Abstract

Background

Gene therapy holds great potential for treating various acquired and inherited pulmonary diseases. Adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors have been thought to be primary candidates for gene delivery in patients with pulmonary diseases. However, the tropism of AAVs in the lungs remains largely unknown.

Results

Here, we investigate the tropism of twenty serotypes of AAVs by examining AAV-packed vector expression of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) in mice. AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV-PHP.B, and AAV-PHP.S exhibit high transduction rates in the airway epithelium. AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, and AAV6.2 highly infect club cells. AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, and AAV-PHP.B efficiently infect ciliated cells. AAV8 and AAVrh10 can infect a few alveolar type I cells. AAV1, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV9, and AAVie can infect alveolar type II cells. AAV1, AAV5, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, and AAV-PHP.S can infect a few endothelial cells. However, none of these AAVs can efficiently infect neuroendocrine or smooth muscle cells.

Conclusions

Our findings provide comprehensive information about the tropism of AAVs in pulmonary epithelium in mice, which might be helpful in developing efficient AAV-mediated gene therapy strategies for pulmonary disease treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12985-024-02575-9.

Keywords: Adeno-associated virus, Tropism, Club cells, Ciliated cells, Alveolar epithelial cells

Introduction

Gene therapy holds promise for treating a range of inherited pulmonary diseases, including cystic fibrosis, α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and surfactant protein deficiencies [1]. Viral vectors have been used for gene delivery in preclinical studies and clinical treatment [2]. Among these vectors, adeno-associated virus (AAV)-packed vectors have developed into important tools for gene therapy study of respiratory diseases, which can effectively target the airway epithelium in vivo [3]. AAV, a single-stranded DNA virus with an average diameter of 20–25 nm, belongs to the member of the Dependoparvovirus genus of the Parvoviridae family. AAV has been found in a wide range of vertebrate species, including human and non-human primates [4, 5]. AAVs have great potential to be ideal gene delivery vectors because of their multiple advantages, such as non-pathogenicity, low immunogenicity, long-term transgene expression, no reported clinical adverse events, high stability, and wide range of infectable cell types, which make them widely used in basic research and preclinical translational studies [6].

AAV vectors are promising candidates for gene therapy for several pulmonary diseases, including cystic fibrosis (CF), asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary hypertension, and COVID-19 [7–10]. AAV vectors have been developed to enhance their packaging capacity and transduction. The packaging capacity of AAV vectors can be improved by creating a parvovirus chimera. Recent studies have demonstrated that chimeric AAV vectors such as rAAV2/HBoV1 show improved transduction efficacy in primary human airway epithelium and ferret lungs [11, 12]. Another study reports that six rAAV vectors (rAAV2 Y252F, rAAV2 Y272F, scrAAV2 WT, scrAAV8 Y773F, scrAAV9 WT, scrAAV9 Y446F) exhibit more efficient transduction than their counterparts in cystic fibrosis patient bronchial epithelial cells by overcoming the limitations of intracellular trafficking and second-strand DNA synthesis [13]. Comparative studies show that AAV5 and AAV6 exhibit much higher transduction rates than AAV2 in the airway epithelium [14, 15].

Although the transduction of several AAV serotypes in animals or cultured cells has been investigated [11, 16–19], which specific cell type(s) of AAVs can infect in detail remains largely unknown in the lungs. Here, we investigated the tropism of twenty commercial AAV serotypes, including AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAV-ie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, and AAV-PHP.S in the lungs in mice by analyzing their eGFP expression. We found that AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV9, AAV-PHP.B, and AAV-PHP.S had higher transduction efficiency than others in the lungs. AAV8, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAV-ie and AAV-PHP.eB had lower infection efficiency, whereas AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, MyoAAV 4A and AAV-7m8 showed fewer or no transduction. Our results provide for the first time comprehensive information on the tropism of AAVs in the mouse lungs.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 J mice were used in the experiments. All mouse husbandry was performed under standard conditions in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Guangzhou Medical University. All breeding colonies were maintained under cycles of 12 h light and 12 h dark. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with ethical guidelines and approved protocols.

