Abstract

Understanding the neurobiological mechanisms that regulate how the brain perceives the intoxicating effects of alcohol is highly relevant to understanding the development and maintenance of alcohol addiction. The basis for the subjective effects of intoxication can be studied in drug discrimination procedures in which animals are trained to differentiate the presence of internal stimulus effects of a given dose of ethanol (EtOH) from its absence. Research on the discriminative stimulus effects of psychoactive drugs has shown that these effects are mediated by specific receptor systems. In the case of alcohol, action mediated through ionotropic glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid, and serotonergic receptors concurrently produce complex, or multiple, basis for the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. These receptor systems may contribute differentially to the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH based on the EtOH dose, species differences, physiological states, and genetic composition of the individual. An understanding of the receptor mechanisms that mediate the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH can be used to develop medications aimed at decreasing the subjective effects associated with repeated intoxication. The goal of this symposium was to present an overview of recent findings that highlight the neurobiological mechanisms of EtOH’s subjective effects and to suggest the relevance of these discoveries to both basic and clinical alcohol research.

Keywords: Alcohol, Discriminative Stimulus, GABAA, Neurosteroid, NMDA, 5-HT3, mGluR5, Tolerance, Mice, Rats, Primates

Most drugs of abuse produce distinctive subjective effects in humans. These subjective, or interoceptive, effects are sensory in nature and differ from other drug effects in that they are part of conscious perception (Colpaert, 1987). An example is the feeling of “drunkenness” or relaxation that accompanies alcohol consumption. The subjective effects of opiates, psychomotor stimulants, hallucinogens, cannabinoids, and sedatives are all distinct from one another and mediated by distinct receptor systems (Glennon et al., 1991).

The pleasurable subjective effects of drugs are thought to increase abuse liability (Colpaert, 1987; Haretzen and Hickey, 1987; Stolerman, 1992). Examples of how the stimulus effects of drugs can “prime” or “reinstate” drug intake can be found in both the animal (de Wit and Stewart, 1981; Le et al., 1998; Vosler et al., 2001) and human (Palfai and Ostafin, 2003) literature, suggesting that the discriminative stimulus effects of drugs are an important determinant of self-administration. Moreover, the aversive stimulus effects of drug withdrawal (Gauvin et al., 1989, 1992) may increase abuse liability by negative reinforcement (Roberts et al., 2000). This suggests that alcoholic individuals might drink more, in part, owing to decreased sensitivity to ethanol’s (EtOH) stimulus effects. Importantly, the stimulus effects of alcohol are diminished in alcoholism (Jackson et al., 2001; Shapiro et al., 1980). Therefore, an understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms of EtOH’s stimulus effects has important implications for identifying factors that influence pathological behavioral processes in addiction.

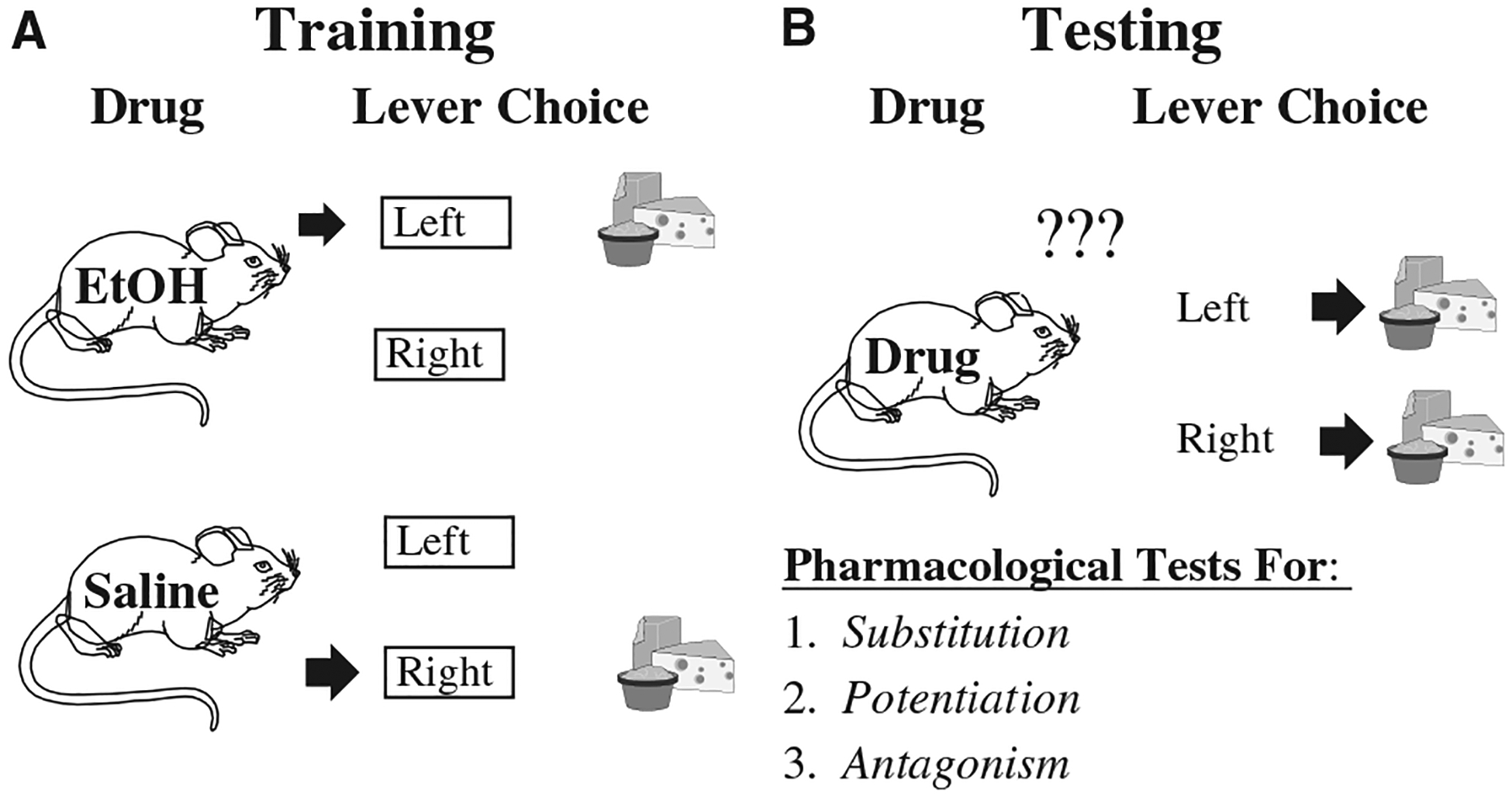

Using differential reinforcement procedures, drug discrimination experiments involve training animals to emit one response (i.e., a lever press) after administration of a specific dose of drug (i.e., called the training drug or training dose) and to emit a separate response after administration of its vehicle (Fig. 1A). There are a variety of ways to reinforce the discrimination, but the most common is the delivery of food to a food-restricted animal. The subjects are trained to a high degree of accuracy (i.e., 80–100% of responses emitted on the condition-appropriate lever). Once this discriminated performance is established, other doses of the training drug, or other drugs, are administered to determine whether they engender responding on the drug-appropriate lever (Fig. 1B). The extent to which a novel dose, or novel drug, produces responding on the lever associated with the training drug is used to determine the degree of substitution or generalization from the training stimulus. Commonly, if 80% or more of the session responses are on the drug-appropriate lever, the test substance is operationally defined as fully substituting for the training stimulus. The interpretation of these results is that a drug that produces high levels of substitution has very similar neurobiological mechanism(s) of action as the training drug. Novel drugs can also be tested for pharmacological potentiation or antagonism (Fig. 1B) of the discriminative stimulus effects of the training drug by conducting pretreatment experiments. These procedures offer powerful in vivo methods for identifying the neurobiological systems that mediate the subjective stimulus effects of EtOH, which may affect abuse liability.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the drug discrimination procedure. (A) Animals (i.e., mice, rats, primates) are trained by differential reinforcement to press a specific response lever after ethanol or vehicle injection (i.e., saline or water). Lever presses are reinforced by food or sucrose presentation only if they occur on the “correct” lever. Animals learn this discrimination after repeated training sessions and readily respond with greater than 80% accuracy. (B) Test sessions involve injecting a novel drug (or dose) and measuring lever selection. Responses on either lever produce reinforcement to avoid feedback about the correct response. Tests can reveal novel neurobiological mechanisms of ethanol.

