Abstract

There is currently a lack of pathological research on the hair loss caused by stress, and there is no effective treatment available. It has been previously reported that stress can cause sympathetic nerve activation and release of norepinephrine, which binds to beta‐2 adrenergic receptors and causes a series of chemical reactions. Propranolol, as a beta‐2 adrenergic receptors blocker, competitively antagonizes the effects of norepinephrine. We initiated a single‐center clinical trial with a self‐controlled approach to assess the effectiveness of topical applied hydrochloride salt of propranolol solution in preventing stress‐induced hair loss in humans. A total of 20 volunteers were enrolled. 14 out of 20 volunteers experienced a significant reduction in the number of hair loss (p < .05) after using hydrochloride salt of propranolol solution. No local adverse reactions were found. This study showed hydrochloride salt of propranolol solution may alleviate stress‐induced alopecia to a certain extent, which provides clues for the development of pharmaceutical interventions for the treatment of stress‐induced alopecia.

Keywords: Beta‐2 adrenergic receptors, hair loss, norepinephrine, propranolol, stress

We conducted a study to evaluate the effectiveness of topically applied propranolol hydrochloride (PP‐HCl) solution in preventing stress‐induced alopecia in humans. Volunteers were recruited and screened, and 20 volunteers were included in the trial phase. The results showed that topical propranolol can relieve the symptoms of stress‐induced alopecia.

Abbreviations

- AP

apocrine gland

- BU

bugle

- CX

cortex/cuticle

- EC

endothelial cells

- FIB

fibroblasts

- IFE B

IFE basal (1 pop.)

- IFE C

IFE cycling

- IFE SB

IFE suprabasal

- IMM

immune cells

- IRS

inner root sheath

- LB

lower bugle

- LC

Langerhans' cells

- MED

medulla

- MEL

melanocytes

- Na

norepinephrine

- ORS

outer root sheath

- PP‐HCl

hydrochloride salt of propranolol

- PSS

perceived stress Scale

- RMSD

root‐mean‐square deviation

- scRNA‐seq

single‐cell transcriptome sequencing

- SG

sebaceous gland

- t‐SNE

t‐distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

- β2AR

beta‐2 adrenergic receptors

- βAR

beta‐adrenergic receptors

1. INTRODUCTION

Empirical evidence strongly supports that stress is associated with accelerated hair loss, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 while few medications are available for stress‐related hair loss. Recent reports have highlighted that stress can induce the activation of cutaneous sympathetic nerves. This activation results in the heightened release of norepinephrine (NA), a key neurotransmitter. Notably, NA possesses the ability to bind to beta‐2 adrenergic receptors (β2AR). 9 , 10 This binding sets off a series of molecular alterations, suggesting a complex interplay between stress‐induced neural activity and subsequent biochemical responses in the skin. 11 We hypothesized that β2AR are implicated in stress‐induced hair loss. To test this hypothesis, we selected specific inhibitors of β2AR and conducted single‐center clinical trials.

Propranolol, a widely used non‐selective beta‐adrenergic receptor (βAR) blocker, acts by competitively antagonizing the effects of norepinephrine and epinephrine. Due to its action on multiple βAR subtypes, propranolol elicits a broad spectrum of central and peripheral effects. This versatility makes it suitable for treating a variety of conditions. 12 It has rapidly gained prominence in the clinical management of hypertension, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, anxiety, and essential tremor. Propranolol's multifaceted pharmacological profile underscores its significance as a therapeutic agent in addressing a range of medical conditions. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17

Considering the well‐established safety and efficient percutaneous absorption of propranolol, 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 which was further proved in two of our recent studies. 23 , 24 we conducted a study to evaluate the effectiveness of topically applied hydrochloride salt of propranolol (PP‐HCl) solution in preventing stress‐induced hair loss in humans.

2. METHODS

2.1. Adrenergic receptors' expression pattern analysis

The single‐cell transcriptome datasets of GSE129611 from GEO were also used to figure out the expression pattern of adrenergic receptors in human hair follicle. 25 The quality control standard for each dataset was based on the original studies when available. After that, the cell cluster annotations were accomplished depending on the cell makers reported in the previous studies and visualized using the t‐distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t‐SNE) method.