Adeno-associated virus injection

AAVs serotypes (PackGene Biotech) used in this study were as follows: AAV1-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV2-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, MyoAAV 2A-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV2-retro-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV3b-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV4-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, MyoAAV 4A-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV5-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV6-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV6.2-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV7m8-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV8-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV9-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAVrh10-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV-DJ-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV-DJ/8-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV-ie-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV-PHP.B-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, AAV-PHP.eB-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA, and AAV-PHP.S-CAG-Dio-eGFP-WPRE-pA. For each mouse, 40 μL of AAV-containing solution (10 [13] GC/mL) was injected into the lungs through the trachea. Three mice were used for each AAV injection. The lungs were dissected for analysis after 10 days of AAV injection.

Immunostaining of cryosections

The lungs were harvested from C57BL/6 J mice injected with AAV-eGFP, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, 30,525–89-4) overnight at 4 °C, incubated in 10% sucrose and then in 30% sucrose at 4 °C until the tissue sinks to the bottom of the container, embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek, 25,608–930), and sectioned at the thickness of 8 μm using CM1860 cryostat (Leica Biosciences). Immunostaining was performed as described in our previous studies [20]. Briefly, sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4 °C, followed by incubation in permeabilization solution (0.3% Triton X-100/PBS) for 15 min at RT, incubated in blocking solution (5% FBS/PBS/3% BSA) for 1 h at RT, incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, washed three times in 5% FBS/PBS/0.5% Triton X-100/3% BSA for 10 min each at RT, incubated in secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT, washed three times in 5% FBS/PBS/ 0.5% Triton X-100/3% BSA for 10 min each at RT, incubated in DAPI solution for counterstain for 5 min at RT and then mounted for imaging using the laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM880, Zeiss).

Quantification

For each sample, 6 random fields were selected for cell counting of DAPI+ total cells, eGFP+ cells, secretoglobin family 1A member 1 (SCGB1A1) positive club cells, regulatory factor X3 (RXF3) positive or acetylated-α-tubulin positive ciliated cells, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) positive neuroendocrine cells, homeodomain-only protein homeobox (HOPX) positive alveolar type I cells, surfactant protein C (SFTPC) positive alveolar type II cells, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) positive smooth muscle cells and ETS-related gene (ERG) positive endothelial cells. Quantification of cell numbers was performed using ImageJ (Version 1.8.0.172).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-SCGB1A1 (1:400, abcam, ab40873); rabbit anti- RFX3 (1:500, Sigma, HPA035689); rabbit anti-CGRP (1:2000, ThermoFisher, PA5-114,929); rabbit anti-HOPX (1:1000, ThermoFisher, PA5-90,538); rabbit anti-SFTPC (1:2000, ThermoFisher, PA5-71,680); mouse anti-α-SMA-Cy3 (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich, C6198); rabbit anti-ERG (1:1000, abcam, ab92513); mouse anti-acetyl-α tubulin (1:2000, Sigma, MABT868); chicken anti-GFP (1:2000, abcam, ab13970); Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 568 (1:2000, A-11011); Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 568 (1:2000, A-11004) and Goat anti-Chicken IgY (H + L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 488 (1:2000, A-11039).

