Abstract

Background

Pulmonary hemorrhage (PH) in respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in extremely preterm infants exhibits a high mortality rate and poor long-term outcomes. The aim of the present study was to develop a machine learning (ML) predictive model for RDS with PH in extremely preterm infants.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of extremely preterm infants with RDS at the Children’s Hospital of Soochow University between January 2015 and January 2021. We applied three ML algorithms—logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)—to evaluate the performance of each model using the area under the curve (AUC), and developed a predictive model based on the optimal model. We calculated SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values to determine variables importance and show visualization results, and constructed a nomogram for individualized prediction.

Results

A total of 309 patients with RDS were enrolled, including 48 (15.5%) with PH. A total of 29 variables were collected, including demographic and clinical characteristics, laboratory data, and image classification. According to the AUC values, the RF model performed best (AUC = 0.868). Based on the SHAP values, the top five important variables in the RF model were gestational age, PaO2/FiO2, birth weight, mean platelet volume, and Apgar score at 5 min.

Conclusions

Our study showed that the RF model could be used to predict the risk of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants. The nomogram provides clinicians with an effective tool for early warning and timely management.

Keywords: Premature, Respiratory distress syndrome, Pulmonary hemorrhage, Machine learning

Introduction

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is one of the most common respiratory diseases among preterm neonates. It is mainly caused by immature lung development and lack of pulmonary surfactant (PS). RDS often causes shortness of breath, progressive dyspnea, and respiratory failure several hours after birth. With the continuous development of PS replacement therapy and neonatal respiratory support technology, the survival rate of infants with RDS has been increasing in recent years. However, severe RDS can still cause a series of early complications. Pulmonary hemorrhage (PH) is a major complication in premature infants with RDS, and RDS combined with PH may lead to a higher mortality rate and worse clinical outcomes [1, 2].

PH exhibits a high mortality rate, ranging from 50 to 82%, and survivors show an increased risk of chronic lung disease and poor long-term outcomes [3–5]. There are numerous factors that contribute to the development of PH, including gestational age (GA), birth weight (BW), perinatal asphyxia, RDS, infection, persistent ductus arteriosus, and the need for PS therapy [6–8]. Premature delivery and RDS are the two most important risk factors for PH. Previous studies have shown that PH is an independent risk factor for death in newborns with GA < 32 weeks and an independent predictor of poor prognosis in preterm infants with RDS [9, 10]. Thus, proactive prevention of PH is very important. In the context, understanding high-risk factors and establishing predictive models for early intervention are the key to preventing PH.

While machine learning (ML) has widely implemented in disease diagnosis, complication monitoring, and clinical prediction [11, 12], investigators have not focused on identifying the risk factors for PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants. In the present study, we adopted machine-learning (ML) to develop a model that would enable us to predict the risk factors for PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants.

Materials & methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective study consisted of 354 neonates (GA < 32 weeks) with RDS who were hospitalized at the Children’s Hospital of Soochow University between January 2015 and January 2021. The exclusion criteria were follows: (a) present of congenital malformations; (b) incomplete records; and (c) treatment abandoned or death occurred in the first 24 h of life. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Soochow University (no. 2015010512), with a waiver for informed consent because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Data collection

The collected variables (equivalent to features in computer science) included the general conditions of the neonate (GA, BW, sex, Apgar score at 1 min, Apgar score at 5 min, small for GA [SGA], neonatal asphyxia, intubation in the delivery room, need for invasive ventilation on the first day, PS use, patent ductus arteriosus [PDA], early-onset septicemia [EOS], image classification); laboratory data (PaO2/FiO2, platelet [PLT] count, mean platelet volume [MPV], prothrombin time [PT], activated partial thromboplastin time [APTT]) and the general condition of the mother (maternal age, mode of delivery, multiple-pregnancy status, amniotic fluid contamination, umbilical cord abnormality, placental abnormality, premature rupture of membranes [PROM], pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, prenatal infection, and antenatal steroids). These data were obtained before the occurrence of PH and then used to analyze the risk factors for PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants.

