Abstract

The correlation between the Cobb angle and the sagittal spinal curvature (SSC) in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) has been reported in some previous studies, but few studies have reported on the relation of coronal wedge deformity (CWD) with sagittal curvature. This study aims to investigate the correlation between CWD and SSC in AIS patients. A retrospective analysis was conducted in 122 AIS patients treated at our hospital from January 2018 to November 2023. Correlation analysis was performed on the Cobb angle, total wedge angle(TW), apical vertebral wedge angle (APW), upper end-vertebral wedge angle (UW), lower end-vertebral wedge angle (LW), total affected structures, average wedge angle(AW), total vertebral wedge angle (TVW), average vertebral wedge angle (AVW), Vertebral Wedge Angle ratio (VWR), total disc wedge angle (TDW), average disc wedge angle (ADW), and disc wedge angle ratio (DWR). Furthermore, out of all cases which underwent lateral spinal radiographs, a correlation analysis between thoracic kyphosis (TK), lumbar lordosis (LL) and CWD was carried out on 102 patients. The Cobb angle exhibited a significant positive correlation with multiple CWD parameters (P < 0.05). TK showed a significant negative correlation with the Cobb angle (r = − 0.221, P = 0.026), TW (r = − 0.199, P = 0.045), AW (r = − 0.262, P = 0.008), TDW (r = − 0.211, P = 0.033), and ADW (r = − 0.278, P = 0.005). LL had no significant correlation with TK and other parameters (P > 0.05). In mild and moderate AIS patients, CWD parameters were positively correlated with the Cobb angle and negatively correlated with thoracic SSC. This may indicate that it’s necessary to correct sagittal thoracic curvature when rectifying scoliosis in clinic. This research would not only provide new insights for clinical practice but also offer important evidence for early diagnosis and intervention.

Keywords: Spine, Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, Cobb angle, Wedge deformity, Thoracic kyphosis, Lumbar lordosis, Correlation analysis

Subject terms: Paediatric research, Bone, Musculoskeletal abnormalities

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) stands as one of the most common spinal deformities among adolescents, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 2 to 3% within this demographic1. Beyond merely affecting posture, AIS can lead to significant complications, including respiratory limitations, chronic pain, and psychological challenges2–5. The Cobb angle remains the gold standard for assessing scoliosis severity, but it is essential to recognize that the spine undergoes complex alterations across the transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes as AIS progresses. The previous studies had increasingly focused on coronal plane wedge deformities in AIS patients; however, much of this work tended to examine parameters in isolation, often overlooking the critical relationships between coronal wedge deformity and changes in sagittal physiological curvatures6–8. Some studies suggested that the Cobb angle may consist of contributions from both vertebrae and disc wedging angles9,10. This deformation may be a crucial factor in the progression of spinal curvature, as it can affect the mechanical properties of the spine, leading to pathological spinal bending. Additionally, the sagittal physiological curvature of the spine plays a vital role in the overall stability and load distribution of the spine11,12. Changes in sagittal curvature may exacerbate spinal deformity and impact the functional abilities of the patient13. Various hypotheses have been proposed regarding the development of scoliosis14–18, each presenting diverse perspectives on the underlying mechanisms and interrelationships among factors such as vertebral rotation, changes in sagittal curvature, coronal scoliosis, and anterior column growth. The complexity of the human body often renders these theoretical models inadequate, highlighting the need for empirical evidence to support these hypotheses. Moreover, while numerous studies explored treatment options for spinal abnormalities19–21, a critical question remains: how should we approach the understanding and treatment of these deformities? An evidence-based, causal, and holistic treatment perspective is essential, emphasizing the importance of clarifying the relationships among different planes and shapes of spinal deformities. Identifying any unified correlations between these planes could lead to more efficient problem-solving and better management strategies.

The primary aim of this study is to investigate the relationships among the Cobb angle, vertebral wedge deformity, and sagittal physiological curvature of the spine. By systematically analyzing these interrelationships, we seek to uncover the mechanisms underlying AIS development and their implications for spinal structure and function. This research not only aims to provide new insights for clinical practice but also aspires to offer possible evidence for early diagnosis and intervention. Ultimately, we hope to enhance management strategies for AIS patients, thereby improving their quality of life and clinical outcomes. To achieve these objectives, we conducted a retrospective analysis of data from AIS patients who underwent full-length anteroposterior and lateral spinal radiographs at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (ZCMU) over a five-year period. We investigated the relationships between various parameters in the coronal plane, and the correlation between coronal plane parameters and the physiological curvature in the sagittal plane. The findings are presented herein.

Methods

Participants

This retrospective case study analyzed AIS patients who had full-length spinal X-rays taken at The Third Affiliated Hospital of ZCMU from January 2018 to November 2023. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) meeting the diagnostic criteria of the Society on Scoliosis Orthopedic and Rehabilitation Treatment (SOSORT) 2016 Guidelines for the orthopedic and rehabilitation treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis during growth spurt22; (2) aged between 10 and 18 years old; (3)45°≥Cobb angle ≥ 15°; (4) All included images were taken when the patients were diagnosed with scoliosis for the first time. Exclusion criteria were: (1) congenital or any other clearly identified causes of secondary scoliosis; (2) history of spinal tumors, tuberculosis, or other relevant diseases; (3) previous history of spinal surgery.

