Abstract

Genetic generalized epilepsy (GGE) including childhood absence epilepsy, juvenile absence epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), and GGE with tonic–clonic seizures (TCS) (GGE-TCS), is genetically influenced with a two- to four- fold increased risk in the first-degree relatives of patients. Since large families with GGE are very rare, international studies have focused on sporadic GGE patients using whole exome sequencing, suggesting that GGE are highly genetically heterogeneous and rather involve rare or ultra-rare variants. Moreover, a polygenic mode of inheritance is suspected in most cases. We performed SNP microarrays and whole exome sequencing in 20 families from Sudan, focusing on those with at least four affected members. Standard genetic filters and Endeavour algorithm for functional prioritization of genes selected likely susceptibility variants in FAT1, DCHS1 or ASTN2 genes. FAT1 and DCHS1 are adhesion transmembrane proteins interacting during brain development, while ASTN2 is involved in dendrite development. Our approach on familial forms of GGE is complementary to large-scale collaborative consortia studies of sporadic cases. Our study reinforces the hypothesis that GGE is genetically heterogeneous, even in a relatively limited geographic area, and mainly oligogenic, as supported by the low familial penetrance of GGE and by the Bayesian algorithm that we developed in a large pedigree with JME. Since populations with founder effect and endogamy are appropriate to study autosomal recessive pathologies, they would be also adapted to decipher genetic components of complex diseases, using the reported bayesian model.

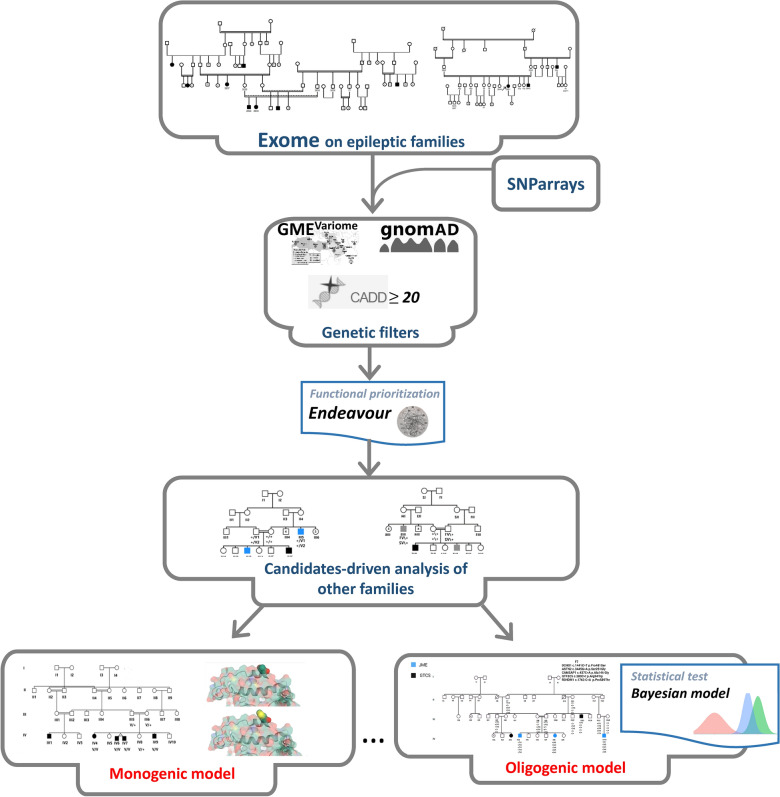

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40246-024-00659-9.

Keywords: GGE, JME, FAT1, DCHS1, ASTN2, Oligogenic, Polygenic, Bayesian model

Introduction

Generalized genetic epilepsies (GGE), which account for 15–30% of all epilepsy, appear in childhood or adolescence and often persist into adulthood. GGE comprises four syndromes, namely childhood absence epilepsy (CAE), juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE), juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), and epilepsy with generalized tonic–clonic seizures alone (GTCS). GGE is genetically influenced with a two- to four-fold increased risk in the first-degree relatives of patients and a proportion of GGE patients with a positive family history (≥ 1 first-degree relative with epilepsy) is about 15%. Moreover, the GGE syndrome of a relative may differ from that of the proband [1]. However, large families in which GGE segregates are rare: in few families with autosomal dominant JME, variants have been identified in the GABRA1 gene, encoding the α1 subunit of the GABAA receptor [2] or in the EFHC1 gene, encoding Myoclonin-1 [3, 4]. However, the causative role of the EFHC1 variants has been debated in different studies [5]. By combining genetic and electrophysiological approaches, rare coding variants in genes encoding subunits of the GABAA receptor, especially GABRB2 and GABRA5, have been implicated in a cohort including American, European and Turkish patients with sporadic GGE [6].

Most studies have been performed in large international cohorts of sporadic cases with GGE by Whole Exome Sequencing (WES), and supported the hypotheses that GGE (i) are highly genetically heterogeneous , (ii) involve rare or ultra-rare variants and (iii) are determined by an oligogenic mode of inheritance [7–9]. In these conditions, a few genes have been reported as susceptibility genes for GGE, including SCN1A, GABRG2 and SLC6A1, encoding the α1 subunit of the sodium voltage-gated channel, the γ2 subunit of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-A receptor and the GABA transporter, respectively [10–12].However, it is difficult to infer which pathways play an important role in the pathomechanism of GGE [13].

Recently, in Sudanese families with GGE, we reported rare missense variants of ADGRV1 gene [14], encoding the adhesion G protein–coupled receptor V1 [15]. While loss of function variants in ADGRV1 are responsible for the rare autosomal recessive Usher IIC syndrome, the homozygous c.6835delG (p.Val2250*) variant in Mass1 (the mouse orthologous gene of ADGRV1) causes generalized auditory-induced seizures in the Frings mouse [16].

In this study, we report the results of a genetic screening in a cohort of 20 Sudanese families with GGE. We performed SNP microarrays in 20 index cases and at least one affected relative and interpreted WES in five families with at least four patients with GGE. Genes with candidate variants identified in the previous step were analyzed in the WES of probands from the 11 remaining families.

Patients and methods

Ethical approval

This study was prospectively reviewed and approved by the national health research ethics committee, Federal ministry of health, Sudan (1–4–18). Written informed consent was given by all participants.

Patients’ cohort

Twenty Sudanese families with GGE were ascertained. In each family, we recruited the proband (n = 20) along with all available affected family members (n = 36) and asymptomatic relatives (n = 84). The total number of patients sampled was 56. Inclusion criteria for patients were clinical presentation of generalized epilepsies with a positive family history of epilepsy. Patients with focal seizures or epileptic encephalopathies were excluded. Patients were examined and diagnosed by the referring consultant neurologists/neuro-pediatricians, followed by a second standardized phenotyping by clinicians of the research team (EM, AM). Healthy relatives were examined to exclude subtle phenotypes. Electroencephalogram (EEG) was performed for at least one patient per family.

Penetrance calculation using PENCALC

After all the pertinent data were keyed in, the PENCALC program exhibited the estimate of the penetrance rate K, its exact 95% confidence interval [95% CI(K)], and the formula for the corresponding likelihood function. When the genealogy contained consanguineous trees, the program also showed the partial values of K used for estimating the final value of the penetrance rate [17].

SNP microarrays

Thirty-five individuals including 20 index cases and 15 affected relatives were genotyped using 660W-Quad microarrays (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Automated Illumina microarray experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Image acquisition was performed using an iScan System (Illumina). Image analysis and automated CNV calling was performed against the human GRCh37 reference using GenomeStudio v.2011.1 and CNVPartition v.3.1.6 with the default confidence threshold of 35. We also used a size threshold of 20 kb since CNVs < 20 kb detected by 660W-Quad microarrays proved to be false positives. Identified CNVs were systematically compared with those present in the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV), excluding BAC-based studies, using an in-house bioinformatics pipeline, to assess their frequency in control populations. Only CNVs identical (breakpoints and copy number) to or totally included in those described in the DGV were considered; microrearrangements partially overlapping CNVs described in DGV or with a discordant copy number were treated as novel. CNVs with a minor allele frequency ≥ 1% in at least one study comprising ≥ 30 controls were excluded from further analysis. CNVs encompassing coding regions, and with a frequency < 1%, were considered as possibly deleterious. CNV frequencies were compared with the Mann–Whitney or unilateral Fisher's exact tests. Candidate genes present in the CNVs were compared with those present in AutDB [18] (http://www.mindspec.org/autdb.html).

Whole exome sequencing

WES was performed in 40 affected members from F7, F8, F12, F14 and F19 families with at least 4 patients with available DNA, and at least the proband of the 13 remaining families. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Exome v3 array (Nimblegen Inc., Madison, WI) and sequenced as 150-bp paired-end reads on the Nextseq 500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), at the iGenSeq sequencing platform at ICM (Paris). Reads were processed following a standard analysis pipeline at the Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital. Overall sequencing quality was assessed with FastQC v0.11.8, the reads were then aligned to the reference human genome sequence (hg19) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner BWA-mem v0.7.17, the alignment files were sorted and indexed using Samtools v1.9, and Sambamba v0.7.0 was used to flag duplicates. Variants were called using GATK Software v4.1.4 on Gencode v30 basic CDS targets. Multi-allelic variants were split and indels were normalized using vt 0.57721. The potential splicing effect of all variants were predicted using SpliceAI, with a 10 000 bp analysis window [19]

Variant selection, prioritization and validation

WES data were analyzed with two different strategies: shared homozygous variants, and all other shared variants (heterozygous or homozygous). First, variants, which were found homozygous in all affected individuals within the same family and present in < 20 homozygous carriers in gnomAD were analyzed. For the second strategy, shared variants were filtered out if they met one or more of the following exclusion criteria: (i) variants already identified in one or more of homozygous carriers in our in-house database, indicating artifacts (n = 943 WES, this database not including the individuals of this study), (ii) variants with a maximum allele frequency ≥ 1% in gnomADv2 [20] or in GME (http://igm.ucsd.edu/gme/) [21], (iii) variants which are not shared by all affected members within the family, (iv) non coding (intronic, UTRs) or synonymous variants with SpliceAI delta scores < 0.2, (v) variants only affecting minor isoforms of the gene, i.e. variants with pext score/gene maximal pext score ratio < 0.1 [22].

Candidate variants were prioritized based on: (i) their frequency in the closest control populations with large available WES or WGS data, African controls extracted from gnomADv2 database and from GME variome database, (ii) their classification in ClinVar dataset (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), and (iii) the pathogenicity prediction according to CADD v1.4 with a score ≥ 20 predicting the 1% most deleterious variants in the gene [23], M-CAP [24] and REVEL [25].

