Abstract

Background

Congenital malaria is an uncommon clinical infectious disease caused by vertical transmission of parasites from mother to child during pregnancy or delivery and a positive blood smear of malaria in newborns from 24 hours to 7 days of life, associated with a high mortality rate if it is not diagnosed and treated early.

Case summary

We present an unusual case of a 4-day-old boy with Plasmodium vivax malaria from Gondar, Ethiopia, suspected mainly based on a positive maternal history of malaria attacks in the seventh month of gestation and cured with artemether–lumefantrine therapy. The newborn presented with a lack of sucking and a high-grade fever. The blood film of the baby showed a trophozoite stage of Plasmodium vivax with a parasite density of +2. The neonate had severe thrombocytopenia (76,000/μL) and splenomegaly (the spleen was palpable 2 cm along the growth line). The patient was admitted to the hospital and was treated with artesunate and artemether–lumefantrine.

Conclusion

Most of the Amhara zones are endemic for malaria, and newborns born to mothers in malaria areas or those with a history of malaria attacks in the index pregnancy should be investigated early for malaria rather than treated with sepsis or meningitis. It is wise to consider congenital malaria as part of neonatal sepsis-like presentations, especially if there is a maternal history of malaria attack during pregnancy and if the neonates fully recover.

Keywords: Congenital malaria, Case report, Ethiopia, Plasmodium vivax

Introduction

Congenital malaria is an uncommon clinical infectious disease caused by vertical transmission of parasites from mother to child during pregnancy or delivery and a positive blood smear for malaria in newborns from 24 hours to 7 days of life [1, 2]. Fever, anemia, jaundice, vomiting, lethargy, convulsions, irritability, tachypnea, respiratory distress, and hepatosplenomegaly are nonspecific symptoms that mimic neonatal sepsis syndrome [3, 4]. Regardless of clinical symptoms, congenital malaria is defined as the presence of asexual malaria parasites in the cord and/or peripheral blood of an infant during the first week of life [5, 6]. Due to variations in the definition of congenital malaria, maternal immunity, and the types of diagnostic tools used, the prevalence of congenital malaria varies from 0% to 54% in sub-Saharan Africa [5].

It is a rare condition and develops into a serious illness that can cause severe morbidity and death in newborns. Plasmodium falciparum causes congenital malaria, which can also be caused by Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium malaria [7]. It is often incorrectly treated as newborn sepsis owing to a low index of suspicion and nonspecific symptoms, increasing the risk of infant death and morbidity [4].

In apparent neonatal death, malaria infection during pregnancy is a serious public health issue related to unfavorable pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight (LBW), abortion, stillbirth, restriction of intrauterine development restriction, and early delivery [8]. The possibility of false negative findings along with the accessibility and precision of diagnostic tests play a role in the early detection of congenital malaria. Furthermore, some newborns do not develop signs infection for a few weeks after delivery, which could postpone identification and treatment. Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) should be administered as intermittent preventive therapy (IPT) to all pregnant women in regions of stable malaria transmission as part of the World Health Organization (WHO) plan to avoid congenital malaria [7].

