. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li F, Wang Y, Shi B, Sun S, Wang S, Pang S, et al. Association between the cumulative average triglyceride glucose-body mass index and cardiovascular disease incidence among the middle-aged and older population: a prospective nationwide cohort study in China. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tao S, Yu L, Li J, Xie Z, Huang L, Yang D, et al. Prognostic value of triglyceride-glucose index in patients with chronic coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao B, Nguyen VK, Xu M, Colacino JA, Jolliet O. Random survival forest for predicting the combined effects of multiple physiological risk factors on all-cause mortality. Sci Rep. 2024;14:15566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen QT, Tran MP, Prabhakaran V, Liu A, Nguyen GH. Compact machine learning model for the accurate prediction of first 24-hour survival of mechanically ventilated patients. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1398565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu Z, Hu Y, Zhang S, Dong L, Chen X, Yang H et al. Machine-learning-based models assist the prediction of pulmonary embolism in autoimmune diseases: a retrospective, multicenter study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Jiang Y, Shen J, Chen P, Cai J, Zhao Y, Liang J et al. Association of triglyceride glucose index with stroke: from two large cohort studies and mendelian randomization analysis. Int J Surg. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang A, Wang G, Liu Q, Zuo Y, Chen S, Tao B, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index and the risk of stroke and its subtypes in the general population: an 11-year follow-up. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y, Sun H, Zhang W, Xi Y, Shi X, Yang Y, et al. Elevated triglyceride-glucose index predicts risk of incident ischaemic stroke: the rural Chinese cohort study. Diabetes Metab. 2021;47:101246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Huang X, Wang Y, Leng L, Xu J, Feng L, et al. The impact of triglyceride-glucose index on ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou H, Ding X, Lan Y, Fang W, Yuan X, Tian Y, et al. Dual-trajectory of TyG levels and lifestyle scores and their associations with ischemic stroke in a non-diabetic population: a cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding Z, Ge M, Tan Y, Chen C, Hei Z. The triglyceride-glucose index: a novel predictor of stroke and all-cause mortality in liver transplantation recipients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, Yiin GS, Geraghty OC, Schulz UG, Kuker W, Mehta Z, et al. Incidence, outcome, risk factors, and long-term prognosis of cryptogenic transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: a population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:903–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:973–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao JJ, Thach C, Manolio TA, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Chaves PHM, et al. C-reactive protein, carotid intima-media thickness, and incidence of ischemic stroke in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2003;108:166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCabe JJ, O’Reilly E, Coveney S, Collins R, Healy L, McManus J, et al. Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and risk of recurrence after ischaemic stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Stroke J. 2021;6:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H-H, Cao Y-X, Sun D, Jin J-L, Zhang H-W, Guo Y-L, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and hypertension: combined effects on coronary severity and cardiovascular outcomes. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1783–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui C, Liu L, Qi Y, Han N, Xu H, Wang Z, et al. Joint association of TyG index and high sensitivity C-reactive protein with cardiovascular disease: a national cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li T, Wang P, Wang X, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Diabetic Chronic Coronary Syndrome patients. Nutrients. 2023;15:2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin A, Wang S, Li J, Wang M, Lin J, Li H, et al. Mediation of systemic inflammation on insulin resistance and prognosis of nondiabetic patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2023;54:759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang T, Li G, Wang C, Xu G, Li Q, Yang Y, et al. Insulin resistance and coronary inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Püschel GP, Klauder J, Henkel J, Macrophages L-G, Inflammation. Insulin Resistance and hyperinsulinemia: a mutual ambiguous relationship in the development of metabolic diseases. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1. Multicollinearity detection. Table S2. Characteristics of the study population based on CTI quartiles. Table S3. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the relationship between CTI and stroke based on boruata algorithm. Table S4. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the relationship between CTI and stroke in uninterpolated data. Table S5. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the relationship between CTI and stroke excluded exit data. Figure S1. Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative stroke prevalence risk in hypertensive patients

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/), and specific analyzed data are available through the corresponding author.