Key Points

Question

What are the experiences, practices, and perspectives of normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) by organ procurement organizations (OPOs) in the United States as of the end of 2023?

Findings

In this survey study of 55 OPOs with 100% response rate, 49 OPOs reported experience with NRP. There was wide variation in NRP experience and practice; 52 OPOs desired standardized guidelines related to NRP.

Meaning

These results suggest that improved standardization of NRP policies, protocols, and practices are desired and necessary to maximize organ donation and transplantation potential from donation after circulatory determination of death donors.

This survey study investigates organ procurement organizations’ experience, operational practices, and needs related to normothermic regional perfusion (NRP).

Abstract

Importance

Despite the unmet need for donor organs, organ use from donation after circulatory determination of death (DCD) donors has been limited by inferior transplant outcomes. Normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) improves recipient outcomes and organ utilization from DCD donors. There is variability in NRP policies and experience among US organ procurement organizations (OPOs).

Objectives

To determine OPO experience, identify operational inconsistencies, and explore needs related to NRP.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This survey study included 55 OPOs in the US that had recovered DCD organs and completed a survey on operational, administrative, and educational components related to NRP in November to December 2023. Data analysis was performed from February to April 2024.

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary outcome was the number of OPOs participating in and/or anticipating NRP participation. Secondary outcomes were NRP implementation barriers, OPO education practices, and future needs regarding consensus NRP recommendations and standards.

Results

Of 55 respondents, 11 (20%) were chief executive officers, 8 (15%) were chief operating officers, and 36 (65%) were medical directors or chief clinical officers. Forty-nine OPOs facilitated NRP cases: 26 OPOs (53%) facilitated both thoracoabdominal NRP (TA-NRP) and abdominal NRP (A-NRP) cases, 16 OPOs (33%) facilitated only TA-NRP, and 7 OPOs (14%) facilitated only A-NRP. OPOs reported 606 NRP cases (421 TA-NRP [69%], 185 A-NRP [31%]); median (range) case experience was 8 (1-52). Fifty-two of 55 OPOs (95%) thought standardized guidance documents would be helpful. All 49 OPOs facilitated NRP at a transplant center’s request; 39 (80%) had NRP initiated by a nonlocal transplant center. Twenty-three of 49 OPOs (47%) participated in NRP without a policy and without a policy pending approval. Positive donor hospital feedback was received by 29 OPOs (59%), primarily focused on increased organs transplanted and prerecovery communication. Allocation challenges were experienced by 21 OPOs (43%); their median (range) case volume was higher than those with no reported allocation challenges (11 [3-52] vs 6.5 [1-29]; P = .03). Eleven OPOs (22%) had incorporated NRP into general donor hospital education.

Conclusions

In this survey study of US OPOs, wide variation existed with respect to NRP experience and practice. Allocation challenges occurred more frequently with increased NRP experience. NRP guidelines and standardization were desired by most OPOs to decrease allocation challenges and maximize the gift of organ donation.

Introduction

The number of donation after circulatory determination of death (DCD) donors in the US has substantially increased over the last 25 years.1 Over 25% of deceased donor transplants were with DCD organs in 2023, yet DCD organ use in the US lags substantially behind that in Europe.1,2 This unrealized potential is driven by historically inferior clinical outcomes related to the warm ischemic injury inherent to the DCD process after withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy (WLST) through the “hands-off” or “no-touch” period.3,4,5 Normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) provides in-situ oxygenated, whole blood perfusion to either the thoracic and abdominal cavity (thoracoabdominal NRP [TA-NRP]) or the abdominal cavity alone (abdominal NRP [A-NRP]) after declaration of death in a DCD donor. TA-NRP and A-NRP rehabilitates the ischemic injury incurred during the dying process, results in superior outcomes after kidney and liver transplantation, and increases utilization of organs compared with super rapid recovery (SRR) and static cold storage.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 The clinical benefits of NRP are well documented, spurring increased use of NRP in the US since 2020.2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 However, a lack of consensus regarding NRP’s role in the national donation and transplantation landscape exists, resulting in nonuniform adoption and policy development among transplant centers and organ procurement organizations (OPOs).18,19,20,21 Process and implementation standardization is known to be helpful; and lack of standardization can result in patient outcome and quality of care differences.22,23 This emphasizes the need for consensus guidelines for any emerging recovery and/or perfusion technology, including NRP.

