RESUMEN

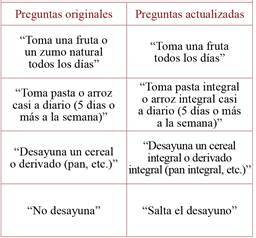

El cuestionario KIDMED ha sido utilizado desde 2004 para evaluar la adherencia a la dieta mediterránea de niños y adolescentes. Desde entonces, ha habido un cambio de paradigma en referencia al consumo diario de zumos de fruta y al consumo de cereales integrales. Proponemos una actualización del cuestionario KIDMED en lengua española. En la primera pregunta se propone quitar la expresión “o un zumo natural”. En la octava pregunta se añade el término “integral” al consumo diario de pasta y arroz. En la novena pregunta se añade el término “integral” al consumo de cereales y derivados en el desayuno. En la duodécima pregunta se propone la siguiente reformulación: “Salta el desayuno”. Con este trabajo se proponen algunas modificaciones al cuestionario KIDMED en lengua española, con el fin de suministrar una herramienta conforme a las nuevas recomendaciones que se han ido implementando en los últimos años para poder considerar si una dieta es correcta en niños y adolescentes.

Palabras clave: KIDMED , Adherencia a la dieta, Dieta mediterránea, Cuestionario, Niños, Adolescentes, Zumos de fruta, Cereales integrales

ABSTRACT

Since 2004 the KIDMED questionnaire has been used to evaluate adherence to the mediterranean diet in children and adolescents. During the last decade, there was a paradigm shift about the daily consumption of fruit juice and whole grains. These changes have led to an update of the KIDMED questionnaire in English. We propose an update of the spanish version of the KIDMED questionnaire. We propose deleting ‘or fruit juice’ from the first question. In the eighth question we propose adding ‘whole-grain’ to the daily consumption of pasta and rice. In the ninth question, we propose adding ‘whole cereals or whole grains’ to the consumption of cereals or grain over breakfast. The twelfth question is reformulated as: “Skips breakfast”. We propose some modifications to the spanish version KIDMED questionnaire to provide a tool according to the new recommendations for a healthy diet in children and adolescents.

Key words: KIDMED , Adherence to the diet, Mediterranean diet, Questionnaire, Children, Adolescents, Fruit juice, Whole grains

INTRODUCCIÓN

El cuestionario KIDMED ha sido utilizado durante más de una década por nutricionistas, investigadores, endocrinólogos, profesionales sanitarios y estudiantes para evaluar la adherencia a la dieta mediterránea (DM) de niños y adolescentes. El cuestionario KIDMED en lengua inglesa fue publicado en 2004 1 . Los autores publicaron ese mismo año el cuestionario KIDMED en lengua española( 2 . Recientemente han realizado un análisis de los cambios ocurridos en la evidencia científica a lo largo de los últimos 15 años, y han propuesto una actualización del cuestionario KIDMED en lengua inglesa 3 . Posteriormente, se han llevado a cabo una gran cantidad de trabajos científicos sobre adherencia a la DM de niños y adolescentes hispanohablantes con el cuestionario KIDMED del 2004 4 , 5 , 6 . El cuestionario KIDMED ha sido utilizado para medir la adherencia a la dieta mediterránea en España como en varios países hispanohablantes de Latinoamérica 7 , 8 . El objetivo de este trabajo fue proponer unas modificaciones al cuestionario KIDMED del 2004 en lengua española, conforme a las últimas actualizaciones científicas.

Tabla 1. Resumen de los cambios propuestos.

MODIFICACIONES Y DISCUSIÓN

Proponemos una actualización del cuestionario con algunas modificaciones en la primera, octava, novena y duodécima pregunta del KIDMED en lengua española.

