Abstract

Introduction

Canadian Family Medicine (FM) residents, upon graduation, are disinclined to provide intrapartum care. The FM resident experience with obstetrical training has not been studied in over a decade while the FM landscape has changed. This study explored the FM resident experience in working towards their obstetrical competencies as one of the chief influences on their career decision to provide intrapartum care or not.

Methods

Using a qualitative descriptive design, we conducted semi-structured interviews with second-year FM residents (n = 7) and obstetrical supervisors (n = 8) from one Ontario FM program. We coded and interpreted the transcripts for common themes.

Results

FM residents working towards their intrapartum skills are influenced by the following themes: the learners’ unique and individual experience and expectations; opportunities in the training environment; and learning obstetrics in the changing FM landscape. Notably, the influence of FM maternity care role models permeated all themes.

Conclusion

This study offers insight into potential areas of intervention to improve the FM residency training experience in intrapartum care. Investment in FM maternity education, in the undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula, with continued support in practice, is critical to maintain comprehensive education and patient care, especially while Canada faces a maternity care crisis.

Abstract

Introduction

Les résidents canadiens en médecine familiale (MF), une fois diplômés, sont peu enclins à prodiguer des soins intrapartum. L'expérience des résidents en MF en matière de formation obstétricale n'a pas été étudiée depuis plus d'une décennie, alors que le contexte de la MF a changé. Cette étude a exploré l'expérience des résidents en MF dans l'acquisition de leurs compétences obstétricales comme l'une des principales influences sur leur décision de carrière de fournir ou non des soins intrapartum.

Méthodes

À l'aide d'un plan descriptif qualitatif, nous avons mené des entrevues semi-structurées avec des résidents en MF de deuxième année (n = 7) et des superviseurs en obstétrique (n = 8) d'un programme de MF en Ontario. Nous avons codé et interprété les transcriptions pour trouver des thèmes communs.

Résultats

Les résidents en MF qui travaillent à l'acquisition de compétences intrapartum sont influencés par les thèmes suivants : l'expérience et les attentes uniques et individuelles des apprenants, les possibilités offertes par le milieu de formation et l'apprentissage de l'obstétrique dans le contexte en pleine évolution de la MF. L'influence des modèles de soins de maternité en MF a notamment été omniprésente dans tous les thèmes.

Conclusion

Cette étude offre un aperçu des domaines d'intervention potentiels pour améliorer l'expérience de formation en soins intrapartum au cours d’une résidence en MF. Investir dans la formation en matière de maternité en médecine familiale, dans les programmes d'études médicales de premier et de deuxième cycle, avec un soutien continu dans la pratique, est essentiel pour maintenir une formation complète et les soins aux patients, particulièrement au moment où le Canada est confronté à une crise sur le plan des soins de maternité.

Introduction

The number of Family Medicine (FM) maternity care providers has been declining,1,2 contributing to a crisis in Canada’s maternity care provision.3 The decline in family physicians practicing obstetrics is a well-documented, multi-factorial concern that includes increased liability, remuneration issues, discouraging hospital policies, emotional consequences of poor outcomes, and work-life balance.2 Residents are disinclined to include maternity care in practice, and many who plan to include it change their mind.4,5 This is attributed to feeling unprepared after residency, leading to additional training.4–8 Maternal and newborn care, including management of low-risk labour and delivery is required of FM residents and is a core professional activity within the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) Residency Training Profile.9,10 In this paper, provision of maternity care specifically includes intrapartum care. To better understand how FM residency training programs can improve training in intrapartum care, it is important to know what factors influence the resident attainment of obstetrical competency. Except for Koppula et al.’s study in 2009 looking at the resident experience in a unique primary care obstetrics rotation,11 most research exploring the Canadian FM resident experience with maternity care training occurred in the 1990s.4,12–16 There is a gap in the literature exploring resident perspectives more recently while FM has changed. Research suggests that the shift of family physicians towards focused practice may be due to the overwhelming breadth of comprehensive practice in an undesirable work environment as opposed to the intellectual challenge and better remuneration in focused practice.17 The purpose of this study was to describe the FM resident experience in working towards obstetrical competency as a key influence of their career decision as to whether or not to provide intrapartum care. Specifically, the research question was: What are the resident and supervisor perspectives on the factors influencing resident attainment of obstetrical competency in their training environment?

