Summary.

Background:

von Willebrand factor (VWF) has a role in both hemostasis and thrombosis. Platelets adhere to damaged arteries by interactions between the VWF A1-domain and glycoprotein Ib receptors under conditions of high shear. This initial platelet binding event stimulates platelet activation, recruitment, and activation of the clotting cascade, promoting thrombus formation.

Objective:

To characterize the inhibitory activity of a VWF inhibitory aptamer.

Methods:

Using in vitro selection, aptamer stabilization, and conjugation to a 20-kDa poly(ethylene glycol), we generated a nuclease-resistant aptamer, ARC1779, that binds to the VWF A1-domain with high affinity (KD ~ 2 nm). The aptamer was assessed for inhibition of VWF-induced platelet aggregation. In vitro inhibition of platelet adhesion was assessed on collagen-coated slides and injured pig aortic segments. In vivo activity was assessed in a cynomolgus monkey carotid electrical injury thrombosis model.

Results and Conclusion:

ARC1779 inhibited botrocetin-induced platelet aggregation (IC90 ~ 300 nm) and shear force-induced platelet aggregation (IC95 ~ 400 nm). It reduced adhesion of platelets to collagen-coated matrices and formation of platelet thrombi on denuded porcine arteries. ARC1779 also inhibited the formation of occlusive thrombi in cynomolgus monkeys. We have discovered a novel anti-VWF aptamer that could have therapeutic use as an anti-VWF agent in the setting of VWF-mediated thrombosis.

Keywords: aptamer, platelets, thrombosis, von Willebrand factor

Introduction

von Willebrand factor (VWF) has been proposed as a biomarker, a prognostic indicator, and a mediator of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [1–3]. It has been proposed as a mediator of those events because of its causal role in arterial thrombogenesis, as well as a mediator of thrombotic microangiopathies [4,5]. Inhibition of VWF could provide a unique therapeutic opportunity in the treatment of arterial thrombosis. The VWF A1-domain–platelet glycoprotein 1b (GP1b) interaction pathway is independent of other pathways that lead to platelet-rich thrombus formation, such as platelet activation via P2Y12 receptor, and may, in fact, be additive to such inhibition [6]. A VWF antagonist could block the activity of VWF immobilized on the subendothelial matrix (the initial step in this sequence) and the crosslinking of platelets by soluble VWF released into the circulation by shear-activated endothelium [7]. Prevention of VWF binding to GPIb should prevent GPIb-dependent inside-out signaling, thereby blocking thrombin generation [8,9] and the final step in the sequence of platelet activation, upregulation of GPIIb/IIIa [10]. VWF antagonism has been shown to be effective in a variety of other thrombosis models [11–17]. VWF inhibition may also have benefit in microvascular thrombosis, where local release of high molecular weight VWF may promote platelet plug formation.

Here we describe in vitro and in vivo activity of a nucleic acid aptamer, expanding on previous phase I clinical data [18]. The aptamer was isolated using an in vitro selection process known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX), that involved screening 1014 random nucleic acid sequences for binding to both the A1-domain and to intact VWF. More information on SELEX can be found in previous publications [19–23]. ARC1779 is different in structure and activity from a previously reported RNA aptamer for which in vitro data have been reported [24]. Aptamers are nucleic acid molecules with high affinity and specificity for a selected target molecule, with an ability to fold into unique three-dimensional structures that promote target binding. Through chemical modifications and conjugation with a high molecular weight poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) moiety, aptamers are engineered to have a variety of pharmacodynamic characteristics. The aptamer described here, ARC1779, binds to the A1-domain of VWF with high affinity and inhibits VWF-dependent platelet aggregation. ARC1779 is able to inhibit VWF-mediated platelet activation, adhesion and occlusive thrombus formation of the carotid arteries of cynomolgus macaques, with reduced bleeding as compared with the GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor abciximab [25].

Materials and methods

Selection of a VWF aptamer

A cDNA sequence encoding the A1-domain of human VWF in the pDrive vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) was synthesized by dna 2.0 (Menlo Park, CA, USA). The sequence of the A1-domain was identical to that used for crystallographic studies [26–30]. The cDNA was subsequently subcloned into the pRSET expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The A1-domain was expressed in Escherichia coli, refolded, and purified according to published methods [26].

Oligonucleotides were synthesized on either an Expedite 8909 DNA/RNA Synthesizer (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA) (≤ 1-μmol scale) or on an ÄKTA Oligopilot (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) (≥ 1-μmol scale), using standard phosphoramidite solid-phase chemistry. All phosphoramidites were acquired from Chemgenes Corporation (Wilmington, MA, USA). A subset of aptamers was synthesized with a hexylamine moiety at the 5′-end and conjugated to high molecular weight PEGs from Nippon Oil and Fat (White Plains, NY, USA) postsynthetically via amine-reactive chemistry. The resulting products were purified by ion exchange and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography.

A DNA template was synthesized and purified at the 1-μmol scale with the sequence 5′-CTACCTACGATCTGACTAGC-N40-GCTTACTCTCATGTAGTTCC-3′, where ‘N40’ represents a 40-nucleotide sequence in which there is an equal probability of incorporating dA, dT, dG or dC at each position. The template was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the primers 5’-CTACCTACGATCTGACTAGC-3’ and 5’-AGGAACTACATGAGAGTAAGrC-3’, where ‘rC’ represents ‘2′-ribo-C’ (all other positions correspond to standard 2′-deoxynucleotides). The PCR product was then subjected to alkaline hydrolysis to induce strand cleavage at the single 2′-ribonucleotide, and purified using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to generate single-stranded DNA for the selection experiments [31].

During selection, 24 pmol of human VWF (EMD Biosciences/Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) and (early cycles)/or (later cycles) VWF A1-domain were immobilized in the same well of a Maxisorp hydrophobic plate (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA). The protein-immobilized well was blocked with 100 μL of blocking buffer [Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)]. Material bound to the immobilized protein target was eluted with a denaturing buffer preheated to 90 °C (7 m urea, 100 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.3, 3 mm EDTA). Elution fractions were pooled, precipitated with ethanol, amplified by PCR, and purified as described above. PCR products from the end of the selection were cloned and sequenced.

