Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study is to identify risk factors for the prognosis and survival of synchronous colorectal cancer and to create and validate a functional Nomogram for predicting cancer-specific survival in patients with synchronous colorectal cancer.

Methods

Synchronous colorectal cancers cases were retrieved from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database retrospectively, then they were randomly divided into training (n = 3371) and internal validation (n = 1440) sets, and a set of 100 patients from our group was used as external validation. Risk factors for synchronous colorectal cancer were determined using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, and two Nomograms were established to forecast the overall survival and cancer-specific survival, respectively. We assessed the Nomogram performance in terms of discrimination and calibration. Bootstrap resampling was used as an internal verification method, and we select external data from our hospital as independent validation sets.

Results

Two Nomograms are established to predict the overall survival and cancer-specific survival. In OS Nomogram, sex, age, marital status, ttumor pathological grade, AJCC TNM stage, preoperative serum CEA level, LODDS, radiotherapy and chemotherapy were determined as prognostic factors. In CSS Nomogram, age and marital status, AJCC TNM stage, tumor pathological grade, preoperative serum CEA level, LODDS, radiotherapy and chemotherapy were determined as prognostic factors.The C-indexes for the forecast of overall survival were 0.70, and the C-index was 0.68 for the training and internal validation cohort, respectively. The C-indexes for the forecast of cancer-specific survival were 0.75, and the C-index was 0.74 for the training and internal validation cohort, respectively. The Nomogram calibration curves showed no significant deviation from the reference line, indicating a good level of calibration. Both C-index and calibration curves indicated noticeable performance of newly established Nomograms.

Conclusions

Those Nomograms with risk rating system can identify high risk patients who require more aggressive therapeutic intervention and longer and more frequent follow-up scheme, demonstrated prognostic efficiency.

Keywords: Synchronous colorectal cancers, Nomogram, Overall survival, Cancer-specific survival, SEER

Background

Colorectal cancer ranks the second lethal and the third most prevalent diagnosed cancer worldwide. The annual incidence is around 1.4 million and there are almost 700 000 deaths worldwide [1, 2]. Synchronous colorectal cancers refer to more than one primary cancer discovered in a single patient at initial presentation, account of about 3.2% incidence of all colorectal carcinoma, which are a special and rarer type of colorectal malignancy compared to solitary tumors [3, 4]. The Warren and Gates criteria were established to clinically diagnose SCRCs [5] on the basis of pathological findings in CRC biopsies. These criteria include the following key elements: (1) each tumor of patient must be definitely malignant in pathology; (2) the two tumor lesions must be distinct; (3) the possibility that one lesion is a metastasis from the other tumor must be absolutely ruled out; (4) the synchronous lesion must have been diagnosed at the same time or within 6 months from the time of initial diagnosis [6].

Previous research has shown that synchronous colorectal cancers (SCRCs)—defined as two or more colorectal tumours presenting—exhibits distinct clinicopathological features compared to solitary colorectal cancer. SCRCs appear to have exact distinctions with solitary tumors in terms of surgical management, pathological type, primary locations and microsatellite instability. These differences suggest that the management and treatment of SCRCs may require a different approach compared to solitary colorectal cancer [7–9]. With respect to survival time, it is interesting to note that synchronous cancer patients and solitary cancer patients have shown similar survival rates in most studies [10–17]. However, one study has shown poorer survival rates in synchronous cases [18], which may suggest the need for more aggressive treatment strategies or closer follow-up care for SCRCs patients. Due to the distinct clinicopathological features and survival patterns of SCRCs compared to solitary cancer, it is important to recognize that the prognostic Nomograms of colorectal cancer published previously may not be applicable or suitable for SCRCs patients. Therefore, the development of specialized prognostic Nomograms specific to SCRCs is necessary to provide more accurate risk stratification and treatment planning for this unique patient population. It is widely acknowledged that the Tumour-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging system, as put out by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), is regarded as a classic reference standard by many clinicians in the treatment and prognostic interventions for colorectal cancer. This system has been widely recognized and adopted as the gold standard for staging colorectal cancer patients, taking into account the tumour burden, nodal status, and presence of metastasis.

Furthermore, the status of lymph nodes (pN stage) is considered to be the most important prognostic prediction factor [19]. The number of lymph nodes examined is associated with a survival benefit for both node negative and node-positive colorectal cancer patients. However, the efficacy of pN stage is compromised when the number of retrieved lymph node is inadequate. The log odds ratio of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) is a novel prognosis indicator, defined as the logarithm of the ratio of the number of positive lymph nodes (PLNs) to the number of negative lymph nodes (NLNs), which is considered a valuable prognostic factor in patients with colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, and lung cancer and has no limitations in terms of the number of lymph nodes excised [20–27].

Hitherto, there is few knowledge and judge tools concerning the clinical-applied prediction of SCRCs. Given the special characteristics mentioned above, a more comprehensive and specific tool to predict the prognosis of SCRCs is needed. Hereby, we constructed SCRCs-specific Nomograms based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, validated the performance of those Nomograms and compared with the AJCC TNM staging system.

Patients and methods

Population selection

Clinical variables for SCRC patients were extracted from the SEER database (http://seer.cancer.gov/) between 2000 and 2022, an open-access program established by the National Cancer Institute that covers approximately 30% of the US population and aims to provide a platform for conducting comprehensive clinical trials at the national level.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the site of the lesion is the colon and rectum (site record, International Classification of Diseases in Oncology (ICD-O-3)/ WHO 2009); (2) histology or pathology of the lesion is confirmed as carcinoma (ICD-O-3 Hist/obstructive, malignant); (3) TNM stage information is complete; (4) primary tumor lesions are at more than one site; (5) patients have undergone curative surgery.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1): primary tumor lesion is single;(2): information on age, sex, marriage status, ethnicity, TNM stage, tumor features, treatment regimes and survival is unknown or incomplete; (3): missing detail information for transforming to align with 8th AJCC staging.

The use of data from the SEER database was approved.