Definitions

RDS was diagnosed in neonates who showed clinical symptoms of respiratory distress that were associated with signs of hyaline membrane disease upon chest radiographic examination. Positive clinical signs of RDS included grunting, cyanosis, nasal flaring tachypnea, intercostal retractions, hypoventilation, hypoxemia, and respiratory acidosis [13]. PH was defined as bright red blood exuding from the endotracheal tube, which was associated with clinical deterioration, and new ground-glass opacities or signs of white lung in the entire lung fields on chest radiogram [14]. The diagnosis of neonatal asphyxia was based on the following: Apgar score ≤ 7 at 1 or 5 min after birth, effective spontaneous breathing not established, and umbilical arterial blood pH ≤ 7.15, and other reasons for a low Apgar score were excluded [15]. Umbilical cord abnormality was assessed as being either too long (> 70 cm) or too short (< 30 cm) or exhibiting signs of edema, torsion, or a knot (among other abnormalities). Placental abnormalities included placental abruption, placenta previa, or an abnormal placental shape, size, or weight. EOS was defined as the presence of infectious diseases within 72 h after birth, as confirmed by blood culture [16].

Model development and assessment

We applied three ML algorithms—logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)—to predict the risk factors for PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants. All models were developed in Python (version 3.9.12), with the LR and RF models implemented using the Sklearn package and the XGBoost model using the Xgboost package. Four-fold cross-validation was used and the dataset was randomly divided into four equal parts. In each iteration, three parts served as the training set, and one part served as the test set. This process was repeated four times, with each part serving as the test set once. The results from these iterations were averaged to provide a final evaluation of the performance of the model. The models were evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and their associated area under the curve (AUC). We used SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to select the top 10 features with the most significant influence on the predictions. Finally, we constructed a nomogram using the top five predictors from the best model to assess clinical utility.

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into a PH group and a non-PH group, and the variables were compared between the two groups. The independent-sample t test was employed to analyze continuous variables that followed a normal distribution, while the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for variables showing a non-normal distribution. The chi-square (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact-probability test was performed for categorical variables. We conducted all statistical analyses using Python (version 3.9.12) and R software (4.2.1), and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

General characteristics

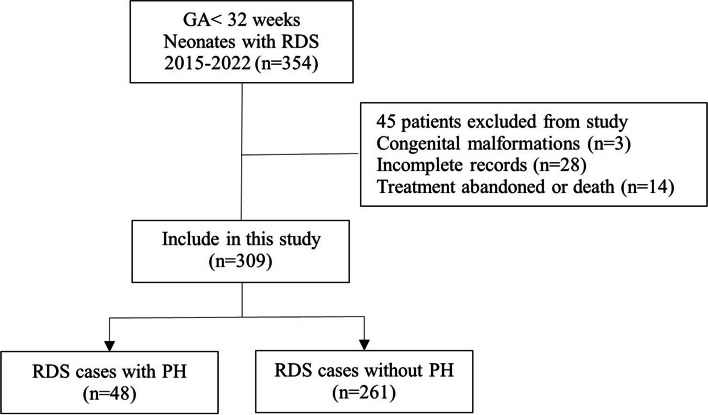

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 309 patients were ultimately included in our study cohort, and the incidence of PH with RDS in extremely preterm infants was 15.5% (48/309). The cohort was divided into the PH group (n = 48) and the non-PH group (n = 261). Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics, laboratory data, and image classification of the included patients. With univariate analyses, significant differences between the two groups were found in GA, BW, Apgar score at 1 min, Apgar score at 5 min, neonatal asphyxia, intubation in delivery room, invasive ventilation on the first day, PS use, PDA, image classification, PaO2/FiO2, PLT, MPV, PT, and pregnancy-induced hypertension (P < 0.05), and we developed ML models based on these variables.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study. GA gestational age, RDS respiratory distress syndrome, PH Pulmonary hemorrhage

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of PH and non-PH group in RDS in extremely preterm infants

| Variables | PH (n = 48) M (P25, P75)/N (%) |

Non-PH (n = 261) M (P25, P75)/N (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal factors | |||