Aptamers were 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA, USA), following standard protocols. Aptamers were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in 30 μL of Dulbecco’s PBS containing 0.1 mg mL−1 BSA and either human VWF or the VWF A1-domain. Bound complexes were separated from free DNA using an acrylic mini-dot blot apparatus (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH, USA) and a membrane sandwich (top to bottom) of Protran BA85 0.45 μm Nitrocellulose Membrane (Schleicher and Schuell), Hybond P Nylon Membrane (Amersham), and 3MM filter paper (Whatman, Florham Park, NJ, USA), all prewetted with Dulbecco’s PBS. Radioactivity associated with protein–DNA complexes (nitrocellulose) and free DNA (nylon) was quantified on a Storm 860 Phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics/Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Binding constants were determined by fitting the fraction of aptamer bound as a function of the concentration of VWF.

Platelet function assays

Blood was drawn into 0.105 m sodium citrate by venipuncture from eight healthy donors who had not taken non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than aspirin for at least 3 days. Donors who had taken aspirin were not used. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-poor plasma (PPP) were prepared from the collected blood by centrifugation at 120 g for 20 min (PRP) and 1000 g for 14 min (PPP), respectively. PRP was aliquoted into cuvettes containing stir bars at a volume of 470 μL. A sample of 500 μL of PPP was aliquoted into a cuvette and placed in the PPP reference cell of a Model 490-4D platelet aggregometer (Chronolog, Havertown, PA, USA). Samples of PRP were prewarmed at 37 °C in the platelet aggregometer for 3–5 min before being used in aggregation assays. For botrocetin-induced platelet aggregation (BIPA) reactions, 1.5 U of botrocetin was used per 500-μL reaction [botrocetin 100 Units/vial, lyophilized powder made by Pentapharm (Basel, Switzerland) and supplied by Centerchem (Norwalk, CT, USA)]. ARC1779 was assayed by diluting increasing concentrations of aptamer into prewarmed PRP, incubating the mixture for 1 min, and then adding botrocetin. Botrocetin was used in these assays because ristocetin was found to interfere with the interaction of the aptamer with VWF. The platelet aggregometer monitored changes in light transmission over 6 min after addition of the agonist. The effect of a high ARC1779 concentration (10 μm) on aggregation induced by ADP (10 μm), collagen (2 μg mL−1), thrombin (0.25 U mL−1), epinephrine (10 μm) and arachidonic acid (5 mm) was also assessed. Data were analyzed using Chronolog Corporation’s software, [aggro/link rev. 5.2.1.

A Platelet Function Analyzer 100 (PFA-100) (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL, USA) was used to assay the shear force-dependent anti-VWF activity of aptamers in whole blood. Test article or vehicle was added to citrated whole blood from three healthy volunteers and was assayed for anti-VWF activity by using collagen/epinephrine cartridges according the manufacturer’s protocols. Inhibition of shear force-dependent platelet function was correlated with the time to occlusion of the cartridge aperture with a maximum measurable time of 300 s. Two replicates were performed for each donor. IC50 and IC90 values were determined using the XLFIT 4.1 plug-in for Excel.

Adhesion of platelets to collagen-associated VWF

A parallel plate with a 0.0127-cm silicon rubber gasket (Glycotech, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) coated with 100 μg mL−1 collagen (Nycomed, Munich, Germany) was used. A 20-mL blood sample was collected from healthy donors into 90 μm PPACK. Washed platelets were obtained from 10 mL of blood, labeled with 2.5 μg mL−1 calcein orange, and then added back to the whole blood. Blood was treated with various concentrations of ARC1779 at 37 °C (25–400 nm). In addition, a randomly synthesized 40-nucleotide aptamer was also assessed at a concentration of 400 nm. Platelet adhesion was monitored with an Axiovert 135 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) at × 32 and a silicon-intensified tube camera C 2400 (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan). Adhesion was analyzed with Image SXM 1.62 (NIH Image, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image).

Thrombus formation on injured porcine arteries

A 120-mL sample of venous blood from normal volunteers (n = 5) was anticoagulated with PPACK (90 mL) or acid–citrate–dextrose (ACD) (30 mL). The ACD blood was used to isolate and radiolabel platelets with 111In and resuspended in the remaining 90 mL of the PPACK blood. Porcine aorta segments were isolated, dissected free of surrounding tissues, cut into rings, and opened longitudinally. Injured segments were prepared by lifting and peeling off the intima to expose the subjacent media. The segments were placed into Badiman perfusion chambers with a 1-mm internal diameter. The chambers were placed in parallel (two per side) in a thermostatically controlled water bath (at 37 °C), thus permitting simultaneous parallel, pairwise perfusion over arterial tissues of treated or untreated blood at high shear (6974 s−1 in 1-mm internal diameter chambers). Blood, containing the 111In-labeled platelets, was perfused and recirculated over the arterial segments for 15 min without (control) or with abciximab (ReoPro; Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA) (100 nm), or ARC1779 (150 nm, 600 nm, or 1.5 μm). At the end of the perfusion, the surfaces were immediately fixed and counted in a gamma counter to calculate the level of platelet adhesion, and this was followed by scanning electron microscopy examination of the luminal surfaces.

Electrical injury model of arterial thrombosis

The electrical injury model of arterial thrombosis was used on 23 cynomolgus macaques according to the methods of Rote et al. [25] as described below. Each animal was anesthetized prior to surgical preparation, intubated, and maintained in anesthesia with isoflurane inhalant anesthetic. An intravenous catheter was placed in a peripheral vein for administration of lactated Ringer’s solution during the procedure. Catheters were placed in the femoral artery of each animal to allow continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure, and in the femoral vein for blood sample collection. Doppler flow probes were placed around the artery at a point proximal to the insertion of the intra-arterial electrode and stenosis. A stenosis was produced in each carotid artery to reduce blood flow by approximately 50–60%, using a flow constrictor cuff. Blood flow in the carotid arteries was monitored and recorded continuously throughout the observation periods.