Results

AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV9, AAV-PHP.B and AAV-PHP.S exhibit high transduction efficiency in the lungs of mice

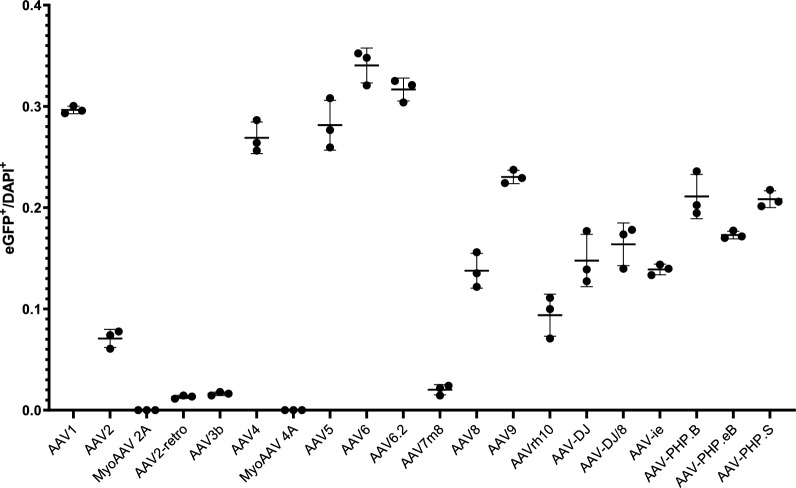

We investigated the infection efficiency and tropism of twenty commercial serotypes of AAV1 (Figs. 1 and 2), AAV2 (Figs. 1 and 3), MyoAAV 2A (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1), AAV2-retro (Supplementary Fig. 2), AAV3b (Fig. 4), AAV4 (Supplementary Fig. 3), MyoAAV 4A (Supplementary Fig. 4), AAV5 (Supplementary Fig. 5), AAV6 (Fig. 5), AAV6.2 (Supplementary Fig. 6), AAV7m8 (Supplementary Fig. 7), AAV8 (Fig. 6), AAV9 (Fig. 7), AAVrh10 (Supplementary Fig. 8), AAV-DJ (Supplementary Fig. 9), AAV-DJ/8 (Supplementary Fig. 10), AAV-ie (Supplementary Fig. 11), AAV-PHP.B (Supplementary Fig. 12), AAV-PHP.eB (Supplementary Fig. 13) and AAV-PHP.S (Supplementary Fig. 14). AAVs were delivered into the mouse lungs by intratracheal instillation. Immunofluorescence staining was performed to examine eGFP expression after a 10-day infection. We found that AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV9, AAV-PHP.B and AAV-PHP.S-infected lungs exhibited higher eGFP-expressed cell percentage than others (Fig. 1). AAV8, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAV-ie,and AAV-PHP.eB-infected lungs displayed relatively lower eGFP expression cell percentage (Fig. 1). However, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, MyoAAV 4A, and AAV-7m8 infected lungs showed rare or no eGFP-expressed cells (Fig. 1). These results suggest that different AAV serotypes have varied infection ability in mouse lungs.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of infection efficiency of AAVs in the mouse lungs. The ratio of eGFP+ cells to DAPI+ cells. 2746, 695, 0, 115, 26, 2435, 0, 2588, 3118, 2919, 205, 1386, 2366, 1016, 1525, 1673, 1352, 2200, 1681, 2078 eGFP+ cells were analyzed for AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S, and 9263, 9804, 9701, 8762, 10,703, 9052, 9592, 9193, 9145, 9217, 10,157, 10,084, 10,272, 10,672, 10,330, 10,242, 9735, 10,423, 9715, 9958 DAPI+ cells, respectively. n = 3

