Abstract

Background

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) has been associated with the development and progression of various malignant tumors. However, its roles and the mechanisms underlying its involvement in ovarian cancer (OC) peritoneal metastasis remain unclear.

Methods

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were conducted to determine the expression profiles, potential functionalities, and underlying mechanisms of PTX3 within the context of OC. To assess the proliferative response of OC cells, we utilized both EdU (5-ethynyl-2’ -deoxyuridine) and CCK8 assays. The role of PTX3 in facilitating cell migration and invasion was quantified through the use of Transwell assays. The protein expression levels were meticulously analyzed via Western blotting. Furthermore, to explore the interactions between proteins, we conducted immunofluorescence (IF) staining and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments. To determine the factors responsible for the upregulation of PTX3, we performed both coculture and suspension assays, providing a comprehensive approach to understanding the regulatory mechanisms involved.

Results

This study confirmed, for the first time, that the expression of PTX3 in OC metastatic lesions is greater than that in primary lesions and that tumor cells with high PTX3 expression have greater metastatic ability. PTX3 can activate the EMT and NF-κB signaling pathways in OC cells and can interact with the TLR4 and CD44 receptors in OC cells. Additionally, PTX3’s modulation of the EMT and NF-κB pathways is partially dependent on its interaction with TLR4. Furthermore, this study revealed the intercellular regulatory network related to PTX3 in OC cells via bioinformatic analysis. High levels of PTX3 in OC cells potentially enhance the attraction of dendritic cells (DCs) and CD4 + T cells while diminishing the recruitment of B cells and CD8 + T cells. Finally, this study indicated that PTX3 upregulation was driven by multiple factors, including specific transcription factors (TFs) and modifications within the tumor microenvironment (TME).

Conclusions

Our research revealed the contribution of PTX3 to the peritoneal dissemination process in OC patients, identifying a novel potential biomarker and therapeutic target for this disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13048-024-01558-2.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Pentraxin 3, Peritoneal metastasis, Single-cell RNA sequencing, Tumor immunity

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most fatal gynecological malignancy; it often starts without noticeable symptoms and is typically diagnosed at an advanced stage when it has already disseminated widely in the peritoneal cavity [1, 2]. High-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), the predominant and most aggressive histological subtype of OC, contributes to approximately 70–80% of the deaths associated with OC [3, 4]. Peritoneal metastasis is the primary route of OC dissemination and is a major cause of patient mortality. The surgical challenges associated with the removal of extensive peritoneal metastases and the chemoresistance of OC cells within these metastatic lesions are the roots of tumor recurrence [5]. Therefore, peritoneal metastasis has become a major bottleneck in the treatment of OC, highlighting the crucial and immediate necessity for comprehensive studies on the molecular underpinnings of OC peritoneal metastasis and the discovery of viable therapeutic targets. Such effort is imperative for improving the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of patients with OC.

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) is an inaugural member of the long pentraxin family [6] and was initially considered a pattern-recognition receptor. It can be found in bodily fluids and acts as an essential element of the innate immune response, facilitating the recognition of pathogens, adjusting inflammatory responses and facilitating the remodeling of tissue architecture [7]. Notably, PTX3 plays a regulatory role in various malignant biological behaviors of OC, encompassing oncogenesis, the promotion of new blood vessel formation, and the modulation of immune responses, which are intimately connected with the prognostic trajectory of patients [8–10]. In terms of the underlying mechanisms, preliminary studies suggest that PTX3 exerts its effects through the receptor TLR4 or CD44 [11–13]. Regarding PTX3 and OC, patients with OC who exhibit high PTX3 expression tend to have a worse prognosis [14]. However, the impact of PTX3 on OC and the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Additionally, PTX3 plays a role in modulating the immunological microenvironment. Most of the current evidence underscores its significant role in driving M2 polarization in macrophages [15–17]. However, the specifics of PTX3’s interactions with other immune cell types and their potential effects still need thorough investigation. Immune cells are pivotal within the TME because of their capacity to regulate diverse signaling pathways and trigger corresponding immune reactions [18]. Enhanced infiltration by CD8 + T cells and memory B cells within the TME correlates with an improved prognosis in OC patients, while a greater presence of tumor-associated macrophages and regulatory T cells is linked to a less favorable outcome in those with OC [19–21]. Changes in the TME may also upregulate the expression of PTX3. Mesothelial cells cover the serous surface of all organs in the peritoneal cavity, including the stomach, intestine, greater omentum and entire peritoneum [22]. Tumor cells disseminating to peritoneal lesions first interact with mesothelial cells [23]. Above all, the functions and modes of action of PTX3 in the peritoneal dissemination of OC have yet to be elucidated, and the factors that induce the upregulation of PTX3 expression also require further investigation.

Therefore, in this study, we initially examined the expression characteristics of PTX3 via single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis and immunohistochemistry (IHC) and confirmed that PTX3 expression gradually increases with the progression of OC. Moreover, our findings revealed that elevated PTX3 expression enhances OC cell proliferation, migration and invasion. We also clarified the role of PTX3 in activating the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathways. Furthermore, PTX3 was shown to co-localize with the OC cell receptors TLR4 and CD44. Mechanistically, the inhibition of TLR4 can partially reverse the effects induced by PTX3 overexpression We also analyzed the regulatory network of high-PTX3 OC cells by assessing immune infiltration and cell communication in the TME. Finally, we have also preliminarily discovered that the activation of transcription factors (TFs), like NFKB1, and changes in the TME, especially cell suspension rather than adherent cultures simulating ascitic conditions, may contribute to the upregulation of PTX3 expression in OC. Our aim was to delineate the pivotal role of PTX3 in OC peritoneal metastasis and its underlying molecular mechanism. We hypothesize that PTX3 could be a novel potential biomarker and be treatment target for OC diagnosis and intervention.

Methods

Clinical sample acquisition

Tissue samples from 44 primary OC patients diagnosed at the Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (Shenyang, China) between 2012 and 2018 and their matched peritoneal metastatic lesions were obtained for immunohistochemistry assay (Additional file 1. Table S1_Clinical_Information). All patients were histologically confirmed to have OC, and patients with other malignant tumors were excluded. The histological diagnosis, grading and staging of OC followed the criteria set by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University and adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2023PS521K).

Cell lines

SKOV3: This cell line was derived from the ascites of a patient with ovarian adenocarcinoma. In our study, SKOV3 was used for PTX3 overexpression experiments. CAOV3: Originating from the primary tumor of a patient with ovarian adenocarcinoma, CAOV3 was employed for both PTX3 knockdown and overexpression experiments. OVCAR3: Established from the malignant ascites of a patient with ovarian adenocarcinoma, OVCAR3 was used for PTX3 knockdown. HOSE: Derived from normal human ovarian surface epithelium, the HOSE cell line served as an important control for identifying PTX3 expression levels.

Dataset analysis

The processed scRNA-seq dataset of 14 specimens from 10 patients with advanced OC was download from Mendeley Data (10.17632/rc47y6m9mp.1). The workflow was described in detail in the original article [24]. Briefly, data analysis was conducted on these OC samples using the “Seurat” R software package, which was utilized for cell filtering, normalization, dimensionality reduction, and clustering. The Harmony algorithm was employed for the integration of multisample data to eliminate batch effects. The “UCell” R package was used to estimate the activities of the Hallmark pathways from the MsigDB [25]. CellPhoneDB was used to investigate interactions between tumor cells with varying levels of PTX3 expression and diverse cell types, focusing on receptor ligand signaling cascades [26]. The pySCENIC tool in Python was used to analyze the activity of each TF in each cell. To identify the major TFs in high-PTX3-expression tumor cells, the calcRSS function within the SCENIC R package was used in combination with the RSS method for analysis. PySCENIC analysis builds gene regulatory networks within single cells, with the regulated genes collectively referred to as regulons or regulatory units. The connections between different regulons are determined by the specificity index of each individual regulon. Regulons with a high specificity index are capable of coregulating downstream genes, potentially contributing to the biological functions of cells in the TME in a collective way [27, 28]. This approach has been validated as an effective strategy for identifying cell-type-specific TFs [27].

TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/) was utilized to explore the association between PTX3 transcription levels and immune infiltration in OC [29]. TISIDB (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/) was used to assess the association of PTX3 with immune stimulatory factors, immune inhibitory factors and chemokines (or receptors) in OC [30].

Cell culture

The human OC cell lines SKOV3, CAOV3, OVCAR3, and HMrSV5 were obtained from Pro-cell Life Technology (Wuhan, China) and from the BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing, China), while the HOSE cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). SKOV3, OVCAR3, and HOSE cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium, whereas CAOV3 and HMrSV5 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA). Both media were supplemented with 10% FBS (Clark, Australia), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Additionally, a TLR4 inhibitor (Stepharine, HY-N9347, MCE, USA) was used in the cell culture system to validate the potential receptor of PTX3. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Sphere formation experiment

In the sphere formation experiment, Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) 6-well plates (Model: 3471, Corning, USA) were used for cell seeding. The cell suspension was gently added under sterile conditions, with the cell density optimized to an appropriate cell density per well. The culture plate was gently swirled to ensure that the cells were evenly distributed and did not adhere to the well walls. Subsequently, the cells were incubated in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for three days. During incubation, the stability of the culture medium was maintained, and medium changes were avoided to prevent disruption of sphere formation. After the three-day incubation, sphere formation was observed using Cytation5 system.

Quantitative real-time PCR(qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from OC cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA for RT-qPCR was synthesized using a PrimeScript RT Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Japan). Gene expression was calculated relative to that of GAPDH, and the 2-ΔΔCt method was used to determine transcript levels [26]. The primers used for PTX3 (forward:5’-TGCCGGCAGGTTGTGAA-3’, reverse:5’-ACATCTGTGGCTTGACCCA-3’) and GAPDH (forward:5’-GAPDHTGAACGGGAAGCTCACTGG-3’, reverse: 5’-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3’) were designed by Sangon Biotech.

Cell transfection

PTX3 transient plasmids (sequence si-PTX3#A: 5’-GGGTGGTGGCTTTGATGAAAC-3’. sequence si-PTX3#B: 5’-GGGATAGTGTTCTTAGCAATG-3’) and a control siRNA (sequence:5’-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3’) were obtained from GeneChem (Shanghai, China). A PTX3-expressing plasmid was generated by Hanbio (Shanghai, China). A total of 3 × 10^5 cells were plated per well in 6-well plates. The cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, CA) following the manufacturer′s instructions. For each transfection, 0.75 µg/ml of plasmid was mixed with 2 ml of culture medium and added to a 6-well cell culture plate. The cells were harvested for subsequent experiments 48 h after transfection. Specific silencing or overexpression of the targeted gene was verified by Western blotting.

Transwell assay

For the Transwell migration assay, cells were seeded in the upper chamber (Corning, NY) for 24 h. For invasion assays, Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was applied to the upper chamber, and invasion was allowed to progress for 24 h. Cells that migrated through the membrane were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined under a Leica DM3000 microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) in five random fields. Cell counting was performed using Image-Pro 6.0.

Cell proliferation assay

After 48 hours of transfection, OVCAR3 (3 × 10^3/well), SKOV3 cells (4 × 10^3/well) and CAOV3 (2 × 10^3/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate for a CCK-8 assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) to evaluate cell proliferation via OD450. EdU (5-ethynyl-2’ -deoxyuridine) experiments were conducted using an EdU kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), following the supplier’s protocol. Cells were seeded and allowed to adhere overnight. EdU was then added to the culture medium for 2 h, facilitating incorporation into newly synthesized DNA. After incubation, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton X-100. The EdU was detected using a fluorescent azide through a click chemistry reaction. Imaging was performed with inverted microscope.

Western blot analysis

Protein levels were measured utilizing a BCA kit (Takara, Japan). Following SDS-PAGE separation (KeyGEN, China), proteins were blotted onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, MA). These membranes were subsequently blocked using 5% skim milk for two hours at ambient temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. PTX3 (ab90806, Abcam, USA), E-cadherin (#40860, Signalway Antibody, USA), N-cadherin (#48495, Signalway Antibody, USA), vimentin (10366-1-AP, Protein Tech, China), NF-κB (8242, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), phospho-NF-κB p65 (3033, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), β-tubulin (#2146, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), CD44 (#3570, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), and TLR4 (19811-1-AP, Proteintech, China) were used. This mixture was subsequently incubated with anti-mouse (ZB2305, ZSGB-BIO, China) and anti-rabbit (ZB2301, ZSGB-BIO, China) secondary antibodies for 1 h at 25 °C and imaged with GelCapture software (DNR Bio-Imaging Systems, Jerusalem, Israel).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Cell lysates were prepared in NP-40 buffer (Keygen, Nanjing, China). The cell lysates were incubated overnight with rotation at 4 °C with rat anti-IgG (A7031, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-IgG (P2179S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), CD44 (15675-1-AP, Proteintech, China), and PTX3 (ab90806, Abcam, USA). Subsequently, the samples were incubated with Protein A/G agarose (P2179S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 3 h with rotation. The immunoprecipitated complexes were separated using SDS-PAGE. Finally, SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were performed.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay

The OC specimens were surgically resected and fixed in 10% neutral formalin after removal. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on consecutive 4 μm sections placed on slides using a single staining protocol. After deparaffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieval, the tissues were blocked with 5% BSA before being incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C and incubated for 30 min with biotinylated secondary antibodies at 37 °C. Color development was achieved using a Vector DAB substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, CA), and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and lithium carbonate. Images were captured with a Leica DM3000 microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Staining intensity and cell proportions were evaluated, generating expression scores ranging from 0 to 12, calculated by multiplying the intensity rating (0 to 3) and the percentage rating (1 to 4) for each sample.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

The plated cells were fixed in methanol at -20 °C for 20 min and blocked using 5% BSA (Sigma, MA). This was followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies and a 1-hour incubation with secondary antibodies. Imaging was performed with inverted microscope.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 8.0.2. The data are shown as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA test, Student’s t-test, Log-rank test, Spearman and Pearson correlations and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, were used as appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

PTX3 expression is upregulated during OC peritoneal metastasis

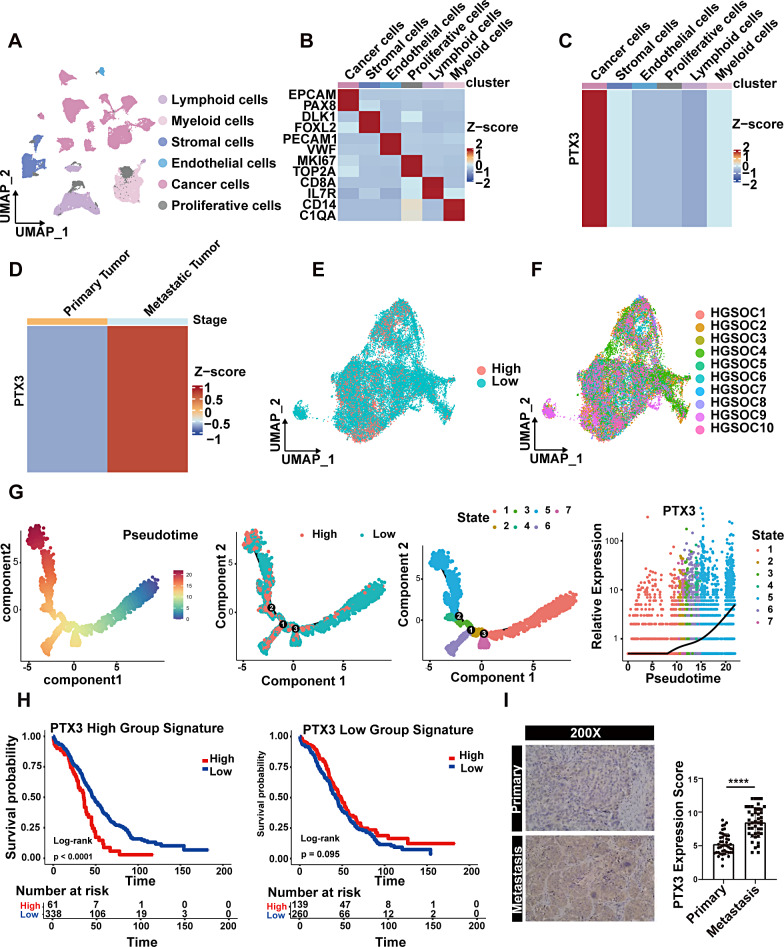

Single-cell sequencing data from 14 advanced HGSOC samples, encompassing both primary and peritoneal metastatic lesions, were analyzed from 10 patients. A total of 66,693 cells were included. Unsupervised clustering of all cells resulted in the identification of six clusters, including tumor cells (EPCAM, PAX8), stromal cells (DLK1, FOXL2), endothelial cells (PECAM1, VWF), proliferating cells (MKI67, TOP2A), lymphoid cells (CD8A, IL7R), and myeloid cells (CD14, C1QA) with specific marker genes for each cell subtype (Fig. 1A-B). Compared to other cell subtypes, tumor cells exhibited higher PTX3 expression, as revealed by our findings (Fig. 1C). In tumor cells, PTX3 expression was greater in peritoneal metastatic lesions than in primary lesions (Fig. 1D). Therefore, we investigated the functional differences between primary tumor cells exhibiting high and low PTX3 expression. We extracted tumor cells from primary lesions and divided them into two groups based on PTX3 expression (Fig. 1E) and found that tumor cells with high PTX3 expression were present in all patient samples (Fig. 1F). To simulate the metastatic process of tumor cells, we performed a pseudotime trajectory analysis using Monocle analysis and found that tumor cells were distributed in seven states and that tumor cells with high PTX3 expression were enriched mainly in state 5, which was located at the end of the pseudotime analysis (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, we found that the signature genes of tumor cells with high PTX3 expression were correlated with poor prognosis in OC patients, while the signature genes of tumor cells with low PTX3 expression were not significantly associated with OC patient prognosis (Fig. 1H, Additional file 2: Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics and protein expression of PTX3 at the single-cell level in OC tissue. (A) UMAP plot showing the clustering of all 66,693 cells, with different colors representing distinct cell subgroups. (B) Heatmap displaying the expression levels of known marker genes in each cell subgroup. (C) Heatmap showing the expression of PTX3 in different cell subgroups. (D) Heatmap demonstrating the expression of PTX3 in tumor cells from primary and metastatic lesions. (E) UMAP used for dimensionality reduction and visualization of tumor cells with high or low PTX3 expression. (F) UMAP plot displaying the patient origins of tumor cells, with different colors representing different samples. (G) Pseudotime trajectory analysis based on PTX3 expression. (H) Prognostic analysis based on PTX3 related gene features. (I) IHC detection of PTX3 expression levels in primary OC lesions and paired peritoneal metastatic lesions. Data are presented as mean ± SD; **** P < 0.0001

To further validate PTX3 expression, we collected sections from primary lesions and paired peritoneal metastatic lesions of OC for IHC staining. IHC results showed that there was a notably higher level of PTX3 expression in peritoneal metastatic lesions than in primary lesions (Fig. 1I).