| GA (weeks) | 28 (27, 30) | 30 (29, 31) | 0.016 |

| BW (g) | 1126 (920,1365) | 1370 (1145, 1600) | 0.037 |

| Gender | 0.545 | ||

| Male | 21 (43.8) | 102 (39.1) | |

| Female | 27 (56.2) | 159 (60.9) | |

| Apgar scores at 1 min | 6 (4, 8) | 7 (6, 9) | 0.001 |

| Apgar scores at 5 min | 7 (6, 9) | 8 (8, 10) | 0.003 |

| SGA | 2 (4.2) | 9 (3.4) | 0.806 |

| Neonatal asphyxia | 16 (33.3) | 43 (17.2) | 0.001 |

| Intubation in delivery room | 29 (60.4) | 84 (32.2) | 0.001 |

| Invasive ventilation on the first d | 36 (75.0) | 98 (37.5) | 0.001 |

| Surfactant use | 45 (93.8) | 212 (81.2) | 0.004 |

| PDA | 21 (43.8) | 66 (25.3) | 0.041 |

| Early-onset septicemia | 7 (14.6) | 32 (12.3) | 0.65 |

| Image classification | 3 (2, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.001 |

| Laboratory Data | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 | 268 (215, 332) | 333 (231, 418) | 0.001 |

| PLT | 204 (173, 204) | 232 (185, 277) | 0.015 |

| MPV | 11 (10, 11) | 10 (9, 10) | 0.005 |

| PT | 19 (16, 20) | 18 (16, 19) | 0.016 |

| APTT | 69 (52, 78) | 68 (57, 75) | 0.789 |

| Maternal factors | |||

| Age (years) | 29 (26, 35) | 30 (26, 32) | 0.805 |

| Cesarean section | 21 (43.8) | 124 (47.5) | 0.453 |

| Multiple pregnancy | 25 (52.1) | 94 (36.1) | 0.633 |

| Amniotic fluid contamination | 6 (12.5) | 41 (15.7) | 0.571 |

| Umbilical cord abnormality | 5 (10.4) | 25 (9.6) | 0.858 |

| Placenta abnormality | 8 (16.7) | 48 (18.4) | 0.777 |

| PROM | 9 (18.8) | 55 (21.1) | 0.453 |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | 4 (8.3) | 16 (6.1) | 0.036 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 3 (6.3) | 14 (5.4) | 0.508 |

| Prenatal infection | 3 (6.3) | 11 (4.2) | 0.212 |

| Antenatal steroids | 18 (37.5) | 129 (49.4) | 0.348 |

PH Pulmonary hemorrhage, RDS Respiratory distress syndrome, GA Gestational age, BW Birth weight, SGA Small for gestational age, PDA Patent ductus arteriosus, PLT Platelet, MPV Mean platelet volume, PT Prothrombin time, APTT Activated partial thromboplatin time, PROM Premature rupture of membranes

