Abstract

Background and Objectives

Age-friendly community initiatives (AFCIs) have gained recognition as essential responses to the needs of aging populations. Despite their growing significance, there is a notable lack of effective measurement tools to assess the planning, implementation, and sustainability of AFCIs. The purpose of this study was to develop and validate a survey tool for evaluating AFCIs.

Research Design and Methods

A sequential exploratory mixed-method design was used in 2 phases. First, we identified key themes from interviews with AFCI leads to generate AFCI survey items and regional workshops. Then, we conducted a pilot of the survey and assessed its measurement properties.

Results

Thematic analysis of interviews with 68 key informants from 58 AFCIs revealed 4 main themes: AFCI priorities, enablers, challenges, and benefits. These themes, combined with feedback from AFCI stakeholders at the regional workshops and an AFCI conference, informed the development and refinement of a reliable and valid AFCI survey in 2019, supported by a high Cronbach’s alpha value (α = 0.881). Steps were identified to maintain and sustain the AFCI survey over time.

Discussion and Implications

The survey accommodates AFCIs’ diverse demographics, governance structures, and priorities with a standardized and flexible approach for effective measurement. This research contributes to the academic understanding of AFCIs and aids community leaders and policy-makers in planning, implementing, and evaluating AFCIs.

Keywords: Active aging, Age-friendly environments, Evaluation, Measurement, Survey design

Background and Objectives

Age-friendly community initiatives (AFCIs) carry out age-friendly planning and implementation in local communities and have emerged as a pivotal response to the growing need for supportive environments that enable older adults to age in place (Centre for Studies in Aging and Health [CSAH], 2023a). The evolution of these communities reflects a profound change in societal attitudes toward aging and the roles of older adults, emphasizing the need for continued innovation and adaptation in urban planning and policy-making. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an AFCI as a region with policies, structure, services, and settings that support active aging, and currently recognizes approximately 1,445 communities and cities in 51 countries as AFCIs (WHO, 2024). Launched in 2007, the WHO’s Global Age-Friendly Cities and Communities initiative aims to promote active aging in cities and communities worldwide through supportive and sustainable environments (WHO, 2008).

AFCIs in Ontario

The demographic profile of Ontario, Canada, is transforming, with the proportion of older adults expected to almost double in all municipalities from 3 million in 2016 to 4.6 million in 2041 (Government of Ontario, 2022). This shift presents a compelling need for ongoing development of sustainable planning and implementation for AFCIs. As of June 2024, there are 72 active AFCIs in Ontario’s 444 municipalities (14%), spanning a diverse array of geographies, population densities, and municipal governance structures (CSAH, 2023a).

In Ontario, the Ontario AFC Planning Guide (Government of Ontario, 2021) informs AFCIs and facilitates the implementation of tailored strategies to promote secure and accessible physical and social environments for individuals of all age groups. This guide outlines an ongoing cyclical process for planning, implementing, evaluating, and sustaining AFCs. This process includes defining local principles, through assessing needs, developing an action plan, implementing and evaluating those actions, maintaining momentum, and sustaining long-term success (Government of Ontario, 2021). To achieve these objectives, Ontario AFCIs engage in activities, interact with the community, use age-friendly resources, and collaborate with various organizational stakeholders through iterative cycles of planning and implementation. Understanding the unique characteristics of AFCIs, including their diverse needs, priorities, and plans, is crucial for gaining insight into the mechanisms through which communities evolve AFC planning and implementation.

Evaluating AFCIs

In developing the Global Age-Friendly Cities Project, the WHO identified eight interconnected domains of AFCs that contribute to the age-friendliness of a municipality, community, or city (Figure 1; WHO, 2008). In 2015, the WHO released a guide of core indicators to measure the age-friendliness of cities, including equity measures, accessible physical, inclusive social environments, and impact on well-being (WHO, 2015). A pilot study conducted by Kano et al. (2018) on the core AFCI indicators found that, although they are useful for assessing physical environment factors affecting older adults, further refinement and measurement of the indicators is needed. This study also concluded that AFCIs are measured using inconsistent methods including direct field indicators, secondary survey data, primary survey data, and focus groups.

Figure 1.

The eight domains of age-friendly community initiatives (Wang et al., 2021).

In 2015, the Ontario AFC Outreach Program (OP), funded by the Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility (MSAA), was established to facilitate and evaluate Ontario communities as they progressed through the stages of AFCI planning, implementation, and evaluation. The AFC OP is managed by the CSAH and supports communities by providing resources, educational materials, e-learning courses, knowledge exchange tools, webinars, best-practice research, and conferences (CSAH, 2023b). The Public Health Agency of Canada has also taken steps to assist communities in measuring the progress and impact of AFCIs in Canada. In 2016, they introduced an age-friendly evaluation guide (Orpana et al., 2016; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2016), with a list of 43 recommended indicators for AFCIs to adopt in part, or as a whole. However, this has resulted in inconsistent reporting from AFCIs across Canada and Ontario, increasing the difficulty of comparing and evaluating the progress of implementation within and between AFCIs.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (2016) recommended the development of surveys as a primary means to assess and evaluate the indicators and impact of AFCIs. To date, there has been little research exploring how organizations can utilize validated and generalizable tools to enhance and support the age-friendliness of their communities. In fact, there are few validated instruments capable of effectively assessing the planning, implementation, and sustainability of AFCIs across all eight AFC domains (Dellamora et al., 2015; Torku et al., 2020), and there is a scarcity of longitudinal data studies that track the long-term effectiveness of these initiatives (Kim et al., 2022; Menec & Nowick, 2014). For instance, Kim et al. (2022) identified the need for the design and implementation of a brief AFC tool, as their current survey is particularly long, incorporating all 62 indicators. Additionally, there has been a lack of evidence-based evaluation tools to monitor, evaluate, measure, and assess AFCIs that can be generalized to multiple contexts and populations (Buckner et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2022). Although survey and evaluation tools such as the Age-Friendly Survey (Menec & Nowick, 2014), the Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (Polco, 2020), and the Age-Friendly Environment Assessment Tool (Garner & Holland, 2020) have been effective in assessing AFCIs, these tools vary in terms of focus, accessibility, and length, and have yet to be tested or validated across diverse environments or samples, such as AFCIs in Canada, and, more specifically, Ontario (Kim et al., 2022). As such, the gap in validated instruments for diverse environments and samples calls for the creation of a specific measurement tool for AFCIs in Ontario.

Further research is essential to determine the suitability and effectiveness of an AFCI survey within Ontario AFCIs and its generalizability to other geographical regions. Consequently, the purpose of this study is to develop and validate a comprehensive survey tool tailored to assess AFCIs in Ontario. The objectives of this study are multifaceted:

Create a survey specifically designed to assess AFCIs in Ontario, addressing the inadequacy of existing instruments for diverse environments and samples.

Rigorously assess the face and content validity of the newly developed AFCI survey.

Understand and promote the use of the survey tool as a means to evaluate AFCIs, and facilitate knowledge exchange and the adoption of best practices in a broader context.

This survey will not only enhance the understanding of AFCIs within Ontario but also may be used and adapted to facilitate and substantiate well-informed policy decisions for future AFCIs across Canada. Ultimately, this research will contribute to creating supportive environments that enable older adults to age in place, thereby advancing the global body of knowledge on age-friendly communities.

Method

Research Design

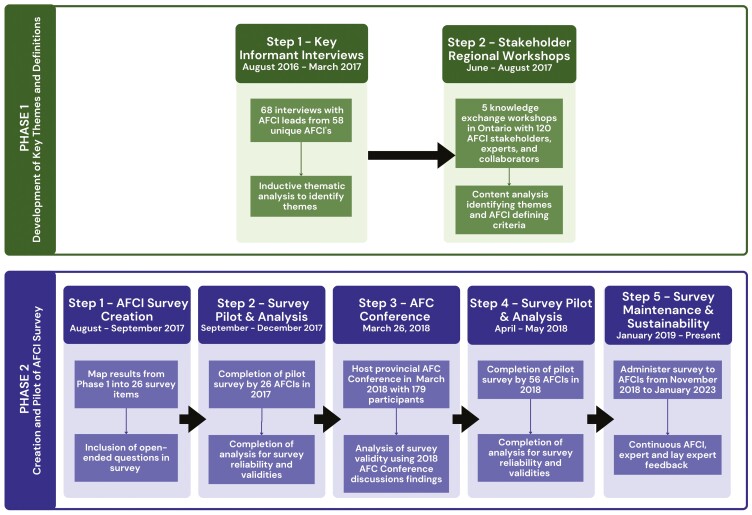

This study employed a sequential exploratory mixed-method design using an iterative approach (Schoonenboom & Johnson, 2017) to create a survey, which assesses the development and impact of AFCIs in Ontario, Canada. All aspects of data collection, analysis, and reporting align with the participatory nature of AFCIs, prioritizing the perspectives and experiences of local AFCI members and leads responsible for planning and implementation. The study was conducted in two phases; (a) interviews and regional workshops were conducted to identify and develop key themes used to generate AFCI survey items, and (b) developing, piloting, and analyzing the AFCI survey. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of each stage of this study, with a timeline and detailed explanations in the subsequent sections. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (Approval #6020047).

Figure 2.

An outline of the study phases for the development and assessment of an Age-Friendly Community Initiative survey.

Phase 1: Development of Key Themes and Definitions (Steps 1 and 2)

The first phase aimed to inform survey development by establishing a comprehensive understanding of the perspectives, experiences, and needs of local AFCIs, older adults, and relevant stakeholders. This involved conducting semistructured interviews with key informants (Step 1), from which key themes and definitions were generated and presented at regional AFCI workshops (Step 2) for review and validation by subject matter experts (SMEs) in AFCIs and gerontology.

Step 1: AFCI key informant interviews

An interview guide was developed in 2016 and updated in 2017 by the AFC OP staff and researchers, with input from other AFC experts and SMEs. These interviews, lasting between 30 and 60 min, explored the enablers, barriers, and lessons learned in AFCI planning and implementation. An interviewer and research assistant co-conducted all interviews. In 2016, there were 15 interviews completed with key informants (i.e., self-identified AFCI leads) from AFCIs in Ontario. In 2017, researchers then interviewed 53 AFCI leads, for a total of 68 interviews within 58 unique AFCIs between 2016 and 2017.

Key informant interview data analysis

A research assistant transcribed the interviews in real time. The interviews were also audio recorded, with transcriptions and interview notes checked for accuracy prior to data analysis. Each set of interviews underwent inductive thematic analysis (Maguire & Delahunt, 2017), facilitated by Excel software (Microsoft Corporation, 2016). Two researchers independently organized coded statements, which were then coded into categories to identify initial themes (Schwandt et al., 2007). To ensure the reliability validity of the analysis, inter-coder reliability was established by comparing the independent coding of the interviews between the two researchers. Any discrepancies between the analyses were then discussed with the research team until a consensus was reached. Triangulation was established by using multiple sources of data (i.e., interview notes, audio recordings, and transcriptions) to corroborate the findings. Finally, member-checking was conducted by inviting key informants to review the preliminary findings and provide feedback to confirm the accuracy of the interpretations and findings (Schwandt et al., 2007). The themes identified in this stage informed the creation of discussion questions and workbooks for the regional workshops in Step 2.