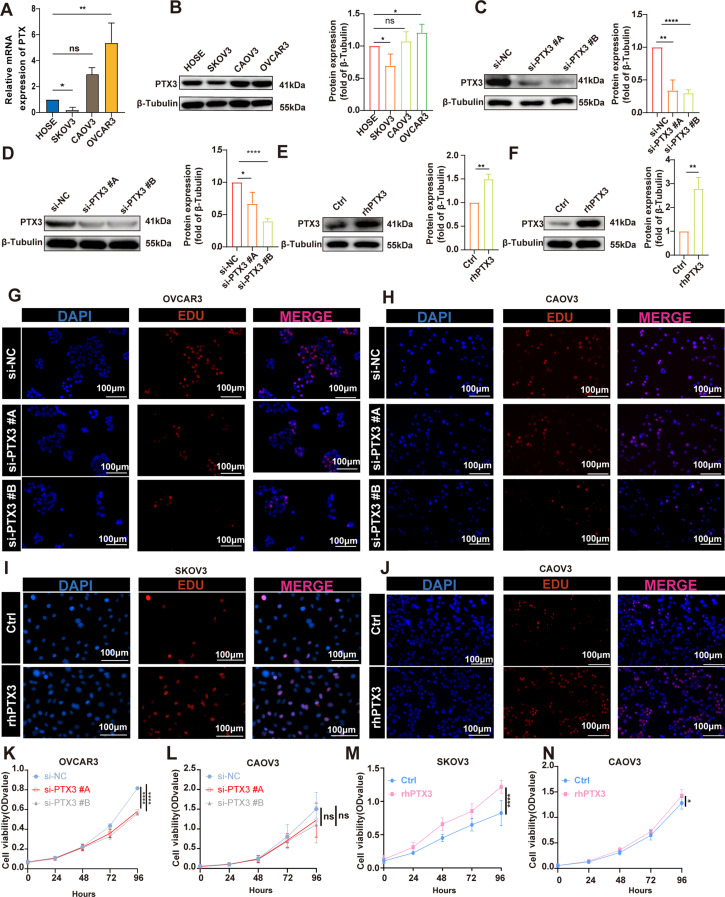

PTX3 can enhance the proliferation, migration and invasion of OC cells

To evaluate PTX3 expression in OC cell lines, we assessed both PTX3 mRNA and protein levels in normal ovarian epithelial cells (HOSE) and three OC cell lines (SKOV3, CAOV3, and OVCAR3). Quantitative real-time PCR and Western blotting revealed high PTX3 expression in OVCAR3 cells, while SKOV3 cells exhibited minimal PTX3 expression. CAOV3 cells showed moderate PTX3 expression (Fig. 2A-B).

Fig. 2.

PTX3 expression and function in OC cells. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR detection of PTX3 gene expression in ovarian epithelial cells and OC cells. (B) Western blot detection of PTX3 protein expression in ovarian epithelial cells and OC cells (left). Quantitative analysis of PTX3 (right). (C, D) Western blot detection of PTX3 protein expression in control and PTX3 knockdown OVCAR3 and CAOV3 cells (left). Quantitative analysis of PTX3 (right). (E, F) Western blot showing PTX3 protein expression in control and PTX3 overexpression SKOV3 and CAOV3 cells (left). Quantitative analysis of PTX3 (right). (G-J) EDU assay detecting the effects of PTX3 knockdown and overexpression on the proliferation of OC cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. (K-L) CCK8 assay detecting the effects of PTX3 knockdown and overexpression on the proliferation of OC cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD; ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

To explore the functional role of PTX3 in OC cells, we knocked down PTX3 in OVCAR3 and CAOV3 cells. Additionally, we overexpressed PTX3 in SKOV3 and CAOV3 cells. Western blotting revealed successful knockdown of PTX3 in OVCAR3 and CAOV3 cells and overexpression of PTX3 in SKOV3 and CAOV3 cells (Fig. 2C-F). The EDU proliferation assay results showed that knockdown of PTX3 partially inhibited the proliferation of OC cells, while overexpression of PTX3 promoted the proliferation of OC cells (Fig. 2G-J). Furthermore, the CCK8 assay also showed similar results, where knockdown of PTX3 suppressed the viability of OC cells to a certain extent, while overexpression of PTX3 promoted the viability of OC cells (Fig. 2K-N). These findings suggest that PTX3 is pivotal in modulating the proliferation of OC cells.

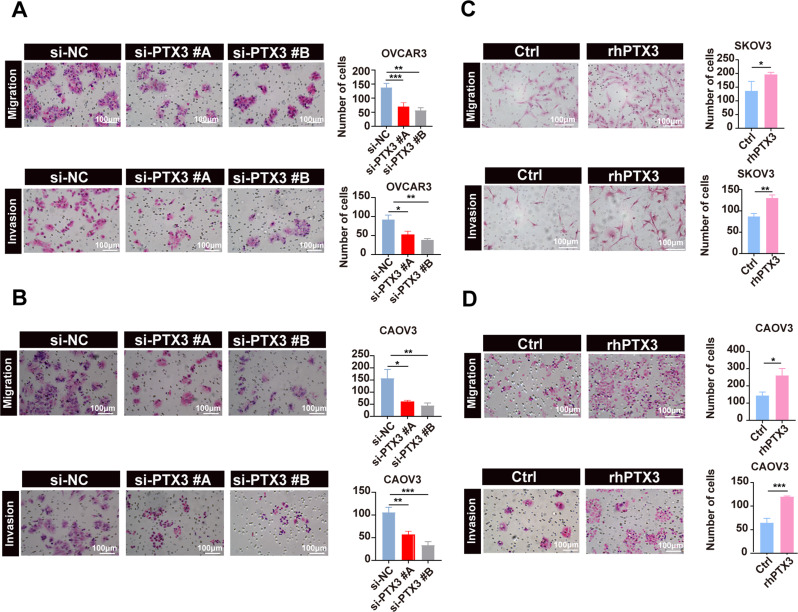

Finally, Transwell assay additionally indicated PTX3 knockdown significantly impaired the migration and invasion of OVCAR3 and CAOV3 cells relative to that of control cells (Fig. 3A-B), while PTX3 overexpression substantially enhanced these abilities in SKOV3 and CAOV3 cells. This evidence underscores the vital influence of PTX3 on the metastatic behavior of OC cells (Fig. 3C-D).

Fig. 3.

Biological functions of PTX3 in OC Cells. (A, B) Representative images (left) and quantitative analysis (right) of the effects of PTX3 knockdown on the migration and invasion of OC cells in Transwell assays. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C, D) Representative images (left) and quantitative analysis (right) of the effects of PTX3 overexpression on the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells in Transwell assays. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

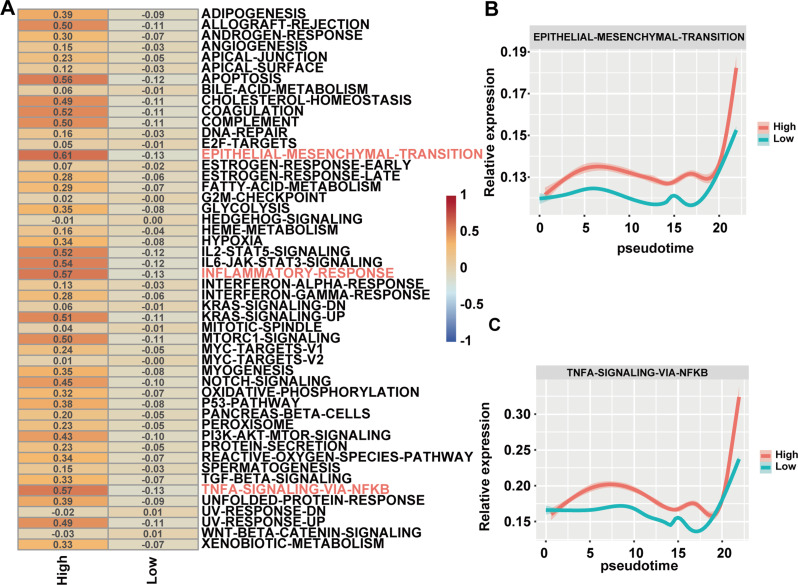

Single-cell sequencing reveals PTX3 involvement in EMT and NF-kB signaling pathways

The functional score analysis revealed that OC cells with high PTX3 expression activated more tumor-related signaling pathways, among which the EMT, NF-kB and inflammatory response signaling pathways were significantly activated (Fig. 4A). Further pseudotime analysis revealed that over time, tumor cells overexpressing PTX3 significantly activated the EMT and NF-κB signaling pathways at the simulated endpoint, with activation levels notably higher than those in tumor cells with low PTX3 expression. Additionally, in the early pseudotime, PTX3 high-expressing cells showed higher EMT and NF-κB signaling pathway scores. This suggests that these cells have the potential to acquire metastasis-related malignant phenotypes early in pseudotime, which is crucial for the initiation of metastasis (Fig. 4B-C).

Fig. 4.

Single-Cell RNA sequencing pathway enrichment analysis comparing PTX3-high and PTX3-low OC cells. (A) Ucell analysis displaying the functional score of the PTX3-high expression group and the PTX3-low expression group, with rows representing activated pathways and columns representing grouping. (B, C) Dynamic changes in the EMT and NF-κB signaling pathways along the pseudotime differentiation trajectory of tumor cells with different PTX3 expression

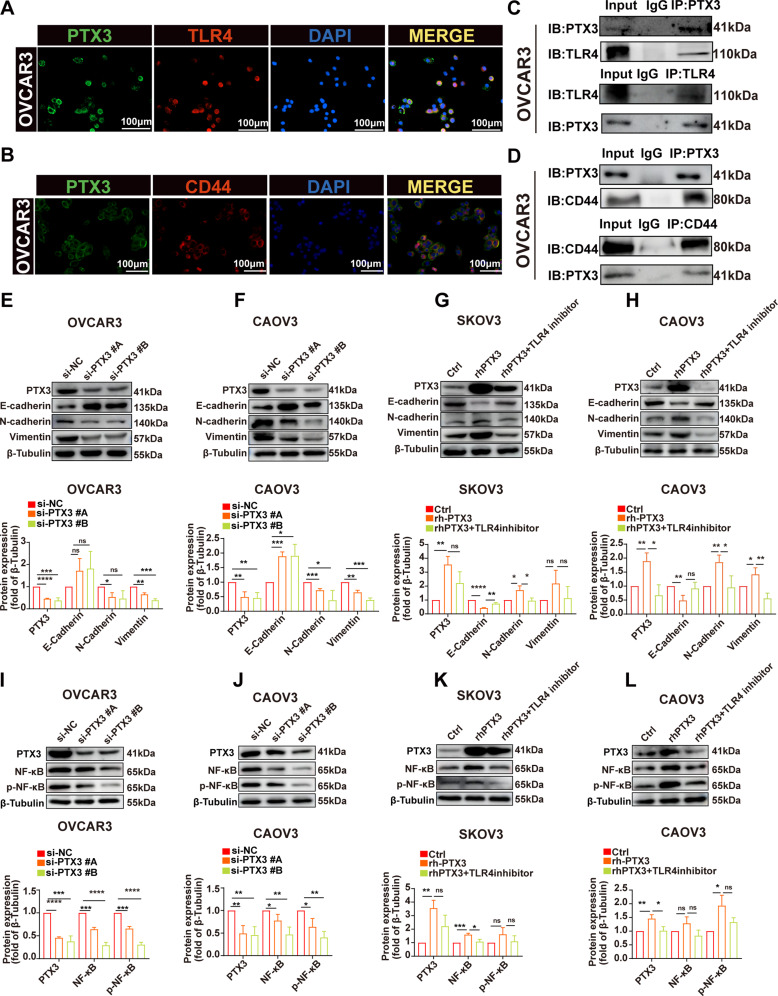

PTX3 modulates EMT and NF-κB via TLR4

Previous studies have demonstrated that PTX3 interacts with TLR4, promoting cancer progression in various types including breast cancer [11] and melanoma [12]. Additionally, research has shown that the interaction between PTX3 and CD44 facilitates the progression of breast cancer [13]. These findings led us to investigate whether similar interactions occur in the context of our study, aiming to understand their implications for OC progression and treatment.

IF analysis revealed the colocalization of the PTX3 protein with TLR4 in OVCAR3 cell line (Fig. 5A). Co-IP experiments confirmed the binding of PTX3 to membrane-bound TLR4 in the cell line (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, through IF analysis, we evaluated the colocalization of PTX3 with CD44 in OVCAR3 cell line (Fig. 5B). Similarly, Co-IP experiments demonstrated the binding of PTX3 to membrane-bound CD44 in the same cell line (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

PTX3 activates EMT and NF-κB pathways in OC cells, partially inhibited by TLR4. (A, B) IF staining results of OVCAR3 cells, showing PTX3 (green), TLR4 (red), CD44 (red), and the nuclear marker DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm. (C, D) Co-IP detected the interaction of PTX3 with TLR4 and CD44 in OVCAR3 cells. (E, F) Representative Western blot images showing the expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin after PTX3 knockdown (upper) Quantitative analysis of the respective proteins (lower). (G, H) Representative Western blot images showing the expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin after PTX3 overexpression and after PTX3 overexpression with the addition of TLR4 inhibitor (upper). Quantitative analysis of the respective proteins (lower). (I, J) Representative Western blot images showing the expression of NF-κB and p-NF-κB in OC cells after PTX3 knockdown (upper). Quantitative analysis of the respective proteins (lower). (K, L) Representative Western blot images showing the expression of NF-κB and p-NF-κB in OC cells after PTX3 overexpression and after PTX3 overexpression with the addition of TLR4 inhibitor (upper). Quantitative analysis of the respective proteins (lower). Data are presented as mean ± SD; ns P > 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001

To further validate the single-cell sequencing results concerning PTX3’s role in activating EMT and NF-κB signaling pathways, and to preliminarily investigate whether this effect is partially mediated through TLR4, we conducted in vitro experiments using three OC cell lines: OVCAR3, CAOV3, and SKOV3. Our findings revealed that in the OVCAR3 and CAOV3 cell lines, PTX3 knockdown moderately suppressed EMT pathway activity. This was demonstrated by the elevated levels of the EMT marker E-cadherin and the reduced levels of N-cadherin and vimentin (Fig. 5E-F). Conversely, in the SKOV3 and CAOV3 cell lines, PTX3 overexpression partially activated the EMT pathway, as evidenced by the reduction in E-cadherin expression and increase in N-cadherin and vimentin expression (Fig. 5G-H). Additionally, in the OVCAR3 and CAOV3 cell lines, PTX3 knockdown somewhat diminished the activity of the NF-κB pathway, as demonstrated by the decreases in both total NF-κB p65 and phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (p-NF-κB p65) (Fig. 5I-J). In the SKOV3 and CAOV3 cell lines, PTX3 overexpression modestly enhanced NF-kB pathway activity, as demonstrated by increased levels of NF-kB p65 and p-NF-kB p65 (Fig. 5K-L). Furthermore, we employed a TLR4 inhibitor to investigate whether PTX3’s effects are mediated through TLR4. As expected, the inhibition of TLR4 partially reversed the effects caused by PTX3 overexpression (Fig. 5G-H and K-L). In conclusion, our in vitro experiments demonstrated that PTX3 participates in EMT and NF-κB pathways, at least partially, through TLR4.

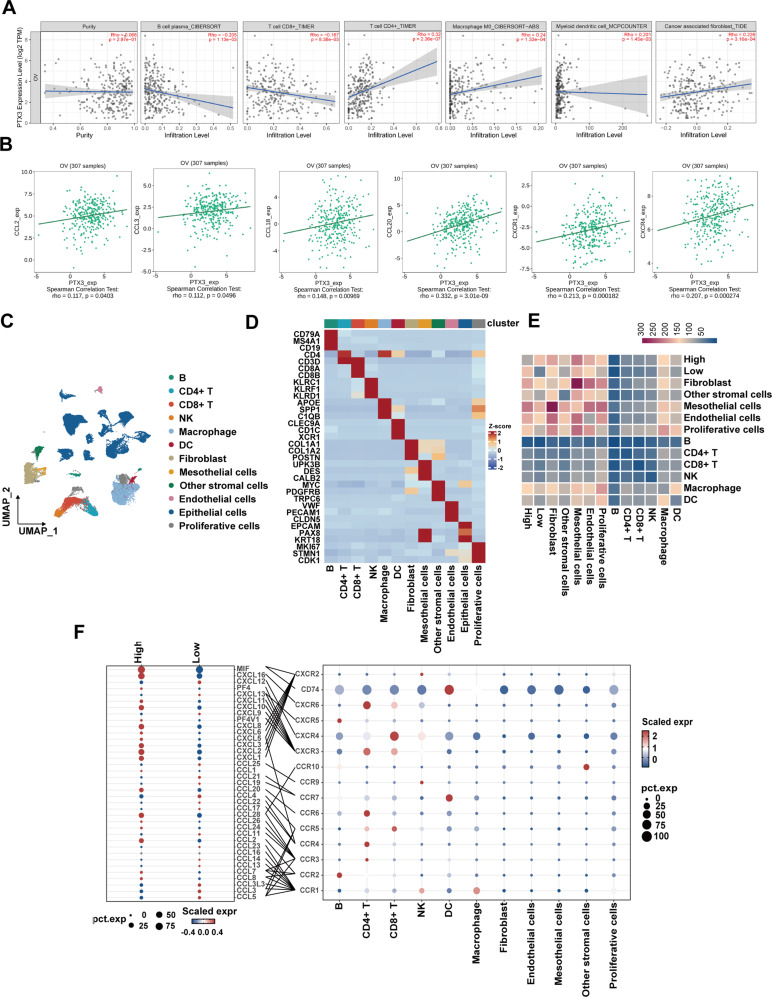

PTX3 expression correlated with immune infiltration and high-PTX3 OC cells exhibited stronger cell communication with TME cells

