Abstract

Introduction

The competency of a nurse in integrating knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values in various healthcare areas depends on their ability to apply these elements. It is a basic indicator of performance in nursing, and its assessment is a necessity among nursing students.

Objective

The present study was conducted to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the nursing competence tool for Iranian nursing students in 2023.

Methods

This is a methodological study in which the Nursing Student Competence Scale (NSCS) was translated into Persian using the forward–backward translation method. A total of 321 nursing students were selected for construct validity by the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (the first 190 nursing students) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) by convenience sampling method. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency, and the test–retest method was used to check the instrument's reliability.

Results

The results of EFA and CFA confirmed the instrument with six factors and 28 items. The results showed that the fit indices of the model in CFA included (CFI = .91, NNFI = .90, goodness of fit index = .83, root mean square error of approximation = .075, standardized root mean square residual = .047). Pearson's correlation coefficient between items and subscales showed a direct and significant relationship with the main scale. Also, Cronbach's alpha coefficient (0.9) and test–retest (0.88) confirmed the reliability of the Persian version of (NSCS).

Conclusion

Generally, the Persian version of the NSCS with 28 items and six factors is a valid and reliable scale. This instrument has good internal consistency, validity, and reliability, which can be used to evaluate nursing students’ competence in bachelor training.

Keywords: nursing students, clinical competence, psychometrics, validity, reliability

Introduction

Nurses are the biggest group of professional staff in healthcare (Ezzati et al., 2023a, 2023b). They play diverse and important roles and responsibilities (Oldland et al., 2020). Nurses play a crucial role in the global healthcare system due to the multitude of tasks they perform (Figueroa et al., 2019; Rosen et al., 2018). Nursing requires a high level of responsibility, precision, and attentiveness due to its complexity (Ezzati et al., 2023a). Competent nurses greatly impact an organization's effectiveness and success (Hossny et al., 2023).

Changes in health monitoring (Ezzati et al., 2023b), the need for safe and cost-efficient services (Griffiths et al., 2023), raising public health awareness (Rosen et al., 2018), and the push for high-quality accessible services are prompting healthcare providers (Ezzati et al., 2023a; Hadian Jazi et al., 2019) to focus more on skilled professionals (Cao et al., 2023; Mlambo et al., 2021). This shift emphasizes the clinical skills of healthcare workers like never before (Tucci et al., 2022).

Given the significance of quality patient care, the idea of nurses’ clinical competency is crucial in both education and practice (Mlambo et al., 2021). Clinical competence involves using technical and communication skills, knowledge, judgment, emotions, and values effectively in healthcare (Nabizadeh-Gharghozar et al., 2021; Tucci et al., 2022), serving as a key factor in evaluating nursing performance (Rapin et al., 2022). It is vital for ensuring safe and professional care (Nabizadeh-Gharghozar et al., 2021).

A lack of clinical competence can jeopardize patient safety (Ahn et al., 2018; Torkaman et al., 2022). Competent nurses feel more confident and make better clinical decisions in complex situations (Alavi et al., 2022; Oh et al., 2022). Evaluating nurses’ clinical competence is essential to manage care effectively, understand educational needs, and ensure quality care (Notarnicola et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2021). Nursing managers in clinical settings play a pivotal role in maintaining quality standards and managing human resources (Ghafari et al., 2022). It is the focal point for quality assurance systems, workforce planning, and human resource management, making it the most pivotal responsibility for nursing managers in clinical environments (Helminen et al., 2017; Hossny et al., 2023; Nabizadeh-Gharghozar et al., 2021; Oldland et al., 2020).

Assessing the competence of nursing students is a global concern that has challenged educators for years (Ličen & Prosen, 2023). Evaluating nurses’ clinical competence must adapt to the evolving standards of care set by the World Health Organization (Huang et al., 2022). Mentors struggle to evaluate students’ abilities without clear criteria, support from educators, and proper assessment training (Immonen et al., 2019). Professionalization in nursing begins during students’ training and extends till their work in hospitals and beyond (Cao et al., 2023). An essential aspect of this journey is achieving a high level of clinical competence, which is especially crucial for evaluating nursing students (Alkhelaiwi et al., 2024; Immonen et al., 2019). These evaluations play a significant role in educational development and shaping positive enhancements to students’ curricula (Ezzati et al., 2023b; Helminen et al., 2017; Nabizadeh-Gharghozar et al., 2021).

Review of Literature

In our review of the literature, we came across several tools that have been developed for evaluating nursing competence in students and newly graduated nurses (Abuadas, 2023; Flinkman et al., 2017; Franklin & Melville, 2015). The Nursing Student Competence Scale (NSCS) is commonly used for evaluating the competence of nurses and their managers (Flinkman et al., 2017). Hisar et al.’s (2010) study identified a reliable tool for measuring professional attitudes in nursing students in Turkey. Hsu and Hsieh (2013) designed a nursing student competency tool with 52 items and eight factors: biomedical-basic sciences, general clinical nursing skills, communication and collaboration, critical thinking, caring, ethics, accountability, and lifelong learning.