2.2. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation

Docking studies were conducted using Swiss Model and CB Dock2, with detailed procedures outlined previously. 26 , 27 In brief, we identified the UniProtKB accession codes of human β2AR from the UniProt Knowledgebase, generated a three‐dimensional structural model of the human β2AR using Swiss Model, and employed CB Dock2 to perform docking with the small molecule compound propranolol. Based on the PLIP web tool, we performed a visual analysis of the β2AR‐propranolol interaction. 28 Finally, a 100‐nanosecond all‐atom molecular dynamics simulation was performed using GROMACS 2020.6‐MODIFIED and the CHARMM36 force field. The results were analyzed and determined for root‐mean‐square deviation (RMSD).

2.3. Ethical statements

We initiated a proof‐of‐concept clinical trial titled “A single‐center clinical trial of topical propranolol application for the prevention of stress or anxiety‐induced hair loss” at the Clinical Trials Unit in the Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital. This trial has been officially registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, under the identifier ChiCTR2300068541, which can be accessed for details at https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=178080. The protocol for this intervention trial was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital, bearing the reference number 2022‐KY‐KZ‐229‐02. Our trial was meticulously conducted in strict accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring adherence to international standards of research ethics and participant safety.

2.4. Study design, patient eligibility, and treatment

This study was designed as a single‐center clinical trial with a self‐controlled approach.

Inclusion Criteria: Participants were required to have clinically diagnosed symptoms of increased hair loss due to psychological factors such as anxiety, high work pressure, irregular work and rest patterns, or heightened stress. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used to assess the psychological stress levels of volunteers. Prior to participation, informed consent was obtained through the signing of a consent form.

In this experiment, it is stipulated that the difference in hair shaft length/number/thickness between the experimental drug treatment and the placebo treatment is ≥2 times and p < .05, which can be considered that there is a significant difference in hair follicle mitochondrial activity before and after the experiment. According to the preliminary experiment, the number of samples with significant differences in treatment between the experimental group and the control group is at least 10 samples, and the standard deviation before and after the experiment is 5.2. According to Formula (1), this experiment requires at least 10 samples, so this study plans to recruit 30 volunteers and use the PSS to assess the psychological stress level of all volunteers, and select 20 volunteers with higher psychological stress levels to join the group.

| (1) |

The treatment regimens used in this study are propranolol regimen and control regimen. The propranolol regimen consisted of a mixed solution of PP‐HCl (1 mg/mL), water, ethanol, and menthone. In contrast, the control regimen was a blend of ethanol, water, and menthone, devoid of the active drug. Both groups of drugs are provided in the form of sprays and are applied to the scalp.

Before receiving the propranolol regimen, all volunteers need to use the control regimen blank drug for 15–20 days (once in the morning and once in the evening). Each time the drug is used, the scalp should be exposed as much as possible. After applying the drug, the scalp should be fully massaged for 3 min to promote drug absorption, and the number of hairs that fall off when washing the hair should be counted. After that, the propranolol regimen drugs are used in the same way for 15–20 days and the number of hairs that fall off when washing the hair is counted. The final comparison was made between the number of hair shed during the treatment with the blank regimen and the propranolol regimen.

To maintain the integrity of the study and account for individual differences, participants were instructed to avoid other hair treatments during the study period. This included haircuts, perms, and hair dyes, to prevent any external influences that could potentially affect their hair condition.

2.5. Assess safety

As the test drug is a topical spray with a solvent comprising ethanol, menthone, and water, there is a potential for patients to exhibit allergic reactions on the scalp, leading to localized inflammatory responses such as redness, swelling, itching, and pain. Additionally, some patients may experience varying degrees of peeling. It is imperative to observe and monitor whether patients develop the aforementioned local adverse reactions subsequent to treatment.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Human hair follicle scRNA‐seq and immunofluorescence staining

