Abstract

Objectives

Basilar artery atherosclerotic plaque is the predominant cause of stroke in the posterior circulation. İscheamic stroke caused basilar artery atherosclerosis faces a high risk of recurrence despite optimal medical treatment, which might lie in the less than ideal recognition of underlying stroke mechanism and lack of individualized treatment for strokes of different mechanisms. We aim in this study to investigate the effect on stroke mechanism, stroke recurrence and clinical outcome in stroke patients with basilar artery atherosclerosis.

Methods

In this study, 107 ischaemic stroke patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the BA who were followed up in Uludag University Faculty of Medicine between 1 January 2019 and 1 January 2022. The study was conducted retrospectively and observationally.

Results

According to the results of our study, the degree of stenosis in atherosclerotic stenosis of the symptomatic basilar artery was found to be an independent risk factor for stroke recurrence. Independent risk factors for unfavourable clinical outcomes in these patients were determined as female gender, stenosis being in the proximal segment, stroke mechanism being from artery to artery embolism, and congestive heart failure.

Conclusion

The most striking result of our study is that clinical outcome was found to be closely related to the female gender, the stroke mechanism being artery-to-artery embolism, and the stenosis is in the proximal segment. If stroke mechanisms were evaluated more clearly, it would likely help provide individualised treatments.

Keywords: Intracranial atherosclerotic disease, basilar artery infarction, basilar artery stenting, acute ischaemic stroke

Introduction

Posterior circulation stroke affects the vertebrobasilar artery system and constitutes 20%–25% of all ischaemic stroke (IS) cases. 1 Basilar artery atherosclerotic plaque is the predominant cause of stroke in the posterior circulation.2,3 The basilar artery (BA) is the major artery of the posterior circulation and provides the main blood supply to this vascular region. 4 The incidence of BA occlusion is not known exactly, but it is estimated to account for 1% of all stroke cases. 5 Although atherosclerotic disease of the BA is rare, it is characterised by high mortality and stroke recurrence. 6 Atherosclerotic disease of the BA can have varied presentations and is asymptomatic in some patients. The clinical spectrum in symptomatic patients includes heterogeneous features that can range from minor deficits to coma and death.7,8 New endovascular treatment options, which are increasingly available, have expanded the treatment options for these patients. On the basis of the data from the Stenting versus Aggressive Medical Therapy for Intracranial Arterial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial, BA stenting is recommended for patients with symptomatic high-grade intracranial atherosclerosis after clinical recurrence despite the best medical treatment.9,10 However, even under the best medical treatment, the risk of recurrent IS due to intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis remains high.11,12 IS is a heterogeneous group of diseases precipitated by many complicated mechanisms. 13 We aim in this study to investigate the effect on stroke mechanism, stroke recurrence and clinical outcome in stroke patients with basilar artery atherosclerosis.

Materials and methods

Data collection

In this study, 107 IS patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the BA who were followed up in Uludag University Faculty of Medicine between 1 January 2019 and 1 January 2022. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Bursa Uludag University, Faculty of Medicine approved the study (26 September 2023; 2023-18/24). The need for informed consent was waived by The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Bursa Uludag University, Faculty of Medicine. This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the study were determined as the patient diagnosed with an acute ischemic stroke, the patient having a brain neck CT angiography, and the patient having regular follow-ups in the stroke clinic after discharge. The exclusion criteria from the study were determined as the stroke aetiology not being determined, the presence of occlusion in the basilar artery, the presence of non-atherosclerotic stenosis in the basilar artery (moya moya, dissection), the presence of more than 50% stenosis in the vertebral artery or the posterior cerebral artery.

Clinical examination

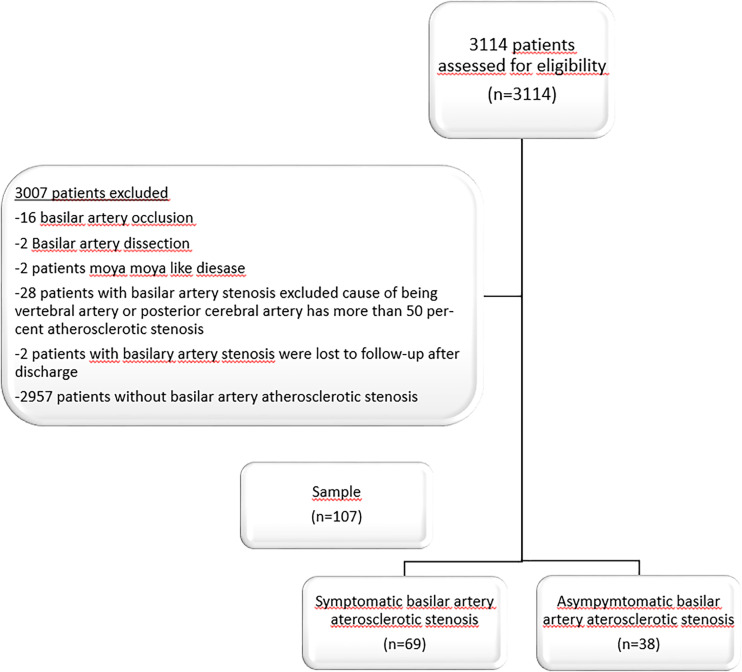

Between 1 January 2019 and 1 January 2022, 3114 patients were followed up with acute IS in Uludag University Medical Hospital, and 107 patients were included in the study according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). All patients diagnosed with IS in the emergency department were admitted to the neurology service for further examination and treatment. All patients underwent brain and neck computed tomographic (CT) angiography, cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), transthoracic echocardiography, and 24-hour rhythm Holter monitoring. In the epicrisis, their medical histories were recorded, including previous diseases, smoking habits, coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure, hypertension (HT), and diabetes mellitus (DM). The patients’ hemogram, biochemistry results, low-density-lipoprotein (mg/dL), (LDL) levels, and HbA1c (%) values were evaluated during their hospitalisation in the neurology ward. During clinical follow-up, the aim was to keep the LDL level < 100 mg/dL and medical treatment was started for all the patients. The patients with HbA1c levels > 7% were evaluated on the basis of endocrinology findings, and HbA1c and LDL values were checked every 3 months. We have followed relevant EQUATOR guidelines. 14

Figure 1.

The flowchart shows stroke patients included in the study.

Radiological examination

The patients’ brain and neck CT angiograms were evaluated by a radiologist (BH) with 23 years of neuroradiology experience who was blinded to the clinical findings. The degree of stenosis was determined using the NASCET method. The posterior cerebral collateral score was determined by evaluating the posterior communicating arteries (PCOMs). All patients were evaluated for the presence and diameter of both PCOMs, according to the following scores: dominant PCOM, two points; hypoplastic PCOM, one point; and no PCOMs, zero points. The total scores ranged from 0 to 4. Scores from 0 to 1 were considered poor collateral scores, and scores from 2 to 4 were good collateral scores. 6

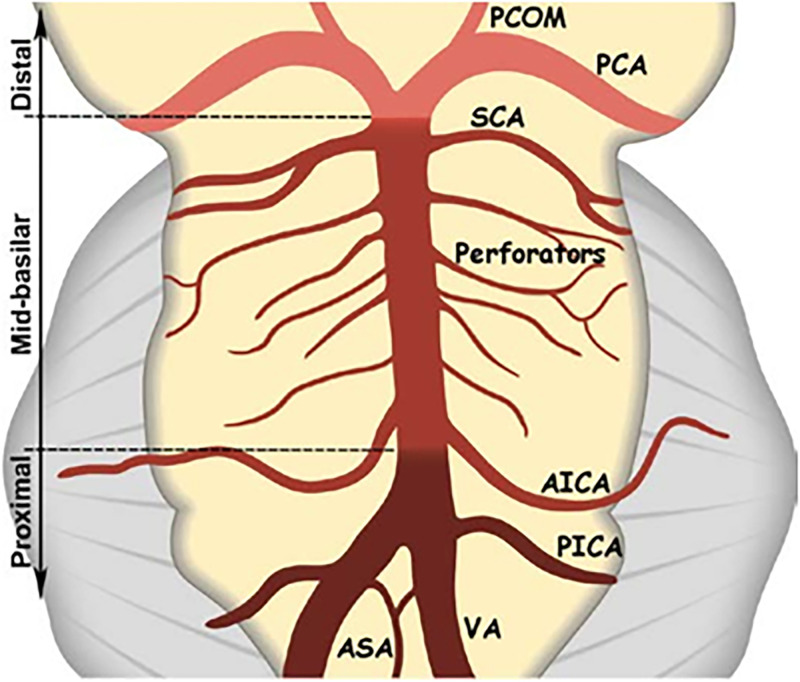

The patients’ stroke aetiologies were determined using the TOAST (trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment) classification. 15 A BA stenosis causing an IS was considered symptomatic. Whether the BA was symptomatic or not was decided by a stroke neurologist. The BA was evaluated in three segments: proximal, middle, and distal (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Basilar artery segments: proximal from the vertebrobasilar junction to the origin of the AICA, mid from the AICA to the origin of the SCA, and distal after the origin of the SCA. AICA: anteroinferior cerebellar artery; ASA: anterior spinal artery; PCA: posterior cerebral artery; PCOM: posterior communicating artery; PICA: posteroinferior cerebellar artery; SCA: superior cerebellar artery; VA: vertebral artery (figure adapted Samaniego EA, Shaban A, Ortega-Gutierrez S et al. Stroke mechanisms and outcomes of isolated symptomatic basilar artery stenosis. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2019; 4:189–197.)

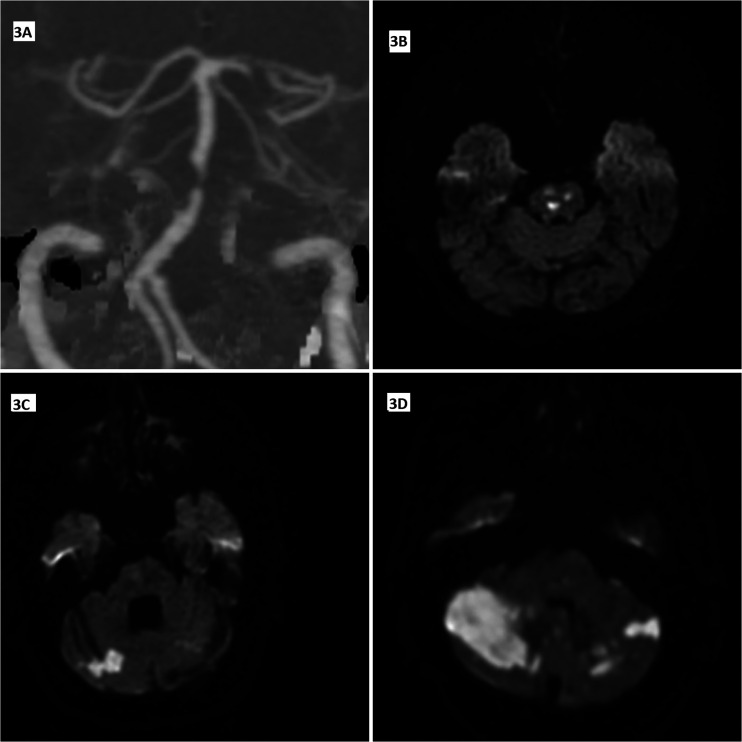

The stroke mechanisms were evaluated by dividing them into four types: artery-to-artery embolism, perforatory stroke, haemodynamic stroke, and IS due to BA occlusion (Figure 3). 16 In the third month, the patients’ clinical outcomes were determined using the modified Rankin scale (0–2, favourable outcomes and 3–6, unfavourable clinical outcomes). All the patients underwent regular checkups at the neurology outpatient clinic, where any stroke recurrence was recorded. The patients were followed in accordance with the American Heart Association guidelines. BA stenting was performed in patients with recurrent IS who were undergoing aggressive medical treatment.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) maximum intensity projection image (3A) from a patient with pre-occlusive stenosis in the basilar artery, DWI images from different patients (3B–D); multiple acute lacunes in pons due to perforating artery ischemia (3B); acute hemodynamic infarcts in the right cerebellar hemisphere and late subacute hemodynamic infarcts in the left cerebellar hemisphere (3C), scattered infarcts developed due to the artery-artery embolic process in both cerebellar hemispheres (3D).

Statistical analysis

The patients with atherosclerotic stenosis of the BA were categorised as either symptomatic or non-symptomatic. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to determine the cut-off value of the degree of stenosis. The patients with symptomatic BA stenosis were then categorised according to whether they had stroke recurrence or not and their clinical outcomes.

The clinical properties of the patients in both groups were analysed and compared. A statistical analysis was implemented using the IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normality of the data distribution. Mean ± SD values were determined for the normally distributed variables, and median (Q1–Q3) values were determined for the non-normally distributed variables. An independent sample T-test was performed to analyse the normally distributed variables between the two independent groups, and the Whitney U-test was performed for the non-normally distributed variables.

Frequencies and percentages were determined for the categorical variables. The Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test was performed to analyse the categorical variables for comparison between the groups. The binary logistic regression model included the variables found to be significant in the univariate analyses. We choose p < 0.05 as a significant level.

Posterior power analysis was performed. One of the most important variables is the stroke mechanism, which is artery-to-artery embolism. The artery-to-artery embolism rate is 60% in the group with proximal basilar artery stenosis and 25.64% in the group with mi-basilar artery stenosis. For the sample size of our study (n = 107) to determine a 34% difference between the two groups, the determined power is 88%.

Results

A total of 3114 patients with acute IS were followed up between January 2019 and January 2022 at the Department of Neurology of the Uludag University Faculty of Medicine. A total of 107 patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the BA who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Of these patients, 39 were female, and 68 were male. The mean age was 67.98 ± 9.33 years for all the patients, 67.08 ± 9.51 years for the male patients, and 69.53 ± 8.90 years for the female patients, indicating statistically similar mean ages between the male and female patients (p > 0.05). When the patients’ risk factors were evaluated, 88 patients had HT, 64 had diabetes mellitus (DM), 59 were smokers, 31 had congestive heart failure, 45 had CAD, and 15 had atrial fibrillation (AF).

According to stroke aetiology, 77 patients had an IS due to large artery atherosclerosis, 15 had an IS due to cardioembolism, eight had an IS due to small vessel disease, one had an IS due to other causes, and six had an IS due to undetermined causes. Basilar artery occlusion was one of the exclusion criteria in our study at the beginning. However, we reported the patients who developed basilar artery occlusion during our clinical follow-up in patients with basilar artery stenosis in our study. Basilar artery occlusion occurred in nine patients during clinical follow-up.

When the location of the BA stenosis was examined, atherosclerotic stenosis was detected in the proximal basilar segment in 56 patients, in the mid-basilar segment in 59, and in the distal basilar segment in six. The BA atherosclerotic stenosis was multi-segmented in 13 patients and symptomatic in 69 patients. BA stenting was performed in 29 patients.

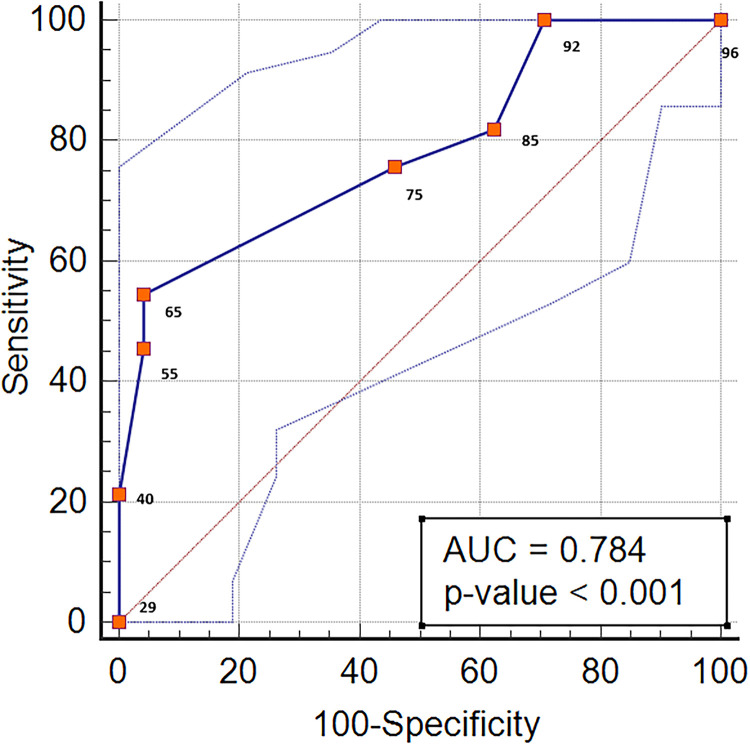

As shown in Table 1, the BA atherosclerotic stenosis was symptomatic in 32 of the 56 patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the proximal segment of the BA. A ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the level of stenosis in the patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the proximal BA and to differentiate the symptomatic and non-symptomatic patients. The area under the ROC was 0.784 (p < 0.001). The cut-off value of the degree of stenosis was > 70%, and the sensitivity and specificity corresponding to this cut-off value were 54.55% and 95.83%, respectively (Figure 4). Of the patients with symptomatic proximal BA atherosclerosis, 24 had an unfavourable clinical outcome, and eight had a favourable clinical outcome. IS recurrence was observed in 15 patients with symptomatic proximal artery stenosis. When the stroke mechanisms were evaluated, artery-to-artery embolism occurred in 19 patients; penetrating artery infarction, in 18; haemodynamic stroke, in six; and BA occlusion, in four. The stroke in 13 patients occurred with a mixed mechanism.

Table 1.

Clinical properties of proximal and mid-basilar artery stenosis.

| Properties | Symptomatic proximal basilar artery stenosis (n = 56) | Symptomatic mid-basilar stenosis (n = 59) |

|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic basilar artery stenosis | 32 (57.14%) | 42 (71.18%) |

| Stroke recurrence due to basilary artery stenosis | 15 (26.78%) | 15 (25.42%) |

| Stroke mechanism | ||

| artery-to-artery embolism due to basilary artery stenosis | 19 (33.92%) | 15 (25.42%) |

| Perforator stroke due to basilary artery stenosis | 18 (32.14%) | 31 (52.54%) |

| Hemodynamic stoke due to basilary artery stenosis | 6 (10.71%) | 7 (11.86%) |

| Stroke due to basilar artery occlusion | 4 (7.14%) | 5 (8.47%) |

| Mix mechanism | 13 (23.21%) | 15 (25.42%) |

| Favourable clinical outcome | 8 (14.28%) | 30 (50.84%) |

| Unfavourable clinical outcome | 24 (42.85%) | 12 (20.33%) |

| Follow-up perıod of patıents (month) |

23.50 ±17.63 | 29.93 ±17.78 |

Figure 4.

Area under the ROC curves (AUC) for the relationship between the degree of stenosis and symptomatology of proximal basilar artery stenosis.

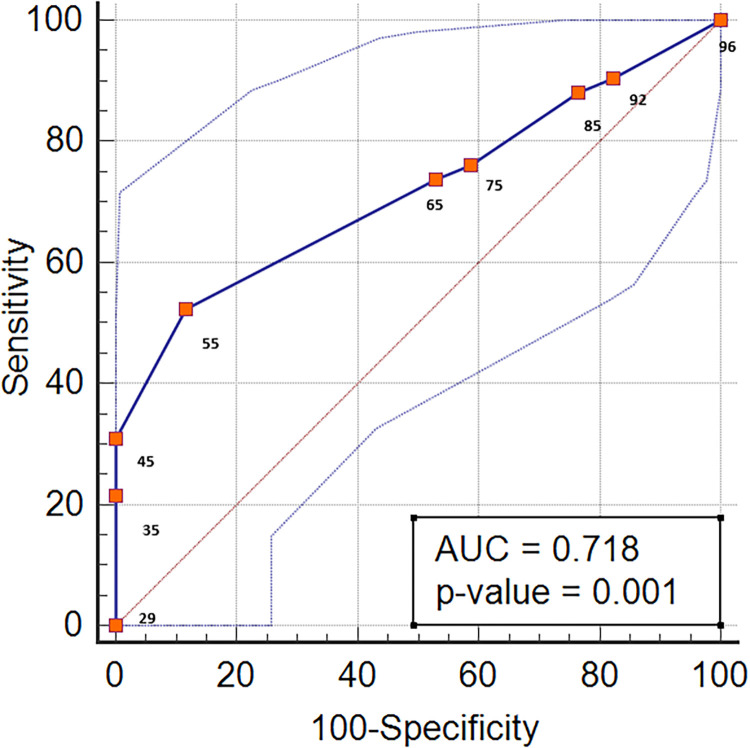

The BA atherosclerotic stenosis was symptomatic in 42 of the 59 patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the mid-basilar segment. A ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the level of stenosis in the patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the mid-basilar segment and to differentiate between the symptomatic and non-symptomatic patients. The area under the ROC was 0.718 (p < 0.001). The cut-off value of the degree of stenosis was > 70%, and the sensitivity and specificity corresponding to this cut-off value were 52.38% and 88.24%, respectively (Figure 5). Of the patients with symptomatic mid-basilar atherosclerosis, 30 had a favourable clinical outcome, and 12 had an unfavourable clinical outcome. IS recurrence was observed in 15 patients with symptomatic mid-basilary stenosis. When the stroke mechanisms were evaluated, artery-to-artery embolism occurred in 15 patients; IS due to penetrating artery infarction, in 31; IS with a mixed mechanism, in seven; and BA occlusion, in five. IS occurred with a mixed mechanism in 15 patients.

Figure 5.

Area under the ROC curves (AUC) for the relationship between the degree of stenosis and symptomatology of mid-basilar artery stenosis.

When the demographic, clinical, and radiological properties of the IS patients with symptomatic BA stenosis and stroke recurrence were examined, the significant variables were artery-to-artery embolism (p = 0.027), BA occlusion (p < 0.001), or a mixed mechanism as the stroke mechanism (p < 0.001); haemoglobin level (p = 0.030); and degree of stenosis (p < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation of variables affecting stroke recurrence in acute ischemic stroke patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the symptomatic basilar artery.

| Variables | Ischemic stroke due to symptomatic basilar artery atherosclerotic stenosis with stroke recurrence (n = 30) | Ischemic stroke due to symptomatic basilar artery atherosclerotic stenosis without stroke recurrence (n = 39) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 66.50±7.97 | 67.64±10.15 | 0.614 |

| Sex** (male gender) | 19 (63.33%) | 19 (48.71%) | 0.226 |

| Diabetes** | 19 (63.33%) | 26 (66.66%) | 0.773 |

| Hypertension** | 26 (86.66%) | 31 (79.48%) | 0.435 |

| Smoker** | 16 (53.33%) | 20 (51.28%) | 0.886 |

| Atrial fibrillation** | 16 (53.33%) | 20 (51.28%) | 0.646 |

| Congestive heart failure** | 4 (13.33%) | 10 (25.64%) | 0.208 |

| Coroner artery disease** | 10 (33.33%) | 15 (38.46%) | 0.660 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL)* | 13.25 (11.85, 14.00) | 13.80 (12.58, 14.70) | 0.030 |

| LDL (mg/dL)* | 151.50 (100.00, 185.00) | 138.50 (112.25, 174.75) | 0.607 |

| Stroke mechanism | |||

| Artery-to-artery embolism** | 18 (60%) | 10 (25.64%) | 0.027 |

| Perforators infarction** | 16 (48.48%) | 28 (71.79%) | 0.114 |

| Hemodynamic infarction | 7 (23.23%) | 5 (12.82%) | 0.253 |

| Basilar artery occlusion | 9 (30%) | 0 (0%) | < 0.001 |

| Mix mechanism | 18 (60%) | 8 (20.51%) | < 0.001 |

| Stenotic segment of the basilar artery | |||

| Proximal segment** | 15 (50%) | 17 (43.58%) | 0.506 |

| Middle segment** | 15 (50%) | 27 (69.23%) | 0.105 |

| Distal segment** | 3 (10%) | 3 (7.69%) | 1.000 |

| Multi-segment stenosis** | 3 (10%) | 6 (15.28%) | 0.722 |

| Stenosis degree (%) | 66.28±20.70 | 85.50±10.77 | < 0.001 |

| Clinical outcome** Unfavourable clinical outcome | 11 (%36.66) | 11 (%28.20) | 0.455 |

| Posterior collateral scores (poor collateral scores) | 13 (43.33) | 14 (35.89) | 0.530 |

LDL: low-density lipoprotein. Significant variables are shown in bold. *Mann-Witney U-test, **Pearson chi-square test/continuity correction test/Fisher exact test.

However, no significant statistical relationship was found between stroke recurrence in the patients with symptomatic BA stenosis and age; sex; the presence of DM, HT, smoking, AF, congestive heart failure, or CAD; clinical outcomes; haemodynamic infarction or perforatory stroke as the stroke mechanism; stenotic segments of the BA; posterior collateral scores (p > 0.05; Table 2).

Among the variables with a statistically significant relationship with symptomatic BA atherosclerotic stenosis and stroke recurrence that were evaluated using binary logistic regression, the most significant was the degree of stenosis (p < 0.001; odds ratio [OR], 1.074; Table 3).

Table 3.

Significant variables of stroke recurrence in acute ischaemic stroke patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the symptomatic basilar artery.

| p-value | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | ||||

|

Stroke mechanism being artery

to artery embolism Ref: Absent vs. present |

0.151 | 2.315 | 0.736 | 7.283 |

| Stenosis degree | < 0.001 | 1.074 | 1.029 | 1.119 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.393 | 0.986 | 0.899 | 1.043 |

Ref: references; vs.: versus. Significance of the model p < 0.001. Significant variables are shown in bold.

When the demographic, clinical, and radiological properties of the IS patients with symptomatic BA stenosis and clinical outcomes were examined, the significant variables were sex (p = 0.033), congestive heart failure (p = 0.050); artery-to-artery embolism (p = 0.008), BA occlusion (p < 0.001), or mixed mechanism as the stroke mechanism (p = 0.050); stenosis in the proximal basilary segments (p = 0.007); and stenosis in the mid-basilary segments (p = 0.020; Table 4).

Table 4.

Evaluation of variables affecting clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the symptomatic basilar artery.

| Variables | Patients with acute stroke due to basilar artery stenosis with unfavourable clinical outcome (n = 22) | Patients with acute stroke due to basilar artery stenosis with favourable clinical outcome (n = 47) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 70.00 ± 7.91 | 65.80 ± 9.55 | 0.078 |

| Sex** (male gender) | 8 (36.36%) | 30 (52.63%) | 0.033 |

| Hypertension** | 18 (81.81%) | 39 (68.42%) | 1.000 |

| Diyabetes mellitus** | 16 (72.72%) | 29 (61.70%) | 0.370 |

| Smoker** | 9 (40.90%) | 27 (57.44%) | 0.200 |

| Atrial fibrilation** | 1 (4.54%) | 4 (8.51%) | 1.000 |

| Congestive heart failure** | 8 (36.36%) | 6 (17.76%) | 0.050 |

| Coroner artery disease** | 9 (40.90%) | 16 (34.04%) | 0.580 |

| Stroke mechanism | |||

| Artery-to-artery** embolism | 15 (68.18%) | 16 (34.04%) | 0.008 |

| Perforators stroke** | 11 (50.00%) | 33 (70.21%) | 0.104 |

| Hemodynamic stroke** | 4 (18.18%) | 8 (17.02%) | 1.000 |

| Basilar artery occlusion** | 5 (22.72%) | 4 (8.51%) | 0.132 |

| Mix mechanism** | 12 (54.54%) | 14 (29.78%) | 0.050 |

| Segment of basilary artery | |||

| Proximal segment** | 15 (68.18%) | 17 (36.17%) | 0.007 |

| Mid-basilar segment** | 9 (40.90%) | 33 (70.21%) | 0.020 |

| Distal segment** | 3 (13.63%) | 3 (6.38%) | 0.375 |

| Multi-segment stenosis** | 4 (18.18%) | 5 (10.63%) | 0.452 |

| Stroke recurrence** | 11 (50.00%) | 19 (40.42%) | 0.455 |

| Degree of stenosis* | 74.00 (57.50, 95,00) | 80.00 (60.00, 90.00) | 0.891 |

| Basilar artery stenting** | 6 (27.27%) | 21 (44.68%) | 0.167 |

| Posterior collateral** scores (poor collateral scores) | 8 (36.66%) | 19 (40.42%) | 0.747 |

Significant variables are shown in bold. *Mann-Witney U-test, **Pearson chi-square test/continuity correction test/Fisher exact test.

However, no significant statistical relationships were found between the clinical outcomes of the patients with symptomatic BA stenosis and age; the presence of HT, DM, smoking, AF, or congestive heart failure; perforatory stroke, haemodynamic stroke, or BA occlusion as the stroke mechanism; stenosis in the distal basilar segment; multi-segment stenosis; stroke recurrence; degree of stenosis; posterior collateral scores and BA stenting procedure (p > 0.05; Table 4).

Among the variables with a statistically significant relationship with symptomatic BA atherosclerotic stenosis and unfavourable clinical outcomes that were evaluated using binary logistic regression, the most significant were sex (p = 0.06; OR, 9.776), congestive heart failure (p = 0.013; OR, 10.133), artery-to-artery embolism as the stroke mechanism (p = 0.042; OR, 3.874), atherosclerotic stenosis in the proximal BA (p = 0.022; OR, 4.716; Table 5).

Table 5.

Significant variables of clinical outcome in acute ischaemic stroke patients with atherosclerotic stenosis in the symptomatic basilar artery.

| p-value | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | ||||

| Sex Ref: female gender |

0.006 | 9.776 | 1.049 | 14.285 |

| Congestive heart failure Ref: present vs absent |

0.013 | 10.133 | 1.625 | 63.181 |

| Stroke mechanism being artery-to-artery embolism Ref: present vs absent |

0.042 | 3.874 | 1.049 | 14.285 |

| Atherosclerotic stenosis in the proximal basilar artery Ref: present vs absent |

0.022 | 4.716 | 1.245 | 17.868 |

Ref: references; vs: versus. Significance of the model < 0.001. Significant variables are shown in bold.

Discussion

According to the results of this study, the degree of atherosclerotic stenosis in symptomatic BA was an independent risk factor for stroke recurrence. The independent risk factors of unfavourable clinical outcomes in these patients were female sex, stenosis in the proximal segment, artery-to-artery embolism as the stroke mechanism, and congestive heart failure. The incidence of intracranial atherosclerotic disease is increasing with the ageing of society. A recent study reported that intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis most frequently occurs in the BA in IS patients. 17 In patients with IS due to intracranial atherosclerotic disease, stenting is recommended in the presence of recurrent IS despite the best medical treatment. This recommendation is based on data from the SAMMPRIS trial.9,10 However, even under aggressive medical treatment, the risk of recurrent IS due to intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis remains high.11,12

In our study, atherosclerotic stenosis of the BA was detected in 107 patients, of whom 69 (64%) were symptomatic. The mean follow-up period of the asymptomatic patients was 28.00 ± 18.034 months. None of the patients in the asymptomatic group had IS under aggressive medical treatment. The mean follow-up period in the symptomatic group was 25.53 ± 17.842 months. Of the 69 symptomatic patients, 30 (43.47%) had recurrent IS during the follow-up period. As this incidence rate was based on real-life data, it is much higher than those reported in randomised studies. 10 According to the findings of this study, atherosclerotic stenosis was most frequent in the mid-basilar segment but was rare in the distal BA. Similar incidence rates were obtained from the data reported by Edgar et al.. 6 The rarity of atherosclerotic stenosis in the distal basilar artery is consistent with the literature. 6 Patients with distal basilar artery stenosis were not included in the analysis due to the small number of cases. The degree of stenosis was established to be an independent risk factor for stroke recurrence in patients with symptomatic BA stenosis. According to the data from the Comparison of Warfarin and Aspirin for Symptomatic Intracranial Arterial Stenosis (WASID) trial, the degree of stenosis is related to stroke recurrence. 18 In our study, the independent risk factor of unfavourable clinical outcomes was female sex. The relationships between sex and IS and atherosclerosis are complex. Atherosclerosis has a different course in women and men. Atherosclerotic lesions progress slowly starting from the fourth and fifth decades in men and progress rapidly in women, starting from the sixth decade.19–21 Studies have indicated that stroke has a worse clinical outcome in women. 22 To our knowledge, no studies have reported the relationship between sex and IS due to BA atherosclerosis. Data from randomised studies that evaluated symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis have indicated that while no sex-related difference was found in the Chinese Intracranial Atherosclerosis (CICAS) trial, female sex was found to be a poor prognostic factor in the WASID trial.18,23

The most common stroke mechanism in patients with symptomatic BA atherosclerosis is perforatory stroke. MRI studies have shown that BA plaques have a long distribution and equally affect the ventral, dorsal, and lateral walls. These plaques do not have the same characteristics as those in the coronary and middle cerebral arteries. In addition, plaques in the BA tend to settle adjacent to the orifices of the penetrating arteries. 24 This can explain why the most common stroke mechanism is perforatory stroke.

The arterial-to-artery stroke mechanism is an independent risk factor for unfavourable clinical outcomes. A recent study found a correlation between the morphological features of plaques and IS mechanism due to symptomatic posterior intracranial atherosclerosis. The authors found that unstable plaques with a higher plaque burden and irregular surfaces were symptomatic of artery-to-artery embolism. 25 In intracranial atherosclerotic disease, IS due to an artery-to-artery embolic stroke mechanism is a poor prognostic factor.6,16

Congestive heart failure is another independent risk factor for unfavourable clinical outcomes. Congestive heart failure is quite common in the stroke population. It is also an important risk factor for IS in the normal population.26–29 Morbidity and mortality rates were found to be higher in IS patients with congestive heart failure. 30 This relationship may be the result of the close relationship between heart failure and atherosclerotic vascular disease.

The major limitation of this study is due to its retrospective nature and data from a single centre. More accurate information can be obtained through multi-centre prospective studies.

Conclusion

The most remarkable result of our study is that clinical outcomes were closely related to the female sex, artery-to-artery embolism as the stroke mechanism, and stenosis in the proximal segment. In patients with symptomatic BA stenosis, studies are needed to examine the effects of IS mechanisms and plaque morphologies on long-term stroke recurrence and clinical outcomes. Stroke mechanisms must be evaluated more clearly so that individualised treatments can be provided to these patients.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sci-10.1177_00368504241301519 for Evaluation of the effect on stroke mechanism, stroke recurrence and clinical outcome in stroke patients with basilar artery atherosclerosis: A single centre retrospective observational study by Yasemin Dinç, Rifat Özpar, Gizem Mesut, Farid Hojjati, Serhat Gökçe, Deniz Siğirli, Emel Oğuz Akarsu, Furkan Sarıdaş, Bahattin Hakyemez and Mustafa Bakar in Science Progress

Acknowledgements

Thank Prof. Edgar Samaniego for permission to use Figure 2.

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution: Yasemin Dinç: concepts; Yasemin Dinç: design; Mustafa Bakar, Yasemin Dinç, Emel Oğuz Akarsu, and Furkan Saridaş: definition of intellectual content; Yasemin Dinç, Rifat Özpar, and Serhat Gökçe: literature search; Yasemin Dinç, Gizem Mesut, Farid Hojjati, Emel Oğuz Akarsu, and Furkan Saridaş: clinical studies; Yasemin Dinç, Gizem Mesut, Farid Hojjati, Emel Oğuz Akarsu, and Furkan Saridaş: experimental studies: data acquisition; Deniz Sigirli, Yasemin Dinç, Rifar Özpar, Gizem Mesut, Farid Hojjati, Serhat Gökçe, Emel Oğuz Akarsu, and Furkan Saridaş: data analysis; Deniz Sigirli and Yasemin Dinç: statistical Analysis; Yasemin Dinç: manuscript preparation; Mustafa Bakar and Bahattin Hakyemez: manuscript Editing; Mustafa Bakar, Bahattin Hakyemez, Emel Oğuz Akarsu, and Furkan Saridaş: manuscript review.

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Bursa Uludag University, Faculty of Medicine approved the study (26 September 2023; 2023-18/24).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor: Yasemin Dinç.

Informed Consent: The need for informed consent was waived by The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Bursa Uludag University, Faculty of Medicine. This article has been published as a preprint. Preprint DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3867836/v1.

ORCID iD: Yasemin Dinç https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0342-5939

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Merwick A, Werring D. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. Br Med J 2014; 348: 3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pirson FAVA, Boodt N, Brouwer J, et al. Etiology of large vessel occlusion posterior circulation stroke: results of the MR CLEAN registry. Stroke 2022; 53: 2468–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee G, Stone SP, Werring DJ. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. Br Med J 2018; 361: k1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caplan LR. Primer on cerebrovascular diseases. London, UK: Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israeli-Korn SD, Schwammenthal Y, Yonash-Kimchi T, et al. Ischemic stroke due to acute basilar artery occlusion: proportion and outcomes. Isr Med Assoc J 2010; 12: 671–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samaniego EA, Shaban A, Ortega-Gutierrez S, et al. Stroke mechanisms and outcomes of isolated symptomatic basilar artery stenosis. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2019; 4: 189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattle HP, Arnold M, Lindsberg PJ, et al. Basilar artery occlusion. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voetsch B, DeWitt LD, Pessin MSet al. et al. Basilar artery occlusive disease in the new England medical center posterior circulation registry. Arch Neurol 2004; 61: 496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleindorfer D.O, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, 364–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet 2014; 383: 333–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan Y, Meng X, Jing J, et al. CHANCE investigators. Association of multiple infarctions and ICAS with outcomes of minor stroke and TIA. Neurology 2017; 88: 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Wong KS, Leng X, et al. CHANCE investigators. Dual antiplatelet therapy in stroke and ICAS: subgroup analysis of CHANCE. Neurology 2015; 85: 1154–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinç Y, Bakar M, Hakyemez B. Causes of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Turk J Neurol 2020; 26: 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in acute stroke treatment . Stroke 1993; 24: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng X, Chan KL, Lan L, , et al. Stroke mechanisms in symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic disease: classification and clinical implications. Stroke 2019; 50: 2692–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinç Y, Ozpar R, Mesut G, et al. Evaluation of intracranial atherosclerotic disease risk factors in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Neurol Asia 2023; 28: 809–816. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1305–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bae HJ, Lee J, Park JM, et al. Risk factors of intracranial cerebral atherosclerosis among asymptomatics. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007; 24: 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López-Cancio E, Dorado L, Millán M, et al. The Barcelona – asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis (AsIA) study: prevalence and risk factors. Atherosclerosis 2012; 221: 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pu Y, Liu L, Wang Y, et al. Geographic and sex difference in the distribution of intracranial atherosclerosis in China. Stroke 2013; 44: 2109–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeves MJ, Bushnell CD, Howard G, et al. Sex differences in stroke: epidemiology, clinical presentation, medical care, and outcomes. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 915–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pu Y, Wei N, Yu D, et al. Chinese Intracranial AtheroSclerosis (CICAS) study group: sex differences do not exist in outcomes among stroke patients with intracranial atherosclerosis in China: subgroup analysis from the Chinese intracranial atherosclerosis study. Neuroepidemiology 2017; 48: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Li M, Xu Y, et al. Plaque distribution of low-grade basilar artery atherosclerosis and its clinical relevance. BMC Neurol 2017; 17: –6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song X, Li S, Du H, et al. Association of plaque morphology with stroke mechanism in patients with symptomatic posterior circulation ICAD. Neurology 2022; 99: 2708–2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim W, Kim EJ. Heart failure as a risk factor for stroke. J Stroke 2018; 20: 33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R, et al. Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137: 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jelinek MV, Ansari MZ. Congestive cardiac failure (CCF) as a cause of fatal stroke and all-cause death. Aust N Z J Med 1998; 28: 799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witt BJ, Brown RD, Jr, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Ischemic stroke after heart failure: a community-based study. Am Heart J. 2006;152:102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siedler G, Sommer K, Macha K, et al. Heart failure in ischemic stroke: relevance for acute care and outcome. Stroke 2019; 50: 3051–3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sci-10.1177_00368504241301519 for Evaluation of the effect on stroke mechanism, stroke recurrence and clinical outcome in stroke patients with basilar artery atherosclerosis: A single centre retrospective observational study by Yasemin Dinç, Rifat Özpar, Gizem Mesut, Farid Hojjati, Serhat Gökçe, Deniz Siğirli, Emel Oğuz Akarsu, Furkan Sarıdaş, Bahattin Hakyemez and Mustafa Bakar in Science Progress