As NRP expands in the US, better understanding of the operational impact on OPOs is crucial, including relations and communication with donor hospitals and transplant centers, policy development, and consensus recommendations. Limited data have been generated to determine the association of NRP with OPOs and their integration of NRP into routine practice. Through a national survey to all 55 US OPOs performing DCD donation, information was collected to describe the end-of-2023 NRP status and identify needs surrounding NRP adoption, with the goal to determine areas where improved uniformity would facilitate increased organ availability and ultimately more life-saving transplants.2,6,16

Methods

From November 7, 2023, through December 31, 2023, the Association for Organ Procurement Organizations (AOPO) conducted a voluntary online survey of the US OPOs to assess their experience with NRP. A team of clinicians, OPO staff, and AOPO leadership with expertise in organ donation and transplantation developed the questionnaire consisting of binary, multiple-choice, and free-response questions (eTable in Supplement 1). The 46-question survey assessed the OPOs’ entire experience with NRP (regardless of when their first case occurred), barriers to NRP implementation, hospital outreach and feedback, NRP education, and challenges and opportunities related to NRP. The survey was sent to 55 of 56 OPOs; the remaining OPO was excluded as they had not participated in DCD recoveries. There were no financial incentives for OPOs to participate. This survey study follows the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline.24 The University of California San Diego institutional review board determined that this study was exempt from review and the requirement for informed consent because it represented minimal to no risk to the respondents who had voluntarily provided their OPO’s data.

Responses were collected using a secure web-based platform. OPOs were allowed 1 response from the chief executive officer (CEO), chief operating officer (COO), or medical director or chief clinical officer (CCO). Participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were ensured. Survey completion took approximately 15 minutes.

The primary outcome was to assess the number of OPOs that were actively participating in NRP programs or anticipating future NRP implementation. Secondary outcomes were identification of barriers to NRP implementation, OPO education practice patterns (internal staff, donor hospital, and family education patterns), and future needs regarding consensus NRP recommendations and standards. For ease of reporting, OPOs were categorized by the existing 11 Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Regions.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis of the data was used to identify patterns, trends, and associations among variables. Analyses were performed using Stata software 18.0 (Stata Corp) from February to April 2024. A t test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate, was used to compare continuous variables, and Fisher exact test was used to compare proportions. A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered significant.

