Summary

To understand racism and its impact on health in South Korea, it is essential to consider the political and social context of the migrant population, including ethnic Korean migrants, marriage migrants, migrant workers, and bi-ethnic adolescents. This paper has two goals. First, we examined the increasing trends of the foreign population in South Korea, with a focus on the growth of migrant workers and marriage migrants. Following this, we reviewed the historical contexts and discussed the characteristics of racism in South Korea: ‘ethnic homogeneity’, ‘White supremacy’, and ‘ethnic discrimination against ethnic Koreans’. Second, we conducted a systematic review of 43 articles on the association between discrimination and health among racially and ethnically minoritized populations in South Korea. The review revealed statistically significant associations across various migrant groups but highlighted several limitations: all studies were cross-sectional, many used non-standardized discrimination measures, all focused on interpersonal discrimination, most examined mental health outcomes, and certain migrant groups were neglected in the research. Future research is needed to address these gaps.

Funding

This work was supported by the New Faculty Startup Fund from Seoul National University.

Keywords: Racism, Health, Migrant, Systematic review, South Korea

Introduction

Racism exists everywhere, affecting marginalized populations who face oppression due to their ethnicity, migratory status, race, skin color, and others.1 These marginalized groups often encounter social exclusion and an unequal distribution of resources. Racial and ethnic discrimination can be systemic, operating within societal structures or institutions, as well as interpersonal, impacting daily interactions and potentially fostering the internalization of discriminatory beliefs.2

Previous epidemiological studies have extensively examined the link between experiences of racial and ethnic discrimination and health outcomes.3, 4, 5 While these studies have undoubtedly enhanced our understanding of how discrimination harms the health of oppressed groups, many of them have primarily focused on individual-level epidemiologic associations, often overlooking the broader historical, political, economic, and social contexts that breed and sustain discriminatory practices.6 Several insightful studies have highlighted the need to consider these larger structural contexts, such as color-blind laws and regional segregation, which contribute to health inequities.6,7 By contextualizing discrimination from their structural roots, researchers can better understand societal-level solutions targeting structural determinants of discriminatory practices.

In South Korea, studies have examined the association between discrimination and health outcomes among racially and ethnically minoritized groups, including marriage migrants and migrant workers from Asian countries. Although the discrimination experienced by racially and ethnically minoritized groups is shaped by unique historical backgrounds, these previous studies often lack a comprehensive explanation of the underlying political and social dynamics.8,9 Without reference to these contexts, these studies are not sufficient to understand how discrimination is produced and reproduced at the societal level, how the system restricts lifetime opportunities and harms the health conditions of marginalized groups, and how to effectively intervene to change this system.

In this paper, we had two goals. First, we summarized the increasing trends and current status of the migrant population in South Korea and described the key characteristics of racism in the country within its unique historical context. Second, we conducted a systematic review of discrimination and health among racially and ethnically minoritized individuals residing in South Korea to understand how racial and ethnic discrimination had been measured and what research had been conducted. Based on this review, we proposed future research directions to address the identified gaps and needs.

History of migrant populations in South Korea

In the early 20th century, amidst the global expansion of imperialism, Korea fell under Japanese colonial rule (1910–1945). Despite both Koreans and Japanese categorized under the label of the ‘yellow race’ from a Western perspective, Koreans were treated as an inferior race under Japanese rule as a justification for Japan's occupation over the Korean peninsula.9 Under Japanese governance, Koreans experienced systematic differentiation and discrimination.

Following independence from Japanese rule and the subsequent Korean War (1950–1953), South Korea emerged as an economically impoverished country, leading to labor emigration.10 However, rapid economic development transformed South Korea from a labor-sending to a labor-receiving country. Since the 1980s, an influx of migrants, particularly unskilled workers and marriage migrants from low-income countries, altered the demographic landscape of South Korea. Despite their historical victimization by racism during the Japanese imperial era, Koreans have undergone a transition and now, as the majority population, exhibit discriminatory attitudes and enforce structural and policy-based discrimination towards ethnically and racially minoritized groups in South Korea.

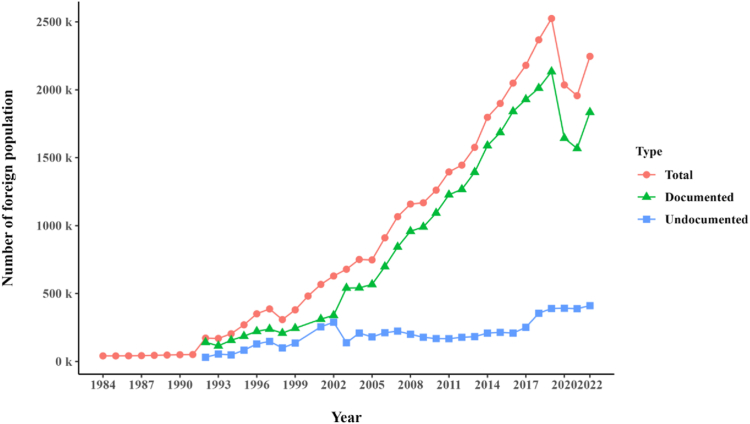

The foreign population in South Korea has steadily increased since the 1980s (see Fig. 1). As of 2022, the total foreign population staying in South Korea, regardless of visa status or length of stay, was 2,245,912.11 Of these, 1,688,855 were documented residents who had been in the country for 91 or more days including ethnic Koreans with foreign nationalities. This consistent growth has been primarily driven by two factors: labor shortages and a lack of potential marriage partners for men.

Fig. 1.

Trends of foreign population in South Korea, 1984 to 2022. The total foreign population in South Korea includes all foreign residents who do not hold South Korean nationality. This encompasses both documented foreign nationals, regardless of their visa status or length of stay, and undocumented foreign nationals who have overstayed their permitted period but remain in the country. Please note that for the data in the year 2000, Korean government statistics did not provide information on undocumented migrants who had stayed for less than 91 days. As a result, we were unable to present separate numbers for the documented and undocumented foreign populations for that year and used only the total foreign population in the graph.

Sources: Yearbook of Korea Immigration Statistics by the Korean Ministry of Justice (1984–2022).

Labor shortages stem from the country's rapid economic growth. Until the early 1990s, the South Korean government did not have an official labor importation program.12 However, with the increasing demand for unskilled labor, the number of undocumented workers entering the country on tourist or visit visas and working without permission surged from 4217 in 1987 to 41,877 in 1991.12,13 Relaxing entry restrictions for major national events such as the 1988 Olympics further contributed to the surge in undocumented migrant workers.14

In response to the increasing number of undocumented migrants, the South Korean government introduced the Industrial Technical Training Program in 1991 to import low-skilled migrant workers.12,13 This program favored the acceptance of ethnic Koreans living outside of Korea, particularly Korean Chinese, thereby maintaining closed-door policies against other ethnic groups.15 However, the trainee system denied migrant workers the status of laborers, and these workers operated without a legal basis under labor law, leading to issues such as unpaid wages and exploitation by employers.16 Consequently, it contributed to the increase in undocumented workers who fled from their designated workplaces and sought employment within the country without proper authorization.

In 2004, the South Korean government replaced the trainee system with the ‘Employment Permit System’ (EPS) (see Panel 1),16 which targeted unskilled migrant workers from various Asian countries such as Vietnam, Nepal, and Cambodia. For ethnic Koreans, separate short-term employment visa programs were introduced, such as the ‘Employment Management Program for Overseas Ethnic Koreans’ in 2002 for service sectors and the ‘Visit and Employment Program’ in 2007.17

Panel 1. Employment Permit System, migrant workers and racism in South Korea.

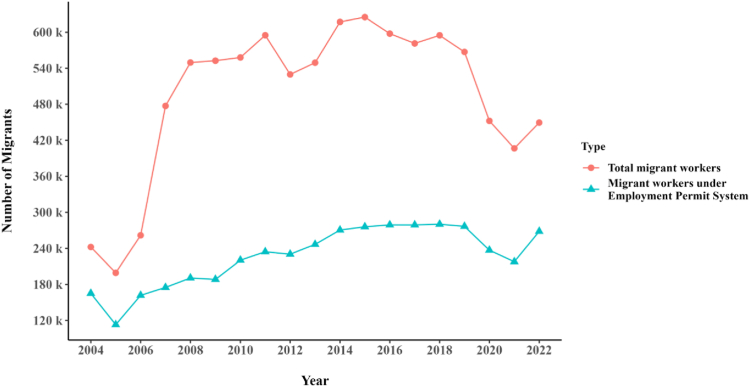

Since 2004, the EPS in South Korea enabled small and medium-sized businesses, which struggled to find native Korean laborers, to legally employ unskilled migrant workers from pre-selected countries.16 The government oversaw the entry, exit, and stay of these workers, who were granted non-professional work visas (E9). As of 2024, the EPS included 17 sending countries: the Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Indonesia, China, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Bangladesh, East Timor, Vietnam, Pakistan, Nepal, Laos, and Tajikistan.18,19 In 2022, there were 449,402 residents in South Korea with long- and short-term work-related visas (E1–10, H2, and C4) (see Fig. 2). Of these, 268,413 held E9 visas and the number of E9 migrant workers in South Korea has increased and continues to rise.

Fig. 2.

Trends of the migrant worker population in South Korea, 2004 to 2022. The total migrant worker population includes holders of E1-E10, H2, and C4 visas. Migrant workers under the Employment Permit System are limited to those with E9 visas.

Sources: Yearbook of Korea Immigration Statistics by the Korean Ministry of Justice (2004–2022).

The EPS allowed the employment of migrant workers only in industries—small and medium-sized manufacturing, construction, mining, selected service sectors, agriculture, fisheries, and livestock businesses—that were typically avoided by native Korean workers.20 Under this system, migrant workers signed contracts with employers in South Korea while in their home countries and were not allowed to change their workplace after arriving in South Korea.16 Although some exceptions permitted workplace changes, most cases were determined at the discretion of the employer.

Workers under this program were initially allowed to work in South Korea for three years, extendable by an additional year and ten months if their employer requested it.21 After this period, they could re-enter South Korea after a short break (three or six months, depending on the reemployment program). Re-entry required passing a special Korean language test or being recognized as a “diligent worker” by their employers with no history of changing workplaces.

The difficulty of changing workplaces and the requirement of employer consent for extending the employment permit period led to a power imbalance between employees and employers. Consequently, E9 workers frequently endured poor working conditions and became overly dependent on their employers, which could lead to exploitative relationships. These workers continuously reported a range of abuse and exploitation, including wage theft, sexual harassment, violation of employment contract, forced labor, precarious residency status, physical abuse, and personal disregard.22,23 Although Korean labor laws technically covered E9 workers, their unfair situations were often neglected due to imbalanced power relations with employers and insufficient institutional support.

A scarcity of potential marriage partners for rural bachelors (see Panel 2), results from several factors, including the migration of Korean women to urban areas in search of education, employment, and marriage opportunities.24 This phenomenon caused a notable rise in international marriage migration to South Korea, particularly in rural areas. Initially, international marriage migration primarily involved Korean men marrying Korean Chinese women, largely due to shared ethnic backgrounds.25 However, towards the late 1990s, there was a distinct shift towards marriages with women from Southeast Asian countries.26

Panel 2. Marriage migrants and intersectionality in South Korea.

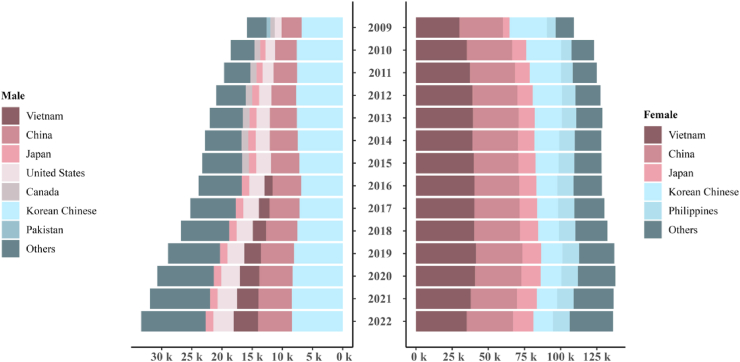

As of 2022, there were 169,633 migrants with spouse visas in South Korea, reflecting a steady increase since the 1990s (see Fig. 3). Among the marriage migrant population, female marriage migrants outnumbered their male counterparts, with the majority being Chinese (including Korean Chinese), followed by Vietnamese, Japanese, and Filipinas. Male marriage migrants were primarily Chinese (including Korean Chinese), followed by Vietnamese, Americans, and Japanese.

Fig. 3.

Trends of the marriage migrant population in South Korea, 2009 to 2022. The marriage migrant population includes holders of F13, F21, F52, F61, F62, and F63 visas.

Sources: Yearbook of Korea Immigration Statistics by the Korean Ministry of Justice (2009–2022).

International marriage was promoted by local governments to address demographic challenges in rural areas, which was further facilitated by the growth of commercial international marriage agencies.26,29,30 These agencies frequently arranged marriages through mail-order bride systems, where men selected their brides from a list of potential candidates after paying a fee. This practice raised serious concerns about human trafficking, as women in these arrangements had little to no choice in the process and were often unaware of key details about their future husbands or marriages.30

Many female marriage migrants came from lower-income countries than South Korea, participating in these arrangements with the hope of improving their financial situations. However, such marriages were typically sought by Korean men from lower economic backgrounds in rural areas who struggled to find a native Korean spouse.29 As a result, they often failed to meet the financial aspirations of the female marriage migrants, leaving these women trapped in socioeconomically disadvantaged conditions in South Korea.

Additionally, female marriage migrants frequently faced challenges compounded by the intersectionality of migratory status and gender. They were often forced into traditional gender roles upheld by patriarchal norms.25,31 These roles demanded extensive care work, traditionally expected of daughters-in-law, particularly caring for their husbands’ elderly parents. These roles also included responsibilities associated with motherhood and being a wife, such as childbearing and childcare.26

Female marriage migrants' residency status was often precarious, as obtaining citizenship required at least two years of marriage and residency, with their husband's consent.29,30 This structural dependency on their husbands for legal status, combined with patriarchal norms, often led to significant power imbalances within these marriages. These imbalances could result in domestic violence, marital rape, and everyday control, severely limiting marriage migrants' ability to escape oppressive situations.30,32,33

In 1990, only 619 marriages between migrant women and Korean men were officially registered.27 By 2004, this number had increased to 25,594. This increase reflects the growing prevalence of cross-national marriages in South Korea during this period. The rise in marriage migrants inevitably led to an increase in the number of bi-ethnic children and adolescents within the country.28 This demographic shift carries profound implications for social dynamics, cultural diversity, and the integration of immigrant populations into South Korean society.

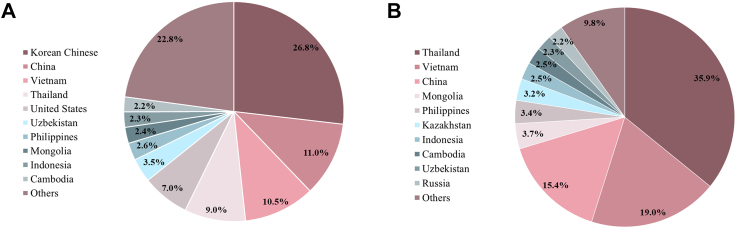

As of the end of 2022, the total number of migrants residing in South Korea was 2,245,912 (see Fig. 4). Among these, approximately 18.3% were undocumented individuals, with the majority coming from Asia. Within the documented migrant population, 26.8% were Korean Chinese, and 11.0% were non-Korean ethnic Chinese, followed by Vietnamese and Thai individuals. As South Korea faces a declining domestic population and a growing reluctance among native Korean workers to undertake manual labor, the trend of increasing migrant population is expected to persist.

Fig. 4.

Foreign population in South Korea by country of origin in 2022. A-Total foreign population by country of origin (N = 2,245,912) B-Undocumented foreign population by country of origin (N = 411,270, 18.3% of the total population). The total foreign population in South Korea includes all foreign residents who do not hold South Korean nationality. This encompasses both documented foreign nationals, regardless of their visa status or length of stay, and undocumented foreign nationals who have overstayed their permitted period but remain in the country.

Sources: Yearbook of Korea Immigration Statistics, Korean Ministry of Justice (2022).

Racism in South Korea

To understand the discrimination faced by migrants in contemporary South Korea, it is essential to consider the contextual and socially constructed nature of this phenomenon, which is deeply rooted in the country's unique historical experiences. This study identified and explored three key characteristics of discrimination against racially and ethnically minoritized groups residing in South Korea.

Ethnic homogeneity

‘Ethnic homogeneity’ is a fundamental element of racial and ethnic discrimination in South Korea that refers to maintaining a singular Korean ethnicity. Historically, ethnic homogeneity has been a prominent political ideology in Korean society, dating back to the era of Japanese colonial rule over Korea from 1910 to 1945. During this period, the Japanese empire propagated the idea of racial superiority of the Japanese people as a justification for colonizing Korea.9 Concurrently, they promoted assimilation policies that highlighted the shared ancestry between Koreans and Japanese, aiming to suppress Korean independence movements and encourage participation in World War II.9,34

In response, Korean intellectuals fostered a sense of patriotism to defend independence and nurture ethnic nationalism to safeguard their identity.9 Ethnicity served as the foundation for collective identity, rooted in shared lineage, history, and language, in the absence of a formal state system. The concept of ‘one single nation (Hanminjok)’ emerged, uniting Koreans into a territorial and historical community with a common ancestor, Dangun. Dangun symbolized the mythical founder of ancient Korea, embodying the aspiration for a unified Korean state that spanned the peninsula and beyond. The narrative of Dangun, marking the beginning of Korean history, continues to feature in contemporary Korean history textbooks and school curricula.35

Following liberation from colonial rule and the establishment of the Republic of Korea after the Korean War (1950–1953), the idea of ‘one single nation’ persisted as a political ideology that supported modernization, national cohesion, various political slogans, and national mobilization.36 Consequently, the myth of ethnic homogeneity became deeply ingrained in Korean society. This steadfast adherence to ethnic homogeneity in modern Korean society now manifests in discrimination against other ethnic groups and the perception of multicultural youths as individuals who do not fit into the category of ‘pure Koreans’.

White supremacy

The concept of ‘White supremacy’ holds a pervasive presence in South Korea, mirroring patterns observed in other regions across the globe. This racial hierarchy, which places individuals of White, often European descent at the apex, traces its origins to the Age of Discovery from the late 15th century when Europeans began distinguishing themselves from non-White populations across the global South. Over time, this distinction was rationalized and institutionalized, with Black individuals in particular being unjustly labeled as inherently inferior during the 19th century. Korean intellectuals, particularly during the late 19th century modernization period, uncritically embraced these Western notions of racial superiority.37,38 Influenced by Confucian ideals of social hierarchy, early modern Korean intellectuals readily adopted these Western imperialist racial hierarchies, fostering an admiration for perceived White racial superiority while reinforcing the inferiority of Black and non-White individuals.38,39

During the Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945, Korea witnessed a shift where ethnicity became more historically significant than phenotypic differences based on skin color.40 However, with the arrival of American military occupation following liberation in 1945 and the emergence of multiracial social groups between American soldiers and Koreans, discrimination based on skin color resurfaced.41,42 Multiracial individuals, due to their physical differences and association with U.S. military bases, became stigmatized and were often viewed as shameful entities to be concealed in Korean society. While all multiracial individuals faced discrimination, those of multiracial between people of color and Koreans endured even more severe discrimination, due to the prevailing White supremacist ideologies in Korean society. This discriminatory mindset persisted into the 21st century, and contributes to ongoing discrimination against people of color, especially those from lower-income countries in comparison to South Korea.

Ethnic discrimination against ethnic Koreans

Ethnic discrimination against ethnic Koreans, despite their shared ethnic heritage and physical appearance is also widespread. As stated, discrimination against racially and ethnically minoritized populations in Korea is rooted in the notions of ethnic homogeneity and White supremacy. On the other hand, ethnic return migrants, who came back to their ancestral land after South Korea's rapid economic growth, have also encountered discrimination based on their historical backgrounds.

Korean Chinese people, currently comprising the largest group of foreign nationals in South Korea, serve as a prominent example. Since the 19th century, numerous Koreans migrated to China, seeking refuge from famine or attempting to establish a Korean government in exile during the period of Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945.43 In the 1990s, amid South Korea's struggle with labor shortages and a scarcity of potential female marriage partners in rural areas, these ethnically Korean Chinese migrants were considered preferred candidates to address these issues while posing less threat to ethnic homogeneity.24,44 This led to a significant increase in return migration. However, upon their return to South Korea, they faced extensive discrimination. They were stigmatized due to their identifiable accents and disadvantaged socioeconomic status, and were often perceived as criminals or poor compatriots by native-born Koreans.45 Many were restricted to non-permanent manual labor visas, and the areas where most of them settled were regionally segregated and perceived as dangerous.46,47

North Korean defectors provide another example. Throughout the Cold War era and the Korean War (1950–1953), South Korea and North Korea maintained extremely limited interactions due to ongoing political and ideological conflicts.48 Since the mid-1990s, natural disasters, famines, and economic hardships in North Korea have prompted many North Koreans to flee, leading to an increase in their migration to South Korea.48,49 North Koreans entering South Korea were regarded not only as defectors due to Cold War ideology, but also as refugees seeking asylum or economic migrants in search of a better life.50 However, they frequently encounter challenges related to stigmatization and discrimination by native-born Koreans due to differences in accent, vocabulary, and level of education, which affect their job opportunities, wages, and overall socioeconomic status.49

Based on this history, racism, and ethnic discrimination remains a key determinant of health for ethnically and racially minoritized individuals in contemporary South Korea. As such, the following section will explore the literature around racial and ethnic discrimination, and health with an emphasis on migrants in South Korea.

Systematic review

Racism is widely recognized as a significant social determinant of health globally.1 Several systematic reviews conducted in Western contexts have consistently demonstrated an association between racial and ethnic discrimination and adverse mental and physical health outcomes.3,4,51 To contribute to the South Korean literature around racism and health, this paper reviewed the existing studies on racial and ethnic discrimination and its association with the health of migrants in South Korea.

Methods

Search strategy

This study reviewed journal articles from Korean and international sources, focusing on the association between discrimination against racially and ethnically minoritized individuals in South Korea and health. The review included articles published online from the earliest records available until the end of 2022, restricted to peer-reviewed sources in English or Korean, excluding books, theses, and conference proceedings. Widely used web-based electronic databases, both international and Korean, were utilized. For international databases, PubMed, ERIC (ProQuest and EBSCO), PsycInfo, and Web of Science were utilized, while RISS and KoreaMed were used for Korean databases. The search was conducted on February 19, 2024. Supplementary material 1 provides a comprehensive list of search terms employed.

Eligibility criteria

This review focused on i) peer-reviewed empirical articles, ii) presenting quantitative data regarding the association between discrimination and health, and iii) among racially and ethnically minoritized individuals living in South Korea.

Most research conducted on migrants in South Korea did not include questions on discrimination that specifically assessed race or ethnicity. Therefore, in this review, the measure of discrimination was not restricted to experiences based solely on race and ethnicity but encompassed all forms of discrimination encountered by racially and ethnically minoritized individuals in Korean society. Hence, general measures of discrimination, such as the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS),52 were incorporated into the review.

Moreover, we included studies that explicitly used discrimination as an independent variable. We excluded studies that used composite variables, where discrimination was one of several subcategories within a broader concept. For example, our review excluded studies that used the Acculturative Stress Scale (ASS), which was desinged to measure adjustment problems in international students through multiple subscales, including perceived discrimination, threat to cultural identity, homesickness, fear, and others.53 However, studies that extracted the ‘discrimination’ subscale and used it as an independent variable were included, as they explicitly targeted discrimination as a distinct category.

Health and well-being were broadly considered outcome measures. This approach included general health measures where mental or physical health was unspecified, as well as unmet healthcare needs, ensuring a holistic understanding of health outcomes in relation to discrimination among racially and ethnically minoritized individuals in South Korea.

Only studies that examined a direct association between discrimination-related independent variables and health-related dependent variables were included. We excluded studies where discrimination or health was positioned as a mediator rather than as an exposure or outcome.

Screening and study selection

The search results from the web database were imported into Endnote 20, where duplicates were eliminated. All articles underwent a two-stage screening process. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by HYL, EJP, and MH to determine eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Articles that received a ‘review’ vote from at least one reviewer proceeded to the next stage. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were then obtained, and each full text underwent screening to confirm eligibility. Any conflicts or discrepancies were resolved through discussion among all reviewers and SSK, resulting in a final decision regarding inclusion.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted and coded using Microsoft Excel by HYL. The extracted data included study design, data source, sample size, exposure measures, outcome measures, participant characteristics, and association results. GRL double-checked the coding, and disagreements were resolved by SSK.

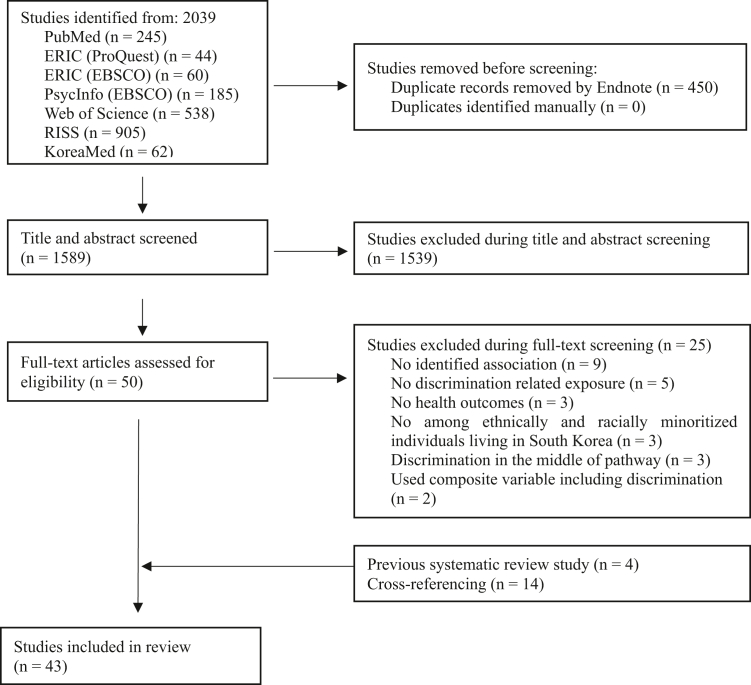

A flowchart (Fig. 5) was created to demonstrate the article selection process and reasons for exclusion. Descriptive analysis was used to examine the trend and distribution of the included studies. Furthermore, the studies were grouped by the immigrant status of the participants (e.g., marriage migrants), and an overview of their characteristics and association findings was provided. Meta-analysis was not conducted in this review due to the heterogeneity in the types of measures and samples included across the literature.

Fig. 5.

Flow chart of article selection process.

Results

Study selection

Web database searches for both English and Korean initially yielded 2039 articles. Following the removal of 450 duplicates, we screened 1589 articles, of which 50 proceeded to full-text screening based on their titles and abstracts. 25 studies were excluded following full-text screening.

The primary reasons for exclusion were non-quantitative studies, as well as studies with irrelevant exposure or health outcomes. Additionally, studies not focused on racially and ethnically minoritized people residing in South Korea, such as research on Korean Americans in the United States, were excluded. Studies that used discrimination-related variables in the middle of the pathway or utilized a composite variable including discrimination as one of its subcategories were also excluded. Consequently, there were 25 total included studies from the database search.

In addition to the database search, our study reviewed four additional papers identified from a previous systematic literature review conducted in 2015 on experiences of discrimination and health in the total population of South Korea.54 This previous review included 21 papers related to migrants in South Korea, and four of these papers additionally met our study's eligibility criteria. An additional 14 papers found through citation searching met our eligibility criteria were included. A total of 43 studies were included in this research. Fig. 5 provides a summary of the screening stages and the corresponding article numbers.

Description of the studies

The key characteristics of the included articles are summarized in Table 1. Most of the studies were published between 2015 and 2022 (86.1%), and all of them used a cross-sectional study design. Twenty studies (46.5%) utilized public datasets, with 16 of them relying on the National Survey of Multicultural Families (NSMF), a nationally representative dataset initiated in 2009. Of the remaining four studies, each used a distinct survey dataset. One study utilized data from the Survey on Living Conditions of Foreign Workers in Korea, while another analyzed the Survey on Foreign Residents, both commissioned by the Ministry of Justice and conducted by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Migration Research and Training Centre in South Korea. Additionally, a third study used the Survey on Immigrants’ Living Conditions and Labor Force (SILCLF), an integrated dataset from the Ministry of Justice and Statistics Korea since 2017. The fourth study analyzed data from the National Survey on Family Violence in 2010, which included North Korean refugees. Apart from these, 23 studies used non-public datasets.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of 43 empirical quantitative studies of discrimination and health against racially and ethnically minoritized groups residing in South Korea.

| Number of studies | % of total studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of studies | 43 | 100 |

| Year of publication | ||

| 2011–2014 | 6 | 14.0 |

| 2015–2018 | 19 | 44.2 |

| 2019–2022 | 18 | 41.9 |

| Study design | ||

| Cross-sectional | 43 | 100.0 |

| Sample size (number of participants) | ||

| <100 | 3 | 7.0 |

| 101–200 | 5 | 11.6 |

| 201–300 | 10 | 23.3 |

| 301–1000 | 6 | 14.0 |

| 1001- | 19 | 44.2 |

| Data source | ||

| Public datasets | 20 | 46.5 |

| National survey of multicultural families (representative sampling) | 16 | 80.0 |

| Survey on living conditions of foreign workers in Korea (representative sampling) | 1 | 5.0 |

| Survey on foreign residents (representative sampling) | 1 | 5.0 |

| Survey on immigrants' living conditions and labor force (representative sampling) | 1 | 5.0 |

| National survey on family violence (non-representative sampling for North Korean refugees) | 1 | 5.0 |

| Non-public datasets (primary data collection) | 23 | 53.5 |

| Discrimination measurementa | ||

| Revised existing developed scales | 18 | 41.9 |

| Everyday discrimination scale52 | 7 | 38.9 |

| The racism and life experience scale55 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Acculturative stress scale53 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Major and everyday discrimination scale52 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and environment acculturative stress56 | 2 | 11.1 |

| The cultural adaptation and adjustment scale57,b | 1 | 5.6 |

| Everyday discrimination scale,52 acculturative stress scale for international students,53 College student's perceptions of prejudice and discrimination scale58 | 1 | 5.6 |

| Non-standardized questionnaire | 25 | 58.1 |

| Exposure number of items | ||

| Single item | 14 | 32.6 |

| 2–8 items | 14 | 32.6 |

| 9 or more | 14 | 32.6 |

| Not reported | 1 | 2.3 |

| Outcome | ||

| Mental health | 32 | 74.4 |

| Depressive symptoms | 13 | 40.6 |

| Life satisfaction | 9 | 28.1 |

| Depressive symptoms and anxiety | 4 | 12.5 |

| Psychosocial maladjustmentc | 2 | 4.7 |

| Depressive symptoms and self-esteem | 1 | 3.1 |

| Suicidal ideation | 1 | 3.1 |

| Self-esteem | 1 | 3.1 |

| Well-being | 1 | 3.1 |

| Physical health and psychological distress (including depressive symptoms and anxiety)d | 1 | 2.3 |

| General health | ||

| Self-rated health | 8 | 18.6 |

| Health-risk behavior | ||

| Alcohol use disorder | 1 | 2.3 |

| Unmet healthcare needs | 1 | 2.3 |

| Participant characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| Adults | 33 | 76.7 |

| Children and adolescents | 8 | 18.6 |

| Adults & Children and adolescents | 2 | 4.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Male and female | 28 | 65.1 |

| Female only | 14 | 32.6 |

| Female mother and all sex children and adolescents | 1 | 2.3 |

| Immigrant status | ||

| Marriage migrantse | 15 | 34.9 |

| Multicultural children and adolescents | 8 | 18.6 |

| International studentse | 6 | 14.0 |

| Refugees | 5 | 11.6 |

| Migrant workers | 4 | 9.3 |

| Multicultural children and adolescents and their marriage migrant motherse | 2 | 4.7 |

| Multicultural family members | 1 | 2.3 |

| Foreign residents | 1 | 2.3 |

| Ethnic Koreans (Korean Chinese) | 1 | 2.3 |

When modified versions of scales were utilized, the originated scales were described here.

We were unable to find the exact reference mentioned in the related study. Therefore, we cited a reference that has the same title as mentioned in the related study but from a different year.

Psychosocial maladjustment included measures of anxious/depressed, social problem, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior.

Physical health included measures of headaches, insomnia, gastrointestinal symptoms, cardiovascular symptoms and psychological distress included overall level of distress, including irritability, fatigue, numbness, anxiety, depressive symptoms, feelings of worthlessness, etc.

Some literature specified that Ethnic Koreans (Korean Chinese) were included as one of their participants.

In terms of discrimination measurement tools, 18 studies (41.9%) employed scales developed by international researchers, most of which were adapted to the Korean context without language validation, through mere translation or modification. Among these, multiple studies utilized the EDS,52 the Racism and Life Experience Scales (RaLes),55 the Perceived Discrimination Subscale of the ASS,53 the Major and Everyday Discrimination Scale (MEDS),52 and Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environment Acculturative Stress scale (SAFE).56 The remaining 25 studies utilized non-standardized questionnaires, with 14 studies solely assessing the experience of discrimination through a single question.

When categorizing studies according to health outcomes, the majority, 32 studies (74.4%), focused exclusively on mental health. Among these, 13 studies concentrated solely on self-reported depressive symptoms, measured using original or shortened versions of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D),59 the depressive symptoms subscales of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL),60 or a single question asking whether participants experienced depressive symptoms within a certain timeframe.

Other mental health indicators examined included life satisfaction, depressive symptoms and anxiety, psychosocial maladjustment, suicidal ideation, self-esteem, and well-being. Life satisfaction was measured using scales derived from the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS),61 the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SLS),62 or a single question. Depressive symptoms and anxiety were assessed using the HSCL, CES-D and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),63 or subscales from the Korean Youth Self-Report (K-YSR), derived from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).64 Psychosocial maladjustment was also measured using the K-YSR. Suicidal ideation was evaluated through a five-item questionnaire,65 while self-esteem was measured using a questionnaire based on the Rosenberg Self–Esteem Scale (SES).66 Well-being was assessed using the Concise Measure of Subjective Well-Being Scale (CMSWBS), developed by Korean scholars to reflect the Korean context.67

In addition to mental health outcomes, several studies investigated other health aspects. Eight studies focused on self-rated health as the health outcome. Separate studies examined unmet healthcare needs, alcohol use disorder, and both physical health problems and psychological distress. Self-rated health and unmet healthcare needs were each measured by a single question. Alcohol use disorder was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), developed by the World Health Organization.68 Physical health problems were evaluated through a self-reported questionnaire, while psychological distress was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10).69

Regarding the characteristics of the study participants, 33 studies (76.7%) targeted adults, while eight studies (18.6%) focused on children and adolescents. In terms of gender distribution, 28 studies (65.1%) included both males and females as participants, while 14 studies (32.6%) exclusively focused on females.

In terms of immigrant status, 15 studies (34.9%) primarily focused on marriage migrants, and eight studies (18.6%) focused on multicultural children and adolescents. Additionally, there were six studies (14.0%) on international students, five studies (11.6%) on refugees, and four studies (9.3%) on migrant workers. Two studies explored multicultural children and adolescents along with their marriage migrant mothers. Other studies investigated multicultural family members from African countries, foreign residents, and ethnic Koreans (Korean Chinese).

The characteristics of each study, categorized by immigrant status, are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of each included empirical study on health and discrimination against ethnically and racially minoritized groups residing in South Korea, categorized by immigrant status (N = 43).

| Author (Year) | Study population | Data source (representative sampling Y/N) | Exposure | Specific discrimination-related domain/contexts measured | Exposure measurea | Health outcome | Health outcome measurea | Statistically significant association between discrimination and health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marriage migrants | ||||||||

| Kim et al. (2022)70 | Marriage migrant women aged 19–65 originated from China, Vietnam, and the Philippines (n = 7685). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2015) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Life satisfaction | Single question | Yes (negative) |

| Cho et al. (2020)71 | Marriage migrant women aged 19–54 originated from Vietnam (n = 212). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Depressive symptoms | 10 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression | Yes (positive) |

| Kim et al. (2020)72 | Marriage migrants with disabilities or with disabled family members aged >18 (n = 1066). The specific country of origin is not reported. |

National Survey of Multicultural Families (2018) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Life satisfaction | Single question | No (unrelated) |

| Kim et al. (2020)73 | Marriage migrant women originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines, and Japan (n = 6960). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2015) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Good self-rated health | Single question | Mixed Yes (negative) for Han-Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean-Chinese, and Filipina participants No (unrelated) for Japanese participants |

| Park et al. (2019)74 | Marriage migrant women with a mean age of 36.6 (n = 12,414). The specific country of origin is not reported. |

National Survey of Multicultural Families (2015) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experience in a list of places (i) streets or neighborhoods, (ii) stores, restaurants, banks, and so forth, and (iii) public offices (district offices, police stations, etc.) (iv) at workplace (v) school or childcare facility | Non-standardized questions | Depressive symptoms | Single question | Yes (positive) |

| Yi et al. (2018)75 | Marriage migrant women currently working in South Korea aged 19–64 originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and other countries (n = 8142). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2015) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Unmet healthcare needs | Single question | Yes (positive) |

| Kwon (2018)76 | Marriage migrant women with a mean age of 37.4 (n = 14,464). The specific country of origin is not reported. |

National Survey of Multicultural Families (2015) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Life satisfaction | Single question | Yes (negative) |

| Kim (2016)77 | Marriage migrant women with a mean age of 32.0 originated from China, Vietnam, and other countries (n = 40,430). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2009) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experience in a list of places (i) streets or neighborhoods, (ii) stores, restaurants, banks, and so forth, and (iii) public offices (district offices, police stations, etc.) (iv) by landlords or real estate agents (v) at work | Non-standardized questions | Poor self-rated health | Single question | Yes (positive) |

| Kim et al. (2016)78 | Marriage migrants aged >19 originated from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, Mongolia, Thailand, Cambodia, Uzbekistan, South Asia (including Nepal, Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Bhutan), East South Asia (including Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, and Laos), Russia, North America (including the United States of America and Canada), Western Europe (including Germany, England, Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands), Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), and other regions (n = 14,406). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2012) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Poor self-rated health | Single question | Mixed Yes (positive) for female participants No (unrelated) for male participants |

| Kim (2016)79 | Marriage migrant women originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, and the Philippines (weighted n = 165,451). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2012) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Good self-rated health | Single question | Yes (negative) |

| Ryu (2016)80 | Marriage migrant women with a mean age of 31.3 originated from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Thailand, Cambodia, Mongolia, and other countries (n = 400). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Major and Everyday Discrimination Scale | Physical health problem (headaches, insomnia, gastrointestinal symptoms, cardiovascular symptoms) and psychological distress (overall level of distress, including irritability, fatigue, numbness, anxiety, depressive symptoms, feelings of worthlessness, etc.) | For physical health problems: headache (4-item questionnaire), insomnia (4-item questionnaire), gastrointestinal symptoms (8-item questionnaire), and cardiovascular symptoms (8-item questionnaire) For psychological distress: Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) |

Yes (positive) |

| Kim et al. (2015)81 | Marriage migrants aged >19 originated from Western countries (US, Canada, western Europe, etc.), non-Western countries-Asia (China including Korean Chinese, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Mongolia, Thailand, Cambodia, etc.), non-Western countries-others (Russia, Uzbekistan, etc.) (n = 14,485) | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2012) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experience in a list of places (i) streets or neighborhoods, (ii) stores, restaurants, banks, and so forth, and (iii) public offices (district offices, police stations, etc.) (iv) at work (v) school or childcare facility | Non-standardized questions | Poor self-rated health | Single question | Mixed Yes (positive) for participants from non-Western countries and female participants, after full adjustment No (unrelated) for participants from Western countries except for discrimination at work and male participants, after full adjustment |

| Yun et al. (2015)82 | Marriage migrant women with a mean age of 30.80 originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines, and Cambodia (n = 3041). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2012) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Good self-rated health | Single question | Yes (negative) |

| Cho et al. (2014)83 | Marriage migrant women (n = 226,084). The specific country of origin is not reported. |

National Survey of Multicultural Families (2012) (Y) National Survey of Multicultural Families (2009) was used to compare participants' characteristics and their self-rated health |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Good self-rated health | Single question | Yes (negative) |

| Sung et al. (2013)84 | Marriage migrant women originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines (n = 55,877). | National Survey of Multicultural Families (2009) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experience in a list of places (i) streets or neighborhoods, (ii) stores, restaurants, banks, and so forth, and (iii) public offices (district offices, police stations, etc.) | Non-standardized questions | Life satisfaction | Single question | Mixed Yes (negative) for Korean Chinse, Han Chinese and Vietnamese No (unrelated) for Filipina |

| Multicultural children and adolescents | ||||||||

| Ko et al. (2020)85 | Multicultural children and adolescents, ranging from elementary to high school students (n = 192). Their immigrant mothers originated from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Mongolia, and other countries. |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | The Racism and Life Experience Scale | Subjective wellbeing (Subjective happiness) | Concise Measure of Subjective Well-Being Scale (9-item questionnaire) | Yes (negative) |

| Kim et al. (2019)86 | Multicultural children and adolescents aged 9–18 (n = 5476). The specific country of origin of their parents is not reported. |

National Survey of Multicultural Families (2015) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experiences from five possible perpetrators: peers, teachers, extended family members, neighbors, and strangers | Non-standardized questions | Depressive symptoms | Single question | Mixed Yes (positive) for participants who experienced discrimination by friends and strangers in urban areas and participants who experienced discrimination by friends and neighbors in rural areas No (unrelated) for participants who experienced discrimination by teachers, extended family members, and neighbors in urban areas and participants who experienced discrimination by teachers, extended family members, and strangers in rural area |

| Seol et al. (2018)87 | Multicultural children with a mean age of 11.92 (n = 131). Their immigrant parents originated from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Thailand, the United States, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, and Russia |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Self-esteem | Rosenberg Self–Esteem Scale (10-item questionnaire) | Yes (negative) |

| Yun et al. (2018)88 | Multicultural children and adolescents in 4th–6th grade (n = 684). The specific country of origin of their parents is not reported. |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Perceived discrimination subscale from the Cultural Adaptation and Adjustment Scale | Life satisfaction | Spiritual Well-Being Scale (10-item questionnaire) | Yes (negative) |

| Kim et al. (2017)89 | Multicultural children and adolescents in 4th–6th grade (n = 204). The specific country of origin of their parents is not reported. |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Psychosocial maladjustment (anxious/depressed, social problem, rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior) | Child Behavior Check List (14-item questionnaire for anxious/depressed, 7-item questionnaire for social problems, 11-item questionnaire for rule-breaking behavior, 19-item questionnaire for aggressive behavior) | Yes (positive) |

| Park et al. (2016)90 | Multicultural children and adolescents aged 9–18 (n = 4141). Their immigrant parents originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Mongolia, Thailand, Cambodia, Russia, Uzbekistan, the European Union, the United States, Canada, and other countries. |

National Survey of Multicultural Families (2012) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experiences from five possible perpetrators: peers, teachers, family members and relatives, neighbors, and strangers | Non-standardized questions | Depressive symptoms | Single question | Yes (positive) |

| Kim et al. (2011)91 | Multicultural children and adolescents of marriage migrant women in 3rd–6th grade (n = 113). Their immigrant mothers originated from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and other countries. |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environment Acculturative Stress Scale | Depressive symptoms and anxiety | 16 items from the Child Behavior Check List (16-item questionnaire for anxious/depressed) | Yes (positive) |

| Kim (2011)92 | Children of immigrant women (n = 120) and Korean children (n = 136) in 1st–6th grade. Their immigrant mothers originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and other countries. |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Psychosocial maladjustment (anxious/depressed, social problem, rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior) | 21 items from the Child Behavior Check List (14-item questionnaire for anxious/depressed, 7-item questionnaire for social problems) 4-item questionnaire for rule-breaking behavior, 6-item questionnaire for aggressive behavior |

Yes (positive) in the model with mediator (stress) |

| International students | ||||||||

| Kim et al. (2021)93 | Chinese international students (n = 133) and Vietnamese international students (n = 124). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized questions | Depressive symptoms and anxiety | 25 items from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (15-item questionnaire for depressive symptoms, 10-item questionnaire for anxiety) | Yes (positive) |

| Suh et al. (2019)94 | Asian international students aged >18 originating from South-East Asia, East Asia, Middle-East, and West Asian regions (n = 121). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination (personal rejection and unfair treatment) | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Depressive symptoms and anxiety | 20 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression and 21 items from Beck Anxiety Inventory | Yes (positive) |

| Jin et al. (2019)95 | Chinese international students (including Korean Chinese) (n = 216). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized questions | Life satisfaction | 5-item questionnaire | Yes (negative) |

| Min et al. (2018)96 | International students with a mean age of 26.26 (n = 61). The specific country of origin is not reported (43 students were from Asia). |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale, Perceived discrimination subscale from Acculturative Stress Scale, discrimination related questions from College Student's Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination Scale | Depressive symptoms | 6 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression | Yes (positive) |

| Park et al. (2017)97 | Chinese international students with a mean age of 21.3 (n = 400). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Perceived discrimination subscale from Acculturative Stress Scale | Alcohol use disorder | Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (10-item questionnaire) | Yes (positive) with mediator (depressive symptoms) |

| Jin et al. (2011)98 | Chinese international students with a mean age of 23.03 (n = 201). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Perceived discrimination subscale from Acculturative Stress Scale | Depressive symptoms | 20 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression | Yes (positive) |

| Refugees | ||||||||

| Um et al. (2020)99 | North Korean female refugees residing in South Korea aged 19 years or older (n = 273). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination (postmigration discrimination) | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Suicidal ideation | 5-item questionnaire for suicidal ideation | Yes (positive) |

| Noh et al. (2018)100 | North Korean refugees with a mean age of 36.19 (n = 500). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Everyday Discrimination Scale | Life satisfaction | 5 items from the Satisfaction With Life Scale | Yes (negative) with mediator (stress) |

| Lee et al. (2016)101 | North Korean female refugees with a mean age of 39.2 (n = 87). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | The Racism and Life Experience Scale | Depressive symptoms | 20 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression | Yes (positive) |

| Um et al. (2015)102 | North Korean refugees with a mean age 41.1 (n = 261). | National Survey on Family Violence (2010) (N) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Depressive symptoms | 20 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression | Yes (positive) |

| Cho (2011)103 | North Korean refugees aged >19 (n = 500) | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Major and Everyday Discrimination Scale | Depressive symptoms and anxiety | 25 items from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (15-item questionnaire for depressive symptoms, 10-item questionnaire for anxiety) | Yes (positive) |

| Migrant workers | ||||||||

| Kim et al. (2022)104 | Migrant workers residing in South Korea with a mean age of 30.1, originating from Vietnam and Cambodia (n = 214). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environment Acculturative Stress Scale | Depressive symptoms | 10 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression | No (unrelated) This study analyzed moderation effect of social support on the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, and perceived discrimination was not statistically significant. |

| Song et al. (2022)105 | Migrant workers who entered Korea under the Employment Permit System, originating from Vietnam, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, Mongolia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, China (excluding Korean-Chinese), Kyrgyzstan, and Pakistan (n = 1370). | Survey on Living Conditions of Foreign Workers in Korea (2013) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Good self-rated health | Single question | Yes (negative) |

| Yu (2020)106 | Migrant workers originating from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Uzbekistan, Indonesia, Cambodia, Nepal, North America, Europe, and Oceania (n = 4614). | Survey on Immigrants' Living Conditions and Labor Force (2018) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experience in a list of places (street/neighborhood, stores/restaurants/banks, workplace) | Non-standardized questions | Life satisfaction | Single question | Mixed Yes (negative) for experiencing of discrimination in street/neighborhood and workplace No (unrelated) for experience of discrimination in stores/restaurants/banks |

| Choi et al. (2018)107 | Migrant workers with a mean age of 35.68 (n = 668). The specific country of origin is not reported. |

Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experience in a list of places (street/neighborhood, stores/restaurants/banks, workplace, transportation, etc.) | Non-standardized questions | Depressive symptoms | 5 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (2-item questionnaire for depressed mood and 3-item questionnaire for malaise) | Yes (positive) |

| Others | ||||||||

| Chung et al. (2016)108 | Children and adolescents of immigrant women with a mean age of 12.52 (n = 164) and their immigrant mothers with a mean age of 41.23 (n = 164). Mothers originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Mongolia, and others. |

Non-public (N) | Maternal perceived discrimination | None | The Racism and Life Experience Scale | Adolescents' psychological adjustment (a combination of high levels of self-esteem and low levels of depressive symptoms) | Rosenberg Self–Esteem Scale (10-item questionnaire) for adolescents' self-esteem The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (the number of items was not reported) for adolescents' depressive symptoms |

Yes (negative) with mediator (maternal depressive symptoms) |

| Lee et al. (2021)109 | Children and adolescents of immigrant women aged 11–18 (n = 2446) and their immigrant mothers (n = 2446). Mothers originated from China (including Korean Chinese), Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and other countries |

National Survey of Multicultural Families (2018) (Y) |

Children and adolescents' perceived discrimination; maternal perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Children and adolescents' depressive symptoms | Single question | Mixed Yes (positive) between children and adolescents'’ perceived discrimination and their depressive symptoms No (unrelated) between maternal perceived discrimination and their children and adolescents' depressive symptoms |

| Choi et al. (2019)110 | Multicultural African family members residing in South Korea (n = 64). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | Discrimination experience in a list of places (street/neighborhood, stores/restaurants, public institutions, workplace) | Non-standardized questions | Life satisfaction | 4-item questionnaire | No (unrelated) |

| Ra et al. (2019)111 | Foreign residents aged >19, originating from Western countries (the United States or Canada), East Asia (China, Japan, Taiwan), and South Asia (Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, and Cambodia) (n = 1068). | Survey on Foreign Residents (2012) (Y) |

Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Depressive symptoms | 7 items from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (7-item questionnaire for depressive symptoms) | Yes (positive) |

| Hong (2019)112 | Korean Chinese return migrants aged >18 (n = 292). | Non-public (N) | Perceived discrimination | None | Non-standardized single question | Depressive symptoms | 20 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression | Mixed Yes (positive) for participants who had a stronger Korean identity No (unrelated) for participants who had a stronger Chinese identity |

When modified versions of scales were utilized, the originated scales were described here.

Marriage migrants

Among the fifteen studies on marriage migrants,70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84 twelve focused exclusively on females,70,71,73, 74, 75, 76, 77,79,80,82, 83, 84 including participants from the major female marriage migrant nationalities such as China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Japan.

To assess the independent variable of perceived discrimination, nine studies relied on a single question asking participants if they had ever experienced discrimination.70,72,73,75,76,78,79,82,83 One study used the EDS,71 and another employed the MEDS.80 Four studies used non-standardized questions that listed specific places where discrimination occurred, such as streets and stores.74,77,81,84

The dependent variables used in the studies were self-rated health (n = 7),73,77, 78, 79,81, 82, 83 life satisfaction (n = 4),70,72,76,84 depressive symptoms (n = 2),71,74 unmet healthcare needs (n = 1),75 and physical health (headaches, insomnia, digestive symptoms, and cardiovascular symptoms) and psychological distress (overall level of distress, including irritability, fatigue, numbness, anxiety, depressive symptoms, feelings of worthlessness, etc.) (n = 1).80 Apart from two studies that used a 10-item CES-D to measure depressive symptoms71 and a self-rated questionnaire to assess physical health problems and psychological distress using the K10,80 all other studies employed a single question to measure health outcomes.70,72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79,81, 82, 83, 84

Of the fifteen studies examined, ten found that marriage migrants who experienced discrimination were more likely to report worse health outcomes of self-rated health, life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, unmet healthcare needs, and physical health and psychological distress.70,71,74, 75, 76, 77,79,80,82,83

Four studies presented mixed findings regarding the association between perceived discrimination and health outcomes. Of these, three indicated that the association varied by region or country of origin. One study noted that discrimination was negatively associated with good self-rated health among female Han-Chinese (the majority ethnic group in China, named after the Han dynasty, a significant period in Chinese history), Korean Chinese, Vietnamese, and Filipino migrants but not among female Japanese migrants.73 Another reported a negative association between perceived discrimination and life satisfaction among female Han-Chinese, Korean Chinese, and Vietnamese migrants, with no statistically significant association observed among Filipinas.84 A third study observed a positive association between perceived discrimination and poor self-rated health among non-Western marriage migrants, however this was not the case among Western marriage migrants, except in the workplace.81 The association was also statistically significant among female marriage migrants, but not among males. The last study found a positive association between perceived discrimination and poor self-rated health across all participants, particularly among females, but not males.78

Additionally, one study found no association between perceived discrimination and life satisfaction among marriage migrants with disabilities or disabled family members.72 This study proposed that strong social networks among co-nationals, those who share the same nationality, might buffer the perception of discrimination.

Multicultural children and adolescents

Among the eight studies focusing on multicultural children and adolescents,85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92 five reported the nationalities of the participants’ mothers or parents,85,87,90, 91, 92 primarily from China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Japan.

The independent variable in these studies was measured using multiple tools: the EDS (n = 3),87,89,92 the RaLes (n = 1),85 the SAFE (n = 1),91 and perceived discrimination subscale of the Cultural Adaptation and Adjustment Scale (n = 1),88 and non-standardized questions (n = 2).86,90

The dependent variables examined included depressive symptoms (n = 2),86,90 psychosocial maladjustment (n = 2),89,92 depressive symptoms and anxiety (n = 1),91 subjective well-being (n = 1),85 life satisfaction (n = 1),88 and self-esteem (n = 1).87 The two studies focusing on depressive symptoms used a single question to determine if participants had experienced depressive symptoms in the past 12 months.86,90 Psychosocial maladjustment, and depressive symptoms and anxiety were assessed using the K-YSR.89,91,92 Other studies utilized the CMSWBS,85 SES,87 and SWBS.88

All but one study reported that multicultural children and adolescents who experienced discrimination were more likely to report worse health outcomes of depressive symptoms, psychosocial maladjustment, depressive symptoms and anxiety, subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and self-esteem.85,87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92 The exception found a mixed association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, noting that this association varied by both the perpetrator (peers, teachers, family members and relatives, neighbors, or strangers) and the residential setting (rural or urban).86

International students

Among the six studies on international students,93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98 three specifically focused on Chinese students.95,97,98 One study included both Chinese and Vietnamese students,93 and another focused on Asian international students.94 The remaining study did not specify the participants’ countries of origin.96

In these studies, the independent variable, perceived discrimination, was measured using various tools. Two studies employed the perceived discrimination subscale from the ASS,97,98 and one used the EDS.94 Another study utilized a combination of the EDS, the perceived discrimination subscale of ASS, and specific questions from College student's Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination Scale.96 Additionally, two studies used non-standardized questions.93,95

The dependent variables examined in the studies included depressive symptoms (n = 2),96,98 depressive symptoms and anxiety (n = 2),93,94 life satisfaction (n = 1),95 and alcohol use disorder (n = 1).97 Two studies assessed depressive symptoms using the CES-D.96,98 To evaluate depressive symptoms and anxiety, one study employed the HSCL93 while another used CES-D and BAI.94 Life satisfaction was measured with a 5-item questionnaire,95 and alcohol use disorder was assessed using the AUDIT.97

All studies found that international students who experienced discrimination were more likely to have worse health outcomes of depressive symptoms, depressive symptoms and anxiety, life satisfaction, and alcohol use disorder.93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98

Refugees

The five studies focused on North Korean refugees,99, 100, 101, 102, 103 with two studies exclusively including female migrants.

The independent variable was measured using various tools: the EDS in two studies,99,100 the RaLes in one,101 scales derived from the MEDS in one,103 and a single question asking whether participants had experienced hardships due to discriminatory and prejudicial attitudes from their South Korean counterparts in one study.102

The dependent variables in the studies included depressive symptoms (n = 2),101,102 depressive symptoms and anxiety (n = 1),103 suicidal ideation (n = 1),99 and life satisfaction (n = 1).100 Depressive symptoms were measured using the CES-D in two studies,101,102 depressive symptoms and anxiety were assessed with the HSCL,103 life satisfaction was evaluated using the SLS,100 and suicidal ideation was measured using a 5-item questionnaire.99

All studies consistently reported that North Korean refugees who experienced discrimination were more likely to have worse health outcomes of depressive symptoms, depressive symptoms and anxiety, suicidal ideation, and life satisfaction.99, 100, 101, 102, 103

Migrant workers

Among the four studies on migrant workers, all included both female and male participants.104, 105, 106, 107

To measure independent variable, a modified version of the SAFE was used in one study,104 while non-standardized questions were employed in three others.105, 106, 107 Of these, one study used a single question asking whether participants had ever been treated differently because they were from other countries while living in Korea.105

The dependent variables examined included depressive symptoms (n = 2),104,107 self-rated health (n = 1),105 and life satisfaction (n = 1).106 Depressive symptoms were measured by using the CES-D in two studies,104,107 while the other outcomes were assessed with a single question.105,106

Two studies reported that migrant workers who experienced discrimination were more likely to report worse health outcomes of depressive symptoms107 and self-rated health.105 One study identified a mixed association, noting that perceived discrimination in streets, neighborhoods, and workplaces had a statistically significant negative impact on life satisfaction, whereas discrimination in stores, restaurants, and banks was not associated with life satisfaction.106 Another study, focused on the moderation effect of social support, found no association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among Vietnamese and Cambodian migrant workers in the model with social support.104

Others

Two studies focused on multicultural children and adolescents along with their migrant mothers.108,109 In the first study, a statistically significant negative association was found between mothers' experiences of perceived discrimination and the psychological adjustment of their adolescent children, with maternal depressive symptoms as a mediator in the pathway.108 The other study found a mixed finding that adolescents' discrimination experience was positively associated with their depressive symptoms however, their migrant mothers' experience of discrimination was not associated with the adolescents’ discrimination experience.109

One study involving multicultural African family members found no association between the experience of discrimination and life satisfaction.110 This study assessed discrimination using non-standardized questions and measured life satisfaction with a 4-item questionnaire.

Another study focusing on foreign residents reported a statistically significant association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, with discrimination measured by a single question and depressive symptoms assessed using the HSCL.111

The last study on Korean Chinese return migrants revealed a statistically significant positive association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among those identifying more as ‘Korean’ than ‘Chinese’, but not among those who identified more with ‘Chinese’.112 This study utilized a single question to measure discrimination and the CES-D to assess depressive symptoms.

Discussion

This study reviewed the history of migrant populations in South Korea and sought to identify the unique characteristics of racism and discrimination stemming from this history. We conducted a systematic review to examine the association between discrimination and health among racially and ethnically minoritized individuals living in the country. Of the 43 studies reviewed, 40 demonstrated a statistically significant mixed or overall association between discrimination and health across various immigrant groups, including marriage migrants, multicultural children and adolescents, international students, North Korean refugees, and migrant workers.

While the majority of studies in the review found a statistically significant positive association between discrimination and worse health outcomes, it is important to note that all of these studies are cross-sectional in design. This study design poses potential issues, such as reverse causality and the risk of overinterpretation. For example, one study examined the impact of maternal experiences of perceived discrimination on their adolescents’ health outcomes using cross-sectional data, highlighting the need for caution in interpretation.108 Longitudinal study designs for racially and ethnically minoritized people in South Korea would be further necessary.5,113,114

Although a few studies in this review differentiated participants based on their country or region of origin or ethnicity, the majority neglected the participants’ racial or ethnic backgrounds. They merely grouped participants with different characteristics into one category based on immigrant status. For instance, many studies grouped Korean Chinese individuals with other immigrant populations solely based on their immigrant status, such as “marriage migrant.” However, as ethnic Koreans, they share cultural and ethnic heritage with native-born Koreans and thus possess different social relationships compared to other migrant groups. This means their experience of discrimination would be qualitatively different from that of other migrant groups.

One study focused solely on Korean Chinese individuals and interestingly found differences in the association between perceived discrimination and health outcomes depending on the participants’ perceived ethnic identity.112 The study indicated that individuals with Korean ethnicity might perceive discrimination by native-born Koreans as inner-group isolation, which led to worse health outcomes. Future research needs to consider the historical and social characteristics of racially and ethnically minoritized groups to examine the association between discrimination and health outcomes among these groups in South Korea.

More than half of the studies in the review utilized non-standardized measures of discrimination, often relying on a single question: “Have you ever been discriminated against or neglected based on ethnicity or nationality while living in Korea?” Although some studies included additional questions about the perpetrators and locations of discrimination, the scenarios presented were limited, potentially overlooking complex nature of racial and ethnic discrimination. Additionally, studies that used standardized scales to measure experiences of discrimination often modified original scales developed abroad to fit the Korean context without verifying translations or used only subjectively selected items. Future research needs to employ measures that capture diverse scenarios of discrimination and develop a standardized discrimination experience scale tailored to the context of migrants in South Korea.

Moreover, all studies in this review focused solely on perceived interpersonal discrimination. We found no studies that measured systemic or internalized discrimination in relation to individuals' health outcomes. Previous research, mainly from the United States, has consistently reported on the health impacts of structural discrimination, such as residential segregation or color-blind laws and policies.6 Future studies should pay attention to the health impacts of structural discrimination within the South Korean context. For example, they could analyze the health impacts of residential segregation and stigmatization of Korean Chinese communities, as well as the health impacts of institutional limitations under the EPS.16,46 One study in this review included internalized stigma in the association pathway.87 Future research also needs to focus more on the health impacts of internalized discrimination.

This review found that most of the studies focused on the mental health, with only one study examining physical health. Previous research in Western settings has included diverse mental and physical health outcomes, such as depression and cardiometabolic diseases.3 The biological pathway of discrimination's health impacts is well-defined: experiences of discrimination act as stressors, triggering increased cortisol secretion via the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal axis and persistent activation of the sympathetic nervous system, leading to various physiological responses.115 Prolonged or repeated activation of these responses can have detrimental effects on physical health, including obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension. Future research should broaden the range of health outcomes to capture the diverse health impacts of racial and ethnic discrimination in South Korea, and the different pathways between racism and health across individual and structural means.