Predictive model and nomogram

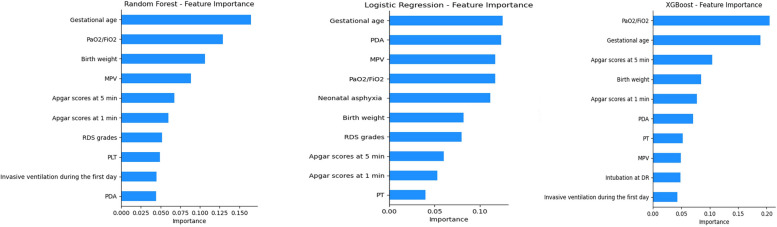

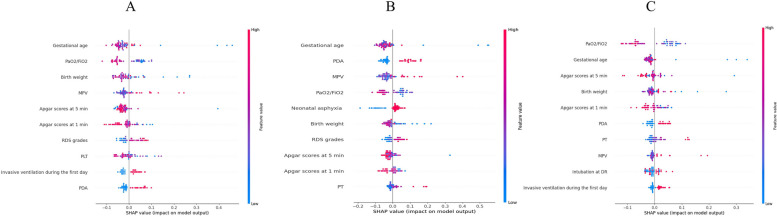

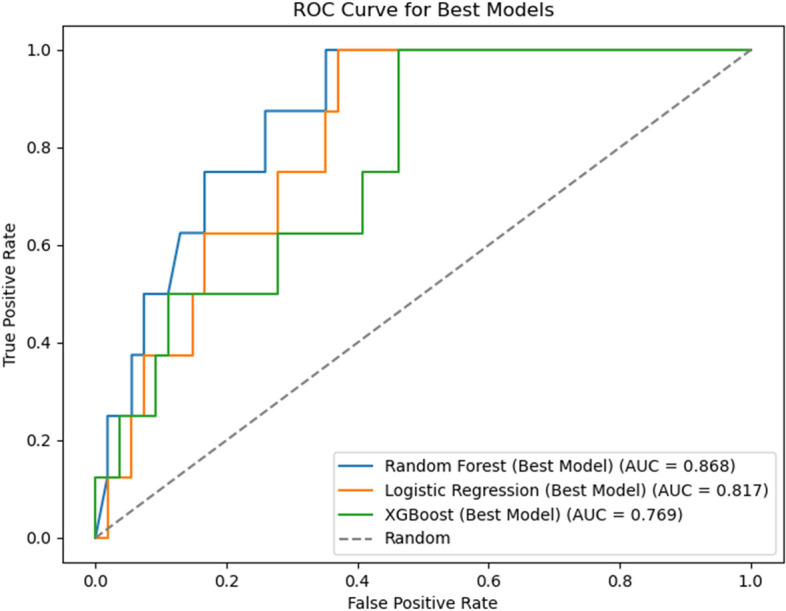

Our results indicated that the RF model (AUC = 0.868) outperformed the LR (AUC = 0.817) and XGBoost (AUC = 0.769) models (Fig. 2). The results of the sensitivity and specificity analyses of these models are summarized in Table 2. Figure 3 shows the features importance analysis for the different models to illustrate the importance of the features intuitively. For each model, we screened out the top 10 features and found that GA was the most important feature in all three models. GA, PaO2/FiO2, BW, MPV, and Apgar score at 5 min were the top five features in the RF model. We also obtained other, more complex correlations with PH and analyzed them to show the positive and negative effects (Fig. 4). Figure 4 shows which features are the most important and their range of influence in the dataset. The y-axis in the figure represents a feature, and the x-axis indicates the SHAP value. For each feature, a point represents an observation [i.e., a neonate]. The position of the point on the X-axis indicates the effect of the feature on the model output for that particular patient. When multiple points land at the same x position, they pile up to show a denser area. A positive SHAP value indicates a positive effect on the predicted value, while a negative SHAP value indicates a negative effect on the predicted value. The color represents the size of the feature value, where red indicates higher feature value, and blue indicates lower feature value: for instance, higher PaO2/FiO2 values (red dots) are on the negative side of the vertical line of SHAP values, indicating that high PaO2/FiO2 values decrease the likelihood of PH, and the opposite is true for lower (blue dots) values. Features such as GA, PaO2/FiO2, BW, and Apgar score at 5 min were negatively correlated with PH, while MPV was positively correlated with PH.

Fig. 2.

Area under the curve (AUC) for all three machine learning models. random forest (RF) model, AUC = 0.868; logistic regression (LR) model, AUC = 0.817; extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model, AUC = 0.769

Table 2.

Performance of each predictive model

| RF | LR | XGBoost | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.887 | 0.839 | 0.822 |

| Sensitivity | 0.805 | 0.779 | 0.753 |

| Specificity | 0.718 | 0.753 | 0.741 |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.868 (0.815–0.917) | 0.817 (0.756–0.872) | 0.769 (0.687–0.834) |

RF Random forest, LR Logistic regression, XGBoost Extreme gradient boosting, AUC Area under the curve, CI Confidence interval

Fig. 3.

Importance of the features for each model based on SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). MPV mean platelet volume, RDS respiratory distress syndrome, PLT platelet, PDA patent ductus arteriosus, PT prothrombin time, DR delivery room

Fig. 4.

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) for interpreting the features in each machine learning model. A random forest (RF) model; B logistic regression (LR) model; C extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model. MPV mean platelet volume, RDS respiratory distress syndrome, PLT platelet, PDA patent ductus arteriosus, PT prothrombin time, DR delivery room

