Abstract

Neuroinflammation in the central nervous system (CNS), driven largely by resident phagocytes, has been proposed as a significant contributor to disability accumulation in multiple sclerosis (MS) but has not been addressed therapeutically. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is expressed in both B-lymphocytes and innate immune cells, including microglia, where its role is poorly understood. BTK inhibition may provide therapeutic benefit within the CNS by targeting adaptive and innate immunity-mediated disease progression in MS. Using a CNS-penetrant BTK inhibitor (BTKi), we demonstrate robust in vivo effects in mouse models of MS. We further identify a BTK-dependent transcriptional signature in vitro, using the BTKi tolebrutinib, in mouse microglia, human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived microglia, and a complex hiPSC-derived tri-culture system composed of neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, revealing modulation of neuroinflammatory pathways relevant to MS. Finally, we demonstrate that in MS tissue BTK is expressed in B-cells and microglia, with increased levels in lesions. Our data provide rationale for targeting BTK in the CNS to diminish neuroinflammation and disability accumulation.

Subject terms: Multiple sclerosis, Innate immunity, Microglia

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is expressed in immune cells and microglia, where its role remains poorly understood. Here, the authors show that BTK modulates microglial neuroinflammatory pathways relevant to multiple sclerosis (MS) and report robust effects of BTK inhibition in human in vitro models and animal models of MS.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS), in which adaptive and innate immune dysfunction drive various aspects of disease presentation and progression1. Although the frequency of acute inflammatory attacks decreases over the course of the disease1, most MS patients continue to accumulate disability2. MS has historically been considered a T cell-mediated disease, but over the last decade clinical trials using monoclonal antibodies that selectively deplete peripheral CD20-expressing B cells3,4 have highlighted the role of B cells in acute focal inflammation.

An emerging feature of MS pathology is the involvement of phagocytes including microglia, the CNS-resident macrophages that constitute the principal innate immune system of the brain and spinal cord5. Microglia and macrophages5 participate in focal demyelination and axon damage in white matter lesions6 and are found around the actively demyelinating border of chronic active lesions, which are associated with disability progression7. Treatment strategies targeting aberrant inflammatory signaling in both CNS-resident microglia and peripheral innate and adaptive immune cells may play a key role in preventing disease progression.

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase belonging to the TEC kinase family with a well-defined role in the adaptive immune response, particularly in signaling downstream of the B-cell receptor (BCR)8. Inhibiting BTK activity in B cells produced phenotypic changes consistent with blockade of the BCR, preventing activation and maturation of these cells9. Recent evidence also suggested BTK involvement in innate immune signaling through the coupling of Fc-gamma receptor (FcγR), Fc-epsilon receptor, and other related stereotypical molecular pattern sensors, including Toll-like receptors (TLR)10. In mice, an inflammatory response that was dependent on microglial FcR signaling was blocked by inhibition of BTK activity11. In the CNS, microglia are the predominant source of cellular BTK expression, with comparatively lower expression levels seen in neurons and astrocytes12.

BTK inhibitors (BTKi) are attractive candidates for disease-modifying therapies in MS due to their potential to target both adaptive and innate immunopathology13. Specifically, the potential to target microglia as well as pathogenic B cells that expand within lymphocytic meningeal aggregates14 would represent a significant advancement from existing therapies that only target the peripheral immune system15. Furthermore, as small molecules, BTKi may effectively cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which serves as an impediment to modulating the CNS immune response15.

In this study we employed both in vivo and in vitro models to better understand how BTK mediates neuroinflammation in innate immune cells. We established a BTK-specific transcriptomic signature across multiple mouse and human cellular models in vitro, including a newly described human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived tri-culture consisting of human microglia, astrocytes, and neurons. Finally, we demonstrate that an inhibitor of BTK is efficacious in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of MS, and that this kinase is expressed not only in B-cells, but also phagocytes in MS tissues proximal to demyelinating lesions in MS patient samples. These data indicate that BTK-dependent pathways could drive both adaptive and innate immune-driven disease progression and support the validity of developing CNS-penetrant BTKi therapeutics for relapsing and progressive forms of MS.

Results

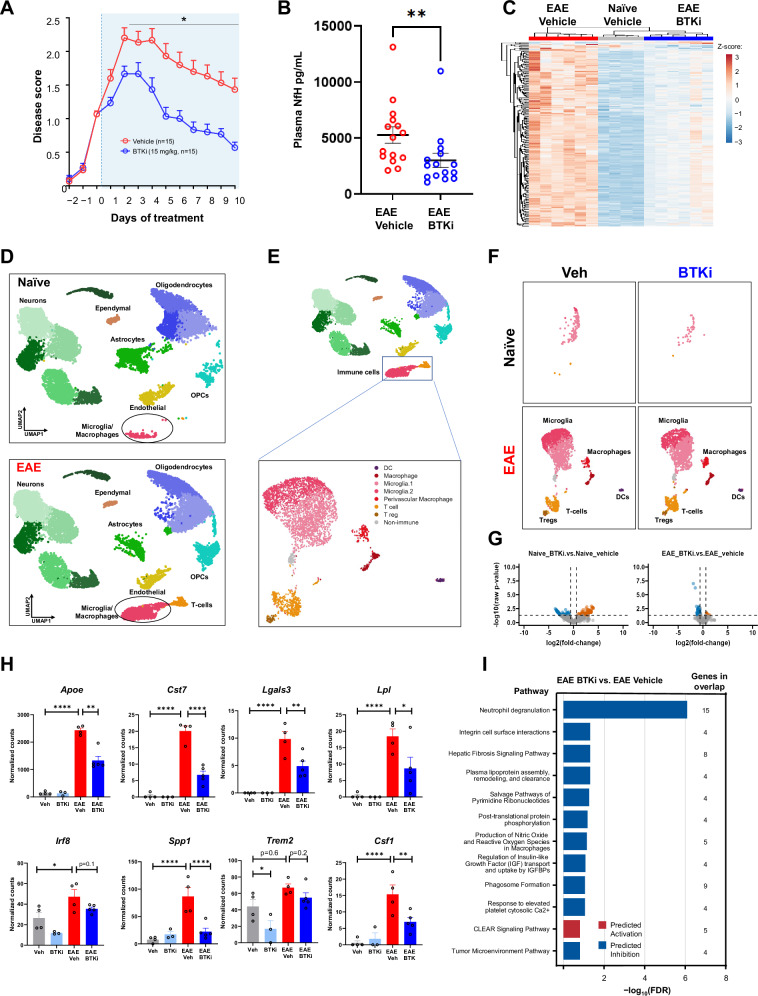

Neuroinflammation was attenuated by BTKi in mouse models of MS

We used the MOG35–55 peptide induction EAE model of MS to determine whether BTK inhibition could attenuate disease manifestations. Following EAE induction, animals were therapeutically administered either the small molecule CNS-penetrant BTKi PRN2675 or vehicle. Disease progression was assessed over the following 10 days. Compared with vehicle-treated animals, clinical disease scores (Fig. 1A) and plasma neurofilament heavy chain (NfH) levels (Fig. 1B) were significantly reduced with BTK inhibition. Treatment with either of the non-CNS-penetrant small molecule BTKi acalabrutinib or ibrutinib (Fig. S1) partially reduced clinical disease scores. However, B cell depletion via anti-CD20 antibody administration had no effect on clinical progression (Fig. S2), These data suggest that the BTK mediated beneficial effect in this model is via both peripheral and CNS innate immune targeting. To better understand the role of BTKi in EAE, we performed bulk RNA-Seq on spinal cord tissue isolated from naïve and EAE-induced mice in the presence or absence of PRN2675, after 10 days of dosing. There was a robust EAE-dependent transcriptional response in the mouse spinal cord (Fig. 1C and Fig. S3A). We found that BTK inhibition induced a broad anti-inflammatory signature in the mouse spinal cord following EAE induction (Fig. 1C). Specifically, 253 genes were identified following PRN2675 treatment (Fig. 1C). These genes are known to be associated with various immune pathways, including pathogen induced cytokine storm, neuroinflammation and FcγR-mediated signaling pathways (Fig. S3B). We also observed increased Btk gene expression after EAE induction, which was associated with increases in the microglia/macrophage-associated transcript Aif1 (Fig. S3C). While these data identify an important deleterious role for BTK-dependent signaling in EAE, they do not examine the cellular origin of this signaling. To address this, we performed single-nuclei RNA sequencing in the spinal cords of these mice. Using cluster gene expression signatures and several known markers for each cell type, we identified major cell types of the CNS, including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, microglia/macrophages, T-cells, ependymal cells, and endothelial cells. Using this approach, we were able to not only see robust transcriptional alterations induced in the EAE condition, as assessed by pseudo-bulk analysis (Fig. S3D), but we also observed changes in specific cellular populations and in particular the expansion and appearance of immune cells including microglia (Fig. 1D, E, Fig. S3E). To further explore the nature of the cell state shifts in the immune cells, we performed sub-clustering analysis. This resulted in 6 different cell type clusters in which two microglial clusters accounted for the largest proportion of the cells (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, the number of microglia was increased following EAE and a new cluster of microglia appeared (Fig. 1F). These microglial clusters accounted for the vast majority of Btk expression (Fig. S3F). BTK inhibition did not alter the presence of the EAE-induced immune clusters; however, inhibition of BTK both in the naïve and EAE conditions induced a robust transcriptional response (247 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and 110 DEGs, respectively) (Fig. 1G). We examined several disease-associated microglial genes including Cst7, Lgals3, Lpl, Irf8. Spp1, Trem2, Apoe, and Csf116–18, and found that PRN2675 could reverse the EAE-induced increase in expression of these genes specifically in microglia (Fig. 1H). Pathway analysis of the microglial genes that were regulated by BTK in EAE was performed and showed a general alteration of immune phenotypes associated with integrin signaling, fibrosis, and phagosome formation among others. Genes within the top pathway include those associated with neuroinflammation/neurodegeneration (Lgals3, Ftl, Ctsd, Ctsz) and endosomal/lysosomal function (CD68, Ctsd, Ctsz)19–22. (Fig. 1I). Pathway analysis of microglial genes regulated by BTK in naive mice yielded similar results (Fig. S4). Although these data suggest that effects of BTK are associated with the innate immune system (i.e., macrophages and microglia), a role of adaptive immunity could not be excluded as we observed increased expression of the T-cell marker gene Il2ra in the EAE spinal cord (Fig. S3C), as well as an increase of T-cells in the single cell analysis (Fig. 1F), consistent with the known role of T-cells in this MOG35–55 peptide induction model23.