Synthesizing evidence suggests using nursing student competence tools to assess nursing competence (Franklin & Melville, 2015; Hisar et al., 2010; Hsu & Hsieh, 2013; Huang et al., 2022). In 2022, a tool was adapted and tested on a student community in Taiwan, evaluating competency in medical knowledge, basic nursing skills, communication, cooperation, lifelong learning, global vision, and critical thinking. Using this scale can help in developing strategies to address care dilemmas in teaching and learning environments, offering valuable insights to nursing professionals, especially educators (Huang et al., 2022). Evaluation of the tool's items revealed good coordination with the clinical activities of nursing students, prompting the need to translate and validate a comprehensive clinical assessment tool for assessing nursing student competence in Iran. Thus, this study aimed to translate and validate an all-encompassing clinical assessment tool with reasonable validity and reliability, considering the absence of a suitable instrument for assessing nursing student competence in Iran.

Methods

Study Design

This is a methodological study that focuses on the Persian version of the NSCS in Iran. This study was carried out from May to October 2023.

Setting

The study population comprised nursing students from Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. Considering the importance of sample distinction in each stage of construct validation (Kyriazos, 2018; White, 2022), 190 individuals were selected for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) phase (de Winter et al., 2009). Ultimately, 321 nursing students were chosen for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) based on study inclusion criteria and availability (White, 2022).

Participants

The participants in this study were nursing students selected based on study inclusion criteria and availability. For quantitative and qualitative content validity, the questionnaire was distributed among 15 academic faculty members, researchers, and relevant specialists. For face validity, 10 nursing students participated, and for reliability testing, a retest method was employed with 20 separate nursing students from the selected samples. For EFA and CFA, 321 nursing students were chosen as available research samples, completing the questionnaire through self-reporting. All the questionnaires were administered in person by a colleague of the researcher who had no involvement in the educational programs of the nursing students. During this time, he explained the study's objectives in response to the students’ questions. The questionnaires were completed on paper by the students after the explanation by the researcher's colleague. The consent form to participate in the study was also the first page of each questionnaire, which was not filled by the students. The approximate time to complete the questionnaires by each student was 18 min on average.

Study inclusion criteria included interest and willingness to participate, students majoring in nursing who had completed at least one academic term, and exclusion if the specific questionnaire was completed less than 95%, resulting in 344 initially selected students. Eventually, 23 questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete information.

Nursing Student Competence Scale

NSCS developed by Huang et al. (2022) in Taiwan consists of 30 items, covering six dimensions: (1) medical-related knowledge (five items), (2) basic nursing skills (five items), (3) communication and cooperation (five items), (4) life-long learning (five items), (5) global vision (five items), and (6) critical thinking (five items). The respondent is asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 for “not agree” to 5 for “highly agree.” Higher scale scores associated with greater nursing competence, and higher scale scores are associated with greater nursing competence. In the primary study, this scale showed good fit characteristics. Cronbach's alpha for its subscales ranged from 0.91 to 0.98 (Huang et al., 2022).

Cultural Validation and Tool Psychometric Process

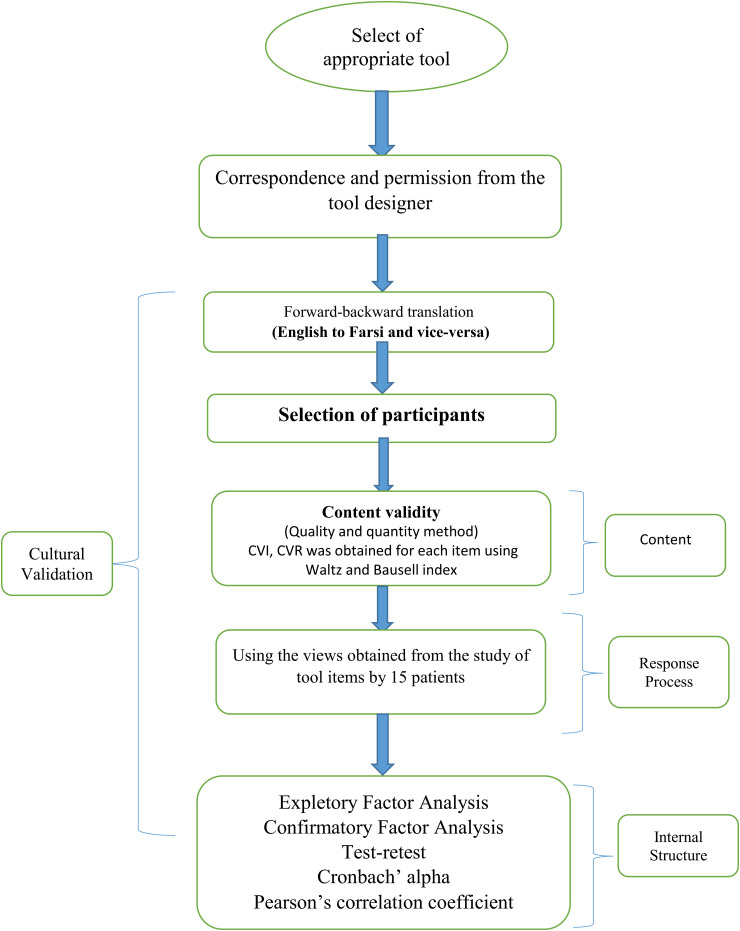

Initially, communication was established with the tool developer to obtain permission to conduct this research. After correspondence and receiving authorization, all procedures were carried out in three stages (Cook & Beckman, 2006; Cook & Hatala, 2016), including content examination to ensure the items in the tool have a comprehensive structure, response process assessment to evaluate the relationship between the tool and respondents’ opinions and thoughts, and internal structure evaluation to demonstrate the reliability and an acceptable factor structure of the tool (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Response process.

