Key Points

Question

Do the Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI) and the Facial VASI (F-VASI) demonstrate concept validity and adequate performance in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo?

Findings

This mixed-methods study, including a secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of upadacitinib of 164 participants and qualitative interviews of 14 patients, validated the the T-VASI and F-VASI measurement properties and their meaningfulness and clinical relevance for patients with nonsegmental vitiligo. Thresholds for meaningful improvements in both measures were identified and included patient perspectives.

Meaning

Given that the T-VASI and F-VASI are reliable, valid, able to discriminate clinically distinct groups, and responsive to improvements in nonsegmental vitiligo, these tools may be useful in clinical trials of vitiligo treatments.

Abstract

Importance

Defining meaningful improvement using the Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI) and the Facial VASI (F-VASI) aids interpretation of findings from clinical trials evaluating vitiligo treatments; however, clear and clinically meaningful thresholds have not yet been established.

Objective

To assess concept validity and measurement performance of the T-VASI and F-VASI in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo and to identify meaningful change thresholds.

Design, Settings, and Participants

This mixed-methods study consisted of a secondary analysis of a phase 2 multicenter double-blind dose-ranging randomized clinical trial and embedded qualitative interviews conducted at 35 sites in Canada, France, Japan, and the US. The secondary analysis included the trial’s adult patients with nonsegmental vitiligo (T-VASI ≥5 and F-VASI ≥0.5 at baseline). Psychometric performance of the T-VASI and F-VASI and thresholds for meaningful change were evaluated using clinician- and patient-reported information. The trial’s embedded interviews were used to qualitatively assess content validity and patient perceptions of meaningful repigmentation. Data analyses were performed from March to July 2023.

Intervention

Participants were randomized to 6-, 11-, or 22-mg/day upadacitinib or placebo for 24 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Psychometric performance of the T-VASI and F-VASI and thresholds for meaningful changed plus content validity and patient perceptions of meaningful repigmentation. Measurement instruments included the T-VASI, F-VASI, Vitiligo Noticeability Scale, Total-Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment, Face-Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment, Total-Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment (PhGVA-T), Face-Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment (PhGVA-F), Patient’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo, Physician’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo (PhGIC-V), Vitiligo Quality-of-Life Instrument, Dermatology Life Quality Index, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and transcribed verbatim interviews with patients.

Results

The psychometric analysis included 164 participants (mean [SD] age, 46 years; 103 [63%] females) and the qualitative analysis included 14 participants (mean [SD] age, 48.8 [12.2] years; 9 females [64%] and 5 males [36%]). Intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.98 for T-VASI and 0.99 for F-VASI in patients with clinically stable vitiligo between baseline and week 4, supporting test-retest reliability. At baseline and week 24, correlations were moderate to strong between T-VASI and PhGVA-T (r = 0.63-0.65) and between F-VASI and PhGVA-F (r = 0.65-0.71). Average baseline and week-24 VASI scores decreased with repigmentation (ie, increasing PhGVA scores). Least-square mean VASI scores increased with greater repigmentation as measured by the PhGIC-V. Least-square mean VASI scores also differed between patients with improved PhGIC-V and those with no change or worsened V-PhGIC scores. Using a multiple anchor approach, improvements of 30% in T-VASI and 50% in F-VASI scores reflected meaningful repigmentation between baseline and week 24.

Conclusion and Relevance

This mixed-methods study found that the T-VASI and F-VASI are reliable, valid, able to differentiate between clinically distinct groups, and responsive in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo. The thresholds for meaningful change were lower than those historically used in clinical trials, suggesting that T-VASI 50 and F-VASI 75 are conservative estimates and reflect improvements that would be meaningful in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04927975

This mixed-methods study assessed the concept validity and measurement performance of the Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index and the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index and determined meaningful change thresholds in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo.

Introduction

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes skin depigmentation and affects 0.5% to 2.0% of the population worldwide. Nonsegmental vitiligo, the most common form of vitiligo, can affect a large body surface area. Patients with vitiligo report depression, anxiety, shame, low self-esteem, stigmatization, and social isolation, especially when depigmentation affects visible body parts and a larger surface area.

The Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI) is a clinician-reported outcome that assesses the affected body surface area and level of depigmentation. It is based on hand units of depigmentation, each of which corresponds to approximately 1% of the body surface area. Total VASI (T-VASI) is calculated based on the total of the product of hand units and depigmentation in each lesion assessed using preset thresholds (0%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, and 100%). The T-VASI has high inter- and intraobserver reliability, strong test-retest reliability, known groups validity, and good responsiveness to change. A separate assessment of facial depigmentation (F-VASI) has been used in recent clinical trials.

