Abstract

Background

Oral diseases are a significant global public health challenge. Current evidence indicates that several chronic conditions are individually associated with tooth loss. People are living with more than one chronic condition, known as multimorbidity (MM). Considering the common risk factors for oral and chronic diseases, this study aimed to evaluate the association between MM and tooth loss in the Chilean population.

Methods

Cross-sectional study with secondary data from the latest Chilean National Health Survey (ENS 2016-17). The number of remaining teeth was classified into four groups: functional dentition (≥ 20 remaining teeth), moderate tooth loss (10 to 19), severe tooth loss (1 to 9), and edentulism (0). MM was defined based on the number of chronic conditions as a binary variable (MM≥ 2) and as a 4-level categorical variable (MMG0−G3), G0: none, G1: 1, G2: 2–4, and G3: ≥5 conditions. Stratified analysis by age group (< 65, ≥ 65 years) was performed. Mean and SD were calculated for crude and adjusted remaining teeth. Significance level was set to 0.05. Prevalence ratios were estimated with Poisson regression models with robust variance, crude and adjusted for sex, age, geographic area, and educational level. Logistic regressions models were fitted to calculate odds ratios as a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Of 4,151 adults aged 17–98, 54.9% had MM and the prevalence of moderate, severe tooth loss and edentulism was 25.4%, 6.9% and 4.8% respectively. Adults aged ≥ 65 years with MM≥ 2 were 1.66 [1.04–2.66] times more likely to have severe tooth loss than those without MM. Adults aged < 65 years with MMG3 were 1.76 [1.12–2.77] times more likely to have moderate tooth loss and 2.55 [1.02–6.36] times more likely to have severe tooth loss than those without MM.

Conclusions

In this study, we found statistically significant associations between the number of chronic conditions and moderate/severe tooth loss in both analyzed age groups. These findings highlight the need to provide oral health care for adults with multimorbidity using a person-centred model and to seek strategies to prioritize health care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-024-05184-8.

Keywords: Tooth loss, Multimorbidity, Oral health, Epidemiology

Background

Oral diseases such as dental caries, periodontal disease and oral cancer are a significant global challenge. Among them, tooth loss significantly affects people’s health, nutritional status, appearance, self-confidence, functionality, and quality of life [1–4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines functional dentition as the presence of more than 20 teeth in the mouth, which allows an adequate masticatory function. In Chile, the prevalence of functional dentition is estimated at 85.7% in the group between 35 and 44 years old, and 23.9% in the group between 65 and 74 years old [5].

Current evidence indicates that several chronic conditions are individually associated with tooth loss, including malnutrition [6], obesity [7], cardiovascular diseases [8], hypertension [9], diabetes mellitus (DM) [10] and cognitive impairment [11]. This is because oral diseases frequently have common risk factors with chronic diseases, including poor diet, sugar consumption, alcohol intake and smoking [2]. However, due to the changing epidemiological profile in the world, people are living with more than one chronic condition [12].

Multimorbidity (MM) is the presence of multiple chronic diseases in the same person [12]. It is also a significant global public health challenge [13]. Combining various chronic diseases with an aging population creates a negative feedback loop exacerbating both conditions [12], leading to reduced quality of life, elevated medical needs, increased medication intake, higher healthcare costs, and more significant mortality [14–16].

In Chile, a country with an advanced stage of population aging, it is projected that by 2050 the group aged 65 years and older will represent 25% of the Chilean population [17]. Around 70% of the population over 15 years of age lives with two or more chronic diseases simultaneously [18]. Therefore, in 2021, the “Estrategia de Cuidado Integral Centrado en las Personas” (ECICEP) was implemented [19]. This initiative is designed as a framework to overcome the fragmentation of the health system, with the objective of transforming it towards a more individual-centric approach.

There is limited evidence analyzing the association between MM and tooth loss, so this study aimed to evaluate the association between MM and tooth loss in the Chilean population, considering the common risk factors for oral and chronic diseases and the existing association established in the literature.