Content and Response Process Evaluation

Cultural Validation

To assess the content and response process, the tool's cultural validation stages were conducted using Wild et al.'s (2005) 10-step process.

Step 1: Preparation—the appropriate tool was selected, and the translation and psychometric permission were obtained from the tool designer.

Step 2: Forward translation—the tool was translated into Persian using the forward method. Two independent translators simultaneously translated the tool from English to Persian.

Step 3: Reconciliation—after review and synthesis by the research team, the translated versions were consolidated into a single version (no discrepancy was found; some words were replaced).

Step 4: Back translation—this Persian version was then independently translated back into English by two translators who were not involved in the initial translation stage (no discrepancy was found).

Step 5: Back translation review—the research team scrutinized the two English versions, leading to a final unified version sent to the tool's developer for feedback and incorporation of their comments.

Step 6: Harmonization—the translated version was compared to the original instrument to resolve contradictions and vocabulary problems. Finally, the harmony between the translated version and the original instrument was confirmed (no inconsistency was found between the concepts of the two versions).

Step 7: Cognitive debriefing—the final Persian version was provided to 18 nursing students, and they were asked to articulate any ambiguities or potential issues (face validity).

Step 8: Review the cognitive debriefing results and finalization—the research students reviewed the nursing students’ perspectives and adjusted the final version (no discrepancy was found; some words were replaced).

Step 9: Proofreading—a Persian language and literature expert edited and approved the final version.

Step 10: Final report—after documenting all stages, the final version was utilized for psychometric evaluations.

Content Validity

Content evaluation employed both qualitative and quantitative methods. The qualitative approach (cognitive interviewing) assessed the questionnaire's arrangement and relevance to the study objectives (Rodrigues et al., 2017). For the quantitative method, 14 experts and faculty members participated, resulting in a content validity ratio of 0.80 and a range of 0.71 to 1.0. Additionally, the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) (Rodrigues et al., 2017) for the tool was 0.85, within the range of 0.86 to 1.0 (Supplemental Table 1).

Data Analysis

Face validity was assessed through the perspectives of 18 individuals. In contrast, quantitative and qualitative content validity were evaluated based on the opinions of 14 researchers and experts, including five nursing professionals and four nursing faculty members. Subsequently, the tools’ quantitative content validity (Polit et al., 2007) was determined for each item using the Waltz and Bausell index method. Skewness values for all items ranged from −1.27 to 1.48, and Kurtosis values ranged from −0.91 to 2.06, indicating nearly symmetric distributions (Supplemental Table 1). Reliability was examined through the test–retest method (Gravesande et al., 2019), and the internal consistency of the tool was tested using Cronbach's alpha. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25 and LISREL 8.

Results

Descriptive Results

In the EFA phase of the present study, 190 nursing students participated. They were selected through availability and based on the study's inclusion criteria. The participants had an average age of 22.48 ± 1.3, ranging from 18 to 38 years old. Among them, 47.37% were male, 76.32% urban residents, and 23.68% dormitory residents. All study participants were undergraduate nursing students with a reported history of clinical activity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in Study.

| Variables | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| EFA | CFA | ||

| Gender | Female | 100 (52.63) | 168 (52.34) |

| Male | 90 (47.37) | 153 (47.66) | |

| School year | First year | 32 (16.8) | 41 (12.8) |

| Second year | 36 (18.9) | 85 (26.5) | |

| Third year | 57 (30) | 98 (30.5) | |

| Forth year | 65 (34.2) | 97 (30.2) | |

| Residence | Urban | 145 (76.32) | 253 (78.82) |

| Dormitory | 45 (23.68) | 68 (21.18) | |

Note. CFA: confirmatory factor analysis; EFA: exploratory factor analysis.

In the CFA stage, the sample size from the EFA phase reached 321 nursing students, all selected through availability. The participants had an average age of 22.09 ± 2.71, ranging from 18 to 42 years old. Among them, 47.66% were male, 78.82% urban residents, and 21.18% dormitory residents, and all participants reported a history of clinical activity (Table 1).

Construct Validation Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

EFA was conducted on 190 nursing students. For the EFA, correlation coefficients between the questionnaire items were examined to ensure their interrelatedness. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test results were 0.74, and Bartlett's test of sphericity was 3896. Given the results and the significance level (p < .001), it was justified to proceed with EFA on this questionnaire.

After confirming the above assumptions, EFA was performed on the participants’ responses and the 30 questionnaire items. The principal component analysis (PCA) and varimax orthogonal rotation methods were used to extract factors. Supplemental Table 2 presents the factor loadings obtained through PCA and the stability test results.