Electrolytic injury to the intimal surface of each carotid artery was accomplished via a continuous current delivered to each vessel via an intravascular electrode for a period of 3 h or for 30 min after complete occlusion, whichever was shorter. Control animals received a saline injection and infusion for 6 h. Four aptamer doses ranging from a 100 μg kg−1 bolus and 1 μg kg−1 min−1 infusion to a 600 μg kg−1 bolus and 3.7 μg kg−1 min−1 infusion were evaluated in a total of 15 animals. The GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor abciximab, used as the positive control, was administered as a 250 μg kg−1 intravenous bolus followed by a 0.125 μg kg−1 min−1 infusion. Approximately 15 min after test article administration, the electric current was applied at 100 μA. The current was terminated either ~ 30 min after the blood flow signal remained stable at zero flow (indicating the formation of an occlusive thrombus at the site) or after 180 min of electrical stimulation without occlusion, whichever occurred first. Approximately 195 min after onset of the test article infusion, the left carotid artery was subjected to electrical injury in a similar fashion. Template bleeding time was also assessed in this model using a Surgicutt Automated Incision Device (ITC, Edison, NJ, USA). A longitudinal incision was made over the lateral aspect of the volar surface of the forearm. At 15–30 s post-incision, the blood was wicked with Surgicutt Bleeding Time Blotting Paper while avoiding direct contact with the incision. The blotting paper was rotated and reblotted at a fresh site on the paper every 15–30 s. The blotting was repeated until blood no longer wicked onto the paper or for 15 min, whichever came first. In cases where bleeding time would have exceeded 15 min, the wound was closed with a suture. Bleeding time was determined to within 30 s of the time when blood no longer wicked onto the paper. In addition, special attention was paid to the various surgical incision sites on all animals for continued bleeding during the experimental procedures.

Animal experimentation

All animal experiments in this study were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Charles River Laboratories and Montreal Heart Institute. Every effort was made to ensure minimal discomfort in the animal procedures performed in this study.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a non-parametric one-way anova (Kruskal–Wallis test) followed by Dunn’s test, using the program GraphPad InStat version 3.05 for Windows 95/NT (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). anova (Kruskal–Wallis) plus the Mann–Whitney test was used in cases of comparison between two groups. Prism 4.0b for Mac (Graphpad Software) was used for the platelet adhesion on collagen studies.