Step 2: stakeholder regional workshops

Between June and August 2017, five regional knowledge exchange workshops were held across the province with 120 AFCI stakeholders representing 65 Ontario communities. A facilitator with expertise in AFCIs was present at each workshop to assist with organization, discussions, and feedback. The aim of these workshops was to convene AFCI stakeholders, experts, and collaborators from communities in Ontario to (a) review and verify the interview findings in Step 1 of Phase 1, (b) share local experiences, and (c) provide input on selected issues cutting across most AFCIs. At the workshops, facilitators shared examples from the eight AFC domains, and then presented and verified findings from the interviews. Participants met in small groups to discuss pertinent themes identified in Phase 1 including sustainability, social isolation, and AFC stages.

Step 2: qualitative data analysis

After each workshop, all written data from each group was aggregated by a research assistant and then analyzed using content analysis methods (Krippendorff, 2018), aided by Excel software (Microsoft Corporation, 2016). The content analysis involved systematically coding the data to identify recurring themes, patterns, and categories. Researchers carefully examined the data for both explicit content and underlying meanings, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ perspectives (Krippendorff, 2018). Researchers then presented the resulting themes back to workshop participants and facilitators for peer review and member-checking through executive summary reports and presentations to regional AFC networks (Schwandt et al., 2007). The definitions and themes then underwent a final round of analysis and accuracy checking before being summarized in a final report for dissemination to relevant stakeholders, including workshop participants and provincial AFC regional network members. Results from Phase 1 informed the development of the AFCI survey tool and process in Phase 2.

Phase 2: Creation and Pilot of AFCI Survey (Steps 1–3)

In Phase 2, AFCI leads completed the pilot AFCI survey twice, in 2017 (26 AFCI respondents) and 2018 (56 AFCI respondents).

Step 1: creating the AFCI survey

Themes and definitions identified in Phase 1 were used to generate survey items for the pilot 2017 AFCI survey, along with items pertaining to AFCI demographics such as community name, year AFCI planning began, funding source, current lead, and committee representation. Open-ended questions provided respondents the opportunity to provide qualitative information on their AFCI. The survey was designed to be administered online to all participants using SurveyMonkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com). The online format was chosen to maximize accessibility and convenience, allowing participants to complete the survey at their own pace and in their own environment.

Step 2: 2017 AFCI survey pilots

The second step of Phase 2 involved piloting the AFCI survey with 26 AFCIs in Ontario between September 2017 and December 2017. The 2017 survey included Likert survey items (N = 3), multiple-choice items (N = 6), “yes/no” items (N = 3), AFCI demographic items (N = 8), and open-ended question items (N = 6). The MSAA, who provided funding for this project, provided a list of AFCIs for the participants of the first pilot AFCI survey. Using purposive sampling, researchers contacted all AFCIs on the list provided by the MSAA to complete the survey in August 2017. Researchers used Excel 2016 software (Microsoft Corporation, 2016) to remove missing data and complete manual checks of data entry, coding, or labeling errors, and IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The AFCI survey was then statistically tested for reliability and validity.

Reliability

The data analysis for the reliability of the pilot survey involved calculating Cronbach’s alpha for each set of items to determine how closely related they are as a group, thereby ensuring the internal consistency of the survey. With IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27), Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency reliability of the nine Likert and multiple-choice survey items (Zijlmans et al., 2018). These nine questions identified each AFCI age-friendly priority domain, completed planning and implementation steps, target subpopulations, helpful supports, challenges, benefits, resource usefulness, influential factors, and usefulness of the Ontario AFC Planning Guide. Survey items using dichotomous responses, open-ended questions, or those pertaining to AFCI demographics were not included in the reliability testing.

Validity

Researchers first employed a qualification method to assess face validity (Allen et al., 2023), where four AFC experts and SMEs were asked to review the 2017 survey items. These experts and SMEs were identified by the research team based on their contributions, experience, and recognized expertise in the fields of aging and AFCs. Through group discussions and individual meetings, these experts and SMEs were asked to provide feedback on the clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness of the survey items (Jhangiani et al., 2020). An iterative qualification method (Haynes et al., 1995; Zamanzadeh et al., 2015) was then used to assess content validity by examining the verbal and written responses from the semistructured interviews in Phase 1 and from the judgment of SMEs in aging, AFCs, and health. SMEs reviewed the content of the 2017 AFCI survey to assess the relevance of the survey items. The content validity assessment involved a detailed examination of the survey items to ensure they adequately covered all relevant aspects of the AFC domains and were appropriate for the target population. This feedback was used to inform changes made to the content and formatting of the 2018 survey, outlined subsequently.

Step 3: AFCI conference

On March 26, 2018, the research team held the “Ontario Age-Friendly Communities Symposium: Aging with Confidence.” Qualitative data from this conference, which included 179 attendees who represented 51 communities and 57 organizations from across Ontario, informed updates to the 2018 AFCI survey. The symposium focused on key topics identified in Phase 1 including AFCI sustainability, challenges, and target populations. During this event, four breakout sessions were conducted, where attendees were asked to share insights on AFCI implementation and evaluation, rank factors important for AFCa success, and identify gaps in enablers and supports. Discussion from each breakout group was recorded by a moderator using field notes and verbally reported back to all conference participants. The field notes were then coded using thematic analysis by the research team, summarized in a written report, and used to contribute to the ongoing survey refinement.

Step 4: 2018 AFCI survey pilot

A revised AFCI survey was administered to AFCIs between April and May 2018. This survey was completed by 56 AFCIs and used the same data collection and analysis process as described earlier in Phase 2: Step 2. As such, the internal consistency reliability of 15 items in this revised survey was analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27), using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Zijlmans et al., 2018).

