Abstract

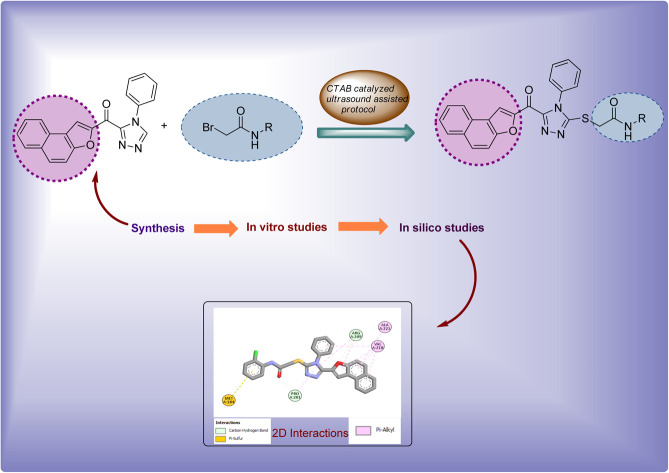

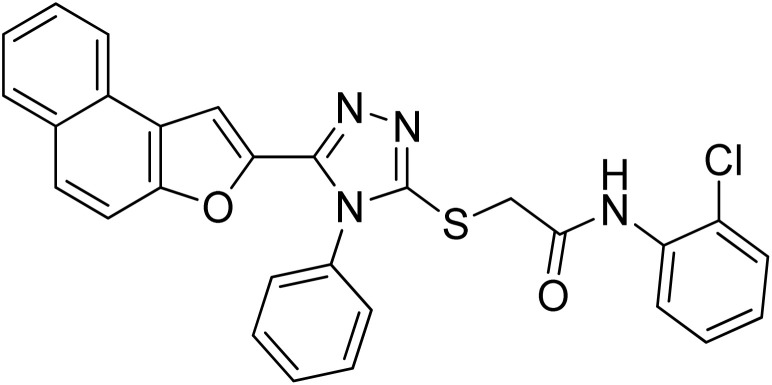

The development of novel and efficient tyrosinase inhibitors is a critical necessity of agricultural, cosmetic and medicinal chemistry. Bearing in mind the therapeutical potential of naphthofuran-containing organic compounds, we carried out the CTAB-catalyzed ultrasound-assisted synthesis of a library of novel naphthofuran-triazole joined N-aryl/alkyl acetamides 20(a–j) in 74–92% yield, which were further assessed for their tyrosinase inhibitory potential by taking kojic acid and ascorbic acid as standard inhibitors. The tyrosinase inhibitory assay demonstrated the promising tyrosinase inhibiting tendency of all prepared derivatives 20(a–h) as they all were found to be more efficient in comparison to the standard kojic acid. Similarly, most of the derivatives also exhibited tyrosinase inhibition potency in juxtaposition to ascorbic acid. More specifically, among the catalog of compounds, 20f and 20i exhibited potent inhibition results with IC50 = 0.51 ± 0.12 and 1.99 ± 0.07, respectively. Overall, 20f was shown to be the most efficacious tyrosinase inhibitor, owing to the presence of an electronegative group, i.e., 2-chloro substitution on the phenyl ring. The tyrosinase inhibition activity results of 20f and 20i were further supplemented with molecular docking analysis to validate experimental studies. In silico modelling findings revealed their significant interactions with the tyrosinase protein (PDB ID: 5OAE), thereby illustrating the efficient docking score of −7.10 kcal mol−1 and −6.95 kcal mol−1 in comparison to kojic acid (−5.03 kcal mol−1).

A novel series of naphthofuran-triazole conjugates has been synthesized to assess their potential against bacterial tyrosinase enzyme via in vitro and in silico studies.

1. Introduction

Various plants, microorganisms and animals are known to possess copper-containing metalloenzymes, i.e., tyrosinase, which is responsible for the synthesis of polyphenolic compounds, melanin and neuromelanin.1–3 In insects, the tyrosinase enzyme is involved in the hardening of cuticles and invasion-triggered encapsulation.4 Monophenols are hydroxylated and o-quinones are obtained from o-diphenols in the presence of the tyrosinase enzyme, to synthesize melanin.5–8 Melanin is involved in the pigmentation and color templates of mammalian skin. Furthermore, melanin also guards the skin from harmful sun radiation.9 Several dermatological complications originate from the anomalous decline of melanin.10 In a similar manner, many skin problems (i.e., senile lentigines, cervical poikiloderma, melasma, acanthosis nigricans and freckles) arise as a result of excessive production of melanin and aggregation of pigmentation.11 Moreover, studies have confirmed that the excess tyrosinase activity results in neurodegenerative diseases, i.e., Parkinson's disease among mammals12 and skin cancer high-risk factors.13 In addition, unrestrained activity of the tyrosinase enzyme leads to immense browning in fruits and vegetables. As a result, the quality and trade value of these fruits and vegetables severely suffer.14–16 These conditions highlight the requirement of efficient tyrosinase inhibitors.

To date, various natural and synthetic tyrosinase inhibitors have been shown to suppress or reduce the extravagant activity of the tyrosinase enzyme. Some examples of natural tyrosinase inhibitors include kojic acid, arbutin, kaempferol, cuminaldehyde and glabrene. Similarly, dopastin, tropolone, cupferron and 4-hexylresourcinol are some examples of synthetic tyrosinase inhibitors.17 However, only arbutin and kojic acid are harnessed in medicinal and cosmetic industry. These inhibitors have some uninviting side effects, i.e., mutagenesis, DNA alterations, malignancy induction and other susceptibilities.18–20 In order to minimize the dreadful aspects of excessive tyrosinase activity, researchers are continuously trying to develop novel and efficient tyrosinase inhibitors.21–27

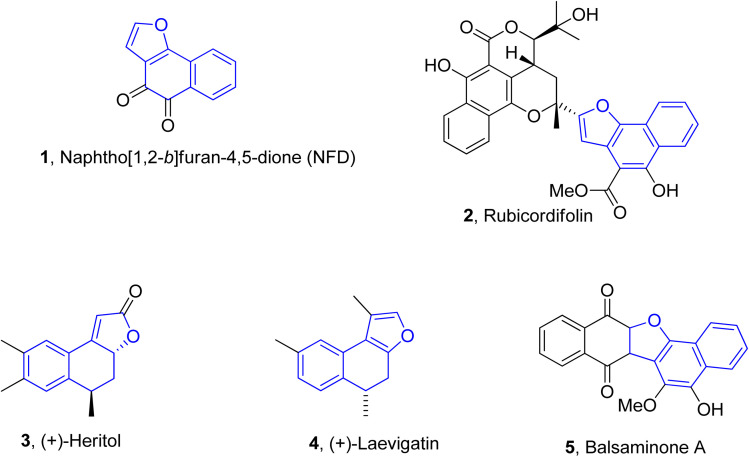

Naphthofuran-based derivatives are of impeccable significance owing to their wide biological potential.28–30 Organic compounds incorporated with naphthofuran scaffolds are known to be highly effective against several ailments, i.e., bacterial,31 viral32 and fungal diseases.33 These scaffolds have also been ascertained to be active against diabetes34 and inflammatory diseases.35 These also act as efficient anti-oxidant36 and pain-relieving agents.37 Various natural products are endowed with the naphthofuran moiety and exhibit potent pharmacological applications. For example, the naphthofuran-substituted naturally occurring organic compound, i.e., NFD (naphtho[1,2-b]furan-4,5-dione) 1 was originally obtained from Avicennia marina. NFD was revealed as a potent anti-tumour agent that displayed anti-proliferative activities against the human cervical, hepatocellular and epidermoid cancer cell lines.38 Similarly, rubicordifolin 2,39 (+)-heritol 3,40–42 (+)-laevigatin 443 and balsaminone A 544 are some other examples of naturally occurring naphthofuran-constituting organic compounds, which are highly acclaimed as significant pharmacological and anti-cancer agents (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Structures of naphthofuran-constituting biologically active natural products.

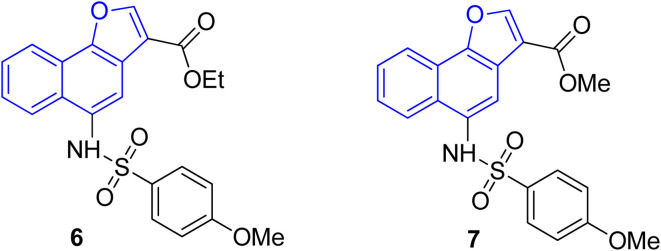

The pharmacological activity of various naphthofuran derivatives has been significantly explored by researchers to reveal their therapeutic efficacy. Nitro-based naphthofurans have also been extensively investigated for their mutagenic potential.45 These functionalized scaffolds are also utilized as effective NF-κβ, i.e., nuclear transcription factor kappa-β inhibitors and IKK-β (inhibitory kappa β-kinase) inhibitors.28 The naphthofuran-based sulfonamides 6 & 7 have been discovered to be efficacious agents against TNBC (triple-negative breast cancer)46 (Fig. 2). Many naphthofuran derivatives have also proven themselves to be promising tyrosinase inhibitors28 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Structures of biologically active naphthofuran derivatives.

Several nitrogen and oxygen containing heterocyclic scaffolds have become quintessential in the development of biologically active organic compounds owing to their myriad biological and medicinal applications.47–52 Benzimidazole,53 coumarin,54 benzofuran,55 thiadiazoles,56 oxadiazole,57 piperazine58 and triazole59-based organic compounds have been observed to illustrate anti-cancer, anti-viral, anti-bacterial, anti-depressant, anti-inflammatory, anti-histaminic, anti-diabetic, anti-oxidant and analgesic properties. The combination of two or three heterocyclic frameworks has been determined to certainly aggravate their biological potential.60,61 Considering the impact of heterocyclic hybridization approach, our research group has devoted efforts to synthesize and utilize the pharmacological potential of these nitrogen- and oxygen-constituting heterocyclic organic compounds, which were assessed to depict remarkable tyrosinase inhibition activity. Earlier, we established the synthesis and bacterial tyrosinase inhibition studies of benzofuran oxadiazoles endowed with sulfur alkylated amides 8 (ref. 62) and tosyl piperazine-based dithiocarbamates 9.63 We also reported the preparation and assessment of triazole-joined β-hydroxy sulfides 10 (ref. 64) and coumarin-based triazole derivatives 11 (ref. 65) as efficacious tyrosinase inhibitors (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Structures of previously developed efficient tyrosinase inhibitors.

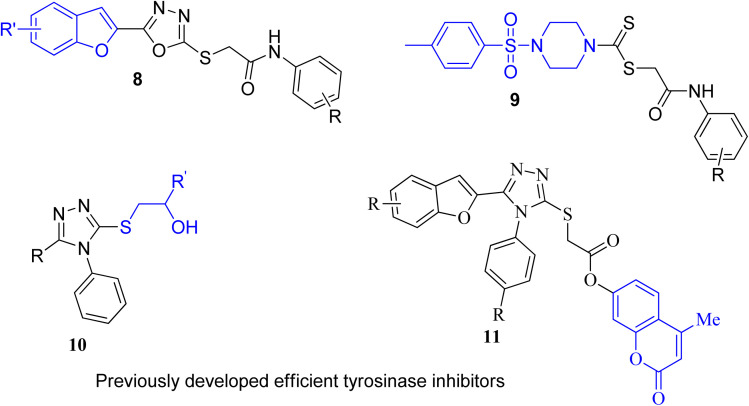

Factoring in the remarkable tyrosinase inhibition tendency of organic compounds endowed with triazole, oxadiazole and piperazine-based heterocyclic frameworks, we decided to proceed with the hybridization of biologically active fragments. We built the rationale design of developing novel naphthofuran-triazole hybrids as a result of hybridization of medicinally potent naphthofuran-based triazole ring with N-alkylated/arylated acetamide derivatives. The synthesized naphthofuran-triazole hybrids were further processed by ascertaining their efficacy as promising bacterial tyrosinase inhibitors (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Rational design of the novel naphthofuran triazole–acetamide hybrids 20(a–j).

