Abstract

Understanding the intricate cellular interactions involved in bone restoration is crucial for developing effective strategies to promote bone healing and mitigate conditions such as osteoporosis and fractures. Here, we provide compelling evidence supporting the anabolic effects of a pharmacological Pyk2 inhibitor (Pyk2-Inh) in promoting bone restoration. In vitro, Pyk2 signaling inhibition markedly enhances alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, a hallmark of osteoblast differentiation, through activation of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Notably, analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells through RNA-seq revealed a novel candidate, SCARA5, identified through Pyk2-Inh treatment. We demonstrate that Scara5 plays a crucial role in suppressing the differentiation from stromal cells into adipocytes, and accelerates lineage commitment to osteoblasts, establishing Scara5 as a negative regulator of bone formation. Additionally, Pyk2 inhibition significantly impedes osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. In a co-culture system comprising osteoblasts and osteoclasts, Pyk2-Inh effectively suppressed osteoclast differentiation, accompanied by a substantial increase in the transcriptional expression of Tnfrsf11b and Csf1 in osteoblasts, highlighting a dual regulatory role in osteoblast-osteoclast crosstalk. In an ovariectomized mouse model of osteoporosis, oral administration of Pyk2-Inh significantly increased bone mass by simultaneously reducing bone resorption, promoting bone formation and decreasing bone marrow fat. These results suggest Pyk2 as a potential therapeutic target for both adipogenesis and osteogenesis in bone marrow. Our findings underscore the importance of Pyk2 signaling inhibition as a key regulator of bone remodeling, offering promising prospects for the development of novel osteoporosis therapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12964-024-01945-8.

Keywords: Pyk2, Bone, Mesenchymal stem cell, Osteoclast, Osteoblast, Adipocyte

Introduction

Bone remodeling is an essential and continuous physiological process that maintains skeletal integrity by continually renewing bone tissue, responding to mechanical stress, and repairing microdamage throughout life [1]. This process is initiated by osteocytes, which serve as mechanical sensors to detect micro-fracture and signal for repair. Osteocytes coordinate the recruitment of osteoclasts to resorb damaged bone, while simultaneously activating osteoblasts to deposit new bone matrix [2], maintaining a balance crucial for skeletal integrity. Disruption in this balance can lead to the development of bone pathologies, with postmenopausal osteoporosis being the most prevalent and impacting elderly women [3], by increasing fracture risk and mortality rates [4].

Osteoclasts, the specialized cells responsible for bone resorption, are regulated by osteoblasts-secreted factors such as RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand), which stimulate osteoclast differentiation and activity [5]. Osteoblasts also secrete osteoprotegerin (OPG), a decoy receptor that inhibits RANK-RANKL binding, thus hindering osteoclastogenesis [6]. This coordinated activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts ensures the maintenance of bone homeostasis, allowing bone to adapt to mechanical stress, repair microdamage, and respond to hormonal and metabolic signals [7]. Dysregulation in this balance can lead to bone diseases such as osteoporosis (excessive bone resorption), osteopetrosis (impaired bone resorption), or Paget’s disease of bone (abnormal bone remodeling) [8, 9].

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (BMSCs) are multipotent cells that can differentiate into osteoblasts responsible for the bone formation or adipocytes responsible for bone marrow fat formation [10]. The negative correlation between bone mass and marrow adiposity suggests a potential coordination in the lineage progression of BMSCs toward osteoblasts or adipocytes [11, 12], a process influenced by signaling pathways such as the canonical Wnt signaling pathway [13, 14]. Therefore, Wnt signaling emerges as a potential therapeutic strategy for addressing osteoporosis related to marrow adiposity, particularly in postmenopausal women [15] who experience declines in bone mass and increases in marrow fat.

Genetic factors play a substantial role in bone mineral density (BMD), accounting for an estimated 60–90% of its phenotype variance [16][17, 18], with its variants affecting bone metabolism and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and exome-wide analysis have identified the Protein Tyrosine Kinase 2 Beta (PTK2B) gene, encoding protein tyrosine kinase (Pyk2), as a novel locus associated with BMD and bone mineral content (BMC) [17, 18]. Pyk2, a member of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) family, is widely studied in bone biology due to its expression in both osteoblasts and osteoclasts, [19]. Recent findings suggest the genetic deletion of Pyk2 results in increased bone bass, attributed to enhanced osteoblast activity and decreased osteoclast-mediated bone resorption [19, 20]. Specifically, Pyk2-deficient osteoblasts exhibit increased proliferation and mineral deposition, positioning Pyk2 as a potential target in bone-related pathologies [21].

However, due to the high homology (65%) and shared domain structure between Pyk2 and FAK [22, 23], previous efforts to develop selective therapeutic agents for Pyk2 have faced several limitations, including kinase specificity, complexity of the cellular signaling network, off-target effects and potential toxicity etc. These challenges complicate the development of effective Pyk2-targeted therapies, as precise inhibition is required to avoid unintended FAK inhibition, thereby highlighting the need for alternative approaches to selectively modulate Pyk2 function in bone homeostasis. To address these challenges, we employed PF-4618433, a newly developed Pyk2-selective inhibitor, to specifically inhibit Pyk2 while avoiding FAK interference. This targeted approach enabled us to isolate Pyk2-specific effects on bone metabolism, providing a precise framework to understand Pyk2’s distinct contributions to bone homeostasis.

In this study, we observed an anabolic effect on bone mass upon Pyk2 selective inhibitor treatment, indicating enhanced osteogenesis from BMSCs transitioning to osteoblasts, along with reduced osteoclast differentiation. Furthermore, we identified that Pyk2 signaling plays a crucial role in directing lineage commitment towards osteogenesis while also inhibiting adipogenesis through the regulation of Scara5 expression. These findings provide novel insights into the pathophysiological role of Pyk2 in osteogenesis and underscore its potential as a therapeutic target for osteoporosis.

Results

Pyk2-targeted inhibitor enhances osteogenesis in stromal cells

To ascertain the relative significance of Pyk2 versus Fak in the osteogenesis, we compared the effects of the Pyk2-selective inhibitor PF-4618433 (hereafter referred to as Pyk2-Inh) and PF-431396 (hereafter referred to as Pyk2/Fak-Inh), a potent dual inhibitor targeting both Pyk2 and Fak [25], on proliferation in the osteoblastic cell line, MC3T3-E1. As depicted in Sup. Figure 1A, treatment with both Pyk2/Fak-Inh and Pyk2-Inh did not significantly alter cell proliferation compared to the control group. These results indicate that neither inhibitor induced changes in cell proliferation at the indicated concentrations. Additionally, treatment with both inhibitors for 7 days failed to enhance the ALP activity in MC3T3-E1 cells (Sup. Figure 1B). Notably, while Pyk2/Fak-Inh at 100 and 500 nM showed no significant difference compared to the control group, treatment with 1000 nM resulted in strong inhibition, reducing ALP activity to 31.1% (Sup. Figure 1B).

In contrast to our findings, previous studies have suggested that bone marrow-derived stromal cells from Pyk2-deficient mice demonstrated enhanced osteoblast differentiation and activity, implying a negative regulatory role for Pyk2 in osteoblast differentiation [19]. This discrepancy prompted us to hypothesize that the impact of Pyk2 inhibitors on ALP activity might vary depending on the cell lineage. To investigate this further, we explored the effects of Pyk2 inhibition using stromal cell line ST2, known for its potential to differentiate into osteoblasts. Our data revealed that Pyk2 inhibition using both Pyk2/Fak-Inh and Pyk2-Inh did not significantly affect ST2 cell proliferation at low concentrations (100–500 nM). However, at a high concentration of 1000 nM, both inhibitors markedly reduced proliferation rates to 70% and 64.2%, respectively (Sup. Figure 1C). Pyk2/Fak-Inh exhibited a clear dose-dependent reduction in ALP activity in ST2 cells, decreasing to 19.4% at a concentration of 1000 nM compared to the control group (Sup. Figure 1D). Interestingly, treatment with Pyk2-Inh stimulated a dose-dependent increase in ALP activity, with the highest concentration (1000 nM) administered for 4 days resulting in approximately a twofold enhancement compared to the control group (Sup. Figure 1D). These findings suggest that Pyk2-Inh specifically promotes cell lineage-related differentiation, especially in stromal cells, whereas Pyk2/Fak-Inh did not promote the osteogenic differentiation in ST2 cells.

Inhibition of Pyk2 signaling enhances Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity

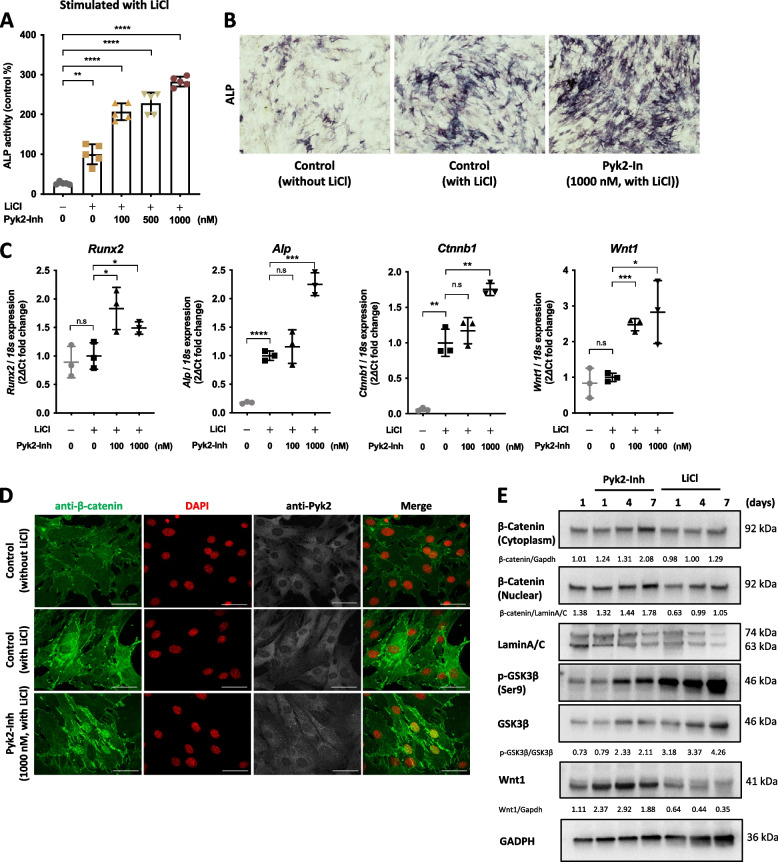

To elucidate the influence of Pyk2 on osteoblast function, particularly in terms of osteoblast differentiation in ST2 cells, we employed 5 mM LiCl to induce osteogenesis, as previously described [26]. We evaluated the effects Pyk2-Inh on ST2 cell’s osteoblast differentiation by measuring ALP activity. As shown in Fig. 1A, LiCl treatment robustly induced ALP activity, while Pyk2-Inh treatment further enhanced both ALP activity and the number of ALP-positive cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Notably, this induction of ALP activity was observed not only in osteogenic medium containing ascorbic acid (AA) and β-glycerophosphate (β-GP) but also in growth medium without any stimulants (Sup. Figure 2A). Moreover, Pyk2-Inh treatment resulted in a substantial upregulation of key osteogenic markers, including Runx2, Alp, Ctnnb1, compared to the control group (Fig. 1C). Morphological observations revealed that naïve osteoblasts exhibited an elongated spindle shape, while upon Pyk2-Inh treatment for 4 days, the cells changed to more cuboidal, transitioning via round to stellate shapes (Sup. Figure 2B). We also confirmed the specificity of Pyk2-Inh against Pyk2 signaling via immunoblot analysis (Sup. Figure 2C). To further validate the signal of Pyk2, cells were treated with Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)-peptide, which has a high affinity to integrin and is known to activate Pyk2 phosphorylation [27]. The stimulation with RGD-peptide led to increased phosphorylation of Pyk2, and this signal was markedly downregulated by Pyk2-Inh treatment (Sup. Figure 2C).

Fig. 1.

Pyk2 inhibition enhanced osteoblast differentiation by enhancing Wnt signaling. A ST2 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 10.4 cells per well in a 96-well plate. Cells were then differentiated into osteoblasts under the various stimulants, including simple growth medium, osteogenic medium containing ascorbic acid (AA, 100 μg/mL) and β-glycerophosphate (β-GP, 5 mM), and lithium chloride (LiCl, 5 mM). After 4 days of Pyk2-Inh treatment, ALP activity was measured by ALP assay kit. B Cells were fixed with 10% formalin and stained with ALP staining. C The transcriptional expression of Runx2, Alp, Ctnnb1 and Wnt1 were measured by RT-qPCR. D Immunocytochemical staining for anti-β-catenin (green) and anti-Pyk2 (white) in ST2 cells. The cells were treated with Pyk2-Inh for 4 days. DNA nuclei stained with DAPI (red). E The protein levels of β-catenin, GSK-3β and Wnt1 were assessed by immunoblotting analysis in ST2 cells. Cell lysis was divided into cytosol and nuclear fractions, and each fraction was normalized by Gapdh and LaminA/C, respectively. Quantification of immunoblotting data measured by ImageJ. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of three cultures. #: Significance between Sham and OVX-Vehicle, *: Significance between OVX-Vehicle vs OVX-Pyk2-Inn or OVX-LiCl treatment groups, *:P < 0.05

To explore the potential involvement of Pyk2 signaling in Wnt/β-catenin-induced osteoblastic differentiation, we conducted immunocytochemical staining to confirm the localization of β-catenin, indicating its translocation from cytosol to the nucleus (Fig. 2D). Wnt canonical signaling stimulation can protect β-catenin from phosphorylation by the GSK-3β, APC and Axin complex, thereby stabilizing β-catenin in the cytoplasm and facilitating its translocation into the nucleus [28]. As depicted in Fig. 2D, Pyk2-Inh treatment promoted the translocation of β-catenin from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, as indicated by the yellow coloration in the merged images.

Fig. 2.

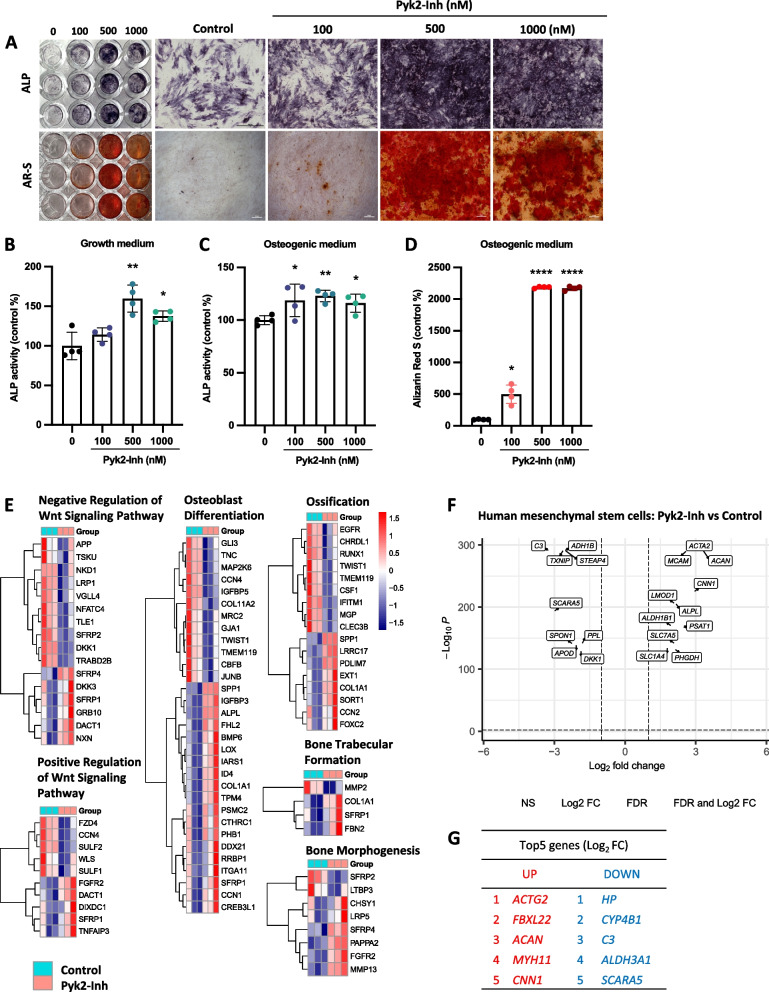

Pyk2 inhibition promoted osteogenesis from human mesenchymal stromal cells into osteoblasts. hMSCs were cultured with osteogenic medium with or without Pyk2-Inh for 7–14 days. A ALP and Alizarin Red staining (AR-S) was performed (scale bars, 500 μm and 50 μm, respectively, n = 5). B, C Cell lysates were analyzed for ALP activity on days 7 under growth medium (B) and osteogenic medium (C). D Cells were assessed for mineralized area by quantitative of alizarin red labeled nodule on day 14. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of three cultures. *:P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001. E–G) hMSCs were cultured in osteogenic medium with Pyk2-Inh treatment for 4 days. RNA was purified and subjected for RNA sequencing analysis. E Pathway analysis and differential expression levels of each gene involved in biological process were conducted. F Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between control and Pyk2-Inh treated group. G Top 5 differentially expressed genes that are both down- and up-regulated between the control group and Pyk2-Inh treated group

To corroborate these findings, we performed an immunoblotting assay to confirm the protein level of β-catenin and GSK-3β (Fig. 2E). ST2 cells were cultured under normal growth medium in the presence or absence of 1000 nM Pyk2-Inh for the indicated duration, and cell lysates at each time point were harvested and the cytoplasmic and the nuclear fraction isolated. The results revealed that an increase in total β-catenin levels in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, indicating that Pyk2 inhibition stabilizes β-catenin. Additionally, the level of phosphorylated GSK-3β was enhanced over time with Pyk2-Inh treatment, suggesting that enhanced β-catenin levels accompanied by increased GSK-3β phosphorylation, similar to the effects observed with LiCl treatment. Notably, treatment with Pyk2-Inh significantly elevated Wnt1 expression at both the transcriptional level and protein level (Fig. 1C, E and E).

Inhibition of Pyk2 signaling stimulates osteogenesis in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs)

To investigate the role of Pyk2 signaling on osteoblastogenesis and the transcriptomic profile, we examined the effects of Pyk2-Inh on ALP activity and osteogenic marker genes in hMSCs. After reaching confluence in 24-well plates, hMSCs were cultured for 4 days in both osteogenic medium and normal growth medium. ALP activity was analyzed through histochemical staining and enzyme activity assays (Fig. 2A upper panels, 2B and 2C), while mineral deposition was assessed using alizarin red staining (Fig. 2A lower panels and 2D). Results demonstrated a significant increase in ALP activity and calcification in the Pyk2-Inh treated hMSCs compared to control group, corroborating observations from similar assays performed in ST2 cells.

To investigate transcriptional changes associated with Pyk2 inhibition, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on Pyk2-Inh-treated hMSCs and control groups, mapping gene expression changes across the entire transcriptome. Differentially expressed genes were categorized by Gene Ontology (GO) classification into biological process, cellular components, and molecular function, as illustrated in Sup. Figure 3A. Functional pathway analysis employing the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and Disease pathways databases highlighted distinct signaling pathways modulated by Pyk2 inhibition (Sup. Figure 3B and 3C). Additionally, a focused analysis of the biological process category generated a heatmap that highlights gene clusters associated with osteogenesis and related pathways, as displayed in Fig. 2E. To visualize the transcriptomic differences, a heatmap was generated, highlighting logs (fold-change) > ± 1 and listing the top five up-and down-regulated genes in the Pyk2-Inh treated group (Fig. 2F and G).

Given the established role of Wnt signaling in osteoblast differentiation, we specifically examined Wnt-related genes identified in the RNA-seq counts. Key Wnt pathway components, DKK1, ROR2, LRP4 and SFRP2, were significantly altered in Pyk2-Inh treated hMSCs, and these findings were validated by qPCR (Sup. Figure 3D). Using the open-source platform Cytoscape (cytoscape.org), we analyzed and visualized the Wnt signaling interaction network modulated by Pyk2 inhibition, highlighting pathway elements influenced by Pyk2-Inh treatment (Sup. Figure 3E). These findings indicate that inhibition of Pyk2 signaling enhances osteoblast differentiation in hMSCs, accompanied by modulation of Wnt-related gene expression, suggesting a critical role of Pyk2 in osteogenesis regulation.

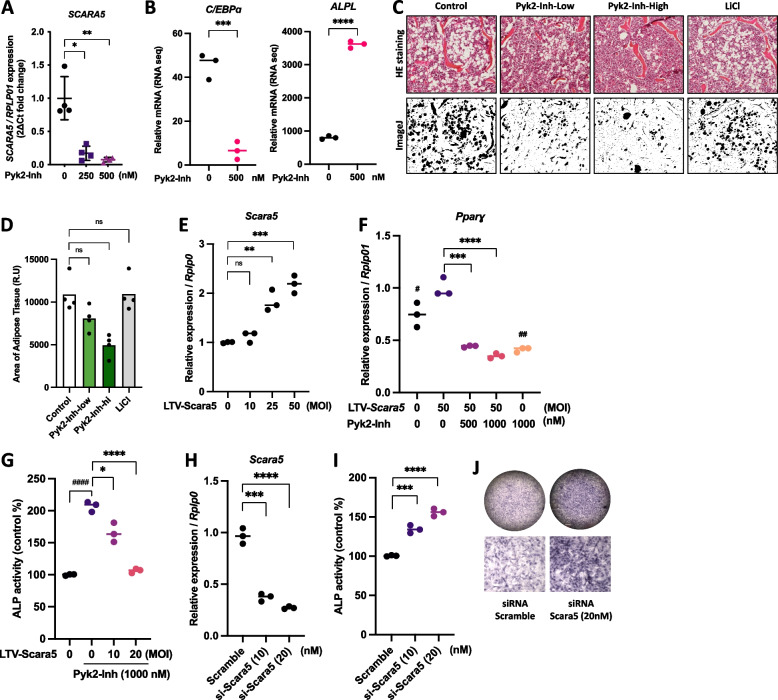

Inhibition of Pyk2 reduces Scara5 expression, suppressing adipocyte differentiation and enhancing osteoblast formation in MSCs

Through our analysis of the top five down-regulated genes, SCARA5, a novel candidate gene, encoding a scavenger receptor, emerged as a key factor regulated by Pyk2 inhibition. SCARA5, prominently expressed in white adipose tissue, is recognized as a novel mediator of adipocyte commitment [29]. qPCR validation showed that SCARA5 transcriptional expression in hMSCs was markedly reduced following Pyk2-Inh treatment (Fig. 3A), suggesting a potential regulatory role in mesenchymal lineage differentiation. Moreover, Pyk2-Inh treatment significantly reduced the expression of C/EBPα, a marker of adipocyte differentiation, while notably increasing ALPL expression, a marker of osteoblast differentiation, as confirmed by RNA-seq data (Fig. 4B). To assess the effects of Pyk2 inhibition on marrow adiposity, we performed HE staining on bone marrow sections and quantified adipose tissue distribution using ImageJ (Fig. 3C and D). Results indicated a significant reduction in marrow fat distribution in the high-dose Pyk2-Inh group compared to the OVX-Con. Interestingly, while the OVX-LiCl group displayed an anabolic effect on bone formation, it did not impact the inhibition of marrow fat distribution.

Fig. 3.

Suppression of Scara5 by Pyk2 inhibitor, induced osteogenesis but inhibited adipogenesis. A The transcriptional expression of SCARA5 in hMSCs. B The transcription expression of C/EBPα and ALPL from RNA seq. C Histochemical images of adipose tissue from HE staining (upper panels) and representative analysis images of adipose tissue (lower panels) in ImageJ. D Quantitative data of adipose tissue area. E ST2 cells were transfected with Lentivirus vector (LTV)-Scara5 and cultured in an adipogenic medium for 48 h. The transcriptional expression of Scara5 was assessed using RT-qPCR. F Pparɣ expression was evaluated by RT-qPCR. G In separation experiments, ST2 cells were transfected with Lentivirus vector (LTV)-Scara5 and cultured in osteogenic medium supplemented with AA and β-GP for 48 h. ALP activity was then assessed using ALP assay kit. H ST2 cells were transfected with either siRNA-scramble or siRNA-Scara5 for 48 h, followed by RT-qPCR analysis to evaluate the transcriptional expression of Scara5. I, J Subsequently, cells were maintained for an additional 7 days and ALP activity was then measured using an ALP assay kit and ALP staining kit. *:P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001

Fig. 4.

Pyk2 inhibition decreased BMMs-derived osteoclast differentiation and function. A The timeline for osteoclast differentiation and treatment of Pyk2-Inh. Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) were differentiated into mature osteoclasts (mOC) with 100 ng/mL RANKL and 50 ng/mL M-CSF for 6 days. B Cell proliferation was assessed by CCK-8 during pOC to mOC stage. C TRAP activity was measured using a TRAP assay kit. D Cells were fixed with 10% formalin and stained with TRAP. E The transcriptional expression of Nfatc1 and Ctsk were measured by RT-qPCR. F Co-culture experiment for bone resorption function of mature osteoclasts. G Actin ring of mature osteoclasts on dentin slices were visualized by staining F-actin with phalloidin-AlexaFluor568 (scale bars, 20 μm, n = 3). H Actin ring size was measured by ImageJ (n = 5). I Co-culture experiment for osteoclast differentiation. Primary calvariae osteoblasts and BMCs were co-cultured in 24-well plates for 5 days in the presence of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (10–8 M). J, K Fixed cells were stained with TRAP. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells containing five or more nuclei were counted as mature osteoclasts. L) The transcriptional expression of Rankl, Tnfrsf11b and Csf1 were measured by RT-qPCR. Results are expressed as the means ± SD of three cultures. *:P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001

To further investigate the functional role of Scara5 in MSC differentiation, we employed a lentivirus vector (LTV) overexpression system to modulate Scara5 levels in ST2 stromal cells, promoting their commitment to either adipocyte or osteoblast lineages. LTV-Scara5 vectors were transfected into ST2 cultures in adipogenesis medium at the indicated MOI (Fig. 3E), resulting in successful induction of Scara5 expression within 48 h. Under these conditions, differentiation toward adipocytes was initiated, and after for 72 h, the adipogenic marker Pparɣ expression was significantly induced with LTV-Scara5. However, this induction was notably suppressed by Pyk2-Inh treatment (Fig. 3F). For investigating Scara5’s role in osteoblast differentiation, we transfected ST2 cells with either LTV-Scara5 or siRNA-Scara5 and maintained them in osteogenic medium containing AA and β-GP (Fig. 3G and I). Scara5 overexpression attenuated the Pyk2-Inh-induced increase in ALP activity (Fig. 3G). Conversely, Scara5 knockdown with siRNA significantly enhanced ALP activity and increased the number of ALP positive stained osteoblasts compared to the control (scramble) (Fig. 3I and J). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that inhibition of Pyk2-Inh downregulates Scara5, suppressing adipocyte differentiation while simultaneously promoting osteogenic differentiation, underscoring Pyk2's crucial role in MSC lineage commitment.

Inhibition of Pyk2 signaling decreases osteoclast differentiation and function

Upon stimulation by RANKL, precursor osteoclasts (pOC) undergo several development steps, including differentiation, fusion, and activation, leading to mature osteoclasts (mOCs) (Fig. 4A). Treatment with Pyk2-Inh significantly increased cell proliferation without any exhibiting inhibitory effect (Fig. 4B), while it consistently reduced tartrate-resistant acid phosphate (TRAP) activity in a dose-dependent manner, demonstrating its impact on osteoclast functionality (Fig. 4C). Notably, complete inhibition of osteoclast formation was observed at a high dose of 1000 nM treatment, as stained by TRAP kit (Fig. 4D). Pyk2-Inh treatment significantly reduced the transcriptional levels of Nfatc1 and Ctsk, which are key indicators of osteoclast differentiation during the early maturation stage from bone marrow macrophages (BMM) to pOC (Fig. 4E). To further assess the resorptive capabilities of mature osteoclasts, we generated these cells via co-culture and subsequently cultured on dentin slices (Fig. 4F). Pyk2-Inh treatment led to a significant reduction in both the formation and size of actin rings, as visualized by phalloidin staining, indicating impaired bone resorption function (Fig. 4G and H).

Furthermore, to elucidate the indirect effects of Pyk2-Inh on osteoclastogenesis, we conducted co-culture experiments with BMCs and calvariae osteoblasts in the presence of 1α, 25-(OH)2D3 (Fig. 54I). While 1α, 25-(OH)2D3 induced numerous TRAP-positive osteoclasts within 5 days, Pyk2-Inh significantly decreased their numbers in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4J and 4K). Interestingly, we observed dramatic increases in Tnfrsf11b (Opg), and Csf1 (an essential growth factor for osteoclast progenitors) following Pyk2-Inh treatment, but not Rankl expression (Fig. 4L). Overall, our findings suggest that Pyk2-Inh directly inhibits osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption function. Additionally, in co-culture experiments, Pyk2-Inh showed the potential to indirectly suppress osteoclast proliferation and differentiation by modulating the expression of Opg and Csf1 from osteoblasts.

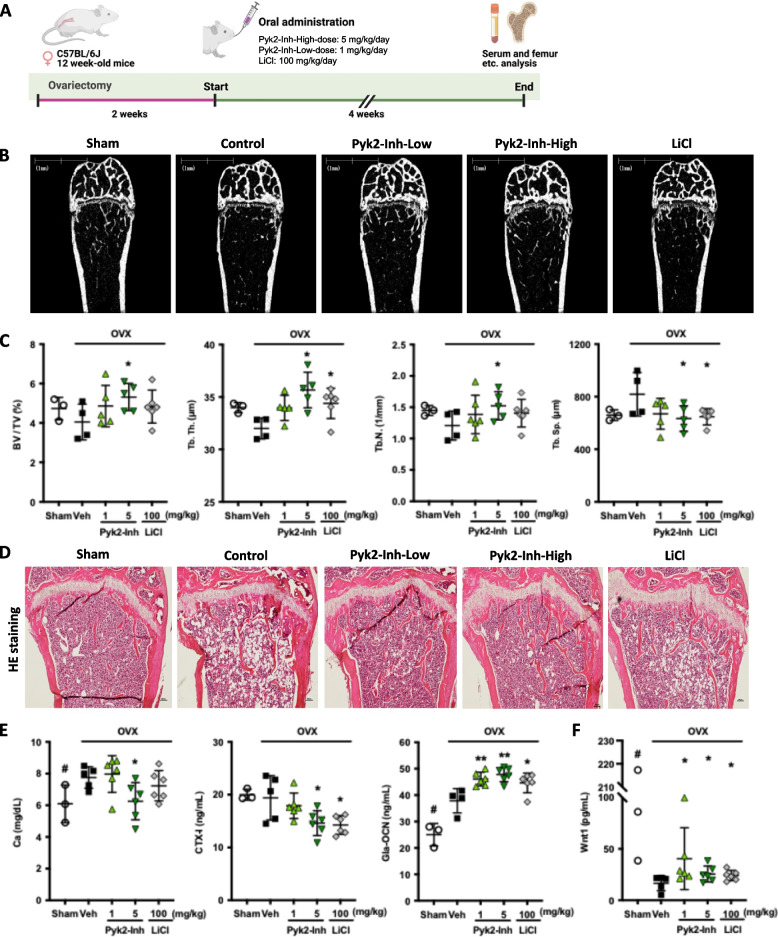

Pyk2-targeted inhibitor increases bone mass in ovariectomized (OVX) mice

To validate the biological efficacy of Pyk2 inhibition on bone remodeling in vivo, we investigated the impact of Pyk2-Inh in an OVX mouse model (Fig. 5A). OVX-induced bone loss was simulated, followed by Pyk2-Inh administration at low (1 mg/kg/day) and high (5 mg/kg/day) doses, which correspond to effective concentrations of 500 nM and 1000 nM, in ST2 cells, respectively, for mice weighing approximately 20 g. Both low and high doses of Pyk2-Inh, as well as lithium chloride (LiCl), were delivered via oral gavage for four weeks following a two-week recovery period post-ovariectomy.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of Pyk2 signaling increased bone mass in ovariectomized mice. A The experimental schedule of ovariectomy and Pyk2-Inh administration. B, C μCT images of distal femur and quantitative analysis of μCT. Data shows the bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), number of trabecular bone (Tb.N), separation (Tb.Sp), and thickness (Tb.Th). D HE staining of isolated femurs from control and Pyk2-Inh treated group. E Changes of serum levels of Ca, CTX-I, and Gla-osteocalcin (OCN) in OVX-mice treated with vehicle and Pyk2-Inh. F Levels of Wnt1 in mouse serum were measured using an ELISA kit. Results are expressed as the means ± SD. Asterisks indicate the significance in the subgroups (treated vs. control): *:P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001, #: significance between Sham and OVX-vehicle

Trabecular bone compartments within the distal metaphysis of the femoral bone were evaluated using micro-CT (Fig. 5B) and HE stain (Fig. 5D). While OVX mice exhibited reductions in BV/TV, Tb. Th, Tb. N, and an increase in Tb. Sp, these alterations were not statistically significant when compared to the Sham-Veh group (Fig. 5C). However, the high dose of Pyk2-Inh treatment significantly enhanced BV/TV, Tb. N while reducing Tb. Sp, indicating a favorable effect on bone mass preservation. These findings were further corroborated by a significant decrease in serum level of Ca and CTX-I, a bone resorption marker, with the high dose of Pyk2-Inh (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, the Gla-type of osteocalcin (OCN), indicative of bone formation, was substantially elevated with the high dose of Pyk2-Inh, with a similar trend observed at the low dose. We also demonstrated that the suppressed Wnt1 level was significantly elevated in serum analyses (Fig. 5F), consistent with the results shown in Fig. 1C and 1E. Consequently, the administration of high dose Pyk2-Inh not only attenuates bone resorption but also promotes bone formation, highlighting its potential as an effective therapeutic strategy for enhancing bone health. To assess the comparative efficacy of Pyk2-Inh, LiCl (100 mg/kg/day) was employed as a positive control [24]. Parameters such as Tb. Th. and Tb. Sp. in micro-CT, as well as serum analyses, were observed in the OVX-LiCl group compared to the OVX-control group, thereby validating its role as a positive reference in this study.

Discussion

Bisphosphonates (BPs) are classic antiresorptive agents routinely prescribed to prevent bone loss, particularly in post-menopausal women. However, their inability to induce new bone formation renders them insufficient for individuals suffering from severe osteoporosis. Furthermore, certain BPs have serious side effects such as atypical femoral fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw [30, 31]. In contrast, the new class of anabolic treatment, parathyroid hormone (PTH, Teriparatide), is capable of inducing bone formation. However, its use is limited to two years due to concerns about inducing osteosarcoma, as observed in rat models of carcinogenicity [32, 33]. Therefore, there is a growing need for new potent anabolic agents that can effectively stimulate new bone formation and inhibit bone resorption, ultimately leading to an improved balance of bone remodeling.

Previous studies have reported that specific Pyk2-selective inhibitor, PF-46181433 enhances ALP activity of hMSC in vitro [34]. However, there has been limited progress in understanding how Pyk2 contributes to the pathophysiology of osteoporosis and the molecular mechanism involved in osteoblast differentiation. Our observations reveal that PF-4618433 significantly increased ALP activity in stromal cells, rather than fully differentiated osteoblasts, which aligns with previous findings demonstrating its mineralization-enhancing effects in mesenchymal cell populations [21]. This differential effect underscores the complexity of Pyk2 inhibition across various cell types in the bone microenvironment. Given high homology between Pyk2 and FAK, we compared PF-431396, a Pyk2/FAK dual inhibitor, to assess its potency in increasing ALP activity. PF-431396 showed potential in vivo, as it increased BMD and prevented bone loss in OVX rats, suggesting its candidacy for promoting bone formation [19]. Interestingly, our results demonstrated that Pyk2/Fak-Inh (PF-431396) significantly reduced ALP activity in both osteoblasts and stromal cells (Sup. Figure 1B and 1D), suggesting that the dual inhibition did not promote osteogenesis as anticipated. This finding is consistent with previous studies on FAK conditional knockout (cKO) mice, which indicated decreased cell proliferation, ALP activity, and diminished the mRNA levels of key osteogenic transcription factors such as Runx2 and Osterix, resulting in decreased bone mass [35]. These findings suggest that FAK positively regulates osteoblastogenesis, contrasting with the role of Pyk2. Notably, recent research has shown that the loss of FAK in osteoblasts can be compensated by the upregulation of Pyk2 activation [36]. One potential explanation for our observations is that PF-431396 has a stronger inhibitory potency on FAK compared to Pyk2 [25]. Inhibited FAK directly reduces osteoblast differentiation activity, while indirectly increasing Pyk2 function, limiting the efficacy of single-target inhibition. This compensatory increase in Pyk2 function may outweigh the inhibition of Pyk2 itself. These results suggest that the PF-4618433 has the ability to induce differentiation by stimulating stromal cells into osteoblasts, particularly in the early stages of bone formation. Notably, FAK inhibition significantly impacts the proliferation of early osteoblast lineage cells rather than mature osteoblasts [36]. This aligns with our results showing that PF-431396 did not significantly affect the proliferation in MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts, but did affect ST2 cell proliferation, particularly at higher concentrations.

Adipose tissue formation in the bone marrow is a natural physiological process that occurs throughout life, involving the differentiation of BMSCs into adipocytes [37]. This process is tightly regulated and plays important roles in bone metabolism and hematopoiesis [4]. However, dysregulation of this balance, characterized by excessive adipogenesis and reduced osteogenesis, can severely compromise skeletal health. In postmenopausal women, there is a significant increase in adipose tissue formation in the bone marrow [38], primarily attributed to hormonal fluctuations, particularly the decline in estrogen levels [39]. Estrogen plays a crucial role in maintaining bone homeostasis by suppressing adipogenesis and osteoclastogenesis while promoting osteoblastogenesis [40]. Following menopause and the concomitant decline in estrogen levels, there is an unfavorable shift in the balance between adipogenesis and osteogenesis, favoring adipose tissue formation over bone formation [39]. Early lineage mesenchymal cells have the ability to differentiate into various cell types, including osteoblasts and adipocytes [41]. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling is involved in this cell fate decision [42]. LiCl, a recognized activator of the Wnt signaling pathway, has been shown to enhance bone growth and osteoblast differentiation by stimulating the canonical Wnt cascade, which inhibits glycogen synthetase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), leading to the stabilization of cytosolic β-catenin [43]. Building on our previous findings and established research, we selected 5 mM LiCl to induce osteoblastogenesis in ST2 cells [43, 44]. To investigate the potential involvement of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in Pyk2-Inh-mediated on osteogenesis, we analyzed gene expression profiles from GO analysis in hMSCs. Notably, Pyk2 inhibition was found to negatively regulate the Wnt signaling pathway, consistent with in vitro results in ST2 cells. Overexpression of Wnt1 or Wnt10b, known activators of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, potently represses adipogenesis [45, 46]. In our study, the increased Wnt1 observed in the serum analysis, as well as protein expression and transcriptional expression in ST2 cells, supports the notion that Pyk2 inhibition enhances Wnt signaling, providing compelling evidence for its vital role in regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts, aligning with broader research demonstrating Pyk2's involvement in Wnt pathways across various cellular contexts [47–49].

We identified differentially expressed genes between the naïve control and Pyk2-Inh treatment group in hMSCs. A significantly decreased expression of SCARA5 was notable during the early stages of lineage commitment from MSCs to osteoblasts. SCARA5 has been identified as a potential critical regulator in adipocyte commitment [29]. In our functional study, we confirmed the inhibition of adipocyte differentiation through Scara5 knockdown using siRNA in ST2, which corresponds with the results obtained from Pyk2-Inh treatment. Moreover, we observed that the elevated expression of Pparɣ induced by LTV-Scara5 was significantly reduced by Pyk2-Inh treatment. Conversely, while Pyk2-Inh led to increased ALP activity and transcriptional expression, this effect was countered by LTV-Scara5, resulting in decreased ALP activity. Additionally, even with reduced expression via siRNA-Scara5, ALP activity was higher in ST2 cells compared to the control. These findings support that the modulation of Scara5 by Pyk2 inhibition is primarily associated with lineage commitment between osteoblasts and adipocytes, making it a potential therapeutic target for regulating marrow fat and bone formation.

Pyk2 also plays a crucial role in osteoclast differentiation, a process crucial for bone remodeling. Osteoclasts, specialized cells responsible for bone resorption, undergo tightly differentiation regulated by various signaling pathways, including Pyk2-mediated pathways. Studies have shown that Pyk2 is expressed in osteoclast precursor cells and becomes activated during osteoclast differentiation [20, 50]. RANKL, a key cytokine in osteoclast activation, triggers Pyk2 activation, which subsequently regulates multiple downstream signaling pathways essential for osteoclast differentiation. It phosphorylates and activates various signaling molecules, including Src family kinases, leading to the activation of downstream signaling cascades such as the MAPK and NF-kB pathways. These pathways ultimately regulate the expression of genes involved in osteoclast differentiation, fusion and activation. Furthermore, Pyk2 has been implicated in the cytoskeletal reorganization necessary for osteoclast function and bone resorption [51, 52]. It regulates the assembly and organization of the actin cytoskeleton, which is crucial for the formation of the sealing zone, a specialized structure required for efficient bone resorption by osteoclasts. Our results demonstrate that Pyk2 inhibition directly suppressed osteoclast differentiation markers, including Nfatc1 and Ctsk, consequently inhibiting osteoclast differentiation. Additionally, we observed the inhibitory effect of Pyk2-Inh on the defection of actin ring formation, leading to impaired bone resorption. Furthermore, in co-culture of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, Pyk2-Inh treatment induced the expression of Opg and Csf1 in osteoblasts, providing further evidence of its indirect inhibitory effects on osteoclast differentiation. Taken together, these findings highlight the multifaced effects of Pyk2 inhibition on bone cells regulation.

In summary, Pyk2-target inhibitor demonstrate three key functions: promoting osteogenesis through the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, suppressing adipogenesis by targeting Scara5, and inhibiting osteoclast formation (Sup. Figure 4A). These multifaced actions highlight their potential as groundbreaking candidates for the development of multitarget drugs to combat osteoporosis. Historically, Pyk2 has been studied primarily for its roles in neuronal function and anti-tumor activity mainly through modulation of FAK, Src kinase, and the PI3K/Akt pathway. However, emerging evidence suggests that Pyk2 inhibitor may offer additional benefits, particularly in enhancing bone health. This versatility opens intriguing possibilities for treating not only bone-related diseases but also other diseases simultaneously.

Preliminary data suggest that Pyk2 inhibitors may also exhibit a favorable safety profile; however, more extensive clinical trials are needed to thoroughly evaluate their long-tern efficacy and potential adverse effects. A crucial consideration is the risk of off-target effects due to the structural similarity between Pyk2 and FAK, which could inadvertently influence overlapping cell signaling pathways. Future research should prioritize optimizing the specificity of Pyk2 inhibitors to minimize unintended impacts on essential cellular functions. In conclusion, while Pyk2 inhibitors represents a novel and promising approach for treating osteoporosis by promoting bone formation, further research is essential to fully understand their therapeutic potential, safety and long-term implications.

Materials and methods

Materials

PF-431396 and PF-4618433 were purchased from (TOCRIS, a bio-techne brand, USA) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma, USA). Subsequently, these were diluted to the appropriate concentrations. The C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX-I) ELISA kit was procured from IDS (UK). The Gla-Osteocalcin ELISA kit was obtained from Takara Bio (Japan). The Calcium-E test kit was purchased from Wako (Japan). A Wnt1 ELISA kit was purchased from MyBiosource (USA) to determine the level of Wnt1 in mouse serum.

Animal models

All animals were approved by the Institutional animal care and use committee of Hokkaido University (approval number: 21–0018) and were performed in accordance with the committee’s guiding principle. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering used for this study. This study reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. 8-week-old female C57BL/6 J mice were obtained from CLEA Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). Experimental mice were housed under controlled lighting conditions (daily light, 07:00–21:00) and were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. 12-week-old mice (body weight 18–22 g) were randomly divided into five groups as follows: sham group (ovary intact + vehicle (normal saline), OVX group (OVX + vehicle), OVX + Pyk2-Inh-low (OVX + 1 mg/kg/day, low-dose), OVX + Pyk2-Inh-high (OVX + 5 mg/kg/day, high-dose), and OVX + LiCl (OVX + 100 mg/kg/day). For the ovariectomy, the mice were initially anesthetized with ketamine administered via intraperitoneal injection, followed by the induction of anesthesia with isoflurane inhalation. During the surgical procedure, anesthesia was maintained with the continuous administration of isoflurane. After anesthetization, the bilateral ovaries were exposed and removed from OVX animals; in the sham group animals, the ovaries were exposed but left intact. Pyk2-Inh and LiCl were orally administered using oral gavage needle for four consecutive weeks, starting 2 weeks after the OVX surgery to ensure the mice had recovered normal activity. The dissected femurs were fixed in paraformaldehyde for 3 days and stored in 70% ethanol until further micro-CT and histological analysis. Two-dimensional micro-CT assessments were conducted by Kureha Special Laboratory Co., Ltd. (Fukushima, Japan). The other side of femur was embedded in paraffin, then sectioned (5 μm), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE).

Osteoblast cell cultures

The osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 cell and mouse bone marrow-derived stromal cell line ST2 cells were cultured in Alpha-Minimum Essential Medium (ɑ-MEM, Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Life Technologies) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Human mesenchymal cells were purchased from Lonza. Human osteoblastic cells were induced in osteogenic basal medium (Lonza) supplemented with ascorbic acid (AA), β-glycerophosphate (β-GP), and dexamethasone. The medium was changed every 3 days until harvested.

Osteoblast differentiation and mineralization

2 × 104 cells / well of MC3T3-E1 and ST2 were separately seeded in 48-well plates and cultured in basal growth medium until confluency. The medium was replaced with an osteogenic medium containing in the absence or presence of Pyk2 inhibitors. For MC3T3-E1, cells were cultured with osteogenic medium containing 100 μg/mL AA and 5 mM β-GP, whereas ST2 cells were induced with 5 mM of LiCl (Sigma). The culture medium was changed every 2–3 days until analysis. After treatment, the cells were fixed with 10% formalin for 10 min and rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). ALP activity was then measured using a LabAssay™ALP kit (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The absorbance was measured by a microplate reader at 405 nm. The ALP activity was standardized to the relative control as a percentage. After determination of ALP activity, the cells were stained using an ALP staining kit (Wako). To assess the mineralization, 2 × 104 cells/well of cells were plated at in the presence or absence of various concentrations of Pyk2 inhibitors and differentiated into mature osteoblasts under osteogenic conditions containing for up to 14 days. Osteoblasts were washed once with PBS and fixed with 10% formalin for 10 min. Cells were washed with tap water and Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining was performed with ARD-SET (PG Research, Japan), followed by the manufacturer’s instruction. Then, the wells were washed with tap water extensively after staining. The bound ARS was extracted with deposition dissolving solution for 10 min and the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader under absorbance of 410 nm. Experiments were performed in triplicate and reproduced 3 times.

Osteoclast differentiation and function

Calvariae osteoblasts were isolated from newborn mice and cultured in α-MEM (Gibco) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were cultured with 10–8 M Vitamin D3 (VitD3) and 10–6 M Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Bone marrow cells (BMCs) were isolated from tibia of 8 to 10-week-old male mice. BMCs were cultured with α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution supplemented with M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 15–18 h. Non-adherent cells were harvested as bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) and differentiated to osteoclast with RANKL (50 ng/mL) for additional 5–6 days. The culture medium was replaced every 3 days. In co-culture, BMCs were isolated from 8 to 10-week-old mice and mixed with isolated calvaria osteoblasts. For osteoclast differentiation, cells were cultured with VitD3 (10–8 M) and PGE2 (10–6 M) for 6 days. To obtain mature osteoclasts from co-culture system, BMCs and calvaria osteoblasts were co-cultured on the Collagen matrix coated dish with VitD3 (10–8 M) and PGE2 (10–6 M). After 6 days, isolated osteoclast precursors were seeded on the dentin slices and further differentiated into mature osteoclasts for 2 days. Dentin slices were fixed with 10% formalin for 10 min, and then stained with Phalloidin (for actin ring formation) or hematoxylin (for pit formation assay).

Cell proliferation assay

To examine the effect of PF-431396 (Pyk2/Fak-Inh) and PF-4618433 (Pyk2-Inh) on proliferation, 1 × 104 cells / well were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured until confluency. Then the cells were cultured with various concentrations of Pyk2 inhibitor for 2 days. Osteoblast proliferation was determined by a 3-(4,5-dime-thylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay with Cell Count Kit (Dojindo, Japan) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance at 570 nm was then measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Japan). The cell viability was standardized to the relative control as a percentage.

Adipocyte differentiation

ST2 cells were seeded on plates and allowed to grow for 2 days until reaching confluence. Cell differentiation was induced by culturing the cells in adipogenesis medium (BMK, Japan). The medium was replaced every 3–4 days. Lipid droplets were confirmed as indicative of adipogenesis.

Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNAeasy® Mini kit (Qiagen, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was quantified using a spectrophotometry (DeNovix, DS-11, Japan). The template RNA was used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) via Reverse Transcription Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions on ice (QuantiTect®, Qiagen, Japan). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was carried out with DNA probes PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, Science, USA). The following primer sequences (Eurofins Genomics, Japan) were listed in Sup. Table 1. To normalize the amount of RNA, the expression of Rplp0 and Gapdh was chosen as the endogenous control. Expression of target mRNA was calculated from delta Ct values.

Immunoblotting analysis

Cells were washed with PBS and cell lysates were harvested by RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor (Abcam, Japan). Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared using ProteoJET™Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Protein Extraction Kit (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, respectively. The protein concentrations were measured using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cytoplasmic protein (20 μg/lane) and nuclear protein (10 μg/lane) were separated on Mini-PROTEAN TGX Gels (Bio-Rad) electrophoresis. The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-Buffered Saline with Tween 20 (TBST) (pH 7.6) (Takara Bio, Japan), followed by incubation with first antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The first antibodies detected in immunoblotting were listed as follows: β-catenin (Anti-mouse, BD Transduction Laboratories™), GSK-3β (Anti-Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, Japan), p-GSK-3β (Anti-Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, Japan), GAPDH (Anti-mouse, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Japan), Lamin A/C (Anti-mouse, Cell Signaling Technology, Japan), Wnt1 (Anti-rabbit, GeneTex), p-Pyk2 (Anti-rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology) and Pyk2 (Anti-rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology). The membranes were washed 3 times with 1 × TBST for 10 min, then added the secondary antibodies (Anti-Rabbit, EnVision + System- HRP Labelled Polymer Dako) or (Anti-mouse, EnVision + System-HRP Labelled Polymer, Dako) for incubation 1.5 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. The membranes were washed 3 times with 1 × TBST for 10 min. The protein bands were visualized using a Clarity™ Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad, US) and exposed to an iBright CL1500 Imaging System (Invitrogen). Results were standardized using housekeeping protein.

Transfection of small interfering (si)RNA and Lentivirus vector (LTV) of Scara5

siRNA-scramble (control) and siRNA against Scara5 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. ST2 cells were plated at 5 × 104 cells/well in the 24 well format. Transfection was performed by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, lnc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were transfected with 10–20 nM siRNAs and incubated for 48 h. Then, the medium was replaced with fresh adipocyte differentiation medium or osteogenic medium every 3–4 days until indicated days. The design, enveloping and titer determination of LTV- Scara5 were all conducted by VectorBuilder Inc. (Japan). LTV-Scara5 constructs were transduced into ST2 for 48 h at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 to 50. After 48 h, cells were examined under a microscope. LTV-EGFP was used for the control. Transfection efficiency was assessed 48 h post-transfection by qPCR.

RNA extraction and sequencing analysis

Human mesenchymal stem cells were induced into osteoblasts, followed by RNA extraction using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transcriptome profiling was conducted using next-generation sequencing by Azenta Japan corp. (Japan). The quality of the raw reads was evaluated using FastQC v0.11.9 (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and the Illumina Universal Adapter detected within the reads were trimmed using TrimGalore v0.6.10 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). The reads were then aligned to the human reference genome GRCh38 using the STAR v2.7.10b RNASeq aligner [53] and HTSeq v2.0.2 [54] was used to generate raw counts for each transcript. Differential expression analysis for the group comparison between control and Pyk2-Inh samples was performed using DESeq2 [55] in R. Gene Ontology (GO) annotation and KEGG pathway analyses were performed using the DAVID Bioinformatics resources version 6.8.

Statistical analysis

For differential expression analysis, Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust p-value for multiple comparisons, and genes that exhibited a false-discovery rate less than 0.01 and an absolute log2 fold change greater than 1 were considered significant. Results were shown as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism X9 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA) software program. The data were analyzed using one way-ANOVA, two way-ANOVA and Student’s t test. p value of < 0.05 represented statistical significance. NS indicates that a result was not significant.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Figure 1. Pyk2-targeted inhibitor promoted osteogenesis in stromal cells. Two inhibitors (PF-4618433; Pyk2-Inh and PF-431396; Pyk2/Fak-Inh) were compared to determine their effects on osteoblast differentiation. A and C) Panel A and C show the results of cell proliferation assessed using the CCK-8 kit in MC3T3-E1 (A) and ST2 cells (C), respectively. The cells were treated with the inhibitors for 48 hours. B and D) MC3T3-E1 cells (B) and ST2 cells (D) were induced to differentiate into osteoblasts under the osteogenic medium containing ascorbic acid (AA, 100 μg/mL) and β-glycerophosphate (β-GP, 5 mM). After 4 days of treatment with Pyk2 inhibitor, ALP activity was measured using ALP assay kit. *:P<0.05; **: P<0.01; ***: P<0.001; ****: P<0.0001. Supplementary Figure 2. Osteoblast differentiation enhanced by Pyk2 inhibitor. A) ST2 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate. Cells were then induced to differentiate into osteoblasts under the normal growth medium or osteogenic medium containing ascorbic acid (AA, 100 μg/mL) and β-glycerophosphate (β-GP, 5 mM). After 4 days of Pyk2-Inh treatment, ALP activity was measured using an ALP assay kit. B) Immunocytochemical staining was performed using anti-Tubulin (green) and nuclear (blue) stain. C) Immunoblotting assay was conducted for anti-phospho Pyk2, Pyk2 and Gapdh. Quantification of immunoblotting data was performed by ImageJ. 20 μM RGD-peptide was used to induce the signal stimulation. Supplementary Figure 3. Inhibition of Pyk2 signaling enhanced Wnt-related genes. hMSCs were cultured in osteogenic medium with Pyk2-Inh treatment for 4 days. RNA was purified and subjected for RNA sequencing analysis. A) Biological process, cellular components and molecular function were identified from the GO analysis. B, C) Disease and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was conducted. D) The transcriptional expression of DKK1, ROR2, LRP4 and SFRP2 was validated in hMSCs. Cells were treated with Pyk2-Inh for 4 days under osteogenic medium. E) Signaling molecules influenced by the Pyk2-Inh were visualized using Cytoscape. The areas highlighted in red boxes indicate the significantly affected regions. Supplementary Figure 4. Mechanism action of bone cells communications in bone marrow environments regulated by Pyk2 inhibitor. Pyk2 signaling is suppressed by Pyk2-Inh in the bone marrow environment, leading to the inhibition of adipocyte differentiation through Scara5 inhibition in MSCs, consequently reducing marrow adiposity. Additionally, Scara5 inhibition and Wnt1 promote osteoblast differentiation, thereby enhancing bone formation. Moreover, Pyk2 inhibition induces the expression of M-CSF and OPG secreted from osteoblasts, resulting in the suppression of osteoclast differentiation. Furthermore, it directly inhibits bone resorption function by suppressing the osteoclast differentiation derived from macrophages. Supplementary Figure 5. All full-length uncropped original western blots from Fig. 3E. Supplementary Figure 6. All full-length uncropped origianl western blots from Sup. Fig. 3C. Supplementary Table 1. Real-time PCR amplification primers for sequencing.

Authors’ contributions

J-W.L. conceived the study, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the project; J-W.L. designed the experiments and Y.L., M.N., and M.F. performed the experiments. S.S. and S.W.K. performed and interpretate RNA sequencing analysis. Y.Y., Y.Y., A.H., and T.I. provided insightful discussion. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI) grant number 23K09116, the Takeda Science Foundation, which were awarded to J-W.L. This work was partly supported by the JSPS KAKENHI grant number 23K16013, which was awarded to Y.L

Data availability

The RNA sequencing data of hMSCs are deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, Accession Number: GSE266328) and accessible online. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experiments using mice were approved by the Institutional animal care and use committee of Hokkaido University, Japan and were performed in accordance with the committee’s guiding principle (approval no.: 21-0018).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zaidi M. Skeletal remodeling in health and disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolamperti S, Villa I, Rubinacci A. Bone remodeling: an operational process ensuring survival and bone mechanical competence. Bone Res. 2022;10:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker MD, Shane E. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1979–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastell R, O’Neill TW, Hofbauer LC, Langdahl B, Reid IR, Gold DT, Cummings SR. Postmenopausal osteoporosis Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukasaki M, Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: evolving concepts in bone-immune interactions in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:626–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:638–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuck SP, Walker J. Adult Paget’s disease of bone. Clin Med (Lond). 2020;20:568–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazner F, Gowen M, Pavasovic D, Kola I. Osteopetrosis and osteoporosis: two sides of the same coin. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Q, Shou P, Zheng C, Jiang M, Cao G, Yang Q, Cao J, Xie N, Velletri T, Zhang X, et al. Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, Koo WW, Gordon PL, Neel M, Sussman M, Orchard P, Marx JC, Pyeritz RE, Brenner MK. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Med. 1999;5:309–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pino AM, Rosen CJ, Rodriguez JP. In osteoporosis, differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) improves bone marrow adipogenesis. Biol Res. 2012;45:279–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prestwich TC, Macdougald OA. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in adipogenesis and metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:612–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19:179–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushwaha P, Khedgikar V, Gautam J, Dixit P, Chillara R, Verma A, Thakur R, Mishra DP, Singh D, Maurya R, et al. A novel therapeutic approach with Caviunin-based isoflavonoid that en routes bone marrow cells to bone formation via BMP2/Wnt-beta-catenin signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5: e1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan EL, Brown MA. Clinical review 2: Genetic determinants of bone density and fracture risk–state of the art and future directions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2576–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou R, Cole SA, Graff M, Haack K, Laston S, Comuzzie AG, Mehta NR, Ryan K, Cousminer DL, Zemel BS, et al. Genetic variants affecting bone mineral density and bone mineral content at multiple skeletal sites in Hispanic children. Bone. 2020;132:115175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards JB, Zheng HF, Spector TD. Genetics of osteoporosis from genome-wide association studies: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:576–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckbinder L, Crawford DT, Qi H, Ke HZ, Olson LM, Long KR, Bonnette PC, Baumann AP, Hambor JE, Grasser WA 3rd, et al. Proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 regulates osteoprogenitor cells and bone formation, and offers an anabolic treatment approach for osteoporosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10619–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gil-Henn H, Destaing O, Sims NA, Aoki K, Alles N, Neff L, Sanjay A, Bruzzaniti A, De Camilli P, Baron R, Schlessinger J. Defective microtubule-dependent podosome organization in osteoclasts leads to increased bone density in Pyk2(-/-) mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1053–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posritong S, Hong JM, Eleniste PP, McIntyre PW, Wu JL, Himes ER, Patel V, Kacena MA, Bruzzaniti A. Pyk2 deficiency potentiates osteoblast differentiation and mineralizing activity in response to estrogen or raloxifene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;474:35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall JE, Fu W, Schaller MD. Focal adhesion kinase: exploring Fak structure to gain insight into function. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011;288:185–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaller MD. Cellular functions of FAK kinases: insight into molecular mechanisms and novel functions. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galli C, Piemontese M, Lumetti S, Manfredi E, Macaluso GM, Passeri G. GSK3b-inhibitor lithium chloride enhances activation of Wnt canonical signaling and osteoblast differentiation on hydrophilic titanium surfaces. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24:921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han S, Mistry A, Chang JS, Cunningham D, Griffor M, Bonnette PC, Wang H, Chrunyk BA, Aspnes GE, Walker DP, et al. Structural characterization of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2) reveals a unique (DFG-out) conformation and enables inhibitor design. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rattanawarawipa P, Pavasant P, Osathanon T, Sukarawan W. Effect of lithium chloride on cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation in stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Tissue Cell. 2016;48:425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler B, Blystone SD. Tyrosine phosphorylation of beta3 integrin provides a binding site for Pyk2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H, Lee YJ, Choi H, Seok JW, Yoon BK, Kim D, Han JY, Lee Y, Kim HJ, Kim JW. SCARA5 plays a critical role in the commitment of mesenchymal stem cells to adipogenesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, Landesberg R, Marx RE, Mehrotra B. American Association of O, Maxillofacial S: American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws–2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazziotti G, Biagioli E, Maffezzoni F, Spinello M, Serra V, Maroldi R, Floriani I, Giustina A. Bone turnover, bone mineral density, and fracture risk in acromegaly: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:384–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muhammad N, Luke DA, Shuid AN, Mohamed N, Soelaiman IN. Two different isomers of vitamin e prevent bone loss in postmenopausal osteoporosis rat model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:161527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Posritong S, Flores Chavez R, Chu TG, Bruzzaniti A. A Pyk2 inhibitor incorporated into a PEGDA-gelatin hydrogel promotes osteoblast activity and mineral deposition. Biomed Mater. 2019;14:025015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun C, Yuan H, Wang L, Wei X, Williams L, Krebsbach PH, Guan JL, Liu F. FAK Promotes Osteoblast Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Differentiation by Enhancing Wnt Signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:2227–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi S, Sun X, Choi HK, Yao J, Wang L, Wu G, He Y, Pan J, Guan JL, Liu F. FAK Promotes Early Osteoprogenitor Cell Proliferation by Enhancing mTORC1 Signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35:1798–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diacinti D, Diacinti D, Iannacone A, Pepe J, Colangelo L, Nieddu L, Kripa E, Orlandi M, De Martino V, Minisola S, Cipriani C. Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue Is Increased in Postmenopausal Women With Postsurgical Hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:e807–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR. Obesity and reproductive hormone levels in the transition to menopause. Menopause. 2010;17:718–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, Sato S, Takeuchi K, Igarashi K, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Krust A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor alpha and induction of Fas ligand in osteoclasts. Cell. 2007;130:811–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnan V, Bryant HU, Macdougald OA. Regulation of bone mass by Wnt signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett CN, Longo KA, Wright WS, Suva LJ, Lane TF, Hankenson KD, MacDougald OA. Regulation of osteoblastogenesis and bone mass by Wnt10b. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3324–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.You C, Shen F, Yang P, Cui J, Ren Q, Liu M, Hu Y, Li B, Ye L, Shi Y. O-GlcNAcylation mediates Wnt-stimulated bone formation by rewiring aerobic glycolysis. EMBO Rep. 2024;25:4465–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Lee JW, Asai M, Jeon SK, Iimura T, Yonezawa T, Cha BY, Woo JT, Yamaguchi A. Rosmarinic acid exerts an antiosteoporotic effect in the RANKL-induced mouse model of bone loss by promotion of osteoblastic differentiation and inhibition of osteoclastic differentiation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59:386–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luther J, Yorgan TA, Rolvien T, Ulsamer L, Koehne T, Liao N, Keller D, Vollersen N, Teufel S, Neven M, et al. Wnt1 is an Lrp5-independent bone-anabolic Wnt ligand. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(466):eaau7137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, Bennett CN, Lucas PC, Erickson RL, MacDougald OA. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science. 2000;289:950–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao C, Chen G, Kuan SF, Zhang DH, Schlaepfer DD, Hu J. FAK/PYK2 promotes the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway and intestinal tumorigenesis by phosphorylating GSK3beta. Elife. 2015;4:e10072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Narendra Talabattula VA, Morgan P, Frech MJ, Uhrmacher AM, Herchenroder O, Putzer BM, Rolfs A, Luo J. Non-canonical pathway induced by Wnt3a regulates beta-catenin via Pyk2 in differentiating human neural progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491:40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen T, Guo Q. Role of Pyk2 in Human Cancers. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:8172–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duong LT, Lakkakorpi PT, Nakamura I, Machwate M, Nagy RM, Rodan GA. PYK2 in osteoclasts is an adhesion kinase, localized in the sealing zone, activated by ligation of alpha(v)beta3 integrin, and phosphorylated by src kinase. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:881–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pfaff M, Jurdic P. Podosomes in osteoclast-like cells: structural analysis and cooperative roles of paxillin, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) and integrin alphaVbeta3. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2775–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams LM, Ridley AJ. Lipopolysaccharide induces actin reorganization and tyrosine phosphorylation of Pyk2 and paxillin in monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:2028–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Putri GH, Anders S, Pyl PT, Pimanda JE, Zanini F. Analysing high-throughput sequencing data in Python with HTSeq 20. Bioinformatics. 2022;38:2943–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Figure 1. Pyk2-targeted inhibitor promoted osteogenesis in stromal cells. Two inhibitors (PF-4618433; Pyk2-Inh and PF-431396; Pyk2/Fak-Inh) were compared to determine their effects on osteoblast differentiation. A and C) Panel A and C show the results of cell proliferation assessed using the CCK-8 kit in MC3T3-E1 (A) and ST2 cells (C), respectively. The cells were treated with the inhibitors for 48 hours. B and D) MC3T3-E1 cells (B) and ST2 cells (D) were induced to differentiate into osteoblasts under the osteogenic medium containing ascorbic acid (AA, 100 μg/mL) and β-glycerophosphate (β-GP, 5 mM). After 4 days of treatment with Pyk2 inhibitor, ALP activity was measured using ALP assay kit. *:P<0.05; **: P<0.01; ***: P<0.001; ****: P<0.0001. Supplementary Figure 2. Osteoblast differentiation enhanced by Pyk2 inhibitor. A) ST2 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate. Cells were then induced to differentiate into osteoblasts under the normal growth medium or osteogenic medium containing ascorbic acid (AA, 100 μg/mL) and β-glycerophosphate (β-GP, 5 mM). After 4 days of Pyk2-Inh treatment, ALP activity was measured using an ALP assay kit. B) Immunocytochemical staining was performed using anti-Tubulin (green) and nuclear (blue) stain. C) Immunoblotting assay was conducted for anti-phospho Pyk2, Pyk2 and Gapdh. Quantification of immunoblotting data was performed by ImageJ. 20 μM RGD-peptide was used to induce the signal stimulation. Supplementary Figure 3. Inhibition of Pyk2 signaling enhanced Wnt-related genes. hMSCs were cultured in osteogenic medium with Pyk2-Inh treatment for 4 days. RNA was purified and subjected for RNA sequencing analysis. A) Biological process, cellular components and molecular function were identified from the GO analysis. B, C) Disease and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was conducted. D) The transcriptional expression of DKK1, ROR2, LRP4 and SFRP2 was validated in hMSCs. Cells were treated with Pyk2-Inh for 4 days under osteogenic medium. E) Signaling molecules influenced by the Pyk2-Inh were visualized using Cytoscape. The areas highlighted in red boxes indicate the significantly affected regions. Supplementary Figure 4. Mechanism action of bone cells communications in bone marrow environments regulated by Pyk2 inhibitor. Pyk2 signaling is suppressed by Pyk2-Inh in the bone marrow environment, leading to the inhibition of adipocyte differentiation through Scara5 inhibition in MSCs, consequently reducing marrow adiposity. Additionally, Scara5 inhibition and Wnt1 promote osteoblast differentiation, thereby enhancing bone formation. Moreover, Pyk2 inhibition induces the expression of M-CSF and OPG secreted from osteoblasts, resulting in the suppression of osteoclast differentiation. Furthermore, it directly inhibits bone resorption function by suppressing the osteoclast differentiation derived from macrophages. Supplementary Figure 5. All full-length uncropped original western blots from Fig. 3E. Supplementary Figure 6. All full-length uncropped origianl western blots from Sup. Fig. 3C. Supplementary Table 1. Real-time PCR amplification primers for sequencing.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA sequencing data of hMSCs are deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, Accession Number: GSE266328) and accessible online. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.