Abstract

Out-of-home storage of personal firearms is one recommended option for individuals at risk of suicide, and statewide online maps of storage locations have been created in multiple states, including Colorado and Washington. We sought to examine both the extent to which firearm retailers and ranges offer temporary, voluntary firearm storage and the perceived barriers to providing this service. We invited all firearm retailers and ranges in Colorado and Washington to complete an online or mailed survey; eligible sites had to have a physical location where they could provide storage. Between June-July 2021, 137 retailers/ranges completed the survey (response rate=25.1%). Nearly half (44.5%) of responding firearm retailers/ranges in Colorado and Washington State indicated they had ever provided firearm storage. Among those who had ever offered storage, 80.3% currently offered storage while 19.7% no longer did. The majority (68.6%) of participants had not heard of the Colorado/Washington gun storage maps and 82.5% did not believe they were currently listed on the maps. Respondents indicated liability waivers would most influence their decision about whether to start or continue providing temporary, voluntary storage of firearms. Understanding current practices, barriers, and concerns about providing out-of-home storage by retailers and ranges may support development of more feasible approaches for out-of-home firearm storage during times of suicide risk.

Keywords: Suicide prevention, lethal means, community-based interventions, firearm

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, over half of all suicides are by firearm(WISQARS (Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System)∣Injury Center∣CDC, 2020). In Colorado and Washington State, suicide is the 7th and 8th leading cause of death, respectively, and each state reported that firearm suicides were approximately three-fold more common than firearm homicides in 2019.(WISQARS (Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System)∣Injury Center∣CDC, 2020) The prevention of firearm suicide must be multifaceted(Zalsman et al., 2016), but one key component is “lethal means safety,” where access to the most lethal means of suicide are reduced to lessen the potential lethality of any suicide attempt(C. W. Barber & Miller, 2014; Mann et al., 2005). This is particularly important for firearms, given the high lethality of firearm suicide attempts (over 85% result in death)(Spicer & Miller, 2000). Lethal means safety with regard to firearms can involve multiple strategies, including court-ordered or temporary, voluntary out-of-home storage(Allchin et al., 2019).

Previous studies show that storage suppliers are supportive of voluntary storage programs and are motivated by their desire to help their community; however they also cite logistical, legal, and liability concerns(Betz et al., 2022). In both Colorado and Washington State, there are a plethora of firearm retailers and shooting ranges that could potentially provide storage services to the public (over 300 in Colorado and 200 in Washington) that are distributed across both urban and rural counties. Types of retailers/ranges that can feasibly offer storage services include both large and small organizations/businesses including, specialty stores, sporting goods stores, ranges and/or public gun clubs; however National chain retail stores have not historically provided storage services and most often managers of branches of national retailers can't decide to offer storage without corporate guidance/approval. Those locations that do provide storage offer a potential option for the public to seek out voluntary, out of home firearm storage. Previous studies have shown a willingness on the part of some firearm retailers to provide firearm storage(Tung et al., 2019; Walton & Stuber, 2020); however, legal, liability and logistical issues were identified as barriers to potentially providing such storage(Pierpoint et al., 2019). Overall, little is known about the practical experience of out-of-home storage providers. This information gains additional importance given the rise in firearm sales during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among new owners, and the marked increase in depression and anxiety across multiple age- and gender-groups in the U.S.(Abdallah et al., 2021; Caputi et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Daly & Robinson, 2021; Helmore, 2021). This increased prevalence of firearms may affect demand for out-of-home storage in that there are more firearms/firearm owners who may need this service.

One question related to out-of-home firearm storage has been how firearm owners might quickly and easily find storage locations; in response, public health professionals in Colorado developed the first statewide map showing firearm ranges, retailers, and law enforcement agencies willing to consider voluntary firearm storage.(“Gun Storage Map,” 2019; Kelly et al., 2020) Subsequent maps have been published in Washington and other states(Bongiorno et al., 2021; Washington Firearm Safe Storage Map - Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center, n.d.). These maps are relatively new and have not been publicized widely beyond initial outreach for storage site participation. To better understand the utility of such maps – and the underlying concept of out-of-home voluntary storage – we sought to survey firearm retailers and ranges in Colorado and Washington State to assess: (1) the extent to which retailers and ranges offer temporary, voluntary firearm storage; (2) their knowledge of storage maps; and (3) factors (including policy/regulation, COVID-19 considerations, and practical considerations) that impact provision of storage or willingness to be identified on a publicly available map. Findings from this study can inform the development and refinement of maps and other programs to encourage and facilitate voluntary, temporary, out-of-home firearm storage.

METHODS

Study Population and Design

Eligible participants were English-speaking individuals who owned or managed a firearm range and/or retailer located in Colorado or Washington State. Our study population was determined through preexisting lists from precious projects from the study team of retailers and ranges that were updated through a repeated search. (“Gun Storage Map,” 2019; Kelly et al., 2020) There was no comprehensive sampling frame for gun retailers, so we triangulated data to build a comprehensive dataset of gun retailers and ranges in both Colorado and Washington state. We conducted an initial search for additional locations using Google map searches by county for gun shop(s), firearm(s), armory, shooting range, or firing range. To verify the accuracy of locations and update contact information, we utilized Federal Firearms Licensee listings and web searches. The Federal Firearms License listings itself could not serve as a comprehensive sample frame because they do not include firearm ranges or gunsmiths who are not licensed to sell firearms - yet may be willing to store firearms and include licensed sellers who do not have a physical location to provide storage, such as individuals who sell firearms out of their own home or online. We excluded sites that had closed permanently, national chain retailers (e.g., Walmart), and individual retailers without a physical business location or web presence indicating they may be capable of providing storage. Additionally, those with non-working phone numbers, websites that were not maintained, or addresses that were invalid were deemed ineligible and are also less likely to provide or be used as a temporary storage option. We invited respondents through serial invitations to our list of firearms retailers and ranges. We initiated outreach through email (when possible) or mail. The invitation included a cover letter signed by the study PI and noted that the survey was developed in consultation with firearms industry groups. Non-responders were re-contacted with up to three emails, three letters, or three phone calls. Participants could complete the survey online (via REDCap) or by mailing back a paper version of the survey in a pre-stamped envelope. Participants who completed the survey received a $50 electronic gift card. This study met both institutions’ guidelines for protection of human subjects concerning their safety and privacy and was deemed exempt by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and the University of Washington IRB.