Fig. 1. BTK inhibition with PRN2675 in the C57BL/6 EAE mouse model of MS.

A Disease scores over time. Therapeutic treatment started once disease scores reached 1.0–1.5. B Plasma NfH concentrations at Day 10 (n = 15 mice. Shown p-value is 0.0032, calculated with a two-tailed Mann Whitney test). C Heatmap of PRN2675-dependent transcriptional signature genes. Heatmap displays DESeq2 normalized counts scaled using a Z-score. Spinal cord tissue was collected after 10 days of vehicle or PRN2675 treatment and bulk RNA-seq was performed. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2. The PRN2675-dependent transcriptional signature consists of 253 genes with an absolute (fold-change) ≥1.5 and FDR ≤ 0.05 when comparing EAE + PRN2675 to EAE + vehicle. D UMAP representation of single-nuclei RNA sequencing analysis of 52,655 cells from EAE mouse spinal cords. Clusters were identified using Seurat and several known markers for each cell type. Spinal cord tissue was collected after 8 days of vehicle or PRN2675 treatment and single-nuclei RNA-sequencing was performed. E UMAP of immune cell-type subclusters identified by sub-clustering analysis of microglia/macrophage and T-cell clusters shown in (D). F UMAP of immune cell-type clusters, as in (E), identified in naive and EAE animals, with or without PRN2675. G Pseudo-bulk analysis of microglia subclusters identified in (E) and volcano plots of differential gene expression between PRN2675-treated and untreated mouse spinal cord. Plots are shown for both naive and EAE mice. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and raw p-value ≤ 0.05). H DESeq2 normalized counts of disease-associated microglial genes, identified in (G). Shown p-values are unadjusted and were calculated using Wald significance test implemented in DESeq2 (n = 3–5 mice). P-values are available in the Source Data file. I Pathway analysis using IPA: EAE + PRN2675 vs EAE + vehicle. The 12 pathways that demonstrated the largest change (−log10(FDR)) and showed direction (i.e., had a z-score available) are presented. All 12 pathways shown were downregulated with EAE + PRN2675 vs EAE+ vehicle. The pathway analysis gene list is the PRN2675-dependent transcriptional signature identified in the right plot of panel G. P-values are indicated by * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01, *** ≤ 0.001, and **** ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

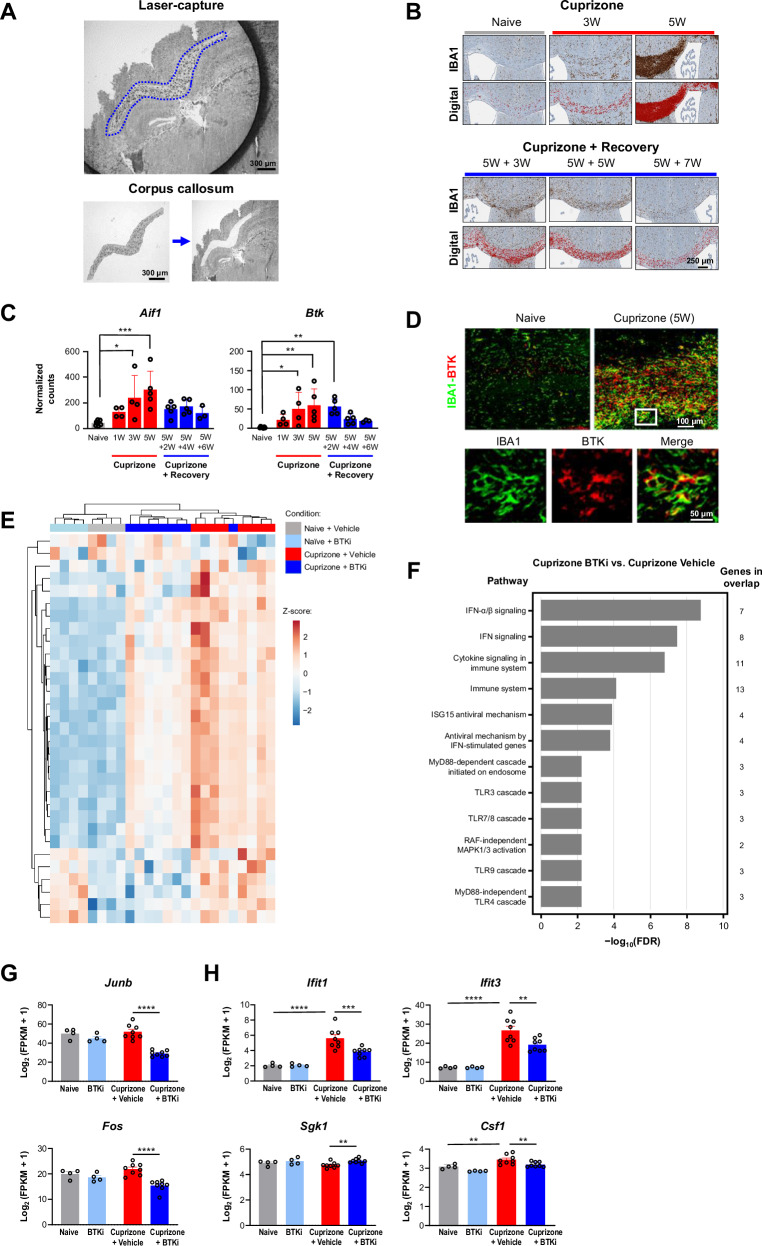

We next investigated whether BTKi directly modulated innate immune signaling in the cuprizone model of demyelination. In contrast to EAE, for which adaptive immunity is central to model induction, the cuprizone model is not dependent upon infiltrating peripheral lymphocytes24. We performed immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of brain tissue alongside RNA-Seq on microdissected corpus callosum over five weeks of cuprizone treatment and six weeks of recovery (Fig. 2A). During cuprizone treatment in this model, there was a progressive increase in the number of cells in the corpus callosum that stained positively for ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1), a marker for microglia and macrophages. These levels recovered to baseline following cessation of the cuprizone diet and resumption of normal mouse chow (Fig. 2B)25. RNA-Seq data showed increased expression levels of Aif1, which encodes IBA1, during the course of this model. Btk expression mirrored the pattern seen for Aif1 (Fig. 2C). Of note, there was minimal involvement of peripheral B or T cells in this model, as assessed by RNA-Seq analysis of cell-specific markers (Fig. S5). To confirm these findings and to identify the cellular source of the BTK expression, we performed IHC analysis and observed that BTK colocalized with IBA1 in the brains from cuprizone-treated animals (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. BTKi in a cuprizone mouse model of demyelination.

A Isolation of corpus callosum from mouse brain using laser-capture microdissection. B Immunostaining for microglial/macrophage marker IBA1 was used to generate a digital signal in HALO. This experiment was reproduced twice with similar results. C DESeq2 normalized counts for the Btk gene and the microglia/macrophage marker gene Aif1 during cuprizone treatment and subsequent recovery (n = 3–7 mice). P-values for Aif1: naive vs. 3W and 5W are 0.012 and 0.0003, respectively. P-values for Btk: naive vs. 3W, 5W, and 5W + 2W are 0.0252, 0.0029, and 0.0053, respectively. D Fluorescent immunostaining for BTK and IBA1. Mouse BTK histology was the result of many experiments to determine optimal antibodies and concentrations to selectively stain for BTK+ cells. E Heatmap of PRN2675-reversed transcriptional signature genes. Heatmap displays log2(FPKM + 1) data scaled using a Z-score. Differential expression analysis was performed in Array Studio using a general linear model. The PRN2675-reversed transcriptional signature consists of 31 differentially expressed genes (absolute(fold-change) ≥ 1.2 and p-value ≤ 0.05) in Cuprizone + Vehicle vs Naive + Vehicle that were reversed in Cuprizone + PRN2675 vs Cuprizone + Vehicle. F Pathway analysis of genes identified in panel E, performed using EnrichR tool based on 2022 Reactome Database. The pathway analysis gene list is the PRN2675-dependent transcriptional signature identified in panel (E). G Expression of the Junb and Fos transcription factor genes quantified as log2(FPKM + 1). Shown p-values were calculated using Array Studio (n = 4–8 mice). P-values are available in the Source Data file. H Expression of the Ifit1,Ifit3, Sgk1, and Csf1 genes quantified as log2(FPKM + 1). Shown p-values were calculated using Array Studio (n = 4–8 mice). P-values are available in the Source Data file. P-values are indicated by * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01, *** ≤ 0.001, and **** ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, BTKi BTK inhibitor, FDR false discovery rate, FPKM fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads, IBA1 ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1, IFN interferon, MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase, RAF rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinase, W week mitogen-activated protein kinase, RAF rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinase, W week. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To investigate whether BTKi could alter innate immune signaling in the brain, we treated mice that had received cuprizone for five weeks with either vehicle or PRN2675 for 5 days and then performed transcriptomic analysis. Immunostaining indicated that both microglial/macrophage markers and BTK immunoreactivity peaked after five weeks of cuprizone treatment (Fig. 2D). Consistent with our previous study, cuprizone induced a change in the transcriptome in the CNS; acute treatment with PRN2675 altered this cuprizone-induced transcriptional change (Fig. 2E). Pathways that were altered following PRN2675 treatment were related to inflammatory signaling, particularly interferon signaling (Fig. 2F). PRN2675 treatment reduced transcription of the Junb and Fos transcription factor genes (Fig. 2G) and attenuated cuprizone-induced increases in Ifit1, Ifit3, and Csf1 expression (Fig. 2H). These data suggest that a CNS-penetrant BTKi can alter the transcriptional response in the context of CNS injury. Several genes modulated by PRN2675 in the cuprizone mouse spinal cord were also modulated by PRN2675 in the EAE mouse microglia subpopulation (Fig. S6). While these data suggest an alteration in the immune profile in the brain, during demyelination BTK inhibition did not alter the course of remyelination following cuprizone treatment at an early time-point (Fig. S7). These data combined with those from the EAE model suggest that BTKi can alter inflammatory signaling not only in B cells, but also in innate immune cells within the CNS.