Case description

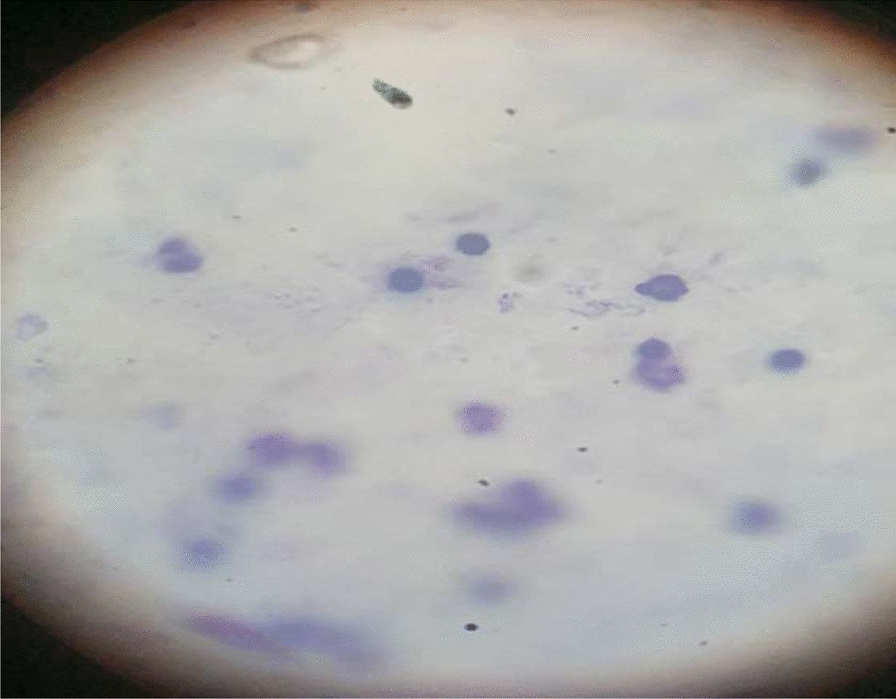

This is the case of a newborn boy from Gondar, Ethiopia who is 3 days old. He was referred to the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital from the primary hospital due to fever, decreased sucking, and decreased mentation. He was born to a 28-year-old para 4 all-alive mother who had amenorrhea for 9 months. She had four antenatal care (ANC) follow-ups, and routine care was provided, such as iron and folic acid supplementantion, and a tetanus vaccine was administered. She underwent screening for retroviral infection and sexually transmitted diseases, all of which came back negative. Spontaneous labor was induced, resulting in the birth of a healthy male neonate weighing 3300 g. The baby immediately cried and had Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at the first and fifth minutes, respectively. However, after delivery, the neonate did not suckle and experienced three episodes of abnormal body movements, along with decreased mentation. On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: apical heart rate of 169 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 53 breaths per minute, and temperature of 38.3 °C. The neonate’s birth anthropometry parameters were within the normal range, and the respiratory and cardiac examinations were normal. However, the abdominal exam revealed a spleen palpable at 2 cm and a liver palpable at 3 cm. The neonatal reflexes, such as sucking and the Moro reflex, were not sustained. However, the tone was normal. Due to these symptoms, early-onset neonatal sepsis was suspected, and intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone and ampicillin) were initiated. Additionally, a blood culture was performed, which did not reveal any abnormalities. The random blood sugar level was measured at 79 mg/dl, and electrolyte derangement was observed. However, the kidney function test was within the normal range. A complete blood count was performed and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was done; the results were normal (Table 1). The neonate did not improve, and a blood film was made, resulting in P. vivax with parasitic load of +2 being identified (Fig. 1). The mother had a history of fever, arthralgia, myalgia, and loss of appetite, for which a blood film was made, P. vivax was diagnosed, and oral antimalarial was administered. The neonate was administered intravenous artemether–lumefantrine 3 mg/kg (at 0 hours, at time of admission, 12 hours, 24 hours, and 48 hours, then daily for 2 days) and improved.

Table 1.

Laboratory results of of a 3-day-old newborn at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia, 2024

| Types | Result |

|---|---|

| White blood count (WBC) | 11.0 × 103/µL |

| Neutrophil | 90.3% |

| Hemoglobin (HGB) | 12.7 mg/dl |

| Platelet | 76,000/µl |

| Na | 148 mmol/l |

| K | 5.74 mmol/l |

| Creatinine | 0.35 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) | 40 |

| Bilirubin total | 6 mg/dl |

| Bilirubin direct | 1.07 mg/dl |

| Blood film | P. vivax +2 |

Fig. 1.

Blood film results of a 3-day-old newborn at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia, 2024

Discussion

In this case report, a description of congenital malaria is made in a setting that introduced routine neonatal malaria testing for neonates coming from malaria-endemic areas. In Ethiopia, the common plasmodium protozoa are P. vivax and P. falciparum. The finding revealed that a 4-day-old newborn had congenital malaria.

In 2019, there were 229 million malaria cases, accounting for more than 94% of the anticipated 409,000 deaths worldwide. Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for more than 94% of all cases and deaths. Children under the age of 5 years are the most vulnerable, accounting for 67% (274,000) of all malaria fatalities globally in 2019 [2].

