Abstract

Introduction

Two thirds of Americans infected with chronic hepatitis B are unaware of their infection. In March 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended moving from risk-based to universal adult chronic hepatitis B screening. In April 2022, Stanford implemented chronic hepatitis B universal screening discussion alerts for primary care providers.

Methods

After 6 months, the authors surveyed 143 primary care providers at 13 Stanford primary care clinics about universal chronic hepatitis B screening acceptability and implementation feasibility. They conducted semistructured interviews with 15 primary care providers and 5 medical assistants around alerts and chronic hepatitis B universal versus risk-based screening.

Results

Forty-five percent of surveyed primary care providers responded. A total of 63% reported that universal screening would identify more patients with chronic hepatitis B. Before implementation, 77% ordered 0–5 chronic hepatitis B screenings per month. After implementation, 71% ordered >6 screenings per month. A total of 66% shared that universal screening removed the stigma around discussing high-risk behaviors. Interview themes included (1) low clinical burden, (2) current underscreening of at-risk groups, (3) providers preferring universal screening, (4) patients accepting universal screening, and (5) ease of chronic hepatitis B alert implementation.

Conclusions

Consistent with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, implementing universal chronic hepatitis B screening in primary care clinics in Northern California was feasible, was acceptable to providers and patients, eased health maintenance burdens, and improved clinic workflows.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, universal screening, implementation, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a treatable and vaccine-preventable blood-borne viral illness. It is a leading cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer and causes 887,000 global deaths yearly.1 In America, between 862,000 and 2.4 million people are living with CHB; yet, two thirds are unaware of their infection.2,3 The primary method to identify persons with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is through serologic testing for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).4 Prior to 2023, routine CHB screening has been risk based, recommended for pregnant women, infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, household contacts and sex partners of HBV-infected persons, persons born in populations or geographic regions with HBsAg prevalence ≥2%, persons who are the source of blood or bodily fluid exposures that might warrant postexposure prophylaxis, persons infected with HIV, and men who have sex with men.5 Risk-based screening necessitates complex, stigmatizing conversations with patients around sexual practices and inquiry about personal/parental country of origin.6 Minorities were also underscreened for CHB, with non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, and Latinx individuals screened 3–5 times less often than non-Hispanic White people.7,8

In 2022, California AB789 legislation mandated that all primary care providers (PCPs) offer hepatitis B and C screening to California adults.9 In March 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended universal, 1-time hepatitis B screening for adults aged >18 years with a panel of 3 blood tests (HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antibody, hepatitis B core antibody) to identify patients (1) with active CHB, (2) with cleared prior hepatitis B infection at risk for reactivation, and (3) not immune to hepatitis B.10 Adult 1-time universal hepatitis B screening could avert 7.4 cases of compensated cirrhosis, 3.3 cases of decompensated cirrhosis, 5.5 hepatocellular carcinomas, 1.9 liver transplantations, and 10.3 HBV-related deaths per 100,000 people.3 As such, universal CHB screening could save $263,000 per 100,000 adults screened.11,12 However, transitioning to universal screening may pose logistic burdens for busy PCPs and may not be well received by patients who perceive CHB as a stigmatizing lifestyle illness. In addition, Medicare requires adding the risky-lifestyle ICD-10 billing code problems related to lifestyle (Z72.89) for screening reimbursement, even if prompted by country of origin.13 Anecdotally, some PCPs report reluctance to order CHB screening because patients complain about this Medicare code.

In April 2022, on the basis of California legislation and developing CDC guidelines, Stanford Medicine and Stanford Medical Partners implemented a novel universal CHB screening alert through their electronic medical record (EMR) to prompt PCPs CHB screening discussions with patients. Six months after implementation, the study team evaluated the acceptability and feasibility of CHB universal screening, assessed through provider surveys and qualitative interviews with providers and medical assistants (MAs).