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

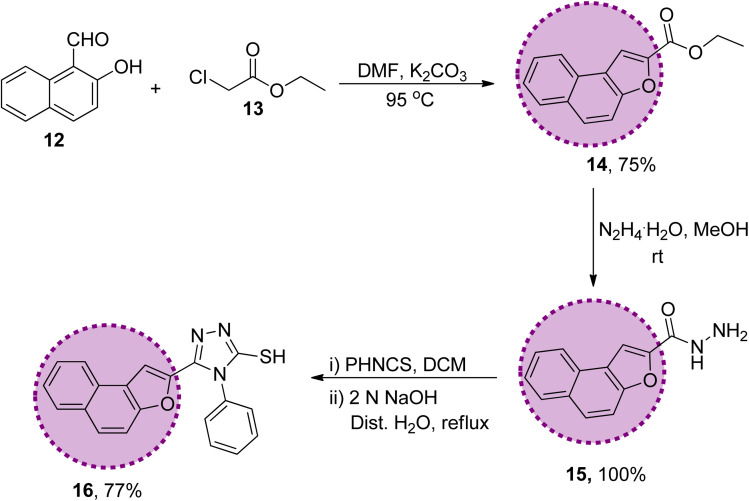

The synthetic strategy of naphthofuran-based derivatives is depicted in Schemes 1–3. Reaction of commercially available 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde 12 with ethyl chloroacetate 13 using potassium carbonate in dimethylformamide at 90–95 °C furnished naphthofuran ester 14 in 75% yield.66 The naphthofuran ester 14 was then transformed to corresponding carbohydrazide 15 (in 100% yield) on reaction with hydrazine monohydrate in methanol under reflux conditions. The synthesized naphthofuran-based carbohydrazide 15 was further converted to respective triazole scaffold 16 (in 77% yield) on treatment with phenylisothiocyanate in dichloromethane followed by nucleophilic cyclization by exploiting 2 N NaOH solution and distilled water under reflux conditions67 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the naphthofuran-based-triazole precursor 16.

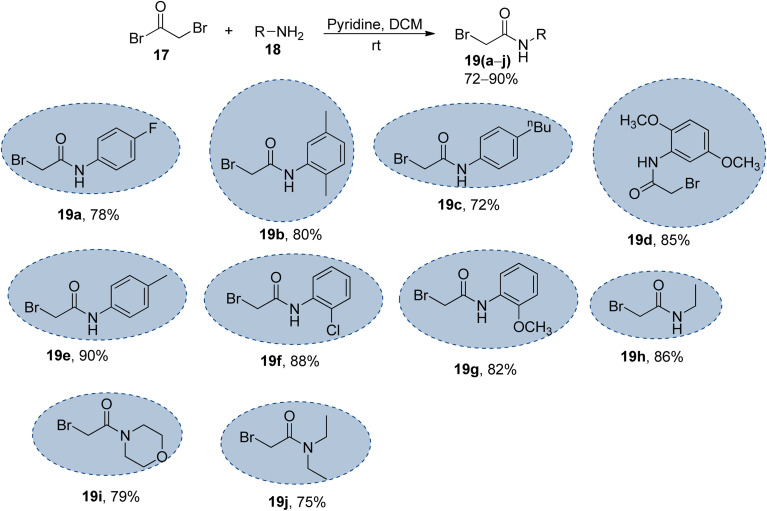

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the bromo-acetanilide/acetamide precursors 19(a–j); 17 (1.2 equiv.), 18 (1.0 equiv.), pyridine (1.2 equiv.).

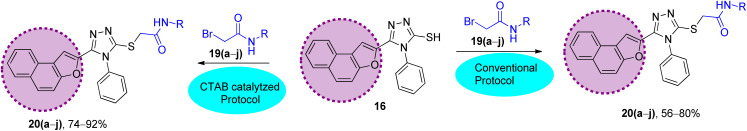

Scheme 3. Synthetic scheme to prepare the naphthofuran triazole–acetamide hybrids 20(a–j)via conventional and CTAB-catalyzed protocol: (A) conventional protocol: K2CO3, DMF, 95 °C; (B) CTAB-catalyzed protocol (improved protocol): CTAB, K2CO3, KI, DMF, ultrasound, 80 °C.

The synthesized naphthofuran-based triazole 16 was then subjected to nucleophilic substitution reaction with substituted bromo-acetanilides 19(a–j) (obtained by treating substituted amines/anilines 18(a–j) with bromoacetyl bromide 17 (ref. 68) (Scheme 2)) via two routes. One pathway involved the conventional route utilizing potassium carbonate as a base in DMF solvent68 to access the target molecules in 56–80% yield. The second route was proceeded with the catalytic addition of CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) and potassium iodide in dimethylformamide under sonication conditions, which afforded the targeted naphthofuran-based triazole–acetamide hybrids 20(a–j) in comparatively higher yields (74–92%) within a short duration (Scheme 3, Table 1).

Comparison between the ultrasound-assisted CTAB catalyzed protocol and conventional protocol.

| Sr. no. | Compounds | Conventional protocol | Ultrasound-assisted CTAB-catalyzed protocol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | Duration | Yield | Duration | ||

