ABSTRACT:

Repetitive physical exercise induces physiological adaptations in skeletal muscle that improves exercise performance and is effective for the prevention and treatment of several diseases. Genetic evidence indicates that the orphan nuclear receptors estrogen receptor-related receptors (ERRs) play an important role in skeletal muscle exercise capacity. Three ERR subtypes exist (ERRα, β, and γ), and although ERRβ/γ agonists have been designed, there have been significant difficulties in designing compounds with ERRα agonist activity. Additionally, there are limited synthetic agonists that can be used to target ERRs in vivo. Here, we report the identification of a synthetic ERR pan agonist, SLU-PP-332, that targets all three ERRs but has the highest potency for ERRα. Additionally, SLU-PP-332 has sufficient pharmacokinetic properties to be used as an in vivo chemical tool. SLU-PP-332 increases mitochondrial function and cellular respiration in a skeletal muscle cell line. When administered to mice, SLU-PP-332 increased the type IIa oxidative skeletal muscle fibers and enhanced exercise endurance. We also observed that SLU-PP-332 induced an ERRα-specific acute aerobic exercise genetic program, and the ERRα activation was critical for enhancing exercise endurance in mice. These data indicate the feasibility of targeting ERRα for the development of compounds that act as exercise mimetics that may be effective in the treatment of numerous metabolic disorders and to improve muscle function in the aging.

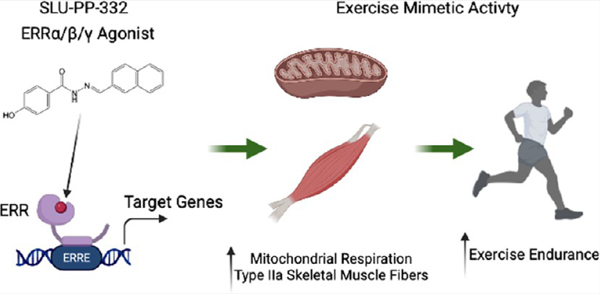

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Lack of physical activity is a substantial contributor to the development and progression of chronic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, dementia, and cancer.1 Exercise is an effective treatment for many chronic diseases, including obesity and type 2 diabetes,2 and when exercise is combined with dietary modifications, this treatment can be more effective than currently available pharmacological therapies.3 Even a single bout of exercise improves whole-body insulin sensitivity for up to 48 h after exercise cessation.4 Furthermore, a single bout of exercise can increase basal energy expenditure beyond the point of exercise termination.5 Physical exercise is generally classified as either aerobic (endurance-based high-frequency repetition with relatively low load) or anaerobic exercise (resistance, strength-based low-frequency repetition with relatively high load). The skeletal muscle is one of the primary tissues that adapt to exercise in order to physically and metabolically acclimatize to the increase in utilization. Physical exercise triggers dramatic changes in skeletal muscle gene and protein expression that drive these physiological adaptations. Exercise provides for improved muscle function (strength), and endurance can be detected after single bouts of exercise (acute exercise) and repeated bouts of exercise (training).6 Both aerobic and anaerobic/resistance exercise are effective in preventing and treating obesity and diabetes, but each induces distinct physiological adaptations within the skeletal muscle. One of the key adaptations of skeletal muscle that occurs in response to aerobic exercise is an increased oxidative capacity of the tissue via elevated mitochondrial respiratory capacity, which allows for more efficient energy production and improved exercise endurance.7

The estrogen receptor-related orphan receptors (ERRα, ERRβ, and ERRγ) were the first orphan nuclear receptors to be identified.8 As their moniker indicates, they are homologous to estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ); however, they do not bind endogenous ER ligands. While ERs require ligand binding to display transcriptional activity, all three ERRs exhibit ligand-independent constitutive transcriptional activation activity.9 ERRs are highly expressed in tissues with high energy demand such as skeletal muscle, heart, brain, adipose tissue, and liver.8,10,11 A range of target genes whose transcription is activated by ERRs have been identified that includes enzymes and regulatory proteins in energy production pathways involved in fatty acid oxidation, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, mitochondrial biogenesis, and oxidative phosphorylation.12,13

Although the ERRα-null mice are susceptible to heart failure under stress,14 they can be maintained to investigate ERRα function. A skeletal muscle-specific deletion of ERRα yielded mice that displayed reduced mitochondrial biogenesis and impaired repair.15 A later study using the whole-body ERRα-null mice showed that they had decreased muscle mass and decreased exercise endurance that was associated with impaired metabolic transcriptional programs in the skeletal muscle.16 A genetic gain of function mouse model with ERRγ overexpressed in the skeletal muscle is consistent with these data, with the mice displaying increased mitochondrial biogenesis and lipid oxidation.17 Interestingly, these mice also displayed an increase in oxidative muscle fibers and increased exercise endurance without endurance training.17 Rangwala et al. reported similar results with overexpression of ERRγ in muscle, and additionally, this group also demonstrated that loss of one copy of ERRγ resulted in decreased exercise capacity and mitochondrial function.18 ERRβ levels are considerably lower than either ERRα or ERRγ in skeletal muscle, and thus ERRβ appears to have minimal, if any, relevance in this tissue.19

It has been suggested that ERRα is an intractable drug target based on the collapsed putative ligand binding pocket and lack of success of several high-throughput screening campaigns as well as the failures of structure-based drug design efforts based on the homology of ERRα to ERRγ.20 Based on the observation that skeletal muscle-specific ERRα KO mice as well as the ERRα inverse agonist-treated mice display decreased exercise tolerance,16 we sought to identify ERRα agonists that might act as exercise mimetics.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of SLU-PP-332 as a Novel Pan ERR Agonist with Potent ERRα Activity.

The identification of the compound C29 as an ERRα inverse agonist21,22 suggested that ERRα may not be an intractable drug target. However, as an inverse agonist, C29 acts to block the constitutive transcriptional activation activity of ERRα, and it is uncertain if one could design a small molecule that could act as an ERRα agonist enhancing the strong constitutive activity of the receptor.

