ABSTRACT

Background

Hypernatremia presents a common complication in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, associated with increased mortality and length of stay. This study investigates the effect of sodium chloride 0.9% compared with glucose 5% solution as the standard intravenous drug diluent on the prevalence of hypernatremia in a medical ICU.

Methods

This is a retrospective before-and-after study comparing two consecutive patient groups before and after the standard drug solvent was changed from sodium chloride 0.9% to glucose 5% solution for compatible medications. A total of 265 adult COVID-19 patients admitted between October 2020 and March 2021 to the study ICU were included, with 161 patients in the timeframe when sodium chloride 0.9% was employed as the standard drug solvent and 104 patients when glucose 5% was used. Routine sodium measurements from arterial and venous blood gases, along with heparinized lithium plasma, were analyzed. The daily sodium concentrations and the prevalence of severe hypernatremia (>150 mmol/l) were assessed during the first 8 days after ICU admission.

Results

Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups. The cumulative volume of intravenous drug diluents was comparable. In the glucose 5% group, about half of the total drug diluent volume was glucose 5% [mean (SD): 2251.6 (2355.4) ml], compared to 135.0 (746.9) ml (P < .001) in the control group. Average sodium concentrations diverged after day two, with the glucose 5% group consistently showing lower sodium levels (mean difference of ∼2.5 mmol/l). Severe hypernatremia occurred less frequently in the glucose 5% group (6.6% vs. 20%).

Conclusion

Glucose 5% solution as the standard intravenous drug solvent significantly reduced sodium concentrations and the occurrence of severe hypernatremia. This simple modification in solvent choice may serve as a preventive strategy against hypernatremia in the ICU. Further prospective research is necessary to determine associated clinical outcomes.

Trial registration

The trial was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00031877).

Keywords: drug diluent, drug solvent, glucose 5%, hypernatremia, sodium chloride 0.9%

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What was known:

Previous studies suggest that the usage of sodium chloride 0.9% as the standard intravenous drug diluent significantly contributes to the development of ICU-acquired hypernatremia.

This study adds:

Our study suggests that switching the default drug diluent for intravenous drugs from sodium chloride 0.9% to glucose 5% can reduce the prevalence of severe hypernatremia (defined as a sodium concentration >150 mmol/l) without a signal for harm.

Potential impact:

Using glucose 5% as the default drug diluent in the ICU instead of sodium chloride 0.9% can help prevent ICU-acquired hypernatremia. This study provides the groundwork for a clinical trial comparing sodium chloride 0.9% and 5% glucose as the default drug diluent.

INTRODUCTION

Hypernatremia, defined by a plasma sodium concentration >145 mmol/l, indicates a significant disruption in total body water and electrolyte balance. It is a common and serious complication among critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), with an incidence of ICU-acquired hypernatremia affecting ∼26% of these patients. This condition adversely affects various physiological functions and is strongly associated with worse outcomes [1, 2].

Observational studies have established that ICU-acquired hypernatremia is associated with prolonged ICU stays [3, 4]. A large-scale study analyzing data from 207 702 patients across 344 ICUs found that patients with ICU-acquired hypernatremia had an average ICU stay of 13.7 days, compared to 5.1 days for those without hypernatremia [3].

Hypernatremia is linked to a higher incidence of delirium [5] and is an independent risk factor for increased mortality in ICU patients. Studies have demonstrated that patients with hypernatremia have a doubled likelihood of death during hospitalization compared to those without hypernatremia. These findings emphasize the critical importance of implementing effective sodium management and prevention strategies to improve patient survival outcomes [3, 6, 7].

The etiology of hypernatremia is multifactorial, with two primary pathomechanisms. The first is a deficit in free water due to increased losses, which can be renal or extrarenal. Renal losses may be driven by diuretics, renal dysfunction, activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, endogenous stress hormones, or polyuria. Extrarenal losses may occur due to fever, diarrhea, excessive sweating, or a negative fluid balance. The second key pathomechanism is decreased water intake, which may result from iatrogenic fluid restriction or drug-induced thirst suppression [8, 9].

Increased sodium intake is another major contributor to hypernatremia. A study conducted in 46 Australian and New Zealand ICUs revealed that the median sodium administration was 224.5 mmol/day, significantly higher than the typical dietary intake of 100 to 150 mmol/day. The primary sources of this excessive sodium were maintenance or replacement intravenous (IV) infusions (69.3 mmol, 30.9% of total sodium intake), IV drug boluses and infusions (46.9 mmol, 20.9%), and enteral nutrition (26.5 mmol, 11.8%) [10]. Consequently, reducing sodium intake by substituting sodium-containing IV fluids with sodium-free alternatives represents a vital opportunity for intervention in preventing hypernatremia.

Clinical management of hypernatremia can be challenging, and evidence-based treatment options are lacking. Current guidelines recommend enteral or parenteral electrolyte-free fluid administration as the first-line treatment, although this recommendation is not backed by data from randomized trials [11]. Pharmacological interventions, such as thiazide diuretics or aldosterone receptor antagonists, have failed to show an effect on sodium levels in small trials [12, 13]. Importantly, no trial has investigated the impact of hypernatremia correction on clinical outcomes.

The lack of evidence-based treatment options, in conjunction with the presumed detrimental effects of hypernatremia, highlight the need for preventive strategies. In this study, we report the effect of replacing sodium chloride 0.9% as the standard intravenous drug solvent with glucose 5% (dextrose 5%) solution on the prevalence of hypernatremia in a medical ICU.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This work is a retrospective observational before-and-after study at a medical ICU of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the largest tertiary care provider in Germany. This study was retrospectively registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00031877). The date of registration was 15 May 2023.

Ethics approval

Procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration. The institutional ethic board approved the study (EA 1/270/21). The need for informed consent from individual patients was waived due to the context of sole retrospective chart review within standard care in accordance with state law.

Study population

All adult patients consecutively admitted to the study ICU between 1 October 2020 to 30 March 2021, were enrolled. During this period, the study ICU exclusively treated patients with COVID-19.

Change of standard drug solvent

Previous 8 January 2021, sodium chloride 0.9% was used as the standard solvent for intravenous drugs in the study ICU, and other solvents were used only if requested by the drug manufacturer (e.g. Amiodarone, Amphotericin B, Levosimendan) or explicitly prescribed by the treating physician (e.g. to treat hypernatremia). To counter the high prevalence of hypernatremia noted in COVID-19 patients the previous standard of care of using sodium chloride 0.9% as the default drug diluent was replaced by a mandate to use glucose 5% for compatible medications on 8 January 2021, as detailed in a standard table of common intravenous (IV) medications and their compatibility with glucose 5% (Supplementary Table S1).

Patients admitted to the study ICU between 15 October 2020 until 7 January 2021 were assigned to the control group. Patients admitted between 8 January 2021 until 30 March 2021 were assigned to the glucose 5% group.

Sodium measurement procedures

This study assessed sodium values derived from heparinized lithium plasma (0.6% of measurements), arterial blood gas (93.5% of measurements), or venous blood gas analysis (5.9% of measurements). To exclude erroneous measurements sodium concentrations deviating ≥6 mmol/l from the previous measurement were excluded. Sodium measurements that deviated by 6 mmol/l or more from the previous value were excluded, leading to the removal of 45 out of 11 627 measurements. Since ∼50% of the total cohort remained in the study ICU for more than eight consecutive days, the analysis was restricted to the first eight days post-admission. Day 0 represents the day of initial ICU admission. For the longitudinal analysis of sodium concentrations, when multiple sodium concentrations were measured within a day (on average 7.9 measurements per day per patient), the mean daily value was calculated.

Sodium concentrations recorded for patients in the control group after 7 January 2021 and in the glucose 5% group after 30 March 2021 were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, sodium measurements obtained after a patient was transferred from the study ICU were excluded to ensure data pertinence to the specific study environment.

Sodium concentrations in non-study ICUs

To explore potential temporal effects, we examined the sodium concentrations of critically ill COVID-19 patients (n = 524) admitted to non-study ICUs (n = 20) at Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin. These analyses were conducted following the same methodology used in the primary study. In these ICUs, the standard solvent for intravenous drugs remained sodium chloride 0.9%. Based on their ICU admission dates and the pre-determined time periods of our study, these patients were stratified into glucose 5% (n = 170) and control groups (n = 354). This approach facilitated the generation of comparative data sets across different ICU environments.

Outcomes

Since this was an exploratory analysis, no primary outcome was predefined. The focus of this study was to assess daily sodium concentrations and the prevalence of severe hypernatremia, defined as a sodium measurement >150 mmol/l, during the first 8 days following ICU admission. The analysis of factors potentially influencing sodium concentrations and the analysis of adverse effects of the 5% glucose administration were also restricted to the first 8 days after ICU admission, including chloride concentration, bicarbonate concentration, distinguished fluid volumes, cumulative fluid balance, insulin dose, glucose concentration, medications, sedation, etc. Bicarbonate levels were monitored to assess the overall acid–base balance in critically ill patients, as changes in sodium and chloride concentrations can affect the body's acid–base balance, potentially leading to metabolic disturbances.

All other outcome parameters investigated in the analysis were not confined to the first 8 days post-admission but were observed for the entire duration of the ICU stay. These additional outcomes included in-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, length of hospital stay, length of ICU stay, proportion of positive blood cultures, incidence of septic shock, ventilator-associated pneumonia, requirement for mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, use of inhaled nitric oxide, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, kidney replacement therapy, vasopressor therapy, and prone positioning.

Handling of treatment crossover

If a patient received treatment in the study ICU during both the control and glucose periods, or if their treatment continued beyond the end of the glucose period, the data on sodium concentrations and on factors influencing sodium concentrations were analyzed only up to the respective cutoff dates (crossovers). Measurements classified as crossovers were excluded from the analysis after the specific cutoff dates of 7 January 2021 for the control group and 30 March 2021 for the intervention group.

Data collection

Structured data were extracted from the hospital's electronic health record (COPRA System GmbH Berlin und Cerner Deutschland GmbH, Berlin) and converted into a research dataset. The extracted data included demographic information, ward movements, administered medications, laboratory parameters, vital signs, clinical scores, microbiological data, and data on organ support therapy, such as mechanical ventilation, kidney replacement therapy, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, among others.

Data stored in free-text fields, such as information on pre-existing comorbidities, home medications, vaccination status, pre-hospital disease course, and complications during the ICU stay, were manually extracted by an ICU-trained physician. During this manual chart review, cases without radiographic findings of viral pneumonia and respiratory failure were excluded to exclude incidental SARS-CoV-2 infection, as efforts were made to focus on patients with COVID-19 pneumonia by excluding those who did not show radiographic signs of pneumonia. Admission data was defined as the first values of a parameter recorded in the 24 hours post-ICU admission.