Research has shown that the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH are multiply determined by glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonergic receptors (reviewed by Grant and Colombo, 1993; Kostowski and Bienkowski, 1999). These receptor systems may contribute differentially to the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH based on the EtOH dose, species differences, physiological states (i.e., menstrual cycle, tolerance, etc.), brain region, and genetic composition of the individual. The goal of this symposium was to present an overview of recent findings that highlight novel mechanisms of EtOH’s subjective effects and to suggest the relevance of these discoveries to both basic and clinical alcohol research. First, Erin Shannon and Dr. Kathleen Grant reviewed the conditions under which pregnane steroids, which are GABAA receptor–positive modulators, interact with the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. These factors include sex differences, species differences, and physiological states such as stress and menstrual cycle phase. Second, Dr. Donna Platt discussed work that has focused on the use of ligands selective for different α subunit-containing GABAA receptors as pharmacological tools to explore the role of these receptor subtypes in the discriminative stimulus effects of alcohol in squirrel monkeys trained to discriminate intravenously (i.v.) administered alcohol from saline. Third, Drs. Joyce Besheer and Clyde Hodge described research examining the role of metabotropic glutamate subtype-5 receptors (mGluR5) in the stimulus properties of investigator-administered and self-administered EtOH. Fourth, Drs. Howard Becker and Alicia Crissman reviewed a series of studies that examined the influence of chronic (intermittent vs continuous) EtOH exposure on sensitivity to the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH in C57BL/6J mice. Finally, Dr. Keith Shelton described research examining the neurochemical systems responsible for producing EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effects in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice and in mice that overexpress 5-HT3 receptors.

ENDOGENOUS NEUROSTEROIDS AND THE DISCRIMINATIVE STIMULUS EFFECTS OF EtOH IN MICE, RATS, AND MONKEYS

Erin E. Shannon and Kathleen A. Grant

Neurosteroids represent a class of endogenous compounds that can modulate GABAA, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), and σ1 receptors. This laboratory was interested in the behavioral significance of the neurosteroids pregnanolone (3α-hydroxy-5β-pregnan-20-one), allopregnanolone (3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one), and alloTHDOC (3β-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one) at the GABAA receptor. These steroids are 10 times more potent than diazepam and flurazepam and 200 times more potent than pentobarbital at potentiating Cl− flux at the GABAA receptor (Morrow and Paul, 1988). Behavioral evidence suggests that allopregnanolone, alloTHDOC, and pregnanolone all exhibit anxiolytic, sedative/hypnotic, anticonvulsant, and motor-incoordinating behavioral effects (Grant and Engel, 2001). Endogenously, these neurosteroids are involved in physiological normal states such as the regulation of sleep and response to stressful situations and also in disorders such as epilepsy, premenstrual stress disorder, depression, and drug abuse. The role that this endogenous system plays in the etiology of alcohol abuse and alcoholism has been the subject of much recent research.

One procedure that has provided an insight into the interaction between EtOH and neurosteroids is the drug discrimination procedure. In standard discrimination protocols, neurosteroids that are GABAA-positive modulators show substitution for EtOH in rats and mice (Ator et al., 1993; Bienkowski and Kostowski, 1997; Bowen et al., 1997; Bowen and Grant, 1999; Engel et al., 2001; Shelton and Grant, 2002). Further, EtOH substitutes for pregnanolone in rats (Engel et al., 2001). Cross-substitution between training drugs indicates a high degree of shared receptor mechanisms (Ator and Griffiths, 1989; Grant, 1999). Further, we have shown that the physiological state, such as the menstrual cycle phase, can alter the potency of neurosteroids to substitute for EtOH in cynomolgus monkeys (Grant et al., 1997). Finally, we have documented that there are wide individual differences in the ability of neurosteroids to produce EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects in monkey, rats, and mice (Bowen and Grant, 1999; Grant et al., 1997; Shannon et al., 2005). To further explore the genetic basis of the individual differences in neuropharmacological mechanisms involved in endogenous neurosteroid action, we investigated pregnanolone discrimination in inbred mice strains.

Specifically, the role of endogenous neurosteroids in the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH was examined in DBA/2J (D2) and C57BL/6J (B6) inbred mice. These 2 strains of mice exhibit contrasting EtOH-related behavioral phenotypes and are 2 of the founding strains of recombinant inbred (RI) strains used in alcohol research today. The initial study characterized an EtOH discrimination in both D2 and B6 male mice. The neurosteroid pregnanolone showed complete generalization from the EtOH stimulus cue in both strains of mice, indicating that an endogenous neurosteroid shared receptor-mediated mechanisms with EtOH (Shelton and Grant, 2002). To further examine the shared neuropharmacological mechanisms between neurosteroids and EtOH, a neurosteroid was trained as a discriminative stimulus in D2 and B6 mice.

D2 and B6 male and female mice were trained to discriminate 10 mg/kg pregnanolone from saline. In the previous study, 10 mg/kg pregnanolone was the lowest dose that engendered complete EtOH-appropriate responding in D2 and B6 male mice trained to discriminate 1.5 g/kg EtOH (Shelton and Grant, 2002). The male B6 mice had to be removed from the study because of increased occurrence of seizures, presumably because of the chronic pregnanolone treatment during discrimination training. The GABAA-positive modulators pentobarbital and midazolam completely substituted for pregnanolone, while the α1-preferring GABAA agonist zolpidem failed to substitute for pregnanolone in all groups of mice tested. The neuroactive steroids allopregnanolone, alloTHDOC, ganaxolone, androsterone, and epipregnanolone produced dose-dependent increases in pregnanolone-appropriate responding, although potency differences were observed among the neurosteroids. Pregnanolone’s discriminative stimulus cue also displayed a stereospecificity, as the 3α-pregnane steroids (allopregnanolone, pregnanolone) showed a similar potency for producing pregnanolone-appropriate responding while the 3β-pregnane steroids (epipregnanolone, epiallopregnanolone) showed a decreased potency in producing pregnanolone-appropriate responding, all of which agrees with in vitro data in which 3α-pregnane steroids act as GABAA-positive modulators while 3β-pregnane steroids are inactive at the GABAA receptor (Purdy et al., 1990).

Ethanol failed to substitute for pregnanolone in the male D2 and female B6 mice but did substitute for pregnanolone in the female D2 mice. It was hypothesized that differing endogenous levels of neurosteroids may be influencing the substitution of EtOH for pregnanolone and to further address this, a low-dose pregnanolone pretreatment was administered along with EtOH in the D2 male mice to observe whether pregnanolone could alter the substitution of EtOH. A 1.0 mg/kg pregnanolone pretreatment did potentiate the EtOH dose–response curve, and full substitution occurred when EtOH was administered with the low-dose pregnanolone pretreatment (E. E. Shannon, unpublished observation). The NMDA antagonists MK-801 and phencyclidine hydrochloride (PCP) and the 5-HT3 agonists SR 57727A and 1-(3-chlorophenyl)biguanide hydrochloride (CPBG) all failed to substitute for pregnanolone in all groups of mice tested. Overall, the discriminative stimulus cue produced by 10.0 mg/kg pregnanolone in D2 and B6 male and female mice appeared to be mediated through GABAA-positive modulation as evidenced by the substitution of a benzodiazepine, barbiturate, and the GABAergic neurosteroids allopregnanolone, alloTHDOC, ganaxolone, and androsterone (Shannon et al., 2005).