Defining meaningful improvement using the VASI will help interpret the results of clinical trials evaluating vitiligo treatments, but clear and clinically meaningful thresholds have not yet been established. An arbitrary threshold for meaningful improvement of 50% to 75% repigmentation has been used. By contrast, more than 25% repigmentation after 3 months of treatment has been suggested as a meaningful improvement per the findings of a series of workshops with patients with vitiligo and their parents or caregivers. More recently, based on data from a phase 2 clinical trial, Rosmarin et al reported that a 42% decrease in T-VASI and 57% decrease in F-VASI corresponded to patients’ global impressions of very much or much improved vitiligo. Also, a qualitative patient interview study by Kitchen et al suggested that patients consider a 75% improvement in F-VASI and 50% improvement in T-VASI as meaningful improvements.

This mixed-methods study aimed to evaluate the content validity and measurement performance of the T-VASI and F-VASI and determine thresholds of meaningful change including patient perspectives on meaningful repigmentation.

Methods

This mixed-methods study included a secondary analysis of the Evaluation of Upadacitinib in Subjects With Non-Segmental Vitiligo (AbbVie No. M19-015), a phase 2 multicenter, randomized clinical trial (RCT). The RCT was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines, applicable regulations, and guidelines governing clinical study conduct, as well as the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. The embedded interviews were approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (Pro00061331). All participants provided informed consent before participating, and interviews were audiorecorded with their permission. The study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Study Design

This study used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate the content validity and measurement properties of the T-VASI and F-VASI based on data collected in the phase 2 RCT. Results from interviews embedded during the trial were also analyzed to confirm the content validity and measurement properties of the T-VASI and F-VASI and to define meaningful change from the trial participants’ perspectives. In addition, thresholds for meaningful change were determined using a robust multiple-anchor approach in accordance with regulatory guidelines.

Data Sources

This study used data from the RCT—a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial on the safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in adults aged 18 to 65 years with nonsegmental vitiligo. The RCT was conducted between June 16, 2021, and August 29, 2023, at 35 sites in Canada, France, Japan, and the US. Patients were included in the RCT if they had a clinical diagnosis of nonsegmental vitiligo and a F-VASI of 0.5 or greater and a T-VASI of 5.0 or greater at screening and baseline visits. Details of the key selection criteria are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 2. The RCT comprised a 35-day screening period, a 24-week double-blind treatment period (period 1), a 28-week blinded long-term extension (period 2), and a 30-day follow-up period (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Its primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline in F-VASI at the end of the double-blind treatment period (week 24).

The RCT’s embedded interviews sought to identify concepts (signs, symptoms, and impacts) important to patients with vitiligo; understand patient perspectives for what degree and location of repigmentation constitutes a meaningful change with treatment; and assess the content validity of the VASI. Those participating in the interviews had to meet all of the RCT inclusion criteria and be able to speak and read English. Interviews took place within 4 weeks of completing the 24-week double-blind treatment period (period 1), or for patients who chose to terminate the trial before the week-24 visit, within 4 weeks of early termination visit. The interviewer and participants were blinded to treatment group assignment. Site staff identified patients and introduced the study using a standardized script during a telephone conversation or when patients presented in the office for their week-24 visits. Eligible patients who consented to be interviewed and agreed to be audiorecorded were contacted by an interviewer (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Telephone interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were guided by a semistructured interview guide (eAppendix in Supplement 2). For all RCT participants and interviewees, demographic characteristics including race and ethnicity (where permitted by law) were collected via patient self-report.

Psychometric analysis and thresholds for meaningful change of the T-VASI and F-VASI were based on RCT data. There were 184 adult patients with nonsegmental vitiligo in the RCT; however, our study’s psychometric analysis included only those with complete patient- and clinician-reported outcome data at baseline and weeks 4, 12, and 24. Regarding the qualitative analysis of the embedded interviews, our study used data from the 6 sites in the US that agreed to recruit participants for interviews (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Outcome Measures

Patient- and clinician-reported outcome measures collected in the trial and analyzed included the T-VASI, F-VASI, Vitiligo Noticeability Scale, Total-Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment (PaGVA-T), Face-Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment (PaGVA-F), Total-Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment (PhGVA-T), Face-Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment (PhGVA-F), Patient’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo (PaGIC-V), Physician’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo (PhGIC-V), Vitiligo Quality-of-Life Instrument (VitiQoL), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Scoring of the VASI is described in eFigure 2 in Supplement 2. The other patient- and physician-reported measures of vitiligo assessed in the trial and analyzed in this study are summarized in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Semistructured interviews (eAppendix in Supplement 2) were used to collect qualitative data on concepts, perspectives, and definitions of meaningful change from patients with vitiligo. Audio files were transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Psychometric and Thresholds Analyses

Psychometric analysis was conducted with all randomized participants who had complete VASI data at baseline and weeks 4, 12, and 24 (known groups and meaningful change) or at baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, and 24 (test-retest reliability). Patients with missing data were not included, and missing data were not imputed. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed from March to July 2023 using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