Statistical analysis

Differences between the control and glucose 5% group regarding baseline characteristics, ICU admission characteristics, ICU disease course, and clinical outcomes were descriptively analyzed. Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean with standard deviation (SD), non-normally distributed continuous variables as medians with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are reported as absolute and relative frequencies. Normality was assessed graphically by plotting the distribution of the data using histograms. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare non-normally distributed variables, and the Welch t-test to compare normally distributed continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test.

The null hypothesis was rejected with a two-sided P value <.05. Owing to the exploratory design of the study, P values were not adjusted for multiple testing. Therefore, the results are interpreted in a hypothesis-generating manner. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, Version R-4.2.2). The following packages were used: tidyverse [14], lubridate [15], gtsummary [16], flextable, and broom.

Declaration of generative AI in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used GPT-4 to improve language and readability of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Between 1 October 2020 and 30 March 2021, 268 patients were admitted to the study ICU with COVID-19 (Fig. 1). Sodium measurements were available for 265 patients. Of these, 161 (60.8%) were admitted between 1 October 2020 and 7 January 2021 (control group), and 104 (39.2%) were admitted between 8 January until 30 March 2021 (glucose 5% group).

Figure 1:

Patient disposition: 268 patients were admitted to the ICU between 1 October 2020 and 30 March 2021. After excluding three patients due to missing sodium measurements, 265 were included in the analysis. In 161 patients (admitted before 8 January 2021) sodium chloride 0.9% and 104 patients (admitted from 8 January 2021) glucose 5% were used as the drug solvents. Patients identified as crossovers were excluded from the sodium analysis beyond the specific cutoff dates of 7 January 2021 for the control group and 30 March 2021 for the intervention group. These crossovers occurred because the standard drug solvent used during their ICU stay was altered.

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 66 (±14 years) in the glucose 5% group and 67 (±15 years) in the control group. The median body mass index (BMI) was 30 (IQR:26–35 kg/m²) in the glucose 5% group and 29 (IQR:26–38 kg/m²) in the controls. The proportions of female patients (34% vs. 34%), obese patients (25% vs. 28%), obesity defined as a BMI > 30 kg/m², and patients documented to be active or former tobacco smokers (15% vs. 18%) were similar in both groups.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Glucose 5% n = 104 | Control n = 161 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66 (14) | 67 (15) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| female | 35 (34%) | 54 (34%) |

| male | 69 (66%) | 107 (66%) |

| BMI (kg/m²), median (IQR) | 30 (26, 35) | 29 (26, 38) |

| BMI > 30, n (%) | 26 (25%) | 45 (28%) |

| Unknown | 52 (50%) | 68 (42%) |

| BMI > 35, n (%) | 13 (13%) | 31 (19%) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl), mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.5) |

| Ever smoked, n (%) | 16 (15%) | 29 (18%) |

| Unknown | 71 (68%) | 101 (63%) |

| Vaccinated, n (%) | 3 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Time from symptoms to hospital admission (days), median (IQR) | 6.0 (2.8, 8.3) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.8) |

| Time from hospital admission to ICU admission (days), median (IQR) | 2 (0, 12) | 2 (1, 8) |

| Referred from inside ICU, n (%) | 23 (22%) | 50 (31%) |

| Referred from outside hospital, n (%) | 36 (35%) | 56 (35%) |

| Referred from outside ICU, n (%) | 26 (25%) | 29 (18%) |

| Intubated prior to admission, n (%) | 27 (26%) | 39 (24%) |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) | 21 (8) | 22 (9) |

| SOFA score, mean (SD) | 4.0 (1.0, 8.0) | 4.5 (1.0, 9.0) |

| SAPS II score, mean (SD) | 39 (13) | 39 (13) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index 0–1, n (%) | 19 (18%) | 28 (17%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index 2–4, n (%) | 30 (29%) | 51 (32%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index > 4, n (%) | 34 (33%) | 66 (41%) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 64 (62%) | 94 (58%) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 37 (36%) | 49 (30%) |

| Respiratory disease, n (%) | 22 (21%) | 42 (26%) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 16 (15%) | 38 (24%) |

| History of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 16 (15%) | 30 (19%) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 15 (14%) | 20 (12%) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 19 (18%) | 26 (16%) |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 10 (9.6%) | 24 (15%) |

| Active malignancy, n (%) | 9 (8.7%) | 7 (4.3%) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 7 (6.7%) | 16 (9.9%) |

| Solid organ transplant, n (%) | 5 (4.8%) | 4 (2.5%) |

Data are presented as number (%). APACHE2, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II. SAPS II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score. SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

The median duration from the onset of COVID-19 related symptoms to ICU admission was 6.0 days (IQR:2.8–8.3 days) in the glucose 5% group and 5.0 days (IQR:2.0–8.8 days) in the control group. The proportions of patients referred from outside ICUs were 25% in the glucose 5% group and 18% in the controls. Patients intubated prior to transfer constituted 26% in the glucose 5% group and 24% in the controls. The vaccination rate was 2.9% in the glucose group vs. 0% in the control group. Regarding the Charlson Comorbidity Index: in the 0–1 score range, 18% were in the glucose group and 17% in the control group; for scores of 2–4, the proportions were 29% and 32%; and for scores >4, 33% and 41%. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (62% vs. 58), diabetes mellitus (36 vs. 30%), and chronic respiratory diseases (21% vs. 26%).