Those with eigenvalues greater than 1 were selected to determine the number of factors. The initial results indicated that six factors or components could be chosen for analysis. Supplemental Table 3 shows the extracted factors along with eigenvalues, the percentage of each factor's contribution to explaining the variance of 30 items, and the cumulative explained variance. These six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 explained 74.85% of the variance of the 30 items. Specifically, the first factor contributed 25.75%, the second 14.30%, the third 10.61%, the fourth 10.24%, the fifth 8.27%, and the sixth 5.67% to the cumulative variance. The scree plot, an output of the factor analysis in SPSS, also supports the suitability of these six factors or components for the final analysis (Supplemental Figure 1).

Supplemental Table 4 provides the rotated factor matrix, showing the questions with factor loadings exceeding 0.30 and the highest loadings assigned to the respective components.

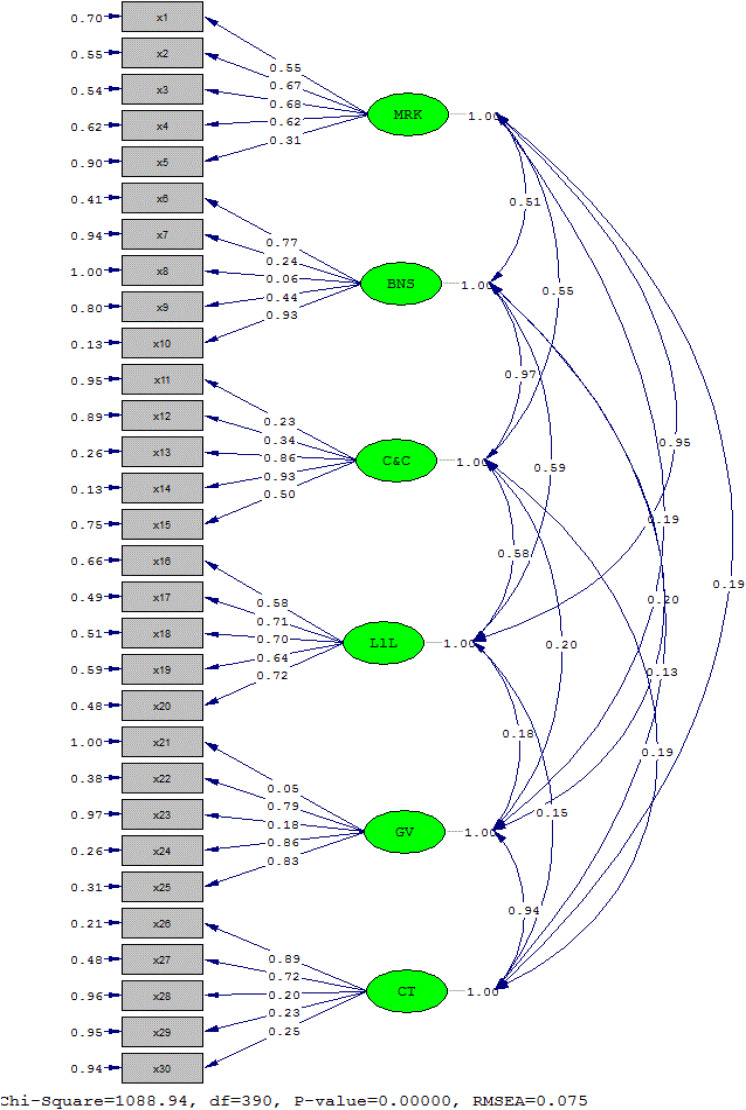

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

CFA was performed on 321 samples. To assess the normality of the data distribution, the Skewness and Kurtosis indicators were employed, indicating that the data followed a normal distribution. The model fit was evaluated by examining the factor loadings of each item and using fit indices.

The CFA results showed that items 8 (t = 1.08) from factor 2 and item 21 (t = 0.86) from factor 5 were removed due to inappropriate factor loadings. The Persian version of the NSCS was obtained with 28 items and six factors, demonstrating good fit based on the fit indices as NNFI = 0.9, CFI = 0.91, AGFI = 0.83, standardized root mean square residual = 0.047, root mean square error of approximation = 0.075 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fit Indices of Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model of Nursing Student Competence Scale.

| Fit indicators | Criterion | Level | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| χCSSUPSTART2CSSUPEND/DF | ≤ 3 | 2.79 | Optimal fit |

| DF | 390 | ||

| X2 | 1088.94 | ||

| p VALUE | .0001 | ||

| NNFI (or TLI) |

>0.9 | 0.9 | Optimal fit |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.91 | Optimal fit |

| AGFI | >0.8 | 0.83 | Optimal fit |

| SRMR | <0.05 | 0.047 | Optimal fit |

| RMSEA | 0.05–0.08 | 0.075 | Optimal fit |

Note. AGFI: adjusted goodness of fit index; CFI: comparative fit index; NNFI: non-normed fit index; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; SRMR: standardized root mean square residual; TLI: Tucker–Lewis index.

Figure 2 illustrates the significant and standardized factor-loading test results.

Figure 2.