Results

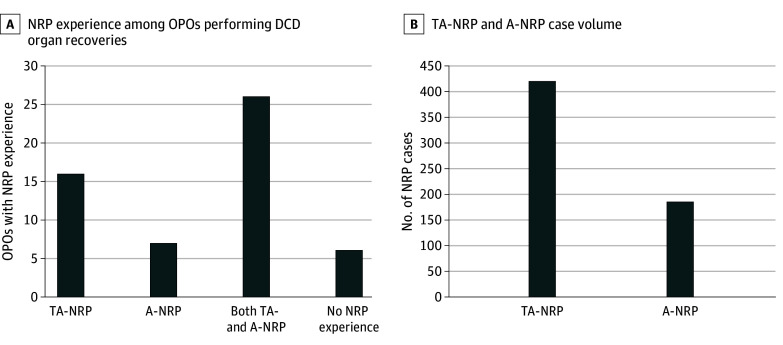

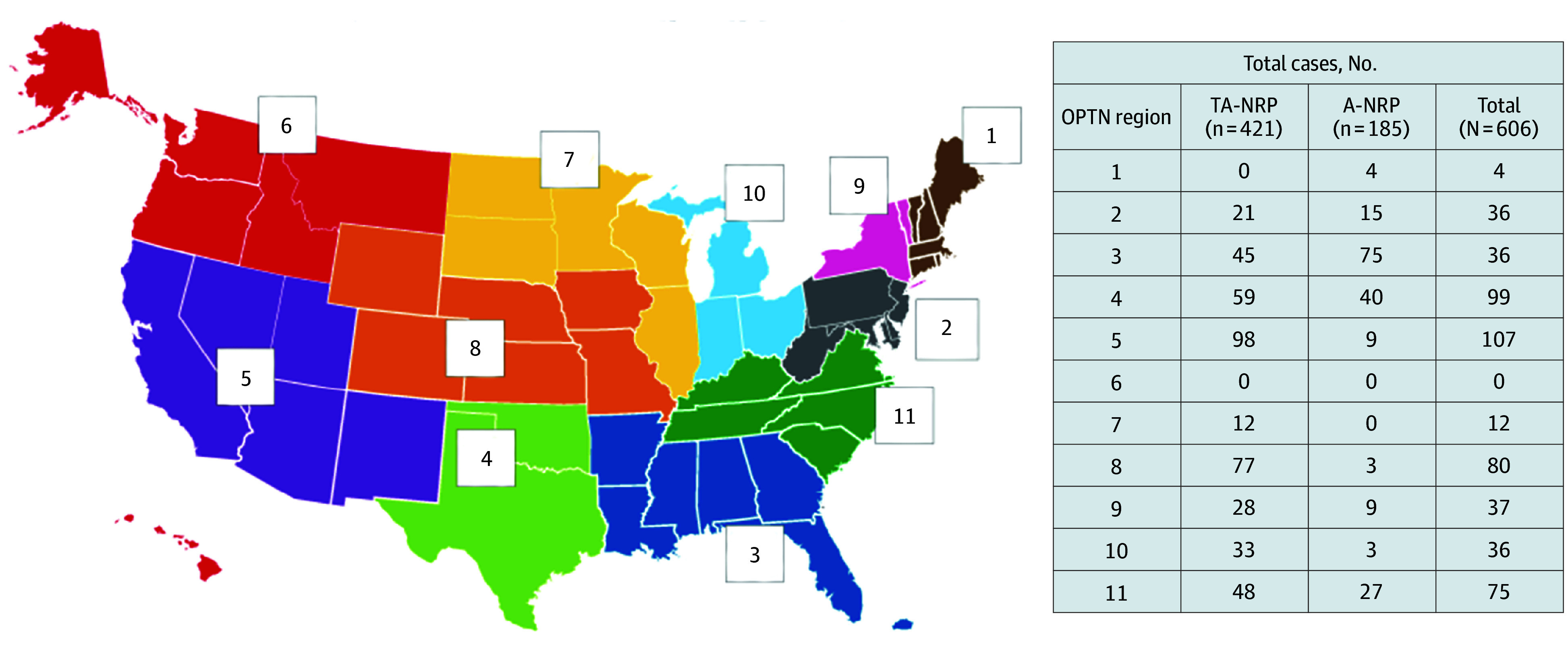

Of 55 respondents (100% response rate), 11 (20%) were CEOs, 8 (15%) were COOs, and 36 (65%) were medical directors or CCOs. Forty-nine (89%) OPOs reported NRP experience: 26 (53%) both TA-NRP and A -NRP, 16 (33%) only TA-NRP, and 7 (14%) only A-NRP cases. Six OPOs (11%) had not facilitated NRP (Figure 1A). All OPOs had facilitated NRP at the request of a transplant center; 39 of 49 (80%) had NRP cases initiated by a transplant center outside their donation service area, and 23 (47%) had facilitated NRP for a transplant center within their donation service area. In total, 49 OPOs had facilitated 606 NRP cases (421 TA-NRP [69%]; 185 A-NRP [31%]) (Figure 1B). Total cases by OPTN region are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Normothermic Regional Perfusion (NRP) Experience and Case Volume Among Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs).

NRP experience among 55 OPOs (A) and case volume among 49 OPOs with NRP experience (B). A-NRP indicates abdominal NRP; DCD, donation after circulatory determination of death; TA-NRP, thoracoabdominal NRP.

Figure 2. Normothermic Regional Perfusion (NRP) Case Volume by Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Region.

A-NRP indicates abdominal NRP; TA-NRP, thoracoabdominal NRP.