Methods

Study design

We chose qualitative descriptive methodology to garner descriptions of the participant experience.18

Setting and participants

The researchers conducted this study at an Ontario FM residency program where residents are in urban, regional, and rural training centres. Residents have at least two months of obstetrics and gynecology with obstetricians and need to experience at least three deliveries with family doctors, which included observation only or attending any part of the labour regardless of outcome.19

We recruited participants by purposive sampling: second-year FM residents and their supervisors. We contacted two cohorts of FM residents, (approximately 170), selected to ensure sufficient experiences in the training environment. We contacted FM maternity care providers and obstetrical supervisors from six centers affiliated with the residents’ training institution by email and social media. As these physicians worked directly with residents, we expected that they would offer an important perspective.

We interviewed all eligible participants who provided written informed consent. The interview guide is found in Appendix A.

Data collection

Between September 2020 and January 2022, NA conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews on Zoom, which were audiotaped and professionally transcribed verbatim. Western University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board and Lawson Health Research Institute provided ethical approval.

Data analysis

The investigators independently noted key phrases within the transcripts, then collectively identified themes via thematic analysis.18 The researchers revised a coding template with subsequent interviews in an iterative fashion over several meetings.18 The researchers determined that they had sufficient data when they no longer generated new codes even after extending the demographics of the purposive sample, reaching informational redundancy.20,21

Variation in the researchers’ background and reflexivity, helped to mitigate interpretation bias.22–24 NA is a FM maternity care provider and educator, though was not supervising at the institution under study at the time. SK is a family physician educator with maternity care experience and JBB is an experienced academic qualitative researcher with a social work background. Throughout the study, the researchers acknowledged how their experiences, roles, and biases may have influenced the coding and data analysis.

Results

The final sample is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Residents | Supervisors | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 6 | 7 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 26–30 | 7 | 1 |

| 31–45 | 0 | 5 |

| 45–60 | 0 | 1 |

| ≥60 | 0 | 1 |

| Location | ||

| Urban, academic | 2 | 5 |

| Urban, not academic | 1 | 1 |

| Suburban/regional | 2 | 1 |

| Rural | 2 | 1 |

| Years in Practice | ||

| ≤ 5 | 5 | |

| 6–15 | 2 | |

| >15 | 1 | |

| Specialty | ||

| Family Medicine | 5 | |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 3 |

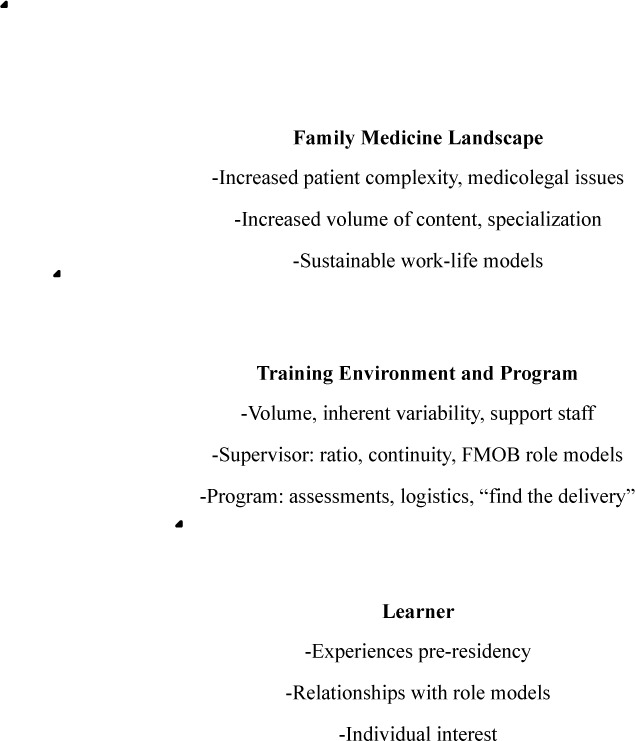

We understood factors influencing residents’ experiences working towards obstetrical competency through three themes (Figure 1). These were the learners’ individual experience and expectations; opportunities in the training environment; and learning obstetrics in the changing FM landscape. The FM maternity care role model influence permeated all themes.

