Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematological malignancy characterized by the unrestricted proliferation of plasma cells that secrete immunoglobulin in the bone marrow. Extracted primarily from Anemone raddeana regel, Raddeanin A (RA) is a natural triterpenoid saponin compound with anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor activities. However, most research on the anti-tumor effects of RA has concentrated on solid tumors, with little exploration into non-solid tumors like MM. Furthermore, there is a dearth of research investigating the interplay between RA and MM, encompassing their interaction targets and mechanisms. This study aims to delve into the biological activity and molecular mechanism of RA’s anti-MM properties through the lens of network pharmacology and experimental validation. The findings from GO enrichment analysis, KEGG enrichment analysis, and molecular docking prediction suggested a potential correlation between the MAPK signaling pathway, including the MAPK1 gene (also known as ERK2), and the impact of RA on MM. Results from the CCK-8 assay revealed a time-dependent and concentration-dependent inhibition of proliferation in MM cell lines treated with RA. Notably, in the cell lines used for the test, the IC50 values for MM.1 S cells were 1.616 µM at 24 H and 1.058 µM at 48 H, for MM.1R cells were 3.905 µM at 24 H and 2.18 µM at 48 H, while for RPMI 8226 cells, they were 6.091 µM at 24 H and 3.438 µM at 48 H. The PI, Annexin V-FITC/PI, and JC-1 staining showed that RA could arrest the cell cycle in the G2 phase, cause apoptosis, and induce the change of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) in MM cells. Treated with RA, the Western blot analysis showed that the expression levels of Bim, Cleaved Caspase 3/9, and Cleaved PARP were increased, and the expression level of Mcl-1 was decreased in MM cells. Concurrently, the phosphorylated protein expression levels of p-ERK1/2, p-MSK1, p-P90RSK, and p-MEK1/2 were diminished following RA treatment. These results suggest that RA has the activity of anti-MM, and the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway is involved in the growth inhibition effect of RA on MM cells via cycle arrest and mitochondrial-pathway-dependent apoptosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-76465-z.

Keywords: Raddeanin A, Multiple myeloma, Apoptosis, Network pharmacology, MAPK/ERK signaling pathway

Subject terms: Cancer, Drug discovery

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is one of the most common malignant tumors, accounting for about 10% of the tumors in the blood system, and the abnormal proliferation of plasma cells is its main feature1,2. It can cause a variety of complications, such as bone damage, kidney damage, anemia, and hypercalcemia3. Chemotherapy is still the main treatment for MM, but it could have serious side effects and reduce the quality of life for patients. Although immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors are currently used for anti-MM, they can cause peripheral neuropathy and hematotoxicity, and the median survival of patients was shorter4–6. Hence, there is a growing need for innovative, safe, and efficient targeted small-molecule antineoplastic medications. Numerous antineoplastic drugs utilized in clinical practice are derived from natural sources, and naturally-occurring phytochemicals hold promise as antineoplastic agents7. As a result, there is a heightened focus on discovering antineoplastic drugs from phytochemicals.

Raddeanin A (RA) is a natural triterpenoid saponin compound extracted mainly from Anemone raddeana regel which was a traditional Chinese medicine to promote blood circulation, eliminate blood stasis, and treat rheumatism8. RA has demonstrated antineoplastic activity through the inhibition of proliferation and invasion. Besides, it can induce apoptosis of various human carcinogenic cells, including colorectal tumors, breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancer9–12. Several studies have also explored the combination of RA with other drugs, such as cisplatin, to enhance therapeutic efficacy in human carcinoma10. Furthermore, RA has been observed to mitigate 5-fluorouracil resistance in cholangiocarcinoma cells13. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of research on RA’s impact on non-solid tumors like MM. Simultaneously, comprehensive analysis of the pharmacological properties of RA in MM is infrequent. Network pharmacology offers the advantage of evaluating core targets and signaling pathways across the dimensions of “drug-target-pathway-disease”. Therefore, network pharmacology can be employed to systematically analyze the biological activity and underlying mechanisms of RA in the context of tumors. For example, a study found that RA may regulate the PI3K/AKT pathway in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by network pharmacology and this prediction had been experimentally verified14. Hence, this study utilized network pharmacology to preliminarily predict the pertinent targets and associated signaling pathways of RA in MM. Cell experiments were then employed to validate the anti-tumor activity and mechanism of RA. These findings are anticipated to offer fresh perspectives on the anti-tumor mechanism of RA, potentially positioning it as a viable medication.

Materials and methods

Materials

The RPMI-1640 medium was procured from Gbico (USA) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) from ZETA Life (USA). The cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) and BSA were obtained from Biosharp (China). The mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1, Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit, cell cycle and apoptosis analysis kit, and RIPA lysis buffer were from Beyotime Biotechnology (China). ProteinSafe™ phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and ProteinSafe™ protease inhibitor cocktail (EDTA-free) were obtained from TransGen Biotech (China). The ultrasensitive ECL chemiluminescence substrate was purchased from Tanon (China). The BCA protein quantitative kit was obtained from Vazyme (China). The antibodies against Bim, Mcl-1, PARP, Cleaved PARP, Cleaved Caspase 3/9, p-ERK1/2, p-MSK1, p-P90RSK, p-MEK1/2, GAPDH, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies were purchased from CST ( USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Drug

Raddeanin A, purchased from Solarvbio (Beijing, China, Cat. No.SR8010) with a purity of 99.58%, was wholly dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at -80 ℃.