Methods

Study design

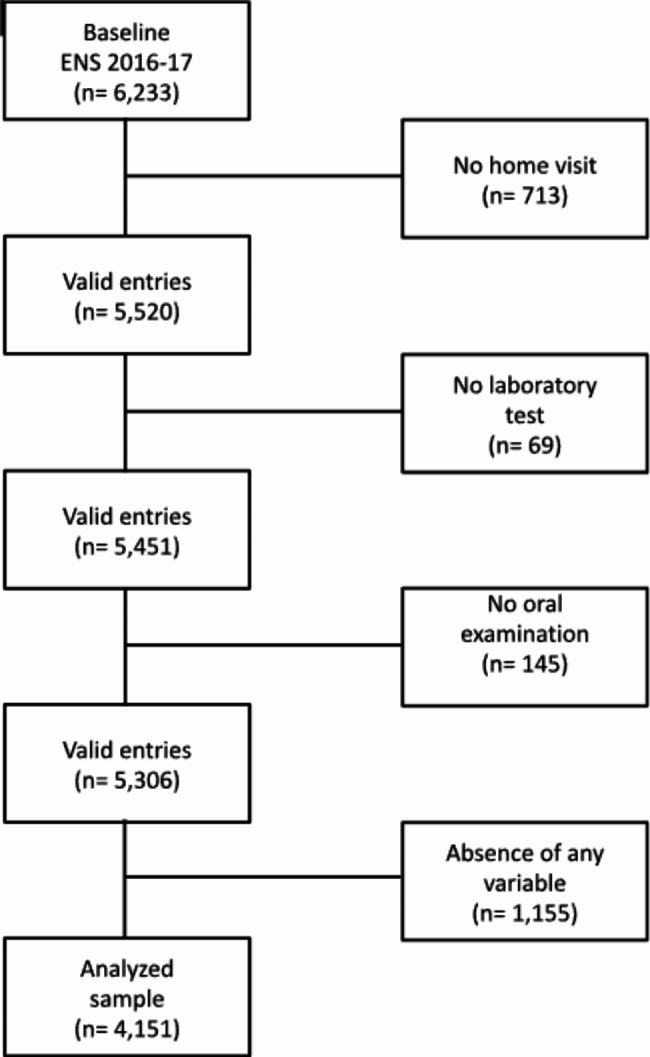

Cross-sectional study with secondary data from the latest Chilean National Health Survey (ENS 2016-17). The ENS 2016-17 is a national epidemiological surveillance tool focusing on non-communicable diseases, considering 72 health problems and their determinants. This tool targets Chilean adults aged 15 years and older, with a random, stratified, multistage, clustered sample of households representative of the national, regional, urban-rural level. The study had a final sample size of 6,233 participants who completed an interviewer-administered survey. Of these, 5,520 received a home visit from a nurse, 5,451 underwent laboratory examinations, and 5,306 underwent oral examinations. Participants aged 17 years or older were included in our study. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the participant´s inclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of participant’s inclusion

Tooth loss assessment

The number of remaining teeth was assessed by oral examination during ENS 2016-17. The examination was conducted during home visits by trained nurses using a dental mirror, dental explorer and standard operation lamp. The nurses were trained by nine dentists affiliated with the Ministry of Health of Chile (MINSAL). The training program included a theoretical presentation, a practical demonstration, an oral examination practice session, and a final test of 55 questions. The average score obtained was 49.95 ± 2.74, with an inter-examiner kappa coefficient of 0.85 (p-value < 0.01) [20].

This assessment was our dependent variable and teeth were classified as functional dentition if there were 20 or more remaining teeth, moderate tooth loss if there were between 10 and 19 remaining teeth, severe tooth loss if there were between 1 and 9 remaining teeth, and edentulism if there were no remaining teeth.

Multimorbidity assessment

This assessment corresponds to the 18 chronic systemic conditions proposed by the MINSAL in the ECICEP and assessed by self-report in the ENS 2016-17. These included: disability, chronic kidney disease (CKD), fibromyalgia, hypertension, thyroid disorders, myocardial infarction, DM, obesity, advanced CKD, glaucoma, cerebrovascular accident, osteoarthritis, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), smoking, asthma, liver disease, coagulation disorders. See supplementary material for operational definitions of each. We considered smoking to be a chronic condition because a significant percentage of smokers do it regularly, which can be considered tobacco dependence. Authors such as Bernstein [21], argue that smoking, mainly tobacco smoking, should be framed as a chronic condition, with periods of use and periods of abstinence.

MM in our study was our independent variable and it was defined as a binary variable (MM≥ 2) and as a 4-level categorical variable (MMG0−G3): MM≥ 2 corresponds to the coexistence of 2 or more chronic conditions and MMG0−G3, according to the ECICEP stratification criteria, where G3 corresponds to ≥ 5 chronic conditions, G2 to 2–4, G1 to 1, and G0 to have no chronic conditions.

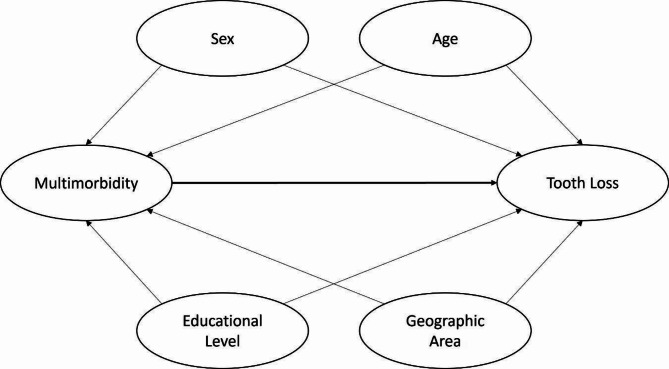

Covariates

The theoretical framework of the association between tooth loss and MM was structured using a directed acyclic graph (DAGitty version 3.0), as shown in Fig. 2. The following covariates were considered in the study: sex (male or female); age, divided into < 65 and ≥ 65 years, and secondarily into 17–24, 25–44, 45–64, 65–74, and > 74 years; geographic area, corresponding to the municipality where the patient lives (urban or rural); and educational level, representing the number of years completed and passed, divided into low (0–8 years), medium (8–12 years), and high (≥ 12 years).

Fig. 2.

Hypothesized association between of tooth loss and multimorbidity

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted on all variables, including the calculation of prevalence, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), mean, and SD. All analyses carried out were for surveys with complex sample design. Mean and SD were calculated for crude and adjusted remaining teeth. Prevalence and 95% CI were calculated for moderate tooth loss, severe tooth loss, and edentulism. Poisson regression models with robust variance, crude and adjusted for sex, age, geographic area, and educational level, were fitted to calculate the prevalence ratios (PRs) between MM and tooth loss. Stratified analysis by age group was performed. To ensure comparability with other studies, the age cut-off was set at ≥ 65 years. Sensitivity analysis was performed by calculating crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with logistic regressions for the association between MM and tooth loss. Significance level was set to 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.2.0) and RStudio (version 2023.06.1) with the packages survey, srvyr, and nnet.

Ethics

Data from the ENS 2016-17 are publicly available and anonymized. In any case, participants signed an informed consent form and the study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Los Andes (CEC-UC) (CEC2022135). The database used for the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the weighted sample. The study sample consisted of 4,151 individuals between 17 and 98 years, 50.6% were female. The mean age was 44.9 ± 17.3 years. 54.8% had a medium educational level (8–12 years), and 89.3% lived in an urban area. Concerning MM, 54.9% had two or more chronic diseases. The mean number of remaining teeth was 22.5 ± 8.6. The prevalence of moderate tooth loss was 25.4%, severe tooth loss was 6.9%, and edentulous was 4.8%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the weighted sample. Chilean National Health Survey 2016-17 (n = 4,151)

| Total | < 65years | ≥ 65 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Weighted population | Weighted population | Weighted population |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 50.6% | 49.9% | 54.8% |