Survey Instrument

The 36-item survey (Supplementary Material) instrument included: self-reported demographic information, questions on storage experiences (e.g., frequency of and reasons for requests); perceived barriers and facilitators to providing temporary, voluntary out of home storage and participating in storage maps; policy recommendations; and optimal avenues for public education about out-of-home storage, and ways that the COVID-19 pandemic have impacted business operations. The survey also asked about the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted business operations. This was an area of interest of our expert advisory committee (which includes owners of firearm businesses) because financial issues stemming from lack of inventory/sales could lead to a decrease in business hours or businesses seeking other means of revenue (such as charging for storage). When possible, we used questions from prior survey instruments.(Brooks-Russell et al., 2019; Pierpoint et al., 2019) We pretested the instrument and recruitment materials with various stakeholders, including representatives from firearms industry groups. Both the survey and the invitation cover letter were reviewed by the study’s external advisory board (including owners of firearm businesses) to enhance messaging and participation. Pretesting also included cognitive interviews with stakeholders to examine how they understood survey questions.. Quality and accuracy of the survey questions was ensured by modifying the instrument to reduce sources of response error. The survey was conducted in English only.

Analysis

Surveys collected by mail were entered into a secure database and merged with surveys completed online. Quality control procedures included excluding surveys with inconsistencies, implausible answers, or comments that made participants ineligible (such as owners not answering questions about storage or reporting their business had closed). We used descriptive statistics and examined participants by state, by those that have "ever" vs "never" offered storage, and by current storage practices (currently offer storage vs do not). To test for differences in responses between these stratifications, we used Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables due to small sample sizes in some cells. These hypothesis tests were performed in order to determine factors associated with the provision of storage, thereby shedding light on potential avenues of policy change to encourage out-of-home storage. To evaluate how responders to our survey may differ from non-responders, we examined if there were differences in urban/rural classifications. We used zip codes based on mailing addresses to derive rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) classifications for urban and rural designations. Overall, 23.6% of those eligible for our survey were rural and 76.4% were urban, when evaluating survey completers vs non-completers, there was no statistical difference (p 0.140) between urban and rural classifications. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for significance testing. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.0.5; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Demographic Information

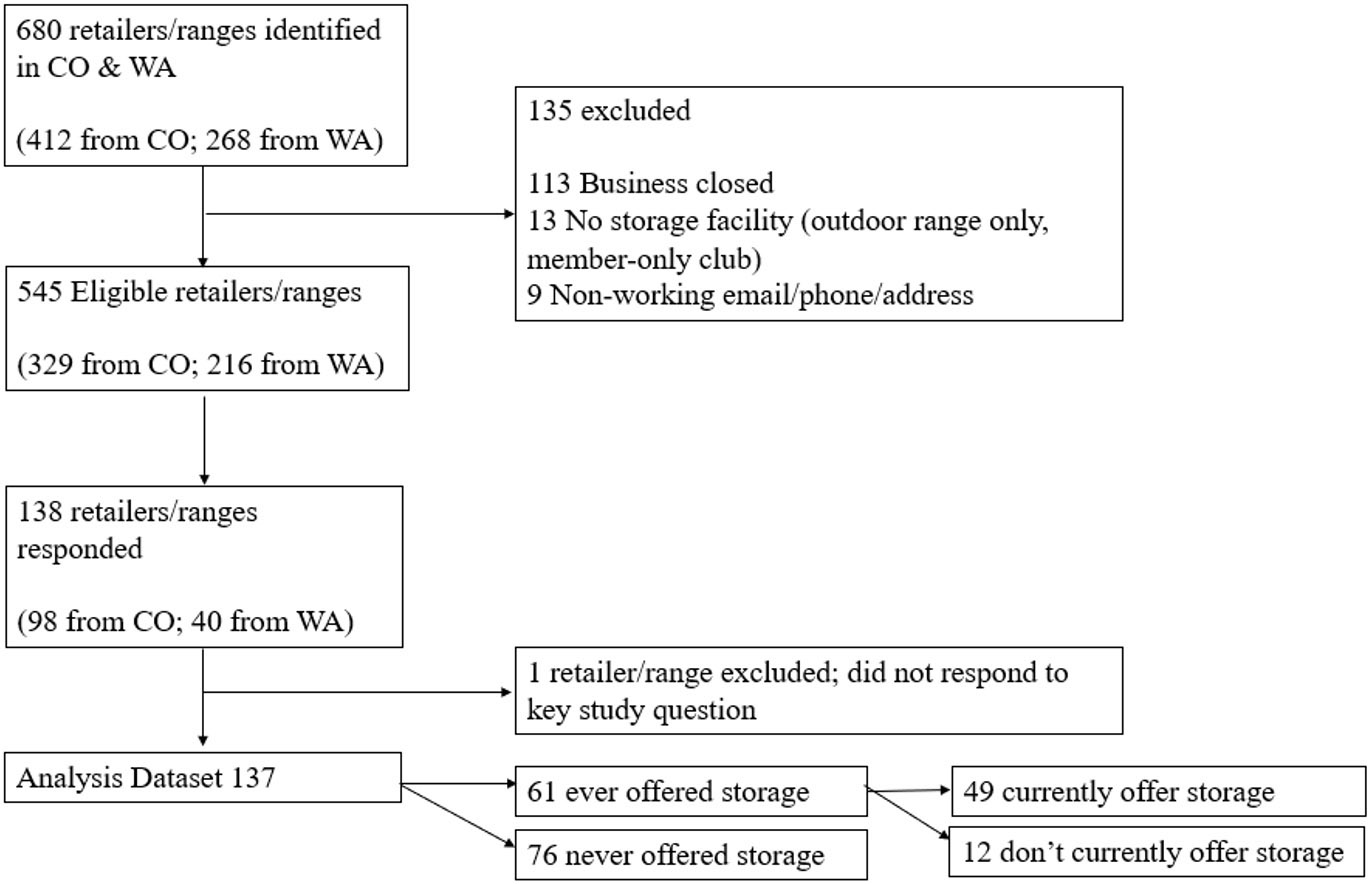

A total of 545 (329 from Colorado and 216 from Washington) retailers and ranges were eligible to participate in our survey (Figure 1). We received 138 total responses between June-July 2021 for a response rate of 25.1%. A total of 137 responses answered our main study question about storage provision and were included in this analysis. The majority of respondents were white (110, 86.6%), non-Hispanic (103, 82.4%) and male (92, 72.4%). Most (77, 56.2%) were the owner/co-owner, 17.5%(24) were the manager, 20.4%(28) were both and 5.8%(8) were other (Employee, or Executive associated with the organization). The majority (101, 73.7%) of retailers/ranges surveyed had 5 or fewer employees; 12.4%(17) reported having over 11 employees(Table 1). Responses were generally similar across states (supplemental Table 1), so our primary analyses combined responses from Colorado and Washington.