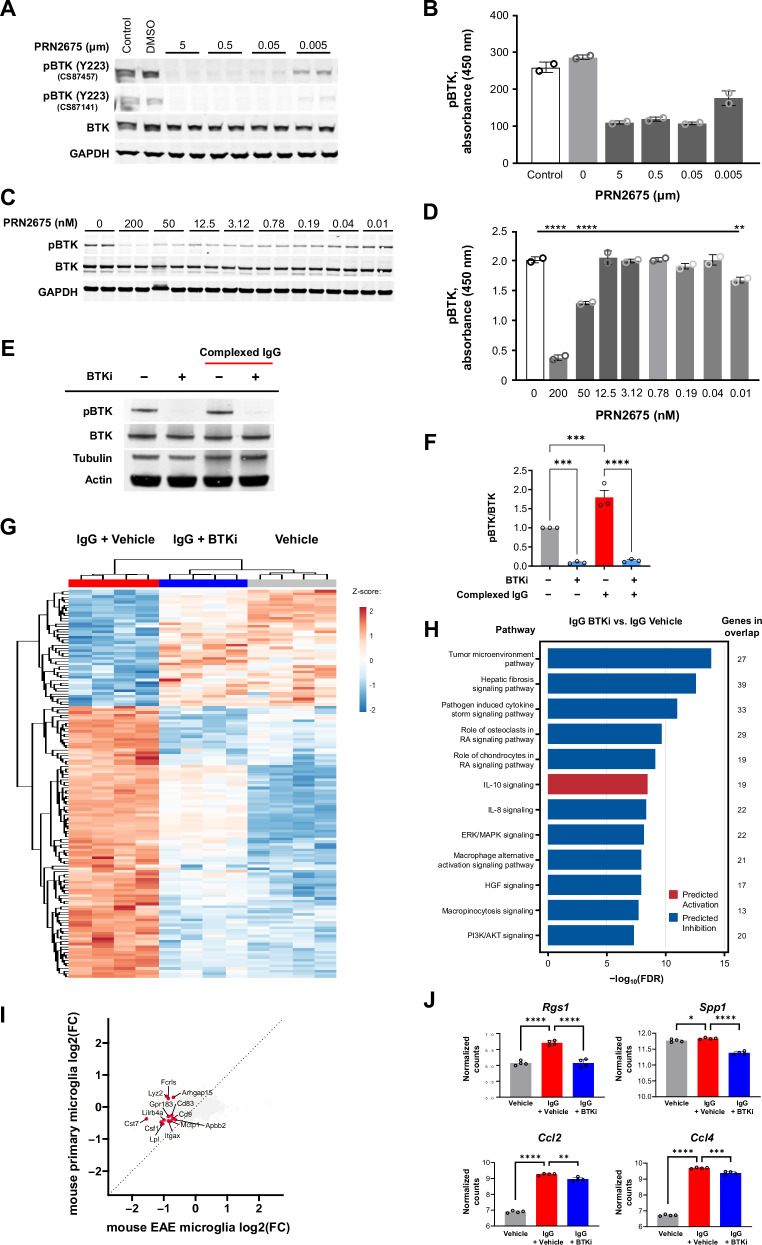

BTK-dependent signaling mediates an inflammatory response in mouse microglia

To assess BTK-mediated signaling specifically in microglia, we performed experiments using a mouse microglial cell line and primary mouse microglia, both of which show detectable levels of phosphorylated BTK under basal in vitro conditions (Fig. 3A–D). Treatment with PRN2675 rapidly reduced levels of phosphorylated BTK (Tyr223), as assessed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A–C) and ELISA (Fig. 3B–D). We also stimulated primary mouse microglia with complexed immunoglobulin G (IgG), which is known to engage FcR that couples with BTK for downstream signaling, in the presence or absence of an irreversible BTKi, tolebrutinib. This stimulus increased BTK phosphorylation, which was blocked by tolebrutinib (Fig. 3E–F).

Fig. 3. Activation of BTK and identification of a BTK-dependent transcriptional signature in mouse microglia.

Effect of the irreversible BTKi PRN2675 on BTK autophosphorylation in the BV-2 mouse microglial cell line, assessed by Western blot (A) and ELISA (B) (n = 2 technical replicates for (B)). Effect of PRN2675 on BTK phosphorylation in primary mouse microglia, assessed by Western blot (C) and ELISA (D). P-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak test. P values shown in (D) for PRN2675 0 vs. 200, 50, and 0.01 nM are <0.0001, <0.0001, and 0.0036, respectively (n = 2 technical replicates for (D)). E BTK enzyme activity in primary mouse microglia, with or without complexed mouse IgG stimulation or tolebrutinib, assessed by Western blot. F Effect of the irreversible BTKi tolebrutinib on the pBTK-to-BTK ratio in primary mouse microglia, with or without complexed mouse IgG stimulation, quantified by Western blot, as exampled in (E). Shown p-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak test. P-values for Control vs. BTKi, Control vs. IgG, and IgG vs. IgG+BTKi are 0.0004, 0.001, and <0.0001, respectively (n = 3 separate experiments). G Heatmap of tolebrutinib-reversed transcriptional signature genes in primary mouse microglia. Heatmap displays log2(FPKM+1) data scaled using a Z-score. Differential expression analysis was performed in Array Studio using a general linear model. The tolebrutinib-reversed transcriptional signature consists of 144 differentially expressed genes (absolute (fold-change) ≥1.2 and p value ≤ 0.05) in IgG + tolebrutinib vs IgG + Vehicle that was reversed in IgG + Vehicle vs Vehicle. H Pathway analysis using IPA for IgG + tolebrutinib vs. IgG. H The 12 pathways that were most significantly impacted (−log10(FDR)) and showed direction (i.e., negative z-score [predicted inhibition] or positive z-score [predicted activation]) are presented. The pathway analysis gene list is the tolebrutinib-dependent transcriptional signature identified in (G). I Four-way plot of EAE pseudo-bulk microglia differential expression results for EAE+PRN2675 vs EAE + vehicle (Fig. 1G, right) and primary mouse microglia differential expression results for IgG + tolebrutinib vs IgG (Fig. 3G). Labeled genes were commonly significantly differentially expressed genes between the two analyses (for EAE, absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and raw p value ≤ 0.05; for mouse microglia, absolute(fold-change) ≥ 1.2 and p value ≤ 0.05). J Expression of immune-associated gene targets for which expression was partially altered with tolebrutinib, quantified as log2(FPKM+1). Shown p-values were calculated using Array Studio (n = 4 technical replicates). P-values are available in the Source Data file. P-values are indicated by * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01, *** ≤ 0.001, and **** ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. AKT protein kinase B, BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, BTKi BTK inhibitor, DMSO dimethyl sulfoxide, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ERK extracellular signal-regulated kinase, GAPDH glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, IgG immunoglobulin G, IL interleukin, IPA ingenuity pathway analysis, MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase, pBTK phosphorylated BTK, PI3K phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, RA rheumatoid arthritis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We used RNA sequencing to investigate whether there was a BTK-dependent transcriptional response in microglia. When these cells were stimulated with complexed IgG in the presence or absence of tolebrutinib, a distinct set of genes were differentially expressed, including a subset that was downregulated in the presence of tolebrutinib (Fig. 3G). The BTK-dependent transcriptional signature was enriched for genes associated with signaling pathways including TLR signaling and neuroinflammation (Fig. 3H). There were also genes modulated both by tolebrutinib in IgG-stimulated primary mouse microglia and by PRN2675 in the EAE mouse microglia subpopulation (Fig. 3I), suggesting some of the BTK-dependent signaling in vivo is recapitulated in the in vitro microglial system. The BTK-dependent transcriptional signature identified in mouse microglia included Rgs1, which encodes the regulator of G-protein signaling 1 protein (a GTPase-activating protein that regulates heterotrimeric G-protein activity) and is a known susceptibility loci for MS26. The increased Rgs1 expression observed upon complexed IgG stimulation was fully blocked by tolebrutinib (Fig. 3J). We confirmed these findings in a separate set of experiments using primary microglia from mice (Fig. S8A), and additionally showed in vivo that Rgs1 expression levels decreased in naïve mice orally administered a BTKi (Fig. S8B). These data suggest that this gene could be used as a direct biomarker of BTK activity. Expression of other immune-associated genes was partially altered following tolebrutinib treatment, including Spp1, which encodes the extracellular matrix protein osteopontin and27, as well as Ccl2 and Ccl4, which encode monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β28 (Fig. 3J). Taken together, our data showed that BTK was activated in microglia following immune stimulation and that BTKi partially blocked signaling in these cells, including pathways implicated in neuroinflammation and autoinflammatory disease.

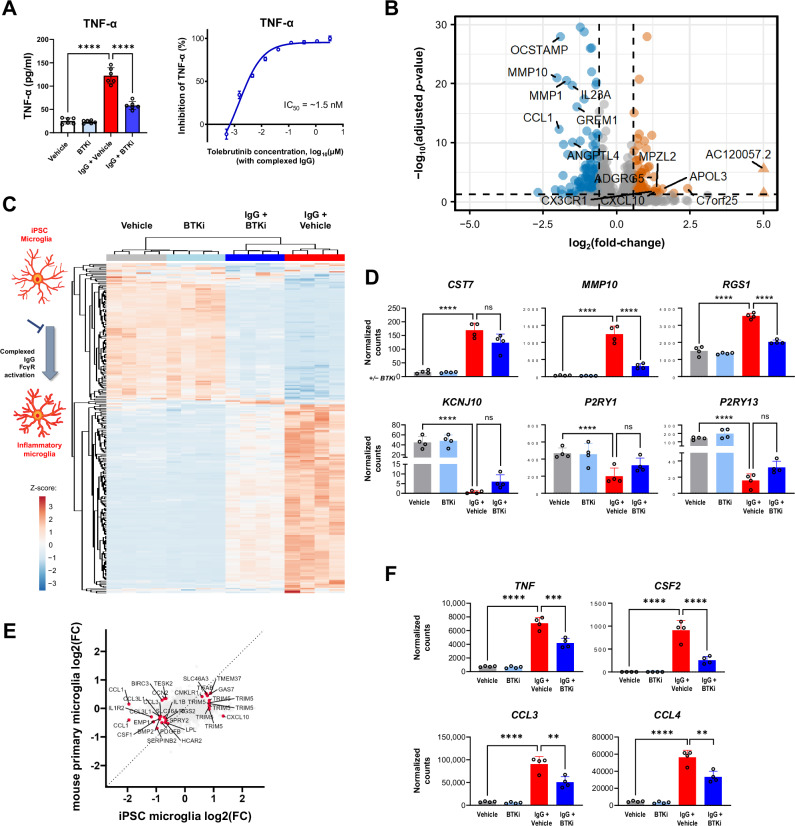

BTK-dependent signaling mediates an inflammatory response in hiPSC-derived microglia