METHODS

Study Population

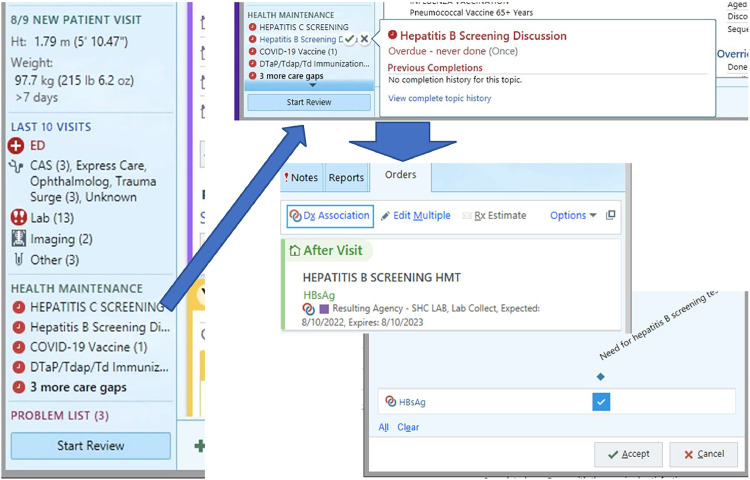

In April 2022, the Stanford Health Maintenance Working Group released a new CHB screening health maintenance alert to Stanford primary care clinics (Figure 1) through their EMR (Epic, Verona, WI) to prompt discussion of CHB testing. Stanford primary care clinics include Stanford Division of Primary Care and Population Health (PCPH) and Stanford Medical Practices (SMP) clinics. PCPH clinics include 6 general, 3 employer-based, 1 senior care, and 1 specialty primary care clinics, with 126 providers (MD/DOs and advanced practice providers) and with approximately 60,000 patients in 2022. SMP clinics include 75 general primary care clinics with 147 providers and approximately 150,000 patients. Seven PCHP clinics and 2 SMP clinics participated in program evaluation.

Figure 1.

Provider view of Epic health maintenance alerts for CHB screening.

Electronic medical record screenshots are included with permission from Epic Systems Corporation (2023).

CHB, chronic hepatitis B.

CHB was screened with a HBsAg blood test, which is positive during active viral replication. The alert featured 1-click ordering, was not a pop up, and was displayed with other alerts (immunizations, cancer screening) for qualified patients. Qualified patients included adults aged ≥18 years without prior hepatitis B diagnosis, without liver cancer, and without prior HBsAg test (regardless of hepatitis B immunization status). Since May 2022, test ordering autopopulated the associated ICD-10 diagnosis (Z11.59, encounter for screening for other viral diseases), including a second code (Z72.89, other problems related to lifestyles) for Medicare patients. The alert was considered done if HBsAg was ordered or prior HBsAg results entered. Clinical staff could postpone (but not delete) CHB screening if currently inappropriate (Figure 2) to allow reconsideration after planned CDC 2023 guideline updates.

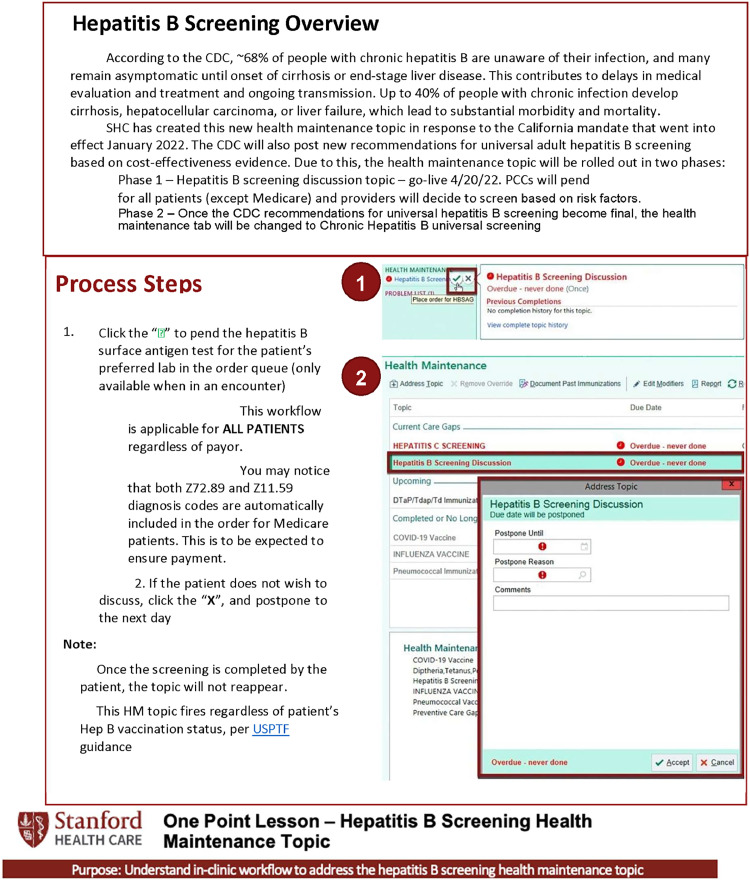

Figure 2.