Figure 1:

Participant eligibility flow chart

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of survey participants from firearm retailers/ranges, by ever or never offered storage (N=137)

| Retailer/range variable [N (%)] | Overall (N = 137) |

Never offered storage (N = 76) |

Ever offered storage (N = 61) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.128 | |||

| Male | 92 (72.4%) | 48 (63.2%) | 44 (72.1%) | |

| Female | 29 (22.8%) | 15 (19.7%) | 14 (23.0%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 (3.9%) | 5 (6.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Missing | N = 10 | N = 7 | N = 3 | |

| Race^ | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.502 |

| Asian | 3 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.3%) | 0.086 |

| Black/African American | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 |

| White | 110 (86.6%) | 56 (80.0%) | 54 (94.7%) | 0.033 |

| Prefer not to answer | 13 (10.2%) | 11 (15.7%) | 2 (3.5%) | 0.038 |

| Missing | N = 10 | N = 6 | N = 4 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.014 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 (5.6%) | 6 (7.9%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 103 (82.4%) | 49 (64.5%) | 54 (88.5%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 15 (12.0%) | 12 (15.8%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Missing | N = 12 | N = 9 | N = 3 | |

| Role in business | <0.001 | |||

| Owner / Co-owner | 77 (56.2%) | 32 (42.1%) | 45 (73.8%) | |

| Manager | 24 (17.5%) | 18 (23.7%) | 6 (9.8%) | |

| Both | 28 (20.4%) | 18 (23.7%) | 10 (16.4%) | |

| Other | 8 (5.8%) | 8 (10.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Number of employees at location | 0.169 | |||

| 5 or fewer | 101 (73.7%) | 56 (73.7%) | 45 (73.8%) | |

| 6-11 | 19 (13.9%) | 8 (10.5%) | 11 (18.0%) | |

| 12-19 | 8 (5.8%) | 7 (9.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| 20 or more | 9 (6.6%) | 5 (6.6%) | 4 (6.6%) | |

| Has ever provided firearm storage when individual subject to a court order | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 28 (28.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 28 (60.9%) | |

| No | 67 (68.4%) | 50 (96.2%) | 17 (37.0%) | |

| Missing/not applicable | N = 42 | N = 26 | N = 16 |

Responses may add up to >100% because participants could select all that applied.

Storage Experience & Current Practices

Among responding firearm retailers/ranges in Colorado and Washington State, 61 (44.5%) indicated they had ever provided firearm storage, while 76 (55.5%) never had. Locations that said they had ever offered storage were more likely to have had an owner/co-owner complete the survey, but business size did not differ by storage history. Those retailers/ranges who had ever offered storage were more likely (p <0.001) to have received requests (regardless of if they agreed to provide storage) for firearm storage in the past 12 months, with 68.9%(34) receiving at least one request in the past year compared to 18.4%(22) among those who never offered temporary, voluntary out-of-home storage. Conversely, those who had never offered storage were more likely to say they had never received a storage request (47, 61.8% vs 2, 3.3%, p <0.001; Table 2).

Table 2:

Business operations, impacts of COVID-19, and storage map knowledge among firearm retailers/ranges, by ever or never offered storage (N=137)

| Gun Storage Map related variables | Overall (N = 137) |

Never offered storage (N = 76) |

Ever offered storage (N = 61) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How frequently did you receive requests for firearm storage in the past 12 months for any reason (whether or not you agreed to provide storage)? | <0.001 | |||

| More than 20 requests | 5 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (8.2%) | |

| 10-20 requests | 3 (2.2%) | 1 (1.3%) | 2 (3.3%) | |

| 3-9 requests | 18 (13.1%) | 4 (5.3%) | 14 (23.0%) | |

| 1-2 requests | 30 (21.9%) | 9 (11.8%) | 21 (34.4%) | |

| No requests in the past 12 months but we have received at least one request in the past | 32 (23.4%) | 15 (19.7%) | 17 (27.9%) | |

| We have never received a request | 49 (35.8%) | 47 (61.8%) | 2 (3.3%) | |

| How did COVID-19 affect your business operations in 2020?^ | ||||

| Sales have increased | 85 (62.0%) | 39 (51.3%) | 46 (75.4%) | <0.001 |

| Sales have decreased | 28 (20.4%) | 19 (25.0%) | 9 (14.8%) | 0.048 |

| Problems with inventory for firearms | 84 (61.3%) | 42 (55.3%) | 42 (68.9%) | 0.222 |

| Problems with inventory for ammunition | 95 (69.3%) | 50 (65.8%) | 45 (73.8%) | 0.590 |

| Had to reduce our staffing | 10 (7.3%) | 5 (6.6%) | 5 (8.2%) | 1 |

| Had to increase our staffing | 13 (9.5%) | 4 (5.3%) | 9 (14.8%) | 0.229 |

| Concerns about ability to stay in business | 28 (20.4%) | 15 (19.7%) | 13 (21.3%) | 0.370 |

| Delayed making changes, such as new programs or policies | 25 (18.2%) | 16 (21.1%) | 9 (14.8%) | 0.059 |

| Training programs have increased | 25 (18.2%) | 10 (13.2%) | 15 (24.6%) | 0.219 |

| Trainings programs have decreased | 13 (9.5%) | 9 (11.8%) | 4 (6.6%) | 0.281 |

| Have you heard of the Colorado/Washington gun storage map? | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 42 (30.7%) | 16 (18.2%) | 26 (53.1%) | |

| No | 94 (68.6%) | 72 (81.8%) | 22 (44.9%) | |

| To the best of your knowledge, is your agency listed on the map? | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 22 (16.1%) | 2 (2.3%) | 20 (40.8%) | |

| No | 113 (82.5%) | 85 (96.6%) | 28 (57.1%) | |

| To what extent is your clientele aware that you participate in the map?* | 0.636 | |||

| Very aware | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Somewhat aware | 7 (31.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | |

| A little aware | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | |

| Very unaware | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | |

| I don't know | 12 (54.5%) | 2 (100.0%) | 10 (50.0%) | |

| To what extent does your clientele support your participation in the map?* | 0.550 | |||

| They completely support our participation | 8 (36.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | |

| They somewhat support our participation | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | |

| They somewhat disagree with our participation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| They completely disagree with our participation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| They probably don't know about it | 13 (59.1%) | 2 (100.0%) | 11 (55.0%) | |

| How has participation affected the volume of storage requests?* | 0.697 | |||

| Requests for storage have increased a lot | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Requests for storage have increased a little | 4 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | |

| Requests for storage are about the same | 7 (31.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | |

| Requests for storage have decreased a little | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Requests for storage have decreased a lot | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | |

| I don't know | 10 (45.5%) | 2 (100.0%) | 8 (40.0%) |

Responses may add up to >100% because participants could select all that applied.

Only asked of participants who believed their agency was listed on the map (N=22)

Among the 61 sites who had ever offered storage, 49 (80.3%) currently offered storage while 12 (19.7%) no longer did (Table 3). The most common circumstance for storage provision among those who ever provided storage, was travel out of town (22, 39.3%), followed by safety concerns (17, 30.4%), divorce (17, 30.4%), relative who passed away (13, 23.2%), military deployment (12, 21.4%), addiction/medical/mental health treatment (10, 17.9%), moving (9, 16.1%), guest in home (9, 16.1%), and other (16, 28.6%). Some retailers/ranges do not collect information on the specific reason why a customer may request storage; "upon request" was the sole explanation given for providing storage 9.8% (6) of the time. . For those currently offering storage, the most common method of firearm storage was locked firearm storage where only store staff have access (39, 90.7%) followed by rental of storage lockers where the firearm owner retains possession of the key (2, 4.7%). Those who currently offer storage were more likely to have provided storage for all requests (35, 77.8% vs 3, 27.3%, p<0.001) compared to those who do not currently provide storage. Among those who have ever provided storage, only 14.3%(8) indicated ever declining to return a firearm due to safety concerns (Table 3).

Table 3:

Suggested title: Storage experiences among retailers/ranges that have ever offered storage, by current storage practice (N=61)

| Retailers that have ever offered storage |

Overall (N = 61) |

No current storage (N = 12) |

Current storage (N = 49) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under what circumstances have you provided storage?^ | ||||

| Travel out of town | 22 (39.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 21 (46.7%) | 0.036 |

| Safety concerns / suicide concerns | 17 (30.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 15 (33.3%) | 0.473 |

| Prohibited individual is guest in the home | 9 (16.1%) | 2 (18.2%) | 7 (15.6%) | 1 |

| Divorce | 17 (30.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 15 (33.3%) | 0.473 |

| Military deployment | 12 (21.4%) | 3 (27.3%) | 9 (20.0%) | 0.686 |

| Relative who has passed away | 13 (23.2%) | 1 (9.1%) | 12 (26.7%) | 0.426 |

| During addiction, medical or mental health treatment | 10 (17.9%) | 1 (9.1%) | 9 (20.0%) | 0.667 |

| Moving | 10 (17.9%) | 1 (9.1%) | 9 (20.0%) | 0.667 |

| Other | 41 (73.2%) | 6 (54.5%) | 35 (77.8%) | 0.142 |

| Upon Request sole response (no other reasons indicated) | 6 (9.8%) | 1 (8.3%) | 5 (10.2%) | 1 |

| Missing | N = 5 | N = 1 | N = 4 | |

| What type of storage have you offered?^ | ||||

| Rental of storage lockers where the owner retains possession of the key | 4 (7.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 2 (4.7%) | 0.169 |

| Locked firearm storage where our store staff have access | 47 (87.0%) | 8 (72.7%) | 39 (90.7%) | 0.358 |

| Other | 3 (5.6%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (4.7%) | 0.488 |

| Missing | N = 7 | N = 1 | N = 6 | |

| How frequently did you agree to provide firearm storage? | <0.001 | |||

| Provided storage for all requests | 38 (67.9%) | 3 (27.3%) | 35 (77.8%) | |

| Provided storage for more than half of requests | 10 (17.9%) | 2 (18.2%) | 8 (17.8%) | |

| Provided storage for less than half of requests, but at least one | 8 (14.3%) | 6 (54.5%) | 2 (4.4%) | |

| Missing | N = 5 | N = 1 | N = 4 | |

| Has your business ever declined to return a firearm that was being temporarily stored in your facility due to safety concerns? | 0.063 | |||

| Yes | 8 (14.3%) | 4 (36.4%) | 4 (8.9%) | |

| No | 47 (83.9%) | 7 (63.6%) | 40 (88.9%) | |

| Missing | N = 6 | N = 1 | N = 5 | |

| How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your business operations as they relate to storage provision? | 0.038 | |||

| We are more likely to provide storage when requested | 4 (7.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (8.9%) | |

| We are less likely to provide storage when requested | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| About the same | 48 (85.7%) | 8 (72.7%) | 40 (88.9%) | |

| Missing | N = 7 | N = 2 | N = 5 |

The majority of retailers/ranges indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had affected their business with respect to problems with inventory of ammunition (95, 69.3%) and firearms (84, 61.3%). Overall, most (85, 62.0%) respondents indicated that with the COVID-19 pandemic, sales had increased. However, this was significantly higher among those reporting that they had ever offered firearm storage (57, 75.4% vs 38, 51.3%, p<0.001) (Table 2). Among those ever providing storage, 4 (8.9%) said that COVID-19 had made them more likely to provide storage when asked (Table 3).

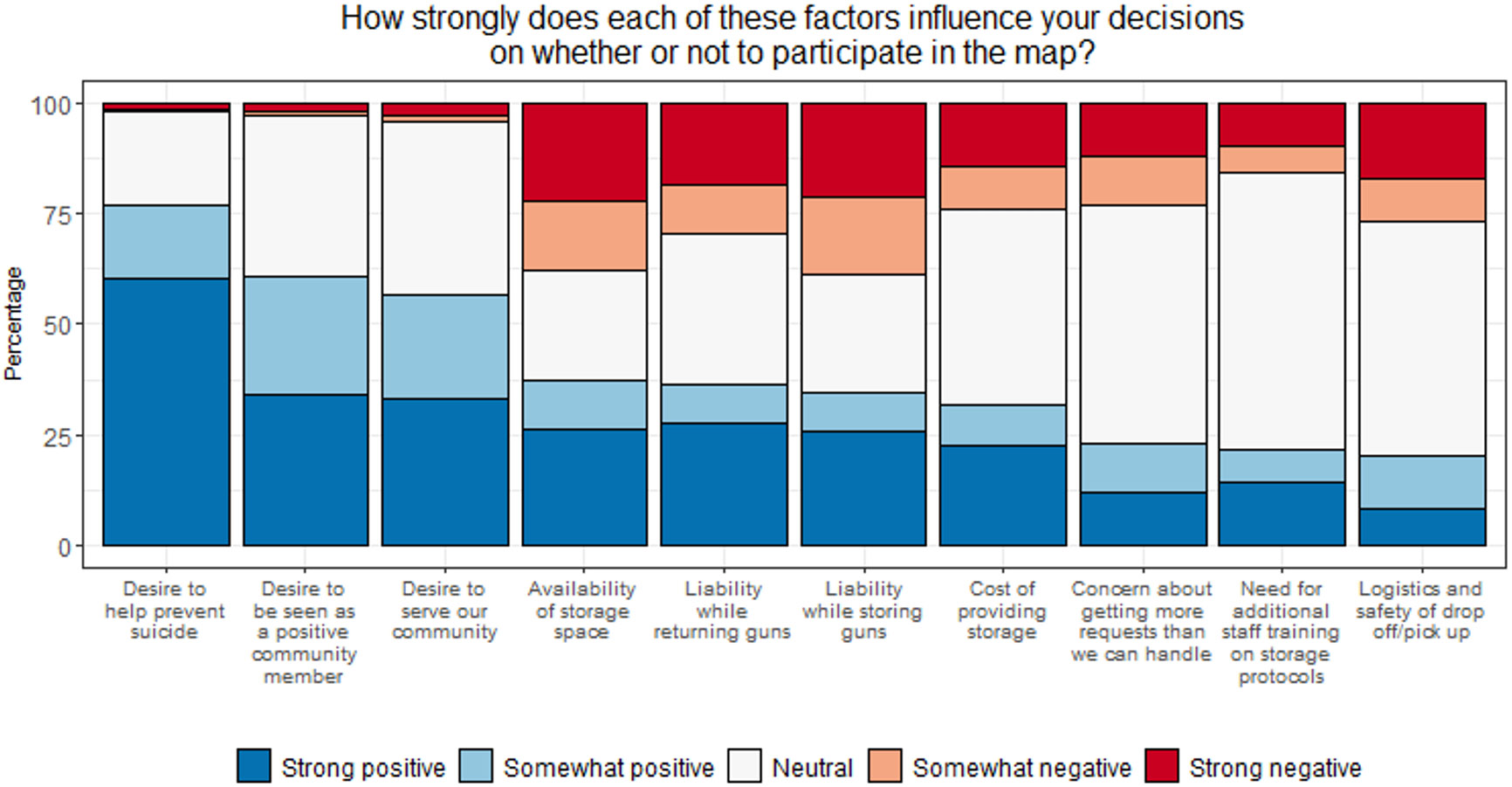

Knowledge of and Participation in Firearm Storage Maps

The majority of retailers/ranges survey participants had not heard of the Colorado/Washington gun storage map in their respective state (94, 68.6%) and did not think they were currently listed on the map (113, 82.5%). Of those on the map, the majority were unsure if their clientele knew they were listed on the map (12, 54.5%). Most respondents indicated that they weren’t sure (10, 45.5%) if requests for storage had increased as a result of their identification on the map; fewer said requests had increased a little (4, 18.2%) or stayed the same (7, 31.8%; Table 2). Among all survey respondents, when asked how strongly certain factors would influence their decision on whether to participate in the map, 74.5%(102) stated that a desire to help prevent suicide was strongly or somewhat positive, followed by desire to be seen as a positive community member (81, 59.1%) or a desire to serve their community (74, 54.0%; Figure 2). Liability while storing guns (53, 38.7%) and availability of storage space (51, 37.2%) were the most frequently cited negative factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Factors Influencing Participation in the Map (N=137)