To determine whether BTKi translated to effects in human cells, we used hiPSC-derived microglia, and stimulated them through the FcγR in the presence or absence of the BTKi tolebrutinib. Stimulation of these cells led to increased levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in the cell supernatant, which was fully reversed by tolebrutinib (Fig. 4A, left). Using this stimulation paradigm we estimated the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ~1.5 nM for tolebrutinib (Fig. 4A, right). To better understand the functional consequences of tolebrutinib BTKi in human microglia, we used RNA-Seq to show that this stimulation induced a marked microglial response (Fig. 4B). Consistent with our data using primary mouse microglia, we identified a clear BTK-dependent transcriptional signature (Fig. 4C). This included CST7, MMP10, and RGS1, which were induced in response to FcγR stimulation and KCN1J10, P2RY1, and P2RY13, which were reduced in response to FcγR stimulation (Fig. 4D). We identified an overlap between the BTK-dependent response in mouse and human-derived cells (Fig. 4E), but revealed many differences including the observation of DEGs encoding matrix metalloproteinases and osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein in human microglia but not mouse microglia. These data indicate that BTK activity can directly regulate the transcriptional response in both mouse and human microglia. Furthermore, we specifically examined the inflammatory profile of human iPSC-derived microglia and showed that tolebrutinib markedly attenuated the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines that were upregulated in response to FcγR stimulation (Fig. 4F and Fig. S9). To mimic a therapeutic setting, we also treated hiPSC-derived microglia with tolebrutinib 24 h after FcγR stimulation and quantified proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine secretion (Fig. S10). Many of the analytes tested were induced in response to FcγR stimulation and blocked by tolebrutinib including IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and MIP-1β. Interestingly, this inhibition was at least in part due to attenuation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), as tolebrutinib significantly reduced NF-κB activation downstream of FcγR signaling in a monocyte cell line (Fig. S11).

Fig. 4. Identification of a BTK-dependent transcriptional signature in human iPSC-derived microglia.

A Effect of tolebrutinib on TNF-α secretion in human iPSC-derived microglia, 24 h after complexed IgG stimulation (10 μg/mL Fc OxyBURST™; Invitrogen, F2902). Shown p-values were <0.0001 and calculated using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak test (left panel n = 6 technical replicates, right panel n = 3–6 technical replicates). B Volcano plot of differential expression between tolebrutinib-treated and untreated hiPSC-derived microglia, 6 h after complexed IgG stimulation. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2. 250 genes were observed to be differentially expressed in the IgG + tolebrutinib condition (absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and FDR ≤ 0.05). The 14 most strongly up- and down-regulated genes (as ranked by log2(fold-change)) are labeled (Wald significance test implemented in DESeq2). C Heatmap of the 250 tolebrutinib-specific transcriptomic signature identified in (B). Heatmap displays DESeq2 normalized counts scaled using a Z-score. D Effect of tolebrutinib 100 nM on expression levels of the CST7, MMP10, and RGS1 genes, which were induced by complexed IgG, and the KCN1J10, P2RY1, and P2RY13 genes, which were inhibited in response to complexed IgG. DESeq2 normalized counts are shown, with FDR-corrected p-values generated using DESeq2 (Wald significance test implemented in DESeq2, n = 4 technical replicates). P-values are available in the Source Data file. E Four-way plot of hiPSC-derived microglia differential expression results for IgG + tolebrutinib vs IgG (Fig. 4B) and primary mouse microglia differential expression results for IgG + tolebrutinib vs IgG (Fig. 3G). Labeled genes were significantly differentially expressed genes in common between the two analyses (for hiPSC-derived microglia, absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and FDR ≤ 0.05; for mouse microglia, absolute(fold-change) ≥1.2 and p value ≤ 0.05) (Wald significance test implemented in DESeq2). F DESeq2 normalized counts of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in hiPSC-derived microglia. Shown p-values are FDR-corrected and were calculated using DESeq2 (Wald significance test implemented in DESeq2, n = 4 technical replicates). P-values are available in the Source Data file. P-values are indicated by * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01, *** ≤ 0.001, and **** ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, IC50 half-maximal inhibitory concentration, hiPSC human induced pluripotent stem cell, IgG immunoglobulin G, mus. mouse, ns non-significant, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

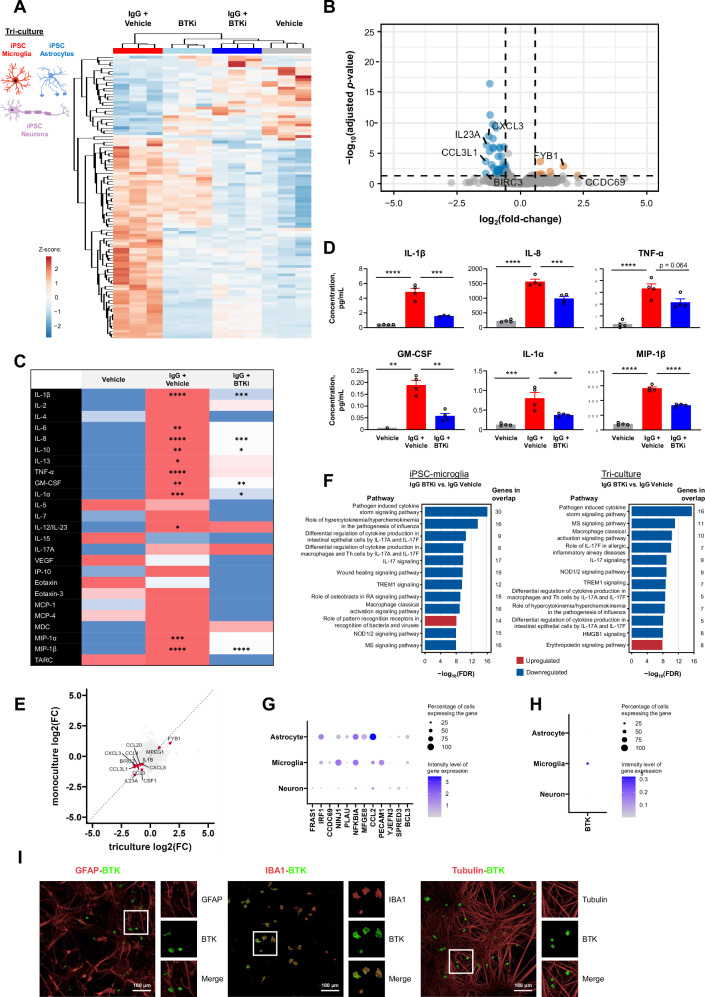

To expand on our data supporting a role for BTK in microglial regulation, we conducted further experiments using a human iPSC-derived tri-culture that included microglia, neurons, and astrocytes29,30. RNA-Seq on the tri-culture following FcγR stimulation in the presence or absence of tolebrutinib revealed a clear BTK-dependent signature in this complex human-derived system (Fig. 5A, B). We also quantified BTK-dependent changes in protein levels using a multiplexed chemokine/cytokine panel (Fig. 5C). Several of the analytes tested were induced in response to FcγR stimulation and blocked by tolebrutinib including IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-1α, and MIP-1β (Fig. 5D). There was overlap between the microglial monoculture and tri-culture sequencing data sets for both the DEGs (Fig. 5E) and BTK-dependent pathways (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, changes in chemokine/cytokine levels after FcγR stimulation were observed in tri-cultures containing microglia and not in co-cultures of solely astrocytes and neurons, with the exception of IL-7 and VEGF-A (Fig. S12). These data suggest the majority of the BTK-dependent effect is driven through microglia. Interestingly, several genes were uniquely regulated in the tri-culture. These findings suggest that BTK could regulate microglial genes only in the mixed culture condition, or that BTK in microglia could have a non-cell autonomous effect on astrocytes and neurons. To investigate these two options, we used a single-cell atlas previously derived from this tri-culture system29 and examined the cellular enrichment of the genes that were differentially regulated in the tri-culture. Many genes that were differentially regulated by BTK in the tri-culture system were enriched in non-microglial cells (Fig. 5G), including FRAS1 in neurons and PLAU and MFGE8 in astrocytes. Since BTK is almost exclusively expressed in microglia in the tri-culture (Fig. 5H, I), we hypothesize that BTKi influences neuronal and astroglial signaling indirectly via microglia, consistent with the highly integrative nature of these cell types in the CNS, including in the context of neuroinflammation.

Fig. 5. Identification of a BTK-dependent transcriptional signature in a human iPSC-derived tri-culture of microglia, astrocytes, and neurons.

A, B Tolebrutinib-specific transcriptomic signature in human tri-culture, 6 h after complexed IgG stimulation (10 μg/mL Fc OxyBURST™; Invitrogen, F2902). Heatmap of DESeq2 normalized counts scaled using a Z-score for the top 100 differentially expressed genes between IgG + tolebrutinib and IgG + vehicle, as ranked by p-value (A). Volcano plot of differential expression between IgG + tolebrutinib and IgG + vehicle. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2. 396 genes were observed to be differentially regulated in the IgG + tolebrutinib condition (absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and FDR ≤ 0.05) (Wald significance test implemented in DESeq2). The 14 most strongly up- and down-regulated genes (as ranked by log2(fold-change)) are labeled (B). C Effect of tolebrutinib on cytokine and chemokine secretion in human tri-culture, 24 h after IgG stimulation, as assessed using multiplex panels. Comparisons are for IgG + vehicle vs. vehicle, and for IgG + tolebrutinib vs. IgG + vehicle. Shown p-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak test. D Cytokine and chemokine secretion: analytes that were induced by IgG and blocked by tolebrutinib, significance indicated in (C) (n = 1–4 technical replicates). E Four-way plot of triculture differential expression results for IgG + tolebrutinib vs IgG (Fig. 5B) and hiPSC-derived microglia monoculture differential expression results for IgG + tolebrutinib vs IgG (Fig. 4B). Labeled genes were commonly significantly differentially expressed genes between the two analyses (for triculture, absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and FDR ≤ 0.05; for monoculture, absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and FDR ≤ 0.05). F IPA pathway analysis for the IgG + olebrutinib vs IgG comparison in human hiPSC-derived microglia, left, and human tri-culture, right. The 12 pathways that had the strongest significance levels (−log10(FDR)) and showed direction (negative z-score [predicted inhibition] or positive z-score [predicted activation]) are presented. The pathway analysis gene list for hiPSC-derived microglia is the tolebrutinib-dependent transcriptional signature identified in Fig. 4B. The gene list for tri-cultures is the tolebrutinib-dependent transcriptional signature identified in Fig. 5B. G Expression of BTK-regulated gene targets in the tri-culture. H Cellular enrichment of BTK expression in the tri-culture, with BTK transcripts identified in 30.5, 0.9, and 0.9 percent of microglia, astrocytes, and neurons, respectively, with Seurat normalized average expression levels of 0.376, 0.004, and 0.007. I Fluorescent immunostaining for markers of astrocytes (GFAP), microglia (IBA1), and neurons (beta-III tubulin) in the tri-culture. This experiment was reproduced twice with similar results. P-values are indicated by * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01, *** ≤ 0.001, and **** ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, FDR false discovery rate, GFAP glial fibrillary acidic protein, GM-CSF granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, HMGB1 high mobility group box 1, IBA1 ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, IgG immunoglobulin G, IL interleukin, IP-10 interferon gamma-induced protein 10, IPA ingenuity pathway analysis, hiPSC human induced pluripotent stem cell, MCP monocyte chemoattractant protein, MDC macrophage-derived chemokine, MIP macrophage inflammatory protein, MS multiple sclerosis, NOD nucleotide oligomerization domain, RA rheumatoid arthritis, TARC thymus and activated-regulated chemokine, Th T helper, TNF tumor necrosis factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