To assess reliability of the F-VASI and T-VASI, scores were compared between the screening and baseline visit, between which no vitiligo-related changes in depigmentation were expected because no treatment had been initiated. F-VASI and T-VASI responses were also compared between baseline and week 4 among the clinically stable population (defined as participants with no change in response on the PhGVA-F [for F-VASI] and PhGVA-T [for T-VASI] between baseline and week 4). For both analyses, paired t tests, Spearman correlations, and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated. Scatterplots were also used to assess reliability. Spearman correlations greater than 0.70 and no significant changes in paired t tests were considered indicative of good test-retest reliability. ICCs were calculated using absolute agreement 2-way mixed-effect models, with the time as a fixed event Test-retest reliability is considered high or excellent when the ICC is greater than 0.90; good, 0.75 to 0.90; moderate, 0.50 to 0.75; and poor, less than 0.50.

Convergent and divergent validity were analyzed using Spearman rank correlation coefficients at baseline and week 24 between the F-VASI and the T-VASI and the PhGVA-T/PhGVA-F, PaGVA-T/PaGVA-F, VitiQOL, DLQI, and HADS. Correlations of less than 0.30 were considered to be weak; 0.30 to 0.70, moderate; and greater than 0.7, strong. We expected moderate to strong correlations between the F-VASI and T-VASI and global assessments (convergent validity) and weak to moderate correlations between the F-VASI and T-VASI and VitiQOL, DLQI, and HADS (divergent validity).

For known-groups validity, analysis of variance was used to assess the significance of the difference in F-VASI and T-VASI mean scores between groups (defined by response options on the patient and physician global assessments) at baseline and at week 24. We expected that with more extensive depigmentation, mean scores on the F-VASI and T-VASI would increase.

To evaluate responsiveness, changes in F-VASI and T-VASI scores (from baseline to week 24) were compared across meaningful levels of change based on the following anchors: PhGIC-V, PaGIC-V, PhGVA-F (for F-VASI), and PhGVA-T (for T-VASI). General linear models were used controlling for baseline score, age, sex, and Fitzpatrick skin tone.

Findings from the anchor-based methods and graphical representations were used to triangulate the meaningful score differences for the F-VASI and T-VASI. Empirical cumulative distribution function curves were generated for baseline to week 24 change scores in the F-VASI and T-VASI.

Qualitative Analysis

For analysis of qualitative interview data, coding dictionaries were developed based on the interview guide and updated as needed throughout the coding process. A professional transcription service transcribed the audio files verbatim. Transcripts were anonymized by removing all protected health information and reviewed for quality. A content analysis approach was used to analyze encoded transcripts in ATLAS.ti (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Germany).

Results

Psychometric and Thresholds Analyses

Study Sample

The psychometric analysis included 164 participants for whom complete patient- and clinician-reported outcome data were available from the RCT at baseline and weeks 4, 12, and 24. The group had a mean (SD) age of 46 (11) years and was composed of 103 (63%) females and 61 (37%) males, of whom 1 (0.6%) self-identified as American Indian/Alaskan Native, 23 (14.0%) Asian, 11 (6.7%) Black, 1 (0.6%) Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 113 (69.0%) White, 4 (2.4%) multiple races, and 11 (6.7%) were unspecified; 16 (10.0%) were also of Hispanic ethnicity. Additional details are available in eTable 2 in Supplement 2.

Test-Retest Reliability

Correlations for the T-VASI and F-VASI were high between screening and baseline (r = 0.99 for T-VASI and 0.92 for F-VASI) and in patients who were clinically stable between baseline and week 4 (r = 0.98 for T-VASI and F-VASI) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). ICCs indicated excellent test-retest reliability for the T-VASI (0.98-0.99) and F-VASI (0.95-0.99), and results of t tests were not significant.

Convergent and Divergent Validity

T-VASI correlated moderately with PhGVA-T (r = 0.63 at baseline and 0.65 at week 24) and PaGVA-T (r = 0.61 at baseline and 0.53 at week 24) (Table 1). Similarly, F-VASI correlated moderately to strongly with PhGVA-F (r = 0.65 at baseline, 0.71 at week 24) and correlated moderately with PaGVA-F at baseline (r = 0.55) but only weakly at week 24 (r = 0.28). Neither the F-VASI nor the T-VASI correlated significantly with VitiQoL, DLQI, or HADS anxiety or depression subscales (r ≤ 0.15). Except for a weak correlation between F-VASI and PaGVA-F at week 24, all of the correlations were as expected.