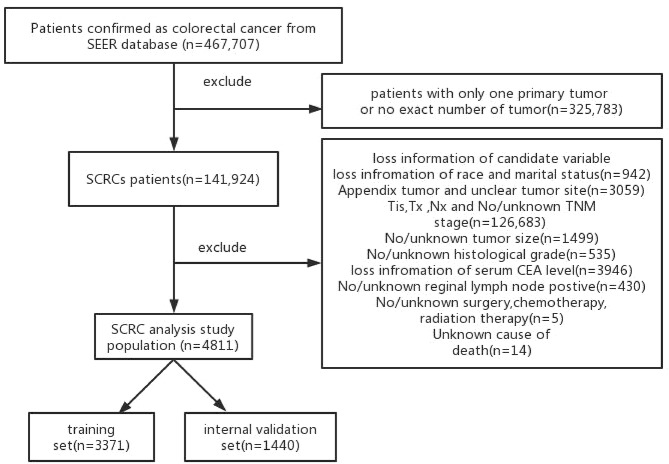

Finally, a total of 4811 patients were enrolled in this retrospective study (Fig. 1). Furthermore, in case of model overfitting and in order to ensure the accuracy of the model, these patients were randomly divided into training set (n = 3371) and internal validation set(n = 1440) in a 7:3 ratio.

Fig. 1.

The selection flow diagram of patients in the SEER database

To further validate the proposed Nomogram, a total of 100 patients diagnosed with SCRCs in the Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital (NJPH) from March 2013 to October 2022 were enrolled in the external validation set. Patients in this validation set were recruited according to the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as the training cohort. The time of last follow-up was November 2022. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians. Besides, all procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines.

Clinical variables extracted for analysis

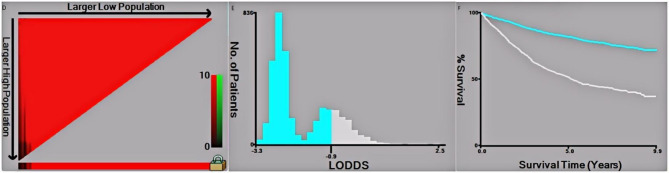

Data analysis was performed using R software(4.2.1ver, http://www.rproject.org/). We conducted a chi-square test for all included variables between the training and validation sets. Univariate Cox regression was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and continuous variables risk factors that were significant in the univariate analysis were identified as independent risk factors using multivariate analysis. As a result, several variables were included in the study: sex, age at diagnosis, marital status, race of demographics, histological type, tumor pathological grade, T stage, N stage, M stage, preoperative serum CEA level, number of tested and positive lymph nodes, LODDS of tumor features, radiotherapy, chemotherapy of treatment information, vital status, months of survival and cause of death of survival variables. Furthermore, We determined and visualized the optimal cutoff points of tumor size and LODDS variables in this study using x-tile software(Version 3.6.1, Copyright Yale University 2003),and the results are rounded to two decimal place (Fig. 2). The endpoints of this study were set as overall survival(OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Fig. 2.

The X-tile analysis of best-cutoff points of LODDS

Construction and validation of the Nomogram

A total of two Nomogram models of overall OS and CSS for SCRCs patients were constructed from these variables using the “RMS” package in R software (4.2.1ver). The newly established Nomograms were then evaluated through an internal validation cohort. To identify the discriminating superiority of the Nomograms, various methods were then performed. The predictive accuracy and discriminatory power of the Nomogram models were assessed using the C-index. The calibration curves and ROC curves were used for visualized comparison of the prediction predicted by the Nomogram and the actual OS and CSS performance. In addition, to verify the clinical net benefits for patients of those two Nomograms, the clinical practical performance of Nomograms was compared with TNM staging in decision curve analysis (DCA). P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of included cases

Followed by inclusion criteria, a total of 4811 cases were finally included in this study, 3371 of which were assigned to training set and 1440 to internal validation set in a 7:3 ratio. The details of demographics, clinical and therapy information of training cohort and internal validation cohort were shown in Table 1. A total of 100 SCRCs patients from our hospital were set as an external validation cohort (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics and treatment of patients with SCRCs

| Training cohort (N = 3371) |

Internal validation cohort (N = 1440) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| < 65 | 1007 (29.9%) | 436 (30.3%) | 0.805 |

| ≥ 65 | 2364 (70.1%) | 1004 (69.7%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1592 (47.2%) | 695 (48.3%) | 0.53 |

| Male | 1779 (52.8%) | 745 (51.7%) | |

| Race | |||

| Black | 221 (6.6%) | 107 (7.4%) | 0.508 |

| White | 2684 (79.6%) | 1130 (78.5%) | |

| Others | 466 (13.8%) | 203 (14.1%) | |

| Marital | |||

| Unmarried | 1393 (41.3%) | 632 (43.9%) | 0.105 |

| Married | 1978 (58.7%) | 808 (56.1%) | |

| Primary site | |||

| Right colon | 1005 (29.8%) | 443 (30.8%) | 0.824 |

| Transverse colon | 458 (13.6%) | 184 (12.8%) | |

| Left colon | 1055 (31.3%) | 455 (31.6%) | |

| Rectum | 853 (25.3%) | 358 (24.9%) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 3077 (91.2%) | 1312 (91.1%) | 0.794 |

| MCC/SRCC | 294 (8.7%) | 128 (8.9%) | |

| Tumor size | |||

| < 5 cm | 2106 (62.5%) | 918 (63.8%) | 0.42 |

| ≥ 5 cm | 1265 (37.5%) | 522 (36.3%) | |

| T stage | |||

| T1 | 359 (10.6%) | 163 (11.3%) | 0.917 |

| T2 | 555 (16.5%) | 237 (16.5%) | |

| T3 | 1965 (58.3%) | 829 (57.6%) | |

| T4 | 492 (14.6%) | 211 (14.7%) | |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 1983 (58.8%) | 856 (59.4%) | 0.874 |

| N1 | 947 (28.1%) | 394 (27.4%) | |

| N2 | 441 (13.1%) | 190 (13.2%) | |

| M stage | |||

| M0 | 3065 (90.9%) | 1312 (91.1%) | 0.878 |

| M1 | 306 (9.1%) | 128 (8.9%) | |

| Grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 197 (5.8%) | 92 (6.4%) | 0.631 |

| Moderately differentiated | 2496 (74.0%) | 1068 (74.2%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 545 (16.2%) | 217 (15.1%) | |

| Undifferentiated | 133 (3.9%) | 63 (4.4%) | |

| CEA | |||

| Normal | 2022 (60.0%) | 833 (57.8%) | 0.177 |

| Elevated | 1349 (40.0%) | 607 (42.2%) | |

| LODDS | |||

| < 0.35 | 2791 (82.8%) | 1197 (83.1%) | 0.813 |

| ≥ 0.35 | 580 (17.2%) | 243 (16.9%) | |

| Radiation | |||

| No/Unknown | 2927 (86.8%) | 1279 (88.8%) | 0.063 |

| Yes | 444 (13.2%) | 161 (11.2%) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| No | 2061 (61.1%) | 889 (61.7%) | 0.721 |

| Yes | 1310 (38.9%) | 551 (38.3%) |

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of external validation set. MCC: mucinous cell carcinoma; SRCC: signet ring cell carcinoma; LODDS: log odds of positive LNs

| External validation cohort | ||

|---|---|---|

| (N = 100) | % | |

| Age | ||

| < 65 | 31 | 31% |

| ≥ 65 | 69 | 69% |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 46 | 46% |

| Male | 54 | 54% |

| Marital | ||

| Unmarried | 41 | 41% |

| Married | 59 | 59% |

| Primary site | ||

| Right colon | 28 | 28% |

| Transverse colon | 11 | 11% |

| Left colon | 33 | 33% |

| Rectum | 28 | 28% |

| Pathology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 92 | 92% |

| MCC/SRCC | 8 | 8% |

| Tumor size | ||

| < 5 cm | 61 | 61% |

| ≥ 5 cm | 39 | 39% |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 15 | 15% |

| T2 | 15 | 15% |

| T3 | 55 | 55% |

| T4 | 15 | 15% |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 53 | 53% |

| N1 | 36 | 36% |

| N2 | 11 | 11% |

| M stage | ||

| M0 | 92 | 92% |

| M1 | 8 | 8% |

| Grade | ||

| Well differentiated | 6 | 6% |

| Moderately differentiated | 75 | 75% |

| Poorly differentiated | 14 | 14% |

| Undifferentiated | 5 | 5% |

| CEA | ||

| Normal | 63 | 63% |

| Elevated | 37 | 37% |

| LODDS | ||

| < 0.35 | 85 | 85% |

| ≥ 0.35 | 15 | 15% |

| Radiation | ||

| No/Unknown | 84 | 84% |

| Yes | 16 | 16% |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 55 | 55% |

| Yes | 45 | 45% |

MCC: mucinous cell carcinoma; SRCC: signet ring cell carcinoma; LODDS: log odds of positive LNs

In all enrolled patients, 47.53% of them were female and 52.47% were male; 57.91% were married and 42.09% were unmarried; 79.27% were Caucasian and 20.73% were other race; 74.83% were colon cancer and 25.17% were rectal cancer. We used x-tile software to calculate and determine the cutoff points of LODDS (Fig. 2). It was found No significant differences between the training and validation cohorts among any of the included variables.

Establishment of the Nomogram

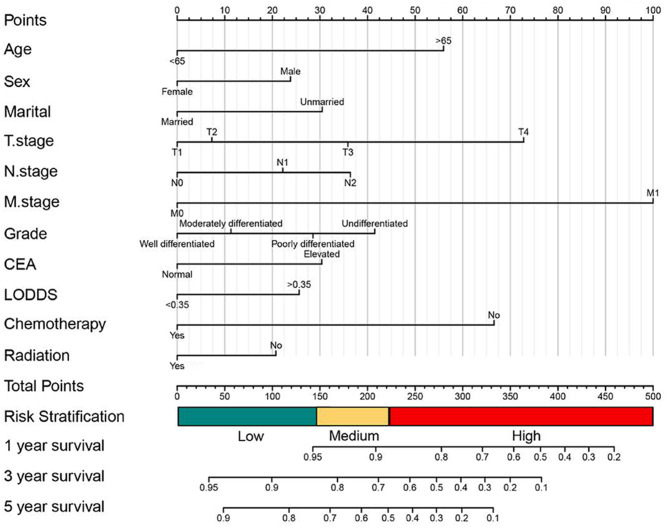

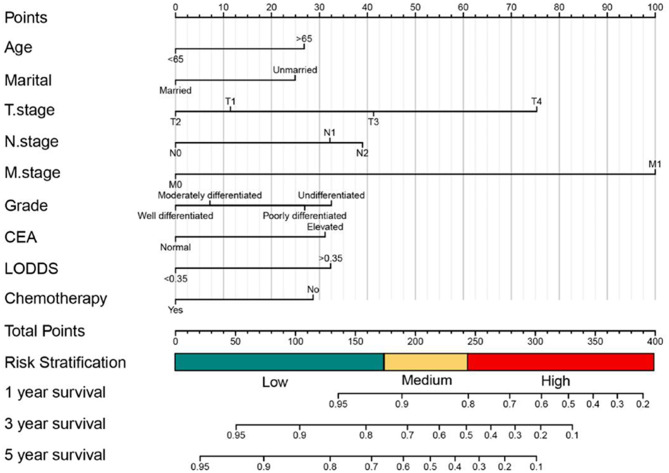

Eventually, the results showed that baseline demographics (sex, age, marital status), tumor features (tumor size, tumor pathological grade, preoperative serum CEA level, LODDS, AJCC TNM stage), treatment information(radiotherapy and chemotherapy) were all demonstrated high statistically discrepancy in univariate OS analysis. Meanwhile, baseline demographics (sex, age, marital status), tumor features (tumor pathological grade, LODDS, AJCC TNM stage, preoperative serum CEA level), treatment information (radiotherapy and chemotherapy) were all demonstrated high statistically discrepancy in OS multivariate analysis (Table 3). Meanwhile in CSS, the results showed that baseline demographics(age, marital status), tumor features(tumor size, tumor pathological grade, preoperative serum CEA level, AJCC TNM stage, LODDS), treatment information(chemotherapy) were all demonstrated high statistically discrepancy in univariate CSS analysis. Baseline demographics(age, marital status), tumor features(AJCC TNM stage, tumor pathological grade, preoperative serum CEA level, LODDS), and chemotherapy were significantly identified with CSS in multivariate analysis(Table 4). Therefore, we established OS and CSS Nomogram models with risk stratification scales of 1-, 3- and 5-year, respectively (Figs. 3 and 5). The model equations to survival probabilities were as follow:

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival in the training set. MCC: mucinous cell carcinoma; SRCC: signet ring cell carcinoma; LODDS: log odds of positive LNs

| Variables | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Sex | 0.0016 | ||

| Female | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.272(1.158–1.397) | < 0.001 | |

| Age | < 0.001 | ||

| <65 | Reference | ||

| ≥65 | 1.839(1.629–2.078) | < 0.001 | |

| Marital | < 0.001 | ||

| Married | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.394(1.264–1.538) | < 0.001 | |

| Race | 0.84 | ||

| White | —— | —— | |

| Black | —— | —— | |

| Others | —— | —— | |

| Tumor site | 0.02 | ||

| Left colon | —— | —— | |

| Transverse colon | —— | —— | |

| Right colon | —— | —— | |

| Rectum | —— | —— | |

| Pathology | 0.42 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | —— | —— | |

| MCC/SRCC | —— | —— | |

| Tumor size | < 0.001 | ||

| <5 cm | Reference | ||

| ≥5 cm | 1.039(0.937–1.151) | 0.464 | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | ||

| Well differentiated | Reference | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 1.126(0.906-1.400) | 0.285 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1.361(1.070–1.731) | 0.012 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1.573(1.164–2.126) | 0.003 | |

| CEA | < 0.001 | ||

| Normal | Reference | ||

| Up | 0.715(0.648–0.790) | < 0.001 | |

| T stage | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | Reference | ||

| T2 | 1.088(0.873–1.356) | 0.454 | |

| T3 | 1.501(1.233–1.829) | < 0.001 | |

| T4 | 2.257(1.799–2.832) | < 0.001 | |

| N stage | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | Reference | ||

| N1 | 1.272(1.115–1.452) | < 0.001 | |

| N2 | 1.491(1.153–1.928) | < 0.001 | |

| M stage | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | Reference | ||

| M1 | 2.973(2.556–3.458) | < 0.001 | |

| LODDS | 0.11 | ||

| < 0.35 | Reference | ||

| ≥ 0.35 | 1.315(1.06–1.632) | 0.0127 | |

| Chemotherapy | < 0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.485(0.424–0.554) | < 0.001 | |

| Radiation | 0.006 | ||

| No/Unknown | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.235(1.023–1.490) | 0.0284 | |

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of cancer specific survival in the training. MCC: mucinous cell carcinoma; SRCC: signet ring cell carcinoma; LODDS: log odds

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Sex | 0.54 | ||

| Female | —— | —— | |

| Male | —— | —— | |

| Age | < 0.001 | ||

| <65 | Reference | ||

| ≥65 | 1.440(1.235–1.679) | < 0.001 | |

| Marital | < 0.001 | ||

| Married | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.400(1.231-1.600) | < 0.001 | |

| Race | 0.64 | ||

| White | —— | —— | |

| Black | —— | —— | |

| Others | —— | —— | |

| Tumor site | 0.14 | ||

| Left colon | —— | ||

| ransverse colon | —— | —— | |

| Right colon | —— | —— | |

| Rectum | —— | —— | |

| Pathology | 0.76 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | —— | —— | |

| MCC/SRCC | —— | —— | |

| Tumor size | < 0.001 | ||

| ≥5 cm | Reference | ||

| <5 cm | 1.029(0.896–1.182) | 0.681 | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | ||

| Well differentiated | Reference | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 1.099(0.794–1.523) | 0.566 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1.440(1.017–2.039) | 0.039 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1.556(1.016–2.383) | 0.041 | |

| CEA | < 0.001 | ||

| Normal | Reference | ||

| Up | 0.653(0.570–0.749) | < 0.001 | |

| T stage | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | Reference | ||

| T2 | 0.858(0.600-1.228) | 0.403 | |

| T3 | 1.516(1.119–2.053) | 0.007 | |

| T4 | 2.412(1.732–3.358) | < 0.001 | |

| N stage | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | Reference | ||

| N1 | 1.547(1.288–1.858) | < 0.001 | |

| N2 | 1.699(1.240–2.328) | < 0.001 | |

| M stage | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | Reference | ||

| M1 | 3.881(3.268–4.607) | < 0.001 | |

| LODDS | 0.063 | ||

| < 0.35 | Reference | ||

| ≥ 0.35 | 1.546(1.196–1.996) | 0.681 | |

| Chemotherapy | < 0.001 | ||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.677(0.57–0.749) | < 0.001 | |

| Radiation | 0.5 | ||

| No/Unknown | —— | —— | |

| Yes | —— | —— | |

Fig. 3.

Establishment of 1,3 and 5 year overall survival(OS) prediction in SCRCs patients with a risk classification system

Fig. 5.

Establishment of 1,3 and 5 year cancer specific survival(CSS) prediction in SCRCs patients with a risk classification system

OS:S(t|X) = e− t*H(t|X) = e− t*ho(t)exp(0.60958*Age>65

+0.26002*SexMale+0.33249*MaritalUnmarried+0.40654

*T.stageT3+0.81420*T.stageT4+0.24087*N.stageN1+0.39958

*N.stageN2+1.08966*M.stageM1+0.30797*GradePoorlydifferentiated

+0.45307*GradeUndiffe−rentiated−0.33498*CEANormal

+0.27396*LODDS>0.35–0.72385*ChemotherapyYes−0.21064*RadiationYes)

CSS:S(t|X) = e − t*H(t|X)=e− t*ho(t)exp(0.36473*Age>65

+0.33898*MaritalUnmarried+0.41643*T.stageT3+0.88055

*T.stageT4+0.43647*N.stageN1+0.53036*N.stageN2

+1.35606*M.stageM1+0.36501*GradePoorlydifferentiated

+0.44234*GradeUndiffe−rentiated−0.42539*CEANormal

+0.43555*LODDS>0.35–0.38873*ChemotherapyYes)