Illness severity scores at ICU admission were balanced between the groups. The median Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score in the glucose 5% group was 4.0 (IQR:1.0, 8.0) compared to 4.5 (IQR:1.0, 9.0) in the controls. The mean Simplified Acute Physiology Score was 39 (±13) in both groups. The mean APACHE II score was 21 (±8) in the glucose 5% group and 22 (±9) in the control group. The baseline creatinine levels [mean 1.5 (±1.2) vs. 1.5 (±1.5)] were nearly identical between the two groups.

Sodium concentrations and prevalence of hypernatremia

Analysis of the mean daily sodium plasma sodium concentrations was conducted (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S2). Sodium data was available from 104 patients in the glucose 5% group and 161 patients in the controls. The median observation time was 6.58 days in the glucose group and 6.28 days in the control group.

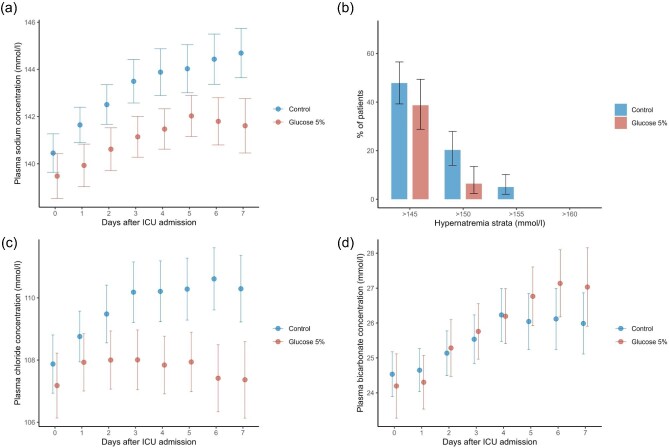

Figure 2:

Sodium concentration, hypernatremia prevalence, chloride, and bicarbonate concentrations in ICU patients. (a) The mean plasma sodium level (±95% CI) during the first 8 days after ICU admission for both the glucose 5% group and the control group. Day 0 represents the day of ICU admission. (b) The prevalence of hypernatremia (±95% CI) stratified by severity for the first 8 days following ICU admission. (c) The mean chloride level (±95% CI). (d) The mean bicarbonate level (±95% CI). In cases where sodium, chloride, or bicarbonate levels were measured multiple times per day for a patient, the daily mean was calculated for analysis.

At baseline (Day 0), the mean sodium values (±SD) were similar between the glucose 5% group and control groups, at 139.5 mmol/l (±5.1) and 140.5 mmol/l (±5.1), respectively (P = .13). Sodium levels demonstrated an increase over time in both groups, however, a divergence in values was noted from day 1 onwards, with the glucose 5% group consistently showing lower levels. The largest difference, of 3.1 mmol/l, was observed on day 7 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S2).

Further analysis was conducted on the prevalence of hypernatremia, categorized by severity (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table S3) and excluding patients with baseline sodium concentrations >145 mmol/l. The glucose 5% group had a lower frequency of hypernatremia, with the most reduction noted in the prevalence of severe hypernatremia. Sodium levels >145 mmol/l were observed in 39% of the glucose 5% group and 50% of controls (P = .18). Levels >150 mmol/l occurred in 6.6% of the glucose group and 20% of controls (P = .019). No patients in the glucose group and 4.1% in the control group had levels exceeding 155 mmol/l.

Hyponatremia of <135 mmol/l was found in 21 patients (28%) in the glucose 5% group and 27 patients (22%) in the control group (P = .5). Hyponatremia of <130 mmol/l was found in three patients (3.9%) in the glucose 5% group and four patients (3.3%) in the controls (P > .99).

In correlation with sodium concentrations, a divergence in chloride concentrations was observed after the second day in the ICU (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table S4). On the other hand, bicarbonate concentrations showed no difference throughout the study period (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Table S5).

Risk factors for hypernatremia

Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of the risk factors for hypernatremia between the two groups. The use of glucocorticoids was similar, with 86% of patients in the control group and 81% in the glucose 5% group receiving glucocorticoids (P = .30). The rates of administration for specific glucocorticoids, such as hydrocortisone (14% vs. 15%, P > .99), dexamethasone (64% vs. 75%, P = .10), prednisolone (14% vs. 12%, P = .66), and methylprednisolone (1.9% vs. 0%, P = .30), were comparable between the groups.

Table 2:

Risk factors for hypernatremia during the first 8 days after ICU admission.

| Glucose 5%, | Control, | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n = 104 | n = 161 | P value |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 84 (81%) | 139 (86%) | .30 |

| Hydrocortisone, n (%) | 15 (14%) | 24 (15%) | >.99 |

| Dexamethasone, n (%) | 67 (64%) | 120 (75%) | .10 |

| Prednisolone, n (%) | 15 (14%) | 19 (12%) | .66 |

| Methylprednisolone, n (%) | 2 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | .30 |

| Sedation, n (%) | 47 (45.2%) | 67 (41.6%) | .66 |

| Duration sedation (days), mean (SD) | 3.1 (3.3) | 3.5 (3.4) | .34 |

| Invasive ventilation, n (%) | 47 (45.2%) | 66 (41.0%) | .58 |

| Duration invasive ventilation (days), mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.5) | 6.2 (2.2) | .48 |