Endeavour algorithm was used to prioritize the candidate genes with relevance to the disease, phenotype, or biological process of interest, taking into account seed genes already incriminated in GGE (Table S1) [26]: (i) genes reported in at least a study with a statistically significant link to GGE [2, 3, 27–49], (ii) those recurrently ranked in the top 10 candidate genes in WES case–control studies [10, 50, 51] or genes whose knock-out caused generalized epilepsy in animal model including BSN [52], JRK [53], GRIA4 [54] or SV2A [55, 56].

Candidate variants were then validated and checked for segregation within the families, and screened in 119 Sudanese controls by Sanger sequencing, according to standard procedures.

Linkage analyses

Lod scores were calculated using the MERLIN package. For the FAT1 variant in the family F19, an autosomal recessive inheritance was assumed. A disease allele frequency of 0.0001, a phenocopy rate of 0.0001 and a complete penetrance for homozygotes were considered. An allele frequency of 0.00005 was used for the c.13757C > T (p.Thr4586Met) variant.

For the Family 12, an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with incomplete penetrance was selected as well as the previous value for disease allele frequency and phenocopy rate. A penetrance of 0.34 was estimated with the PENCALC method [17]. A multipoint linkage analysis was performed with c.63578G > A (p.Arg21193His) and c.28299C > G (p.Asp9433Glu) in TTN and the c.310 T > C (p.Ser104Pro) variant in SLC38A11. A recombination rate of 0.1% and 1.5% was used between the two TTN variants and between TTN and SLC38A11 gene, respectively. An allele frequency of 0.0004, 0.0018 and 0.006 was considered for c.63578G > A (p.Arg21193His) and c.28299C > G (p.Asp9433Glu) in TTN, and c.310 T > C (p.Ser104Pro) variant in SLC38A11, respectively (from North African-Arab population extracted from GME Variome).

Bayesian model of oligogenism

In order to take into account the unobserved genotypes in the family 7, we followed Lauritzen and Sheehan [57] and used a Bayesian network to model the theoretical transmission of alleles in the pedigree. The model included the five bi-allelic loci of interest (DCHS1, ASTN2, CAMSAP1, GTF3C5, R3HDM1), a Mendelian transmission of allele taking into account the linkage between three loci (ASTN2—13 cM—CAMSAP1—3 cM—GTF3C5), and the following conservative minor allele frequencies: 0.0005 for DCHS1, 0.0013 for ASTN2, 0.0010 for CAMSAP1, 0.0010 for GTF3C5, and 0.0025 for R3HDM1 (from North African-Arab population extracted from GME Variome). The resulting Bayesian network as a total of 975 variables, and inference using the sum-product algorithm (Koller and Friedman [58]— Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principle and Techniques) results in a junction tree decomposition of 793 cliques where the largest clique has 21 binary variables, with a total inference complexity of 5,248,864. The available genotypes or partial genotypes of 13 individuals were injected in the Bayesian network, and a total of 50,000 full genotypes were sampled conditionally to this evidence. Simulated data are available in supplementary material (Table S2). These data were used to obtain the posterior distribution of individuals’ joint genotypes and of the number of family carriers. In order to test the association between carriers of the 5 variants and JME affected, fisher exact test was performed for each of the 50,000 statistical replications.

Structural analysis

For the modeling of FAT1 NM_005245.4:c.13757C > T p.(Thr4586Met), the wild type structure of the last 377 residues of FAT1 (Uniprot Q14517) has been obtained by using RoseTTaFold [59]. Among the various models proposed, the model with the minimal error estimate has been selected. The Threonine to Methionine change has been introduced to the wild type structure by missense3D [60].

For the modeling of ASTN2 NM_001365068.1:c.3448A > G p.(Ser1150Gly), the structure 5J67 was used as wild type template [61]. The Serine to Glycine structural change was generated by missense3D [35].

The structures were visualized using the RCSB pairwise alignment tool https://www.rcsb.org/alignment [62].

Results

Mode of inheritance in selected families

The families F7, F8, F12, F14, and F19 with at least 4 patients or obligate carriers were selected in order to search for candidate variants by comparing WES of patients within the family. The clinical features of the affected members of these families are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical data of the different families

| Family id | Patient no | Sex | Age at seizure onset | Age at examination | Epilepsy type | Sz/week before treatment | Triggering stimulus | Neurological examination | Current therapy | Response to treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F7 | IV10 | M | 20Y | 26Y | JME | Unspecified | None | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F7 | III13 | M | 9Y | 37Y | GGE-TCS | 0_1 | Lack of sleep/Fatigue | Normal | Carbamazepine | Responder |

| F7 | IV4 | M | 20y | 23y | JME | 0_1 | None | Finger deformity | Carbamazepine | Responder |

| F7 | IV8 | F | 15y | 16y | JME | 2_3 | None | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F12 | IV11 | M | 6 Y | 7 Y | CAE | 14_21 | None | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F12 | V1 | M | 5 M | 6 Y | GGE-TCS | 1_2 | None | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F12 | IV4 | M | 3Y | 11Y | GGE-TCS | 7_8 | None | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F12 | IV12 | F | 5Y | 7Y | GGE-TCS | More than 14 times | None | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F12 | IV14 | F | 12Y | 16Y | CAE/GGE-TCS | 0_1 | None | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F14 | IV5 | M | 10 Y | 52Y | GGE-TCS | 5_7 | TV/lack of sleep | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F14 | V3 | M | Birth | 21 y | GGE-TCS | 3_5 | Watching TV, Looking at sun light | Normal | Na valproate plus Levitracitam | Poor sz control |

| F14 | V4 | F | 10 y | 19 y | GGE-TCS | 10_14 | Watching TV/sitting in front of the computer | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F14 | IV4 | F | 10 y | 46 y | GGE-TCS | 8_14 | Watching TV | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F14 | V11 | F | 16Y | 20Y | GGE-TCS | 3_4 | Sun exposure,mental or physical stress | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F19 | IV9 | M | 20 Y | 24 Y | GGE-TCS | 2_3 | Excessive activity, fatigue | Mild motor deficit in the upper and lower limbs, mild cerebellar ataxia | Na valproate | Responder |

| F19 | IV4 | F | 4 Y | 10 Y | GGE-TCS | 0_1 | Lack of sleep | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F19 | IV6 | M | 8 Y | 8 Y | GGE-TCS | 0_1 | Lack of sleep | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

| F19 | IV7 | M | 8 Y | 8 Y | GGE-TCS | 0_1 | Nothing specific | Normal | Na valproate | Responder |

The inspection of the pedigrees allowed determining a likely mode of inheritance in 2/5 of these families. In F19, all affected members were born to healthy parents related by short consanguinity loops, highly suggesting an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance (Fig. 1a). In F8, since only males were affected and females were asymptomatic carriers, the most probable transmission was recessive X-linked or autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance (Fig. 2c). In contrast, it was difficult to determine the transmission of GGE in F7 (Fig. 2a), F12 (Fig. 3a), and F14 (Fig. 4). For example, F7 presented with two affected sibs IV4 and IV8 with JME born from related parents, who also had a second cousin IV10 with JME from a priori non-related parents and an uncle III13 with a different GGE phenotype (GGE-TCS) (Fig. 2a). In F12, two patients, IV7 and IV11, were issued from different consanguinity loops, but the 5 other affected members originated from unrelated parents and a vertical transmission by an asymptomatic carrier IV3 can be suspected in one branch (Fig. 3a). In F12 and F14, the epileptic trait occurred in a given generation (sibs and first cousins), which could be vertically transmitted to the next generation. The penetrance of GGE in F7 and F12 using PENCALC algorithm [17] was very low, 0.27 and 0.34, respectively.

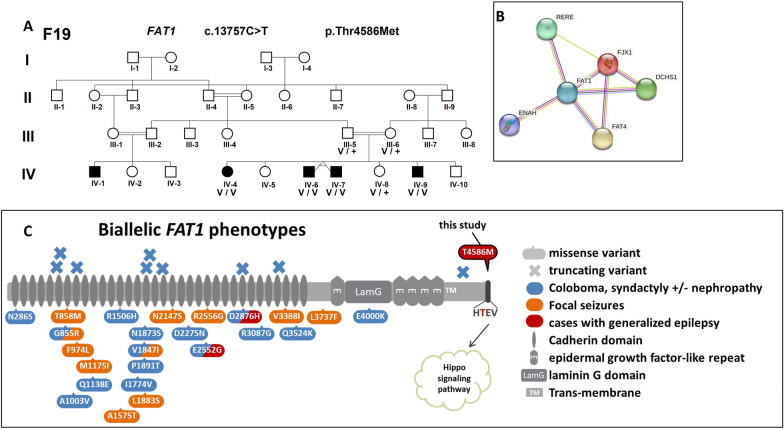

Fig. 1.

a Segregation of FAT1 variant in F19; b FAT1 interactome network according to STRING-db, showing close interactions with DCHS1 and FAT4; c Biallelic FAT1 variants involvement in human diseases: all previously published missense are located in the FAT1 extracellular domains, The T4586 from F19 is outlined in black, located in the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain containing a PTB-like motif (dark grey) with a PDZ-binding motif (-HTEV)

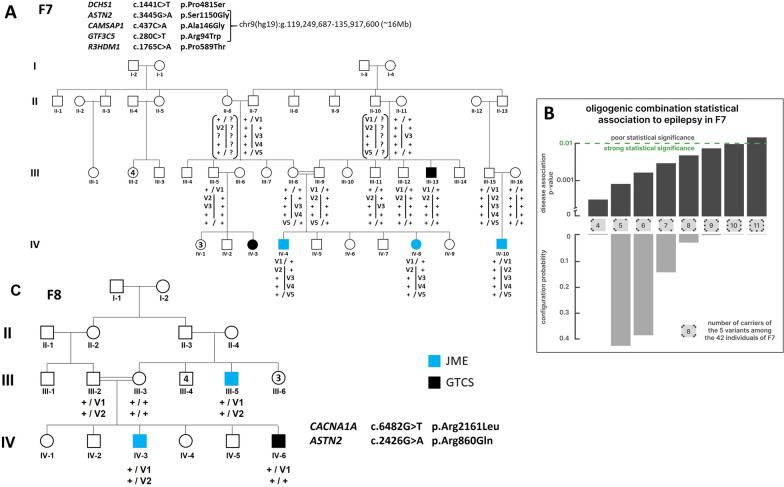

Fig. 2.