Results

Selection of a VWF aptamer by SELEX

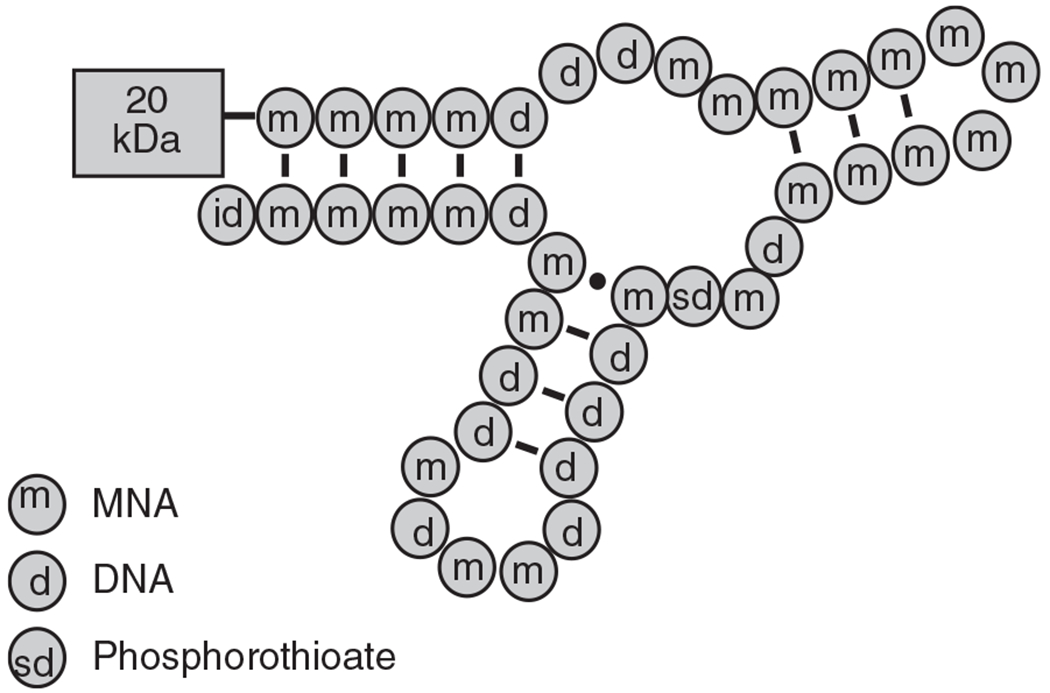

In successive cycles of SELEX, the protein target was alternated between full-length human VWF and the isolated VWF A1-domain. We anticipated that this strategy would facilitate the identification of aptamers that bound to the A1-domain in full-length VWF and neutralize the VWF–GP1b interaction. The dominant sequence family did bind to both full-length human VWF and the recombinant VWF A1-domain with high affinity. A medicinal chemistry approach to maintain and/or improve several key physical properties (affinity, potency, serum nuclease stability) of the compound were performed. We substituted 2′-methoxynucleosides for 2′-deoxynucleosides at each position to determine which residues tolerated substitution. Methoxyuridine was substituted for deoxythymidine in all cases. A series of individual phosphate-to-phosphorothioate substitutions were tested in the context of the most potent/most highly modified 2′-methoxy/2′-deoxy aptamers. This resulted in a final aptamer (ARC1779) that is a 40-nucleotide modified DNA/RNA oligonucleotide with a KD of 2 nm for the A1-domain. It is composed of 13 unmodified 2′-deoxynucleotides, 26 modified 2′-O-methyl-nucleotides (to minimize endonuclease digestion), one inverted deoxythymidine (id) nucleotide as a 3′-terminus ‘cap’ (to minimize 3′-exonuclease digestion), and a single phosphorothioate (P=S) linkage between nucleotide positions mG20 and dT21 (enhanced affinity for VWF). The core 40-mer is synthesized with a hexylamine at the 5′-terminus as a reactive site for subsequent conjugation of a 20-kDa PEG moiety to reduce the renal clearance of the 13-kDa aptamer. A proposed structure, derived from an Archemix folding program, is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed secondary structure of ARC1779. The pegylation at the 5′-end is indicated by 20 kDa PEG. Deoxynucleotides, 2′-O-methyl modified RNA nucleotides and the phosphorothioate linkages are indicated by d, m and sd respectively. The id indicates the inverted deoxythymidine at the 3′-end.

Platelet function assays

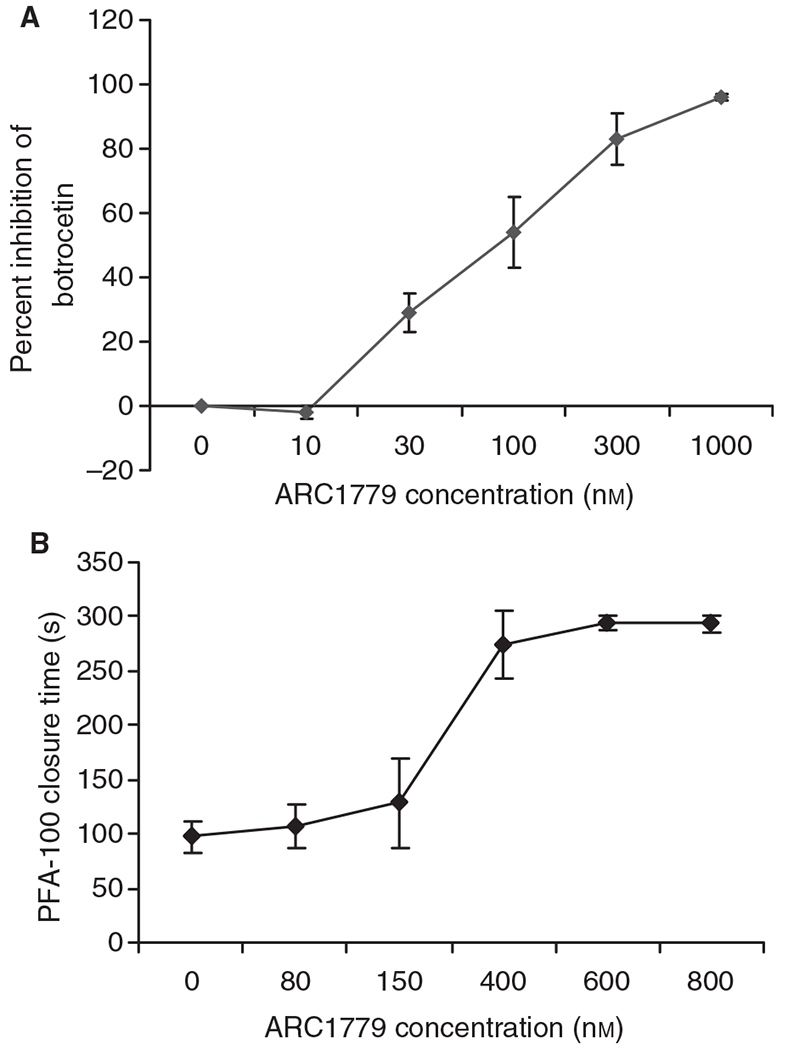

Two assays were used to test the ability of aptamers to neutralize VWF-dependent platelet activation. The first assay was the BIPA assay [32]. The second measure of aptamer functional activity was with the PFA-100, which simulates the formation of a hemostatic plug under conditions of high shear force in vivo by recording the time required for platelets to aggregate and block the flow of blood through an aperture in a membrane coated with collagen and epinephrine or ADP. Unlike BIPA, the PFA-100 assay is botrocetin-independent and rules out the formal possibility that the aptamer merely inhibits the ability of botrocetin to bind to VWF. As shown in Fig. 2, ARC1779 inhibits VWF-dependent platelet aggregation as measured by inhibition of BIPA and PFA-100 closure time. ARC1779 at 10 μm did not inhibit aggregation induced by ADP, collagen, thrombin, epinephrine, or arachidonic acid (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

ARC1779 inhibits von Willebrand factor-dependent platelet activation as assayed using botrocetin-induced platelet aggregation and the Platelet Function Analyzer 100 (PFA-100) platelet function analyzer. (A) The botrocetin aggregation curve for a concentration range of ARC179 from 0 to 1000 nm (n = 8, mean ± standard error of the mean). The calculated ARC1779 IC90 concentration was 344 nm. (B) The aperture occlusion time of citrated whole blood measured in the PFA-100. Three hundred seconds is the maximum time that can be measured, and indicates complete inhibition. The PFA-100 values represent the mean ± standard error of the mean of two replicates from three donors for each concentration.