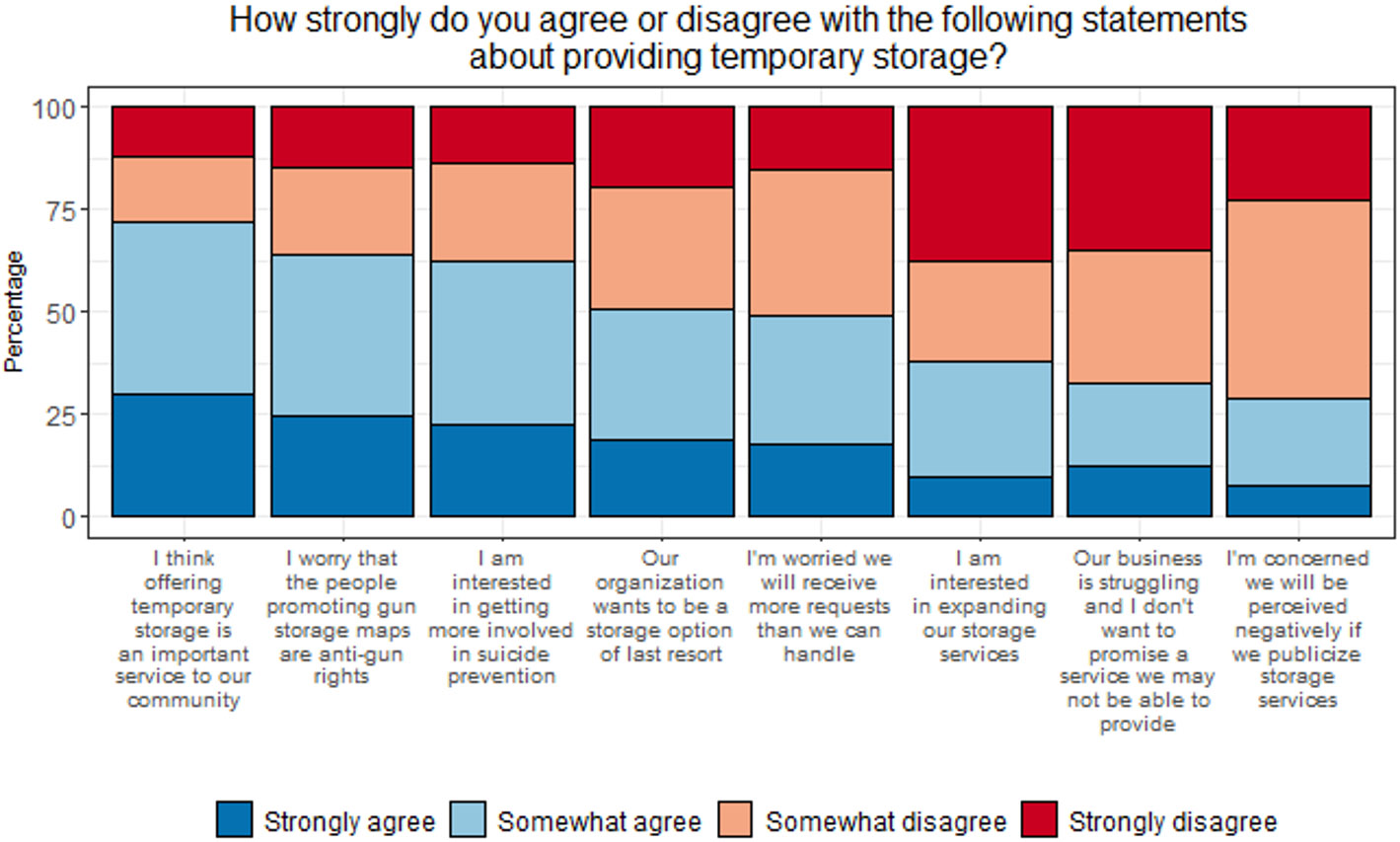

Theoretical Support, Barriers & Solutions

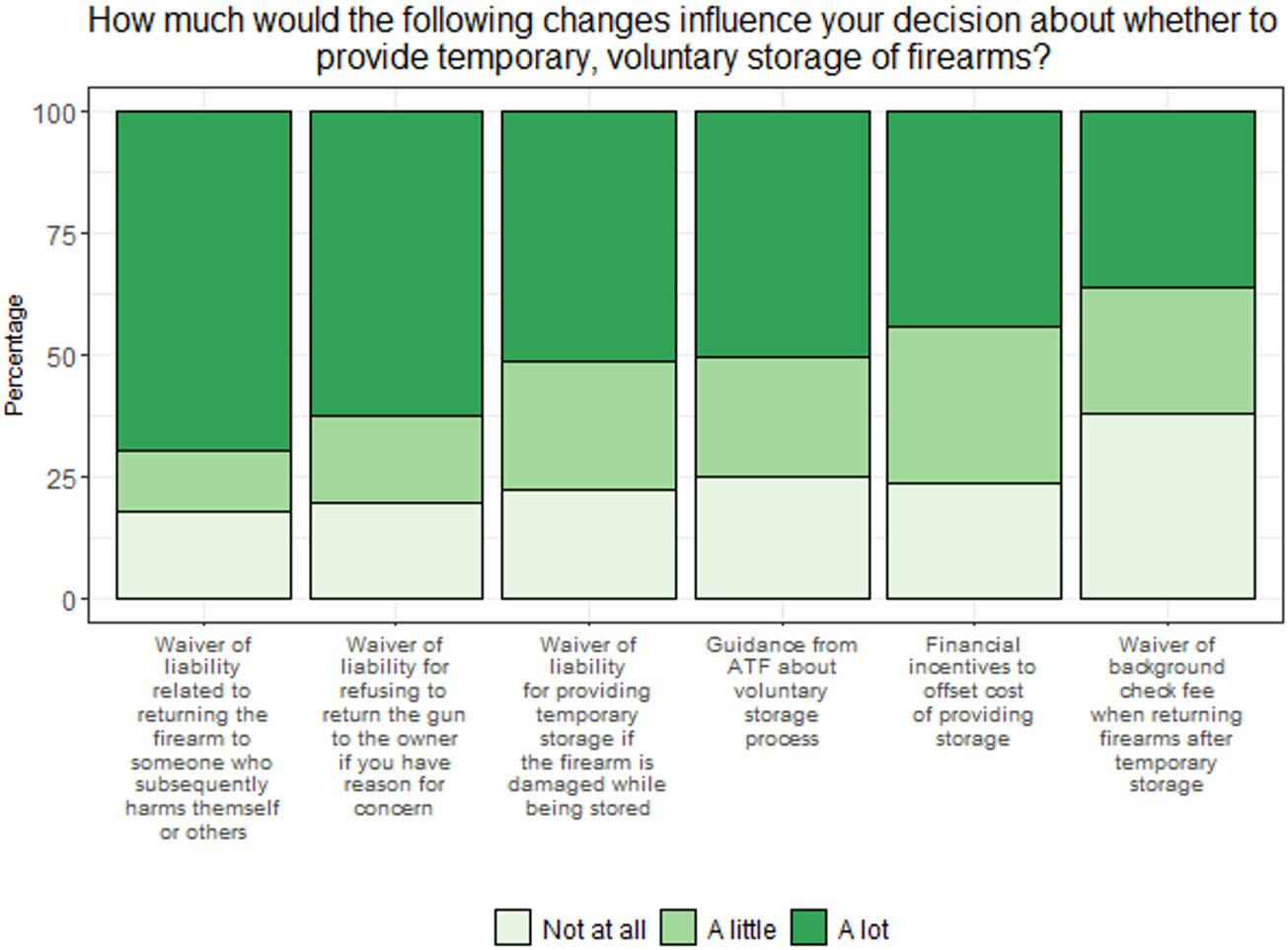

When asked “how strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements about providing temporary storage?”, the majority of firearm retailers/ranges indicated that they agreed with the statements: “I worry that the people promoting gun storage maps are anti-gun rights” (82, 59.8%), “I think offering temporary storage is an important service to our community” (90, 65.7%); and disagreed with the following statements: “I'm concerned we will be perceived negatively if we publicize storage services” (66, 70.2%), “Our business is struggling and I don't want to promise a service we may not be able to provide” (83, 60.6%; Figure 3). The survey asked about policy or regulatory changes that would most influence their decision about whether to provide temporary, voluntary storage of firearms, or their decision to continue to do so. The changes for which the largest proportions responded "a little" or "a lot" were liability waivers for "returning the firearm to someone who subsequently harms themself or others”(100, 72.9%) and for "refusing to return the gun to the owner if you have reason for concern”(98, 71.6%).(Figure 4).

Figure 3:

Statements about providing temporary storage (N=137)

Figure 4:

Factors Influencing Providing Storage (N=137)

DISCUSSION

Approximately 42% of American adults report living in a home with a firearm according to a nationally representative survey(NW et al., n.d.) and among firearm owners, there is support for state-level lethal means policies and programs(Carter et al., 2022). Lethal means counseling and public education efforts often suggest voluntary, temporary, out-of-home storage during periods of crisis as a way to reduce firearm access and prevent suicide, and state storage maps(Bongiorno et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2020) have been developed to facilitate identification of nearby storage locations. The autonomy of seeking storage in this way may be more appealing as opposed to legal interventions such as Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Such maps – and voluntary storage in general – are unlikely to significantly impact suicide death rates without attention to the experiences, views, and preferences of potential storage providers. In this survey, we present new information concerning the extent to which retailers/ranges in Colorado and Washington offer temporary, voluntary firearm storage, along with their views on factors that impact provision of storage or participation in a map.

Firearm retailers/ranges may be a key safety resource for the firearm owning community when they are willing to provide temporary, voluntary out-of-home storage. Previous studies(Brooks-Russell et al., 2019; Pierpoint et al., 2019) indicated that 67.6% of firearm retailers in the Mountain West region were willing to provide storage options—more than are actually doing so as reported by our study participants. Among firearm retailers/ranges who responded to our survey in Colorado and Washington State, 35.7% currently offered temporary, voluntary out-of-home storage and 41.6% have ever offered storage. Some retailers may not have provided storage before – or even considered it - because they haven’t been asked by clientele. Broader education campaigns, including guidance for retailers, might encourage some locations to provide storage as well as notifying the general public that such a service is available.

The majority of retailers/ranges indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had affected their business through inventory challenges. Interestingly, more respondents who reported providing storage indicated that in the COVID-19 pandemic, sales had increased compared to those who do not offer storage. One explanation for this association is that larger gun retailers may have been in a better position both to offer storage and meet increased retail demand for guns during the pandemic. Sales for firearms increased during the COVID-19 pandemic(Caputi et al., 2020), with some studies showing that first time firearm purchasers are at higher suicide risk(Studdert et al., 2020) and that those who purchased firearms during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely than non–firearm owners to report suicidal ideation(Anestis et al., 2021). Ensuring voluntary, firearm storage at retailer/range locations may be critical to reducing firearm suicides especially during the pandemic.

Financial concerns may be important barriers for being able to offer firearm storage—if retailers/ranges are concerned about their business surviving - especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Forty percent of respondents agreed with the statement: “Our business is struggling, and I don't want to promise a service we may not be able to provide”. This may lead to them either charging for storage or eliminating it as additional costs associated with the activity (staff time, background checks, reduction in space for inventory) contribute to financial issues. However, 66.5% of respondents indicated that financial incentives to offset cost of providing storage would the influence their decision about whether to provide temporary, voluntary storage of firearms a little or a lot, a feasible solution to this issue.

Most retailers/ranges had not heard of the Colorado/Washington gun storage map and did not think they were currently listed on the map. Of the few who knew they were on the firearm storage maps, it’s unclear if their customers knew of this or if storage requests have increased as a result of being listed. An overwhelming majority of retailers/ranges indicated a positive view of the map program in their desire to help prevent suicide, to be seen as a positive community member, and to serve the community. This indicates a theoretical support of voluntary storage – and the map - as a suicide prevention resource and a general positive view of those who participate in it. More targeted communication and media campaigns disseminating and encouraging participation in these programs is warranted. Additionally, to increase participation, clarification surrounding barriers to participation in the map and providing storage should be addressed. Unfortunately, despite seeing providing storage as an important service to their community, the majority of those who responded to our survey indicated that they agreed with the statement: “I worry that the people promoting gun storage maps are anti-gun rights”. This concern should be addressed by both clarifying that this program is a voluntary one. Additionally, research suggests that using culturally sensitive language, a-political suicide prevention strategies and participatory research and community-involved program planning can improve relationships and trust between public health and firearm-owning communities.(C. Barber et al., 2017; Betz et al., 2021; Polzer et al., 2020).

Importantly, the results from our hypothesis tests indicate avenues for policy change to encourage out-of-home storage. The results indicate particularly influential changes would include waivers of liability or “Good Samaritan” protections for returning the firearm to someone who later harms themself or others, and also for refusing to return the gun to the owner if there is reason for concern. In 2022, Washington state passed a law that included some civil liability protection for firearm retailers who engage in temporary emergency transfers for storage (Dean, n.d.). What liability protections under specific circumstances this law covers or how it may be used, however, is unclear. Indelible laws for retailers/ranges may encourage more retailers/ranges to provide storage. Among those who have ever provided storage, only 14% of our sample indicated ever declining to return a firearm that was being temporarily stored in their facility due to safety concerns; therefore, legal clarification surrounding refusal of return may increase the likelihood for retailers/ranges to provide temporary storage. However, this raises the issue of staff training to recognize potential suicidality/suicidal ideation, refuse to return, and decide how to proceed with storage. Insurance providers, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (the federal agency that regulates the firearms industry) and firearm retailers/ranges could work in conjunction with public health to clarify acceptable business practices, liability issues related to specific circumstances/concerns and provide waivers where applicable.

Limitations

The sampling frame used may be incomplete if businesses lack an online presence. However, it is unlikely that retailers/ranges would offer storage or be found by someone who wanted to store their firearms away from their home without an online presence. We report a response rate of 25.1% which is not dissimilar compared to other surveys among the same population; (Pierpoint et al., 2019; Tung et al., 2019) locations responding to our survey may be more supportive of voluntary, temporary storage. The generalizability of these findings may only be applicable to the two states sampled or other retailers/ranges that are similar to those who we surveyed. It is possible the person who filled out the survey was unaware or misinformed about the businesses policies on firearm storage, however as most of our surveys were completed by the owner/co-owner/manager or both (94.1%) results likely represent the business policies in practice. Lastly, future studies should examine if the duration of requested storage could potentially influence if locations were able to offered temporary storage,

A limitation of voluntary out of home storage programs are that voluntary storage does not necessarily prevent the firearm owner from retrieving their firearms from the storage site or from purchasing another firearm from any gun store. Future studies should examine the efficacy of voluntary storage programs on preventing suicide.