Primera pregunta

Una respuesta positiva (Sí) a la pregunta “Toma una fruta o un zumo natural todos los días” asigna una puntuación de +1. Esta primera pregunta propone una equivalencia entre la fruta y el zumo natural de fruta. La investigación más reciente pone en duda este principio y la actual formulación de la primera pregunta. No deberíamos considerar la toma de zumo de fruta como un hábito diario necesario y saludable. La zumos de fruta pueden conllevar una mayor ingesta calórica diaria en comparación con la fruta entera 9 . El consumo de zumos de fruta no previene la diabetes tipo 2 10 , 11 , ni previene la obesidad 12 , 13 , 14 . Sin embargo, el consumo de fruta disminuye el riesgo de ambas enfermedades 10 , 11 , 15 . Cualquier tipo de bebida a base de fruta, zumos de fruta o exprimido de fruta contiene al menos 50 Kcal por cada vaso de poco más de 200 mL. El debate a favor y en contra sobre el consumo diario de zumo de fruta 100% es amplio en la literatura(13,16,17,18,19,20), aunque hay que recordar que un vaso de 230 mL de zumo de naranja aporta más de 50 kcal 12 . La cantidad de fibra contenida en los zumos 100% es mínima 21 y equivale aproximadamente al 10% de la cantidad contenida en la propia fruta 19 . Además, debido a la percepción de ser productos saludables que acompaña los zumos 100%, podría dar lugar a un consumo rutinario y excesivo de éstos 19 . Entre los argumentos a favor del consumo diario de zumos de fruta 100% está el aporte de vitamina C, folatos y potasio 22 . A día de hoy, no se reportan mayores prevalencias o incidencias de enfermedades relacionadas con estas sustancias en niños y adolescentes. Sin embargo, la obesidad infantojuvenil y las enfermedades crónicas que se pueden fomentar posteriormente en la edad adulta se consideran un problema de salud pública en todos los países desarrollados y en vías de desarrollo 23 .

El consumo de bebidas azucaradas, zumos en todas sus formas, bebidas energéticas, café, té azucarado y cualquier combinación entre ellos, es alto y resulta probable que siga aumentando en los años venideros. El consumo de bebidas azucaradas y zumos es la mayor fuente de líquidos ingeridos en Estados Unidos 24 y es probable que esta tendencia se concrete pronto en Europa, desplazando al agua como la bebida habitual 19 , 20 , 23 . La Organización Mundial de la Salud propuso que también los zumos de frutas deberían ser incluidos en la política de impuestos sobre las bebidas azucaradas 25 . Además, los niños y los adolescentes son grandes consumidores de zumos de fruta y no distinguen las diferencias entre un zumo de fruta 100% u otra bebida a base de zumo con el 15% de fruta. Ellos solo consideran que beben un zumo de fruta.

Muchas guías alimentarias internacionales han incluido el consumo de fruta natural, en lugar del zumo de fruta, entre los hábitos saludables 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 . La fruta entera contiene menos calorías por ración, produce mayor saciedad, tiene mayor densidad nutricional y un perfil de nutrientes más beneficioso respeto a cualquier tipo de zumo de fruta 13 , 30 . Un aumento del consumo de fruta y de agua, en lugar de zumos de fruta, podría ayudar a la pérdida de peso en las poblaciones a las cuales el cuestionario KIDMED está dirigido 15 , 31 , 32 . Proponemos eliminar la expresión “o un zumo natural” de la primera pregunta del KIDMED y reformular la pregunta de la siguiente manera: “Toma una fruta todos los días”. Se le otorgaría el valor de +1 (tabla 2). De esta manera, consideramos la toma diaria de fruta como un hábito saludable dentro del marco de la DM. Además, con esta pequeña modificación, la primera pregunta se enlaza coherentemente con la segunda.

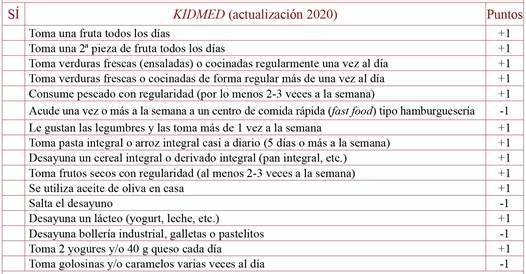

Tabla 2. Actualización del KIDMED, índice de calidad de la dieta mediterránea en la infancia y la adolescencia.

Valor del índice KIDMED: ≤ 3, Dieta de muy baja calidad; 4 a 7: Necesidad de mejorar el patrón alimentario para ajustarlo al modelo Mediterráneo; ≥ 8: Dieta Mediterránea óptima.

Octava pregunta

Una respuesta positiva (Sí) a la octava pregunta “Toma pasta o arroz casi a diario (5 días o más a la semana)” asigna una puntuación de +1. Los cereales refinados como la pasta y el arroz blanco no deberían considerarse como alimentos básicos para la DM. Históricamente, los habitantes de la zona mediterránea comían cereales integrales en lugar de cereales refinados. La ciencia ha investigado las consecuencias del consumo de cereales refinados e integrales sobre muchas enfermedades crónicas 33 , 34 , 35 . Otros estudios han investigado el impacto del consumo de carbohidratos y fibra dietética sobre enfermedades como la diabetes y la obesidad 36 , 37 . El cambio de paradigma ocurrido en los últimas décadas ha llevado a varios países a fomentar el consumo de cereales integrales en lugar de cereales refinados 38 , 39 , 40 . El Fondo mundial para la investigación contra el cáncer aconseja consumir cereales integrales para la prevención de esta enfermedad 41 . El Plato Saludable de Harvard declara desde 2011 que la mayoría de los carbohidratos deberían ser consumidos en su forma “integral” 26 . En la pregunta se hace referencia al consumo diario de arroz y pasta. El arroz blanco contiene principalmente almidón (70-80%), proteínas (7-10%) y una pequeña cantidad de lípidos (<1%) 42 . El arroz blanco tiene una carga y un índice glicémico más alto que el arroz integral 43 . El arroz integral no pasa por el proceso de descascarillado y, por ende, es más rico en nutrientes, contiene más fibra dietética, lípidos, minerales, vitaminas, micronutrientes y compuestos bioactivos. La sustitución del arroz blanco por arroz integral podría facilitar la prevención de la diabetes tipo 2 y ayudar con otras enfermedades relacionadas con la alimentación 27 . La pasta es un “típico” plato italiano con un bajo índice glucémico 44 y su consumo se ha expandido en todo el Mediterráneo. La pasta parece ofrecer más beneficios respecto a otros carbohidratos refinados 45 . Aún así, aumentar el consumo de pasta integral enriquecería la densidad nutricional de este alimento y aumentaría el consumo de fibra dietética. Además, la promoción de la pasta y el arroz integral como alimentos más saludables podría implementar la transición hacía platos más beneficiosos para la salud 46 .

Proponemos añadir el término “integral” al consumo diario de pasta y arroz, y otorgarle el valor de +1 (tabla 2). De esta manera, quedaría reformulada la pregunta de la siguiente manera: “Toma pasta integral o arroz integral casi a diario (5 días o más a la semana)”. Así, consideramos el consumo de cereales integrales (arroz y pasta) como un hábito alimentario saludable dentro del marco de la DM.

Novena pregunta

Una respuesta positiva (Sí) a la novena pregunta “Desayuna un cereal o derivado (pan, etc.)” asigna una puntuación de +1. Estando el cuestionario dirigido a niños y adolescentes, la locución “desayuna un cereal” parece poco apropiada, porque podría malentenderse y asociarse a los “cereales para el desayuno”. La ingesta de estos cereales “listos para comer” en el desayuno ha aumentado en los últimos años 47 , 48 . A día de hoy, gracias a eficaces campañas de mercadotecnia, son uno de los alimentos más consumidos en el desayuno entre los niños y adolescentes 48 . Desafortunadamente, estos productos son ricos en azucares añadidos y no pueden enmarcarse en un patrón de DM, y tampoco pueden considerarse alimentos saludables 48 , 49 . Los cereales refinados, como el pan blanco, normalmente tienen una alta carga glucémica y poca densidad nutricional. Los cereales integrales son ricos en vitaminas, minerales, compuestos fenólicos y antioxidantes 50 , 51 . Los cereales y derivados como el pan consumidos en su forma “integral” son nutricionalmente más ricos y aportan más fibra dietética 52 , beneficiosa en respuesta glucémica postprandial. La fibra dietética puede tener un efecto protector frente a cánceres del sistema digestivo 53 . Además, el aumento en la ingesta de fibra es beneficioso en adolescentes 54 .

Por estos motivos, proponemos añadir el término “integral” al consumo de cereales y derivados en el desayuno. La pregunta quedaría reformulada de la siguiente manera: “Desayuna un cereal integral o derivado integral (pan integral, etc.)”. Se le otorgaría el valor de +1 (tabla 2). De esta manera, consideramos el consumo de cereales integrales en el desayuno como un hábito alimentario saludable dentro del marco de la DM.

Duodécima pregunta

Una respuesta positiva (Sí) a la duodécima pregunta “No desayuna” asigna una puntuación de -1. El cuestionario KIDMED está dirigido a niños y adolescentes y, entre las normas generales a respetar en los métodos de investigación clínica y epidemiológica, está la de no formular las preguntas de forma negativa, ya que pueden conducir a doble interpretaciones 55 . Además, en base a nuestra experiencia con este cuestionario, las preguntas con interrogativas negativas en niños y adolescentes pueden crear problemas de comprensión y dudas en la respuesta. Por este motivo, proponemos reformular la pregunta de la siguiente manera: “Salta el desayuno”. Se le otorgaría el valor de -1 a la respuesta positiva (tabla 2). Creemos que el cambio en la pregunta duodécima conllevará una mejor comprensión de la misma y evitará puntualizaciones por parte del personal investigador. Además, esta modificación es conforme a la pregunta duodécima del KIDMED en lengua inglesa 3 .