Step 5: AFCI survey maintenance and sustainability

Since 2019, the revised AFCI survey has been annually administered to Ontario AFCI leads, with the yearly addition of a few items and improvements in usability. The data collection and analysis methods described in Steps 2 and 4 of Phase 2 were also implemented for this stage of the study. For the 2019 survey, the internal consistency reliability of 17 items was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 2951; Zijlmans et al., 2018). The survey underwent minor revisions to ensure the relevance of items to all AFCIs in Ontario. Additional survey items were added ad hoc (e.g., the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]).

Results

Phase 1—Step 1 (Key Informant Interviews)

In Step 1 of this phase, 68 interviews with self-identified AFCI leads from 58 different AFCIs were completed. The governance model of each AFCI included 27 (51%) community-municipal steering committees, nine (17%) municipal advisory committees, five (9%) community-led AFCs, five (9%) municipal department staff, three (6%) committee of councils, three (6%) community and municipal committees together, and one unknown (2%). All AFCIs had gone through, or were in, the planning stage of their AFCI, whereas 42 (79%) of the AFCIs were currently in or had gone through the implementation stage. Of the 58 unique AFCIs, there were 30 (51.7%) small urban/rural AFCIs and 28 (48.3%) urban communities. This included one rural AFCI in 2016 and 29 rural AFCIs in 2017. A total of 23 (43%) communities reported using a consultant for their planning and implementation.

Results from the key informant interviews were coded into four themes, including AFCI priorities, enablers to the planning and implementation of AFCIs, challenges to planning and implementing AFCIs, and benefits of AFCIs. Each theme, category, and relevant representative quotations identified from the keyinformant interviews are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Informant Interview Themes and Categories for Developing the 2017 AFCI Survey

| Theme | Categories | Relevant quotes |

|---|---|---|

| AFCI priorities |

|

“Township is looking at more civic engagement opportunities for seniors now; some are already now participating on other working groups; developing their skill sets; sense of empowerment” “Community halls are under-utilized—could be a great gathering spot but they are old and not accessible” |

| Enablers to planning and implementation of AFCIs |

|

“Champions pushing project forward are so important, it results in a shared sense of responsibility” “Consistent funding is needed, otherwise there are gaps in the project” “We needed early help of a geriatric [academic] professor to get research focus and best practices” |

| Challenges to planning and implementation of AFCIs |

|

“Because of geography, need to hold a lot of repeat events across the area which requires a lot of resources” “Volunteer Burnout … volunteers are older adults and this process ends up becoming stressful for them when they should be celebrated for contributing to the community in this way” |

| Benefits of AFCIs |

|

“We were able to create a network of service providers in the community” “Students involved collected surveys; started as just a job but they loved it and learned a lot; 2 of those students now volunteering in retirement homes” “AF has been incorporated into the City’s Official Plan (20 year) and part of strategic priorities (4 year)” |

Notes: AF = age-friendly; AFCI = age-friendly community initiative.

In addition to the themes and categories identified in Stage 1, researchers also separately identified strategies for sustainability and lessons learned for sustainability across the AFCI planning cycle during the analysis of the key informant interviews. Table 2 outlines these strategies and lessons learned during the key informant interviews specific to the sustainability of AFCIs. AFCIs identified four overarching goals for future initiatives, including (a) obtaining dedicated staff to push a project forward, (b) setting clear expectations and goals with consultants, (c) understanding that culture change takes time, and (d) communicating regularly with all stakeholders.

Table 2.

Key Informant Interview Findings: Strategies and Lessons Learned for Sustaining AFCI

| Topic | Strategies and lessons learned | Relevant quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Overarching AFCI goals |

|

“Be more specific in RFP about what was required/deliverables” “Would have asked for report more focused on local context” |

| AFCI steering committee |

|

“Would have done formal check in with city sooner & stronger relationship with mayor/council” “Champions pushing project forward are so important = shared sense of responsibility” |

| AFCI needs assessment |

|

“Would have done more 1-1 interviews for rich data” “No matter how much you communicate, it is never enough - keep doing more!” |

| AFCI action plan |

|

“Would have gone straight to the real plan as a template – considering not individual suggestions but emerging themes and taking those to action” |

| AFCI implementation and evaluation |

|

“Start thinking early about evaluation and consider high-level indicators, satisfaction surveys & process evaluation” “Develop concrete measurable objectives from the beginning” |

| AFCI sustainability |

|

“Sharing information around what has worked well for other communities and what hasn’t has been very helpful—keeping this communication open and maybe facilitated would be great” “Reporting back and showing success to community to keep engaged” |

Notes: AFCI = age-friendly community initiative; RFP = request for proposal.

Phase 1—Step 2 (Stakeholder Regional Workshops)

A total of 120 participants representing 65 Ontario communities attended the five regional workshops. Of these respondents, 17.6% were older adults, 36.3% municipal staff, 2.9% politicians, 8.8% community service providers, 36.3% members of an AFC committee, 5.9% academic, and 3.9% were regional advisors. The geographical representation of participants included 10 (8.3%) from the Northwest Region, 20 (16.7%) from the Northeast Region, 22 (18.3%) from the East Region, 20 (16.7%) from the Central Region, and 48 (40%) from the West Region.

Informed by the findings from the key interviews in Step 1, the regional workshops identified five subpopulations of older adults that should be prioritized for AFCI supports: older adults who are Francophone, immigrants, Indigenous elders, living in small urban/rural communities, and/or socially isolated. In addition, two overarching themes and six categories were identified pertaining to the AFCI process. The two themes were (a) important considerations for planning and implementing AFCIs and (b) strategies for engagement. Supplementary Appendix A provides an overview of the themes and findings for each subpopulation identified in this stage of research. Key findings on AFCI sustainability from Phase 1, Stage 1 were confirmed and synthesized at the regional workshops (Supplementary Appendix B). The following definition of sustainability emerged and was validated during these workshops:

Establishing ongoing and productive partnerships between a network of individuals, groups, organizations, and planners committed to planning and incorporating age-friendly principles within a community; encouraging organizations to incorporate age-friendly activities into their core missions; providing hard data and evaluation findings to document the benefits of age-friendly communities; and ultimately securing long-term sources of non-financial, as well as financial support.

This definition informed the development of items related to AFCI sustainability in the AFCI survey developed in Phase 2. Participants in the regional workshops also identified nine factors contributing to and enabling the sustainability of AFCIs: demonstrable provincial leadership, regional and local leadership, governance, and infrastructure, representative critical mass, funding, communication, strategic alignment, academic involvement, long-term planning, and inclusiveness.

Phase 2—Step 1 (2017 Pilot AFCI Survey)

The 2017 pilot AFCI survey (Supplementary Appendix C) included 26 items pertaining to AFCI status, funding and governance, AFCI priorities, target subpopulations, AFCI enablers, challenges and benefits, AFCI sustainability, use of AFC supports and resources, community gaps and needs, AFCI strategies, and factors influencing AFCI planning and implementation.

Phase 2—Steps 2–4 (2017 and 2018 Pilot Surveys)

The findings in this section are a collation of the results from the 2017 and 2018 AFCI surveys. Stakeholder feedback from the 2018 Conference in Step 3 generated provincial- and community-level recommendations for current AFCIs and future AFCI messaging, partnership, and engagement. Feedback on missing enablers, challenges, and supports informed subsequent AFCI survey revisions. The demographic characteristics of the 2017 pilot survey sample are shown in Table 3, including the date the AFC started, the number of AFCs who self-identify as small urban and/or rural, how AFCs were funded, the type of AFC lead, and the AFC committee representative.

Table 3.

2017 Pilot Survey Results: AFCI Survey Demographic Information

| 2017 Survey results, N (%) | 2018 Survey results, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of AFCs | 26 | 56 |

| Date AFCs started | Range 2008–2017 Average 3.7 years |

a |

| Number of AFCs who self-identify as small urban and/or rural | 17 (65.4%) | 33 (75%) |

| How AFC was funded | ||

| Ministry of seniors affairs | 6 (23.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ontario trillium foundation grant | 5 (19.2%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| New horizons grant | 6 (23.1%) | 12 (21.4%) |

| Other grant | 1 (3.8%) | 10 (17.9%) |

| Municipal one-time funding | 1 (3.8%) | 11 (19.6%) |

| Municipal core funding | 4 (15.4%) | 12 (21.4%) |

| No funding | 10 (38.5%) | 12 (21.4%) |

| Other non-grant | 12 (46.2%) | 11 (19.6%) |

| AFC lead | ||

| Municipal staff | 6 (23.1%) | 14 (25%) |

| Community-based organization | 6 (32.1) | 10 (17.9%) |

| Other | 10 (38.5%) | 8 (14.3%) |

| Municipal advisory committee | 3 (11.5%) | 7 (12.5%) |

| Municipal committee of council | 1 (3.8%) | 4 (7.1%) |

| Committee representative | ||

| Older adults | 19 (73.1%) | 41 (73.2%) |

| Municipal staff | 18 (69.2%) | 40 (71.4%) |

| Politicians | 11 (42.3%) | 25 (44.6%) |

| Community service providers | 17 (65.4%) | 38 (67.9%) |

| Academics | 8 (30.8%) | 17 (30.4%) |

| Private sector | 7 (26.9%) | 17 (30.4%) |

| Public health partners | 2 (7.7%) | 31 (55.4%) |

| Other | 8 (30.8%) | 11 (19.6%) |

Notes: AFC = Age-friendly community; AFCI = age-friendly community initiative.

aNot included as a question/option in this survey due to this information already being collected the year prior.

In 2017, 26 AFCIs completed the AFCI survey, with 17 (65.4%) self-identifying as small urban and/or rural communities. The response rate for active AFCI communities in the 2017 pilot test was 93%. Community population size ranged from 1,013 to 5,928,040, with a mean population of 328,152 and a median of 79,137.

In 2018, a total of 56 AFCIs completed the revised AFCI survey. Of these responses, 33 (75%) of the AFCIs self-identified as small urban and/or rural communities. Twelve AFCIs (21.4%) indicated they had discontinued their AFCI in the previous year and were therefore not reported on. Reasons for discontinued AFCIs were no or a lack of funding (N = 2, 16.7%), no dedicated staff (N = 4, 33.3%), no political/municipal support (N = 1, 8.3%), and the reorganization of their governing committee (N = 1, 8.3%). The community population size ranged from 613 to 5,928,040, with a mean population of 265,671 and a median of 43,812.5. Missing data from either paused or discontinued AFCIs (N = 229, 8.7%) were removed from each data set prior to analysis.

Survey reliability

The 2017 AFCI survey value for Cronbach’s alpha (N of items = 51, α = .988) showed a very high level of consistency between the survey items (excluding items pertaining to the AFCI demographics), suggesting redundancy in the survey items (Pallant, 2011). The 2018 AFCI survey value for Cronbach’s alpha (N of items = 81, α = 0.998) similarly showed even higher levels of consistency between the survey items. Given these results, changes were made to the final survey to reduce redundancy among survey items and prioritize AFCI sustainability. This included the removal of eight survey items and re-wording of two items. The 2019 AFCI survey value for Cronbach’s alpha (N of items = 115, α = 0.881) showed a high and appropriate internal consistency for the final version of the survey.