BTK is expressed in microglia within perilesional tissue from Progressive MS (PMS) patients

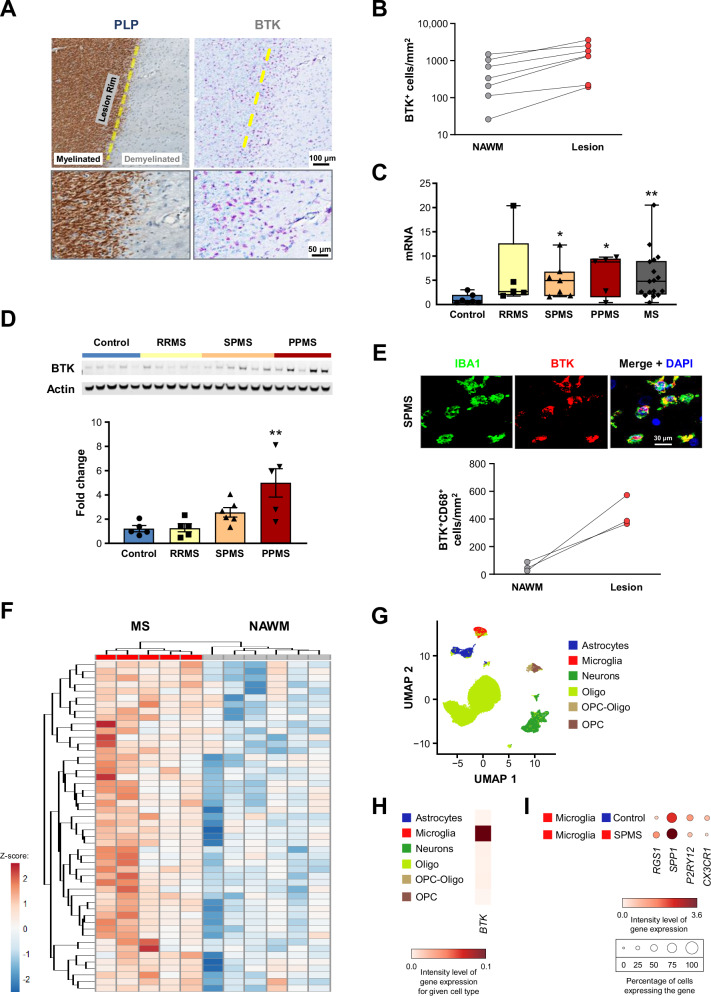

We next examined BTK mRNA and protein levels in post-mortem brain samples from MS patients and from individuals without clinical or pathological evidence of neurological disease. We identified an increase in BTK immunoreactivity in demyelinated regions compared with normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) (Fig. 6A and B; Fig. S13A, B). Bulk tissue analysis examining both mRNA (Fig. 6C), and protein levels as assessed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6D), identified marked increases of BTK levels in postmortem tissue samples obtained from MS patients compared with postmortem tissue from individuals without evidence of neurological disease. The largest changes were observed in progressive multiple sclerosis (PMS) specimens. To identify the cell types responsible for these changes, we analyzed immunostaining of white matter lesions in PMS specimens. We determined that BTK-positivity co-localized almost exclusively with IBA1-positive cells, comprising microglia and potentially monocyte-derived and CNS-intrinsic macrophages. Counts of BTK-positive cells were also increased in lesion tissue compared with NAWM (Fig. 6E). Activated microglia/macrophages co-localized with demyelinated lesions and areas of axon loss, as shown in the histology panels (Fig. 6A; Fig. S13A–C). IBA1-positive cells that line the border of chronic active white matter lesions can contain myelin debris and iron31. Interestingly, BTK-positive cells colocalized with this IBA1-positive rim around white matter lesions (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, BTK was also expressed in CD20+ B cells found in the vasculature in the MS brain (Fig. S13D). These data show that BTK levels were increased in MS specimens and specifically enriched in perilesional tissue. To address whether BTK could also functionally regulate pathological processes in MS, we used the BTK-dependent signature identified in human microglia in vitro, and compared that with the transcriptome specific to MS tissue32. Using the in vitro data as the filter for the tissue data, a set of BTK-dependent genes clearly segregated the PMS lesion signature from that in NAWM (Fig. 6F). Using the single-cell dataset from MS tissue32, we were able to confirm that BTK was also enriched in microglia in the CNS and that genes encoding targets regulated by this kinase, including RGS1, SPP1, P2RY12, and CX3CR1, had altered expression in MS patient-derived microglia (Fig. 6G–I). In summary, our data suggest that BTK signaling is active in CNS microglia/ macrophages and is associated with areas of pathological activity in progressive MS.

Fig. 6. BTK expression in microglia/macrophages within lesion tissue from PMS patients.

A Immunohistochemistry analysis for myelin PLP and BTK in post-mortem brain tissue from a PMS patient. BTK-positive cells colocalized with an IBA1-positive rim around white matter lesions. Human BTK histology was the result of many experiments to determine optimal antibodies and concentrations to selectively stain for BTK+ cells. B BTK positivity in demyelinated regions compared with NAWM (n = 7 patients). BTK mRNA expression (C) and protein levels (D; assessed by Western blot) in post-mortem bulk brain tissue samples from controls and MS patients (either grouped by individual MS subtype or as all MS combined). P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett test for (D). The p-values shown in (C) from left to right are 0.021, 0.023, and 0.008 and in (D) is 0.0019. (N = 5–18 and 5–6 patients for (C) and (D), respectively). Whiskers in (C) denote minimum and maximum values. E Co-immunostaining for BTK and microglia/macrophages, using anti-IBA antibody (for visualization) or anti-CD68 antibody (for quantification in lesion tissue compared with NAWM, where n = 3 patients). F Hierarchical clustering of PMS patient lesion samples from NAWM samples using the BTK-reversed signature identified in human iPSC-derived microglia32. Heatmap displays log2(FPKM + 1) data scaled using a Z-score. Differential expression analysis was performed in Array Studio using a general linear model. The tolebrutinib-reversed transcriptional signature consists of 144 differentially expressed genes (absolute(fold-change) ≥1.2 and p-value ≤ 0.05) in IgG + tolebrutinib vs IgG + Vehicle that were reversed in IgG + Vehicle vs Vehicle. G, H Cellular enrichment of BTK mRNA expression in brain samples from PMS patients, including t-SNE analysis (H)32. I Expression of BTK-regulated gene targets in brain samples from controls and SPMS patients. P-values are indicated by * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01, *** ≤0 .001, and **** ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, CD68 cluster of differentiation 68, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, IBA1 ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, MS multiple sclerosis, NAWM normal-appearing white matter, Oligo oligodendrocyte, OPC oligodendrocyte progenitor cell, PLP proteolipid protein, PMS progressive MS, PPMS primary PMS, RRMS relapsing-remitting MS, SPMS secondary PMS. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Our data demonstrates that BTK is active in innate immune cells including macrophages and microglia; these findings support the hypothesis that a CNS-penetrant BTKi can modulate multiple pathways driving neuroinflammation and immune-mediated inflammation in MS by targeting disease mechanisms in the CNS and in the peripheral immune system (Fig. S14). These mechanisms include inhibition of BCR-mediated B-cell activation and blockade of FcγR-induced cytokine release from FcγR-expressing cells on both sides of the BBB.

A neuroinflammatory MS phenotype is thought to be maintained through complex interactions between microglia, astrocytes, and B cells. Plasma cells derived from B cells are a source of cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal immunoglobulin bands that are pathognomonic for MS33,34. In a recent study, FcR activation triggered by injection of anti-MOG monoclonal antibodies in wild-type mice induced microglial proliferation, which was confirmed to depend on both FcγR engagement and BTK signaling11. Additionally, MRI-informed single-nucleus RNA-Seq profiling showed that FcγRs and complement C1 complex genes were upregulated in microglia circumscribing chronic active lesions35. This signaling node in innate immune cells may have particular relevance for MS, given the persistence of antibodies in the CNS in the form of oligoclonal bands34 and in some cases evidence of anti-myelin IgG autoantibodies36. The presence of myelin-specific antibodies in the CNS may result in persistent activation of microglia driving them to a more inflammatory state37,38.

In EAE, the BTKi attenuated disease pathology and was associated with reduced levels of plasma NfH, which is an established marker of acute axonal injury in this model39. In addition to its well-described role regulating FcR signaling, the BTK-dependent transcriptional signature identified following EAE induction included several immune pathways including neuroinflammation, FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes, phagosome formation, and BCR signaling. Importantly, expression of genes encoding complement signaling components (C1qa, C1qb, and C1qc) was also reduced by BTKi treatment in our EAE and these genes are upregulated in microglial cells surrounding paramagnetic lesions35. The concept of targeting neuroinflammation via FcγR signaling was previously proposed based on the findings that FcγR signaling was upregulated in MS lesions40 and that FcγR knockout mice were less susceptible to EAE41. Our data indicated that BTKi was able to attenuate EAE disease activity and modulate microglial transcriptional phenotypes, and suggested that BTK-dependent signaling is important in pathogenic neuroinflammatory processes that mediate CNS injury in human diseases like MS. This hypothesis is also supported by the observation that CSF1R inhibition principally targeting microglial function in the CNS is efficacious when administered therapeutically in the EAE model42. Because of the somewhat pleiotropic expression of BTK in both B-cells, macrophages, and microglia the cellular target of PRN2675 in this model could be multi-faceted. In particular, B cells, macrophages, and microglia all express BTK and can contribute to EAE disease pathology. However, while targeting B cells by BTKi is therapeutically relevant in MS (as is B cell depletion using anti-CD20 agents), we found that B cell depletion had no effect on disease progression in this EAE model and further note that this approach may not be sufficient to attenuate clinical disease progression2.