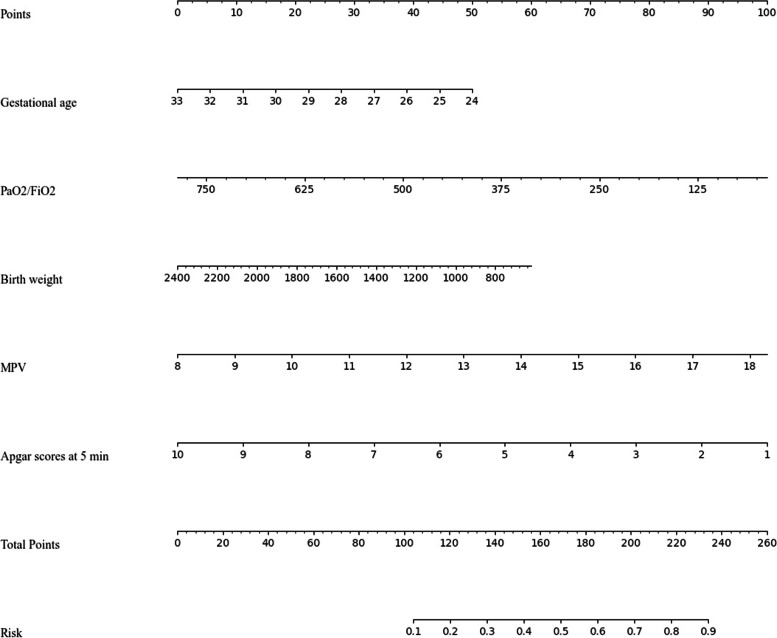

To visualize of the best-performing model (RF model), we generated a nomogram that integrated the top five features from RF model for estimating the risk of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants (Fig. 5). In the nomogram, the value of each feature was scored on a point scale from 0 to 100, with the total score being the sum of all individual feature scores. The sum was then located on the total points axis and a line was drawn from the total score axis straight down to the risk axis to estimate the risk factors of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants (See Fig. 5 for a worked example).

Fig. 5.

Nomogram based on the RF model to estimate the risk of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants. The nomogram illustrated that each variable corresponding to a specific score ranging from 0 to 100. The total score is added by all variables and presented on the ‘Total Points’ axis. The morbidity of PH corresponds to the bottom ‘Risk’ axis, which illustrates the higher score, the higher risk of developing PH. For instance: a baby of 24 weeks [score 50] with a weight of 1400 g [score 34], PaO2/FiO2 of 250 [score 72], MPV of 10 [score 19], and Apgar score at 5 min = 9 [score 11], will have a risk of 0.62 (the total score = 186)

Discussion

Our study was the first-ever attempt to develop ML models to predict PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants. ML has previously been applied to different disease models to predict risk factors or prognosis. In the current study, we used three methods, namely the LR, RF, and XGBoost models, to establish the prediction models. The RF model achieved the best predictive performance and had the highest AUC value. The RF model revealed that GA, PaO2/FiO2, BW, MPV, and Apgar score at 5 min were the top five risk factors for PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants.

GA was the most important feature in our model. PH is one of the primary causes of premature death in the early postnatal period, and a lower GA in premature infants is associated with a higher incidence of RDS and PH. A large multicenter retrospective study showed that the incidence of PH ranged from 2.0 to 8.7% in preterm infants with a GA of 24–32 weeks [17]. Ferreira et al. [7] analyzed 67 newborns with PH, and showed that 77.6% of the newborns with PH had GA less than 29 weeks—a clear indication that PH is associated with prematurity. Researchers have also highlighted the observation that lower GA is the strongest risk factor for the development of PH [7, 18], which is consistent with our study. We also found a negative correlation between BW and PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants. Therefore, lower GA and BW in premature infants are associated with a higher incidence of PH. Previous studies have shown that the incidence of PH in preterm infants with low BW is elevated; the incidence of PH in very-low-birth-weight infants is 4–12%, while the incidence in extremely-low-birth-weight infants is as high as 11–18.8% [7, 16, 19].

Another important feature revealed in the present study was PaO2/FiO2. There have been few reports describing PaO2/FiO2 as a risk factor for PH, but we acknowledge that PaO2/FiO2 constitutes an important diagnostic criterion for neonatal lung injury and its severity. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio can be obtained through bedside blood gas analysis, which is simple and feasible, and it can thus be used for the early prediction of PH. Fan et al. [20], for example, reported that an PaO2/FiO2 less than 100 was an independent risk factor for neonatal PH. A large number of experiments have revealed that injuries to the pulmonary capillary endothelial cells and alveolar epithelial structure are characteristic pathological changes in acute lung injury. Fernández et al. [21] demonstrated that the presence of acute lung injury was an initial feature of PH and noted the importance of a prompt diagnosis of the underlying disease, and an experiment in rats showed that neonatal PH was a specific manifestation of acute lung injury or acute RDS during the neonatal period [22].

The platelet activation products that are available in circulation play a very important role in the pathogenesis of vascular and inflammatory diseases. MPV is one of the factors that define thrombocyte functions [23]. MPV is negatively associated with PLT, i.e., the platelet volume increases in patients with reduced PLT. Decreased PLT can increase the tendency to bleed, which may lead to serious complications, such as intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and PH. It has previously been reported that MPV can be used as an adjunct in the progression of RDS, IVH, necrotizing enterocolitis, and sepsis in premature infants [24, 25]. In a study by Go et al., there was a relationship between high MPV at birth and the unfavorable outcomes of preterm newborns [26]. It seems that elevated MPV promotes inflammatory response and oxidative lung injury in neonates. Similarly, we found that MPV constituted an important predictive factor for PH and was positively associated with PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants.

The Apgar score is internationally recognized as one of the most convenient and acceptable methods for assessing neonatal asphyxia. Our research implied that Apgar score at 5 min and Apgar scores at 1 min were important factors for predicting the risk of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants, and they were negatively correlated with PH. The lower the Apgar score, the higher the risk of PH. This means that newborns may be in more depressed states and require stronger resuscitation, or even ventilator support, which is likely to drive excessive expansion of the alveoli, causing pressure damage to the alveolar capillaries and promoting the development of PH. According to Yum et al. [5], a low Apgar score at 5 min elevates the incidence of massive PH and affects the survival of infants with massive PH. Moreover, other features such as RDS image classification, invasive ventilation on the first day, and PDA were also screened out in the RF model, indicating that these features might be useful in assessing the risk of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants. The severity of RDS is related to pulmonary hemorrhage. Cao et al. [27] found that PH was significantly increased in RDS with grade III -IV. PDA causes shunting from left-to-right, which in turn leads to high flow and high-pressure damage to the vascular bed, increasing the risk of PH in preterm infants [3, 8, 28]. A single-center study found invasive ventilation during the first day was associated with the occurrence of PH, and the incidence of PH in premature infants with invasive ventilation on the first day were increased [16]. These results suggest that the prediction models are feasible for predicting the risk of PH, and the nomogram can provide the sum of the scores to pediatricians for estimating the risk of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants, which could then be used in early preventive therapies.

Limitations

There were some limitations to this study. First, this was a single-center retrospective study, and this might have introduced selection bias. More importantly, the models were not validated using independent samples, so the performance of the models may not be generalizable. Thus, multicenter prospective studies with larger clinical cohorts are needed in the future to refine this prediction model.

Conclusion

In this study, we exploited ML to establish three predictive models (an LR model, RF model, and XGBoost model) to screen the risk factors for PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants, and we determined that the RF model showed the best predictive performance. The nomogram constructed by the top five variables screened by the RF model can intuitively predict the risk of PH in RDS in extremely preterm infants, which is helpful to provide clinical basis for early prevention and individualized treatment.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- RDS

Respiratory distress syndrome

- ML

Machine learning

- LR

Logistic regression

- RF

Random forest

- XGBoost

Extreme gradient boosting

- SHAP

SHapley Additive exPlanations

- PS

Pulmonary surfactant

- GA

Gestational age

- BW

Birth weight

- SGA

Small for gestational age

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

- EOS

Early-onset septicemia

- PLT

Platelet

- MPV

Mean platelet volume

- PT

Prothrombin time

- APTT

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- PROM

Premature rupture of membranes

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

Authors’ contributions

Wan-liang Guo and Yu-qi Liu Study conception and design. Yu-qi Liu, Yue Tao and Shi-jin Zhong Data acquisition. Yue Tao, Tian-na Cai, Yang Yang and Hui-min Mao Analysis and data interpretation. Yu-qi Liu, Yue Tao Writing - original draft. Wan-liang Guo and Yu-qi Liu Writing - review & editing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