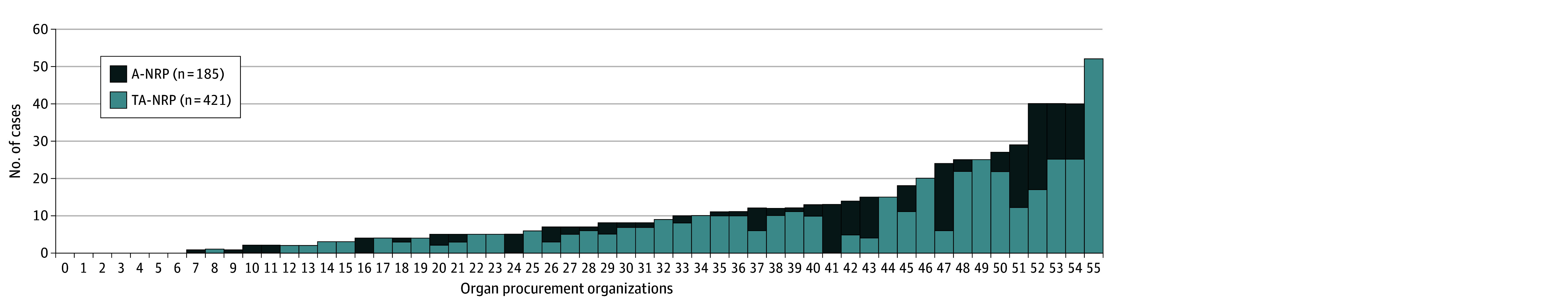

The median (range) number of NRP cases was 8 (1-52) and varied by experience with NRP case type. In the 26 OPOs with both TA-NRP and A-NRP experience, the median (range) number of total cases was 12 (1-40); the median (range) number of TA-NRP and A-NRP cases was 7 (2-25) and 3 (1-23), respectively. For the 16 OPOs with only TA-NRP experience, the median (range) number of cases was 5 (1-52), with only 1 OPO reporting more than 25 cases. In the 7 OPOs with only A-NRP experience, the median (range) number of cases was 2 (1-13), with only 1 OPO reporting more than 5 cases (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Thoracoabdominal Normothermic Regional Perfusion (TA-NRP) and Abdominal NRP (A-NRP) Case Volume per Organ Procurement Organization (Deidentified).

Desire for Guidance and/or Standardization

Fifty-two of 55 OPOs (95%), including all 6 OPOs who had not participated in NRP, reported that standardized training materials and/or resources to develop and/or refine their NRP process would be helpful. Aggregate responses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Potential Resources and OPOs Indicating a Particular Resource Would be Beneficial.

| Potential resource | OPOs indicating the resource would be helpful, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Training material for donor hospital personnel | 45 (82) |

| Workflow checklist and resource guide | 44 (80) |

| Most effective practices guidelines | 42 (76) |

| Training materials for OPO staff | 42 (76) |

| NRP language samples | 38 (69) |

| General education for nonclinical staff/social workers | 29 (53) |

| Training and/or technical details for your OPO recovery surgeons | 27 (49) |

| Consent documents for NRP | 26 (47) |

| Guide to navigating C-suitea engagement | 26 (47) |

| Training and/or technical details for local transplant center surgeon(s) | 25 (45) |

Abbreviations: NRP, normothermic regional perfusion; OPO, organ procurement organizations.

The highest-ranking executives in an organization (ie, chief-level).

OPO Policies, Barriers, and Partner Hospital Processes

An approved NRP-specific policy was reported by 21 OPOs (43%) with NRP experience; an additional 5 (10%) had a policy pending approval. Twenty-three OPOs (47%) facilitated NRP cases in the absence of an approved policy.

No barrier with partner hospitals to perform NRP were reported by 31 OPOs (63%); 18 (37%) reported that at least 1 partner hospital declined NRP participation, with a median (range) of 3 (1-19) hospitals disallowing an NRP recovery, representing up to 25% of hospitals in their donation service area. The median number of total NRP cases in OPOs reporting a barrier with partner hospitals was 13, compared with 10 for those reporting no barrier (P = .26). Cited reasons for NRP nonparticipation included ethical concerns (16 of 18 [89%]), the American College of Physicians (ACP) Statement (4 of 18 [22%]), and religious concerns (4 of 18 [22%]).18 Two of 49 OPOs (4%) reported having at least 1 hospital in their donation service area that allowed A-NRP but prohibited TA-NRP for reasons that included ethical concerns, the ACP Statement, and concerns about resources and family disclosures.18

The 6 OPOs (11%) reporting no NRP experience cited legal concerns (n = 2), ethical concerns (n = 1), the ACP Statement (n = 1), and concerns about negative public relations or media (n = 1) as barriers, with 1 OPO not providing information.18 Five of these 6 OPOs (83%) planned to perform NRP in 2024.

Hospital notification was variable: 36 OPOs (73%) with NRP experience had notified the hospital that NRP would occur, and 13 (27%) had not, citing NRP as a postmortem perfusion technique, akin to other perfusion techniques not requiring prenotification. Of the 36 OPOs that notify hospitals about NRP, 26 (72%) notified the operating room and 16 (44%) notified critical care personnel. In addition to hospital notification, 11 of 36 OPOs (31%) requested permission to perform NRP, 4 of whom had spoken with hospital ethics committees or legal teams.

Thirty-nine of 49 OPOs (80%) who had performed NRP and all 6 who had not performed NRP stated the need for standardized hospital training materials. Real-time education to involve hospital personnel on an NRP case–specific basis was provided by 31 of 49 OPOs (63%); 11 (22%) incorporated NRP information into their general donation education, and 7 (14%) had targeted specific hospitals for NRP education. Despite standard, real-time NRP education across the majority of OPOs, most OPOs (26 of 31 [84%]) had not developed specific training materials.