a Segregation of DCHS1 and ASTN2, CAMSAP1, GTF3C5 and R3HDM1 variant in F7; b Probabilities of each predicted combination of indivuals bearing the five F7 variants calculated with the oligogenic Bayesian model; C, CACNA1A and ASTN2 variant in F8. Symbols in blue indicated JME and in black GTCS-GGE. The symbol “ + ” corresponded to the wild-type allele and “v” to the candidate variant. The vertical bar (a) shared the chromosome 2q haplotypes bearing the ASTN2, CAMSAP1 and GTF3C5 genes

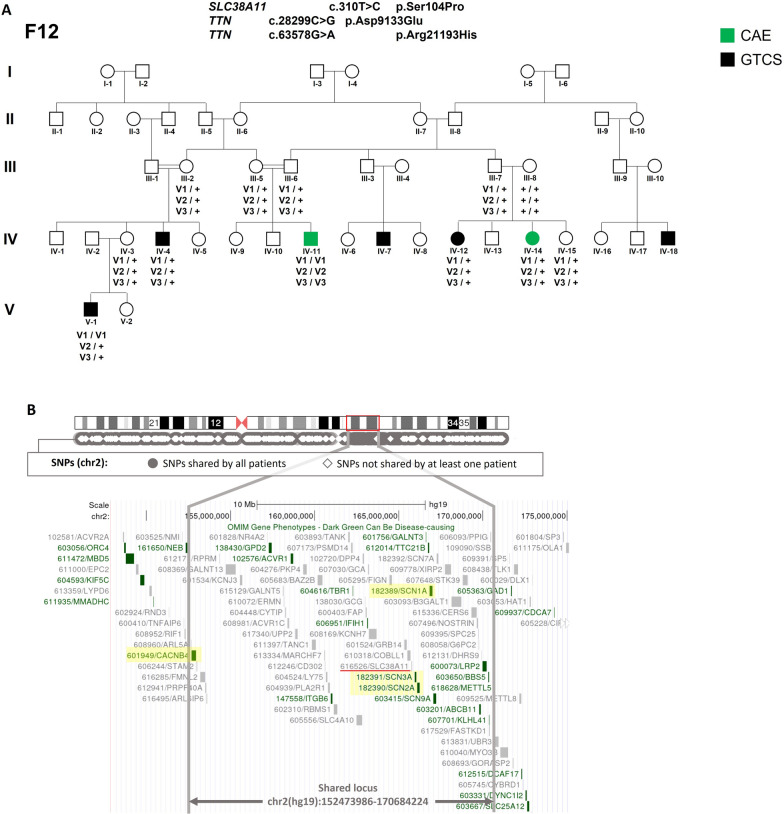

Fig. 3.

a Segregation of SLC38A11 and TTN variants in F12. Symbols indicated in green corresponded to CAE and in black to GTCS. The symbol “ + ” corresponded to the wild-type allele and “v” to the candidate variant. b Refinement of the candidate 2q region using WES data. Black circles represented variants shared by all 5 patients and white diamonds, variants not shared by at least one patient. The candidate region was delineated on the chromosome 2 scheme by a red square and on the genemap by the two grey vertical lines. Epilepsy genes were highlighted in yellow

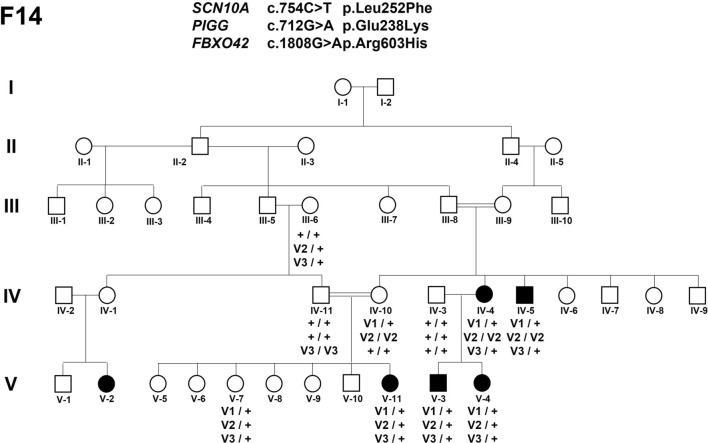

Fig. 4.

Segregation of SCN10A, PIGG and FBXO42 variants in F14. Symbols in black indicated GTCS-GGE. The symbol “ + ” corresponded to the wild-type allele and “v” to the candidate variant

Analysis of CNVs

The detection of rare CNVs was performed in the 20 index cases and 15 additional patients from F7, F8, F12, F14 and F19 families. The already published recurrent microdeletions at 15q11.2, 15q13.3 and 16p13.11 in GGE patients [47] as well as the 22 recently reported seizures-associated CNV [63] were not found in our cohort. We identified 6 rare CNVs, 4 deletions and 2 duplications, which were shared by at least 2 families. Their sizes ranged from 75 to 224 kb. Among them, 4 were identified in more than two families (Table S3). The limits of the duplication at 10q26 slightly varied from one family to another and were centered on the Chr10q26 (135,508,269–135290022) interval of 220 kb, including Cen-CYP2E1-FRG2B-SYCE1-DUX4-DUX4L3-tel. None of these genes were obvious candidate for GGE. The 5 remaining rearrangements were intragenic. Two were located in introns of SUMF1 or KANK1 gene, with no predictable consequences. The 75 bp deletion in IFNAR2 gene was localized within untranslated exon 1. The intragenic duplication of exon 2 to 11 in CES1 gene likely changed the translation of this gene. CES1 was weakly expressed in brain and its function as a member of the carboxylesterase family could not be related to epilepsy. The deletion of exon 1 and 2 of CYP1B1 likely constituted a loss of function variant. However, pathogenic variants in CYP1B1 at the homozygous or compound heterozygous state caused primary open-angle glaucoma [64]. Moreover, none of these identified CNV segregated with GGE in family F7, F8, F12, F14 or F19 (Table S3). In addition, none of the candidate genes determined by WES (see below) (Table 2) was harbored in the regions with copy number variations.

Table 2.

Genetic data of the different genes from families F7, F12, F14, F18, F19.M-Cap D: disease causing/possibly pathogenic T: tolerated/likely Benign

| Gene | Family | gDNA | cDNA | Protein variant | M-cap | CADD | gnomADv4 | GME (NEA + AP) | Sudanese ontrols (n = 119) | Domain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Africans | ||||||||||

| FAT1 | F19 | chr4(hg38):g.186588602G > A | NM_005245.4:c.13757C > T | p.(Thr4586Met) | D | 26 | 0.00005 | 0.00004 | absent | Zero | Not in an identifiable domain |

| FBXO42 | F14 | chr1(hg38):g.16251016C > T | NM_018994.3:c.1808G > A | p.(Arg603His) | T | 25 | 0.00002 | 0.00004 | 0.0009 | 0.004 (1 control) | Not in an identifiable domain |

| PIGG | F14 | chr4(hg38):g.507546G > A | NM_001127178.3:c.712G > A | p.(Glu238Lys) | D | 28.2 | 0.00005 | 0.004 | 0.008 (2 controls) | Phosphodiest | |

| SCN10A | F14 | chr3(hg38):g.38761321G > A | NM_006514.4:c.754C > T | p.(Leu252Phe) | D | 26.3 | Absent | Absent | Absent | Zero | TMhelix |

| CAMSAP1 | F7 | chr9(hg38):g.135881781G > C | NM_015447.4:c.437C > G | p.(Ala146Gly) | T | 22 | 0.00008 | 0.0008 | 0.002 | 0.008 (2 controls) | – |

| GTF3C5 | F7 | chr9(hg38):g.133042213C > T | NM_012087.4:c.280C > T | p.(Arg94Trp) | D | 24 | 0.00005 | 0.00007 | Zero | Not in an identifiable domain | |

| R3HDM1 | F7 | chr2(hg38):g.135651874C > A | Nm_015361.2:c.1765C > A | p.Pro589Thr | T | 23.7 | 0.00008 | 0.0011 | 0.04 (10 controls) | – | |

| DCHS1 | F7 | chr11(hg38):g.6640173G > A | NM_003737.4:c.1441C > T | p.(Pro481Ser) | T | 21.9 | 0.00001 | 0.00019 | Zero | 0.008 (2 controls) | Cadherin 5 |

| DCHS1 | F18 | chr11(hg38):g.6622335G > A | NM_003737.4:c.9341C > T | p.(Ala3114Val) | T | 19.33 | 0.000004 | 0.00001 | Absent | Zero | Not in an identifiable domain |

| ASTN2 | F7 | chr9(hg38):g.116487408 T > C | NM_001365068.1:c.3448A > G | p.(Ser1150Gly) | T | 23.9 | 0.00006 | 0.001 | Absent | Zero | EGF-Like3 |

| ASTN2 | F8 | chr9(hg38):g.116729039C > T | NM_001365068.1:c.2579G > A | p.(Arg860Gln) | D | 24 .3 | 0.00003 | 0.00001 | Absent | 0.004 (1 control) | Not in an identifiable domain |

| SLC38A11 | F12 | chr2(hg38):g.164939509A > G | NM_001351537.2:c.478 T > C | p.(Ser160Pro) | T | 22.6 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.006 | 0.012 (3 controls) | TMhelix |

| CACNA1A | F8 | chr19(hg38):g.13209374C > A | NM_001127222.2:c.6464G > T | p.(Arg2155Leu) | D | 23 | 0.00007 | 0.00085 | 0.002 | 0.03 | Not in an identified domain |

Candidate variants detected in WES

For family F8 (see pedigree in Fig. 2c), no candidate variants have been identified at the homozygous or hemizygous state in X-linked genes. In contrast, our prioritization process retained 39 rare missense variants at the heterozygous state (Table S4). Among them, the best candidate pointed out by the Endeavour algorithm (top 1 of candidates for all families, Table S1) was the c. 6464G > T (p. Arg2155Leu) in CACNA1A encoding the α1 subunit of the voltage-gated channel, which had already been involved in GGE [65] and epileptic encephalopathies. In addition, a spontaneous frameshift variant at homozygous state was shown responsible for the well-known mice model of absence epilepsy, the tottering mice [66]. This variant was predicted deleterious by CADD predictors with a score of 23. Its MAF was 8.5 10–4, 2 10–3 and 3% in African gnomADv4 controls, GME database and 119 Sudanese controls, respectively.