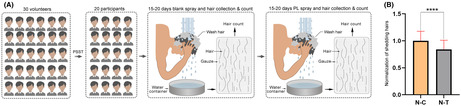

Utilizing single‐cell transcriptome sequencing (scRNA‐seq) data, our study analyzed the expression patterns of adrenergic receptors across various human skin cell types. This comprehensive analysis revealed a specific and noteworthy pattern: cells from the Interfollicular Epidermis Suprabasal (IFE SB) layer, the Bulge (BU) region, and the Outer Root Sheath (ORS) of hair follicles universally express the ADRB2 gene, which encodes β2AR. Intriguingly, these cell types exhibited almost no expression of other adrenergic receptors, highlighting a unique and selective expression profile of β2AR in these skin regions (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Human hair follicle scRNA‐seq and immunofluorescence staining. (A) t‐SNE visualization showing all cell types found in human skin and the expression of adrenergic receptors for each cell types found in this study. AP, apocrine gland; BU, bugle; CX, cortex/cuticle; EC, endothelial cells; FIB, fibroblasts; IFE B, IFE basal (1 pop.); IFE SB, IFE suprabasal; IFE C, IFE cycling; IMM, immune cells; IRS, inner root sheath; LC, Langerhans' cells; LB, lower bugle; MED, medulla; MEL, melanocytes; ORS, outer root sheath; SG, sebaceous gland. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of β2‐AR and its secondary antibody control staining on human hair follicles.

Further complementing our transcriptomic findings, results from immunofluorescence staining analyses provided visual confirmation of these observations. These analyses demonstrated that β2AR is highly expressed in human hair follicles (Figure 1B). The convergence of data from both scRNA‐seq and immunofluorescence staining solidifies the notion that β2AR plays a potentially significant role in the biology of human skin, particularly in the context of hair follicle structure and function.

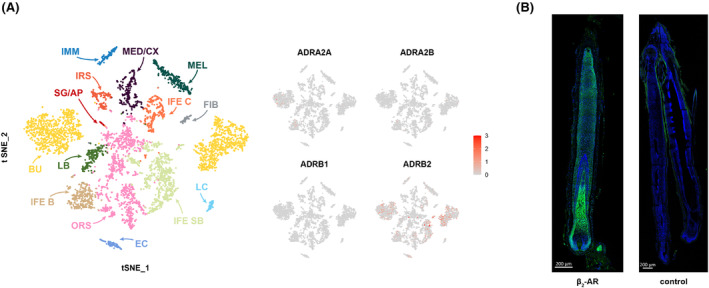

3.2. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation

In our study, we initially employed homology modeling methods to construct a detailed three‐dimensional structural model of the human β2AR. Following this, we utilized molecular docking techniques to facilitate the interaction between β2AR and the small molecule compound, propranolol. The docking results were significant, revealing that propranolol correctly and efficiently binds to the designated protein pocket of β2AR, forming hydrogen bonds specifically with the TYR‐308 residues on the receptor (Figure 2A). This interaction suggests a precise and functional binding mechanism.

FIGURE 2.

Docking parameters of the propranolol. (A) Interactions of propranolol at the receptor active site. (B) RMSD backbone of the propranolol‐β2AR complexes throughout 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation.

To further investigate the stability of this ligand‐receptor complex under physiological conditions, we conducted a comprehensive 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation of the propranolol‐β2AR complex (Figure 2B). Throughout the simulation duration, propranolol consistently demonstrated stable binding within the protein cavity of β2AR. Notably, the jitter observed in the root‐mean‐square deviation (RMSD) curve was attributed to the inherent conformational flexibility of the small molecule, as it underwent continuous adjustments within the binding cavity. Such behavior is typical in molecular dynamics simulations and reflects the dynamic nature of molecular interactions.

Crucially, the simulation data indicated that there were no instances of propranolol dissociating from β2AR. This persistent binding within the protein cavity underscores the stability and efficacy of the interaction between propranolol and the β2AR, reinforcing the potential significance of this interaction in a biological context.

3.3. Drug Clinical Trials

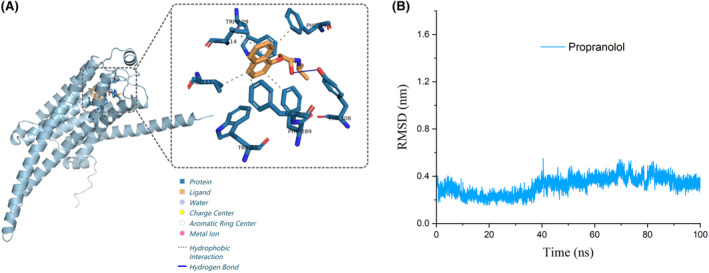

A total of thirty volunteers, ranging in age from 20 to 40 years and inclusive of all genders, were initially recruited for the study. At the same time, the PSS test will be conducted on the recruited volunteers. The PSS results were crucial for identifying volunteers experiencing significant levels of stress. Based on these results, 20 of the 30 volunteers were identified as having a considerable level of perceived stress, qualifying them for inclusion in the final phase of drug testing (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3.

β2AR blocker reduces stress‐associated hair loss in human. (A) The procedure of participant recruitment and shed hair documenting during the human clinical studies. (B) A comparative analysis showed that there was a significant decrease (p < .05) in the number of shed hairs after PP‐HCl application in 14 of the 20 participants. All data are mean ± SD. ns means p >.05; *p ≤.05; **p ≤.01; ***p ≤.001; ****p ≤.0001.

Of these 20 selected volunteers, the gender distribution was relatively balanced with 11 males and 9 females. Most volunteers were within the 20–30 age bracket, with a smaller proportion (3 volunteers) in the 30–40 age range. The diversity of our volunteer group was notable, spanning various professional backgrounds. This included one university professor, five young doctors, five doctoral students, and seven undergraduate students who were nearing graduation. The inclusion of individuals from varied professional environments added a layer of diversity to our study, potentially enriching the data with a wide range of stress experiences and perspectives. (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Volunteers characteristics.

| Characteristic | All | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 20) | (N = 9) | (N = 11) | |

| Age group | |||

| 20–30 | 17 (85%) | 9 (100%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| 30–40 | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Profession | |||

| Professor | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Young doctor | 5 (25%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| PhD candidate | 5 (25%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Graduating undergraduate student | 7 (35%) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Others | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Differences before and after medication | |||

| Significant difference | 14 (70%) | 6 (66.7%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| No difference | 6 (30%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Local adverse reactions after treatment | |||

| Redness | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Swelling | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Itching | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pain | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Remarkably, after the application of the propranolol regimen, 14 out of the 20 volunteers showed a significant reduction in hair loss (p < .05), indicating the potential efficacy of the propranolol treatment (Figure 3B).

Despite the presence of ethanol, menthone, and water in the solvent, which could potentially cause allergic reactions on the scalp (such as redness, swelling, itching, and pain), no such adverse reactions were reported by any of the volunteers during the treatment period. This observation suggests the topical safety of the spray formulation used in our study. Additionally, no instances of peeling or other significant skin issues were noted, further underscoring the tolerability of the treatment among the participants (Table 1).

4. DISCUSSION

The results of our study suggest that topical application of propranolol, by inhibiting the β2AR signaling pathway, may be effective in mitigating hair loss associated with factors such as psychological anxiety, high work pressure, and irregular work and rest patterns.

