Abstract

Background

Violence against health professionals is a growing problem that affects the quality of care provided and the well-being of workers. In the Alentejo region (Southern Portugal), the Regional Health Administration has been developing strategies to prevent and combat this phenomenon, namely, through the implementation of the Action Plan for the Prevention of Violence in the Health Sector. Violence in the health sector includes all situations in which a worker in the Ministry of Health's health institutions is exposed to any type of violence related to their work, putting their safety, well-being or health at risk, or that of others. The aim of this study was to analyze the perceptions and practices of local focal points (e.g.,departments, services, offices or functional units) on violence against health professionals in the Alentejo region.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were carried out local focal points in the Alentejo region. The sampling was selected for convenience from different health units. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analyzed according to the analysis protocol of the IRaMuTeQ software (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) version 0.7 alpha 2.

Results

In total, 43 interviews were conducted between February and April 2024. Interviews revealed that local focal points face various challenges in combating violence against health workers. The lack of specific training, the scarcity of security resources and the culture of underreporting were some of the obstacles identified. However, participants also stressed the importance of teamwork, effective communication and institutional support in dealing with this problem.

Conclusions

Violence against health professionals is a worrying reality that requires effective measures to prevent and combat it, requiring a coordinated and multifaceted response. Local focal points play a key role in this process, but they need adequate training, resources and institutional support. Comprehensive and regular training programs on violence, interpersonal communication and conflict management, and investment in security resources, including physical and technological measures, should be implemented in health facilities. Clear protocols should be created for dealing with situations of violence and a culture of reporting situations of violence to health professionals should be promoted, as well as the monitoring of victims by the authorities involved in cases of violence. Ongoing training and the simulation of real-life scenarios are crucial for preparing professionals to effectively manage situations of violence.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-024-11949-2.

Keywords: Primary Prevention, Workplace Violence, Healthcare Workers, Violence, Aggression

Introduction

Violence at work has become an alarming phenomenon worldwide [1] and is a public health problem [2]. Violence in the health sector is considered to be "all situations in which a worker, regardless of their legal status, performing duties in an institution providing health care or services of the Ministry of Health, regardless of their legal nature, is subjected to any type of violence in conditions related to their work, including traveling to and from work, putting their safety, well-being or health or that of others at risk, directly or indirectly" [3]. Violence against health professionals is a phenomenon that affects the quality of health services and the well-being of workers worldwide [2].

Violence and harassment affect all groups of healthcare workers and work environments in the healthcare sector. In a 2019 study, 62% of healthcare workers reported experiencing violence in the workplace [4]. Verbal abuse (58%) was the most common form of nonphysical violence, followed by threats (33%) and sexual harassment (12%) [4].

Prioritizing the prevention of violence against health professionals is essential, and various international and national instruments have been developed and implemented in public policy. The International Labor Office (ILO), the International Council of Nurses (ICN), the World Health Organization (WHO) and Public Services International (PSI) launched a joint programme in 2000 with the aim of developing sound policies and practical approaches to preventing and eliminating violence in the health sector. As a result of this programme, a manual titled "WHO/ILO/ICN/PSI: Framework guidelines for addressing Employment Violence in the Health Sector" was launched in 2003 [5]. It is essential that interventions capable of preventing and reducing violence are planned and implemented using intersectoral and multidisciplinary approaches that involve all professionals, encourage commitment and responsibility in preserving rights and building a work environment permeated by a culture of peace [6].

In Portugal, the National Programme for the Prevention of Violence in the Life Cycle was launched in 2020, including the Action Plan for the Prevention of Violence in the Health Sector [7]. According to data from the Portuguese Directorate-General of Health (DGS®), in 2023, 1036 cases of violence against health professionals were recorded in the National Incident Reporting System (NOTIFICA®), a decrease of 37% compared to that in 2022, when 1,632 incidents were recorded. However, this figure is far below the number of cases monitored by the health institutions themselves, which stood at 3,0241 cases between the beginning of 2022 and June 2023. The Local Health Units use different platforms to record internal occurrences, namely, the Risk Management Support System (SAGRIS®) and Health Event & Risk Management (HER +) in conjunction with the NOTIFICA® platform, which may contribute to this discrepancy in the number of cases reported by the DGS®.

In 2022, the Portuguese Presidency of the Council of Ministers, recognizing violence against health professionals as a phenomenon that affects the quality of services, drew up the Action Plan for the Prevention of Violence in the Health Sector, which, as part of other programmes, calls for the implementation of security measures to mitigate situations of violence in this sector [3]. In this action plan, functional structures called “operational groups” have been created at regional, institutional and local level. The Regional Operating Group is the level of the Regional Health Administration; the Institutional Operating Group refers to health establishments or services; and the Local Operating Group refers to departments, services or functional units [3], at each of these administrative levels of the National Health System, these “operational groups” are coordinated by a person, designated for this function, called a “focal point”, whose function is to coordinate the “operational group” of which he is a member.