Table 1. Construct Validity of the T-VASI and F-VASI.

| Outcome measure | T-VASI | F-VASI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 24 | Baseline | Week 24 | |||||

| Spearman correlation | P value | Spearman correlation | P value | Spearman correlation | P value | Spearman correlation | P value | |

| PhGVA-T | 0.63 | <.001 | 0.65 | <.001 | 0.20 | .01 | 0.38 | <.001 |

| PhGVA-F | 0.22 | <.01 | 0.35 | <.001 | 0.65 | <.001 | 0.71 | <.001 |

| PaGVA-T | 0.61 | <.001 | 0.53 | <.001 | 0.11 | .16 | −0.01 | .10 |

| PaGVA-F | 0.25 | .001 | 0.21 | <.01 | 0.55 | <.001 | 0.28 | <.001 |

| VitiQoL | 0.16 | .04 | 0.12 | .12 | 0.05 | .53 | 0.06 | .47 |

| DLQI | 0.20 | .01 | 0.15 | .07 | 0.02 | .80 | 0.15 | .06 |

| HADS-anxiety | 0.06 | .45 | −0.08 | .35 | −0.05 | .57 | −0.12 | .12 |

| HADS-depression | 0.14 | .07 | 0.06 | .48 | < −0.001 | .96 | <0.01 | .97 |

| VNS | NA | NA | −0.24 | <.01 | NA | NA | −0.15 | .07 |

Abbreviations: DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PaGVA-F, Face Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment; PhGVA-F, Face Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment; F-VASI, Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NA, not applicable; PaGVA-T, Total Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment; PhGVA-T, Total Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment; T-VASI, Total-Vitiligo Area Scoring Index; VitiQoL, Vitiligo Quality-of-Life Instrument; VNS, Vitiligo Noticeability Scale.

Known-Groups Validity

T-VASI and F-VASI were able to differentiate between levels of depigmentation in the expected direction based on patient and clinician global assessments, with statistically significant pairwise comparisons in most cases (Table 2). Conclusions should not be drawn from pairwise comparisons between groups with small sample sizes (fewer than 5 participants; “none” response for extent of depigmentation).

Table 2. Known-Groups Validity for T-VASI and F-VASI.

| Global assessment | Time | Extent of depigmentation, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Limited | Moderate | Extensive | Very extensive | Overall F value | P value for pairwise comparisonsa | |||||||

| No. | VASI | No. | VASI | No. | VASI | No. | VASI | No. | VASI | ||||

| T-VASI | |||||||||||||

| Physician (PhGVA-T) | Baseline (n = 156) | 1 | 54.8 (NA) | 10 | 9.1 (3.8) | 69 | 12.6 (8.1) | 62 | 27.7 (15.6) | 14 | 48.9 (21.0) | 31.6 | 1: .03; 2: .04; 3: .37; 4: >.99; 5: .96; 6: <.01; 7: <.001; 8: <.001; 9: <.001; 10: <.001 |

| Week 24 (n = 157) | NA | NA | 12 | 7.1 (3.8) | 76 | 11.5 (7.9) | 59 | 26.7 (14.9) | 10 | 53.4 (22.8) | 48.5 | 5: .71; 6: <.001; 7: <.001; 8: <.001; 9: <.001; 10: <.001 | |

| Patient (PaGVA-T) | Baseline (n = 164) | 1 | 55.5 (NA) | 11 | 7.6 (4.4) | 60 | 13.2 (9.9) | 62 | 24.3 (14.2) | 30 | 38.8 (20.3) | 22.1 | 1: .03; 2: .06; 3: .29; 4: .84; 5: .82; 6: .01; 7: <.001; 8: <.01; 9: <.001; 10: <.001 |

| Week 24 (n = 160) | 1 | 26.6 (NA) | 20 | 11.2 (12.8) | 61 | 12.3 (10.9) | 56 | 23.7 (15.6) | 22 | 35.0 (21.3) | 12.8 | 1: .90; 2: .92; 3: >.99; 4: .99; 5: >.99; 6: .03; 7: <.001; 8: <.01; 9: <.001; 10: .06 | |

| F-VASI | |||||||||||||

| Physician (PhGVA-F) | Baseline (n = 159) | NA | NA | 14 | 0.6 (0.2) | 86 | 0.8 (0.4) | 43 | 1.40 (0.6) | 16 | 2.2 (0.7) | 45.0 | 5: .35; 6: <.001;7: <.001; 8: <.001; 9: <.001; 10: <.001 |

| Week 24 (n = 157) | 1 | 0 (NA) | 39 | 0.3 (0.2) | 74 | 0.8 (0.5) | 37 | 1.32 (0.6) | 6 | 2.4 (0.4) | 41.7 | 1: .98; 2: .61; 3: .10; 4: <.001; 5: <.001; 6: <.001; 7: <.001; 8: <.001; 9: <.001; 10: <.001 | |

| Patient (PaGVA-F) | Baseline (n = 164) | 1 | 1.4 (NA) | 35 | 0.6 (0.3) | 69 | 1.0 (0.5) | 44 | 1.38 (0.7) | 15 | 1.9 (0.7) | 18.4 | 1: .75; 2: .97; 3: >.99; 4: .93;5: .053; 6: <.001; 7: <.001; 8: <.01; 9: <.001; 10: .04 |

| Week 24 (n = 160) | 2 | 2.0 (0.3) | 40 | 0.6 (0.5) | 68 | 0.6 (0.5) | 40 | 1.10 (0.7) | 10 | 1.6 (0.8) | 11.4 | 1: .03; 2: .03; 3: .32; 4: .89; 5: >.99; 6: <.01; 7: <.001; 8: <.01; 9: <.001; 10: .33 | |