Immune infiltration significantly influences the metastatic process in OC. To comprehensively assess the association between the expression of PTX3 and immune cell infiltration within the TME of OC patients, we utilized TIMER2.0 for our analysis. The results indicated a negative correlation between PTX3 expression and the presence of B cells and CD8 + T cells. In contrast, PTX3 expression was positively associated with the infiltration of CD4 + T cells, macrophages, DCs, and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (Fig. 6A). Subsequently, our research extended the examination of the association between PTX3 expression and diverse immune characteristics within the TISDB database. The analysis revealed a significant correlation between PTX3 levels and the occurrence of selected chemokines and their receptors, including CCL2, CCL3, CCL18, CCL20, CXCR1, and CXCR4, in OC (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Association between PTX3 and immune infiltration in OC. (A) Correlation between PTX3 expression and infiltration levels of B cells, CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, macrophage M0, myeloid dendritic cells, and CAFs in OC, available from the TIMER2.0 database. (B) Correlation between PTX3 expression and chemokines and chemokine receptors in OC provided in TISIDB database. (C) UMAP plot of all HGSOC advanced primary tumor samples, with different colors used to divide the subgroups. (D) Heatmap depicting the expression levels of selected marker genes in major cell subgroups. Rows represent genes, and columns represent clusters. (E) Heatmap showing the number of ligand-receptor pair interactions among cell subtypes, with tumor cells grouped by PTX3 expression as either High or Low. (F) Dot plot showing the expression of selected chemokine-related ligands or receptors across cell subtypes. The color of the dots represents expression levels, the size of the dots indicates the percentage of expression, and lines depict known ligand-receptor interactions

To further expand upon the insights derived from Bulk RNA-seq findings, we utilized single-cell data to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the interactions between OC cell subpopulations distinguished by varying levels of PTX3 expression and the myriad cellular constituents of the TME. We first performed dimensionality reduction clustering of the cell populations into 12 cell subtypes (Fig. 6C). Based on consensus marker genes for subgroups, we identified B cells (CD79A, MS4A1, CD19), CD4 + T cells (CD4, CD3D), CD8 + T cells (CD3D, CD8A, CD8B), NK cells (KLRC1, KLRF1, KLRD1), macrophages (APOE, SPP1, C1QB), DCs (CLEC9A, CD1C, XCR1), fibroblasts (COL1A1, COL1A2, POSTN), mesothelial cells (UPK3B, DES, CALB2), other stromal cells (MYC, PDGFRB, TRPC6), endothelial cells (VWF, PECAM1, CLDN5), epithelial cells (EPCAM, PAX8, KRT18), and proliferating cells (MKI67, STMN1, CDK1) (Fig. 6D).

To explore how tumor cells with high PTX3 expression interact with various cells in the TME, we specifically divided epithelial cells based on PTX3 expression levels into high and low groups. We observed that in comparison to those in the low PTX3 expression group, cells in the high PTX3 expression group demonstrated enhanced cellular interactions with both immune and non-immune cells in the TME. Notably, among immune cells, tumor cells with high PTX3 expression exhibited stronger interactions with macrophages, which is consistent with previous studies in gliomas [15], while they also exhibited stronger interactions with mesothelial cells among non-immune cells (Fig. 6E). Additionally, the analysis of the chemokine regulatory network associated with PTX3 in the TME showed that, compared to low PTX3 expression tumor cells, high PTX3 expression tumor cells exhibited increased MIF and CXCL16 levels, which promoted the recruitment of DCs and CD4 + T cells through MIF-CD74 and CXCL16-CXCR6, respectively. Furthermore, high-PTX3 tumor cells had reduced expression levels of CXCL12 and CXCL13, weakening the effects of CXCL13-CXCR5 and CXCL12-CXCR4 and thereby reducing the recruitment of B and CD8 + T cells (Fig. 6F). These results are consistent with the findings of the bulk RNA-seq analysis. However, our analysis indicated that, in accordance with the findings of the Bulk RNA-sequencing data, the group expressing PTX3 at high levels exhibited reduced secretion of CCL3 compared to the low PTX3 expression cohort. In conclusion, these results confirm that PTX3 functions as an immunoregulatory factor, influencing immune infiltration in OC.

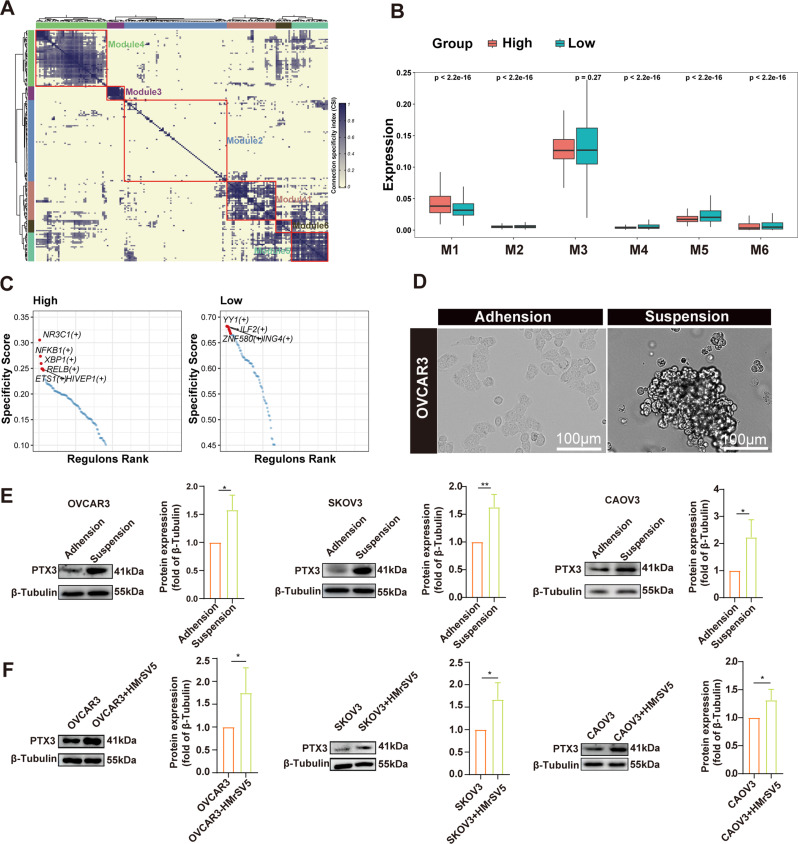

Factors contributing to PTX3 upregulation: TFs, suspension culture and coculture with mesothelial cells

PTX3 expression increases during metastasis and may be affected by multiple factors. Due to the fact that gene expression is often influenced by TFs, we first investigated the TF regulatory networks of all tumor cells, according to the calculated specificity index. The TFs were clustered into six major modules (Fig. 7A). High-PTX3 expressing tumor cells demonstrated an increased in the presence of TFs in module one (M1) (Fig. 7B). This reflected that tumor cells with high PTX3 expression did indeed exhibit activated TF effects. Therefore, we further utilized pySCENIC to analyze the specific TFs in tumor cells with different PTX3 expressions. The results showed that tumor cells with high PTX3 expression exhibited specificity for NR3C1, NFKB1, XBP1, RELB, ETS1, and HIVEP1, while tumor cells with low PTX3 expression exhibited specificity for YY1, ILF2, and ZNF580 (Fig. 7C). We had previously demonstrated that PTX3 can activate the NF-κB signaling pathway. Notably, NFKB1, which encodes a protein that is a DNA binding subunit of the NF-κB protein complex, is a TF specifically activated in tumor cells with high PTX3 expression (Fig. 7C). This is consistent with existing research showing that NF-κB activation can positively regulate PTX3 expression [31, 32]. This observation leads us to hypothesize that the PTX3-NF-κB signaling pathway may form a feedback loop, enhancing and perpetuating its own activation.

Fig. 7.

Correlation of PTX3 expression with TFs and microenvironmental changes. (A) Heatmap showing the distribution of 6 identified TF modules in tumor cells. (B) Box plots showing the levels of TFs in tumor cells with high or low PTX3 expression within each TF module. (C) Rank for regulons in tumor cells with high or low PTX3 expression based on regulon specificity score (RSS). (D) Representative images of the morphology of OC cell lines (OVCAR3) in adherent culture and suspension culture systems. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) PTX3 protein expression in OC cells under adherent and suspension culture conditions (left). Quantitative analysis of PTX3 (right). (F) Western blot detected the expression of PTX3 in OC cells after separate culture and co-culture with peritoneal mesothelial cells (HMrSV5). Quantitative analysis of PTX3 (right). Data are presented as mean ± SD; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

In addition to changes of TFs, site-specific microenvironments can also reshape tumor cells. Tumor cells that shed into ascites initiate a series of reprogramming processes to adapt to the ascitic environment [33]. To further investigate the reasons behind the upregulation of PTX3 during peritoneal metastasis in OC, we subjected OC cells to suspension culture. This method has been used in previous studies to simulate the microenvironment of ascites [34]. Suspension culture induced a spherical morphology in the OC cell lines (Fig. 7D). Moreover, Suspension culture significantly upregulated the PTX3 expression in OC cells (Fig. 7E).

A previous study based on single-cell sequencing demonstrated the presence of mesothelial cells in ascites and suggested that these cells might be involved in regulating the TME [24]. Our single-cell sequencing data also indicated strong interactions between tumor cells with high PTX3 expression and mesothelial cells (Fig. 6E). Therefore, we further investigated the role of mesothelial cells. The results showed that PTX3 expression in OC cells was significantly upregulated after coculture with peritoneal mesothelial cells (Fig. 7F). In summary, we found that the activation of specific TFs, suspension culture, or coculture with peritoneal mesothelial cells may all upregulate PTX3 expression in OC cells. This suggests a multifactorial mechanism underlying its upregulation during OC peritoneal metastasis. Other mechanisms involved in PTX3 regulation warrant further investigation.

Discussion

The roles of PTX3 in cancer, whether pro-tumor or anti-tumor, seem to be influenced by the context, including the origin of the cells, the specific cancer type, and the characteristics of the TME [8, 15, 35, 36]. High expression of PTX3 can promote cervical cancer metastasis [37] but inhibits the formation of new cancerous tissues in [38]. Evidence indicates that PTX3 is upregulated in OC tissues, suggesting its potential role as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for OC [39]. However, the involvement of PTX3 in the peritoneal metastasis of OC and its underlying mechanisms have not yet been determined. Our research aimed to uncover the pro-metastatic functions and mechanisms of PTX3 in OC.

In accordance with our hypothesis, our findings revealed that PTX3 levels correlate with the progression of OC. The single-cell RNA sequencing analysis results indicated that tumor cells had higher PTX3 expression than other cell subgroups. Based on a pseudotime trajectory analysis, OC cells exhibiting high PTX3 levels were shown to be located at the endpoint of pseudotime development, and PTX3 expression gradually increased with the progression of OC metastasis. The IHC results also confirmed that PTX3 expression in the peritoneal metastatic lesions of OC was higher than in the primary lesions.

Previous investigations have demonstrated the involvement of PTX3 in various malignancies [40]. PTX3 could promote cancer stem cell-like characteristics in basal breast cancer [41]. Increased PTX3 expression promotes A549 and H1299 cell line proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer [42]. Moreover, PTX3 knockdown has been shown to reduce the migration and invasion of glioma cells [43]. Targeting tumor cell proliferation, migration and invasion is an important intervention for cancer treatment [44]. Based on our research findings, the overexpression of PTX3 stimulates OC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Therefore, these findings may provide some insight into PTX3 as a prospective interventional target for OC treatment.

PTX3 may promote OC peritoneal metastasis through different mechanisms. Our research suggested that high PTX3 levels in OC patients could be involved in the activation of the EMT and NF-κB signaling pathways. Consistent with the findings of pancreatic cancer studies, PTX3 has been demonstrated to facilitate metastasis by inducing EMT in pancreatic cancer cells [45]. Additionally, in lung cancer research, knocking down PTX3 impeded lung cancer cell invasion via the downregulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [42].

Most of the current targeted therapies for OC have poor efficacy [4]. To inhibit pro-metastatic role of PTX3 in OC and uncover novel targets for its clinical management, we investigated the possible receptors through which PTX3 transmits signals into OC cells. Different members of the TLR family have been shown to contribute to inflammation during cancer progression [46]. Earlier research has shown that PTX3 binds to the TLR4 receptor, enhancing melanoma cell migration and invasion [12]. CD44, a cell-surface non-kinase transmembrane glycoprotein, is broadly overexpressed in numerous tumor types, such as ovarian cancer, and is correlated with aggressive tumor behavior and poor patient prognosis. Research on breast cancer and lung cancer has confirmed that CD44 is a novel PTX3 receptor [13, 47]. We experimentally confirmed that PTX3 co-localized with the OC cell receptors TLR4 and CD44. The inhibition of TLR4 can partially reverse the effects induced by PTX3 overexpression. Therefore, the TLR4 may be a target for the treatment of OC. Given the potential for the PTX3 protein to interact with a diverse array of receptors through its various domains, further research is warranted to elucidate its other roles in regulating ovarian cancer cell behavior.

The TME is closely related to several biological processes of malignancies, such as malignant tumor proliferation, immune evasion and drug tolerance, and is regarded as the environmental “soil” for tumor occurrence, development and metastasis [48, 49]. The continuous crosstalk between tumor cells and the surrounding TME plays a vital role in influencing a tumor occurrence, progression, dissemination and treatment response [50, 51]. In glioma, tumor cells with high PTX3 expression can recruit various immune cells, such as CD4+/CD8 + T cells and macrophages [52]. There are currently no reports on the relationship between PTX3 and the TME in OC. By exploring the cell regulatory network in the TME, we found that high-PTX3-expression tumor cells promoted the recruitment of DCs and CD4 + T cells and reduced the recruitment of B cells and CD8 + T cells. This may be a possible mechanism of immune escape in OC cells. The specific mechanisms through which PTX3-overexpressing OC cells interact with various cells within the TME remain to be further explored to determine the specific molecular basis of the immune escape of OC cells in the TME and to provide new insights and directions for diagnosing and treating OC.

Previous studies have shown that miRNAs, cytokines, TFs and drugs can regulate the expression level of PTX3 [15, 53–59]. We further investigated the upstream molecular events related to PTX3 to reveal potential driving factors of PTX3 upregulation in the metastasis process of OC. Our study found that TFs, such as NR3C1, NFKB1, XBP1, RELB, ETS1, and HIVEP1, were activated in high-PTX3-expression OC tumor cells. Among these, NFKB1 is pivotal to the NF-κB signaling cascade, and our prior findings established that PTX3 activates this pathway. Likewise, in studies on brain gliomas, tumor cells with high PTX3 expression had increased expression of TFs, such as NFKB2, ZNF579, RELB and KLF5 [15]. Therefore, we hypothesize that a positive feedback mechanism involving PTX3 and NFKB1 occurs, wherein elevated NFKB1 levels enhance PTX3 expression. This, in turn, stimulates the NF-κB signaling pathway, further increasing NFKB1 activation and establishing a self-reinforcing loop.

Peritoneal metastasis in OC is a complicated process involving multiple stages, sites, and cell types. Its stages include cancer cell shedding, peritoneal migration, adhesion to the metastasis site, and colonization [48]. It encompasses various locations, such as the primary ovarian cancer lesion, the peritoneal fluid, and metastatic sites [60]. Peritoneal metastasis is initiated by the dislodgement of tumor cells from the parent tumor′s interface. These detached tumor cells can circulate within the peritoneal fluid either as individual cells or as multicellular aggregates known as spheroids [23, 61, 62]. The dynamic changes in OC cells and their interactions with non-tumor cells are key factors in the peritoneal dissemination of OC [60, 63]. To investigate the impact of TME alterations on PTX3 expression in OC cells, we conducted a suspension culture assay and cocultured OC cells with peritoneal mesothelial cells. The findings revealed a notable increase in PTX3 expression in OC cells within both the suspension culture and coculture systems.

