Abstract

Background

Dermatologists consistently face challenges in treating demodicosis due to its high recurrence rate and difficulty normalizing the Demodex density (Dd) even after clinical improvement. Oral ivermectin has proven to be an effective treatment for demodicosis. However, there is a lack of comprehensive information on the clinical and acaricidal effects of oral ivermectin in treating demodicosis.

Purpose

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of oral ivermectin on clinical symptoms and Dds of patients with demodicosis.

Methods

This prospective, quasi-experimental study included 40 demodicosis patients (20 with Demodex densities (Dds) < 20 D/cm2, 20 with Dds ≥20 D/cm2). Both groups of patients were treated with oral ivermectin (200 µg/kg/week) until excellent clinical improvement (Grade 4 according to the Quartile Grading Scale), and Dds ≤ 5 D/cm2 or treated with oral ivermectin for a total of eight weeks period.

Results

In our study, 75% of patients achieved clinical remission, showing excellent clinical improvement with Dds ≤ 5 D/cm2. All patients with a Dds <20 D/cm² experienced remission, while 50% with a Dds ≥20 D/cm² achieved remission. The median time to remission after oral ivermectin treatment was 28 days for Dds <20 D/cm² and 56 days for Dds ≥20 D/cm² (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Oral ivermectin effectively improves clinical symptoms and normalizes Dds in patients with demodicosis. Patients with higher Dds require a longer treatment than those with lower Dds.

Keywords: ivermectin, demodicosis, Rosacea, Demodex mite, Demodex folliculorum, Demodex brevis

Introduction

Demodex mites are ectoparasites that live in the pilosebaceous units of human skin and are part of the natural skin microflora. The normal Demodex density (Dd) on the face in the adult population is ≤ 5/cm2.1 Excessive Demodex mites on the face can cause demodicosis, leading to symptoms such as dryness, itching, burning, scaly patches, papules, pustules, and telangiectasia.2–4 This overgrowth is also related to a range of skin disorders, such as rosacea,5,6 blepharitis,7 perioral dermatitis,8 pityriasis folliculorum,9 and pustular folliculitis.10

Common treatments for demodicosis include topical ivermectin, benzyl benzoate, tea tree oil, metronidazole, permethrin, crotamiton, lindane, and oral medication such as ivermectin or metronidazole, or a combination of these.11–13

Oral ivermectin has been cited as an effective treatment for demodicosis in humans,12,14–16 and dogs,17,18 as well as for rosacea associated with Demodex mite infestation.19–22 Nevertheless, no study has been conducted to assess its effectiveness in treating human demodicosis.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of oral ivermectin on clinical symptoms and Dds of patients with demodicosis.

Patients and Methods

This study encompassed 40 patients aged 18 to 45 who visited our clinic and were diagnosed with demodicosis. We secured Ethics Committee approval, and all participants provided informed consent. All patients underwent a thorough medical history and a skin examination by a dermatologist. The diagnosis of demodicosis is based on the clinical presentation and demonstrating the presence of live Demodex mites ≥ 5/cm².5 All patients were divided into two groups of 20 based on their detected Dds. One group with Dds < 20 D/cm2, while the other had Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2.

Demodex Detection

During the initial consultation and follow-up appointments, each patient underwent a Standardized Skin Surface Biopsy (SSSB) on both cheeks. The procedure started by cleaning the sampling area with mild liquid soap and the glass slides with 70% alcohol. The sampling sites were consistently chosen at the same location from the skin lesions on both cheeks. For the SSSB, a 1 cm2 square marked slide coated with cyanoacrylate glue was placed on each cheek for 1 minute before gently removing it. Subsequently, immersion oil was applied to the slide, which was then covered with a cover slip for microscopic examination. To calculate Dd, the alive larvae, nymphs, or adults of D. folliculorum or D. brevis within a 1 cm2 marked area from each cheek was counted and averaged from the sum of two samples from both cheeks (D/cm²).

Clinical Improvement Based on Quartile Grading Scale

An independent dermatologist assessed clinical improvement using the Quartile Grading Scale (QGS). Results were graded based on percentage improvement as follows: Grade 0 = no improvement, Grade 1 = fairly improvement (1–25%), Grade 2 = moderate improvement (26–50%), Grade 3 = good improvement (51–75%), and Grade 4 = excellent improvement (76–100%).