Most OPOs with NRP experience (29 of 49 [59%]) received positive feedback from donor hospitals on the NRP process. Two primary reasons emerged from free-text responses: (1) increased number of organs transplanted and/or lives saved and (2) increased prerecovery communication. The median (range) number of cases where OPOs received positive feedback (10 [1-52]) was not significantly different for OPOs who had not received positive feedback (7.5 [1-29]; P = .55). For OPOs that reported a negative response to the NRP process by donor hospitals, 11 OPOs (22%) cited concerns by hospital administration, 7 OPOs (14%) reported concerns by critical care personnel, and 13 OPOs (27%) cited concerns by operating room personnel. More granular detail on these negative reactions were not provided. Additional concerns from free-text responses included the requirement for packed red blood cell availability and need for intraoperative point-of-care testing (1 OPO each). At least 1 technical failure during the recovery was reported by 15 OPOs (31%); the number of failures was not queried; those reporting at least 1 technical failure facilitated a median (range) of 13 (2-52) cases compared with 7 (1-40) for those without a technical failure (P = .03).

Process and Technical Considerations for DCD Donors and Associations With NRP

Transfer of potential DCD donors to a dedicated hospital for recovery was reported by 8 of 55 OPOs (15%); 5 (9%) facilitate NRP in their dedicated hospital, and 3 (5%) OPOs transfer for the sole purpose of NRP. Fifty-two of 55 OPOs (95%) complete WLST for a potential DCD donor in the operating room. Eleven of 55 OPOs (20%) that perform DCD reported not allowing prepping and draping prior to WLST for a non-NRP donor; 10 (18%) allow prepping and draping during the 5-minute hands-off period and 3 (5%) of these allow prepping and draping prior to WLST if NRP is planned. One OPO does not prep and drape any DCD donor, regardless of NRP, until after the observation period.

Prerecovery Communication

Most OPOs (47 of 49 [96%]) perform routine prerecovery huddles after all teams arrive on-site for NRP recovery. Conducting a prearrival huddle to facilitate discussion about logistical concerns and to minimize communication gaps was reported by 38 of 49 OPOs (78%). Table 2 shows specific agenda items in this huddle and the variability to which these items were included. Twenty-one of 49 (43%) reported poor communication with the transplant center requesting and performing NRP. The median (range) number of cases for those reporting poor communication was 12 (1-52) compared with 6 (1-25) cases for those not reporting poor communication (P = .03). There was no significant association between those reporting poor communication and those who conduct a prearrival huddle.

Table 2. Discussion Items Included in Prearrival Huddle Prior to an NRP Casea.

| Discussion item | OPOs, No. (%) (N=38) |

|---|---|

| Confirm type of NRP, TA-NRP vs A-NRP | 36 (95) |

| Review 5-min hands-off period after death determined | 34 (89) |

| Review transplant team communication expectations while participating in the recovery | 34 (89) |

| Review the location of withdrawal of support (OR vs other) | 34 (89) |

| Review the need for prerecovery huddle at donor hospital | 33 (87) |

| Number of PRBCs the transplant team needs in the OR from the outset of case | 33 (87) |

| Determine each transplant team’s threshold for FWIT and associated cutoff times | 29 (76) |

| Will the patient require reintubation, and if so, what is the plan for reintubation? | 29 (76) |

| Review head vessels will be clamped in TA-NRP cases at outset of the case | 27 (71) |

| Determine if NRP will be pursued if the patient does not die within the specified timeframe for FWIT | 27 (71) |

| Review transportation needs (air/ground) for transplant teams | 25 (66) |

| Communicate the plan for prepping and draping the patient and the timing approved by the donor family | 24 (63) |

| Length of time each team wants to remain on circuit (often heart teams would prefer shorter times compared to liver teams) | 24 (63) |

| Will perfusion have additional needs (ie, oxygen tanks and vacuum lines)? | 23 (61) |

| Required laboratory tests and who will bring the POC device to obtain laboratory test results | 22 (58) |

| Will the heart team need a TEE, and if so, what is the plan for facilitating? | 22 (58) |

| If more than 1 team interested in NRP, determine who will bring the ECMO equipment/personnel | 20 (53) |

| Will the lung team need a bronchoscopy, and if so, what is the plan for facilitating? | 20 (53) |

| Will transplant teams bring their own medications (vasopressors/inotrope)? | 17 (45) |

| Will the patient come off circuit and stay off circuit after heart evaluation? Or will the patient go back on circuit? | 17 (45) |

| Consider if there are laboratory test requirements of the donor hospital that cannot be performed by transplant teams with POC device | 14 (37) |

| Other | 6 (16) |

Abbreviations: A-NRP, abdominal NRP; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FWIT, functional warm ischemic time; NRP, normothermic regional perfusion; OR, operating room; POC, point of care; TA-NRP, thoracoabdominal NRP; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram.

