Abstract

Objective

To review the effectiveness of primary prevention strategies aimed at delaying sexual intercourse, improving use of birth control, and reducing incidence of unintended pregnancy in adolescents.

Data sources

12 electronic bibliographic databases, 10 key journals, citations of relevant articles, and contact with authors.

Study selection

26 trials described in 22 published and unpublished reports that randomised adolescents to an intervention or a control group (alternate intervention or nothing).

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers assessed methodological quality and abstracted data.

Data synthesis

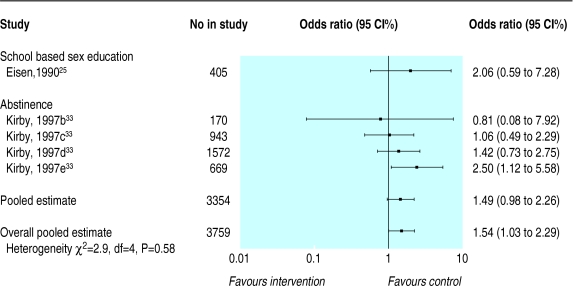

The interventions did not delay initiation of sexual intercourse in young women (pooled odds ratio 1.12; 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 1.30) or young men (0.99; 0.84 to 1.16); did not improve use of birth control by young women at every intercourse (0.95; 0.69 to 1.30) or at last intercourse (1.05; 0.50 to 2.19) or by young men at every intercourse (0.90; 0.70 to 1.16) or at last intercourse (1.25; 0.99 to 1.59); and did not reduce pregnancy rates in young women (1.04; 0.78 to 1.40). Four abstinence programmes and one school based sex education programme were associated with an increase in number of pregnancies among partners of young male participants (1.54; 1.03 to 2.29). There were significantly fewer pregnancies in young women who received a multifaceted programme (0.41; 0.20 to 0.83), though baseline differences in this study favoured the intervention.

Conclusions

Primary prevention strategies evaluated to date do not delay the initiation of sexual intercourse, improve use of birth control among young men and women, or reduce the number of pregnancies in young women.

What is already known on this topic

Unintended pregnancies among adolescents pose a considerable problem for the young parents, the child, and society

What this study adds

Primary prevention strategies evaluated to date do not delay the initiation of sexual intercourse or improve use of birth control among adolescents

Primary prevention strategies have not reduced the rate of pregnancies in adolescent women

Meta-analysis of five studies, four of which evaluated abstinence programmes, has shown an increase in pregnancies in partners of male participants

Introduction

The period between childhood and adulthood is a time of profound biological, social, and psychological changes accompanied by increased interest in sex. This interest places young people at risk of unintended pregnancy, with consequences that present difficulties for the individual, family, and community.1 There are negative associations between early childbearing and numerous economic, social, and health outcomes.2–5 For society, unintended early childbearing has tremendous social and financial costs.6,7 In response, communities have implemented various pregnancy prevention strategies for adolescents, several of which have been evaluated. Discrepant results of these evaluations have left the effectiveness of such strategies in doubt.

A recent meta-analysis found that school sex education programmes improved sexual knowledge.8 Several reviews have examined the effectiveness of pregnancy prevention programmes for adolescents in improving sexual behaviour.2,9–14 All of these reviews included non-randomised observational studies; most did not include unpublished studies; and only one statistically combined study findings, although most of the studies were surveys.14

We undertook a systematic review that included non-published studies to avoid publication bias,15,16 excluded non-randomised studies that tend to inflate treatment effects,17 and provided a summary measure to facilitate interpretation.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We included published and unpublished randomised controlled trials of adolescents (ages 11 to 18 years) that evaluated pregnancy prevention programmes including sex education classes, school based clinics, family planning clinics, and community based programmes. We included studies that evaluated delay in initiation of sexual intercourse, consistent use of birth control, or avoidance of unintended pregnancy. All studies took place in North America, Australia, New Zealand, or Europe (excluding Eastern Europe) and were published in any language.

We excluded studies that evaluated prevention programmes offered in colleges or universities, those that evaluated interventions designed to prevent a second pregnancy, and those that evaluated only knowledge and attitudes. We also excluded studies that measured only condom use because study participants may have been using other methods of birth control and studies that measured only births because they omitted abortions.

Search for primary studies

Our literature search extended from 1970 to December 2000. We began with an extensive database we had established over the eight years of the McMaster Teen Project, a study that implemented and evaluated a sex education intervention.18 We searched the following computerised databases: CATLINE, CINAHL, conference papers index, dissertation abstracts online, Embase, ERIC, Medline, NTIS, POPLINE, PsycINFO, sociological abstracts, and the Cochrane controlled trials register. We reviewed the contents lists of the following journals from January 1993 to December 2000: American Journal of Public Health, Canadian Journal of Public Health, Adolescence, Health Education and Behavior, Family Planning Perspectives, Journal of School Health, Youth and Society (1993 only), Journal of Early Adolescence (1993 only), Journal of Adolescent Research (1993-4 only), and Journal of Adolescent Health Care (1993-6 only). We included dissertations, conference proceedings, technical reports, and other unpublished documents that met our inclusion criteria. We reviewed the reference lists of all papers for relevant citations. When all the relevant studies had been identified, we sent the list to experts to review for completeness. Twenty six randomised controlled trials described in 22 reports met our inclusion criteria.18–39

Quality assessment of studies

We assessed the methodological quality of the studies using a modified version of the rating tool developed by Jadad et al.40 We rated the studies according to appropriateness of randomisation, extent of bias in data collection, proportion of study participants followed to the last point of follow up (adequate follow up included data on ⩾80% of the study participants at the last point of follow up), and similarity of attrition rates in the comparison groups (acceptable rates were within 2% of each other). We assigned 1 point for each (maximum of 4 points) and considered studies to be of poor quality if they scored ⩽2.

Data extraction

In addition to data on quality assessment, two individuals independently extracted data on setting, participants, unit of randomisation and analysis, theoretical framework guiding the intervention, intervention, outcome variables, length of follow up, proportion followed to study completion, and study findings at the last follow up by sex (if possible).

For each study we established the number of participants in the intervention and control groups who had and had not experienced the event (for instance, initiation of sexual intercourse after intervention, consistent use of birth control, and pregnancy after intervention) for the last follow up period. To define consistent use of birth control we assessed use at every intercourse or use at last intercourse. Pregnancy rates included any measure that assessed whether a young woman had conceived or given birth or whether a young man had impregnated a young woman or fathered a child.

In all cases two individuals assessed the studies and extracted data, with discrepancies resolved by joint review and consensus. We reviewed assessment of methodological quality and data extraction with the 16 authors who provided additional information when necessary.

Data analysis

Ten of the 22 studies randomised clusters such as classrooms, schools, agencies, or neighbourhoods rather than individuals. Optimal analysis of cluster randomised studies involves adjustment that relies on the correlation within clusters. We could access these correlations from only one study18 and therefore used these data as estimates for the correlation in all such studies and for each outcome. This correlation value, along with the number and size of clusters in each of the nine other studies, provided a method for estimating the appropriate variance inflation and thus the extent to which studies using cluster randomisation would receive less weight than studies using individual randomisation.

For each study we calculated the odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals. We pooled odds ratios using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model,41 tested for heterogeneity among studies using a χ2 procedure,42 and considered P<0.1 as an indication of heterogeneity. We performed analyses separately by sex, as sex differences may be missed when data are pooled.43

We tested 10 a priori hypotheses that might explain heterogeneity of study results: publication type (published and unpublished), control group intervention (alternate intervention and none), year of publication (before 1995 and 1995 or later), randomisation (appropriate and inappropriate), data collection (biased and unbiased), loss to follow up (⩾80% and <80%), difference in loss to follow up between groups (⩽2% and >2%), follow up period (⩾12 months and <12 months), baseline differences (none, favouring control, and favouring intervention), and type of intervention (school based sex education, multifaceted programme, family planning clinic, and abstinence programme).

Results

Trial characteristics

Table 1 gives details of the 22 reports of 26 randomised controlled trials that met our eligibility criteria. Of the 22 reports, 17 were published, four were unpublished dissertations, and one was an unpublished report.

Table 1.

Description of studies that evaluated strategies to prevent unplanned pregnancies in adolescents*

| Study | Setting | Sample size and characteristics | Unit of randomisation and analysis | Theoretical framework | Intervention | Length and success of follow up | Outcome | Baseline differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School/agency based sex education | ||||||||

| Aarons et al, 200019 | 6 junior high schools in Washington, DC | 582 grade 7 students, mean age 12.8 years, 52% female, 84% African-American, 13% Hispanic, low socioeconomic status | Randomisation: school. Analysis: individual | Social cognitive theory | 3 reproductive health classes taught by health professionals, 5 sessions of postponing sexual involvement curriculum taught by peer leaders in 10th and 11th grades; health risk assessment questionnaire. Control group: conventional programme | 3 months, 96.4% followed | Intercourse.† Use of birth control at last intercourse | Favour intervention |

| Coyle et al, 200123 | 20 urban high schools in Texas and California | 3869 grade 9 students, mean age 15 years, 53% female, 31% white, 27% Hispanic, 18% Asian or Pacific Islander, 16% African-American | Randomisation: school. Analysis: adjusted | Social learning theory. Social influence theory. Models of school change | Safer choices: 10 lessons for grade 9 and 10; lessons for grade 10 on knowledge and skills and led by trained peers and teachers, peer resource team, parent education, community linkages. Control group: standard knowledge based prevention curriculum | 31 months, 79% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control at last intercourse | Favour control |

| Eisen et al, 199025 | 6 family planning agencies and 1 school district in Texas and California | 1444 aged 13-19 (mean 15.5) years, low income, inner city youth, 52% female, 53% Hispanic, 24% African-American | Randomisation: 71% by classroom, 29% by individual. Analysis: individual | Health belief model. Social learning theory | Teen talk programme: 12-15 hours of discussion about facts, values, feelings, emotions, decision making, and sexual responsibility. Control group: usual sex education programmes which varied among sites | 12 months, 61.5% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control always and at last intercourse. Pregnancy | None |

| Ferguson 199826 | 4 local public housing developments or subsidised neighbourhoods in Virginia | 63 African-American females aged 12-16 (mean 13) years, 5th-10th grades, low income | Randomisation: neighbourhood. Analysis: individual | Social learning theory | 8 week programme (2h/week) led by trained peer counsellor on sex education, reproduction, birth control methods, life management skills, family relations, career options. Control group: same programme led by usual adult staff | 3 months, 83% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control at last intercourse. Pregnancy | Not reported |

| Handler 198728 (unpublished dissertation) | 2 public schools in Illinois | 63 African-American 7th grade females, mean age 13.3 years, most in female-headed households, over half on public assistance | Individual | Knowledge- access- empowerment | Peer power project: 1h/week during school year to increase knowledge, enhance decision making skills, improve self concept, set goals, increase interpersonal communication skills, link with supportive adult, visit clinics, establish career goals, participate in enrichment activities; facilitated by school counsellor and paid community aide. Control group: no intervention | 12 months, 84.1% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control at last intercourse. Pregnancy | Favour intervention |

| Kirby et al, 1997a32 | 6 schools in California | 2111 students, 7th grade, mean age 12.3 years, 54% female, 64% Hispanic, 13% Asian, 9% African-American, low socioeconomic status | Randomisation: classroom. Analysis: individual | Health belief model. Social learning theory | Project SNAPP: 8 sessions over 2 weeks led by trained peer educators on risks and consequences of teen sex, social influences, communication, resistance skills, susceptibility to pregnancy, barriers to remaining abstinent, birth control methods, community resources. Control group: standard curriculum | 17 months, 77% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control.† Pregnancy (young men and women combined) | None |

| Mitchell-DiCenso et al, 199718 | 21 schools in Ontario, Canada | 3289 students, 7th and 8th grade, mean age 12.6 years, 52% female, most white | Randomisation: school. Analysis: individual adjusted for clustering | Cognitive behavioural theory | McMaster teen programme: 10 sessions on problem solving, decision making, puberty, male/female roles, media and peer pressure, responsibility in relationships, intimacy, teenage pregnancy, parenting. Control group: standard curriculum | 4 years, 56% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control always. Pregnancy (young women only) | None |

| Moberg and Piper 199836 | 21 schools in Wisconsin | 2483 students, 6th grade, mean age 11 years, 52% female, 96% white | Randomisation: school. Analysis: individual adjusted for clustering | Social influence model | Group 1: age appropriate programme of 4 weeks each year over 3 years focused on social situations, refusal skills, parental values, media, communication, body image, responsibility, risks, birth control, sexuality. Group 2: intensive programmesame programme provided as 12 week block during grade 7. Control group: usual programme | 3 years, 80% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control always | None |

| Schinke et al, 198137 | Large public high school in Washington State | 36 students, 10th grade, mean age 15.9 years, 53% female | Individual | Cognitive behavioural theory | 14 small group sessions of 50 minutes on birth control, problem solving, practising communication of decisions about sexual behaviour through role playing. Control group: no programme | 6 months, 94% followed | Use of birth control† | None |

| Slade 198938 (unpublished dissertation) | High school in Washington, DC | 201 African-American 10th-12th grade female; 15-19 years, most living in female-headed households, low socioeconomic status | Individual | Perception based theory | Group 1: life outcome perceptions: 1 hour session focusing on negative impact of early childbearing, vocational goals, and life outcome. Group 2 : contraceptive education: 1 hour session focusing on types of birth control. Group 3: life outcomes and contraceptive education: 1 hour session combining negative impact of early childbearing and birth control methods. Control group: 1 hour session about current events | 2 months, 90% followed | Use of birth control always | Not reported |

| Abstinence programmes | ||||||||

| Anderson et al, 199921 | Community centres and schools in Los Angeles, California | 405 students, 5th-7th grade, mean age 10.6 years, 60% female, 46% Hispanic, 21% African- American | Randomisation: school and community centre. Analysis: individual | Cognitive behavioural theory | Reaching adolescents and parents programme:8 session programme designed to increase student knowledge about puberty and human reproduction, improve communication and decision making skills, facilitate family communication and delay onset of sexual activity; 6 sessions were for teens, 1 involved teens and parents, 1 for parents only. Control group: conventional programme | 12 months, 62% followed | Pregnancy (young women only) | None |

| Kirby et al, 1997b-e33‡ | 56 schools and 17 community based agencies in California | 10 600 students, 7th and 8th grade, mean age 12.8 years, 58% female, 38% white, 31% Hispanic, 9% African-American | Randomisation: school, agency, classroom, individual. Analysis: individual | Social influence theory | Postponing sexual involvement: 5 sessions, each 45-60 minutes delivered in classroom or small group settings focusing on risks of early sexual involvement, resistance to social and peer pressures, assertiveness skills, and non-sexual ways to express feelings. Control group: standard curriculum. Note: 4 RCTs are reported: random assignment by classrooms to adult-led intervention, by classrooms to youth-led intervention, by schools to adult-led intervention, and by individuals to adult-led intervention | 17 months, 75% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control.† Pregnancy | Favour control (adult led school based intervention only) |

| Miller et al, 199335 | Northern Utah | 548 families of 7th and 8th grade adolescents, 12-14 years, upper middle socioeconomic status, 95% white, 86% Mormon | Individual (families) | Not specified | Group 1: facts and feelings: 6 videotapes of 15-20 min focusing on puberty, sexual values, sexual anatomy, reproduction, prenatal development, birth, sexuality, advantages of postponing sexual intercourse, influence of media, consequences of sexual activity, decision making, assertiveness, refusal skills; parents received mailed newsletters. Group 2: same videotapes without mailed newsletters. Control group: no videotapes or newsletters | 12 months, 92% followed | Intercourse† | Not reported |

| Multifaceted programmes | ||||||||

| Allen et al, 199720 | 25 sites in US | 695 students, 9th-12th grade, mean age 15.8 years, 85% female, 67% African-American, 19% white, 11% Hispanic | Randomisation: student (>75% of sample) and classroom (<25% of sample). Analysis: individual | Helper therapy theory. Empowerment theory | Teen outreach programme: minimum of 20h/year of supervised community volunteer experience; classroom based discussions for 1h/week throughout academic year about service experiences, future life options, developmental tasks of adolescence, and sex, led by trained facilitators.Control group: regular curricular offerings | 9 months, 93% followed | Pregnancy (young women only) | Favour intervention |

| Grossman and Sipe 199227§ (unpublished report) | 5 cities in Massachusetts, California, Oregon, Washington State | 3226 economically and educationally disadvantaged, age 14-15 years, 51% female, 45% African-American, 18% Hispanic | Individual | Not specified | Summer training and education programme (STEP): work experience, basic skills remediation, life skills instruction over two summers; sexuality component focused on decision making and responsible sexual behaviour (90 hours of work, 90 hours of academic work, 5-15 hours of support during school years). Control group: summer jobs | 42 months, (1 RCT) 54 months (1 RCT) 80.9% followed | Intercourse.† Use of birth control.† Pregnancy† | None |

| McBride and Gienapp 200034 | 3 communities in Washington State | 690 high risk 14-17 (mean 15.4) year olds, 90% female, 26% non-white | Individual | Not specified | Client centred model: projects administered by combinations of family planning clinics, schools and other community based settings; various tailored services including education, skill building, counselling, mentoring, advocacy, values and attitudes about teen sexual activity and pregnancy, coping skills and goal setting, links to family planning services, participation in social or recreational activities; teens received average of 27 hours (most clients involved for 1-2 years). Control group: received 2-5 hours of service | 7 months, 75.7% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control always(all data for young women only) | None |

| Smith 199439 | Inner city high school in New York | 120 students 9th grade, mean age 15.1 years, 74% female, 43% African-American, 31% West Indian, 23% Hispanic | Individual | Operant theory | Teen incentive programme: 8 weekly sessions on self esteem, assertiveness, communication and decision making skills, academic performance, career planning, parent-teen relationships, substance abuse, peer and community influences, teen sexuality, pregnancy, STD, sexual responsibility; free condoms; 6 week career mentorship; 6 week life skills application sessions about sexual responsibility; monthly parental skills meetings for parents. Control group: written materials on contraception and decision making | 6 months, 79.2% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control† | None |

| Education and counselling in family planning clinics | ||||||||

| Baker 199022 (unpublished dissertation) | Family planning clinic in New Jersey | 62 sexually active 15-18 year old females, first time clinic attenders, 83% African-American, 17% Hispanic | Individual | Cognitive behavioural theory | Self efficacy training: one 5.5h session on facts, problem solving, modelling of verbal and non-verbal behaviour, role playing of problem solving and communication. Control group: usual care | 6 months, 77.4% followed | Oral contraceptive use always | Not reported |

| Danielson et al, 199024 | Health maintenance organisation serving Oregon and Washington states | 1195 males aged 15-18 years who had ambulatory care at participating medical offices, most white | Individual | None mentioned | 1 hour reproductive health intervention combining highly explicit half hour slide tape programme and personal health consultation designed to improve contraceptive practice, knowledge of fertility, prevention of STDs, practice of testicular self examination, amelioration of coercive sexual attitudes. Control group: no intervention | 12 months, 82% followed | Intercourse. Use of birth control at last intercourse | Not reported |

| Hanna 199029 (unpublished dissertation) | 2 family planning clinics in a rural state in upper midwest US | 51 females aged 16-18 years seeking oral contraceptives for first time; 98% white | Individual | King's theory of nurse-client interaction | Nurse-client transactional intervention to identify anticipated contraceptive benefits and barriers and to develop contraceptive adherence regimen. Control group: birth control information using written information and video | 3 months, 76.5% followed | Oral contraceptive use always | None |

| Herceg-Baron et al, 198630 | 9 family planning clinics in Pennsylvania | 417 female <16-17 years; 53% African- American | Individual | Not specified | Group 1: promotion of greater family involvement through 6 weekly 50 minute counselling sessions. Group 2: increased staff support through 2-6 telephone calls. Control group: regular services | 15 months, 85.9% followed | Use of birth control always. Pregnancy | Not reported |

| Jay et al, 198431 | Adolescent gynaecology clinic in Georgia | 57 females aged 14-19 years from lower socioeconomic status on oral contraceptives, 96.5% African-American | Individual | Not specified | Peer counselling on compliance with oral contraceptives. Control group: nurse counselling on compliance with oral contraceptives | 4 months, 66.7% followed | Oral contraceptive use.† Pregnancy | None |

Some data not found in papers but provided by authors.

Data unavailable in form required for inclusion in meta-analysis.

Four separate randomised controlled trials: 1997b—adult led, randomised by community; 1997c—adult led, randomised by classroom; 1997d—adult led, randomised by school; 1997e—youth led, randomised by classroom.

Two separate randomised trials.

Quality assessment of studies

Table 2 gives details of the assessment of quality. Only eight studies scored over 2 points of the possible 4. Only two studies scored the maximum 4 points.28,36

Table 2.

Quality assessment of randomised controlled trials of interventions aimed at preventing pregnancy in adolescents*

| Study | Appropriate randomisation | Unbiased data collection | Follow up ⩾80% | Difference in attrition between groups ⩽2% | Final score (out of 4)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarons, 200019 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Allen, 199720 | No | No | Yes | No | 1 |

| Anderson, 199921 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 |

| Baker, 199022 | No | No | No | No | 0 |

| Coyle, 200123 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| Danielson, 199024 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Eisen, 199025 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 |

| Ferguson, 199826 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 |

| Grossman, 199227 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Handler, 198728 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| Hanna, 199029 | No | No | No | No | 0 |

| Herceg-Baron, 198630 | NS | NS | Yes | No | 1 |

| Jay, 198431 | Yes | NS | No | No | 1 |

| Kirby, 1997a32 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| Kirby, 1997b-e33 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| McBride, 200034 | No | Yes | No | No | 1 |

| Miller, 199335 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 |

| Mitchell-DiCenso, 199718 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 |

| Moberg, 199836 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| Schinke, 198137 | NS | NS | Yes | NS | 1 |

| Slade, 198938 | No | Yes | Yes | NS | 2 |

| Smith, 199439 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 |

NS: not stated.

Some information provided by authors.

Scoring range: 0 (poor) to 4 (excellent).

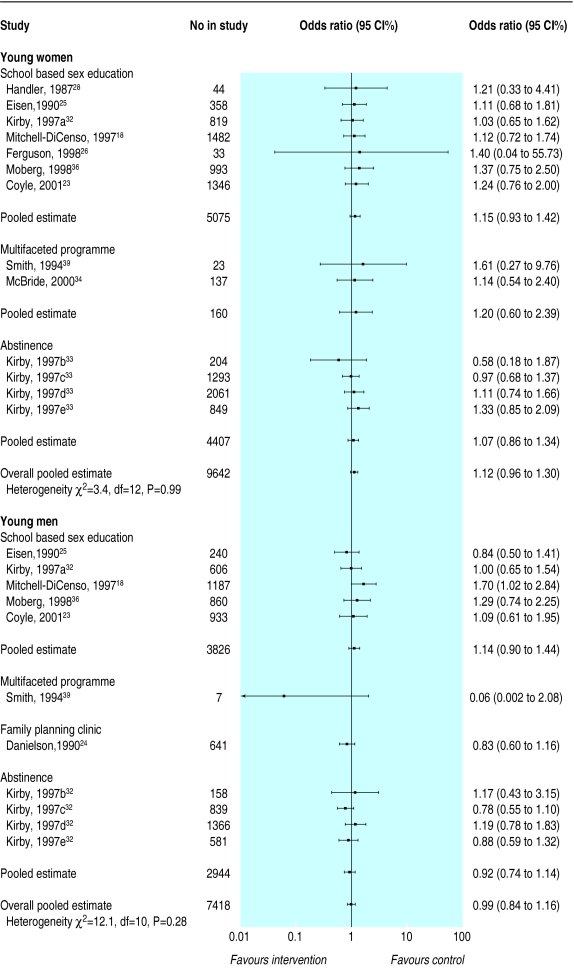

Initiation of sexual intercourse

Figure 1 shows the results of the meta-analysis on studies that looked at initiation of sexual intercourse. Thirteen studies in 9642 young women showed no delay in initiation of sexual intercourse (pooled odds ratio 1.12; 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 1.30). Results were consistent across studies (heterogeneity P=0.99). Results of 11 studies also showed no delay in initiation of sexual intercourse in 7418 young men (0.99; 0.84 to 1.16). There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (P=0.28).

Figure 1.

Effect of interventions on whether adolescents started to have sexual intercourse

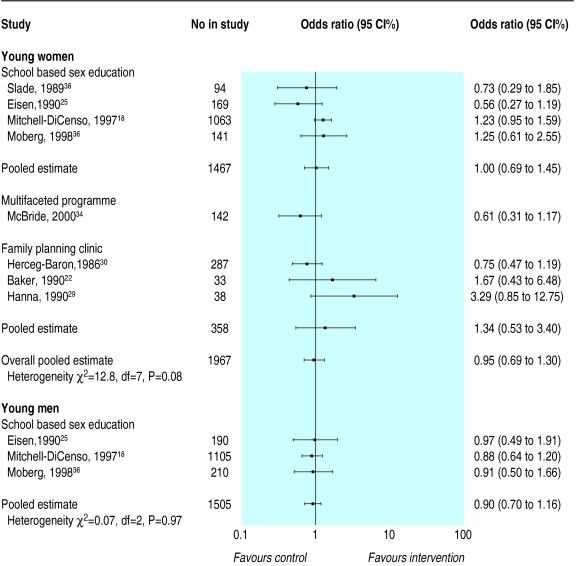

Use of birth control

Figure 2 shows the results for use of birth control at every intercourse. In 1967 eight studies of young women showed no improvement in use of birth control at every intercourse (0.95; 0.69 to 1.30). However, there was significant heterogeneity among studies (P=0.08) that was not explained by any of our 10 a priori hypotheses. Three studies of school based sex education in 1505 young men looked at whether they always used birth control. Results were remarkably consistent across studies (heterogeneity P=0.97) with a pooled estimate of 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16), indicating that the programmes did not improve use of birth control at every intercourse.

Figure 2.

Effect of interventions on whether adolescents always used birth control

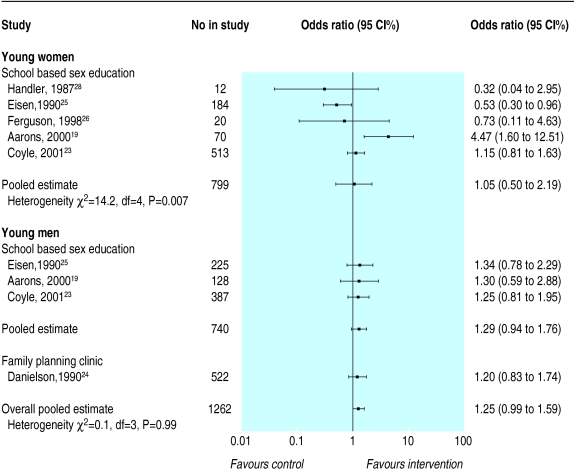

Figure 3 shows results for use of birth control at last intercourse. Five studies of school based sex education programmes in 799 young women showed no improvement (1.05; 0.50 to 2.19), with significant heterogeneity (P=0.007) that was not explained by any of our 10 a priori hypotheses. Aarons et al found a large treatment effect in favour of the intervention (4.47; 1.60 to 12.51).19 However, there were substantial baseline differences in this study that favoured the treatment group: 39% of the young women in the intervention group used birth control the last time they had intercourse compared with only 27% in the control group. More young women in the control group lived in a single parent family (32% v 22%) and more participated in the free lunch programme (69% v 53%), indicating lower socioeconomic status. When the authors controlled for age, academic grades, and free lunch programmes (but not for the other baseline differences) the odds ratio was 3.86 (1.10 to 13.47). In addition, data collection in this study was anonymous, which prevented any matching of before and after questionnaire data.

Figure 3.

Effect of interventions on whether adolescents used birth control the last time they had sexual intercourse

For use of birth control at last intercourse, four studies in 1262 young men had consistent results across studies (heterogeneity P=0.99), with a pooled estimate of 1.25 (0.99 to 1.59). The programmes therefore did not improve use of birth control by young men at last intercourse.

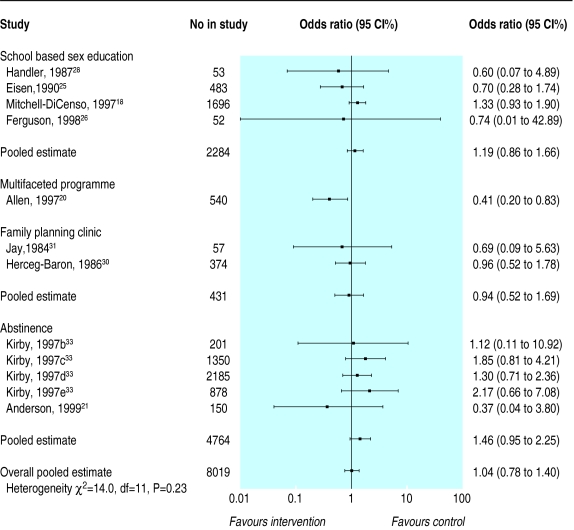

Pregnancy

Twelve studies in 8019 young women showed that the interventions did not reduce pregnancy rates (1.04; 0.78 to 1.40), and there was no significant heterogeneity among studies (P=0.23, fig 4). One study that evaluated a multifaceted programme did find a reduction (0.41; 0.20 to 0.83).20 At baseline, however, the control group had higher levels of previous course failure (P<0.04), school suspension (P<0.03), and teenage pregnancy (P<0.01). The authors excluded three of 25 sites where baseline differences were most problematic (these data were also excluded in our odds ratio calculation), adjusted for any remaining demographic differences, and still found a significant odds ratio of 0.41.

Figure 4.

Effect of interventions on rates of pregnancy in adolescent women

Figure 5 shows the effects of interventions on reducing pregnancies among the partners of 3759 young men. The pooled estimate of 1.54 (1.03 to 2.29) suggests that these interventions increased reported pregnancies. There was no significant heterogeneity among studies (P=0.58). Because Kirby et al did not report pregnancy data separately for young men and women we could not include their data in the meta-analyses. For the sexes combined they found no significant treatment effect (0.83, 0.34 to 2.01).32

Figure 5.

Effect of interventions on rates of pregnancy in partners of young men

Discussion

The results of our systematic review show that primary prevention strategies do not delay the initiation of sexual intercourse or improve use of birth control among young men and women. Meta-analyses showed no reduction in pregnancies among young women, but data from five studies, four of which evaluated abstinence programmes and one of which evaluated a school based sex education programme, show that interventions may increase pregnancies in partners of male participants.

Most of the participants in over half of the studies in our systematic review were African-American or Hispanic, thus over-representing lower socioeconomic groups. The interventions may be more successful in other populations. In all but five studies, participants in the control group received a conventional intervention rather than no intervention. It is possible that the control interventions had some effect on the outcomes and the tested interventions were not potent enough to exceed this effect. Finally, only eight of the 22 studies scored over 2 points out of the possible 4 points in the quality assessment. However, as poor methodological quality is more often associated with overestimates than underestimates of treatment effects it is unlikely that methodological weaknesses can explain the failure of the interventions to influence the outcomes measured.

Potential limitations

Although 10 of the 22 studies randomised clusters rather than individuals, we had data from only one of these studies18 to calculate correlations within clusters. We used these data as estimates for the correlation in all such studies to adjust for the cluster unit of randomisation. Secondly, despite testing 10 a priori hypotheses we were not able to explain the significant heterogeneity among studies that reported use of birth control in young women.

This review shows that we do not yet have a clear solution to the problem of high pregnancy rates among adolescents in countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Direction of future research

There is some evidence that prevention programmes may need to begin much earlier than they do. In a recent systematic review of eight trials of day care for disadvantaged children under 5 years of age, long term follow up showed lower pregnancy rates among adolescents.44 We need to investigate the social determinants of unintended pregnancy in adolescents through large longitudinal studies beginning early in life and use the results of the multivariate analyses to guide the design of prevention interventions. We should carefully examine countries with low pregnancy rates among adolescents. For example, the Netherlands has one of the lowest rates in the world (8.1 per 1000 young women aged 15 to 19 years), and Ketting and Visser have published an analysis of associated factors.45 In contrast, the rates are 93 per 1000 in the United States,46 62.6 per 1000 in England and Wales,47 and 42.7 per 1000 in Canada.48 We should examine effective programmes designed to prevent other high risk behaviours in adolescents. For example, Botvin et al found that school based programmes to prevent drug abuse during junior high school (ages 12-14 years) resulted in important and durable reductions in use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana if they taught a combination of social resistance skills and general life skills, were properly implemented, and included at least two years of booster sessions.49

Few sexual health interventions are designed with input from adolescents. Adolescents have suggested that sex education should be more positive with less emphasis on anatomy and scare tactics; it should focus on negotiation skills in sexual relationships and communication; and details of sexual health clinics should be advertised in areas that adolescents frequent (for example, school toilets, shopping centres).50 None of the interventions in this review focused on strategies for improving the quality of sexual relationships. Sexual exploitation, lack of mutual respect, and discomfort in voicing sexual needs and desires are common problems in adulthood. Interventions to help adolescents learn about healthy sexual relationships need to be designed and evaluations of these interventions that follow the adolescents into adulthood should be done.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elena Goldblatt for developing the search strategy and conducting searches of the electronic databases; Janet Yamada, Nalagini Nadarajah, and Sheila McNair for performing hand searches of key journals, retrieving articles, and sending data to authors for verification; and Maureen Dobbins who reviewed studies for methodological quality. We also thank Doug Kirby for sharing his expert knowledge and experience in reviewing this literature, the 16 authors who verified data extraction and provided further detail about their studies, Brian Hutchison for his thoughtful suggestions, and Susan Marks for careful review of the final manuscript. ADiC is a member of the Cochrane Fertility Regulation Review Group.

Footnotes

Funding: National Health Research Development Program, Health Canada; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; Region of Hamilton-Wentworth Social and Public Health Services PHRED Program: A Teaching Health Unit affiliated with McMaster University and the University of Guelph. ADiC is a career scientist of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.DiCenso A, Van Dover LJ. Prevention of adolescent pregnancy. In: Stewart MJ, editor. Community nursing: promoting Canadians' health. 2nd ed. Toronto, ON: W B Saunders; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SS, Eisenberg L, editors. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore KA, Myers DE, Morrison DR, Nord CW, Brown B, Edmonston B. Age at first childbirth and later poverty. J Res Adolesc. 1993;3:393–422. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0304_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geronimus AT, Korenman S. The socioeconomic consequences of teen childbearing reconsidered. Q J Economics. 1992;107:1187–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens-Simon C, White MM. Adolescent pregnancy. Pediatr Ann. 1991;20:322–331. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19910601-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonham GH, Clark M, O'Malley K, Nicholson A, Ready H, Smith L. In trouble...a way out: a report on pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases in Alberta teens. Alberta: Alberta Community Health System; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burt MR. Estimating the public costs of teenage childbearing. Fam Plann Perspect. 1986;18:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song EY, Pruitt BE, McNamara J, Colwell B. A meta-analysis examining effects of school sexuality education programs on adolescents' sexual knowledge, 1960-1997. J School Health. 2000;70:413–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby D, Coyle K. School-based programs to reduce sexual risk-taking behavior. Children and Youth Services Review. 1997;19:415–436. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visser AP, van Bilsen P. Effectiveness of sex education provided to adolescents. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;23:147–160. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Preventing and reducing the adverse effects of unintended teenage pregnancies. York: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oakley A, Fullerton D, Holland J, Arnold S, France-Dawson M, Kelly P, et al. Sexual health education interventions for young people: a methodological review. BMJ. 1995;310:158–162. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby D, Short L, Collins J, Rugg D, Kolbe L, Howard M, et al. School-based programs to reduce sexual risk behaviors: a review of effectiveness. Public Health Rep. 1994;109:339–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin C, Grant D, Corcoran J, Miller P, Bultman L. Effectiveness of prevention programs for adolescent pregnancy: a meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam. 1997;59:551–567. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Ryan G, Clifton J, Buckingham L, Willan A, et al. Should unpublished data be included in meta-analyses? Current convictions and controversies. JAMA. 1993;269:2749–2753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickersin K. The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. JAMA. 1990;263:1385–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt GH, DiCenso A, Farewell V, Willan A, Griffith L. Randomized trials versus observational studies in adolescent pregnancy prevention. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell-DiCenso A, Thomas BH, Devlin MC, Goldsmith CH, Willan A, Singer J, et al. Evaluation of an educational program to prevent adolescent pregnancy. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:300–312. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aarons SJ, Jenkins RR, Raine TR, El-Khorazaty MN, Woodward KM, Williams RL, et al. Postponing sexual intercourse among urban junior high school students—a randomized controlled evaluation. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:236–247. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen JP, Philliber S, Herrling S, Kuperminc GP. Preventing teen pregnancy and academic failure: experimental evaluation of a developmentally based approach. Child Dev. 1997;64:729–742. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson NLR, Koniak-Griffin D, Keenan CK, Uman G, Duggal BR, Casey C. Evaluating the outcomes of parent-child family life education. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1999;13:211–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker C. Self-efficacy training: its impact upon contraception and depression among a sample of urban adolescent females. New Jersey: Seton Hall University; 1990. (PhD thesis). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyle KK, Basen-Engquist KM, Kirby DB, Parcel GS, Banspach SW, Collins JL, et al. Safer choices: reducing teen pregnancy, HIV, and STDs. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(suppl 1):82–93. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danielson R, Marcy S, Plunkett A, Wiest W, Greenlick MR. Reproductive health counseling for young men: what does it do? Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisen M, Zellman GL, McAlister AL. Evaluating the impact of a theory-based sexuality and contraceptive education program. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22:261–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson SL. Peer counselling in a culturally specific adolescent pregnancy prevention program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:322–340. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grossman JB, Sipe CL. Summer training and education program (STEP): report on long-term impacts. Philadelphia, PA: Public/Private Ventures; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handler AS. An evaluation of a school-based adolescent pregnancy prevention program. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois at Chicago; 1987. (PhD thesis). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna KM. Effect of nurse-client transaction on female adolescents' contraceptive perceptions and adherence. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh; 1990. (PhD thesis). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herceg-Baron R, Furstenberg FF, Jr, Shea J, Harris KM. Supporting teenagers' use of contraceptives: a comparison of clinic services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1986;18:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jay MS, DuRant RH, Shoffitt T, Linder CW, Litt IF. Effect of peer counselors on adolescent compliance in use of oral contraceptives. Pediatrics. 1984;73:126–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirby D, Korpi M, Adivi C, Weissman J. An impact evaluation of project SNAPP: an AIDS and pregnancy prevention middle school program. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9(suppl 1):44–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirby D, Korpi M, Barth RP, Cagampang HH. The impact of the postponing sexual involvement curriculum among youths in California. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997;29:100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McBride D, Gienapp A. Using randomized designs to evaluate client-centered programs to prevent adolescent pregnancy. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32:227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller BC, Norton MC, Jenson GO, Lee TR, Christopherson C, King PK. Impact evaluation of facts and feelings: a home-based video sex education curriculum. Fam Relat. 1993;42:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moberg DP, Piper DL. The healthy for life project: sexual risk behavior outcomes. AIDS Educ Prev. 1998;10:128–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schinke SP, Blythe BJ, Gilchrist LD. Cognitive behavioral prevention of adolescent pregnancy. J Counseling Psychology. 1981;28:451–454. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slade LN. Life-outcome perceptions and adolescent contraceptive use. Atlanta, GA: Emory University; 1989. (PhD Thesis). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith MAB. Teen incentives program: evaluation of a health promotion model for adolescent pregnancy prevention. J Health Educ. 1994;25:24–29. doi: 10.1080/10556699.1994.10602996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clinical Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleiss JL. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1993;2:121–145. doi: 10.1177/096228029300200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamburg BA. Response: evaluation research. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1991;67:606–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zoritch B, Roberts I, Oakley A. Day care for preschool children. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2000;(2):CD000564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Ketting E, Visser AP. Contraception in the Netherlands: the low abortion rate explained. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;23:161–171. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alan Guttmacher Institute. United States pregnancy rates for teens, 15-19. www.teenpregnancy.org/resources/data/prates.asp (accessed 25 Mar 2002).

- 47.Office for National Statistics. Population trends. London: Stationery Office; 2000. www.statistics.gov.uk/themes/population/download/pt99book.pdf www.statistics.gov.uk/themes/population/download/pt99book.pdf (accessed 24 Mar 2002). (accessed 24 Mar 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Statistics Canada . Canada pregnancy rates for teens, 15-19. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Botvin GJ, Baker E, Dusenbury L, Botvin EM, Diaz T. Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middle-class population. JAMA. 1995;273:1106–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiCenso A, Borthwick VW, Busca CA, Creatura C, Holmes JA, Kalagian WF, et al. Completing the picture: adolescents talk about what's missing in sexual health services. Can J Public Health. 2001;92:35–38. doi: 10.1007/BF03404840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]