Abstract

Background:

Medico-legal complaints against physicians are a significant source of anxiety and could be associated with defensive medical practices that may correlate with poor patient outcomes. Little is known about patient concerns brought to regulatory bodies and courts against dermatologists in Canada.

Objective:

To characterize factors contributing to medico-legal complaints brought against dermatologists in Canada.

Methods:

The Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) repository was queried for all closed cases involving dermatologists over the past decade. Aggregate, anonymized data was reviewed and case outcomes, patient harm, and contributing factors were extracted.

Results:

Nearly one-fifth of all dermatologists who are CMPA members have been named in at least one medico-legal case between 2013 to 2022. A total of 396 civil-legal actions or College complaint cases involving dermatologists were closed at the CMPA during this timeframe. The most common patient allegations were deficient assessment (34%), diagnostic error (28%), and unprofessional manner (22%). Nearly half of patients experienced a harmful event, the majority of which were asymptomatic or mild. The most frequently identified contributing factors related to providers were poor clinical decision making (n = 73), lack of situational awareness (n = 67), and conduct and boundary issues (n = 59). Team factors included a breakdown of communication with patients (n = 124).

Conclusions:

Improved communication with patients for informed consent, treatment plans, clinical follow-up, and documentation of thorough clinical patient assessments can improve patient satisfaction and health outcomes, and mitigate dermatologists’ medico-legal risk.

Keywords: medico-legal, lawsuit, informed consent, professionalism, CMPA

Introduction

Medico-legal complaints by patients against their physicians are common. The American Medical Association estimates that as of 2022, nearly one-third of all physicians in the United States had been sued at some point in their careers.1-3 Complaints are associated with important impacts on both physician well-being and their clinical practice. Physicians who receive formal complaints report experiencing anger, reduced enjoyment of the practice of medicine, and feelings of shame that can persist for several years.4,5 Furthermore, they are also more likely to make clinical decisions that are based on the most legally defensible course of action rather than best evidence-based practices, resulting in both the under- and over-utilization of diagnostic testing and therapeutic interventions.6-9 A survey of over 800 physicians in high-risk litigation specialties found that more than 90% reported practicing defensive medicine with 42% of respondents restricting their practice in the past 3 years to minimize procedures prone to complication and avoiding patients who are perceived as complex and litigious, presenting important issues for equitable access to care. 10 Therefore, defensive medicine is associated with a greater rate of inefficient healthcare resource utilization, and overmedicalization of patients, and can contribute to worse healthcare outcomes.11,12 Moreover, time spent by physicians participating in the complaint proceedings is poorly documented but likely has a clinical impact.

Consequently, an improved understanding of historical trends in complaints lodged against physicians and any contributing provider factors may provide an alternative to defensive medicine and allow physicians to critically evaluate their own clinical practice, identify areas to improve patient care, and mitigate future medico-legal risk. Therefore, we queried the Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) repository for all medical regulatory body (College) complaints and civil-legal action cases brought against dermatologists in Canada from 2013 to 2022.

Methods

Data Sources

The CMPA is a mutual defence association that protects the professional integrity of Canadian physicians and promotes safe healthcare practices. 13 The CMPA provides assistance and advice to more than 110,000 physician members, which represents over 95% of all Canadian physicians. After a complaint to a provincial health regulatory body (College) or a civil-legal action lawsuit is launched against a CMPA member physician related to their practice of medicine, the involved physician can bring the case to the CMPA, who will subsequently provide legal representation and compensate patients who are proved to be harmed by negligent medical care.

The CMPA maintains a national repository of medico-legal data for the purposes of physician education and quality improvement. It contains de-identified healthcare provider and patient information, clinical data (eg, care setting and patient safety incidents) peer expert opinion of the factors contributing to the case outcome, and medico-legal case information (eg, case outcome). Peer experts are individuals (usually physicians with similar training and experience as those named) retained in the case to review the patient’s care. 14 Legal and College case information is reviewed and coded by medical analysts at the CMPA. Medical analysts are nurses with clinical experience and extensive training in medico-legal data analysis and research. Peer expert opinions are reviewed to further identify factors contributing to the case and are categorized into provider, team, or system factors. Contributing factors are coded using a previously published medical coding methodology, the CMPA contributing factor framework. 14 Cases are de-identified and reported in aggregate to ensure confidentiality for patients and healthcare providers. Full dataset details and definitions are available in Supplemental Table 1.