| Fever, n (%) | 59 (57%) | 105 (65%) | .14 |

| Body temperature (°Celsius), mean (SD) | 37.0 (0.6) | 37.0 (0.7) | |

| Furosemide, n (%) | 59 (56.7%) | 93 (57.8%) | .97 |

| Furosemid, cumulative dose (mg), mean (SD) | 291.2 (286.3) | 343.9 (321.2) | .31 |

| Torasemide, n (%) | 18 (17.4%) | 28 (17.3%) | >.99 |

| Torasemide, cumulative dose (mg), mean (SD) | 88.1 (233.1) | 81.1 (259.9) | .93 |

| Cumulative fluid balance (ml), mean (SD) | 746.1 (4624.7) | 494.9 (4754.2) | .74 |

| Cumulative diuresis (ml), mean (SD) | 8596.4 (6828.6) | 7872.5 (6035.6) | .37 |

Data are presented as number (%). The first 8 days after ICU admission were analyzed. P value was calculated using the chi square test for categorical data and the Welch t-test for continuous variables. Fever was defined as a temperature >38.3°C. Sedation was defined as the continuous administration of one of the following drugs: Esketamin, midazolam, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, sufentanil, propofol, and lormetazepam.

Sedation was administered to a similar proportion of patients in both groups (56% in the glucose 5% group vs. 58% in the control group, P = .85), with no notable difference in the duration of sedation [mean (SD): 3.1 (3.3) days vs. 3.5 (3.4) days, P = .34]. The proportion of patients requiring invasive ventilation was also comparable between the groups (45.2% vs. 41.0%, P = .58), as was the duration of invasive ventilation [mean (SD): 5.9 (2.5) days vs. 6.2 (2.2) days, P = .48].

The incidence of fever, defined as a body temperature >38.3°C, was similar between the groups (65% in the glucose 5% group vs. 57% in the control group, P = .14), as was the mean body temperature during the first 8 days after ICU admission [mean (SD): 37.0 (0.6)°C vs. 37.0 (0.7)°C].

The proportion of patients receiving furosemide was nearly identical between the glucose 5% group and the control group (56.7% vs. 57.8%, P = .97), with no apparent difference in the cumulative dose administered [mean (SD): 291.2 (286.3) mg vs. 343.9 (321.2) mg, P = .31]. Similarly, the use of torasemide was consistent across both groups (17.4% vs. 17.3%, P > .99), with cumulative doses showing no meaningful variation [mean (SD): 88.1 (233.1) mg vs. 81.1 (259.9) mg, P = .93].

The cumulative diuresis over the first 8 days was slightly higher in the glucose 5% group, but this difference was not statistically significant [mean (SD): 8596.4 (6828.6) ml vs. 7872.5 (6035.6) ml, P = .37]. The cumulative fluid balance was nearly identical between the two groups (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3:

Volume of intravenous drug diluents, daily fluid balance, glucose concentration and insulin dose. Shown are (a) the cumulative volume of intravenous drug diluents (ml), (b) the cumulative total fluid balance (ml) (mean ± 95% CI), (c) the glucose levels (mg/dl) (mean ± 95% CI), and (d) the insulin dose (IU) (mean ± 95% CI) in the glucose 5% and control group. If glucose levels were measured multiple times per day the highest value was used to calculate the mean.

Volume of intravenous drug diluents, daily fluid balance, plasma glucose concentrations and insulin dose

The analysis of fluids administered during the first 8 days following ICU admission is summarized in Table 3. For each type of fluid, cumulative volumes are reported only for patients who actually received the respective fluid, rather than for the entire cohort.

Table 3:

Fluids administered during the first 8 days after ICU admission.

| Characteristic | Glucose 5%, n = 104 | Control, n = 161 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative total volume of intravenous drug diluents (ml), mean (SD) | 4429.6 (4270.6) | 4177.9 (3984.6) | .64 |

| Cumulative volume glucose 5% used as an intravenous drug diluent (ml), mean (SD) | 2251.6 (2355.4) | 135.0 (746.9) | ≤.001 |

| Balanced crystalloids, n (%) | 68 (65.4%) | 106 (65.8%) | 1.0 |

| Balanced crystalloids, cumulative volume (ml), mean (SD) | 2287.1 (2011.2) | 2207.9 (2301.7) | .82 |

| Enteral water, n (%) | 41 (25.5%) | 19 (18.3%) | .24 |

| Enteral water, cumulative volume (ml), mean (SD) | 2743.7 (2014.9) | 2274.4 (1724.9) | .36 |

| Sodium chloride 0.9%, n (%) | 1 (0.96%) | 10 (6.2%) | .73 |

| Sodium chloride 0.9%, cumulative volume (ml), mean (SD) | 41.2 (NA) | 409.5 (975.7) | .73 |

| Glucose 5% infusion, n (%) | 3 (2.9%) | 16 (9.9%) | .05 |

| Glucose 5%, cumulative volume (ml), mean (SD) | 792.0 (505.7) | 1402.2 (2097.2) | .63 |

| Sodium bicarbonate 8.4%, n (%) | 3 (2.9%) | 4 (2.4 %) | 1.0 |

| Sodium bicarbonate 8.4%, cumulative volume (ml), mean (SD) | 177.9 (120.3) | 104.2 (4.8) | .4 |

| Parenteral nutrition, n (%) | 5 (4.8%) | 8 (5.0%) | >.99 |

| Parenteral nutrition, cumulative volume (ml), mean (SD) | 4291.1 (2423.2) | 2165.8 (2737.3) | .18 |

| Enteral feeding, n (%) | 60 (57.7%) | 92 (57.1%) | >.99 |

| Enteral nutrition, cumulative volume (ml) | 3264.0 (2383.7) | 3284.0 (2336.2) | .83 |

Data are presented as number (%). The first 8 days after ICU admission were analyzed. P value was calculated using the chi square test for categorical data and the Welch t-test for continuous variables.