Survey validities

Applying the findings from the face and content validity testing with experts and conference participants, seven survey items were removed, 27 items were added, and 7-item descriptions were edited from the 2017 survey. As such, a total of 48 survey items were included in the 2018 survey. For the seven edited items, changes were made to the language, grammar, and type of item (i.e., open-ended vs Likert scale) following the feedback and expert reviews. The additional 27 items added to the survey were included to obtain more detailed responses to the subpopulations and sustainability domains.

The feedback and recommendations from the 2018 AFC conference participants were used to identify seven key topics of interest, which informed updates to the 2018 AFCI survey before its dissemination. Conference participants had three main recommendations for improving the survey: (a) refine the assessment of implementation and sustainability actions, (b) add implementation enablers and challenges encountered by the AFCIs into the survey, and (c) add perceived AFCI outcomes to the survey. Specifically, the breakout groups at the 2018 AFC Conference identified the importance of sustainability, inclusivity of diverse populations, long-term AFCI strategies, strategic alignment, involvement of academics, communication strategies, funding, establishing a critical mass, leadership, governance, and infrastructure. Accordingly, the 2018 survey included additional items to identify whether AFCIs had considered each factor, and if they had, elucidating the manner in which they have done so.

Phase 2—Step 5 (AFCI Survey Maintenance and Sustainability)

The final AFCI survey had 40 items (Supplementary Appendix D) and was distributed and completed by 68 AFCIs between November 2018 and January 2019. Based on the findings from earlier phases and steps, the final AFCI survey covers seven topics, including (1) current AFCI status, (2) AFCI funding and governance, (3) current activities of the AFCI, (4) use of AFC OP supports, (5) enablers, challenges, and benefits of the AFCI, (6) AFCI sustainability, and (7) engaging diverse populations. The response rate for this survey administration was 82%, and 29 (42.6%) of the AFCIs self-identified as small urban and/or rural communities. Three of these AFCIs (4.5%) indicated they had discontinued their AFCI in the previous year and were excluded from reporting for this survey cycle. Since its development, the survey tool has continued to yield high participation rates: 82% (N = 72) in 2020, 81% (N = 60) in 2021, 89% (N = 66) in 2022, and 71% (N = 55) in 2023.

Discussion

The findings revealed a complex landscape of AFCI priorities, used to create a detailed and adaptable survey for assessing an AFCI at local and provincial levels. The diverse demographics and governance structures of AFCIs in Ontario necessitate a versatile research tool capable of addressing both the unique and collective aspects of these communities. This study, addressing a gap identified by previous researchers such as Dellamora et al. (2015) and Kim et al (2022), has developed a survey instrument that adapts to the complexities of individual AFCIs. This validated survey represents a significant advancement over previous tools by offering a standardized yet flexible approach for comparing AFCI assessments across various stages, dimensions, and settings. This approach meets a critical need in the field, benefiting both researchers and practitioners. The theoretical significance of this new survey tool lies in its ability to integrate and operationalize the multifaceted nature of AFCs into a coherent and systematic measurement tool. By encompassing diverse demographic and governance variables, the tool transcends traditional one-size-fits-all models, offering a nuanced mechanism for capturing the dynamic interactions between policy, environment, and population characteristics. This allows for a more precise and contextually relevant understanding of how AFCIs function and evolve over time.

AFC programs yield varied priorities with different outcomes based on local needs, available resources, individual experiences, and unique contexts. Importantly, the contexts in which programs operate (e.g., geographic, social, and institutional) also affect the priorities and outcomes that may be achieved. This was identified in the various themes, strategies, and findings identified in the semistructured interviews and regional workshops in Phase 1 of this study. Russell et al. (2020) described similar findings in their qualitative study, identifying a range of contextual community factors, such as social and geographic connectivity, that directly affect rural AFCs' success and sustainability. As such, the Ontario AFCI survey could be used to discern these nuances by enabling stakeholders to understand the mechanism through which AFCs operate within different contexts.

Applicability and Generalizability

This novel survey tool enables a detailed examination of AFCI outcomes at provincial, regional, and community levels, and offers critical data for local decision-making and strategic planning. Its versatile design is particularly effective in guiding future AFCIs to assess and address emerging needs, such as those presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. By evaluating AFCIs across a range of environments and samples, this survey aids communities in identifying patterns and trends specific to their region and province. Such insights can be used to support funding applications and allocations by governing bodies and ministries. The practical application value of the Ontario AFCI survey is substantial for community leaders, policy-makers, and future AFCIs. For community leaders, the survey tool helps identify specific needs and priorities within their communities by providing detailed insights into AFCI processes and outcomes over time both locally and within a regional network. This aids in strategic planning and decision-making, allowing leaders to allocate effort and resources effectively based on the survey’s findings. For policy-makers, the survey supports the assessment of AFCI effectiveness by offering empirical data that can inform policy decisions and the development of targeted interventions. Insights from the survey can justify funding allocations and support applications for additional resources, demonstrating the value and impact of AFCIs. Additionally, the survey guides the development and implementation of new AFCIs with a range of community types and geographies by monitoring progress and adapting strategies to meet evolving needs.

This survey tool not only supports local initiatives but also provides a framework that other regions and cultural contexts can adopt and customize to their unique needs. Conducting pilot studies in diverse settings will help refine the survey, ensuring it remains relevant and accurate across different sociocultural and geographical landscapes. To enhance the generalizability of the survey tool, future research should explore its applicability in other geographical regions and cultural contexts. This includes testing the survey in diverse environments to identify any cultural or regional adaptations needed to maintain its relevance and accuracy. Conducting pilot studies in various settings will help refine the survey tool, ensuring it is sensitive to different sociocultural dynamics and governance structures. Moreover, feedback from these pilot studies should be used to iteratively improve the survey, enhancing its applicability and robustness across different contexts.