Civil-legal action and College complaint aggregate data across all care settings against practicing dermatologists closed at the CMPA between 2013 and 2022 were extracted for analysis. A single physician involved in multiple cases was counted multiple times during this analysis.

Results

Patient and Physician Demographics

Between 2013 and 2022, a total of 396 cases (306 College complaints, 77% vs 90 civil-legal action cases, 23%) involving 403 dermatologists in Canada were closed at the CMPA, representing 1.3% of all closed cases. Of all dermatologists who were members of the CMPA at any time during the study period, 19.5% were named in one and an additional 19.5% were named in more than one medico-legal case over this same time frame. Furthermore, 32 other physicians were involved in these cases, of which the most common specialty was family medicine (n = 14). Most cases were medical encounters as opposed to cosmetic (n = 313, 79%). Dermatologists in practice for over 30 years (n = 118, 29%) followed by dermatologists in practice for 11 to 20 years (n = 104, 26%) were most often named in these complaints (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Dermatologists and Patients Involved in Regulatory Body Complaints or Civil-Legal Action Cases in Canada from 2013 to 2022.

| Physician | Patient | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of practice | Dermatologists (n, %) | Age | Patients (n, %) |

| >30 | 118 (29) | ≥80 | 23 (6) |

| 21-30 | 82 (20) | 65-79 | 63 (16) |

| 11-20 | 104 (26) | 30-64 | 205 (51) |

| 6-10 | 41 (10) | 18-29 | 37 (9) |

| <5 | 58 (14) | 2-17 | 21 (5) |

| <2 | <10 | ||

| Age not reported | 49 (12) | ||

A total of 399 patients brought forth complaints; more than half were aged 30 to 64 years (n = 205, 51%) and almost two-thirds were female (62%). The presenting skin disorders were diverse and included both malignant and benign neoplasms, dermatitis and eczema, and papulosquamous disorders. The most common listed comorbidities were prior diagnosis of skin disease (n = 20, eg, acne vulgaris, actinic keratosis, and psoriasis) and personal history of cancer (n = 17).

