Abstract

Purpose:

To investigate HIV transmission potential from a cluster of HIV infections among men who have sex with men to persons who inject drugs in 15 West Virginia counties. These counties were previously identified as highly vulnerable to rapid HIV dissemination through injection drug use (IDU) associated with high levels of opioid misuse.

Methods:

We interviewed persons with 2017 HIV diagnoses about past-year risk behaviors and elicited sexual, IDU, and social contacts. We tested contacts for HIV and assessed risk behaviors. To determine HIV transmission potential from persons with 2017 diagnoses to persons who inject drugs, we assessed viral suppression status, HIV status of contacts, and IDU risk behaviors of persons living with HIV and contacts.

Results:

We interviewed 78 persons: 39 with 2017 diagnoses and 39 contacts. Overall, 13/78 (17%) injected drugs in the past year. Of 19 persons with 2017 diagnoses and detectable virus, 9 (47%) had more than or equal to 1 sexual or IDU contacts of negative or unknown HIV status. During the past year, 2/9 had injected drugs and shared equipment, and 1/9 had more than or equal to 1 partner who did so.

Conclusions:

We identified IDU risk behavior among persons with 2017 diagnoses and their contacts. West Virginia HIV prevention programs should continue to give high priority to IDU harm reduction.

Keywords: Injection drug use, HIV prevention, Sexual network, Epidemiology, Investigation

Introduction

Rural, low HIV prevalence settings in the United States are increasingly vulnerable to new HIV transmissions because of epidemic levels of opioid use and increasing prevalence of injection opioid use [1,2]. Opioid misuse and injection are particularly problematic in West Virginia, where in 2017, there were 49.6 opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 persons, the highest rate in the country [3]. Opioids are increasingly injected in West Virginia as in other parts of the rural United States [4–6]; as an indication, the rate of acute Hepatitis C in West Virginia was more than five times the national average in 2016 [7].

Aiming to prevent increases in HIV infections caused by unsafe injection opioid use following a well-documented outbreak in Scott County, Indiana [8], the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created a “vulnerability index” to identify counties at high risk for rapid HIV dissemination due to injection drug use. Over half (51%) of West Virginia’s 55 counties were listed in the top 5% of the country’s most vulnerable counties [2].

During the first three-quarters of 2017, amid heightened awareness of the opioid crisis, the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources (WV DHHR) identified 40 persons with recently diagnosed HIV in 15 geographically contiguous counties. By October, the number of HIV diagnoses in these counties had surpassed year-end totals for 2015 and 2016 [9]. Nearly all 15 counties were among the most vulnerable to rapid HIV dissemination in the country, according to CDC’s index [2].

Concerns about the possibility of an HIV outbreak like the one that occurred in Indiana prompted further investigation of persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017. According to reported lifetime risk from West Virginia surveillance data, most (60%) people with HIV diagnosed in 2017 likely acquired HIV through male-to-male sexual contact, 9% likely acquired HIV through injection drug use (IDU), and an additional 5% through either male-to-male sexual contact or IDU [9]. However, data on current IDU behaviors of contacts were unavailable. To assess potential for further increases in HIV infections in this area, we conducted a network investigation to assess sexual and IDU risk among persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017 and their contacts. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether bridging of HIV risk was occurring between men who have sex with men (MSM) and one or more networks of persons who inject drugs (PWID). Bridging is defined for the purpose of this analysis as shared HIV transmission risk from a population with one primary HIV risk factor to a population with another primary risk factor through people exhibiting both risk factors.

Materials and methods

This network investigation included persons with HIV diagnosed in the 15 counties in 2017 and their sexual, IDU, and social contacts elicited by disease intervention specialists (DIS) during partner services interviews. We defined social contacts as anyone the interviewed person named who may have benefited from an HIV test, including friends, family members, or other sexual/IDU partners of their partners. Standard partner services operations in West Virginia entail interviewing only contacts of persons with diagnosed HIV who also test HIV-positive. From October 16 to November 9, 2017, we intensified partner services efforts in the 15 counties by eliciting an expanded network of contacts and asking additional questions about past 12-month IDU behavior. Collecting information for past-year behavior is standard practice for DIS interviews, although reinterviewing previously interviewed persons is not.