Prearrival huddles were conducted by 38 OPOs.

Allocation Challenges and NRP

Experiences with allocation challenges on NRP cases were reported by 22 OPOs (45%); 13 (27%) indicated that the these challenges were intermittent and easily addressed; 7 (14%) indicated that the challenges happen routinely and need to be addressed immediately; and 1 (2%) reported challenges but proceed with NRP as standard of care and do not defer to transplant centers who do not want NRP; 1 (2%) reported challenges, but they were experienced rarely and free-texted a “few instances” where a lung recovery team did not want A-NRP to be performed. Conflict resolution included holding a conference call between accepting centers (15 of 49 [31%]) and autonomous decision-making by OPO medical and/or administrative leadership (6 of 49 [12%]). Those reporting allocation challenges had facilitated a median (range) of 11 (3-52) cases, compared with 6.5 (1-29) cases for those who had not experienced these challenges (P = .03).

Having coordinated at least 1 NRP recovery when another recovery and/or perfusion modality was used was reported by 33 of 49 OPOs (67%); 16 (33%) did not have experience combining NRP with another recovery/perfusion modality. Examples cited included: TA-NRP or A-NRP and normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) of the liver (n = 28), A-NRP and SRR with or without NMP of thoracic organs (n = 20), and a combination of these additional modalities (n = 13). Allocation challenges were reported by 18 of 33 OPOs (55%) who had combined NRP with other modalities vs 4 of 16 (25%) who had not (P = .07).

Discussion

Our findings that virtually all OPOs expressed a desire for information and/or resources to develop and/or refine their NRP process should prompt action. Given the expansion of NRP across the US and our finding that the majority of OPOs have participated in NRP recoveries, it seems clear that this recovery technique will continue to be used as part of DCD donation. Recent reports show increased organ utilization from DCD donors with NRP compared with SRR in the US.6,16 Coupled with improved posttransplant outcomes seen with advanced perfusion techniques, including NRP, SRR with static cold storage of DCD organs may no longer be considered an acceptable standard of care.25 Our findings support a priority to develop standardized NRP processes, practices, procedures, policies, and training for OPOs, donor hospitals, and transplant centers. Prior dedicated process and policy implementation strategies have been successful in organ donation, and national NRP policies exist.22,23,26 As the US NRP experience is still growing, and nearly half of OPOs reported proceeding with NRP without an approved policy, standardized guidelines and policies to reduce operational heterogeneity and improve safety are desperately needed. Our data suggest standardization would decrease the likelihood of allocation challenges, complaints of poor communication, and perhaps even technical failures, as all were significantly associated with increased case volume. Positive steps toward national standardization of NRP technical and ethical standards have been taken by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS), and guidelines for the nontechnical and technical aspects of both TA-NRP and A-NRP were presented at the 2024 Developing National NRP Best Practices & Approaches Forum in Denver, Colorado.27,28,29,30,31

The variability of NRP experience and associated intercase variability will likely decrease over time. Moreover, the fact that an OPO was primarily prompted to facilitate NRP by a transplant center outside their donor service area, coupled with the fact that 69% of cases were TA-NRP, suggests a relatively small number of heart transplant centers have disproportionately driven the expansion of NRP across the US. To maximize DCD potential, OPOs will need to increase their role as primary drivers of NRP, particularly A-NRP. This would minimize variation for transplant centers traveling outside their donor service area and OPOs hosting a transplant center outside theirs.