Intervention

Both patient groups were given oral ivermectin (200 µg/kg/week) until they achieved excellent clinical improvement (Grade 4 on the QGS) and Dds ≤ 5 D/cm2 or had already been taking ivermectin for 8 weeks. During the study, none of the patients used any additional topical medications.

All patients were followed up with the same dermatologist to evaluate the clinical improvement and Dds every two weeks for four sessions (Weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8).

We considered clinical remission when the patient experienced an excellent clinical improvement (grade 4 of the QGS) and Dds ≤ 5 D/cm2 after ivermectin treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were reported as mean and standard deviation for normally distributed data, median and interquartile range (IQR) for time duration (days) in numeric data, and frequency and percentage for categorical data. Fisher’s exact test and independent t-test were performed to compare demodicosis patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 versus those with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2. A Log rank test was conducted to compare the median duration from treatment initiation to clinical remission after ivermectin treatment (days) between the two groups.

Statistical software with IBM, Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS program), version 22.0, was analyzed. The p-value with less than 0.05 was reported as statistically significant.

Results

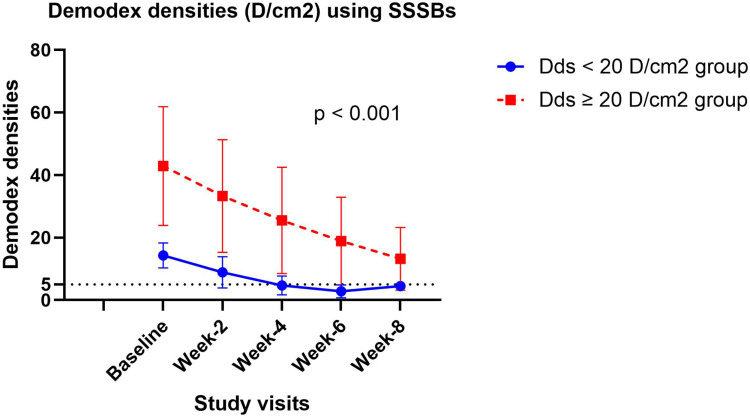

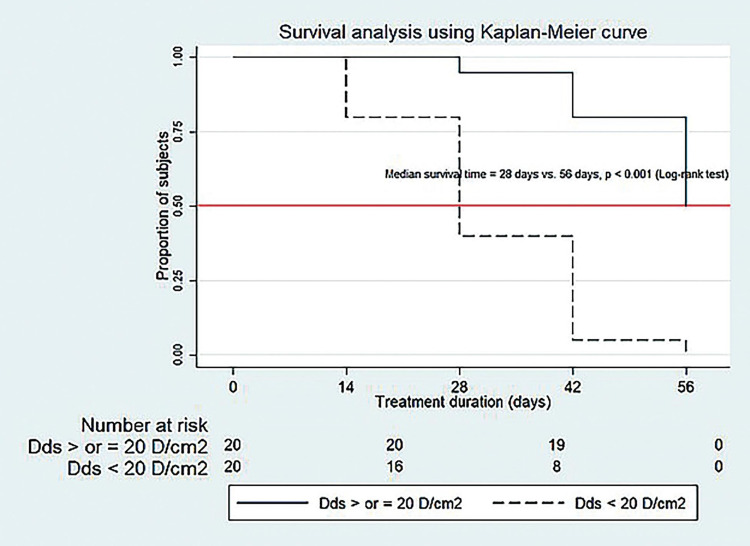

A total of 40 patients with demodicosis were included in this study: 20 had Dds < 20 D/cm2 and 20 had Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 at the baseline visit. Their mean age was 33.9 years. Sixty percent were women (24/40). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding mean age or sex. The only two clinically significant differences were rough skin and a burning sensation. There have been no patients who missed any follow-up visits or discontinued treatment. The baseline clinical characteristics of the patients in each group are summarized in Table 1. At the 2-week and 4-week follow-ups, significantly more patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 showed good and excellent clinical improvement compared to those with Dds ≥20 D/cm2 (p=0.008, p=0.005). However, in the 6-week and 8-week follow-ups, the two groups had no significant difference in the number of patients with good and excellent clinical improvement (p=1.000). By the end of the 8-week follow-up, 100% (20/20) of patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 and 90% (16/20) of patients with Dds ≥20 D/cm2 showed excellent improvement, as illustrated in Table 2. After a two-week oral ivermectin treatment, all patients demonstrated a decrease in mean Dds, which persisted throughout the follow-up. At the 8-week follow-up, patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 experienced a reduction in mean Dds of ≤ 5 D/cm2, while the mean Dds in patients with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 remained > 5 D/cm2.