Abbreviations: F-VASI, Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index; NA, not applicable; PaGVA-F, Face Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment; PhGVA-F, Face Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment; T-VASI, Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index; PaGVA-T, Total Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment; PhGVA-T, Total Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment.

Post hoc comparisons using Scheffe test to determine whether T-VASI and F-VASI scores discriminated between groups. Pairwise comparisons: 1, no vs limited; 2, no vs moderate; 3, no vs extensive; 4, no vs very extensive; 5, limited vs moderate; 6, limited vs extensive; 7, limited vs very extensive; 8, moderate vs extensive; 9, moderate vs very extensive; and 10, extensive vs very extensive.

T-VASI and F-VASI Responsiveness

Comparison of changes between baseline and week 24 in T-VASI and F-VASI scores across meaningful levels of changes in PhGIC-V and PaGIC-V were evaluated. The results indicated that both T-VASI and F-VASI were responsive to change (Table 3).

Table 3. Change in VASI From Baseline by Global Impression of Change at Week 24.

| Scale | Outcome measure | Improvement | No change | Worsened | Overall F valuea | P value for pairwise comparisonsb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | LS mean (SE) [95% CI] | No. | LS mean (SE) [95% CI] | No. | LS mean (SE) [95% CI] | ||||

| T-VASI | PhGIC-V | 76 | −5.7 (0.8) [−7.4 to −4.0] | 68 | −0.8 (0.8) [−2.4 to 0.9] | 13 | 0.9 (1.6) [−2.3 to 4.1] | 5.6 | 1: <.001; 2: <.001; 3: .59 |

| PaGIC-V | 74 | −6.0 (0.8) [−7.6 to −4.3] | 60 | −0.7 (0.8) [−2.3 to 1.0] | 26 | −0.8 (1.2) [−3.2 to 1.6] | 5.7 | 1: <.001; 2: <.001; 3: >.99 | |

| F-VASI | PhGIC-V | 76 | −0.5 (0.1) [−0.6 to −0.4] | 68 | −0.1 (0.1) [−0.2 to 0.03] | 13 | −0.01 (0.11) [−0.2 to 0.2] | 8.3 | 1: <.001; 2: ≤.0001; 3: .78 |

| PaGIC-V | 74 | −0.5 (0.1) [−0.5 to −0.3] | 60 | −0.1 (0.1) [−0.3 to −0.02] | 26 | −0.03 (0.08) [−0.2 to 0.1] | 6.2 | 1: <.001; 2: <.001; 3: .47 | |

Abbreviations: F-VASI, Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index; LS, least-squares; PaGIC-V, Patient’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo; PhGIC-V, Physician’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo; SE, standard error; PaGVA-T, Total-Patient Global Vitiligo Assessment; T-VASI, Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index.

General linear model controlling for covariates (T-VASI baseline score, age, sex, skin tone).

Pairwise comparisons between LS means were performed using Scheffe test adjusting for multiple comparisons: 1, improvement vs no change, 2, improvement vs worsened; and 3, no change vs worsened.