Nomogram validation

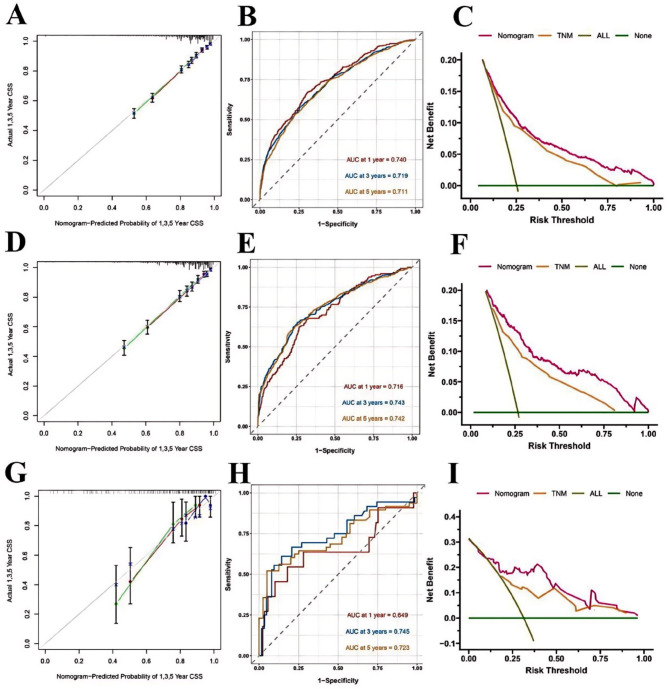

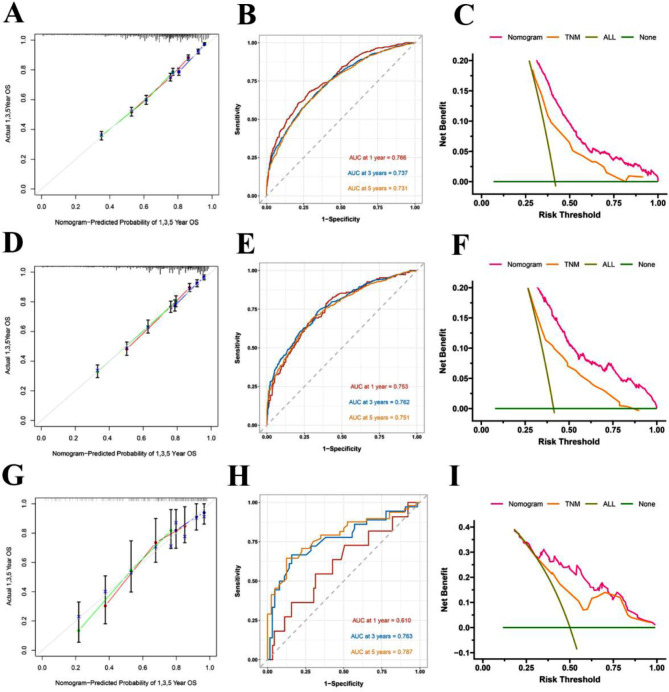

To validate the performance of the Nomogram, training set, internal and external validation were assessed by C-index, calibration curves, DCA and ROC curves. The C-index of OS Nomogram was 0.679 (95%CI: 0.675–0.703) in training cohort, 0.709 (95%CI: 0.689–0.729) in internal validation cohort and 0.718(95%CI: 0.644–0.792)in the external validation cohort. C-index of CSS was 0.741 (95%CI: 0.723–0.759) in training cohort, 0.763 (95%CI: 0.739–0.787) in internal validation cohort and 0.762(95%CI: 0.662–0.862) in the external validation cohort (Table 5). In predicting outcome in 1-,3- and 5- year, According to the calibration curves (Figs. 5A, D and G and 6A, D and G)they indicated consistent high quality of both OS and CSS Nomogram models (Figs. 3 and 5). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year AUC values of the nomogram for OS were 76.6%, 73.7%, 73.1% in the training cohort (Fig. 4B); 75.3%, 76.2%, 75.1% in the internal validation cohort (Fig. 4E); and 61.0%, 76.3%, 78.7% in the external validation cohort (Fig. 4H); Meanwhile, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year AUC values of the nomogram for CSS were 74%, 71.9%, 71.1% in the training cohort (Fig. 6B); 71.6%, 74.3%, 74.2% in the internal validation cohort (Fig. 6E); and 64.9%, 74.5%, 72.3% in the external validation cohort (Fig. 6H), which revealed an excellent sensitivity and specificity for the predictive model. In DCA, both OS and CSS Nomograms showed a superior clinical net benefit to AJCC TNM stage (Figs. 4C, F and I and 6C, F and I).

Table 5.

C-indexes for Nomograms and TNM stage system in patient with SCRCs

| Survival | Training set | Internal validation set | External validation set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| OS | Nomogram | 0.679 | 0.675–0.703 | 0.709 | 0.689–0.729 | 0.718 | 0.644–0.792 |

| 8th edition TNM stage | 0.623 | 0.609–0.637 | 0.630 | 0.608–0.652 | 0.660 | 0.589–0.731 | |

| CSS | Nomogram | 0.741 | 0.723–0.759 | 0.763 | 0.739–0.787 | 0.762 | 0.662–0.862 |

| 8th edition TNM stage | 0.715 | 0.697–0.732 | 0.711 | 0.686–0.736 | 0.699 | 0.607–0.791 | |

Fig. 6.

Calibration curve for the predicted CSS in the training group 1,3,5 years (A); ROC curves for the nomogram predicting CSS in the training group (B); Decision curve analysis of Nomogram of the CSS in the training set、AJCC 8th TNM and all prognostic factors (C); Calibration curve for the predicted CSS in the internal validation group 1,3,5 years (D); ROC curves for the nomogram predicting CSS in the internal validation group (E); Decision curve analysis of Nomogram of the CSS in the internal validation group、AJCC 8th TNM and all prognostic factors (F); Calibration curve for the predicted CSS in the external validation group 1,3,5 years (G); ROC curves for the nomogram predicting CSS in the external validation group (H); Decision curve analysis of Nomogram of the CSS in the external validation group、AJCC 8th TNM and all prognostic factors (I)

Fig. 4.

Calibration curve for the predicted OS in the training group 1,3,5 years (A); ROC curves for the nomogram predicting OS in the training group (B); Decision curve analysis of Nomogram of the OS in the training set、AJCC 8th TNM and all prognostic factors (C); Calibration curve for the predicted OS in the internal validation group 1,3,5 years (D); ROC curves for the nomogram predicting OS in the internal validation group (E); Decision curve analysis of Nomogram of the OS in the internal validation group、AJCC 8th TNM and all prognostic factors (F); Calibration curve for the predicted OS in the external validation group 1,3,5 years (G); ROC curves for the nomogram predicting OS in the external validation group (H); Decision curve analysis of Nomogram of the OS in the external validation group、AJCC 8th TNM and all prognostic factors (I)

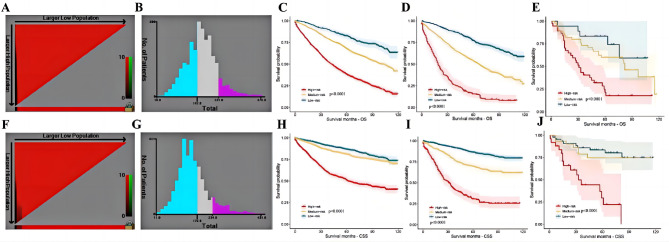

Nomograms integrating with risk stratification scales

In accordance to the risk scores of the Nomograms, we utilized X-tile software to classify patients into high risk, intermediate-risk, and low-risk levels in terms of OS and CSS (Fig. 7A, B, F and G; Tables 6 and 7). Meanwhile, we integrate the Nomograms with the risk scores to visualize the risk stratification (Figs. 3 and 5). The cut-off values were 147 and 221 for OS (Fig. 7B), 172 and 234 for CSS (Fig. 7G). The Kaplan-Meier curve showed that this risk stratification scales had good stratification and discrimination of OS and CSS in the training, internal validation and external validation cohorts (Fig. 7C, D, E, H, I and J).