| 1 | 20a | 78% | 18 h | 84% | 60 minutes |

| 2 | 20b | 56% | 14 h | 74% | 40 minutes |

| 3 | 20c | 68% | 13 h | 84% | 30 minutes |

| 4 | 20d | 75% | 14 h | 92% | 50 minutes |

| 5 | 20e | 70% | 16 h | 88% | 40 minutes |

| 6 | 20f | 58% | 22 h | 76% | 20 minutes |

| 7 | 20g | 61% | 18 h | 79% | 50 minutes |

| 8 | 20h | 62% | 24 h | 80% | 30 minutes |

| 9 | 20i | 59% | 12 h | 77% | 60 minutes |

| 10 | 20j | 64% | 18 h | 80% | 30 minutes |

2.2. Anti-tyrosinase activity

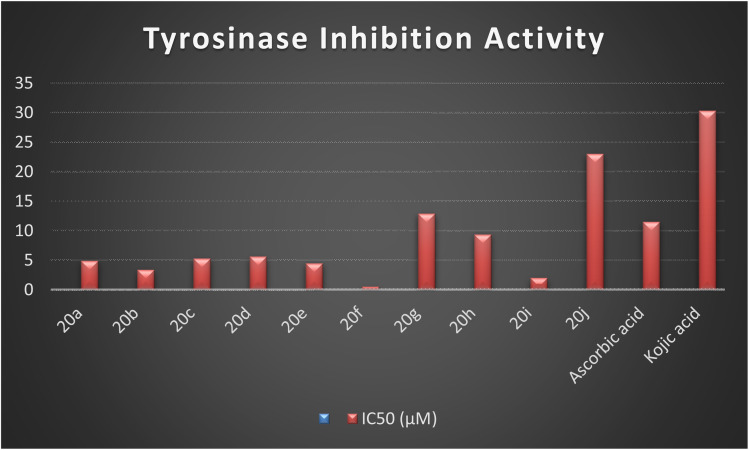

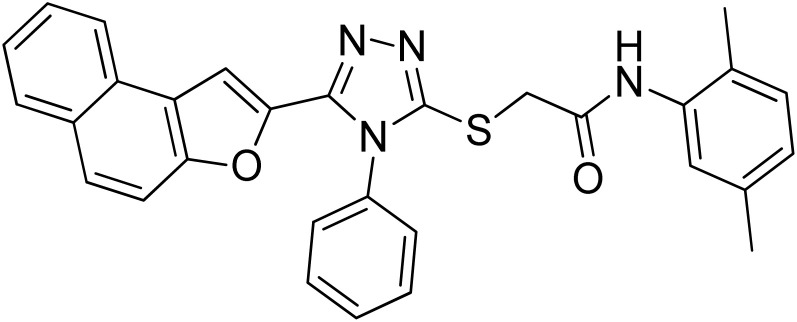

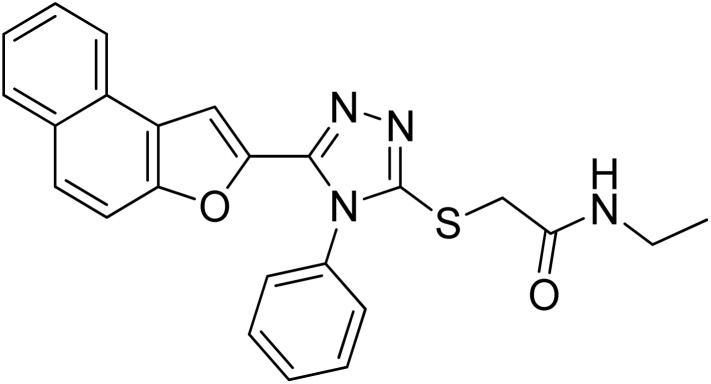

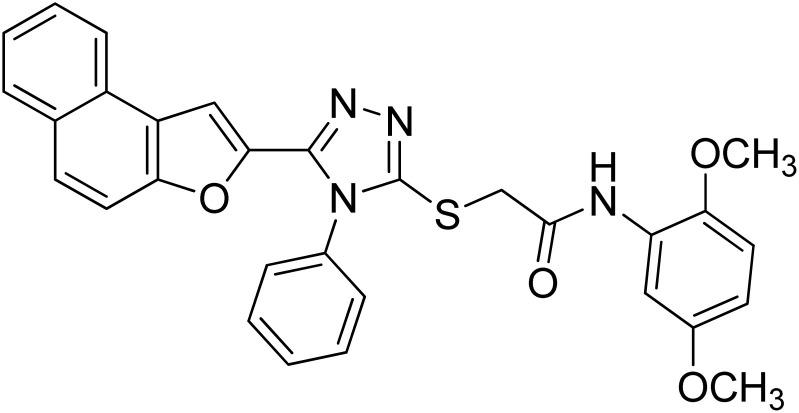

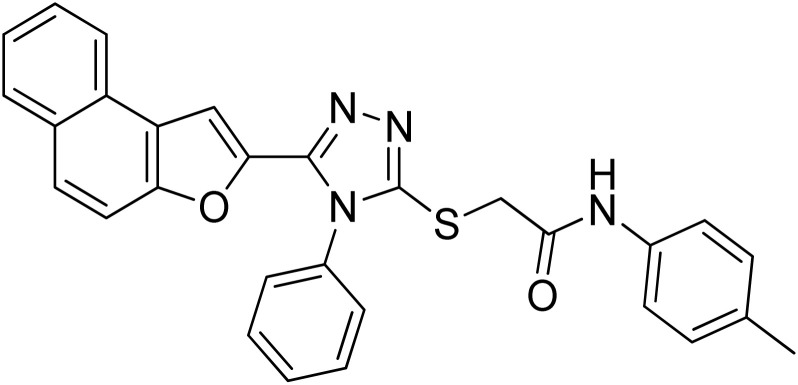

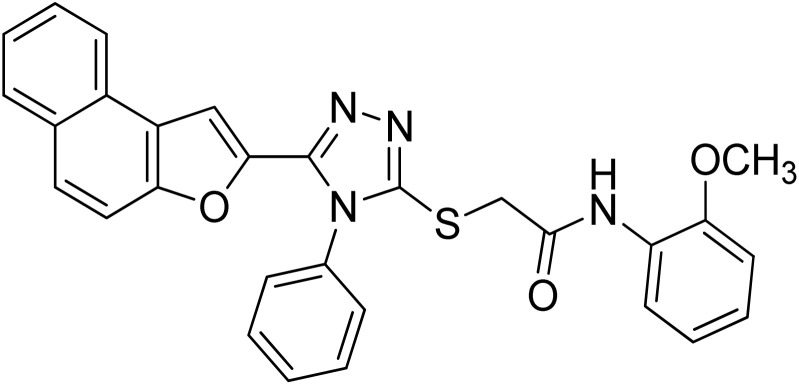

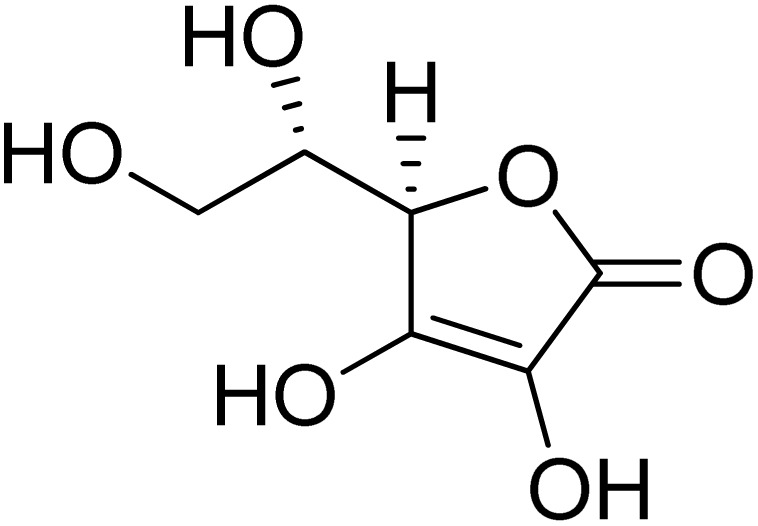

The synthesized naphthofuran-based derivatives were analyzed via in vitro assay to determine their potential astyrosinase inhibitors. The tyrosinase enzyme was originally extracted using previously reported method.69,70 The results indicated that almost all of the synthesized compounds were found to be more potent against tyrosinase enzyme as compared to the standard, i.e., ascorbic acid and kojic acid (IC50 = 11.5 ± 1.00 & 30.34 ± 0.75) (Fig. 5). Their IC50 values were found to be in the range of 0.51–23.03 μM. The compound 20f was the most potent enzyme inhibitor among all other derivatives with percentage inhibition of 32.34 ± 0.07 and IC50 = 0.51 ± 0.12, exhibiting more potency than both standards. Moreover, the results indicated that 20i exhibited high activity as a tyrosinase inhibitor with percentage inhibition = 30.55 ± 0.1 and (IC50 = 1.99 ± 0.07), in comparison with standards. Similarly, percentage inhibition of compounds 20a, 20b, 20c, 20d & 20e was found to be in the range of 22.62–31.40 (with IC50 value range = 3.37 ± 0.13–5.63 ± 0.12), depicting efficient inhibitory potential than ascorbic acid and kojic acid. Among these five hybrids, 20b displayed efficient tyrosinase inhibition (31.40 ± 0.25) with IC50 value of 3.37 ± 0.13 μM. Para-substituted hybrids 20a and 20e were observed to portray the 22.84 ± 0.05 and 4.46 ± 0.25 percentage inhibition with corresponding IC50 values of 4.88 ± 0.17 μM and 4.46 ± 0.25 μM. Moreover, hybrids 20c and 20d illustrated percentage tyrosinase inhibition of 22.62 ± 0.30 and 22.77 ± 0.17 with 5.29 ± 0.15 and 5.63 ± 0.12 μM IC50 values, respectively.

Fig. 5. Graphical illustration of the enzyme inhibition activity of the synthesized hybrids 20(a–j) and standards.

In a similar manner, 20h was also found to be an effective tyrosinase inhibitor (with percentage inhibition of 13.92 ± 0.11 and IC50 = 9.36 ± 0.06 μM) as compared to both standards. However, the synthesized derivatives 20g and 20j had significantly less tyrosinase inhibition potential with percentage inhibition = 5.40 ± 0.05 & 2.61 ± 0.50, respectively. Their IC50 values were found to be 12.9 ± 0.15 μM and 23.03 ± 0.18 μM, respectively, indicating the trivial tyrosinase inhibition as compared to the standard, i.e., ascorbic acid. However, they were found to be more potent in comparison to kojic acid. The descending order of the tyrosinase inhibition potential of synthesized hybrids and reference standards, as determined by in vitro assay is given as 20f > 20i > 20b > 20e > 20a > 20c > 20d > 20h > ascorbic acid > 20g > 20j > kojic acid, as displayed in Table 2.

Tyrosinase inhibition potential of the synthesized naphthofuran triazole–acetamide hybrids 20(a–j).

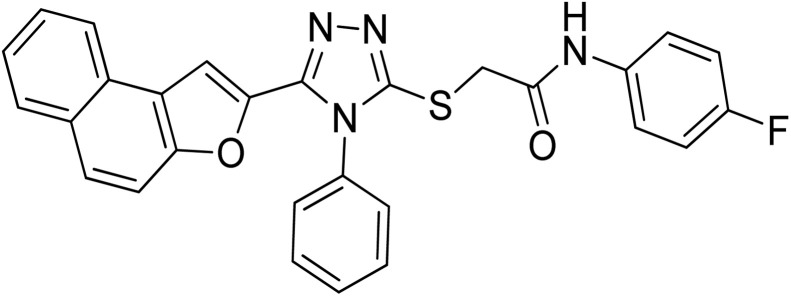

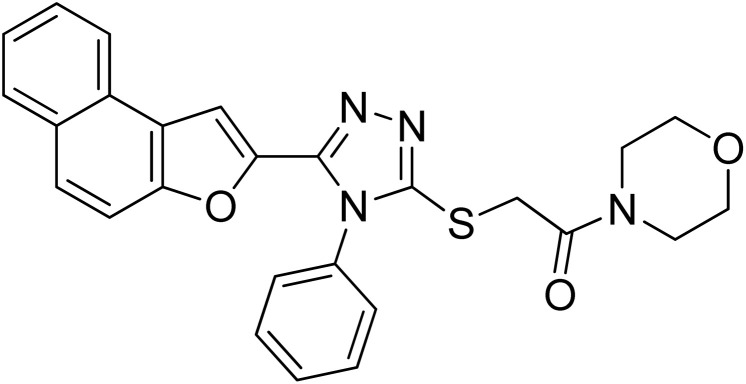

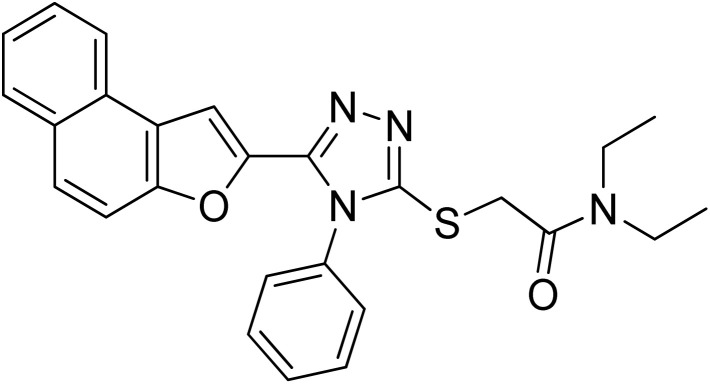

| Sr. no. | Compound | Structure | Percentage inhibition | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20a |

|

22.84 ± 0.05 | 4.88 ± 0.17 |

| 2 | 20b |

|

31.40 ± 0.25 | 3.37 ± 0.13 |

| 3 | 20c |

|

22.62 ± 0.30 | 5.29 ± 0.15 |

| 4 | 20d |

|

22.77 ± 0.17 | 5.63 ± 0.12 |

| 5 | 20e |

|

28.21 ± 0.05 | 4.46 ± 0.25 |

| 6 | 20f |

|

32.34 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.12 |

| 7 | 20g |

|

5.40 ± 0.05 | 12.9 ± 0.15 |

| 8 | 20h |

|

13.92 ± 0.11 | 9.36 ± 0.06 |

| 9 | 20i |

|

30.55 ± 0.1 | 1.99 ± 0.07 |

| 10 | 20j |

|

2.61 ± 0.50 | 23.03 ± 0.18 |

| 11 | Ascorbic acid |

|

58.66 ± 1.00 | 11.5 ± 1.00 (ref. 50) |

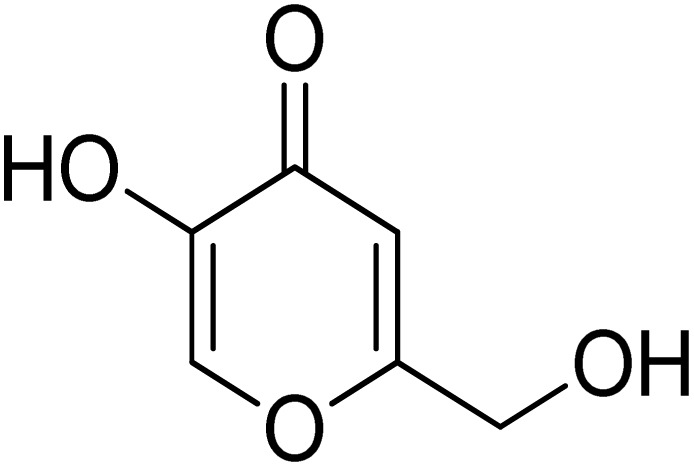

| 12 | Kojic acid |

|

6.80 ± 0.58 | 30.34 ± 0.75 (ref. 50) |

2.3. Docking analysis

Compounds (20f, 20i) with the most promising tyrosinase inhibition activity were selected for IFD (induced-fit docking) to authenticate the anti-tyrosinase activity. The reliability of the docking analysis was evaluated by cognate redocking. All possible types of interaction between the ligand and tyrosinase protein, i.e., 5OAE, were comprehensively analyzed. The native ligand SVF was redocked in a molecular operating environment, and the self-docking result showed a root mean square deviation (RMSD) value between the native ligand and redocked equal to 0.92 Å (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. IFD docking validation by RMSD between the native ligand (grey) and redocked ligand (maroon).

The binding affinities of compounds (20f & 20i) with the active site of the 5OAE protein were computed. Kojic acid was used as a standard IFD threshold with a binding score of ΔG −5.03 kcal mol−1. The compounds (20f & 20i) exhibited a higher docking score (ΔG −7.10 and −6.95 kcal mol−1, respectively) than standard kojic acid, indicating their greater tyrosinase inhibitory potential (Table 3).