Establishing NRP as a standard recovery technique also requires adoption at the donor hospital level, and in the present study one-third of OPOs have at least 1 partner donor hospital that will not allow for NRP for assorted reasons, including ethical and legal concerns. There are multiple ways that OPOs can collaborate with donor hospitals that have concerns with NRP. First, OPOs can share data on the widespread adoption of this technique and data that supports ethical and legal acceptability, increased organ utilization, and improved recipient outcomes.2,6,7,9,11,13,14,15,16,20,21,32 Second, OPOs can engage donor hospitals in policy development to allow them to develop protocols that are acceptable within their ethical, religious, and legal frameworks, as has been done with the development of DCD. However, this may lead to a patchwork of confusing policies around NRP, emphasizing the need for fundamental consensus recommendations to guide donor hospital policy development. Third, OPOs can offer the transfer of donors to hospitals that allow NRP so donor hospitals do not have to participate. In the current study, 15% of centers routinely transfer DCD donors, with 3 OPOs citing facilitation of NRP recovery as the sole purpose of transfer. Transfer of the donor to a location specializing in NRP recovery has been advocated.17 Suggested benefits include: (1) standardized method of organ reperfusion to ensure safety and reproducibility; (2) reduced subjective variability in organ assessment for transplant suitability; (3) standardized WLST by dedicated intensive care unit physicians and staff who understand the process; and (4) focused expertise in a single location with multiple experienced teams in cardiothoracic surgery, cardiology, critical care, anesthesiology, and abdominal transplant surgery.

Communication around the donor operation and associated logistics is paramount in all organ recoveries. Novel perfusion technology adds a new component to this communication. One of the ethical challenges with NRP is that it can create allocation disputes that are not currently clarified in allocation policy. For example, an abdominal team may want to use NRP for the liver, and the thoracic team might want SRR for the lungs. Dual recovery procedures are possible and have been shown to have excellent liver and thoracic outcomes,33 but not all transplant and recovery surgeons are familiar with these procedures. Therefore, OPOs are asked to decide which recovery technique or recipient should take priority. As NRP expands further, our data suggest that these conflicts will be more frequent, emphasizing the need for OPOs to have policies to resolve these conflicts.

Limitations

This study has limitations. These data represent a prior snapshot in a rapidly evolving field and, thus, do not capture the current state of NRP in the US. Limited experience by some OPOs may have reduced their ability to sufficiently answer survey-specific items. Given the intent and nature of the survey, we did not capture granularity on the specifics of allocation changes or technical failure; these merit further investigation. Additionally, the individuals surveyed may not have been present at or involved in all NRP-related cases, limiting their ability to definitely assess positive and negative implications of NRP.

Conclusions

This survey study of NRP recovery in the US highlighted the need for national standards to ensure quality and preserve public trust in organ donation. While some degree of variability is inevitable, data suggested most OPOs desire and need standardized guidelines to direct NRP protocol development.

eTable. Survey Questions

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . National data. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/build-advanced/

- 2.Eden J, Sousa Da Silva R, Cortes-Cerisuelo M, et al. Utilization of livers donated after circulatory death for transplantation - an international comparison. J Hepatol. 2023;78(5):1007-1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foley DP, Fernandez LA, Leverson G, et al. Donation after cardiac death: the University of Wisconsin experience with liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2005;242(5):724-731. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000186178.07110.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jay C, Ladner D, Wang E, et al. A comprehensive risk assessment of mortality following donation after cardiac death liver transplant - an analysis of the national registry. J Hepatol. 2011;55(4):808-813. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skaro AI, Jay CL, Baker TB, et al. The impact of ischemic cholangiopathy in liver transplantation using donors after cardiac death: the untold story. Surgery. 2009;146(4):543-552. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekki Y, Croome KP, Myers B, Sasaki K, Tomiyama K. Normothermic regional perfusion can improve both utilization and outcomes in DCD liver, kidney, and pancreas transplantation. Transplant Direct. 2023;9(3):e1450. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brubaker AL, Sellers MT, Abt PL, et al. US liver transplant outcomes after normothermic regional perfusion vs standard super rapid recovery. JAMA Surg. 2024;159(6):677-685. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.0520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croome KP, Brown TE, Mabrey RL, et al. Development of a portable abdominal normothermic regional perfusion (A-NRP) program in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2023;29(12):1282-1291. doi: 10.1097/LVT.0000000000000156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hessheimer AJ, de la Rosa G, Gastaca M, et al. Abdominal normothermic regional perfusion in controlled donation after circulatory determination of death liver transplantation: outcomes and risk factors for graft loss. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(4):1169-1181. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman JRH, McMaster WG, Rali AS, et al. Early US experience with cardiac donation after circulatory death (DCD) using normothermic regional perfusion. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(11):1408-1418. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oniscu GC, Mehew J, Butler AJ, et al. Improved organ utilization and better transplant outcomes with in situ normothermic regional perfusion in controlled donation after circulatory death. Transplantation. 2023;107(2):438-448. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellers MT, Nassar A, Alebrahim M, et al. Early United States experience with liver donation after circulatory determination of death using thoraco-abdominal normothermic regional perfusion: a multi-institutional observational study. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(6):e14659. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merani S, Urban M, Westphal SG, et al. Improved early post-transplant outcomes and organ use in kidney transplant using normothermic regional perfusion for donation after circulatory death: national experience in the US. J Am Coll Surg. 2024;238(1):107-118. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wall A, Gupta A, Testa G. Abdominal normothermic regional perfusion in the United States: current state and future directions. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2024;29(3):175-179. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000001144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou AL, Leng A, Ruck JM, Akbar AF, Desai NM, King EA. Kidney donation after circulatory death using thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion: the largest report of the United States experience. Transplantation. 2024;108(2):516-523. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakhtiyar SS, Maksimuk TE, Gutowski J, et al. Association of procurement technique with organ yield and cost following donation after circulatory death. Am J Transplant. Published online March 21, 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.ajt.2024.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James L, LaSala VR, Hill F, et al. Donation after circulatory death heart transplantation using normothermic regional perfusion: the NYU protocol. JTCVS Tech. 2022;17:111-120. doi: 10.1016/j.xjtc.2022.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ACP . Ethics, Determination of Death, and Organ Transplantation in Normothermic Regional Perfusion (NRP) with Controlled Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (cDCD): American College of Physicians Statement of Concern. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://www.acponline.org/sites/default/files/documents/clinical_information/resources/end_of_life_care/ethics_determination_of_death_and_organ_transplantation_in_nrp_2021.pdf

- 19.Glazier AK, Capron AM. Normothermic regional perfusion and US legal standards for determining death are not aligned. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(5):1289-1290. doi: 10.1111/ajt.17002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parent B, Caplan A, Moazami N, Montgomery RA. Response to American College of Physician’s statement on the ethics of transplant after normothermic regional perfusion. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(5):1307-1310. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wall AE, Fiedler A, Karp S, Shah A, Testa G. Applying the ethical framework for donation after circulatory death to thoracic normothermic regional perfusion procedures. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(5):1311-1315. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Realizing the Promise of Equity in the Organ Transplantation System. Published February 25, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35226429 [PubMed]

- 23.Rosendale JD, Chabalewski FL, McBride MA, et al. Increased transplanted organs from the use of a standardized donor management protocol. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(8):761-768. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) . Best practices for survey research. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://aapor.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Survey-Best-Practices.pdf

- 25.Croome KP. Should advanced perfusion be the standard of care for donation after circulatory death liver transplant? Am J Transplant. 2024;24(7):1127-1131. doi: 10.1016/j.ajt.2024.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson C. UK protocol for normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) in controlled donation after circulatory determination of death. Novel Technologies Implementation Group. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/34337/uk-protocol-for-normothermic-regional-perfusion.pdf

- 27.Wall AE, Adams BL, Brubaker A, et al. The American Society of Transplant Surgeons consensus statement on normothermic regional perfusion. Transplantation. 2024;108(2):312-318. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croome K, Bababekov Y, Brubaker A, et al. American Society of Transplant Surgeons normothermic regional perfusion standards: abdominal. Transplantation. 2024;108(8):1660-1668. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000005114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffman JRH, Hartwig MG, Cain MT, et al. ; In collaboration with members from The American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS), The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT), The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), and The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) . Consensus statement: technical standards for thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion. Transplantation. 2024;108(8):1669-1680. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000005101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wall AE, Merani S, Batten J, et al. American Society of Transplant Surgeons normothermic regional perfusion standards: ethical, legal, and operational conformance. Transplantation. 2024;108(8):1655-1659. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000005115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Developing National NRP Best Practices & Approaches Forum . Accessed April 2, 2024. https://www.organdonationalliance.org/events/2024-national-collaboration-forum/

- 32.Adams BL, Brenner L, Levan M, Parent B. cDCDD-NRP is consistent with US legal standards for determining death. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(10):2302-2305. doi: 10.1111/ajt.17083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campo-Cañaveral de la Cruz JL, Miñambres E, Coll E, et al. Outcomes of lung and liver transplantation after simultaneous recovery using abdominal normothermic regional perfusion in donors after the circulatory determination of death versus donors after brain death. Am J Transplant. 2023;23(7):996-1008. doi: 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Survey Questions

Data Sharing Statement