Cell culture

MM.1 S cells, MM.1R cells which is the steroid-based resistant strain of MM1S, and RPMI 8226 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cryopreserved in a liquid nitrogen tank in the laboratory. According to the culture method recommended by ATCC, the cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2.

Network pharmacology analyze

Prediction of target genes for RA and MM

The Pharm Mapper database (http://lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/index.html) and Swiss Target Prediction database (http://swisstargetprediction.ch/) were consulted to predict RA targets, and repeats between the two databases were deleted. The targets of MM were obtained from Gene Cards (https://www.genecards.org/) and OMIM (https://www.omim.org/). Then duplicate and erroneous targets were normalized and removed using the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). Finally, The Venny 2.1 online tool (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) was used to obtain target gene intersecting.

Construction of PPI network

The Search Tool STRING database (https://string-db.org/) was used to construct the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network for selecting target genes. We utilized a cutoff value of ≥ 0.9 (high-confidence interaction score) to ensure reliability of obtaining significant PPIs in network visualization. The selected target genes were imported to demonstrate the gene interactions using Cytoscape 3.9.0 software.

Gene function and pathway enrichment analysis

After obtaining the intersection of genes, the DAVID database(https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) was used to perform Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses for target gene function and pathways15–17. Then, the top 10 terms associated with BP (Biological Process), CC (Cellular Component), and MF (Molecular Function) according to the p-value (p < 0.05) and gene count, were selected for enrichment analyses and visualization by HeLixLife (http://www.helixlife.cn). The gene networks related to the top 5 with BP, CC, and MF were demonstrated using Cytoscape 3.9.0 software. In addition, according to the results of the KEGG enrichment analysis, the top 20 pathways were screened and visualized by HeLixLife.

Molecular docking

To study the association between active ingredients and hub targets by molecular docking, RA structure file was downloaded from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and the crystal structure of MAPK1 was from the Protein Database (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/). The molecular docking research was carried out using AutoDock 4.0 software. Then, the binding energy predicted by the docking conformation was sorted and assessed. Affinity < − 4.25 kcal/mol indicates the presence of binding activity between ligand and target; affinity < − 5.0 kcal/mol implies good binding activity; affinity < − 7.0 kcal/mol suggests strong docking activity18. The Pymol program was used to visualize binding patterns.

Cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assays

MM.1 S, MM.1R and RPMI 8226 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were inoculated into 96-well cell culture plates at the same density. Subsequently, RA at concentrations of 0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 µM were added and incubated for 24 and 48 H. CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for another 2 H. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer VICTOR Nivo, Waltham, MA, USA). GraphPad Prism 9.0 software was used to draw the cells growth curves after being treated with RA and calculate the maximum median inhibitory concentration (IC50) value.

Flow Cell Cytometry (FCM) assays

After being exposed to RA at various concentrations for 24 H, MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells were subjected to Annexin V-FITC/PI staining, and the cell apoptosis rate was assessed using FCM.

The MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells underwent treatment with RA at various concentrations for 12 H. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol at 4 ℃ overnight, stained with propidium iodide (PI), and then subjected to FCM for cell cycle detection.

Following treatment with RA at various concentrations for 24 H, the MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells were stained with the lipophilic fluorescent probe JC-1 to detect the change of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) using FCM.

Western blot assays

After being treated with RA for 24 H, MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells were lysed in a RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm (Haier LX-165T2R, China) for 20 min at 4 ℃. BCA method was used to determine protein concentration. To ensure consistency, the protein mass, volume, and concentration were adjusted to the same levels, and 50 µg of total proteins were separated which based on different molecular weights by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). These proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (PVDF) via wet electro-transfer at 250 mA/H. Then, the PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% BSA at 37℃ for 1 H and incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with their respective primary antibodies. After that, The PVDF was incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 2 H. The ultrasensitive ECL chemiluminescence substrate, enhanced chemiluminescence system (Bio-Rad ChemiDocXRS, Hercules, CA, USA), and Quantity-One image acquisition software (Bio-Rad, USA) were used to visualize the blots. The Image-J analysis software was employed to determine the integrated optical density (IOD) values of the protein blot. To determine the relative expression levels of the target protein, GAPDH was used as the internal reference protein. The IOD of the target protein was divided by the IOD of the internal reference protein, and this value reflected the relative expression levels of the target protein.

Statistical assays

The statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Each set of experiments was repeated three times independently, and the results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The differences between multiple groups were evaluated using one-way ANOVA and the Dunnett t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant when compared to the control group.