DIS used standard methods for locating and contacting persons for interview, including the use of phone calls, letters, in person contact, and contact through social media. During this time period, contacts of persons with diagnosed HIV (first-generation contacts) were tested for HIV and, regardless of their HIV status, interviewed by DIS for risk behaviors and elicitation of contacts (second-generation contacts). DIS also tested and interviewed second-generation contacts. A few second-generation contacts also named their contacts (n = 8 contacts); for the purposes of this analysis, these contacts were also defined as second-generation contacts. These contacts were not elicited purposively by the DIS but were included for investigational purposes because they were reachable for interview and determined to have similar levels of HIV risk to the second-generation contacts. Contacts who had HIV diagnosed in 2017 were classified as having a 2017 diagnosis and not as contacts.

A person was considered interviewed if they were interviewed by a DIS in 2017. This is an important distinction for contacts with HIV diagnosed before 2017. Because we were assessing current risk for transmission, we did not include data collected before 2017 because of noncurrent risk behavior. Contacts diagnosed with HIV who were interviewed before 2017 were not considered interviewed in our analyses.

Demographic characteristics (Table 1) were self-reported during DIS interviews, whereas clinical characteristics were available from surveillance data (Table 2). Past 12-month risk behaviors (Table 3) were also self-reported during DIS interviews. All persons with diagnosed HIV had an initial positive rapid test or standard blood test result that was later confirmed by Western blot at the West Virginia state laboratory. Transmission category (based on reported lifetime risk behaviors) and viral suppression (defined as <200 copies/mL, or undetectable) status were abstracted from West Virginia’s HIV surveillance data. Viral suppression data were last abstracted on February 15, 2018, to allow for reporting delays. The most recent viral load for each person up to this date was included in analyses. Linkage to care was defined as having any viral load measurement available in surveillance data.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-positive persons with HIV diagnosed in 15 counties (n = 47) and their sexual, injection drug, or social contacts (n = 192), West Virginia, 2017

| Characteristic | HIV-positive persons with 2017 diagnoses |

Contacts of persons with 2017 diagnoses |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total Sex |

47 | 192 |

| Male | 41 (87) | 157 (89) |

| Female | 6 (13) | 19 (11) |

| Unknown Age (y) |

0 (0) | 16 |

| 13–19 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| 20–29 | 26 (55) | 53 (54) |

| 30–39 | 10 (21) | 29 (30) |

| 40–49 | 5 (11) | 11 (11) |

| ≥50 | 5 (11) | 4 (4) |

| Unknown Race/ethnicity* |

0 (0) | 94 |

| Black/African-American | 13 (28) | 12 (9) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| White | 33 (70) | 109 (87) |

| Other/Multiple race | 1 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Unknown HIV status |

0 (0) | 66 |

| Negative | - | 56 (29) |

| Positive | 47 (100) | 23† (12) |

| Unknown Interviewed by DIS |

- | 113 (59) |

| Yes | 39 (83) | 39 (20) |

| No | 8 (17) | 153 (80) |

Race/ethnicity categories are mutually exclusive; Hispanic/Latinos can be of any race.

HIV diagnosed before 2017; contacts with HIV diagnosed in 2017 were included in HIV-positive persons with 2017 diagnoses. The unknown group is included in percentage calculations for HIV status because the sizable fraction of contacts with unknown status is a notable finding from the investigation to date.

Table 2.