Consideramos útil recoger estos cambios de paradigma en el cuestionario más utilizado a nivel mundial para medir la adherencia a la dieta mediterránea de niños y adolescentes hispanohablantes. Con esta actualización, evitamos traducciones arbitrarias por parte del personal investigador y proponemos un cuestionario que pueda ser utilizado en los países hispanohablantes.

LIMITACIONES DEL ESTUDIO

El trabajo es una propuesta argumentada de actualización del KIDMED, en lengua española, en base a la literatura científica de los últimos 15 años. Por ende, no hemos llevado a cabo un estudio epidemiológico que sustente los cambios propuestos. Creemos que los investigadores que quieran aplicar esta nueva propuesta al contexto de Latinoamérica deberían considerar si es necesaria una adaptación cultural a su contexto. No descartamos que las modificaciones puedan conllevar cambios en la puntuación del KIDMED y su interpretación. Esta es una limitación que futuros trabajos con esta nueva propuesta podrán esclarecer.

CONCLUSIONES

En esta propuesta de actualización del cuestionario KIDMED se ponen de manifiesto los principales cambios de paradigma científico sobre el consumo de zumos de fruta y de cereales integrales. Con este trabajo se persigue respetar las nuevas recomendaciones que se han ido implementando a nivel internacional para poder considerar si una dieta es correcta en niños y adolescentes. En conclusión, los cambios propuestos actualizan el cuestionario KIDMED en lengua española publicado en 2004, con el fin de suministrar un cuestionario conforme a los cambios de paradigmas ocurridos.

Cita sugerida: Altavilla C, Comeche JM, Comino Comino I, Caballero Pérez P. El índice de calidad de la dieta mediterránea en la infancia y la adolescencia (KIDMED). Propuesta de actualización para países hispano hablantes. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2020; 94: 19 de junio e202006057

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

- 1.. Serra-Majem L, Ribas L, Ngo J, et al. (2004) Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 7, 931-935. [DOI] [PubMed]; Serra-Majem L, Ribas L, Ngo J, et al. Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:931–935. doi: 10.1079/phn2004556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.. Serra Majem LA, J B (2004) Alimentación, jóvenes y dieta mediterránea en España. Desarrollo del KIDMED, índice de calidad de la dieta mediterranea en la infancia y la adolescencia. In Aliment. Infant. y Juv., pp. 51-59 (Masson, editor).; Serra Majem LA, J B. Alimentación, jóvenes y dieta mediterránea en España. Desarrollo del KIDMED, índice de calidad de la dieta mediterranea en la infancia y la adolescencia. In Aliment. Infant. y Juv. 2004:51–59. Masson, editor. [Google Scholar]