Six-factor model of Nursing Student Competence Scale (standard).

Reliability

The reliability of the NSCS in Iran was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha and test-rater reliability. The findings indicated that the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the 28 items was 0.9, and for each of the six factors in the model, it ranged from 0.86 to 0.92. Furthermore, the tool's reliability was confirmed through a test–retest (0.88) (Table 3).

Table 3.

T-Value Pearson Correlation Coefficient and Factor Loadings of the Nursing Student Competence Scale.

| Factor | Number | value a t | b (λ) | R c | Cronbach alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical-related knowledge | 1 | 9.85 | 0.55*** | 0.69** | 0.885 | 0.919 |

| 2 | 12.61 | 0.67*** | 0.71** | 0.885 | ||

| 3 | 12.73 | 0.68*** | 0.70** | 0.886 | ||

| 4 | 11.35 | 0.62*** | 0.74** | 0.882 | ||

| 5 | 5.36 | 0.31*** | 0.52** | 0.885 | ||

| Basic nursing skills | 6 | 16.03 | 0.77*** | 0.72** | 0.885 | 0.913 |

| 7 | 4.16 | 0.24*** | 0.62** | 0.889 | ||

| 8 | 1.08 | 0.06*** | 0.38** | 0.887 | ||

| 9 | 8.1 | 0.44*** | 0.72** | 0.886 | ||

| 10 | 21.37 | 0.93*** | 0.77** | 0.890 | ||

| Communication and cooperation | 11 | 4.04 | 0.23*** | 0.42** | 0.884 | 0.882 |

| 12 | 6.02 | 0.34*** | 0.50** | 0.884 | ||

| 13 | 18.7 | 0.86*** | 0.84** | 0.889 | ||

| 14 | 21.7 | 0.93*** | 0.87** | 0.884 | ||

| 15 | 9.3 | 0.50*** | 0.66** | 0.882 | ||

| Life-long learning | 16 | 10.78 | 0.58*** | 0.72** | 0.885 | 0.856 |

| 17 | 13.94 | 0.71*** | 0.75** | 0.883 | ||

| 18 | 13.65 | 0.70*** | 0.79** | 0.883 | ||

| 19 | 12.15 | 0.64*** | 0.69** | 0.884 | ||

| 20 | 14.07 | 0.72*** | 0.79** | 0.883 | ||

| Global vision | 21 | 0.86 | 0.05*** | 0.44** | 0.885 | 0.921 |

| 22 | 16.39 | 0.79*** | 0.72** | 0.883 | ||

| 23 | 3.16 | 0.18*** | 0.53** | 0.883 | ||

| 24 | 18.68 | 0.86*** | 0.76** | 0.883 | ||

| 25 | 17.69 | 0.83*** | 0.79** | 0.888 | ||

| Critical thinking | 26 | 18.81 | 0.89*** | 0.63** | 0.886 | 0.924 |

| 27 | 14.22 | 0.72*** | 0.63** | 0.889 | ||

| 28 | 3.36 | 0.20*** | 0.76** | 0.888 | ||

| 29 | 3.9 | 0.23*** | 0.76** | 0.888 | ||

| 30 | 4.36 | 0.25*** | 0.75** | 0.887 | ||

| The Nursing Student Competence Scale | 0.9 | |||||

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

The calculated values for all factor loadings of the first and second orders are greater than 1.96 and are therefore significant at the 95% confidence level.

The specific value, which is denoted by the Lamda coefficient and the statistical symbol λ, is calculated from the sum of the factors of the factor loads related to all the variables of that factor.

Pearson correlation coefficient.

The Correlation Among Factors

The Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to examine the correlation among the factors of the Persian version of the Nursing Students’ Critical Thinking Disposition instrument showed a significant correlation at the 99% confidence level (p < .01) for all factors and the overall scale. Furthermore, a significant correlation is observed at the 99% confidence level (p < .01) among the mentioned scale factors. The only exception is the lack of significant correlation between critical thinking and basic nursing knowledge, as well as critical thinking, coordination, and interaction factors (p > .05). Therefore, the mentioned scale and its factors have a suitable correlation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation Results of the Persian Version of Nursing Students’ Competency Tool and Its Factors.

| Factor | Number of items | MRK | BNS | C&C | L.L | GV | CT | NSCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Related Knowledge (MRK) | 5 | 1 | 0.603** | 0.62** | 0.703** | 0.225** | 0.228** | 0.821** |

| Basic Nursing Skills (BNS) | 4 | 0.603** | 1 | 0.757** | 0.584** | 0.382** | 0.04 | 0.78** |

| Communication and Cooperation (C&C) | 5 | 0.616** | 0.757** | 1 | 0.638** | 0.316** | 0.061 | 0.768** |

| Life-long learning (L.L) | 5 | 0.703** | 0.584** | 0.638** | 1 | 0.219** | 0.15** | 0.77** |

| Global Vision (GV) | 4 | 0.225** | 0.382** | 0.316** | 0.219** | 1 | 0.452** | 0.569** |

| Critical Thinking (CT) | 5 | 0.228** | 0.04 | 0.061 | 0.15** | 0.452* | 1 | 0.437** |

| The Nursing Student Competence Scale (NSCS) | 28 | 0.821** | 0.78** | 0.768** | 0.77** | 0.569** | 0.437** | 1 |

p <.001.