In F19 (see pedigree in Fig. 1), a rare variant, c.13757C > T (p.Thr4586Met), in FAT1 segregated at the homozygous state in all patients and was at the heterozygous state in one unaffected sib (IV-8). FAT1 gene encoded a protocadherin transmembrane protein involved in cell adhesion in a broad range of tissue, including neurons [67]. Biallelic loss-of-function in FAT1 have been associated with nephropathy [68] and microphtalmia [69]. Moreover, monoallelic missense variants of FAT1 have been associated with spinocerebellar ataxia [70]. The FAT1 missense variant chr4(hg19):g.187509756G > A (p.Thr4586Met), was rare in population databases, (gnomAD Maximal Allele Frequency = 0.0003659 (SAS); no homozygous individual; absent in the 238 Sudanese chromosome controls). This variant was predicted to be deleterious by both M-CAP and CADD predictors. The Bipoint-lodscore between this variant and the phenotype was 2.53 at θ = 0.00, supporting the involvement of FAT1. This variant is located in the extreme cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of the protein interacting with the Scribble protein, which regulates dendritic spine development in association with NOS1AP [71]. This C-ter region is well conserved and depleted of missense variation in the population, according to Metadome, supporting a constrained region [72] (Fig. S1).

Furthermore, the deletion of the last 3 residues (TEV) has been shown to prevent the interaction of Fat1 with Scribble [73]. This supports a crucial role of this short motif for partner interaction. Structural modelling of the C-terminal domain of FAT1 shows that the introduction of a methionine in the H-T-E-V codon motif altered the accessible molecular surface of the motif (Fig. S1).

In F12, WES was performed in 5 affected members including two patients from consanguineous marriages, leading to a very short list of candidate variants (Table S4). Intriguingly, among the four rare and deleterious candidate variants retained, two were in the same genomic interval of chromosome 2 (genes TTN, SLC38A11). From the filtered variants, another rare TTN missense was identified. Those three variants co-segregated in the family with a maximum multipoint lodscore of 2.75 at θ = 0.00 (Fig. 3). Since both genes have not been related to epilepsy until now and had a low Endeavour score, it could be hypothesized that a variant in a gene localized within the haplotype delineated by SLC38A11 and TTN and not detected by SNPs microarrays or WES was responsible for the phenotype. By using the patients’ WES data on chromosome 2, this genomic interval was restricted to the 1.8 Mb chr2(hg38):151,617,472–169,827,714 (chr2(hg19):152,473,986–170,684,224) region (See Fig. 3b), including CACNB4 encoding the β4 subunit of the calcium voltage-dependant channel and the cluster of SCN1A, SCN2A and SCN3A genes encoding the α1, α2 and α3 subunits of the sodium voltage-gated channel, respectively. In addition, we checked for variants shared by all individuals without any filtering, i.e. 18/135 variants in the chr2(hg19):152,473,986–170,684,224 region where the sodium channel genes were located. The rarest variant (SCN9A: 2–166,281,810-T-TA, hg38) was homozygous in 1634 individuals.in gnomADv4.

In F14 (Fig. 4), since no candidate SNPs were identified at the hemizygous or homozygous state in the 4 tested patients, 32 missense variants at the heterozygous state fulfilled our genetic criteria. The NM_006514.4:c.754C > T (p.Leu252Phe) variant in SCN10A, of which biallelic variants were associated with refractory epilepsy [7, 74, 75], was absent from gnomADv4 and predicted to be deleterious according to several in-silico predictors. The SCN10A gene was considered as the best candidate in the family by Endeavour algorithm (Table S1). Among the remaining candidates, c.1808G > A (p.Arg603His) variant (CADD score = 25) was localized in the coding sequence of the FBXO42 gene, which was reported in the top 3 of candidate genes for GGE by the epi25 [51] consortium. The c.712G > A (p.Glu238Lys) variant (CADD score = 29.6) in PIGG (Phosphaidylinositol Glycan Anchor Biosynthesis Class G Protein), which is associated with an AR syndrome associating intellectual disability, cerebellar atrophy and seizures [75]. The 3 previous variants were identified by Sanger in Patient (F14 V-11) DNA, which was not included in the WES study (Fig. 4): IV-10 and IV-11 asymptomatic parents were homozygous for PIGG and FBXO42, respectively.

In F7 (Fig. 2a), no variant at the hemizygous or homozygous state fulfilled the selection criteria. No frameshift variants surpassed the filters. Only 5 candidate missense variants have been selected by our algorithm, but none of them affected a gene previously related to epilepsy or seizures. In the 4 patients with GGE available in the family, the c.1441C > T (p.Pro481Ser) variant was identified in the DCHS1 gene, which encodes the Dachsous Cadherin related-1 protein, also called Protocadherin 16 (PCDH16). Biallelic and monoallelic alterations of DCHS1 are associated with Van-Maldergem syndrome and mitral valve prolapse, respectively [51, 76, 77]. DCHS1 has been involved in neurogenesis [76] and two other Protocadherins, 7 and 19, have already been implicated in GGE and in female-restricted epilepsy and mental retardation (EFMR) [78], respectively. PCDH16 is a receptor of FAT4, belonging to the same protein family as FAT1 implicated in F19, those 3 proteins being in narrow interaction (Fig. 1b). Moreover, Badouel and colleagues (2015) supported that Fat1 and Fat4 interacted in cis to regulate radial precursor development in mice [79] According to Endeavor prioritization, DCHS1 was the best candidate in the family F7, and was in the top 5 of candidate genes among all families (see Table S1). The 3 patients with JME shared 7 additional candidate variants, which were not present in the patient with GTCS (III.13). Interestingly, among the 7 corresponding genes, 4 were involved in dendrite development or functioning (ASTN2, CAMSAP1, GTF3C5 and R3HDM1). Astrotactin 2, encoded by ASTN2, regulates the surface expression of Astrotactin1 in glial-guided neuronal migration, and modulates synapse strength in post-migratory neurons by trafficking and degradation of surface proteins [80]. CAMSAP1 plays a key role in the neuronal polarity by regulating the number of microtubules [81]. In mice cortical neurons, silencing of Gtf3c5 mimicked the effects of chronic depolarization, inducing a dramatic increase of both dendritic length and branching [82]. Knockdown of R3hdm1 in mouse embryonic hippocampal neurons suppressed dendritic growth and branching [83]. While ASTN2, CAMSAP1 and GTF3C5 are located in the 9q33.1–9q34.3 chromosome segment, R3HDM1 is located on chromosome 2. The 3 patients with JME carried variants in these 4 genes and the DCHS1 variant (Fig. 2a). The ASTN2 Ser1150Gly missense variant is predicted to destabilize the Fibronectin type-III domain through the creation of a cavity (Fig. S2).

Search for additional rare variants in candidate gene

For each gene with at least one candidate variant, additional variants were searched for in WES of probands in the 15 remaining families. We used the same filter criteria as those applied in WES process. The segregation of each variant was established after determining the genotype of family members by Sanger sequencing and indicated on the pedigrees (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4). The retained variants were listed in Table 2.

No additional variants were identified in CACNA1A, FAT1, or SCN10A selected in F8, F19, and F14, respectively. In contrast, additional variants were identified in DCHS1 in family F18, F4, F14 and F16, and 1 in ASTN2 in family F8. Other DCHS1 variant in F18 segregated with the disease but not those in family F4, F14, and F16. In family F8, the c.2426G > A (pArg860Gln) variant in ASTN2 segregated in the two JME patients but not in the affected sib with GTCS, the same condition than in F7 (Fig. 2a, c). Structural modelling of ASTN2 p.Arg860Gln predicts the destabilization of the MACPF domain through the disruption of a curvature ionic bond with Glu1006. In the native 3D structure of Astrotactin 2, the MACPF domain interfaces the Fibronectin type III domain, which is mutated in F7 (Fig. S2).

A Bayesian model to test Oligogenic inheritance tested in family 7

To test the hypothesis of oligogenicity, a Bayesian model was applied to the genotypic data for family 7 (Fig. 2a). The empirical posterior marginal probability of carrying the 5 gene variants in DCHS1, ASTN2, CAMSAP1, GTF3C5 and R3HDM1 was calculated for all individuals identified in the family tree, whether genotyped or not (Fig. S3A). Several individuals, such as the two key individuals II6 or II10, who were not available for genetic testing, have very different carrier probability distribution (Fig. S3B).

Figure 2b shows the posterior distribution of the number of carriers for the five variants: 5–8 carriers are the most likely situations. The corresponding Fisher’s exact test p-values for the association between JME and being a carrier of the five variants (Table S5) have also been plotted at the top of Fig. 2b. Even in the (highly improbable) case of a family with 11 carriers of all 5 variants (probability 0.002%), the test remains significant. If we consider only the most common situation, with a number of carriers ranging from 5 to 8, the p-values range from 0.000810 to 0.004540.

Discussion

In order to identify susceptibility genes in complex diseases, studies on familial forms are complementary to those on large cohorts of sporadic cases. Large families with GGE are rare, explaining why the studies on familial forms are infrequent. We applied an integrative approach combining CNV detection and identification of candidate genes by WES in a cohort of 20 mutigenerational families from Sudan with clustering of patients. The Sudanese population is structured in tribes or closed communities, associating endogamy and founder effects. Moreover, the large sibships in rural areas of Sudan facilitate the identification of families with many affected members. We mainly selected families with consanguineous index cases in order to enrich this population in autosomal recessive GGE. However, our algorithm selected very few variants at the homozygous or compound heterozygous state (Supplementary Table S4). Indeed, such a variant was identified only in family F19 with an a priori autosomal recessive inheritance. In contrast, in the remaining families F7, F12 and F14, patients shared rare to ultra-rare variants at the heterozygous state. The penetrance of the disease estimated in these families was in the range of the penetrance of the Parkinson disease associated with the p.Gly2019Ser susceptibility variant in LRKK2 gene, which varied from ~ 24 to 33% in US Jewish, US non-Jewish or Italian Parkinson patients [84].

Our strategy used standard genetic filters and the Endeavour algorithm to functionally prioritize genes. Endeavour was based on machine learning techniques using different data sources (sequence data, expression data, functional annotations, protein–protein interaction networks, text mining data, regulation information and phenotypic information) and trained with the already known disease causing genes (Seed genes) [26].

In F19 family, the perfect segregation with GGE of the likely pathogenic biallelic FAT1 variant, c.13757C > T (p.Thr4586Met), with a lodscore of 2.53 (maximal theorical Lod score in F19) at θ = 0.00, highly suggested its role in the phenotype. Biallelic frameshift variants in FAT1 (600,976) were first identified in patients with a syndrome characterized by facial dysmorphism, colobomatous, microphthalmia, ptosis and syndactyly with or without nephropathy [69]. More recently, an association was reported between misense FAT1 variants at the compound heterozygous state in extracellular cadherin domains and pharmacosensitive focal epilepsy with or without febrile seizures [85]. The c.13757C > T (p.Thr4586Met) variant in family F19 is in the highly conserved C-terminal 4584-HTEV-STOP codon motif (up to Tetraodon), which interacts with the scribble key protein of the hippo pathway playing a role in the neurite outgrowth [67, 86, 87]. To our knowledge, no missense variant at the homozygous state has been reported in this C-terminal motif [88].