- 3.. Altavilla C, Caballero-Perez P. (2019) An update of the KIDMED questionnaire, a Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Altavilla C, Caballero-Perez P. An update of the KIDMED questionnaire, a Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22 doi: 10.1017/S1368980019001058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.. Galan-Lopez P, Sanchez-Oliver AJ, Pihu M, et al. (2019) Association between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Physical Fitness with Body Composition Parameters in 1717 European Adolescents: The AdolesHealth Study. Nutrients 12, 77. MDPI AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Galan-Lopez P, Sanchez-Oliver AJ, Pihu M, et al. Association between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Physical Fitness with Body Composition Parameters in 1717 European Adolescents: The AdolesHealth Study. Nutrients . 2019;12(77) doi: 10.3390/nu12010077. MDPI AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.. Arcila-Agudelo AM, Ferrer-Svoboda C, Torres-Fernàndez T, et al. (2019) Determinants of Adherence to Healthy Eating Patterns in a Population of Children and Adolescents: Evidence on the Mediterranean Diet in the City of Mataró (Catalonia, Spain). Nutrients 11. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Arcila-Agudelo AM, Ferrer-Svoboda C, Torres-Fernàndez T, et al. Nutrients . Vol. 11. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2019. Determinants of Adherence to Healthy Eating Patterns in a Population of Children and Adolescents: Evidence on the Mediterranean Diet in the City of Mataró (Catalonia, Spain). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.. Morales-Suarez-Varela M, Peraita-Costa I, Guillamon Escudero C, et al. (2019) Total body skeletal muscle mass and diet in children aged 6-8 years: ANIVA Study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 44, 944-951. NRC Research Press. [DOI] [PubMed]; Morales-Suarez-Varela M, Peraita-Costa I, Guillamon Escudero C, et al. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Vol. 44. NRC Research Press; 2019. Total body skeletal muscle mass and diet in children aged 6-8 years: ANIVA Study; pp. 944–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.. Garcia-Hermoso A, Vegas-Heredia ED, Fernández-Vergara O, et al. (2019) Independent and combined effects of handgrip strength and adherence to a Mediterranean diet on blood pressure in Chilean children. Nutrition 60, 170-174. [DOI] [PubMed]; Garcia-Hermoso A, Vegas-Heredia ED, Fernández-Vergara O, et al. Independent and combined effects of handgrip strength and adherence to a Mediterranean diet on blood pressure in Chilean children. Nutrition . 2019;60:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.. Agostinis-Sobrinho C, Ramírez-Vélez R, García-Hermoso A, et al. (2019) The combined association of adherence to Mediterranean diet, muscular and cardiorespiratory fitness on low-grade inflammation in adolescents: a pooled analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 58, 2649-2656. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [DOI] [PubMed]; Agostinis-Sobrinho C, Ramírez-Vélez R, García-Hermoso A, et al. Eur. J. Nutr. Vol. 58. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2019. The combined association of adherence to Mediterranean diet, muscular and cardiorespiratory fitness on low-grade inflammation in adolescents: a pooled analysis; pp. 2649–2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.. Houchins JA, Tan SY, Campbell WW, et al. (2013) Effects of fruit and vegetable, consumed in solid vs beverage forms, on acute and chronic appetitive responses in lean and obese adults. Int. J. Obes. 37, 1109-1115. NIH Public Access. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Houchins JA, Tan SY, Campbell WW, et al. Int. J. Obes. Vol. 37. NIH Public Access; 2013. Effects of fruit and vegetable, consumed in solid vs beverage forms, on acute and chronic appetitive responses in lean and obese adults; pp. 1109–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.. Wang PY, Fang JC, Gao ZH, et al. (2016) Higher intake of fruits, vegetables or their fiber reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig 7, 56-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Wang PY, Fang JC, Gao ZH, et al. Higher intake of fruits, vegetables or their fiber reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig . 2016;7:56–69. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.. Imamura F, O'Connor L, Ye Z, et al. (2016) Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. Br. J. Sports Med. 50, 496-504. BMJ Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Imamura F, O'Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Br. J. Sports Med. Vol. 50. BMJ Publishing Group; 2016. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction; pp. 496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.. Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, et al. (2015) Global, Regional, and National Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Fruit Juices, and Milk: A Systematic Assessment of Beverage Intake in 187 Countries. PLoS One 10, e0124845 (Müller M, editor). Public Library of Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, et al. PLoS One. e0124845. Vol. 10. Public Library of Science; 2015. Global, Regional, and National Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Fruit Juices, and Milk: A Systematic Assessment of Beverage Intake in 187 Countries. (Müller M, editor) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.. Wojcicki JM, Heyman MB (2012) Reducing childhood obesity by eliminating 100% fruit juice. Am. J. Public Health 102, 1630-3. American Public Health Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Wojcicki JM, Heyman MB. Am. J. Public Health . Vol. 102. American Public Health Association; 2012. Reducing childhood obesity by eliminating 100% fruit juice; pp. 1630–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.. Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, et al. (2015) Estimated Global, Regional, and National Disease Burdens Related to Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in 2010. Circulation 132, 639-66. American Heart Association, Inc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, et al. Circulation. Vol. 132. American Heart Association, Inc; 2015. Estimated Global, Regional, and National Disease Burdens Related to Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in 2010; pp. 639–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.. Sharma SP, Chung HJ, Kim HJ, et al. (2016) Paradoxical Effects of Fruit on Obesity. Nutrients 8. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Sharma SP, Chung HJ, Kim HJ, et al. Nutrients . Vol. 8. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2016. Paradoxical Effects of Fruit on Obesity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.. Heyman MB, Abrams SA (2017) Fruit Juice in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Current Recommendations. Pediatrics 139, e20170967. American Academy of Pediatrics. [DOI] [PubMed]; Heyman MB, Abrams SA. Pediatrics. Vol. 139. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017. Fruit Juice in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Current Recommendations. (e20170967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.. Lamport DJ, Saunders C, Butler LT, et al. (2014) Fruits, vegetables, 100% juices, and cognitive function. Nutr. Rev. 72, 774-789. [DOI] [PubMed]; Lamport DJ, Saunders C, Butler LT, et al. Fruits, vegetables, 100% juices, and cognitive function. Nutr. Rev. 2014;72:774–789. doi: 10.1111/nure.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.. Clemens R, Drewnowski A, Ferruzzi MG, et al. (2015) Squeezing fact from fiction about 100% fruit juice. Adv. Nutr. 6, 236S-243S. American Society for Nutrition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Clemens R, Drewnowski A, Ferruzzi MG, et al. Adv. Nutr. Vol. 6. American Society for Nutrition; 2015. Squeezing fact from fiction about 100% fruit juice; pp. 236S–243S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.. Rodríguez Delgado J, Hoyos Vázquez M (2017) Los zumos de frutas y su papel en la alimentación infantil. ¿Debemos considerarlos como una bebida azucarada más? Posicionamiento del Grupo de Gastroenterología y Nutrición de la AEPap. Rev. Pediatría Atención Primaria 19, 2.; Rodríguez Delgado J, Hoyos Vázquez M. Los zumos de frutas y su papel en la alimentación infantil. ¿Debemos considerarlos como una bebida azucarada más? Posicionamiento del Grupo de Gastroenterología y Nutrición de la AEPap. Rev. Pediatría Atención Primaria . 2017;19(2) [Google Scholar]