Discussion

In this study, the Persian version of the competency questionnaire for nursing students underwent cultural and psychometric validation. The results demonstrated the appropriate validity and reliability of the Persian version of the questionnaire within the Iranian nursing student community. Six factors were extracted using the varimax rotation method, and they were able to account for 74.84% of the variance of the 28 items, with eigenvalues higher than 1.

This questionnaire was previously evaluated in Taiwan, with the results revealing six factors and 30 items that assess students’ competence in those areas (Huang et al., 2022). Notarnicola et al. (2018) also conducted a study on a clinical competence questionnaire with seven factors and 38 subjects. Additionally, Wu et al. (2016) confirmed the clinical classification of nurses with four factors.

Overall, nursing competence encompasses various factors such as knowledge, professional judgment, skills, values, and attitudes. Nurses in clinical settings must apply their knowledge, skills, and individual characteristics in diverse situations and adapt accordingly. Previous studies have defined nursing competence as the ability to identify client needs using logical thinking (Abuadas, 2023; Huang et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2021). The factors obtained from psychometric tools align with these definitions, confirming the model's validity and appropriateness.

The study used both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The analysis was performed to investigate how cultural variables might impact the scale in a new culture. The research confirmed that the Persian version of NSCS has a valid structure and quality, evaluating nursing students in Iran across six subscales. The original tool presented six subscales, and the authors emphasized its validity and reliability in measuring nursing student competence (Huang et al., 2022).

The Persian version of NSCS contains 28 items, organized into six factors: (1) medical knowledge, (2) basic nursing skills, (3) communication and cooperation, (4) lifestyle, (5) global insight, and (6) critical thinking. The original questionnaire had 30 items and six factors, but items 8 and 21 were removed in this study due to their factor loading being less than 0.3 (Huang et al., 2022). Items 8 and 21 reveal differences in nursing students’ performances during the second medical examination and their understanding of treatment, health, and disease matters, respectively. This disparity might be due to the gap between theoretical and practical training. A literature review suggests that care following the nursing process is seldom implemented in Iranian hospitals, and there's a deficiency in teaching fundamental sciences (Ezzati et al., 2023b; Lotfi et al., 2020). Omitting these two items highlights the obstacles encountered in clinical education. The Persian version of the tool was confirmed with 28 items and six factors. The results suggest that the societal type and culture under study can have an impact. Upon closer scrutiny of the items, it appears that their meaning is more in line with the tasks of medical students rather than focusing on nursing concepts. There may be differences in the roles and descriptions of responsibilities of nurses in Iran and other countries, as these two items were removed in this study. This finding could be the main explanation for the disparities in roles and duties assignments between the two countries.

To assess the tool's internal consistency, we calculated Cronbach's reliability coefficient, which resulted in a value of 0.9. In Huang et al.'s (2022) study, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient ranged from 0.91 to 0.98. Similarly, in the studies by Huang et al. (2022) and Abuadas (2023), Cronbach's alpha coefficient was reported as 0.89. This value is similar to the one obtained in our research, suggesting that our questionnaires have effectively aligned with the job descriptions and the way nurses are trained.

Strengths and Limitations

The results of this study show the importance of not only translation but also psychometric validation of tools. This study had some limitations. For instance, participants might have felt pressured to be truthful or may not have had enough time to complete the questionnaire. To obtain more precise results, it is recommended to conduct similar research involving nurses employed in various sectors. It's also worth noting that the survey was filled out by a predominantly female undergraduate student population. If a different population, such as working nurses or male nurses, were surveyed, the results could vary.

Implications for Practice

The study results are valuable for researchers, nursing professors, and nursing career planners. Researchers and students can benefit from the study's implementation process for conducting similar studies. Additionally, nursing professors and managers can utilize the valid and reliable version of the study tool.

Conclusion

The findings of the study suggest that the Persian adaptation of the NSCS questionnaire, comprising 28 items and six subscales, demonstrates acceptable fit indices and is suitable for utilization in numerous related studies within the Iranian nursing student population. This instrument may be utilized in various studies to assess the competence of nursing students, providing valuable data for strategic planning purposes aimed at improving nursing students’ skills and competency.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608241299275 for Transcultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Nursing Student Competence Scale (NSCS) by Amir Jalali, Fatemeh Chavoshani, Raheleh Rasad, Niloufar Darvishi, Fatemeh Merati Fashi, Mahbod Khodamorovati and Khalil Moradi in SAGE Open Nursing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-son-10.1177_23779608241299275 for Transcultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Nursing Student Competence Scale (NSCS) by Amir Jalali, Fatemeh Chavoshani, Raheleh Rasad, Niloufar Darvishi, Fatemeh Merati Fashi, Mahbod Khodamorovati and Khalil Moradi in SAGE Open Nursing

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the faculty members of the Student Research Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CFA

confirmatory factor analysis

- CVI

content validity index

- CVR

content validity ratio

- EFA

explorative factor analysis

- ESQ-NS

ethical sensitivity questionnaire for nursing students

- GFI

goodness of fit index

- KMO

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

- KUMS

Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences

- NFI

normed fit index

- PC

principal components

- RMSEA

root mean square error of approximation

- SRMR

standardized root mean square residual

- TLI

Tucker–Lewis index.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: KM and AJ contributed to designing the study; ND, RR, FM, and FC collected the data, and data analyses were done by AJ and MK. The final report and article were written by AJ, KM, ND, RR, MK, FC, and FM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, and participated and approved the study design.

Data Availability: The datasets used for the present analysis may be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Written permission was secured from the developer of scale, and the ethics committee of the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences approved the study under the ethics code: IR.KUMS.REC.1401.262. The students’ participation was voluntary and anonymous, and informed consent was obtained from study participants. In addition, the principles of the Helsinki Declaration were observed. All methods were performed per the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was partly funded by the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (grant number 4020061).

ORCID iDs: Amir Jalali https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0307-879X

Khalil Moradi https://orcid.org/0009-0008-8594-1374

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Reference

- Abuadas M. H. (2023). The Arabic nurse professional competence-short version scale (NPC-SV-A): Transcultural translation and adaptation with a cohort of Saudi nursing students. Healthcare, 11(5), 691. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/11/5/691. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S., Lee N.-J., Jang H. (2018). Patient safety teaching competency of nursing faculty. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 48(6), 720–730. 10.4040/jkan.2018.48.6.720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi N. M., Nabizadeh-Gharghozar Z., Ajorpaz N. M. (2022). The barriers and facilitators of developing clinical competence among master’s graduates of gerontological nursing: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 500. 10.1186/s12909-022-03553-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhelaiwi W. A., Traynor M., Rogers K., Wilson I. (2024). Assessing the competence of nursing students in clinical practice: The clinical Preceptors’ perspective. Healthcare (Basel), 12(10), 1031. 10.3390/healthcare12101031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H., Song Y., Wu Y., Du Y., He X., Chen Y., …Yang H. (2023). What is nursing professionalism? A concept analysis. Bmc Nursing, 22(1), 34. 10.1186/s12912-022-01161-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. A., Beckman T. J. (2006). Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: Theory and application. The American Journal of Medicine, 119(2), 166. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. A., Hatala R. (2016). Validation of educational assessments: A primer for simulation and beyond. Advances in Simulation, 1(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s41077-016-0033-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Winter J. C., Dodou D., Wieringa P. A. (2009). Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(2), 147–181. 10.1080/00273170902794206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati E., Molavynejad S., Jalali A., Cheraghi M.-A., Jahani S., Rokhafroz D. (2023a). The challenges of the Iranian nursing system in addressing community care needs. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 12, 362. 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1398_22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati E., Molavynejad S., Jalali A., Cheraghi M.-A., Jahani S., Rokhafroz D. (2023b). Exploring the social accountability challenges of nursing education system in Iran. BMC Nursing, 22(1), 7. 10.1186/s12912-022-01157-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa C. A., Harrison R., Chauhan A., Meyer L. (2019). Priorities and challenges for health leadership and workforce management globally: A rapid review. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 239. 10.1186/s12913-019-4080-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinkman M., Leino-Kilpi H., Numminen O., Jeon Y., Kuokkanen L., Meretoja R. (2017). Nurse competence scale: A systematic and psychometric review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(5), 1035–1050. 10.1111/jan.13183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin N., Melville P. (2015). Competency assessment tools: An exploration of the pedagogical issues facing competency assessment for nurses in the clinical environment. Collegian, 22(1), 25–31. 10.1016/j.colegn.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafari S., Atashi V., Taleghani F., Irajpour A., Sabohi F., Yazdannik A. (2022). Comparison of the effect of two methods of internship and apprenticeship in the field on clinical competence of nursing students. Research in Medical Education, 14(1), 64–72. 10.52547/rme.14.1.64 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gravesande J., Richardson J., Griffith L., Scott F. (2019). Test-retest reliability, internal consistency, construct validity and factor structure of a falls risk perception questionnaire in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. Archives of Physiotherapy, 9(14), 1–11. 10.1186/s40945-019-0065-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths P., Saville C., Ball J., Dall'Ora C., Meredith P., Turner L., Jones J. (2023). Costs and cost-effectiveness of improved nurse staffing levels and skill mix in acute hospitals: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 147, 104601. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadian Jazi Z., Peyrovi H., Zareian A. (2019). Nurse's social responsibility: A hybrid concept analysis in Iran. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 33(1), 266–272. 10.34171/mjiri.33.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helminen K., Johnson M., Isoaho H., Turunen H., Tossavainen K. (2017). Final assessment of nursing students in clinical practice: Perspectives of nursing teachers, students and mentors. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23-24), 4795–4803. 10.1111/jocn.13835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisar F., Karadag A., Kan A. (2010). Development of an instrument to measure professional attitudes in nursing students in Turkey. Nurse Education Today, 30(8), 726–730. 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossny E. K., Alotaibi H. S., Mahmoud A. M., Elcokany N. M., Seweid M. M., Aldhafeeri N. A., …Abd Elhamed S. M. (2023). Influence of nurses’ perception of organizational climate and toxic leadership behaviors on intent to stay: A descriptive comparative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 5, 100147. 