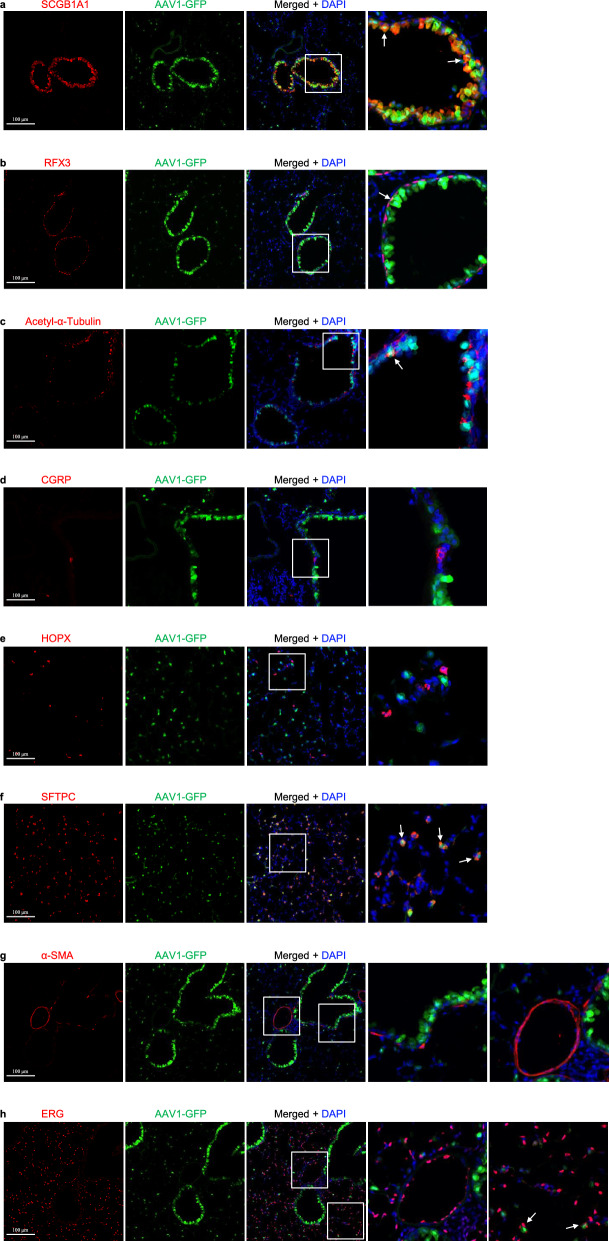

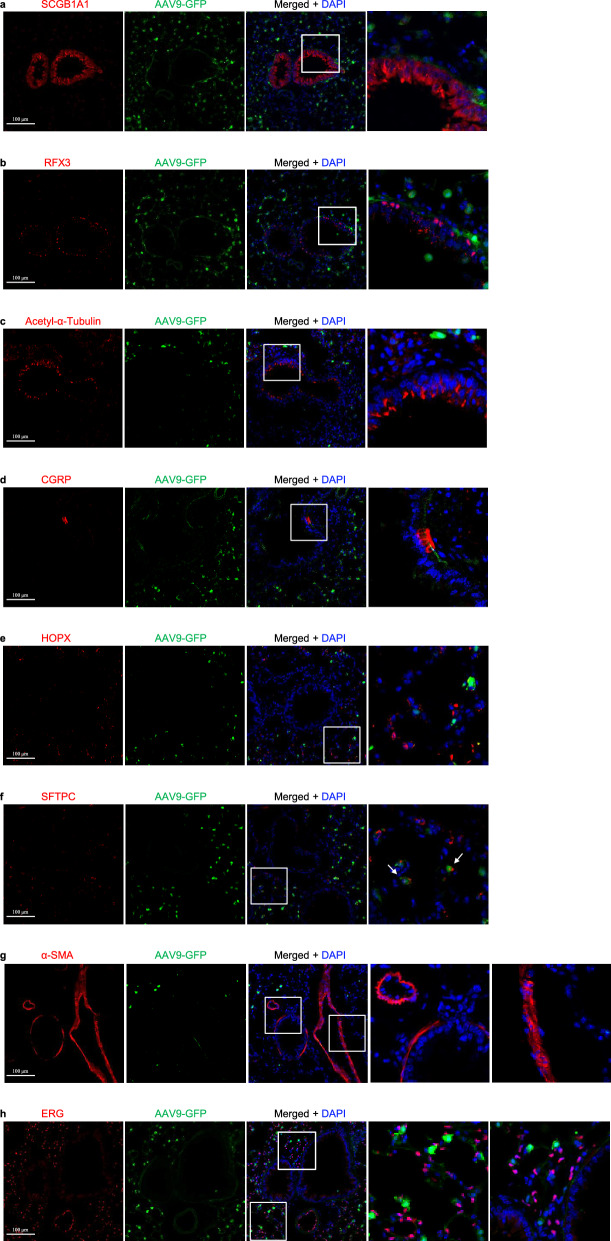

Fig. 2.