As it stands, distinguishing the effects of BTKi on innate versus adaptive immunity in the EAE model remains challenging. It was for this reason that we chose to study the effects of BTKi in the cuprizone model, as in contrast to EAE, for which adaptive immunity is central to model induction, the cuprizone model is not dependent upon infiltrating peripheral lymphocytes. This can also be seen in the inflammatory signature, which is quite different from EAE. Nonetheless, we identified inflammatory genes and pathways significantly modulated in the cuprizone model. Data from both the EAE and cuprizone models strongly support the concept that BTK is a potent regulator of neuroinflammation in vivo and that a CNS-penetrant BTKi could significantly reduce this neuroinflammation.

Accumulating evidence suggests that microglial FcγR plays a critical role in the inflammatory cascade in neuroinflammatory disorders43. Microglia stain strongly for FcγR in active MS lesions43, and preclinical studies have demonstrated the importance of the microglial FcγR pathway in antibody-mediated demyelination37. Furthermore, in vivo FcγR signaling was tightly coupled to BTK in mice11. We identified BTK-regulated genes and FcR activation pathways that have been associated with autoimmunity and MS. These genes included Rgs1, which was previously found to be highly enriched in brain-resident immune cells of MS patients26, and the disease-associated microglial gene Spp1, which had been similarly regulated by PRN2675 in our EAE model. In MS patients, the product of Spp1, osteopontin, is considered to play an overall detrimental role, by promoting extravasation of peripheral mononuclear cells into the CNS and prolonging microglial survival, which in turn impacts myelination27. Several genes were present in the tolebrutinib-dependent transcriptomic signatures for both mouse and human microglia, and both of these systems showed reduced expression of genes involved in inflammatory pathways. The differences observed in our study between the in vitro tolebrutinib-dependent transcriptional signature of human and mouse microglia highlight the need to study more complex human models. Importantly, in vitro human models will require consideration of culture conditions which may affect microglial function. For example, exposure of mouse microglia to CNS environmental factors has been found to modulate basal gene expression44. The potential impacts of co-culture conditions should therefore be considered. Using a newly described hiPSC-derived tri-culture29,30, we showed that the BTKi tolebrutinib not only directly modified microglial signaling but also indirectly altered transcriptomic signatures in astrocytes and neurons. The CCL3 and CCL4 genes, which encode MIP-1α and MIP-1β, respectively28,45, were downregulated after BTKi treatment in both the iPSC microglia and the tri-culture. This finding was confirmed at the protein level, with both being induced in response to FcγR stimulation and blocked by tolebrutinib. Among the other chemokines for which tolebrutinib reversed the FcγR-induced upregulation of gene expression in the tri-culture were CXCL1, which is produced by microglia and contributes to neurodegeneration in MS45, and CCL20 (MIP-3α), plasma levels of which were reported to correlate with MS disease severity46. Further work is required to characterize the cellular interactions that could underpin the tolebrutinib-dependent transcriptomic signatures in neurons and astrocytes, including the possibility of BTKi targeting other Tec kinases in these cells, and to determine the role of other MS-relevant aspects of the cellular microenvironment not represented in the hiPSC-derived tri-culture model, including myelin, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, and peripheral immune cells.

When we compared the BTK transcriptomic signature from in vitro hiPSC-derived microglia with that of human MS lesions, we found that the BTK signature hierarchically clustered secondary progressive MS (SPMS) lesion tissue from non-MS control tissue, indicating that these pathways are active in progressive MS lesions. Indeed, these results are congruent with recent studies which identified in postmortem brain tissue from MS patients an accumulation of BTK-positive myeloid cells in the rim of chronic active lesions47. These data suggest that BTK signaling is present in activated microglia in MS.

These studies highlight the importance of BTK not only in B cells, as previously described8,9, but also in macrophages and microglia. These data support the rationale for developing a CNS-penetrant BTKi to block B cell-dependent functions associated with MS and to alter the disease progression course in both relapsing-remitting and progressive MS, which are associated with deleterious neuroinflammation. Future research will further investigate potential non-cell autonomous effects of BTKi, such as promotion of remyelination as well as additional neuroinflammatory signaling pathways identified in our in vivo studies. Direct effects on inflammation in the brain (especially behind a closed BBB) would provide additional efficacy compared with anti-CD20 antibodies and other MS treatments that are believed to act predominantly in the periphery.

Methods

All animal studies were conducted in compliance with ethical regulations and full approval of Sanofi’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

BTK inhibition

In this study, BTK inhibition was achieved with either tolebrutinib or PRN2675, which differs from tolebrutinib by a single fluorine substitution for hydrogen near the reactive moiety and had a similar kinase selectivity profile. While in vitro experiments were performed using either tolebrutinib or PRN2675, PRN2675 was used for all in vivo experiments, due to ongoing tolebrutinib Phase 3 clinical trials.

PRN2675 dosing for in vivo studies was based on the observed brain penetrance and pharmacokinetics of this molecule (Fig. S15) and the efficacious dose observed in the tolebrutinib Ph2 clinical study (60 mg)48. Based on simple allometric scaling, a dose of 60 mg in human translates to ~12.3 mg/kg in mouse49. Tolebrutinib is about 40% more potent biochemically than the tool molecule, thus we chose the 15 mg/kg dose. Furthermore, based on CSF exposures for the tool molecule and clinical CSF data from a Ph1 study with tolebrutinib, we expect a similar level of free CNS exposure and BTK inhibition in mice dosed with PRN2675 at 15 mg/kg once daily. Thus, for this irreversible inhibitor we predict achievement of near complete CNS target occupancy after several days of the 15 mg/kg dose. Additional data regarding modeling CNS BTKi with tolebrutinib can be found at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.03.25.586667v1.

Mouse in vivo EAE model

EAE induction

C57BL/6 mice were immunized with an emulsion of MOG35–55 peptide (200 or 250 µg/mouse) in Complete Freund’s Adjuvant containing 0.4–0.6 mg Mycobacterium tuberculosis when aged 9–11 weeks (IACUC protocol #20-0463). The emulsion was delivered by two 100 µL subcutaneous injections to the lower back. Bordetella pertussis toxin (200–280 ng in 100–200 µL of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was administered via intraperitoneal injection, on the day of MOG35–55 peptide immunization and 2 days later. Female mice were used to allow for group housing throughout the study.

For small molecule efficacy studies, animals were randomized to receive either vehicle (PEG200 or PEG400) or orally administered PRN2675, acalabrutinib, or ibrutinib after exhibiting a minimal disease score of 1.0. For B cell depletion efficacy studies, animals were randomized to receive either control rat IgG2b isotype or intravenously administered anti-mouse CD20 antibody. Treatment groups were blinded for study duration and unblinded following final data analysis. Prism 9 (GraphPad Software) was used to calculate the area under the curve for each animal and a Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine statistical significance of between-group differences on each day.

Spinal cord processing, single nuclei isolation and sequencing, and analysis

Euthanasia was performed via exsanguination under CO2 and confirmed with cervical dislocation. Mouse spinal cords were isolated from the spinal column of PBS perfused animals using a needle filled with PBS and pressure. Once removed, spinal cords were frozen on dry ice for later nuclei isolation. Whole spinal cords were homogenized while frozen following the manufacturers protocols from the 10x Genomics Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit with RNase inhibitor (PN-1000494). Nuclei were then loaded onto Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3' v3.1 (Dual Index) (PN-1000268) and captured following manufacturers protocols. The cDNA libraries were amplified using 12 cycles initially, and then 14 cycles during the final sample index PCR. Libraries were then sequenced on a Novaseq6000 using a Novaseq S2 200 cycle reagent kit (20028315). Samples were demultiplexed and count matrixes were generated using CellRanger 7 using only exonic reads.

Samples were analyzed using Seurat 5.0.150 in R version 4.2.2. Samples were filtered to limit the inclusion of low-quality cells. Cells with fewer than 700 genes and more than 5% mitochondrial genes were removed from analysis. After filtering, the dataset was normalized and the variable features were selected using the “vst” method and using 2,000 features. The dataset was then scaled and RunPCA was performed for 50 principal components (PCs), and then the FindNeighbors function was run using 15 PCs to build the k-nearest neighbor (KNN) graph. Cluster resolution was set to “0.5”, and the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) was generated using the RunUMAP function and using 15 PCs. The SoupX algorithm (version 1.6.2)51 was then implemented to remove cell-free mRNA contamination followed by a pre-processing of the seurat object using the same parameters as above. Cluster identities were determined by calculating enriched markers using the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat. Cell types were assigned by identifying genes unique to each cluster and by cross-referencing known markers of each cell type from existing published datasets. Doublet subpopulations were identified based on co-expression of core cell marker genes. These subpopulations were removed from the dataset. Following removal the dataset was reclustered using 15 PCs and a resolution of ‘0.5’. UMAP plots and gene expression plots were generated using built-in Seurat/ggplot2 plotting functions unless otherwise described.

Immune cells were subset from the larger dataset based on cell type definitions and reanalyzed using Seurat. The variable features were selected using the “vst” method and using 2000 features. RunPCA was performed for 50 PCs, and then the FindNeighbors function was run using 15 PCs to build the KNN graph. Cluster resolution was set to ‘0.3’, and the UMAP was generated using the RunUMAP function and using 15 PCs. Cluster/cell identities were determined by calculating enriched markers using the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat and by cross-referencing known markers of each cell type from existing published datasets.

Pseudobulk counts matrices were generated by summing the RNA counts for a given gene across all cells within a cell type for each individual sample. This was repeated for each cell type for which there was sufficient cell number (i.e., >200 cells per condition) as well as for all cell types combined. To identify transcriptomic differences between conditions, differential expression analysis was performed on the pseudobulk counts matrices using DESeq2 version 1.38.352 in R version 4.2.2. DEGs were identified using absolute(fold-change) ≥1.5 and unadjusted p value ≤ 0.05 criteria.

Bulk RNA processing and analysis

RNA quality was determined using Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent, 5067-1513) with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer according to manufacturer’s instructions. Bulk RNA-Seq libraries were prepared using Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, mRNA was isolated from 1 μg total RNA using oligo(dT) magnetic beads. The captured mRNA was used as input for library preparation. Library quality control and concentration were performed and determined using the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq500 platform (parameters: Read one, 149 base pairs (bp); Read two, 149 bp; Indices, 10 bp).

Data were analyzed with Array Studio (Version 11, Omicsoft Corporation). Reads were mapped to the mouse B38 reference genome with the Ensembl R102 gene model using the Omicsoft Aligner 4 (OSA4)53. Quantification was performed at gene level to obtain count-level information using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm54. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (version 1.30.1) in RStudio (R 4.0.2). p-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg method, which controls the false discovery rate (FDR). DEGs were determined using a 1.5-fold-change (FC) threshold and FDR-corrected p-value threshold of 0.05. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed in RStudio (R 4.0.2) with the pheatmap package (version 1.0.12), using Euclidean distance and complete linkage.

Plasma NfH quantification

NfH concentration was quantified in 5 µL plasma using the Simple Plex™ Assay (with Ella platform) and a human NfH cartridge (R&D Systems), which has cross-reactivity with murine NfH (ProteinSimple, #SPCKB-PB-000519), as per manufacturer’s instructions. This assay utilizes a microchip containing NfH antibody-coated capillaries.

Mouse in vivo cuprizone model

Model induction

For RNA sequencing and immunostaining studies, the model was induced as follows: C57BL/6 mice were fed a lab diet with or without cuprizone (0.2%) for 5 weeks (IACUC protocol #20-0462). Female mice were used to allow for group housing throughout the study. Fifteen animals per cohort were euthanized after each week of cuprizone or vehicle to extract brains. Of these, 5 were used for histological analysis and 5 for laser-capture microdissection. Euthanasia was performed via exsanguination under CO2 and confirmed with cervical dislocation. Brains were dissected coronally (Bregma −1.0 to −1.7 mm) and snap-frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound with 2-methyl butane. Brain sections (7 µm) were stained with Histogene (Applied Biosystems) for 45 s followed by dehydration immediately before microdissection using Arcturus XT (Applied Biosystems). RNA was extracted using a PicoPure® RNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems) from the microdissected corpus callosum and amplified using Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 (NuGen). A total of 50 ng amplified complementary DNA was used for Nextera Library (Illumina) preparation for RNA-Seq.

For solochrome myelin staining studies, the model was induced as follows: C57BL/6 mice were fed a lab diet with or without cuprizone (0.3%) for 5 weeks (IACUC protocol #20-0462). 4 animals were euthanized after 5 weeks on cuprizone, without recovery, while additional groups were removed from cuprizone and administered PRN2675 or vehicle for 4 days before euthanization. Euthanasia was performed via exsanguination under CO2 and confirmed with cervical dislocation. Female mice were used to allow for group housing throughout the study. Brains were extracted from PBS-perfused mice, drop-fixed for 24 h in PFA (4%), and moved to PBS with 0.01% azide. Brains were then shipped to a third party (NeuroScience Associates, Knoxville, TN) for dissection, tissue staining, and imaging. After overnight immersion in 20% glycerol and 2% dimethylsulfoxide, brains were placed in a gelatin matrix using MultiBrain®/ MultiCord® Technology (NeuroScience Associates). Sections were cut with an AO 860 sliding microtome and placed into a solution of 50% PBS pH7.0, 50% ethylene glycol, 1% polyvinyl pyrrolidone, prior to solochrome staining. HALO (Indica Labs, version 2.3) was used to measure solochrome stain area.

RNA processing and analysis

RNA was shipped to a third party (BGI Americas) for processing. The RNA-Seq library was prepared using poly-A selected RNA followed by Illumina’s strand-specific library construction protocol. RNA-Seq was performed with the DNBseq platform to a depth of 30 million reads per sample using 2 × 100 bp reads.

Data were analyzed with Array Studio (Version 11, Omicsoft Corporation). Paired reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome (B38, GenCodeV19) using OSA453. Expression measurements (transcripts) were collected as both counts and fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM). FPKM was calculated for each gene using the EM algorithm54.Transcripts were considered lowly expressed and filtered out if they had counts ≤15 in ≥2 replicates per group. Furthermore, only transcripts mapping to protein coding genes were retained. After applying these filters, 15,055 FPKM transcripts remained. Next, FPKM data were quantile normalized to the 75th percentile followed by log2 transformation (log2[FPKM + 1]). Differential expression analysis was performed in Array Studio (Version 11, Omicsoft Corporation) using a general linear model. DEGs were those with absolute(FC) > 1.2 and p < 0.05.

Mouse in vitro cell cultures

Cell culture procedures

For murine mixed glial cultures, brains from 4-day-old C57BL/6 mice were harvested and pooled in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F12-GlutaMAX media (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), transferred into warm 0.25% trypsin (2 mL/brain) and incubated at 37 °C while rotating for 30 min. Tissues were dissociated and filtered through a 70 µm cell strainer. The single-cell suspension was plated in T150 tissue culture flasks (1 flask/mouse). Cells were fed with a complete medium change 5, 8, and 11 days later. Mixed glia were seeded in Poly-D-Lysine (PDL)-coated black 96-, 12-, or 6-well plates at 2.5 × 104, 1.5 × 105, or 3 × 105 cells/well, respectively, and cultured for 12 days for in vitro experiments. On Day 12, mixed glial cells were trypsinized and single cell suspensions were counted. To isolate primary murine microglia, the EasySep Mouse CD11b Positive Selection Kit (StemCell, #18970) was used with EasySep Magnets (StemCell, #18000) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For ELISA, isolated microglia were plated at 5 × 104 cells/well in PDL-coated 96-well plates. For qRT-PCR, microglia were seeded at 1.5 × 106 cells/well in 12-well plates. For Western blot, microglia were seeded at 3 × 106 cells/well. Cells were rested for 24–48 h before stimulation.

BV-2 cells (amsbio, AMS.EP-CL-0493) were seeded in six-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/well in serum-free DMEM/high glucose/GlutaMAX media (Gibco 10566016). Cells were rested for 24 h before stimulation.

Generation of complexed/aggregated mouse IgG

IgG from mouse serum (10 mg, Sigma, I5381) was suspended in 1 mL sterile PBS. The solution was incubated at 62 °C for 30 min. Solution was centrifuged (18,000 × g) for 20 min and supernatant containing complexed IgG was collected. A bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, 23225) was used to determine final protein concentration. Cells were treated with 400 μg/mL of the resultant complexed mouse IgG stock for 15 min at 37 °C.

Complexed mouse IgG was only applied to murine cells. For all human cells, Fc OxyBURST™ (10 μg/mL; Invitrogen, F2902) was instead used, which is rabbit polyclonal anti-BSA antibody complexed with a BSA covalently linked to dichlorodihydrofluorescein (H2DCF).

pBTK ELISA

A PathScan® P-BTK (Y223) ELISA kit (Cell Signaling, 23843) was used for pBTK ELISA.

Western immunoblot

Protein concentration was measured using BCA reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein samples were run on NUPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Midi Gels (Life Technologies, NP0321) along with 10 μL of Chameleon Duo Pre-stained Protein Ladder (LI-COR, 928-60000). Protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the iBlot Transfer machine and iBlot Gel Transfer Stacks PVDF Regular (Life Technologies, 1340109). Membranes were blocked in Odyssey TBS blocking buffer (LI-COR, 927-50000) containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against BTK (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Cat# 8547S), and β-actin (1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich, #A5441). Thereafter, membranes were incubated with LI-COR secondary antibodies (1:5000), imaged on an Odyssey CLx (LI-COR) and quantified using LI-COR software.

RNA processing and analysis

Twenty-four primary cell culture samples (Table S1) stored in Qiazol (Qiagen) were shipped to a third-party (Genewiz) for RNA isolation, quality control, and further processing. The RNA-Seq library was prepared using poly-A selected RNA followed by Illumina’s strand-specific, library construction protocol. RNA-Seq was processed on the Illumina HISeq with 2 × 150 bp reads with single index per lane.

Data analysis and quality assessment were as described above for cuprizone. Paired reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome (mm10, ENSEMBL.R89) using OSA453. Methods for expression measurement collection, FPKM calculation54, filtering transcripts, and determining DEGs were as described above (cuprizone model). In this experiment, 12,790 FPKM transcripts remained after filtering. Independent 6- and 24-h tolebrutinib gene signatures were established by identifying DEGs that were increased upon IgG stimulation and corrected with tolebrutinib.

Human in vitro microglia culture and tri-culture

All iPSC lines were purchased from Fujifilm. The iPSC lines fall under the global MSA agreement that Sanofi has in place with FCDI. The cells have been reviewed and approved by the Sanofi ethics department. The parental iPSC lines used to create these products (identified as 01434 and 01279) are registered on Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Registry (hPSCreg) where a third party ethical review of the ICF was performed and certified, confirming that informed consent was obtained. For lines 01434 and 01279, respective accrediting authorities and approval numbers are NICHD-NIH (N01-HD-4-2865) and Rush University IUCAC (13-034 and 14-072). More information about legal use can be found at FujiFilm Cellular Dynamics, Inc. (fujifilmcdi.com).

Cell culture procedures

Human iPSC-derived microglia (FujiFilm, 01279) were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in PDL-coated 96-well plates and maintained in iCell Glial Base Medium with supplements (Fujifilm).

For human iPSC-derived tri-cultures, astrocytes (Fujifilm, ASC-100-020-001-PT) were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells/well in Matrigel (Corning, 354277) coated 96-well plates on Day 1 and maintained in DMEM/F-12 (Gibco) with 2% heat-inactivated FBS and N-2 supplement (Gibco, 17502-048). Motor neurons (Fujifilm, C1048) were seeded at 3.5 × 104 cells/well in the wells containing astrocytes on Day 3 and maintained in iCell Neural Base Medium (Fujifilm, M1010) with Neural Supplement A (Fujifilm, M1032) and Nervous System Supplement (Fujifilm, M1031). Microglia (Fujifilm, 01279) were seeded at 2.0–5.0 × 104 cells/well in the wells containing both astrocytes and motor neurons on Day 6 or 10 and maintained in tri-culture medium of iCell Neuron medium with Microglia Supplement A (Fujifilm, M1036), Microglia Supplement B (Fujifilm, M1037) and Neural Supplement C (Fujifilm, M1035). The tri-culture cells were cultured until Day 15 with half tri-culture medium change every other day.

Bulk RNA-Seq and analysis

Monocultures or tri-cultures were pre-treated with 100 nM tolebrutinib for 30 min before Fc OxyBURST™ (10 μg/mL; Invitrogen, F2902) incubation for 6 h. Following lysis with RLT buffer (100 μL per well in 96-well plate; Qiagen, 79216), samples were frozen for RNA analysis.

Monoculture sample processing and RNA-Seq was performed as follows: RNA quality was determined using Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent, 5067-1513) with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer according to manufacturer’s instructions. Bulk RNA-Seq libraries were prepared using Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, mRNA was isolated from 1 μg total RNA using oligo(dT) magnetic beads. The captured mRNA was used as input for library preparation. Library quality control and concentration were performed and determined using Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq500 platform.

Triculture sample processing and RNA-Seq were performed by BGI Americas. The RNA-Seq library was prepared using the Smart-Seq2 protocol. RNA-Seq was performed with the DNBseq platform to a depth of 30 million reads per sample using 2 × 100 bp reads. Data analysis methods were as described above for the EAE bulk RNA-sequencing data analysis, with sequence reads mapped to the human B38 reference genome.

Immunoassays

Monocultures or tri-cultures were pre-treated with 100 nM tolebrutinib for 30 min before Fc OxyBURST™ (10 μg/mL; Invitrogen, F2902) incubation for 24 h. Supernatant was collected for Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) multiplex immunoassay, using the human proinflammatory panel 1 kit (MSD, K15049D), human chemokine panel 1 kit (MSD, K15047D), and human cytokine panel 1 kit (MSD, K15050D). Where specified (Fig. S10), the supernatant was collected 24 h after tolebrutinib and Fc OxyBURST™ (10 μg/mL) administration, which was added 24 h after Fc OxyBURSTTM alone. For TNF-α ELISA (human microglia monoculture), to determine the tolebrutinib IC50, microglia were pretreated for 30 min with tolebrutinib (9-point serial dilution) or DMSO equivalent. Supernatants were collected after overnight incubation (18 h) and quantified using the human TNF-α ELISA kit (Invitrogen, KHC3011).

Immunocytochemistry

Tri-cultures were fixed on Day 12 with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 h in antibody dilution buffer (5% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% Triton-X 100 in PBS). The following antibodies were applied to the fixed cells overnight at 4 °C: BTK (1:250; Cell Signaling, #8547S), beta-III tubulin (1:100; Millipore Sigma, #MAB1637), IBA1 (1:500; Abcam, #ab5076), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:500; Millipore Sigma, #AB5541). Cells were washed with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in a secondary antibody solution of anti-Rabbit AlexaFluor488 (Abcam, #ab150061), anti-Mouse AlexaFluor647 (Thermo Scientific, #A32787TR), anti-Goat AlexaFluor647 (Abcam, #ab150135), and anti-Chicken AlexaFluor647 (Abcam, #ab150175), all at 1:1000 dilution. Following incubation, cells were washed with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS followed by PBS. Cells were imaged using an Opera Phenix™ High Content Screening System (PerkinElmer) with 20× water objective.

Other in vitro cell cultures

Cell culture procedures

THP1 cells (THP1-Lucia NF-κB monocytic cell line, Invivogen, thpl-nfkbv2) were seeded in 96-well plates at 1 × 105 cells in 200 μL per well, immediately before stimulation. Tolebrutinib or vehicle was added 30 min before stimulation with Fc OxyBURST™ (Invitrogen).

Human brain samples

Sample processing

Frozen human brain tissues were obtained from the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center at University of California Los Angeles (Table S2). Post-mortem derived tissue (50 mg) was homogenized and lysed in 1% Triton lysis buffer (TBS). After centrifugation (13,000 × g), supernatant was collected as the soluble fraction. Lysis buffers contained protease and phosphatase inhibitors (1:100 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, #78444).

Transcriptomic signature

Derivation of the transcriptomic signature was as previously described32. Briefly, bulk RNA library preparation and sequencing of independent brain tissue sections RNA was extracted from 25 frozen brain sections according to the “Purification of Total RNA from Microdissected Cryosections” method of the Qiagen RNeasy Micro kit, with Dnase I (Cat# 74004; Qiagen). The integrity of the and the quantification were determined using a Bioanalyzer RNA 6000 Pico chip on the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Cat# 5067-1513, Agilent). Strand-specific RNASeq libraries were created using the TruSeq stranded mRNA library prep Kit (cat# RS-122-2101, Illumina). The library sizes and quantification were determined using the Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA kit (Cat# 5067-4626, Agilent). The libraries were sequenced using the HiSeq2000 (Illumina). Bulk RNA data processing, statistical analysis, and pathway enrichment analysis of patient tissue samples All data processing from the QC of FASTQ files to the derivation of DEGs was performed within Array Studio (Version 10, Omicsoft Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). Data quality was assessed using the “Raw Data QC Wizard” function within Array Studio. The sequence used to trim the adapters from the reads was “AGATCGGAAGAGCG.” Paired reads were mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh38, GenCode.V24) using the Omicsoft Aligner 4 (OSA4)53. The EM algorithm was implemented to calculate the FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million) value for each gene30. Lowly expressed genes were filtered out. Additionally, the genes were filtered to retain only protein coding genes. Next, the samples were normalized (upper quantile) followed by a log2 transformation (Log2[FPKM + 1]). The Student’s T-tests was performed to determine which genes were significantly differentially expressed between groups. Genes were considered significantly altered if p-value < 0.05 and the absolute fold-change in expression was ≥1.2.

Immunohistochemistry

Fixed human brain tissue was sectioned at 20 μm (Rapid Autopsy program) with a cryostat. IHC was performed with the Ventana DISCOVERY ULTRA platform (Roche Tissue Diagnostics). Slides were rehydrated, rinsed twice in PBS for 5 min and wet loaded into the Ventana. Primary antibodies against BTK (1:20; Cell Signaling, Cat# 8547S), CD68 (1:1000; Dako, Cat# M0814), and proteolipid protein (1:1000; Abcam, Cat# ab183493) were diluted in antibody dilution buffer (Roche, #ADB250) and applied to the slides (100 μL/slide). Slides were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h before addition of UltraMap anti-Rabbit HRP (Roche, #760-4315) or anti-Mouse HRP (Roche, #760-4313). Signal detection was carried out using Discovery Purple (Roche, #760-229) and ChromoMap DAB (Roche, # 05266645001) and counterstaining with hematoxylin (Roche, #760-2021) and bluing solution (Roche, #760-2037). Slides were removed from the Ventana, dehydrated, and coverslipped with Cytoseal XYL (Epredia). Slides were imaged using a Zeiss Imager Z1 microscope with a Zeiss AxioCam MRm digital camera and Zen Pro 2012 Imaging Software. HALO (Indica Labs, version 2.3) was used to determine IBA1-positivity and BTK-positivity by measuring in each image the IHC signal and overlaying this “digital signal” back over the original image.HALO was also used to determine BTK colocalization (Discovery purple) with CD68 (ChromoMap DAB). For immunofluorescence, tissues were stained as described above for BTK and IBA1 (1:500; Abcam, #ab5076) using fluorescent secondary antibodies, anti-Rabbit AlexaFluor488 (Abcam, #ab150061) and anti-Goat AlexaFluor647 (Abcam, #ab150135), at 1:1000 dilution, and coverslipped with anti-fade media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. N represents biological replicates, with each point depicting an individual mouse or human sample, or the mean of technical replicates from cells isolated from separate litters of mice. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software, version 9 and p-values are indicated by * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01, *** ≤ 0.001, and **** ≤ 0.0001. P-values were determined by paired or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction, or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or two-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey, Sidak or Dunnett’s test, or Mann Whitney U test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank Rita Balice-Gordon, Tarek Samad, and Lamya Shihabuddin for their critical feedback on the work that would become this manuscript. We also thank Matija Zelic, Tim Owens, Michelle Francesco, Deepak Rajpal, Maria Fitzgerald, Sarah Strattman, and Kathy Klinger for their support during the course of these studies. This manuscript was reviewed by Svend S. Geertsen, Ph.D., of Sanofi. Medical writing assistance was provided by Richard J. Hogan, PhD, and Conor F. Underwood, Ph.D., of Envision Pharma Group, and editorial and graphics assistance was provided by Envision Pharma Group. Writing, editorial, and graphics support were funded by Sanofi. Human tissue was obtained from Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center (HBSFRC) at University of California Los Angeles. This study was funded by Sanofi.

Author contributions

Designed the experiments: R.C.G., G.S.W., D.O., S.K.R., E.H., and N.P., A.Cho, and E.C. Collected the data: R.C.G, G.S.W., L.L., N.H., N.C., T.R.H., A.Che, M.L., S.K.R, N.P., A.Cho, and E.C. Analyzed the data: R.C.G., G.S.W., A.S.B., M.R.D., N.C., M.Z., L.L., A.M., D.O., E.H., A.Cho, and E.C. Wrote the original draft of the manuscript: R.C.G., G.S.W., D.O., and E.H. Critically reviewed and approved the manuscript: T.J.T., B.D.T, and all other authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Renzo Mancuso, V. Wee Yong and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Murine and in vitro transcriptomic data are accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. GEO Accessions GSE281176 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE281176), GSE281177 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE281177), GSE281178 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE281178), GSE281180 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE281180), GSE281386 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE281386), GSE281907 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE281907). Patient transcriptomic data are accessible at https://www.synapse.org/ (Synapse ID syn63995416). Patient data availability is subject to controlled access on Synapse, due to privacy concerns. Please contact the corresponding author (Dimitry Ofengeim Dimitry.Ofengeim@sanofi.com) to request access to this dataset. Requests for dataset access will be addressed within 7 days. Data use agreements impose the following restrictions on data: In order to access the database users are prohibited from using Identifying Data contained within the database to identify a Donor or any biological relative of a Donor. All other data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data files. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

R.C.G., N.C., and N.P. were employees of Sanofi when this work was undertaken. G.S.W., A.S.B., L.L., M.R.D., N.H., M.L., T.R.H., A.Che, S.R., M.Z., E.H., A.M., T.J.T., and D.O. are employees of Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. ACho and EC declare that they have no competing interests. B.D.T has received consulting fees, speaker honoraria, and/or research funding from Biogen, Disarm Therapeutics, EMD Serono, Novartis, Renovo Neural, and Sanofi; and principal investigator and/or speaking fees from Alkermes, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Sanofi, and TG Therapeutics.