The cumulative volume of intravenous drug diluents was similar between the glucose 5% group and the control group [mean (SD): 4429.6 (4270.6) ml vs. 4177.9 (3984.6) ml, P = .64] (Fig. 3a).

Approximately half of the cumulative total drug diluents administered in the glucose 5% group was glucose 5% instead of sodium chloride 0.9% whereas the control group received only a negligible amount of glucose 5% as a drug diluent (mean (SD) 2251.6 (2355.4) ml vs. 135.0 (746.9) ml, P ≤ .001).

The use of balanced crystalloids was nearly identical in both groups, with 68 patients (65.4%) in the glucose 5% group and 106 patients (65.8%) in the control group (P = 1.0). The cumulative volume of balanced crystalloids administered also showed no difference between groups [mean (SD): 2287.1 ml (2011.2) vs. 2207.9 ml (2301.7), P = .82].

Enteral water was given to a higher proportion of patients in the glucose 5% group compared to the control group [41 patients (25.5%) vs. 19 patients (18.3%), P = .24], with similar cumulative volumes administered [mean (SD): 2743.7 ml (2014.9) vs. 2274.4 ml (1724.9), P = .36].

The use of sodium chloride 0.9% was infrequent, with one patient (0.96%) in the glucose 5% group and 10 patients (6.2%) in the control group (P = .73). The cumulative volumes for those who received it were low and comparable [mean (SD): 41.2 ml (NA) vs. 409.5 ml (975.7), P = .73]. Glucose 5% infusion was more common in the control group (16 patients, 9.9%) compared to the glucose 5% group (three patients, 2.9%), although the cumulative volume among recipients did not differ significantly [mean (SD): 792.0 ml (505.7) vs. 1402.2 ml (2097.2), P = .63] (Fig. 3b).

Sodium bicarbonate 8.4% was rarely used, with three patients (2.9%) in the glucose 5% group and four patients (2.4%) in the control group (P = 1.0), and the cumulative volumes administered were similar [mean (SD): 177.9 ml (120.3) vs. 104.2 ml (4.8), P = .4].

Parenteral nutrition was administered to a small proportion of patients in both groups (4.8% vs. 5.0%, P > .99), with a higher cumulative volume observed in the glucose 5% group [mean (SD): 4291.1 ml (2423.2) vs. 2165.8 ml (2737.3), P = .18].

Enteral feeding was similarly distributed between the two groups, with 60 patients (57.7%) in the glucose 5% group and 92 patients (57.1%) in the control group (P > .99), and the cumulative volumes of enteral nutrition were also comparable [mean (SD): 3264.0 ml (2383.7) vs. 3284.0 ml (2336.2), P = .83].

No relevant differences were observed between the glucose 5% and control groups in terms of the daily cumulative insulin doses (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table S8) and plasma glucose concentrations (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Table S9).

Sodium concentrations in non-study ICUs

To investigate whether the observed difference in sodium concentrations between the glucose 5% and control group was attributable to a temporal effect other than the intervention, i.e. change in practice pattern, sodium concentrations were analyzed in COVID-19 patients treated in other ICUs (n = 20) at Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, where the standard drug solvent remained unchanged (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S10). Data from 524 patients were available, including 354 patients admitted between 15 October 2020 and 7 January 2021, and 170 admitted between 8 January and 30 March 2021. No decrease in sodium concentrations was observed during the glucose 5% period in non-study ICUs.

Figure 4:

Sodium concentrations in study and non-study ICUs during control and glucose 5% time periods. The figure displays the mean plasma sodium level (±95% CI) for the first 8 days following admission to the ICU in both study and non-study ICUs during the control and glucose 5% time periods. In non-study ICUs, sodium chloride 0.9% continued to be the standard drug solvent. Day 0 represents the day of ICU admission.

Outcomes, complications, and treatments

Outcomes, complications, and important treatments during the ICU stay are summarized in Supplementary Table S11. The survival in both groups was similar both regarding ICU mortality (32% vs. 35%) and in-hospital mortality (35% vs. 40%). No relevant difference was found in the prevalence of septic shock (35% vs. 36%), ventilator-associated pneumonia (30% vs. 26%), the rate of positive blood cultures (40% vs. 37%), and the proportion of patients with a hyperglycemic event (79% vs. 78%).

Of note, patients in the glucose 5% group had longer ICU length of stays (LOS) with a median of 17 days (IQR:7, 45) compared to 11 days (IQR:6, 27) in the control group. Furthermore, the total hospital LOS was longer with a median of 24 days (IQR:12, 57) vs. 21 days (IQR:11, 35). Numerically more patients in the glucose 5% group (57% vs. 44%) received proning therapy.

The LOS in the subgroup of patients not treated with proning was similar between the groups (Supplementary Table S12), indicating that the LOS difference is possibly attributable to the higher proportion of patients proned in the glucose 5% group.

