Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) regulates mRNA transcription by promoting RNA Pol II elongation. CDK9 is now emerging as a potential therapeutic target for cancer, since its overexpression has been found to correlate with cancer development and worse clinical outcomes. While much work on CDK9 inhibition has focused on hematologic malignancies, the role of this cancer driver in solid tumors is starting to come into focus. Many solid cancers also overexpress CDK9 and depend on its activity to promote downstream oncogenic signaling pathways. In this review, we summarize the latest knowledge of CDK9 biology in solid tumors and the studies of small molecule CDK9 inhibitors. We discuss the results of the latest clinical trials of CDK9 inhibitors in solid tumors, with a focus on key issues to consider for improving the therapeutic impact of this drug class.

Keywords: CDK9, cancer therapeutics, targeted therapy, solid tumors

1. Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are a subfamily of serine-threonine kinases crucial for the regulation of cell cycle progression and transcription. They are classified into two main groups according to their function. CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 govern cell cycle progression whereas CDK7, CDK8, CDK9, CDK12 and CDK13 regulate transcription through RNA polymerase II [1]. CDKs 14–20 are less well-understood but possess diverse functions, including WNT signaling and vesicle transport [1]. CDKs form heterodimers with specific cyclins to perform their physiological function and aberrations in CDK expression, activity, and regulation is known to contribute to cancer development and progression.

Given the regulatory role of CDKs, they are attractive targets for intervention and the first developed inhibitors targeted multiple CDKs at once. Unfortunately, the first generation of CDK inhibitors had mixed success due to their narrow therapeutic windows and dose-limiting toxicities from off-target effects on multiple kinases [2]. Later generations of CDK inhibitors focused on selectively inhibiting individual CDKs, such as the CDK4/6 inhibitors used in the treatment of hormone-positive breast cancer. In this review, we focus on recent developments in our understanding of CDK9 in solid tumors. We discuss the CDK9-targeting drugs that have been developed, with an emphasis on new and recent clinical trials of these drugs.

2. CDK9 structure

CDK9 is broadly expressed in human tissue. It has the typical kinase structure, consisting of an N- and C-terminal lobe, and a short C-terminal kinase extension. The N-terminal lobe contains one α-helix with the highly conserved PITLARE peptide sequence which facilitates the interaction between CDK9 and cyclin T [3]. The ATP binding site is located between the N- and C-terminal lobes, where the adenine moiety of ATP can form hydrogen bonds with the hinge residues Asp104 and Cys106.

CDK9 is expressed as two isoforms that differ by their molecular weight. The short form (CDK9-42) is a 42 kDa protein mainly found in the cytoplasm and the nucleus. The long form (CDK9-55) is a 55 kDa protein with an additional 117 amino acids by the N-terminal and located in the nucleolar region [4]. Both the isoforms are encoded by the same gene but regulated differently. CDK9-42 is more highly expressed in monocytes, HeLa cells, and T-cells whereas the CDK9-55 isoform is present during the regeneration of skeletal muscle [5, 6].

3. CDK9 function in transcription

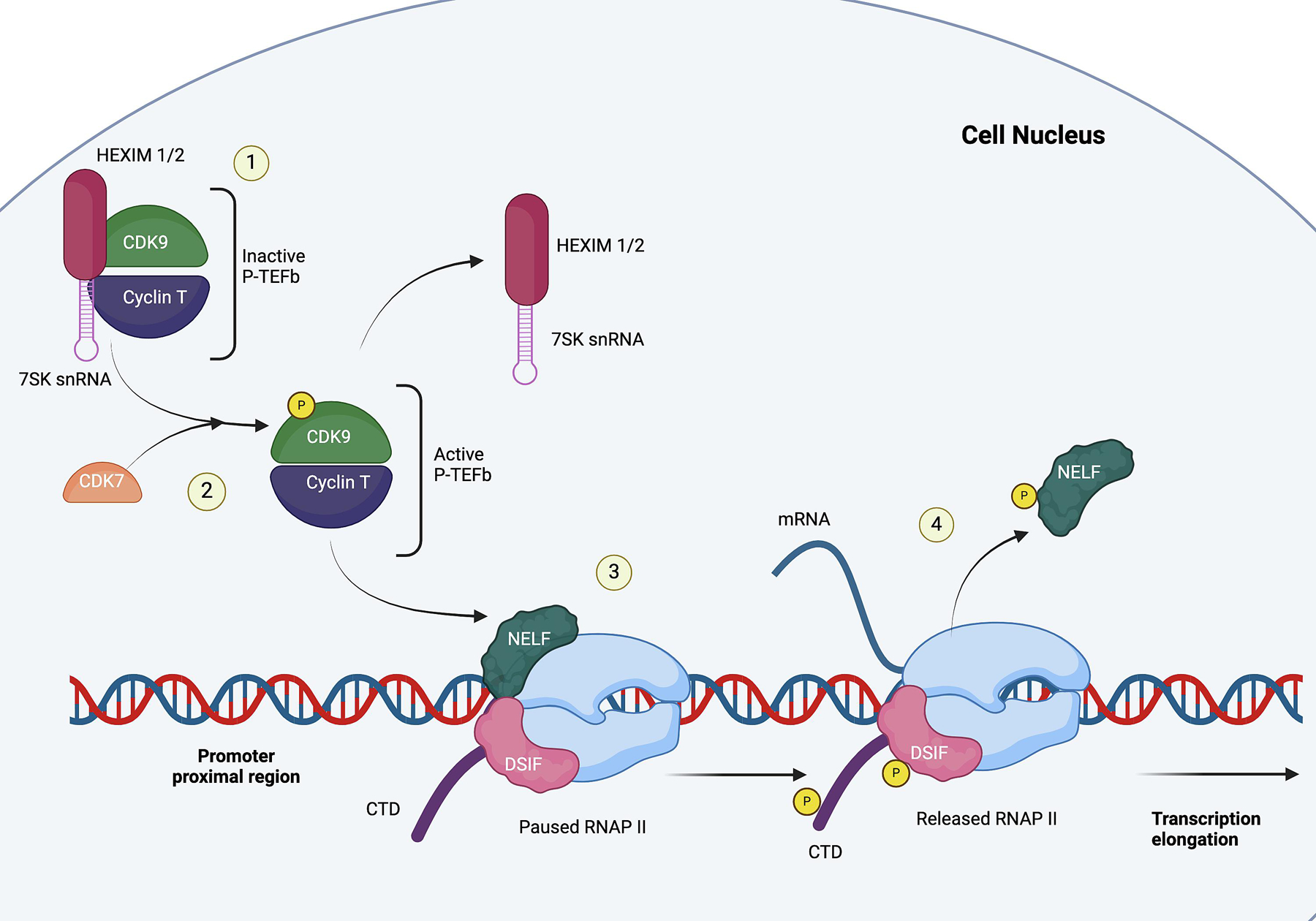

The main function of CDK9 as a transcriptional regulator begins when it binds with cyclin T to form the positive transcription elongation factor β (P-TEFb, Figure 1). After initiation but prior to elongation, RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) is paused downstream of the transcription start site at the early elongation checkpoint (EEC) by negative transcription factors, the DRB-sensitivity inducing factor (DSIF) and negative elongation factor (NELF) [7, 8]. DSIF, comprised of Spt4 and Spt5, will eventually bind to the transcription complex when the Spt5-binding site becomes available [9]. NELF is a four-subunit complex that stops RNAP II movement and forces the active site of RNAP II in a tilted conformation to prevent RNA elongation [9, 10]. The pausing of RNAP II allows for gene-specific regulation, quality control, and 5’ mRNA capping [11].

Figure 1. The function of CDK9.

1) CDK9 forms heterodimers with cyclin T to become P-TEFb. The inactive P-TEFb is bound to HEXIM1/2 and 7SK snRNA; 2) CDK7 phosphorylates CDK9 to release P-TEFb from HEXIM1/2 and 7SK snRNA; 3) RNAP II is paused at the promoter-proximal region. The active P-TEFb phosphorylates NELF, DSIF, and CTD of the paused RNAP II; 4) RNAP II is released and begins transcription elongation.

Transcription elongation occurs when RNAP II is released from the promoter-proximal site by P-TEFb in order for transcription elongation to occur. P-TEFb can be found in three states: 1) active, 2) inactive, or 3) assembled in the active super elongation complex (SEC). At any given time, the majority of P-TEFb will be reversibly bound in an inactive complex with 7SK snRNP, which comprises of 7SK snRNA and hexamethylene bisacetamide-inducible proteins (HEXIM1/2) [12–14]. P-TEFb attaches to the central loop of the hairpin structure between 7SKsnRNA and HEXIM1/2, which then triggers conformational changes in HEXIM1/2 to target the ATP pocket on CDK9 to hinder its kinase activity [14, 15]. In order to activate and release P-TEFb from 7SK snRNP, CDK7 phosphorylates the Thr189 residue of CDK9 [15].

Once activated, P-TEFb phosphorylates Ser2 of RNAP II’s C-terminal domain (CTD), NELF, and DSIF. The phosphorylation of the ATP subunit of DSIF transforms it into a positive transcription factor and prompts the dissociation of NELF from RNAP II [7, 8]. After RNAP II is released, positive transcription factors, such as PAF1C, Pin1, and Tat-SF1, and RNA 3’ end processing factors are recruited to the transcription complex [16], [17]. Subsequently, P-TEFb is then often incorporated into a large complex known as the Super Elongation Complex (SEC) which comprises of multiple transcription factors. SEC then helps increase RNAP II processivity and stimulate mRNA synthesis [13].