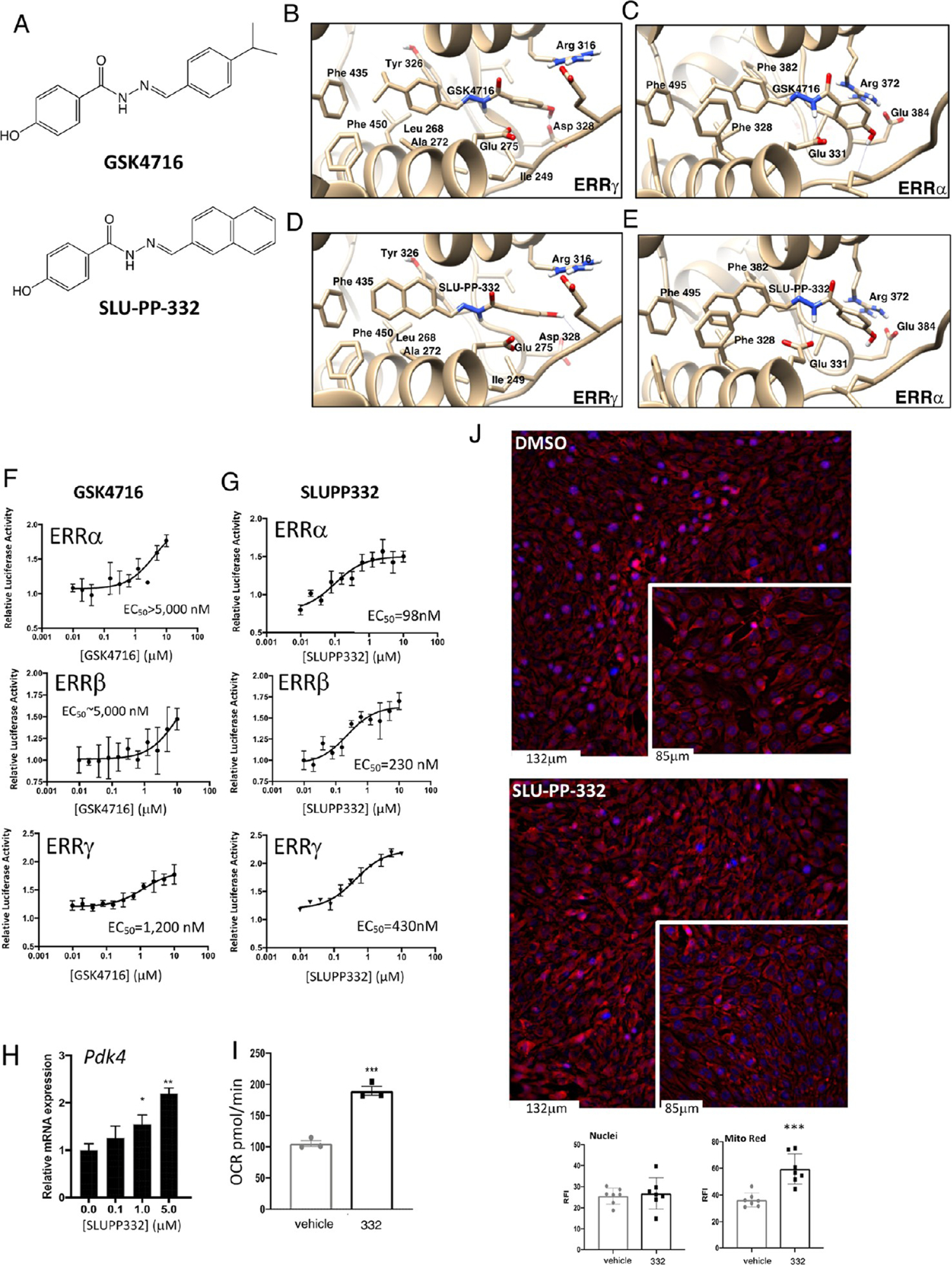

Using a rational drug design approach, we optimized the ERRβ/γ selective agonist scaffold, GSK4716, for ERRα activity and gained 50-fold ERRα potency. We utilized the X-ray crystal structure of the ligand binding domain (LBD) of ERRγ bound to GSK4716 (Figures 1A,B and S1) (PDB ID: 2GPP)23 and subsequently modeled GSK4716 bound to the LBD ERRα in order to assess how we might optimize such binding to design an ERRα agonist (Figure 1C). In contrast to the first report of GSK4716 displaying no ERRα activity, we observed very weak agonist activity in an ERR cotransfection assay (Figure 1F) and believed that the GSK4716 scaffold may be useful as an initiation point to develop high-affinity ERRα agonists. The X-ray structure of ERRγ LBD bound to GSK4716 is the only X-ray crystal structure for any ERR bound with an agonist ligand (Figure 1B).23 In this structure, the agonist GSK4716 binds in a previously unidentified pocket dubbed the “agonist” pocket near the solvent-exposed surface of the receptor (Figure S1).23 The phenolic hydroxyl group of GSK4716 interacts with Asp328 (Figure 1B) while the carbonyl of the acyl hydrazone bridges to two water molecules, one of which interacts with Arg316 and the other water molecule interacts with Leu309 (Figure S1). Molecular modeling of GSK4716 in the LBD of ERRα followed by energy minimization to refine the protein–ligand complexes reveals similar interactions to that observed with ERRγ X-ray crystal structure (Figure 1C). Our strategy to design high-affinity ERRα agonists was based on optimizing ligand interactions with Phe328 that is specifically in ERRα. We employed a strategy to optimize GSK4716 based on converting the isopropyl phenyl group of GSK4716 to a more hydrophobic moiety that could potentially gain affinity by interacting with the Phe328 in ERRα. Molecular modeling of a compound with a naphthalene substituent in place of the isopropyl phenyl group (SLU-PP-332; Figure 1A bottom and Figures 1C, S1, and S2) in the LBD of ERRγ and ERRα predicted the newly added phenyl group to make π–π interactions with Phe435 (ERRγ) or Phe495 and Phe328 (ERRα). We hypothesized that this modification would improve the affinity of the ligand in both receptors, but particularly toward ERRα due to a potential π–π stacking interaction between the ligand naphthalene group and Phe328 (the corresponding alanine residue in ERRβ and ERRγ is unable to make such interactions). As predicted, SLU-PP-332 gained substantial ERRα potency vs GSK4716 in addition to a moderate increase in potency for ERRγ in a full-length ERR cell-based cotransfection/reporter assay (Figure 1F vs Figure 1G) (SLU-PP-332: ERRα EC50 = 98 nM, ERRβ = 230 nM, ERRγ = 430 nM vs GSK4716: ERRα EC50 > 5000 nM, ERRβ > 5000 nM, ERRγ = 1200 nM). SLU-PP-332 displayed a degree of ERRα selectivity with 4.4-fold selectivity for ERRα over ERRγ and 2.3-fold ERRα over ERRβ. SLU-PP-332 also displayed activity at all ERRs in a Gal4-ERR LBD chimeric cotransfection assay, and similar to the full-length ERR cotransfection assays, SLU-PP-332 was more potent at ERRα than ERRβ and ERRγ (Figure S3A). SLU-PP-332 was selective for the ERRs as it did not alter the activity of either ERα or ERβ, or other nuclear receptors in cotransfection assays (Figure S3B). Direct binding of SLU-PP-332 to ERRα was confirmed by limited proteolysis, where the LBD is subjected to chymotrypsin in the presence and absence of SLU-PP-332, and the ability of the drug to “protect” fragments of the LBD from digestion due to a conformational change in the LBD is detected.24–26 As shown in Figure S3C, SLU-PP-332 dosedependently protects a fragment of the ERRα from protease digestion, consistent with direct binding of the drug to ERRα. Direct binding of SLU-PP-332 to ERRγ was also confirmed using differential scanning fluorimetry, where the compound dose-dependently increased the thermal stability of the purified ERRγ LBD (Figure S3D). Unfortunately, ERRα did not function well in the differential scanning fluorimetry assay, and ERRγ did not function in the limited proteolysis assay, and thus we were unable to obtain biochemical data from these two receptors in the identical biochemical assay. Although it is not clear why both receptors did not function in the same biochemical assay, we have observed for a number of nuclear receptors that they do necessarily function well in these biochemical assay formats. As described in our introduction, the compound C29 (Figure S3E top) has been identified as an ERRα selective inverse agonist, and we assessed its activity in the full-length ERR cotransfection assay in order to compare it to SLU-PP-332.21,22 C29 did indeed display ERRα selective inverse agonist activity with an IC50 of 60 nM (Figure S3E). C29 behaved as a partial inverse agonist with the ability to reduce the endogenous activity of ERRα by approximately 40% compared to ERR inverse agonist XCT79027 (∼65% inhibition; Figure S3F). We also detected some ERRβ inverse agonist activity of C29 that was potent (IC50 = 340 nM) but was relatively low efficacy (∼20% inhibition). C29 activity was minimal on ERRγ, and we assessed the activity of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT), a well-characterized ERRγ inverse agonist,28 as a comparator, where it inhibited ERRγ constitutive activity by ∼75% with an IC50 of 550 nM (Figure S3G).

Figure 1.

SLU-PP-332 is a Pan ERRα/β/γ agonist with significant ERRα activity. (A) Chemical structures of GSK4716 (top) and SLU-PP-332 (bottom). (B) Schematic illustrating the X-ray co-crystal structure of GSK4716 bound to the ERRγ LBD (PDB ID: 2GPP). Models of ERRα bound to GSK4716 (C), ERRγ LBD bound to GSK4716 (D), and ERRα bound to SLU-PP-332 (E). Results of ERRα, ERRβ, or ERRγ cotransfection assays and full-length ERRs in HEK293 cells illustrating the activity of GSK4716 (F) and SLU-PP-332 (G). (H) Effects of SLU-PP-332 dose–response treatment (24 h) on pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (Pdk4), in C2C12 cells, n = 3. (I) Maximal mitochondrial respiration values analyzed by Seahorse of C2C12 cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (gray bar) or SLU-PP-332 (black bar), n = 3. (J) MitoTracker Red staining of C2C12 cells under proliferative conditions treated with DMSO or SLU-PP-332 (10 μM) for 24 h. Bar graph represents nuclei intensity (left) and MitoTracker Red staining (right). p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.05.

SLU-PP-332 Increases the Expression of an ERR Target Gene and Enhances Mitochondrial Respiration in C2C12 Myocytes.

We next examined whether SLU-PP-332 could increase the expression of an ERR target gene in the C2C12 myoblast cell line. We noted a clear increase in the expression of a well-characterized ERR target gene, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (Pdk4),29–31 with SLU-PP-332 treatment (Figure 1H) with efficacy very similar to that observed in the cotransfection assay (Figure 1G). Overexpression of ERRγ in C2C12 myocytes has been demonstrated to enhance mitochondrial respiration, and pharmacological inhibition of ERRα suppresses mitochondrial respiration in these cells;17,32 thus, we hypothesized that SLU-PP-332 would enhance mitochondrial respiration. Proliferating C2C12 cells treated with SLU-PP-332 for 24 h exhibited an increase in maximum mitochondrial respiration relative to cells treated with vehicle (Figures 1I and S4). Furthermore, we observed that SLU-PP-332 treatment substantially induced mitochondrial biogenesis in proliferating C2C12 cells based on staining with MitoTracker Red (Figure 1J).

SLU-PP-332 Enhances Exercise Endurance in Mice.

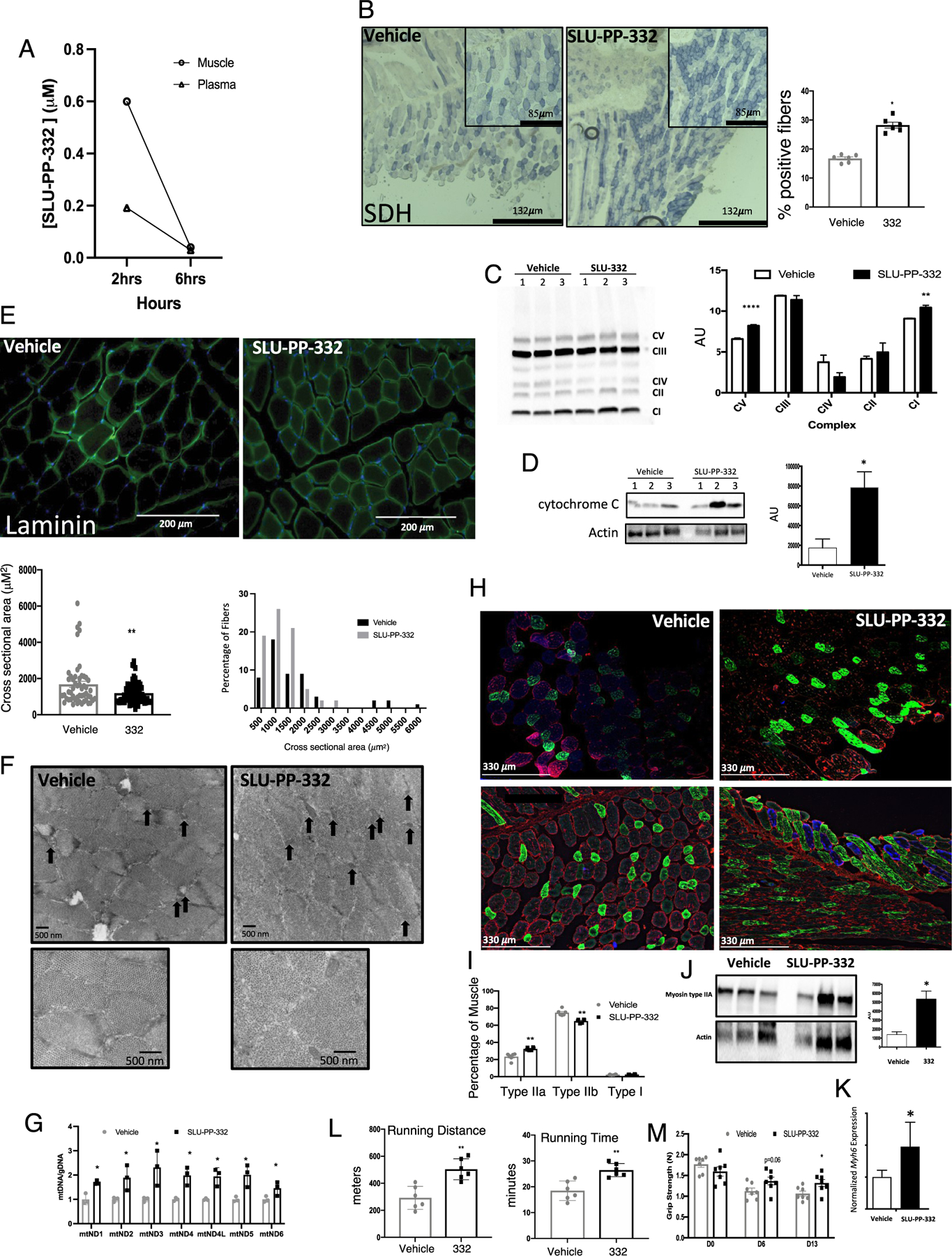

We sought to determine if SLU-PP-332 could potentially be used as a chemical probe to evaluate the activation of ERR function in vivo; thus, we first assessed in vivo exposure after intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration in mice (Figure 2A). Mice were administered SLU-PP-332 (30 mg/kg, i.p.), and plasma and muscle were collected 2- and 6 h post administration and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Two hours after administration, levels of SLU-PP-332 were highest in skeletal muscle (∼0.6 μM), while levels in the plasma were lower (∼0.2 μM) (Figure 2A). We observed no overt toxicity in mice administered SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg b.i.d., i.p.) for 10 days which is consistent with the normal complete blood count and electrolyte levels33 (Table S1). We also observed no significant alterations in serum creatine kinase, suggesting a lack of skeletal muscle toxicity (Figure S5).

Figure 2.

SLU-PP-332 increases oxidative fibers in skeletal muscle and improves exercise endurance. (A) Pharmacokinetic analysis of SLU-PP-332 displaying muscle and plasma levels of the compound at 2 and 6 h post 30 mg/kg, i.p. in 10/10/80 DMSO, Tween, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). n = 3. (B) Immunochemical analysis of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) from quadriceps of mice administered vehicle (white bars, n = 8) or SLU-PP-332 50 mg/kg, b.i.d (black bar, n = 8). The bar graph represents the quantification of SDH-positive muscle fibers. (C) OXPHOS complex blot from quadriceps of mice dosed with vehicle or SLU-PP-332 50 mg/kg, b.i.d (black bar, n = 7). Protein normalization was performed using the Stain-Free Western Workflow suite from Bio-Rad. Relative amount of total protein in each lane on the blot was calculated and used for quantitation normalization. We then identified a band for each OXPHOS complex and then normalized their intensity level to the total protein intensity for each lane. Then, the average and standard deviation were calculated for each group (vehicle and SLU-332). (D) Cytochrome c protein levels from quadriceps from mice dosed with vehicle (white bars, n = 7) or SLU-PP-332 50 mg/kg, b.i.d (black bar, n = 7). The bar graph represents the quantification of expression. Immunochemical analysis of laminin (E), electron microscopy of quadriceps (F) (black arrows illustrate identified mitochondria). (G) Analysis of mitochondrial DNA levels (relative to nuclear DNA) from quadriceps. Immunochemical analysis of muscle fiber types. (H) Stained sections (n = 6 per group) from quadriceps of mice administered vehicle (white bars, n = 8) or SLU-PP-332 50 mg/kg, b.i.d (black bar, n = 8). Myosin IIa is green, myosin IIb is red, and myosin I is blue. The bar graph represents the quantification of fiber cross-sectional area (lower panel) and percentage of fiber types (I). Myosin heavy chain protein (J) and gene (K) expression from quadriceps of mice treated with vehicle or SLU-PP-332 50 mg/kg, b.i.d (n = 6 for gene expression and n = 3 for protein). For (J), myosin IIA protein expression was normalized to actin after imaging and dividing the myosin IIA protein signal to the respective actin signal using ImageJ software. The bar graph represents the quantification of expression. (L) Running distance (left panel) and running time (right panel) of mice treated with an acute dose of vehicle (gray bar) or SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg, black bar) for 1 h before running (n = 6 per group). (M) Grip strength test from mice treated with vehicle (gray bar) or SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg, black bar) before dosing (D0), after 6 days of dosing (D6), or after 13 days (D13) (n = 8). p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

We next examined the effects of chronic SLU-PP-332 treatment on muscle physiology and function. Three-month-old C57BL/6J mice were administered SLU-PP-332 for 15 days (50 mg/kg, b.i.d., i.p.), followed by an examination of quadricep muscle histology. To increase drug exposure in the efficacy studies experiment, we increased the dose to 50 mg/kg. To avoid the effect of ERR on facultative thermogenesis and cold tolerance,34 we maintained the mice at thermoneutrality (30 °C). Histology was performed on unfixed muscle and stained for hematoxylin and eosin (Figure S6A) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity (Figure 2B). Mice treated with SLU-PP-332 displayed a more oxidative muscle phenotype (greater SDH staining) (Figure 2B). We also assessed expression of key proteins within the oxidative phosphorylation complexes and observed an increase in complex I (NDUFB8) and complex V (ATP5A) expression in the gastrocnemius muscle in response to SLU-PP-332 treatment (Figure 2C). Consistent with these observations, we also observed an increase in cytochrome c protein expression in response to SLU-PP-332 treatment in the gastrocnemius muscle (Figure 2D). Sections were also stained for laminin and consistent with an increased oxidative phenotype as the myofibers were smaller in diameter35 in SLU-PP-332-treated mice (Figure 2E). Electron micrographs of the quadriceps display an increase in mitochondria content in muscles from drug-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated (Figure 2F). Mitochondrial DNA concentrations in the skeletal muscle were also increased (relative to nuclear DNA) consistent with an increase in mitochondrial number (Figure 2G). We also noted that SLU-PP-332 treatment resulted in increased oxidative type IIa muscle fibers (Figure 2H,I) consistent with the increased expression of Myosin IIA protein by western blot (Figure 2J). This observation aligned with an increase in expression of Myh6, which encodes a myosin heavy chain subtype that is associated with type IIa muscle fibers36 (Figure 2K). These data indicate that pharmacological activation of ERRs leads to an increased oxidative capacity of skeletal muscle and an increase in type IIa muscle fibers and suggested that treatment of mice with SLU-PP-332 may lead to an increase in exercise endurance. To assess this, we treated sedentary mice with SLU-PP-332 or vehicle for 7 days (b.i.d., i.p. 50 mg/kg) and subjected them to exercise until exhaustion on a rodent treadmill. Plasma glucose levels were monitored following the exercise to confirm exhaustion (Figure S6B). As shown in Figure 2L, mice treated with the ERR agonist were able to run ∼70% longer and ∼45% further than vehicle-treated mice. In a separate study, where sedentary mice were treated in an identical manner except longer duration (2 weeks), we noted an increase in grip strength as well (Figure 2M).

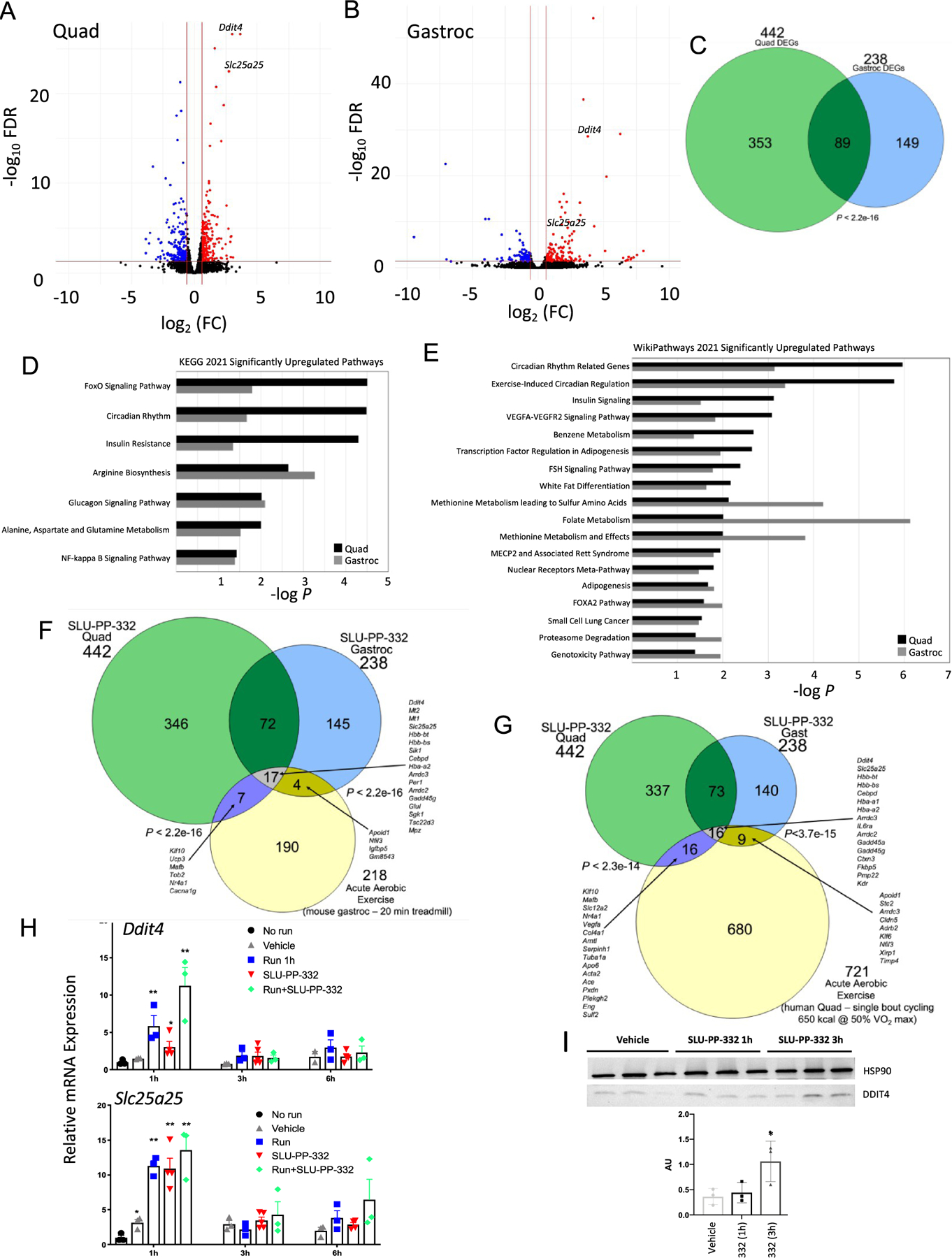

In order to assess alterations in gene expression due to drug treatment, we prepared RNA/cDNA from gastrocnemius and quadricep muscles from mice treated with SLU-PP-332 or vehicle (50 mg/kg, b.i.d., i.p., 10 days). Muscles were obtained 3 h post the final administration, and global changes in gene expression were assessed by RNA-Seq. We observed 442 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the quadricep muscle vs 238 DEGs in the gastrocnemius muscle (FDR < 0.05, |fold change (FC)| > 1.5) (Figure 3A,B and Supporting Information Part 2). There was a significant overlap between the quadricep and gastrocnemius muscle DEGs, as shown in Figure 3C (p < 2.2 × 10−16 by Fisher’s exact test). The top 10 pathways (KEGG and Wikipathway) upregulated and downregulated by SLU-PP-332 treatment in either muscle type are shown in Table S2. We observed substantial overlap in those pathways between muscle types that were significantly (p < 0.05) modulated. Pathways that were significantly SLU-PP-332 upregulated in both muscle types are shown in Figure 3D,E. Interestingly, these pathways are quite distinct from those identified as downregulated in the skeletal muscle ERRα/γ double KO mice, where oxidative phosphorylation, TCA cycle, and mitochondrial function genes were well represented.37 However, we previously showed that SLU-PP-332 induced a similar set of energetic genes/pathways in cardiomyocytes38 as were downregulated in the skeletal muscle double ERRα/γ KO consistent with SLU-PP-332 activation of ERRs. Thus, the pathways regulated by SLU-PP-332 may be distinct for the skeletal muscle. Importantly, SLU-PP-332 was very effective in improving heart function in a model of heart failure that was coupled to its ability to enhance fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial metabolism,38 validating its function as an ERR agonist. In the cardiomyocytes, the effect of SLU-PP-332 had effects on gene expression that was mediated by each of the ERRs (ERRα, β, and γ), whereas the effects that we observed on enhanced exercise capacity appeared to be mediated primarily through ERRα. It is unclear what drives the distinction in the array of genes that are induced by SLU-PP-332 in the cardiomyocytes vs the skeletal muscle, but recent studies with ERRs have described two distinct biochemical pathways ERRs utilize to induce transcription.39 One involves the well-described recruitment of PGC1α, while another involves a newly described direct recruitment of TFIIH.39 It is not currently clear if these distinct mechanisms by which ERRs induce gene expression may be promoter or cell-typespecific. It is also possible that agonists may preferentially induce a particular pathway that may be associated with unique patterns of target gene expression.

Figure 3.

SLU-PP-332 induces acute aerobic exercise genetic program in skeletal muscles. Results from RNA-seq studies from the gastrocnemius or quadricep muscles of mice treated with vehicle or SLU-PP-332. (A) Volcano plot illustrating differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (FDR > 0.05, | FC| > 1.5) from the quadriceps of SLU-PP-332-treated mice. Muscles were collected 3 h post final dose of a 10-day dosing regimen 50 mg/kg b.i.d. (B) Volcano plot illustrating differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (FDR > 0.05, |FC| > 1.5) from the gastrocnemius muscle of SLU-PP-332-treated mice. Muscles were collected 3 h post final dose of a 10-day dosing regimen 50 mg/kg b.i.d. (C) Venn diagram representing the overlap of DEGs from the two muscle types shown in panels (A) and (B). (D, E) Pathway analysis of DEGs in quadricep and gastrocnemius muscles after treatment with SLU-PP-332 in mice. The significantly (p < 0.05) regulated pathways shared in both muscle types are listed for KEGG pathways (D) and Wikipathways (E). (F) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of SLU-PP-332 DEGs and DEGs identified in the gastrocnemius muscle of mice subjected to acute aerobic exercise (see text for details). Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine significance. (G) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of SLU-PP-332 DEGs and DEGs identified in the quadricep muscle of lean humans subjected to acute aerobic exercise (see text for details). Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine significance. (H) Ddit4 (upper panel) and Slc25c25 expression (lower panel) from quadriceps from mice treated with vehicle (gray triangle), SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg, i.p., red triangle), SLU-PP-332 in combination of 45 min of running (green circle), or no treatment (black circle). Mice were euthanized as indicated 1, 3, or 6 h after treatment (n = 6 per group). (I) DDIT4 protein expression from quadriceps from mice treated with SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg, i.p.). Mice were euthanized as indicated 1 or 3 h after treatment (n = 3 per group). The bar graph represents the quantification of expression. p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

The exercise-induced circadian regulation pathway was affected in both muscles, with Per1 and Per2 both significantly upregulated (Supporting Information Part 2). The expression of Per1 and Per2 has been demonstrated to be induced by acute aerobic exercise previously, and most importantly, the induction of Per1 is completely dependent on DDIT4,40 which is the most upregulated “shared” gene between the quadricep and gastrocnemius muscles (see below). Although SLU-PP-332 treatment modulated Per1 expression in skeletal muscle, we observed no alterations in circadian locomotor activity with drug treatment (Figure S7). Foxo1 is also a well-characterized gene induced by acute endurance exercise in skeletal muscle41 and was also induced by SLU-PP-332 treatment (Supporting Information Part 2). δ-Aminolevulinate synthase 2 (Alas2) was also upregulated by SLU-PP-332 treatment (Supporting Information Part 2), and ALAS activity in skeletal muscle has been previously demonstrated to be enhanced by exercise.42 ALAS catalyzes the rate-limiting step in heme synthesis, and there are two forms of the enzyme encoded by the Alas1 and Alas2 genes. Alas1 is ubiquitously expressed, and its expression is enhanced in skeletal muscle following exercise.43 Alas2 expression is generally characterized as erythroid cell-specific. However, Alas2 has been demonstrated to be expressed in skeletal muscle, and its expression is modulated by macronutrients in the diet.44

Remarkably, a gene (Ddit4) that has been demonstrated to increase transiently following acute aerobic exercise45–47 and is responsible for directing an acute aerobic exercise-mediated gene expression signature48 was the most upregulated “shared” gene between the muscle types (Figure 3A,B and Supporting Information Part 2). DNA Damage Inducible Transcript 4/Regulated in development and DNA damage response-1 (DDIT4/REDD1) is critical for exercise adaptation and skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration as Ddit4−/− mice display reduced mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle and impaired exercise capacity49 as well as substantially impaired glucose tolerance.50 Expression of Ddit4 is also suppressed in the skeletal muscle of rhesus monkeys that are obese and exhibit symptoms of metabolic syndrome.44 We also noted an increase in the expression of a key gene induced as a component of the Ddit4-dependent acute aerobic exercise program, Slc25a2548 (Figure 3A,B). SLC25A25 is an ATP-Mg2+/Pi inner mitochondrial membrane solute transporter and plays a role in loading nascent mitochondria with nucleotides. Mice deficient in Slc25a25 expression display reduced metabolic efficiency and decreased exercise endurance.51 Reduced Slc25a25 expression leads to lower mitochondrial respiration,51 while enhanced Slc25a25 has been associated with increased mitochondrial respiration.52 Based on our observation that a key driver of an acute aerobic exercise gene program was highly upregulated by SLU-PP-332, we compared the DEGs of quadricep and gastrocnemius muscles for SLU-PP-332-treated mice with the DEGs identified by Sako et al.53 in mice subjected to acute aerobic exercise (20 min of treadmill running). As shown in Figure 3F, there was a significant overlap between both the SLU-PP-332 quadricep (p < 2.2 × 10−16) and gastrocnemius muscle DEGs (p < 2.2 × 10−16) and the DEGs from the gastrocnemius muscle of mice subjected to acute exercise (FDR < 0.05, |FC| > 1.5). Seventeen genes were shared among the three groups and include 4 of the top 10 upregulated genes identified by Gordon et al.48 in the DDIT4/REDD1 acute aerobic exercise pathway (Ddit4, Mt2, Slc25a25, and Sik1). We also compared the SLU-PP-332-induced DEGs from both muscle types to DEGs from the quadricep muscle identified in human acute aerobic exercise (single bout of cycling—650 kcal@50% VO2 max).54 As shown in Figure 3G, there was a significant overlap between both the SLU-PP-332 quadricep (p < 2.3 × 10−14) and gastrocnemius muscle DEGs (p < 3.7 × 10−15) and the DEGs from the quadriceps muscle of lean human patients subjected to acute exercise (FDR < 0.05, |FC| > 1.5). Sixteen genes were shared among the three groups and include both Ddit4 and Slc25a25 (Figure 3G). We also compared the intersecting genes from SLU-PP-332-treated mice to that of the acute exercise mouse and human genes and observed a significant overlap by comparing Figure 3F,G (p < 2.2 × 10−16; Fisher’s exact test). Eight genes were regulated among all of the groups and included Ddit4, Slc25a25, Hbb-bt, Hbb-bs, Cebpd, Hba-a2, Arrdc3, and Gadd45g.

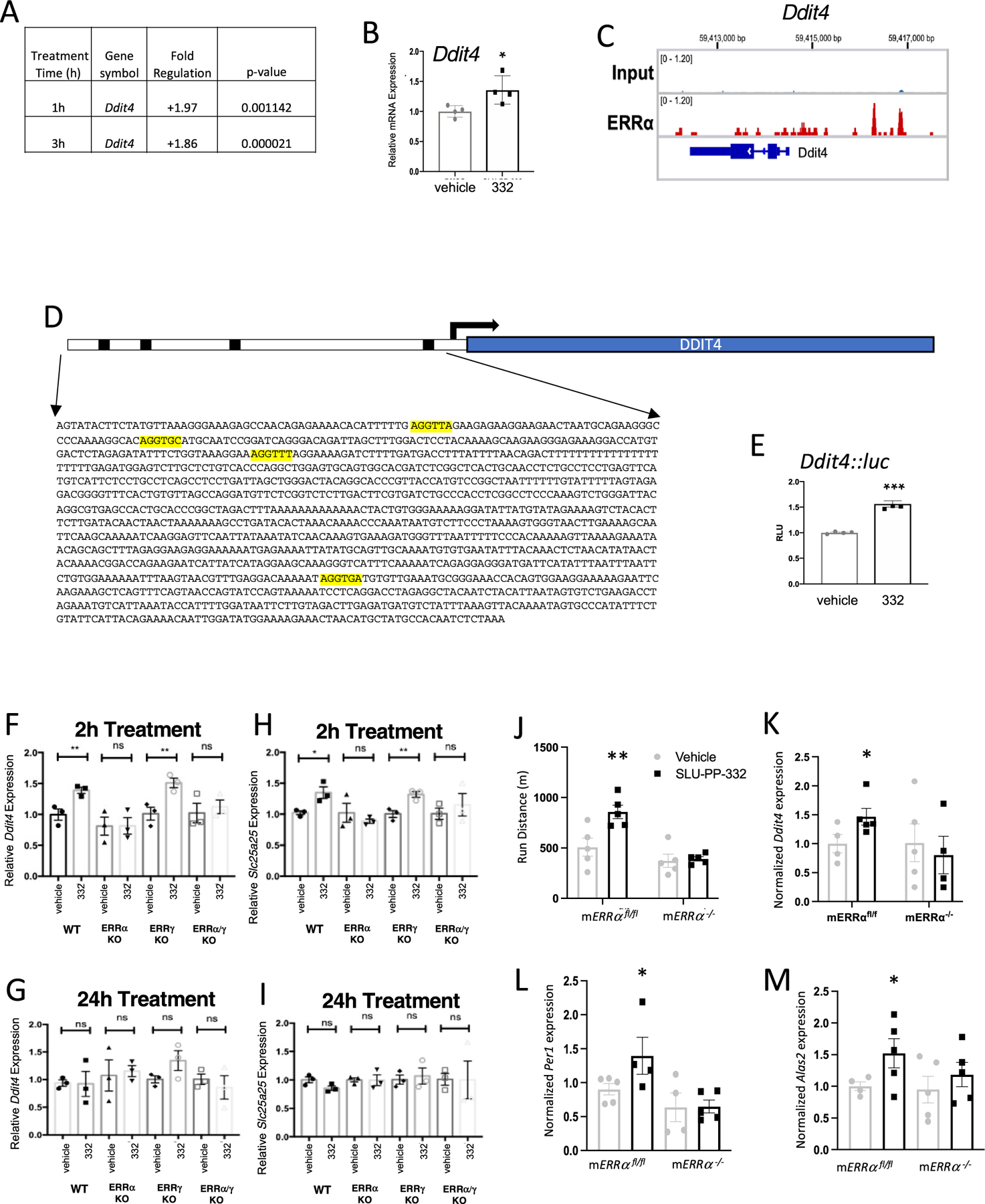

Using the significant gene sets from gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles from SLU-PP-332-treated mice (FDR < 0.05, |FC| > 1.5), we next analyzed the potential associated transcription factors in our treated samples using the EnrichR tool. Notably, we observed an ESRRA (ERRα)-associated gene set in the data analyzed from both gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles (Figure S8). This analysis suggests that SLU-PP-332 treatment is tightly associated with ERRα-dependent genes. Furthermore, we examined whether ERRα directly binds to the overlapped genes from gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscle samples by examining previously published ChIP-seq data that utilized C2C12 myocytes.55 We found ERRα is recruited near or within several genes that are included within the acute aerobic exercise genetic program, including Ddit4 (Figure 4C), Slc25a25, Mypn, Nr4a1, Hbb-bt, Hba-a1, Gadd45g, and Tsc22d3 (Figure S9).