(Figure 1). At the end of the study, 75% (30/40) of patients achieved clinical remission, showing excellent clinical improvement with Dds ≤ 5 D/cm2. All 20 patients (100%) with Dds < 20 D/cm2 experienced clinical remission. However, 10 out of the 20 patients (50%) with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 achieved clinical remission; 6 out of 20 patients (30%) showed excellent clinical improvement but still had Dds > 5 D/cm2, and 4 out of 20 patients (20%) had good clinical improvement with Dds > 5 D/cm2. The clinical remission rate was significantly higher in patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 compared to those with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 at the 2-week, 4-week, and 6-week follow-ups (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference at the 8-week follow-up (p=0.412) (Table 3). The median time to clinical remission after receiving oral ivermectin treatment was significantly shorter in patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 (28 days) compared to those with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 (56 days) with p <0.001, as shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics Between Demodicosis Patients with Demodex Densities (Dds) < 20 D/cm2 and Demodex Densities ≥ 20 D/cm2 at the Baseline Visit

| Clinical Characteristics | Dds < 20 D/cm2 Group | Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 Group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 32.9(8.3) | 34.8(9.7) | 0.522 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

|

14(70) | 10(50) | 0.333 |

|

6(30) | 10(50) | |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | |||

|

20(100) | 19(95) | 1.000 |

|

13(65) | 11(55) | 0.748 |

|

9(45) | 17(85) | 0.019 |

|

7(35) | 3(15) | 0.273 |

|

2(10) | 2(10) | 1.000 |

|

1(5) | – | 0.005 |

|

1(5) | 3(15) | 0.605 |

|

1(5) | 3(15) | 0.605 |

|

– | 1(5) | 1.000 |

|

1(5) | 3(15) | 0.605 |

Table 2.

Clinical Improvement Assessment Using the Quartile Grading Scale (QGS) in Demodicosis Patients with Demodex Densities (Dds) < 20 D/cm2 and Demodex Densities ≥ 20 D/cm2 at Different Visits

| Visit | QGS | Dds < 20 D/cm2 Group | Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 Group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Week-2 visit | ||||

| 1= fairly improvement (1–25%) | 2(10) | 11(55) | 0.008 | |

| 2= moderate improvement (26–50%) | 10(50) | 8(40) | ||

| 3= good improvement (51–75%) | 4(20) | 1(5) | ||

| 4= excellent improvement (76–100%) | 4(20) | |||

| Week-4 visit | ||||

| 1= fairly improvement (1–25%) | 0.005 | |||

| 2= moderate improvement (26–50%) | 1(6.2) | 10(50) | ||

| 3= good improvement (51–75%) | 7(43.8) | 8(40) | ||

| 4= excellent improvement (76–100%) | 8(50) | 2(10) | ||

| Week-6 visit | ||||

| 1= fairly improvement (1–25%) | 1.000 | |||

| 2= moderate improvement (26–50%) | ||||

| 3= good improvement (51–75%) | 11(57.9) | |||

| 4= excellent improvement (76–100%) | 8(100) | 8(42.1) | ||

| Week-8 visit | ||||

| 1= fairly improvement (1–25%) | 1.000 | |||

| 2= moderate improvement (26–50%) | ||||

| 3= good improvement (51–75%) | 4(25) | |||

| 4= excellent improvement (76–100%) | 1(100) | 12(75) | ||

Figure 1.

Demodex densities (D/cm2) using Standardized Skin Surface Biopsies (SSSBs) in demodicosis patients with Demodex densities < 20 D/cm2 and Demodex densities ≥ 20 D/cm2 at baseline, week 2, week 4, week 6, and week 8.

Table 3.

Comparison of Clinical Remission Rate by Clinical Improvement at Grade 4 of the Quartile Grading Scale (QGS) and Demodex Densities (Dds) ≤ 5 D/cm2 After Ivermectin Treatment in Demodicosis Patients with Demodex Densities < 20 D/cm2 and Demodex Densities ≥ 20 D/cm2 at Different Visits

| Clinical Remission Rate | Dds < 20 D/cm2 Group | Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 Group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Week-2 | 4(20.0) | - | 0.053 |

| Week-4 | 8(50.0) | 1(5) | 0.003 |

| Week-6 | 7(87.5) | 3(15.8) | 0.001 |

| Week-8 | 1(100) | 6(37.5) | 0.412 |

Figure 2.

Comparison of median time to clinical remission by clinical improving at least grade 4 of the Quartile Grading Scale (QGS) and Demodex densities ≤ 5 D/cm2 after ivermectin treatment.

Discussion

Dermatologists often find demodicosis challenging to treat due to its high recurrence rate and the difficulty in normalizing the Dd even after clinical improvement.11,12,16–23 The ultimate goal of treating demodicosis is to cure clinical symptoms and restore the Dd to a normal level to prevent recurrence.

Ivermectin is an antiparasitic medicine effective against a wide range of endoparasites and ectoparasites, including Strongyloides stercoralis, Ancylostoma braziliense, Sarcoptes scabies, Demodex mites, and more. It blocks trans-synaptic chemical transmission through glutamate-gated anion channels, resulting in parasite paralysis and death. Ivermectin is harmless to humans because its targets are only present in the central nervous system, which it cannot access due to the blood-brain barrier.24–26

Although ivermectin is commonly used to treat demodicosis, there are no studies regarding its effectiveness and appropriate dosage regimen. Reported cases have been treated with two doses of ivermectin at a dosage of 200–250 µg/kg orally, given one week apart, similar to the treatment for scabies.14–16,27 In some cases, the treatment plan involved repeated doses given every one or two weeks, 2–5 times.24,27 This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of oral ivermectin on clinical symptoms and Dds in patients with demodicosis.

We divided patients into two groups based on the severity of Demodex infestation using the Dd level detected by SSSB to compare their response to ivermectin treatment. Based on our experience, patients with Dds ≥20 D/cm2 often exhibit more severe clinical symptoms and find ≥ 5 mites in a single hair follicle from their SSSB. In contrast, patients with Dds <20 D/cm2 typically have only 1–2 mites. However, this number may not be the standard number for other centers. The SSSB result may vary depending on the technique used, the examination site, the type of glue, and how the skin is cleaned before the examination.

The mean Dds was 14.3 (4.0) in those with Dds < 20 D/cm2, significantly lower than 42.9 (19.0) in patients with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2. Most patients experienced erythematous patches with dry, scaly, and rough skin. The only two clinically significant differences between the two groups were that patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 reported a burning sensation more frequently, while those with Dds > 20 D/cm2 exhibited rough skin symptoms more often.

We observed that a longer duration of treatment resulted in a more significant improvement in clinical symptoms and a reduction in Dds during follow-up visits.

Concerning clinical improvement, some patients with Dds <20 D/cm2 showed excellent improvement within two weeks, while those with Dds ≥20 D/cm2 required at least four weeks of treatment. At the end of the 8-week follow-up, 90% of the patients achieved excellent clinical improvement. 100% of patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 showed excellent clinical improvement, while 80% of patients with Dds ≥20 D/cm2 demonstrated the same.

These results were superior to those of the previous study in which patients received two doses of 200 µg/kg of oral ivermectin one week apart. After a 4-week follow-up, 21.7% showed no clinical improvement, 33.3% had marked improvement, and 45% achieved complete remission.16

In terms of Dd normalization, 77.5% (31/40) of patients in our study achieved a normal level of ≤ 5 D/cm2, compared to only 55% (33/60) of patients who received only two doses of oral ivermectin from the previous study.16

The mean Dds decreased in both patient groups after two weeks of treatment and continued to decrease throughout the 8-week follow-up period. Patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 reached a mean Dds of ≤5 D/cm2 in 4 weeks, while those with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 consistently remained >5 D/cm2.

These results are in line with the previous study, which discovered that all patients experienced a decrease in mean Dds over the 4-week follow-up period after receiving two doses of 200 µg/kg of oral ivermectin. Among acne patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2, the mean Dds dropped to ≤ 5 D/cm2 within six weeks after starting treatment. However, rosacea patients with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 remained >5 D/cm2.16

In our study, 75% of the patients achieved clinical remission. All patients with Dds < 20 D/cm2 showed clinical remission, while 50% of those with Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2 experienced the same. The median time to achieve remission was 28 days for Dds < 20 D/cm2 and 56 days for Dds ≥ 20 D/cm2. These indicated that patients with higher Dds require a longer treatment period with oral ivermectin, and the time to achieve clinical remission is correlated with the initial Dd level.

This study is consistent with the treatment of demodicosis in dogs, showing that longer treatment leads to a greater chance of remission. All 12 dogs given a daily oral dose of 0.6 mg/kg of ivermectin were completely cured and tested negative for skin scrapings after a median treatment period of 10 weeks, ranging from 6 weeks to 5 months.17

Ivermectin is effective against adult Demodex mites but not their eggs. Its half-life is only 36 hours,28 while the life cycle of the mite is about 14–18 days from egg to larval stage and then to the adult stage. Therefore, a single dose of oral ivermectin is not sufficient. Our findings support a previous study that suggested a treatment regimen for demodicosis should last at least six weeks to cover two Demodex life cycles.29

Notably, at the end of the study, six cases still had Dds > 5 D/cm² despite showing excellent clinical improvement. This may be due to subclinical demodicosis, which might require a longer treatment duration.30 Another possibility is that the elevated Dd level in these patients may be their normal (> 5 D/cm²). Research has established that the HLA-A2 and Cw2 phenotypes significantly influence the immune response and determine susceptibility to demodicosis.31 It is also possible that this group of patients has underlying issues that require further investigation.

An eight-week follow-up is too short to assess ivermectin’s long-term effects and demodicosis’s potential recurrence. Questions about whether individuals with abnormal Dds are at a higher risk of recurrence than those with normal levels are beyond the scope of this study. We hope future research with a longer follow-up duration will explore these critical issues further.

Conclusions

Oral ivermectin effectively improves clinical symptoms and normalizes Dds in patients with demodicosis. Patients with higher Dds require a longer treatment period than those with lower Dds. The time taken to achieve clinical remission is directly linked to the initial Dds level.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Mae Fah Luang University for providing financial support for the publication charges of this work.

Funding Statement

This article has no funding source.

IRB Approval Status

The present study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects had given their written informed consent, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Research Committee of Mae Fah Luang University, approval number COA 60/2024.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Forton F, Germaux MA, Brasseur T, et al. Demodicosis and rosacea: epidemiology and significance in daily dermatologic practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karincaoglu Y, Bayram N, Aycan O, et al. The clinical importance of Demodex folliculorum presenting with nonspecific facial signs and symptoms. J Dermatol. 2004;31(8):618–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akilov OE, Butov YS, Mumcuoglu KY. A clinico-pathological approach to the classification of human demodicosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3(8):607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05725.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paichitrojjana A, Chalermchai T. The association between acne vulgaris, acne vulgaris with nonspecific facial dermatitis, and demodex mite presence. Clin Cosmet Invest Dermatol. 2024;17:137–146. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S450540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forton F, Seys B. Density of Demodex folliculorum in rosacea: a case-control study using standardized skin-surface biopsy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128(6):650–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang YS, Huang YC. Role of Demodex mite infestation in rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(3):441–447.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fromstein SR, Harthan JS, Patel J, et al. Demodex blepharitis: clinical perspectives. Clin Optom. 2018;10:57–63. doi: 10.2147/OPTO.S142708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun CH, Yun JH, Baek JO, et al. Demodex mite density determinations by standardized skin surface biopsy and direct microscopic examination and their relations with clinical types and distribution patterns. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(2):137–142. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.2.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominey A, Tschen J, Rosen T, et al. Pityriasis folliculorum revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(1):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70152-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong H, Duncan LD. Cytologic findings in Demodex folliculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34(3):232–234. doi: 10.1002/dc.20426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob S, VanDaele MA, Brown JN. Treatment of Demodex-associated inflammatory skin conditions: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(6):e13103. doi: 10.1111/dth.13103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chudzicka-Strugała I, Gołębiewska I, Brudecki G, et al. Demodicosis in different age groups and alternative treatment options-a review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(4):1649. doi: 10.3390/jcm12041649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paichitrojjana A. Demodex: The worst enemies are the ones that used to be friends. Dermatol Reports. 2022;14(3):9339. doi: 10.4081/dr.2022.9339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forstinger C, Kittler H, Binder M. Treatment of rosacea-like demodicidosis with oral ivermectin and topical permethrin cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5 Pt 1):775–777. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70022-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzchuh FG, Hida RY, Moscovici BK, et al. Clinical treatment of ocular Demodex folliculorum by systemic ivermectin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(6):1030–1034.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salem DA, El-Shazly A, Nabih N, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of oral ivermectin in comparison with ivermectin–metronidazole combined therapy in the treatment of ocular and skin lesions of Demodex folliculorum. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(5):e343–e347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ristic Z, Medleau L, Paradis M, et al. Ivermectin for treatment of generalized demodicosis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1995;207(10):1308–1310. doi: 10.2460/javma.1995.207.10.1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller RS, Bensignor E, Ferrer L, et al. Treatment of demodicosis in dogs: 2011 clinical practice guidelines. Vet Dermatol. 2012;23(2):86–e21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2011.01026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rebora A. The management of rosacea. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(7):489–496. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203070-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samer AD, Dhoha Kh A. The efficacy and safety of oral ivermectin in the treatment of inflammatory rosacea: a clinical therapeutic trial. Iranian J Dermatol. 2018;21(2):37–42. doi: 10.22034/ijd.2018.98349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noguera-Morel L, Gerlero P, Torrelo A, et al. Ivermectin therapy for papulopustular rosacea and periorificial dermatitis in children: a series of 15 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):567–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernández-Martín Á. Oral Ivermectin to treat papulopustular rosacea in a immunocompetent patient. Tratamiento con ivermectina oral en un paciente inmunocompetente con rosácea pápulo-pustulosa. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108(7):685–686. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trave I, Micalizzi C, Cozzani E, et al. Papulopustular rosacea treated with ivermectin 1% cream: remission of the Demodex mite infestation over time and evaluation of clinical relapses. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12(4):e2022201. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1204a201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA. Ivermectin: pharmacology and application in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(12):981–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skopets B, Wilson RP, Griffith JW, et al. Ivermectin toxicity in young mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1996;46(1):111–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roche D, O’Connor C, Murphy M. Ivermectin in dermatology: why it ‘mite’ be useless against COVID-19. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46(7):1327–1328. doi: 10.1111/ced.14704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Truchuelo-Díez MT, Alcántara J, Carrillo R, et al. Demodicosis successfully treated with repeated doses of oral ivermectin and permethrin cream. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(5):777–778. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baraka OZ, Mahmoud BM, Marschke CK, et al. Ivermectin distribution in the plasma and tissues of patients infected with Onchocerca volvulus. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50(5):407–410. doi: 10.1007/s002280050131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng AM, Sheha H, Tseng SC. Recent advances on ocular Demodex infestation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):295–300. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forton FMN, De Maertelaer V. Treatment of rosacea and demodicosis with benzyl benzoate: effects of different doses on Demodex density and clinical symptoms. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(2):365–369. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mumcuoglu KY, Akilov OE. The role of HLA A2 and Cw2 in the pathogenesis of human demodicosis. Dermatology. 2005;210(2):109–114. doi: 10.1159/000082565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]