4. CDK9 inhibitors in solid tumors

The CDK9 pathway is implicated in tumorigenesis of many solid malignancies, including pancreatic, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer. Its inhibition has been demonstrated to decrease cell proliferation, induce apoptosis, and impede tumor growth in multiple cancer cell lines and xenografts [18]. Despite its indispensable role in global transcription, studies have revealed that CDK9 inhibition predominantly affects genes characterized by high transcription rates and short mRNA half-lives [19]. P-TEFb promotes the transcription of multiple signal-responsive genes that are involved in cell proliferation and development, such as MYC, NF-kB, and Mcl-1 [19–21]. Consequently, acute inhibition of CDK9 results in a temporary depletion of short-lived proteins that drive tumor development and progression.

Oncogenic mutations cause changes in signaling events that affect the overall transcriptional and metabolic needs of cancer cells. These mutations create a “transcriptionally addicted” state where the cancer cells become dependent on the activity of driver mutations for sustained tumor growth and survival [22, 23]. MYC is a family of proto-oncogenes that are the most commonly deregulated and amplified genes in cancer [19]. In tumor cells, MYC accumulates in the promoter region of active genes to recruit P-TEFb to further augment the transcription of MYC target genes. These tumors rely on sustained MYC overexpression for aberrant growth, but once MYC is removed, tumor growth slows substantially [21].

While MYC seems to be a promising target, different methods to directly inhibit MYC function have met with varying degrees of success. The strategies include inhibition of MYC transcription by bromodomain inhibitors, inhibition of dimerization by MYC and its protein binding partner MAX, and targeting expression of MYC-regulated genes [24–26]. But MYC and other oncogenic transcription factors are largely considered “undruggable” due to the lack of a known ligand pocket, therefore approaches have shifted to target proteins that can regulate the stability or activation of these factors. Preclinical studies in various cancer types have prioritized CDK9 for its regulatory role in the transcription of oncogenes such as MYC and anti-apoptotic proteins such as Mcl-1.

Additionally, CDK9 inhibition can paradoxically cause reactivation and upregulation of tumor suppressor genes [20]. CDK9 promotes gene silencing by phosphorylating BRG1, an ATP-dependent helicase that utilizes ATP hydrolysis to regulate chromatin structure [27]. BRG1 is a member of the SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complex, therefore the CDK9-mediated phosphorylation prevents the recruitment of BRG1 to chromatin. CDK9 inhibition allows for chromatin relaxation and activation of the epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes [20]. Through this indirect mechanism of impacting chromatin modification, CDK9 inhibition was shown to upregulate tumor suppressor genes such as SYNE1 and MGMT, and also upregulate endogenous retroviral (ERV) elements, leading to enhanced innate immune response.

CDK9 inhibitors have been well-studied in hematologic malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma [18, 28]. Given the heterogeneity of solid tumors, there is less known about the role of CDK9. The following sections will focus on various mechanisms by which CDK9 inhibition exerts its antitumoral effects in solid malignancies.

4.1. Pancreatic Cancer

CDK9 expression is significantly higher in pancreatic cancer and associated with shortened survival [29]. Patients with higher tumor CDK9 expression had significantly shorter overall survival (OS), even in well-differentiated tumors. This suggests that CDK9 is a poor prognostic indicator [29].

The key genetic driver of pancreatic cancer progression and proliferation is the dysfunctional activation of the KRAS oncogene [30]. RAS transformation requires MYC overexpression and in return, mutationally activated KRAS promotes MYC expression to stimulate gene transcription and maintain MYC protein stability [19]. Studies have shown that KRAS-mutant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) tumors involve the ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of the MYC residue Ser62 to increase MYC protein stability [31, 32]. The pSer62 then assists with GSK-3b phosphorylation of MYC at Thr58 residue. Conversely, dephosphorylation of Ser62 leads to MYC ubiquination and degradation by the E3 ligase [33]. Therefore, CDK9 inhibition might suppress pancreatic cancer growth and survival via suppression of MYC.

CDK9 also has the potential to sensitize pancreatic cancer cells to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing (TRAIL)- mediated apoptosis by downregulating Mcl-1, cFlipS and cFlipR [34]. The TRAIL ligand serves as an extracellular signal to selectively trigger apoptosis in cancer cells by binding to the membrane-bound death receptors 4/5 (DR4 and DR5). DR4 and DR5 then transmit signals through a cytoplasmic “death domain” motif to activate the pro-apoptotic death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) and the downstream apoptotic cascade [35–37]. Unfortunately, most TRAIL-receptor agonists (TRAs) have had limited success because established cancer cell lines were either intrinsically resistant or could easily develop resistance.

High levels of Mcl-1 contribute to TRAIL resistance by interacting with Bid to inhibit mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization [38]. cFlipS and cFlipR also add to resistance as they prevent apoptosis by competing with procaspase 8 for binding to the FAS-associated death domain (FADD), thus stopping its conversion to an active caspase [38]. CDK9 inhibition was able to suppress Mcl-1 and cFLIP to sensitize previously resistant cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. In pancreatic cancer cell lines, treatment with atuveciclib (previously known as BAY1143572) reduced cell viability by downregulating the transcription of Mcl-1 through reduced RNAP II phosphorylation [34]. Interestingly, the combined treatment of atuveciclib and izTRAIL led to an even larger decrease in cell viability and colony growth. Proteomics analysis revealed Mcl-1 suppression and almost complete loss of cFLIP protein expression with accompanied rise in activated caspase 8, indicating active apoptosis [34].

4.2. Colorectal Cancer

CDK9 is highly expressed in CRC tissues, but its role in prognosis remains controversial. Elevated CDK9 expression was associated with improved overall survival in females, right-sided colon cancers, or patients with T3/T4 tumors [39]. Conversely, CDK9 correlated with shortened survival in patients with microsatellite-stable (MSS), late-stage CRC [40].

Similar to their effect in pancreatic cancer cells, CDK9 inhibition in CRC allowed for TRAIL sensitization. Treatment with the CDK9 inhibitor, dinaciclib, in CRC cell lines demonstrated decreased cell viability in a time- and dose-dependent manner. There was a further substantial reduction in cell viability when CRC TRAIL-resistant cell lines were incubated with dinaciclib prior to izTRAIL treatment [39]. This was driven by a decrease in proteins which contribute to TRAIL resistance, such as Mcl-1 and cFlipR. Additionally, the CRC cell lines revealed increased cleavage of pro-caspase-8, Bid, pro-caspase-9, and pro-caspase-3, suggesting enhanced TRAIL-driven apoptosis [39].

There are pre-clinical studies that suggest CDK9 inhibitors may also sensitize MSS CRC to PD-L1 inhibitors. The efficacy of PD-L1 inhibitors hinges on both the PD-L1 expression in the tumor and the amount of immune effector cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) [40]. Studies indicate that CDK9 can promote the growth and differentiation of immune cells and their chemokine expression, thus impacting the migration of T-cells into the TME [41, 42]. Consequently, CDK9 is believed to be related with genes involved in immune cell movement and exhaustion in CRC. In MSS CRC, CDK9 was found to have a negative correlation with the infiltration of CD8+ T-cells. Flow cytometry confirmed there were fewer CD8+ T-cells in the TME in patients with higher CDK9 expression [40]. Conversely, higher CDK9 expression positively correlated with the expression proteins involved in lymphocyte migration, such as the C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), C-C motif chemokine ligand 21 (CCL21), and atypical chemokine receptor 3 (ACKR3). In particular, CXCL12 has been shown to decrease the number of NK cells and CD8+ T-cells in the TME [43]. Theoretically, CDK9 inhibition has the ability to fuel immune cell infiltration and augment PD-L1 efficacy in MSS CRC.

Additionally, CDK9 inhibitors have been shown to reactivate p53 in CRC. The loss of p53 is common and can occur through mutations in TP53 gene or through inhibition of the wild-type p53 protein [44]. PPP1R13L encodes for the inhibitor of the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 (iASPP), which negatively regulates p53 activity. iASPP knockdown in CRC HCT116 cell lines led to recovery of p53-dependent cell death. CDK9 inhibitors promote this pro-apoptotic phenotype by downregulating the transcription of iASPP [45].

4.3. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

CDK9 is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), however there is no clear correlation between prognosis and CDK9 expression. HCC is a genetically heterogenous disease, making successful targeted therapy difficult. In HCC, genomic studies have found B-catenin mutations, TP53 inactivation, and MYC amplifications as common occurrences [46].

CDK9 inhibitors have been shown to promote mitophagy in HCC cell lines, resulting in reduced tumor growth and metastasis [47]. Mitophagy, a subtype of autophagy, is responsible for eliminating dysfunctional mitochondria, which is critical for the proliferation of HCC cells due to the abundance of mitochondria in hepatocytes. Mitophagy occurs through two pathways, one which is activated by the HIF1A/HIF-1α (hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha) and the other by the PINK1 (PTEN induced kinase 1)-PRKN pathway [48].

The PINK1-PRKN pathway is initiated by membrane depolarization, which recruits PINK1 and the E3 ubiquitin kinase PRKN to the mitochondria. PRKN then ubiquinates the mitochondrial membrane proteins to initiate mitophagy [49]. CDK9 inhibition disrupts the PINK1-PRKN pathway by downregulating PINK1 and PRKN protein expression. There is concurrent increase in PINK1 degradation through inactivation of the SIRT1-FOXO3-BNIP3 pathway. SIRT1 is a NAD-dependent deacetylase that regulates autophagy to maintain mitochondrial function [50]. CDK9 inhibitors were observed to decrease SIRT1 phosphorylation and increase FOXO3 protein degradation, resulting in the transcriptional repression of BNIP3 and impairment of the BNIP3-mediated PINK1 stability [47].

HCC patients with poor outcomes were frequently found to have an elevated expression of Dickkopf-1 (DDK1). DDK1 inhibits the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, but the true mechanism and its role in tumorigenesis is not well understood [51]. In HCC, it appears to promote inflammation, invasion, and migration through TGF-β1 by remodeling the tumor microenvironment [51]. Treatment of HCC cell lines with either a CDK9 inhibitor or degrader revealed downregulation of DKK1 transcription and decreased DKK1 protein levels[52].

4.4. Esophageal Cancer

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common histologic subtype of esophageal cancer. The expression rate of CDK9 remains unclear in esophageal SCC, but CDK9 was more highly expressed in esophageal SCC cell lines than in normal esophageal epithelial cells [53]. It is also well-known that anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Mcl-1, are frequently overexpressed in esophageal SCC.

SNS-032, a CDK7/CDK9 inhibitor, led to a significant reduction in esophageal SCC cell proliferation and triggered apoptosis in vitro and in mouse xenograft models. It lowered the levels of phosphorylated RNAP II, pSer2, and pSer5, but not the total levels of RNAP II, implying that its primary effect was on transcription rather than degradation [53]. Furthermore, SNS-032 demonstrated a synergistic effect when combined with cisplatin, the first-line chemotherapy for esophageal SCC. CDK9 inhibition enhanced chemotherapy-driven apoptosis as evidenced through increased cleaved PARP and caspase-3 activation. Mcl-1 protein levels were much lower in the CDK9 and cisplatin-treated cell lines than with either agent alone [53].

Esophageal adenocarcinoma

CDK9 is overexpressed in esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) compared to matched tissue samples of normal esophageal epithelial cells and Barrett’s esophagus [54]. Staining of tissue specimens revealed strong expression of CDK9 in more than 90% of invasive adenocarcinoma cells while there was minimal staining in the stromal cells. In a similar vein, CDK9 expression in the lower proliferative zone of Barrett’s esophagus was significantly higher than in the upper half [54].

Targeted therapy has had limited success in esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) due to high intratumoral heterogeneity along with low frequency and of actionable mutations such as HER2 amplification (15%), EGFR amplification (20%), EGFR activating mutations (0–12%), and c-MET amplification (2–10%) [55–58]. Currently no targeted agent has shown a significant benefit when used in combination with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy or chemoradiation [59]. Interestingly, doublet therapy with atuveciclib and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) demonstrated synergistic suppression of tumor growth and Mcl-1 downregulation both in vitro and xenograft models of EAC. Atuveciclib alone was able to reduce the EAC xenograft growth in a dose-dependent manner. The combination of CDK9 inhibitors and 5-FU induced more apoptosis in EAC cell lines than either agent alone [59]. Reverse phase protein array (RPPA) analysis of EAC lines revealed downregulation of Mcl-1 and upregulation of FOX-M1 and GATA3, which are inducers of DNA damage repair and epithelial differentiation. CDK9 inhibitors were also found to potentiate and sensitize EAC xenografts to radiation therapy [60].

4.5. Lung Cancer

Non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) are largely driven by mutations in the KRAS and EGFR oncogenes, however patients treated with EGFR inhibitors may eventually develop resistance. Studies have shown that KRAS and EGFR-mutant NSCLC are sensitive to CDK9 inhibitors, with the potential for CDK9 inhibitors to overcome drug resistance [61].

After treatment with CDK9 inhibitors, there was a noted decrease in cell viability of NSCLC cell lines driven largely by lower rates of RNAP II Ser2 phosphorylation. Accordingly, there was a reduction in Mcl-1 as well as embryonic stem-cell transcription factors SOX2 and SOX9 [62]. When NSCLC cell lines were treated with a combination of BRD4 inhibitor and CDK9 inhibitor, a further reduction in cell viability was observed. Interestingly, CDK9 inhibitors were also shown to overcome EGFR-resistance and KRAS-resistance. Both Osimertinib-resistant and sotorasib-resistant cell lines had decreased cell growth and viability when treated with CDK9 inhibitors. This same effect was seen in Osimertinib-resistant organoids treated with CDK9 inhibitors [62]. Although the IC50 was higher in the resistant cells than the naïve cell lines, this is promising for heavily treated patients with drug resistance.

CDK9 is also reported to mediate TNF-α -induced MMP-9 transcription, thereby stimulating tumor invasion and metastasis in NSCLC [63]. TNF-α activates MMP-9, which in turn promotes malignant cell migration by degrading the basement membrane [64]. MMP-9 also supports tumor angiogenesis by releasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and remodeling surrounding vascular structures [65]. In the NSCLC cell line A549, TNF-α stimulated the transcription of the MMP-promoter by facilitating the formation of P-TEFb to bind to the MMP-9 gene [63]. CDK9 knockdown decreased the TNF-α-dependent increase in MMP-9 transcription and activity in A549 cells.

4.6. Breast Cancer

ER+/HER2-

The current standard of care for hormone-positive/HER2-negative advanced breast cancer is a combination of hormone therapy and a CDK4/6 inhibitor. However, patients frequently progress and eventually become resistant. The triplet combination of CDK9 inhibitors, the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib, and the estrogen receptor degrader fulvestrant showed a synergistic effect in patient-derived xenograft model of an ER+ metastatic breast cancer that had progressed on letrozole and palbociclib [66]. In comparison, there was minimal effect with CDK9 monotherapy or palbociclib and fulvestrant dual therapy. The triplet therapy significantly downregulated known CDK9 target genes, such as MYC, MYP, and Mcl-1. Interestingly, the palbociclib-resistant cell lines showed increased sensitivity compared with the palbociclib-sensitive lines [66]. This may be due to an increased reliance on CDK9 activity that accompanies palbociclib resistance.

CDK9 inhibition also decreases MYB, a transcription factor that is highly expressed in estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer and serves as a direct target of estrogen receptor (ER) signaling [67]. It is primarily involved in the proliferation of breast cancer cells and promotion of metastasis through regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [68, 69]. As it is a transcription factor, MYB is difficult to directly inhibit. The expression of MYB is regulated by a transcriptional elongation block in the first intron, but estrogen-stimulated ER can bind in the SL-dT region to directly recruit P-TEFb and increase RNAP II phosphorylation at Ser5 [70]. CDK9 inhibitors have been shown to inhibit MYB expression by suppressing the transcription elongation of SL-dt, leading to selective apoptosis of ER+/MYB+ breast cancer cells [67].

Triple Negative Breast Cancer

Triple negative breast cancers (TNBC) are a group of tumors with variable actionable drivers, but targeted therapy has yet to become standard-of-care due to the heterogenous nature of the disease. However, targeting transcriptional CDKs is potential option as TNBC have the features of transcriptionally addicted tumors [71]. CDK9 is overexpressed in TNBC and associated with poorer prognosis [72].

Pre-clinical studies with CDK9 inhibitors in TNBC cell lines demonstrated a significant reduction in cell proliferation. Evidence has shown that metastasis in solid tumors, including TNBC, are often promoted by a small subset of cells called cancer stem cells (CSCs) [73, 74]. These pluripotent cells in TNBC are identified by expression of their cell surface markers, such as high CD44 and low CD24 [75]. The CD44/CD24 cells are more likely to undergo EMT and increase the possibility of metastasis. Breast cancer CSCs are maintained by the MYC and Mcl-1 oncogenes, which also help drive the CSCs’ resistance to chemotherapy [74]. Treatment with CDK9 inhibitors resulted in decreased phosphorylation of RNAP II at Ser2, leading to a decrease in the expression of Mcl-l, MYC, CSC markers (CD44 and CD24), and EMT markers [76].

EGFR is another potential target in TNBC, as EGFR amplification has been reported in a significant number of TNBC cases and is associated with decreased overall survival [77, 78]. But clinical trials with EGFR inhibitors have failed in TNBC patients despite adequate EGFR suppression [79]. It is thought that EGFR inhibitors are ineffective in TNBC due to a bypass EGFR-related signaling pathway and the nuclear translocation of EGFR which protects it from TKIs that are effective only on the cell membrane surface [80]. Inhibition through CDK9 in xenograft models led to G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, but treatment with a dual CDK7/CDK9 inhibitor and EGFR-TKI in EGFR-mutant TNBC cell lines demonstrated further synergistic effect [79, 81].

4.7. Prostate Cancer

While most prostate cancers are initially dependent on androgen signaling, prostate cancer can progress to a hormone-independent state known as castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Androgen receptors (AR) are still highly expressed in CRPC, and AR re-activation is an ongoing challenge as patients no longer respond to standard androgen-deprivation therapies (ADTs) [82, 83]. ADT resistance can occur through multiple mechanisms, including AR amplification, AR mutations, mutations in coactivators or corepressors, androgen-independent AR activation, ectopic androgen production, and AR variants [84, 85].

AR contains at least 18 phosphorylation sites which regulate its activation and transcriptional activity. Ser81, the most androgen-responsive site, can be phosphorylated by CDK1, CDK5, and CDK9, and is correlated with AR-target gene induction [86]. The lack of AR phosphorylation at Ser81 leads to nuclear export of AR, ubiquitination, and proteasomal degradation. Treatment of prostate cancer cell lines with CDK9 inhibitors demonstrated reductions in Ser81 phosphorylation, AR transcription, and ultimately decreased cell viability [87, 88].

Alternative splice variants of AR (AR-Vs) do not have a ligand-binding domain (LBD), leading to constitutively active AR and eventual ADT resistance. AR-V7 is the most common AR-V found in patients with CRPC [89, 90]. These tumors become dependent on AR-V7, normal AR, and oncogenic AR-driven gene expression proteins [82]. Unfortunately, as AR-Vs lack the LBD, they are mostly unstructured proteins and considered to be “undruggable” [91]. CDK9 inhibition with KB-0742 demonstrated significant reduction of downstream phosphorylation of RNA Pol II at Ser5 which decreased transcription of AR-V7 in the CRPC 22Rv1 cell line. Furthermore, KB-0742 demonstrated tumor reduction in 22Rv1 human prostate cancer cell line-derived xenografts [82].

4.8. Ovarian Cancer

CDK9 exhibits notably high expression rates in ovarian cancer, particularly in metastatic and recurrent cases. It correlates with poor prognosis and reduced disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) [21]. In normal ovarian tissues, CDK9 staining is weak, but there is increasing intensity in early stage to late-stage ovarian cancer tissues [92]. Similarly, IHC staining in matched primary, metastatic, and recurrent specimens from ovarian cancer patients revealed that CDK9 expression was lower in primary ovarian cancers in comparison to the patient-paired metastatic and recurrent samples [93]. There was no correlation between CDK9 and the stage, grade, presence of ascites, or histology.

In pre-clinical studies, CDK9 knockdown inhibited the proliferation of ovarian cancer SKOV3 and OVCAR8 cell lines. The loss of CDK9 expression led to decreased levels of phosphorylated Ser2 and Ser5 of RNAP II and Mcl-1, but increased presence of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax. The same dose-dependent results were seen with treatment from the CDK9 inhibitor LDC067. CDK9 inhibition was able to suppress the clonogenicity, colony growth and cell migration in vitro in ovarian cancer cells [93].

Moreover, CKD9 inhibitors can potentially augment the role of PARP inhibitors in BRCA wildtype ovarian cancers. Currently PARP inhibitors are FDA-approved for ovarian cancer patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations or other homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene deficiencies. However, PARP inhibitors are not extensively used as only 50% of ovarian cancers are HRR deficient [94]. PARP is a vital enzyme that repairs DNA single-stand breaks (SSBs) by facilitating the recruitment of HRR enzyme to the damaged areas [95]. By inhibiting PARP, the accumulation of DNA SSBs would lead to HR-deficient cell death. BRCA1/2 is involved in the initiation of HRR, therefore mutations in BRCA1/2 genes will also lead to HR-deficient cell death. Studies have shown that CDK9 is co-expressed with BRCA1 in ovarian cancer and facilitates HRR by recruiting BRCA1 to the DNA SSBs [92]. BRCA1 wild-type ovarian cancer cell lines all had high expression of CDK9. Meanwhile, cell lines harboring BRCA1 methylation or BRCA2 deficiency had concordantly decreased CDK9 expression [92].

CDKI-73, a CDK9 inhibitor, caused a dose- and time-dependent downregulation of BRCA1 expression. Single-agent treatment with either olaparib or CDKI-73 resulted in modest inhibitory effects on cell proliferation. However, concomitant administration of CDK9 inhibitor and olaparib led to synergistic decrease in cell viability of ovarian BRCA wild-type cell lines [92].

4.9. Endometrial Cancer

CDK9 expression is significantly higher in endometrial cancer in comparison to endometrial hyperplasia, or normal endometrial tissue [96]. Moreover, CDK9 expression in metastatic or recurrent endometrial cancer was markedly higher than in primary endometrial cancer tissue [97]. There was no correlation to pathological stage or histologic subtype, but there was an association with lymph node metastasis and histologic grade. Patients exhibiting higher CDK9 expression levels experienced significantly shorter PFS and OS, indicating that CDK9 is a poor prognostic indicator [96, 97].

CDK9 has a pivotal role in the progression of endometrial cancer. Treatment of the cervical cell lines with the CDK9 inhibitor LCD067 resulted in decreased Mcl-1 expression alongside an increase in the pro-apoptotic proteins cleaved PARP and Bax [97]. Moreover, CKD9 inhibition led to a dose- and time-dependent reduction of endometrial cancer cell migration, colony formation, and colony size.

4.10. Cervical Cancer

CDK9 expression is significantly increased in cervical cancer when compared to normal cervical tissue, and is associated with a poorer prognosis. CDK9 upregulation was also noted to correlate with lymph node metastases, pathological grade, tumor size, and deep-stromal invasion [98].

Cervical cancer xenografts with CDK9 knockdown demonstrated drastically reduced growth and migration. These CDK9-silenced cells had significantly lower levels of AKT2 protein expression which then increased p53 protein expression, suggesting that CDK9 serves as a proto-oncogene through the AKT2/p53 pathway [98]. Additionally, treatment with the CDK9 inhibitor enitociclib (previously known as VIP152/BAY1251152) and cisplatin synergistically enhanced the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to cisplatin [99].

4.11. Sarcoma

CDK9 exhibits elevated expression levels in both synovial sarcoma and osteosarcoma, correlating with unfavorable prognosis in both malignancies. There was no correlation between CDK9 expression and other clinicopathological features, such as age, gender, and tumor location, for either sarcoma subtype [100, 101]. In synovial sarcoma, patients with high CDK9 expression demonstrated significantly worse outcomes than patients with low CDK9 expression [100]. Similarly in osteosarcoma, CDK9 was overexpressed in patients with metastatic disease and associated with shorter disease-free progression. It was determined to be an independent prognostic indicator for survival and response to therapy, as patients with higher CDK9 expression showed lower rates of tumor necrosis after neoadjuvant therapy [101].

4.12. Melanoma

Cutaneous melanoma

Chromatin dysregulation is common in melanoma, resulting in multiple epigenetic changes that promote resistance [102, 103]. Previous studies have indicated that CDK9 inhibition facilitates chromatin relaxation and the reactivation of epigenetically silenced genes across multiple cancer cell lines [20]. While CDK9 expression alone has not shown a direct correlation with overall survival in melanoma patients, those with elevated levels of both BRD4 and CDK9 exhibit significantly poorer [104]. Given the proximity of BRD4 and CDK9 in the P-TEFb complex, the combination of BET inhibitors and CDK9 inhibitors demonstrated synergistic effect in reducing the growth of melanoma in vitro and in vivo. Treatment with the BET inhibitor IBET151 and CDKI-73 induced caspase-dependent apoptosis in melanoma cells along with an associated decrease in Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, and Mcl-1 proteins [104].

Uveal melanoma

Uveal melanoma (UM) is considered to be different from cutaneous melanoma, as it does not typically have BRAF or KRAS mutations nor does it respond well to immune checkpoint inhibitors [105, 106]. Instead, UM is driven by the GNAQ/GNA11-Yes-associated protein (YAP) cascade when cells acquire a gain of function mutation in GNAQ or GNA11. These mutations, which can be found in 80% of patients with UM, then lead to constitutive activation of the protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway [105]. Unfortunately, combination treatment with PKC and MEK inhibitors have only shown modest benefit in UM [107]. However, CDK9 inhibition was found to significantly decrease the transcription of YAP and its downstream targets, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer (CYR61). The UM cell lines and xenografts treated with SNS-032 demonstrated reduced cell viability, colony formation, and invasiveness of UM cells [105]. While the exact mechanism in UM cells is unclear, CDK9 inhibition is thought to interfere with YAP signaling. Importantly, YAP signaling suppression by CDK9 inhibitors has been demonstrated in other tumor types [108].

4.13. Glioblastoma

In gliobastoma cancer stem cell models, CDK9 has been found to interact with Recombining binding protein suppressor of hairless (RBPJ), a transcriptional mediator of NOTCH activity [109], to promote many oncogenic transcriptional pathways. This interaction leaves glioblastoma vulnerable to targeting of CDK9. Several CDK9 inhibitors (dinaciclib, SNS032, AZD4573, NVP2, and JSH150) have been found to potently inhibit the growth and survival of glioblastoma preclinical models [110, 111]. Importantly, both temozolomide-sensitive and temozolomide-resistant models were found to be sensitive to CDK9 inhibitors.

Zotiraciclib (formerly known as TG02) was found to induce apoptosis and synergized with temozolomide to treat glioblastoma in preclinical models [112]. Interestingly, zotiraciclib suppressed glycolysis and caused mitochondrial dysfunction, which potentially explains its cytotoxicity against glioblastoma. Zotiraciclib has been studied in two glioblastoma clinical trials (NCT03224104, NCT02942264) and there is an ongoing trial studying zotiraciclib in glioblastoma with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations (NCT05588141) [113, 114]. Thus far, neutropenia is the common dose limiting toxicity, making it difficult to safely combine with cytotoxic agents such as temozolomide.

5. CDK9 inhibitors

Since aberrant expression of CDK9 is present in various malignancies, it has become an attractive therapeutic target. However, early attempts at a pan-CDK inhibitor had poor selectively and high toxicity. The first CDK inhibitor developed, flavopiridol, had efficacy against CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, CDK6, and CDK9. While it showed promising pre-clinical results against advanced hematologic and solid malignancies, its progress has been hampered by toxicity from off target kinases and high risk of tumor lysis syndrome [115–117]. The primary dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) included neutropenia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Dinaciclib, another early generation pan-CDK inhibitor, had a similar side effect profile with mostly grade 1 or 2 gastrointestinal symptoms. The most frequent grade 3/4 AEs were neutropenia and leukopenia [118].

Over the years, additional selective CDK9 inhibitors have been identified (Table 1) and progressed to clinical trials (Table 2). However, the majority of the agents are still under development or pre-clinical investigation, making it difficult to fully gauge their toxicities. In a phase 1 dose-escalation study, enitociclib (VIP152) was well-tolerated with primarily grade 1 or 2 nausea and vomiting. The most frequent grade 3 or 4 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were neutropenia (22%), anemia (11%), and abdominal pain (8%), with only neutropenia associated with the dosage [119]. Fadraciclib, a second generation dual CDK2 and CDK9 inhibitor, demonstrated comparable toxicity profile with nausea, vomiting, and thrombocytopenia as the most common. Interestingly, the main dose-limiting toxicity was grade 3 hyperglycemia [118, 120]

Table 1.