Radiographic Metrics

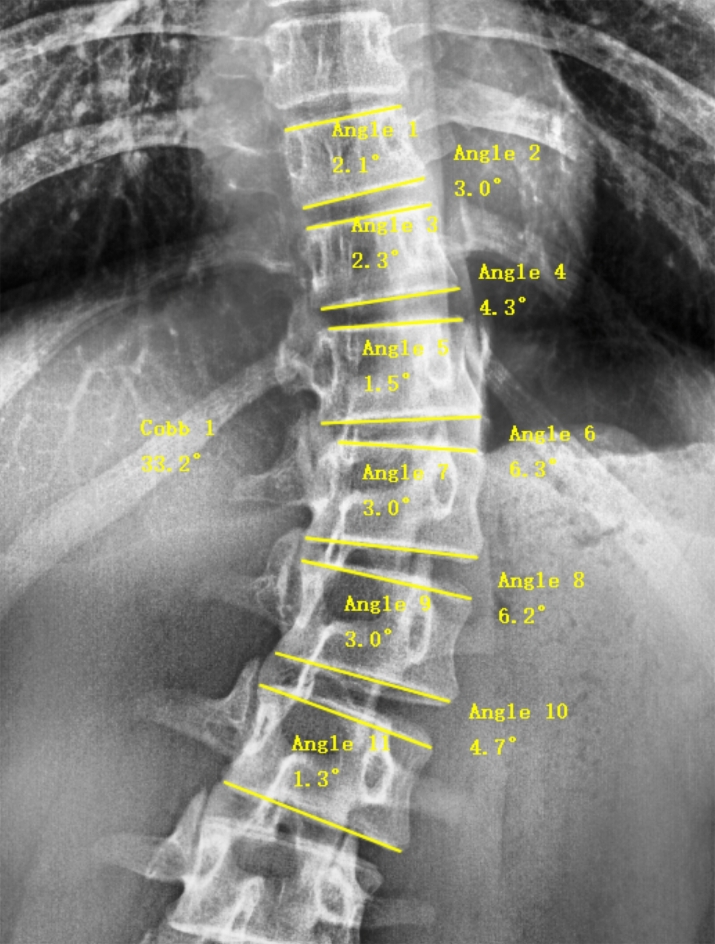

All included subjects underwent standing full-length anteroposterior X-rays of the spine, and all data were measured using Surgimap software. Following the method described by Will et al.23, the Cobb angle of the scoliosis and the wedge angles affecting the vertebrae and intervertebral discs were measured on the anteroposterior X-rays (Fig. 1): (1) total vertebral wedge angle (TVW): vertebral wedge angle is the angle between parallel lines drawn along the upper and lower borders of the vertebrae, TVW means the sum of all affected vertebral wedge angles; (2) total disc wedge angle (TDW): disc wedge angle is the angle between parallel lines drawn along the lower border of one vertebra and the upper border of the adjacent vertebra, TDW means the sum of all affected intervertebral disc wedge angles; (3) total wedge angle (TW): the sum of TVW and TDW; (4) upper end-vertebral wedge angle (UW): the wedge angle of the most inclined vertebra at the upper end; (5) lower end-vertebral wedge angle (LW): the wedge angle of the most inclined vertebra at the lower end; (6) apex-vertebral wedge angle (APW): the wedge angle of the apex vertebra in the scoliosis curve; (7) average wedge angle (AW): the TW divided by the number of affected vertebrae and intervertebral discs; (8) average vertebral wedge angle (AVW): the TVW divided by the number of affected vertebrae; (9) average disc wedge angle (ADW): the TDW divided by the number of affected intervertebral discs; (10) vertebral wedge angle ratio (VWR): the proportion of TVW to TW; (11) disc wedge angle ratio (DWR): the proportion of TDW to TW. Mild scoliosis is defined as a Cobb angle between 10° and 25° (10°≤Cobb angle < 25°), while moderate scoliosis is defined as a Cobb angle between 25° and 45° (25°≤Cobb angle < 45°).

Fig. 1.

Surgimap software measurement for Cobb angle and wedge angle.

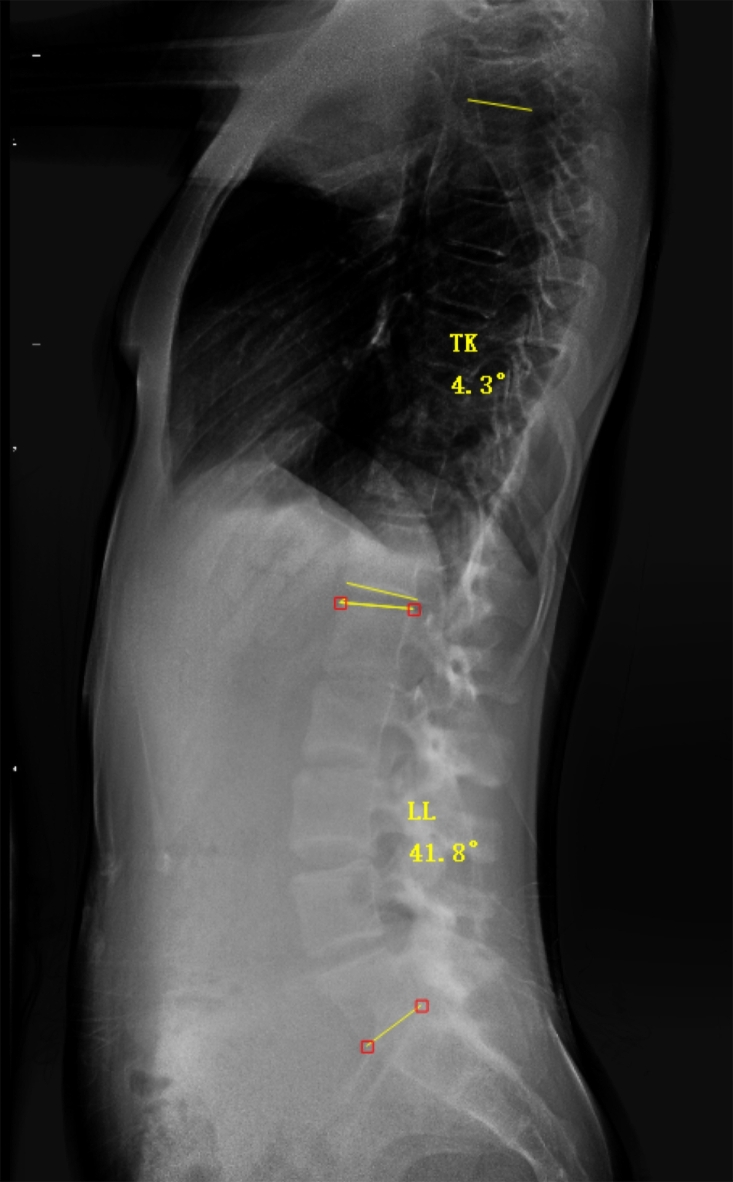

In the 102 AIS patients who also underwent full-length lateral spine X-rays, TK and LL were measured using the following method (Fig. 2): (1) TK: the angle between the extension lines of the upper border of T5 and the lower border of T12 vertebra; (2) LL: the angle between the extension lines of the upper border of L1 and the lower border of L5 vertebra.

Fig. 2.

Surgimap software measurement method for TK and LL.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 software, and continuous data were presented as mean (standard deviation)

Statement

Approval for the study was obtained from the ethics committee at the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (ZSLLKY-2017-045). This work was supported by the Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant No. 2022ZA088) and Key Discipline Project of High level TCM of National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GJXK2023-85). The funding sources were not involved in the design, analysis, or writing process. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and used for patients’ diagnosis and therapeutic assessment, as part of routine treatment. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the ethics committee at the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Results

General observations

According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 122 patients were included in the study for coronal parameter analysis, with 102 patients undergoing full-length spine lateral radiographs to obtain sagittal parameters. Among the 122 patients, there were 20 males and 102 females. The age ranged from 10 to 18 years, with a mean age of 13.94(2.26) years. The Cobb angle ranged from 15° to 42°, and the mean Cobb angle was 25.36(7.04) °. The patients were classified based on the characteristics of the curve location, direction, and severity. Lumbar curves were more prevalent, while thoracic and thoracolumbar curves were less common. Leftward curves were more frequent than rightward curves, and mild curves were predominant. Details are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of objects.

| Total | Gender | Scoliosis severity | Major curve | Curve direction | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Mild | Moderate | Thoracic | Thoracolumbar | Lumbar | Right | Left | |||||

| Case | 122 | 20 | 102 | 66 | 56 | 6 | 28 | 88 | 17 | 108 | |||

Table 2.

Basic information of factors.

|

|

Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Cobb angle | 25.36(7.04) | 15.0–42.0 |

| TW | 27.30(8.17) | 13.8–52.2 |

| APW | 5.52(2.52) | 0.9–14.7 |

| UW | 1.14(0.88) | 0.1–4.4 |

| LW | 1.56(1.21) | 0.1–5.4 |

| Total affected structures | 9.99(2.21) | 7–17 |

| AW | 2.81(0.90) | 1.21–6.01 |

| TVW | 10.18(4.46) | 2.4–26.4 |

| Affected vertebrae | 5.50(1.10) | 4–9 |

| AVW | 1.88(0.84) | 0.48–4.7 |

| VWR | 0.37(0.12) | 0.12–0.69 |

| TDW | 17.12(5.95) | 5.4–32.0 |

| Affected disc | 4.49(1.11) | 3–8 |

| ADW | 3.97(1.54) | 1.35-10 |

| DWR | 0.63(0.12) | 0.31–0.88 |

| TK | 18.90(10.18) | 2-41.3 |

| LL | 39.06(11.05) | 9.9–63.2 |

Correlation of coronal plane parameters in AIS patients

The correlation analysis of coronal plane parameters in AIS patients revealed significant positive correlations between the Cobb angle and TW (r = 0.922, P < 0.001). Additionally, TW exhibited significant correlations with APW (r = 0.433, P < 0.001), UW (r = 0.385, P < 0.001), LW (r = 0.262, P = 0.004), total number of affected structures (r = 0.215, P = 0.018), AW (r = 0.813, P < 0.001), TVW (r = 0.679, P < 0.001), number of affected vertebrae (r = 0.223, P = 0.014), AVW (r = 0.596, P < 0.001), TDW (r = 0.851, P < 0.001), number of affected intervertebral discs (r = 0.212, P = 0.019), and ADW (r = 0.651, P < 0.001). The number of affected structures was significantly correlated with TW (r = 0.215, P = 0.018) and LW (r = − 0.231, P = 0.010) but not with the Cobb angle (r = 0.098, P = 0.281) (Table 3). In the comparison between mild and moderate scoliosis patients, VWR in mild patients (0.38(0.12)) was slightly larger than in moderate patients (0.37(0.12)), and DWR in mild patients (0.62(0.12)) was slightly smaller than in moderate patients (0.63(0.12)); but the differences were not significant statistically. VWR were significantly smaller in mild patients (t = − 12.41, P < 0.001) and moderate patients (t = − 2.78, P < 0.01) compared to DWR (Table 4).

Table 3.

Correlation analysis of coronal plane parameters.

| Cobb | TW | APW | UW | LW | Total affected structures | AW | TVW | Affected vertebrae | AVW | VWR | TDW | Affected disc | ADW | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TW | r | 0.922** | |||||||||||||

| P | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||

| APW | r | 0.391** | 0.433** | ||||||||||||

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||

| UW | r | 0.326** | 0.385** | 0.139 | |||||||||||

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.125 | ||||||||||||

| LW | r | 0.268** | 0.262** | 0.058 | 0.099 | ||||||||||

| P | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.528 | 0.276 | |||||||||||

| Total affected structures | r | 0.098 | 0.215* | − 0.145 | 0.089 | − 0.231* | |||||||||

| P | 0.281 | 0.018 | 0.110 | 0.331 | 0.010 | ||||||||||

| AW | r | 0.809** | 0.813** | 0.498** | 0.305** | 0.391** | − 0.360** | ||||||||

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| TVW | r | 0.628** | 0.679** | 0.165 | 0.464** | 0.389** | 0.155 | 0.543** | |||||||

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.089 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Affected vertebrae | r | 0.110 | 0.223* | − 0.150 | 0.082 | − 0.228* | 0.996** | − 0.352** | 0.161 | ||||||

| P | 0.226 | 0.014 | 0.100 | 0.370 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.077 | |||||||

| AVW | r | 0.591** | 0.596** | 0.213* | 0.438** | 0.508** | − 0.223* | 0.697** | 0.902** | − 0.220* | |||||

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.015 | ||||||

| VWR | r | 0.031 | 0.031 | − 0.218* | 0.296** | 0.316** | 0.060 | − 0.009 | 0.719** | 0.060 | 0.675** | ||||

| P | 0.734 | 0.735 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.509 | 0.923 | 0.000 | 0.514 | 0.000 | |||||

| TDW | r | 0.794** | 0.851** | 0.461** | 0.158 | 0.072 | 0.180* | 0.693** | 0.241** | 0.186* | 0.183* | − 0.447** | |||

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.081 | 0.434 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.040 | 0.043 | 0.000 | ||||

| Affected disc | r | 0.095 | 0.212* | -0.144 | 0.090 | − 0.233** | 1.000** | − 0.362** | 0.153 | 0.995** | − 0.225* | 0.060 | 0.177 | ||

| P | 0.300 | 0.019 | 0.114 | 0.325 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.093 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.509 | 0.051 | |||

| ADW | r | 0.662** | 0.651** | 0.525** | 0.090 | 0.153 | − 0.373** | 0.849** | 0.100 | − 0.363** | 0.255** | − 0.486** | 0.813** | − 0.375** | |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.323 | 0.092 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.273 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| DWR | r | − 0.031 | − 0.031 | 0.218* | − 0.296** | − 0.316** | − 0.060 | 0.009 | − 0.719** | − 0.060 | − 0.675** | − 1.000** | 0.447** | − 0.060 | 0.486** |

| P | 0.734 | 0.735 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.509 | 0.923 | 0.000 | 0.514 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.509 | 0.000 |

*. The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). **. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed)

Table 4.

Comparisons of VWR and DWR among mild and moderate AIS patients.

| Mild | Moderate | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VWR | 0.38(0.12) | 0.37(0.12) | 0.356 | 0.722 |

| DWR | 0.62(0.12) | 0.63(0.12) | − 0.356 | 0.722 |

| t | − 12.41 | − 2.78 | ||

| P | 0.000 | 0.007 |

Correlation of LL, TK with coronal parameters in AIS patients

The correlation analysis of sagittal and coronal parameters in AIS patients revealed significant negative correlations between TK and the Cobb angle (r = − 0.221, P = 0.026), TW (r=-0.199, P = 0.045), AW (r = − 0.262, P = 0.008), TDW (r = − 0.211, P = 0.033), and ADW (r = − 0.278, P = 0.005). However, TK showed no significant correlation with number of affected structures, and TVW (P > 0.05). LL exhibited no significant correlations with TK, Cobb angle, and coronal plane wedge deformities (P > 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation of LL, TK with coronal parameters.

| TK | LL | Cobb | TW | APW | UW | LW | Total affected structures | AW | TVW | Affected vertebrae | AVW | VWR | TDW | Affected disc | ADW | DWR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK | r | 1.000 | 0.154 | − 0.221* | − 0.199* | 0.047 | − 0.151 | − 0.009 | 0.076 | − 0.262** | − 0.054 | 0.072 | − 0.115 | 0.071 | − 0.211* | 0.078 | − 0.278** | − 0.071 |

| P | 0.123 | 0.026 | 0.045 | 0.639 | 0.129 | 0.926 | 0.446 | 0.008 | 0.593 | 0.470 | 0.251 | 0.475 | 0.033 | 0.435 | 0.005 | 0.475 | ||

| LL | r | 0.154 | 1.000 | − 0.036 | − 0.022 | − 0.088 | − 0.019 | 0.066 | 0.083 | − 0.071 | 0.049 | 0.080 | 0.033 | 0.092 | − 0.047 | 0.082 | -0.085 | − 0.092 |

| P | 0.123 | 0.716 | 0.824 | 0.378 | 0.850 | 0.508 | 0.409 | 0.481 | 0.623 | 0.424 | 0.744 | 0.358 | 0.639 | 0.411 | 0.397 | 0.358 | ||

*The correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). **. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Discussion

AIS, which is one of the major causes affecting the spinal health in teenagers, could lead to restricted lung expansion, decreased diaphragmatic movement, and asymmetrical breathing, all which could affect the cardiopulmonary function of patients, resulting in secondary pulmonary heart disease24,25. Our study included 122 patients with 20 males and 102 females. The age ranged from 10 to 18 years. This is consistent with the epidemiological pattern of AIS. Girls tend to be more commonly affected with increasing age, and the ratio of girls to boys among children with spinal curvatures greater than 20° is 5:126. The Hong Kong cohort study found that during adolescence, AIS was more common in girls than in boys with sex ratios of 2.7 for spinal curves of ≥ 10°, 4.5 for spinal curves of ≥ 20°27. The musculoskeletal system in adolescence is a gradually developing tension structure. This means that the length of compressed bones, tensioned muscles and ligaments increase to maintain musculoskeletal tension and integrity. The vertebrae grow through chondrocytes in the growth plates and intervertebral discs28–30. Crijns et al. used a physical model of a growing thoracolumbar spine to demonstrate that an impeded elongation of the tendons leads to internal compression of the spine, which first straightens and then slowly warps out of the sagittal plane by lateral bending and -inevitably- axial rotation31. There is a mismatch between the growth of the spine and the connected structures, resulting in internal stress and three-dimensional deformation of the spinal scoliosis. Growth can be modulated by mechanical stress. This phenomenon is described by the Hueter-Volkmann law32, which states that increased pressure on growth plates slows bone growth, whereas decreased pressure or tension accelerates growth. As for AIS, the Hueter-Volkmann law is considered the basis for the wedge deformation of vertebral bodies in the last stage of AIS33. Some researchers believe that the Cobb angle should be equal to TW6. The present results show that there is a certain difference although they are significantly correlated. We don’t think that the scoliotic curve is a standard arc because of the different stiffness of discs, vertebral bodies, and surrounding muscles and ligaments which can affect the Cobb angle. Meanwhile, variations in measurements of the Cobb angle by different measurers can also lead to differences between TW and the Cobb angle. Furthermore, our results also show that TVW, TDW, AVW, ADW are all significantly correlated with the Cobb angle, but the correlation coefficients with ADW are greater than those with AVW, like previous studies. Will et al.23 reported that the increase of disc wedges was greatest in the early stage, while vertebral wedge increases fastest in the later stage. They concluded that AIS initially increases through disc wedge deformation during rapid growth spurts, followed by progressive vertebral wedge deformation. In the comparison between mild and moderate patients, there was no statistically significant difference in the VWR and DWR. We suggest that our findings were different from the previous studies because there was only mild and moderate AIS patients in our study and the increase in vertebral wedge deformation tends to accelerate in the later stages of scoliosis. However, the DWR was consistently greater than VWR in mild and moderate patients. Therefore, disc wedge deformation may have a greater impact on mild and moderate scoliotic progression. In another study, Cheung et al.34 found a significant difference in wedge deformity between the progressing group and the non-progressing group, with the progression group showing a more significant trend of wedge deformation during growth. The sequence of wedge deformity development is related to the segment of the scoliosis. In most thoracic curves, vertebral wedge deformity formed firstly, but in most lumbar curves, vertebral wedge deformity occurs after disc wedge deformity. Will et al.23 reported that the increase in intervertebral disc wedging was largest in the early stage with increased vertebral wedging in the later stage and concluded that curve progression started in the intervertebral disc followed by vertebral changes. Based on the previous study and our research findings, patients with significant disc wedging deformation but less vertebral wedging deformation may be in the early stage of scoliosis and are more suitable for conservative treatment.

Characteristic imaging changes of scoliosis, which demonstrates varying degrees of wedging of vertebrae and intervertebral discs within the scoliotic curve, occurs even in mild scoliosis and develops with the progression of scoliosis, the most wedging vertebra is always at the apex vertebra. Literatures have reported vertebral and disc wedging in patients with scoliosis35,36, with some researchers suggesting that the asymmetrical growth on the left and right sides of vertebrae in AIS patients leads to wedging of vertebrae and intervertebral discs37,38. Dickson et al.39 considered that double asymmetry in both coronal and sagittal planes was an important feature of AIS. When the skeletal system of adolescents is not yet fully developed, vertebral growth is regulated by biomechanics, in which spinal growth is inhibited under compress while accelerated under tension following the Hueter-Volkmann law, and then leading to wedging of vertebrae and discs.

Previous studies40–42 have found that the maximum wedge angle occurs at the apex vertebra, and the wedge angle gradually decreases with extending bilaterally towards the upper and lower end-vertebrae. Our study also shows that there is larger APW in most thoracic AIS patients. However, in some lumbar scoliosis patients’ X-rays, the wedge angle of end-vertebra is not the smallest, which may be due to structural changes in the upper vertebrae transmitting stress to the lower end-vertebrae or greater pressure exerted by the pelvis on the lower end-vertebra than the stress on the vertebral bodies in the midline of the scoliotic curve, this may indicate that some AIS is actually caused by asymmetric growth of three-dimensional asymmetric stress in the vertebral body due to pelvic rotation. Burwell et al.43 first proposed a mechanism between the spine and pelvis in the pathogenesis of AIS. They hypothesized that pelvic rotation transfers torsion to the spine but did not provide further explanation. Begon et al.44 suggested that pelvic rotation may change muscular function connecting the pelvis and spine, which may be the reason why the stress on the lower end vertebra differs from other vertebral bodies. In the treatment of AIS patients, especially those with lumbar scoliosis, correcting pelvic rotation may also achieve corrective effects by improving balance of stress acting on the vertebral body. Furthermore, there is a significantly positive correlation between APW and the Cobb angle, indicating that the deformation of the apex vertebra can reflect the overall coronal curvature of the spine to some extent. Interestingly, UW and LW are also significantly positively correlated with the Cobb angle, and there are significant correlations between APW, UW, LW, and TVW, AVW, indicating a positive correlation between the stress on vertebrae within the scoliotic segment and structural deformity, as well as the overall coronal curvature of the spine composed of wedging of affected vertebrae and discs. Although our study did not find a significant correlation between the Cobb angle and the number of affected vertebrae or discs, it showed a weak correlation between TW and these two parameters. It indicates that the length of the curve may affect the severity of scoliosis which is mostly influenced by wedge deformity of vertebrae or discs. Another possibility is that since wedging deformation occurs in the late stage of scoliosis, the increase in the number of wedge-shaped structures may be a secondary change caused by the body’s dispersion of unbalanced stress.