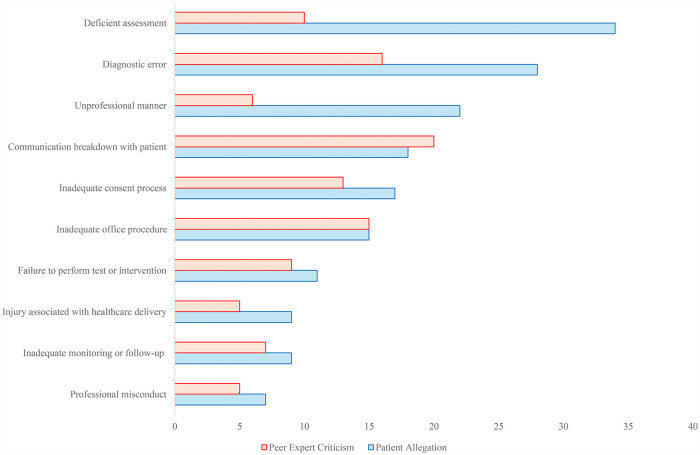

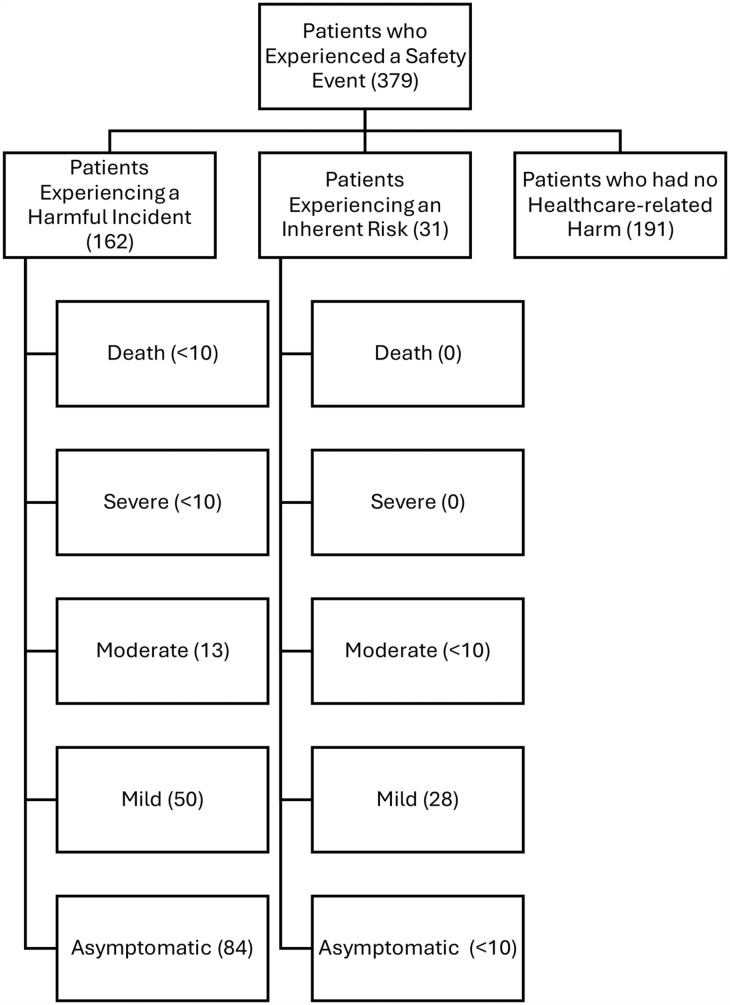

Interventions and Complications

The most common physician interventions subject to patient complaint were office-based pharmacotherapies and injections (n = 99, ex. local injections such as corticosteroids, botulinum toxin, or soft tissue fillers), skin biopsy (n = 54), laser therapy (n = 34), partial excision of the skin (n = 33, ex. cyst removal), and cryotherapy (n = 52). The most common criticism for an intervention not performed was skin biopsy (n = 18). Allegations in relation to these interventions were most commonly deficient physician assessment (34% of patient allegations), diagnostic error (28%), unprofessional physician manner (22%), communication breakdown with the patient (18%), and inadequate consent (17%, Figure 1). Nearly half of all patients (n = 193, 48%) experienced healthcare-related harm with peer experts deeming physician-provided care as deficient for the majority of these cases (n = 162, 84%). Within these cases, the harm was generally asymptomatic (n = 84, 52%) or mild (n = 50, 31%, Figure 2). Examples of complications include delay in follow-up of skin cancer pathology results or misdiagnosis resulting in more advanced disease and associated morbidity.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patient allegations related to deficient care versus peer expert criticisms.

Figure 2.

Distribution of healthcare-related harm.*

*Patients with unknown harm or insufficient information to evaluate the level of harm are not represented in this figure.

Peer expert criticisms were issued for 267 cases (67%), and these generally coincided with patient allegations with the majority of identified deficiencies relating to communication breakdown with the patient (n = 78, 20%), diagnostic error (n = 63, 16%), and inadequate in-office procedures (n = 60, 15%). However, peer experts only found the physician assessment to be inadequate in 41 (10%) cases, compared to allegations of inadequate assessment in 134 (34%) cases.

Contributing Factors to Medico-Legal Cases

Contributing factor analyses can be found in Table 2. Both physician (n = 163, 61%) and team (n = 177, 66%) factors contributed to medico-legal complaints and patient harm. System factors were identified in 70 cases (26%), respectively.

Table 2.