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2023.100147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L. L., Hsieh S. I. (2013). Development and psychometric evaluation of the competency inventory for nursing students: A learning outcome perspective. Nurse Education Today, 33(5), 492–497. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.-M., Fang S.-C., Hung C.-T., Chen Y.-H. (2022). Psychometric evaluation of a nursing competence assessment tool among nursing students: A development and validation study. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 372. 10.1186/s12909-022-03439-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immonen K., Oikarainen A., Tomietto M., Kääriäinen M., Tuomikoski A.-M., Kaučič B. M., …Perez-Canaveras R. M. (2019). Assessment of nursing students’ competence in clinical practice: A systematic review of reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 100, 103414. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazos T. A. (2018). Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology (Savannah, Ga ), 9(08), 2207–2230. 10.4236/psych.2018.98126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ličen S., Prosen M. (2023). The development of cultural competences in nursing students and their significance in shaping the future work environment: A pilot study. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 819. 10.1186/s12909-023-04800-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi M., Zamanzadeh V., Valizadeh L., Khajehgoodari M., Ebrahimpour Rezaei M., Khalilzad M. A. (2020). The implementation of the nursing process in lower-income countries: An integrative review. Nursing Open, 7(1), 42–57. 10.1002/nop2.410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlambo M., Silén C., McGrath C. (2021). Lifelong learning and nurses’ continuing professional development, a metasynthesis of the literature. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 62. 10.1186/s12912-021-00579-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabizadeh-Gharghozar Z., Alavi N. M., Ajorpaz N. M. (2021). Clinical competence in nursing: A hybrid concept analysis. Nurse Education Today, 97, 104728. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notarnicola I., Stievano A., Barbarosa M., Gambalunga F., Iacorossi L., Petrucci C., Lancia L. (2018). Nurse competence scale: Psychometric assessment in the Italian context. Annali di Igiene, 30(6), 458–469. 10.7416/ai.2018.2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S., Gu M., Sok S. (2022). A concept analysis of Nurses’ clinical decision making: Implications for Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 19(6), 3596. 10.3390/ijerph19063596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldland E., Botti M., Hutchinson A. M., Redley B. (2020). A framework of nurses’ responsibilities for quality healthcare—exploration of content validity. Collegian, 27(2), 150–163. 10.1016/j.colegn.2019.07.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polit D. F., Beck C. T., Owen S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(4), 459–467. 10.1002/nur.20199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapin J., Pellet J., Mabire C., Gendron S., Dubois C. A. (2022). How does nursing-sensitive indicator feedback with nursing or interprofessional teams work and shape nursing performance improvement systems? A rapid realist review. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 177. 10.1186/s13643-022-02026-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues I. B., Adachi J. D., Beattie K. A., MacDermid J. C. (2017). Development and validation of a new tool to measure the facilitators, barriers and preferences to exercise in people with osteoporosis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 18(1), 540. 10.1186/s12891-017-1914-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen M. A., DiazGranados D., Dietz A. S., Benishek L. E., Thompson D., Pronovost P. J., Weaver S. J. (2018). Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. The American Psychologist, 73(4), 433–450. 10.1037/amp0000298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torkaman M., Sabzi A., Farokhzadian J. (2022). The effect of patient safety education on undergraduate nursing students’ patient safety competencies. Community Health Equity Research & Policy, 42(2), 219–224. 10.1177/0272684X20974214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci R., McClain B., Peyton L. (2022). Beyond a clinical ladder: A career pathway for professional development and recognition of oncology nurses. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 52(12), 659–665. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000001228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M. (2022). Sample size in quantitative instrument validation studies: A systematic review of articles published in Scopus, 2021. Heliyon, 8(12), e12223. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild D., Grove A., Martin M., Eremenco S., McElroy S., Verjee-Lorenz A., Erikson P. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in Health, 8(2), 94–104. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. V., Enskär K., Pua L. H., Heng D. G. N., Wang W. (2016). Development and psychometric testing of Holistic Clinical Assessment Tool (HCAT) for undergraduate nursing students. BMC Medical Education, 16, 1–9. 10.1186/s12909-016-0768-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Nilsson J., Zhang J., Engström M. (2021). Psychometric evaluation of nurse professional competence scale—short-form Chinese language version among nursing graduate students. Nursing Open, 8(6), 3232–3241. 10.1002/nop2.1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608241299275 for Transcultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Nursing Student Competence Scale (NSCS) by Amir Jalali, Fatemeh Chavoshani, Raheleh Rasad, Niloufar Darvishi, Fatemeh Merati Fashi, Mahbod Khodamorovati and Khalil Moradi in SAGE Open Nursing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-son-10.1177_23779608241299275 for Transcultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Nursing Student Competence Scale (NSCS) by Amir Jalali, Fatemeh Chavoshani, Raheleh Rasad, Niloufar Darvishi, Fatemeh Merati Fashi, Mahbod Khodamorovati and Khalil Moradi in SAGE Open Nursing