- 20.. Gill JMR, Sattar N (2014) Fruit juice: Just another sugary drink? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol., 444-446. Elsevier Limited. [DOI] [PubMed]; Gill JMR, Sattar N. Endocrinol. Elsevier Limited; 2014. Fruit juice: Just another sugary drink? Lancet Diabetes; pp. 444–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.. USDA USDA Food Composition Databases. https://www.nal.usda.gov/sites/www.nal.usda.gov/files/total_dietary_fiber.pdf.; USDA USDA Food Composition Databases. https://www.nal.usda.gov/sites/www.nal.usda.gov/files/total_dietary_fiber.pdf

- 22.. Byrd-Bredbenner C, Ferruzzi MG, Fulgoni VL, et al. (2017) Satisfying America's Fruit Gap: Summary of an Expert Roundtable on the Role of 100% Fruit Juice. J. Food Sci. 82, 1523-1534. Blackwell Publishing Inc. [DOI] [PubMed]; Byrd-Bredbenner C, Ferruzzi MG, Fulgoni VL, et al. J. Food Sci. Vol. 82. Blackwell Publishing Inc; 2017. Satisfying America's Fruit Gap: Summary of an Expert Roundtable on the Role of 100% Fruit Juice; pp. 1523–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.. OECD Directorate for Employment & Labour and Social Affair (2014) OBESITY Update.; OECD . Directorate for Employment & Labour and Social Affair . OBESITY Update; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.. Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, et al. (2009) Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988-1994 to 1999-2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 372-381. Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PubMed]; Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, et al. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. Vol. 89. Oxford University Press; 2009. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988-1994 to 1999-2004; pp. 372–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.. WHO (2015) Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases.; WHO . Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.. Harvard TH. Chan School of Public Health (2011) Healthy Eating Plate & Healthy Eating Pyramid | The Nutrition Source | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-eating-plate/.; Harvard TH . Healthy Eating Plate & Healthy Eating Pyramid | The Nutrition Source . Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; 2011. Chan School of Public Health .https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-eating-plate/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.. World Cancer Research Fund (2017) Plant foods.; World Cancer Research Fund . Plant foods. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.. Dolan E, Deb S, Stephen G, et al. (2016) Brief communication: Self-reported health and activity habits and attitudes in saturation divers. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 43, 93-101. United States. [PubMed]; Dolan E, Deb S, Stephen G, et al. Undersea Hyperb. Med. Vol. 43. United States: 2016. Brief communication: Self-reported health and activity habits and attitudes in saturation divers; pp. 93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.. World Health Organization. Nutrition for Health and Development (2015) Guideline. Sugars intake for adults and children. [PubMed]; World Health Organization Nutrition for Health and Development. Guideline. Sugars intake for adults and children. 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.. Flood-Obbagy JE, Rolls BJ (2009) The effect of fruit in different forms on energy intake and satiety at a meal. Appetite 52, 416-22. NIH Public Access. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Flood-Obbagy JE, Rolls BJ. Appetite . Vol. 52. NIH Public Access; 2009. The effect of fruit in different forms on energy intake and satiety at a meal; pp. 416–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.. Fresán U, Gea A, Bes-Rastrollo M, et al. (2016) Substitution Models of Water for Other Beverages, and the Incidence of Obesity and Weight Gain in the SUN Cohort. Nutrients 8. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Fresán U, Gea A, Bes-Rastrollo M, et al. Nutrients . Vol. 8. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2016. Substitution Models of Water for Other Beverages, and the Incidence of Obesity and Weight Gain in the SUN Cohort. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.. Russell W, Duthie G (2011) Plant secondary metabolites and gut health: the case for phenolic acids. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 70, 389-396. England. [DOI] [PubMed]; Russell W, Duthie G. Proc. Nutr. Soc. Vol. 70. England: 2011. Plant secondary metabolites and gut health: the case for phenolic acids; pp. 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.. Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, et al. (2016) Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 353, i2716. BMJ Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, et al. BMJ . i2716. Vol. 353. BMJ Publishing Group; 2016. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.. Zong G, Gao A, Hu FB, et al. (2016) Whole Grain Intake and Mortality From All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Circulation 133, 2370-80. NIH Public Access. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Zong G, Gao A, Hu FB, et al. Circulation . Vol. 133. NIH Public Access; 2016. Whole Grain Intake and Mortality From All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies; pp. 2370–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.. Mozaffarian RS, Lee RM, Kennedy MA, et al. (2013) Identifying whole grain foods: a comparison of different approaches for selecting more healthful whole grain products. Public Health Nutr. 16, 2255-64. NIH Public Access. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Mozaffarian RS, Lee RM, Kennedy MA, et al. Public Health Nutr. Vol. 16. NIH Public Access; 2013. Identifying whole grain foods: a comparison of different approaches for selecting more healthful whole grain products; pp. 2255–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.. Temple NJ (2018) Fat, Sugar, Whole Grains and Heart Disease: 50 Years of Confusion. Nutrients 10. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Temple NJ. Nutrients . Vol. 10. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2018. Fat, Sugar, Whole Grains and Heart Disease: 50 Years of Confusion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.. Chen JP, Chen GC, Wang XP, et al. (2017) Dietary Fiber and Metabolic Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Related Mechanisms. Nutrients 10. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Chen JP, Chen GC, Wang XP, et al. Nutrients . Vol. 10. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2017. Dietary Fiber and Metabolic Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Related Mechanisms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.. German Nutrition Society Whole Grain. www.dge.de/ernaehrungspraxis/vollwertige-ernaehrung/10-regeln-der-dge/; German Nutrition Society Whole Grain. www.dge.de/ernaehrungspraxis/vollwertige-ernaehrung/10-regeln-der-dge/ [Google Scholar]