Fig. 7.

The optimal cut-off value and establishing a risk classification system by the X-tile software. The best cutoff value for the predicted overall survival total score of low-risk group (score: 0-147), intermediate-risk group (score: 147–221), and high-risk group (score: 221–370) (A-B); Draw Kaplan-Meier curves for different risk levels from the OS of the training cohort (C) the internal validation cohort (D)and and the external validation cohort (E).The best cutoff value for the predicted cancer specific survival total score of low-risk group (score: 0-172), intermediate-risk group (score: 172–234), and high-risk group (score: 234–431)(F-G); Draw Kaplan-Meier curves for different risk levels from the CSS of the training cohort (H) the internal validation cohort (I)and and the external validation cohort (J)

Table 6.

The regression coefficient and the estimated score of the overall survival Nomogram prediction model based on the training cohort. LODDS: log odds of positive LNs

| Variables | Nomogram | |

|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | Estimated Score | |

| Age | ||

| <65 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥65 | 44.7306 | 45 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 0 | 0 |

| Male | 19.1274 | 19 |

| Marital | ||

| Unmarried | 25.43469 | 25 |

| Married | 0 | 0 |

| Grade | ||

| Well differentiated | 0 | 0 |

| Moderately differentiated | 10.21665 | 10 |

| Poorly differentiated | 24.30120 | 24 |

| Undifferentiated | 34.71363 | 35 |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 0 | 0 |

| T2 | 6.187249 | 6 |

| T3 | 29.505174 | 30 |

| T4 | 59.385147 | 59 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 0 | 0 |

| N1 | 12.21042 | 12 |

| N2 | 14.58433 | 15 |

| M stage | ||

| M0 | 0 | 0 |

| M1 | 79.86762 | 80 |

| CEA | ||

| Normal | 0 | 0 |

| Elevated | 25.21053 | 25 |

| LODDS | ||

| <0.35 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥0.35 | 25.61105 | 25 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 66.78187 | 67 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| Radiation | ||

| No/Unknown | 0 | 0 |

| Yes | 20.72507 | 21 |

Table 7.

The regression coefficient and the estimated score of the cancer specific survival Nomogram prediction model based on the training cohort. LODDS: log odds of positive LNs

| Variables | Nomogram | |

|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | Estimated Score | |

| Age | ||

| <65 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥65 | 55.19965 | 55 |

| Marital | ||

| Unmarried | 31.08904 | 31 |

| Married | 0 | 0 |

| Grade | ||

| Well differentiated | 0 | 0 |

| Moderately differentiated | 10.99688 | 11 |

| Poorly differentiated | 28.27369 | 28 |

| Undifferentiated | 41.18176 | 41 |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 0 | 0 |

| T2 | 7.650645 | 8 |

| T3 | 36.292879 | 36 |

| T4 | 73.275432 | 73 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 0 | 0 |

| N1 | 19.63677 | 20 |

| N2 | 31.65511 | 32 |

| M stage | ||

| M0 | 0 | 0 |

| M1 | 100 | 100 |

| CEA | ||

| Normal | 0 | 0 |

| Elevated | 30.03972 | 30 |

| LODDS | ||

| <0.35 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥0.35 | 25.61105 | 26 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 66.78187 | 67 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

Synchronous colorectal cancers are a special and rare type of colorectal malignancy compared to solitary tumors [3, 4]. Based on previous studies, SCRCs was prone to develop a poor prognosis, even though the pathological stages of tumors were identical and the curative resections and comminated chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy were performed [12–16, 28, 29]. To the best of our knowledge, SCRCs have been a challenging malignancy with unique characteristics that have often been overlooked by previous research. Limited previous studies have attempted to stratify the risk of death and progression in patients with SCRCs, and even fewer have specifically focused on the Nomogram implementation. The Nomogram, a graphic representation of risk factors and their corresponding weights, has been underutilized in the field of SCRCs, with only a few studies exploring its potential application. Previous efforts to stratify risk in SCRCs have been primarily limited to traditional staging systems that often fail to consider the complex interplay of multiple risk factors. However, the Nomogram, as a more comprehensive risk assessment tool, has the potential to address this limitation by accounting for a broader range of factors including demographic, clinical, histopathological, and molecular variables. The Nomogram can provide a more accurate and individualized risk assessment of patient outcomes in SCRCs compared to traditional staging systems. It can also facilitate the identification of high-risk patients who may benefit from more aggressive treatment strategies and earlier intervention. Additionally, the Nomogram can provide a useful tool for stratifying risk in clinical trials and evaluating treatment response and disease prognosis. Despite the limited research on the Nomogram application in SCRCs, preliminary studies have shown promise in improving risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

We established and validated a novel Nomogram for SCRCs post-operation prediction. Besides, we incorporated LODDS into the Nomogram as independent risk factors to make up the deficiency of efficacy of pN stage when the number of retrieved lymph node was inadequate.

In OS Nomogram, there were in total of 11 variables, including baseline demographics(sex, age, marital status), tumor features(tumor pathological grade, AJCC TNM stage, preoperative serum CEA level, LODDS), treatment information (radiotherapy and chemotherapy), were determined for the Nomogram construction. In CSS, there were in total of 10 variables, including demographics(age and marital status), tumor features(AJCC TNM stage, tumor pathological grade, preoperative serum CEA level, LODDS), treatment information(radiotherapy and chemotherapy), were determined for the construction of Nomogram. Therefore, it was of great possibility that the prognosis of SCRCs could be compromised by more indicators than general single colorectal cancer cases. In our study, younger age, married marital status, male was identified as a protective factor in OS Nomogram, radiotherapy and chemotherapy were identified as protective factors in both OS and CSS Nomograms. Consistent to previous studies, advanced pT stage, pN stage, pM stage, worse differentiated pathological grade and elevated preoperative serum CEA were risk indicators in both OS and CSS Nomograms.