In our previous study, it had been observed that patients with mild to moderate scoliosis experience a reduction in thoracic sagittal curvature, while lumbar physiological curvature almost remains unchanged45. This finding is consistent with another research46,47. Mac-Thiong et al.48 suggested that the changes in TK are mainly related to the shape and orientation of the thoracic vertebrae and intervertebral discs, which have changed in patients with AIS. Consequently, TK deviates from those of the normal population, and this difference is more significant in thoracic AIS patients. However, previous studies on the correlation between coronal and sagittal curvatures in AIS patients have mostly focused on the Cobb angle, neglecting the relationship between coronal wedging deformation and sagittal curvature. This study observed and analyzed the correlation between several coronal vertebral and discal wedge angles and TK, LL. It was found that TK has a significant negative correlation with the Cobb angle, TW, AW, TDW, and ADW, while no significant correlation was observed with other parameters of wedge deformation. This suggests that, in terms of changes in thoracic sagittal curvature in AIS patients, the impact of disc wedge variation may be more significant than that of vertebral wedge variation. And the significant correlations that the parameters of wedge deformity show with the Cobb angle in the coronal plane and the physiological curvature in the sagittal plane indicate that wedge deformity might reflect the overall three-dimensional changes in the spine, which could be useful in assessing and understanding the complexities of spinal deformities and their implications for treatment and prognosis. This might explain why some previous studies showed no significant change49 or an increase50 in TK in scoliosis patients. Although our study demonstrated a significant correlation between TK and disc wedge deformity, LL showed no significant correlation with various wedge parameters. This result aligns with our previous research and the findings of most other studies, indicating that changes in lumbar sagittal curvature are not significantly correlated with scoliosis51,52. This could be attributed to the deformations in thoracic scoliosis being primarily formed by the flexible intervertebral discs. Factors contributing to this variation of deformation may include differences in vertebral size, tissues near the vertebrae, or spinal flexibility between the thoracic and lumbar regions. The smaller size of thoracic vertebral bodies compared to the lumbar region53 results in a greater force when the same pressure is applied, especially considering the uneven distribution of back muscles and the proximity of ribs to the thoracic vertebrae. Consequently, the composition of tissues near the vertebrae between thoracic and lumbar scoliotic curves may differ, leading to variations in spinal wedge deformity. Since an increase in the Cobb angle is associated with reduced spinal mobility54, and the lumbar spine is more flexible than the thoracic spine, studies have found a positive correlation between curve stiffness and vertebral wedge angles in X-rays55. Therefore, the flexibility of scoliotic curves may influence the segmental growth where wedge deformities occur. This is likely related to the pathogenesis of scoliosis. During treatment, we may increase the flexibility of the patient’s spine through interventions such as manipulations56,57 to improve effectiveness of conservative treatments. Prior research has indicated that LL is not strongly correlated with spinal morphology but is influenced by pelvic anatomical shape, determining LL in AIS patients48. This is considered a primary reason for the relatively stable LL in AIS patients. Based on the above findings, the occurrence of scoliosis is partly due to the asymmetric growth caused by the unbalanced tension on the vertebral body. We suggest a better corrective effect could be achieved by self-stretching for the concave side of the trunk during specific exercise for scoliosis and actively correcting the abnormal position of the patient’s pelvis to balance the asymmetric stress. This may also be part of the reason why physiotherapeutic scoliosis specific exercises (PSSE) are effective. According to the Hueter-Volkmann law, the unbalanced tension on vertebrae results in slower growth on the pressure side and faster growth on the tension side. So, where does the initial tension that causes deformation of the intervertebral disc and vertebrae come from? Crijns and his colleagues used a physical model of a growing thoracolumbar spine to demonstrate that restricted stretching of soft tissues leads to internal compression of the spine23, which may be the reason behind the formation of this wedging-force. This indicates that during treatment, especially for patients in the early stages who have not yet developed severe wedge deformities, the approach may focus on alleviating the restricted stretching of soft tissues and strengthening the paravertebral muscles to increase their size and function, thereby balance the tension on the vertebrae to break the vicious cycle of scoliosis.

Limitation

This is a retrospective study and the sample sizes for different types of AIS patients are inconsistent, especially with a limited number of severe curvature cases. Consequently, a comparative analysis of these cases cannot be conducted. Additionally, the study did not observe changes in various parameters during the progression of scoliosis in the same patients, making it challenging to definitively establish whether wedge deformities genuinely alter with the progression of curve. We will conduct further research to compare the changes of wedge deformity and sagittal plane physiological curvature after different treatments. Additionally, future studies including more patients with severe AIS may be helpful to provide guidance for more refined and scientific-backed surgical approaches in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, the wedge deformity of vertebrae and discs in the coronal plane are positively correlated with the Cobb angle in AIS patients. The sagittal curvature of the thoracic vertebrae is significantly negatively correlated with coronal wedge deformity, whereas lumbar vertebral physiological curvature shows no significant correlation with coronal wedge deformity. This may indicate that it’s necessary to correct sagittal thoracic curvature when rectifying scoliosis in clinic. Improving the physiological curvature of patients may achieve improvements in wedge deformity and coronal trunk imbalance, and then alleviate symptoms or poor posture related to scoliosis. Future studies should include a more diverse range of subjects and conduct more detailed and precise stratified research to delve deeper into the correlation between coronal parameters and thoracic and lumbar sagittal curvature in different types of AIS patients.

Author contributions

Y. X. M linked the cohort and oversaw data management. S. Y analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Q. F. P and P. Y. S assisted in editing and proofreading manuscripts, collecting references. All authors participated in the design of the study, interpretation of the results, and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the ethics committee at the 3rd affiliated hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yi Shen, Feipeng Qin and Yingsen Pan contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Xiaoming Li and Xiaoming Ying contributed equally and should be considered as joint corresponding authors.

Contributor Information

Xiaoming Li, Email: 20145019@zcmu.edu.cn.

Xiaoming Ying, Email: 28588509@qq.com.

References

- 1.IllésT. S., Lavaste, F. & Dubousset, J. F. The third dimension of scoliosis: The forgotten axial plane. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res.105, 351–359 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branthwaite, M. A. Cardiorespiratory consequences of unfused idiopathic scoliosis. Br. J. Dis. Chest. 80, 360–369 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ascani, E. et al. Natural history of untreated idiopathic scoliosis after skeletal maturity. Spine11, 784–789 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson, J. H., Mirkovic, S., Noble, P. C., Nalty, T. & Erwin, W. D. Results of operative treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adults. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. Vol.77, 513–523 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pehrsson, K., Bake, B., Larsson, S. & Nachemson, A. Lung function in adult idiopathic scoliosis: A 20 year follow up. Thorax46, 474–478 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding, Q. et al. Contributions of vertebral and disc wedging to the Cobb angle in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with different curve pattern: Radiographic discrepancy and clinical significance. Chin. J. Spine Spinal Cord. 21, 708–713 (2011). (In Chinese.). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, S. F. et al. Disc and vertebral wedging and their clinical significance in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and neurological scoliosis. Chin. J. Spine Spinal Cord. 20, 94–97 (2010). (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian, B. P. et al. Progression of vertebral and disc wedging in immature porcine scoliosis model and its significance. Chin. J. Spine Spinal Cord. 23, 151–155 (2013). (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stokes, I. A. Analysis and simulation of progressive adolescent scoliosis by biomechanical growth modulation. Eur. Spine Journal: Official Publication Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deformity Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc.16, 1621–1628 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stokes, I. A. & Aronsson, D. D. Disc and vertebral wedging in patients with progressive scoliosis. J. Spinal Disord.14, 317–322 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abelin, G. K. Sagittal balance of the spine. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res., 107,102769 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Le Huec, J. C., Thompson, W., Mohsinaly, Y., Barrey, C. & Faundez, A. Sagittal balance of the spine. Eur. Spine J. Offi. Pub. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deformity Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc., 28 (2019).

- 13.Pasha, S., de Reuver, S., Homans, J. F. & Castelein, R. M. Sagittal curvature of the spine as a predictor of the pediatric spinal deformity development. Spine Deformity. 9, 923–932 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pialasse, J. P., Descarreaux, M., Mercier, P. & Simoneau, M. Sensory reweighting is altered in adolescent patients with scoliosis: Evidence from a neuromechanical model. Gait Posture. 42, 558–563 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami, K. et al. Olfactomedin-like protein OLFML1 inhibits Hippo signaling and mineralization in osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.505, 419–425 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riddle, H. F. & Roaf, R. Muscle imbalance in the causation of scoliosis. Lancet268, 1245–1247 (1955). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan, A. X. et al. Assessment of biomechanical properties of paraspinal muscles in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 98, 3485–3489 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira Fernandes, M. & Tourtellotte, W. G. Egr3-dependent muscle spindle stretch receptor intrafusal muscle fiber differentiation and fusimotor innervation homeostasis. J. Neuroscience: Official J. Soc. Neurosci.35, 5566–5578 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceballos-Laita, L. et al. The effectiveness of Schroth method in Cobb angle, quality of life and trunk rotation angle in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med.59, 228–236 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romano, M. et al. SEAS (Scientific exercises approach to scoliosis): A modern and effective evidence based approach to physiotherapic specific scoliosis exercises. Scoliosis10, 3 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Büyükturan, Ö., Kaya, M. H., Alkan, H., Büyükturan, B. & Erbahçeci, F. Comparison of the efficacy of Schroth and Lyon exercise treatment techniques in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomized controlled, assessor and statistician blinded study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract.72, 102952 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Negrini, S. et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disorders. 13, 3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Will, R. E., Stokes, I. A., Qiu, X., Walker, M. R. & Sanders, J. O. Cobb angle progression in adolescent scoliosis begins at the intervertebral disc. Spine34, 2782–2786 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi, Z. et al. Pulmonary function after thoracoplasty and posterior correction for thoracic scoliosis patients. Int. J. Surg.. 11, 1007–1009 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma, X. H. The impact of scoliosis on pulmonary function and pulmonary function recovery. J. Clin. Pulmonary Med.18, 1675–1677 (2013). (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trobisch, P., Suess, O. & Schwab, F. Idiopathic Scoliosis Deutsches Arzteblatt Int., 107, 875–884 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luk, K. D. et al. Clinical effectiveness of school screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A large population-based retrospective cohort study. Spine35, 1607–1614 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bylski-Austrow, D. I., Glos, D. L., Wall, E. J. & Crawford, A. H. Scoliosis vertebral growth plate histomorphometry: Comparisons to controls, growth rates, and compressive stresses. J. Orthop. Research: Official Publication Orthop. Res. Soc.36, 2450–2459 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bush, P. G., Parisinos, C. A. & Hall, A. C. The osmotic sensitivity of rat growth plate chondrocytes in situ; clarifying the mechanisms of hypertrophy. J. Cell. Physiol.214, 621–629 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovett, R. W. A contribution to the study of the mechanics of the spine. Am. J. Anat.2, 457–462 (1903). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crijns, T. J., Stadhouder, A. & Smit, T. H. Restrained Differential Growth: The initiating event of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Spine42, E726–E732 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roaf, R. Vertebral growth and its mechanical control. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol.42-B, 40–59 (1960). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stokes, I. A., Spence, H., Aronsson, D. D. & Kilmer, N. Mechanical modulation of vertebral body growth. Implications for scoliosis progression. Spine21, 1162–1167 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung, W. K. & Cheung, J. P. Y. Contribution of coronal vertebral and IVD wedging to Cobb angle changes in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis during growth. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.23, 904 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majcher, P., Fatyga, M., Krupski, W. & Tatara, M. The radiological imaging of the vertebral body and intervertebral discs wedging in idiopathic, right-side, thoracic scoliosis as a prognostic factor of the angular progression of spine curve. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil.5, 659–665 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satake, K. et al. Analysis of the lowest instrumented vertebra following anterior spinal fusion of thoracolumbar/lumbar adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Can we predict postoperative disc wedging? Spine30, 418–426 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stokes, I. A. & Laible, J. P. Three-dimensional osseo-ligamentous model of the thorax representing initiation of scoliosis by asymmetric growth. J. Biomech.23, 589–595 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Millner, P. A. & Dickson, R. A. Idiopathic scoliosis: biomechanics and biology. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deformity Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc.5, 362–373 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickson, R. A., Lawton, J. O., Archer, I. A. & Butt, W. P. The pathogenesis of idiopathic scoliosis. Biplanar spinal asymmetry. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol.66, 8–15 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Modi, H. N. et al. Differential wedging of vertebral body and intervertebral disc in thoracic and lumbar spine in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis—A cross sectional study in 150 patients. Scoliosis3, 11 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parent, S., Labelle, H., Skalli, W. & de Guise, J. Vertebral wedging characteristic changes in scoliotic spines. Spine29, E455–E462 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villemure, I., Aubin, C. E., Grimard, G., Dansereau, J. & Labelle, H. Progression of vertebral and spinal three-dimensional deformities in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A longitudinal study. Spine26, 2244–2250 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burwell, R. G. et al. Pathogenesis of idiopathic scoliosis. The Nottingham concept. Acta Orthop. Belg.58 (Suppl 1), 33–58 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Begon, M., Scherrer, S. A., Coillard, C., Rivard, C. H. & Allard, P. Three-dimensional vertebral wedging and pelvic asymmetries in the early stages of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Journal: Official J. North. Am. Spine Soc.15, 477–486 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, H. Y. et al. Imaging study on thoracic and lumbar physiological curvature in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 37, 26–32 (2024). (In Chinese). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abelin-Genevois, K., Sassi, D., Verdun, S. & Roussouly, P. Sagittal classification in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: original description and therapeutic implications. Eur. Spine Journal: Official Publication Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deformity Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc.27, 2192–2202 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newton, P. O., Osborn, E. J., Bastrom, T. P., Doan, J. D. & Reighard, F. G. The 3D Sagittal Profile of thoracic versus lumbar Major curves in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deformity. 7, 60–65 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mac-Thiong, J. M., Labelle, H., Berthonnaud, E., Betz, R. R. & Roussouly, P. Sagittal spinopelvic balance in normal children and adolescents. Eur. Spine Journal: Official Publication Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deformity Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc.16, 227–234 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stokes, I. A., Sangole, A. P. & Aubin, C. E. Classification of scoliosis deformity three-dimensional spinal shape by cluster analysis. Spine34, 584–590 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, C. et al. Analysis of sagittal curvature and its influencing factors in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Medicine100, e26274 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mac-Thiong, J. M., Labelle, H., Charlebois, M., Huot, M. P. & de Guise, J. A. Sagittal plane analysis of the spine and pelvis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis according to the coronal curve type. Spine28, 1404–1409 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mak, T., Cheung, P. W. H., Zhang, T. & Cheung, J. P. Y. patterns of coronal and sagittal deformities in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.22, 44 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Busscher, I., Ploegmakers, J. J., Verkerke, G. J. & Veldhuizen, A. G. Comparative anatomical dimensions of the complete human and porcine spine. Eur. Spine Journal: Official Publication Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deformity Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc.19, 1104–1114 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eyvazov, K., Samartzis, D. & Cheung, J. P. The association of lumbar curve magnitude and spinal range of motion in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.18, 51 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okuwaki, S. et al. Associated factors and effects of coronal vertebral wedging angle in thoracic adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Orthop. Science: Official J. Japanese Orthop. Association. 29, 704–710 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo, W., Zhao, Q., Gong, C. & Zhao, P. Mechanical evaluation of range of motion of lumbar vertebrae in patientswith lumbar disc herniation before and after manipulation. Med. J. Air Force, 36, 231-233.3.03.003 (In Chinese) (2020).

- 57.Gong, C., Xie, Y., Guo, W., Wei, J. & Gui, P. J. Effects of spinal manipulation on the lumbar mobility and symmetry in 613lumbar disc herniation patients. China Dournal Traditional Chin. Med. Pharm.36, 599–601 (2021). (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.