Meaningful Score Differences for T-VASI and F-VASI

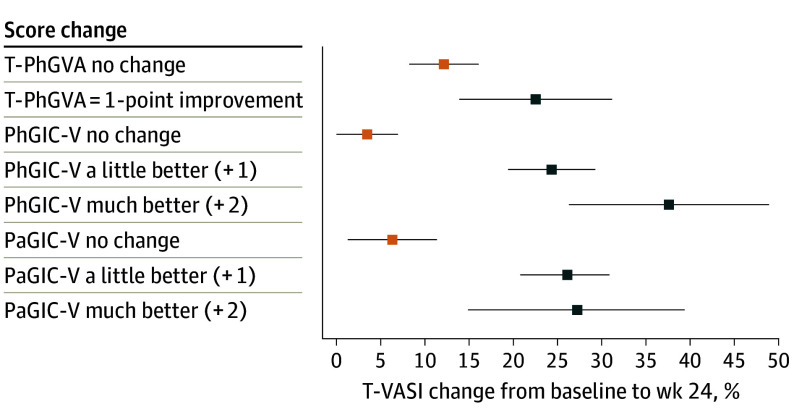

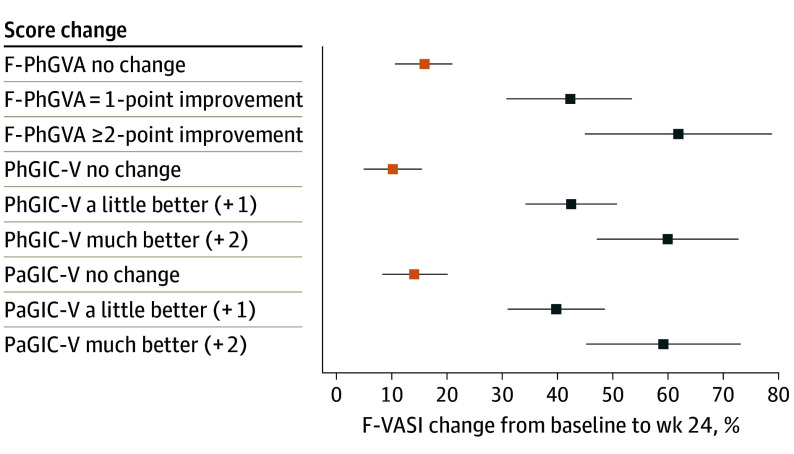

Percentage changes in T-VASI and F-VASI scores were examined using responses on global anchors indicating improvement (much better and a little better on PhGIC-V/PaGIC-V; 1- and 2-point improvements on PhGVA-F/PhGVA-T). For T-VASI, anchor-based estimates showed improvement between 22.6% and 37.7% (Figure 1), and for F-VASI, improvement between 39.8% and 61.9% (Figure 2). These results suggested a 30% improvement in T-VASI and 50% improvement in F-VASI as thresholds for a clinically meaningful change. Using the same global anchors, the percentage score change at week 24 was 3.6% to 12.2% for T-VASI and 10.2% to 15.8% for F-VASI for the “no change” responses.

Figure 1. Estimates of T-VASI Percentage Score Change From Baseline to Week 24.

Abbreviations: PaGIC-V, Patient’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo; PhGIC-V, Physician’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo; PhGVA-T, Total Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment; T-VASI, Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index.

Data points show mean percentage score change and 95% CIs.

Figure 2. Estimates of F-VASI Percentage Score Change From Baseline to Week 24.

Abbreviations: F-VASI, Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index; PaGIC-V, Patient’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo; PhGVA-F, Face Physician Global Vitiligo Assessment; PhGIC-V, Physician’s Global Impression of Change-Vitiligo.

Data points show mean percentage score change and 95% CIs.

Empirical cumulative distribution function curves showed that a threshold of 50% improvement from baseline to week 24 in T-VASI results in marked separation between patients with improvements of much better and a little better and other categories, as determined by their own and a physician’s global assessments as well as between 1-point improvement and no change or worsening between baseline and week 24 in PhGVA-T. Similarly, a threshold of 75% improvement from baseline to week 24 in F-VASI results in a clear separation between the categories much better and a little better, while the categories no change and a little or much worse did not show good differentiation (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2).

Embedded Interviews

Study Sample

Embedded interviews were completed by 14 participants (mean [SD] age, 48.8 [12.2] years; 9 females [64%] and 5 males [36%]; 1 (7.0%) Black, 1 (7.%) Hispanic/Latine, and 12 [86%] White individuals) (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). One withdrew early due to a potential adverse event. The other 13 participants completed the trial to week 24. Five had received placebo, and 9 had received treatment with upadacitinib, 6 mg (1 participant), 11 mg (5 participants), or 22 mg (3 participants).

Signs, Symptoms, and Impacts

The body areas most reported by participants as being affected by vitiligo were the face (n = 3) and knees (n = 3), the hands and/or fingers (n = 2), arms (n = 2), stomach (n = 1), legs (n = 1), feet (n = 1), and armpits (n = 1). All participants reported depigmentation, the concept measured by the VASI, and all agreed that depigmentation was the most common or primary symptom, or described skin depigmentation first when asked about signs and symptoms. Other signs and symptoms included skin sensitivity to the sun (eg, sunburning easily; n = 10), loss of hair color (n = 8), and other skin signs (cracking, flaking, sore areas, and dry skin [n = 1 each]). Life impacts included covering the skin (n = 10); reduced confidence and feeling self-conscious (n = 4); having to plan life activities around vitiligo (n = 2); mental health effects (n = 1); career impacts (n = 1); or none (n = 1).

Repigmentation and Meaningful Changes

Participants stated that the most important area to have repigmentation was the face (n = 10), followed by the hands (n = 2), legs (n = 1), and arms (n = 1). Participants described selecting the body areas according to the places where vitiligo was most widespread or most noticeable to others. All participants were asked what amount of improvement in repigmentation they would consider meaningful: 8 participants (57%) responded 10% to 50% repigmentation (10%, 1 participant; 25%, 3; 30%, 1; and 50%, 3) would be meaningful; 1 participant (7%) said anything noticeable would be meaningful; and 2 participants (14%) responded more than 50% repigmentation (100% and 60%, respectively). The remaining 3 participants described different amounts of repigmentation in different body areas based on the noticeability of depigmented areas. Of these 3 participants, 1 indicated 100% for the face and 75% for arms and legs; another estimated 25% but was concerned that repigmentation of 25% in certain areas of the face would make other depigmented spots on the face more noticeable. The remaining participant ranked their body areas but did not provide a threshold.

Discussion

This study used a mixed approach that combined quantitative and qualitative RCT data from the same patient population to evaluate and confirm the validity and clinical meaningfulness of the F-VASI and T-VASI thresholds commonly used in clinical trials. The findings showed that in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo, the T-VASI and F-VASI are reproducible, have construct validity, are able to differentiate between known groups, and are responsive to improvements in depigmentation. These findings agree with those of another study showing that the T-VASI has high inter- and intraobserver reliability, strong test-retest reliability, known-groups validity, and good responsiveness to change in patients with vitiligo.

The current study also confirmed that depigmentation, especially in the face and hands, is the primary concern for patients with vitiligo and that the VASI measures concepts and repigmentation that are clinically meaningful to patients. A strength of the study was the inclusion of patient-centered outcome measures that include concepts of health-related quality of life (DLQI and VitiQoL). While these instruments measure concepts that are distal to the primary efficacy evaluation (repigmentation), they include important concepts to patients. Although measuring the clinician assessment of repigmentation is critical to assessing the clinical response, clinical trials of new vitiligo treatments should also capture the patient-reported perspectives on treatment success using sensitive patient-reported outcomes tools as a part of the study end points. Including patient-reported outcomes is likely important given the weak correlation between T-VASI and F-VASI with quality of life, which could reflect that these are not patient-centered outcomes.

Using a multiple anchor approach, this study showed that a 30% improvement in T-VASI and a 50% improvement in F-VASI corresponded to meaningful changes. Similarly, using a single anchor of patients’ global impression of change, Rosmarin et al suggested thresholds of 42% improvement in T-VASI and 57% improvement in F-VASI. Both are lower than the thresholds of 50% for T-VASI and 75% for F-VASI recently described by Kitchen et al in a qualitative study. Although our qualitative data revealed substantial variability in patients’ perception of meaningful change, most patients reported thresholds below T-VASI 50 and F-VASI 75 as meaningful. With clear evidence that a lower threshold can be used to detect change on the VASI measures, the authors are confident that the higher thresholds proposed by Kitchen et al would be effective in detecting meaningful changes in clinical trials of vitiligo treatments and, as shown by our study, they should be able to discriminate between different levels of response. Using the T-VASI 50 and F-VASI 75 to define meaningful change in a clinical trial is a conservative approach because fewer treatment responders will be detected. Additionally, using the same thresholds for clinically meaningful within-patient changes across trials will allow treatment responses to be better understood and compared among trials.

Although the VASI has been used in many clinical trials, a concern is the potential for interrater variability due to differences in how the scale is applied and its semiquantitative nature. This can complicate comparisons of absolute scores between trials. Nonetheless, as shown in this and another study, T-VASI and F-VASI have very good within-patient reproducibility.

Limitations

A limitation of the current study is that the psychometric analysis was on a homogenous study population (White race, middle-aged, and only English-speaking). Another potential limitation is that the qualitative findings involved only a small sample of patients who were willing to participate in interviews, although this would not be expected to change the results.

Conclusions

This study confirms the measurement properties of the T-VASI and F-VASI as well as the meaningfulness and clinical relevance of the concepts included in them. The RCT data suggest that thresholds as low as 30% improvement in T-VASI and 50% improvement in F-VASI may represent meaningful change. Therefore, the routine thresholds of 50% improvement in T-VASI and 75% improvement in F-VASI suggested by Kitchen et al would be effective at detecting patients’ perception of meaningful change in clinical trials of vitiligo treatments. Accordingly, the T-VASI and F-VASI should be appropriate for use in clinical trials treatments for patients with nonsegmental vitiligo.