An additional dose of pregnanolone (5.6 mg/kg) was trained in D2 and B6 male mice in a drug discrimination procedure to evaluate whether the components of pregnanolone’s stimulus cue are altered at 2 different training doses. In general, at the lower training dose of pregnanolone, GABAA-positive modulation was still the primary receptor mechanism mediating the stimulus cue of pregnanolone in D2 and B6 male mice. Full substitution for pregnanolone’s stimulus cue occurred when tested with pentobarbital, midazolam, allopregnanolone, alloTHDOC, and androsterone. Ethanol, zolpidem, epiallopregnanolone, SR 57727A, and CPBG all failed to substitute for 5.6 mg/kg pregnanolone in both D2 and B6 mice (E. E. Shannon et al., in submission). One strain difference that emerged from this study was the substitution of the NMDA antagonists MK-801 and PCP. Both drugs fully substituted for pregnanolone in the D2 mice but failed to substitute in the B6 mice. Pregnanolone itself has no direct effect on NMDA responses but its sulfated form (pregnanolone sulfate) acts as a negative modulator of NMDA-induced currents (Park-Chung et al., 1994), suggesting that NMDA antagonists may substitute for pregnanolone if the pregnanolone training cue has undergone sulfation.

Overall, the data obtained from the pregnanolone discriminations trained in D2 and B6 mice indicate that GABAA-positive modulation is the primary receptor mechanism mediating the stimulus cue produced by pregnanolone, a mechanism that also mediates the stimulus cue produced by EtOH. It does not appear that EtOH and pregnanolone show cross-substitution in D2 and B6 mice as EtOH failed to substitute for pregnanolone in the majority of mice tested. The substitution of EtOH for pregnanolone could be influenced by endogenous levels of neurosteroids as a low-dose pregnanolone pretreatment did potentiate the substitution of EtOH for pregnanolone in D2 male mice. The stereospecificity of pregnanolone’s stimulus cue agrees with the data obtained from in vitro experiments, further supporting the use of drug discrimination to elucidate the in vivo receptor mechanisms responsible for mediating the stimulus cues of a drug.

ROLE OF GABAA RECEPTOR SUBTYPES IN THE DISCRIMINATIVE STIMULUS EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL IN MONKEYS

Donna M. Platt

Ethanol’s ability to enhance GABA neurotransmission via GABAA receptors has been implicated as an important mechanism underlying its subjective effects in humans and discriminative stimulus effects in animals. Molecular biological studies have demonstrated that the GABAA receptor is a pentamer consisting of subunits from at least 5 different families, and most native mammalian GABAA receptors are composed of 2 α-, 2 β-, and γ-subunit (McKernan and Whiting, 1996; Pritchett et al., 1989; Rudolph et al., 2001). Results from behavioral studies in animals support a key role for specific subtypes of the GABAA receptor in the effects of EtOH related to its abuse (e.g., Blednov et al., 2003; Cook et al., 2005; Foster et al., 2004; Harvey et al., 2002; McKay et al., 2004).

The purpose of these studies was to explore the role of GABAA receptor subtypes in mediating the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. Squirrel monkeys were trained to discriminate i.v.-administered EtOH (1.0 g/kg) from saline under a 10-response fixed-ratio schedule of food delivery. The i.v. route of administration was chosen to avoid taste cues that could interfere with the stimulus control of behavior by pharmacological cues (Duka et al., 1999). Our strategy was to assess the ability of benzodiazepine-type compounds with known selectivity and efficacy profiles to mimic and/or modulate the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. We first evaluated the relative contribution of α1 subunit–containing GABAA receptors (α1GABAA receptors) and α5 subunit–containing GABAA receptors (α5GABAA receptors) to the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. The α1GABAA-selective benzodiazepine receptor agonists zolpidem, CL 218872, and zaleplon (Atack et al., 1999; Damgen and Luddens, 1999; Huang et al., 2000) partially to fully substituted for the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH, engendering maxima of 57% to 100% EtOH-lever responding. High doses of these compounds also reliably reduced response rates. Interestingly, compounds that were less selective for α1GABAA versus α5GABAA receptors tended to be more likely to substitute for EtOH, suggestive of a potentially important role for the α5GABAA receptor subtype in EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effects. This hypothesis was supported by the observation that the α5GABAA-selective agonists QH-ii-066 and panadiplon (Huang et al., 1996; Lameh et al., 2000) engendered full EtOH-like responding at doses that did not markedly alter rates of responding.

As a follow-up to the drug substitution studies, we conducted antagonism studies with compounds selective for either α1GABAA or α5GABAA receptor subtypes. The α1GABAA-selective antagonist β-CCt (3.0 mg/kg; Huang et al., 2000) failed to alter the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH itself or the EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects of zolpidem. β-CCt did produce, however, a modest (3-fold) rightward shift in the zaleplon dose–response function. Altogether, these findings suggest little or no role for α1GABAA receptors in mediating the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH or the EtOH-like effects of benzodiazepine-type agonists.

In contrast, administration of the α5GABAA-selective inverse agonists RY-23 and L-655708 (Casula et al., 2001; June et al., 2001) completely attenuated the EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects of QH-ii-066. Attenuation was observed with doses of RY-23 and L-655708 that appeared to retain selectivity for α5GABAA receptors, based on the observation that doses of the inverse agonists that reliably blocked the EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects of QH-ii-066 failed to alter the EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects of zolpidem, a compound with no appreciable affinity at α5GABAA receptors. Finally, L-655708 also attenuated the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH itself. These results suggest that action at the α5GABAA receptor subtype may play a key role in the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH and the EtOH-like effects of benzodiazepine agonists.

It should be noted, however, that the dose of L-655708 that reliably altered the EtOH dose–response function was 3-fold higher than that required to alter the QH-ii-066 dose–response function. This finding raises the possibility that GABAA receptors, in addition to α5GABAA receptors, may also play a role in mediating the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. To evaluate this hypothesis, we determined the degree to which JC-510 reproduced the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. JC-510 is a benzodiazepine-type compound that displays selective efficacy (i.e., functional selectivity) rather than selective affinity at particular GABAA receptor subtypes. Specifically, based on the ability of JC-510 to modulate GABA-mediated chloride flux in vitro, this compound has little to no measurable efficacy at α1GABAA and α5GABAA receptors but is a full agonist at α2GABAA and α3GABAA receptors (J. M. Cook, personal communication). When evaluated in the EtOH-trained squirrel monkeys, JC-510 fully mimicked the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH.