N/A.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Soochow University (no. 2015010512), which waived the informed consent requirement because of the retrospective nature of the study and minimal risk to participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee M, Wu K, Yu A, et al. Pulmonary hemorrhage in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: Radiographic evolution, course, complications and long-term clinical outcomes. J Neonatal Perinat Med. 2019;12(2):161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towers HM, Wung JT. Rationing ventilatory support for the newborn with respiratory distress. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25(8):638–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad KA, Bennett MM, Ahmad SF, Clark RH, Tolia VN. Morbidity and mortality with early pulmonary haemorrhage in preterm neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(1):F63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholl JE, Yanowitz TD. Pulmonary hemorrhage in very low birth weight infants: a case-control analysis. J Pediatr. 2015;166(4):1083–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yum SK, Moon CJ, Youn YA, Lee HS, Kim SY, Sung IK. Risk factor profile of massive pulmonary haemorrhage in neonates: the impact on survival studied in a tertiary care centre. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(2):338–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadžić D, Zulić E, Salkanović-Delibegović S, Softić D, Kovačević, Softić D. Short-term outcome of massive pulmonary hemorrhage in preterm infants in Tuzla Canton. Acta Clin Croat. 2021;60(1):82–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira CH, Carmona F, Martinez FE. Prevalence, risk factors and outcomes associated with pulmonary hemorrhage in newborns. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90(3):316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Xia H, Ye L, Li XX, Zhang ZQ. Exploring prediction model and survival strategies for pulmonary hemorrhage in premature infants: a single-center, retrospective study. Transl Pediatr. 2021;10(5):1324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Castro MP, Rugolo LM, Margotto PR. Survival and morbidity of premature babies with less than 32 weeks of gestation in the central region of Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2012;34(5):235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu YY, Jiang QN, Liu XX. Risk factors for pulmonary hemorrhage in low birth weight infants. Int J Pediatr. 2023;50:61–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Calster B, Wynants L. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1347–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Zhu Y, Zhao W, Wang Z, Pan H, et al. Machine learning algorithm to predict the in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2023;45(1):2212790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogg MF, Drorbaugh JE. Respiratory distress in the newborn infant. Am J Nurs. 2015;56:1559–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Zhao LL, Xu JJ, Yu YH, Li ZL, et al. Association between pulmonary hemorrhage and CPAP failure in very preterm infants. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:938431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen ZL, Jing L. Experts’ consensus on the criteria for the diagnosis and grading of neonatal asphyxia in China. Transl Pediatr. 2013;2(2):64–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang TT, Zhou M, Hu XF, Liu JQ. Perinatal risk factors for pulmonary hemorrhage in extremely low-birth-weight infants. World J Pediatr. 2020;16(3):299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad KA, Bennett MM, Ahmad SF, Clark RH, Tolia, VNl. Morbidity and mortality with early pulmonary haemorrhage in preterm neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(1):F63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suryawanshi P, Nagpal R, Meshram V, Malshe N, Kalrao V. Pulmonary Hemorrhage (PH) in extremely low Birth Weight (ELBW) infants: successful treatment with surfactant. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(3):SD03–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen D, Wang M, Wang X, Ding XW, Ba RH, Mao J. High-risk factors and clinical haracteristics of massive pulmonary hemorrhage in infants with extremely low birth weight. CJCP. 2017;19(1):54–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan J, Hei MY, Huang XL, Li XP. Risk factors for neonatal pulmonary hemorrhage in the neonatal intensive care unit of a municipal hospital. CJCP. 2017;19(3):346–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández Fabrellas E, Blanquer Olivas J, Blanquer Olivas R, Simó Mompó M, Chiner Vives E, Ruiz Montalt F. Acute lung injury as initial manifestation of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Med Interna. 1999;16(6):281–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han YK, Cai XX. Neonatal pulmonary hemorrhage and acute lung injury. J Appl Clin Pediatr. 2004;19:433–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korniluk A, Koper-Lenkiewicz OM, Kamińska J, Kemona H, Dymicka-Piekarska V. Mean Platelet Volume (MPV): New Perspectives for an Old Marker in the Course and Prognosis of Inflammatory Conditions. Mediators Inflamm. 2019; 2019:9213074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sadeghzadeh M, Khoshnevisasl P, Fallah R, Marzban A, Ghodrati D. The relationship between mean platelet volume (MPV) and intraventricular hemorrhage in very low birth weight infants. J Neonatal Perinat Med. 2023;16(4):681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yildiz A, Yigit A, Benli AR. The prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume in critically ill patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(8):2246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Go H, Ohto H, Nollet KE, Takano S, Kashiwabara N, Chishiki M, et al. Using platelet parameters to anticipate morbidity and mortality among preterm neonates: a retrospective study. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao ZL, Pan JJ, Chen XQ, WU Y, LU KY, YANG Y. Pulmonary hemorrhage in very low birth weight infants: risk factors and clinical. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2022;24(10):1117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kluckow M, Evans N. Ductal shunting, high pulmonary bloodflow, and pulmonary hemorrhage. J Pediatr. 2000;137(1):68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.