The development of this survey marks a pivotal advancement in enhancing the comparability of AFCIs. It provides a cohesive and standard framework for understanding the essential elements, stakeholders, and situational dependencies crucial for evaluating AFCs. This characteristic of the Ontario AFCI survey is vital for progressing toward a uniform, evidence-based approach in AFCIs and policy-making.

Limitations

One potential limitation is the risk of confirmation bias, where preconceived notions about AFCIs effectiveness could have influenced the survey design and data interpretation. To counter this, we employed rigorous survey design strategies, member-checking methods, and extensive stakeholder and expert input. However, the ever-changing nature of AFCIs, characterized by frequent updates in initiatives’ staff, leaders, goals, resources, or funding sources, presented challenges in maintaining a consistent sample for longitudinal studies. These challenges could affect the assessment of the survey’s long-term effectiveness and sustainability. Despite these challenges, the survey’s design is iterative, allowing for adjustments to meet specific community needs and characteristics. This adaptability is essential for the survey to remain relevant to AFCIs’ evolving priorities. Despite potential limitations, our study offers valuable insights for AFCI evaluation and establishes a foundation for future research using this reliable and valid survey tool.

Recommendations

It is recommended that the survey’s application expand beyond Ontario, encompassing AFCIs nationally to gain insight into their effectiveness and to further refine the survey and best practices. Using AFCI survey data, comparative analyses are needed between active, discontinued, or unfunded AFCIs, to identify what factors differentiate them and influence their success or challenges. The survey should also be used to evaluate AFCI outcomes over time, focusing on key priorities identified in this study, such as sustainability, subpopulations, and challenges and barriers.

Using the survey to evaluate AFCIs will aid in synthesizing key learnings and drawing informed conclusions, highlighting the critical importance of their initiatives to stakeholders and funding agencies. Survey data can guide strategic planning, resource allocation, and policy formulation to augment the efficacy and long-term viability of AFCIs. Additionally, the results from this study highlight the importance of adopting an iterative methodology in the ongoing development of the survey. It is recommended that annual feedback meetings be held with AFCIs to ensure the survey’s relevance to, and utility for, evaluating the performance and impact of AFCIs.

Conclusion

This study introduces a validated survey that effectively captures the diversity and complexity of AFCIs over time. The development of this survey addresses a significant gap in the existing literature by providing a standardized yet adaptable tool for assessing AFCIs at local, regional, and provincial levels. Key findings from the study reveal that AFCI priorities and outcomes are significantly influenced by local needs, resources, individual experiences, and unique community contexts. The survey’s design allows for a detailed examination of these nuances, offering critical data for local decision-making and strategic planning. The importance of this survey lies in its ability to provide a cohesive framework for evaluating AFCIs, thereby enhancing the comparability of initiatives across different contexts. This characteristic is vital for advancing a uniform, evidence-based approach in AFCI assessment and policy-making. Moreover, the survey’s iterative design ensures its relevance and adaptability to the evolving priorities of AFCIs.

Future research should focus on expanding the application of this survey beyond Ontario to encompass AFCIs nationally. Comparative analyses among active, discontinued, and unfunded AFCIs are needed to identify factors that influence their success or challenges. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to evaluate AFCI outcomes over time, focusing on key priorities such as sustainability, subpopulations, and barriers. Additionally, the survey should be periodically updated based on annual feedback meetings with AFCI stakeholders to ensure its continued relevance and utility. By using this survey, researchers and policy-makers can synthesize key learnings, guide strategic planning, resource allocation, and policy formulation to augment the efficacy and long-term viability of AFCIs. This study establishes a strong foundation for future research and offers a reliable and valid tool for ongoing AFCI evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Sarah Webster, Centre for Studies in Aging and Health, Providence Care Hospital, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Madison Robertson, Centre for Studies in Aging and Health, Providence Care Hospital, Kingston, Ontario, Canada; Health Quality Programs, School of Nursing, Queen’s University, Kington, Ontario, Canada.

Christian Keresztes, School of Community Services, St. Lawrence College, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

John Puxty, Centre for Studies in Aging and Health, Providence Care Hospital, Kingston, Ontario, Canada; Department of Medicine, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Data Availability

This study is not pre-registered. Original data is not available due to IRB and confidentiality concerns. The full survey tool is included in Supplementary Appendix D.

Author Contributions

Sarah Webster (Conceptualization [Supporting], Data curation [Equal], Formal analysis [Supporting], Funding acquisition [Supporting], Investigation [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Project administration [Lead], Resources [Equal], Supervision [Equal], Validation [Equal], Visualization [Supporting], Writing—original draft [Supporting], Writing—review & editing [Equal]); Madison Robertson (Formal analysis [Lead], Methodology [Equal], Resources [Supporting], Validation [Equal], Visualization [Lead], Writing—original draft [Lead], Writing—review & editing [Lead]); Christian Keresztes (Conceptualization [Supporting], Data curation [Equal], Formal analysis [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]); John Puxty (Conceptualization [Lead], Data curation [Equal], Formal analysis [Supporting], Funding acquisition [Lead], Investigation [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Project administration [Supporting], Resources [Equal], Supervision [Equal], Validation [Equal], Visualization [Supporting], Writing—original draft [Supporting], Writing—review & editing [Equal])