No study was found so far on the dynamics of these operational groups in preventing violence in the health sector in the Brazilian Unified Health System or in any other country. In the southern region of Portugal, in Alentejo, the problem of violence in this sector is visible; in 2023, 98 episodes of violence against health professionals were recorded and reported.2 Given this gap, we realized that it would be important to know how the GOLs work and, consequently, the role of the individuals who are part of them in the health institutions of the Alentejo, namely in relation to the prevention of situations of violence against health professionals and, in turn, their actions in the face of these same situations of violence.

This article presents the perspective of the Focal Points on Violence against Health Professionals in the Alentejo region, addressing the causes and types of violence and the prevention strategies involved. In this way, we aim to contribute to the public debate on the need for measures to protect health professionals and promote a safe and healthy workplace. In this sense, we intend to pursue the following research question: What are the perspectives and practices of local focal points on violence against health professionals in the Alentejo region?

We set out to analyze the perceptions and practices of local focal points on violence against health professionals in the Alentejo region.

Methods

Study design

This was a descriptive, exploratory study of a qualitative nature. This study was carried out in the Local Health Units of the Alentejo Region. The methods section is reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR), with the aim of making aspects of the research transparent by providing clear standards for reporting qualitative research.

We believe it is important to clarify what is meant by health professionals and the workplace. In this sense, according to the World Health Organization, health professionals study, advise on or provide preventive, curative, rehabilitative and health-promoting health services, based on a wide range of theoretical and factual knowledge regarding the diagnosis and treatment of diseases and other health problems. The required knowledge and skills are usually obtained as a result of studies at a higher education establishment in a health-related field over a period of 3 to 6 years, leading to a first-cycle degree or higher qualification [8]. Workplace is considered to be the place where the worker is located or from where or to where he must go by virtue of his work, in which he is directly or indirectly subject to the employer's control [9].

Participants recruitment

The population consisted of 140 individuals working in local focal points, which were contacted by the research team. These individuals are health professionals from different professional areas, namely nurses, doctors, psychologists and social workers.

Nonprobabilistic convenience sampling was used [10] among the Local Operating Group provided by the institutions. The initial invitations were sent by email to the Institutional Working Group, which speeded up contact; the local focal points of the Alentejo Local Health Units were invited to take part in the study, and the date and time of the interview were scheduled. The local focal points were included in the study according to their willingness to participate; we aimed to interview until we reached data saturation, we considered saturation when the data collection would not produce any more themes [11]. We considered that we had reached data saturation when there began to be significant repetition of concepts, suggesting adequate sampling.

Semi-structured interviews

The data collection method involved an in-depth semi-structured interview with open-ended questions that allowed for the development of answers and narratives, following a previously constructed script with guiding questions supported by scientific evidence to achieve the objectives set for the study (supplementary material).

Data collection procedures

The interviews were carried out in locations defined by each healthcare institution, taking into account the proximity of the interviewee, with appropriate and environmental conditions ensuring the confidentiality of the interviewee. Each interview lasted an average of 30 min and was recorded with the interviewee's authorization.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed using the "Transcribe" feature in the Microsoft 365 Office. After the interviews were transcribed in full and to ensure the credibility and reliability of their content, the transcripts were validated by two of the project's researchers, ensuring the veracity of the information.

The text was formatted accordance with the guidelines of the IRaMuTeQ software analysis protocol (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) version 0.7 alpha 2, giving rise to the corpus that was submitted to the software.

The interviews were coded (int_01 to int_43), as were the variables (location, type of care and focal point). The corpus of the analysis was made up of 43 Initial Context Units, with each interview corresponding to an initial context unit, each starting with a defined command line: **** *int_01 *lo_1 *tc_2 *pf_3. The software transforms these Initial Context Units into context-elementary units (CEUs).

The CEUs are made up of the text segments classified according to their respective vocabularies, which share similarities, and different vocabularies to the CEUs of other classes.

Ethical considerations

This study is part of the "Violence against Health Professionals in the Alentejo Region" project, which was funded by the "CHRC Research Grant 2022". This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Évora (No. 22187). The necessary authorizations to carry out the interviews were also granted by the ethics committees of each of the institutions involved. To ensure the protection of the participants, all anonymity and confidentiality measures were implemented. The interviewees were informed in detail about the study, including its purpose and potential contributions. Each participant provided informed consent at the beginning of the interview.

Results

Descending hierarchical classification

We conducted 43 interviews with local focal points working in a Local Health Unit, hospital services and primary health care services between February and April 2024. The interviewees were nurses and doctors from different services.