Figure 1.

Factors impacting FM resident obstetrical training experience

The learner’s individual experience

Most residents came with their level of interest in obstetrical practice based on undergraduate experiences. “My experience as a clerk – it was a hostile learning environment… it set the tone subsequently for not wanting to go into that field.” (RES8) Individual interest influenced the supervisor’s interest in teaching, thus keen learners were afforded more opportunities. “There are residents… that very much want to do obstetrics, and they get called more.” (FP4)

Opportunities in the training environment

There were challenges striking a balance between too much volume and too few opportunities at training centres, due to the variability of pregnancy care. “It’s a trade-off between volume of deliveries versus a more intimate birth experience as a learner.” (FP2) Supervisor-learner ratios amplified this, where smaller teaching ratios allowed for continuity of supervision and progressive autonomy for skill development. “By the third time I would be doing it on my own with them just watching.” (RES6)

FM maternity care role models influenced residents by providing a window into future practice. Those training in centres without FM maternity care supervisors felt that obstetrical skills were unnecessary. "I don’t know of any family provider that has delivered a baby...I don’t really see that it’s a good use of time to have those competencies on the list.” (RES8) In contrast, some supervisors promoted comfort in practicing intrapartum care immediately after residency. "I feel confident in my obstetrical skills. My preceptors have been encouraging me that they didn’t do extra training and they feel like I'm already on track.” (RES3) Those who had difficulty connecting with FM supervisors for deliveries, felt that enhanced skills training was necessary. It was important to prioritize teaching by FM maternity care supervisors who role modeled FM careers including maternity. “…maximizing the exposure to other family physicians who are doing obstetrics so…that they’re understanding, ‘This is what my life would be like if I was doing obstetrics.’” (OB3)

Participants perceived that few FM maternity care supervisors taught. “There’s a lot of family docs who do low-risk obstetrics in [this city], but the majority of those physicians are not very active in teaching residents.” (RES5) Participants also perceived an overall decline in providers. “Fewer family doctors are doing obstetrics, so when medical students or residents go to their core family rotations, they’re not being exposed to that.” (FP2) This was compounded by challenges where residents felt the onus was on them to find obstetrical experiences, “I didn’t get any additional electives in obstetrics.” (RES6)

Participants felt that since the CFPC and program consider obstetrical skills attainment to be important, the program should assume responsibility in connecting residents with opportunities. “It has been put on the resident to find those experiences, which I think is really unfortunate…If the program expects residents to have obstetrics, then they need to teach it.” (FP4)

The changing FM landscape

Residents experienced “hidden curricula” secondary to the changing FM landscape, implying they cannot be competent in obstetrics after training. With greater FM complexity, increased volume of content, higher risk pregnancies, and medicolegal concerns, there is increasing subspecialisation and beliefs that further training is required to be competent in obstetrical care. “FM is such a broad specialty and it’s impossible to learn how to be a low-risk obstetrician, a hospitalist, and a palliative care physician in two years.” (FP2) Residents viewed obstetrical care as a specific focus within FM. “I would do antenatal care and postnatal care, but I don’t think I actually want to be delivering. That said, I love it. Just not the area that I want to focus in.” (RES6) This has changed how the necessity of attaining this competency is perceived. FM maternity care role models were felt to be important to mitigate hidden curricula of subspecialisation.

They [specialists] have no concept of what it means to work with a family doctor, and what expertise we actually do have. I think it really diminishes the confidence of residents to feel that they actually can practice obstetrics, and they do have the skills, and this is a family physician specialty. (FP4)

Residents found sustainable work models encouraging their decision to practice. “Knowing that's a shared model so you don't have to be on call 24/7 for your practice. It just made sense.” (RES3) However, those exposed to soft call models found obstetrical care disruptive and deterring. “I saw that it was very nice for them to be able to deliver their own patient’s babies, but I did not particularly enjoy being woken up at 3:30 to…try to make a delivery, so I decided against it." (RES7)

Discussion

The themes address gaps in the literature exploring resident perspectives in at least the past decade while FM maternity care and training has changed. The most recent study, that by Koppula et al. in 2009,11 focused on resident experiences within a unique and newly developed primary care obstetrics program, whereas this study looked at the obstetrical training experience more common to FM training, which included working with obstetrician specialists.

The learner’s individual experience

This study adds to the literature by showing that most residents decided to practice obstetrics before starting postgraduate medical education. This means that to increase those choosing obstetrical care, programs need to provide fulsome experiences within the undergraduate medical education years. Medical students have indicated that experiences with FM maternity care throughout their undergraduate education would increase awareness of this field and the likelihood of it being pursued as a career.25 Educators should consider investing in undergraduate maternity education to inspire interest in this area.

Opportunities in the training environment

Many factors influencing the resident experience of obstetrical training within their local training environment have remained the same, especially concerning not having enough obstetrical experiences, lack of autonomy, lifestyle disruption, and the positive impact of smaller staff-to-learner ratios, FM role models, and sustainable call schedules.5,11,14,26

Our findings add to existing literature2,15,16,27 that programs should consider prioritizing FM maternity care providers teaching FM residents. Communities could consider recruiting and supporting teachers who practice obstetrics to role model and mentor FM residents even after graduation to improve graduating FM residents’ comfort with maternity care.

The changing FM landscape

New findings from this study reflect the changing FM landscape, that is, maternity care as a FM subspecialty. A similar study exploring FM residents learning palliative care, observed that simply having palliative care rotations may disengage residents “by reinforcing a notion that palliative care is a specialized area of medicine.” (page e582)28 Resident interpretation of where obstetrics fit into their career was in part influenced by FM role models. This is in keeping with previous research establishing that positive role models influence career choices of medical trainees.2,15,16,29,30

Future directions for research can consider what it means to be a comprehensive family doctor and establish a renewed curriculum that prioritizes maternity care teaching by comprehensive FM maternity care providers. Communities and hospitals can consider supporting varying work models to encourage participation.

Limitations

The study was conducted at one Ontario program; thus, it may not capture sensitivities to maternity care teaching across Canada. However, prior research has demonstrated these themes, and learning the resident experience within one program may be informative when planning others. We cautiously interpret the implications of the findings, such as in comparing urban and rural programs given the small sample size. Selection bias may favour participants with stronger feelings about the training program and maternity education. Lastly, we conducted the study during the COVID-19 pandemic, which created barriers to study recruitment. We did, however, recruit participants until reaching data sufficiency.20,21 Qualitative methodology captured the richness and depth of the participants’ ideas and perceptions.

Conclusion

This study updates our current understanding of FM resident and supervisor perceptions of factors influencing the attainment of obstetrical competency. The FM resident training experience of these participants was influenced by the individual learner’s pre-residency experience, opportunities in the training environment, and the changing FM landscape. FM maternity care role models played an important role within each theme. In understanding these themes, educators at local, program, and national levels can institute changes to mitigate underlying factors. Prioritizing maternity care education is critical considering the current maternity care crisis.

Appendix A. Interview guide

1. Introduction and Reiterating Verbal Consent

-Name, identification

-I am completing a thesis project for my graduate program at Western University. I am studying the experiences of trainees gaining their obstetrical competencies from the perspectives of the residents and their supervisors. I will start with questions to collect demographic information and then ask questions about your experiences. I anticipate this to take anywhere between 30-60 minutes.

-Recording, professional transcription, confidential

-Confirm consent

For Educators/Supervisors:

2. Demographics

-Age, ethnicity, gender

-Residency program and graduation year

-Current practice setting, years in practice, years teaching, current faculty position

-Role in relation to family medicine resident learners

3. Definitions, Expectations, Evaluations

-What is your understanding of the OB requirements for FM residents

-What guidance is given to you about what to expect of the FM residents

-How do you assess them; how do you “sign off” on an OB procedure

4. Eliciting experiences and feelings

-How important is it for all graduating family medicine residents to be competent in low-risk obstetrical care?

Prompt: Residents who have expressed an interest in practicing OB vs not interested

-The CFPC outlines family medicine obstetrical core procedures to include: normal vaginal delivery, artificial rupture of membranes, and episiotomy and repair. I really want to know from you, what do you think are the essential obstetrical competencies that family medicine residents should be graduating with?

-Prompt: Why or why not?

-From your experience, do you feel that family medicine residents are graduating with these obstetrical skills?

Why may that be?

-Prompt: In your opinion, what elements help a family medicine resident accomplish their obstetrical competencies?

-Prompt: In your opinion, what barriers do you feel exist that may hinder the resident from accomplishing these competencies?

For Family Medicine PGY2 Residents:

2. Demographics

-Age, ethnicity, gender

-Medical school and graduation year

-Current training site, structure of OB learning, OB experience with deliveries, OB electives

-Enhanced skills training and career plans

3. Definitions, Expectations, Evaluations

-What is your understanding of the OB requirements for FM residents

-What do you feel is expected of you as an FM resident on OB and on FMOB

-How are you assessed; how do you “complete” an OB procedure

4. Eliciting experiences and feelings

-How important is it for all graduating family medicine residents to be competent in low-risk obstetrical care?

Prompt: Residents who have expressed an interest in practicing OB vs not interested

-The CFPC outlines family medicine obstetrical core procedures to include: normal vaginal delivery, artificial rupture of membranes, and episiotomy and repair. I really want to know from you, what do you think are the essential obstetrical competencies that family medicine residents should be graduating with?

-Prompt: Why or why not?

-What is your experience in working towards your obstetrical competencies?

-Do you think that you will graduate feeling competent in these procedures?

Why may that be?

-Prompts:

-What would you need to accomplish to feel competent in these procedures?

-What would have needed to be different so that you can accomplish these goals?

-What helps you work toward your obstetrical competencies?

-What barriers do you face in working toward these competencies?

-What is your experience in working with a family medicine obstetrician as opposed to a specialist obstetrician/gynecologist as it pertains to your obstetrical learning goals?

Funding Statement

Funding:

Financial support for the research presented in this manuscript was provided by:

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has disclosures of financial and personal relationships that could potentially bias the work.

The Graduate Student Research Fund from The Centre for Studies in Family Medicine at Western University

Martin J. Bass PSI Foundation Bursary from the Graduate Program Office in Family Medicine at Western University

Dr. Wm. Victor Johnston Award in Family Medicine from the Graduate Program Office in Family Medicine at Western University

Dr. Keith Johnston Scholarship from the London Citywide Department of Family Medicine

Edited by

Charo Rodriguez (section editor); Cindy Schmidt (senior section editor); Marcel D’Eon (editor-in-chief)