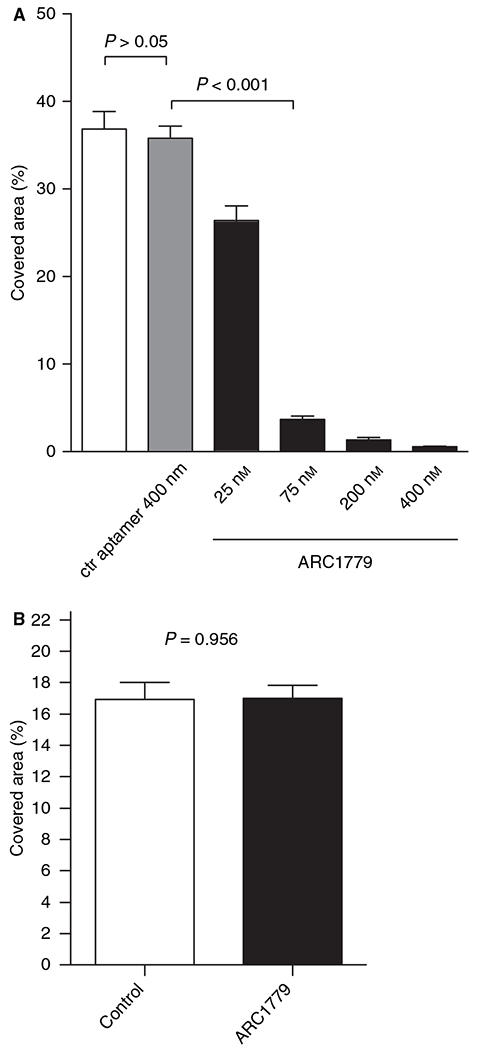

Adhesion of platelets to collagen-associated VWF

Binding of fluorescently labeled platelets to a collagen-coated surface was measured in the absence and presence of ARC1779. The percentage area with fluorescent platelets was quantified after 2 min of blood flow at a shear rate of 1500 s−1. Approximately 40% of the surface was covered with adherent platelets in the control group. The lowest concentration of ARC1779 tested (25 nm) reduced the covered surface area by ~ 30%. Higher concentrations of 75–400 nm reduced the covered area by > 90% (Fig. 3A). A control random sequence 40-nucleotide aptamer at 400 nm had no effect on platelet accumulation. ARC1779 at 400 nm did not significantly reduce the adhesion of platelets to the collagen-coated slides at a shear rate of 150 s−1 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

ARC1779 inhibits platelet adhesion at high shear rates. (A) Human whole blood with labeled platelets was perfused over immobilized collagen at an arterial shear rate of 1500 s−1. Quantification of the fluorescently covered area after 2 min showed significantly reduced platelet adhesion with increasing ARC179 concentrations, whereas the scrambled aptamer did not reduce platelet adhesion (n = 8). ctr, control. (B) Platelet adhesion was not inhibited at a concentration of 400 nm ARC1779 at low shear rates of 150 s−1 as compared with control. The total adhesion area was < 50% of that seen under high shear flow; n = 20 flow measurements from three donor samples.

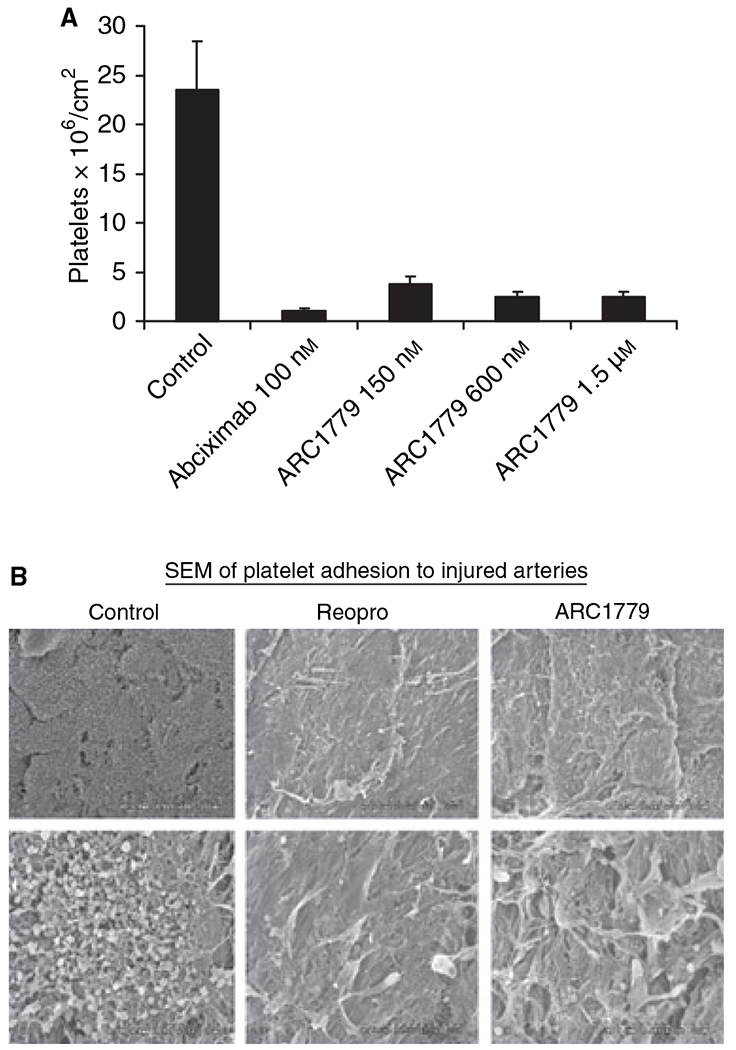

Thrombus formation on injured porcine arteries

Human whole blood was perfused over injured porcine arteries for 15 min at a shear rate of 6974 s−1. Quantitation of platelet accumulation with labeled platelets demonstrated that abciximab-treated blood (100 nm) and ARC1779-treated blood (150 nm, 600 nm, and 1.5 μm) had a significant reduction of platelet accumulation on the injured artery surface (Fig. 4A). This was confirmed by scanning electron microscopy of the artery surface. Untreated samples had significant platelet accumulation and thrombus formation, whereas there were few platelets adherent to the injured surface of either the abciximab or ARC1779 arteries (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Platelet adhesion on damaged porcine aorta under high shear. (A) Human whole blood was perfused over injured porcine arteries for 15 min at a 6974 s−1 shear rate. Untreated samples had significant platelet accumulation, whereas abciximab-treated blood (100 nm) and ARC1779-treated blood (150 nm, 600 nm, and 1.5 μm) both had a reduction of platelet accumulation on the injured artery surface [n = 5 for each group, mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM)]. (B) Scanning electron micrograph showing low (upper panels, × 500 magnification) and high (lower panels, × 2500 magnification) magnifications of representative aortic segments. The abciximab-treated and the ARC1779-treated blood samples both had much less platelet adhesion to the injured surface than the control untreated blood.