In F8, the MAF of the CACNA1A variant were high (3%) in the Sudanese controls, raising the question of its responsibility in the disease or of the relevance to increase the frequency threshold used (MAF < 5%). The study of familial forms could allow detecting rare/ultrarare (MAF < 1/10 000) as well as relatively frequent (MAF up to 5%) susceptibility variants, making a bridge between GWAS using markers with MAF > 5% and case-controls study by WES enable to detect only ultra-rare variants [89] Moreover, CACNA1A might be involved in GGE in association with at least a second non-detected variant on chromosome X, in accordance with the recessive X-linked inheritance expected by the observation of the pedigree.

In family F7, few candidate variants segregated at heterozygous state with GGE following a non-conventional transmission: they were always transmitted by an asymptomatic parent. F7 can be considered as a tribe with founder effects and deep endogamy. Several variants in different genes could have circulated in the tribe until they were transmitted together in few family members, who developed GGE. The segregation of the variants in family F7 highly supports this model, especially those closely located on chromosome 9 (Fig. 2a). Based on the visual reconstruction of haplotypes, since the 3 JME patients received the DCHS1 variant and the four in ASTN2, GTF3C5, CAMPAS1 and R3HDM1, 9/10 non-JME members (9 at-risk asymptomatic individuals and the patient III.13 with GTC), for whom it lacked at least one variant, did not develop JME (Fig. 2a). To test the hypothesis of oligogenism, which was highly supported in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis [90, 91] or in Holoprosencephaly [92], a Bayesian model was applied to the genotype data of family 7. Our analysis concludes that, even when accounting for unobserved genotypes, there exists a significant statistical association between JME and carrying all five variants, highly supporting the hypothesis of oligogenism (Fig. 2b).

It is interesting to note that in F8, since all 3 patients received the CACNA1A variant, ASTN2 variant was present only in the two patients with JME and not in the affected sib with GTCS (Fig. 2c). These data made ASTN2 the best susceptibility candidate variant for JME, added to the fact that ASTN2 is on the top 200 genes in the epi25 consortium study [51].

The functions of the genes implicated in this study were different, from channels to proteins involved in dendrite development. We identified variants in genes encoding transmembrane proteins with structural and signal transduction function, especially at synapses: DCHS1 encoding the Protocadherin 16 [93], FAT1 an atypical Cadherin and ADGRV1 an adhesion G protein-receptor [14]. In the recent study by Epi25 consortium on GGE [51], the most significant candidate gene intolerant to loss-of function variants was NLGN2 (MIM: 606,479), encoding neuroligin 2, a trans-synaptic adhesion molecule [94].

The relatively small size of our cohort can represent an obvious limitation of our study. This argument is common to the rare studies based on familial forms of complex diseases including GEE. In Sudan, epilepsy, even GGE, which is a relatively mild phenotype, remains a taboo, especially in rural areas, explaining why we could not get some samples in extended branches of few families. We expect that communication on advancement of our work will encourage family members to participate to future studies. Another limitation of our approach is that we only analyzed the untranslated, translated and flanking splicing regions of genes, missing variants localized in noncoding or in far regulatory sequences. Whole genome or long-read sequencing might be the appropriate technique to explore these regions, especially the CACNB4-UBR3 genomic interval for family F12 or X chromosome for family F8.

Conclusion

Our approach on familial forms of GGE is complementary to large-scale collaborative consortia studies of sporadic cases. Both strategies incriminated similar genes such as ASTN2. The fact, that this candidate gene was identified by two different strategies in different populations, is an argument in favor of its role as susceptibility variants in GGE. The identification of FAT1 as a likely susceptibility gene for GGE, points out with DCHS1 a new class of susceptibility genes involved in the DCHS1—FAT1/FAT4—Hippo signaling pathway. Finally, our study reinforces the hypothesis that GGE is genetically heterogeneous, with various modes of inheritance, even in a regionally restricted population. However, GGEs are mainly multifactorial, probably with oligogenic inheritance, as supported by the Bayesian algorithm that we developed in a family with JME. This algorithm will be helpful to test oligogenic inheritance in families with epilepsy or other common diseases. Since populations with founder effect and endogamy are appropriate to study autosomal recessive pathologies, they would be also adapted to decipher genetic components of complex diseases.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 4 Table S1: Endeavour prioritization of candidate variants

Additional file 5 Table S2: Oligogenic Bayesian model-sampling of 50 000 full genotypes

Additional file 6 Table S3: CNVs detection in the 20 families

Additional file 7 Table S4: WES data in F7, F12, F14, F18 and F19 families

Additional file 8 Table S5: Fisher exact test p-values depending on the number of carriers in the family

Author contributions

MD contributed to the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of most data. MSE referred the patients and clinically evaluated them. EAA, FAE, WAA, RM, SG, AA, MB, LM, SG and MAD contributed to the inclusion of patients and sample collection. JMDSA contributed to the interpretation of WES, 3D structural modelling and writing of the paper, TC to the interpretation of SNPs microarrays and JB(s), BK & BC to the bioinformatics analyses. SBal, EN& EAA contributed to the figures design. SBal, SB critically reviewed the manuscript. LE contributed to the design and collection of data, AE contributed to supervising and revising the manuscript. GN constructed statistical models. EL designed, supervised and obtained funding for the study. MD and EL wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by INSERM (France), IHU-A-ICM (France), the Sudanese Ministry of Higher Education and the Sudanese-French PHC Napata project.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was prospectively reviewed and approved by the national health research ethics committee, Federal ministry of health, Sudan (1–4–18).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was given by all participants.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was given by all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jean-Madeleine de Sainte Agathe, Mohamed S. Elmagzoub have equally contributed to the publication; Gregory Nuel and Ammar E. Ahmed have equally contributed to the publication.