- 39.. Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca per gli Alimenti e la Nutrizione & (INRAN) (2003) Linee Guida Per Una Sana Alimentazione Italiana. 30-34.; Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca per gli Alimenti e la Nutrizione & (INRAN) Linee Guida Per Una Sana Alimentazione Italiana. 2003. pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.. Grain (cereal) foods, mostly wholegrain and / or high cereal fibre varieties | Eat For Health. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/food-essentials/five-food-groups/grain-cereal-foods-mostly-wholegrain-and-or-high-cereal-fibre (accessed February 2020).; Grain (cereal) foods, mostly wholegrain and / or high cereal fibre varieties. [accessed February 2020];Eat For Health. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/food-essentials/five-food-groups/grain-cereal-foods-mostly-wholegrain-and-or-high-cereal-fibre . [Google Scholar]

- 41.. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2018) Cancer Prevention Recommendations. Diet, Nutr. Phys. Act. Cancer a Glob. Perspect. Contin. Updat. Proj. Expert Rep.; World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Cancer Prevention Recommendations. Diet, Nutr. Phys. Act. Cancer a Glob. Perspect. Contin. Updat. Proj. Expert Rep 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 42.. Yang Y, Guo M, Sun S, et al. (2019) Natural variation of OsGluA2 is involved in grain protein content regulation in rice. Nat. Commun. 10, 1-12. Nature Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Yang Y, Guo M, Sun S, et al. Nat. Commun. Vol. 10. Nature Publishing Group; 2019. Natural variation of OsGluA2 is involved in grain protein content regulation in rice; pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.. Kaur B, Ranawana V, Henry J. (2016) The Glycemic Index of Rice and Rice Products: A Review, and Table of GI Values. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 56, 215-236. [DOI] [PubMed]; Kaur B, Ranawana V, Henry J. The Glycemic Index of Rice and Rice Products: A Review, and Table of GI Values. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;56:215–236. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.717976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.. Vitale M, Masulli M, Rivellese AA, et al. (2019) Pasta Consumption and Connected Dietary Habits: Associations with Glucose Control, Adiposity Measures, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in People with Type 2 Diabetes-TOSCA.IT Study. Nutrients 12, 101. MDPI AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Vitale M, Masulli M, Rivellese AA, et al. IT Study. Nutrients. 101. Vol. 12. MDPI AG; 2019. Pasta Consumption and Connected Dietary Habits: Associations with Glucose Control, Adiposity Measures, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in People with Type 2 Diabetes-TOSCA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.. Chiavaroli L, Kendall CWC, Braunstein CR, et al. (2018) Effect of pasta in the context of low-glycaemic index dietary patterns on body weight and markers of adiposity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials in adults. BMJ Open 8. BMJ Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Chiavaroli L, Kendall CWC, Braunstein CR, et al. BMJ Open . Vol. 8. BMJ Publishing Group; 2018. Effect of pasta in the context of low-glycaemic index dietary patterns on body weight and markers of adiposity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials in adults. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.. Sogari G, Li J, Lefebvre M, et al. (2019) The influence of health messages in nudging consumption of whole grain pasta. Nutrients 11. MDPI AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Sogari G, Li J, Lefebvre M, et al. Nutrients . Vol. 11. MDPI AG; 2019. The influence of health messages in nudging consumption of whole grain pasta. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.. Kafatos A, Linardakis M, Bertsias G, et al. (2005) Consumption of ready-to-eat cereals in relation to health and diet indicators among school adolescents in Crete, Greece. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 49, 165-72. Karger Publishers. [DOI] [PubMed]; Kafatos A, Linardakis M, Bertsias G, et al. Ann. Nutr. Metab. Vol. 49. Karger Publishers; 2005. Consumption of ready-to-eat cereals in relation to health and diet indicators among school adolescents in Crete, Greece; pp. 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.. Rito AI, Dinis A, Rascôa C, et al. (2018) Improving breakfast patterns of portuguese children-an evaluation of ready-to-eat cereals according to the European nutrient profile model. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., 1. Nature Publishing Group. [DOI] [PubMed]; Rito AI, Dinis A, Rascôa C, et al. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. Vol. 1. Nature Publishing Group; 2018. Improving breakfast patterns of portuguese children-an evaluation of ready-to-eat cereals according to the European nutrient profile model. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.. Diabetes UK (2018) Breakfast cereals. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/enjoy-food/eating-with-diabetes/diabetes-food-myths/breakfast-cereals.; Diabetes UK . Breakfast cereals. 2018. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/enjoy-food/eating-with-diabetes/diabetes-food-myths/breakfast-cereals [Google Scholar]

- 50.. Marventano S, Vetrani C, Vitale M, et al. (2017) Whole Grain Intake and Glycaemic Control in Healthy Subjects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 9. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Marventano S, Vetrani C, Vitale M, et al. Nutrients . Vol. 9. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2017. Whole Grain Intake and Glycaemic Control in Healthy Subjects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.. Slavin J (2003) Why whole grains are protective: biological mechanisms. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 62, 129-134. Cambridge University Press. [DOI] [PubMed]; Slavin J. Proc. Nutr. Soc. Vol. 62. Cambridge University Press; 2003. Why whole grains are protective: biological mechanisms; pp. 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.. EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies (2010) Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA J. 8, 1462.; EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA J. 2010;8:1462–1462. [Google Scholar]

- 53.. Gil A, Ortega RM, Maldonado JJ (2011) Wholegrain cereals and bread: a duet of the Mediterranean diet for the prevention of chronic diseases. Public Health Nutr. 14, 2316-2322. England: Cambridge University Press. [DOI] [PubMed]; Gil A, Ortega RM, Maldonado JJ. Public Health Nutr. Vol. 14. England: Cambridge University Press; 2011. Wholegrain cereals and bread: a duet of the Mediterranean diet for the prevention of chronic diseases; pp. 2316–2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.. Quick V, Wall M, Larson N, et al. (2013) Personal, behavioral and socio-environmental predictors of overweight incidence in young adults: 10-yr longitudinal findings. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 10, 37. BioMed Central. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Quick V, Wall M, Larson N, et al. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 37. Vol. 10. BioMed Central; 2013. Personal, behavioral and socio-environmental predictors of overweight incidence in young adults: 10-yr longitudinal findings. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.. Josep Maria Argimon Pallas JJV (2019) Métodos de Investigación Clínica Y Epidemiológica. Elsevier H.; Josep-Maria-Argimon-Pallas JJV. Métodos de Investigación Clínica Y Epidemiológica. Elsevier H; 2019. [Google Scholar]