Other outcomes detailed in Supplementary Table S11 showed a similar distribution in both groups.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the effect of a practice change comprising a reduction in sodium content in intravenous drug diluents by using glucose 5% instead of sodium chloride 0.9% on the prevalence of hypernatremia in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Our results demonstrate a relevant reduction in sodium levels and the prevalence of severe hypernatremia.

The baseline characteristics of patients in both groups were comparable, with no relevant differences observed in demographics, comorbidities, and illness severity scores. Additionally, no substantial differences were found regarding risk factors for hypernatremia and the volume of intravenously administered drug diluents. These findings indicate that the observed reduction in hypernatremia in the glucose 5% group was likely attributable to the low-sodium intravenous drug diluent strategy.

Our findings align with previous studies that reported similar outcomes when assessing the effects of modifying the standard drug diluent [17, 18]. A study from a Japanese center, which explored the opposite intervention (switching the standard drug diluent from glucose 5% to sodium chloride 0.9%), also reported lower sodium and chloride levels during the period when glucose 5% was used for drug dilution [17]. The effect size of these changes mirrored those in our study. Similarly, a US study that examined the switch from sodium chloride 0.9% to glucose 5% reported a lower incidence of hyperchloremia and lower chloride levels in the glucose 5% group [18].

Unlike in previous studies, our research offers significant added value by not only analyzing the detailed volume of intravenous drug diluents and daily fluid balance, but also by thoroughly examining additional critical factors, such as the use of medications (including diuretics and steroids), the duration of sedation and mechanical ventilation, and the presence of fever in both patient groups (Table 2).

Over the 8-day observation period in our study, switching to glucose 5% as the standard diluent reduced sodium chloride 0.9% use by an average of 2251.6 ml, preventing the administration of ∼347 mmol of sodium (20 g), or ∼43 mmol (2.5 g) of sodium per day. Our study's findings align closely with the conclusions drawn by Choo et al., who identified high sodium input from 0.9% saline used to dilute drugs and maintain catheter patency as a modifiable risk factor for ICU-acquired hypernatremia. These results add to the mounting evidence suggesting that using glucose 5% as a drug diluent could be an effective strategy to prevent sodium overloading and ICU-acquired hypernatremia, targeting a key modifiable risk factor identified in previous research.

Our study has strengths and limitations. The strengths included that the study was performed in a homogenous population of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Baseline parameters and risk factors for hypernatremia were balanced between the groups. Moreover, the same variant of the SARS2 Coronavirus (wild type) was prevalent during both time periods. However, the inclusion of only COVID-19 patients reduces the generalizability of our findings.

Before-and-after study designs are vulnerable to confounding variables that may have changed over time and could have influenced the observed outcomes, such as temporal trends and unintended changes in management protocols or disease characteristics. To account for this, our study examined sodium concentrations in non-study ICU, where the standard drug solvent remained unchanged. We found no difference in plasma sodium concentrations between the time periods supporting the notion that the reduction in hypernatremia in the glucose 5% group was primarily due to the low-sodium intravenous drug diluent strategy. Furthermore, the single-center design of our study may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings or populations.

Although our study was not designed to focus on clinical endpoints and our findings should be treated as hypothesis generating, it must be noted we found no evidence for improved clinical outcomes in the glucose 5% group. Despite a significant reduction in hypernatremia—which previous studies have linked with prolonged ICU stays [3, 4]—the group receiving 5% glucose had a notably longer median ICU stay of 6 days compared to the control group (17 vs. 11 days) and an extended total hospital stay by 3 days (24 vs. 21 days). Additionally, a higher percentage of patients in the glucose 5% group received proning therapy (57% vs. 44%). Since these outcomes were not adjusted for multiple testing and our study was underpowered for this outcome, we consider this to be a chance finding. Nevertheless, without a randomized trial, we cannot rule out the possibility that the switch to 5% glucose contributed to adverse effects, such as increased extravascular lung water, which could worsen ARDS, necessitate more proning therapy, and extend the length of stay.

Moreover, it is important to note that the control group was treated from October to January, while the glucose 5% group was treated from January to April, introducing potential seasonal differences that could have affected the length of stay. Furthermore, similar studies comparing hypotonic versus isotonic maintenance fluids did not indicate a prolonged length of stay [17, 18]. During the pandemic, variations in rehabilitation clinic capacities likely influenced the timing of patient discharges from intensive care, suggesting that length of stay may not be a reliable endpoint in our analysis.

Furthermore, our study offers a comprehensive analysis of the potential adverse effects associated with the use of glucose 5%, which have not been thoroughly examined in previous research. While our findings regarding ICU and in-hospital mortality align with existing studies, our research goes further by exploring additional outcomes. We found no notable differences between the groups in the prevalence of septic shock, ventilator-associated pneumonia, the incidence of positive blood cultures, or the occurrence of hyperglycemic events. This extensive analysis highlights the safety profile of glucose 5% as a drug diluent in critically ill patients, addressing gaps left by earlier studies.