Moreover, it was the first time that two types of lymph node based variables(pN stage, LODDS) had been incorporated for Nomogram of SCRCs. Regional lymph node metastases are considered a key factor in assessing the prognosis of overall CRC patients [28–31]. However, the actual number of retrieved LNs during surgery is often compromised by multiple factors. LNR is regarded as a novel prognostic factor for various cancers. It is characterised by a combination of TLNs and PLNs, so to overcome the limitation posed by inadequate retrieved TLNs [25, 26, 32, 33]. It has been indicated that the LNR has a superior prognostic capability than the absolute number of PLNs in a recent study by Klos et al. [32]. However, the LNR also has shortcomings. First, it cannot be applied for AJCC N0 patients [34]. Second, when negative LNs were omitted, only few positive LNs were retrieved during the operation .Under this circumstance, PLNN is equal to ELNN (LNR = 1), such that patients are classified as higher LNR stage even with few positive LNs, as confirmed by many studies [35, 36].

Consequently, the LODDS is developed to make up those shortcomings. LODDS is defined as the log of the ratio between the number of positive lymph nodes (PLNs) and the number of negative lymph nodes (NLNs), which means that LODDS can be used to make up the shortcomings of LNR, it may fulfill the prognostic accuracy of lymph nodes related indicators, and further could be used as a superior prognostic factor compared to LNR and pN stage [21, 22, 24, 37]. However, the prognostic significance of the LODDS stage in patients with SCRCs and its staging accuracy have not been testified yet. It is in accordance with our study that pN stage and LODDS are regarded as the predictors in both OS and CSS Nomogram, but LNR is identified as the predictor only in CSS Nomogram.

Nevertheless, it cannot be ignored that our study has several limitations. First, this study was designed and implemented retrospectively, and the number limited patients enrolled in as the external validation set were extracted from merely one hospital, although we performed the internal validation ahead using patients from the SEER database. Hereby, future multicenter studies with large sample sizes are needed to validate our findings and apply those two Nomogram to clinical practice. Second, the surgical and medication regimens administered to the patients were heterogeneous and hard to coordinate, as the specific therapeutic methods cannot well coordinated among all patients. In addition, the different surgical procedures and chemotherapeutic as well as radiotherapy regimens could compromise the prognosis of patients with different diseases and conditions, making it difficult to compare the treatment results of different treatment methods. Furthermore, compared with the solitary colorectal tumor, MSI phenotype is reported to be more common in SCRCs lesions by Nosho et al [38]. Nosho et al. [38] also showed that SCRCs more frequently contained mutations in the cell cycle signaling gene BRAF (p = 0.0041). The genetic mutations related variables have not been collected in the SEER yet, so this study failed to include MSI phenotype, KRAS and BRAF mutation status. Hence, concerning other important factors that may affect prognosis, including adjuvant treatments, microsatellite instability, KRAS and BRAF mutation status [39–41]. It is needed that we should integrate these factors in future study.

In our study, those two Nomograms demonstrated comparatively high C-index and credible calibration curves for predicting OS and CSS of SCRCs patients using internal and external validation sets. Furthermore, compared to AJCC TNM standard, those two Nomograms achieved higher values in DCA assessment.

Conclusion

In summary, the novel Nomograms developed in this study can visualize the risk indicators of SCRCs and effectively predict the OS and CSS for SCRCs patients, contributing to identify high risk patients who require more aggressive therapeutic intervention and longer and more frequent follow-up scheme. The clinicians could make a precious and individualized therapeutic regimen, minimize the interval time between the diagnosis and initial of therapy, take a efficient coordination among oncology departments, ultimately improve clinical outcomes of SCRCs patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with language assistance from Yue Ma, writing assistance from Daorong Wang and Jun Ren, and proofreading of the article by Jun Ren.

Abbreviations

- SCRCs

Synchronous colorectal cancers

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

- CSS

Cancer-specific survival

- OS

Overall survival

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- LODDS

Log odds of positive lymph nodes

- ELNN

Examined lymph node number

- PLNN

Positive lymph node number

- LN

Lymph node

Author contributions

The paper was written by Yue Ma. Data analysis was done by Bangquan Chen. Study search and screening were done by Yayan Fu. Article reviewed was done by Jun Ren. The whole process was instructed by Daorong Wang. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was sponsored by Key Laboratory of Basic and Clinical Transformation of Digestive /Metabolic Diseases of Yangzhou City(No.YZ2020159).