Results

RA inhibits the proliferation of MM cells

The results of CCK-8 showed that RA inhibited the proliferation of MM cells, including MM.1 S, MM1R, and RPMI 8226 cells, in a time-dependent and concentration-dependent manner. Among the three cell lines, RA showed the highest inhibitory activity against MM.1 S, followed by MM.1R, and then RPMI 8226. Notably, the IC50 values for MM.1 S cells were 1.616 µM at 24 H and 1.058 µM at 48 H, for MM.1R cells were 3.905 µM at 24 H and 2.18 µM at 48 H, while for RPMI 8226 cells, they were 6.091 µM at 24 H and 3.438 µM at 48 H (Fig. 1). As MM.1R is derived from MM.1 S, we choose MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells for subsequent experiments to explore the anti-MM mechanism of RA.

Fig. 1.

Growth inhibitory effect of RA on MM cells. The cells were treated with RA for 24 H and 48 H, and then the cell viability was detected using the CCK-8 method. Chemical structure diagram of RA (A). The growth curves of the MM.1 S cells (B), MM.1R cells (C), and RPMI 8226 cells (D) were drawn using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software.

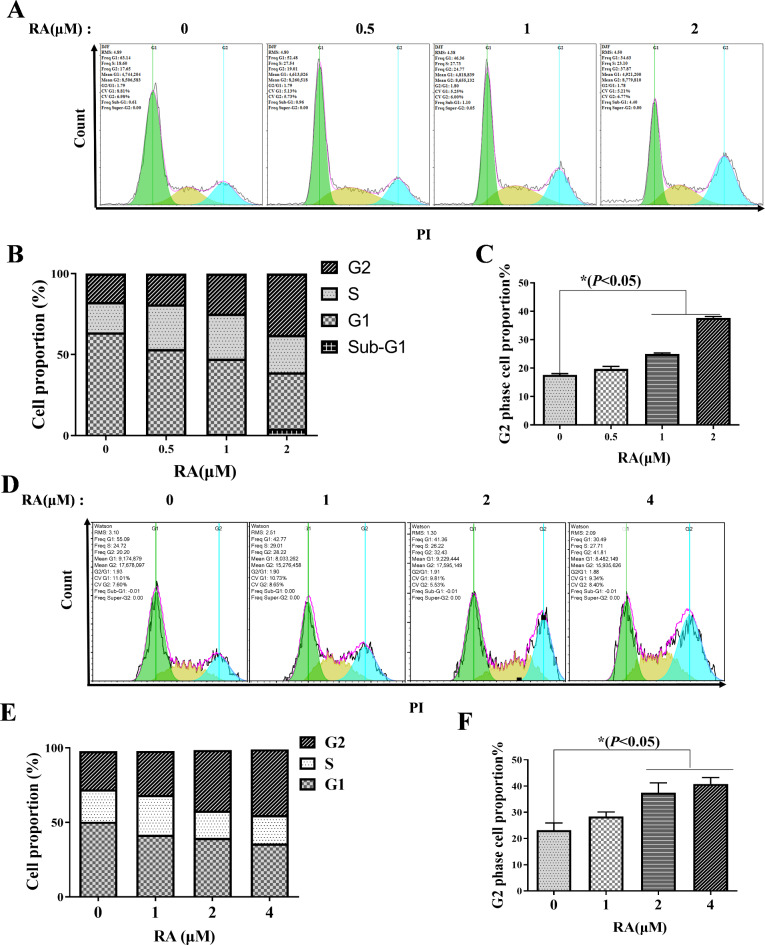

RA induces MM cells cycle arrest in G2 phase

To elucidate the anti-proliferation mechanism of RA, MM cells treated with RA for 12 H were stained with propidium iodide (PI) to detect the cell cycle distribution by FCM. The results showed that the rates of MM.1 S cells in the G2 phase were 17.6%±1.53%, 19.67%±2.37%, 24.72%±2.61%, 37.63%±2.32%, respectively, after the effects of RA (0, 0.5, 1, 2 µM) (Fig. 2A-C). And the rates of RPMI 8226 cells in the G2 phase were 21.41%±2.03% ,27.99%±1.36%,34.67%±3.2% ,40.38%±1.87%, respectively, after the effects of RA (0, 1, 2, 4 µM) (Fig. 2D-F). These findings demonstrate that RA effectively arrests the cell cycle of MM cells at G2 phase.

Fig. 2.

Cell cycle arrest effect of RA on MM cells. After RA treatment for 12 H, the PI-stained MM.1 S cells were collected and the cell cycle distribution was analyzed via FCM (A); GraphPad Prism 9.0 software analyzed MM.1 S cell proportions at different stages of the cell cycle (B); G2 phase cell proportion in MM.1 S (C); The PI-stained RPMI 8226 cells were analyzed via FCM (D); Cell proportions at different stages of the RPMI 8226 cell cycle (E); G2 phase cell proportion in RPMI 8226 (F). The comparison between the experimental group and the no-treatment control, *P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

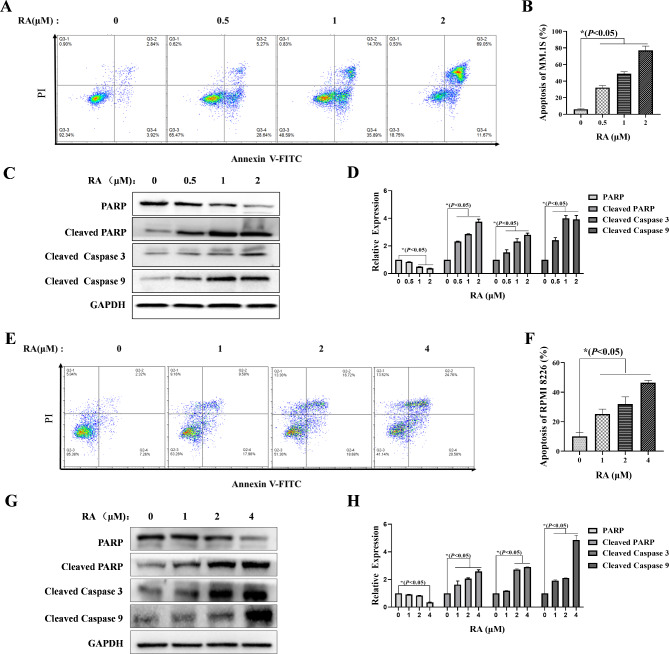

RA induces MM cells apoptosis via mitochondrial pathway

To further investigate the effect of RA on MM cells, FCM was used to analyze apoptosis of MM cells stained by Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and PI after RA treatment for 24 H. The results showed that RA could induce MM cells apoptosis significantly. Compared to 0 µM RA, the apoptosis rate of the MM.1 S cells treated with 2 µM RA increased from 6%±3.27–80.73%±4.73% (Fig. 3A, B), and the apoptosis rate of the RPMI 8226 cells treated with 4 µM RA increased from 9.99%±2.76–46.43%±1.53% (Fig. 3E, F). Then, Western blot was used to detect the expression of apoptosis-related proteins. The results showed that expression levels of pro-apoptotic proteins, such as Cleaved PARP and Cleaved Caspase 3/9, were significantly increased in MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells (Fig. 3 C, D and G, H). These results confirm that RA inhibits the proliferation of MM cells by inducing apoptosis.

Fig. 3.

Apoptosis effect of RA on MM cells. After treatment with RA for 24 H, the FCM was used to collect the MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells, which stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI to analyze the effects of RA on MM.1 S (A) and RPMI 8226 (E) cells apoptosis. Western blot was used to analyze the expression level of apoptosis-related proteins in MM.1 S (C) and RPMI 8226 (G) cells. The percentage of apoptosis and the relative expression levels of proteins were reflected by GraphPad Prism 9.0 software plots histograms (B, D, F, H). In comparison the experimental group with the no-treatment control, *P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

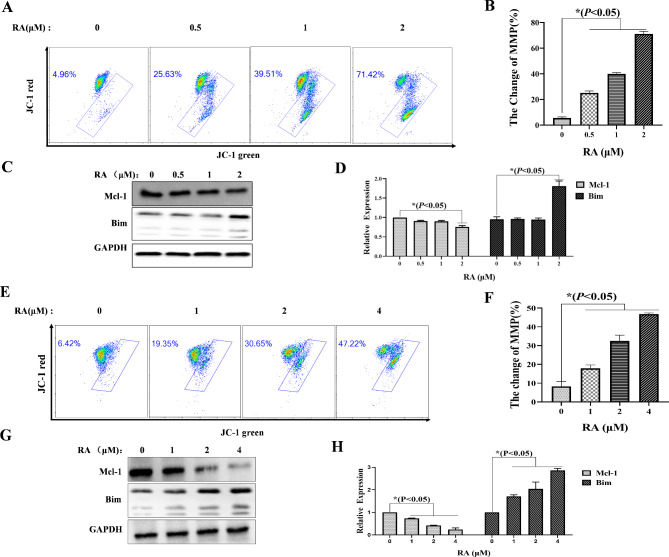

The mitochondrial pathway is an important pathway involved in apoptosis. To further investigate whether RA induced apoptosis of MM cells through mitochondrial pathways. FCM was used to collect MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells stained by JC-1 to detect changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) after RA treatment for 24 H. It was found the proportions of MMP change in MM.1 S cells after treatment with 2 µM RA increased from 5.16%±3.16–70.62%±4.12%, compared to no-treatment control (Fig. 4A, B). And the proportions of MMP change in RPMI 8226 cells after treatment with 4 µM RA increased from 8.29%±2.67–46.84%±0.56%, compared to the no-treatment control (Fig. 4E, F). Then, we further used Western blot to detect the expression of mitochondrial pathway-related proteins. The results showed that the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 decreased, while the pro-apoptotic protein Bim increased (Fig. 4 C, D and G, H). These results suggest that the mitochondrial pathway may be involved in RA inducing apoptosis of MM cells.

Fig. 4.

The mitochondrial pathway effect of RA on MM cells. After treatment with RA for 24 H, the FCM was used to collect the MM cells, which stained with JC-1 fluorescent probes, and to analyze the effects of RA on the changes of MMP in MM.1 S (A) and RPMI 8226 (E) cells. Western blot was used to analyze the expression level of apoptosis-related proteins of MM.1 S (C) and RPMI 8226 (G) cells. The rate of change in MMP and the relative expression levels of proteins were reflected by GraphPad Prism 9.0 software plots histograms (B, D, F, H). In comparison the experimental group with the no-treatment control, *P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The target prediction for RA and MM

Drugs can exert anti-tumor activity by acting on multiple targets in the tumor. To further investigate the possible potential relationship between RA and MM. Pharm Mapper database, Swiss Target Prediction database, Gene Cards, and OMIM were used for data collection, with a Relevance score > 10 as screening criteria. And 58 interaction predicted targets between RA and MM were screened (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

The prediction of targets for RA anti-MM. (A) Venn diagram of potential targets of RA anti-MM; (B) PPI network of 58 Intersection targets.