Efficacy in an electrical injury model of arterial thrombosis

We established the pharmacodynamic relationship with plasma concentration for ARC1779 in the cynomolgus monkey prior to initiating the electrical injury efficacy study. Dosing cynomolgus macaques at 0.5 mg kg−1 achieved a plasma Cmax of ~ 1 μm (~ 13 μg mL1). A plasma level of ARC1779 above 100 nm (~ 1.3 μg mL−1) completely inhibited (300-s closure time) VWF-dependent platelet activity as assessed by PFA-100 closure time. At plasma levels below 100 nm, the anti-VWF effect rapidly returned to baseline levels. These data provided the information necessary to calculate the infusion rates to evaluate a dose response in the cynomolgus monkey electrical injury-induced thrombosis model.

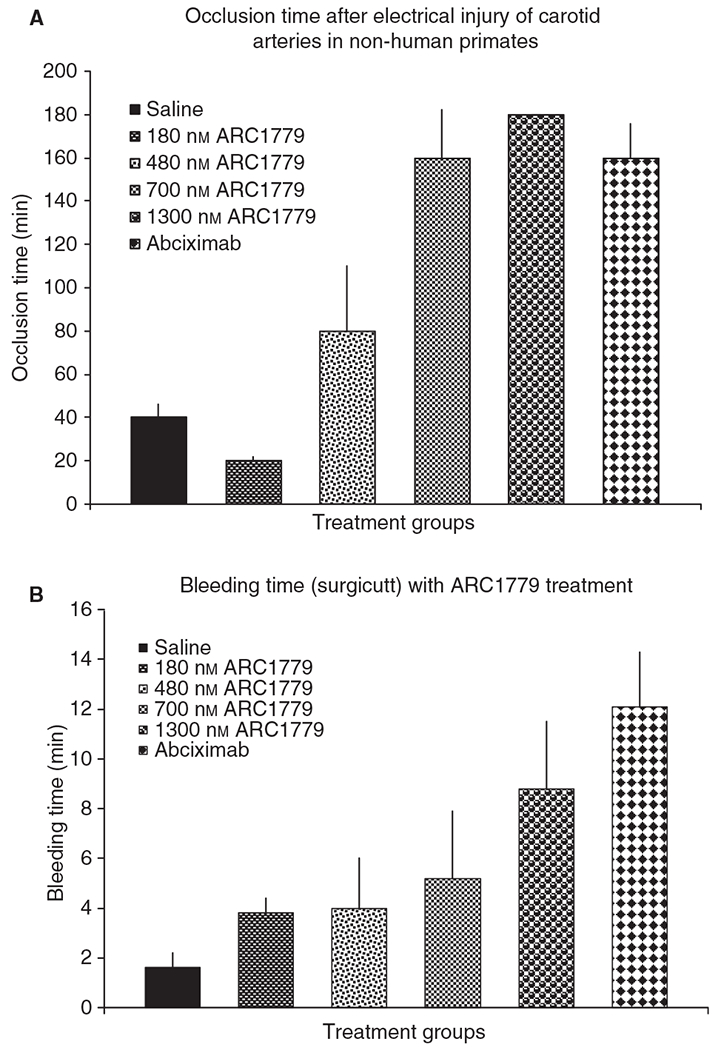

ARC1779 showed clear dose-dependent efficacy in cynomolgus macaque model of electrical injury (Fig. 5A). With an intravenous bolus + infusion regimen that achieved mean plasma concentrations between 180 nm (2.3 μg mL−1) and 1300 nm (17 μg mL−1), ARC1779 demonstrated efficacy comparable to that of a therapeutic dose regimen of abciximab. ARC1779-treated animals did not exhibit occlusion of blood flow at concentrations of 700 nm (9.1 μg mL−1) and 1300 nm (17 μg mL−1) (Fig. 5A). These data suggest that 700 nm is a pharmacologically effective target plasma concentration for ARC1779 in this model. Consistent with the dose-dependent efficacy of ARC1779 in the model, there was also a dose-dependent increase in template bleeding time that was 4.0 ± 1.9 min and 5.2 ± 2.7 min for the 480 nm and 700 nm plasma concentration groups, respectively (Fig. 5B). However, even at the highest plasma concentration of ARC1779 (1300 nm), with a bleeding time of 8.8 ± 2.7 min, there was no bleeding noted at the incision sites, and only seven of 24 bleeding time points evaluated were > 15 min. Abciximab-treated animals had both increased template bleeding (12.4 ± 2.2 min; 13 of 20 bleeding time points evaluated were > 15 min) and continued bleeding of the incision sites throughout the experimental period.

Fig. 5.

ARC1779 efficacy in a model of occlusive thrombus formation. (A) The average time to vessel occlusion (± standard error of the mean) in the electrical injury model of arterial thrombosis in cynomolgus macaques. The overall P-value for the dataset was < 0.0001. The P-value for the 700 nm ARC1779 and abciximab groups vs. saline was < 0.05. Saline group, n = 3; ARC1779 180 nm, n = 2; ARC1779 480 nm, n = 3; ARC1779 700 nm, n = 4; ARC179 1300 nm, n = 5; abciximab, n = 5. The P-value for the 1300 nm ARC1779 and abciximab groups vs. the saline group was < 0.01. (B) The average template bleeding time during the 6-h infusion (± standard error of the mean). The overall P-value for the dataset was < 0.0001. Only the 1300 nm ARC1779 and abciximab groups had statistically significant P-values when compared with the saline group (< 0.001 in both cases).