References

- Allen, M. S., Robson, D., & Iliescu, D. (2023). Face validity: A critical but ignored component of scale construction in psychological assessment. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 39(3), 153–156. https://doi.org/ 10.1027/1015-5759/a000777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner, S., Pope, D., Mattocks, C., Lafortune, L., Dherani, M., & Bruce, N. (2019). Developing age-friendly cities: An evidence-based evaluation tool. Journal of Population Ageing, 12(2), 203–223. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12062-017-9206-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Studies in Aging and Health (CSAH). (2023a). Age-friendly community initiative in Ontario. Retrieved April 29, 2024 from https://sagelink.ca/age-friendly-communities-ontario/age-friendly-communities/ [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Studies in Aging and Health (CSAH). (2023b). Ontario age-friendly communities outreach program. Retrieved April 29, 2024 fromhttps://sagelink.ca/age-friendly-communities-ontario/ [Google Scholar]

- Dellamora, M. C., Zecevic, A. A., Baxter, D., Cramp, A., Fitzsimmons, D., & Kloseck, M. (2015). Review of assessment tools for baseline and follow-up measurement of age-friendliness. Ageing International, 40(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12126-014-9218-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garner, I. W., & Holland, C. A. (2020). Age-friendliness of living environments from the older person’s viewpoint: Development of the age-friendly environment assessment tool. Age and Ageing, 49(2), 193–198. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ageing/afz146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario. (2021). Creating a more inclusive Ontario: Age-friendly community planning guide for municipalities and community organizations. Retrieved April 23, 2024 fromhttps://files.ontario.ca/msaa-age-friendly-community-planning-guide-municipalities-community-organizations-en-2021-01-01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario. (2022). Aging with confidence: Ontario’s action plan for seniors. Retrieved April 23, 2024 fromhttps://www.ontario.ca/page/aging-confidence-ontario-action-plan-seniors [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, S. N., Richard, D. C. S., & Kubany, E. S. (1995). Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 238–247. https://doi.org/ 10.1037//1040-3590.7.3.238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jhangiani, R. S., Chiang, I.-C. A., Cuttler, C., & Leighton, D. C. (2020). Research methods in psychology (4th ed.). Kwantlen Polytechnic University. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, M., Rosenberg, P. E., & Dalton, S. D. (2018). A global pilot study of age-friendly city indicators. Social Indicators Research, 138(3), 1205–1227. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11205-017-1680-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K., Buckley, T., Burnette, D., Kim, S., & Cho, S. (2022). Measurement indicators of age-friendly communities: Findings from the AARP age-friendly community survey. Gerontologist, 62(1), e17–e27. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/geront/gnab055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1094428108324513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: a practical step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 9(3), 3351–33514. https://doi.org/ 10.62707/aishej.v9i3.335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menec, V. H., & Nowicki, S. (2014). Examining the relationship between communities “age-friendliness” and life satisfaction and self-perceived health in rural Manitoba, Canada. Rural and Remote Health, 14, 2594. https://doi.org/ 10.22605/RRH2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Corporation. (2016). Microsoft Excel (Version 16.0). Retrieved January 22, 2024 from https://www.microsoft.com/en-ca/microsoft-365/excel [Google Scholar]

- Orpana, H., Chawla, M., Gallagher, E., & Escaravage, E. (2016). Developing indicators for evaluation of age-friendly communities in Canada: Process and results. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada : Research, Policy and Practice, 36(10), 214–223. https://doi.org/ 10.24095/hpcdp.36.10.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual 4th edition: A step by step guide to data analysis (4th ed.). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polco. (2020). Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (CASOA). Retrieved April 22, 2024 fromhttps://info.polco.us/community-assessment-survey-for-older-adults [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2016). Age-friendly communities evaluation guide: Using indicators to measure progress. Retrieved March 6, 2024 fromhttps://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/aging-seniors/friendly-communities-evaluation-guide-using-indicators-measure-progress.html [Google Scholar]

- Russell, E., Skinner, M. W., Colibaba, A. (2020). Developing rural insights for building age-friendly communities. Journal of Rural Studies, 81, 336–344. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonenboom, J., & Johnson, R. B. (2017). How to construct mixed methods research design. Abhandlungen, 69, 107–131. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T. A., Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2007). Judging interpretations: But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 2007(114), 11–25. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ev.223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torku, A., Chan, A. P. C., & Yung, E. H. K. (2020). Age-friendly cities and communities: A review and future directions. Ageing and Society, 41(10), 2242–2279. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/s0144686x20000239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Sierra Huertas, D., Rowe, J. W., Finkelstein, R., Carstensen, L. L., & Jackson, R. B. (2021). Rethinking the urban physical environment for century-long lives: From age-friendly to longevity-ready cities. Nature Aging, 1, 1088–1095. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s43587-021-00140-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2008). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. Retrieved January 9, 2024 fromhttps://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547307 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Measuring the age-friendliness of cities: A guide to using core indicators. Retrieved March 6, 2024 from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509695 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). About the global network for age-friendly cities and communities. Retrieved January 9, 2024 fromhttps://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/who-network/ [Google Scholar]

- Zamanzadeh, V., Ghahramanian, A., Rassouli, M., Abbaszadeh, A., Alavi-Majd, H., & Nikanfar, A. (2015). Design and implementation content validity study: Development of an instrument for measuring patient-centered communication. Journal of Caring Sciences, 4(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/ 10.15171/jcs.2015.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlmans, E. A. O., Van der Ark, L. A., Tijmstra, J., & Sijtsma, K. (2018). Methods for estimating item-score reliability. Applied Psychological Measurement, 42, 553–570. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0146621618758290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study is not pre-registered. Original data is not available due to IRB and confidentiality concerns. The full survey tool is included in Supplementary Appendix D.