Then, the STRING database was used to analyze 58 interaction targets, obtain a PPI network, and generate a PPI relationship network diagram with 58 points and 160 edges. Next, Cytoscape 3.9.0 software was used to visually analyze the PPI network diagram. The result suggests that SRC, AKT1, STAT3, PIK3R1, HRAS, MAPK1 (also called ERK2), and other genes were identified as central targets for RA on MM (Fig. 5B).

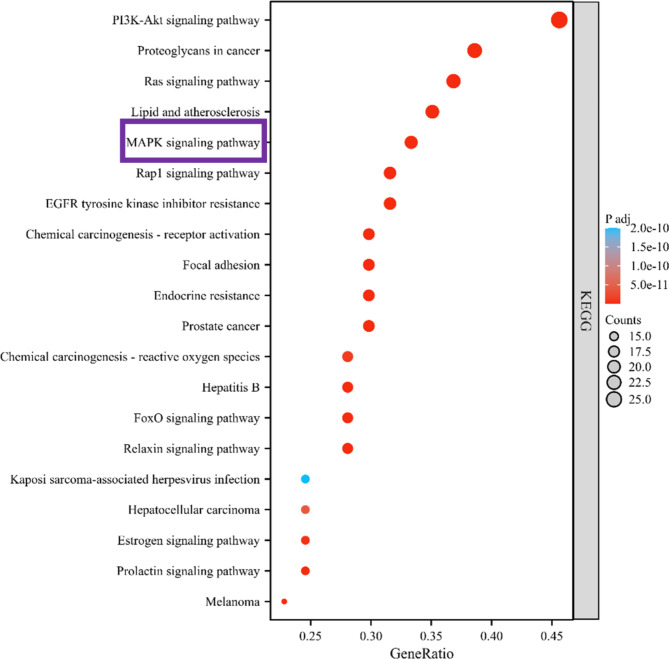

MAPK/ERK signaling pathway is involved in RA anti-MM by GO and KEGG analysis

Next, we used the DAVID database to perform GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of the corresponding targets and visualized the results. With GO enrichment analysis, we screened the top 10 biological processes (GO: BP), cellular components (GO: CC), and molecular functions (GO: MF) (Fig. 6A). The results of BP enrichment suggested that the intersection gene was mainly involved in the positive regulation of kinase activity, positive regulation of Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, and other biological reactions. The results of CC enrichment showed that the intersection genes were mainly distributed in the cellular components such as the transcription regulator complex membrane microdomain, cell-substrate junction, etc. The enrichment results of MF suggest that the intersection gene is mainly through protein tyrosine kinase activity, protein serine kinase activity, and other combinations play a role. Then, we further mapped the gene networks related to the top 5 BP, CC, and MF. And the MAPK1 gene was found to be associated with BP, CC, and MF (Fig. 6B, C, D).

Fig. 6.

GO enrichment analysis for RA anti-MM. (A) GO enrichment analysis, including 10 molecular function bar graphs (BP), 10 biological process bar graphs (CC), and 10 cell component bar graphs; (B) Network diagrams of top 5 BP in GO enrichment analysis; (C) Network diagrams of top 5 CC in GO enrichment analysis; (D) Network diagrams of top 5 MF in GO enrichment analysis.

To further elucidate the underlying signaling pathways modulated by RA in MM, the study conducted an analysis of KEGG pathways. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis predicted that in addition to the PI3K/AKT pathway which has been reported19, the MAPK signaling pathway was one of the pathways closely related to the target gene (Fig. 7). MAPK signaling pathways, including p38, JNK, ERK5, and ERK, play a vital role in cell growth, development, and death19–21. Meanwhile, MAPK1 is one of the target proteins in the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Therefore, based on the above results, we speculate that the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway will be regulated after MM treating with RA.

Fig. 7.

The bar chart of the top 20 signal pathways in the KEGG enrichment analysis.

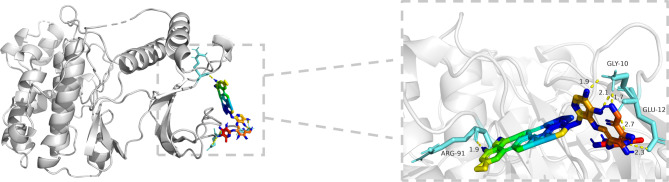

Molecular docking predicts the effective binding of RA to MAPK1

According to the results of the PPI network, GO enrichment analysis, and KEGG enrichment analysis, MAPK1 was selected for molecular docking with RA. The result showed RA was combined with MAPK1 through 6 hydrogen bonds, and the affinity is -12.85 kcal/mol, which suggests vigorous docking activity (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Docking complexes of MAPK1 and RA. The binding residues are shown using PyMoL software.

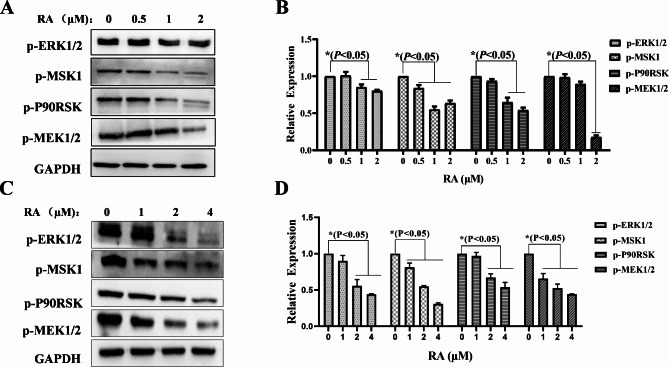

The MAPK/ERK signaling pathway is involved in the apoptosis of MM cells

To validate the network pharmacology results, Western blot was used to detect the expression levels of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway-related proteins in MM.1 S and RPMI 8226 cells treated with RA. The results found that the phosphorylated protein expression levels of p-ERK1/2, p-MSK1, p-p90RSK, and p-MEK1/2 were significantly decreased (Fig. 9). Based on the afore mentioned findings, we speculate that RA modulates the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway while apoptosis in MM cells (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

MAPK/ERK cascade signaling pathway modulated by RA on MM cells. Western blot analysis of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway related proteins expression in MM.1 S (A) and RPMI 8226 cells (C); the relative expression levels of proteins were reflected by GraphPad Prism 9.0 software plots histograms (B, D), *P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Fig. 10.

A model for demonstrating the effects and mechanism of RA on cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MM cells.

Discussion

There have been significant advances in the treatment of MM over the past 20 years, but it is still no cure completely22. Many studies have shown the beneficial mechanism of Traditional Chinese Medicine(TCM) in treating cancer23, which provides a novel option for anti-MM. RA is oleanane class triterpenoid saponin isolated extracted from the rhizomes of the Anemone raddeana regel. RA has been found to induce apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells and inhibit metastasis24. In addition, it is reported that RA inhibited cervical cancer (CC) cell proliferation, invasion, and migration25. However, most of the previous studies have focused on RA against solid tumors, and there are few studies on non-solid tumors such as MM. Our study found that RA can inhibit MM cells proliferation in a time-dependent and concentration-dependent manner. Further results showed that RA arrests the cell cycle of MM in the G2 phase.

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that removes harmful or damaged cells from the body to maintain stability26. Changes in effector molecules associated with apoptosis, such as the Caspase protein family, regulate alterations in cell morphology and biochemical processes27. In addition, poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) is a polymerase that plays a crucial role in the repair of cellular DNA damage28. PARP can be cleaved by a variety of Caspases29,30. Cleavage of PARP is considered an essential indicator of apoptosis and is often considered an indicator of Caspase 3 activation31,32. It was found that compared with the no-treatment control, the apoptosis rate of the MM cells after RA treatment for 24 H increased. And the results of Western blot showed that apoptosis-related proteins, such as Cleaved PARP and Cleaved Caspase 3/9, were significantly increased. These results suggest that RA can induce apoptosis in MM.

Mitochondria, as the central organelles of cells, coordinates the physiological processes such as apoptosis33–35. MMP change is an early marker of apoptosis36,37. Because mitochondria play an essential role in cancer cell survival, many drugs target mitochondria-mediated cancer cell death38,39. The Bcl-2 protein family regulates apoptosis by controlling mitochondrial permeability40,41. The Bim in the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family can reside in the cytoplasm and translocate into mitochondria after receiving death signal transduction, promoting the release of the pro-apoptotic substance cytochrome C42. Mcl-1 is an anti-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 protein family that exerts anti-apoptotic effects by antagonizing the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family43,44. It was found that the MMP of MM cells significantly changed after RA treatment for 24 H. Western blot results showed that the expressions of anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 decreased. In contrast, the pro-apoptotic protein Bim increased. These results suggest that the mitochondrial pathway is involved in the apoptotic process of MM cells induced by RA.

The waning efficacy of drug discovery in the biomedical sphere necessitates a novel and pragmatic approach to address this issue45–47. This challenge has been met with the advent of network pharmacology, a discipline rooted in systems and network medicine, and its therapeutic48. Recently, many studies screened drug components and potential targets by network pharmacology49,50. This study predicted 58 interaction targets between RA and MM through network pharmacology. After screening the data, Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAPK1) and other genes were identified as central targets for RA on MM by PPI network. GO enrichment analysis showed that the MAPK1 gene was associated with BP, CC, and MF in MM acted with RA. In addition, molecular docking showed that RA had good binding activity with MAPK1. MAPK1, also known as extracellular regulated kinase (ERK2), a serine/threonine kinase, is one of the proteins in the MAPK signaling pathway that regulates various cellular processes51. KEGG enrichment analysis also showed that the MAPK signaling pathway plays an important role in the development of MM when RA acts on MM. As one of the most studied regulatory cascades, the MAPK pathway regulates the direction of cell growth growth52. Anti-tumor research through the MAPK pathway is a great entry point53.MAPK signaling pathways, including p38, JNK, ERK5, and ERK, play a vital role in cell growth, development, and death19–21. The study has showed that RA can inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis by regulating the JNK and STAT3 signaling pathways in human osteosarcoma54. RA has also been reported to inhibit gastric cancer cell proliferation through the MAPK/P38 signaling pathway20. Moreover, It is reported that over-activation of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway can promote tumorigenesis, so regulating the MAPK/ERK pathway can be used as one of the approaches to anti-tumor55. Based on these, we conducted vitro experiments to verify the results of network pharmacology. The study focused on the expression levels of MAPK/ERK pathways related proteins in MM cells after being treated with RA. The study discovered that the expression of phosphorylated proteins involved in the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway decreased, including p-ERK1/2, p-MSK1, p-p90RSK, and p-MEK1/2. These results suggest that RA may induce apoptosis in MM cells through the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. In fact, we got consistent results in 3 MM cell lines including MM.1R which data also presented in the attachment.

Studies have found that RA has antitumor activity against a variety of solid tumors56, and RA may be a promising anticancer compound. However, for RA, there is still a long way to go in clinical application. Such as drug delivery system, it was reported a pegylated liposome loaded with RA for prostate cancer therapy57. In this study, the anti-MM activity and molecular mechanism of RA were investigated by network pharmacology and in vitro cell experiments. Subsequent studies will be extended to animal models and clinical specimens to further evaluate therapeutic efficacy and in vivo safety.

Conclusions

RA has been found to have good anti-tumor activity and essential research value. Our study showed that RA has an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of MM cells. And RA induces apoptosis in MM cells by arresting the cell cycle, inducing the change of MMP, triggering the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, and regulating the MAPK/ERK cascade signaling. The results of this study provide a reference for the clinical treatment of MM and expand the anti-MM mechanism of RA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, P.Y. and M.H.L.; Investigation, M.Z.J., C.L., C.M.M., H.Y., Y.C.Z., S.Q.P, R.Z.L., Y.J.L. and D.Y.Z.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, M.Z.J., C.L. and C.M.M.; Writing-Review & Editing, P.Y. and M.H.L. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program of China (No.2023NSFSC0725, No.2022NSFSC0690), the Open Fund of Development and Regeneration Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province of China (No.SYS20-06), the National Undergraduates Innovating Experimentation Project of China (No.202313705009, No.202213705001), the Research and Innovation Fund for Postgraduate of Chengdu Medical College of China (No. YCX2022-02-05).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ming-zheng Jiang, Chen Li and Chun-mei Mao.

Contributor Information

Ping Yang, Email: yangping@cmc.edu.cn.

Min-hui Li, Email: liminhui@cmc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Pawlyn, C. & Morgan, G. J. Evolutionary biology of high-risk multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 17(9), 543–556 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar, S. V. et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 15(12), e538–e548 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Usmani, S. Z. et al. Teclistamab, a B-cell maturation antigen x CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MajesTEC-1): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1 study. Lancet. 398(10301), 665–674 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harousseau, J. L., Dreyling, M. & Group, E. G. W. Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical Practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 21(Suppl 5), v155–7 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Davis, L. N. & Sherbenou, D. W. Emerging therapeutic strategies to Overcome Drug Resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel). 13(7) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Gandhi, U. H. et al. Outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma refractory to CD38-targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. Leukemia. 33(9), 2266–2275 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barathan, M. et al. Naturally occurring phytochemicals to target breast cancer cell signaling. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Wu, B. et al. Raddeanin a inhibited epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and angiogenesis in glioblastoma by downregulating beta-catenin expression. Int. J. Med. Sci. 18(7), 1609–1617 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang, Q. et al. Raddeanin A suppresses breast cancer-associated osteolysis through inhibiting osteoclasts and breast cancer cells. Cell. Death Dis. 9(3), 376 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, J. N. et al. Synergy of Raddeanin A and cisplatin induced therapeutic effect enhancement in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 485(2), 335–341 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan, Y. Y. et al. Raddeanin A, a triterpenoid saponin isolated from Anemone Raddeana, suppresses the angiogenesis and growth of human colorectal tumor by inhibiting VEGFR2 signaling. Phytomedicine. 22(1), 103–110 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, L. et al. Raddeanin A induced apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells by promoting ROS-mediated STAT3 inactivation. Tissue Cell. 71, 101577 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo, S. S., Wang, Y. & Fan, Q. X. Raddeanin A promotes apoptosis and ameliorates 5-fluorouracil resistance in cholangiocarcinoma cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 25(26), 3380–3391 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing, Y. et al. Raddeanin A promotes autophagy-induced apoptosis by inactivating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 396(9), 1987–1997 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28(11), 1947–1951 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D587–d592 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsin, K. Y., Ghosh, S. & Kitano, H. Combining machine learning systems and multiple docking simulation packages to improve docking prediction reliability for network pharmacology. PLoS One. 8(12), e83922 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Win, S., Than, T. A. & Kaplowitz, N. The regulation of JNK Signaling pathways in Cell Death through the interplay with mitochondrial SAB and Upstream Post-translational effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(11). (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Teng, Y. H. et al. Autophagy protects from raddeanin A-induced apoptosis in SGC-7901 human gastric cancer cells. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2016, 9406758 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Peti, W. & Page, R. Molecular basis of MAP kinase regulation. Protein Sci. 22(12), 1698–1710 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elnair, R. A. & Holstein, S. A. Evolution of treatment paradigms in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Drugs. 81(7), 825–840 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng, Y. et al. An overview of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment after Radical Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell Carcinoma. 10, 2305–2321 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma, B. et al. Raddeanin A, a natural triterpenoid saponin compound, exerts anticancer effect on human osteosarcoma via the ROS/JNK and NF-kappaB signal pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 353, 87–101 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen, X. et al. Raddeanin A inhibits proliferation, invasion, migration and promotes apoptosis of cervical cancer cells via regulating miR-224-3p/Slit2/Robo1 signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 13(5), 7166–7179 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obeng, E. Apoptosis (programmed cell death) and its signals - a review. Braz J. Biol. 81(4), 1133–1143 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pistritto, G. et al. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging (Albany NY). 8(4), 603–619 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satoh, M. S. & Lindahl, T. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) formation in DNA repair. Nature. 356(6367), 356–358 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazebnik, Y. A. et al. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 371(6495), 346–347 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen, G. M. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem J, 326 (Pt 1)(Pt 1): pp. 1–16. (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Tewari, M. et al. Yama/CPP32 beta, a mammalian homolog of CED-3, is a CrmA-inhibitable protease that cleaves the death substrate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Cell. 81(5), 801–809 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholson, D. W. et al. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 376(6535), 37–43 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peruch, M. et al. Subcellular effectors of Cocaine Cardiotoxicity: all roads lead to Mitochondria-A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 24(19) (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Martinez-Reyes, I. & Chandel, N. S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 102 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, C., Park, S. H. & Yoon, S. K. Genetic mutations affecting mitochondrial function in cancer drug resistance. Genes Genomics. 45(3), 261–270 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green, D. R., Galluzzi, L. & Kroemer, G. Mitochondria and the autophagy-inflammation-cell death axis in organismal aging. Science. 333(6046), 1109–12 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Wei, M. et al. Effect of fluoride on cytotoxicity involved in mitochondrial dysfunction: a review of mechanism. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 850771 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh, P. et al. Mitochondria Targeting as an effective strategy for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 21(9). (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Vasan, K., Werner, M. & Chandel, N. S. Mitochondrial metabolism as a target for Cancer Therapy. Cell. Metab. 32(3), 341–352 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brenner, D. & Mak, T. W. Mitochondrial cell death effectors. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 21(6), 871–877 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chalah, A. & Khosravi-Far, R. The mitochondrial death pathway. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 615, 25–45 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsay, J., Esposti, M. D. & Gilmore, A. P. Bcl-2 proteins and mitochondria–specificity in membrane targeting for death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1813(4), 532–539 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato, T. et al. Interactions among members of the Bcl-2 protein family analyzed with a yeast two-hybrid system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 91(20), 9238–9242 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou, P. et al. Mcl-1, a Bcl-2 family member, delays the death of hematopoietic cells under a variety of apoptosis-inducing conditions. Blood. 89(2), 630–643 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scannell, J. W. et al. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11(3), 191–200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loscalzo, J. Personalized cardiovascular medicine and drug development: time for a new paradigm. Circulation. 125(4), 638–645 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nosengo, N. Can you teach old drugs new tricks? Nature. 534(7607), 314–316 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nogales, C. et al. Network pharmacology: curing causal mechanisms instead of treating symptoms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 43(2), 136–150 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiu, Z. K. et al. A network pharmacology study with molecular docking to investigate the possibility of licorice against posttraumatic stress disorder. Metab. Brain Dis. 36(7), 1763–1777 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu, X. et al. Hesperetin promotes diabetic wound healing by inhibiting ferroptosis through the activation of SIRT3. Phytother. Res. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Petrosino, M. et al. The complex impact of cancer-related missense mutations on the stability and on the biophysical and biochemical properties of MAPK1 and MAPK3 somatic variants. Hum. Genomics. 17(1), 95 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin-Vega, A. & Cobb, M. H. Navigating the ERK1/2 MAPK Cascade. Biomolecules. 13(10) (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Sui, X. et al. p38 and JNK MAPK pathways control the balance of apoptosis and autophagy in response to chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Lett. 344(2), 174–179 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, Z. et al. Antitumor activity of Raddeanin A is mediated by Jun amino-terminal kinase activation and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 inhibition in human osteosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 110(5), 1746–1759 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kun, E. et al. MEK inhibitor resistance mechanisms and recent developments in combination trials. Cancer Treat. Rev. 92, 102137 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naz, I. et al. Anticancer potential of Raddeanin A, a natural triterpenoid isolated from Anemone Raddeana Regel. Molecules. 25(5) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.He, K. et al. A Pegylated Liposome loaded with raddeanin A for prostate Cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 4007–4021 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.