Figure 4.

SLU-PP-332 induces Ddit4 expression and enhances exercise endurance in an ERRα-dependent manner. (A) Effects of SLU-PP-332 treatment (10 μM) for either 1 or 3 h on Ddit4 expression in C2C12 cells detected using the Qiagen RT2 PCR array. (B) Effects of SLU-PP-332 (10 μM) treatment of C2C12 for 3 h gene on Ddit4 expression (n = 3). (C) ERRα binding locations near and within the Ddit4 gene identified by ChIP-seq in C2C12 cells. (D) Schematic representation of luciferase reporter containing the putative ERRα binding site from Ddit4 identified in (C). (E) Cotransfection assay in HEK293T cells with full-length ERRα (including SLU-PP-332 (10 μM)). Ddit4 and Slc25a25 expression are transiently induced in primary myocytes by SLU-PP-332 in an ERRα-dependent manner. Ddit4 expression in primary ERR WT, ERRα KO, ERRγ KO, and ERRα/γ KO myoblasts treated with DMSO or SLU-PP-332 (1 μM) for 2 h (F) or 24 h (G). Slc25a25 expression in primary ERR WT, ERRα KO, ERRγ KO, and ERRα/γ KO myoblasts treated with DMSO or SLU-PP-332 (1 μM) for 2 h (H) or 24 h (I). (J) Running endurance of mERRαfl/fl vs mERRα−/− mice dosed with vehicle or SLU-PP-332. (K) Expression of Ddit4 mRNA (quadricep) mice shown in panel (J) measured by QPCR (L) Expression of Per1 mRNA (quadricep) mice shown in panel (J) measured by QPCR (M) Expression of Alas2 mRNA (quadricep) mice shown in panel (J) measured by QPCR. p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

With this data in hand indicating that SLU-PP-332 treatment enhanced exercise endurance and induced a gene program similar to acute aerobic exercise in skeletal muscle, we sought to compare the effects of acute SLU-PP-332 treatment to acute aerobic exercise in terms of induction of Ddit4 and Slc25a25. Three-month-old C57BL/6J male mice were administered a single dose of SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg; i.p.) or vehicle and compared to mice that were sedentary or subject to acute aerobic exercise (run for 40 min on a rodent treadmill). Ddit4 and Slc25a25 gene expression from the gastrocnemius muscle was assessed at 1, 3, and 6 h post initiation of the run or drug administration (from distinct groups of mice). At 1 h post run or treatment initiation, Ddit4 expression was ∼6-fold higher in the exercised group, and, most importantly, we noted that SLU-PP-332 treatment of sedentary mice induced an ∼3-fold increase in this gene (Figure 3H, top). Mice that received both the drug and were exercised displayed an additive effect on Ddit4 expression (∼11-fold increase; Figure 3H, top). All of these effects were transient, and the effects were not observed in the later time points (Figure 3H, top). Acute aerobic exercise and SLU-PP-332 treatment led to equivalent 11-fold increases in Slc25a25 expression after 1 h and like Ddit4, the effect was lost after 3 h (Figure 3H, bottom). Thus, induction of these two acute aerobic exercise program genes by either SLU-PP-332 or exercise was similar in terms of magnitude and duration. We also examined DDIT4 protein expression from the quadricep muscle 1 and 3 h post SLU-PP-332 treatment and noted a time-dependent increase in expression, reaching a level 3.5× higher after 3 h (Figure 3I). We also examined ERRα expression at 1 and 3 h post administration of the drug and observed no change in expression, indicating that the kinetics of the response was not due to changes in ERRα expression (Figure S10A).

Ddit4, a Regulator of an Acute Aerobic Exercise Genetic Program, Is an ERRα-Specific Target Gene.

We next sought to characterize ERR regulation of Ddit4 in greater detail using the C2C12 myoblast cell line. Using both a QPCR array (Figure 4A) and direct QPCR (Figure 4B), we found that Ddit4 gene expression was induced in the C2C12 myoblast cell line by SLU-PP-332 treatment, and the induction was detected in as little as 1 h (Figure 4A). The magnitude of induction of Ddit4 was lower than what was observed in vivo, and it was unclear whether this difference was due to the C2C12 cells or in vitro vs in vivo assessment at this point. As described above, ERRα occupancy was observed in the 5′ region and intragenic regions of the Ddit4 gene (Figure 4C) as well as within many other of the other genes regulated by SLU-PP-332, including Slc25a25, Mypn, Nr4a1, Hbb-bt, Hba-a1, Gadd45g, and Tsc22d3 (Figure S9). Multiple putative ERREs were identified in the promoter and intragenic regions of Ddit4 (Figure 4D). Given the importance of Ddit4 directing an acute aerobic exercise genetic response, as we discussed above, we focused more closely on the regulation of Ddit4 by ERRs. We assessed the promoter region bound by ERRα identified in the ChIP-seq data containing a putative ERRE that conferred SLU-PP-332 responsiveness to a luciferase reporter gene when cotransfected into HEK293 cells along with ERRα, consistent with Ddit4 functioning as a direct ERRα target gene (Figure 4E). At this point, it was unclear what the relative contribution of each of the ERRs to Ddit4 regulation was; thus, we performed an assessment of Ddit4 regulation in response to SLU-PP-332 in primary myocytes derived from skeletal muscle-specific ERRα and ERRα/γ KO mice. ERRβ is not expressed in these cells (Figure S10C). We observed that Ddit4 expression was induced in primary mouse myocytes (derived from quadriceps) by acute SLU-PP-332 treatment (2 h) (Figure 4F). However, this effect was not observed after 24 h of treatment (Figure 4G), reminiscent of the transitory effect that we observed in vivo. This is consistent with the transient induction of genes in the acute aerobic exercise genetic program. We also observed that the level of induction of Ddit4 was similar to that in the C2C12 cells, suggesting that the lower level of induction relative to the in vivo studies was due to the in vitro nature of the experiment and not the C2C12 cells. The effect of SLU-PP-332 on Ddit4 expression was dependent on ERRα since the effect was lost in myocytes derived from ERRα or ERRα/γ null mice but was retained in ERRγ null myocytes (Figure 4F). SLU-PP-332 induced expression of Slc25a25 in a pattern identical to Ddit4 (Figure 4H). Slc25a25 responsiveness was completely ERRα-dependent and was transient, with an effect noted at 2 h but not at 24 h post treatment (Figure 4I). These results in the primary myocytes suggest that the effects of SLU-PP-332 on induction of the acute aerobic exercise genes such as Ddit4 are mediated via ERRα and not ERRβ or ERRγ. However, it is important to reinforce that other genes that are regulated by SLU-PP-332 treatment may be mediated by the other ERR paralogs, given this drug is not selective enough to provide absolute specificity.

In order to investigate this in the context of the whole animal, we treated mice with a muscle-specific KO of ERRα with SLU-PP-332. mERRαfl/fl or mERRα−/− 15 were treated for 14 days with SLU-PP-332 (b.i.d., i.p, 50 mg/kg) and then subjected to exercise until exhaustion. mERRαfl/fl treated with SLU-PP-332 exhibited significantly enhanced exercise endurance, while the mERRα−/− treated with SLU-PP-332 displayed exercise endurance equivalent to vehicle-treated mERRα−/− mice (Figure 4J). Moreover, upregulation of Ddit4 in quadriceps was observed only in mERRαfl/fl treated with SLU-PP-332 but not in the mERRα−/− treated group (Figure 4K). The magnitude of induction by SLU-PP-332 treatment was lower than we had previously observed, but collection of the muscle was delayed in this experiment relative to that described for Figure 3H, and given the rapid decline in Ddit4 induction in vivo, this is likely the reason for the distinction. Two other genes that we identified as upregulated in response to SLU-PP-332 treatment in skeletal muscle, Per1 and Alas2 (Figure 3F), were also significantly induced in the mERRαfl/fl mice by SLU-PP-332 treatment but not in the mERRα−/− mice (Figure 4L,M). These data illustrating the ability of administration of SLU-PP-332, a compound that induces an acute exercise genetic program via activation of ERRα, to increase exercise endurance, are consistent with studies demonstrating that both Ddit4 and Slc25a25 are key regulators of mitochondrial function, and mice with null mutations in either of these genes exhibit substantially reduced exercise endurance.49,51,52

CONCLUSIONS

The ERRs play important roles in the regulation of energy metabolism and fuel selection. Loss of ERRα or ERRγ function leads to reduced muscle oxidative function and reduced functional endurance;16,37,56 thus, pharmacological activation of these receptors may lead to beneficial metabolic effects associated with increased skeletal muscle activity for the treatment of metabolic diseases. In this study, we characterize the ability of a pan ERRα/β/γ synthetic agonist with ∼4-fold ERRα selectivity over ERRγ (SLU-PP-332) to function as an exercise mimetic and improve muscle and metabolic function both in vitro and in vivo. The key novelty of this compound is the ability to activate ERRα as well as the pharmacokinetic properties sufficient for in vivo studies. However, it is important to note that our studies with this compound were performed under conditions where all three ERRs would be activated, and this compound does not have sufficient specificity to probe the individual functions of ERR paralogs. Given the unique pharmacological activity of this compound to target activation of ERRα, we employed a genetic model combined with SLUPP-332 to identify an ERRα-dependent pathway that is linked to a previously identified acute aerobic exercise genetic response.