Data availability

The data sets used during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

Yue Ma, Bangquan Chen, Yayan Fu, Jun Ren and Daorong Wang declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66(4):683–91. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2022. CA: Cancer J Clin 72(1):7–33. 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.van Leersum NJ, Aalbers AG, Snijders HS, Henneman D, Wouters MW, Tollenaar RA, et al. Synchronous colorectal carcinoma: a risk factor in colorectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(4):460–6. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam AK, Carmichael R, Gertraud Buettner P, Gopalan V, Ho YH, Siu S. Clinicopathological significance of synchronous carcinoma in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2011;202(1):39–44. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.05.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren S, Gates O. Carcinoma of ceruminous gland. Am J Pathol. 1941;17(6):821–8263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evers BM, Mullins RJ, Matthews TH, Broghamer WL, Polk HC Jr. Multiple adenocarcinomas of the colon and rectum. An analysis of incidences and current trends. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31(7):518–22. 10.1007/BF02553724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di J, Yang H, Jiang B, Wang Z, Ji J, Su X. Whole exome sequencing reveals intertumor heterogeneity and distinct genetic origins of sporadic synchronous colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(5):927–39. 10.1002/ijc.31140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung YS, Park JH, Park CH. Serrated polyps and the risk of Metachronous Colorectal Advanced Neoplasia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):31–e431. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalo V, Lozano JJ, Muñoz J, Balaguer F, Pellisé M, de Rodríguez, et al. Aberrant gene promoter methylation associated with sporadic multiple colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8777. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008777. Published 2010 Jan 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen HS, Sheen-Chen SM. Synchronous and early metachronous colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis of prognosis and current trends. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(8):1093–9. 10.1007/BF02236556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oya M, Takahashi S, Okuyama T, Yamaguchi M, Ueda Y. Synchronous colorectal carcinoma: clinico-pathological features and prognosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33(1):38–43. 10.1093/jjco/hyg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadopoulos V, Michalopoulos A, Basdanis G, Papapolychroniadis K, Paramythiotis D, Fotiadis P, et al. Synchronous and metachronous colorectal carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8(Suppl 1):s97–100. 10.1007/s10151-004-0124-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passman MA, Pommier RF, Vetto JT. Synchronous colon primaries have the same prognosis as solitary colon cancers. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(3):329–34. 10.1007/BF02049477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adloff M, Arnaud JP, Bergamaschi R, Schloegel M. Synchronous carcinoma of the colon and rectum: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Am J Surg. 1989;157(3):299–302. 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latournerie M, Jooste V, Cottet V, Lepage C, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology and prognosis of synchronous colorectal cancers. Br J Surg. 2008;95(12):1528–33. 10.1002/bjs.6382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikoloudis N, Saliangas K, Economou A, Andreadis E, Siminou S, Manna I, et al. Synchronous colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8(Suppl 1):s177–9. 10.1007/s10151-004-0149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang HZ, Huang XF, Wang Y, Ji JF, Gu J. Clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of multiple primary colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(14):2136–9. 10.3748/wjg.v10.i14.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Copeland EM, Jones RS, Miller LD. Multiple colon neoplasms. Prognostic and therapeutic implications. Arch Surg. 1969;98(2):141–3. 10.1001/archsurg.1969.01340080033004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volk N, Lacy B. Anatomy and physiology of the small bowel. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2017;27(1):1–13. 10.1016/j.giec.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Z, Xu Y, Li de M, Wang ZN, Zhu GL, Huang BJ, et al. Log odds of positive lymph nodes: a novel prognostic indicator superior to the number-based and the ratio-based N category for gastric cancer patients with R0 resection. Cancer. 2010;116(11):2571–80. 10.1002/cncr.24989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang B, Ni M, Chen C, Cai G, Cai S. LODDS is superior to lymph node ratio for the prognosis of node-positive rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative radiotherapy. Tumori. 2017;103(1):87–92. 10.5301/tj.5000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scarinci A, Di Cesare T, Cavaniglia D, Neri T, Colletti M, Cosenza G, et al. The impact of log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) in colon and rectal cancer patient stratification: a single-center analysis of 323 patients. Updates Surg. 2018;70(1):23–31. 10.1007/s13304-018-0519-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Appleby DH, Zhang X, Gan L, Wang JJ, Wan F. Comparison of three lymph node staging schemes for predicting outcome in patients with gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(4):505–14. 10.1002/bjs.9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramacciato G, Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Pinna AD, Ravaioli M, Jovine E, et al. Prognostic role of nodal ratio, LODDS, pN in patients with pancreatic cancer with venous involvement. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):109. 10.1186/s12893-017-0311-1. Published 2017 Nov 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Y, Li G, Zheng D, Jia M, Dai W, Sun Y, et al. The prognostic value of lymph node ratio and log odds of positive lymph nodes in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(3):702–e7091. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang CH, Li YY, Zhang QW, Biondi A, Fico V, Persiani R, et al. The prognostic impact of the metastatic lymph nodes ratio in Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:628. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00628. Published 2018 Dec 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang W, Shen Z, Shi Y, Zou S, Fu N, Jiang Y, et al. Accuracy of nodal positivity in inadequate lymphadenectomy in Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a Population Study using the US SEER database. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1386. 10.3389/fonc.2019.01386. Published 2019 Dec 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enciu O, Calu V, Angelescu M, Nădrăgea MA, Miron A. Emergency surgery and oncologic resection for complicated Colon cancer: what can we expect? A medium volume experience in Romania. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2019;114(2):200–6. 10.21614/chirurgia.114.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinto E, Hida JI, Kobayashi H, Hashiguchi Y, Hase K, Ueno H, et al. Prominent information of jN3 positive in Stage III Colorectal Cancer removed by D3 dissection: retrospective analysis of 6866 patients from a multi-institutional database in Japan. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(4):447–53. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Azad N, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, et al. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(10):1139–67. 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain MA, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, et al. Colon cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(3):329–59. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0012. Published 2021 Mar 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klos CL, Bordeianou LG, Sylla P, Chang Y, Berger DL. The prognostic value of lymph node ratio after neoadjuvant chemoradiation and rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(2):171–5. 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fd677d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park IJ, Yu CS, Lim SB, Yoon YS, Kim CW, Kim TW, et al. Ratio of metastatic lymph nodes is more important for rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(11):3274–81. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.La Torre M, Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Cavallini M, Aurello P, Cosenza G, et al. Prognostic assessment of different lymph node staging methods for pancreatic cancer with R0 resection: pN staging, lymph node ratio, log odds of positive lymph nodes. Pancreatology. 2014;14(4):289–94. 10.1016/j.pan.2014.05.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sierzega M, Nowak K, Kulig J, Matyja A, Nowak W, Popiela T. Lymph node involvement in ampullary cancer: the importance of the number, ratio, and location of metastatic nodes. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(1):19–24. 10.1002/jso.21283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JH, Lee KG, Ha TK, Jun YJ, Paik SS, Park HK, et al. Pattern analysis of lymph node metastasis and the prognostic importance of number of metastatic nodes in ampullary adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2011;77(3):322–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Hassett JM, Dayton MT, Kulaylat MN. The prognostic superiority of log odds of positive lymph nodes in stage III colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(10):1790–6. 10.1007/s11605-008-0651-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nosho K, Kure S, Irahara N, Shima K, Baba Y, Spiegelman D, et al. A prospective cohort study shows unique epigenetic, genetic, and prognostic features of synchronous colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1609–e20203. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C, Mei Z, Pei J, Abe M, Zeng X, Huang Q et al. A Modified Tumor-Node-Metastasis Classification for Primary Operable Colorectal Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;5(1):pkaa093. Published 2020 Oct 16. 10.1093/jncics/pkaa093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Imamura Y, Lochhead P, Yamauchi M, Kuchiba A, Qian ZR, Liao X, et al. Analyses of clinicopathological, molecular, and prognostic associations of KRAS codon 61 and codon 146 mutations in colorectal cancer: cohort study and literature review. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:135. 10.1186/1476-4598-13-135. Published 2014 May 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kosumi K, Hamada T, Zhang S, Liu L, da Silva A, Koh H, et al. Prognostic association of PTGS2 (COX-2) over-expression according to BRAF mutation status in colorectal cancer: results from two prospective cohorts and CALGB 89803 (Alliance) trial. Eur J Cancer. 2019;111:82–93. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.