References

- 1.Popadiuk C. The changing landscape of obstetrical care in Canada. J Obs Gyn Can. 2020;42(11):1305-1306. 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dove M, Dogba MJ, Rodríguez C. Exploring family physicians’ reasons to continue or discontinue providing intrapartum care. Can Fam Phys. 2017;63(8):e387-e393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Leeuw S. The missing of mums and babes. Can Fam Phys. 2016;62(7):580-583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godwin M, Hodgetts G, Seguin R, MacDonald S. The Ontario family medicine residents cohort study: factors affecting residents’ decisions to practise obstetrics. CMAJ. 2002;166(2):179-184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall EG, Horrey K, Moritz LR, et al. Influences on intentions for obstetric practice among family physicians and residents in Canada: an explorative qualitative inquiry. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2022;22(1):857. 10.1186/s12884-022-05165-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchman S. It’s about time: 3-year FM residency training. Can Fam Phys. 2012;58(9):1045-1045. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler N, Oandasan I, Wyman R, eds. Preparing our future family physicians. an educational prescription for strengthening health care in changing times. Published online 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen ER, Eden AR, Peterson LE. A qualitative study of trainee experiences in Family Medicine-Obstetrics fellowships. Birth. 2019;46(1):90-96. 10.1111/birt.12388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biringer A, Almond R, Dupuis K, et al. Report of the Working Group on Family Medicine Maternity Care Training. College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2012. Available from https://www.cfpc.ca/report_maternity_care_training/ [Accessed Dec 22, 2019].

- 10.Fowler N, Wyman R, eds. Residency training profile for family medicine and enhanced skills programs leading to certificates of added competence. Published online May 2021. Available from https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/Resources/Education/Residency-Training-Profile-ENG.pdf. [Accessed June 30, 2023].

- 11.Koppula S, Brown JB, Jordan JM. Experiences of family medicine residents in primary care obstetrics training. Fam Med. 2012;44(3):178-182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruderman J, Holzapfel SG, Carroll JC, Cummings S. Obstetrics anyone? How family medicine residents’ interests changed. Can Fam Phys. 1999;45:638-647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid AJ, Carroll JC, Ruderman J, Murray MA. Differences in intrapartum obstetric care provided to women at low risk by family physicians and obstetricians. CMAJ. 1989;140(6):625-633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckle D. Obstetrical practice after a family medicine residency. Can Fam Phys. 1994;40:261-268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakornbut EL, Dickinson L. Obstetric care in family practice residencies: a national survey. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1993;6(4):379-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratcliffe SD, Newman SR, Stone MB, Sakornbut E, Wolkomir M, Thiese SM. Obstetric care in family practice residencies: a 5-year follow-up survey. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):20-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabir M, Randall E, Mitra G, et al. Resident and early-career family physicians’ focused practice choices in Canada: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(718):e334-e341. 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulich Medicine and Dentisty . Obstetrical Log. Available from https://www.schulich.uwo.ca/familymedicine/postgraduate/current_residents/curriculum/obstetrical_log.html [Accessed May 13, 2024].

- 20.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893-1907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morse JM. The significance of saturation. Qual Health Res. 1995;5(2):147-149. 10.1177/104973239500500201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busetto L, Wick W, Gumbinger C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol Res Pract. 2020;2(1):14. 10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2015;15(2):219-234. 10.1177/1468794112468475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodgson JE. Reflexivity in qualitative research. J Hum Lact. 2019;35(2):220-222. 10.1177/0890334419830990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dini Y, Avolio J, Forte M. The medical learner perspective: family medicine obstetrics as a specialty choice. Canadian Family Physician. Published online November 9, 2022. Available from https://www.cfp.ca/news/2022/11/09/11-09 [Accessed Nov 13, 2022].

- 26.Reid AJ, Carroll JC. Choosing to practise obstetrics. Can Fam Phys. 1991;37:1859-1867. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutter MB, Prasad R, Roberts MB, Magee SR. Teaching maternity care in family medicine residencies: what factors predict graduate continuation of obstetrics? A 2013 CERA program directors study. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):459-465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahtani R, Kurahashi AM, Buchman S, Webster F, Husain A, Goldman R. Are family medicine residents adequately trained to deliver palliative care? Can Fam Phys. 2015;61(12):e577-582. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, Wright S, Hafferty F, Johnson N. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME Guide No. 27. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1422-1436. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sud S, Wong JP, Premji L, Punnett A. Career decision making in undergraduate medical education. Can Med Educ J. 2020;11(3):e56-e66. 10.36834/cmej.69220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]