AAV1-eGFP expression in the lungs infected by AAV1 in mice. a Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SCGB1A1 (red) and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. b Immunostaining for eGFP (green), RFX3 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. c Immunostaining for eGFP (green), Acetylated-α-tubulin (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. d Immunostaining for eGFP (green), CGRP (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. e Immunostaining for eGFP (green), HOPX (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. f Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SFTPC (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. g Immunostaining for eGFP (green), α-SMA (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. h Immunostaining for eGFP (green), ERG (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. Scale bars: 100 μm

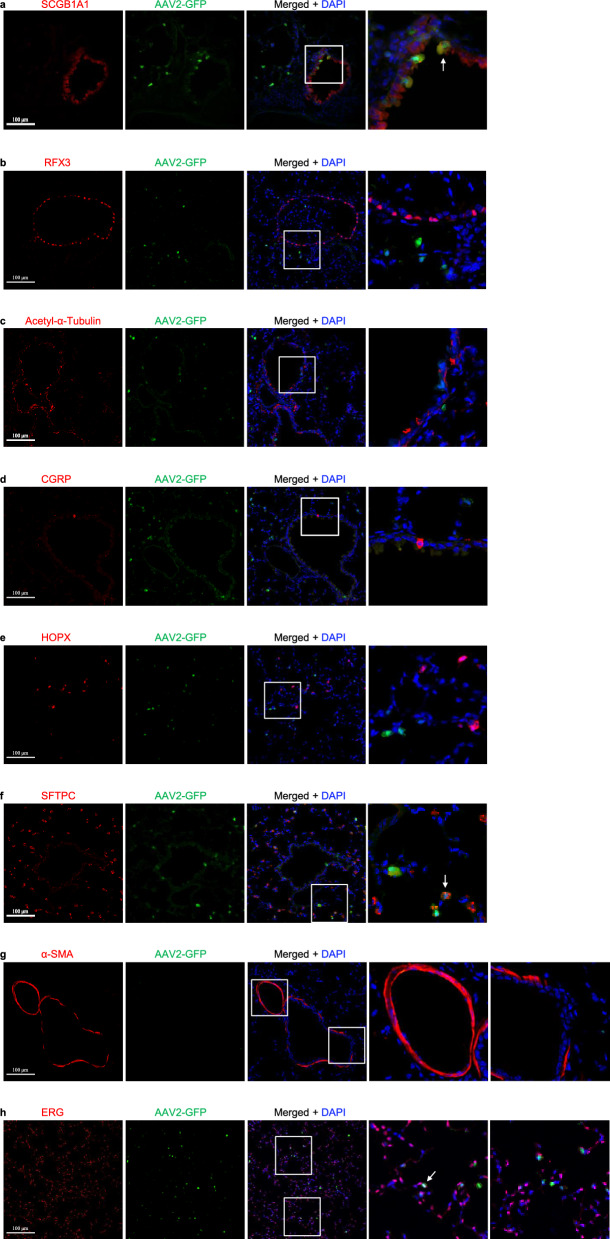

Fig. 3.

AAV2-eGFP expression in the lungs infected by AAV2 in mice. a Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SCGB1A1 (red) and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. b Immunostaining for eGFP (green), RFX3 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. c Immunostaining for eGFP (green), Acetylated-α-tubulin (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. d Immunostaining for eGFP (green), CGRP (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. e Immunostaining for eGFP (green), HOPX (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. f Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SFTPC (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. g Immunostaining for eGFP (green), α-SMA (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. h Immunostaining for eGFP (green), ERG (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV2-eGFP. Scale bars: 100 μm

Fig. 4.