Congenital malaria has been documented to present with anemia, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, poor feeding, lethargy, irritability, and jaundice [9].

Congenital malaria develops when a mother has active malaria during pregnancy, and the parasite crosses the placenta to infect the fetus [10]. In our case, the mother had one episode of malaria infection and was from a malaria endemic area.

Newborns are believed to have partial protection from malaria in the first few months of life, due to passively acquired maternal immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, the predominance of hemoglobin F (HbF) in their erythrocytes, and the low levels of iron and para-aminobenzoic acid (both required for parasite growth) in breast milk [2]. However, the mothers attack vulnerable time for transmission in fetal gestation.

During the abdominal examination, hepatomegaly was noted, measuring 3 cm below the right costal margin, along with splenomegaly measuring 2 cm. Additionally, electrolyte imbalances were observed, and the neonatal reflex sucking was not sustained. The Moro reflex was found to be incomplete, and the complete blood count (CBC) result indicated thrombocytopenia (49,000/µl) and neutrophilia (90.3%).

Diagnosing congenital malaria can be challenging due to its rarity and similarity to other neonatal conditions such as sepsis. However, this particular neonate was tested for malaria on the basis of the maternal history of malaria during pregnancy and coming from malaria-endemic areas. Initially, the neonate was started on intravenous antibiotics, which was an appropriate course of action as bacterial sepsis is the most common disorder in newborns.

Conclusion

Most of the Amhara zones are endemic for malaria, and newborns born to mothers in malaria areas or with a history of malaria attacking in the index pregnancy should be investigated early for malaria rather than treated with sepsis or meningitis. It is always wise to consider congenital malaria as part of neonatal sepsis-like presentations, especially if there was a maternal history of malaria attack during pregnancy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the parent of the patient for allowing the publication of this case report. Institutional approval is not required to publish the case details.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal care

- BF

Blood film

- CBC

Complete blood count

Author contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the reported work, whether it is in the conception, design of the study, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or all these areas; they participated in the writing and critical review of the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be responsible for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding source.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Wallaga University Referral Research Ethics Review Committee. The study protocol is carried out according to the relevant guidelines.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's legal guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rai P, Majumdar K, Sharma S, Chauhan R, Chandra J. Congenital malaria in a newborn: a case report with a comprehensive review of differential diagnosis, treatment, and prevention from an Indian perspective. J Parasit Dis. 2015;39:345–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kajoba D, Ivan Egesa W, Jean Petit H, Omar Matan M, Laker G, MugowaWaibi W, et al. Congenital malaria in a 2-day-old newborn: a case report and review of the literature. Case Reports Infect Dis. 2021. 10.1155/2021/9960006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Alessandro U, Ubben D, Hamed K, Ceesay SJ, Okebe J, Taal M, et al. Is malaria in infants under six months of age-is it an area of unmet medical need? Malar J. 2012. 10.1186/1475-2875-11-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohan K. Clinical presentation and management of neonatal malaria: a review. Malaria Contr Elimin. 2014;3(2):126. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uneke CJ. Congenital plasmodium falciparum malaria in sub-saharan Africa: a rarity or a frequent occurrence? Parasitol Res. 2007;101:835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enweronu-Laryea CC, Adjei GO, Mensah B, Duah N, Quashie N. Prevalence of congenital malaria in high-risk Ghanaian newborns a cross-sectional study. Malaria J. 2013;12(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassan L, Abdul M, Ogala W, Care N. Congenital malaria prevalence, risk factors and clinical correlates in a tertiary hospital in Zaria Nigeria. J Perinat Neonat Care. 2023;3(1):29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beeson JG, Scoullar MJ. Combating low birth weight due to malaria infection in pregnancy. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nwaneli EI, Nri-Ezedi CA, Okeke KN, Edokwe ES, Echendu ST, Iloh KK. Congenital cerebral malaria: a masquerader in a neonate. Malar J. 2022;21(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organization WH. WHO guidelines for malaria, 14 March 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.