Overview of CDK9 inhibitors

| CDK9 Inhibitor | Target | Mechanism of Action | Pre-clinical Effects | Cancer Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

CAN508 [54] |

CDK9 IC50 = 350nM |

|

|

EAC |

LDC067 [47, 124] |

CDK9 IC50 = 44nM |

|

|

HCC, CRC, NSCLC, endometrial, ovarian |

SNS-032 [29] [125] |

CDK 2, 7, and 9 IC50 = 38, 62, and 4nM |

|

|

EAC, NSCLC, pancreatic |

THAL-SNS-032 [126] |

CDK9 |

|

|

ER+ breast cancer; HCC |

NVP-2 [126] |

CDK9 IC50 < 0.5nM |

|

|

ER+ breast cancer; HCC |

MC180295 [127] |

CDK9 IC50 = 5nM |

|

|

CRC, melanoma, prostate |

Atuveciclib (BAY1143572) [83] |

CDK9 IC50 = 13nM |

|

|

EAC, HCC, TNBC, prostate |

Enitociclib (VIP152/BAY1251152) [119] |

CDK9 IC50 = 3nM |

|

|

HCC, ovarian |

Z11 [62] |

CDK9 IC50 = 3.20nM |

|

|

NSCLC |

21e [132] |

CDK9 IC50 = 11nM |

|

|

NSCLC |

KB-0742 [134] |

CDK9 IC50 = 6nM |

|

|

CRPC, TNBC |

CDDD11-8 [18, 71] |

CDK9 FLT-ITD IC50 = 8 and 13nM |

|

|

TNBC ESCC |

AZD4573 [28, 61] |

CDK9 IC50 < 4nM |

|

|

HCC, NSCLC, ER+ breast cancer |

LZT-106 [135] |

CDK9 IC50 = 30nM |

|

|

CRC |

Fadriciclib (CYC065) [136] |

CDK2 and 9 IC50 = 5nM and 26nM |

|

|

TNBC, neuroblastoma |

CDKI-73 [92] |

CDK1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 9 IC50 = 8.17, 3.27, 8.18, 37.68, 134.26, and 5.78 |

|

|

Ovarian, CRC |

|

XPW1 [139] |

CDK9 |

|

|

ccRCC |

JSH-150 [140] |

CDK9 IC50 = 1nM |

|

|

CRC, GIST, melanoma |

LY2857785 [141] |

CDK7, 8, and 9 IC50 = 246, 16, and 11nM |

|

|

Sarcoma, large cell lung cancer, melanoma |

FIT-039 [142] |

CDK9 IC50 = 5.8μM |

|

|

Cervical |

PHA-767491 [146] |

CDK7 and 9 IC50 = 10 and 34nM |

|

|

TNBC, HCC, glioblastoma |

LL-K9-3 [147] |

CDK9 and cyclin T |

|

|

CRPC |

TP-1287 |

CDK9 |

|

|

Ewing sarcoma |

CLZX-205 [149] |

CDK9 IC50 = 2.9nM |

|

|

CRC |

Zotiraciclib [150] |

CDK9 IC50 = 3nM |

|

|

Glioblastoma |

Table 2.

Ongoing trials with CDK9 inhibitors in solid malignancies

| CDK9 inhibitor | Trial | Phase | Cancer Type | Primary Endpoints | Status | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fadriciclib (CYC065) |

NCT04983810 | I/II | Advanced solid tumor refractory to standard therapy | MTD, ORR | Active |

|

| NCT02552953 | I | Metastatic or unresectable solid tumors | MTD, RP2D | Complete d |

|

|

| KB-0742 | NCT04718675 | I/II | Relapsed or refractory solid tumors with MYC amplification | MTD, DLT, RP2D, AE | Active |

|

| TP-1287 | NCT03604783 | I | Advanced solid tumors refractory to standard therapy; Ewing sarcoma, liposarcoma, synovial sarcoma | MTD, DLT, RP2D | Completed |

|

| PRT2527 | NCT05159518 | I | CPRC; sarcomas; advanced NSCLC; hormone receptor-positive/HE R2- breast cancer; solid tumors with MYC amplification | MTD, DLT, RP2D | Completed |

|

| Atuveciclib (BAY1143572) |

NCT01938638 | I | Advanced solid tumors refractory to standard therapy | MTD | Terminated by sponsor |

|

| Enitociclib (VIP152/BAY1251152) |

NCT02635672 | I | Advanced solid tumors with MYC amplification | MTD, DLT, RP2D | Completed |

|

| Zotiraciclib (TG02) |

NCT05588141 | I/II | Recurrent high-grade gliomas with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations | RP2D, PFS | Active |

|

| NCT03224104 | Ib | Anaplastic astrocytoma or glioblastoma | MTD, PFS | Completed |

|

|

| NCT02942264 | I/II | Anaplastic astrocytoma or glioblastoma | MTD, PFS | Completed |

|

CDK9 inhibitors carry similar hematologic toxicities as compared to other selective CDK inhibitors, such as CDK4/6 and CDK7 inhibitors. In multiple large scale phase III clinical trials for breast cancer, the most common AEs of any grade for CDK4/6 inhibitors were neutropenia and leukopenia [121]. In a phase 1 trial, the use of CDK7 inhibitors can result in anemia and decreased platelet count [122]. It is not surprising that CDK inhibitors demonstrate overlapping hematologic toxicities as CDK inhibitors decrease the proliferation of hematopoietic cells by inducing cell-cycle arrest. Overall, CDK9 inhibitors have a manageable safety prolife, however their suppressive effect on the bone marrow may pose challenges when used in combination with other cytotoxic treatments.

Here we highlight the CDK9 inhibitors and degraders which have shown efficacy in solid malignancies, along with recent and current ongoing trials. The structure and key biological properties of each compound are summarized in Table 1, while the clinical trials are summarized in Table 2.

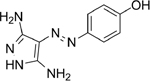

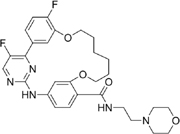

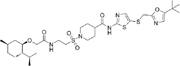

5.1. CAN508

CAN508 is an arylazopyrazole-based CDK9 inhibitor (IC50 = 350nM) with 38-fold selectivity for CDK9 [54]. The diaminopyrazole ring forms hydrogen bonds to the nitrogen chain of CDK9 Cys106 and the oxygen chain of Asp104 in the hinge region [123]. Additional hydrogen bonds stabilize its position between the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of CDK9.

CAN508 predominantly exhibits its anti-tumor effects through Mcl-1 regulation. Treatment with CAN508 in EAC cell lines revealed decreased Mcl-1, c-MYC, and phosphorylated RNAP II. mRNA levels of Mcl-1 were also decreased, suggesting that CAN508 inhibits Mcl-1 transcription rather than increasing proteasome degradation. Additionally, CAN508 was found to inhibit angiogenesis through a CDK9-dependent mechanism [54].

5.2. LDC067

LDC067 is a CDK9-specific inhibitor (IC50 = 44nM) comprised of a 2,4-aminopyrimidine scaffold with specific ATP-competitive power with a 55-fold selectivity over CDK2 and a 230-fold selectivity over CDK6 and CDK7. LDC067 led to decreased phosphorylation of Ser2 in the CTD of RNAP II in multiple cancer cell lines [124].

In HCC cell lines, LDC067 was found to suppress mitophagy in malignant hepatocytes and thus interfere with cell growth and proliferation. LDC067 downregulated PINK1 and PRKN protein expression through decreased RNAP II phosphorylation. [47]. Higher concentrations of LDC067 had a larger effect on decreasing the expression PINK1 mRNA, suggesting that LDC067 is a transcriptional regulator. It was also found to downregulate the protein expression of the autophagosome marker, MAP1LC3A-II, which was another sign of mitophagy suppression [47]. Furthermore, LDC067 suppressed the deacetylation activity of Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) in HCC cells to further decrease mitophagy activation [47].

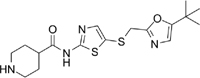

5.3. SNS-032

SNS-032 is an N-acyl-2-aminothiazole that was originally developed as a CDK2 inhibitor (IC50 = 38nM), but was later found to also be a potent inhibitor of CDK7 (IC50 = 38nM) and CDK9 (IC50 = 4nM) [125].

In pancreatic cell lines, SNS-032 functions by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Treatment with SNS-032 on Panc89 cells had the highest response with a 70% decrease in cell growth rate. Analysis of the cell cycle distribution also demonstrated G2 cell cycle arrest only 24 hours after treatment, and then soon shifted to cell death in the SubG1 phase after 48 and 72 hours of treatment [29]. Anti-apoptotic proteins such as Mcl-1, Survivin, and XIAP were also inhibited. SNS-032 has also proven efficacy in combination with standard of care chemotherapy regimens in Panc89 cell lines. Doublet therapy with the CDK9 inhibitor and gemcitabine or irinotecan showed moderate additive effect with gemcitabine but a strong synergistic effect with irinotecan [29].

5.4. THAL-SNS-032

THAL-SNS-032 is CDK9 degrader created by joining SNS-032 to a thalidomide group [126]. Compared to SNS-032, it had similar affinity to CDK9 (IC50 = 4nM), but less against CDK2 (IC50 = 68nM) and CDK4 (IC50 = 398nM). It was found to induce selective degradation of CDK9 in a CRBN-dependent mechanism with no effect on the other targets of SNS-032. CUL4-RBX1-DDB1-CRBN is a ubiquitously expressed E3 ligase receptor that induces ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the protein it is on. CDK9 degraders differed from inhibitors by exerting a prolonged effect, halting non-enzyme dependent functions, and possessing the capability to inhibit previously “undruggable” proteins [126]. However, degraders rely on the presence of CRBN, while inhibitors have anti-proliferative activity irrespective of CRBN.