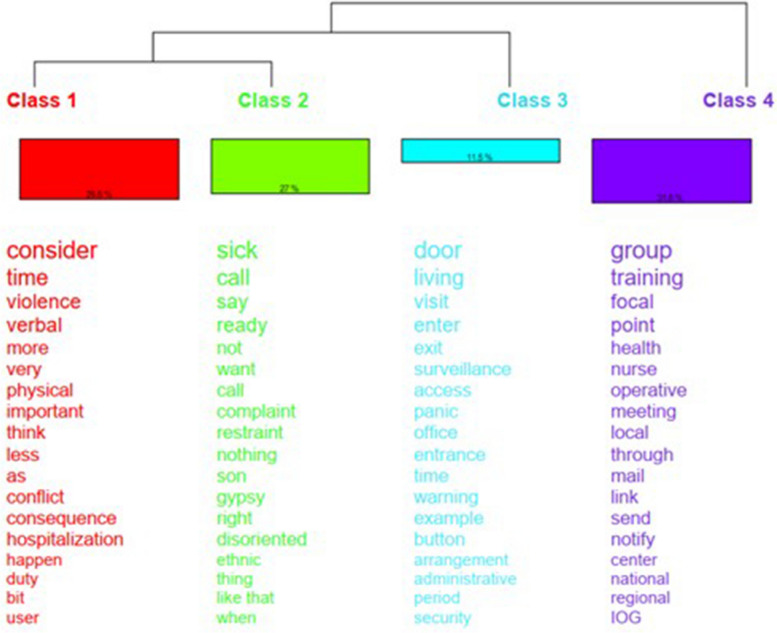

By analyzing interviews with local focal points, we found that 1842 CEUs were formed. Of these 1842 CEUs, the software classified 1605 text segments, with a vocabulary richness (the richness of vocabulary refers to the number of words that appear only once in the entire corpus) of 87.13%, from which four classes emerged by descending hierarchical classification (DHC) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Dendrogram of the descending hierarchical classification of the local operating group interviews

The processing of the interview data generated a textual corpus that was subsequently classified into thematic categories, revealing the representativeness of the content and the most representative words in each class, which were named as follows:

Class 1—Perception of the management of violence in health units

Class 2—Situations with a high risk of violence

Class 3—Measures to prevent violence in the unit

Class 4—Role of training in managing situations of violence

The visualization in Fig. 1 shows that classes 4 and 3 were formed first. Subsequently, classes 1 and 2 were divided. According to our factor analysis, the intersection of classes 1 and 2 is fairly representative of professionals' perceptions of managing the phenomenon of violence in health units and situations with a high risk of violence, with the themes of classes 3 and 4 being more distant, namely, measures to prevent violence in the unit and the role of training in managing situations of violence.

With regard to the percentages obtained for each of the classes, it was found that class 4 comprises 508 CEUs, with a percentage of 31.65% according to the total number of CEUs and is the most representative. This is followed by class 1, which comprises 479 CEUs, representing 29.84% of the total; class 2, with 433 CEUs representing 26.98%; and class 3, including 185 CEUs, representing 11.53%.

Factor correspondence analysis

Factor correspondence analysis (CFA) carried out using the CHD represents, on a Cartesian plane, the different words and variables associated with each of the DHC classes.

For the formation of each class, we present the most significant contribution of each of the variables coded in the command line for each of the interviews: for class 2, the focal points coded with 04, 13 and 40 contributed; for class 1, the focal points coded with 45 and 35 contributed; for class 3, the focal points coded with 26, 06 and 08 and the hospital care typology contributed; and finally, for class 4, the focal point coded with 24 and the primary health care typology contributed most.

The strongest words in the interviews were "no", "violence", "person" and "training", and we noted that the words "no" and "violence" were the most prominent words in all the interviews. The words "no" are included in the text segments "We do not value it", "We do not identify it", "We do not notify it", and "We're not awake"; the words "violence" are highlighted in the expressions "violence in the life cycle", "violence against professionals", "violence between professionals", "violence in this sector" and "violence is not about working in a hurry".

Thematic categories

From data analysis we extracted four thematic categories, represented by classes: Class 1—Perception of the management of violence in health units; Class 2—Situations with a high risk of violence; Class 3—Measures to prevent violence in the unit e a Class 4—Role of training in managing situations of violence.

Class 1—perception of the management of violence in health units

With regard to Perceptions of how to manage the phenomenon of violence in health units, we were able to see in the analysis of the interviews different perspectives on how to deal with violence against health professionals. The focal points mention strategies for preventing this complex and multifaceted phenomenon of violence, emphasizing communication and conflict management, as well as the need for preventive measures to combat the trivialization of verbal violence. All these strategies require a multidisciplinary approach that involves the involvement of different health professionals at the institutions in the search for joint solutions for successful measures.

Several focal points emphasize the importance of effective communication and conflict management as key strategies for preventing the escalation of violence:

"…how do we make the best communication so as not to escalate into violence? I think that is conflict management, communication and then self-defense, as a last resort, but we never want to get to that point…" (int_33).

"…I think one thing that is very important, and now I have remembered that we should work on preventing violence, is communication, assertiveness, I think we have a lot to work on and it can help control a lot of things…” (int_31).

Education and training in communication techniques and conflict management, was one of the suggestions presented by some interviewees:

"…but the reality is that we have changes in terms of training, even though we already have some training in this area, we can never have too much, but the subject of assertive communication is an essential point…" (int_38).

Another aspect reported was the need to combat the vulgarization of verbal violence:

"…verbal violence is not valued, and I think it becomes a trivial thing because nobody gets physical pain, it is not something you see…" (int_35).