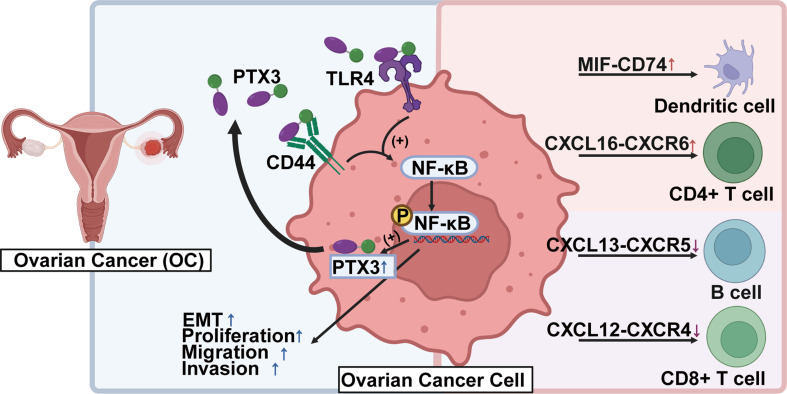

Conclusions

In summary, this study suggested a correlation between the progression of OC peritoneal metastasis and elevated PTX3 expression. We proposed a ‘working model’ that interpreted our results to illustrate the regulation of PTX3 in OC cells and other cells composing the TME. We demonstrated that PTX3 co-localized with TLR4 surface receptors on OC cells, facilitating peritoneal metastasis through the activation of the EMT and NF-κB signaling pathways. Thus, TLR4 might have been a target for the treatment of OC. We also revealed the regulatory network characteristics of PTX3 in the TME during OC metastasis. Importantly, these results indicate that PTX3 is dynamically regulated by TFs and the TME. These findings provide a critical foundation for further research on developing therapeutic strategies for treating OC through the targeting of PTX3 and its receptors (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of the present study (created with BioRender.com, accessed on 15 February 2024)

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1_Clinical_Information.

Supplementary Material 2: Table S2. List of top 20 signature genes expressed in high PTX3 expression and low PTX3 expression group.

Supplementary Material 3: Fig. 1 Expression of PTX3 in cell lines and its impact on gene expression after knockdown and overexpression.

Supplementary Material 4: Fig. 2 Interactions with TLR4 and CD44 and pathways associated with PTX3.

Supplementary Material 5: Fig. 3 PTX3 expression in ovarian cancer cells after suspension and coculture with mesothelial cells.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the use of BioRender.com in Graphical Abstract. (All rights and ownership of BioRender content are reserved by BioRender. BioRender content included in the completed graphic is not licensed for any commercial uses beyond publication in a journal.)

Abbreviations

- PTX3

Pentraxin 3

- HGSOC

High-grade serous ovarian cancer

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- OC

Ovarian cancer

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- TFs

Transcription factors

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- TFs

Transcription factors

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

Author contributions

S.L. and T.W. contributed equally to this work. S.L. performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. T.W. performed the data analyses and image analysis. X.S. designed and performed statistical analysis. L.Q. and X.W. conducted partial functional experiments. Q.L. and X.Z. designed experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers NSFC 82072885, X.Z.], Science and technology plan joint plan of Liaoning Province [grant numbers 2023JH2/101700193, X.Z.], 345 Talent Project of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University [X.Z.] and Science and technology plan joint plan of Liaoning Province [grant numbers 2023JH2/101700132, Q.L.].

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed following the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (Approval number: 2023PS521K). Because abandoned samples of routine clinical detections were collected, the ethics committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University therefore has approved the application for performing the study with the exemption of informed consent from all participants.

Consent for publication

All authors consented for publication.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shuangyan Liu and Tianhao Wu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Qing Liu, Email: liuq82@sj-hospital.org.