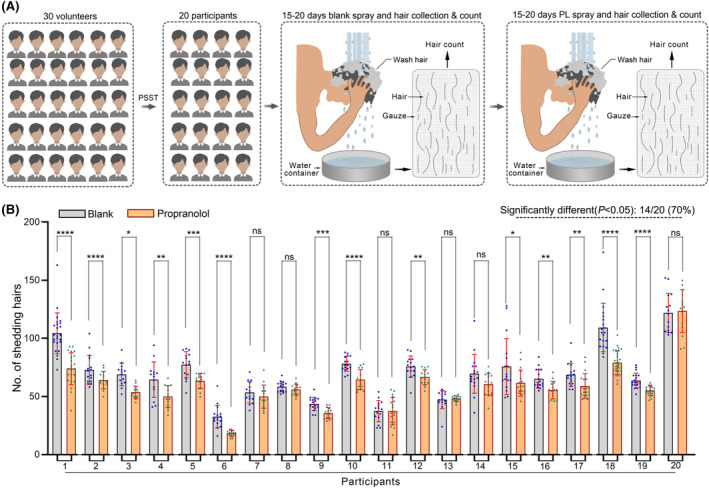

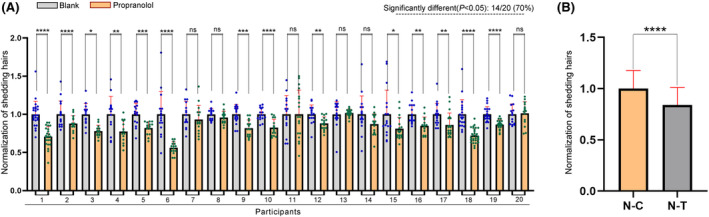

In order to more intuitively judge the effectiveness of propranolol, we normalized the data. Consistent with the previous results, after the application of the propranolol regimen, 14 out of the 20 volunteers showed a significant reduction in hair loss (Figure 4A). At the same time, we used the normalized data of shedding hairs in the control regimen and the propranolol regimen as the overall data, and conducted Student's T‐test. The result demonstrates that topical propranolol can reduce shedding hairs in subjects with symptoms of significantly increased hair loss due to high work pressure, irregular work schedule, or psychological anxiety (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Normalization of shedding hairs. (A) A comparative analysis showed that there was a significant decrease (p < .05) in the number of shed hairs after PP‐HCl application in 14 of the 20 participants. All data are normalized and presented as mean ± SD. (B) A comparative analysis showed that there was a significant decrease (p < .05) in the number of shed hairs after PP‐HCl application. All data are normalized and presented as mean ± SD. ns means p > .05; *p ≤.05; **p ≤.01; ***p ≤.001; ****p ≤.0001.

It is worth noting that during the treatment period, no subject reported local adverse skin reactions such as peeling, itching, and persistent erythema, which may aggravate the original hair loss. Similarly, no serious adverse events such as hospitalization, disability, impact on workability, life‐threatening or death, and congenital malformations occurred during the clinical trial. This further emphasizes the safety and tolerability of the propranolol regimen.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. The absence of a double‐blind, randomized experimental design is a significant limitation. Such a design is essential for eliminating bias and ensuring the reliability of results. Moreover, our study is characterized by a relatively small sample size and a limited pool of volunteers, which may not adequately represent the larger population. These factors could potentially affect the generalizability of our findings.

To address these limitations and strengthen the validity of our conclusions, it is crucial to expand the number of participants and implement a double‐blind, randomized methodology in future studies. This would involve randomly dividing volunteers into two groups. The first group would undergo the current protocol, receiving the placebo (control regimen) treatment initially, followed by the propranolol treatment. Conversely, the second group would receive placebo treatments in both phases. Such a comparative analysis of hair loss before and after treatment in these groups would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the intervention's efficacy, contributing to a more robust and credible body of evidence.

Additionally, our study did not elucidate the molecular mechanism by which propranolol prevents stress‐induced hair loss, necessitating further investigation for validation.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study provides evidence suggesting that the application of a PP‐HCl solution may alleviate stress‐induced alopecia to a certain extent (Figure 4B). This finding adds a new dimension to the understanding of stress‐related hair loss and presents propranolol as a potential therapeutic agent, which is expected to improve the quality of life of those affected by stress‐induced hair loss.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ZJL, XSW, MDZ, BKZ, YSZ designed the study, BKZ, XXL, RSS wrote the manuscript, MDZ, RYT, GFW, YSZ selected the sample and collected data, ZJL, MDZ, BKZ, XJX, made the statistical plan and analyzed the data. All authors reviewed manuscript and agreed to its submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study is supported by GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515140147), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82102526), and Foshan 14th—fifth high‐level key specialty construction project, China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M721522), Technology & Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (JCYJ20210324120007021), Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Neural Cell Reprogramming and Drug Research (ZDSYS20230626091202006).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the participants for supporting this study.

Zhu M, Zheng B, Zhang Y, et al. A single‐center clinical trial evaluating topical propranolol for preventing stress‐induced hair loss. The FASEB Journal. 2024;38:e70191. doi: 10.1096/fj.202401027R

Meidi Zhu, Binkai Zheng, and Yunsong Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Trial registration: A single‐center clinical trial of topical application of propranolol for the prevention of stress or anxiety‐induced hair loss, ChiCTR2300068541. Registered February 22, 2023—Retrospectively registered, https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=178080.

Contributor Information

Xusheng Wang, Email: wangxsh27@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Zhongjie Liu, Email: 13580562690@163.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. Datasets GSE129611 were available on GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital (2022‐KY‐KZ‐229‐02).

REFERENCES

- 1. York J, Nicholson T, Minors P, Duncan DF. Stressful life events and loss of hair among adult women, a case‐control study. Psychol Rep. 1998;82(3 Pt 1):1044‐1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arck PC, Handjiski B, Peters EM, et al. Stress inhibits hair growth in mice by induction of premature catagen development and deleterious perifollicular inflammatory events via neuropeptide substance P‐dependent pathways. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(3):803‐814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ephraim AJ. On sudden or rapid whitening of the hair. AMA Arch Derm. 1959;79(2):228‐236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trüeb RM. Diffuse hair loss. In: Whitting DA, Blume‐Peytavi U, Tosti A, Trüeb RM, eds. Hair Growth and Disorders. Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer; 2008:259‐272. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Navarini AA, Nobbe S, Trüeb RM. Marie Antoinette syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(6):656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arck PC, Handjiski B, Hagen E, Joachim R, Klapp BF, Paus R. Indications for a brain‐hair follicle axis: inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation and up‐regulation of keratinocyte apoptosis in telogen hair follicles by stress and substance P. FASEB J. 2001;15(13):2536‐2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsu Y‐C, Li L, Fuchs E. Emerging interactions between skin stem cells and their niches. Nat Med. 2014;20(8):847‐856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fan SM‐Y, Chang Y‐T, Chen C‐L, et al. External light activates hair follicle stem cells through eyes via an ipRGC–SCN–sympathetic neural pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(29):E6880‐E6889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shwartz Y, Gonzalez‐Celeiro M, Chen CL, et al. Cell types promoting goosebumps form a niche to regulate hair follicle stem cells. Cell. 2020;182(3):578‐593.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu X, Kaindl J, Clark MJ, et al. Binding pathway determines norepinephrine selectivity for the human β(1)AR over β(2)AR. Cell Res. 2021;31(5):569‐579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peng J, Chen H, Zhang B. Nerve–stem cell crosstalk in skin regeneration and diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2022;28(7):583‐595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Al‐Majed AA, Bakheit AHH, Abdel Aziz HA, Alajmi FM, AlRabiah H. Propranolol. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol. 2017;42:287‐338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Srinivasan AV. Propranolol: a 50‐year historical perspective. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2019;22(1):21‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szeleszczuk Ł, Frączkowski D. Propranolol versus other selected drugs in the treatment of various types of anxiety or stress, with particular reference to stage fright and post‐traumatic stress disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17):10099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rehou S, de Brito ML, Auger C, et al. Propranolol normalizes Metabolomic signatures thereby improving outcomes after burn. Ann Surg. 2023;278(4):519‐529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dridi H, Liu Y, Reiken S, et al. Heart failure‐induced cognitive dysfunction is mediated by intracellular Ca(2+) leak through ryanodine receptor type 2. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26(8):1365‐1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu B, Lv X, Chen H, et al. Sensory nerves regulate mesenchymal stromal cell lineage commitment by tuning sympathetic tones. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(7):3483‐3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amnuaikit C, Ikeuchi I, Ogawara K, Higaki K, Kimura T. Skin permeation of propranolol from polymeric film containing terpene enhancers for transdermal use. Int J Pharm. 2005;289(1–2):167‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao K, Singh J. In vitro percutaneous absorption enhancement of propranolol hydrochloride through porcine epidermis by terpenes/ethanol. J Control Release. 1999;62(3):359‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahad A, Al‐Jenoobi FI, Al‐Mohizea AM, Akhtar N, Raish M, Aqil M. Systemic delivery of β‐blockers via transdermal route for hypertension. Saudi Pharm J. 2015;23(6):587‐602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Villanueva C, Albillos A, Genescà J, et al. β blockers to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension (PREDESCI): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10181):1597‐1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lanfranconi S, Scola E, Meessen J, et al. Safety and efficacy of propranolol for treatment of familial cerebral cavernous malformations (Treat_CCM): a randomised, open‐label, blinded‐endpoint, phase 2 pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(1):35‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yan L, Li M, Zhu M, et al. Natural compound Isoliensinine inhibits stress‐induced hair greying by blocking β2‐Adrenoceptor. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2023;2023:7238029. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li X, Shi R, Yan L, et al. Natural product rhynchophylline prevents stress‐induced hair graying by preserving melanocyte stem cells via the β2 adrenergic pathway suppression. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2023;13(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takahashi R, Grzenda A, Allison TF, et al. Defining transcriptional signatures of human hair follicle cell states. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(4):764‐773.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, et al. SWISS‐MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W296‐W303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu Y, Yang X, Gan J, Chen S, Xiao Z‐X, Cao Y. CB‐Dock2: improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W159‐W164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adasme MF, Linnemann KL, Bolz SN, et al. PLIP 2021: expanding the scope of the protein–ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W530‐W534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. Datasets GSE129611 were available on GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital (2022‐KY‐KZ‐229‐02).