References

- 1.Peljto AL, Barker-Cummings C, Vasoli VM, Leibson CL, Hauser WA, Buchhalter JR, Ottman R. Familial risk of epilepsy: a population-based study. Brain. 2014;137:795–805. 10.1093/brain/awt368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cossette P, Liu L, Brisebois K, Dong H, Lortie A, Vanasse M, Saint-Hilaire J-M, Carmant L, Verner A, Lu W-Y, Wang YT, Rouleau GA. Mutation of GABRA1 in an autosomal dominant form of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2002;31:184–9. 10.1038/ng885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki T, Delgado-Escueta AV, Aguan K, Alonso ME, Shi J, Hara Y, Nishida M, Numata T, Medina MT, Takeuchi T, Morita R, Bai D, Ganesh S, Sugimoto Y, Inazawa J, Bailey JN, Ochoa A, Jara-Prado A, Rasmussen A, Ramos-Peek J, Cordova S, Rubio-Donnadieu F, Inoue Y, Osawa M, Kaneko S, Oguni H, Mori Y, Yamakawa K. Mutations in EFHC1 cause juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2004;36:842–9. 10.1038/ng1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jara-Prado A, Martínez-Juárez IE, Ochoa A, González VM, Fernández-González-Aragón MDC, López-Ruiz M, Medina MT, Bailey JN, Delgado-Escueta AV, Alonso ME. Novel Myoclonin1/EFHC1 mutations in Mexican patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Seizure. 2012;21:550–4. 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subaran RL, Conte JM, Stewart WCL, Greenberg DA. Pathogenic EFHC1 mutations are tolerated in healthy individuals dependent on reported ancestry. Epilepsia. 2015;56:188–94. 10.1111/epi.12864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.May P, Girard S, Harrer M, Bobbili DR, Schubert J, Wolking S, Becker F, Lachance-Touchette P, Meloche C, Gravel M, Niturad CE, Knaus J, De Kovel C, Toliat M, Polvi A, Iacomino M, Guerrero-López R, Baulac S, Marini C, Thiele H, Altmüller J, Jabbari K, Ruppert AK, Jurkowski W, Lal D, Rusconi R, Cestèle S, Terragni B, Coombs ID, Reid CA, Striano P, Caglayan H, Siren A, Everett K, Møller RS, Hjalgrim H, Muhle H, Helbig I, Kunz WS, Weber YG, Weckhuysen S, De Jonghe P, Sisodiya SM, Nabbout R, Franceschetti S, Coppola A, Vari MS, Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité D, Baykan B, Ozbek U, Bebek N, Klein KM, Rosenow F, Nguyen DK, Dubeau F, Carmant L, Lortie A, Desbiens R, Clément JF, Cieuta-Walti C, Sills GJ, Auce P, Francis B, Johnson MR, Marson AG, Berghuis B, Sander JW, Avbersek A, McCormack M, Cavalleri GL, Delanty N, Depondt C, Krenn M, Zimprich F, Peter S, Nikanorova M, Kraaij R, van Rooij J, Balling R, Ikram MA, Uitterlinden AG, Avanzini G, Schorge S, Petrou S, Mantegazza M, Sander T, LeGuern E, Serratosa JM, Koeleman BPC, Palotie A, Lehesjoki AE, Nothnagel M, Nürnberg P, Maljevic S, Zara F, Cossette P, Krause R, Lerche H, De Jonghe P, Arfan Ikram M, Ferlazzo E, di Bonaventura C, La Neve A, Tinuper P, Bisulli F, Vignoli A, Capovilla G, Crichiutti G, Gambardella A, Belcastro V, Bianchi A, Yalçın D, Dizdarer G, Arslan K, Yapıcı Z, Kuşcu D, Leu C, Heggeli K, Willis J, Langley SR, Jorgensen A, Srivastava P, Rau S, Hengsbach C, Sonsma ACM. Rare coding variants in genes encoding GABA A receptors in genetic generalised epilepsies: an exome-based case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:699–708. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernández-Marmiesse A, Roca I, Díaz-Flores F, Cantarín V, Pérez-Poyato MS, Fontalba A, Laranjeira F, Quintans S, Moldovan O, Felgueroso B, Rodríguez-Pedreira M, Simón R, Camacho A, Quijada P, Ibanez-Mico S, Domingno MR, Benito C, Calvo R, Pérez-Cejas A, Carrasco ML, Ramos F, Couce ML, Ruiz-Falcó ML, Gutierrez-Solana L, Martínez-Atienza M. Rare variants in 48 genes account for 42% of cases of epilepsy with or without neurodevelopmental delay in 246 pediatric patients. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1135. 10.3389/fnins.2019.01135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leu C, Stevelink R, Smith AW, Goleva SB, Kanai M, Ferguson L, Campbell C, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Sisodiya SM, Cavalleri GL, Koeleman BPC, Lerche H, Jehi L, Davis LK, Najm IM, Palotie A, Daly MJ, Busch RM, Epi25 Consortium, Lal D. Polygenic burden in focal and generalized epilepsies. Brain. 2019;142:3473–81. 10.1093/brain/awz292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng YCA, Howrigan DP, Abbott LE, Tashman K, Cerrato F, Singh T, Heyne H, Byrnes A, Churchhouse C, Watts N, Solomonson M, Lal D, Heinzen EL, Dhindsa RS, Stanley KE, Cavalleri GL, Hakonarson H, Helbig I, Krause R, May P, Weckhuysen S, Petrovski S, Kamalakaran S, Sisodiya SM, Cossette P, Cotsapas C, de Jonghe P, Dixon-Salazar T, Guerrini R, Kwan P, Marson AG, Stewart R, Depondt C, Dlugos DJ, Scheffer IE, Striano P, Freyer C, McKenna K, Regan BM, Bellows ST, Leu C, Bennett CA, Johns EMC, Macdonald A, Shilling H, Burgess R, Weckhuysen D, Bahlo M, O’Brien TJ, Todaro M, Stamberger H, Andrade DM, Sadoway TR, Mo K, Krestel H, Gallati S, Papacostas SS, Kousiappa I, Tanteles GA, Štěrbová K, Vlčková M, Sedláčková L, Laššuthová P, Klein KM, Rosenow F, Reif PS, Knake S, Kunz WS, Zsurka G, Elger CE, Bauer J, Rademacher M, Pendziwiat M, Muhle H, Rademacher A, van Baalen A, von Spiczak S, Stephani U, Afawi Z, Korczyn AD, Kanaan M, Canavati C, Kurlemann G, Müller-Schlüter K, Kluger G, Häusler M, Blatt I, Lemke JR, Krey I, Weber YG, Wolking S, Becker F, Hengsbach C, Rau S, Maisch AF, Steinhoff BJ, Schulze-Bonhage A, Schubert-Bast S, Schreiber H, Borggräfe I, Schankin CJ, Mayer T, Korinthenberg R, Brockmann K, Dennig D, Madeleyn R, Kälviäinen R, Auvinen P, Saarela A, Linnankivi T, Lehesjoki AE, Rees MI, Chung SK, Pickrell WO, Powell R, Schneider N, Balestrini S, Zagaglia S, Braatz V, Johnson MR, Auce P, Sills GJ, Baum LW, Sham PC, Cherny SS, Lui CHT, Barišić N, Delanty N, Doherty CP, Shukralla A, McCormack M, El-Naggar H, Canafoglia L, Franceschetti S, Castellotti B, Granata T, Zara F, Iacomino M, Madia F, Vari MS, Mancardi MM, Salpietro V, Bisulli F, Tinuper P, Licchetta L, Pippucci T, Stipa C, Minardi R, Gambardella A, Labate A, Annesi G, Manna L, Gagliardi M, Parrini E, Mei D, Vetro A, Bianchini C, Montomoli M, Doccini V, Marini C, Suzuki T, Inoue Y, Yamakawa K, Tumiene B, Sadleir LG, King C, Mountier E, Caglayan SH, Arslan M, Yapıcı Z, Yis U, Topaloglu P, Kara B, Turkdogan D, Gundogdu-Eken A, Bebek N, Uğur-İşeri S, Baykan B, Salman B, Haryanyan G, Yücesan E, Kesim Y, Özkara Ç, Poduri A, Shiedley BR, Shain C, Buono RJ, Ferraro TN, Sperling MR, Lo W, Privitera M, French JA, Schachter S, Kuzniecky RI, Devinsky O, Hegde M, Khankhanian P, Helbig KL, Ellis CA, Spalletta G, Piras F, Piras F, Gili T, Ciullo V, Reif A, McQuillin A, Bass N, McIntosh A, Blackwood D, Johnstone M, Palotie A, Pato MT, Pato CN, Bromet EJ, Carvalho CB, Achtyes ED, Azevedo MH, Kotov R, Lehrer DS, Malaspina D, Marder SR, Medeiros H, Morley CP, Perkins DO, Sobell JL, Buckley PF, Macciardi F, Rapaport MH, Knowles JA, Fanous AH, McCarroll SA, Gupta N, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Lander ES, Lowenstein DH, Goldstein DB, Lerche H, Berkovic SF, Neale BM. Ultra-rare genetic variation in the epilepsies: a whole-exome sequencing study of 17,606 individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105:267–82. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koko M, Motelow JE, Stanley KE, Bobbili DR, Dhindsa RS, May P. Association of ultra‐rare coding variants with genetic generalized epilepsy: a case–control whole exome sequencing study. Epilepsia. 2022;63(3):723–735. 10.1111/epi.17166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheffer IE, Nabbout R. SCN1A-related phenotypes: epilepsy and beyond. Epilepsia. 2019;60(Suppl 3):S17–24. 10.1111/epi.16386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannesen KM, Gardella E, Linnankivi T, Courage C, de Saint Martin A, Lehesjoki A-E, Mignot C, Afenjar A, Lesca G, Abi-Warde MT, Chelly J, Piton A, 2nd Merritt JL, Rodan LH, Tan W-H, Bird LM, Nespeca M, Gleeson JG, Yoo Y, Choi M, Chae J-H, Czapansky-Beilman D, Reichert SC, Pendziwiat M, Verhoeven JS, Schelhaas HJ, Devinsky O, Christensen J, Specchio N, Trivisano M, Weber YG, Nava C, Keren B, Doummar D, Schaefer E, Hopkins S, Dubbs H, Shaw JE, Pisani L, Myers CT, Tang S, Tang S, Pal DK, Millichap JJ, Carvill GL, Helbig KL, Mecarelli O, Striano P, Helbig I, Rubboli G, Mefford HC, Møller RS. Defining the phenotypic spectrum of SLC6A1 mutations. Epilepsia 2018;59:389–402. 10.1111/epi.13986.

- 13.Bundalian L, Su Y-Y, Chen S, Velluva A, Kirstein AS, Garten A, Biskup S, Battke F, Lal D, Heyne HO, Platzer K, Lin C-C, Lemke JR, Le Duc D, Epi25 Collaborative, The role of rare genetic variants enrichment in epilepsies of presumed genetic etiology. MedRxiv (2023). 10.1101/2023.01.17.23284702.