Xin Zhou, Email: drzhouxin@163.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer Stat 2023 CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lengyel E. Ovarian Cancer Development and Metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(3):1053–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Samimi G, Runowicz CD, Gaudet MM, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Ovarian Cancer Stat 2018 CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):284–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lheureux S, Braunstein M, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian Cancer: evolution of management in the era of Precision Medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(4):280–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hennessy BT, Coleman RL, Markman M. Ovarian Cancer Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1371–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breviario F, d’Aniello EM, Golay J, Peri G, Bottazzi B, Bairoch A, Saccone S, Marzella R, Predazzi V, Rocchi M. Interleukin-1-Inducible genes in endothelial cells. Cloning of a New Gene related to C-Reactive protein and serum amyloid P component. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(31):22190–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang ZY, Wang X, Zou HC, Dai ZY, Feng SS, Zhang MY, Xiao GL, Liu ZX, Cheng Q. Basic Characteristics Pentraxin Family Their Funct Tumor Progression Front Immunol 11 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Zhang P, Liu Y, Lian C, Cao X, Wang Y, Li X, Cong M, Tian P, Zhang X, Wei G, Liu T, Hu G. Sh3rf3 promotes breast Cancer Stem-Like Properties Via Jnk activation and Ptx3 Upregulation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozlowski M, Michalczyk K, Witczak G, Kwiatkowski S, Mirecka A, Nowak K, Pius-Sadowska E, Machalinski B. and A. Cymbaluk-Ploska. Evaluation of Paraoxonase-1 and Pentraxin-3 in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Endometrial Cancer. Antioxidants (Basel) 11, no. 10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflamm Cancer Nat. 2002;420(6917):860–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giacomini A, Turati M, Grillo E, Rezzola S, Ghedini GC, Schuind AC, Foglio E, Maccarinelli F, Faletti J, Filiberti S, Chambery A, Valletta M, Melocchi L, Gofflot S, Chiavarina B. Andrei Turtoi, Marco Presta, and Roberto Ronca. The Ptx3/Tlr4 Autocrine Loop as a Novel Therapeutic Target in Triple negative breast Cancer. Experimental Hematol Oncol. 2023;12:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathore M, Girard C, Ohanna M, Tichet M, Ben Jouira R, Garcia E, Larbret F, Gesson M, Audebert S, Lacour JP, Montaudie H, Prod’Homme V, Tartare-Deckert S. Deckert. Cancer Cell-Derived Long Pentraxin 3 (Ptx3) promotes Melanoma Migration through a toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4)/Nf-Kappab Signaling Pathway. Oncogene. 2019;38:30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao YW, Chi JY, Li CF, Chen LY, Chen YT, Liang HY, Lo YC, Hong JY, Chuu CP, Hung LY, Du JY, Chang WC, Wang JM. Disruption of the Pentraxin 3/Cd44 Interaction as an efficient therapy for triple-negative breast cancers. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(1):e724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang X, Li D, Liu C, Zhang Z, Wang T. Pentraxin 3 is a diagnostic and prognostic marker for ovarian epithelial Cancer patients based on Comprehensive Bioinformatics and experiments. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Wang YF, Zhao YH, Liu T, Wang ZY, Zhang N, Dai ZY, Wu WT, Cao H, Feng SS, Zhang LY, Cheng Q, Liu ZX. Ptx3 mediates the infiltration, Migration, and inflammation-resolving-polarization of macrophages in Glioblastoma. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022;28(11):1748–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen F-W, Wu Y-L, Cheng C-C, Hsiao Y-W, Chi J-Y, Hung L-Y, Chang C-P. Ming-Derg Lai, and Ju-Ming Wang. Inactivation of Pentraxin 3 suppresses M2-Like macrophage activity and immunosuppression in Colon cancer. J Biomed Sci. 2024;31:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui X, Qin T, Zhao Z, Yang G, Sanches JGP, Zhang Q, Fan S, Cao L, Hu X. Pentraxin-3 inhibits Milky spots Metastasis of Gastric Cancer by inhibiting M2 macrophage polarization. J Cancer. 2021;12(15):4686–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Visser KE, Joyce JA. The evolving Tumor Microenvironment: from Cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(3):374–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B, Li X, Zhang W, Fan J, Zhou Y, Li W, Yin J, Yang X, Guo E, Li X, Fu Y, Liu S, Hu D, Qin X, Dou Y, Xiao R, Lu F, Wang Z, Qin T, Wang W, Zhang Q, Li S, Ma D, Mills GB, Chen G, Sun C. Spatial heterogeneity of infiltrating T cells in high-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer revealed by Multi-omics Analysis. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3(12):100856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montfort A, Pearce O, Maniati E, Vincent BG, Bixby L, Bohm S, Dowe T, Wilkes EH, Chakravarty P, Thompson R, Topping J, Cutillas PR, Lockley M, Serody JS, Capasso M, Balkwill FR. A strong B-Cell response is part of the Immune Landscape in Human High-Grade Serous Ovarian metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(1):250–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroeger DR, Milne K, Nelson BH. Tumor-infiltrating plasma cells are Associated with Tertiary lymphoid structures, cytolytic T-Cell responses, and Superior Prognosis in Ovarian Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(12):3005–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Guo T. Role of peritoneal mesothelial cells in the progression of peritoneal metastases. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peinado H, Zhang H, Matei IR, Costa-Silva B, Hoshino A, Rodrigues G, Psaila B, Kaplan RN, Bromberg JF, Kang Y, Bissell MJ, Cox TR, Giaccia AJ, Erler JT, Hiratsuka S, Ghajar CM, Lyden D. Pre-metastatic niches: Organ-Specific Homes for Metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(5):302–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng X, Wang X, Cheng X, Liu Z, Yin Y, Li X, Huang Z, Wang Z, Guo W, Ginhoux F, Li Z, Zhang Z, Wang X. Single-cell analyses implicate ascites in remodeling the ecosystems of primary and metastatic tumors in Ovarian Cancer. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(8):1138–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreatta M, Carmona SJ. Ucell: robust and scalable single-cell gene signature scoring. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:3796–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Efremova M, Vento-Tormo M, Teichmann SA, Vento-Tormo R. Cellphonedb: Inferring Cell-Cell communication from combined expression of multi-subunit ligand-receptor complexes. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(4):1484–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suo S, Zhu Q, Saadatpour A, Fei L, Guo G, Yuan GC. Revealing Crit Regulators Cell Identity Mouse Cell Atlas Cell Rep. 2018;25(6):1436–45. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuxman Bass JI, Diallo A, Nelson J, Soto JM, Myers CL, Walhout AJ. Using Networks Measure Similarity between Genes: Association Index Selection Nat Methods. 2013;10(12):1169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, Li B, Liu XS. Timer2.0 for analysis of Tumor-infiltrating Immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(no W1):W509–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ru B, Wong CN, Tong Y, Zhong JY, Zhong SSW, Wu WC, Chu KC, Wong CY, Lau CY, Chen I, Chan NW, Zhang J. Tisidb: Integr Repository Portal Tumor-Immune Syst Interact Bioinf. 2019;35(20):4200–02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmmed B, Kampo S, Khan M, Faqeer A, Seewooruttun Pawan kumar, Li Yulin, Liu JW, Yan Q. Rg3 Inhibits Gemcitabine-Induced Lung Cancer Cell Invasiveness through Ros‐Dependent, Nf‐Κb‐ and Hif‐1α‐Mediated Downregulation of Ptx3. Journal of Cellular Physiology 234, no. 7 (2019): 10680-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Shin H, Jeon J, Lee J-H, Jin S, Ha U-H, Craig R. Roy. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Groel stimulates production of Ptx3 by activating the Nf-Κb pathway and simultaneously downregulating Microrna-9. Infect Immun. 2017;85:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang XZ, Pang MJ, Li JY, Chen HY, Sun JX, Song YX, Ni HJ, Ye SY, Bai S, Li TH, Wang XY, Lu JY, Yang JJ, Sun X, Mills JC, Miao ZF, Wang ZN. Single-cell sequencing of Ascites Fluid illustrates Heterogeneity and Therapy-Induced Evolution during Gastric Cancer Peritoneal Metastasis. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, Han Y, Kim SI, Lee J, Jo HA, Wang W, Cho U, Park W-Y, Rando TA, Danny N. Dhanasekaran, and Yong Sang Song. Computational modeling of malignant ascites reveals Ccl5–Sdc4 Interaction in the Immune Microenvironment of Ovarian Cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2021;60(5):297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matarazzo S, Melocchi L, Rezzola S, Grillo E, Maccarinelli F, Giacomini A, Turati M, Taranto S, Zammataro L, Cerasuolo M, Bugatti M, Vermi W, Presta M. and R. Ronca. Long Pentraxin-3 Follows and Modulates Bladder Cancer Progression. Cancers (Basel) 11, no. 9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Giacomini A, Ghedini GC, Presta M, Ronca R. Long pentraxin 3: a Novel Multifaceted Player in Cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2018;1869(1):53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying TH, Lee CH, Chiou HL, Yang SF, Lin CL, Hung CH, Tsai JP. Hsieh. Knockdown of Pentraxin 3 suppresses tumorigenicity and metastasis of human cervical Cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma D, Zong Y, Zhu ST, Wang YJ, Li P, Zhang ST. Inhibitory role of Pentraxin-3 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016;129(18):2233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang XY, Li D, Liu C, Zhang Z, Wang T. Pentraxin 3 is a diagnostic and prognostic marker for ovarian epithelial Cancer patients based on Comprehensive Bioinformatics and experiments. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Wang R, Wang Z, Wu W, Zhang N, Zhang L, Hu J, Luo P, Zhang J, Liu Z, Feng S, Peng Y, Liu Z, Cheng Q. Molecular Insight into Pentraxin-3: update advances in innate immunity, inflammation, tissue remodeling, diseases, and Drug Role. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas C, Henry W, Cuiffo BG, Collmann AY, Marangoni E, Benhamo V, Bhasin MK, Fan C, Fuhrmann L, Baldwin AS, Perou C, Vincent-Salomon A, Toker A, Karnoub AE. Pentraxin-3 is a Pi3k Signaling Target that promotes Stem Cell-Like traits in basal-like breast cancers. Sci Signal. 2017;10:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Song X, Niu J, Ren M, Tang G, Sun Z, Kong F. Pentraxin 3 acts as a functional effector of Akt/Nf-Kappab signaling to modulate the progression and cisplatin-resistance in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2021;701:108818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tung JN, Ko CP, Yang SF, Cheng CW, Chen PN, Chang CY, Lin CL, Yang TF, Hsieh YH. Chen. Inhibition of Pentraxin 3 in glioma cells impairs Proliferation and Invasion in Vitro and in vivo. J Neurooncol. 2016;129(2):201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerstberger S, Jiang Q, Ganesh K. Metastasis Cell 186, 8 (2023): 1564–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Kondo S, Ueno H, Hosoi H, Hashimoto J, Morizane C, Koizumi F, Tamura K, Okusaka T. Clinical impact of Pentraxin Family expression on prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(3):739–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaur A, Baldwin J, Brar D, Salunke DB, Petrovsky N. Toll-like receptor (tlr) agonists as a driving force behind Next-Generation Vaccine adjuvants and Cancer therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol 70 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Chi JY, Hsiao YW, Liang HY, Huang TH, Chen FW, Chen CY, Ko CY, Cheng CC. Wang. Blockade of the Pentraxin 3/Cd44 Interaction attenuates Lung Injury-Induced Fibrosis. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(11):e1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fidler IJ. Timeline - the Pathogenesis of Cancer Metastasis: the ‘Seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):453–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mei SS, Chen X, Wang K, Chen YX. Tumor Microenvironment Ovarian Cancer Perit Metastasis Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lv BZ, Wang YP, Ma DJ, Cheng W, Liu J, Yong T, Chen H, Wang C. Immunotherapy: Reshape Tumor Immune Microenvironment Front Immunol 13 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Arner EN, Rathmell JC. Metabolic programming and Immune suppression in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(3):421–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doni A, Stravalaci M, Inforzato A, Magrini E, Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Bottazzi B. The long Pentraxin Ptx3 as a link between Innate Immunity, tissue remodeling, and Cancer. Front Immunol. 2019;10:712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nauta AJ, de Haij S, Bottazzi B, Mantovani A, Borrias MC, Aten J, Rastaldi MP, Daha MR, van Kooten C, Roos A. Hum Ren Epithel Cells Produce Long Pentraxin Ptx3 Kidney Int. 2005;67(2):543–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu LM, Wang WW, Qi R, Leng TG, Zhang XL. Microrna-224 inhibition prevents progression of cervical carcinoma by targeting Ptx3. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(12):10278–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rudnicki A, Shivatzki S, Beyer LA, Takada Y, Raphael Y, Avraham KB. Microrna-224 regulates Pentraxin 3, a component of the humoral arm of Innate Immunity, in inner ear inflammation. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(12):3138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woo JM, Kwon MY, Shin DY, Kang YH, Hwang N, Chung SW. Hum Retinal Pigment Epithel Cells Express Long Pentraxin Ptx3 Mol Vis. 2013;19:303–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diao J, Chen X, Jiang L, Mou P, Wei R. Transforming growth Factor-Beta1 suppress Pentraxin-3 in Human Orbital fibroblasts. Endocrine. 2020;70(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lathoria K, Gowda P, Umdor SB, Patrick S, Suri V, Sen E. Prmt1 driven Ptx3 regulates Ferritinophagy in Glioma. Autophagy. 2023;19(7):1997–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu MY, Deng WB, Tang L, Liu M, Bao HL, Guo CH, Zhang CX, Lu JH, Wang HB, Lu ZX, Kong SB. Menin directs Regionalized Decidual Transformation through Epigenetically setting Ptx3 to Balance Fgf and Bmp Signaling. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schoutrop E, Moyano-Galceran L, Lheureux S, Mattsson J, Lehti K, Dahlstrand H, Magalhaes I. Molecular, Cellular and systemic aspects of epithelial ovarian Cancer and its Tumor Microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol 86, no. Pt. 2022;3:207–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cortes-Guiral D, Hubner M, Alyami M, Bhatt A, Ceelen W, Glehen O, Lordick F, Ramsay R, Sgarbura O, Van Der Speeten K, Turaga KK, Chand M. Prim Metastatic Perit Surf Malignancies Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mikula-Pietrasik J, Uruski P, Tykarski A, Ksiazek K. The peritoneal soil for a cancerous seed: a Comprehensive Review of the pathogenesis of Intraperitoneal Cancer metastases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(3):509–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ritch SJ, Telleria CM. The transcoelomic ecosystem and epithelial ovarian Cancer dissemination. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:886533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1_Clinical_Information.

Supplementary Material 2: Table S2. List of top 20 signature genes expressed in high PTX3 expression and low PTX3 expression group.

Supplementary Material 3: Fig. 1 Expression of PTX3 in cell lines and its impact on gene expression after knockdown and overexpression.

Supplementary Material 4: Fig. 2 Interactions with TLR4 and CD44 and pathways associated with PTX3.

Supplementary Material 5: Fig. 3 PTX3 expression in ovarian cancer cells after suspension and coculture with mesothelial cells.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.