One Point Lesson training tool for PCP and medical assistance for universal CHB screening discussion.

Electronic medical record screenshots are included with permission from Epic Systems Corporation (2023) and the One Point Lesson with the permission of the Stanford Ambulatory Quality and Population Health Team.

CHB, chronic hepatitis B; PCP, primary care providers.

From March–May 2022, MAs were trained during clinic meetings to review CHB screening while rooming patients, as part of health maintenance, for in-person and telemedicine visits. PCPs learned about CHB screening rationale and EMR workflow during clinic meetings and with emailed communication through materials such as those featured in Figure 2.

This evaluation was considered a quality improvement project and not human subjects research by the Stanford IRB (IRB Protocol 66078).

Measures

Six months after the implementation of the new universal CHB screening maintenance alert, in October 2022, the authors surveyed PCPs at Stanford and SMP primary care clinics with a 34-item anonymous online survey regarding their CHB workflow (6 questions, including time to order/review CHB results), perceptions about alert utility/drawbacks (12 questions), patient reactions/perspectives (5 questions), screening outcomes (7 questions), and future EMR modifications. Participants were reminded twice through e-mail in a period of 3 months to complete the survey. The survey was open from early October 2022 to early January 2023 (Table 1, full survey).

Table 1.

Physician Survey About the Universal CHB Alert Regarding Their CHB Workflow, Perceptions About Alert Utility/Drawbacks, Patient Reactions/Perspectives, Screening Outcomes, and Future EMR Modifications

| Category | Question |

|---|---|

| General provider information | 1. What is your specialty? 2. On average, how many half days a week are you in your own primary care clinic? (not teaching clinic) On average, how many patients do you see per half day? How long have you been in clinical practice (since residency or fellowship)? |

| Using the HM Due reminder | 1. Have you used the new hepatitis B HM Due reminder activated in April 2022? Have you used the one click ordering for hepatitis B (green check mark next to the HM Due topic)? Prior to the implementation of the HM Due reminder, how many times in a typical month would you order hepatitis B screening for your patients? If yes to Q1: Since the implementation of the hepatitis B HM Due reminder, how many times in a typical month have you ordered hepatitis B screening for your patients? Are your MAs involved with the initial patient discussion and/or the ordering process for hepatitis B screenings? If yes, what do your MAs do? The current HM Due reminder recommends discussions of hepatitis B screening with patients. When the hepatitis B HM Due reminder is triggered, what do you usually do? If you discuss hepatitis B screening, how do your patients usually react/reply? If patients do not want to be screened, what are the reasons? How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements? ⋅ In general, HM Due reminders are helpful The hepatitis B HM Due reminder is helpful The hepatitis B screening one-click order is easy to use My practice's process for using the hepatitis B HM Due reminder is straightforward Patients are open to conversations about hepatitis B Patients perceive hepatitis B as having a special stigma I need more support to implement this HM Due reminder In general, how much time does it take to: Open and review HM Due reminders Discuss hepatitis B screenings with your patients Order hepatitis B screening follow-up on hepatitis B screening results if negative Follow-up on hepatitis B screening results if positive |

| Risk-based versus universal hepatitis B screening | When screening for chronic active hepatitis B, which tests would you usually order? Which approach would you prefer when screening for hepatitis B? How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements? “In comparison to risk-based screening,…” Universal screening involves more unnecessary testing Universal screening is more straightforward because I don't have to look through all the risk categories Universal screening will take less time during my clinic visits Universal screening will help me identify more patients with hepatitis B Universal screening will prevent significantly more cirrhosis and liver cancer Universal screening removes the stigma of identifying a high-risk group Universal screening is more cost-effective |

| Future of hepatitis B screening (open-ended questions) | What types of questions do your patients have around chronic hepatitis B (screening)? How can we make the HM Due reminder and clinical process better? |

CHB, chronic hepatitis B; EMR, electronic medical record; MA, medical assistant.

The study team conducted 20 semistructured interviews with snowball convenience sampling of PCPs (6 PCPH [12 PCPs] and 2 SMP [3 PCPs] clinics) and MAs (3 PCPH clinics [5 MAs]) over a period of 5 months between July and December 2022. PCP and MA interviews explored viewpoints around universal CHB alert implementation and PCP viewpoints on CHB universal versus risk-based screening. Using an interview guide, the study team conducted interviews until thematic saturation. Interviews were conducted by 4 trained research assistants and faculty. Twenty interviews lasted 20–30 minutes, mainly by video (1 by phone). To minimize reporting bias, information would only be shared in aggregate beyond the research analytic team.

Statistical Analysis

Survey responses were aggregated across providers and MAs by content area (means and SDs). For qualitative analysis, video recordings were transcribed, with detailed interview notes. The study team analyzed transcripts/notes using a rapid cycle methodology with initial consensus coding (20% of transcripts) followed by individual coding and spot checking (80%).14 Final themes emerged through consensus discussion among the analytic team (RVC, SS, TVD, AJ, AP, MS).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics per clinic were representative of the Bay Area (53%–60% female, 30%–64% non-Hispanic white, 5%–13% Hispanic, 16%–40% Asian, 2%–6% African American), and clinical characteristics were similar between clinics, apart from senior care which had longer visits. PCPH clinics had an average of 19 (SD=15.3) primary care providers per site, compared with 11 (SD=4.0) for the SMP clinics. PCHP clinics also had an average of 9 (SD=3.9) Medical Assistants per site, whereas SMP clinics had 15 (SD=1.5). The average number of patients seen per half-day was 42 (SD=21.7) for PCPH clinics and 69 (SD=1.0) for SMP clinics. Additionally, the patient populations across both clinic types showed similar composition in sex, race, and ethnicity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and patient demographics of Stanford Primary Care and University Medical Partners clinics that have implemented the HM Due reminder tool.

| Characteristics | Stanford primary care clinics (n = 7) | University medical partners (n = 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary care providers, mean (SD) | 19 (15.3) | 11 (4.0) |

| Medical assistants, mean (SD) | 9 (3.9) | 15 (1.50) |

| Patients seen per half-day, mean (SD) | 42 (21.7). | 69 (1.0) |

| Patient sex, mean (SD) | ||

| % Female | 56.5% (3.9%) | 56.5% (1.8%) |

| % Male | 43.4% (3.9%) | 43.5% (1.8%) |

| % Other | 0.04% (0.08%) | 0.01% (0.01%) |

| Patient race and ethnicity, mean (SD) | ||

| % Non-Hispanic White | 44.4% (8.5%) | 53.9% (10.0%) |

| % Non-Hispanic Asian American | 28.8% (5.5%) | 17.4% (1.4%) |

| % Hispanic | 10.7% (2.3%) | 8.2% (3.0%) |

| % Non-Hispanic African American | 3.3% (0.8%) | 3.7% (2.4%) |

| % Other | 12.9% (1.6%) | 16.8% (3.3%) |

Fifty-eight of 126 (46%) Stanford PCPH providers completed the surveys, and 7 of 17 SMP providers (41%) completed the surveys. Survey respondents included 88.4% physicians and 11.6% advanced practice providers, who saw on average 7.66 patients per half day with 5.1 half-day blocks of primary care clinics per week and had been practicing for 12.5 years. Of 65 respondents, 41 (63%) felt that the universal screening would help identify more patients with hepatitis B. Before universal CHB screening, 50 (77%) respondents reported ordering 0–5 hepatitis B screens during typical months (median=1–2), whereas only 15 (23%) respondents reported ordering >6 screenings per month. After implementation, 46 (71%) reported ordering >6 screenings per month. Most respondents (75%) reported that universal screening was convenient and eliminated reviewing multiple hepatitis B risk categories per patient. Most providers (66%) shared that universal screening removed stigma around discussion of high-risk behaviors (sexual/intravenous drug transmission), country of origin, and prior parental infection. During discussions, 52 (80%) respondents reported spending <5 minutes opening/reviewing EMR reminders, and 52 respondents (80%) reported spending <5 minutes ordering hepatitis B screening.

The study team identified the following 7 major themes on the basis of 20 interviews. Table 3 highlights representative quotes from providers and medical assistants.

-

•

Low clinical burden: Providers generally spent 1–2 minutes discussing CHB screening, bundled with standard health maintenance discussions, without much extra time on CHB alone.

-

•

Current CHB underscreening: At-risk groups were previously underscreened owing to competing interests and awkwardness of conversations.

-

•

Provider preference for universal CHB screening: PCPs like the convenience of having 1 less thing to worry about, with the simple alert.

-

•

Patient acceptance of universal CHB screening: Patients had almost no questions about this additional routine health screening.

-

•

Ease of implementation: Expected patient and implementation barriers did not materialize.

-

•

MAs’ enhanced workflow:When rooming, MAs often brought up CHB screening, pended orders for PCPs, and then helped with result follow-up.

-

•

Ease of ordering: 1-click ordering eased implementation, including automatically adding the second ICD-10 code for Medicare patients.

Table 3.

Viewpoints of PCPs and MAs About Universal Screening From CHB Implementation, With a Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Blood Test

| Theme | Theme description | PCP quotes | MA quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low clinical burden | PCPs and MAs bundled their CHB discussions into their routine health maintenance discussions. | “It didn't take too long, I added it to what I normally do.” | “I mentioned this with universal hepatitis C screening and immunizations, when I was rooming them.” |

| “Almost no patients had additional questions.” | |||

| “I told patients that this was a new California screening rec to look for a treatable viral illness, then talked about their colonoscopy and immunizations.” | |||

| Current underscreening of at-risk groups | Under the risk-based approach, physicians would screen for CHB for well-known at-risk groups, such as IV drug users, people with multiple sexual partners, or Asians from endemic countries. Persons from Africa, from South/Central America, and with intersectional identities were overlooked. | “Prior to implementation, I did not screen patients routinely for hep B, only certain populations such as Asian—but I did not follow the at-risk definition to the T.” | “The tool has been working and has brought a lot of information to the providers. We have been vaccinating a lot of patients that we're never screened, and they've been with us for years.” |

| “It was hard to remember to do this.” | |||

| Providers preferred universal screening | Having universal CHB screening and a reminder made CHB screening a routine part of their activity and removed the burden of awkward discussions. | “[S]o much easier, as part of my normal workflow.” | N/A, as MAs did not do any CHB screening prior to this alert. |

| “It is one less thing to be afraid of missing. The alert is right there.” | |||

| Patients accepted universal screening | PCP patients generally considered CHB testing as another necessary preventative measure, with many booking their tests in advance. | “My patients accepted the screening as another part of the check-up routine. Some even called in advance to schedule the test.” “I haven't had a situation where patients are put back or put off by the screening labs.” |

“Patients are generally positive when responding to hepatitis B screening… I never got any push back about the labs.” |

| Ease of CHB alert implementation | Expected implementation barriers did not materialize, including concerns regarding stigma around CHB diagnosis. Providers reported that their staff were able to adapt well to the CHB alert implementation without much additional training. | “My staff was able to adapt well to the change—it did not require much training.” | “The training was straightforward and took about less than 5 minutes per person. It just added a quick extra click.” |

| MAs enhanced workflow | PCPs shared that their MAs had alert access and were generally in charge of pending orders and that some MAs would follow up with test results for patients | “Our workflow is that our MAs will mention and pend any HM due with every visit. That is the key because it starts the thought process and conversation.” “My staff was able to adapt well to the change - it did not require much training.” |

“When I take my patient in… I'll look at their HM due. I'll let them know what they're due for and then I'll go ahead and pend all the orders.” |

| Ease of ordering | The 1-click ordering feature allows PCPs to order screening at the click of a button and wanted it for other health maintenance functions. A second ICD-10 code of other Risky Lifestyles was necessary for Medicare patients. | “I would love to see the one click added to other HM Duesa [alerts]. It is easy to use and saves time.” “I told [my Medicare] patients [that] I needed to add this code to get the test covered.” |

“The one-click ordering feature is easy. I just hover it when I click it, it will send the order right away.” |

HM Due is the umbrella term for health maintenance items for which the patient is due, within the health system.

CHB, chronic hepatitis B; IV, intravenous; MA, medical assistant; N/A, not available; PCP, primary care provider.

DISCUSSION

This study found that a 1-time, universal hepatitis B screening alert in primary care clinics increased CHB screening rates, did not increase clinical burden, was easily implemented, and was acceptable to PCPs and their patients. This paper is the first study to provide the first evaluation of universal CHB screening in primary care clinics and serves as a starting point to implementing a universal CHB screening program. However, these findings should be taken considering some limitations. Foremost, the authors acknowledge potential concerns that universal screening could be burdensome on the healthcare system. Challenges such as increased testing costs, diagnostic follow-up, and provider workload are undeniably important considerations. However, it is crucial to emphasize that the benefits of universal CHB screening can outweigh these initial challenges. Early detection and intervention will prevent the progression of hepatitis B to advanced stages, which in turn can significantly reduce the long-term burden on the healthcare system. Studies that have modeled the cost-effectiveness of universal CHB have shown that universal screening is cost saving compared with current CHB screening guidelines.3 Furthermore, from an equity standpoint, universal CHB screening will eliminate health disparities, especially for marginalized communities by eliminating the disclosure of stigmatizing risk factors. In addition, this study was conducted within a specific geographic area. It will be important for future studies to address the generalizability of these results to other states considering that healthcare contexts and policies will vary from one state to another.