"…we do not respond to aggression if it is verbal.…" (int_25).

Awareness raising of health professionals is essential stretegy for helping individuals identify and report cases of violence. Some focal points expressed a concern about the trivialization of verbal violence, in particular highlighting that it is extremely hard to report this form of abuse. This can be seen in the following segments of the text:

"If it is verbal aggression, my experience tells me; if it is verbal aggression, there's no notification…" (int_07).

"…I do not think people are aware of this problem…" (int_45).

"…as I was saying, this is something relatively recent in the institution that is being worked on; we recently did training on this topic where we learnt how to identify this violence because, often, there is this violence and we do not value it, or we do not identify it and we do not report it…" (int_01).

The issue of security structures in a hospital context was also addressed, with emphasis on the need for preventive measures and a review of the physical structure of the spaces, as well as the existence of a well-structured security service, contributing to reducing the risk of violence against healthcare professionals and conveying a feeling of trust in the institution:

"…I think that in terms of preventive measures, the hospital security service is a service that has many structural and physical gaps…" (int_45).

"… the office is spacious, you can organize it differently, sometimes you just have to change the positioning of the furniture…" (int_31).

In the interviews with the focal points, this was emphasized as follows:

"…I watched a webinar on violence prevention, how we can prevent violence by organizing physical spaces differently, and looking at our institution here…" (int_31).

"…we do training, but then as things do not happen and as people often forget what they have to do, they lose the information and I think this training should be done with some periodicity…" (int_36).

Class 2—situations with a high risk of violence

Another emerging theme in the interviews were situations with a high risk of violence, addressing the challenges and strategies for dealing with more complex situations and revealing different experiences and perceptions about what can trigger these situations of violence, as well as what safety measures exist and what is needed for more effective institutional support:

"…a verbal assault and another physical assault by that patient, so we held a kind of briefing before their shift started and made a plan of how we were going to act during the shift…" (int_07).

"…with the distribution of patients, we tried not to have that confrontation—it was a specific episode with that particular professional, it was the most striking episode, it was that episode which was then replicated by another…" (int_36).

Professional experience and communication skills within the team were identified by some interviewees as essential tools for assessing risk factors and implementing proactive measures:

"…it has to be reported immediately and action taken because if it is not for other types of physical violence, for example, from patients, what we're instructed to do is try to prevent it as much as possible…" (int_42).

"…we do not get into a direct confrontation and try to call someone, or we avoid getting into a direct confrontation and assess the person and the situation to try to protect ourselves a bit, avoid the conflict itself, even to prevent more complex episodes…" (int_40).

Protocols appropriate to the type of service should cover everything from internal communication to the activation of external authorities:

"…when there's an episode that could be more critical, which fortunately we have not had recently, we call the security guard; if we cannot, as we're all working here as a team, we contact the PSP straight away…" (int_15).

Several focal points described episodes of verbal and physical violence perpetrated by users, especially in situations of conflict or direct confrontation. Some interviewees reported that groups of certain ethnicities tend to be more prone to aggressive and violent behavior in health services. It was observed that these services have structural and physical deficiencies, which can contribute to episodes of violence. In these cases, the recommended approach is to avoid direct confrontation, call security and, if necessary, the Public Security Police (PSP) or the National Republican Guard (NRG):

"…it is conditioning my actions as a health professional, normally we try to bring people to their senses, when that is not possible we have to call a security guard, or the police…" (int_01).

"…I have had these episodes of coercion and that, the measure I usually adopt is to call the person to reason and tell them that if they do not change their behavior, I'm going to ask them to leave the service…" (int_01).

"…I think they also have to be punished because, I do not know, we have some situations with ethnic groups who come in groups, who treat people badly as soon as they enter, just because they want to, that is all…" (int_40).

Regarding notification, in the interviews the focal points mentioned the difficulty in properly notifying and referring cases of violence. Often, professionals did not report episodes, either for fear of reprisals or because they did not believe anything will be done. This makes it difficult to develop effective prevention and response strategies:

"…because we do not have problems reported, for example, so that we do not have problems reporting even if nothing comes of that complaint, that notification, but so that we know what's going on and can then justify other measures…" (int_40).

"…it is not even followed up, it is notified, it is often notified, but there's no complaint because it does not make any sense, not least because maybe in some cases people have not taken sufficient precautions, knowing that it appears to be I'm making the victim feel guilty, but that is not it…" (int_26).

"…if it is considered a crime, it is a public offence, but, for example, if you complain to the PSP about it, or against a person, whether they're a patient or a carer…" (int_07).

The various focal points mentioned the need for a paradigm shift in the approach to cases of violence. This change in mentality is considered fundamental to dealing more effectively with violence. It is fundamental to foster a culture of reporting, and health professionals should be encouraged to record all episodes of aggression, regardless of their severity, so that the institution can have a complete picture of the situation and take the appropriate measures:

"…in this so-called new approach, in particular, there is a paradigm shift; until a few years ago, there was a paradigm that the patient, even if he physically assaulted us, was always right, whether or not he had a more delicate physical or mental condition, and now the paradigm has changed; we are still building, let us say, this new approach…" (int_18).

"…for a while we did the same procedures, we called the security forces, made a notification and things went on as normal…" (int_11).

"…then nothing comes of it and then it is a hassle and then they call me and then I have a hassle with people, well, I do not know if it is because of the reprisals, but at least because of the time we waste with everything we have to do, is not it…" (int_40).

Class 3—measures to prevent violence in the unit

It is the least representative class of the corpus and, in terms of factor analysis, the one that is most distant from the others, but it is the one that brings together the preventive measures listed by the focal points. Some of these have already been mentioned in previous classes, but it is important to show which preventive measures have been implemented in the various instructions in Alentejo and what needs to be improved if professionals are to feel safe in their working environment.

Some of the focal points considered the existing prevention measures to be sufficient and relevant, particularly the training provided:

"…the topics that are covered are sufficient and pertinent and, for now, for training it has been sufficient, in relation to the physical structure of the unit we have always noticed this problem of there being an escape door, we will have to do this survey, but it has already been discussed…" (int_18).

However, others emphasized the need for improvements in terms of physical structure and a review of security protocols, which are considered risk factors by several focal points, namely, the lack of escape doors in all locations, the layout of rooms and the absence of adequate spaces for individualized care:

"…but on one side there's a door with a code and on the other side there's a door that opens without any restriction and it is on this door that I have also asked for access control, and it has not been put in yet…" (int_44).

"…the space, including the emergency room, does not have individual rooms for people to have their treatment; it is a corridor…we're also talking about the situation where we do not have permanent 24-h security, i.e., the security guard is there, but as there are only two in the institution…" (int_21).

"…so the only way we have opted is to change the location of the chair and desk so that the professional has quicker access to the exit door, but in some offices, this is not possible…" (int_33).

Another of the fundamental measures listed by the focal points was the need for the communication system to be effective so that professionals can call for help in case needed. In this case, they reported the need for panic buttons as an essential measure mentioned in the interviews:

"…we're trying to make sure that the spaces are suitable, in particular the desks for escape, the triage has been ordered, it has not been moved yet because we're waiting for a panic button, the doors have been installed which are controlled by us…" (int_26).

"…we have a system called HER + , which is the system where we can make the notification. In the past, there was a panic button; there was a panic button in the administration, and there was a panic button inside the room where we work (… however, associated with COVID, the room had to be extended, and after the extension, that panic button disappeared, so at the moment there was only a panic button at the entrance to the service, in the administration…" (int_44).

They also said that it would be very important to simulate real scenarios and periodically update their knowledge to improve their skills in these situations:

"…there will be a way of making it easier for the professional to leave quickly; if there's anything that does not fit in, the head nurse is focused on all these preventative measures, and things will take a good turn…" (int_06).

Management's commitment to the safety of professionals is fundamental to the effectiveness of preventive measures. Listening attentively to the requests of professionals, implementing the necessary structural changes and creating a safe and welcoming working environment are all responsibilities of management, as emphasized by interviewees:

"…now we're going little by little, there will certainly also be a visit to the sites to find escape points and to see what we can improve here in our physical space, which is a bit complicated, because the rooms are closed, and we do not have escape points…" (int_15).

“…the firmness of the role of the managers who bring the groups together…” (int_39).

Class 4—role of training in managing situations of violence.

The last class to be addressed is the most representative class in the corpus, the role of training in managing situations of violence. The focal points of the interviews highlighted the importance of internal training for managing situations of violence. From the text segments, we can see that most of the interviewees mentioned the lack of specific internal training for dealing with violence against health professionals, which could jeopardize the uniformity of the team's actions:

"…as I said, it is all very recent, but we have not even done internal training yet, so I only know the group from one meeting, so we have no contact with the group; we have never had contact…" (int_04).

"…I have not even done the training for colleagues that I think is pertinent, and I will also have to evaluate it with the nurse in charge, so that I can also inform colleagues of the situation and of my knowledge, also so that we can all standardize and act in the same way…" (int_10).

"…usually we are, so there is a nurse who is responsible and who calls us first, usually by email, with a date and time set, quite often even…" (int_19).

This lack of training resulted in insecurity and doubts about how to proceed in cases of aggression, and it is essential that institutions invest in training for all professionals rather than just the focal points, as was highlighted during the interviews:

"…the schemes on the intranet so that everyone knows about them and not just the focal points, that is usually how I have access to information, we do not have any measures in place yet, we have not done anything…" (int_10).

"…at the moment none has been proposed, but I think there's going to be more training in this area, I'm responsible for risk management in my service, so I have also been appointed as the focal point for violence against health professionals and that is why I went to the training…" (int_01).

References were also made to the sources of information and communication, in particular those related to the management of violence, which is generally received by the manager and passed on to the team via e-mail and meetings, and the protocols and flowcharts to be used are passed on:

"…normally, we're informed, as I'm the focal point; via the group email led by nurse x, we also get the information straight away; we also have it available when the flowcharts are approved…" (int_10).

"…the guidelines are always received by the manager, who also addresses them to us, and we try, as we are also a small group, to ensure that everyone has the same type of information…" (int_16).

Analysis of the interviews showed that the NOTIFICA® platform and platforms internal to each Local Health Unit, such as SAGRIS® and HER + , are used for reporting. Reporting episodes of violence is highly important for recording and analyzing data; therefore, this analysis must be carried out rigorously and impartially:

"…that is all it takes to stop something that could lead to verbal or even physical action, the notification is made through the internal system that is SAGRIS, there is a manager of this SAGRIS, there is a manager of this application, who happens to be the nurse manager…" (int_07).

"…the reporting of episodes of violence is always done on SAGRIS and the NOTIFICA platform, and the episodes are analyzed by a group that works with the nurse manager, who then selects another group to investigate what has been reported…" (int_19).

"…the notification of episodes of violence is done through NOTIFICA and SAGRIS, eventually additional clarifications may be requested through me, later the information is at a higher-level, at-risk management level…" (int_18).

In the analysis of the interviewees' statements, the importance of coordination with the Regional Operational Group for the most serious cases and of participation in the training of local professionals is recognized, promoting integration between institutions and the joint training of professionals. This collaborative approach is essential for guaranteeing a coordinated and effective response to situations of violence:

"…with regard to liaising with the Regional Operating Group, I know that there is, because they also had people from the regional operational group who came from Évora, for example, in that training with the police officers…" (int_37).

It was suggested by interviewees that the implementation of prevention measures can include awareness-raising campaigns and interpersonal communication training:

"…through NOTIFICA® and SAGRIS®, which is the programme here at the hospital, on the 2 platforms, we are now investing in training the focal points so that we can then pass it on to our peers, which has not happened yet…" (int_01).

In analyzing the interviews, we found that the implementation of a violence management plan is still in its infancy at many institutions, and there is a need for continuous investment in training, communication, and prevention measures. The empowerment of leaders and the participation of all professionals are essential to successful actions:

"…we were identified as groups associated with this local violence project as the GOL local operative group, through a request that the regional group made to the board of directors so that the elements that belonged to the risk management group would have associates…" (int_44).

"…. so we were not assessed as to whether our profile was suitable or not to be part of this group; we simply received a communication that it had been authorized by the board of directors and how to go about it; we would also become members of the local operative group…" (int_44).

Some professionals reported having been designated "focal points" for the issue of violence, have received additional training and have the responsibility of multiplying the knowledge acquired to the other members of the team. However, some reported difficulties in carrying out this internal training due to lack of time:

"… so we're a local operational group at the moment, so we had training; we had a first contact with information, what was intended and then at the institutional level…" (int_37).

“…no time is given to these functions…” (int_05).

Discussion

The qualitative analysis of the interviews conducted with the Local Focal Points in the Alentejo region revealed the complexity and diversity of experiences and perceptions of violence in the health sector. It is important to note that keeping the work environment safe, respectful, and favorable to clinical practice provides quality healthcare, promoting a healthy and pleasant working environment [12].

Considering the objective, the research question, and the phenomenon in question—violence against health professionals—factor analysis showed a strong interconnection between ways of dealing with violence and high-risk situations. Therefore, each of the classes emerges as a central theme, a discussion will be held based on the best literature, highlighting the most prevalent words in each class.

According to a concept analysis of violence at work, workplace violence is associated with a high turnover rate and a lack of adequate communication skills [12]. In another study, workplace violence was also defined as a strategy for building relationships between health professionals and users and improving communication skills through training courses [13] to avoid and manage possible conflicts in the workplace [14], namely, assertive communication and active listening within the team [6]; in short, taking into account Barros et al. [2], education and training in communication and conflict management techniques can increase the ability of health professionals to identify and respond to situations of violence more effectively, thus meeting what was mentioned by some focal points.

The invisibility of verbal aggression and the lack of recognition of negative impacts can contribute to the perpetuation of verbal violence; even if one does not leave physical marks, this can lead to worrying psychological consequences such as anxiety, depression, stress [15] and burnout [1]. A 2019 study [16] investigated this trivialization and the lack of preventive measures available to combat this phenomenon, showing that providing psychological support is crucial for helping professionals deal with the emotional consequences of violence [4, 16].

According to different studies, including a meta-analysis [4, 17–19], verbal violence was the subtype with the highest occurrence among health professionals, with users being the biggest aggressors, followed by users' relatives, colleagues at the same hierarchical level, managers, or colleagues from another professional group. An integrative literature review [20] also indicated that violence against health professionals is very common and can take different forms, with psychological violence being the most common, as well as situations of violence in professional-patient and/or professional-family relationships.

Some authors [13, 15] point to self-defense as a protection strategy for workplace violence through various measures that can be taken into account, namely, alarm systems and other security devices, panic buttons, portable alarms or noise devices. Another suggested strategy for increasing security would be to establish police stations in major hospitals [18].

Education sessions and training in the prevention and mitigation of workplace aggression are essential components of any workplace violence prevention programme and are considered crucial for counteracting the negative impacts of violence on institutions by providing the knowledge and skills needed to prevent aggression [13, 21]; however, the same study reports that although these education and training programmes did not reduce the number of reports of aggressive behavior against healthcare workers, there was an increase in the likelihood of healthcare workers reporting these incidents [21]. This approach undoubtedly has a positive impact on the whole issue, proving effective in minimizing the phenomenon of underreporting incidents of violence against healthcare workers [13]. It is also essential to constantly update and review safety protocols to guarantee the effectiveness of preventative measures [16].

Violence prevention must be prioritized through actions such as promoting a culture of safety, promoting peace, resolving conflicts peacefully and changing the physical environment of institutions, which are essential for building a safer and more welcoming environment [22]. The various focal points propose important measures; however, the lack of resources, the undervaluation of some subtypes of violence, such as verbal violence, and underreporting are some of the obstacles to overcome, which have also been found in other studies [23, 24] are global challenges that are highly influenced by cultural, social, and institutional issues.

When the subject is more "in-depth", the focal points highlight the ability to identify warning signs and what preventive measures are appropriate to avoid the intensification of violence, as emphasized by the Ministry of Health itself [3], which demonstrates that risk assessment tools can be adapted to identify warning signs and prevent violence, providing valuable insights for healthcare contexts. Professional experience and communication skills within the team [2] are essential tools for assessing risk factors and implementing proactive measures. The existence of clear safety protocols appropriate for the type of service is also fundamental for guiding health professionals in appropriate behavior when faced with risk situations [25].

For several years, mandatory reporting has been a fundamental tool for understanding the profile of violence, enabling epidemiological surveillance and the development of specific actions to prevent this phenomenon [26]. In Portugal, the online notification system for episodes of violence against healthcare professionals in the workplace has been available on the DGS® website since 2006. The system is based on voluntary, anonymous, confidential, and nonpunitive notifications; in 2013, it produced a Professional Notifier's Manual, which encouraged healthcare professionals to notify incidents and, at the same time, enabled the collection of information at the national level on the type of incidents and their causes, which is essential for the development of priority intervention strategies [21].

In 2020, the Action Plan for the Prevention of Violence in the Health Sector was created with the aim of preventing the occurrence of violence against health professionals, adequately addressing episodes, and mitigating their consequences. For this plan to be effective, institutions need to have an interest in this problem and be able to plan for it, empowering teams to intervene in support of and following episodes of violence.3

The main situations at high risk of violence identified include verbal and physical aggression by users, confrontations with groups of certain ethnicities, a lack of notification and appropriate referral, gaps in the physical security of environments and the need for a paradigm shift in the approach to these cases.

As a prevention strategy, the literature recommends training in communication skills, the existence of adequate safety-promoting infrastructures and resources in healthcare facilities [27] and training and capacity-building programmes for professionals, namely, through activities that promote literacy in the healthcare sector [3], as demonstrated by the Directorate-General for Health (2023).4

In fact, adopting strategies to mitigate this phenomenon is crucial for providing a safe working environment, enabling healthcare professionals to carry out their work effectively and providing quality care [20], are management responsibilities, as Pompeii [22] argues.

Limitations of the study

Although this study provides valuable information on violence against health professionals in the southern region of Portugal, it has some limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results, namely the representativeness of the sample, i.e. the sample is made up of nurses and doctors working in public institutions, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other health professional groups, as well as to professionals working in private institutions.

Conclusion

Violence against health professionals is a worrying reality that requires effective measures to prevent and combat it. The interviews conducted with the focal points show the need for joint effort on the part of professionals, institutions, and managers to guarantee a safe and welcoming working environment.

This multifaceted problem requires an integrated approach involving prevention strategies, security measures, ongoing training, and strong institutional support. Effective communication and conflict management are key elements in preventing the escalation of violence. In addition, it is essential to combat the vulgarization of verbal violence and ensure that all episodes of aggression are duly reported and dealt with. Implementing security measures, such as reviewing the physical structure of spaces and installing alarm devices, is essential for creating a safe working environment. Finally, ongoing training and the simulation of real-life scenarios are crucial for preparing professionals to deal effectively with situations of violence.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; A.C.; M.A.C.; C.S. and L.G.; methodology M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; A.C.; M.A.C.; C.S. and L.G.; software, M.O.Z..; validation, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; A.C.; M.A.C.; C.S. and L.G.; investigation, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; M.A.C. and L.G.; resources, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; M.A.C. and L.G.; data curation, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; M.A.C. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O.Z and L.G.; writing—review and editing, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; A.C.; M.A.C.; C.S. and L.G.; visualization, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; A.C.; M.A.C.; C.S. and L.G.; supervision, M.O.Z and L.G.; project administration, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; A.C.; M.A.C.; C.S. and L.G.; funding acquisition, M.O.Z; I.S.; D.C.; M.L.B.; A.C.; M.A.C.; C.S. and L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present publication was funded by Fundação Ciência e Tecnologia, IP national support through CHRC (UIDP/04923/2020).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Évora (No. 22187). The necessary authorizations to carry out the interviews were also granted by the ethics committees of each of the institutions involved.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yang SZ, Wu D, Wang N, Hesketh T, Sun KS, Li L, et al. Workplace violence and its aftermath in China’s health sector: implications from a cross-sectional survey across three tiers of the health system. BMJ Open. 2019Sep;9(9):e031513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barros C, Sani A, Meneses RF. Violência contra profissionais de saúde: Dos discursos às práticas. Configurações. 2022Dec 31;30:33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portugal, Conselho de Ministros. Aprova o Plano de Ação para a Prevenção da Violência no Setor da Saúde. Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.o 1/2022 2022 p. 7–19. Available from: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2022/01/00300/0000700019.pdf.

- 4.Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, Lu K, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019Dec;76(12):927–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hw WHO. Framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva: ILO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes H, Sala DCP, Horta ALDM. Violence in health care settings: rethinking actions. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018Oct;71(5):2599–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministério da Saúde. Programa Nacional de Prevenção da Violência no Ciclo de Vida Plano de Ação para a Prevenção da Violência no Setor da Saúde [Internet]. Lisboa: Direção-Geral da Saúde; 2020. 84 p. Available from: https://www.sns.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/DGS_Plano_AP_Violencia_S_Saude_2020-02-29-FINAL.pdf.

- 8.World Health Organization. Classifying health workers: mapping occupations to the international standard classification. WHO. 2019.

- 9.Assembleia da República. Lei n.o 102/2009 de 10 de setembro. Regime jurídico da promoção da segurança e saúde no trabalho. Diário da República, 1a série, no 176. 2009;6167–92.

- 10.Marôco J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics. 8a. ReportNumber; 2021. 1022 p.

- 11.Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, Young T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018Dec;18(1):148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Qadi MM. Workplace violence in nursing: A concept analysis. J Occup Health. 2021Jan 10;63(1):e12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Ettorre G, Pellicani V, Mazzotta M, Vullo A. Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in Emergency Departments. Acta Biomed Atenei Parm. 2018;89(4-S):28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang YC, Hsu MC, Ouyang WC. Effects of Integrated Workplace Violence Management Intervention on Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy, Goal Commitment, Attitudes, and Confidence in Emergency Department Nurses: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022Feb 28;19(5):2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Miller M, Howard PK. Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Risk Factors and Protective Strategies. Rehabil Nurs. 2010Sep;35(5):177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trindade LDL, Ribeiro ST, Zanatta EA, Vendruscolo C, Dal Pai D. Agressão verbal no trabalho da Enfermagem na área hospitalar. Rev Eletrônica Enferm. 2019;21. Available from: https://www.revistas.ufg.br/fen/article/view/54333. Cited 2024 Jun 26.

- 17.Lima GHA, Sousa SDMAD. Violência psicológica no trabalho da enfermagem. Rev Bras Enferm. 2015;68(5):817–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu L, Dong M, Wang SB, Zhang L, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, et al. Prevalence of Workplace Violence Against Health-Care Professionals in China: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Observational Surveys. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020Jul;21(3):498–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Omari H. Physical and verbal workplace violence against nurses in J ordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(1):111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pimenta ACP, Lima LP, Lemes MA, Da Silva PS, Lima IAB. Violência ocupacional contra profissionais de saúde no Brasil: uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Braz J Dev. 2023;9(05):17926–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geoffrion S, Hills DJ, Ross HM, Pich J, Hill AT, Dalsbø TK, et al. Education and training for preventing and minimizing workplace aggression directed toward healthcare workers. Cochrane Work Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;2020(9). Available from: https://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD011860.pub2. Cited 2024 Jun 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pompeii L, Benavides E, Pop O, Rojas Y, Emery R, Delclos G, et al. Workplace Violence in Outpatient Physician Clinics: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020Sep 10;17(18):6587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leira CJ, Ferreira MJDSB, Nobre JRP. Violência contra os profissionais de saúde no contexto de uma unidade de cuidados na comunidade: um estudo qualitativo. Rev Ibero-Am Saúde E Envelhec. 2023;9:79–98 Páginas. [Google Scholar]

- 24.García-Moreno C. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger S, Grzonka P, Frei AI, Hunziker S, Baumann SM, Amacher SA, et al. Violence against healthcare professionals in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis of frequency, risk factors, interventions, and preventive measures. Crit Care. 2024;28(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garbin CAS, Dias IDA, Rovida TAS, Garbin AJÍ. Desafıos do profıssional de saúde na notifıcação da violência: obrigatoriedade, efetivação e encaminhamento. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20(6):1879–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoimenidis A. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work Consolidated Annual Activity Report 2022. Bilbao. Spain: European Agency for Safety and Health at Work; 2023. 188 p. Available from: https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Consolidated%20Annual%20Activity%20Report%202022.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.