HIV-related characteristics of persons with HIV diagnosed in 15 counties, West Virginia, 2017 (n = 47)

| Characteristic | HIV-positive persons with 2017 diagnoses |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Total Transmission category |

47 |

| Male-to-male sexual contact (MSM) | 29 (62) |

| Injection drug use (IDU) | 5 (11) |

| MSM and IDU | 4 (8) |

| Heterosexual male | 2 (4) |

| Heterosexual female | 1 (2) |

| Other/Unknown AIDS at HIV diagnosis |

6 (13) |

| Yes | 10 (21) |

| No | 37 (79) |

| Unknown | 0 |

| Evidence of viral suppression (<200 copies/mL or undetectable) at last test during past 12 mo | |

| Yes | 22 (47) |

| No | 17 (36) |

| Unknown (no viral load test available in surveillance data) | 8 (17) |

Table 3.

Behavioral characteristics of persons interviewed by disease intervention specialists (DIS): HIV-positive persons with HIV diagnosed in 15 counties (n = 39) and their sexual, injection drug, or social contacts (n = 39), West Virginia, 2017

| Past 12- mo behaviors | HIV-positive persons with 2017 diagnoses |

Contacts of persons with 2017 diagnoses |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total | 39 | 39 |

| Injected drugs | ||

| Yes | 5 (13) | 8 (21) |

| No | 33 (87) | 30 (79) |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Shared injection equipment | ||

| Yes | 3 (8) | 6 (16) |

| No | 33 (92) | 31 (84) |

| Unknown | 3 | 2 |

| Sex with male partner* | ||

| Yes | 29 (74) | 33 (87) |

| No | 10 (26) | 5 (13) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 |

| Sex with female partner† | ||

| Yes | 11 (29) | 9 (27) |

| No | 27 (71) | 25 (73) |

| Unknown | 1 | 5 |

| Sex with anonymous partner | ||

| Yes | 14 (37) | 13 (42) |

| No | 24 (63) | 18 (58) |

| Unknown | 1 | 8 |

| Condomless sex | ||

| Yes | 33 (85) | 24 (73) |

| No | 6 (15) | 9 (27) |

| Unknown | 0 | 6 |

| Exchanged sex for drugs/money | ||

| Yes | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| No | 37 (95) | 31 (100) |

| Unknown | 0 | 8 |

| Had sex with PWID | ||

| Yes | 7 (19) | 9 (30) |

| No | 29 (81) | 21 (70) |

| Unknown | 3 | 9 |

| Incarcerated | ||

| Yes | 4 (11) | 2 (7) |

| No | 34 (89) | 26 (93) |

| Unknown | 1 | 11 |

Among HIV-positive males: 24 Yes, 10 No, 0 Unknown; among HIV-positive females: 5 Yes, 0 No, 0 Unknown; among male contacts: 32 Yes, 4 No, 1 Unknown; among female contacts: 1 Yes, 1 No, 0 Unknown.

Among HIV-positive males: 11 Yes, 23 No, 0 Unknown; among HIV-positive females: 0 Yes, 5 No, 0 Unknown; among male contacts: 9 Yes, 24 No, 4 Unknown; among female contacts: 0 Yes, 1 No, 1 Unknown.