In summary, our study contributes further evidence to the hypothesis that sodium chloride 0.9% as a drug diluent contributes significantly to ICU-acquired hypernatremia providing the groundwork for a randomized trial to evaluate the impact of glucose 5% as the universal carrier solution on clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J-H.B. Hardenberg is participant in the BIH Charité Junior Digital Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH). M.M. is a fellow of the BIH—Charité Digital Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité, and the German Research Foundation (DFG). We acknowledge support the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Contributor Information

Jan-Hendrik B Hardenberg, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany; Berlin Institute of Health at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, BIH Biomedical Innovation Academy, BIH Charité Junior Digital Clinician Scientist Program, Charitéplatz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Julius Valentin Kunz, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Kerstin Rubarth, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Biometry and Clinical Epidemiology, Charitéplatz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Mirja Mittermaier, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Infectious Diseases, Respiratory Medicine and Critical Care Medicine, Charitéplatz 1, Berlin, Germany; Berlin Institute of Health at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, BIH Biomedical Innovation Academy, BIH Charité Digital Clinician Scientist Program, Charitéplatz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Mareen Pigorsch, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Biometry and Clinical Epidemiology, Charitéplatz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Felix Balzer, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Medical Informatics, Charitéplatz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Martin Witzenrath, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Infectious Diseases, Respiratory Medicine and Critical Care Medicine, Charitéplatz 1, Berlin, Germany; German Center for Lung Research (DZL), Berlin, Germany.

Ricarda Merle Hinz, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Roland Körner, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Kai-Uwe Eckardt, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Felix Knauf, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Carl Hinrichs, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany.

Philipp Enghard, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Department of Nephrology and Medical Intensive Care, Augustenburger Platz 1, Berlin, Germany; German Rheumatism Research Center Berlin (DRFZ), An Institute of the Leibniz Foundation, Berlin, Germany.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This study was funded by internal resources. J.-H.B. Hardenberg is participant in the BIH Charité Junior Digital Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH). M.M. is a fellow of the BIH—Charité Digital Clinician Scientist Program funded by the Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité, and the German Research Foundation (DFG).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

P.E., C.H., J.V.K., and J.H.H. conceived the study and its design, had full access to the data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis. J.H.H. collected and processed the data. M.M. contributed to data collection. P.E., C.H., J.V.K., K.R., and J.H.H. contributed to data analyses. P.E., C.H., J.V.K., K.R., K.U.E., M.P., F.K., and J.H.H. contributed to data interpretation. P.E., C.H., J.V.K., K.U.E., and J.H.H. wrote the primary draft of the manuscript. M.W., F.B., F.K., M.P., R.K., and R.H. edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used in this study cannot be made available in the manuscript, the supplemental files, or in a public repository due to German data protection laws (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adrogué JH, Madias EN. Hypernatremia. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1493–9. 10.1056/NEJM200005183422006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stelfox H, Ahmed BS, Khandwala F et al. The epidemiology of intensive care unit-acquired hyponatraemia and hypernatraemia in medical-surgical intensive care units. Critical Care 2008;12:R162. 10.1186/cc7162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waite DM, Fuhrman AS, Badawi O et al. Intensive care unit–acquired hypernatremia is an independent predictor of increased mortality and length of stay. J Crit Care 2013;28:405–12. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hu B, Han Q, Mengke N et al. Prognostic value of ICU-acquired hypernatremia in patients with neurological dysfunction. Medicine 2016;95:e3840. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ali MA, Hashmi M, Ahmed W et al. Incidence and risk factors of delirium in surgical intensive care unit. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2021;6:e000564. 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olsen MH, Møller M, Romano S et al. Association between ICU-acquired hypernatremia and in-hospital mortality: data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III and the Electronic ICU Collaborative Research Database. Crit Care Explor 2020;2:e0304. 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. S O'Donoghue SD, Dulhunty JM, Bandeshe HK et al. Acquired hypernatraemia is an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Anaesthesia 2009;64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoorn EJ, Betjes MG, Weigel J et al. Hypernatraemia in critically ill patients: too little water and too much salt. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant 2008;23:1562–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfm831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lindner G, Funk GC. Hypernatremia in critically ill patients. J Crit Care 2013;28:216.e11–20. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bihari S, Peake SL, Seppelt I et al. Sodium administration in critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand: a multicentre point prevalence study. Crit Care Resusc 2013;15:294–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chand R, Chand R, Goldfarb DS. Hypernatremia in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2022;31:199–204. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Apte Y, Bellomo R, Warrillow S et al. Pilot randomised double-blind controlled trial of high-dose spironolactone in critically ill patients receiving a frusemide infusion. Crit Care Resusc 2008;10:306–11. 10.1016/S1441-2772(23)01890-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van IJzendoorn MM, Buter H, Kingma WP et al. Hydrochlorothiazide in intensive care unit-acquired hypernatremia: a randomized controlled trial. J Crit Care 2017;38:225–30. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Software 2019;4:1686. 10.21105/joss.01686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grolemund G, Wickham H. Dates and times made easy with lubridate. J Stat Softw 2011;40:1–25. https://www.jstatsoft.org/v40/i03/ [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sjoberg DD, Whiting K, Curry M et al. Reproducible summary tables with the gtsummary Package. R J 2021;13:570. 10.32614/RJ-2021-053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aoyagi Y, Yoshida T, Uchino S et al. Saline versus 5% dextrose in water as a drug diluent for critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study. J Intens Care 2020;8:69. 10.1186/s40560-020-00489-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Magee AC, Bastin TLM, Laine EM et al. Insidious harm of medication diluents as a contributor to cumulative volume and hyperchloremia: a prospective, open-label, sequential period pilot study. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1217–23. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study cannot be made available in the manuscript, the supplemental files, or in a public repository due to German data protection laws (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz).