Abstract

Background

Understanding the roots of vaccine confidence in vulnerable populations, such as persons living with HIV (PLWH), is important to facilitate vaccine uptake, thus mitigating infection and spread of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases. In an online survey of PLWH conducted in Canada during winter 2022 (AIDS and Behav 2023), we reported that the overall COVID-19 vaccination uptake rate in PLWH was similar by sex. Here, we examined attitudes and beliefs towards vaccination against COVID-19 based on sex.

Methods

Between February and May 2022, PLWH across Canada were recruited via social media and community-based organizations to complete an online survey consisting of a modified Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS) questionnaire with items from the National Advisory Committee on Immunization Acceptability Matrix. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics and responses to the VHS questionnaire by sex. The effect of biological sex on total VHS score, two subscales (“lack of confidence” and “perceived risk”) was assessed separately by linear regression adjusting for other key baseline variables.

Results

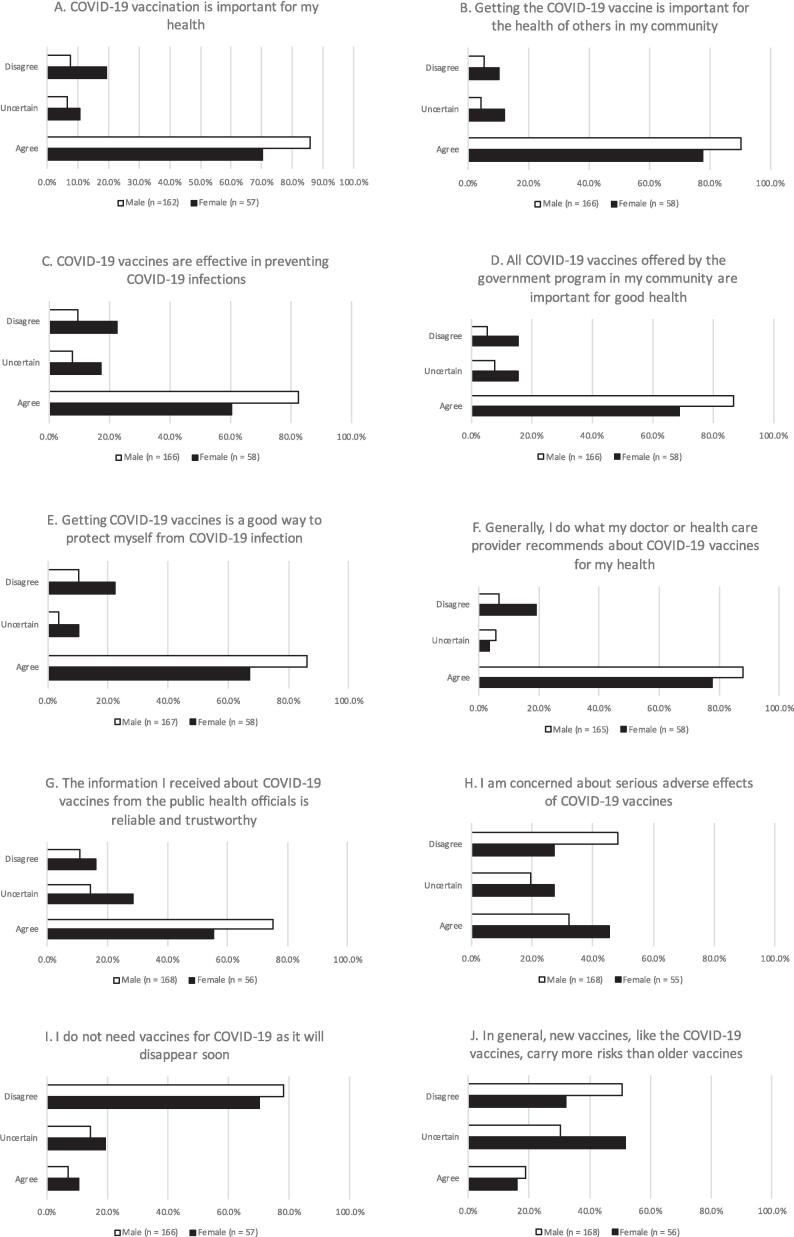

Of 259 PLWH, 69 (27 %) were females and 189 (73 %) were males. Sixty-six (26 %) of participants self-identified as a woman, 163(63 %) as a man and 28(11 %) as trans/two-spirited/queer/non-binary/agender/other. The mean age (SD) was 47 ± 14 years. Females were less likely to believe that COVID-19 vaccination was: important for his/her own health (71 % vs. 86 %); a good way to protect themselves from infection (68 % vs. 86 %); that getting the COVID-19 vaccine was important for the health of others in his/her community (78 % vs. 91 %); believed recommendations by their doctor/health care provider about COVID-19 vaccines (78 % vs. 88 %); that information about COVID-19 vaccines from public health officials was reliable and trustworthy (56 % vs. 75 % vs); COVID-19 vaccines are effective in preventing COVID-19 infections (61 % vs. 82 %) and that all COVID-19 vaccines offered by government programs in their communities were important for good health (70 % vs. 87 %). Although more males than females felt that new vaccines generally carry more risks than older vaccines (19 % vs 16 %,), fewer males than females endorsed concern about serious side effects of COVID-19 vaccines (33 % vs 45 %).

The linear regression model showed females had a significantly higher VHS total score than males (adjusted mean difference 0.38; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.13–0.64; p = 0.004), indicating greater COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among females. It was observed that females had a greater “lack of confidence in vaccines” score than males (adjusted mean difference 0.43; 95 % CI 0.14–0.73; p = 0.004). We did not observe a significant difference in “perceived risk in vaccines” between males and females (adjusted mean difference 0.20; 95 % CI −0.07–0.46; p = 0.1). The inadequate number of participants self-identifying as different from biological sex at birth prevented us from analyzing the VHS score based on gender identity.

Conclusions

Among PLWH, females showed greater COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy than males. Specifically, compared with males, females had a higher level of lack of confidence in vaccines. Fewer females than males believed that COVID-19 vaccines had health benefits at both the personal and societal levels and that recommendations made by their doctor/health care provider and public health officials are reliable and trustworthy. Further investigation into reasons for this difference in opinion still needs to be elucidated. Educational interventions targeted toward females living with HIV are especially needed to increase confidence in vaccination.

Keywords: Vaccine hesitancy, Vaccine confidence, HIV, Sex, Gender

Introduction

Approximately 67,000 people living with HIV (PLWH) reside in Canada, with women comprising nearly one-quarter of this population [1]. There are clear differences between sexes in HIV acquisition risk, the pathogenesis of untreated infection and the impact of disease treatment [2]. Furthermore, women with HIV frequently experience worse clinical outcomes than men, with higher rates of viral rebound, lower quality of care and inattention to their health and social needs [3], [4], [5], [6]. Health disparities related to sexual orientation and gender identity also exist across multiple outcomes [7].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, PLWH suffered from worse outcomes following SARS-CoV2 infection than HIV-negative individuals, and HIV was found to be an independent risk factor for severe SARS-CoV2 disease and mortality [8], [9]. A lower CD4 count in PLWH was specifically associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes [10], [11]. Worse outcomes in PLWH compared to the general population were believed to be multifactorial and ascribed to higher rates of comorbidities and other risk factors (such as higher rates of cigarette smoking, and drug and alcohol use) as well as social determinants of health [12], [13], [14].

Disparities [15] in outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic between sexes and genders underscore the importance of stratifying results based on sex. Whereas sex is a biological variable that encompasses anatomy, physiology, genetics, and hormones, gender is a sociocultural construct that stems from gender identity and expression, social and cultural expectations and behaviours associated with sex traits [16]. Biological differences were found in immune responses to infection and COVID-19 vaccination – sex-specific mechanisms, such as hormone-regulated expression of genes for the SARS-CoV2 entry receptors and adaptive immune responses, may explain more severe outcomes in older men [17]. Conversely, socially construed gender norms and disparities related to sexual orientation and gender identity could hinder access to COVID-19 prevention, testing and treatment including vaccination, through stigma, unaffordable fees or inability to travel to services [17], [18].

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccines were developed and distributed at an unprecedented speed – accompanied by vaccine hesitancy and lack of vaccine confidence. Vaccine confidence refers to positive beliefs about vaccination and knowledge and attitudes towards vaccination [19], whereas vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in accepting vaccination despite its availability [20]. Different models describe the determinants of vaccine hesitancy and/or confidence. Examples include the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Health Belief Model, the “3 C model,” and the “Working Group Determination of Vaccine Hesitancy Matrix” [20], [21], [22], [23]. Vaccine confidence and vaccine hesitancy are not singular problems but are multi-dimensional constructs impacted by intersecting factors which vary across time and communities [24], [25].

In PLWH in Canada, data on vaccine confidence based on sex and gender are relatively sparse [26]. Given the unique characteristics of PLWH, whose reasons for vaccine refusal may differ from those in the general population, we previously examined factors associated with receiving the COVID-19 vaccine and the link between vaccine attitudes and beliefs with vaccine behaviour via a web-based survey of PLWH in Canada [27]. Inclusion criteria were: 18 years of age or older, HIV positive, residing in Canada, able to provide informed consent and to complete an online survey in English or French.

Methods

Setting

In Canada, the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out began in December 2020 for adults [28], with possibility of receiving vaccines from four manufacturers (Pfizer-BioNTech Comirnaty, Moderna’s Spikevax, Astra Zeneca’s Vaxzevria and Janssen Jcovden vaccine), all approved by Health Canada [29], [30]. PLWH were not prioritized for early two-dose vaccination unless they met other priority population criteria: moderately immunocompromised, with HIV with AIDS-defining illness or severe immunocompromised with CD4 < 200 cells/µL or CD4% < 15 %, or without HIV viral suppression.

Study design, participants and recruitment strategy

A national online survey of PLWH across Canada was conducted as previously described [27]. Inclusion criteria were: 18 years of age or older, HIV positive, residing in Canada, able to provide informed consent and to complete an online survey in English or French. There were no exclusion criteria. In an attempt to ensure a representative sample [31], we aimed to recruit a minimum number of participants who identified with various group membership: men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs, women, persons of African, Caribbean or Black communities, persons of Indigenous communities and persons ≥65 years of age. Attempts to recruit participants from these sub-groups were made by advertising via social media and through community-based organizations serving PLWH and these sub-groups. The public survey link was disseminated on the community organizations’ website and directly sent to their members via e-mail, e-posters or other social media [27]. Maximum recruitment quotas for different sub-populations of PLWH were not used to capture the responses of as many participants as possible.

Study procedures

Following obtaining informed consent, screened participants completed the questionnaire online, using a secure, web-enabled survey application (REDCap), hosted on the University of British Columbia web server [27]. All data was encrypted and saved on the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network servers at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, British Columbia [27].

Questionnaire

As described previously, this study was founded on The Theory of Planned Behavior, which aims to provide a rationale for behaviors over which people can exert self-control [27], [32], [33]. A key component of this model is behavioral intent, which is influenced by the attitude about the likelihood that the intended behavior will have the expected outcome and the weighing of the risks and benefits of that outcome [27], [32], [33]. The questionnaire evaluated factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine beliefs and acceptance among PLWH. Vaccine hesitancy is generally associated with lower compliance with immunization [34]. The study questionnaire was based on instruments developed in several previous studies [35], [36], including those involving PLWH since an HIV diagnosis could modify a person’s perception of disease susceptibility and severity [37], [38], [39]. Questionnaire items included in the validated Acceptability Matrix focused on factors previously demonstrated to have the highest impact on vaccine uptake, including a) perception of vaccine safety and efficacy, b) perception of disease susceptibility and severity, c) process of vaccination and d) knowledge, attitudes and trust [40]. Furthermore, the questionnaire contains a modified Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS) for PLWH toward the COVID-19 vaccine which has acceptable reliability, internal consistency and construct validity [38]. The answer options for each question consisted of a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree), which were grouped into three categories, “agree”, “uncertain” and “disagree”. Demographic information was also collected, and variables were checked for fraudulent participants or data [27].

Modified Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS) and measures

The modified VHS includes ten items across two sub-scales, “lack of confidence in vaccines” and “perceived risk of vaccines”. Each question/item uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The full list of questions and their corresponding subscales can be found in the Appendix Table 1. For participants with valid response on all questions, we generated a VHS total score for each participant by summing responses to the ten VHS questions (with reversing scale to items in “perceived risk of vaccines” subscale- item H, I and J) and then dividing the sum by 10 to obtain the participant’s total VHS mean score. A higher VHS total score indicates greater COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Using the same approach, we also calculated the mean scores of two sub-scales for each participant: a seven-item “lack of confidence in vaccines” subscale measuring beliefs about vaccine effectiveness and its importance for health, and a three-item “perceived risk of vaccines” subscale assessing beliefs about vaccine risk and safety. A higher score on “lack of confidence in vaccines” indicates greater skepticism towards vaccines. A higher score on “perceived risk of vaccines” suggests a greater level of concern regarding the risk of vaccines. By calculating each participant’s the total VHS mean score and mean score for each of the two sub-scale, the total VHS score, the two subscale scores all ranged from 1 to 5.

Sample size

The study's sample size for the primary objective was planned to detect differences in VHS scores specifically between those accepting and refusing vaccines. Thus, the sample size of 250 participants was designed to detect a 2-point difference in total VHS score with a power of 80 % and two-tailed alpha of 5 % given a standard deviation of 4, with a ratio of accepters to refusers of 4:1, which reflects the level of vaccine uptake in the general Canadian population as of 2021 (80 %) [41]. It was reported that the ratio of males to females in the PLWH population in Canada to be closer to 3:1 [1]. Given the sample allocation. 3:1 in males vs. females, the sample of 250 will provide 90 % power, with a two-tailed alpha of 5 % to detect a 2-point difference in VHS score between males and females, assuming a standard deviation of 4. In an attempt to capture a diverse sample of PLWH in Canada, we recorded how each participant identifies with a particular group membership(s). We decided not to set quotas for specific subpopulations to allow everyone who wanted to participate the opportunity to do so.

Data analyses

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Sex differences in participant characteristics were examined using a two-sample t-test or Wilcoxon sum rank test for continuous variables and a Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data when appropriate. We also calculated the absolute standardized mean difference in participant characteristics between females and males.

Standardized mean difference in response to each VHS question between females and males was generated. The effect of sex on the VHS total score, “lack of confidence in vaccines” score and “perceived risk of vaccines” score were evaluated separately using linear regression model. All models were adjusted for age, race, household income, education level, presence of diabetes, severe asthma and injection drug use. Model assumptions were evaluated graphically by examining Quantile-Quantile plot and histogram for assessing normal distribution of residuals, linear relationship between predicted values and variables and relationship between predicted values and residuals for checking heteroscedasticity. In the present of possible heteroscedasticity, robust standard errors were applied in linear regression model to account for potential heteroscedasticity and assure more reliable findings. The adjusted mean difference in the outcome between sexes, along with its 95 % confidence intervals were reported. Furthermore, effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d, based on the adjusted mean difference estimated from the regression model.

To address missing data, we performed multiple imputation as a sensitivity analysis. The multiple imputation was conducted using chained equations with 50 iterations.

Two-sided p-values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. It was suggested Cohen’s d can be classified as trivial (values of 0 to 0.19), small (0.20 to 0.49), medium (0.50 to 0.79) or large (0.80 or higher). All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Ethics

This study was conducted according to the Tri-Council Policy Statement Version 2 (TCPS2) and the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was received from the University of British Columbia Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board (H21-03432).

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting files.

Results

Baseline characteristics by biological sex

As previously reported, 259 individuals participated in the online survey. A total of 246 indicated whether they were vaccinated, of whom 89 % reported receiving at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. The mean age (±standard deviation) was 47 ± 14 years. Sixty-nine (27 %) were females and 189 (73 %) were males. Sixty-six (26 %) of participants self-identified as women, 163(63 %) as a man and 28(11 %) as trans/two-spirited/queer/non-binary/agender/other. Two participants refused to self-identify. Ninety-three percent of females self-identified as women and 86 % of males self-identified as men. Participant demographics by sex, are presented in Table 1. Females and males were similar in employment status, born in Canada, years of HIV diagnosis, vaping history, and comorbid conditions in hepatitis C, kidney failure, chronic liver disease and chronic lung disease. However, female participants were younger (43 ± 14 vs. 48 ± 14 years old; absolute standardized mean difference (ASMD) 0.42), less likely to obtain at least some college education (67 % vs. 80 %; ASMD 0.46), more than half were Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) (57 % vs. 41 %; ASMD 0.33) and more current smokers (35 % vs. 19 %; ASMD = 0.44). The reported total household income was lower in females ($29,999 under, 48 % vs. 29 %; ASMD 0.65). Regarding comorbidities, diabetes and severe asthma were more prevalent in female participants (24 % vs. 12 %; ASMD 0.31; 19 % vs. 4 %; ASMD 0.50).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by sex.

| Characteristic |

Female (n = 69) |

Male (n = 189) |

P-value | Absolute standardized mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), year | 42.6 (14.0) | 48.3 (13.7) | 0.003 | 0.42 |

| Highest education level | 0.01 | 0.46 | ||

| Less than HS | 4 (5.8) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Some/completed HS | 19 (27.5) | 36 (19.1) | ||

| Some/completed university | 39 (56.5) | 111 (59.0) | ||

| Some/completed graduate education | 7 (10.1) | 40 (21.3) | ||

| (Missing) | 0 | 1 | ||

| Total household income | 0.002 | 0.65 | ||

| $29,999 under | 30 (47.6) | 53 (29.4) | ||

| $30,000–$59,999 | 23 (36.5) | 54 (30.0) | ||

| $60,000-$89,999 | 7 (11.1) | 29 (16.1) | ||

| $90,000 and up | 3 (4.8) | 44 (24.4) | ||

| (Missing) | 6 | 9 | ||

| Current employment status | 0.69 | 0.06 | ||

| Employed | 35 (53.0) | 104 (55.9) | ||

| (Missing) | 3 | 3 | ||

| Born in Canada | 0.32 | 0.14 | ||

| Yes | 47 (70.1) | 118 (63.4) | ||

| (Missing) | 2 | 3 | ||

| Inject drugs user | 8 (11.6) | 9 (4.8) | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Non-prescription illicit drug user | 4 (5.8) | 27 (14.3) | 0.06 | 0.29 |

| Gender | <0.0001 | 5.70 | ||

| Woman | 64 (92.8) | 2 (1.1) | ||

| Man | 1 (1.4) | 162 (86.2) | ||

| Transgender | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | ||

| Two-spirit | 1 (1.4) | 8 (4.3) | ||

| Queer | 1 (1.4) | 11 (5.9) | ||

| Non-binary | 1 (1.4) | 3 (1.6) | ||

| Agender | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 1 (1.4) | 1 | ||

| (Missing) | 0 | 1 | ||

| MSM | <0.0001 | 2.95 | ||

| Yes | 3(4.4) | 164 (86.8) | ||

| (Missing) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 0.02 | 0.33 | ||

| White | 29 (42.6) | 110 (59.1) | ||

| BIPOC | 39 (57.4) | 76 (40.9) | ||

| (Missing) | 1 | 3 | ||

| Ethnicity subgroup | ||||

| African, Caribbean or Black community | 14 (20.3) | 16 (8.5) | 0.01 | 0.34 |

| Indigenous | 9 (13.0) | 3 (1.6) | 0.001 | 0.45 |

| Migrant | 3 (4.3) | 10 (5.3) | 1.00 | 0.04 |

| Received HIV diagnosis | 0.28 | 0.28 | ||

| 4 years ago and less | 14 (21.5) | 24 (13.0) | ||

| 5–9 years ago | 11 (16.9) | 26 (14.1) | ||

| 10–14 years ago | 8 (12.3) | 33 (17.8) | ||

| 15 years ago or more | 32 (49.2) | 102 (55.1) | ||

| (Missing) | 4 | 4 | ||

| On ARV | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 67 (98.5) | 186 (98.4) | ||

| (Missing) | 1 | 0 | ||

| Hepatitis C | 0.36 | 0.12 | ||

| Yes | 5 (7.7) | 9 (4.8) | ||

| (Missing) | 4 | 1 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.02 | 0.31 | ||

| Yes | 16 (23.5) | 22 (11.9) | ||

| (Missing) | 1 | 4 | ||

| Kidney failure | 0.21 | 0.19 | ||

| Yes | 6 (9.0) | 8 (4.3) | ||

| (Missing) | 2 | 4 | ||

| Chronic liver disease | 1.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 4 (6.2) | 11 (5.9) | ||

| (Missing) | 4 | 3 | ||

| Chronic lung disease | 0.39 | 0.12 | ||

| Yes | 6 (9.1) | 11 (5.9) | ||

| (Missing) | 3 | 2 | ||

| Severe asthma | <0.0001 | 0.50 | ||

| Yes | 13 (19.4) | 7 (3.8) | ||

| (Missing) | 2 | 3 | ||

| Smoking | 0.01 | 0.44 | ||

| Yes | 23 (34.8) | 34 (18.5) | ||

| Not currently/in the past | 17 (25.8) | 79 (42.9) | ||

| Never | 26 (39.4) | 71 (38.6) | ||

| (Missing) | 3 | 5 | ||

| Vaping | 0.06 | 0.33 | ||

| Yes | 6 (9.2) | 26 (14.1) | ||

| Not currently/in the past | 15 (23.1) | 21 (11.4) | ||

| Never | 44 (67.7) | 138 (74.6) | ||

| (Missing) | 4 | 4 | ||

| Smoking cannabis | 0.38 | 0.20 | ||

| Yes | 15 (23.4) | 50 (27.5) | ||

| Not currently but in the past | 18 (28.1) | 62 (34.1) | ||

| Never | 31 (48.4) | 70 (38.5) | ||

| (Missing) | 5 | 7 | ||

| Consumption of cannabis or cannabinoid-based products (form other than smoking) | 0.58 | 0.15 | ||

| Yes | 13 (20.0) | 45 (24.6) | ||

| Not currently/in the past | 19 (29.2) | 43 (23.5) | ||

| Never | 33 (50.8) | 95 (51.9) | ||

| (Missing) | 4 | 6 |

Vaccine Hesitancy Scale, confidence and perceived risk in COVID-19 vaccine by sex

Responses to VHS questionnaire for male and female participants are shown in Fig. 1. More females than males were less likely to believe: A) COVID-19 vaccination was important for his/her own health (standardized mean difference of VHS in scale of 1 to 5 (SMD-VHS) 0.43; 71 % vs. 86 % agree; 10 % vs. 7 % uncertain); B) getting the COVID-19 vaccine is important for the health of others in the community (SMD-VHS 0.45; 78 % vs. 91 % agree; 12 % vs. 4 % uncertain); C) COVID-19 vaccines are effective in preventing COVID-19 infections (SMD-VHS 0.50; 61 % vs. 82 % agree; 17 % vs. 9 % uncertain); D) all COVID-19 vaccines offered by government programs in the community are important for good health (SMD-VHS 0.47; 70 % vs. 87 % agree; 15 % vs.8 uncertain); E) getting COVID vaccines is a good way to protect themselves from infection (SMD-VHS 0.40; 68 % vs. 86 % agree; 10 % vs. 4 % uncertain); F) recommendations by their doctor/health care provider about COVID-19 vaccines (SMD-VHS 0.40; 78 % vs. 88 % agree; 3 % vs. 5 % uncertain); and G) information about COVID-19 vaccines from public health officials was reliable and trustworthy (SMD-VHS 0.29; 56 % vs. 75 % agree; 28 % vs. 14 % uncertain). Fewer males than females endorsed concern about serious side effects of COVID-19 vaccines (H: SMD-VHS 0.40; 33 % vs 45 % agree; 19 % vs. 27 % uncertain). Few males than females agreed they don’t need vaccines for COVID-19 as it will disappear soon (I: SMD-VHS 0.35; 8 % vs. 10 % agree; 15 % vs. 19 % uncertain), Slightly more males than females felt that new vaccines generally carry more risks than older vaccines (SMD-VHS 0.12; J: 19 % vs 16 % agree; 30 % vs. 53 % uncertain), Additionally, fewer males than females endorsed concern about the serious side effects of COVID-19 vaccines.

Fig. 1.

A–J Overall patterns of vaccine hesitancy across the two groups based on the sex of participants. For each question, the percentage of all female and all male responders is presented. To enhance visualization, five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) are grouped into three categories, “agree”, “uncertain” and “disagree”.

Female participants had higher VHS total scores than male participants (2.30 ± 0.98 vs. 1.81 ± 0.71). The linear regression model showed the adjusted mean difference in VHS total score between females and males was 0.38; 95 % confidence interval (CI) [0.07, 0.70]; p = 0.02, Cohen’s d 0.49; indicating COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was significantly greater in females with a small effect size (Table 2). For the sub-scale of “lack of confidence in vaccine”, the results of the linear regression model indicated females had statistically significantly higher “lack of confidence in vaccines” scores than males with a small effect size (2.14 ± 1.15 vs. 1.60 ± 0.80; adjusted mean difference 0.43; 95 % CI [0.07, 0.80]; p = 0.02; Cohen’s d 0.48). No statistically significant difference was observed between males and females on “perceived risk in vaccines” (2.67 ± 0.78 vs. 2.32 ± 0.86; adjusted mean difference 0.20; 95 % CI [−0.08, 0.47]; p = 0.16; Cohen’s d 0.23). We reached the same conclusions based on the results from multiple imputation (Table S2).

Table 2.

Results of linear regression model for VHS total score and two sub-scales.

| Adjusted mean difference and 95 % CI (Females vs. Males) |

p-value | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VHS total score | 0.38 [ 0.07, 0.70] | 0.02 | 0.49 |

| “Lack of confidence in vaccines” score | 0.43 [0.07, 0.80] | 0.02 | 0.48 |

| “Perceived risk of vaccines” score | 0.20 [−0.08, 0.47] | 0.16 | 0.23 |

Discussion

The gender and sex differences in COVID-19 vaccination intentions in our study echo findings in the current literature. Vaccination intentions in several countries differed between genders, with a lower rate among women than men [42]. To our knowledge, the only other studies conducted on vaccine uptake in PLWH living in Canada showed that intention to vaccinate was significantly lower among women and gender-diverse populations living with HIV compared to participants not living with HIV, and that males and females living with HIV had similar uptake of two doses but males were more likely to receive three or more doses [26], [43]. Therefore, an increase in sex and gender-specific information is prudent to address misconceptions and mitigate vaccine hesitancy in subgroups with lower vaccination intention rates, including PLWH.

In our study, we found that females had greater COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy than males. Specifically, compared with males, females showed a higher level of lack of confidence in COVID-19 vaccines. Fewer females than males believed that COVID-19 vaccination was important for their health and that getting COVID-19 vaccines was a good way to protect themselves from COVID-19 infection. Similarly, less females than males believed that getting the COVID-19 vaccine was important for the health of others in their community. Despite the discrepancy in vaccine attitudes between sexes, as of June 30th, 2024, 82.5 % females have received at least 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, while 79.5 % males have [44]. The beliefs highlighted in our study did not reflect in vaccine uptake, suggesting that females accepted to receive the vaccine even if they did not have full confidence in its benefits. Historically, however, men have been found to have higher vaccination rates than women in the case of influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis [12], [45], [46], [47].

Cenat et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis examining the prevalence and factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and vaccine unwillingness in Canada [48]. Overall, vaccine unwillingness was reported to be higher in females compared with males, non-White individuals than white individuals, in rural compared with urban areas, and in secondary or less post-secondary education. These trends reflect similar dynamics found in other countries, such as the United States [48].

Results on VHS according to sex indicated that females were more hesitant than males in five studies, but in three studies, researchers found no sex differences [48]. Additionally, the majority of studies reported vaccine hesitancy was related to younger age, but two found no significant age differences [48]. Beyond sex and gender, the literature underscores the importance of other frequent determining factors of vaccine receptivity, which include education level, area of living, and age. Even when corrected for these factors we still found the greater hesitancy toward the vaccine among female participants in our study. [49]

Trust is an important element in eliciting confidence in vaccinations or other health recommendations. Maximum vaccine coverage can be achieved by building trust in the government and medical services and determining the roots of vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy in the Black community has been explained by pre-existing disparities with health care professionals, unavailability of health care services and underrepresentation in clinical trials [48]. We found that more males than females believed that all COVID-19 vaccines offered by the government program in their communities were important for good health and what their doctor or health care provider recommended about COVID-19 vaccines for their health. Furthermore, more males than females believed the information they received about COVID-19 vaccines from public health officials was reliable and trustworthy. Maximum vaccine coverage can therefore be achieved by building trust in the government and medical services and determining the roots of vaccine hesitancy [25].

Globally, the most common reason for vaccine hesitation is concern over side effects – and this was especially true early in the pandemic and gradually declined as time went on [50]. Although we did not specifically address concerns related to fertility and infant malformation, they have been put forth as a reason to explain higher rates of vaccine hesitancy in women than men [51], [52]. Slightly more males than females felt, in general, that newer vaccines carry more risks than older vaccines. Additionally, fewer males than females endorsed concern about the serious side effects of COVID-19 vaccines. This theory has caused many young women of childbearing age to hesitate about vaccination and to consider not being vaccinated. A systematic review of a sample of 700,000 pregnant women found a low rate of vaccination among them compared with the rest of the population [53].

The sex differences in COVID-19 vaccination intentions found in the literature as well as in our study may reflect social norms and gender roles in society, and these trends in vaccine intention could further perpetuate gender dynamics. Particularly in the context of HIV epidemiology, taking into account the sex/gender of PLWH is essential because traditional gender roles may impact adherence to ART [12], [54], [55]. Women are often caregivers and may not prioritize their medical care, thereby rendering them and their respective care receivers more vulnerable to developing health problems, such as COVID-19 infection [42], [56]. As such, reduced vaccination intention poses a problem in the mitigation of the spread. In a previous study by Zintel et al., differences in vaccination intentions between genders seem to be more significant in samples of healthcare workers than in unspecific population samples, further underscoring the need to address the barriers to vaccination [42]. Similarly, in Butter et al., COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was associated with being female only for key workers – that is, individuals employed in positions in health care, education and childcare or positions crucial for providing food, necessities and utilities [57]. Despite the significance of this finding, this correlation may be misleading, as it could be due to unbalanced gender representation in these fields.

Factors associated with vaccine hesitancy are vastly different before and after the availability of vaccines. Before the roll-out in mid-December 2020, major concerns across all the population groups were focused on the vaccine's safety, effectiveness and cost [12], [58], [59]. As the death toll peaked in the US and with more publicly available data on vaccine trials, there was a considerable trend shift in the attitudes towards receiving a vaccination [60]. Over time, two studies investigated changes in COVID-19 vaccine acceptance by surveying the population twice [61], [62]. Daly et al. conducted the first round of the survey in October 2020 and the second round in March 2021, and Szilagy et al. surveyed participants in November-December 2020 and in April 2021 [61], [62]. These two studies observed respective increases of 10.8 % and 7.9 % in vaccine acceptance between 2020 and 2021 [61], [62]. While an overall change in readiness for uptake of the vaccine was notable across several studies, the predictors of hesitance remained the same throughout time. African/American Blacks and females were the leading predictors of low acceptance in both studies [61], [62]. Our study took place in the second part of the vaccine rollout, but we have no comparison to the evolution of vaccine confidence over time.

In a scoping review on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community and factors fostering its refusal, the major comparative status was HIV status, with PLWH more likely to take up COVID-19 vaccine [63]. Our study did not fully address confidence in transgender as the number of participants that belongs to these groups was small.

Limitations

The extent of the literature on COVID-19 vaccination uptake among PLWH remains quite limited; most studies are still based in the US. While trends specific to the US typically resemble those in Canada, data specific to Canada remains limited, and the present study therefore has few prior studies to which it can compare. Likewise, in our study, the number of agender/transgender/two-spirit participants may be too insufficient to derive conclusive findings, which may limit the findings of our study.

Furthermore, as highlighted by the literature and our study, vaccine hesitation is multifactorial and multi-dimensional. Confounding micro-level, macro-level and meso-level factors, including age, race/ethnicity and sexual orientation, must be further examined to fully grasp vaccination hesitancy among different subgroups and develop tailored interventions to mitigate it. Multiple studies seem to indicate that factors other than sex and gender influence vaccination willingness. As such, to promote the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccination as well as other vaccinations, more studies on the intersectional elements of vaccine hesitancy are required.

In the same vein, spectrum bias may skew our findings and explain certain discrepancies between our study and the literature. Indeed, systematic reviews pool multitudes of populations, and analyses of percentages are subjected to spectrum bias, since percentages for general populations are pooled with terminally ill or marginalized groups. Vaccine acceptability is thus liable to random error, as published studies were carried out at different phases of the coronavirus peak [25]. Given the sampling approach in this study, selection bias, as well as volunteer bias, are also pertinent limitations to our findings.

Since participants completed the survey anonymously, the questionnaire did not include any questions pertaining to HIV-related immunologic parameters to consider, as not all participants would know these values. Our findings were thus limited because viro-immunological status has been associated with quality of life in PLWH and thus could potentially have an impact on behaviour, which we did not analyze in our study.

Conclusions

Among PLWH, females had greater COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy than males. Specifically, females showed a higher level of lack of confidence in COVID-19 vaccines. Fewer females than males believed that COVID-19 vaccines had health benefits at both the personal and societal level and that recommendations made by their doctor/health care provider and public health officials are reliable and trustworthy. Educational interventions targeted toward females living with HIV are especially needed to increase confidence in vaccination. Contemplation about methods to transfer these findings to promote the uptake of influenza and other vaccinations is merited.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jessica Lu: Writing – original draft, Visualization. Branka Vulesevic: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Ann N. Burchell: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Joel Singer: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. Judy Needham: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. Yanbo Yang: Conceptualization. Hong Qian: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Catharine Chambers: Writing – review & editing. Hasina Samji: Writing – review & editing. Ines Colmegna: Data curation. Sugandhi del Canto: Data curation. Guy-Henri Godin: Writing – review & editing. Muluba Habanyama: Conceptualization. Sze Shing Christian Hui: Conceptualization. Abigail Kroch: Conceptualization. Enrico Mandarino: Conceptualization. Shari Margolese: Conceptualization. Carrie Martin: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Maureen Owino: Conceptualization. Elisa Lau: Formal analysis, Data curation. Tima Mohammadi: Data curation. Wei Zhang: Data curation. Sandra Pelaez: Data curation. Colin Kovacs: Data curation. Erika Benko: Data curation. Curtis L. Cooper: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Aslam H. Anis: Conceptualization. Cecilia T. Costiniuk: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvacx.2024.100566.

Contributor Information

Branka Vulesevic, Email: bvule091@uottawa.ca.

Ann N. Burchell, Email: ann.burchell@unityhealth.to.

Joel Singer, Email: jsinger@hivnet.ubc.ca.

Judy Needham, Email: jneedham@advancinghealth.ubc.ca.

Yanbo Yang, Email: yanbo.yang@mail.mcgill.ca.

Hong Qian, Email: hqian@advancinghealth.ubc.ca.

Catharine Chambers, Email: catharine.chambers@mail.utoronto.ca.

Hasina Samji, Email: hasina.samji@bccdc.ca.

Ines Colmegna, Email: ines.colmegna.med@ssss.gouv.qc.ca.

Sugandhi del Canto, Email: sdcanto@catie.ca.

Guy-Henri Godin, Email: guy-henri.godin@sympatico.ca.

Sze Shing Christian Hui, Email: c6hui@torontomu.ca.

Abigail Kroch, Email: abigail.kroch@utoronto.ca.

Enrico Mandarino, Email: emandarino@rogers.com.

Carrie Martin, Email: carrie@ihct.ca.

Elisa Lau, Email: elau@advancinghealth.ubc.ca.

Wei Zhang, Email: wzhang@advancinghealth.ubc.ca.

Sandra Pelaez, Email: sandra.pelaez@umontreal.ca.

Colin Kovacs, Email: ckovacs@mlmedical.com.

Erika Benko, Email: ebenko@mlmedical.com.

Curtis L. Cooper, Email: ccooper@toh.ca.

Aslam H. Anis, Email: aslam.anis@ubc.ca.

Cecilia T. Costiniuk, Email: cecilia.costiniuk@mcgill.ca.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Canada PHAo. Estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada’s progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets, 2020. 2020.

- 2.Altfeld M., Scully E.P. Sex differences in HIV infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2023;441:61–73. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-35139-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mrus J.M., Williams P.L., Tsevat J., Cohn S.E., Wu A.W. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients with HIV/AIDS. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(2):479–491. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-4693-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter A., Greene S., Nicholson V., et al. Breaking the glass ceiling: increasing the meaningful involvement of women living with HIV/AIDS (MIWA) in the design and delivery of HIV/AIDS services. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(8):936–964. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.954703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirschhorn L.R., McInnes K., Landon B.E., et al. Gender differences in quality of HIV care in Ryan White CARE Act-funded clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16(3):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loutfy M., de Pokomandy A., Kennedy V.L., et al. Cohort profile: The Canadian HIV Women's Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatzenbuehler M.L., Lattanner M.R., McKetta S., Pachankis J.E. Structural stigma and LGBTQ+ health: a narrative review of quantitative studies. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9(2):e109–e127. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertagnolio S., Thwin S.S., Silva R., et al. Clinical features of, and risk factors for, severe or fatal COVID-19 among people living with HIV admitted to hospital: analysis of data from the WHO Global Clinical Platform of COVID-19. Lancet HIV. 2022;9(7):e486–e495. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00097-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ssentongo P, Heilbrunn ES, Ssentongo AE, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Giacomelli A., Gagliardini R., Tavelli A., et al. Risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in people living with HIV compared to general population according to age and CD4 strata: data from the ICONA network. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;136:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X., Sun J., Patel R.C., et al. Associations between HIV infection and clinical spectrum of COVID-19: a population level analysis based on US National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) data. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(11):e690–e700. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrams E.M., Szefler S.J. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):659–661. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almomen A., Cox J., Lebouche B., et al. Short Communication: Ongoing impact of the social determinants of health during the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in people living with HIV receiving care in a Montreal-based Tertiary Care Center. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2022;38(5):359–362. doi: 10.1089/AID.2021.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fehr D., Lebouche B., Ruppenthal L., et al. Characterization of people living with HIV in a Montreal-based tertiary care center with COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic. AIDS Care. 2022;34(5):663–669. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2021.1904500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Europe Co. Sex and gender. 2024; https://www.coe.int/en/web/gender-matters/sex-and-gender#:∼:text=Sex%20refers%20to%20%E2%80%9Cthe%20different,groups%20of%20women%20and%20men. Accessed 5 May, 2024.

- 16.Health NOoRoWs. What are Sex & Gender? Sex Gender 2024; https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender. Accessed 25 April, 2024.

- 17.Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Rafique Z., Durkalski-Mauldin V., Peacock W.F., Yadav K., Reynolds J.C., Callaway C.W. Sex-specific disparities in COVID-19 outcomes. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. Feb 2024;5(1):e13110. doi: 10.1002/emp2.13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betsch C., Schmid P., Heinemeier D., Korn L., Holtmann C., Bohm R. Beyond confidence: development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald N.E., Hesitancy SWGoV Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troiano G., Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health. 2021;194:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams S.E. What are the factors that contribute to parental vaccine-hesitancy and what can we do about it? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(9):2584–2596. doi: 10.4161/hv.28596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dube E., Gagnon D., Nickels E., Jeram S., Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy–country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014;32(49):6649–6654. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham R.M., Minard C.G., Guffey D., Swaim L.S., Opel D.J., Boom J.A. Prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among expectant mothers in Houston, Texas. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasmin F., Najeeb H., Moeed A., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United States: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.770985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaida A, Brotto LA, Murray MCM, et al. Intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine by HIV status among a population-based sample of women and gender diverse individuals in British Columbia, Canada. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(7):2242-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Costiniuk C.T., Singer J., Needham J., et al. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine confidence in people living with HIV: a pan-Canadian survey. AIDS Behav. 2023;27(8):2669–2680. doi: 10.1007/s10461-023-03991-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/document/servicces/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-response/canadas-covid-19-vaccines-been-tested-people-hiv Accessed 1 April 2022 PHAoCCsC-ipSlal.