In vitro studies of THAL-SNS-032 demonstrated degradation of CKD9 within 1 hour of dosing, complete degradation by 2 hours, and apoptosis by 4 hours [126]. Meanwhile, loss of Mcl-1 was seen up to 24 hours after treatment. There were no significant changes in protein levels of cyclin T, ELL, AFF4, or ENL, indicating that the degradation applied only to CDK9 and not to other proteins involved in the SEC.

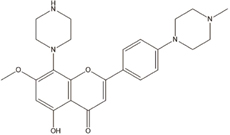

5.5. NVP-2

NVP-2 is a selective aminopyrimidine-derived CDK9 inhibitor. When tested against a kinase panel (Kinomescan), NVP-2 demonstrated potent CDK9/cyclin T inhibition (IC50 < 0.514nM). In comparison to SNS-032, NVP-2 was found to be more selective with sub-nanomolar potency against CDK9. Treatment of cells with NVP-2 revealed decreased phosphorylation of RNAP II CTD residues Ser2, Ser5, and Ser7 in a concentration-dependent manner. Ser2 demonstrated the largest decrease in phosphorylation [126].

Given its higher selectivity and potency than SNS-032, there were multiple attempts to create a degrader with NVP-2. Unfortunately, NVP-2 based degraders could not trigger full CDK9 degradation and had poor anti-proliferative effects [126].

5.6. MC180295

MC180295 is a potent and selective inhibitor towards CDK9/cyclin T (IC50 = 3–12 nM), with 20-fold higher selectivity for CDK9 than other CDKs. Nanomolar doses were enough to dephosphorylate Ser2, while CDK4/6 substrates were only affected at significantly higher doses, and CDK1/2 substrates were not affected [127]. MC180295 demonstrated activity against multiple cancer cell lines, with the strongest effect seen in AML cell lines. However, it still had efficacy against melanoma, colon, bladder, prostate, and breast cancers [127].

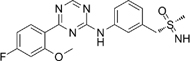

5.7. Atuveciclib (previously known as BAY1143572)

Atuveciclib is an oral, benzyl sulfoximine-based CDK9 inhibitor (IC50 = 6nM) that has shown efficacy in inhibiting growth of xenograft models of AML, TNBC, HCC, prostate cancer, and EAC at nanomolar doses [59, 83, 128, 129]. Atuveciclib inhibits the phosphorylation of Ser2 and Ser7 on RNAP II, eventually downregulating MYC and Mcl-1 [130]. In EAC, atuveciclib amplified the anti-tumoral effect of 5-FU in both EAC cell lines and xenograft models [59]. Additionally, atuveciclib was able to sensitize the EAC xenografts to radiation therapy. Atuveciclib was also found to sensitize PDAC cell lines to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through simultaneous suppression of Mcl-1 and cFLIP [34].

Given its promising preclinical efficacy, atuveciclib was studied in phase 1 trials for advanced hematologic and solid malignancies (Table 2). Unfortunately, the trials were terminated early due to high treatment-related adverse events and lack of clinical response with the tested dose levels.

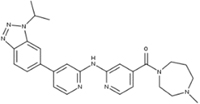

5.8. Enitociclib (previously known as VIP152/BAY1251152)

Enitociclib was developed as a derivative of atuveciclib in an attempt to improve the therapeutic window. It has the same sulfoximine core but with an added 5-fluorine pyridine to allow intravenous administration [131]. Enitociclib demonstrated potent CDK9 inhibition (IC50 = 3nM) with high selectivity for CDK9 over the structurally related CDK2 and CDK7. Compared to its predecessor, enitociclib demonstrated significantly increased CDK9 inhibition with better tolerability and on-target activity. Enitociclib binds to P-TEFb to prevent it from binding to RNAP II, resulting in decreased Mcl-1 expression. A recent phase 1 trial (NCT02635672 and Table 2) demonstrated durable response in patients with advanced solid tumors with an acceptable safety profile [119].

5.9. Iridium (III) complex 1

Iridium(III) complex 1 is a tetrahydroiosuinoline-based ATP-competitive CDK9-cyclin T1 protein-protein interactions (PPI) inhibitor which showed significant activity in slowing the proliferation and migration of TNBC cells [76]. Complex 1 selectively binds with CDK9 in TNBC cell lines to exhibit cytotoxic and anti-metastasis activity. ChIP and qPCR analysis demonstrated that Iridium(III) complex 1 blocked the binding of CDK9 to the c-MYC and Mcl-1 gene promoters, leading to decreased mRNA production. Complex 1 also augmented the protein levels of E-cadherin, a repressor of EMT, and thereby limiting metastasis [76].

5.10. Z11

Z11 is a CDK9 inhibitor that is based on a macrocyclic scaffold with good kinase selectivity and activity (IC50 = 3.2nM). It exhibited significant reduction in cell proliferation and colony formation, while enhancing apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant H975 NSCLC cells. Z11 demonstrated the same ability in both osimertinib-sensitive and osimertinib-resistant patient-derived organoids [62].

5.11. 21e

21e is formed from a pyrrolo-[2,3-d] pyrimidines-2-amine scaffold based on the structure of ribociclib and demonstrates high affinity for the ATP-binding site of CDK9. It is a potent CDK9 inhibitor (IC50 = 11nM) with activity in NSCLC cell lines [132]. 21e reduced the phosphorylation of Ser2 and Ser5 of RNAP II in A549 and H1299 NSCLC cell lines. It induced apoptosis by downregulating the expression of Bcl-2, upregulating the proapoptotic protein BIM, and enhancing caspase-3 activity. Furthermore, 21e suppressed the expression of stem cell transcription factors SOX2, OCT4, NANOG, and KIF4 while also decreasing tumor sphere formation in NSCLC [132].

5.12. UNC10112785

UNC10112785 is a compound with a 7-azaindole pharmacophore that inhibits CDK8, CDK19, and CDK9 in vitro (IC50 = 1.05, 2.67, and 19.9nM respectively) [19]. Studies of UNC10112785 in the KRAS-mutant PDAC cell line, MIA PaCa-2, showed lower levels of MYC mRNA and MYC protein. Interestingly, concurrent use of a proteasome inhibitor was only able to partially delay MYC degradation in the early time points, but not late time points. This suggests that CKD9 is involved in both MYC transcription and protein stability, such as the phosphorylation on Ser62 of MYC [19].

5.13. UNC-721A

UNC-721A was originally created as a broad CDK inhibitor, but was eventually found to be a potent inhibitor of CDK9 (IC50 = 0.603 nM) with high affinity for the CDK9 ATP binding site [133]. UNC-721A is composed of a core aminopyrimidine group which forms two hydrogen bonds to the backbone of the CDK9 hinge motif. The compound creates stable hydrophobic interactions with the Ala46 and Leu156 sidechains in CDK9.

In pancreatic cancer, UNC-721A demonstrated potent dose-dependent inhibition of cell growth in both the gemcitabine-sensitive and the gemcitabine-resistant cell lines. Treatment with UNC-721A correlated with a reduction in phosphorylated CDK9 levels, pSer2 on RNAP II, and Mcl-1 protein expression. There was also a noted steady increase in PARP cleavage, suggesting that UNC-721A induces apoptosis as well as slowing cell proliferation [133].

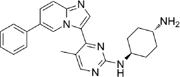

5.14. KI-ARv-03

KI-ARv-03 is a selective CDK9 inhibitor (IC50 = 0.45μM) over other CDKs with 130-fold selectivity [82]. The compound comprises of a pyrazolopyrimidine core with multiple H-bond-accepting groups that makes it structurally similar to other ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors. The primary function of KI-ARv-03 is to engage with the AR-V complex in CRPC to decrease AR-V7 transcription and protein levels through CDK inhibition [82]. It was further refined into the orally bioavailable derivative, KB-0742.

5.15. KB-0742

KB-0742 is an oral CDK9 inhibitor with a greater than 66-fold selectivity over all CDKs and a 100-fold selectivity as compared to CDKs 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Compared to KI-ARv-03, KB-0742 has greater compatibility with the CDK9 ATP-binding pocket. Its amino-pyrazolopyrimidine core binds to the hinge region Cys106 in the ATP-competitive binding pocket while the terminal amine of the diamine-cyclopentane moiety interacts with Asp109. The 3-pentyl group of KB-0742 also forms van der Waals interactions with the Leu156 side chain of CDK9 [134].

Thus far, KB-0742 has shown efficacy in vitro and in vivo. In TNBC cell cultures, KB-0742 inhibited cellular growth (IC50 = 600 nM - 1.2 μM) while inducing significant apoptosis in 4 out of 5 cell lines. KB-0742 also reduced MYC and pSer2 in tumor lysates, leading to concurrent inhibition of tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner [134]. Furthermore, it demonstrated activity in 22Rv1 CRPC cell lines. As KB-0742 prevents the phosphorylation of RNAP II at Ser5, there was significantly decreased AR levels. It also exhibited downregulation of highly transcribed transcription factors, including KLF6, FOXA1, SOX4, and MAFG in 22Rv1 cell-line derived xenografts [82]. Given its pre-clinical success, there is currently an ongoing clinical trial for of KB-0742 in patients with relapsed or refractory solid tumors or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NCT04718675 and Table 2).

5.16. CDDD11-8

CDDD11-8 is an oral, selective inhibitor of CDK9 with a 75- to 328-fold lower potency for other CDKs . CDDD11-8 decreased the phosphorylation of Ser2 on RNAP II and the expression of its target oncogenes in a concentration-dependent manner. ChIP-seq analysis revealed that the MYC, E2F, and G2/M checkpoint genes were paused at the promoter-proximal region rather than undergo elongation [18, 71].

CDDD11-8 demonstrated activity in AML, however, it has also shown potential in solid tumors. Interestingly, when CDDD11-8 was tested in TNBC xenografts and patient-derived breast organoids, there was marked reduction of malignant tissue growth but not in the normal breast xenografts [71].

5.17. AZD4573

AZD4573 is a potent, ATP-selective CDK9 inhibitor (IC50 < 4nM) with an aminopyridine core. AZD4573 decreases the mRNA and protein levels of Mcl-1 without affecting the other anti-apoptotic proteins in the Bcl-2 family. There was also a concurrent increase in caspase-3 cleavage, suggesting that Mcl-1 is an important driver in AZD4573-dependent apoptosis [28].

While most of the preclinical studies have been in hematologic malignancies, AZD4573 has shown potential in solid tumors, especially in overcoming drug resistance. In NSCLC, treatment with AZD4573 decreased viability of KRAS-mutant A549, H460, and H23 and EGFR-mutant H1605, PC9, and H1975 cell lines by preventing the phosphorylation of RNAP II at Ser2, leading to decreased Mcl-1 [61]. While the effect was not as striking, there was a similar decline in cell proliferation in osimertinib-resistant and sotorasib-resistant cell lines. Additionally, the combination of AZD4573, CDK4/6 inhibitor, and fulvestrant showed synergistic effect in slowing ER+ metastatic breast cancer that had become resistant to standard-of-care treatment [66]. While there have been three clinical studies completed or planned for hematologic malignancies (NCT05140382, NCT03263637, NCT04630756), no clinical studies or results have been reported so far for solid tumors.

5.18. LZT-106

LZT-106 is a CDK9 inhibitor with a 30-fold higher selectivity for CDK9 compared with CDK2 (IC50 = 30nM vs 1180nM). The 4-carbonyl group of LZT-106 forms hydrogen bonds with the Cys106 in the hinge region of CDK9 to allow for secure attachment in the ATP binding site [135].

In RKO cell lines, LZT-106 induced apoptosis in CRC cancer cells through Mcl-1 inhibition [135]. Xenograft mouse models with CRC showed significant reduction in tumor volume. Treatment with LZT-106 resulted in a > 70% reduction of Mcl-1 protein levels. Interestingly, there were increased levels of PARP, cleaved caspase-3, and NOXA, suggesting that LZT-106 causes caspase-dependent apoptosis. LZT-106 was also found to target GSK-3b signaling to facilitate Mcl-1 degradation, which is mediated by the phosphorylation of Mcl-1 at Ser159. Overall, LZT-106 promotes the Ser159 phosphorylation, enhances interaction of Mcl-1 and FBW7, and induces Mcl-1 ubiquitination [135].

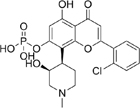

5.19. Fadriciclib (formerly known as CYC065)

Fadriciclib is a dual CDK9 and CDK2 inhibitor (IC50 = 26 and 4.5nM, respectively) which was designed through further optimization of the aminopurine scaffold of seliciclib, a first generation pan-CDK inhibitor [136]. Seliciblib was a competitive ATP-binding inhibitor of CDK1, CDK2, CDK5, and CDK7 but fared poorly in clinical trials. As a monotherapy, it had multiple dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) with low potency and no objective tumor response [137].

Fadriciclib demonstrated activity against TNBC and HER2-amplifed breast cancer cell lines, while non-malignant cell lines were much less sensitive [136]. Fadriciclib also had significant anti-tumoral effect in MYC-driven neuroblastomas as it downregulated the MYCN protein to slow tumor growth. The cell apoptosis from CDK9 inhibition was augmented by concurrent blockade of CDK2 activity, specifically the phosphorylation of histone H and upregulation of proapoptotic CDK2 targets. While fadriciclib can selectively inhibit the growth MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma tumors in vivo, the addition of temozolomide showed complete tumor eradication [138]. Currently there are two ongoing phase 1 trials (NCT04983810 and NCT02552953, Table 2) evaluating fadriciclib in advanced, refractory, or unresectable solid tumors.

5.20. XPW1

XPW1 is a selective CDK9 inhibitor that has shown activity in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) with low toxicity. It functions primarily by inhibiting the transcription of DNA repair mechanisms in ccRCC cells by reducing the phosphorylation of Ser2 at RNAP II [139]. In vivo and in vitro studies demonstrated a decrease in the transcription of Mcl-1, Bcl-1, MYC, and DNA repair genes, which led to significant tumor growth inhibition. The addition of the BRD inhibitor, JQ1, further enhanced XPW1’s anti-tumor effect in ccRCC xenografts [139].

5.21. JSH-150

JSH-150 is a selective CDK9 inhibitor (IC50 = 1nM) with 300–1000-fold selectivity over other CDKs. It demonstrated antiproliferative effects against melanoma, neuroblastoma, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer cell lines through dose-dependent inhibition of Ser2 phosphorylation at RNAP II [140]. This suppressed Mcl-1 and MYC expression, allowing for cell cycle arrest and cell apoptosis.

5.22. LY2857785

LY2857785 is a reversible and competitive ATP kinase inhibitor against CDK9, CDK8, and CDK7 (IC50 = 11nM, 246nM, and 16nM, respectively) that also had good selectivity against a panel of 114 protein kinases [141]. It demonstrated activity in multiple solid tumor cell lines, including lung, osteosarcoma, and melanoma by decreasing the phosphorylation of Ser2 and Ser5 of RNAP II to lower expression of Mcl-1, leading increased apoptosis [141]. Additionally, LY2857785 had an inhibitory effect on the growth and viability of KRAS-mutant and EGFR-mutant cell lines in non-small cell lung cancer, while overcoming resistance to EGFR and KRAS inhibitors [61]. However, it exhibited the same anti-proliferative effects towards normal hematopoietic progenitor cells in rats and dogs, causing severe toxicity of the bone marrow. Given these safety concerns, the development of LY-2857785 was halted [141].

5.23. FIT-039

FIT-039 is dual CDK9 (IC50 = 5.8 μM) and CDK4 inhibitor (IC50 = 30μM) with no effect on CDK2, CDK5, CDK6, or CDK7 [142]. It has anti-viral properties against HIV, HSV, and HPV through blockade of Ser2 on RNAP II to interfere with viral transcription. FIT-039 inhibits HPV replication and expression of the E6 and E7 viral oncogenes, successfully restoring the tumor suppressors p%3 and pRb in HPV-positive cervical cancer cells [143]. The reduction of HPV viral load suppresses HPV-induced dysplasia and hyperproliferation. HPV16+ CaSki xenografts demonstrated significant tumor reduction with FIT-039 treatment [143].

5.24. PHA-767491

PHA-767491 is a dual inhibitor of CDK9 and CDK7 (IC50 = 10nM and 34nM, respectively) that was originally designed as a CDK7 inhibitor only [144, 145]. While well studied in hematologic malignancies, it has also shown activity in several solid tumor preclinical studies.

PHA-767491 had synergistic effect with 5-FU on human HCC cells in vitro and in vivo, especially in overcoming chemotherapy resistance [146]. In contrast as single agents, the combination of PHA-767491 and 5-FU demonstrated stronger cytotoxic effects leading to higher rates of cell apoptosis. Resistance to 5-FU is primarily caused by activation of the checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1), a CDK7 substrate. PHA-767491 inhibited the 5-FU-induced phosphorylation of Chk1 through CDK7 inhibition and downregulated Mcl-1 expression through CDK9 inhibition [146]. In TNBC cell lines with high EGFR expression, PHA-767491 synergizes with lapatinib, an EGFR-TKI, to inhibit proliferation, induce G2-M cell cycle arrest, and increase apoptosis [79].

5.25. LL-K9-3

LL-K9-3 is a selective and potent hydrophobic tag-based degrader of the CDK9-cyclin T1 complex (DC50 values of 662nM and 589nM, respectively). It is comprised of the CDK9 inhibitor, SNS-032, joined by a glycol link to a hydrophobic tag [147].

It has significant activity in prostate cancer cell lines by reducing the expression of AR and MYC. When compared with its parental molecule SNS-032, LL-K9-3 demonstrated stronger anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects by inhibiting AR and MYC-driven signaling. Similarly, it had superior inhibitory effect on AR target genes than the CDK9 PROTAC, Thal-SNS-032 [147].

5.26. TP-1287

TP-1287 is an oral phosphate prodrug of the CDK inhibitor, flavorpiridol, that is enzymatically hydrolyzed to create flavopiridol. It then binds to the ATP-binding site on CDK9 to prevent phosphorylation of Ser2 on RNAP II. Preclinical studies show that TP-1287 decreases Mcl-1 expression ad tumor growth in Ewing sarcoma mouse models [148]. Currently there is an ongoing phase I dose-expansion for patients with metastatic or locally advanced, unresectable Ewing sarcoma (NCT03604783, Table 2).

5.27. CLZX-205

Based on the structure of the CDK inhibitor AZD5438, a new CDK9 inhibitor, CLZX-205, was rationally designed and synthesized. CLZX-205 exerts potent kinase inhibitory activity (IC50 = 2.9nM) with a good pharmacokinetic profile and a strong antitumor efficacy in CRC models (ref [149]. CLZX-205 initiated apoptosis in the HCT116 cells by inhibition of Mcl-1, XIAP, and MYC. Similar biological responses were further validated at the cellular and tumor tissue levels. CLZX-205 is a promising oral CDK9 inhibitor for the treatment of CRC.

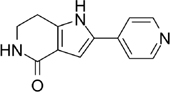

5.28. Zotiraciclib (formerly known as TG02)

Zotiraciclib is a pyrimidine-based macrocycle that was originally characterized as an inhibitor of CDK2, JAK2, and FLT3 [150]. In vitro kinase assays demonstrated that it was a potent inhibitor of CDKs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 9, with an IC50 of 3nM for CDK9. Preclinical studies demonstrated potent inhibition of AML and glioblastoma models through inhibition of CDK and JAK/STAT pathways[112, 150]. Zotiraciclib was tested in two early phase trials on patients with anaplastic astrocytoma or glioblastoma (NCT03224104, NCT02942264) and is being further investigated in an ongoing phase I/II study on patients with high grade gliomas with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations (NCT05588141). See section titled “Glioblastoma” (section 4.13) and Table 2 for further information.

6. Discussion

Recent research on the mechanism of CDK9 have led to the discovery that multiple solid tumors are susceptible to CDK9 inhibition as it functions as a universal regulator of mRNA transcription elongation. However, the unique biology of each malignancy results in dependence on distinctive oncogenic pathways. This could potentially explain why CDK9 inhibition appears to have varying degrees of effect on different molecular pathways and solid tumors. For example, CDK9 inhibition led to strong DKK1 suppression in HCC, as opposed to MMP-9 suppression in NSCLC [52, 63]. These findings can be used to generate novel hypotheses on CDK9 inhibitor combination treatments or help predict mechanisms of resistance. Following the rationale of vertical inhibition of important cancer signaling pathways, one might hypothesize that combination treatment with CDK9 inhibitors and DKK1 inhibitors could synergistically suppress HCC growth and survival. Alternatively, one could envision using CDK9 inhibitors to suppress MMP-9 in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting of NSCLC, in order to hamper tumor invasiveness and prevent recurrence.

Initial development of CDK9 inhibitors resulted in pan-CDK inhibition with significant toxicities. While newer agents are proving to be more specific and potent inhibitors of CDK9, there remain challenges to their clinical development. A common dose limiting toxicity that has emerged in the early trials of CDK9 inhibitors is neutropenia, which is likely from its effect on hematopoietic stem cells. This will limit attempts to combine CKD9 inhibitors with other myelosuppressive agents, such as cytotoxic chemotherapy [113, 114]. While there is pre-clinical evidence on the synergistic effect of CDK9 inhibitors with other treatments such as CDK4/6 inhibitors in breast cancer, irinotecan in pancreatic cancer, and 5-FU in EAC and HCC, there may be challenges in real world application. If truly synergistic drug combinations with CDK9 inhibitors are to be found, then these regimens would need to provide clinical benefit with limited doses of the involved drugs, and ideally rely on partner drugs that have non-overlapping toxicities with CDK9 inhibitors.

The relationship of CDK9 mutations in solid tumors and the efficacy of CDK9i remains to be clarified. In AML, genomic sequencing demonstrated that AML resistance to CDK9 inhibitor is associated with CDK9 L156F mutation [151]. Knocking in CDK9 L156F led to resistance against CDK9 inhibitors and a CDK9 PROTAC degrader. Further studies showed that CDK9 L156F affects inhibitor binding and reduces the thermal stability and catalytic activity of CDK9 protein. A novel CDK9 inhibitor IHMT-CDK9-36 was discovered and could suppress CDK9 WT and L156F mutant AML cells. TCGA database shows that CDK9 mutation occurs in multiple solid tumors, including melanoma, bladder cancer, hepatobiliary cancer, prostate cancer, esophagogastric cancer, ovarian cancer, glioma, head and neck cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, thyroid cancer, renal non-clear cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, glioblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer, cervical cancer [152–154]. Approximately 50 mutation sites were discovered, most of which are missense mutations. The mutation sites are usually located in the CDK9 kinase domain, for example, F30L, E32D, D350A, and D307V. However, the potential effect of CDK9 mutation on cancer drug resistance in solid tumors is still unclear. Understanding CDK9 mutation will be beneficial to drug design, cancer precision treatment, and limit off-target toxicity.

Biomarkers are clinically useful for the determination of prognosis, prediction of therapeutic response, and monitoring of cancer progression [155]. Potential biomarkers for clinical response to CDK9 inhibitors need to be investigated and validated. As there is increasing evidence that CDK9 activation enhances the amplification of MYC in multiple solid malignancies, MYC may be promising biomarker [156]. High or aberrant levels of CDK9 may be critical for the maintenance of MYC-driven tumors, and thus the degree of MYC amplification may correlate with efficacy of CDK9 inhibition. In addition to MYC, Mcl-1 transcription was also transiently suppressed by CDK9 inhibition, which suggests it can be a biomarker candidate. Mcl-1 belongs to BCL-2 protein family and is a known antiapoptotic protein. High-levels of Mcl-1 are associated with enhanced cancer cell survival that result in chemo-resistance and poor prognosis [157]. Therefore, MYC- and Mcl-1-driven solid tumors, such as prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, may benefit from CDK9 inhibitors.

In conclusion, CDK9 represents a promising target for the treatment of solid tumors. Recent innovations such as novel CDK9-targeting drugs and a better understanding of the mechanisms of action are helping to promote renewed interest in these drugs. Importantly, ongoing work will help determine resistance mechanisms and biomarkers of response. Further investigation of synergistic CKD9 inhibitor combinations is also warranted. Ultimately, these scientific advances will need to be translated into novel clinical trials for solid tumor patients.

Acknowledgements

Graphical abstract and figure were created using BioRender.com.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the Montefiore Einstein Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant (5P30CA013330) and the Price Family Foundation.

Glossary

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- ACKR3

Atypical chemokine receptor 3

- ADTs

Androgen-deprivation therapies

- AR

Androgen receptors

- AR-Vs

Alternative splice variants of AR

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BET

Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal

- BID

BH3-Interacting Domain Death Agonist

- BNIP3

BCL2 Interacting Protein

- BRAF

B-Raf Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase

- BRG1

Brahma‐related gene 1

- CCL21

C-C motif chemokine ligand 21

- ccRCC

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- CD8+ T-cells

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- CDKs

Cyclin Dependent Kinases

- cFlip

Cellular FLICE (FADD-like IL-1β-converting enzyme)-inhibitory protein

- Chk1

Checkpoint kinase 1

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- CRPC

Castrate-resistant prostate cancer

- CSCS

Cancer stem cells

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- CTGF

Connective tissue growth factor

- CXCL12

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12

- CYR61

Cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer

- DDK1

Dickkopf-1

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DISC

Death-inducing signaling complex

- DLTs

Dose-limiting toxicities

- DR

Death receptors

- DSIF

DRB-sensitivity inducing factor

- EAC

Esophageal adenocarcinoma

- EEC

Early elongation checkpoint

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- ERK

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase

- ERV

Endogenous retrovirus

- FADD

FAS-associated death domain

- FOXO3

Forkhead Box O3

- HECC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HER2

Erb-B2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 2

- HEXIM1/2

Hexamethylene bisacetamide-inducible proteins

- HIF1A

Hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha

- HRR

Homologous recombination repair

- iASPP

Inhibitor of the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53

- KRAS

Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog

- LBD

Ligand-binding domain

- MAPK

Mitogen activated protein kinase

- MAX

Myc-Associated Factor X

- Mcl-1

Myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1

- MEK

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase

- MSS

Microsatellite-stable

- MYC

Master regulator of cell cycle entry and proliferative metabolism

- NELF

Negative elongation factor

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NK

Natural Killer cells

- NSCLCs

Non-small cell lung cancers

- OS

Overall survival

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PD-L1

Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1

- PINK1

(PTEN induced kinase 1)-PRKN pathway

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PPI

Protein-protein interactions

- P-TEFb

Positive transcription elongation factor β

- PTEN

Phosphatase And Tensin Homolog

- RAS

Rat sarcoma virus

- RBPJ

Recombining binding protein suppressor of hairless

- RNAP II

RNA polymerase II

- RPPA

Reverse phase protein array

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- SEC

Super elongation complex

- SIRT1

NAD-Dependent Protein Deacetylase Sirtuin

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

- SSBs

Single-stand breaks

- SWI/SNF

SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable

- TEAE

Treatment-emergent adverse event

- TGF-B1

Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TNBC

Triple negative breast cancers

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TP53

Tumor protein 53

- TRAIL

(TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing

- TRAs

TRAIL-receptor agonists

- UM

Uveal melanoma

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WT

Wild type

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

Chaoyuan Kuang has a collaboration with VinceRx. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Malumbres M, Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol, 2014. 15(6): p. 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapenna S and Giordano A, Cell cycle kinases as therapeutic targets for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2009. 8(7): p. 547–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao L, et al. , Targeting CDK9 with selective inhibitors or degraders in tumor therapy: an overview of recent developments. Cancer Biol Ther, 2023. 24(1): p. 2219470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shore SM, et al. , Identification of a novel isoform of Cdk9. Gene, 2003. 307: p. 175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H and Herrmann CH, Differential localization and expression of the Cdk9 42k and 55k isoforms. J Cell Physiol, 2005. 203(1): p. 251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giacinti C, et al. , Cdk9–55: a new player in muscle regeneration. J Cell Physiol, 2008. 216(3): p. 576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada T, et al. , P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of hSpt5 C-terminal repeats is critical for processive transcription elongation. Mol Cell, 2006. 21(2): p. 227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egloff S, CDK9 keeps RNA polymerase II on track. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2021. 78(14): p. 5543–5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vos SM, et al. , Structure of paused transcription complex Pol II-DSIF-NELF. Nature, 2018. 560(7720): p. 601–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vos SM, et al. , Architecture and RNA binding of the human negative elongation factor. Elife, 2016. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen FX, Smith ER, and Shilatifard A, Born to run: control of transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2018. 19(7): p. 464–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNamara RP, Bacon CW, and D’Orso I, Transcription elongation control by the 7SK snRNP complex: Releasing the pause. Cell Cycle, 2016. 15(16): p. 2115–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo Z, Lin C, and Shilatifard A, The super elongation complex (SEC) family in transcriptional control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2012. 13(9): p. 543–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]