We found that SLU-PP-332 treatment induces the expression of DDIT4 via specific activation of ERRα. DDIT4 is a key protein that is induced after short bouts of aerobic exercise that is responsible for inducing an acute aerobic exercise genetic program that leads to a range of physiological adaptations to exercise.48 We found that Ddit4 is a direct ERRα target gene, and previous data indicating that Ddit4 null mice display reduced exercise endurance49 is consistent with our results, indicating that SLU-PP-332 treatment, which induces Ddit4 expression, enhances exercise endurance. The array of genes that are induced by both SLU-PP-332 and acute aerobic exercise have been linked mechanistically to improved exercise endurance, increased fatty acid oxidation, and/or improved metabolic efficiency, which are all physiological components of the adaptive response to exercise. Of course, the key gene we examined, Ddit4, is associated with mitochondrial function and improved exercise endurance,49 and another gene within this program we examined, Slc25a25, is also similarly associated with these endpoints.51 Most importantly, the effects of SLU-PP-332 on exercise endurance are dependent on ERRα as mice with muscle-specific deletion of this receptor are refractory to improved performance. It must be reinforced that the pharmacodynamic properties of SLU-PP-332 are such that at the dose we used to assess ERR activation of all three ERR paralogs would be targeted.

Previously, it had been reported that skeletal muscle overexpression of ERRγ in mice led to improved endurance;17 however, we noted substantial differences in the array of genes regulated by overexpression of ERRs compared to pharmacological activation of ERRs. The acute aerobic exercise gene program was not identified when either ERRα or ERRγ was overexpressed or knocked out.9,12 We believe that transient activation of ERRs may be quite distinct than either chronic overexpression or complete loss of the receptor. Furthermore, overexpression of ERR(s) likely provides for an unremitting level of elevated transcriptional activity that cannot be mimicked by pharmacological activation of this receptor class that already displays strong constitutive transactivation activity. Multiple bouts of aerobic exercise (2 h/day for 8 days on a rodent treadmill) have been shown to induce ERRα (∼1.5-fold) and ERRγ (∼2.1-fold) expression within the gastrocnemius muscle in mice.18 Short-term aerobic exercise (cycling) in humans has been shown to induce ERRα (mRNA and protein expression) in skeletal muscle (m. vastus lateralis) to a similar extent (1.5–2-fold).6 These data suggest that the ∼2-fold increase in the ERR transcriptional activity that we observe with SLU-PP-332 treatment is likely more similar to physiological changes in ERR activity induced by exercise than experimental models of skeletal muscle overexpression of ERR(s) or VP-16 ERR fusion proteins. Thus, pharmacological activation of ERR may be more closely aligned with driving physiological changes that are similar to normal exercise adaptation such as induction of the acute aerobic exercise response rather than chronic overexpression of ERR or similar key regulator proteins.

In summary, activation of ERRα by SLU-PP-332 as an exercise mimetic induces an acute aerobic exercise program that leads to an array of physiological adaptations that are associated with exercise, including increased oxidative fibers in a muscle, increased fatty acid oxidation, and enhanced exercise endurance. Several nuclear receptors, such as LXR, FXR, PPARα, PPARδ, PPARγ, and REV-ERB, among others, have been evaluated or utilized as targets for compounds for the treatment of metabolic disease. However, only pharmacological activation of REV-ERB and PPARδ has been reported to have exercise-mimetic activity.57,58 Interestingly, activation of the acute aerobic exercise program appears to be unique for ERR agonists as this was not reported for PPARδ or REV-ERB. ERRα-targeted compounds that increase the metabolic performance of skeletal muscle may hold utility in the treatment of metabolic diseases and diseases of muscle atrophy and dysfunction, including muscular dystrophy and sarcopenia.

METHODS

Molecular Modeling.

All four models of ERRγ and ERRα bound with GSK4716 or SLU-PP-332 were built from the X-ray crystal structure of ERRγ-GSK4716 (PDB: 2GPP).23 SLU-PP-332 was modeled by modifying the isopropyl group into a naphthalene group using Maestro (Schrodinger Release 2019–1: Maestro, Schrodinger, LLC. New York, NY). The initial X-ray structure has two water molecules bridging the ligand and the protein residues, and they were kept in the ligand binding pocket in each model. Each system was first energy-minimized using the steepest descent and conjugate gradient methods with keeping the ligand and the bridged water molecules constrained. The constraints were removed, and then each system was energy-minimized entirely in Amber.59 Tleap module was used to neutralize and solvate the complexes using an octahedral water box of TIP3P water molecules. The FF14SB force field parameters were used for all receptor residues, and the general Amber force field was applied to ligand residues.60,61 Nonbonded interactions were cut off at 10.0 Å, and long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle mesh Ewald (PME). Ligands were modeled using Maestro, and pictures were generated using UCSF Chimera and Maestro.62 After energy minimization, the water molecules left the pocket, and the acyl hydrazine made alternative hydrogen-bonding interaction with the protein backbone residues. The phenolic hydroxyl in the ERRγ-GSK4716 model maintained similar hydrogen-bonding interaction with Asp328 as the starting X-ray structure. Energy minimization using MacroModel and the OPLS3 force field yielded similar results (Schrodinger Release 2019–3: MacroModel, Schrodinger, LLC. New York, NY).63 Although the phenolic hydroxyl group in the other three models made hydrogen-bonding interactions with different protein residues, it remained in a similar position as in the ERRγ-GSK4716 X-ray structure near the solvent-exposed surface of the protein (Figure 1). We used the MM/GBSA64 method to estimate the binding free energies of GSK4716 and SLU-PP-332 to both receptors (Table S3). MM/GBSA, an end point energy calculation method used for estimating relative binding free energies, is particularly useful for ligand ranking and optimization in the process of drug discovery.65,66 The binding of GSK4716 and SLU-PP-332 to ERRα and ERRγ is enthalpy-driven with a negative total binding free energy, indicating favorable binding (Table S3). ΔH corresponds to the favorable affinity contribution, while ΔS is the entropy and reflects the decrease in conformational freedom in the protein–ligand complex. In the case of ERRγ, the enthalpy contribution of GSK4716 to the total binding free energy is more favorable than SLU-PP-332; however, the entropy penalty is greater in the case of GSK4716 over SLU-PP-332, resulting in similar total binding free energies with a difference of 1.5 kcal/mol in favor of SLU-PP-332 (Table S3). However, in the case of ERRα, the enthalpy contribution of SLU-PP-332 is more favorable, and the entropy penalty is less, resulting in a more favorable total binding free energy (6.6 kcal/mol difference between SLU-PP-332 and GSK4716) (Table S3). Based on these calculations, SLU-PP-332 was predicted to have a higher affinity for both receptors and particularly toward ERRα, with the reduction of the unfavorable entropic contribution associated with ligand binding as the main contributor toward the improved affinity. Additionally, several analogues of GSK4716 where the isopropyl phenyl group was replaced were tested, and the naphthalene substituent (SLU-PP-332) was considerably more potent than any others (Table S4).

Synthesis and Preparation of SLU-PP-332.

(E)-4-Hydroxy-N′-(naphthalen-2-ylmethylene)benzohydrazide. To a solution of 2-naphthaldehyde (1.0 g, 6.6 mmol) in toluene (100 mL) was added 4-hydroxybenzohydrazide (1.1 g, 6.6 mmol) portion wise. The mixture was allowed to stir for 18 h at reflux. A solid precipitated, which was recrystallized from a 1:9 mixture of methanol and ether to obtain the title compound as a white solid (1.3 g, 68%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.81 (s, 1H), 10.18 (s, 1H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 8.06–7.84 (m, 6H), 7.54 (dp, J = 6.5, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 6.93 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.3Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.96, 160.81, 146.88, 133.68, 132.93, 132.33, 129.81, 128.49, 128.30, 127.79, 127.03, 126.73, 123.95, 122.74, 115.11. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) calculated for C18H15N2O2 (M + H)+: 291.11280, found: 291.11284.

Cell Culture.

C2C12 cells (ATCC CRL-1772), mouse myoblast cell line, were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% L-glutamine. Primary myoblasts were maintained in DMEM/F12 (1:1) media supplemented with 40% heat-inactivated FBS and 10% AmnioMAX (Lifetech). Cells were treated with SLU-PP-332 or DMSO (10 μM). After 24 h of treatment, RNA was extracted by Invitrogen Purelink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). All groups were tested in triplicate.

Cotransfection Assays.

As previously described,67–69 HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours prior to transfection, HEK293 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well. GAL4-NR-LBD or FLAG-ERR-FL plasmids were used in the luciferase assay.

Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR).

The RNA samples were reverse-transcribed using the qScript cDNA kit (Quanta). All samples were run in duplicate, and the analysis was completed by determining ΔΔCt values. The reference gene used was 36B4, a ribosomal protein gene. Primers sequences are listed in the Supporting Information.

Bioenergetic Profile of C2C12 Cells.

Bioenergetics profile tests in C2C12 myoblasts were conducted, as described by Nicholls et al.70 The day before (24 h) the assay, C2C12 cells were seeded (10,000/well) in growth media on the 96-well XF Flux Analyzer (Seahorse) cell plate.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry.

ERRγ protein was diluted in a buffer containing 25 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM EDTA at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL and mixed with SYPRO-Orange dye (Life Technologies S6650). Four different concentrations of ligands (20, 10, 5, and 2.5 μM) were used. Six replicate reactions were set up and run in Applied Biosystems Quantstudio 7 Real-Time PCR system. Data were collected at a ramp rate of 0.05 °C/s from 24 to 95 °C and analyzed using Protein Thermal Shift Software 1.3.

Fiber Type, SDH, and Laminin Staining.

Fresh cryo-sections (10 μm) were incubated for 1 h with Mouse on Mouse (M.O.M, Vector Lab) incubation media and then incubated with BA–D5, SC71, or BF-F3 antibodies (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) for 45 min at 37 °C, in PBS–1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in PBS–1% BSA for 30 min at 37 °C. Sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBS and mounted using ProLong Gold mounting media (Thermo Fisher) under glass coverslips.

Fresh cryo-sections (10 μm) were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in incubation medium (50 mM phosphate buffer, sodium succinate 13.5 mg/mL, NBT 10 mg/mL in water) placed in a Coplin Jar, and then the section was rinsed in PBS. After staining sections were fixed in 10% formalin–PBS solution for 5 min at room temperature (RT) and then rinsed in 15% alcohol for 5 min. Slides were mounted with an aqueous medium and sealed. Cryostat sections (10 μm) were fixed for 20 min in 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Sections were blocked with 8% BSA in PBS-1 h at RT and then incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibody for laminin at a 1:200 dilution. Sections were then washed and incubated with anti-rabbit-FITC (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were mounted with fluorescent mounting medium containing Dapi (Vector lab) under glass coverslips. All quantifications were performed using ImageJ software.

Mice.

Male C57BL6/J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Studies performed with C57BL6/J mice were approved and conducted in accordance with the Saint Louis University and Washington University Animal Care Use Committees. The conditional ERRα knockout mice used in exercise performance trials have been described.15 All procedures using the skeletal muscle-specific ERRαfl/fl and ERRα−/− mice were performed in accordance with the City of Hope Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

General Mouse Studies.

For all experiments, 8–10 male C57BL6/J mice per group (12 weeks of age for chow) were administered a dose of SLU-PP-332 50 mg/kg (i.p., b.i.d.) or vehicle for 28 or 12 days. At termination of the experiment, tissues were collected for gene expression analysis by real-time qPCR using methods previously described. Food intake and body weight were monitored daily in these experiments, and body composition was measured prior to initiation and termination of the experiments by NMR (Bruker BioSpin LF50). Plasma was collected for triglyceride and cholesterol measurements. All b.i.d. dosing was performed, with dosing occurring at CT0 and CT12.

Exercise Endurance in WT Mice.

Six male mice (C57BL6/J, 12 weeks old) were either treated with vehicle control (10% Tween, 10% DMSO, 80% PBS) or SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg, i.p.), run on Exer 3-/6 treadmill (Columbus Instruments) for 45 min at 12 m/min or left untreated. Animals were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation 1, 3, or 6 h after intervention. For exhaustion protocol, six male C57BL6/J, 12 weeks old, were with vehicle control (10% Tween, 10% DMSO, 80% PBS) or SLU-PP-332 (50 mg/kg, i.p.) for 6 days before testing. Mice were allowed to acclimate to the treadmill for 10 min/day, every day at 2 m/min. On the day of the test, mice were run 1 h after the last dose of vehicle or drug. Mice were running for 2 min at 10 m/min, then 6 min at 12 m/min, and then ran until exhaustion by increasing the speed of the belt for 2 m/min every 2 min.71 Exhaustion was assessed by mice allowing 10 consecutive 3 ms electrical shocks without moving. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation just after exhaustion, and exhaustion was confirmed by measuring blood glucose.

Exercise Endurance in Muscle-Specific ERRα KO Mice.

Skeletal muscle-specific KO mice, ERRαfl/fl and ERRα−/− mice (20–24 week old, 30.7 + 0.26 g b.w.) were segregated into vehicle-treated or SLU-PP-332-treated groups (n = 5/group). Mice were administered (i.p.) vehicle (10% DMSO, 15% Kolliphor EL in sterile saline) or 25 mg/kg SLU-PP-332 for 15 days. Prior to run performance, trial mice were acclimated to the treadmill (Columbus Instruments Exer 3/6 motorized treadmill) for 3 days (10 min at 10 m/min, then 2 min at 15 m/min). To assess aerobic run performance, mice were run at 10, 12.5, and 15 m/min for 3 min at each speed, after which the speed was increased by 1 m/min every 2 min (max speed 28 m/min) until exhaustion. Basal and post-run blood lactate readings were read to confirm exhaustion. Mice were sacrificed, and hindlimb muscles were collected 24 h after the run performance test.

Glucose Measurement.

Blood was collected by tail snip, and glucose was measured when mice reached exhaustion using OneTouch Ultra 2 glucometer.

Pharmacokinetic Studies.

Pharmacokinetic studies of SLU-PP-332 in mice were performed, as previously described.72 Three-month-old C57Bl6/J male mice (n = 3) were injected (i.p.) at ZT 1 with 30 mg/kg of SLU-PP-332 (5% Tween–5% DMSO–90% PBS). The animals were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation, and tissues were collected at 1, 2, or 4 h after administration of the compound (n = 4 per time point). Plasma and tissues (liver, quadriceps, and brain) were collected, flash-frozen, and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Tissue samples were weighed and placed into Eppendorf tubes. NaÏve tissue was used to prepare standard curves in the muscle tissue matrix. To each sample or standard tube were added three to five stainless steel beads (2–3 mm) and the appropriate volume of cold 3:1 acetonitrile/water (containing 100 ng/mL extraction internal standard SR8278)73 to achieve a tissue concentration of 200 mg/mL. Tubes were placed in a bead beater for 2–3 min. Samples and standards (100 μL) were plated in a 96-well plate, 150 μL of acetonitrile was added to each well and then centrifuged at 3200 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (100 μL) was transferred to a 96-well plate, evaporated to dryness under nitrogen, reconstituted with 100 μL of 0.1% v/v formic acid in 9:1 water/acetonitrile, and vortexed for 5 min. Plasma samples or standards prepared in a plasma matrix (100 μL) were added to a 96-well plate. To each well, 400 μL of cold acetonitrile containing 100 ng/mL extraction internal standard SR8278 was added. The plate was vortexed for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (300 μL) was transferred to a second 96-well plate, evaporated to dryness under nitrogen, reconstituted with 100 μL of 0.1% v/v formic acid in 9:1 water/acetonitrile, and vortexed for 5 min. Finally, to each reconstituted tissue or plasma sample, 10 μL of 1000 ng/mL enalapril in acetonitrile was added as an injection internal standard, and the 96-well plate was vortexed, briefly centrifuged, and submitted for LC/MS analysis. SLU-PP-332 concentrations were determined on a Sciex API-4000 LC/MS system in positive electrospray mode. Analytes were eluted from an Amour C18 reverse phase column (2.1 × 30 mm2, 5 μm) using a 0.1% formic acid (aqueous) to 100% acetonitrile gradient mobile phase system at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min. Peak areas for the mass transition of m/z 291 > 121 for SLU-PP-332, m/z 394 > 189 for the extraction internal standard SR8278, and m/z 376 > 91 for the injection internal standard enalapril were integrated using Analyst 1.5.1 software. Peak area ratios of SLU-PP-332 area/SR8277 area were plotted against concentration with a 1/x-weighted linear regression. Enalapril was used to monitor proper injection signals throughout the course of LC/MS analysis.

Lipid Assays.

Plasma triglycerides, total cholesterol, and liver enzymes were assessed using an Analox (GM7 MicroStat) instrument and kits provided by the same manufacturer, following their protocols.

Limited Proteolysis Digestion.

In vitro translated ERRα full-length (TNT kit; Promega) was used. Briefly, after incubating at room temperature for 15 min with ligands (1–5–10 μM), receptor proteins were digested at room temperature for 10 min with 10 μg/mL trypsin. The proteolytic fragments were separated on a 4–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad) and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

Assessment of Locomotor Activity.

Locomotor activity was assessed using mice housed in cages with free access to running wheels. Briefly, after a 2-day acclimation period to wheel-equipped cages in a 12:12 light–dark (LD), locomotor activity was recorded over a 48 h period. Wheel running data were analyzed using Clocklab software (Actimetrics, Evanston, IL).

Mitochondrial DNA Quantification.

Mitochondrial DNA was extracted using QiAamp DNA mini kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). DNA was quantified using Sybr Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). All samples were run in duplicate, and the analysis was completed by determining ΔΔCt values. The reference gene used was NRDUV1, a genomic DNA marker.

Statistical Analysis.

The numerical values for potency (EC50 for stimulation or IC50 for inhibition) are indicated in the figures and are derived from GraphPad Prism analysis of the 11-point (full-length ERR assays) or 5-point (Gal4-LBD ERR assays) concentration–response curves. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Student’s test, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or Fisher’s exact test were used to calculate statistical significance. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

OXPHOS Western Panel.

OXPHOS protein expression was assessed using the Thermo Fisher OxPhos Rodent WB Antibody Cocktail (#45–8099). In order to normalize for protein loading, we used the Stain-Free Western Workflow suite from Bio-Rad (https://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/Bulletin_RP0051.pdf). Image Lab 4.0 software, a component of ChemiDoc MP (Bio-rad), was employed, and the relative amount of total protein in each lane on the blot was calculated and used for quantitation normalization. We then identified a band for each OXPHOS complex and then normalized their intensity level to the total protein intensity for each lane. Then, the average and standard deviation were calculated for each group (vehicle and SLU-332).

RNA-Seq and RNA-Seq Analysis.

RNA-seq and analysis were performed as previously described.74 Volcano plots plotting log2(Fold Change) vs log10FDR using R(v4.2.0) for genes in SLU-PP-332 RNA-seq data set. R was employed to compare DEGs of SLU-PP-332-treated mice, and mouse/human acute exercise data sets and the Fisher Exact test was used to assess for a significant overlap. The EnrichR tool was utilized for pathway analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank G. Kolar and B. Nagel (Saint Louis University) for their help in processing samples for electron microscopy. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AR069280, MH092769, AG060769, MH093429, AG077160; TPB and DK057978, HL105278, HL088093, and ES010337; R.M.E.), and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust (2017PG-MED001; R.M.E.). R.W. is supported under a T32DK training program, and R.M.E. and M.D. are supported, in part, by a Stand Up to Cancer Dream Team Translational Cancer Research grant and a Program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation (SU2C-AACR-DT-20-16). R.M.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and March of Dimes Chair in Molecular and Developmental Biology at the Salk Institute. J.M.H. is supported by the American Diabetes Association Innovative Basic Science Award (1–18-IBS-103) and support from the Lion’s Club Diabetes Innovation Fund.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschembio.2c00720.

Upregulated and downregulated genes in quadricep muscles in response to SLU-PP-332 (XLSX)

Upregulated and downregulated genes in gastrocnemius muscles in response to SLU-PP-332 (XLSX)

Physical and pharmacological characterization of SLU-PP-332, effects of SLU-PP-332 on mitochondrial respiration, plasma creatine kinase levels, clinical chemistry parameters, muscle morphology, and gene expression (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acschembio.2c00720

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): T.P.B., B.E., and J.K.W. are stockholders in Myonid Therapeutics, Inc., which focuses on ERR based therapeutics.

Contributor Information

Cyrielle Billon, Center for Clinical Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis College of Pharmacy, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, United States.

Sadichha Sitaula, Center for Clinical Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis College of Pharmacy, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, United States.

Subhashis Banerjee, Department of Pharmacology & Physiology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri 63104, United States.

Ryan Welch, Gene Expression Laboratory Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Bahaa Elgendy, Center for Clinical Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis College of Pharmacy, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, United States.

Lamees Hegazy, Center for Clinical Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis College of Pharmacy, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, United States.

Tae Gyu Oh, Gene Expression Laboratory Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Melissa Kazantzis, The Scripps Research Institute Jupiter, Jupiter, Florida 33458, United States.

Arindam Chatterjee, Department of Pharmacology & Physiology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri 63104, United States.

John Chrivia, Department of Pharmacology & Physiology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri 63104, United States.

Matthew E. Hayes, University of Florida Genetics Institute, Gainesville, Florida 32610, United States

Weiyi Xu, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, United States.

Angelica Hamilton, Department of Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology, City of Hope, Duarte, California 91010, United States.

Janice M. Huss, Department of Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology, City of Hope, Duarte, California 91010, United States

Lilei Zhang, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, United States.

John K. Walker, Department of Pharmacology & Physiology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri 63104, United States; Department of Chemistry, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri 63103, United States

Michael Downes, Gene Expression Laboratory Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Ronald M. Evans, Gene Expression Laboratory Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California 92037, United States; Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California 92037, United States

Thomas P. Burris, Center for Clinical Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis College of Pharmacy, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, United States; University of Florida Genetics Institute, Gainesville, Florida 32610, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Booth FW; Roberts CK; Laye MJ Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr. Physiol 2011, 2, 1143–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).O’Gorman DJ; Karlsson HK; McQuaid S; Yousif O; Rahman Y; Gasparro D; Glund S; Chibalin AV; Zierath JR; Nolan JJ Exercise training increases insulin-stimulated glucose disposal and GLUT4 (SLC2A4) protein content in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2983–2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med 2002, 346, 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Koopman R; Manders RJ; Zorenc AH; Hul GB; Kuipers H; Keizer HA; van Loon LJ A single session of resistance exercise enhances insulin sensitivity for at least 24 h in healthy men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol 2005, 94, 180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Borsheim E; Bahr R Effect of exercise intensity, duration and mode on post-exercise oxygen consumption. Sports Med 2003, 33, 1037–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Egan B; Zierath JR Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab 2013, 17, 162–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Meex RC; Schrauwen-Hinderling VB; Moonen-Kornips E; Schaart G; Mensink M; Phielix E; van de Weijer T; Sels JP; Schrauwen P; Hesselink MK Restoration of muscle mitochondrial function and metabolic flexibility in type 2 diabetes by exercise training is paralleled by increased myocellular fat storage and improved insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 2010, 59, 572–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Giguère V; Yang N; Segui P; Evans RM Identification of a new class of steroid hormone receptors. Nature 1988, 331, 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Giguere V Transcriptional control of energy homeostasis by the estrogen-related receptors. Endocr. Rev 2008, 29, 677–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chen F; Zhang Q; McDonald T; Davidoff MJ; Bailey W; Bai C; Liu Q; Caskey CT Identification of two hERR2-related novel nuclear receptors utilizing bioinformatics and inverse PCR. Gene 1999, 228, 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Sladek R; Bader JA; Giguere V The orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor alpha is a transcriptional regulator of the human medium-chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase gene. Mol. Cell. Biol 1997, 17, 5400–5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fan W; Evans R PPARs and ERRs: molecular mediators of mitochondrial metabolism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 2015, 33, 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Audet-Walsh E; Giguere V The multiple universes of estrogen-related receptor alpha and gamma in metabolic control and related diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 2015, 36, 51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Huss JM; Imahashi K; Dufour CR; Weinheimer CJ; Courtois M; Kovacs A; Giguere V; Murphy E; Kelly DP The nuclear receptor ERRalpha is required for the bioenergetic and functional adaptation to cardiac pressure overload. Cell Metab 2007, 6, 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).LaBarge S; McDonald M; Smith-Powell L; Auwerx J; Huss JM Estrogen-related receptor-alpha (ERRalpha) deficiency in skeletal muscle impairs regeneration in response to injury. FASEB J 2014, 28, 1082–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Perry MC; Dufour CR; Tam IS; B’Chir W; Giguere V Estrogen-related receptor-alpha coordinates transcriptional programs essential for exercise tolerance and muscle fitness. Mol. Endocrinol 2014, 28, 2060–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Narkar VA; Fan W; Downes M; Yu RT; Jonker JW; Alaynick WA; Banayo E; Karunasiri MS; Lorca S; Evans RM Exercise and PGC-1alpha-independent synchronization of type I muscle metabolism and vasculature by ERRgamma. Cell Metab 2011, 13, 283–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Rangwala SM; Wang X; Calvo JA; Lindsley L; Zhang Y; Deyneko G; Beaulieu V; Gao J; Turner G; Markovits J Estrogenrelated receptor gamma is a key regulator of muscle mitochondrial activity and oxidative capacity. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 22619–22629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fan W; Atkins AR; Yu RT; Downes M; Evans RM Road to exercise mimetics: targeting nuclear receptors in skeletal muscle. J. Mol. Endocrinol 2013, 51, T87–T100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hyatt SM; Lockamy EL; Stein RA; McDonnell DP; Miller AB; Orband-Miller LA; Willson TM; Zuercher WJ On the intractability of estrogen-related receptor alpha as a target for activation by small molecules. J. Med. Chem 2007, 50, 6722–6724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Patch RJ; Searle LL; Kim AJ; De D; Zhu X; Askari HB; O’Neill JC; Abad MC; Rentzeperis D; Liu J; et al. Identification of diaryl ether-based ligands for estrogen-related receptor alpha as potential antidiabetic agents. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 788–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Patch RJ; Huang H; Patel S; Cheung W; Xu G; Zhao BP; Beauchamp DA; Rentzeperis D; Geisler JG; Askari HB; et al. Indazole-based ligands for estrogen-related receptor alpha as potential anti-diabetic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2017, 138, 830–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang L; Zuercher WJ; Consler TG; Lambert MH; Miller AB; Orband-Miller LA; McKee DD; Willson TM; Nolte RT X-ray crystal structures of the estrogen-related receptorgamma ligand binding domain in three functional states reveal the molecular basis of small molecule regulation. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 37773–37781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Allan GF; Leng X; Tsai SY; Weigel NL; Edwards DP; Tsai MJ; O’Malley BW Hormone and antihormone induce distinct conformational changes which are central to steroid receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem 1992, 267, 19513–19520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Benkoussa M; Nomine B; Mouchon A; Lefebvre B; Bernardon JM; Formstecher P; Lefebvre P Limited proteolysis for assaying ligand binding affinities of nuclear receptors. Recept. Signal Transduction 1997, 7, 257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Janowski BA; Willy PJ; Devi TR; Falck JR; Mangelsdorf DJ An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR alpha. Nature 1996, 383, 728–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Busch BB; Stevens WC Jr.; Martin R; Ordentlich P; Zhou S; Sapp DW; Horlick RA; Mohan R Identification of a selective inverse agonist for the orphan nuclear receptor estrogenrelated receptor alpha. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47, 5593–5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Coward P; Lee D; Hull MV; Lehmann JM 4-Hydroxytamoxifen binds to and deactivates the estrogen-related receptor gamma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2001, 98, 8880–8884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhang Y; Ma K; Sadana P; Chowdhury F; Gaillard S; Wang F; McDonnell DP; Unterman TG; Elam MB; Park EA Estrogen-related receptors stimulate pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoform 4 gene expression. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 39897–39906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wende AR; Huss JM; Schaeffer PJ; Giguere V; Kelly DP PGC-1alpha coactivates PDK4 gene expression via the orphan nuclear receptor ERRalpha: a mechanism for transcriptional control of muscle glucose metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol 2005, 25, 10684–10694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Araki M; Motojima K Identification of ERRalpha as a specific partner of PGC-1alpha for the activation of PDK4 gene expression in muscle. FEBS J 2006, 273, 1669–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Mootha VK; Handschin C; Arlow D; Xie X; St Pierre J; Sihag S; Yang W; Altshuler D; Puigserver P; Patterson N; et al. Erralpha and Gabpa/b specify PGC-1alpha-dependent oxidative phosphorylation gene expression that is altered in diabetic muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2004, 101, 6570–6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Otto GP; Rathkolb B; Oestereicher MA; Lengger CJ; Moerth C; Micklich K; Fuchs H; Gailus-Durner V; Wolf E; Hrabe de Angelis M Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals for C57BL/6J, C57BL/6N, and C3HeB/FeJ Mice (Mus musculus). J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci 2016, 55, 375–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Villena JA; Hock MB; Chang WY; Barcas JE; Giguere V; Kralli A Orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor alpha is essential for adaptive thermogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2007, 104, 1418–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Reyes NL; Banks GB; Tsang M; Margineantu D; Gu H; Djukovic D; Chan J; Torres M; Liggitt HD; Hirenallur SD; et al. Fnip1 regulates skeletal muscle fiber type specification, fatigue resistance, and susceptibility to muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015, 112, 424–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Stuart CA; Stone WL; Howell ME; Brannon MF; Hall HK; Gibson AL; Stone MH Myosin content of individual human muscle fibers isolated by laser capture microdissection. Am. J. Physiol.: Cell Physiol 2016, 310, C381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Sopariwala DH; Rios AS; Pei G; Roy A; Tomaz da Silva M; Thi Thu Nguyen H; Saley A; Van Drunen R; Kralli A; Mahan K; et al. Innately expressed estrogen-related receptors in the skeletal muscle are indispensable for exercise fitness. FASEB J 2023, 37, No. e22727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Xu W; Billon C; Li H; Hayes M; Yu K; Losby M; Hampton CS; Adeyemi CM; Graves A; Nasiotis E et al. Novel ERR Pan-Agonists Ameliorate Heart Failure Through Boosting Cardiac Fatty Acid Metabolism and Mitochondrial Function, bioRxiv, 2022; DOI: 10.1101/2022.02.14.480431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Nakadai T; Shimada M; Ito K; Cevher MA; Chu CS; Kumegawa K; Maruyama R; Malik S; Roeder RG Two target gene activation pathways for orphan ERR nuclear receptors. Cell Res 2023, 33, 165–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Saracino PG; Rossetti ML; Steiner JL; Gordon BS Hormonal regulation of core clock gene expression in skeletal muscle following acute aerobic exercise. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2019, 508, 871–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Slopack D; Roudier E; Liu ST; Nwadozi E; Birot O; Haas TL Forkhead BoxO transcription factors restrain exerciseinduced angiogenesis. J. Physiol 2014, 592, 4069–4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Holloszy JO; Winder WW Induction of delta-aminolevulinic acid synthetase in muscle by exercise or thyroxine. Am. J. Physiol.: Regul., Integr. Comp. Physiol 1979, 236, R180–R183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wright DC; Han DH; Garcia-Roves PM; Geiger PC; Jones TE; Holloszy JO Exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis begins before the increase in muscle PGC-1alpha expression. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282, 194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Messaoudi I; Handu M; Rais M; Sureshchandra S; Park BS; Fei SS; Wright H; White AE; Jain R; Cameron JL; et al. Long-lasting effect of obesity on skeletal muscle transcriptome. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, No. 411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Hayasaka M; Tsunekawa H; Yoshinaga M; Murakami T Endurance exercise induces REDD1 expression and transiently decreases mTORC1 signaling in rat skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rep 2014, 2, No. e12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Philp A; Schenk S; Perez-Schindler J; Hamilton DL; Breen L; Laverone E; Jeromson S; Phillips SM; Baar K Rapamycin does not prevent increases in myofibrillar or mitochondrial protein synthesis following endurance exercise. J. Physiol 2015, 593, 4275–4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Murakami T; Hasegawa K; Yoshinaga M Rapid induction of REDD1 expression by endurance exercise in rat skeletal muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2011, 405, 615–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]