Discussion

We report on a novel anti-VWF aptamer that binds to VWF, inhibits the interaction between the VWF A1-domain and the platelet receptor GPIb, and inhibits VWF-dependent platelet activation. Platelet adhesion to both collagen-coated plates and to de-endothelialized arteries was reduced under high-shear conditions in the presence of ARC1779. A scrambled aptamer that did not bind to VWF had no effect on platelet adhesion to collagen-coated plates under high shear flow. Under low-shear conditions, platelet accumulation on collagen-coated plates was approximately 50% of that under high shear flow. ARC1779 did not reduce this accumulation. Other surface receptors, such as GPVI and α2β1, also mediate platelet adhesion to collagen [33,34] and may account for this low-shear platelet adhesion. The fact that ARC1779 does not inhibit low-shear platelet adhesion and appeared to have less effect on platelet adhesion to de-endothelialized arteries may account for the lower bleeding times and better hemostasis seen in the non-human primate thrombosis model. The smaller effect of ARC1779 in the porcine artery studies might also have been a result of the inability of the aptamer to inhibit porcine VWF (J.L. Diener, H.A. Daniel Lagassé, unpublished data). Porcine VWF has been reported to be highly reactive to human platelets [35,36] and would be expected to be enriched in the subendothelium of the arteries used in this study. Under such conditions, ARC1779 would inhibit the platelet accumulation associated with adhesion to the human VWF that adhered to the exposed subendothelium but would have no effect on human platelet adhesion to porcine VWF localized in the artery subendothelium. It has been speculated that, given the difference in mechanism of action, VWF antagonists may offer intrinsic advantages over GPIIb/IIIa antagonists with respect to therapeutic ratio and bleeding risk [6,18,33]. However, the earlier anti-VWF compounds, AJW200 and GPG-290, were not tested in the more stringent primate model of electrical injury-induced arterial thrombosis utilized here and previously used in the proof-of-concept study for abciximab [6,14–17,25], which entails 3 h of continuous electrical injury to the vessel wall. Bleeding times were lower at doses of ARC1779 that were as effective as abciximab in reducing time to thrombosis. Incision and venipuncture sites continued to bleed in the abciximab-treated animals, whereas no bleeding was observed in any of the ARC1779-treated animals. The pharmacokinetic profile of ARC1779 could also be an advantage in terms of bleeding risk. Although the data are not presented in this article, in humans ARC1779 has a short mean residence time of ~ 3 h and a rapid reversal of A1 inhibition [18]. Abciximab, on the other hand, causes long (24–48 h) functional inhibition of GPIIb/IIIa receptors, owing to its high affinity [25,33].

In conclusion, ARC1779 achieved antithrombotic potency at least equal to that of abciximab. Template bleeding times increased with doses of ARC1779, but there was no bleeding from surgical incision sites as compared with abciximab. These properties, in addition to the demonstration of safety in a phase I clinical study in normal volunteers [33], may make it suitable for clinical development as an anti-VWF agent to be used in the acute coronary care setting, in patients with unstable carotid lesions prior to and following endarterectomy procedures, and in peripheral vascular diseases complicated by arterial thrombosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank A. Makim, S. Lewis and T. McCauley for pharmacokinetic support, P. Wagner and M. Gilbert for assay support, and R. Boomer and J. Fraone for compound synthesis. This work was supported in part by a National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health grant HL095091 to D. D. Wagner and R. Schaub.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

J. L. Diener, H. A. Daniel Lagassé, R. Hutabarat, J. Gilbert and R. Schaub are or were employees of Archemix. The work reported by D. Duerschmied, Y. Merhi, J-F. Tanguay and D. D. Wagner was supported by grants from Archemix.