Given new CDC recommendations for universal CHB screening, the authors hope that these early implementation results will encourage universal CHB screening at other medical centers. Consistent with the new CDC recommendation, the study team will expand to a 3-panel CHB test and evaluate CHB program outcomes at 12 months.10

CONCLUSIONS

Implementing new CDC-recommended universal CHB screening is feasible and acceptable in academic and community primary care clinics. As hepatitis B persists as a leading cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer, shifting to universal CHB screening can decrease mortality and morbidity from liver diseases.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the clinicians and staff at Stanford Primary Care and Population Health and Stanford Medical Practices and the Stanford medicine digital health team. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Ambulatory Quality and Population Health team staff training and creation of the One Point Lesson tool. RVC, SS, TVD contributed equally as first coauthors. Electronic medical record screenshots are included with permission from Epic Systems Corporation (2023) and the Stanford Population Health Quality Improvement Team.

Unrestricted funding was provided through the Stanford Asian Liver Center, Stanford Center for Asian Health Research and Education, and the Stanford Population Health Quality Improvement Team.

Declaration of interest: none.

CRediT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Richie V. Chu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Sai Sarnala: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Thanh Viet Doan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Armaan Jamal: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Anuradha Phadke: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Sam So: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Richard So: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Hang Pham: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Joceliza Chaudhary: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Robert Huang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Gloria Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Latha Palaniappan: Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Karina Kim: Project administration, Resources. Malathi Srinivasan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramsay ME, Rushdy AA, Harris HE. Surveillance of hepatitis B: an example of a vaccine preventable disease. Vaccine. 1998;16(suppl):S76–S80. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toy M, Hutton DW, So S. Population health and economic impacts of reaching chronic hepatitis B diagnosis and treatment targets in the U.S. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1033–1040. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0035. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Toy M, Hutton DW, Harris AM, Nelson N, Salomon JA, So S. Cost-effectiveness of 1-time universal screening for chronic hepatitis B infection in adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(2):210–217. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lingala S, Ghany MG. Hepatitis B: screening, awareness, and the need to treat. Fed Pract. 2016;33(suppl 3):19S–23S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6375415/ . Accessed August 2023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman LE, Sullivent EE, Grohskopf LA, et al. Recommendations for postexposure interventions to prevent infection with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, or human immunodeficiency virus, and tetanus in persons wounded during bombings and other mass-casualty events–United States, 2008: recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-6):1–CE4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6375415/ . Accessed August 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li D, Tang T, Patterson M, Ho M, Heathcote J, Shah H. The impact of hepatitis B knowledge and stigma on screening in Canadian Chinese persons. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(9):597–602. doi: 10.1155/2012/705094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu JN, Nguyen TT, Rivadeneira NA, Hiatt RA, Sarkar U. Exploring factors associated with hepatitis B screening in a multilingual and diverse population. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):479. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07813-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HS, Rotundo L, Yang JD, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence and awareness of hepatitis B virus infection and immunity in the United States. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24(11):1052–1066. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehn J. Asm. Evan Low, Asm. Mike A. Gipson introduce AB 789 to address disparities in California's testing and treatment for hepatitis B and C. Sacramento, CA: Stanford Medicine.https://med.stanford.edu/liver/media/news/articles2014/_jcr_content/main/panel_builder_121985963/panel_0/panel_builder_704616412/panel_1/download_1759882976/file.res/2-22%20AB%20789%20press%20release_final%20(1).pdf. Published February 21, 2021. Accessed June 2023.

- 10.Conners EE, Panagiotakopoulos L, Hofmeister MG, et al. Screening and testing for hepatitis B virus infection: CDC recommendations - United States, 2023. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72(1):1–25. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7201a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall EW, Weng MK, Harris AM, et al. Assessing the cost-utility of universal hepatitis B vaccination among adults. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(6):1041–1051. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chitnis A. Screening for hepatitis B virus and tuberculosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2022;18(5):283–285. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6375415/ . Accessed August 2023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahajan R, Moorman AC, Liu SJ, Rupp L, Klevens RM. Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS) Investigators*. Use of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, coding in identifying chronic hepatitis B virus infection in health system data: implications for national surveillance. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(3):441–445. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan M, Asch S, Vilendrer S, et al. Qualitative assessment of rapid system transformation to primary care video visits at an Academic Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7):527–535. doi: 10.7326/M20-1814. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/m20-1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]