- 29.https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisorry-committee-on-immunization-naci/recommendations-use-covid-19-vaccines html NACoIRotuoC-vAJ.

- 30.Canada Go. COVID-19 vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide. 2024.

- 31.Public Health Agency of Canada Estimates of HIV incidence paCspomt--Ht, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-canadas-progress-90-90-90.html#s2, 2021 AA.

- 32.Wolff K. COVID-19 vaccination intentions: the theory of planned behavior, optimistic bias, and anticipated regret. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosnjak M., Ajzen I., Schmidt P. The theory of planned behavior: selected recent advances and applications. Eur J Psychol. 2020;16(3):352–356. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlsson L.C., Lewandowsky S., Antfolk J., et al. The association between vaccination confidence, vaccination behavior, and willingness to recommend vaccines among Finnish healthcare workers. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0224330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larson H.J., Jarrett C., Eckersberger E., Smith D.M., Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson H.J., de Figueiredo A., Xiahong Z., et al. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Govere-Hwenje S, Jarolimova J, Yan J, et al. Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination among people living with HIV in a high HIV prevalence community. Res Sq. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Rodriguez V.J., Alcaide M.L., Salazar A.S., Montgomerie E.K., Maddalon M.J., Jones D.L. Psychometric properties of a vaccine hesitancy scale adapted for COVID-19 vaccination among people with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(1):96–101. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallee A, Fourn E, Majerholc C, Touche P, Zucman D. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy among French people living with HIV. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Ismail S.J., Hardy K., Tunis M.C., Young K., Sicard N., Quach C. A framework for the systematic consideration of ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability in vaccine program recommendations. Vaccine. 2020;38(36):5861–5876. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canada S. Majority of Canadians are willing to get a COVID-19 booster dose. 2022.

- 42.Zintel S, Flock C, Arbogast AL, Forster A, von Wagner C, Sieverding M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2022:1-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Freitas C, Chambers C, Cooper CL, Kroch AE, Buchan SA, Kendall CE, et al. Uptake of 3+ COVID-10 Vaccine doses among people living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Denver, Colorado2024.

- 44.Canada Go. COVID-19 vaccination: Vaccination coverage. 2024; https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccination-coverage/archive/2023-12-18/index.html. Accessed 31 Aug, 2024.

- 45.Bish A., Yardley L., Nicoll A., Michie S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6472–6484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pulcini C., Massin S., Launay O., Verger P. Factors associated with vaccination for hepatitis B, pertussis, seasonal and pandemic influenza among French general practitioners: a 2010 survey. Vaccine. 2013;31(37):3943–3949. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flanagan K.L., Fink A.L., Plebanski M., Klein S.L. Sex and gender differences in the outcomes of vaccination over the life course. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2017;33:577–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cenat J.M., Noorishad P.G., Moshirian Farahi S.M.M., et al. Prevalence and factors related to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and unwillingness in Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2023;95(1):e28156. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S.C., Palayew A., et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ekstrand M.L., Heylen E., Gandhi M., Steward W.T., Pereira M., Srinivasan K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among PLWH in South India: implications for vaccination campaigns. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;88(5):421–425. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikpour M., Sepidarkish M., Omidvar S., Firouzbakht M. Global prevalence of acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines and associated factors in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(6):843–851. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2022.2053677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaler L., Wingfield M. COVID-19 vaccine - can it affect fertility? Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191(5):2185–2187. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galanis P, Vraka I, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, Katsiroumpa A, Kaitelidou D. Uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Tapp C., Milloy M.J., Kerr T., et al. Female gender predicts lower access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a setting of free healthcare. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puskas C.M., Forrest J.I., Parashar S., et al. Women and vulnerability to HAART non-adherence: a literature review of treatment adherence by gender from 2000 to 2011. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):277–287. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Durvasula R. HIV/AIDS in older women: unique challenges, unmet needs. Behav Med. 2014;40(3):85–98. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2014.893983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butter S., McGlinchey E., Berry E., Armour C. Psychological, social, and situational factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions: a study of UK key workers and non-key workers. Br J Health Psychol. 2022;27(1):13–29. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gatwood J., McKnight M., Fiscus M., Hohmeier K.C., Chisholm-Burns M. Factors influencing likelihood of COVID-19 vaccination: A survey of Tennessee adults. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(10):879–889. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxab099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher K.A., Bloomstone S.J., Walder J., Crawford S., Fouayzi H., Mazor K.M. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):964–973. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson HS, Manning M, Mitchell J, et al. Factors associated with racial/ethnic group-based medical mistrust and perspectives on COVID-19 vaccine trial participation and vaccine uptake in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2111629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Daly M., Jones A., Robinson E. Public trust and willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in the US from October 14, 2020, to March 29, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325(23):2397–2399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.8246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szilagyi P.G., Thomas K., Shah M.D., et al. National trends in the US public's likelihood of getting a COVID-19 vaccine-April 1 to December 8, 2020. JAMA. 2020;325(4):396–398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balaji J.N., Prakash S., Joshi A., Surapaneni K.M. A scoping review on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community and factors fostering its refusal. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11(2) doi: 10.3390/healthcare11020245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting files.

Data will be made available on request.