- 14.Dahawi M, Elmagzoub MS, Ahmed EA, Baldassari S, Achaz G, Elmugadam FA, Abdelgadir WA, Baulac S, Buratti J, Abdalla O, Gamil S, Alzubeir M, Abubaker R, Noé E, Elsayed L, Ahmed AE, Leguern E. Involvement of ADGRV1 gene in familial forms of genetic generalized epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2021;12:1–10. 10.3389/fneur.2021.738272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers KA, Nasioulas S, Boys A, McMahon JM, Slater H, Lockhart P, du Sart D, Scheffer IE. ADGRV1 is implicated in myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2018;59:381–8. 10.1111/epi.13980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skradski SL, Clark AM, Jiang H, White HS, Fu YH, Ptáček LJ. A novel gene causing a mendelian audiogenic mouse epilepsy. Neuron. 2001;31:537–44. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00397-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horimoto ARVR, Onodera MT, Otto PA. PENCALC: a program for penetrance estimation in autosomal dominant diseases. Genet Mol Biol. 2010;33:455–9. 10.1590/S1415-47572010005000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereanu W, Larsen EC, Das I, Estévez MA, Sarkar AA, Spring-Pearson S, Kollu R, Basu SN, Banerjee-Basu A. AutDB: a platform to decode the genetic architecture of autism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1049–54. 10.1093/nar/gkx1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Jaganathan K, Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou S, McRae JF, Darbandi SF, Knowles D, Li YI, Kosmicki JA, Arbelaez J, Cui W, Schwartz GB, Chow ED, Kanterakis E, Gao H, Kia A, Batzoglou S, Sanders SJ, Farh KK-H. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell. 2019;176:535–48. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, Collins RL, Laricchia KM, Ganna A, Birnbaum DP, Gauthier LD, Brand H, Solomonson M, Watts NA, Rhodes D, Singer-Berk M, England EM, Seaby EG, Kosmicki JA, Walters RK, Tashman K, Farjoun Y, Banks E, Poterba T, Wang A, Seed C, Whiffin N, Chong JX, Samocha KE, Pierce-Hoffman E, Zappala Z, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Minikel EV, Weisburd B, Lek M, Ware JS, Vittal C, Armean IM, Bergelson L, Cibulskis K, Connolly KM, Covarrubias M, Donnelly S, Ferriera S, Gabriel S, Gentry J, Gupta N, Jeandet T, Kaplan D, Llanwarne C, Munshi R, Novod S, Petrillo N, Roazen D, Ruano-Rubio V, Saltzman A, Schleicher M, Soto J, Tibbetts K, Tolonen C, Wade G, Talkowski ME, Neale BM, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–43. 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott EM, Halees A, Itan Y, Spencer EG, He Y, Azab MA, Gabriel SB, Belkadi A, Boisson B, Abel L, Clark AG, Alkuraya FS, Casanova J-L, Gleeson JG. Characterization of greater middle eastern genetic variation for enhanced disease gene discovery. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1071–6. 10.1038/ng.3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings BB, Karczewski KJ, Kosmicki JA, Seaby EG, Watts NA, Singer-Berk M, Mudge JM, Karjalainen J, Satterstrom FK, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Poterba T, Seed C, Solomonson M, Alföldi J, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG. Transcript expression-aware annotation improves rare variant interpretation. Nature. 2020;581:452–8. 10.1038/s41586-020-2329-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D886–94. 10.1093/nar/gky1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jagadeesh KA, Wenger AM, Berger MJ, Guturu H, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Bernstein JA, Bejerano G. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1581–6. 10.1038/ng.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, Middha S, McDonnell SK, Baheti S, Musolf A, Li Q, Holzinger E, Karyadi D, Cannon-Albright LA, Teerlink CC, Stanford JL, Isaacs WB, Xu J, Cooney KA, Lange EM, Schleutker J, Carpten JD, Powell IJ, Cussenot O, Cancel-Tassin G, Giles GG, MacInnis RJ, Maier C, Hsieh CL, Wiklund F, Catalona WJ, Foulkes WD, Mandal D, Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Bustamante CD, Schaid DJ, Hastie T, Ostrander EA, Bailey-Wilson JE, Radivojac P, Thibodeau SN, Whittemore AS, Sieh W. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:877–85. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tranchevent LC, Ardeshirdavani A, ElShal S, Alcaide D, Aerts J, Auboeuf D, Moreau Y. Candidate gene prioritization with endeavour. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W117–21. 10.1093/nar/gkw365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landoulsi Z, Laatar F, Noé E, Mrabet S, Ben Djebara M, Achaz G, Nava C, Baulac S, Kacem I, Gargouri-Berrechid A, Gouider R, Leguern E. Clinical and genetic study of Tunisian families with genetic generalized epilepsy: contribution of CACNA1H and MAST4 genes. Neurogenetics. 2018;19:165–78. 10.1007/s10048-018-0550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh B, Monteil A, Bidaud I, Sugimoto Y, Suzuki T, Hamano S, Oguni H, Osawa M, Alonso ME, Delgado-Escueta AV, Inoue Y, Yasui-Furukori N, Kaneko S, Lory P, Yamakawa K. Mutational analysis of CACNA1G in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:524–5. 10.1002/humu.9491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Lu J, Pan H, Zhang Y, Wu H, Xu K, Liu X, Jiang Y, Bao X, Yao Z, Ding K, Lo WHY, Qiang B, Chan P, Shen Y, Wu X. Association between genetic variation of CACNA1H and childhood absence epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:239–43. 10.1002/ana.10607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heron SE, Khosravani H, Varela D, Bladen C, Williams TC, Newman MR, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Mulley JC, Zamponi GW. Extended spectrum of idiopathic generalized epilepsies associated with CACNA1H functional variants. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:560–8. 10.1002/ana.21169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Escayg A, De Waard M, Lee DD, Bichet D, Wolf P, Mayer T, Johnston J, Baloh R, Sander T, Meisler MH. Coding and noncoding variation of the human calcium-channel β4-subunit gene CACNB4 in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy and episodic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1531–9. 10.1086/302909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapoor A, Satishchandra P, Ratnapriya R, Reddy R, Kadandale J, Shankar SK, Anand A. An idiopathic epilepsy syndrome linked to 3q13.3-q21 and missense mutations in the extracellular calcium sensing receptor gene. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:158–67. 10.1002/ana.21428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Consortium E, Steffens M, Leu C, Ruppert A-K, Zara F, Striano P, Robbiano A, Capovilla G, Tinuper P, Gambardella A, Bianchi A, La Neve A, Crichiutti G, de Kovel CGF, Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité D, de Haan G-J, Lindhout D, Gaus V, Schmitz B, Janz D, Weber YG, Becker F, Lerche H, Steinhoff BJ, Kleefuß-Lie AA, Kunz WS, Surges R, Elger CE, Muhle H, von Spiczak S, Ostertag P, Helbig I, Stephani U, Møller RS, Hjalgrim H, Dibbens LM, Bellows S, Oliver K, Mullen S, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Everett KV, Gardiner MR, Marini C, Guerrini R, Lehesjoki A-E, Siren A, Guipponi M, Malafosse A, Thomas P, Nabbout R, Baulac S, Leguern E, Guerrero R, Serratosa JM, Reif PS, Rosenow F, Mörzinger M, Feucht M, Zimprich F, Kapser C, Schankin CJ, Suls A, Smets K, De Jonghe P, Jordanova A, Caglayan H, Yapici Z, Yalcin DA, Baykan B, Bebek N, Ozbek U, Gieger C, Wichmann H-E, Balschun T, Ellinghaus D, Franke A, Meesters C, Becker T, Wienker TF, Hempelmann A, Schulz H, Rüschendorf F, Leber M, Pauck SM, Trucks H, Toliat MR, Nürnberg P, Avanzini G, Koeleman BPC, Sander T. Genome-wide association analysis of genetic generalized epilepsies implicates susceptibility loci at 1q43, 2p16.1, 2q22.3 and 17q21.32. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5359–72. 10.1093/hmg/dds373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anney RJL, Avbersek A, Balding D, Baum L, Becker F, Berkovic SF, Bradfi JP, Brody LC, Buono RJ, Catarino CB, Cavalleri GL, Cherny SS, Chinthapalli K, Coffey AJ, Compston A, Cossette P, De Haan GJ, De Jonghe P, De Kovel CGF, Delanty N, Depondt C, Dlugos DJ, Doherty CP, Elger CE, Ferraro TN, Feucht M, Franke A, French J, Gaus V, Goldstein DB, Gui H, Guo Y, Hakonarson H, Hallmann K, Heinzen EL, Helbig I, Hjalgrim H, Jackson M, Jamnadas-Khoda J, Janz D, Johnson MR, Kalviainen R, Kantanen AM, Kasperaviciute D, Trenite DKN, Koeleman BPC, Kunz WS, Kwan P, Lau YL, Lehesjoki AE, Lerche H, Leu C, Lieb W, Lindhout D, Lo W, Lowenstein DH, Malovini A, Marson AG, McCormack M, Mills JL, Moerzinger M, Moller RS, Molloy AM, Muhle H, Newton M, Ng PW, Nothen MM, Nurnberg P, OBrien TJ, Oliver KL, Palotie A, Pangilinan F, Pernhorst K, Petrovski S, Privitera M, Radtke R, Reif PS, Rosenow F, Ruppert AK, Sander T, Scattergood T, Schachter S, Schankin C, Scheffer IE, Schmitz B, Schoch S, Sham PC, Sisodiya S, Smith DF, Smith PE, Speed D, Sperling MR, Steffens M, Stephani U, Striano P, Stroink H, Surges R, Tan KM, Thomas GN, Todaro M, Tostevin A, Tozzi R, Trucks H, Visscher F, von Spiczak S, Walley NM, Weber YG, Wei Z, Whelan C, Yang W, Zara F, Zimprich F. Genetic determinants of common epilepsies: A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:893–903. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urak L, Feucht M, Fathi N, Hornik K, Fuchs K. A GABRB3 promoter haplotype associated with childhood absence epilepsy impairs transcriptional activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2533–41. 10.1093/hmg/ddl174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka M, Olsen RW, Medina MT, Schwartz E, Alonso ME, Duron RM, Castro-Ortega R, Martinez-Juarez IE, Pascual-Castroviejo I, Machado-Salas J, Silva R, Bailey JN, Bai D, Ochoa A, Jara-Prado A, Pineda G, Macdonald RL, Delgado-Escueta AV. Hyperglycosylation and reduced GABA currents of mutated GABRB3 polypeptide in remitting childhood absence epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1249–61. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace RH, Marini C, Petrou S, Harkin LA, Bowser DN, Panchal RG, Williams DA, Sutherland GR, Mulley JC, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF. Mutant GABA(A) receptor gamma2-subunit in childhood absence epilepsy and febrile seizures. Nat Genet. 2001;28:49–52. 10.1038/ng0501-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dibbens LM, Feng H-J, Richards MC, Harkin LA, Hodgson BL, Scott D, Jenkins M, Petrou S, Sutherland GR, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Macdonald RL, Mulley JC. GABRD encoding a protein for extra- or peri-synaptic GABAA receptors is a susceptibility locus for generalized epilepsies. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1315–9. 10.1093/hmg/ddh146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mas C, Taske N, Deutsch S, Guipponi M, Thomas P, Covanis A, Friis M, Kjeldsen MJ, Pizzolato GP, Villemure J-G, Buresi C, Rees M, Malafosse A, Gardiner M, Antonarakis SE, Meda P. Association of the connexin36 gene with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e93. 10.1136/jmg.2003.017954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arsov T, Mullen SA, Rogers S, Phillips AM, Lawrence KM, Damiano JA, Goldberg-Stern H, Afawi Z, Kivity S, Trager C, Petrou S, Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE. Glucose transporter 1 deficiency in the idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:807–15. 10.1002/ana.23702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dejanovic B, Lal D, Catarino CB, Arjune S, Belaidi AA, Trucks H, Vollmar C, Surges R, Kunz WS, Motameny S, Altmüller J, Köhler A, Neubauer BA, Consortium E, Nürnberg P, Noachtar S, Schwarz G, Sander T. Exonic microdeletions of the gephyrin gene impair GABAergic synaptic inhibition in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;67:88–96. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sander T, Hildmann T, Kretz R, Fürst R, Sailer U, Bauer G, Schmitz B, Beck-Mannagetta G, Wienker TF, Janz D. Allelic association of juvenile absence epilepsy with a GluR5 kainate receptor gene (GRIK1) polymorphism. Am J Med Genet. 1997;74:416–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore T, Hecquet S, McLellann A, Ville D, Grid D, Picard F, Moulard B, Asherson P, Makoff AJ, McCormick D, Nashef L, Froguel P, Arzimanoglou A, LeGuern E, Bailleul B. Polymorphism analysis of JRK/JH8, the human homologue of mouse jerky, and description of a rare mutation in a case of CAE evolving to JME. Epilepsy Res. 2001;46:157–67. 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neubauer BA, Waldegger S, Heinzinger J, Hahn A, Kurlemann G, Fiedler B, Eberhard F, Muhle H, Stephani U, Garkisch S, Eeg-Olofsson O, Müller U, Sander T. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 mutations contribute to different idiopathic epilepsy syndromes. Neurology. 2008;71:177–83. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000317090.92185.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenberg DA, Cayanis E, Strug L, Marathe S, Durner M, Pal DK, Alvin GB, Klotz I, Dicker E, Shinnar S, Bromfield EB, Resor S, Cohen J, Moshe SL, Harden C, Kang H. Malic enzyme 2 may underlie susceptibility to adolescent-onset idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:139–46. 10.1086/426735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang P, Sang T, Zhang F, Ji T, Huang Q, Xie H, Du R, Cai B, Zhao H, Wang J, Wu Y, Wu H, Xu K, Liu X, Chan P, Wu X. NIPA2 located in 15q11.2 is mutated in patients with childhood absence epilepsy. Hum Genet. 2012;131:1217–24. 10.1007/s00439-012-1149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lal D, Ruppert A-K, Trucks H, Schulz H, de Kovel CG, Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité D, Sonsma ACM, Koeleman BP, Lindhout D, Weber YG, Lerche H, Kapser C, Schankin CJ, Kunz WS, Surges R, Elger CE, Gaus V, Schmitz B, Helbig I, Muhle H, Stephani U, Klein KM, Rosenow F, Neubauer BA, Reinthaler EM, Zimprich F, Feucht M, Møller RS, Hjalgrim H, de Jonghe P, Suls A, Lieb W, Franke A, Strauch K, Gieger C, Schurmann C, Schminke U, Nürnberg P, Sander T. Burden analysis of rare microdeletions suggests a strong impact of neurodevelopmental genes in genetic generalised epilepsies. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005226. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kahle KT, Merner ND, Friedel P, Silayeva L, Liang B, Khanna A, Shang Y, Lachance-Touchette P, Bourassa C, Levert A, Dion PA, Walcott B, Spiegelman D, Dionne-Laporte A, Hodgkinson A, Awadalla P, Nikbakht H, Majewski J, Cossette P, Deeb TZ, Moss SJ, Medina I, Rouleau GA. Genetically encoded impairment of neuronal KCC2 cotransporter function in human idiopathic generalized epilepsy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:766–74. 10.15252/embr.201438840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.I.L.A.E.C. on C.Epilepsies.E. address: Epilepsy-austin@unimelb.edu.au, Genetic determinants of common epilepsies: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:893–903. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Allen AS, Bellows ST, Berkovic SF, Bridgers J, Burgess R, Cavalleri G, Chung SK, Cossette P, Delanty N, Dlugos D, Epstein MP. Ultra-rare genetic variation in common epilepsies: a case-control sequencing study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:135–43. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Epi25 Collaborative. Electronic address: jm4279@cumc.columbia.edu, Epi25 Collaborative, Sub-genic intolerance, ClinVar, and the epilepsies: a whole-exome sequencing study of 29,165 individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:2024. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Functional Inactivation of a Fraction of Excitatory Synapses in Mice Deficient for the Active Zone Protein Bassoon role in the regulated neurotransmitter release from a subset of glutamatergic synapses, n.d.

- 53.Toth M, Grimsby J, Buzsaki G, Donovan GP. Epileptic seizures caused by inactivation of a novel gene, jerky, related to centromere binding protein-B in transgenic mice. Nat Genet. 1995;11:71–5. 10.1038/ng0995-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beyer B, Deleuze C, Letts VA, Mahaffey CL, Boumil RM, Lew TA, Huguenard JR, Frankel WN. Absence seizures in C3H/HeJ and knockout mice caused by mutation of the AMPA receptor subunit Gria4. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1738–49. 10.1093/hmg/ddn064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Douaud M, Feve K, Pituello F, Gourichon D, Boitard S, Leguern E, Coquerelle G, Vieaud A, Batini C, Naquet R, Vignal A, Tixier-Boichard M, Pitel F. Epilepsy caused by an abnormal alternative splicing with dosage effect of the SV2A gene in a chicken model. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26932. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venkatesan K, Alix P, Marquet A, Doupagne M, Niespodziany I, Rogister B, Seutin V. Altered balance between excitatory and inhibitory inputs onto CA1 pyramidal neurons from SV2A-deficient but not SV2B-deficient mice. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:2317–27. 10.1002/jnr.23111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balding DJ, Bishop M, Cannings C, editors. Handbook of statistical genetics. Hoboken: Wiley; 2007. 10.1002/9780470061619. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koller D, Friedman N. Probabilistic graphical models: principles and techniques—adaptive computation and machine learning. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baek M, DiMaio F, Anishchenko I, Dauparas J, Ovchinnikov S, Lee GR, Wang J, Cong Q, Kinch LN, Schaeffer RD, Millán C, Park H, Adams C, Glassman CR, DeGiovanni A, Pereira JH, Rodrigues AV, van Dijk AA, Ebrecht AC, Opperman DJ, Sagmeister T, Buhlheller C, Pavkov-Keller T, Rathinaswamy MK, Dalwadi U, Yip CK, Burke JE, Garcia KC, Grishin NV, Adams PD, Read RJ, Baker D. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science. 2021;373:871–6. 10.1126/science.abj8754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ittisoponpisan S, Islam SA, Khanna T, Alhuzimi E, David A, Sternberg MJE. Can predicted protein 3D structures provide reliable insights into whether missense variants are disease associated? J Mol Biol. 2019;431:2197–212. 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ni T, Harlos K, Gilbert R. Structure of astrotactin-2: a conserved vertebrate-specific and perforin-like membrane protein involved in neuronal development. Open Biol. 2016. 10.1098/rsob.160053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burley SK, Bhikadiya C, Bi C, Bittrich S, Chen L, Crichlow GV, Christie CH, Dalenberg K, Di Costanzo L, Duarte JM, Dutta S, Feng Z, Ganesan S, Goodsell DS, Ghosh S, Green RK, Guranović V, Guzenko D, Hudson BP, Lawson CL, Liang Y, Lowe R, Namkoong H, Peisach E, Persikova I, Randle C, Rose A, Rose Y, Sali A, Segura J, Sekharan M, Shao C, Tao Y-P, Voigt M, Westbrook JD, Young JY, Zardecki C, Zhuravleva M. RCSB Protein Data Bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D437–51. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Montanucci L, Lewis-Smith D, Collins RL, Niestroj L-M, Parthasarathy S, Xian J, Ganesan S, Macnee M, Brünger T, Thomas RH, Talkowski M, Epi25 Collaborative, Helbig I, Leu C, Lal D. Genome-wide identification and phenotypic characterization of seizure-associated copy number variations in 741,075 individuals. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4392. 10.1038/s41467-023-39539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Micheal S, Ayub H, Zafar SN, Bakker B, Ali M, Akhtar F, Islam F, Khan MI, Qamar R, den Hollander AI. Identification of novel CYP1B 1 gene mutations in patients with primary congenital and primary open-angle glaucoma. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43:31–9. 10.1111/ceo.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee CG, Lee J, Lee M. Multi-gene panel testing in Korean patients with common genetic generalized epilepsy syndromes. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199321. 10.1371/journal.pone.0199321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim TY, Maki T, Zhou Y, Sakai K, Mizuno Y, Ishikawa A, Tanaka R, Niimi K, Li W, Nagano N, Takahashi E. Absence-like seizures and their pharmacological profile in tottering-6j mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:148–53. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahmed AF, de Bock CE, Sontag E, Hondermarck H, Lincz LF, Thorne RF. FAT1 cadherin controls neuritogenesis during NTera2 cell differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;514:625–31. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gee HY, Sadowski CE, Aggarwal PK, Porath JD, Yakulov TA, Schueler M, Lovric S, Ashraf S, Braun DA, Halbritter J, Fang H, Airik R, Vega-Warner V, Jee Cho K, Chan TA, Morris LGT, Ffrench-Constant C, Allen N, McNeill H, Büscher R, Kyrieleis H, Wallot M, Gaspert A, Kistler T, Milford DV, Saleem MA, Keng WT, Alexander SI, Valentini RP, Licht C, Teh JC, Bogdanovic R, Koziell A, Bierzynska A, Soliman NA, Otto EA, Lifton RP, Holzman LB, Sibinga NES, Walz G, Tufro A, Hildebrandt F. FAT1 mutations cause a glomerulotubular nephropathy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1. 10.1038/ncomms10822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lahrouchi N, George A, Ratbi I, Schneider R, Elalaoui SC, Moosa S, Bharti S, Sharma R, Abu-Asab M, Onojafe F, Adadi N, Lodder EM, Laarabi F-Z, Lamsyah Y, Elorch H, Chebbar I, Postma AV, Lougaris V, Plebani A, Altmueller J, Kyrieleis H, Meiner V, McNeill H, Bharti K, Lyonnet S, Wollnik B, Henrion-Caude A, Berraho A, Hildebrandt F, Bezzina CR, Brooks BP, Sefiani A. Homozygous frameshift mutations in FAT1 cause a syndrome characterized by colobomatous-microphthalmia, ptosis, nephropathy and syndactyly. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1180. 10.1038/s41467-019-08547-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nibbeling EAR, Duarri A, Verschuuren-Bemelmans CC, Fokkens MR, Karjalainen JM, Smeets CJLM, de Boer-Bergsma JJ, van der Vries G, Dooijes D, Bampi GB, van Diemen C, Brunt E, Ippel E, Kremer B, Vlak M, Adir N, Wijmenga C, van de Warrenburg BPC, Franke L, Sinke RJ, Verbeek DS. Exome sequencing and network analysis identifies shared mechanisms underlying spinocerebellar ataxia. Brain. 2017;140:2860–78. 10.1093/brain/awx251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Richier L, Williton K, Clattenburg L, Colwill K, O’Brien M, Tsang C, Kolar A, Zinck N, Metalnikov P, Trimble WS, Krueger SR, Pawson T, Fawcett JP. NOS1AP associates with Scribble and regulates dendritic spine development. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4796–805. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3726-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wiel L, Baakman C, Gilissen D, Veltman JA, Vriend G, Gilissen C. MetaDome: pathogenicity analysis of genetic variants through aggregation of homologous human protein domains. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:1030–8. 10.1002/humu.23798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Skouloudaki K, Puetz M, Simons M, Courbard J-R, Boehlke C, Hartleben B, Engel C, Moeller MJ, Englert C, Bollig F, Schäfer T, Ramachandran H, Mlodzik M, Huber TB, Kuehn EW, Kim E, Kramer-Zucker A, Walz G. Scribble participates in Hippo signaling and is required for normal zebrafish pronephros development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8579–84. 10.1073/pnas.0811691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kambouris M, Thevenon J, Soldatos A, Cox A, Stephen J, Ben-Omran T, Al-Sarraj Y, Boulos H, Bone W, Mullikin JC, Masurel-Paulet A, St-Onge J, Dufford Y, Chantegret C, Thauvin-Robinet C, Al-Alami J, Faivre L, Riviere JB, Gahl WA, Bassuk AG, Malicdan MCV, El-Shanti H. Biallelic SCN10A mutations in neuromuscular disease and epileptic encephalopathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4:26–35. 10.1002/acn3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Makrythanasis P, Kato M, Zaki MS, Saitsu H, Nakamura K, Santoni FA, Miyatake S, Nakashima M, Issa MY, Guipponi M, Letourneau A, Logan CV, Roberts N, Parry DA, Johnson CA, Matsumoto N, Hamamy H, Sheridan E, Kinoshita T, Antonarakis SE, Murakami Y. Pathogenic variants in PIGG cause intellectual disability with seizures and hypotonia. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:615–26. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cappello S, Gray MJ, Badouel C, Lange S, Einsiedler M, Srour M, Chitayat D, Hamdan FF, Jenkins ZA, Morgan T, Preitner N, Uster T, Thomas J, Shannon P, Morrison V, Di Donato N, Van Maldergem L, Neuhann T, Newbury-Ecob R, Swinkells M, Terhal P, Wilson LC, Zwijnenburg PJG, Sutherland-Smith AJ, Black MA, Markie D, Michaud JL, Simpson MA, Mansour S, McNeill H, Götz M, Robertson SP. Mutations in genes encoding the cadherin receptor-ligand pair DCHS1 and FAT4 disrupt cerebral cortical development. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1300–8. 10.1038/ng.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]