Our findings suggest that α5GABAA, and possibly α2,3GABAA, receptor mechanisms play a specific and more prominent role than α1GABAA receptor mechanisms in the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH and the EtOH-like effects of benzodiazepine agonists. α5 subunit–containing GABAA receptors comprise only a small population of GABAA receptors and are found primarily in the hippocampus (McKernan and Whiting, 1996), a brain region shown to mediate, at least in part, memory processes linked to the learning of affective states associated with drug intake (Berke and Eichenbaum, 2001). These findings raise the possibility that the effectiveness of α5GABAA inverse agonists at blocking the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH may be related to their ability to modulate affective states associated with alcohol use. α2,3 subunit–containing GABAA receptors, in contrast, are located largely in structures of the limbic system associated with anxiety regulation (Rudolph et al., 2001) suggesting, perhaps, that the shared discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH and benzodiazepine agonists may reflect a common ability to engender anxiolytic-like effects. Regardless of the psychopharmacological mechanisms underlying the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH, our findings support α5GABAA and/or α2,3GABAA receptors as promising targets for pharmacological management of the interoceptive effects of EtOH.

INTERACTION BETWEEN mGluR5 AND GABAA RECEPTORS IN THE DISCRIMINATIVE STIMULUS EFFECTS OF EtOH

Joyce Besheer and Clyde W. Hodge

The discriminative stimulus properties of EtOH are mediated in part by positive modulation of GABAA receptors. Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 activity has the potential to influence EtOH discrimination based on evidence that mGluR5 can influence GABA neurotransmission (de Novellis et al., 2003; Diaz-Cabiale et al., 2002; Hoffpauir and Gleason, 2002). Further, MGlu5 receptors are abundant in limbic brain regions such as the nucleus accumbens, cortex, and hippocampus (Bordi and Ugolini, 1999; Romano et al., 1995; Spooren et al., 2001) where GABAA receptors are known to modulate EtOH discrimination (Besheer et al., 2003; Hodge and Cox, 1998; Hodge et al., 2001b).

The purpose of this initial study was to examine the potential involvement of mGluR5 in the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH. Rats were trained to discriminate EtOH (1 g/kg IG) from water using standard 2-lever operant procedures. Briefly, after EtOH administration responses on a designated lever (e.g., right lever) produce access to sucrose reinforcement and after water administration responses on the other lever (e.g., left lever) produce access to sucrose reinforcement. A selective noncompetitive antagonist of mGluR5, 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP) did not produce EtOH-like stimulus properties at any dose tested [0–50 mg/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.)], as there was little to no responding on the EtOH-appropriate lever. Pretreatment with MPEP (30 mg/kg) reduced the stimulus properties of EtOH as indicated by significant reductions in EtOH-appropriate responding, specifically at 0.5 and 1 g/kg EtOH and a failure of EtOH test doses (1 and 2 g/kg) to fully substitute for the EtOH training dose. Next, the ability of MPEP to modulate pentobarbital and diazepam substitution for EtOH was assessed. Pentobarbital substitution (1–10 mg/kg i.p.) for EtOH was not altered by MPEP pretreatment. However, a pharmacological interaction between MPEP and pentobarbital was evident as MPEP enhanced the response rate-reducing effects of pentobarbital. The EtOH-like stimulus properties of diazepam (5 mg/kg) were significantly inhibited by MPEP pretreatment, as full substitution for EtOH was prevented. These findings suggest that mGluR5 antagonism inhibited the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH specifically by reducing, or otherwise interfering with, the component of EtOH discrimination that is mediated by benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA receptors.

To examine a potential anatomical basis for these pharmacological findings, immunohistochemistry was performed on the rat brain tissue at the end of the discrimination experiment. Dual-label immunofluorescence visualized by confocal microscopy was used to assess the expression patterns of mGluR5 and benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA α1-containing receptors. Consistent with the literature, the nucleus accumbens expressed both GABAA α1 and mGluR5. GABAA α1 projections from the nucleus accumbens could be traced to the ventral pallidum, where a different expression pattern was observed. That is, not only were mGluR5 and GABAA α1 expressed in the ventral pallidum, but they were also coexpressed on some of the same cells within that region. A similar expression pattern was observed in the globus pallidus and in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and the basolateral amygdala, both of which are regions known to mediate the discriminative stimulus properties of EtOH. Together, these findings suggest that mGluR5 and benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA receptors may interactively modulate neural circuits among brain regions or within brain regions to modulate the discriminative stimulus properties of EtOH.

Given the ability of mGluR5 antagonism to inhibit the discriminative stimulus properties of investigator-administered EtOH, another group of rats was used to assess the role of mGluR5 and mGluR1 in modulating the discriminative stimulus properties of self-administered EtOH (e.g., Hodge et al., 2001a). Both mGluR1 and mGluR5 belong to the Group I family of mGluRs and share common agonist pharmacological profiles and are coupled to similar signal transduction pathways, but are abundant in different brain regions, with greater expression of mGluR5 in cortiolimbic regions than mGluR1, which is highly abundant in the cerebellum (Romano et al., 1995; Shigemoto et al., 1992). The procedure used to assess the effects of self-administered EtOH involved training animals to discriminate the stimulus properties of EtOH (1 g/kg) from water using the standard 2-lever operant training procedures described above. On test days, water was administered to the animal, and responses on both levers were reinforced. However, EtOH (10% volume in volume) was added to the sucrose reinforcement. In short, during the initial part of the test session, animals responded on the water-appropriate lever. However, as the session proceeded, the subjective effects of the consumed reinforcement (i.e., sweetened EtOH) were detected in the animal. Accordingly, responding shifted primarily to the EtOH-appropriate lever. Under saline pretreatment conditions, approximately 15 minutes into the test session, greater than 80% of the total responses occurred on the EtOH-appropriate lever (i.e., full substitution). Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 antagonism by MPEP (10 mg/kg) significantly delayed EtOH-appropriate responding, with full substitution for the 1 g/kg EtOH training dose observed during the final 5 minutes of the session (25 minutes). In contrast, mGluR1 antagonism by CPCCOEt (1–10 mg/kg) did not alter the pattern of test session responding. Importantly, both mGluR5 and mGluR1 antagonism did not alter the number of reinforcers consumed. Thus, given that the amount of consumed EtOH did not differ, this data pattern indicates that mGluR5, but not mGluR1 antagonism, inhibited the discriminative stimulus properties of self-administered EtOH.

In the present work, mGluR5 was introduced as a novel mechanism of EtOH discrimination (Besheer and Hodge, 2005). Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 antagonism was found to inhibit the discriminative stimulus properties of investigator-administered EtOHand self-administered EtOH. Given that recent work has shown that antagonism of mGluR5 by MPEP reduces EtOH self-administration as well as relapse to EtOH-taking in alcohol-preferring (P) rats (Schroeder et al., 2005), the present work suggests a specific behavioral mechanism for these behaviors. That is, mGluR5 antagonism appears to reduce the discriminative stimulus (i.e., subjective) properties of EtOH, which may contribute to reductions in chronic drinking or excessive consumption during relapse. Given that the subjective effects of drugs of abuse play an important role in the onset and maintenance of drug-taking behavior (Stolerman, 1992), examination of the discriminative stimulus effects of drugs is essential for the development of effective pharmacotherapies to aid in the treatment of drug abuse-related disorders.

TOLERANCE TO THE DISCRIMINATIVE STIMULUS PROPERTIES OF EtOH IN MICE

Howard C. Becker and Alicia M. Crissman

A significant consequence of chronic EtOH exposure is the development of tolerance, which has been suggested to be one of many factors that contribute to the perpetuation of EtOH drinking and abuse. In this light, it is surprising that relatively few studies have investigated whether tolerance develops to the discriminative stimulus (subjective) effects of EtOH. Although the relationship between the discriminative stimulus properties of EtOH and its reinforcing effects is not entirely clear (Duka et al., 1999), this issue is of clinical relevance as an alteration in EtOH discriminability resulting from chronic EtOH exposure may have a significant influence on the propensity to drink. That is, reduced ability to detect or perceive EtOH’s subjective (intoxicating) effects may lead (contribute) to an escalation in EtOH consumption.

We recently demonstrated reduced sensitivity (tolerance) to the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH following chronic exposure to the drug in C57BL/6J mice (Crissman et al., 2004). This corroborates findings in another study using rats (Emmett-Oglesby, 1990). A key procedural feature of these studies is that chronic EtOH exposure was administered outside the context of discrimination training and testing. The present study was conducted to further explore this apparent tolerance effect observed in our initial findings using C57BL/6J mice, by examining whether the amount and/or pattern of chronic EtOH exposure influences subsequent sensitivity to EtOH’s discriminative cue.

The general study design and procedure entailed the following 4 experimental phases: EtOH discrimination training, baseline EtOH generalization testing, chronic EtOH treatment, and retesting for EtOH generalization. First, adult male C57BL/6J mice were trained to discriminate between 1.5 g/kg EtOH and saline using a 2-lever operant (FR-20) food-reinforcement procedure similar to that described previously (Becker et al., 2004). Ethanol or saline was administered (i.p.) 5 minutes prior to the 15-minute training sessions. Once criterion discrimination was achieved ( ≥ 85% correct responding, 8/10 consecutive days), generalization testing was conducted to establish a baseline EtOH dose–effect function. Mice were then randomly assigned to chronic EtOH or control conditions and treated as described below. At 24 hours following chronic EtOH treatment, mice were retested for EtOH discrimination. A cumulative dosing procedure was used to generate EtOH dose–effect curves to allow for maximal information to be obtained within a limited time period following chronic EtOH exposure. Briefly, mice received an injection (i.p.) of saline followed by repeated injections of EtOH (0.5 g/kg) to yield test doses for EtOH (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 g/kg), with a 5-minute pretreatment time and 2-minute testing periods (responding on either lever reinforced). Mice were acclimated to this cumulative dosing test procedure by repeated testing with saline followed by administration of the training dose (1.5 g/kg EtOH).

Chronic EtOH exposure was accomplished through use of the inhalation route, as described previously (Crissman et al., 2004). Discrimination training sessions were suspended while animals were exposed to chronic EtOH vapor or air in the inhalation chambers. Ethanol-exposed animals were further separated based on the pattern of chronic exposure. One group [multiple withdrawal (MW) group] received chronic intermittent EtOH exposure (with multiple intervening periods of withdrawal), while the remaining mice [continuous exposure (CE) group] received the same total amount of EtOH exposure, but in a continuous fashion. The number of cycles (intermittent exposure) and duration of exposure (CE) were systematically increased, but designed to equate the total amount of EtOH exposure for MW and CE conditions. That is, MW mice received 1, 2, 3, or 4 cycles of 16 hours of exposure to EtOH vapor in inhalation chambers, with each cycle separated by an 8-hour period of withdrawal (MW×1, MW×2, MW×3, and MW×4 conditions, respectively). In contrast, CE mice were exposed to 16, 32, 48, or 64 hours of EtOH vapor, with no interruption (CE/16, CE/32, CE/48, and CE/64 conditions, respectively). Ethanol concentration in the inhalation chambers was adjusted to yield blood EtOH levels in the range of 150–200 mg/dL. A control (CTL) group received similar handling as MW and CE groups, but did not receive chronic EtOH exposure.

Baseline EtOH generalization testing yielded consistent EtOH dose–effect curves in all groups (calculated ED50 values, 0.86 ± .04 g/kg). Analysis of response rates indicated a significant decrease only at the highest (2.5 g/kg) EtOH dose (p<0.01). Generalization testing conducted in animals following air exposure in control inhalation chambers (CTL group) produced similar EtOH dose–effect curves (ED50 values, 0.76 ± .04 g/kg) that did not significantly differ from baseline.

In contrast, a single 16-hour bout of EtOH exposure (MW×1 group) resulted in a significant shift to the right in the EtOH dose–effect function 24 hours after removal from the inhalation chambers. This resulted in a nearly 2-fold increase in the ED50 value for the MW×1 group (1.11 ± .04 g/kg) compared with the CTL group (p<.0.01). This apparent tolerance to EtOH discriminability was evident following an increased number of chronic intermittent EtOH exposures (ED50 values for MW×2, MW×3, and MW×4 groups: 1.01 ± 0.5, 1.04 ± .05, and 1.39 ± .06 g/kg, respectively). Analysis revealed that the calculated ED50 values for all MW groups were significantly greater than that for the CTL condition and that this tolerance effect was significantly greater in the MW×4 condition compared with all other MW groups (p<0.001). An independent group of mice that were tested following a single 16-hour bout of EtOH vapor exposure (CE/16 group) revealed a similar shift to the right in the EtOH dose–effect function that produced a significantly greater ED50 value (1.05 ± .01 g/kg) compared with the CTL condition (0.76 ± .04 g/kg). The magnitude of this tolerance effect was further amplified by increasing the duration of chronic EtOH exposure (ED50 values for CE/32, CE/48, and CE/64 groups: 1.32 ± 0.6, 1.37 ± .02, and 1.41 ± .08 g/kg, respectively). Analysis revealed tolerance (significantly higher ED50 values) for all CE conditions in comparison with the CTL condition, with the magnitude of tolerance greater for CE/64, CE48, and CE/32 conditions in comparison with the CE/16 condition.

Overall, generalization testing in CTL mice revealed accurate discrimination performance at EtOH doses close to the training dose (1.5 g/kg EtOH). In contrast, sensitivity to the EtOH cue was blunted in both MW and CE conditions, although this apparent tolerance to EtOH’s discriminative cue was overcome by higher test doses of EtOH. Thus, as the rightward shift in the EtOH dose–effect curves indicated that higher doses of EtOH were required for MW and CE mice to detect the EtOH cue, accurate discrimination performance was achieved with the highest (2.5 g/kg) dose of EtOH for all groups. Analysis of response rate data indicated a general decrease as the test dose of EtOH increased, but this effect did not systematically vary as a function of chronic EtOH exposure in MW or CE conditions.

In summary, results from this study confirm our earlier report of tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH following chronic exposure to the drug in C57BL/6J mice (Crissman et al., 2004). These results also indicate that the reduction in sensitivity to EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effect is evident whether chronic EtOH exposure is administered in an intermittent or continuous fashion. Further, the magnitude of tolerance to EtOH discriminability appears to increase with an increase in the number of chronic intermittent EtOH exposures or the duration of continuous EtOH exposure. Future studies are planned to investigate the neuropharmacological basis for this apparent tolerance effect, as well as the potential relationship of this effect with demonstrated changes in EtOH self-administration behavior following chronic exposure to the drug (Becker and Lopez, 2004).

GENETIC DETERMINANTS OF EtOH DISCRIMINATION AND OTHER BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES

Keith L. Shelton

Inbred and transgenic mice are becoming increasingly important tools for exploring the genetic and neurochemical determinants of EtOH-mediated behaviors. To date, very few experiments have been conducted examining the effects of strain or genetic manipulations on complex, learned operant behaviors such as drug discrimination. With more relevant transgenic strains becoming available and increasingly powerful behavioral genetics techniques being developed for exploring the loci of other EtOH-mediated behaviors in inbred mice, the use of these animals for examining the neurochemistry underlying the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH as well as the effect of genetic background on EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effects is certainly warranted.

Potential uses of inbred and transgenic mice in drug discrimination research were examined in a series of 3 studies. In the first 2 experiments, the neurochemical substrates responsible for producing EtOH’s discriminative stimulus were compared in C57BL/6J (B6) and DBA/2J (D2) mice (Shelton and Grant, 2002; Shelton 2004). B6 and D2 mice differ widely in their responsiveness to EtOH in a number of assays and are the basis for a panel of RI strains used for quantitative trait loci analysis of EtOH-mediated behaviors (Crabbe, 2002; Crabbe et al., 1999; Crawley et al., 1997). As such, they seemed the most likely candidates as a starting point for determining whether genetic background affects the transduction of EtOH’s discriminative stimulus.

Adult male B6 and D2 mice were trained to discriminate 1.5 g/kg EtOH from saline in a standard 15-minute drug discrimination procedure. Substitution test sessions were conducted on Tuesdays and Fridays, provided that the mice exhibited acceptable stimulus control on the intervening training sessions. In the first study, the training procedure was specifically designed to determine whether B6 and D2 mice differed in the time necessary to acquire the EtOH versus saline discrimination (Shelton and Grant, 2002). It was found that D2 mice required a significantly shorter period of time to acquire the discrimination than did B6 mice. This finding is consistent with the observation that D2 mice are more sensitive to many of the behavioral effects of EtOH than are B6 mice (Crabbe et al., 1982; Cunningham et al., 1992; Gallaher et al., 1996; Risinger and Cunningham, 1992).

Following acquisition of the EtOH discrimination, a number of positive GABAA modulators and NMDA antagonists known to have EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects in rats were examined for their substitution profiles in B6 and D2 mice. The benzodiazepines midazolam and diazepam and the positive GABAA neurosteroid preganolone produced similar levels of full or nearly full substitution for EtOH in both B6 and D2 mice. The barbiturate pentobarbital was significantly more potent in producing EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects in B2 than B6 mice. Midazolam, but not diazepam, was significantly more potent in suppressing response rates in D2 than B6 mice, while moderate doses of pentobarbital had a response rate–increasing effect in B6 mice that was not apparent in D2 mice. The noncompetitive NMDA antagonists dizocilpine (MK-801), PCP, and ketamine were also examined in both strains. There were no differences in the substitution profiles of dizocilpine and PCP between strains, with both drugs producing almost identical levels of nearly complete substitution. Only ketamine produced differential levels of substitution between strains, with B6 mice exhibiting 82% EtOH-lever responding versus 51% EtOH-appropriate responding in D2 mice. Moderate doses of both PCP and ketamine produced large increases in response rates in B6 but not D2 mice, while the more potent and selective uncompetitive NMDA antagonist dizocilpine decreased rates of responding in both strains. The competitive NMDA antagonist, CPPene, produced similar levels of partial substitution and no differences in response-rate suppression between B6 and D2 mice. Drugs from other classes including cocaine, morphine, and GHB produced no EtOH-like effects in either strain and no consistent differences in response-rate suppression.

Overall the results from these 2 studies indicate that the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH in B6 and D2 mice are qualitatively similar and mediated by both GABAergic and NMDA receptor substrates. This result is consistent with the findings from numerous other studies in mice, rats, and primates (Grant et al., 1991; Sanger, 1993; Shelton & Balster, 1994; Winter, 1975). In contrast, substantial differences were apparent between strains in the degree to which a number of different drugs altered operant response rates. This suggests that operant assays are sensitive to and can distinguish among a number of different drug’s effects and may therefore be a valuable aid in behavioral phenotyping.

In a third experiment, transgenic mice were used to more thoroughly examine the role of 5-HT3 receptors in modulating EtOH’s discriminative stimulus. Some studies have shown that 5-HT3 antagonists will attenuate EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effects, while other experiments have failed to replicate these findings (Bienkowski et al., 1997; Grant and Barrett, 1991; Mhatre et al., 2001; Middaugh et al., 2000; Stefanski et al., 1996). Mice that had been engineered to overexpress 5-HT3 receptors in the forebrain (Engel et al., 1998) as well as limbic areas shown to be critical in transducing EtOH’s discriminative stimulus (Hodge and Cox 1998; Hodge et al., 1995) were trained to discriminate EtOH from saline. It was theorized that by enhancing functional 5-HT3 receptor numbers, the role of these receptors in modulating EtOH’s discriminative stimulus might be more pronounced. Groups of B6SJL/F1 wild-type (WT) and 5-HT3-overexpressing (OE) mice were trained to discriminate 1.5 g/kg i.p. EtOH from saline in a standard 15 min/day training procedure. Wild-type and OE mice learned the EtOH discrimination in a similar number of training sessions, and there was no difference between strains in the substitution profile or response-rate suppression effects of a range of EtOH doses. Midazolam and dizocilpine fully substituted for EtOH in both WT and OE strains, with no differences in substitution potency. Dizocilpine was more potent in suppressing operant response rates in OE than WT mice. Tests with cocaine and the mixed 5-HT1B/2C agonist mCPP failed to produce any EtOH-like discriminative stimulus effects or differences in response-rate effects between the strains. The 5-HT3 antagonists MDL-72222 and ondansetron failed to attenuate EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effect in either strain. The putative 5-HT3 agonists MD-354 and YC-30 failed to substitute for EtOH when administered alone and YC-30 failed to shift the EtOH dose–effect curve. Taken as a whole, these data suggest that even in animals with dramatically enhanced numbers of 5-HT3 receptors, these receptors play at best a minor role in modulating EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effects.

In conclusion, the 3 studies presented highlight the promise as well as the limitations of using selectively bred and transgenic mice as tools in drug discrimination research. While the present data do not indicate major differences underlying the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH in B6 and D2 mice, many other differences in drug effects between strains were apparent which warrant additional investigation. It is certainly also possible that other inbred strains of mice may transduce EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effects differently than the strains examined. Likewise, 5-HT3 receptor overexpression had little impact on EtOH’s discriminative stimulus, but the present study does demonstrate the feasibility of using transgenic mice to examine the neurochemical systems underlying EtOH’s discriminative stimulus effects. Conditional and inducible knockout technology targeted at systems more critical to EtOH’s discriminative stimulus is likely to make this avenue of exploration even more appealing in the future.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The subjective stimulus effects of drugs are important determinants of abuse liability. Alcohol produces distinct stimulus effects in humans that can be modeled in animals and studied with drug discrimination methods. The purpose of this symposium was to review recent evidence on the neurobiological mechanisms of EtOH discrimination and to highlight the relevance of these findings to basic and clinical research. First, the role played by endogenous neurosteroids in the etiology of alcohol abuse and alcoholism has been the subject of much recent research. Erin Shannon and Dr. Kathleen Grant described how pregnane steroids act through GABAA receptor mechanisms to produce EtOH’s stimulus effects. Second, emerging evidence indicates that combinations of different molecular subunits of GABAA receptors may confer differential function and involvement in EtOH’s biobehavioral effects. To address this issue, Dr. Donna Platt discussed work suggesting that α5GABAA, and possibly α2,3GABAA, receptor mechanisms play a specific and more prominent role than α1GABAA receptor mechanisms in the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH and the EtOH-like effects of benzodiazepine agonists. Third, many of EtOH’s neurobiological effects are known to be modulated by ionotropic glutamate receptors but evidence is lacking on the role of the metabotropic glutamate receptor system. Drs. Joyce Besheer and Clyde Hodge described research showing that mGlu5 receptors modulate the discriminative stimulus effects of investigator-administered and self-administered EtOH, which suggests that mGluR5 antagonists may decrease drinking by altering the stimulus effects of alcohol. Fourth, a primary consequence of chronic EtOH exposure is the development of tolerance. In this symposium, Drs. Howard Becker and Alicia Crissman presented evidence showing that tolerance develops to the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH following exposure to the drug. These data suggest that diminished subjective effects of EtOH that occur with chronic drinking may contribute to increased EtOH drinking and abuse. Finally, inbred C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice have become important tools for evaluating neurobiological and genetic mechanisms of alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Dr. Keith Shelton presented evidence showing that the discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH in B6 and D2 mice are qualitatively similar and mediated by both GABAergic and NMDA receptor substrates. These data suggest that differential EtOH sensitivity between these 2 mouse strains may not be related to differential discriminative stimulus effects of EtOH and raises questions as to why the 2 strains differ on other measures, such as self-administration and conditioned place preference. In conclusion, this symposium highlighted novel research findings that address neurobiological mechanisms of EtOH discrimination. Defining how the brain perceives alcohol is fundamental to an understanding of alcohol abuse and alcoholism, and may lead to new approaches for medications development.

REFERENCES

- Atack JR, Smith AJ, Emms F, McKernan RM (1999) Regional differences in the inhibition of mouse in vivo [3H]Ro 15–1788 binding reflect selectivity for 1 versus 2 and 3 subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 20:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ator NA, Grant KA, Purdy RH, Paul SM, Griffiths RR (1993) Drug discrimination analysis of endogenous neuroactive steroids in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 241:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ator NA, Griffiths RR (1989) Asymmetrical cross-generalization in drug discrimination with lorazepam and pentobarbital training conditions. Drug Dev Res 16:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Crissman AM, Studders S, Kelley BM, Middaugh LD (2004) Differential neurosensitivity to the discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol in C57BL/6J and C3H/He mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:712–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF (2004) Increased ethanol drinking after repeated chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal experience in C57BL/6 mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:1829–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke JD, Eichenbaum HB (2001) Drug addiction and the hippocampus. Science 294:1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besheer J, Cox AA, Hodge CW (2003) Coregulation of ethanol discrimination by the nucleus accumbens and amygdala. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27:450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besheer J, Hodge CW (2005) Pharmacological and anatomical evidence for an interaction between mGluR5- and GABA(A) alpha1-containing receptors in the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Neuropsychopharmacology 30:747–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Koros E, Piasecki J, Kostowski W (1997) Interactions of ethanol with nicotine, dizocilpine, CGP 40,116 and 1-(m-chlorophenyl)-biguanide in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 58:1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Kostowski W (1997) Discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol in the rat: effects of neurosteroids and picrotoxin. Brain Res 753:348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Walker D, Alva H, Creech K, Findlay G, Harris RA. (2003) GABAA receptor alpha 1 and beta 2 subunit null mutant mice: behavioral responses to ethanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 305:854–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordi F, Ugolini A (1999) Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors: implications for brain diseases. Prog Neurobiol 59:55–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen CA, Gatto GJ, Grant KA (1997) Assessment of the multiple discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol using an ethanol-pentobarbital-water discrimination in rats. Behav Pharmacol 8:339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen CA, Grant KA (1999) Increased specificity of ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects in an ethanol-pentobarbital-water discrimination in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 55:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casula MA, Bromidge FA, Pillai GV, Wingrove PB, Martin K, Maubach K, Seabrook GR, Whiting PJ, Hadingham KL (2001) Identification of amino acid residues responsible for the alpha-5 subunit binding selectivity of L-655,708 a benzodiazepine binding site ligand at the GABA-A receptor. J Neurochem 77:445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC (1987) Drug discrimination: methods of manipulation, measurement, and analysis. in Methods of assessing the reinforcing properties of abused drugs (Bozarth MA ed), pp 341–372. Springer-Verlag, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JB, Foster KL, Eiler WJA, McKay PF, Woods J, Harvey SC, Garcia M, Grey C, McCane S, Mason D, Cummings R, Li X, Cook JM, June HL (2005) Selective GABAA α5 benzodiazepine inverse agonist antagonizes the neurobehavioral actions of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:1390–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC (2002) Genetic contributions to addiction. Annu Rev Psychol 53:435–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Janowsky JS, Young ER, Kosobud A, Stack J, Rigter H (1982) Tolerance to ethanol hypothermia in inbred mice: genotypic correlations with behavioral responses. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 6: 446–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Buck KJ, Cunningham CL, Belknap JK (1999) Identifying genes for alcohol and drug sensitivity: recent progress and future directions. Trends Neurosci 22:173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Belknap JK, Collins A, Crabbe JC, Frankel W, Henderson N, Hitzemann RJ, Maxson SC, Miner LL, Silva AJ, Wehner JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Paylor R (1997) Behavioral phenotypes of inbred mouse strains: implications and recommendations for molecular studies. Psychopharmacology 132:107–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissman AM, Studders SL, Becker HC (2004) Tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol following chronic inhalation exposure to ethanol in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Pharmacol 15: 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Niehus DR, Malott DH, Prather LK (1992) Genetic differences in the rewarding and activating effects of morphine and ethanol. Psychopharmacology 107:385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgen K, Luddens H (1999) Zaleplon displays a selectivity to recombinant GABA-A receptors different from zolpidem, zopiclone and benzodiazepines. Neurosci Res Commun 25:139–148. [Google Scholar]

- de Novellis V, Marabese I, Palazzo E, Rossi F, Berrino L, Rodella L, Bianchi R, Maione S (2003) Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid release in the periaqueductal grey of rats. Eur J Pharmacol 462:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J (1981) Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology 75:134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Cabiale Z, Vivo M, Del Arco A, O’Connor WT, Harte MK, Muller CE, Martinez E, Popoli P, Fuxe K, Ferre S (2002) Metabotropic glutamate mglu5 receptor-mediated modulation of the ventral striopallidal GABA pathway in rats. Interactions with adenosine A(2A) and dopamine D (2) receptors. Neurosci Lett 324:154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duka T, Jackson A, Smith DC, Stephens DN (1999) Relationship of components of an alcohol interoceptive stimulus to induction of desire for alcohol in social drinkers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64: 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmett-Oglesby MW, Shippenberg TS, Herz A (1988) Tolerance and cross-tolerance to the discriminative stimulus properties of fentanyl and morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut 245:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SR, Lyons CR, Allan AM (1998) 5-HT3 receptor over-expression decreases ethanol self administration in transgenic mice. Psychopharmacology 140:243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SR, Purdy RH, Grant KA (2001) Characterization of discriminative stimulus effects of the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KL, McKay PF, Seyoum R, Milbourne D, Yin W, Sarma PVVS, Cook JM, June HL (2004) GABAA and opioid receptors of the central nucleus of the amygdale selectively regulate ethanol-maintained behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:269–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher EJ, Jones GE, Belknap JK, Crabbe JC (1996) Identification of genetic markers for initial sensitivity and rapid tolerance to ethanol-induced ataxia using quantitative trait locus analysis in BXD recombinant inbred mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277:604–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvin DV, Harland RD, Criado JR, Michaelis RC, Holloway FA (1989) The discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol and acute ethanol withdrawal states in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 24:103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvin DV, Youngblood BD, Holloway FA (1992) The discriminative stimulus properties of acute ethanol withdrawal (hangover) in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 16:336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon RA, Jarbe TU, Frankenheim J eds (1991) Drug Discrimination: Applications to Drug Abuse Research, Vol 116. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph Series. National Institute of Health, Bethesda. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA (1999) Strategies for understanding the pharmacological effects of ethanol with drug discrimination procedures. Pharm Biochem Behav 64:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Azarov A, Shively CA, Purdy RH (1997) Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol and 3a-hydroxy-5a-pregnan-20-one in relation to menstrual cycle phase in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Psychopharmacology 130:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Barrett JE (1991) Blockade of the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology 104:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Colombo G (1993) Pharmacological analysis of the mixed discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Alcohol Alcoholism (Suppl 2): 445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Engel SR (2001) Neurosteroids and behavior. in Neurosteroids and brain function (Biggio G, Purdy RH eds), pp 321–342. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KK, Knisely JJ, Tabakoff BB, Barrett JJ, Balster RL (1991) Ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of non-competitive N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists. Behav Pharmacol 2:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haretzen CA, Hickey JE (1987) Addiction research center inventory (ARCI): measurement of euphoria and other drug effects. in Methods of assessing the reinforcing properties of abused drugs (Bozarth MA ed), pp 489–524. Springer-Verlag, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SC, Foster KL, McKay PF, Carroll MR, Seyoum R, Woods JE II, Grey C, Jones CM, McCane S, Cummings R, Mason D, Ma C, Cook JM, June HL (2002) The GABAA receptor alpha 1 subtype in the ventral pallidum regulates alcohol-seeking behaviors. J Neurosci 22:3765–3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Chappelle AM, Samson HH (1995) GABAergic transmission in the nucleus accumbens is involved in the termination of ethanol self-administration in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 19: 1486–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Cox AA (1998) The discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol are mediated by NMDA and GABA(A) receptors in specific limbic brain regions. Psychopharmacology 139:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Cox AA, Bratt AM, Camarini R, Iller K, Kelley SP, Mehmert KK, Nannini MA, Olive MF (2001a) The discriminative stimulus properties of self-administered ethanol are mediated by GABA(A) and NMDA receptors in rats. Psychopharmacology 154:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Nannini MA, Olive MF, Kelley SP, Mehmert KK (2001b) Allopregnanolone and pentobarbital infused into the nucleus accumbens substitute for the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25:1441–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffpauir BK, Gleason EL (2002) Activation of mGluR5 modulates GABA(A) receptor function in retinal amacrine cells. J Neurophysiol 88:1766–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, He X, Ma C, Liu R, Yu S, Dayer CA, Wenger GR, McKernan R, Cook JM (2000) Pharmacophore/receptor models for GABA(A)/bzr subtypes (alpha1beta3gamma2, alpha5beta3gamma2, and alpha6beta3gamma2) via a comprehensive ligand-mapping approach. J Med Chem 43:71–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Zhang W, Liu R, McKernan RM, Cook JM (1996) Benzofused benzodiazepines as topological probes for the study of benzodiazepine receptor subtypes. Med Chem Res 6:384–391. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Stephens DN, Duka T (2001) A low dose alcohol drug discrimination in social drinkers: relationship with subjective effects. Psychopharmacology 157:411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Harvey SC, Foster KL, McKay PF, Cummings R, Garcia M, Mason D, Grey C, McCane S, Williams L, Johnson TB, He X, Rock S, Cook JM (2001) GABAA receptors containing alpha 5 subunits in the CA1 and CA3 hippocampal fields regulate ethanol-motivated behaviors: an extended ethanol reward circuitry. J Neurosci 21: 2166–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostowski W, Bienkowski P (1999) Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol: neuropharmacological characterization. Alcohol 17:63–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lameh J, Wang P, Elgart D, Meredith D, Shafer SL, Loew GH (2000) Unraveling the identity of benzodiazepine binding sites in rat hippocampus and olfactory bulb. Eur J Pharmacol 400:167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Quan B, Juzytch W, Fletcher PJ, Joharchi N, Shaham Y (1998) Reinstatement of alcohol-seeking by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress in rats. Psychopharmacology 135:169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay PF, Foster KL, Mason D, Cummings R, Garcia M, Williams L, Grey C, McCane S, He X, Cook JM, June HL (2004) A high affinity ligand for GABAA-receptor containing 5 subunit antagonizes ethanol’s neurobehavioral effects in Long-Evans rats. Psychopharmacology 172:455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan RM, Whiting PJ (1996) Which GABAA-receptor subtypes really occur in the brain? Trends Neurosci 19:139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhatre MC, Garrett KM, Holloway FA (2001) 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ICS 205–930 alters the discriminative effects of ethanol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 68:163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middaugh LD, Kelley BM, Groseclose CH, Cuison ER Jr (2000) Delta-opioid and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist effects on ethanol reward and discrimination in C57BL/6 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 65:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow AL, Paul SM (1988) Benzodiazepine enhancement of gamma-aminobutryic acid-mediated chloride ion flux in rat brain synaptosomes. J Neurochem 50:302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai TP, Ostafin BD (2003) The influence of alcohol on the activation of outcome expectancies: the role of evaluative expectancy activation in drinking behavior. J Stud Alcohol 64:111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park-Chung M, Wu FS, Farb DH (1994) 3a-Hydroxy-5b-pregnan-20-one sulfate: a negative modulator of the NMDA-induced current in cultured neurons. Mol Pharmacol 46:146–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett DB, Lüddens H, Seeburg PH (1989) Type I and type II GABAA-benzodiazepine receptors produced in transfected cells. Science 245:1389–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy RH, Morrow AL, Blinn JR, Paul SM (1990) Synthesis, metabolism, and pharmacological activity of the 3a-hydroxy steroids which potentiate GABAA-receptor-mediated chloride ion uptake in rat cerebral cortical synaptoneurosomes. J Med Chem 33:1572–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger FO, Cunningham CL (1992) Genetic differences in ethanol-induced hyperglycemia and conditioned taste aversion. Life Sci 50: 113–PL118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Heyser CJ, Cole M, Griffin P, Koob GF (2000) Excessive ethanol drinking following a history of dependence: animal model of allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology 22:581–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano C, Sesma MA, McDonald CT, O’Malley K, Van den Pol AN, Olney JW (1995) Distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 immunoreactivity in rat brain. J Comp Neurol 355:455–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Crestani F, Möhler H (2001) GABAA receptor subtypes: dissecting their pharmacological functions. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22:188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger DD (1993) Substitution by NMDA antagonists and other drugs in rats trained to discriminate ethanol. Behav Pharmacol 4:523–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JP, Overstreet DH, Hodge CW (2005) The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP decreases operant ethanol self-administration during maintenance and after repeated alcohol deprivations in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 179:262–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon EE, Porcu P, Purdy RH, Grant KA (2005) Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone in DBA/2J and C57BL/6J inbred mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314:675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AP, Nathan PE, Hay WM, Lipscomb TR (1980) Influence of dosage level on blood alcohol level discrimination by alcoholics. J Consult Clin Psychol 48:655–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL (2004) Substitution profiles of N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists in ethanol-discriminating inbred mice. Alcohol 34:165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Balster RL (1994) Ethanol drug discrimination in rats: substitution with GABA agonists and NMDA antagonists. Behav Pharmacol 5:441–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Grant KA (2002) Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:747–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N (1992) Distribution of the mRNA for a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) in the central nervous system: an in situ hybridization study in adult and developing rat. J Comp Neurol 322:121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooren WP, Gasparini F, Salt TE, Kuhn R (2001) Novel allosteric antagonists shed light on mGlu(5) receptors and CNS disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanski R, Bienkowski P, Kostowski W (1996) Studies on the role of 5-HT3 receptors in the mediation of the ethanol interoceptive cue. Eur J Pharmacol 309:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman I (1992) Drugs of abuse: behavioural principles, methods and terms [see comment]. Trend Pharmacol Sci 13:170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosler PS, Bombace JC, Kosten TA (2001) A discriminative two-lever test of dizocilpine’s ability to reinstate ethanol-seeking behavior. Life Sci 69:591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter JC (1975) The stimulus properties of morphine and ethanol. Psychopharmacologia 44:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]