References

- 1.Montalescot G, Philippe F, Ankri A, Vicaut E, Bearez E, Poulard JE, Carrie D, Flammang D, Dutoit A, Carayon A, Jardel C, Chevrot M, Bastard JP, Bigonzi F, Thomas D. Early increase of von Willebrand factor predicts adverse outcome in unstable coronary artery disease: beneficial effects of enoxaparin. French Investigators of the ESSENCE Trial. Circulation 1998; 98: 294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collet JP, Montalescot G, Vicaut E, Ankri A, Walylo F, Lesty C, Choussat R, Beygui F, Borentain M, Vignolles N, Thomas D. Acute release of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction predicts mortality. Circulation 2003; 108: 391–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray KK, Morrow DA, Gibson CM, Murphy S, Antman EM, Braunwald E. Predictors of the rise in VWF after ST elevation myocardial infarction: implications for treatment strategies and clinical outcome: an ENTIRE-TIMI 23 substudy. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker RC. The investigation of biomarkers in cardiovascular disease: time for a coordinated, international effort. Eur Heart J 2005; 26:421–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desch K, Motto D. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in humans and mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007; 27: 1901–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hennan J, Swillo R, Morgan G, Leik C, Brooks J, Shaw G, Schaub R, Crandall D, Vlasuk G. Pharmacologic inhibition of platelet VWF–GPIb alpha interaction prevents coronary artery thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2006; 95: 469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell MJ, Westein E, Nesbitt WS, Giuliano S, Dopheide SM, Jackson SP. Identification of a 2-stage platelet aggregation process mediating shear-dependent thrombus formation. Blood 2007; 109: 566–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kageyama S, Yamamoto H, Nakazawa H, Matsushita J, Kouyama T, Gonsho A, Ikeda Y, Yoshimoto R. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of AJW200, a humanized monoclonal antibody to von Willebrand factor, in monkeys. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002; 22: 187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pontiggia L, Steiner B, Ulrichts H, Deckmyn H, Forestier M, Beer JH. Platelet microparticle formation and thrombin generation under high shear are effectively suppressed by a monoclonal antibody against GPIba. Thromb Haemost 2006; 96: 774–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Fitzgerald ME, Berndt MC, Jackson CW, Gartner TK. Bruton tyrosine kinase is essential for botrocetin/VWF-induced signaling and GPIb-dependent thrombus formation in vivo. Blood 2006; 108: 2596–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellinger DA, Nichols TC, Read MS, Reddick RL, Lamb MA, Brinkhous KM, Evatt BL, Griggs TR. Prevention of occlusive coronary artery thrombosis by a murine monoclonal antibody to porcine von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987; 84: 8100–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGhie AI, McNatt J, Ezov N, Cui K, Lowell K, Mower LK, Hagay Y, Buja LM, Garfinkel LI, Gorecki M, Willerson JT. Abolition of cyclic flow variations in stenosed, endothelium-injured coronary arteries in nonhuman primates with a peptide fragment (VCL) derived from human plasma von Willebrand factor–glycoprotein Ib binding domain. Circulation 1994; 90: 2976–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao S, Ober J, Garfinkel LI, Hagay Y, Ezov N, Ferguson JJ, Anderson HV, Panet A, Gorecki M, Buja ML, Willerson JT. Blockade of platelet membrane glycoprotein Ib receptors delays intracoronary thrombogenesis, enhances thrombolysis, and delays coronary artery reocclusion in dogs. Circulation 1994; 89: 2822–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kageyama S, Matsushita J, Yamamoto H. Effect of a humanized monoclonal antibody to von Willebrand factor in a canine model of coronary arterial thrombosis. Eur J Pharmacol 2002; 443: 143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kageyama S, Yamamoto H, Nagano M, Arisaka H, Kayahara T, Yoshimoto R. Anti-thrombotic effects and bleeding risk of AJvW-2, a monoclonal antibody against human von Willebrand factor. Br J Pharmacol 1997; 122: 165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kageyama S, Yamamoto H, Nakazawa H, Yoshimoto R. Anti-human VWF monoclonal antibody, AJvW-2 Fab, inhibits repetitive coronary artery thrombosis without bleeding time prolongation in dogs. Thromb Res 2001; 101: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kageyama S, Yamamoto H, Yoshimoto R. Anti-human von Willebrand factor monoclonal antibody AJvW-2 prevents thrombus deposition and neointima formation after balloon injury in guinea pigs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000; 20: 2303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert JC, DeFeo-Fraulini T, Hutabarat RM, Horvath CJ, Merlino PG, Marsh HN, Healy JM, Boufakhreddine S, Holohan TV, Schaub RG. First-in-human evaluation of anti von Willebrand factor therapeutic aptamer ARC1779 in healthy volunteers. Circulation 2007; 116: 2678–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ. Selection of single-stranded DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin. Nature 1992; 355: 564–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold L. The SELEX process: a surprising source of therapeutic and diagnostic compounds. Harvey Lect 1995; 91: 47–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joyce GF. In vitro evolution of nucleic acids. Curr Opin Struct Biol 1994; 4: 331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klug SJ, Famulok M. All you wanted to know about SELEX. Mol Biol Rep 1994; 20: 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider D, Tuerk C, Gold L. Selection of high affinity RNA ligands to the bacteriophage R17 coat protein. J Mol Biol 1992; 228: 862–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oney S, Nimjee SM, Layzer J, Que-Gewirth N, Ginsburg D, Becker RC, Arepally G, Sullenger BA. Antidote-controlled platelet inhibition targeting von Willebrand factor with aptamers. Oligonucleotides 2007; 17: 265–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rote WE, Nedelman MA, Mu DX, Manley PJ, Weisman H, Cunningham MR, Lucchesi BR. Chimeric 7E3 prevents carotid artery thrombosis in cynomolgus monkeys. Stroke 1994; 25: 1223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emsley J, Cruz M, Handin R, Liddington R. Crystal structure of the von Willebrand factor A1 domain and implications for the binding of platelet glycoprotein Ib. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 10396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huizinga EG, Tsuji S, Romijn RA, Schiphorst ME, de Groot PG, Sixma JJ, Gros P. Structures of glycoprotein Ib alpha and its complex with von Willebrand factor A1 domain. Science 2002; 297: 1176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porter C, Goodman M, Stanhope M. Evidence on mammalian phylogeny from sequences of exon 28 of the von Willebrand factor gene. Mol Phylogenet Evol 1996; 5: 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varughese KI, Celikel R, Ruggeri ZM. Structure and function of the von Willebrand factor A1 domain. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2002; 3: 30112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumas JJ, Kumar R, McDonagh T, Sullivan F, Stahl ML, Somers WS, Mosyak L. Crystal structure of the wild-type von Willebrand factor A1-glycoprotein Ib alpha complex reveals conformation differences with a complex bearing von Willebrand disease mutations. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 23327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silveira MH, Orgel LE. PCR with detachable primers. Nucleic Acids Res 1995; 23: 1083–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukuda K, Doggett T, Laurenzi IJ, Liddington RC, Diacovo TG. The snake venom protein botrocetin acts as a biological brace to promote dysfunctional platelet aggregation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005; 12: 152–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Meyer SF, Vanhoorelbeke K, Ulrichts H, Staelens S, Feys HB, Salles I, Fontayne A, Deckmyn H. Development of monoclonal antibodies that inhibit platelet adhesion or aggregation as potential anti-thrombotic drugs. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets 2006; 6: 191–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanhoorelbeke K, Ulrichts H, Schoolmeester A, Deckmyn H. Inhibition of platelet adhesion to collagen as a new target for antithrombotic drugs. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord 2003; 3: 125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griggs TR, Webster WP, Cooper HA, Wagner RH, Brinkhous KM. von Willebrand factor: gene dosage relationships and transfusion response in bleeder swine – a new bioassay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1974; 71: 2087–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bahnak BR, Lavergne JM, Ferreira V, Kerbiriou-Nabias D, Meyer D. Comparison of the primary structure of the functional domains of human and porcine von Willebrand factor that mediate platelet adhesion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992; 182: 561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]