Molecular docking scores and interactions.

| Compound | Binding score kcal mol−1 | Residue interacting with ligand | Types of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

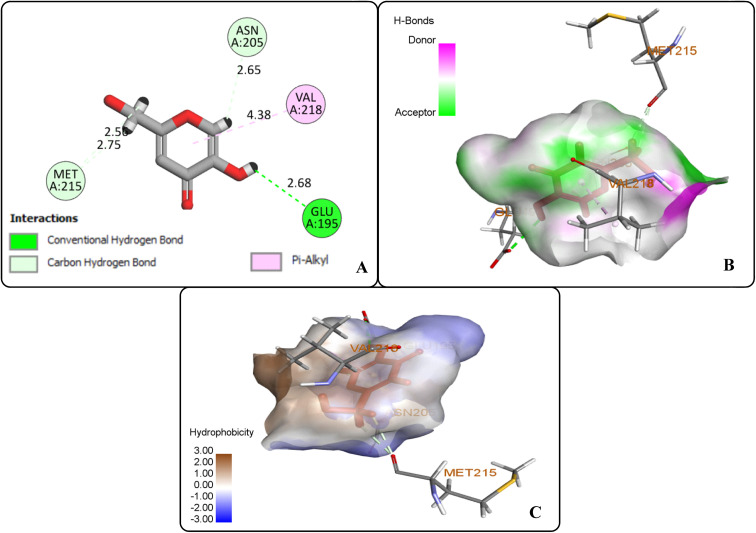

| Kojic acid | −5.03 | ASN-205, VAL-218, GLU-195, MET-215 | Hydrogen bonding, π–alkyl |

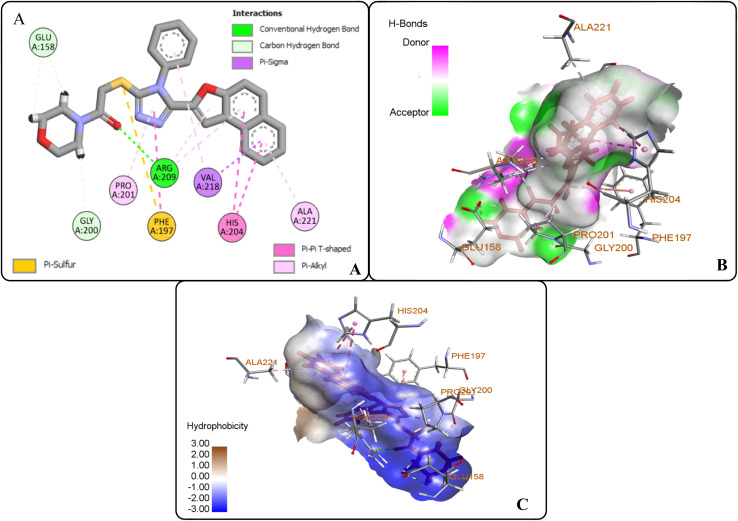

| 20i | −6.95 | GLU-158, GLY-200, PRO-201, ARG-209, PHE-197, VAL-218, HIS-204, ALA-221 | Hydrogen bonding, π–sulfur, π–σ, π–π shaped, π–alkyl |

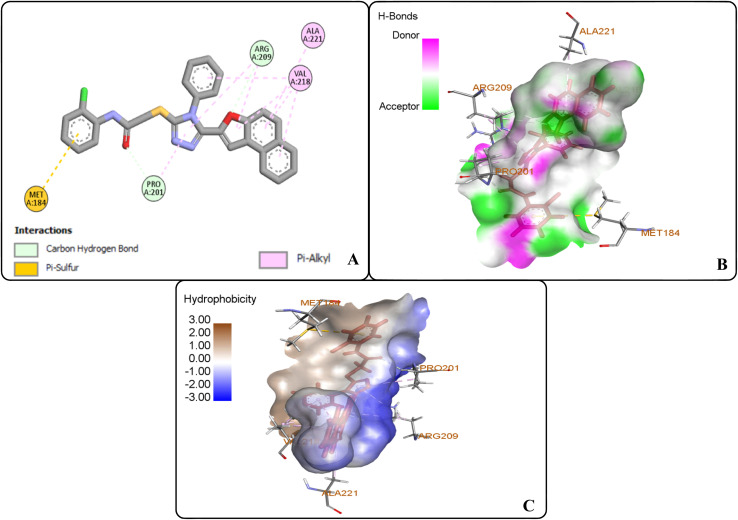

| 20f | −7.10 | MET-184, PRO-201, ARG-209, VAL-218, ALA-221 | Hydrogen bonding, π–alkyl, π–sulfur |

The protein ligand interaction study of the docked compound revealed that they interact with the receptor site around the copper core, which might be responsible for tyrosinase inhibition. It was observed that kojic acid showed both hydrophobic (VAL-218 (π–alkyl) and hydrogen bonding (GLU-195, ASN-205, MET-215) interactions (Fig. 7). However, the compound 20i showed hydrogen bonding interaction with ARG-209, GLY-200, GLU-158) and hydrophobic interactions with HIS-204, PRO-201, VAL-218, ALA-221 and pi–sulfur interaction with PHE-197 residue. However, compound (20f) exhibited hydrogen bonding interactions with ARG-209, PRO-201, and hydrophobic interactions with ALA-221, VAL-218 and pi–sulfur interaction with MET-184 residue.

Fig. 7. Protein–ligand interactions of kojic acid: (A) 2D interactions, (B) hydrogen bonding interactions, and (C) hydrophobic interactions.

The docking analysis inferred that the –OH group of kojic acid formed conventional H-bonding interaction with GLU-195 at 2.68 Å. Moreover, its methylene hydrogens and hydrogen atom of the pyran-one ring were observed to display carbon–hydrogen bonding interactions with MET-215 and ASN-205 at 2.75 Å and 2.65 Å, respectively. Similarly, pyran-one ring was found to portray hydrophobic interaction (π–alkyl) with VAL-218 at 4.38 Å (Fig. 7(A–C)).

However, the docking results of 20i unveiled that its carbonyl oxygen forms conventional H-bonding with ARG-209 at 5.97 Å. Moreover, hydrogen atoms of morpholine ring were observed to be involved in carbon–hydrogen bonding interactions with GLU-158 and GLY-200 via 2.86 Å and 2.49 Å. Similarly, triazole ring was found to develop hydrophobic interactions with PRO-201 (π–alkyl) via 4.71 Å bond distance and π–π T-shaped interactions with PHE-197 at a bond distance of 4.72 Å. Similarly, naphthofuran rings underwent hydrophobic interactions with ALA-221 (π–alkyl) via 4.64 Å and HIS-204 (π–π T-shaped) via 5.57 Å and 5.42 Å bond distances. Moreover, phenyl ring attached to triazole moiety and naphthofuran ring were found to engage in hydrophobic interactions (π–alkyl and π–σ interactions, respectively) with VAL-218 residue via a bond distance of 5.17 Å and 2.86 Å, respectively. In addition, the sulphur atom of compound 20i formed π–sulfur linkage with PHE-197 at 5.97 Å bond distance (Fig. 8(A–C)).

Fig. 8. Protein–ligand interactions of 20i: (A) 2D interactions, (B) hydrogen bonding interactions, and (C) hydrophobic interactions.

The docking studies of 20f revealed that the oxygen atom of the carbonyl functionality and furan ring exhibited carbon–hydrogen bonding interactions with PRO-201 and ARG-209 at 2.61 Å and 2.82 Å, respectively. The benzene ring of the anilide fragment formed a π–sulfur hydrophobic interactions with MET-184 that was 4.97 Å in the bond distance. Similarly, triazole ring was observed to be involved in π–alkyl hydrophobic interactions with PRO-201 and ARG-209 at a distance of 4.87 Å and 5.38 Å, respectively. Moreover, the furan ring showed π–alkyl hydrophobic interactions with ARG-209 and VAL-218 via 5.40 Å and 5.14 Å bond distances, respectively. Furthermore, the π–alkyl hydrophobic interactions were found to establish between fused benzene rings of naphthofuran functionality and amino acid residues i.e., VAL-218 (via 4.36 Å and 4.75 Å) and ALA-221 (via 5.27 Å). In addition, benzene ring attached to the triazole scaffold also formed π–alkyl hydrophobic interactions with VAL-218 at 2.82 Å bond distance. Thus, induced fit docking results supported the experimental findings that identified compound 20f and 20i as potent tyrosinase inhibitors (Fig. 9(A–C)).

Fig. 9. Protein–ligand interactions of 20f: (A) 2D interactions, (B) hydrogen bonding interactions, and (C) hydrophobic interactions.

2.4. Kinetic studies

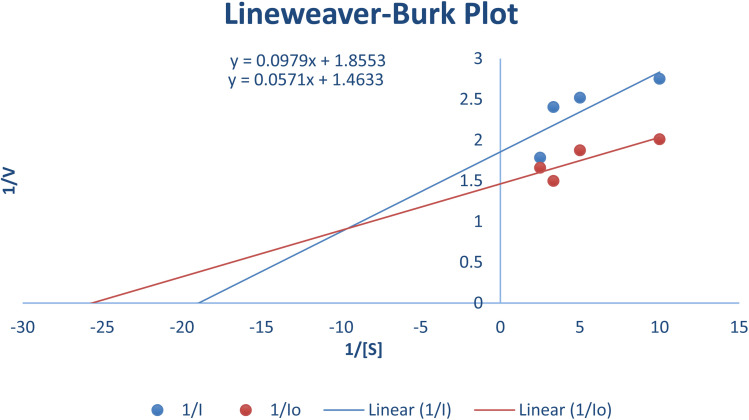

The most potent derivative 20f was subjected to kinetic studies against diverse concentrations of tyrosine substrate (0.1–1 mM) to find out the inhibition mode and inhibition constants. The ES (Ki) and ESI  constants were determined to assess the inhibition potency of synthesized hybrid 20f against free enzyme and ES-complex (enzyme–substrate complex). To determine the type of inhibition, Lineweaver–Burk plot was plotted (1/V versus 1/[S]), which indicated that the compound 20f inhibited the activity of tyrosinase enzyme non-competitively. As the value of Vmax was observed to change without influencing the Km value, which was interpreted to be 0.06. The value of Ki (EI dissociation constant) and

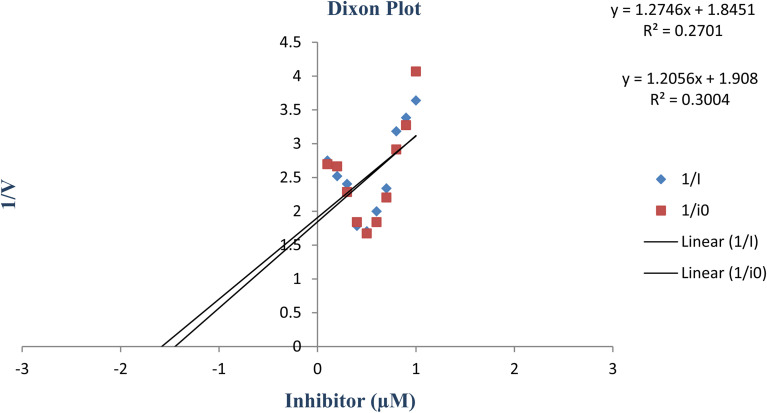

constants were determined to assess the inhibition potency of synthesized hybrid 20f against free enzyme and ES-complex (enzyme–substrate complex). To determine the type of inhibition, Lineweaver–Burk plot was plotted (1/V versus 1/[S]), which indicated that the compound 20f inhibited the activity of tyrosinase enzyme non-competitively. As the value of Vmax was observed to change without influencing the Km value, which was interpreted to be 0.06. The value of Ki (EI dissociation constant) and  (ESI dissociation constant) for the derivative 20f were inferred to be 0.07 and 1.77 mM, respectively, as calculated from both curves of the Lineweaver–Burk plot (Fig. 10). In addition, the Dixon plot was also sketched by plotting inhibitor concentrations against inverse of velocities, which further verified the non-competitive type enzyme inhibition activity (Fig. 11).

(ESI dissociation constant) for the derivative 20f were inferred to be 0.07 and 1.77 mM, respectively, as calculated from both curves of the Lineweaver–Burk plot (Fig. 10). In addition, the Dixon plot was also sketched by plotting inhibitor concentrations against inverse of velocities, which further verified the non-competitive type enzyme inhibition activity (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10. Lineweaver–Burk Plot depicting the enzyme inhibition activity of tyrosinase enzyme in the presence of the potent hybrid 20f.

Fig. 11. Dixon plot of the concentrations of derivative 20f (inhibitor) vs. the reciprocal of the enzyme velocities.

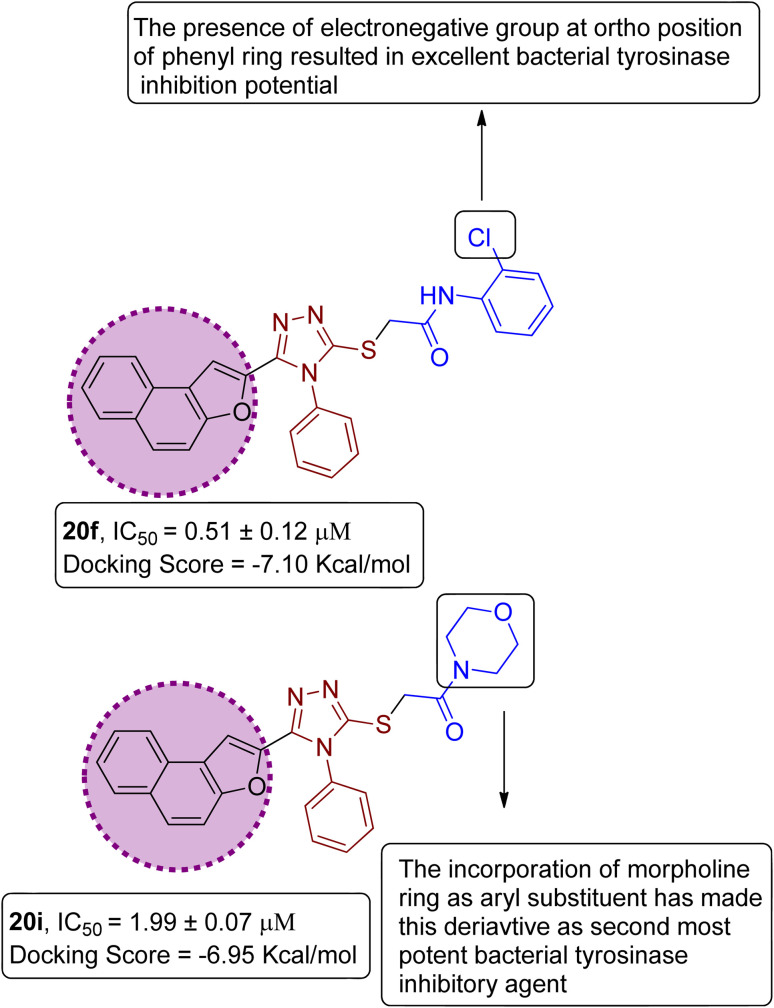

2.5. Structure–activity relationship

On the basis of the in vitro tyrosinase assay and computational studies inferences, structure–activity relationship of the synthesized naphthofuran-triazole conjugates was deduced. The enzyme inhibitory potential of different synthesized compounds was found to be dependent upon the type of substituted Ar group. It was observed from the structure–activity relationship (SAR) that compound 20f employing Ar as 2-ClPh exhibited the most potent enzyme inhibition activity along with the most efficient binding score of −7.10 kcal mol−1 owing to the presence of the electronegative group, i.e., Cl on the ortho position of the phenyl ring. Similarly, by substituting Ar = morpholine, 20i, was synthesized, which also manifested efficient IC50 = 1.99 μM and docking score of −6.95, thereby acting as the second-most potent enzyme inhibitory agent in comparison to standard kojic acid (displaying IC50 value of 30.34 with −5.03 docking score) (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Structure–activity relationship of most efficient bacterial tyrosinase inhibitors 20f & 20i.

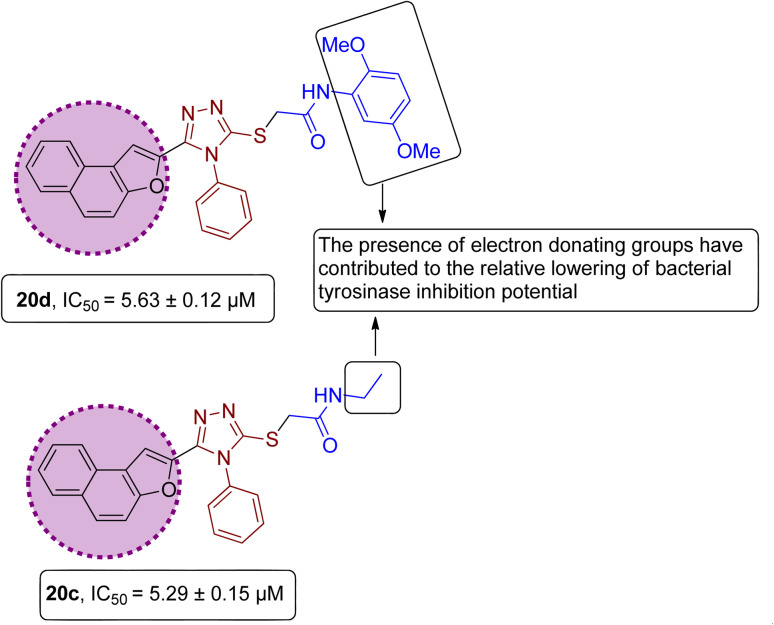

However, it was observed from the obtained results that the derivatives obtained by substituting electron-donating groups bearing phenyl rings (20a, 20b, 20c, 20d & 20e) showed comparatively low potency with IC50 ranging between 3.37 and 5.29. Among these five hybrids, 2,5-dimethyl substituted phenyl ring endowed hybrid 20b exhibited efficient bacterial tyrosinase inhibition with an IC50 value of 3.37 ± 0.13 μM. Moreover, substitution of the methyl and n-butyl group at the para position on the phenyl ring of synthesized hybrids 20d and 20a resulted in promising IC50 values of 4.46 ± 0.25 μM and 4.88 ± 0.17 μM respectively. Moreover, electron-donating effect of 2,5-dimethoxy substituted phenyl ring on derivative 20d and ethyl linked naphthofuran-triazole conjugate 20c contributed to the relative lowering of bacterial tyrosinase inhibition potential, as indicated by their respective IC50 values (5.63 ± 0.12 μM and 5.29 ± 0.15 μM) (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Structure–activity relationship of bacterial tyrosinase inhibitors 20d & 20c.

However, the 4-flouro phenyl ring-substituted naphthofuran derivative (20h) portrayed less inhibition activity (with IC50 = 9.63 μM), as compared to 20f, bearing an electronegative group at the ortho position. Overall, among the synthesized derivatives, 20g & 20j (with 2-methoxy substitution at the phenyl ring group and diethyl substitution, respectively) were found to be least potent with IC50 values of 12.9 & 23.03 μM, respectively, among the other synthesized hybrids. Thus, the SAR interpretation inferred that the presence of electron donating groups substituted Ar functionality on prepared naphthofuran-triazole conjugates is the main factor behind the low enzyme inhibition activity. The bacterial tyrosinase inhibition potential of synthesized hybrids and reference standards is in the following order: 20f > 20i > 20b > 20e > 20a > 20c > 20d > 20h > ascorbic acid > 20g > 20j > kojic acid.

2.6. ADMET analysis

The ADMET properties are determined as a preliminary step towards the process of drug development and its discovery. All of the synthesized naphthofuran-triazole conjugates 20(a–j) were subjected to ADMET evaluation by processing compounds via online software ADMETlab 3.0. ADMETlab 3.0 is an updated software which offers detailed insights regarding ADMET features involving physiochemical, absorption, distribution, medicinal chemistry parameters, metabolism, excretion and toxicity values. Significant ADMET properties of all synthesized hybrids were focused to provide assistance in drug design process which include molecular weight, no. of rotatable bonds no. of hydrogen bond donors (nHD) and acceptors (nHA), log P, total polar surface area (TPSA) log, Lipinski's rule of five validation and synthetic accessibility score. Moreover, Caco-2-permeablity, human intestinal absorption, MDCK permeability scores, Pgp-inhibitor & substrate probability with blood–brain barrier probability scores. In addition, several metabolism, excretion and toxicity features of synthesized hybrids were also estimated.

Lipinski's rule of five states that a molecule must possess certain physiochemical features to behave like a drug candidate which include (a) HBD; equal or less than 5 (b) HBA: equal or less than 10 (c) MW; equal or less than 500 Da (d) log P; equal or less than 5. The interpretation of physiochemical properties of synthesized hybrids revealed their compatibility with the Lipinski's rule of five except 20a, due to exceeding molecular weight than 500 along with log P value greater than 5. However, for hybrids 20(b–j), Lipinski's rule was accepted. Lipinski's rule is considered rejected for a compound, if it violates more than one mentioned physiochemical parameters. Synthetic accessibility score (Synth) was determined to be efficient for all prepared derivatives (Table 4).

Physiochemical and medicinal properties of synthesized hybrids 20(a–j).

| Compound | Molecular weight | nHA | nHD | Log P | TPSA log | nRot | Synthetic accessibility score | Lipinski's rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20a | 532.19 | 6 | 1 | 6.275 | 72.95 | 10.0 | 2.0 | Rejected |

| 20b | 504.16 | 6 | 1 | 4.573 | 72.95 | 7.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20c | 428.13 | 6 | 1 | 3.384 | 72.95 | 7.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20d | 536.15 | 8 | 1 | 4.386 | 91.41 | 9.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20e | 490.15 | 6 | 1 | 4.599 | 72.95 | 7.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20f | 510.09 | 6 | 1 | 4.552 | 72.95 | 7.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20g | 506.14 | 7 | 1 | 4.256 | 82.18 | 8.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20h | 494.12 | 6 | 1 | 4.412 | 72.95 | 7.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20i | 470.14 | 7 | 0 | 2.688 | 73.39 | 6.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

| 20j | 456.16 | 6 | 0 | 3.805 | 64.16 | 8.0 | 2.0 | Accepted |

Caco-2-permeability refers to the intestinal permeability, which is estimated to predict the in vivo absorption of the drug candidate. Any value higher than −5.15 log unit corresponds to optimal permeability. All of the prepared derivatives depicted excellent permeability, along with remarkable human intestinal absorption values. More specifically, hybrids 20b, 20f and 20j exhibited efficient HIA absorption output values. In addition, all of the prepared hybrids depicted efficient volume distribution (VDss) except 20c and 20j. Compound with optimal value of blood–brain barrier (BBB) refers to its efficient lipophilicity and the output values of synthesized hybrids for BBB indicate their probability to act as blood-brain permeable drug like candidates. The output values for Pgp-substrate and Pgp-inhibitor correlates to their tendency to behave as corresponding substrate and inhibitor (Table 5).

Absorption and distribution properties of synthesized hybrids 20(a–j).

| Compound | Caco-2 permeability | HIA | BBB | PPB | MDCK-permeability | Pgp-inhibitor | Pgp-substrate | VDss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20a | −4.972 | 0.015 | 0.512 | 99.367 | −4.614 | 0.971 | 0.0 | 0.629 |

| 20b | −5.031 | 0.0 | 0.884 | 97.656 | −4.63 | 0.992 | 0.0 | 0.374 |

| 20c | −5.111 | 0.003 | 0.386 | 96.617 | −4.691 | 0.324 | 0.188 | −0.378 |

| 20d | −4.93 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 98.131 | −4.542 | 0.943 | 0.0 | 0.325 |

| 20e | −5.077 | 0.001 | 0.767 | 97.504 | −4.63 | 0.97 | 0.0 | 0.319 |

| 20f | −5.074 | 0.0 | 0.87 | 97.45 | −4.696 | 0.868 | 0.0 | 0.368 |

| 20g | −5.027 | 0.002 | 0.716 | 97.504 | −4.62 | 0.949 | 0.0 | 0.196 |

| 20h | −5.038 | 0.001 | 0.943 | 97.361 | −4.567 | 0.984 | 0.0 | 0.267 |

| 20i | −5.065 | 0.002 | 0.346 | 93.793 | −4.659 | 0.446 | 0.0 | 2.858 |

| 20j | −4.777 | 0.0 | 0.983 | 94.552 | −4.668 | 0.476 | 0.039 | −0.241 |

The metabolism properties indicate the probability of the prepared hybrids to act as CYP-based 1A2, 2C19, 2C9, 2D6, 3A4, 2B6 and 2C8 inhibitors. The results inferred that 20c, 20i & 20j has about less tendency to act as inhibitors, which certainly decrease the possibility of drug–drug interactions. In addition, CLplasma values were also determined to estimate the excretion or clearance of drug-like candidates from the plasma. The CLplasma values of all of the synthesized hybrids were determined to be less than 5 mL min−1 kg−1, indicating increased efficacy and improved bioavailability (Table 6).

Metabolism and excretion features of synthesized hybrids 20(a–j).

| Compound | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor | CYP2B6 inhibitor | CYP2C8 inhibitor | CLPlasma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20a | 0.705 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.41 | 0.677 | 1.0 | 2.202 |

| 20b | 0.092 | 1.0 | 0.997 | 0.986 | 0.991 | 0.785 | 1.0 | 1.826 |

| 20c | 0.199 | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.993 | 0.005 | 0.971 | 2.909 |

| 20d | 0.971 | 1.0 | 0.344 | 0.999 | 1.0 | 0.758 | 1.0 | 1.897 |

| 20e | 0.022 | 0.987 | 0.998 | 0.993 | 0.963 | 0.789 | 1.0 | 1.822 |

| 20f | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.364 | 1.0 | 2.049 |

| 20g | 0.055 | 1.0 | 0.805 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.902 | 1.0 | 2.063 |

| 20h | 0.034 | 0.988 | 0.995 | 1.0 | 0.621 | 0.277 | 1.0 | 1.648 |

| 20i | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.947 | 0.0 | 0.841 | 2.858 |

| 20j | 0.187 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.829 | 0.003 | 0.976 | 3.885 |

The synthesized hybrids were also assessed for their possible toxic effects as eye corrosive, eye irritant and carcinogenic agents. Their potential respiratory and AMES toxicity probabilities were also determined. The output values indicate their probability of being toxic or non-toxic. The ADMET results inferred the non-corrosive and non-irritant nature of all synthesized hybrids 20(a–j). Moreover, all hybrids depicted the low probability of being respiratory toxic. In addition, most of the synthesized derivatives were determined to be non-carcinogenic and non-AMES toxic. The results clearly illustrate the non-toxic and non-carcinogenic nature of the most potent tyrosinase inhibitor i.e., 20f (Table 7).

Toxicity estimation of the prepared derivatives of synthesized hybrids 20(a–j).

| Compound | Eye corrosion | Carcinogenicity | Respiratory toxicity | AMES toxicity | Eye irritation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20a | 0.0 | 0.264 | 0.558 | 0.373 | 0.319 |

| 20b | 0.0 | 0.625 | 0.323 | 0.665 | 0.152 |

| 20c | 0.0 | 0.816 | 0.384 | 0.677 | 0.248 |

| 20d | 0.0 | 0.6999 | 0.383 | 0.725 | 0.066 |

| 20e | 0.0 | 0.481 | 0.453 | 0.66 | 0.343 |

| 20f | 0.0 | 0.569 | 0.415 | 0.58 | 0.124 |

| 20g | 0.0 | 0.574 | 0.309 | 0.664 | 0.133 |

| 20h | 0.0 | 0.589 | 0.391 | 0.731 | 0.241 |

| 20i | 0.0 | 0.889 | 0.396 | 0.611 | 0.278 |

| 20j | 0.0 | 0.724 | 0.664 | 0.443 | 0.176 |

3. Conclusion

Here, we have synthesized a series of novel naphthofuran-based derivatives, which were then assessed for their tyrosinase inhibition activity. All the newly developed naphthofuran-incorporated derivatives were determined to be potent tyrosinase inhibitors. Among them, 20f & 20i were revealed to be promising tyrosinase inhibitors with IC50 = 0.51 ± 0.12 μM & 1.99 ± 0.07 μM in comparison to both standard tyrosinase inhibitors i.e., kojic and ascorbic acid. The chloro-substituted (at the ortho position) naphthofuran derivative 20f was found to be the most efficient tyrosinase inhibitor, among all the evaluated samples and standards. The tyrosinase inhibition results were found to be in accordance with molecular docking analysis, as 20f depicted the lowest docking score −7.10 kcal mol−1. The derivative 20f was observed to inhibit tyrosinase activity by forming carbon–hydrogen bonding, π–alkyl hydrophobic interactions and π–sulfur interactions within the active site of tyrosinase enzyme. Thus, the in vitro and computational studies revealed the biological potential of 20f as a potential lead compound for the development of novel and efficacious anti-tyrosinase drug. These findings will certainly assist scientists in carefully analyzing the pharmacological features of drug-like candidates in the drug design process (as approved by Lipinski's rule of five).

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemicals and instruments

All the solvents, reagents and precursors were obtained in analytical grade from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA), Merck (Burlington, MA, USA), and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The purchased chemicals were employed in their original form without carrying out any additional purification technique. The progress of reactions was monitored by using thin layer chromatography, employing n-hexane and ethylacetate ratio as developing solvent. The melting points of synthesized compounds were obtained by utilizing WRS-1B mp apparatus. 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectroscopy was carried out by utilizing Bruker 400 MHz FT-NMR spectrophotometer, TMS (tetramethylsilane) as an internal standard in CDCl3. The obtained spectra were then analyzed by using MestReNova. The values of coupling constant were represented in hertz. The multiplicity of peaks were presented by symbols ‘s’ (singlet), ‘d (doublet)’ ‘dd (doublet of doublet)’ & ‘m (multiplet)’. The newly prepared naphthofuran derivatives were purified by using column chromatography.

4.2. General synthetic protocol

To a mixture of 5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol 17 (65 mg, 0.18 mmol) in dimethylformamide (5 mL), potassium carbonate (29 mg, 0.2 mmol), KI (5.3 mg, 0.03 mmol) and CTAB (3.2 mg, 0.009 mmol) were added. Then, the diversely substituted bromoacetanilides 19 (0.19 mmol) were introduced to the reaction mixture, which was sonicated at 80 °C for about 20 min to one an hour. The completion of the reaction was verified by carrying out thin layer chromatography. After confirmation of completion of the reaction, ice-cold distilled water was added to the reaction mixture. The resulting precipitates were then filtered and purified by column chromatography.

4.2.1. N-(4-butylphenyl)-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20a

Off-white powder; 84%; Rf: 0.45 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 220–225 °C 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 1.26–1.35 (m, 2H), 1.54 (q, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 2.54 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.42–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.51–7.57 (m, 4H), 7.62–7.75 (m, 4H), 7.875 (dd, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 10.23 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 13.9, 22.2, 33.6, 35.0, 36.2, 107.0, 112.2, 119.6, 119.7, 122.8, 123.0, 125.2, 126.9, 127.3, 127.4, 127.6, 128.7, 128.7, 128.7, 128.9, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 131.1, 132.8, 135.8, 138.9, 141.4, 148.3, 152.9, 154.2, 166.0; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C32H28N4O2S is 532.1; found: 532.9 [M+].

4.2.2. N-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20b

White coarse solid; 74%, Rf: 0.79 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 236–240 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.29 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 7.43–7.56 (m, 5H), 7.62–7.78 (m, 5H), 7.88 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 9.64 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 18.0, 21.1, 36.0, 107.5, 112.2, 122.7, 123.0, 123.1, 125.2, 125.7, 126.3, 126.9, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 127.7, 128.8, 130.2, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 131.2, 132.7, 135.8, 136.1, 141.1, 148.2, 153.0, 154.1, 166.3; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C30H25N4O2S is 505.1; found: 505.2 [M+ + H].

4.2.3. N-ethyl-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20c

Off-white solid; 84%; Rf: 0.19 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 206–208 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.15 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 3.26–3.33 (m, 2H), 3.84 (s, 2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.60–7.67 (m, 4H), 7.725 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 7.85–7.90 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz); δ 14.5, 34.8, 35.1, 106.6, 112.2, 112.8, 123.1, 125.1, 126.8, 125.5, 130.3, 130.4, 131.0, 133.0, 141.8, 148.4, 152.8, 153.7, 168.1; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C24H21N4O2S is 429.1; found: 429.0 [M+ + H].

4.2.4. N-(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20d

Brown coarse solid; 92%; Rf: 0.28 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1) mp 188–191 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 4.15 (s, 2H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (s, 1H), 7.43–7.73 (m, 9H), 7.89 (s, 2H), 8.04 (s, 1H), 9.65 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 36.3, 55.7, 56.6, 106.3, 107.4, 109.0, 111.1, 112.2, 122.8, 123.2, 125.2, 126.9, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 127.5, 128.4, 128.8, 130.2, 130.2, 130.4, 131.0, 132.9, 141.4, 142.9, 148.1, 152.9, 153.3, 153.6, 166.0; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C30H24N4O4S is 536.1; found: 536.9 [M+].

4.2.5. 2-((5-(Naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)-N-(p-tolyl)acetamide 20e

Light brown solid; 88%; Rf: 0.45 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 210–214 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.28 (s, 3H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 6.95 (s, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.41–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.54 (d, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 7.61–7.70 (m, 4H), 7.74 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (q, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 10.23 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 20.8, 36.2, 106.8, 112.2, 119.6, 119.7, 122.81, 123.0, 125.2, 126.8, 127.3, 127.4, 127.6, 128.9, 129.3, 129.3, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 130.4, 131.1, 132.9, 133.8, 135.6, 141.5, 148.3, 152.9, 154.2, 166.1; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C29H22N4O2S is 490.1; found: 490.9 [M+].

4.2.6. N-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20f

Off-white solid; 76%; Rf: 0.44 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 232–236 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 4.19 (s, 2H), 7.03 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (dd, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.61–7.68 (m, 4H), 7.73 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.28 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 9.84 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 36.0, 100.7, 112.2, 122.4, 122.8, 122.8, 123.1, 125.1, 125.2, 126.9, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 128.8, 128.8, 128.7, 129.3, 129.3, 130.3, 130.3, 130.3, 130.4, 131.1, 144.6, 145.4, 148.1, 153.0, 166.6; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C28H20ClN4O2S is 511.0; found: 511.1 [M+ + H].

4.2.7. N-(2-methoxyphenyl)-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20g

Off-white powder: 79%, Rf: 0.41(n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 197–199 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.95 (s, 3H), 4.16 (s, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.43–7.56 (m, 5H), 7.62–7.74 (m, 4H), 7.90 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.30 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 9.65 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 36.5, 56.0, 107.4, 110.2, 112.2, 120.1, 120.7, 122.8, 123.2, 124.1, 125.2, 126.9, 127.3, 127.5, 127.5, 127.5, 127.7, 128.8, 128.8, 130.3, 130.3, 130.3, 130.4, 131.0, 132.9, 141.5, 148.7, 152.9, 166.0; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C29H22N4O3S is 506.1; found: 506.9 [M+].

4.2.8. N-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20h

Tan/light brown solid; 80%, Rf: 0.57 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 229–232 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 4.15 (s, 2H), 6.97 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (s, 1H), 7.46–7.56 (m, 5H), 7.6525 (dd, J = 4 Hz, 4H), 7.7275 (dd, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 10.54 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 36.4, 108.1, 112.1, 115.3, 115.5, 121.4, 122.7, 123.0, 125.3, 127.0, 127.3, 127.3, 127.3, 128.1, 128.9, 128.9, 130.4, 130.5, 130.5, 130.5, 131.4, 132.4, 134.2, 141.6, 147.4, 152.1, 153.1, 165.7; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C28H19FN4O2S is 494.1; found: 494.9 [M+].

4.2.9. 1-Morpholino-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)ethanone 20i

Lemon yellow solid; 77%; Rf: 0.09 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 140–143 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.61–3.75 (m, 8H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 7.12 (s, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.44–7.56 (m, 5H), 7.61–7.68 (m, 3H), 7.725 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 42.5, 46.6, 46.6 66.6, 66.6, 107.5, 112.2, 112.8, 123.1, 125.2, 126.9, 127.3, 127.5, 127.5, 127.6, 128.8, 130.3, 130.3, 130.3, 130.4, 131.1, 132.8, 141.2, 147.7, 153.0, 165.3; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C26H23N4O3S is 471.1; found: 471.2 [M+ + H].

4.2.10. N,N-diethyl-2-((5-(naphtho[2,1-b]furan-2-yl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)thio)acetamide 20j

Brown solid; 80%; Rf: 0.16 (n-hexane/ethylacetate 1 : 1); mp 130–132 °C. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.12 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 1.25 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 3.36–3.48 (m, 4H), 4.41 (s, 2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 7.41–7.47 (m, 3H), 7.52–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.57–7.64 (m, 3H), 7.71 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz); δ 12.8, 14.3, 37.1, 40.7, 42.6, 106.2, 112.3, 122.9, 123.1, 125.0, 126.7, 127.1, 127.4, 127.5, 127.5, 127.5, 128.8, 130.1, 130.1, 130.4, 130.6, 142.3, 148.0, 152.7, 153.4, 165.9; LC-MS(ESI) (m/z) calculated for C26H24N4O2S is 456.1; found: 456.2 [M+].

4.3. Biological evaluation

The isolation and purification of bacterial tyrosinase enzyme were carried out using previously developed protocols.69,70 To investigate the tyrosinase inhibitory potential of synthesized naphthofuran-based derivatives, spectroscopic methodology was exploited to examine their respective IC50 values via reported methods.71 For inhibition analysis, 2 mM l-tyrosine (765 μL), buffer solution (phosphate buffer solution of pH = 6.8, 0.05 mM), along with 35 μL of the test compound (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide) were placed in an incubator under favorable temperature conditions for almost 10 minutes. This step was followed by the addition of 200 μL of isolated bacterial tyrosinase enzyme. The test sample was subjected to incubation at 37 °C in comparison to the control and blank sample. After incubation, the inhibition potential of the synthesized derivatives was ascertained at 475 nm. The increased level of dopachrome was further investigated by measuring the absorbance at 475 nm wavelength, thereby determining the tyrosinase inhibition activity. The inhibition potential was illustrated by determining the percentage inhibition and IC50 values (obtained by extrapolation of the graph). The interpreted results were then critically compared with those of the standard inhibitors.

The percentage inhibition all synthesized derivatives was interpreted by given formula:Percentage inhibition = (absorbance of blank − absorbance of sample/absorbance of control blank) × 100

4.4. Kinetic studies

The kinetic studies of the most potent derivative 20f were carried out by utilizing diverse concentrations of tyrosine substrate (0.1, 0.2, 0.3 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 & 1 mM) and optimized concentration of inhibitor 20f (100 μL). The time duration for pre-incubation and measurement was exactly similar to the one mentioned in the biological evaluation for the tyrosinase inhibition assay. The value of the maximum initial velocity was inferred by the initial linear duration of absorbance up to 5 min, upon the introduction of enzyme at the interval of fifteen seconds. The type of enzyme inhibition was investigated by Lineweaver–Burk plot, which was obtained by plotting the inverse of velocities (1/V) against the inverse of substrate concentrations (1/[S]) mM−1. In addition, EI (Ki) and ESI  dissociation constant values were attained by the secondary plot of the slope and intercept versus the inhibitor concentration, respectively. The Dixon plot was also plotted to confirm the type of inhibition.

dissociation constant values were attained by the secondary plot of the slope and intercept versus the inhibitor concentration, respectively. The Dixon plot was also plotted to confirm the type of inhibition.

4.5. Molecular docking studies

The compounds (20f & 20i) with lower IC50 values were selected for induced fit docking. All the docking analysis was performed in Molecular Operating Environment (MOE 2015).72 The targeted compounds were prepared in ChemDraw software. The standard kojic acid (CID: 3840) structure was acquired from PubChem. The tyrosinase crystallized structure (5OAE) was downloaded from the Protein data bank (PDB),73 and used as a receptor in the IFD docking. The protein and ligand structures were prepared by using QuickPrep tool of MOE. The default Amber10:EHT forcefield with gradient 0.1 was used to energy minimize the docking ligands. Induced Fit refinement, Triangular Matcher placement, London-dG, and GBVI/WSA scoring were all used for screening. The native ligand was subjected to cognate redocking in order to validate the docking protocol. The ligand–protein interaction analysis was performed in BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2024.

4.6. ADMET analysis

All of the novel naphthofuran-triazole conjugates were subjected to ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity) analysis by using online software ADMETLab 3.0.74 The SMILES of compounds were generated by drawing the structures of derivatives on an online server, and the resulting smiles were run for ADMET evaluation.

Data availability

All data are included in the manuscript and ESI files.†

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest for this research work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the Researchers supporting project number (RSPD2024R740), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra05649c

References

- Tief K. Hahne M. Schmidt A. Beermann F. Tyrosinase, the key enzyme in melanin synthesis, is expressed in murine brain. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;241:12–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0012t.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes C. S., and Vogel K., Tyrosinases—Physiology, pathophysiology, and applications, in Enzymes in Human and Animal Nutrition, Academic Press, 2018, pp. 403–412 [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T. Nakashima A. Watanabe H. Ito S. Wakamatsu K. Neuromelanin in Parkinson's disease: tyrosine hydroxylase and tyrosinase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:4176. doi: 10.3390/ijms23084176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marieshwari B. N. Bhuvaragavan S. Sruthi K. Mullainadhan P. Janarthanan S. Insect phenoloxidase and its diverse roles: Melanogenesis and beyond. J. Comp. Physiol., B. 2023;193:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s00360-022-01468-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K.-K. Huang H. Han P. Zhang C.-L. Shi Y. Chen Q.-X. Inhibitory effects of cis-and trans-isomers of 3, 5-dihydroxystilbene on the activity of mushroom tyrosinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;342:1147–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passi S. Nazzaro-Porro M. Molecular basis of substrate and inhibitory specificity of tyrosinase: phenolic compounds. Br. J. Dermatol. 1981;104:659–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenoll L. G. Penalver M. J. Rodrıguez-López J. N. Varón R. Garcıa-Cánovas F. Tudela J. Tyrosinase kinetics: discrimination between two models to explain the oxidation mechanism of monophenol and diphenol substrates. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;36:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai X. Wichers H. J. Soler-Lopez M. Dijkstra B. W. Structure and function of human tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related proteins. Chem.–Eur. J. 2018;24:47–55. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerch K. Molecular and active site structure of tyrosinase. Life Chem. Rep. 1987;5:221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M. Hearing V. J. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008;84:539–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casañola-Martín G. M. Marrero-Ponce Y. Khan M. T. H. Ather A. Khan K. M. Torrens F. Rotondo R. Dragon method for finding novel tyrosinase inhibitors: Biosilico identification and experimental in vitro assays. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007;42:1370–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nihei K. I. Yamagiwa Y. Kamikawa T. Kubo I. 2-Hydroxy-4-isopropylbenzaldehyde, a potent partial tyrosinase inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;14:681–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorga S. Sarangal R. Pigmentary disorders: an insight. Pigment Int. 2014;1:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z. P. Cheng K. W. Chao J. Wu J. Wang M. Tyrosinase inhibitors from paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera) Food Chem. 2008;106:529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. Food browning and its prevention: an overview. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996;44:631–653. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell R. F., and Finot P. A., Nutritional consequences of the reactions between proteins and oxidized polyphenolic acids, in Nutritional and Toxicological Aspects of Food Safety, Springer, Boston, MA, US, 1984, pp. 423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J. Uyama H. Tyrosinase inhibitors from natural and synthetic sources: structure, inhibition mechanism and perspective for the future. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1707–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germanas J. P. Wang S. Miner A. Hao W. Ready J. M. Discovery of small-molecule inhibitors of tyrosinase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:6871–6875. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao N. W. Tseng T. S. Lee Y. C. Chen W. C. Lin H. H. Chen Y. R. Wang Y. T. Hsu H. J. Tsai K. C. Serendipitous discovery of short peptides from natural products as tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:3099–3111. doi: 10.1021/ci500370x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. T. Yager J. W. Steinmetz K. L. Eastmond D. A. Peroxidase – dependent metabolism of benzene's phenolic metabolites and its potential role in benzene toxicity and carcinogenicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 1989;82:23–29. doi: 10.1289/ehp.898223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. T. H. Novel tyrosinase inhibitors from natural resources–their computational studies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:2262–2272. doi: 10.2174/092986712800229041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T. S. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009;10:2440–2475. doi: 10.3390/ijms10062440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterov A. Zhao J. Jia Q. Natural tyrosinase inhibitors for skin hyperpigmentation. Drugs Future. 2008;33:945–954. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez S. Kang M. Chung H. S. Bae H. Naturally occurring tyrosinase inhibitors: mechanism and applications in skin health, cosmetics and agriculture industries. Phytother. Res. 2007;21:805–816. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. T. H. Molecular design of tyrosinase inhibitors: A critical review of promising novel inhibitors from synthetic origins. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007;79:2277–2295. [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. T. H. Heterocyclic compounds against the enzyme tyrosinase essential for melanin production: biochemical features of inhibition. Bioact. Heterocycl. 2007;III:119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Rescigno A. Sollai F. Pisu B. Rinaldi A. Sanjust E. Tyrosinase inhibition: general and applied aspects. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2002;17:207–218. doi: 10.1080/14756360210000010923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia L. Idhayadhulla A. Lee Y. R. Wee Y.-J. Kim S. H. Anti-tyrosinase, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities of novel 5-hydroxy-4-acetyl-2, 3-dihydronaphtho [1, 2-b] furans. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;86:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava V. Negi A. S. Kumar J. K. Faridi U. Sisodia B. S. Darokar M. P. Luqman S. Khanuja S. P. S. Synthesis of 1-(3′,4′,5′-trimethoxy) phenyl naphtho [2, 1b] furan as a novel anticancer agent. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:911–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.10.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venegas W. Sala M. Buisson J. P. Royer R. Chouroulinkov I. Relationship between the chemical structure and the mutagenic and carcinogenic potentials of five naphthofurans. Cancer Res. 1984;44:1969–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRILMIŞ C. Koca M. Servi S. Gür S. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of dinaphtho [2, 1-b] furan-2-yl-methanone and their oxime derivatives. Turk. J. Chem. 2009;33:375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini S. Coppey J. Buisson J. P. Royer R. Inhibition of DNA synthesis in relation to enhanced survival of UV-damaged herpes virus in monkey cells treated by a variety of 2-nitronaphthofurans. Mutat. Res., Genet. Toxicol. 1981;90:125–135. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(81)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mone N. S. Bhagwat S. A. Sharma D. Chaskar M. Patil R. H. Zamboni P. Nawani N. N. Satpute S. K. Naphthoquinones and their derivatives: emerging trends in combating microbial pathogens. Coatings. 2021;11:434. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. Chen Q. Q. Huang Y. Li K. H. Geng X. J. Wang T. Lin Q.-S. Yao R. S. Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of naphthofuran derivatives as potent SIRT1 activators. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:653233. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.653233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan K. M. Padmashali B. Vaidya V. P. Studies in naphthofurans: Part V-synthesis of 2-aryl-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrahydropyrido (naphtho [2, 1-b] furan)-4-ones and their biological activity. Indian J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2001;11:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Idhayadhulla A. Xia L. Lee Y. R. Kim S. H. Wee Y. J. Lee C. S. Synthesis of novel and diverse mollugin analogues and their antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Bioorg. Chem. 2014;52:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenchappa R. Bodke Y. D. Synthesis, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of benzofuran pyrazole heterocycles. Chem. Data Collect. 2020;28:100453. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C.-Y. Tsai P.-C. Tseng C.-H. Chen Y. Chang L.-S. Lin S.-R. Inhibition of EGF/EGFR activation with naphtho [1, 2-b] furan-4, 5-dione blocks migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2013;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumb J. P. Trauner D. Biomimetic synthesis and structure elucidation of Rubicordifolin, a cytotoxic natural product from Rubia cordifolia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2870–2871. doi: 10.1021/ja042375g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles D. H. Lho D. S. De la Cruz A. A. Gomez E. D. Weeks J. A. Atwood J. L. Toxicants from mangrove plant. 3. Heritol, a novel ichthyotoxin from the mangrove plant Heritiera littoralis. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:2930–2932. [Google Scholar]

- Zubaidha P. K. Chavan S. P. Racherla U. S. Ayyangar N. R. Synthesis of (±)heritol. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:5759–5768. [Google Scholar]

- Irie H. Matsumoto R. Nishimura M. Zhang Y. Synthesis of (±)-Heritol, a Sesquiterpene Lactone belonging to the Aromatic Cadinane Group. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1990;38:1852–1856. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann F. Zdero C. Natürlich vorkommende Terpen-Derivate, 80. Einige Inhaltsstoffe der Gattung Chromolaena. Chem. Ber. 1977;110:487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro K. Ohira Y. Oku H. Antipruritic dinaphthofuran-7,12-dione derivatives from the pericarp of Impatiens balsamina. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:1126–1129. doi: 10.1021/np9704718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelwahab A. H. F. Fekry S. A. H. Synthesis, reactions and applications of naphthofurans: A review. Eur. J. Chem. 2021;12:340–359. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Tang Y. Mao B. Li W. Jin H. Zhang L. Liu Z. Discovery of N-(Naphtho [1, 2-b] Furan-5-Yl) benzenesulfonamides as novel selective inhibitors of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) Molecules. 2018;23:678. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang D. K. Kaur R. Arora R. Saini B. Arora S. Nitrogen-containing heterocycles as anticancer agents: An overview. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020;20:2150–2168. doi: 10.2174/1871520620666200705214917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahoor A. F. Yousaf M. Siddique R. Ahmad S. Naqvi S. A. R. Rizvi S. M. A. Synthetic strategies toward the synthesis of enoxacin-, levofloxacin-, and gatifloxacin-based compounds: A review. Synth. Commun. 2017;47:1021–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Kerru N. Gummidi L. Maddila S. Gangu K. K. Jonnalagadda S. B. A review on recent advances in nitrogen-containing molecules and their biological applications. Molecules. 2020;25:1909. doi: 10.3390/molecules25081909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faiz S. Zahoor A. F. Ring opening of epoxides with C-nucleophiles. Mol. Diversity. 2016;20:969–987. doi: 10.1007/s11030-016-9686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P. K. Silakari O. The current status of O-heterocycles: A synthetic and medicinal overview. ChemMedChem. 2018;13:1071–1087. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201800119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S. Zahoor A. F. Naqvi S. A. R. Akash M. Recent trends in ring opening of epoxides with sulfur nucleophiles. Mol. Diversity. 2018;22:191–205. doi: 10.1007/s11030-017-9796-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathare B. Bansode T. Biological active benzimidazole derivatives. Results Chem. 2021;3:100200. [Google Scholar]

- Garg S. S. Gupta J. Sharma S. Sahu D. D. An insight into the therapeutic applications of coumarin compounds and their mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;152:105424. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanam H. Bioactive Benzofuran derivatives: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;97:483–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Wahab B. F. Shaaban S. Thiazolothiadiazoles and thiazolooxadiazoles: synthesis and biological applications. Synthesis. 2014;46:1709–1716. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya A. Jain S. Jain P. Jain P. Tiwari N. Jain R. Jain R. Jain A. K. K Agrawal R. K. Synthesis and biological activities of oxadiazole derivatives: a review. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2016;16:825–845. doi: 10.2174/1389557516666160211120835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathi A. K. Syed R. Shin H. S. Patel R. V. Piperazine derivatives for therapeutic use: a patent review (2010-present) Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016;26:777–797. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2016.1189902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salma U. Ahmad S. Alam M. Z. Khan S. A. A review: Synthetic approaches and biological applications of triazole derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1301:137240. [Google Scholar]

- Koparde S. Hosamani K. M. Kulkarni V. Joshi S. D. Synthesis of coumarin-piperazine derivatives as potent anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory agents, and molecular docking studies. Chem. Data Collect. 2018;15:197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Singh D. K. Iqbal H. Ansari M. Recent Progress in the Synthesis and Biological Assessment of Benzimidazole-1,2,3-Triazole Hybrids. Curr. Org. Chem. 2024;28:733–756. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan A. Faisal S. Ahmad S. Al-Hussain S. A. Javed S. Zahoor A. F. Parveen B. Zaki M. E. Structure-based virtual screening of furan-1,3,4-oxadiazole tethered N-phenylacetamide derivatives as novel class of hTYR and hTYRP1 inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:344. doi: 10.3390/ph16030344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahoor A. F. Hafeez F. Mansha A. Kamal S. Anjum M. N. Raza Z. Khan S. G. Javid J. Irfan A. Bhat M. A. Bacterial tyrosinase inhibition, hemolytic and thrombolytic screening, and in silico modeling of rationally designed tosyl piperazine-engrafted dithiocarbamate derivatives. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2739. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11102739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed S. Saif M. J. Zahoor A. F. Tabassum H. Kamal S. Faisal S. Ashraf R. Khan S. G. Nazeer U. Irfan A. Bhat M. A. Discovery of novel 1, 2, 4-triazole tethered β-hydroxy sulfides as bacterial tyrosinase inhibitors: synthesis and biophysical evaluation through in vitro and in silico approaches. RSC Adv. 2024;14:15419–15430. doi: 10.1039/d4ra01252f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausar R. Zahoor A. F. Tabassum H. Kamal S. Ahmad Bhat M. Synergistic biomedical potential and molecular docking analyses of coumarin–triazole hybrids as tyrosinase inhibitors: design, synthesis, in vitro profiling, and in silico studies. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17:532. doi: 10.3390/ph17040532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faiz S. Zahoor A. F. Ajmal M. Kamal S. Ahmad S. Abdelgawad A. M. Elnaggar M. E. Design, synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation, and laccase catalysis effect of novel benzofuran–oxadiazole and benzofuran–triazole hybrids. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2019;56:2839–2852. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir S. B. Cebeci Y. U. Bayrak H. Mermer A. Ceylan S. Demirbas A. Karoaglu S. A. Demirbas N. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of new piperazine-based heterocyclic compounds. Heterocycl. Commun. 2017;23:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed S. Shahzadi I. Zahoor A. F. Al-Mutairi A. A. Kamal S. Faisal S. Irfan A. Al-Hussain S. A. Muhammed M. T. Zaki M. E. Exploring theophylline-1, 2, 4-triazole tethered N-phenylacetamide derivatives as antimicrobial agents: unraveling mechanisms via structure–activity relationship, in vitro validation, and in silico insights. Front. Chem. 2024;12:1372378. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2024.1372378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed E. A. Danial E. N. Isolation, Identification and Medium Optimization for Tyrosinase Production by a Newly Isolated Bacillus subtilis NA2 Strain. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2018;8:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain F. Kamal S. Rehman S. Azeem M. Bibi I. Ahmed T. Iqbal H. Alkaline Protease Production Using Response Surface Methodology, Characterization and Industrial Exploitation of Alkaline Protease of Bacillus subtilis sp. Catal. Lett. 2017;147:1204–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H. Yoon J.-Y. Yang S. Y. Choi S.-K. Kwon S. J. Cho I. S. Jeong M. H. Ho Kim Y. Choi G. S. Tyrosinase inhibitory components from Aloevera and their antiviral activity. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017;32:78–83. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1235568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H. Tran L. M. Stang J. L. Induced-fit Docking Studies of the Active and Inactive States of Protein Tyrosine Ki-nases. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2009;28:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismaya W. T. Rozeboom H. J. Weijn A. Mes J. J. Fusetti F. Wichers H. J. Dijkstra B. W. Crystal Structure of Agaricus Bisporus Mushroom Tyrosinase: Identity of the Tetramer Subunits and Interaction with Tropolone. Biochem. 2011;50:5477–5486. doi: 10.1021/bi200395t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L. Shi S. Yi J. Wang N. He Y. Wu Z. Peng J. Deng Y. Wang W. Wu C. Lyu A. Zeng X. Zhao W. Hou T. Cao D. ADMETlab 3.0: an updated comprehensive online ADMET prediction platform enhanced with broader coverage, improved performance, API functionality and decision support. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52:W422–W431. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and ESI files.†