CONCLUSIONS

Some firearm retailers/ranges are already providing voluntary, temporary out-of-home storage to the firearm owning community, but this may be at a lower rate than are hypothetically interested in providing such a service. As a trusted resource to the firearm owning community, these businesses are an untapped suicide prevention resource. Specific waivers for liability concerns and guidance from regulatory agencies may increase the participation in suicide prevention firearm storage map programs and increase the number of retailers/ranges that are willing to provide storage. Providing out-of-home storage by retailers/ranges is an important component of lethal means safety programs and may decrease the rate of suicide in the communities where such a service is provided and publicized.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

One third of retailers/ranges in Colorado and Washington currently offer temporary, voluntary out-of-home storage of firearms.

The majority of survey participants had not heard of the Colorado/Washington gun storage map

Liability waivers would most influence their decisions about whether to start or continue providing temporary, voluntary storage of firearms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Emma Gause, John C. Fortney, Ayah Mustafa

DISCLOSURE OF FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (R61MH125754). NIH/NHLBI Grant Number K23 HL153892 (Knoepke), and American Heart Association Grant Number 18CDA34110026 (Knoepke). The contents of this work are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official funder views. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Abdallah HO, Zhao C, Kaufman E, Hatchimonji J, Swendiman RA, Kaplan LJ, Seamon M, Schwab CW, & Pascual JL (2021). Increased Firearm Injury During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Hidden Urban Burden. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 232(2), 159–168.e3. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allchin A, Chaplin V, & Horwitz J (2019). Limiting access to lethal means: Applying the social ecological model for firearm suicide prevention. Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 25(Suppl 1), i44–i48. 10.1136/injuryprev-2018-042809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Bandel SL, & Bond AE (2021). The Association of Suicidal Ideation With Firearm Purchasing During a Firearm Purchasing Surge. JAMA Network Open, 4(10), e2132111. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber C, Frank E, & Demicco R (2017). Reducing Suicides Through Partnerships Between Health Professionals and Gun Owner Groups-Beyond Docs vs Glocks. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(1), 5–6. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber CW, & Miller MJ (2014). Reducing a Suicidal Person’s Access to Lethal Means of Suicide. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3), S264–S272. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz ME, Harkavy-Friedman J, Dreier FL, Pincus R, & Ranney ML (2021). Talking About “Firearm Injury” and “Gun Violence”: Words Matter. American Journal of Public Health, 111(12), 2105–2110. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz ME, Rooney LA, Barnard LM, Siry-Bove BJ, Brandspigel S, McCarthy M, Simeon K, Meador L, Rivara FP, Rowhani-Rahbar A, & Knoepke CE (2022). Voluntary, temporary, out-of-home firearm storage: A qualitative study of stakeholder views. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 10.1111/sltb.12850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiorno DM, Kramer EN, Booty MD, & Crifasi CK (2021). Development of an online map of safe gun storage sites in Maryland for suicide prevention. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 33(7), 626–630. 10.1080/09540261.2020.1816927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Russell A, Runyan C, Betz ME, Tung G, Brandspigel S, & Novins DK (2019). Law Enforcement Agencies’ Perceptions of the Benefits of and Barriers to Temporary Firearm Storage to Prevent Suicide. American Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 285–288. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi TL, Ayers JW, Dredze M, Suplina N, & Burd-Sharps S (2020). Collateral Crises of Gun Preparation and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Infodemiology Study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2). 10.2196/19369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PM, Losman E, Roche JS, Malani PN, Kullgren JT, Solway E, Kirch M, Singer D, Walton MA, Zeoli AM, & Cunningham RM (2022). Firearm ownership, attitudes, and safe storage practices among a nationally representative sample of older U.S. adults age 50 to 80. Preventive Medicine, 156, 106955. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.106955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, & Lou D (2020). Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 36–38. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, & Robinson E (2021). Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 603–609. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B. (n.d.). ENGROSSED SECOND SUBSTITUTE HOUSE BILL 1181 as passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate on the dates hereon set forth. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gun Storage Map. (2019, July 29). Colorado Firearm Safety Coalition. https://coloradofirearmsafetycoalition.org/gun-storage-map/

- Helmore E. (2021, May 31). US gun sales spiked during pandemic and continue to rise. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/may/31/us-gun-sales-rise-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- Kelly T, Brandspigel S, Polzer E, & Betz ME (2020). Firearm Storage Maps: A Pragmatic Approach to Reduce Firearm Suicide During Times of Risk. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(5), 351–353. 10.7326/M19-2944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, … Hendin H (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA, 294(16), 2064–2074. 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NW, 1615 L. St, Suite 800Washington, & Inquiries, D. 20036USA202-419-4300 ∣M.−857-8562 ∣ F.−419-4372 ∣ M. (n.d.). The demographics and politics of gun-owning households. Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/07/15/the-demographics-and-politics-of-gun-owning-households/ [Google Scholar]

- Pierpoint LA, Tung GJ, Brooks-Russell A, Brandspigel S, Betz M, & Runyan CW (2019). Gun retailers as storage partners for suicide prevention: What barriers need to be overcome? Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 25(Suppl 1), i5–i8. 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polzer E, Brandspigel S, Kelly T, & Betz M (2020). “Gun shop projects” for suicide prevention in the USA: Current state and future directions. Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention. 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer RS, & Miller TR (2000). Suicide acts in 8 states: Incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. American Journal of Public Health, 90(12), 1885–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studdert DM, Zhang Y, Swanson SA, Prince L, Rodden JA, Holsinger EE, Spittal MJ, Wintemute GJ, & Miller M (2020). Handgun Ownership and Suicide in California. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(23), 2220–2229. 10.1056/NEJMsa1916744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung GJ, Pierpoint LA, Betz ME, Brooks-Russell A, Brandspigel S, & Runyan CW (2019). Gun Retailers’ Willingness to Provide Gun Storage for Suicide Prevention. American Journal of Health Behavior, 43(1), 15–22. 10.5993/AJHB.43.1.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton T, & Stuber J (2020). Firearm Retailers and Suicide: Results from a Survey Assessing Willingness to Engage in Prevention Efforts. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 50(1), 83–94. 10.1111/sltb.12574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington Firearm Safe Storage Map—Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://hiprc.org/firearm/firearm-storage-wa/

- WISQARS (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System)∣Injury Center∣CDC. (2020, July 1). https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, van Heeringen K, Arensman E, Sarchiapone M, Carli V, Höschl C, Barzilay R, Balazs J, Purebl G, Kahn JP, Sáiz PA, Lipsicas CB, Bobes J, Cozman D, Hegerl U, & Zohar J (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.