Abstract

Background

Etoricoxib is a highly selective COX-2 inhibitor which was evaluated for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Double-blind, randomized, placebo and active comparator-controlled, 12-week study conducted at 67 sites in 28 countries. Eligible patients were chronic NSAID users who demonstrated a clinical worsening of arthritis upon withdrawal of prestudy NSAIDs. Patients received either placebo, etoricoxib 90 mg once daily, or naproxen 500 mg twice daily (2:2:1 allocation ratio). Primary efficacy measures included direct assessment of arthritis by counts of tender and swollen joints, and patient and investigator global assessments of disease activity. Key secondary measures included the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire, patient global assessment of pain, and the percentage of patients who achieved ACR20 responder criteria response (a composite of pain, inflammation, function, and global assessments). Tolerability was assessed by adverse events and routine laboratory evaluations.

Results

1171 patients were screened, 891 patients were randomized (N = 357 for placebo, N = 353 for etoricoxib, and N = 181 for naproxen), and 687 completed 12 weeks of treatment (N = 242 for placebo, N = 294 for etoricoxib, and N = 151 for naproxen). Compared with patients receiving placebo, patients receiving etoricoxib and naproxen showed significant improvements in all efficacy endpoints (p<0.05). Treatment responses were similar between the etoricoxib and naproxen groups for all endpoints. The percentage of patients who achieved ACR20 responder criteria response was 41% in the placebo group, 59% in the etoricoxib group, and 58% in the naproxen group. Etoricoxib and naproxen were both generally well tolerated.

Conclusions

In this study, etoricoxib 90 mg once daily was more effective than placebo and similar in efficacy to naproxen 500 mg twice daily for treating patients with RA over 12 weeks. Etoricoxib 90 mg was generally well tolerated in RA patients.

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a highly inflammatory, chronic, systemic disease which affects connective tissue and involves multiple joints. The traditional symptomatic therapy for many inflammatory diseases, including RA, has been nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs) [1,2]. In RA, NSAIDs are often used in conjunction with disease modifying antirheumatism drugs such as methotrexate, or may be taken as monotherapy for symptomatic relief [1,2]. While NSAIDs are effective in controlling the joint pain and swelling in RA, their side effect profile limits their use in some patients. In particular, the potential for gastrointestinal toxicity with traditional nonselective NSAIDs can be a significant limitation of their use [3]. Gastrointestinal bleeding, ulceration, and perforation, are the most common serious adverse events associated with NSAIDs and often lead to discontinuation of NSAID therapy as well as expensive treatment for the gastropathic symptoms themselves [4]. Continuous exposure to high doses of NSAIDs, as well as frequent concomitant use of steroids, puts RA patients at particular risk for gastrointestinal-associated adverse events [3,5].

The new generation of NSAID treatments which selectively inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) while sparing COX-1 offer an alternative treatment option for many patients with RA and other inflammatory disorders [6]. Previous studies have shown that the selective COX-2 inhibitors, rofecoxib and celecoxib, are effective and well-tolerated treatments for RA, with decreased gastrointestinal toxicity versus non-selective NSAIDs [6-8]. A recent clinical trial conducted in the United States found that the new, highly selective COX-2 inhibitor, etoricoxib (90 mg), was effective in the treatment of RA and also suggested that this dose of etoricoxib might be more effective than a 1000-mg dose of the non-selective NSAID naproxen [9]. The present study conducted at sites throughout the world further investigated the clinical profile of etoricoxib 90 mg in RA patients.

Materials and Methods

General

This randomized, double-blind, parallel-group 12-week study was conducted at 67 sites in 28 countries, including the U.S. (see acknowledgments for list of countries and investigators). Patients were enrolled between November 1999 and June 2000. Each site received the approval of its Ethics Review Committee or Institutional Review Board to perform the study. Written informed consent was obtained from every patient evaluated. Patients who discontinued the study due to lack of efficacy or who completed the 12-week, placebo-controlled trial were offered the opportunity to enter a blinded active comparator-controlled 40-week extension. The data from the 40-week, active comparator-controlled extension will be reported separately.

Patients

Eligible patients were age ≥18 years and fulfilled diagnostic criteria for RA as specified by the 1987 revised criteria of the American Rheumatism Association [10]. In addition, patients were required to have an established diagnosis of RA for at least 6 months prior to entering the study, a history of a clinical response to NSAID therapy, and to have been taking NSAID therapy on a regular basis (at least 25 of the past 30 days). Patients with a history of angina or congestive heart failure, with symptoms that occurred at rest or minimal activity, and/or who had a history of myocardial infarction, coronary angioplasty, or coronary bypass within the past year were excluded as were those with a history of stroke, transient ischemic attack or hepatitis in the previous two years. Patients with uncontrolled hypertension at screening were also excluded. Patients with any medical condition which, in the opinion of the investigator, could have confounded study results or caused undue risk to the patient (e.g., comorbid conditions for which NSAIDs are contraindicated) were also excluded. Three hemoccult screens were performed prior to allocation and patients with any evidence of active gastrointestinal bleeding were excluded. At randomization, patients could not be taking concomitant warfarin, ticlopidine, clopidrogel or digoxin. Patients on stable doses of disease modifying therapy (except TNF inhibitors) and low doses of corticosteroids (prednisone <10 mg daily) were allowed to continue therapy. Patients were permitted to take low dose aspirin (up to 100 mg/day), but in practice <3% patients used aspirin during the study.

Procedure

Patients were assessed for disease activity and those who met entry criteria were asked to discontinue their current NSAID use and return for evaluation when symptoms worsened (disease flare). At re-evaluation for study inclusion, patients were required to have ≥ 6 tender joints, ≥ 3 swollen joints, and at least a 20% increase in the number of tender and swollen joints compared with screening visit assessments. In addition, investigators must have rated patients as "fair," "poor," or "very poor" on the investigator global assessment of disease activity, and noted either of the following: 1) morning stiffness for ≥45 minutes plus increased duration of morning stiffness by at least 15 minutes since screening visit evaluation, or 2) a score of >40 mm on patient global assessment of pain (a 100-mm visual analog scale [VAS]) and at least a 10-mm increase in patient assessment of pain over that reported at screening visit evaluation.

Patients meeting the above flare criteria were randomized to placebo, etoricoxib 90 mg once daily, or naproxen 500 mg twice daily in a 2:2:1 allocation ratio. Randomization was stratified by use or non-use of low-dose corticosteroids. Efficacy evaluations were performed at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. Efficacy assessments included all components of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) core set of outcome measures: tender joint count, swollen joint count, patient global assessment of disease activity, investigator global assessment of disease activity, Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) of disability (an assessment of the patient's mobility and ability to carry out activities of daily living), patient global assessment of pain, and C-reactive protein level [2,10]. Four endpoints were specified as primary: tender joint count (total 68 joints), and swollen joint count (total 66 joints), patient global assessment of disease activity (100-mm VAS; 0 = "very well", 100 = "very poor"), investigator global assessment of disease activity (0 to 4 Likert scale; 0 = "very well", 1 = "well", 2 = "fair", 3 = "poor", 4 = "very poor"). Key secondary measures included patient global assessment of pain (100-mm VAS; 0 = "no pain", 100 = "extreme pain"), HAQ disability score (the average score of 9 disability questions, each graded on a 0 to 3 Likert scale: 0 = "without any difficulty", 1 = "with some difficulty", 2 = "with much difficulty", 3 = "unable to do"), and the proportion of patients who met the ACR20 criteria for a clinically relevant response (a composite criteria requiring 20% improvement in tender and swollen joint counts and 20% improvement in 3 of the 5 remaining ACR core measures) [10] and who completed the study (ACR20-completers). The percentage of patients who discontinued due to lack of efficacy were also measured. For completeness, we also looked at the percentage of patients meeting ACR20 criteria regardless of whether or not they completed the study.

Laboratory assessments (serum chemistry, complete blood count, urinalysis) were performed at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 12. Clinical and laboratory adverse events were recorded throughout the study. Investigators rated the intensity, relation to study drug (possibly, probably, or definitely drug-related; probably not or definitely not drug-related), and seriousness (includes events which are life threatening, result in hospitalization, or cause permanent incapacity, or other significant event) of adverse events. All potential upper gastrointestinal perforations, ulcers and bleeds (PUBs) and all potential cardiovascular thrombotic events (including cardiac, peripheral vascular and cerebrovascular events) were reviewed by independent blinded adjudication committees, who determined if they were confirmed events according to pre-specified case definitions (confirmed adjudicated events) [6].

Statistical analysis

The primary analytic method for evaluating efficacy was to compare treatment groups using the time-weighted average change from baseline across 12 weeks for the 7 ACR core measures. The rates at 12 weeks for ACR20-completers, and the cumulative rates over 12 weeks for discontinuations due to lack of efficacy were also compared between treatment groups. Pair-wise comparisons were based on the difference between mean responses, except for C-reactive protein level, where the mean ratio was analyzed via log transformation. A modified intent-to-treat approach was employed – all patients with baseline and at least 1 post-baseline measurement were included in the analysis. Analysis of covariance (including terms for baseline covariate, stratum [corticosteroid use], and treatment) was used for all efficacy variables except ACR20-completers, and discontinuation rates due to lack of efficacy. The percentages of patients meeting ACR20-completers criteria were compared between treatment groups using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test with corticosteroid use as a stratification factor, and Fisher's Exact test was used to make between-treatment comparisons of the discontinuation rates due to lack of efficacy. The analysis of serum C-reactive protein was based on the log of on-treatment value over baseline value. Plots of mean changes from baseline at each time point for the 4 primary endpoints were made to assess the maintenance of therapeutic effect for etoricoxib and naproxen. A last-observation-carried-forward method was used for these longitudinal graphs, but not for the time-weighted average changes shown in the table of results.

Tolerability was evaluated by tabulation of all clinical and laboratory safety parameters, including adverse events. Active treatments were compared with placebo using Fisher's exact test for the percentages of patients with any drug-related clinical adverse event, with any serious clinical adverse event, or who discontinued due to a clinical adverse event. Evaluations of data regarding safety were made by various means, including an examination of patients exceeding predefined limits for laboratory values of interest (e.g., consecutive decreases in hemoglobin and hematocrit, increased aminotransferase values, or increases in serum creatinine), common events associated with NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors (e.g., hypertension and lower extremity edema), and percentages of patients discontinuing due to adverse events.

Results

Patients

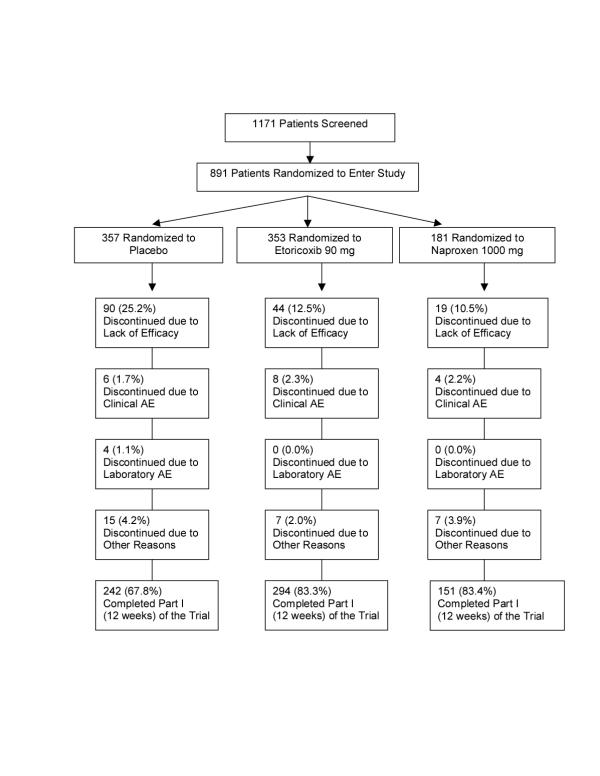

Of the 1171 patients screened, 891 met eligibility criteria and were randomized. Baseline characteristics of the 891 patients in the 3 treatment groups were similar and are shown in Table 1. A total of 687 of the 891 patients (67.8% of the placebo group, 83.3% of the etoricoxib group, and 83.4% of the naproxen group) completed the 12-week study (Figure 1). The mean number of days patients were on treatment was 65.5 for placebo, 76.0 for etoricoxib, and 76.5 for naproxen. The most common reason for discontinuation was lack of efficacy, and significantly more patients discontinued due to lack of efficacy in the placebo group than in the etoricoxib and naproxen group (25.2%, 12.5%, 10.5%, respectively, p<0.001 vs placebo). The results of all patients who had at least one post-randomization efficacy measurement were included in the primary analysis of efficacy (93.0% in the placebo group, 97.5% in the etoricoxib group and 96.1% in the naproxen group).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Placebo | Etoricoxib 90 mg | Naproxen 1000 mg |

| (N = 357) | (N = 353) | (N = 181) | |

| % women | 82 | 81 | 82 |

| Mean age [yrs] (SD) | 52 (12) | 53 (12) | 52 (12) |

| Mean duration of rheumatoid arthritis [yrs] (SD) | 9 (8) | 8 (8) | 8 (8) |

| % rheumatoid factor-positive | 83 | 85 | 87 |

| % in ARA functional class: | |||

| I | 27 | 31 | 27 |

| II | 56 | 53 | 58 |

| III | 17 | 16 | 16 |

| % taking rheumatoid arthritis medications: | |||

| Corticosteroids | 57 | 54 | 59 |

| Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs | 83 | 83 | 81 |

| Methotrexate | 59 | 55 | 62 |

| Mean patient global assessment of disease activity (100 mm visual analog scale) ‡ (SD) | 65 (19) | 66 (20) | 65 (19) |

| Mean investigator global assessment of disease activity (0 to 4 scale) ‡ (SD) | 2.7 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.6) |

| Mean number of tender joints (of 68) ‡ (SD) | 29 (15) | 29 (15) | 28 (15) |

| Mean number of swollen joints (of 66) ‡ (SD) | 19 (12) | 19 (13) | 18 (12) |

‡ Higher score corresponds to greater disease activity.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. AE = adverse event. "Discontinued due to other reasons" = patient lost to follow-up, moved, withdrew consent, protocol deviation, study site terminated.

Efficacy

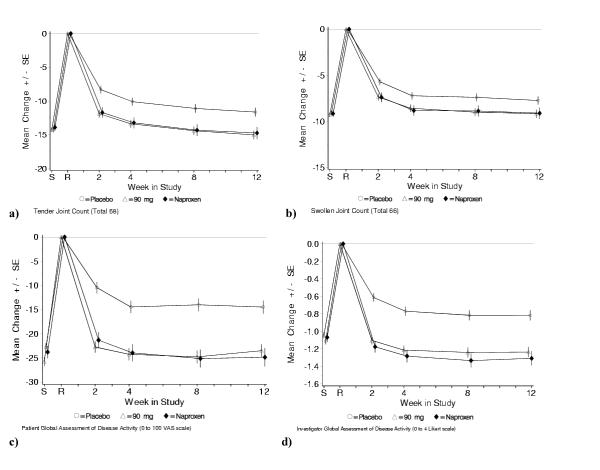

Table 2 summarizes the results of the treatment comparisons for the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints. For all 4 primary endpoints, etoricoxib and naproxen were statistically superior to placebo. For all secondary endpoints, except serum C-reactive protein, both etoricoxib and naproxen were also superior to placebo. Serum C-reactive protein levels increased on etoricoxib compared to placebo. This was not seen in the naproxen group. There was no significant difference between etoricoxib and naproxen for any of the primary or secondary endpoints. The percentage of patients who achieved ACR20 responder criteria response was 40.9% in the placebo group, 58.7% in the etoricoxib group, and 57.5% in the naproxen group. Treatment effects of etoricoxib were rapid, occurring at the earliest time point measured (week 2), and were maintained over the entire 12-week study period (Figures 2a,2b,2c,2d). Treatment effects of etoricoxib were consistent across corticosteroid users and non-users.

Table 2.

Mean (95% confidence interval) efficacy differences between treatments over 12 weeks

| Etoricoxib vs placebo | Naproxen vs placebo | Etoricoxib vs naproxen | |

| Primary endpoints | |||

| Patient global assessment of disease activity (100 mmVAS) ‡ | -9.93* (-12.96, | -10.0* (-13.7, | 0.09 (-3.61, 3.79) |

| -6.90) | -6.32) | ||

| Investigator global assessment of disease activity (0–4 scale) ‡ | -0.43* (-0.55, | -0.51* (-0.66, | 0.08 (-0.08, 0.24) |

| -0.30) | -0.35) | ||

| Tender joint count (total 68 joints) ‡ | -3.42* (-4.89, | -3.16* (-4.96, | -0.26 (-2.05, 1.54) |

| -1.94) | -1.36) | ||

| Swollen joint count (total 66 joints) ‡ | -1.43† (-2.42, | -1.39† (-2.60, | -0.03 (-1.24, 1.17) |

| -0.44) | -0.19) | ||

| Secondary endpoints | |||

| Patient global assessment of pain (100 mm VAS) ‡ | -9.62* (-12.73, | -10.46* (-14.25, | 0.84 (-2.96, 4.63) |

| -6.51) | -6.66) | ||

| Health Assessment Questionnaire disability (0–3 scale) ‡ | -0.20* (-0.28, | -0.29* (-0.38, | 0.08 (0.00, 0.17) |

| -0.13) | -0.20) | ||

| Serum C-reactive protein (ratio between treatments) | 1.11† (1.00, 1.23) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.13) | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) |

| ACR20 responder criteria (%) | 17.83* (10.55, 25.12) | 16.68* (7.80, 25.57) | 1.15 (-7.74, 10.03) |

| Discontinuation due to lack of efficacy (%) | -12.75* (-18.42, | -14.71* (-21.06, | 1.97 (-3.67, 7.61) |

| -7.07) | -8.37) |

Note: Negative values indicate improvement except for ACR20 responder criteria and serum C-reactive protein.

* The difference vs placebo was significant (p<0.001). † The difference vs placebo was significant (p<0.05). ‡ For these measures, the difference shown is for the least squares mean of the time-weighted average change from baseline over 12 weeks. ACR20 responder criteria and Discontinuations due to lack of efficacy are shown as differences in frequency over the 12-week period. Serum C-reactive protein was calculated as a ratio between treatments over the 12-week treatment period.

Figure 2.

Changes from baseline on primary endpoints: a) tender joint counts; b) swollen joint counts; c) patient global assessments of disease activity; d) investigator global assessments of disease activity. S = screening visit, R = randomization (baseline) visit; SE = standard error. Screening (S) to randomization (R) = washout period for prior NSAID therapy. Empty circle = placebo, empty triangle = etoricoxib 90 mg, solid diamond = naproxen 1000 mg. A last-observation-carried-forward approach was used for missing values.

Tolerability

The adverse event rates for the 3 treatment groups are summarized in Table 3. Clinical adverse events determined by the investigator as possibly, probably, or definitely drug-related occurred in 15.4%, 23.2%, and 19.3% of patients in the placebo, etoricoxib 90 mg, and naproxen 500 mg twice daily groups (p<0.05 for etoricoxib versus placebo). There was no individual drug-related adverse event that was predominantly responsible for the difference between etoricoxib and placebo; in fact, there were no individual drug-related adverse events with an incidence ≥4% in any treatment group. The active treatments were not significantly different from placebo (p>0.05) with regard to the percentages of patients with any serious clinical adverse event or who discontinued due to a clinical adverse event (Table 3). Only 3 of the serious clinical adverse events were judged to be drug-related by the investigators: 2 on etoricoxib (duodenal ulcer and hip pain) and 1 on naproxen (hypertension). There were no deaths reported. No clinically relevant trends were noted in the overall incidence of laboratory adverse events or mean changes in alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, serum creatinine, and hemoglobin plus hematocrit.

Table 3.

Summary of safety data

| Placebo | Etoricoxib 90 mg | Naproxen 1000 mg | |

| (N = 357) | (N = 353) | (N = 181) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Number of patients: | |||

| With any drug-related clinical adverse event | 55 (15.4) | 82 (23.2) † | 35 (19.3) |

| With any serious clinical adverse event‡ | 3 (0.8) | 7 (2.0) | 3 (1.7) |

| Discontinued due to clinical adverse event | 6 (1.7) | 9 (2.5) | 5 (2.8) |

† p < 0.05 vs placebo.

‡ Serious adverse events were: placebo (3 patients) – thrombophlebitis, atrial fibrillation, and pneumothorax; etoricoxib (7 patients) – pulmonary embolism, angina pectoris, thyroid cancer, duodenal ulcer, hip pain, femoral fracture, and traumatic arthropathy plus corneal degeneration (in the same patient); naproxen (3 patients) – hypertension, intervertebral disc displacement, and retinal detachment.

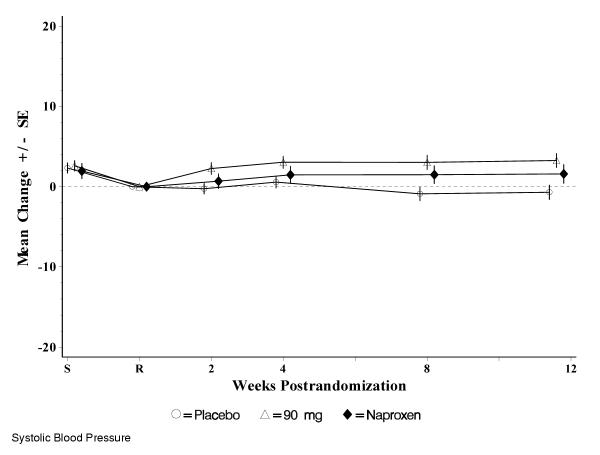

The most commonly reported adverse events, those with an incidence of ≥3% in any treatment group, are summarized in Table 4. Events of special interest in evaluating COX inhibitors are also summarized in Table 4. The incidence of gastrointestinal nuisance symptoms was similar among all treatment groups (10.1%, 10.8%, and 11.6% in the placebo, etoricoxib and naproxen groups, respectively). The incidence of lower extremity edema adverse events in the study was low and similar among treatment groups. No patients discontinued due to lower extremity edema. Although there was an increase in hypertension adverse events in patients taking etoricoxib and naproxen versus placebo, discontinuations due to hypertension adverse events were rare (1 patient on naproxen). Over 12 weeks, mean systolic blood pressures decreased slightly from baseline in the placebo group, and increased slightly in the etoricoxib and naproxen groups (the maximum difference between means at any time point was <3.5 mm Hg for etoricoxib and <2 mm Hg for naproxen) (Figure 3). Mean diastolic blood pressures did not change substantially from baseline values in any treatment group during the study (the maximum difference at any time point was ≤1.1 mm Hg). There was only 1 confirmed duodenal ulcer in the study (in the etoricoxib treatment group). There were 3 confirmed cardiovascular thrombotic adverse events: 2 on etoricoxib (angina pectoris and pulmonary embolism) and 1 on placebo (thrombophlebitis).

Table 4.

Most common adverse events and events of interest in evaluating COX-inhibitors

| Placebo | Etoricoxib 90 mg | Naproxen 1000 mg | |

| (N = 357) | (N = 353) | (N = 181) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Most Common Adverse Events† | |||

| Headache | 20 (5.6) | 24 (6.8) | 6 (3.3) |

| Hypertension | 5 (1.4) | 12 (3.4) | 5 (2.8) |

| Upper Respiratory Infection | 11 (3.1) | 8 (2.3) | 8 (4.4) |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 16 (4.5) | 15 (4.2) | 8 (4.4) |

| Events of Interest in Evaluating COX Inhibitors | |||

| Gastrointestinal (GI) Adverse Events | |||

| GI Nuisance Symptoms‡ | 36 (10.1) | 38 (10.8) | 21 (11.6) |

| Discontinuations | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Renovascular Adverse Events | |||

| Lower Extremity Edema (LEE) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) |

| Discontinuations due to LEE | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hypertension | 5 (1.4) | 12 (3.4) | 5 (2.8) |

| Discontinuations due to hypertension | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

† Incidence ≥ 3% in any treatment group.

‡ Includes abdominal pain, acid reflux, dyspepsia, epigastric discomfort, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting.

Figure 3.

Mean changes from baseline in systolic blood pressure (mm Hg). S = screening visit, R = randomization (baseline) visit; SE = standard error. Screening (S) to randomization (R) = washout period for prior NSAID therapy. Empty circle = placebo, empty triangle = etoricoxib 90 mg, solid diamond = naproxen 1000 mg.

Discussion

This multinational study confirmed findings from a replicate study [9] that a 90-mg daily dose of the COX-2 selective inhibitor, etoricoxib, was more effective than placebo for treating patients with RA. The treatment effects of etoricoxib occurred by the first assessment (at 2 weeks) and were sustained throughout the 12 weeks of the study.

Etoricoxib showed similar efficacy to a high dose of the non-selective NSAID naproxen, supporting results from studies with other selective COX-2 inhibitors in RA which also showed similar efficacy to non-selective NSAIDs [7,8]. The results differed from those in the replicate study of etoricoxib in RA [9] which found that etoricoxib was more effective than naproxen. The reason for the difference in results between the two studies is unclear since the studies had identical designs, including entry criteria, doses of study medication, and outcome measures. However, although patient enrollment criteria were identical, more patients in the present study were using concomitant corticosteroids (approximately 57% versus 32%) and disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, including methotrexate (approximately 82% versus 68%). It is conceivable that the increased concomitant RA medication use may have obscured the ability to detect small, but perhaps meaningful differences between active treatments. Interestingly, in this study as compared to the replicate etoricoxib RA study [9], the placebo response rate was higher (ACR20-responders were 40.9% in the current study versus 20.8% in the replicate study) and the discontinuations due to lack of efficacy were lower in the placebo group (25.2% in the current study vs 54.5% in the replicate study), and this may also have influenced the results. Although unproven, other potential explanations may relate to the fact that the present study was conducted largely outside the United States and the previous study inside the United States [9]. Therefore, differences in underlying disease characteristics and/or cultural differences in perceptions of efficacy may have also contributed to the difference in the results. Others have reported different findings for RA studies with similar designs which were conducted in the United States versus other countries. Serum C-reactive protein levels were noted to be elevated compared to placebo in the etoricoxib group. This was not observed in other etoricoxib RA studies [19,9]; in one study no difference was seen from placebo [19], and in the other study a lowering in serum C-reactive protein was observed [9]. It is generally not believed that changes in serum C-reactive protein are substantially influenced by NSAID treatment. Therefore, this was not felt to represent a clinically meaningful finding.

Etoricoxib was generally well tolerated by the patients in this study, consistent with results from prior clinical trials of etoricoxib for RA and other indications [9,11-13]. There was a significantly higher number of patients with drug-related clinical adverse events for etoricoxib versus placebo. However, the difference was small and should be interpreted with caution since more patients on placebo discontinued early (primarily due to lack of efficacy) and therefore had less chance of experiencing an adverse event. The findings may therefore overestimate adverse event rates for the active treatments compared with placebo.

Particular attention was paid to the typical NSAID-related renal effects of edema and hypertension since data with both selective COX-2 inhibitors and non-selective NSAIDs have suggested that they have an effect on renal physiology [14,15]. Etoricoxib and naproxen showed a small increase in hypertension adverse events compared with placebo. Mean changes in blood pressure among the treatment groups was small, and both etoricoxib and naproxen treatment groups showed only small increases in mean systolic blood pressure compared to baseline. Among patients who had hypertension adverse events on etoricoxib, no patient discontinued from the study. The incidences of lower extremity edema adverse events for etoricoxib were similar to placebo and no patient treated with etoricoxib discontinued as a result.

The main proposed advantage for selective COX-2 inhibitors is reduced gastrointestinal toxicity. However, a thorough and adequate assessment of this can only be made either in very large long-term trials or pooled analyses because of the relatively low incidence of clinically significant gastrointestinal PUBs [6,16]. In fact, only one confirmed PUB was reported in the present study.

It has also been suggested [6,17,18] that the use of selective COX-2 agents may be associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular thrombotic events than naproxen (a potent and sustained inhibitor of platelet aggregation at therapeutic doses). As with upper GI clinical events (PUBs), these events are rare and conclusive data can only be adequately amassed in large data sets. The incidence of confirmed cardiovascular thrombotic events in the present study was low (3 events), therefore no meaningful conclusions about the overall cardiovascular safety of etoricoxib can be determined from this single study.

Conclusions

In summary, etoricoxib 90 mg once daily provided clinically meaningful improvements of the signs and symptoms of RA that were superior to those of placebo and comparable to those of naproxen 500 mg twice daily. Etoricoxib 90 mg was generally well tolerated in this study. These data provide further support for the addition of etoricoxib to the available therapeutic options in the management of RA patients.

Competing interests

SP Curtis, A Melian, PL Zhao, DB Rodgers, CL McCormick, M Lee, CR Lines, and BJ Gertz are employees of Merck & Co., Inc. and have held Merck stocks or shares. E Collantes, KW Lee, N Casas, and T McCarthy have received funding from the following pharmaceutical companies to perform studies, act as a consultant, or be a speaker at company-sponsored symposia: E Collantes (Merck, Novartis, Lilly, Roche, Aventis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca), KW Lee (Merck, Aventis), N Casas (Merck), T McCarthy (Merck, Pharmacia, Novartis, Immunex, Isotechnika, Janssen-Ortho, AstraZeneca, Knoll and Abbott).

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Primary investigators in the Etoricoxib Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group were: T Adamson (USA), S Aslanidis (Greece), A Badilla (Costa Rica), C Barfield (USA), A Beaulieu (Canada), M Bell (Canada), M Berliner (Germany), TA Bermudez (Spain), L Bidula (USA), K Boki (Greece), H Broell (Austria), A Cabral (Mexico), J Calvo Catala (Spain), N Casas (Colombia), D Ching (New Zealand), C Codreanu (Romania), B Colaco (UK), E Collantes (Spain), B Combe (France), J. Forstot (USA), S Garcia Perez (Spain), E George (UK), C Glave (Peru), J Granados (Spain), M Gutierrez (USA), P Hanrahan (Australia), F Hasler (Switzerland), J Higashida (USA), G Ho (USA), P Howard (USA), JA Jover Jover (Spain), J Kalden (Germany), T Karger (Germany), J Karsh (Canada), J Kekow (Germany), DR Koh (Singapore), M Kohen (USA), M Kos-Golja (Slovenia), KW Lee (Hong Kong), H Marker (USA), M Martinez-Lavin (Mexico), A Mathieu (Italy), T McCarthy (Canada), L McLean (New Zealand), F Mielke (Germany), J Molina (Colombia), M Nahir (Israel), G Nesher (Israel), JM Padrino Martinez (Spain), M Peshimam (USA), A Posada (Venezuela), R Rau (Germany), O Rillo (Argentina), C Rojas (Chile), P Sandall (USA), B Snyder (USA), H Sorensen (Germany), B Souza (Brazil), M Tikly (South Africa), JC Torres Alonso (Spain), O Troum (USA), J Udell (USA), G Valentini (Italy), E VanDuuren (South Africa), P Vecchio (Australia), A Venalis (Lithuania), CA Von Muhlen (Brazil), M Yaron (Israel), H Yazici (Turkey), F Zaidi (USA)

Contributor Information

Eduardo Collantes, Email: ecollantes@ctv.es.

Sean P Curtis, Email: sean_curtis@merck.com.

Ka Wing Lee, Email: gavinlee@netvigator.com.

Noemi Casas, Email: ncasas@multi.net.co.

Timothy McCarthy, Email: timmccarthy@attglobal.net.

Agustin Melian, Email: agustin_melian@merck.com.

Peng L Zhao, Email: peng_zhao@merck.com.

Diana B Rodgers, Email: diana_rodgers@merck.com.

Calogera L McCormick, Email: calogera_mccormick@merck.com.

Michael Lee, Email: michael_lee@merck.com.

Christopher R Lines, Email: christopher_lines@merck.com.

Barry J Gertz, Email: barry_gertz@merck.com.

the Etoricoxib Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group, Email: sean_curtis@merck.com.

References

- American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on clinical guidelines Guidelines for monitoring drug therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on clinical guidelines Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:713–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1888–1899. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906173402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries JF, Williams CA, Bloch DA, Michel BA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastropathy: incidence and risk factor models. Am J Med. 1991;91:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90118-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riel PLCM, Wijnands MJH, van de Putte LBA. Evaluation and management of active inflammatory disease. In: Klippel JH, Dieppe PA, Arnett FC, editor. Rheumatology. 2nd. London: Mosby; 1998. pp. 14.1–14.2. [Google Scholar]

- Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. New Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer TJ, Truitt K, Fleischmann R, et al. The safety profile, tolerability, and effective dose range of rofecoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Therapeutics. 1999;21:1688–1702. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery P, Zeidler H, Kvien KT, et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac in long-term management of rheumatoid arthritis: randomized double-blind comparison. Lancet. 1999;354:2106–2111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A, Melian A, Mandel DR, et al. A randomized, controlled, clinical trial of etoricoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatology. 2002. [PubMed]

- Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:727–735. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom K, Shahane A, Fricke JR, Ehrich E. MK –0663–an investigational COX-2 inhibitor: the effect in acute pain using the dental-impaction model. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:S299 [Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- Gottesdiener K, Schnitzer T, Fisher C, et al. MK-663, a specific COX-2 inhibitor for treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:S144 [Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- Gottesdiener K, Schnitzer T, Fisher C, et al. Treatment with MK-663, a specific COX-2 inhibitor, resulted in clinical improvement in osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee that was sustained over three months. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:133 [Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- Brater DC, Harris C, Redfern JS, Gertz BJ. Renal effects of COX-2-selective inhibitors. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000046212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MD, Brater DC. Renal toxicity of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;32:435–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langman MJ, Jensen DM, Watson DJ, et al. Adverse upper gastrointestinal effects of rofecoxib compared with NSAIDs. JAMA. 1999;282:1929–1933. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.20.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catella-Lawson F, Crofford LJ. Cyclooxygenase inhibition and thrombogenicity. Am J Med. 2001;110:28S–32S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective cox-2 inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286:954–959. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis SP, Maldonado-Cocco J, Lozada B, et al. Characterization of the clinically effective dose range of MK-0663, a COX-2 selective inhibitor, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:S226 [Abstract]. [Google Scholar]