Contributing Factor Analysis with Example Deficiencies.

| Category (n) | Contributing factors (n) | Examples of provided healthcare deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Provider (163) | Clinical decision making (73) | Failure to ensure all available test results were reviewed prior to performing a patient’s biopsy procedure. Failure to perform an adequate assessment when they provided a virtual consultation when a direct in-person physical examination was warranted. Failure to biopsy a suspicious lesion delayed a patient’s diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. |

| Situational awareness (67) | Limited involvement and supervision of tasks delegated to another healthcare provider. Failure to ensure a system was in place to review and document all test results and ensure patients were informed in a timely manner about any abnormal findings (eg, final pathology). |

|

| Conduct, and boundary issues (59) | Unprofessional manner (eg, insensitive language, lacking empathy). Professional misconduct (eg, inappropriate billing). Using inappropriate language in an email message to the patient. |

|

| Procedural violations (24) | Failure to meet safety standards, for example, the reprocessing of instruments was not adequate, the sharps containers were within reach of children. | |

| Team (177) | Communication breakdown with patient (124) a | Failure to clearly explain all possible diagnoses and alternative diagnostic options (eg, Mohs surgery) when obtaining informed consent for an excisional biopsy. Treatment of additional lesions that were not identified in the initial assessment without the patient’s consent. Delegating the consent discussion to a non-physician and failing to maintain consent forms up to date with current treatments. Failure to provide clear instructions about dressing changes to a patient. |

| Compliance with standards of documentation (76) | Notes lacked relevant findings (eg, detailed description of the location and size of the lesion), the patient’s clinical information (eg, smoking history), differential diagnosis, and the rationale for decision making (eg, reason for specific treatment). The findings and recommendations for patient follow-up were not noted in the health record. Failure to document review of test results and the plan of care. |

|

| Communication breakdown with physician (17) | A timely dictated consultation note was not sent to the referring physician. | |

| Coordination of care among physicians (13) | Failure to ensure patient follow-up with a specialist (eg, oncologist) was confirmed. | |

| Systems (70) | Office and resource issues (70) | Inadequate systems to ensure timely review and management of test results. Long office wait times for patients causing them to leave without being seen. Excessive wait times for an appointment with a dermatologist. Processes to inform the referring physician in a timely manner when a request for urgent consult could not be met. |

The Canadian Medical Protective Association considers the patient an important part of the healthcare team, so communication breakdown with patients is included in this category.

The most common physician factors were related to clinical decision making (n = 73); situational awareness (n = 67); and conduct and boundary issues (n = 59). The most common team factor was overwhelmingly related to communication breakdown with patients (n = 124), which included issues such as inadequate informed consent, delegation of informed consent to a non-physician, and failure to provide clear post-treatment care instructions. Compliance with standards of documentation was also commonly criticized (n = 76) with medical chart notes lacking relevant clinical history or physical examination findings, differential diagnoses, and rationale for decision making.

Discussion

In this study of medico-legal cases involving dermatologists in Canada over the past decade, we identify several novel and highly relevant findings for practicing dermatologists. First, whereas patients most commonly alleged that dermatologists were unprofessional or performed inadequate assessments, peer experts disagreed and found this only to be the case in 6% and 10% of cases, respectively. This emphasizes the disparity between patient and provider/expert perceptions of a healthcare encounter. Second, diagnostic errors were common, resulting in patient harm. Finally, communication breakdown resulted in a substantial volume of complaints, highlighting the need for dermatologists to employ better verbal and non-verbal techniques to help bridge the disconnect between patients and providers.

In general, demand for dermatologists has been progressively rising, resulting in substantial wait times.15-18 Consequently, an increasing number of non-physician providers are being employed across all sectors of medicine to help facilitate access to both generalist and sub-specialist care, such as certified registered nurse anaesthetists, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners.19,20 An analysis of Medicare provider utilization and payment data in the United States found that nearly 50% of dermatology clinics employ non-physician providers who are independently billing for both medical and cosmetic procedures, including complex services such as surgical graft repairs and pathology interpretation.21,22 However, Dermatologists have a responsibility to remain appropriately involved in patient care and supervise care delegated to other providers.

Interestingly, we find that peer experts and patients often do not agree on either the thoroughness of an assessment or the dermatologist’s professional manner. This may be due to the subjective perception of what a healthcare visit should entail that intrinsically differs between individuals as a consequence of factors such as cultural background, previous healthcare lived experiences, and power imbalances driven by knowledge differentials. 23 Even though a physician’s behaviour may not be formally sanctioned as inappropriate, the patient perception in and of itself has important care implications. Patients who are dissatisfied are more likely to be sceptical of treatment recommendations and search for new physicians, introducing risks associated with delayed treatment initiation, accumulation of medical comorbidity, and loss to follow-up. 24 Nevertheless, counterproductive relationship-building strategies (such as acquiescence to patient-requested diagnostic or therapeutic interventions that are of limited benefit) may lead to patient harm and healthcare infrastructural inefficiencies.25,26 Therefore, dermatologists must thoughtfully navigate individual patient encounters and differing preferences to provide the best overall care. For instance, physicians can leverage different evidence-based strategies that help build rapport even in time-sensitive situations, such as patient preference-based agenda setting, guiding patients through laboratory or histopathology results, exploring emotional cues, and avoiding potentially judgemental language or behaviour.27-29

In addition to negative patient outcomes, healthcare encounters that result in professional regulatory body action or litigation also have important effects on physicians. Feelings of shame and anger are less likely to contribute meaningfully to insightful self-reflection that identifies areas for improvement, and may instead promote maladaptive coping practices. 10 Given that mistakes and unintentional insensitive communications or actions occur, physician leadership organizations and structures dedicated to maximizing physician wellness should focus on cultivating a work environment that acknowledges that physicians cannot always be perfect, and that self-compassion is critical. 30 In doing so, it may encourage practitioners to approach these complex and challenging situations with more of a personal and professional growth mindset.

Our study has several strengths. It uses nationally representative data over a decade to characterize medico-legal complaints filed against dermatologists, highlighting clinically relevant areas for further quality improvement research. We also identify several areas of opportunity for dermatologists to enhance their daily practice, such as: (a) fully gathering relevant patient medical history and performing a thorough physical examination as clinically indicated; (b) clearly documenting in the patient chart all relevant findings, differential diagnoses, treatment plans, and care instructions; and (c) clear and professional communication with patients both pre-treatment to ensure fully informed consent, and post-treatment to ensure clarity on follow-up instructions. In doing so, dermatologists can improve patient care while minimizing medico-legal risk.

However, our study also has relevant limitations. First, medico-legal cases are limited by recall, hindsight, or outcome bias, so analyses of these findings are similarly subject to the same confounding variables. Second, rates of malpractice complaints and litigation vary between regions, likely because of differing medico-legal systems and standards of practice. 31 Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to other jurisdictions. Finally, physician members report complaints filed against them to the CMPA electively, so we did not capture cases where the named dermatologist declined to involve the CMPA for legal counsel or representation. However, this likely represents only a small proportion of minor cases that the dermatologist felt did not require involvement of a lawyer given that the vast majority of physicians are already CMPA members and are provided with medico-legal support. Therefore, our study likely captures most cases that may have involved serious patient harm or threats of legal action.

In conclusion, there have been nearly 400 regulatory body complaints and civil actions against practicing dermatologists in Canada over the past decade, involving 39% of all dermatologists who are CMPA members in that timeframe. The most common patient concerns related to inadequate assessments, diagnostic errors, and unprofessional manner. Knowing these concerns are common gives dermatologists the opportunity to optimize their communication skills, clinical documentation, and practice management to reduce future medico-legal risks, enhance patient safety, and optimize medical outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cms-10.1177_12034754241275989 for Medico-Legal Complaints Against Dermatologists: Data From the Canadian Medical Protective Association, 2013 to 2022 by Bryan Ma, Ye-Jean Park, Jing Han, Maharshi Gandhi, Michele Ramien, David Klassen, Laura Payant, Elaine Rose, Gary Garber, Mireille Probst and Jori Hardin in Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Internal Review Board Approval Status: Not applicable.

Patient Consent: Not applicable.

ORCID iDs: Bryan Ma  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9637-5530

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9637-5530

Maharshi Gandhi  https://orcid.org/0009-0009-4056-949X

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-4056-949X

Michele Ramien  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9191-3611

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9191-3611

Jori Hardin  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3419-5550

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3419-5550

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schaffer AC, Yu-Moe CW, Babayan A, Wachter RM, Einbinder JS. Rates and characteristics of medical malpractice claims against hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(7):390-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Payerchin R. See you in court: 31% of physicians get sued during their careers. MedicalEconomics. 2023. Cited March 15, 2024. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/see-you-in-court-31-of-physicians-get-sued-during-their-careers

- 4. Cunningham W, Dovey S. The effect on medical practice of disciplinary complaints: potentially negative for patient care. N Z Med J. 2000;113(1121):464-467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cunningham W. The immediate and long-term impact on New Zealand doctors who receive patient complaints. N Z Med J. 2004;117(1198):U972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cunningham W, Wilson H. Complaints, shame and defensive medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(5):449-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pischedda G, Marinò L, Corsi K. Defensive medicine through the lens of the managerial perspective: a literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baungaard N, Skovvang PL, Assing Hvidt E, Gerbild H, Kirstine Andersen M, Lykkegaard J. How defensive medicine is defined in European medical literature: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e057169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reschovsky JD, Saiontz-Martinez CB. Malpractice claim fears and the costs of treating medicare patients: a new approach to estimating the costs of defensive medicine. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1498-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pierce AT, Sheaffer WW, Lu PG, et al. Impact of “Defensive Medicine” on the costs of diabetes and associated conditions. Ann Vasc Surg. 2022;87:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen J, Majercik S, Bledsoe J, et al. The prevalence and impact of defensive medicine in the radiographic workup of the trauma patient: a pilot study. Am J Surg. 2015;210(3):462-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CMPA—home. CMPA. Cited March 15, 2024. https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/home

- 14. McCleery A, Devenny K, Ogilby C, et al. Using medicolegal data to support safe medical care: a contributing factor coding framework. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2019;38(4):11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mydlarski PR, Parsons LM, Pierscianowski TA, et al. Dermatologic training and practice in Canada: a historical overview. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23(3):307-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(5):472-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McIntyre D, Chow CK. Waiting time as an indicator for health services under strain: a narrative review. Inquiry. 2020;57:46958020910305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suneja T, Smith ED, Chen GJ, Zipperstein KJ, Fleischer AB, Jr, Feldman SR. Waiting times to see a dermatologist are perceived as too long by dermatologists: implications for the dermatology workforce. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(10):1303-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO. Implications of the rapid growth of the nurse practitioner workforce in the US. Health Aff. 2020;39(2):273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martsolf GR, Barnes H, Richards MR, Ray KN, Brom HM, McHugh MD. Employment of advanced practice clinicians in physician practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):988-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adamson AS, Suarez EA, McDaniel P, Leiphart PA, Zeitany A, Kirby JS. Geographic distribution of nonphysician clinicians who independently billed medicare for common dermatologic services in 2014. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):30-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(9):1040-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nimmon L, Stenfors-Hayes T. The “Handling” of power in the physician-patient encounter: perceptions from experienced physicians. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zolnierek KBH, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Macfarlane R, Britten N. Influence of patients’ expectations on antibiotic management of acute lower respiratory tract illness in general practice: questionnaire study. BMJ. 1997;315(7117):1211-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Njue SM, Giordano TP. Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor-patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shanafelt TD. Physician well-being 2.0: where are we and where are we going? Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(10):2682-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wallace E, Lowry J, Smith SM, Fahey T. The epidemiology of malpractice claims in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e002929. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cms-10.1177_12034754241275989 for Medico-Legal Complaints Against Dermatologists: Data From the Canadian Medical Protective Association, 2013 to 2022 by Bryan Ma, Ye-Jean Park, Jing Han, Maharshi Gandhi, Michele Ramien, David Klassen, Laura Payant, Elaine Rose, Gary Garber, Mireille Probst and Jori Hardin in Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery