Abstract

The clinical diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) still depends on subjective information in terms of various symptoms regarding mood. Detecting the characterization of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in blood may result in finding a diagnostic biomarker that reflects the depressive stage of patients with MDD. Here, we report the results on the glycosylation pattern of enriched plasma EVs from patients with MDD. We compared glycosylation patterns by lectin blotting expressed in EVs isolated from the plasma of both patients with MDD and age-matched healthy control participants (HCs) using size-exclusion chromatography. The levels of Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc), and N-Acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac, sialic acid) - binding lectin, were significantly decreased in patients with MDD in the depressive state compared to HCs and in remission state. Furthermore, proteome analysis revealed that the von Willebrand factor (vWF) was a significant factor recognized by WGA. WGA-binding vWF antigen differentiated patients with MDD versus HCs and the same patients with MDD in a depressive versus remission state. In this study, the change patterns in the glycoproteins contained in plasma EVs support the usability of testing to identify patients who are at increased risk of depression during antidepressant treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-80507-x.

Keywords: Major depressive disorders, Extracellular vesicles, Glycans, Wheat germ agglutinin, Sialic acid, Von Willebrand factor

Subject terms: Biomarkers, Diseases

Introduction

Depression is a major mental health challenge globally and the leading cause of mental health-related disability worldwide1. Even among international consensus diagnostic criteria, such as the International Classification of Diseases 11th (ICD-11) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), diagnosing depression is based on a combination of symptoms. These diagnostic methods do not include objective laboratory findings2. Diagnosis and symptom evaluation of major depressive disorder (MDD) have depended on subjective information such as physicians’ clinical experiences and patient self-assessments, which can unfortunately lead to misdiagnosis3. Therefore, it is highly desirable to elucidate the pathophysiology of depression and discover diagnostic markers for depression that reflect the pathophysiology of depression to change this situation.

To identify biomarkers for MDD, proteomic analysis could explore the role of proteins in brain function, inflammation, neuroplasticity, and stress believed to be involved in the pathophysiology of MDD. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), are present at altered levels in patients with MDD, supporting the inflammatory hypothesis of depression4. The alteration of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which are involved in neuroplasticity, has also been observed in patients with MDD5,6. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is frequently dysregulated in MDD, and proteins related to the stress response and endocrine regulation are often altered in patients with depression. These proteins could help explain the chronic stress and mood disturbances typical of MDD7. However, further research is needed to validate these biomarkers in larger and more diverse populations, as well as to integrate them into clinical practice.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are microscale vesicles composed of lipid bilayers released by various cell types, containing proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and metabolites8. Since EVs are involved in intercellular signaling, as they are transported and function between host and recipient cells, EVs are valuable tools for studying cell-cell communication in biological processes9. These processes include cancer, autoimmune disease, and neurodegenerative disorder, leading to blood-based biomarkers for early diagnosis of disease10,11. EVs are involved in intercellular signaling, as they are transported and function between host and recipient cells9. Since EVs released from the central nervous system (CNS) can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), they can be detected peripherally, highlighting their potential for translation in mental disorders12. For a diagnosis of MDD, most preclinical studies focus on proteins and microRNAs in EVs related to metabolic pathways in CNS, neuro-inflammation, and neuroplasticity in the development of MDD13–15. However, since there is still no standardized extraction protocol to purify EVs from peripheral blood for a diagnosis of MDD, the abundance of EVs and key factors in EVs can make a significant difference in each experiment and across facilities.

Glycosylated proteins, lipids, neurotransmitters, and hormones have important roles in communicating with surrounding cells through the discrimination of their biomolecules16. These glycosylated molecules are promising disease biomarkers17–21. N-glycosylation plays a crucial role in several biological processes, especially those in the immune system. Since the onset and course of MDD are associated with alterations in the immune response, several reports have indicated that N-linked glycosylation is relevant to the diagnosis of the depressive state in women and the antidepressant treatment response in serum and plasma22,23. We also previously reported that glycan patterns determined by lectin array in plasma obtained from depression model mice and patients with MDD and that alterations in glycosylate structures could be a diagnostic marker24. EVs also have glycoproteins and glycolipids on their surface layer and inside, and this glycosylation pattern changes according to the condition depending on biological processes and diseases25. However, the importance of EV glycosylation in understanding depressive status remains largely unknown.

Therefore, this study investigated whether the glycosylation pattern of plasma EVs between patients with MDD in a depressive or remission state and healthy control participants (HCs) was different. Furthermore, we revealed the glycoprotein with characteristic glycans for patients with MDD to construct a novel detection system reflected in depressive status.

Materials and methods

Study participants

We carried out this study following the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Yamaguchi University Hospital approved this study (H25-085-13, H23-153-19, and H2022-203), and all subjects provided written informed consent for participation. We recruited patients with MDD and HCs as previously described24. Briefly, patients with MDD were recruited from Yamaguchi University Hospital or referred by clinics and hospitals in the area. All subjects were recruited between April 2012 and June 2013 and followed until August 2014. The mean age of the MDD group was 57.6 ± 6.0 years (n = 21), and the HCs group was 55.5 ± 7.6 years (n = 20) in recruited participants aged more than 18 and less than 80 years. We screened patients with MDD and diagnosed them using a structured clinical interview that included the International Neuropsychiatric Interview [M.I.N.I.], Japanese version 5.0.026. We defined depression by a score of 8 or higher on the Hamilton Rating for Depression Scale (HDRS)27. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) was used to assess social functioning28. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to exclude patients with possible dementia (score < 24)29. We classified patients in remission following the DSM-5 criteria for full remission. HCs were recruited using advertisements in the local community and screened using the MINI and a clinical interview. Any HCs with a family history of psychiatric disease were excluded from the study. The demographic data of patients with MDD and HCs included in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Baseline | After follow-up in MDD cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCs | MDD | p-value | MDD-DP | MDD-REM | p-value | |

| Sample size | 20 | 21 | 11 | 10 | ||

| Age (y) | 55.5 ± 7.6 | 57.6 ± 6.0 | 0.249 | 59.6 ± 5.6 | 56.5 ± 5.5 | 0.234 |

| Male/Female | 7/13 | 9/12 | 0.606 | 6/5 | 3/7 | 0.256 |

| Onset age (y) | – | 49.0 ± 12.7 | – | 53.0 ± 10.8 | 45.5 ± 13.4 | 0.200 |

| HDRS | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 23.8 ± 3.6 | 9.85e−27 | 22.4 ± 2.1 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 2.16e−10 |

| GAF | 92.0 ± 4.3 | 51.2 ± 6.7 | 6.64e−24 | 53.0 ± 5.7 | 86.5 ± 7.8 | 2.69e−9 |

|

Antidepressants (equivalent dose of imipramine) (mg) |

– | 220.1 ± 104.8 | – | 230.3 ± 100.7 | 209.3 ± 116.6 | 0.229 |

Demographic data of healthy control participants (HCs) and patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). After the follow-up period in the MDD cohort, we determined a diagnosis of permanent depressive (MDD-DP) or remission state (MDD-REM). Data is presented as mean (standard deviation) or the number of participants in each group. Independent-samples t-test was performed for age, onset age, HDRS, GAF and antidepressant dose. Pearson’s Chi-square test was performed for number of male or female.

Isolation of EVs from human plasma

We collected venous fasting blood from subjects between 9:00 and 12:00. Whole blood samples (< 10mL) were centrifuged at 2400×g for 5 min to separate plasma from peripheral blood cells. The plasma was apportioned into 1 ml aliquots, and stored at −80℃ until we used them.

We used qEV size exclusion columns (qEVoriginal-70 Gen2, Izon Science) in isolating EVs from human plasma to minimize contamination of lipoproteins30,31. 500 µL of processed plasma was directly overlaid onto the SEC qEV column, followed by filtered PBS. We collected 400 µL of the effluent into 1.5 microtubes by gravity flow until the column to empty. To estimate the protein concentration of each qEV fraction, we used the Micro BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To confirm the fractions of concentrated EVs, we did a western blot with antibodies against CD9 and CD63 as EV markers, or an antibody with cytochrome c for a cytoplasmic marker. We used the fractions with the highest concentration for the particle number and EV markers for lectin blotting, western blotting, and ELISA.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

We measured the size distribution and concentration of particles with Videodrop (Myriade, Paris, France). 7 µL of each EV fraction was used to measure the concentration and size of particles in each condition. The threshold was set at 4.2 for the removal of macro particles, and the exposure time was 0.90 ms for each frame. Accumulations were performed to count enough particles, with 100–300 particles counted for each condition.

Lectin blotting

Proteins from EVs extracts by Mem-PER Plus protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Lysates were loaded with 400 ng protein per lane to run SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were transferred to the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and incubated with the biotinylated Lectin Kit 1 (#BK-1000, Vector Laboratories, CA, USA), following Table S1. After washing, streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Proteintech Group Inc. IL, USA) at 1:5000 dilution was incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The membrane was developed by Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Cytiva, MA, USA) and examined using an Amersham Imager 680 (Cytiva). We used Fiji (ImageJ 1.53t) to analyze the intensity of bands.

Western blotting

Proteins in EVs were denatured with SDS sample buffer with DTT at 99 °C for 5 min (for reduced) or without DTT at 37 °C for 30 min (for non-reduced). Lysates were loaded with 400 ng protein per lane to run SDS-PAGE. We separated proteins by SDS-PAGE and transferred them to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with Block Ace (DS Pharma Biomedical, Osaka, Japan) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, which included anti-CD63 (3–13, 1:1000, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), anti-CD9 (12A12, 1:1000, Cosmo bio, Tokyo, Japan), anti-cytochrome c (1:1000, Proteintech, 10993-1-AP), anti-vWF (EPSISR15, 1:1000, abcam, MA, USA). After washing PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA) as secondary antibodies. Signals were developed using a detection reagent and examined using an Amersham Imager 680.

Deglycosylation enzyme treatment in vitro for plasma EVs

Plasma EVs (400 ng) of HCs were treated with α2–3,6,8 Neuraminidase (P0720, New England BioLabs, MA, USA) at least 50 units per sample at 37 °C for 1 h. The removal of glycans under this condition was confirmed by lectin blot or ELISA. The particle tracking analysis confirmed that most EVs maintained their vesicle structures after the enzymatic digestion.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

We equally mixed plasma EVs and a protein extraction reagent to isolate proteins from plasma EVs for ELISA. We assessed samples with VWF Human ELISA Kit (#EHVWF, Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

For constricting of the sandwich ELISA to quantify WGA-binding vWF, 96-well plates with the antibody against human vWF were treated with PNGase F (P0704, New England Biolabs) to remove N-linked glycan for 4 h at 37℃. After washing, plasma EVs were added to plates and incubated overnight at 4℃. Plates were incubated with WGA lectin (1:1000) at room temperature for 1 h, following diluted streptavidin-HRP room temperature for 45 min. We measured absorbance at 450 nm using a FlexStation 3 (Molecular Devices, Inc., CA, USA) within 30 min after adding the TMB Substrate.

Mass spectrometry and proteomic analysis

The EV lysates were dissolved by an equal amount of M-PER buffer and suspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with DTT. The samples were boiled at 99℃ for 5 min and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained using a Silver Stain KANTO III (Kanto Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan). After slicing the gel, sliced gels were incubated at 37˚C for trypsin digestion. Recovered peptides were desalted by Ziptip C18 (Merck Millipore, MA, USA). Samples were analyzed using a nanoLC/MS/MS system (DiNa HPLC system KYA TECH Corporation/QSTAR XL Applied Biosystems). Mass data acquisitions were piloted by Mascot search (MS/MS Ion Search).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Formvar/carbon-coated copper grid (Nisshin EM, Tokyo, Japan) was hydrophilized with JFC-1600 Auto Fine Coater (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). 3µL of purified EVs in PBS were placed on the hydrophilized grid and absorbed for 3 min. We washed them using 500 µL double-distilled H2O successive four drops, then negatively stained using 30 µL of 2.0% uranyl acetate successive four drops. The grid was air-dried after absorbing 2.0% uranyl acetate on the grid with filter paper. We imaged the grid with Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTWIN electron microscopy (FEI, OR, USA) operating 120 kV equipped with a EMSIS Phurona CMOS Camera. After exporting the raw data images to TIFF format, we used Fiji (ImageJ 1.53t) for data analysis.

Quantification and statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analysis and visualized data using R software (v4.3.1). We used Student’s t-test or Mann - Whitney U test to compare the differences between the two groups. We also used Bartlett’s test and one-way ANOVA for differences between the variances of the three groups. Graphs show mean ± standard division (SD). We used the pROC package (v1.18.5) in R software to estimate the prediction value for diagnosis. The area under the curve (AUC) of ROC was analyzed to judge the accuracy of the predictive model. We used the curve closest to the (0,1) to estimate the cut-off point.

Results

Characterization of plasma EVs from patients with MDD and HCs

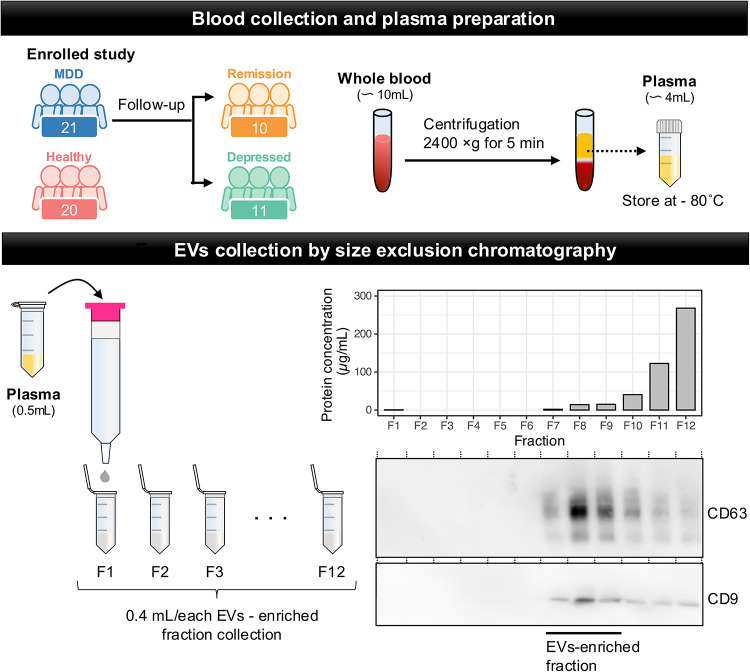

Participant demographic and clinical data acquired from the experiment are shown in Table 1. Differences in age, gender, HDRS, and GAF were nonsignificant among all groups. Differences in onset age and dose of antidepressants were also nonsignificant between depressive and remission states. We collected plasma EVs using qEV columns following a specific protocol (Fig. 1). EVs were purified from the plasma of HCs (n = 20) or patients with MDD (n = 21) through the size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). To collect the EVs enriched fraction, we performed a BCA protein assay to estimate protein concentration and western blotting with antibodies against CD63 and CD9 as EV-markers. Plasma proteins eluted later fractions (F10-12) than EVs (F7-9). Since both CD63 and CD9, specific EV markers, were detected using western blotting, we used fractions 7–9 in this experiment.

Fig. 1.

Overview of experimental framework for EVs enrichment and extraction by sizeexclusion chromatography. We purified EVs from the plasma of healthy control participants (HCs, n = 20) or patients with MDD (MDD, n = 21) by centrifugations, filtration, and passing through size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). The BCA protein assay and western blotting show a typical elution profile of plasma EVs obtained from a healthy control participant.

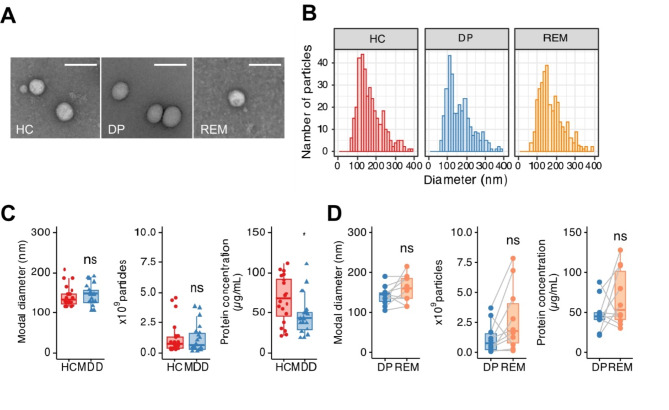

To evaluate the characterizations of plasma EVs in depressive states, we isolated the fraction containing EVs obtained from plasma from both patients with MDD and HCs by detecting the expression of the EV marker proteins, CD63 and CD9 (Fig. S1). The purified EVs were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which showed the morphology, as commonly seen between patients with MDD and HCs (Fig. 2A). Particle size distribution confirmed that the EVs from each sample population were in the range of 50–300 nm with peaks at around 150 nm (Fig. 2B). The modal particle size and the number of EV particles were similar among the EVs from HCs and those in patients with MDD (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, the amount of protein in plasma EVs from patients with MDD was significantly decreased in that of HCs. When we compared the modal particle size, the number of EV particles, and protein concentration between in depressive and remission states of the same patients, there was no statistically significant (Fig. 2D). These results indicated that protein contents in plasma EVs are possible to decrease or change during the progression of depression. The protein concentration of plasma EVs does not increase during remission; however, the functional protein composition may change due to factors such as antidepressant treatment.

Fig. 2.

Efficient separation of EVs in plasma obtained from HC, DP, and REM by size exclusion chromatography. (A) Representative photomicrographs of EVs isolated from plasma in HCs, DP, or REM imaged by CryoEM. Scale bar: 100 nm. (B) Representative particle size histogram of EVs in the enriched plasma fractions in HCs, DP, or REM by NTA. (C) Box plot of size, particle concentration, and protein concentration in plasma EVs after SEC. Each dot presents one sample. HCs; n = 20, MDD: n = 21. (D) Paired box plots depicting individual patient data between patients with MDD (n = 10) in DP and REM in size, particle concentration, and protein concentration. We used the Mann–Whitney U test or Student t-test to test for significance. *p < 0.05, n.s. Nonsignificant.

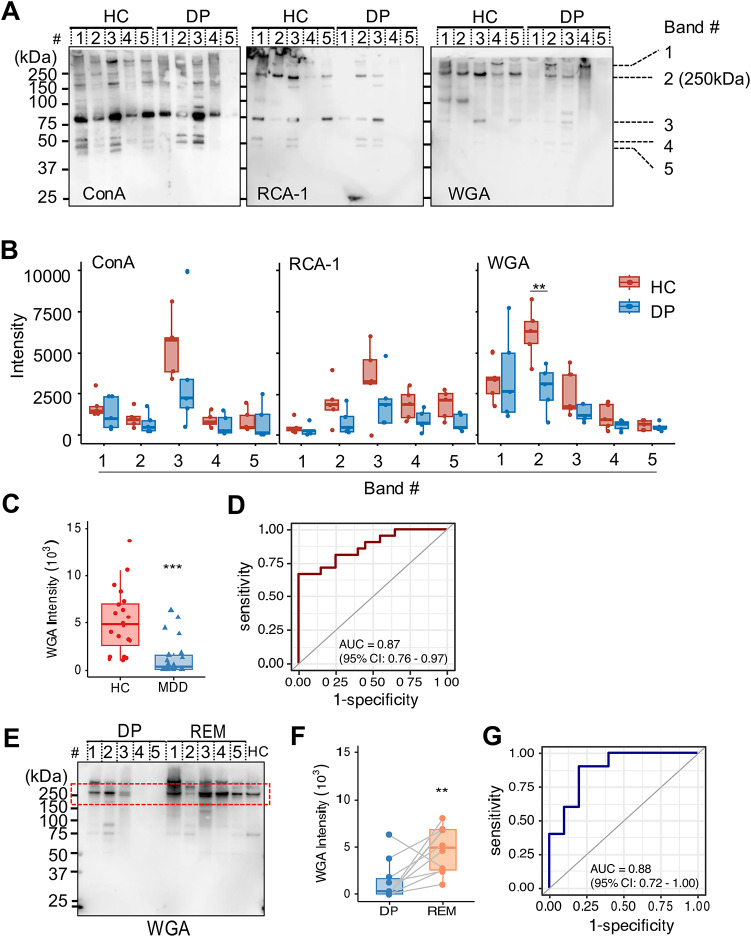

The extent of WGA-binding glycoprotein is reflected in the patients with MDD in a depressive state

To characterize EV glycosylation in patients with MDD in a depressive state, we recognized glycans by lectin blotting. We summarized the glycan structures specific to each lectin in Table S1. SDS-PAGE revealed a complex mixture of proteins detected in plasma EVs when we loaded the same amount of EV protein. Glycosylation patterns among Ulex europaeus agglutinin 1 (UEA-1), Arachis hypogaea agglutinin (PNA), Soybean Agglutinin (SBA), and Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) were rarely detected in both patients with MDD and HCs (Fig. S2). On the other hand, glycosylation patterns were detected with lectins recognized by Concanavalin A (ConA), Ricinus communis agglutinin (RCA120), and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (Fig. 3A). To compare the band intensity of ConA, RCA120, and WGA between the two groups, we selected five identifiable visible bands from around 37 to over 250 kDa (Band #1–5). The amount of glycosylated protein with a molecular weight above 250 kDa (Band #2) recognized by WGA significantly decreased in plasma EVs from patients with MDD compared with HCs (Fig. 3B, the densitometric intensity of HC, 6221.34 ± 1422.17 and DP, 2833.87 ± 1254.72; p = 0.00727). Moreover, to validate the discovery results, we compared all participants in patients with MDD (n = 21) and HCs (n = 20). The intensity of WGA was significantly lower in the patient with MDD than in the HCs (Fig. 3C, densitometric intensity of HCs, 5162.67 ± 3360.85 and DP, 1338.97 ± 1898.61; p = 0.00008). When we constructed a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) curve of the relative intensity of WGA between patients with MDD in a depressive state and HCs, ROC analysis yielded an AUC of 0.87 (95% CI 0.76–0.97) (Fig. 3D), thus indicating the predictive power of plasma EVs with glycans in patients with MDD.

Fig. 3.

WGA lectin detects changes in the glycosylation status in plasma EVs in patients with MDD and HCs. (A) Glycan profiling of plasma EVs of healthy control participants (HCs) and patients with MDD in a depressive state (DP) by lectin blotting. Lectins used for detections: ConA, RCA120, and WGA. We loaded the same amount of protein concentration (400 ng/lane). The band number indicates visible bands to measure the intensity (#1–5). (B) We analyzed relative intensity in arbitrary units by Image J in (A). The number of independent: HC; n = 5, DP; n = 5. (C) The boxplots represent the signal intensity of protein bands in arbitrary units. (D) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis using the intensity of WGA lectin in plasma EVs to diagnose between HCs and DP. A cutoff value is 2450 by the closest-top-left method. (E) Lectin blotting profiles detected by WGA in plasma EVs from patients with MDD in DP and remission state (REM). We used plasma EVs by HCs as a positive control. The red line indicates bands at approximately 250 kDa. (F) Paired box plots depicting individual patient data between DP (n = 10) and REM. (G) ROC curve analysis of the intensity of WGA as a biomarker of DP compared with REM. A cutoff value is 2130 by the closest-top-left method. We used the Mann–Whitney U test or Student t-test to test for significance. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Next, to assess the diagnosis of a depressive state, we compared the amount of WGA-binding protein with a molecular weight above 250 kD in plasma EVs between depressive and remission state of the same patients with MDD (n = 10) by lectin blotting (Fig. 3E). The intensity of the protein band at a molecular weight above 250 kDa in plasma EVs from depressive state individuals detected by WGA was significantly lower than that from EVs from those that had recovered to remission state (Fig. 3F, densitometric intensity of DP, 1390.40 ± 1993.23 and REM, 4723.40 ± 2277.96; p = 0.0040). In addition, the ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.88 (95% CI 0.72–1.00) for plasma EVs, which distinguished each status (Fig. 3G). We previously reported the results of a lectin array using leukocytes obtained from the human peripheral blood of patients with MDD and HCs24. Among them, there were no differences between the patients with MDD and HCs determined by different sialic acid binding lectins, including ConA, RCA120, and WGA (Fig. S3). These data show that a decrease in glycoproteins recognized by WGA in plasma EV could indicate the status of depressive symptoms, which have the potential for diagnosis of depression.

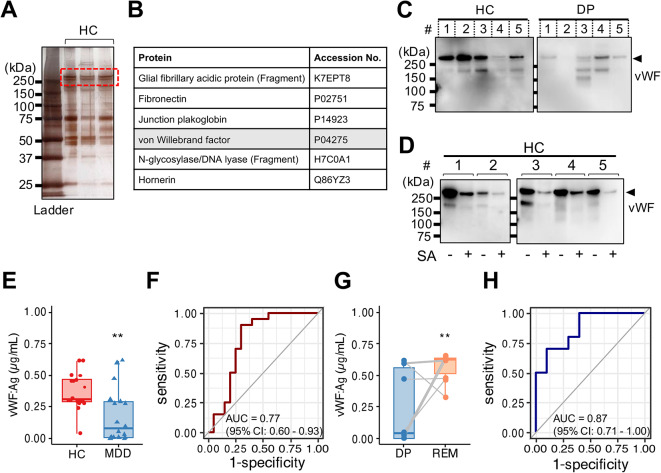

Proteome analysis reveals that vWF is selectively contained in plasma EVs

The lectin of WGA can bind to oligosaccharides containing terminal N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac, also known as sialic acid). To search for proteins that could link N-linked carbohydrate chains containing terminal GlcNAc and sialic acid, we first performed silver staining on samples from HCs (Fig. 4A). We next analyzed the identified proteins by mass spectrometry. Among them, one of the most significant hits was the von Willebrand factor (vWF) (Fig. 4B, Fig. S4, Table S2). vWF is a glycoprotein implicated in the maintenance of hemostasis at the sites of vascular injury by forming a molecular bridge between the subendothelial matrix and platelet-surface receptor complex32. We confirmed that the vWF proteins, detected by western blotting, had a molecular weight above 250 kDa in plasma EVs from HCs and patients with MDD (Fig. 4C). Human vWF is capped by terminal negatively charged sialic acid residues33. After sialidase digestion in vitro, the levels of the vWF protein decreased and shifted to a molecular weight of less than 250 kDa (Fig. 4D). Thus, our data suggested that plasma EVs contained vWF expressing terminal sialic acid.

Fig. 4.

Proteome analysis revealed that vWF in plasma EVs related to the stage of MDD. (A) SDS-PAGE gel with silver staining. The gels contain protein standard (lane 1) and healthy control participants (HCs) (lane 2–4). Coverage of above 250 kDa protein (red dashed line) in plasma EV obtained HCs analyzed by LC-MS. (B) List of polypeptides within above 250 kDa protein identified in the proteomics analysis. (C) Representative image of western blotting for vWF protein (Molecular weight, 260 kDa) in plasma EVs (400 ng) obtained from HCs (n = 5) and patients with MDD (MDD, n = 5). (D) Representative image of western blotting for plasma EVs proteins (400 ng) in HCs (n = 5) with or without sialidase (SA) treatment. We detected the PVDF membrane strips with an antibody against human vWF. (E) Densitometric measurement of vWF antigen (Ag) in plasma EVs from HCs (n = 20) and patients with MDD (n = 21) by sandwich ELISA. The absorbance read at 450 nm. (F) ROC curve analysis using vWF Ag in plasma EVs for diagnosis of MDD. A cutoff value is 0.276 µg/mL by the closest-top-left method. (G) Paired box plots depicting individual patient data between patients with MDD (n = 10) in depressive state (DP) and remission state (REM). (H) ROC curve analysis using vWF Ag in plasma EVs for diagnosis of MDD. A cutoff value is 0.606 µg/mL by the closest-top-left method. We used Mann–Whitney U test or Student t-test to test for significance. **p < 0.01.

To assess the expression of vWF protein in patients with MDD and HCs, we performed sandwich ELISA on the vWF protein from the same amount of plasma EVs in each sample. vWF protein expression was significantly lower in plasma EVs from patients with MDD in depressive state (mean concentration 0.187 ± 0.220 µg/mL, n = 21) than in those from HCs (mean concentration 0.376 ± 0.143 µg/mL, n = 20) (Fig. 44). ROC analysis of plasma EVs from patients with MDD in depressive state and HCs yielded an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI 0.60–0.93) (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, the concentration of vWF protein in plasma EVs recovered during remission status (mean concentration 0.572 ± 0.104 µg/mL, n = 10) (Fig. 44G). In validation, vWF protein in the depressive state was distinguished from remission status by ROC (AUC of 0.87 (95% CI 0.71–1.00)) (Fig. 4H). Hence, these results indicate that vWF-containing plasma EVs strongly correlated with the patients with MDD in a depressive state.

vWF is abundantly present in the circulation as a dimeric or multimeric form to respond immediately to traumatic injury30. The amount of released vWF to plasma was no significant difference between patients with MDD (3.998 ± 0.336 µg/mL, n = 21) and HCs (4.072 ± 0.267 µg/mL, n = 20) (Fig. S4). We could confirm that the amount of vWF on plasma EVs was altered in patients with MDD compared to HCs, which did not depend on the amount of vWF in plasma.

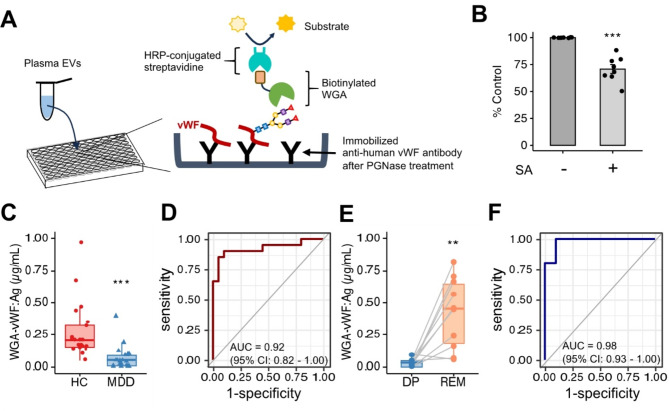

The expression levels of WGA-vWF strongly correlate with the treatment state in patients with MDD

To determine if plasma EVs containing WGA-binding vWF (WGA-vWF) could be applied as a diagnostic marker for MDD in the clinic, we designed a sandwich ELISA system to detect both WGA and vWF antigen in plasma EVs (Fig. 5A). The anti-vWF antibody without N-linked carbohydrate using PNGase F was immobilized on a 96-well plate. Plasma EVs were captured and detected with biotinylated WGA. The constructed standard curve exhibited concentration-dependent linearity (Fig. S6). When we also measured the absorbance of WGA-binding vWF after sialidase treatment, the absorbance was decreased compared with no treatment (Fig. 5B). Hence, the ELISA we developed was acceptable for detecting both WGA and vWF in plasma EVs.

Fig. 5.

The levels of vWF Ag recognized by WGA in plasma EVs strongly correlate with the depressive state. (A) The schema of lectin-antibody sandwich ELISA for quantification of WGA-vWF protein. Bound vWF antibodies after PNGase treatment were detected using HRP-conjugated WGA. The absorbance read at 450 nm. (B) Normalized absorbance of WGA-vWF antigen (Ag) in plasma EVs (1 µg protein each sample) in HCs (n = 8) with or without SA treatment by the lectin-antibody sandwich ELISA. The level of vWF recognized by WGA showed significant changes due to the desialylation of vWF. (C) Quantification of WGA-vWF: Ag in plasma EVs by ELISA between patients with MDD (n = 21) and healthy control participants (HCs, n = 20). We use the same concentration of protein (400 ng per well) for each sample. (D) ROC curve analysis of the concentration of WGA-vWF: Ag in plasma EVs for diagnosis of MDD. The cutoff value is 0.129 µg/mL by the closest-top-left method. (E) Paired box plots depicting individual patient data of WGA-vWF: Ag in plasma EVs between patients with MDD (n = 10) in depressive state (DP) and remission state (REM). (F) ROC curve analysis of WGA-vWF: Ag in plasma EVs between DP and REM in the same patients with MDD. A cutoff value is 0.053 µg/mL by the closest-top-left method. We used Mann–Whitney U test or Student t-test to test for significance. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

When we considered whether ELISA-detected WGA-vWF in plasma EVs can help diagnose depression, WGA-vWF expression was significantly lower in plasma EVs of patients with MDD in a depressive state (mean concentration 0.068 ± 0.104 µg/ml, n = 21) than those of HCs (mean concentration 0.274 ± 0.212 µg/ml, n = 20) (Fig. 55). ROC analysis indicated that the AUC value for the diagnosis was 0.92 (95% CI 0.82–1.00) between patients with MDD and HCs (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, WGA-vWF expression remarkably increased from depressive (mean concentration 0.030 ± 0.029 µg/ml) to remission processes (mean concentration 0.419 ± 0.260 µg/ml) (Fig. 5E). We also could distinguish between patients with MDD in depressive and remission states (AUC of 0.98, 95% CI 0.93–1.00) (Fig. 5F). This ELISA combines WGA and vWF is more specific method than ELISA using the vWF antibody alone. We also evaluated the relationship of WGA-vWF levels in plasma EVs obtained from patients with MDD and HCs with gender or age. The results confirmed that there was a significant difference in the expression of WGA-vWF in plasma EVs in females (HC, n = 13: DP, n = 12: p = 3.1e-05) and males (HC, n = 7: DP, n = 9: p = 0.0045) (Fig. S7A). On the other hand, age was not linearly correlated with the vWF-WGA levels; the correlation coefficient was − 0.11 in HCs and − 0.096 in patients with MDD, respectively (Fig. S7B). Our findings suggested that WGA-vWF is a potential biomarker candidate for the diagnosis of patients with MDD in a depressive state regardless of gender and age.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the glycans on circulating EVs as potential signatures in patients with MDD and HCs by lectin blotting. We found that the levels of WGA could distinguish not only between patients with MDD and HCs but between patients with MDD in a depressive state and remission. Additionally, we show that vWF containing sialic acid from circulating EVs in peripheral blood is significantly decreased in patients with MDD. To our knowledge, this is the first report on a biomarker candidate using EVs containing a glycoprotein that reflects the state of patients with MDD.

vWF is a large multidomain protein consisting of type A and D domains that can interact with multiple proteins34,35. vWF is mainly produced in endothelial cells and megakaryocytes, which are present in blood plasma36. vWF plays an important role in blocking blood vessels from binding to platelets via platelet receptors and aggregates after vascular injury37–39. Multimer vWF builds in the Golgi complex and is stored within the Weibel-Palade body (WPB), similar to storage granules after being transported within lipid bilayers40. vWF colocalizes with CD63, one of the specific EV markers, in the WPB of endothelial cells and is often associated with internal vesicles41. Accordingly, vWF may exist on EV surfaces, except for an adhesive surface or WPB on activated endothelial cells. Another group reported that vWF in plasma EVs obtained from patients with glioblastoma is a biomarker that might assist in diagnosing and managing glioblastoma42.

It is essential to determine whether vWF expression is the cause or origin of MDD symptoms in patients with MDD. Chronic stress leads to a tightly controlled process that involves a wide array of neuronal and endocrine systems43. Depressed patients have hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and high levels of glucocorticoids (GCs), which are secreted from the adrenal glands. The feedback to the brain, damages the portions of the brain environment, such as the hippocampus, resulting in a depressed mood44. GCs bind to the promoter region of vWF and promote vWF expression, indicating a positive correlation between GC and vWF expression in Cushing syndrome patients45. Therefore, since vWF expression in plasma EVs significantly decreased in patients with MDD in a depressive state, vWF does not appear to be downstream of the HPA system. Inflammation can also alter the brain signaling system through the CNS46. Inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL1β), and interleukin-6 (IL6), are secreted by microglia, which control the immune system in the brain46–48 and activate serotonin transporters49. Depressed patients have high expression levels of stress-induced inflammatory cytokines50. Multimer vWF secretion is high during inflammation associated with thrombus formation after vascular injury51, but vWF expression in vascular endothelial cells is decreased by TNF-α treatment in vitro52. Therefore, vWF expression in vascular endothelial cells may be downregulated by a stress response through an inflammatory pathway, leading to EV secretion with low levels of vWF from vascular endothelial cells to blood.

vWF monomers contain complex N-glycan and O-glycan structures33. Glycan determinants play critical roles in regulating multiple aspects of vWF biology. Importantly, the vWF synthesized in endothelial cells is fully sialylated, whereas platelet-derived vWF has been shown to have significantly reduced vWF N-linked sialylation, which regulates proteolysis by ADAMTS1353. Loss of sialic acid from glycans in the extremity in vWF terminates with Gal or GalNAc residues. Gal residues trigger enhanced vWF clearance through several different pathways, including the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR; also known as Ashwell-Morell receptor) on hepatocytes or macrophage galactose lectin receptor (MGL) on macrophages54. Thus, stabilizing vWF in blood to cover terminal sialic acid residues is important, leading to blood vessel formation, homeostasis, and repair after injury.

Finally, our study is limited because MDD is a clinically heterogeneous phenotype and has not been compared to other mental disorders, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. A comprehensive differential diagnosis of MDD is necessary for the clinical follow-up to distinguish the disorder from other mental conditions. Interestingly, the expression level of vWF in human plasma significantly increased in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia compared to HCs, with no differences between the two diagnostic groups55. Endothelial hyperactivation is inferred to be an essential mechanism for the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. We showed that the low levels of vWF in plasma EVs in patients with MDD in the depressive state have the potential for different characteristics from other mental disorders, leading to a rigorous tool for the clinical diagnosis of MDD. The EVs in blood we found will contribute to the comprehensive diagnosis of MDD in addition to the psychological tests and the diagnostic imaging. However, our findings need to be validated by a future study including a larger number of patients.

Conclusion

This study screened the glycosylation patterns and glycoproteins expressed in plasma EVs from patients with MDD, and we identified sialylated vWF. This finding reveals not only a novel biomarker candidate for MDD status but also original insight into the pathogenesis of MDD caused by endothelial dysfunction, which may provide novel approaches for MDD treatment. More studies should focus on expanding sample sizes and distinguishing other psychiatric disorders to validate the specificity of vWF in plasma EVs as a biomarker for MDD. It is also necessary to assess how antidepressant treatments impact sialylated vWF in plasma EVs by longitudinal studies and evaluate whether EV-associated biomarkers correlate with clinical outcomes. However, our findings, taken together, will be helpful as a diagnostic tool to assist with neuroimaging and clinical data in patients with MDD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their generously volunteered time. We thank Drs. T. Matsubara, F. Higuchi, K. Harada, and M. Kobayashi for support with clinical protocol, patient care, or collection and provision of patient samples. We thank the Yamaguchi University Center for Gene Research for assistance with nanoparticle tracking analysis and transmission electron microscopy.

Author contributions

N.Y., K.T., N.T. and S.N. conceived and designed the study. N.Y., K.T., C.N. and A.K performed experiments. N.Y. and K.T. did the data analysis and interpretation. N.Y., Y.M. and S.N. provided theclinical data and selected samples in this study. A.K. and S.N. did blood sample collection. Y.M. didtransmission electron microscopy analysis. H.Y. did initial assay development and provided the lectinarray data of human plasma. N.T. provided the technic and the knowledge in EV analyzing. N.Y., K.T., N.T. and S.N. wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures. All authors reviewed and edited the paper.

Data availability

All data in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files) are available. The other data analyzed in the current study are not publicly available for ethical reasons. A previous version of this article was published as a preprint on medRxiv: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.24.24304794.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Herrman, H. et al. Reducing the global burden of depression: a Lancet–World Psychiatric Association Commission. TheLancet393, e42–e43 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Malhi, G. S. & Mann, J. J. Depression. The Lancet392, 2299–2312 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mitchell, A. J., Vaze, A. & Rao, S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. The Lancet 374, 609–619 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Osimo, E. F. et al. Inflammatory markers in depression: A meta-analysis of mean differences and variability in 5,166 patients and 5,083 controls. Brain Behav. Immun.87, 901–909 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cavaleri, D. et al. The role of BDNF in major depressive disorder, related clinical features, and antidepressant treatment: Insight from meta-analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 149, 105159 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Tseng, P. T., Cheng, Y. S., Chen, Y. W., Wu, C. K. & Lin, P. Y. Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.25, 1622–1630 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunugi, H., Hori, H. & Ogawa, S. Biochemical markers subtyping major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Clin.Neurosci. 69, 597–608 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Tominaga, N. Anti-cancer role and therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles. Cancers(Basel)13, 6303 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Xu, R., Greening, D. W., Zhu, H. J., Takahashi, N. & Simpson, R. J. Extracellular vesicle isolation and characterization: Toward clinical application. J. Clin. Investig.126, 1152–1162 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Wu, W. C., Song, S. J., Zhang, Y. & Li, X. Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Autoimmune Pathogenesis. Front. Immunol.11, 579043 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Delpech, J. C., Herron, S., Botros, M. B. & Ikezu, T. Neuroimmune Crosstalk through Extracellular Vesicles in Health and Disease. Trends Neurosci. 42, 361–372 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Saeedi, S., Israel, S., Nagy, C. & Turecki, G. The emerging role of exosomes in mental disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 122 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Li, L. et al. Abnormal expression profile of plasma-derived exosomal microRNAs in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Hum. Genom.15, 55 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Gelle, T. et al. BDNF and pro-BDNF in serum and exosomes in major depression: evolution after antidepressant treatment. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry109, 110229 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hung, Y. Y. et al. Exosomal let-7e, mir-21-5p, mir-145, mir-146a, and mir-155 in predicting antidepressants response in patients with major depressive disorder. Biomedicines9, 1428 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Ohtsubo, K. & Marth, J. D. Glycosylation in Cellular Mechanisms of Health and Disease. Cell, 126, 855–867 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kronimus, Y. et al. Fc N-glycosylation of autoreactive Aβ antibodies as a blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement.19, 5563–5572 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pradeep, P., Kang, H. & Lee, B. Glycosylation and behavioral symptoms in neurological disorders. Transl. Psychiatry. 13, 154. (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paton, B., Suarez, M., Herrero, P. & Canela, N. Glycosylation biomarkers associated with age-related diseases and current methods for glycan analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 5788 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Chandler, K. & Goldman, R. Glycoprotein disease markers and single protein-omics. Mol. Cell. Proteom.12, 836–845 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Costa, J., Hayes, C. & Lisacek, F. Protein glycosylation and glycoinformatics for novel biomarker discovery in neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev.89, 101991 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Boeck, C. et al. Alterations of the serum N-glycan profile in female patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 234, 139–147 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park, D. I. et al. Blood plasma/IgG N-glycome biosignatures associated with major depressive disorder symptom severity and the antidepressant response. Sci. Rep.8, 179 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Yamagata, H. et al. Altered plasma protein glycosylation in a mouse model of depression and in patients with major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 233, 79–85 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishida-Aoki, N., Tominaga, N., Kosaka, N. & Ochiya, T. Altered biodistribution of deglycosylated extracellular vesicles through enhanced cellular uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles9, 1713527 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Otsubo, T. et al. Reliability and validity of Japanese version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci.59, 517–526 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.HAMILTON, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 23, 56–62 (1960). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moos, R. H., McCoy, L. & Moos, B. S. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) ratings: determinants and role as predictors of one-year treatment outcomes. J. Clin. Psychol.56, 449–461 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & Mchugh, P. R. ‘Mini-mental state’ A practical method for Grading the cognitive state of patients for the Cinician. J. Psychiatr. Res.12, 189–198 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Pang, B. et al. Quality assessment and comparison of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles separated by three commercial kits for prostate cancer diagnosis. Int. J. Nanomed.15, 10241–10256 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stranska, R. et al. Comparison of membrane affinity-based method with size-exclusion chromatography for isolation of exosome-like vesicles from human plasma. J. Transl. Med.16, 1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Peyvandi, F., Garagiola, I. & Baronciani, L. Role of von Willebrand factor in the haemostasis. Blood Transfus.9, s3–s8 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Ward, S., O’Sullivan, J. M. & O’Donnell, J. S. von Willebrand factor sialylation—A critical regulator of biological function. J. Thromb. Haemost.17, 1018–1029 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Gogia, S. & Neelamegham, S. Role of fluid shear stress in regulating VWF structure, function and related blood disorders. Biorheology52, 319–335 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Denorme, F., Vanhoorelbeke, K. & De Meyer, S. F. von Willebrand Factor and Platelet Glycoprotein Ib: A Thromboinflammatory Axis in Stroke. Front. Immunol.10, 2884 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Leebeek, F. W. G. & Eikenboom, J. C. J. Von Willebrand’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med.375, 2067–2080 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bockenstedt, P., Greenberg, J. M. & Handin, R. I. Structural basis of Von Willebrand factor binding to platelet glycoprotein ib and collagen. Effects of disulfide reduction and limited proteolysis of polymeric von Willebrand factor. J. Clin. Invest.77, 743–749 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ju, L. et al. Von Willebrand factor-A1 domain binds platelet glycoprotein Ibα in multiple states with distinctive force-dependent dissociation kinetics. Thromb. Res.136, 606–612 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonazza, K. et al. Von Willebrand factor A1 domain stability and affinity for GPIbα are differentially regulated by its O-glycosylated N-and C-linker. Elife11, e75760 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Valentijn, K. M., Valentijn, J. A., Jansen, K. A. & Koster, A. J. A new look at Weibel-Palade body structure in endothelial cells using electron tomography. J. Struct. Biol.161, 447–458 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Streetley, J. et al. Stimulated Release of Intraluminal Vesicles from Weibel-Palade Bodies. Blood133, 2707–2717 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Sabbagh, Q. et al. The Von Willebrand factor stamps plasmatic extracellular vesicles from glioblastoma patients. Sci. Rep.11, 22792 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Smith, S. M. & Vale, W. W. The Role of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Neuroendocrine Responses to Stress. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci.8, 383–395 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ignácio, Z. M., da Silva, R. S., Plissari, M. E., Quevedo, J. & Réus, G. Z. Physical Exercise and Neuroinflammation in Major Depressive Disorder. Mol. Neurobiol.56, 8323–8335 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Casonato, A. et al. Polymorphisms in Von Willebrand factor gene promoter influence the glucocorticoid-induced increase in Von Willebrand factor: the lesson learned from Cushing syndrome. Br. J. Haematol.140, 230–235 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinmetz, C. C. & Turrigiano, G. G. Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling maintains the ability of cortical synapses to express synaptic scaling. J. Neurosci.30, 14685–14690 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu, C., Bin, Blakely, R. D. & Hewlett, W. A. The proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha activate serotonin transporters. Neuropsychopharmacology31, 2121–2131 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Recasens, M. et al. Chronic exposure to IL-6 induces a desensitized phenotype of the microglia. J. Neuroinflamm.18, 31 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Baganz, N. L. & Blakely, R. D. A dialogue between the immune system and brain, spoken in the language of serotonin. ACS Chem. Neurosci.4, 48–63 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Uddin, M. et al. Epigenetic and inflammatory marker profiles associated with depression in a community-based epidemiologic sample. Psychol. Med.41, 997–1007 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boneu, B., Abbal, M. & Plante, J. & R. Bierme. Factor-VIII complex and endothelial damage. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. nucl. Med.116 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Li, Y. et al. Plasma von Willebrand factor level is transiently elevated in a rat model of acute myocardial infarction. Exp. Ther. Med.10, 1743–1749 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mcgrath, R. T. et al. Altered glycosylation of platelet-derived Von Willebrand factor confers resistance to ADAMTS13 proteolysis. Blood122, 4107–4110 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Aguila, S. et al. Increased Galactose Expression and Enhanced Clearance in Patients with Low von Willebrand Factor. Blood133, 1585–1596 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Hope, S. et al. Similar immune profile in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: selective increase in soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I and Von Willebrand factor. Bipolar Disord. 11, 726–734 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files) are available. The other data analyzed in the current study are not publicly available for ethical reasons. A previous version of this article was published as a preprint on medRxiv: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.24.24304794.