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Key Selection Criteria for the Phase 2 Trial

eTable 1. Sites Recruiting Participants for Embedded Interviews

eTable 2. Interviewers

eTable 3. Additional Patient- and Physician-reported Outcomes for Assessing Vitiligo

eTable 4. Reproducibility and Test-retest Reliability of the T-VASI and F-VASI

eTable 5. Patient Characteristics

eFigure 1. Schematic of the Phase 2 Clinical Trial

eFigure 2. T-VASI and F-VASI Scoring Sheet

eFigure 3. Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function Curves for T-VASI (A-C) and F-VASI (D-F) Across Response Levels

eAppendix. Semi-structured Interview Guide

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Bergqvist C, Ezzedine K. Vitiligo: a review. Dermatology. 2020;236(6):571-592. doi: 10.1159/000506103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi K, Ezzedine K, Anastassopoulos KP, et al. Prevalence of vitiligo among adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(1):43-50. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimes PE, Miller MM. Vitiligo: patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(1):32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae JM, Lee SC, Kim TH, et al. Factors affecting quality of life in patients with vitiligo: a nationwide study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):238-244. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(2):159-164. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Geel N, Moock C, Zuidgeest M, Uitentuis SE, Wolkerstorfer A, Speeckaert R. Patients’ perception of vitiligo severity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101(6):adv00481. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezzedine K, Soliman AM, Li C, Camp HS, Pandya AG. Economic burden among patients with vitiligo in the United States: a retrospective database claims study. J Invest Dermatol. 2024;144(3):540-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezzedine K, Soliman AM, Li C, Camp HS, Pandya AG. Comorbidity burden among patients with vitiligo in the United States: a large-scale retrospective claims database analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(10):2265-2277. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-01001-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merhi S, Salameh P, Abboud M, et al. Facial involvement is reflective of patients’ global perception of vitiligo extent. Br J Dermatol. 2023;189(2):188-194. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental Health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(10):1124-1128. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamzavi I, Jain H, McLean D, Shapiro J, Zeng H, Lui H. Parametric modeling of narrowband UV-B phototherapy for vitiligo using a novel quantitative tool: the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(6):677-683. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.6.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komen L, da Graça V, Wolkerstorfer A, de Rie MA, Terwee CB, van der Veen JP. Vitiligo Area Scoring Index and Vitiligo European Task Force assessment: reliable and responsive instruments to measure the degree of depigmentation in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(2):437-443. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10244):110-120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30609-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al. ; TRuE-V Study Group . Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(16):1445-1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitton M, Pinart M, Batchelor JM, et al. Evidence-based management of vitiligo: summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(5):962-969. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, Lushey C, Leonardi-Bee J, González U. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopes C, Trevisani VF, Melnik T. Efficacy and safety of 308-nm monochromatic excimer lamp versus other phototherapy devices for vitiligo: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(1):23-32. doi: 10.1007/s40257-015-0164-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eleftheriadou V, Hamzavi I, Pandya AG, et al. International Initiative for Outcomes (INFO) for vitiligo: workshops with patients with vitiligo on repigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(3):574-579. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitchen H, Wyrwich KW, Carmichael C, et al. Meaningful changes in what matters to individuals with vitiligo: content validity and meaningful change thresholds of the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI). Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(7):1623-1637. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00752-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Passeron T, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adults with extensive non-segmental vitiligo: a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;73:102655. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tour SK, Thomas KS, Walker DM, Leighton P, Yong AS, Batchelor JM. Survey and online discussion groups to develop a patient-rated outcome measure on acceptability of treatment response in vitiligo. BMC Dermatol. 2014;14:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-14-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lilly E, Lu PD, Borovicka JH, et al. Development and validation of a vitiligo-specific quality-of-life instrument (VitiQoL). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(1):e11-e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210-216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hays RD, Revicki DA. Reliability and validity, including responsiveness. In: Fayers P, Hays RD, eds. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2005. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198527695.003.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(1):30-46. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420-428. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin S, Nelson L, McLeod L, Eremenco S, Coons SJ. Assessing test-retest reliability of patient-reported outcome measures using intraclass correlation coefficients: recommendations for selecting and documenting the analytical formula. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(4):1029-1033. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-2076-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinkle DE. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Houghton Mifflin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied Thematic Analysis. 2012. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://methods.sagepub.com/book/applied-thematic-analysis

- 32.Kitchen H, Gandhi K, Carmichael C, et al. A qualitative study to develop and evaluate the content validity of the vitiligo patient priority outcome (ViPPO) measures. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(8):1907-1924. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00772-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ceresnie MS, Warbasse E, Gonzalez S, Pourang A, Hamzavi IH. Implementation of the vitiligo area scoring index in clinical studies of patients with vitiligo: a scoping review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(8):2233-2259. doi: 10.1007/s00403-023-02608-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Key Selection Criteria for the Phase 2 Trial

eTable 1. Sites Recruiting Participants for Embedded Interviews

eTable 2. Interviewers

eTable 3. Additional Patient- and Physician-reported Outcomes for Assessing Vitiligo

eTable 4. Reproducibility and Test-retest Reliability of the T-VASI and F-VASI

eTable 5. Patient Characteristics

eFigure 1. Schematic of the Phase 2 Clinical Trial

eFigure 2. T-VASI and F-VASI Scoring Sheet

eFigure 3. Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function Curves for T-VASI (A-C) and F-VASI (D-F) Across Response Levels

eAppendix. Semi-structured Interview Guide

Data Sharing Statement