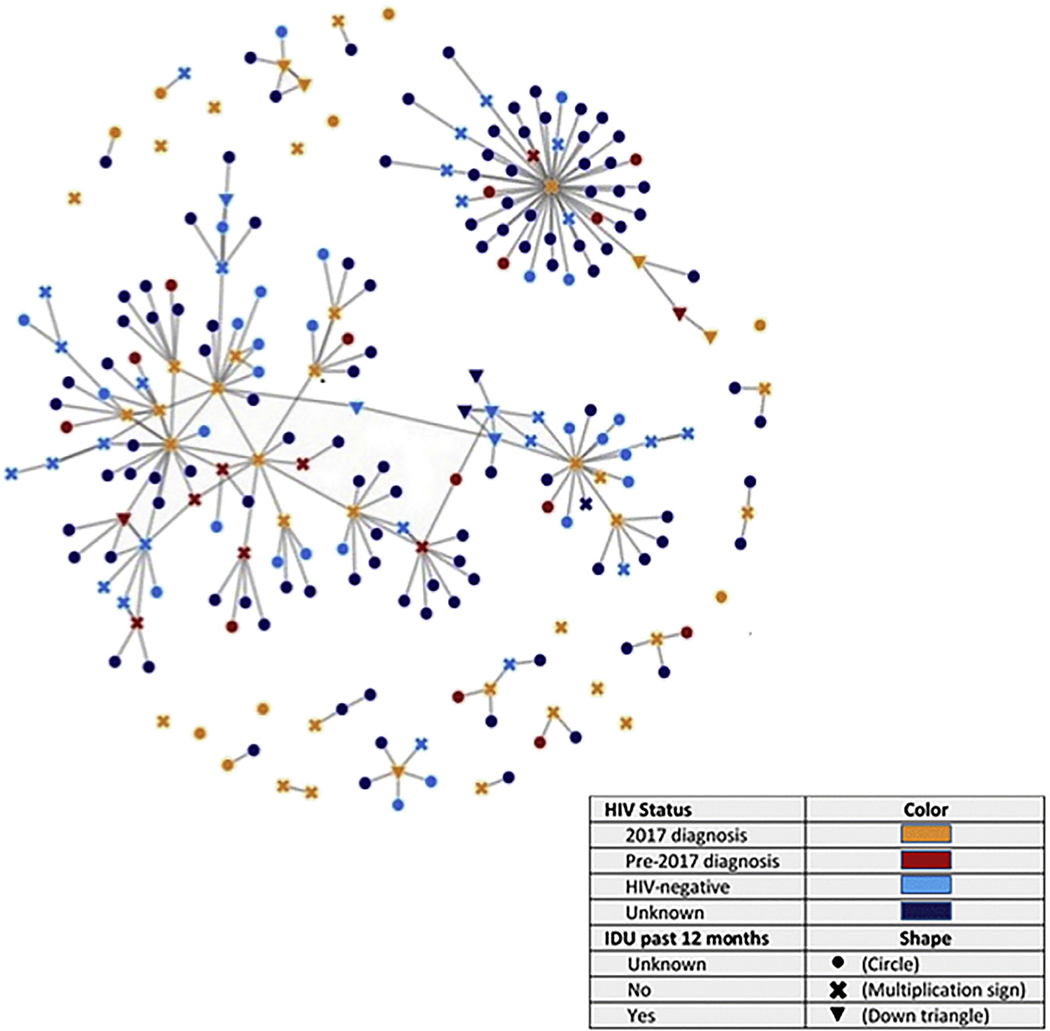

We described demographic and clinical characteristics of persons with HIV diagnosed during 2017 and demographic characteristics of their contacts. We also described past 12-month behavioral characteristics among those interviewed by a DIS. Connections between persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017 and their contacts (including persons with HIV diagnosed before 2017) are illustrated and described by HIV status and past 12-month IDU risk in a network diagram produced in MicrobeTrace [10]. To determine HIV transmission potential from persons with 2017 diagnoses to PWID, we assessed viral suppression status, HIV status of contacts, and IDU risk behaviors of persons living with HIV and contacts.

Results

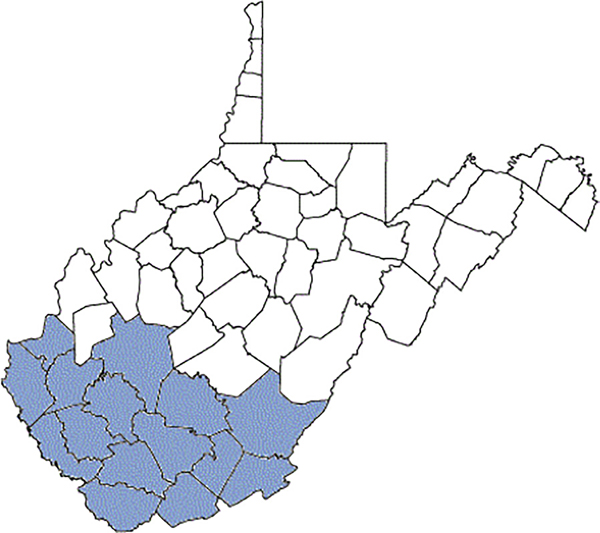

There were 47 persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017 in the 15 southern West Virginia counties of interest based on their county of residence at diagnosis (Fig. 1). The majority (87%) were male (Table 1). Most persons with HIV diagnoses were aged 20–29 years (55%) with 30–39 years (21%) being the second largest age group, and 70% were non-Hispanic white. As of early February 2018, 83% of persons with an HIV diagnosis had been interviewed by a DIS. The 39 persons who were interviewed by DIS named 192 sexual, injection drug, or social contacts. Like persons with 2017 diagnoses, most contacts were male (89%) and aged 20–39 years (84%). Nearly 87% of contacts were non-Hispanic white, and 12% had a previous HIV diagnosis. DIS located and interviewed 20% (39/192) of contacts. Other persons with 2017 diagnoses and contacts could not be located or reached for interview.

Fig. 1.

Fifteen counties of intensified HIV contact tracing efforts from October 16 to November 9, 2017–West Virginia.

Based on the lifetime risk behaviors of persons with 2017 diagnoses, 62% likely acquired HIV through male-to-male sexual contact, 11% through injection drug use, and 8% through either male-to-male sexual contact or injection drug use (Table 2). More than one-fifth (21%) of persons had HIV stage 3 [AIDS] at the time of their HIV diagnosis, 47% had evidence of viral suppression as of February 2018, whereas another 36% were linked to HIV care but not yet achieved viral suppression.

DIS interviewed 78 people as part of this investigation, of whom half were persons with 2017 diagnoses and half were their contacts (Table 3). In the 12 months before interview, 13% of persons with 2017 diagnoses and 21% of their contacts injected drugs, whereas 8% of persons with 2017 diagnoses and 16% of their contacts shared needles or other injection equipment. Most men had sex with at least one male partner (71% of males with diagnosed HIV and 86% of male contacts), whereas fewer had sex with female partners (32% of males with diagnosed HIV and 24% of male contacts). A larger proportion of persons with 2017 diagnoses had anal or vaginal condomless sex than contacts (85% vs. 73%, respectively). More contacts than persons with HIV had sex with a PWID (30% vs. 19%, respectively).

Figure 2 shows the network of the 47 persons with diagnosed HIV and their 192 contacts. Of the contacts, 149 (78%) were first-generation contacts and 43 (22%) were second-generation contacts. Color and shape combinations used for network nodes (i.e., persons) allow one to simultaneously discern past 12-month IDU behavior and HIV case status (persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017 and pre-2017 are shown separately in orange and red, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Network of 2017 HIV diagnoses and contacts by HIV status and IDU in the past 12 months – West Virginia, 15 counties.

The network diagram was built from persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017 and included 14/47 (30%) persons who were either not interviewed (n = 8) or did not list any contacts (n = 6); these nodes are shown in the diagram as singletons. There are 245 connections between nodes. The average degree (i.e., number of direct links or connections) for all nodes in the network is 2.1. Among persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017, 10 (21%) had only one contact, 8 (17%) had 2–3 contacts, and 15 (32%) had at least four contacts.

Most (83%) of the connections were between sexual contacts (data not shown). Another 4% were between needle-sharing partners, whereas 3% were between sexual and needle-sharing contacts. In addition, 10% of connections were between social contacts, where the index case believed a contact could benefit from HIV testing.

There were two subclusters that were connected to one another by two nodes: one HIV-negative person with past 12-month IDU behavior and one person whose HIV infection was diagnosed before 2017 and whose IDU behavior was unknown. A third cluster included 44 contacts named by one person with a 2017 diagnosis and several of their second-generation contacts.

Thirteen people with past 12-month IDU behavior are shown by downward-facing triangles; five were persons with 2017 diagnoses, two had HIV diagnosed before 2017, four tested HIV-negative, and two had an unknown HIV status. Of the 13, nine reported using heroin or misusing prescription opioids in the past 12 months (data not shown). All 13 people with IDU risk behavior had at least one contact, and 12 had two or more contacts. Of persons with 2017 diagnoses, eight had unknown IDU risk behavior.

Figure 3 shows potential for onward HIV transmission from persons with 2017 diagnoses in terms of viral suppression status, number of sexual or IDU contacts with a discordant HIV status (negative or unknown HIV status), and risk behaviors during the past 12 months. There were 19 persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017 who were not virally suppressed and were interviewed by DIS about their partners and risk behaviors. Of these, nine (47%) had at least one sexual or IDU contact with a negative or unknown HIV status. Further, among those nine, one reported having injected drugs and shared needles or equipment, and two others had at least one discordant partner who injected drugs and shared needles or equipment during the past 12 months. An additional two persons of the nine with HIV diagnosed in 2017, who were not virally suppressed and had discordant partners reported anal or vaginal condomless sex in the past 12 months (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Risk behaviors that could result in bridging of HIV to the population of persons who inject drugs.

Discussion

An in-depth network investigation of persons diagnosed with HIV in 2017 in 15 West Virginia counties revealed that most HIV infections were likely transmitted by male-to-male sexual contact. However, interviewed persons reported moderately high levels of IDU behavior—13% of persons with a recent HIV diagnosis injected drugs in the past year, as did 21% of their interviewed contacts. In comparison, the prevalence of past-year PWID was estimated to be 0.3% in the United States [11], and 9% of persons diagnosed with HIV in the United States in 2017 reported injection drug use as their transmission category [12]. As expected, most drugs injected were opioids. Bridging of HIV risk from MSM to PWID is present, although we did not find a dense network of PWID with rapidly disseminating HIV as was documented in Scott County, Indiana [8]. However, any needle or equipment-sharing behavior among PWID in an area with high rates of opioid use and even a few HIV infections warrants serious public health concern.

Persons with HIV diagnosed in 2017 in the 15 counties of interest were demographically similar to those with recent diagnoses throughout the state. West Virginia reported 78 HIV diagnoses in 2017; at a rate of 4.3 diagnoses per 100,000 population, it had the 11th lowest HIV diagnosis rate nationally [12]. Among persons with HIV diagnosed in West Virginia during 2012–2016, 80% were male, 47% were aged younger than 35 years, 72% were non-Hispanic white, and 54% likely acquired HIV through male-to-male sexual contact, whereas 13% had some lifetime IDU risk. The demographic characteristics of persons with diagnosed HIV in West Virginia have remained relatively stable since reporting began in 1989 [13].

Rapid dissemination of HIV would overtax West Virginia’s public health system given historically low, stable background HIV prevalence. The population is widely dispersed throughout the state with few urban areas, and infectious disease physicians or other health care providers trained to care for persons living with HIV are in short supply [9]. At the time of this investigation, some key HIV surveillance data, including contact tracing and risk behavior data, were not digitized and therefore unavailable for rapid analysis. In addition, there were only three DIS working across the 15 counties, and they had many other notifiable disease responsibilities. At the current rate of HIV diagnoses, these issues are somewhat manageable, as evidenced by our finding that 50% of persons with 2017 diagnoses were already virally suppressed by early 2018, with another 36% linked to care but not yet virally suppressed. However, these infrastructural and human resources constraints do not have quick fixes and would make rapid response to an HIV outbreak challenging and resource intensive.

Because of surveillance data limitations, a network investigation was required to assess potential bridging of HIV risk between MSM and PWID. Standard DIS practice in West Virginia, as in most other states, entails interviewing only persons with diagnosed HIV. Although this practice allows assessment of how the person likely acquired HIV based on lifetime risk behaviors, it provides incomplete information for understanding ongoing transmission risk because data on risk behaviors of their HIV-negative contacts are unavailable. In addition, DIS typically only interview persons with HIV once, at the time of diagnosis. For this reason, persons in this investigation whose HIV was diagnosed before 2017 required a reinterview to collect current behavioral risk information. Interviewing first- and second-generation contacts, including persons with a previous HIV diagnosis, allowed us to assess risk for ongoing HIV transmission, rather than merely the likely mode of acquisition for persons with recently diagnosed HIV infection.

Syringe services programs (SSPs), as well as expanded HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing, are key components of harm reduction for PWID and can reduce HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmissions in this population [14–16]. The number of SSPs has increased in recent years in West Virginia [17], with plans and resources allocated toward further expansion. In 2017, West Virginia state agencies received increased funding from multiple federal agencies to expand harm reduction services, improve opioid-related surveillance activities, and conduct research to better understand risk factors for opioid misuse. These agencies include CDC [18], the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) [19], and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) [20]. In addition, a state opioid response plan was proposed in early 2018 that outlines a comprehensive approach including interventions for prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and overdose reversal [21]. Some political opposition to harm reduction programs remains, however, as evidenced by the recent suspension of a well-attended SSP in Charleston [22,23]. Continuation and expansion of HIV and HCV testing as part of harm reduction programs are critical for control of these infectious diseases among PWID.

We observed overlap between male-to-male sexual contact and IDU behavior (9% of persons living with HIV in this network investigation reported both male-to-male sex and IDU lifetime risk) and bridging of HIV risk from MSM to PWID. To prevent transmissions between these two groups, prevention programs for MSM in West Virginia remain a priority. In particular, expanded pre exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) services are needed for both MSM and PWID. At the time of this investigation, providers were offering PrEP in four of 15 counties of interest and in seven West Virginia counties overall [9]. Additional PrEP clinics are planned in collaboration with county health departments. Other HIV prevention services requiring continued bolstering include HIV testing, sexually transmitted disease testing and treatment, partner services, and care and treatment services after an HIV diagnosis.

This investigation had several limitations. First, only interviewed persons had contacts elicited, so only a partial network could be described. Named contacts may not be representative of all contacts in the network. Second, many contacts could not be located for interviewing and testing, so complete assessment of current risk behaviors and HIV status could not be obtained. We, therefore, could be underestimating the potential for bridging of HIV risk from persons (mostly MSM) with HIV diagnosed in 2017 to potential IDU contacts. Third, the timing of HIV infection among persons with 2017 diagnoses could not be ascertained, but at least 21% had AIDS at diagnoses so acquired HIV many years before this investigation. Finally, data obtained during DIS interviews were self-reported by respondents and may be subject to social desirability bias and recall error. Because of stigma surrounding HIV and MSM sexual behavior in West Virginia, respondents may have felt uncomfortable reporting contacts. Similarly, respondents may have felt uncomfortable disclosing illicit drug use because of concerns about potential prosecution. This may have resulted in under-reporting of IDU in our results and a subsequent underestimate of bridging potential.

Conclusions

In the context of the rural opioid epidemic in the United States, timely public health response to clusters of HIV infection in historically low prevalence populations is critical to prevent HIV outbreaks. Findings from West Virginia provide a cautionary tale for other areas with vulnerability to rapid dissemination of HIV infections because of injection opioid use. West Virginia state health officials acted swiftly and, in cooperation with CDC, conducted an extensive investigation to assess the likelihood of an HIV outbreak in these counties. Although we did not reveal such an outbreak, we documented bridging of HIV risk from MSM to IDU and thus the potential for future increases in HIV transmissions because of IDU risk behavior. HIV surveillance and prevention programs in jurisdictions highly affected by the opioid epidemic will need to remain vigilant to prevent opioid-related HIV infections and resultant further strains on population health and the public health system.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge support provided to this investigation by West Virginia State and County Health Department staff and additionally thank persons participating in interviews.

Funding:

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented at “Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI),” Boston, MA, March 4–7, 2018 (Hogan et al., Abstract #976LB).

Disclaimer: The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest have been declared for any author on this article.

References

- [1].Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, Suryaprasad A, Sanders KJ, Moore-Moravian L, et al. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged </=30 years - Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(17):453–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Van Handel MM, Rose CE, Hallisey EJ, Kolling JL, Zibbell JE, Lewis B, et al. County-level vulnerability assessment for rapid dissemination of HIV or HCV infections among persons who inject drugs, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;73(3):323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(5152):1419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jones CM. Trends and key correlates of prescription opioid injection misuse in the United States. Addict Behav 2018;78:145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jones CM, Christensen A, Gladden RM. Increases in prescription opioid injection abuse among treatment admissions in the United States, 2004–2013. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;176:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Young AM, Havens JR. Transition from first illicit drug use to first injection drug use among rural Appalachian drug users: a cross-sectional comparison and retrospective survival analysis. Addiction 2012;107(3):587–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for viral hepatitis - United States, 2016. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, Patel MR, Galang RR, Shields J, et al. HIV Infection Linked to Injection Use of Oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med 2016;375(3):229–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Evans ME, Labuda SM, Hogan V, Agnew-Brune C, Armstrong J, Periasamy Karuppiah AB, et al. Notes from the field: HIV infection investigation in a rural area - West Virginia, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(8):257–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boyles T, Aslakson E. MicrobeTrace. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, Holtzman D, Wejnert C, Mitsch A, et al. Estimating the number of persons who inject drugs in the united states by meta-analysis to calculate national rates of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections. PLoS One 2014;9(5):e97596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- [13].West Virginia Department of Health, Human Resources Bureau for Public Health. West Virginia HIV/AIDS surveillance report: 2017 update. Charleston, WV: WV Department of Health and Human Resources; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Aspinall EJ, Nambiar D, Goldberg DJ, Hickman M, Weir A, Van Velzen E, et al. Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43(1):235–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, Vickerman P, Hagan H, French C, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9:CD012021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wodak A, Cooney A. Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: a comprehensive review of the international evidence. Subst Use Misuse 2006;41(6–7):777–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bixler D, Corby-Lee G, Proescholdbell S, Ramirez T, Kilkenny ME, LaRocco M, et al. Access to syringe services programs - Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(18):529–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Centers for disease control, prevention. Enhanced state opioid surveillance. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/foa/state-opioid-mm.html. [Accessed 3 February 2019].

- [19].Substance abuse, mental health services administration. TI-17–014 Individual grant awards. https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/awards/2017/TI-17-014. [Accessed 3 February 2019].

- [20].National Institute on Drug Abuse. Grants awarded to address opioid crisis in rural regions 2017. https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/news-releases/2017/08/grants-awarded-to-address-opioid-crisis-in-rural-regions. [Accessed 3 February 2019].

- [21].State of West Virginia. Opioid response plan for the state of West Virginia: proposed report for public comment. Charleston, WV: WV Department of Health and Human Resources; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Beck E, Kersey L. Needle exchange program concerns some Charleston officials. Charleston Gazette-Mail 2018. https://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/health/needle-exchange-program-concerns-some-charleston-officials/article_ecf46464-a9ec-54a6-8a12-f0af06e61025.html. [Accessed 2 February 2019].

- [23].Katz J. Why a city at the center of the opioid crisis gave up a tool to fight it. N Y Times 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/04/27/upshot/charleston-opioid-crisis-needle-exchange.html. [Accessed 2 February 2019].