| Male | 49.4% | 50.1% | 45.2% |

| Age | |||

| Mean ± SD | 44.9 ± 17.3 | 40.2 ± 13.6 | 73.9 ± 6.8 |

| Age Groups | |||

| 17–24 | 14.8% | 17.1% | - |

| 25–44 | 38.3% | 44.4% | - |

| 45–64 | 33.2% | 38.5% | - |

| 65–74 | 8.2% | - | 59.7% |

| > 75 | 5.5% | - | 40.3% |

| Educational Level | |||

| Low (< 8 years) | 16.9% | 10.4% | 57.5% |

| Medium (8–12 years) | 54.8% | 59.1% | 27.6% |

| High (> 12 years) | 28.3% | 30.5% | 14.9% |

| Geographic Area | |||

| Urban | 89.3% | 89.7% | 86.8% |

| Rural | 10.7% | 10.3% | 13.2% |

| Multimorbidity | |||

| No (≤ 1) | 45.1% | 49.4% | 17.6% |

| Yes (≥ 2) | 54.9% | 50.6% | 82.4% |

| Multimorbidity | |||

| G0 | 15.9% | 18.0% | 2.8% |

| G1 | 29.2% | 31.4% | 14.8% |

| G2 | 43.0% | 41.8% | 50.9% |

| G3 | 11.9% | 8.8% | 31.5% |

| Number of Remaining Teeth | |||

| Mean ± SD | 22.5 ± 8.6 | 24.3 ± 6.8 | 10.8 ± 9.2 |

| Tooth loss* | |||

| Moderate tooth loss | 25.4% | 17.3% | 76.1% |

| Severe tooth loss | 6.9% | 3.8% | 26.4% |

| Edentulism | 4.8% | 1.7% | 24.0% |

* These prevalences did not include subjects with functional dentition

Table 2 presents the prevalence of chronic diseases of the weighted sample. Obesity (35.9%), smoking (32.9%) and hypertension (30.7%) were the most prevalent chronic diseases. When the sample was stratified by age group, the highest prevalences were obesity (36.1%), smoking (36.0%) and osteoarthritis (26.4%) among those < 65 years, and hypertension (78.9%), obesity (35.2%) and osteoarthritis (34.3%) among ≥ 65 years.

Table 2.

Prevalence of morbidities of the weighted sample. Chilean National Health Survey 2016-17 (n = 4,151)

| Morbidity | Total | < 65 years | ≥ 65 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | 0.9% | 0.1% | 5.8% |

| CKD | 3.1% | 0.8% | 17.5% |

| Fibromyalgia | 5.3% | 4.9% | 8.2% |

| Hypertension | 30.7% | 23.0% | 78.9% |

| Thyroid Disorders | 6.8% | 5.7% | 13.3% |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.3% | 2.0% | 11.5% |

| DM | 11.8% | 9.1% | 29.0% |

| Obesity | 35.9% | 36.1% | 35.2% |

| Advanced CKD | 0.5% | 0.2% | 2.3% |

| Glaucoma | 3.3% | 1.0% | 5.6% |

|

Cerebrovascular Accident |

6.5% | 5.0% | 15.9% |

| Osteoarthritis | 27.5% | 26.4% | 34.3% |

| Depression | 16.5% | 17.7% | 8.7% |

| COPD | 1.8% | 1.0% | 7.3% |

| Smoking | 32.9% | 36.0% | 13.8% |

| Asthma | 5.3% | 4.9% | 7.6% |

| Liver Disease | 5.0% | 4.5% | 8.6% |

|

Coagulation Disorders |

2.1% | 1.4% | 6.9% |

Table 3 presents the mean number of remaining teeth in < 65 years compared with adults ≥ 65 years and in adults with MM≥ 2 and MMG2/G3 compared with those without MM. Adults aged < 65 with MM≥ 2 have a mean of 24.6 ± 0.3 remaining teeth (95% CI 24.0; 25.3). On the other hand, individuals aged ≥ 65 have a mean of 13.8 ± 0.9 (95% CI 12.1; 15.6). Adults aged < 65 in MMG3 have a mean of 22.9 ± 0.7 remaining teeth (95% CI 21.4; 24.4), with 2.1 teeth less than MMG0 individuals. Otherwise, individuals aged ≥ 65 in the G3 group have a mean of 13.6 ± 1.1 remaining teeth (95% CI 11.5; 15.8), 2.0 teeth less than individuals in the MMG0 group.

Table 3.

Weighted mean number of remaining teeth in Chilean population according to multimorbidity level. Chilean National Health Survey 2016-17 (n = 4,151)

| Total | < 65 years | ≥ 65 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimorbidity | Mean ± SD | (IC 95%) | Mean ± SD | (IC 95%) | Mean ± SD | (IC 95%) |

| No (≤ 1) | 22.6 ± 0.3 | [21.9; 23.3] | 24.9 ± 0.3 | [24.3; 25.5] | 13.8 ± 0.8 | [12.2; 15.4] |

| Yes (≥ 2) | 22.4 ± 0.3 | [21.8; 23.1] | 24.6 ± 0.3 | [24.0; 25.3] | 13.8 ± 0.9 | [12.1; 15.6] |

| G0 | 22.8 ± 0.4 | [22.0; 23.5] | 25.0 ± 0.4 | [24.3; 25.7] | 15.6 ± 1.7 | [12.4; 18.8] |

| G1 | 22.6 ± 0.4 | [21.8; 23.3] | 24.8 ± 0.4 | [24.1; 25.5] | 13.3 ± 0.9 | [11.5; 15.1] |

| G2 | 22.7 ± 0.3 | [22.1; 23.4] | 24.9 ± 0.3 | [24.3; 25.6] | 13.8 ± 0.9 | [12.0; 15.6] |

| G3 | 21.1 ± 0.6 | [20.0; 22.3] | 22.9 ± 0.7 | [21.4; 24.4] | 13.6 ± 1.1 | [11.5; 15.8] |

Table 4 shows the prevalence ratios (PRs) for adults aged < 65 years and ≥ 65 years with MM≥ 2 compared with those without MM. After adjusted by confounders, adults aged < 65 years showed no statistically significant association. Adults aged ≥ 65 years with MM≥ 2 had 1.66 times higher prevalence of severe tooth loss (95% CI 1.04; 2.66).

Table 4.

Prevalence ratios of tooth loss in Chilean population according to multimorbidity level. Chilean National Health Survey 2016-17 (n = 4,151)

| Category | Multimorbidity | < 65 years | ≥ 65 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR Crude [95% CI] |

PR Adjusteda [95% CI] |

PR Crude [95% CI] |

PR Adjusteda [95% CI] |

||

| Moderate tooth loss | No (≤ 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes (≥ 2) | 2.20 [1.67; 2.89] | 1.07 [0.84; 1.36] | 0.96 [0.86; 1.06] | 1.13 [0.94; 1.37] | |

| Severe tooth loss | No (≤ 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes (≥ 2) | 2.52 [1.47; 4.33] | 1.12 [0.67; 1.89] | 1.39 [0.89; 2.19] | 1.66 [1.04; 2.66]* | |

| Edentulism | No (≤ 1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes (≥ 2) | 2.50 [1.03; 6.05] | 0.92 [0.39; 2.20] | 0.85 [0.58; 1.26] | 1.26 [0.76; 2.08] | |

a. The model was adjusted for age, sex, educational level and geographic area. PR: prevalence ratio. 95% CI: confidence interval. * p-value < 0.05

Table 5 shows the PRs for adults aged < 65 years and ≥ 65 years with MMG1, MMG2 and MMG3 compared with those without (MMG0). After adjusted by confounders, individuals aged < 65 years with MMG3 had a 1.76 times higher prevalence of moderate tooth loss (95% CI 1.12; 2.77) and 2.55 times higher prevalence of severe tooth loss (95% CI 1.02; 6.36), compared to MMG0. Adults aged ≥ 65 years showed no statistically significant association. Results in terms of the ORs for Tables 4 and 5 were similar to those estimated with PRs (Table S1 and S2, respectively).

Table 5.

Prevalence ratios of tooth loss in Chilean population according to multimorbidity level (G0-G3). Chilean National Health Survey 2016-17 (n = 4,151)

| Category | Multimorbidity | < 65 years | ≥ 65years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR Crude [95% CI] |

PR Adjustedb [95% CI] |

PR Crude [95% CI] |

PR Adjustedb [95% CI] |

||

| Moderate tooth loss | G0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| G1 | 1.65 [0.99; 2.73] | 1.65 [1.09; 2.51]* | 0.95 [0.67; 1.33] | 1.17 [0.90; 1.53] | |

| G2 | 2.57 [1.63; 4.08] | 1.44 [0.98; 2.10] | 1.07 [0.83; 1.37] | 1.09 [0.85; 1.39] | |

| G3 | 5.62 [3.40; 9.30] | 1.76 [1.12; 2.77]* | 1.10 [0.85; 1.44] | 1.09 [0.84; 1.40] | |

| Severe tooth loss | G0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| G1 | 1.87 [0.71; 4.94] | 2.03 [0.82; 5.03] | 0.67 [0.27; 1.71] | 0.87 [0.34; 2.20] | |

| G2 | 2.90 [1.22; 6.91] | 1.59 [0.71; 3.54] | 1.32 [0.60; 2.93] | 1.37 [0.60; 3.10] | |

| G3 | 8.70 [3.49; 21.66] | 2.55 [1.02; 6.36]* | 1.02 [0.46; 2.26] | 1.03 [0.45; 2.34] | |

| Edentulism | G0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| G1 | 2.15 [0.61; 7.59] | 2.85 [0.81; 10.03] | 1.36 [0.48; 3.83] | 1.44 [0.61; 3.40] | |

| G2 | 4.05 [1.27; 12.94] | 2.10 [0.66; 6.67] | 1.41 [0.54; 3.67] | 1.09 [0.47; 2.49] | |

| G3 | 5.64 [1.81; 17.54] | 1.30 [0.41; 4.14] | 2.01 [0.79; 5.13] | 1.29 [0.56; 2.97] | |

b. The model was adjusted for age, sex, educational level and geographic area. PR: prevalence ratio. 95% CI: confidence interval. * p-value < 0.05

Discussion

In the present study, MM was associated with tooth loss. However, this association was statistically significant only for severe tooth loss in adults with MM aged ≥ 65 years (Table 4), and in adults aged < 65 years (Table 5) for moderate tooth loss if they had ≥ 5 (MMG3) or 1 (MMG1) chronic condition, and for severe tooth loss if they were from MMG3, compared with subjects without chronic conditions (MMG0).

First of all, it is important to understand the epidemiological context of the Chilean population, where life expectancy has increased and geographical distribution has changed [22, 23]. This has led to inequities in access to and use of oral health care, which is a major challenge for older Chileans. Adequate access to oral health care is essential, as it provides opportunities for health promotion, disease prevention, early diagnosis and treatment to prevent tooth loss [20]. It is also important to understand that tooth loss is a multifactorial process related to social factors, access to healthcare services, smoking, diet, and general state of health [24].

This is the first study to analyze this relationship in Chile. There is limited evidence analyzing the association between MM and tooth loss, but our findings are consistent with previous studies in other populations. Bomfim et al. analyzed data from the 2019 National Health Survey of Brazil, which included 88,531 individuals aged 18 years and older. MM was the main exposure, categorized into two groups, having 2 or 3 comorbidities, based on 13 self-reported chronic diseases: hypertension, DM, depression, back problems, mental problems, asthma, arthritis, cancer, heart problems, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and work-related musculoskeletal disorder. Tooth loss was the main outcome, and it was classified into functional dentition and severe tooth loss. They reported that Brazilian adults with MM have a higher chance of severe tooth loss and a lower chance of functional dentition [25]. Zhang et al. 2022 assessed the association between MM and tooth loss in U.S. adults. They performed a secondary data analysis using the US 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a national cross-sectional telephone survey studying health conditions and health behaviors, including 471,107 US adults. MM was a dichotomous variable that was defined as having at least two of eight self-reported chronic diseases: DM, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, cancer, COPD, kidney disease, and asthma. Tooth loss was grouped into four categories: zero tooth loss, 1 to 5 tooth loss, 6 or more tooth loss, and edentulous. They found that people with MM are more likely to be edentulous than those with 1 or no chronic disease [26].

We found that 54.9% of the Chilean population had MM. This prevalence is higher than those reported by Garin et al. for China (45.1%) and Ghana (48.3%), similar to India (57.9%), and lower than South Africa (63.4%) and Mexico (63.9%) [27]. When stratifying the population by age, 50.6% of adults aged < 65 and 82.4% of those aged ≥ 65 years had MM. These prevalences are higher than those found by Bomfim et al. in the Brazilian population, where 19.3% of adults aged < 60 years and 50.9% of those aged ≥ 60 years had 2 or more chronic diseases [25].

The mean number of remaining teeth for adults aged < 65 years was 24.3 ± 6.8, and for adults aged ≥ 65 years was 10.8 ± 9.2. In both groups, a higher mean number of remaining teeth was observed in individuals without MM compared to individuals with MM≥ 2 and MMG2/G3. No studies evaluating the association between MM and the mean number of remaining teeth were found to compare these results.

Among the biological plausibility to explain the association between MM and tooth loss, the main one is inflammation. Graves et al. propose that systemic diseases modify the host response to oral bacteria, leading to increased inflammation than under healthy conditions [28]. This effect has been explored in the interactions of DM with periodontal disease, where pro-inflammatory mediators lead to tissue inflammation and modification of the immune response, increasing the susceptibility of oral tissues to destruction [29]. Rheumatoid arthritis also modifies the oral microbiota, increasing the levels of cytokines in the periodontium and saliva, leading to increased periodontal destruction [26]. A second possible mechanism is linked to the effects of the medications consumed by individuals with MM. Ucuncu et al. mention that the utilization of inhaled medicines such as corticosteroids and ß-mimetics by individuals with asthma and COPD modify the oral environment, making it drier, more cariogenic and leading to tooth loss [30].

This study has strengths and limitations that should be recognized. First, the limitations are that the ENS 2016-17 is a cross-sectional study, which cannot determine the directionality of the association between MM and tooth loss. The evidence supports hypothesizing the bidirectionality between MM and tooth loss, but it should be investigated with cohort and longitudinal studies. Second, some of the chronic diseases that compose the MM variable are self-reported, so they are susceptible to bias at the time of the study or cognitive status. And finally, the presence of residual confounding due to unmeasured or unidentified confounding variables.

Despite those above, it is possible to mention the following as strengths. First, it is highlighted that the ENS 2016-17 was used, representing the distribution of diseases and their determinants in the Chilean population [31]. Second, tooth loss was the outcome measure, a complex indicator that reflects the accumulation of oral diseases during life, influenced by biological, social and cultural factors [32, 33]. Finally, even though there are different definitions of MM, two definitions were used, one widely accepted with a cut-off in two or more conditions [34], and one aligned with the objectives of MINSAL’s ECICEP, with population divided into four categories: High Risk, with ≥ 5 chronic conditions (G3); Moderate Risk, with 2 to 4 chronic conditions (G2); Mild Risk, with 1 chronic condition (G1); and No Risk, with no chronic conditions (G0).

ECICEP is the new way of organizing Chile’s health care and population care. Generates a classification of risk in different strata, which allows health teams to program their interventions for each group, improving the management of chronic conditions in the population [19]. In this context, in November 2023, MINSAL approved the first program for periodontal treatment for people with DM between 35 and 54 years of age based on the fact that incorporating periodontal treatments in patients with MM can contribute to reducing the levels of glycosylated hemoglobin in adults with DM [35]. The inclusion of a definition of MM aligned with the ECICEP allows these findings to be used for future public policies in Chile, as the already mentioned periodontal treatment program.

Conclusion

In this study, we found statistically significant associations between the number of chronic conditions and moderate/severe tooth loss in both analyzed age groups. These findings highlight the need to develop new strategies that consider the burden of multimorbidity and the common risk factors between systemic and oral chronic diseases in order to prioritize health care for those at higher risk, thereby improving the oral and systemic health of the population through a person-centred model and universal health care. And never forget primary prevention in order to maintain health.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank to the MINSAL and ENS 2016-17’s participants. Also, Alvaro Passi for the data analysis contribution.

Abbreviations

- ENS 2016-17

Chilean National Health Survey 2016-17

- ECICEP

Estrategia de Cuidado Integral Centrado en las Personas

- MINSAL

Ministry of Health of Chile

Author contributions

M.S. and D.O. designed the study. M.S. and D.O. collected the data. M.S. was responsible for the statistical analysis and for drafting the manuscript. D.O., P.G. and P.M. edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

FAI Universidad de los Andes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Population Survey repository of the Department of Epidemiology of the Ministry of Health of the Government of Chile, http://epi.minsal.cl/encuestas-poblacionales/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was nested in the ENS 2016-17, whose protocols and written informed consent were approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (CEC-MedUC, Project number 16–019). Also, out study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Los Andes (CEC-UC) (CEC2022135).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adegboye ARA, Twetman S, Christensen LB, Heitmann BL. Intake of dairy calcium and tooth loss among adult Danish men and women. Nutrition. 2012;28(7–8):779–84. 10.1016/j.nut.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Peng J, Song J, Han J, Chen Z, Yin X, Zhu J, et al. The relationship between tooth loss and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular diseases, and coronary heart disease in the general population: systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NHJ. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):126. http://www.hqlo.com/content/8/1/126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.García Pérez A, Rodríguez González KG, Rodríguez Chávez JA, Velázquez-Olmedo LB. Marginalization and tooth loss in older Mexican adults. Community Dent Health. 2023;40(4):242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urzua I, Mendoza C, Arteaga O, Rodríguez G, Cabello R, Faleiros S et al. Dental caries prevalence and tooth loss in chilean adult population: First national dental examination survey. Int J Dent. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Toniazzo MP, Amorim P, de Muniz SA, Weidlich FWMG. P. Relationship of nutritional status and oral health in elderly: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(3):824–30. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Nascimento GG, Leite FRM, Conceição DA, Ferrúa CP, Singh A, Demarco FF. Is there a relationship between obesity and tooth loss and edentulism? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(7):587–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich T, Webb I, Stenhouse L, Pattni A, Ready D, Wanyonyi KL, et al. Evidence summary: the relationship between oral and cardiovascular disease. Br Dent J. 2017;222(5):381–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin HS. Association between the number of teeth and hypertension in a study based on 13,561 participants. J Periodontol. 2018;89(4):397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel MH, Kumar JV, Moss ME. Diabetes and tooth loss: an analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2004. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;140(5):478–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao W, Wang X, Wang X, Cai Y, Luan Q. Association of cognitive function with tooth loss and mitochondrial variation in adult subjects: a community-based study in Beijing, China. Oral Dis. 2016;22(7):697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430–9. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Moffat K, Mercer SW. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today’s healthcare systems. BMC Fam Pr. 2015;16(1):15–7. 10.1186/s12875-015-0344-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.De Carvalho Yokota RT, Van Der Heyden J, Johanna Nusselder W, Robine JM, Tafforeau J, Deboosere P, et al. Impact of chronic conditions and multimorbidity on the disability burden in the older population in Belgium. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(7):903–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabbri E, An Y, Zoli M, Simonsick EM, Guralnik JM, Bandinelli S, et al. Aging and the burden of multimorbidity: associations with inflammatory and anabolic hormonal biomarkers. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(1):63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zamorano P, Muñoz P, Espinoza M, Tellez A, Varela T, Suarez F, et al. Impact of a high-risk multimorbidity integrated care implemented at the public health system in Chile. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Estimaciones y proyecciones de la población de Chile 1992–2050. 2018.

- 18.Vargas I, Barros X, Fernández MJ, Mayol M. Rediseño en el abordaje de personas con multimorbilidad crónica: desde la fragmentación al cuidado integral centrado en las personas. Rev Med Clin Condes. 2021;32(4):400–13. https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-revista-medica-clinica-las-condes-202-articulo-rediseno-el-abordaje-personas-con-S0716864021000651

- 19.Ministerio de Salud. Estrategia de cuidado integral centrado en las personas para la promoción, prevención y manejo de la cronicidad en contexto de multimorbilidad. 2021. https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Marco-operativo_-Estrategia-de-cuidado-integral-centrado-en-las-personas.pdf

- 20.Margozzini P, Berríos R, Cantarutti C, Veliz C, Ortuno D. Validity of the self-reported number of teeth in Chilean adults. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein SL, Toll BA. Ask about smoking, not quitting: a chronic disease approach to assessing and treating tobacco use. Addict Sci Clin Pr. 2019;14(1):29. 10.1186/s13722-019-0159-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Mariño R, Giacaman RA. Patterns of use of oral health care services and barriers to dental care among ambulatory older Chilean. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):1–7. 10.1186/s12903-016-0329-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mariño RJ, Cueto A, Badenier O, Acevedo R, Moya R. Oral health status and inequalities among ambulant older adults living in central Chile. Community Dent Heal. 2011;28(2):143–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northridge ME, Ue FV, Borrell LN, De La Cruz LD, Chakraborty B, Bodnar S, et al. Tooth loss and dental caries in community-dwelling older adults in northern Manhattan. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bomfim RA, Cascaes AM, de Oliveira C. Multimorbidity and tooth loss: the Brazilian National Health Survey, 2019. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2311. 10.1186/s12889-021-12392-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Zhang Y, Leveille SG, Shi L. Multiple chronic diseases Associated with tooth loss among the US Adult Population. Front Big Data. 2022;5(July):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garin N, Koyanagi A, Chatterji S, Tyrovolas S, Olaya B, Leonardi M et al. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, Population-Based, Multi-country Study. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci 71(2):205–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Graves DT, Corrêa JD, Silva TA. The oral microbiota is modified by systemic diseases. J Dent Res. 2019;98(2):148–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor JJ, Preshaw PM, Lalla E. A review of the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol 40(Suppl 14). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Ucuncu MY, Topcuoglu N, Kulekci G, Ucuncu MK, Erelel M, Gokce YB. A comparative evaluation of the effects of respiratory diseases on dental caries. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margozzini P, Passi Á, Encuesta Nacional de Salud ENS. 2016–2017: un aporte a la planificación sanitaria y políticas públicas en Chile. ARS med. 2018;43(1):30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haworth S, Shungin D, Kwak SY, Kim HY, West NX, Thomas SJ, et al. Tooth loss is a complex measure of oral disease: determinants and methodological considerations. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46:555–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberto LL, Silveira MF, De Paula AMB, Ferreira E, Ferreira E, Martins AMEDBL. Haikal DS Ana. Contextual and individual determinants of tooth loss in adults: a multilevel study. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston MC, Crilly M, Black C, Prescott GJ, Mercer SW. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur J Public Heal. 2019;29(1):182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Facultad de Odontología - Universidad de Chile. Aprobada atención periodontal para pacientes con Diabetes Mellitus. 2023. https://odontologia.uchile.cl/noticias/211184/aprobada-atencion-periodontal-para-pacientes-con-diabetes-mellitus

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Population Survey repository of the Department of Epidemiology of the Ministry of Health of the Government of Chile, http://epi.minsal.cl/encuestas-poblacionales/.