AAV3b-eGFP expression in the lungs infected by AAV3b in mice. a Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SCGB1A1 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. b Immunostaining for eGFP (green), RFX3 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. c Immunostaining for eGFP (green), Acetylated-α-tubulin (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. d Immunostaining for eGFP (green), CGRP (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. e Immunostaining for eGFP (green), HOPX (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. f Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SFTPC (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. g Immunostaining for eGFP (green), α-SMA (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. h Immunostaining for eGFP (green), ERG (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV3b-eGFP. Scale bars: 100 μm

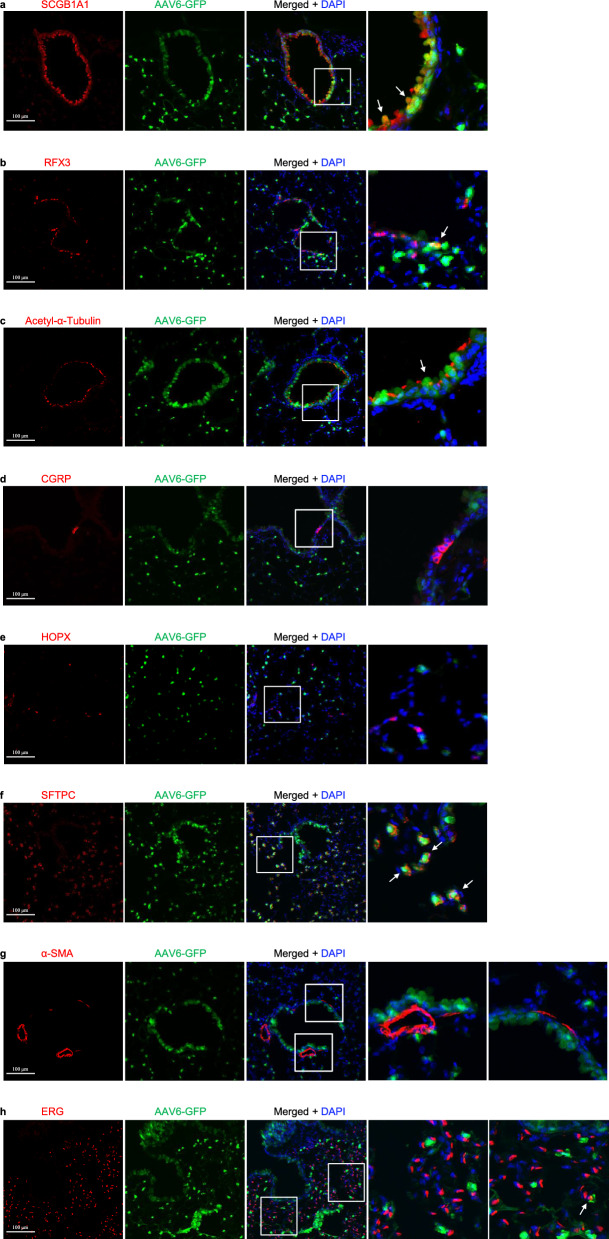

Fig. 5.

AAV6-eGFP expression in the lungs infected by AAV6 in mice. a Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SCGB1A1 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV6-eGFP. b Immunostaining for eGFP (green), RFX3 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV6-eGFP. c Immunostaining for eGFP (green), acetylated-α-tubulin (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV6-eGFP. d Immunostaining for eGFP (green), CGRP (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV6-eGFP. e Immunostaining for eGFP (green), HOPX (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV6-eGFP. f Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SFTPC (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV6-eGFP. g Immunostaining for eGFP (green), α-SMA (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV1-eGFP. h Immunostaining for eGFP (green), ERG (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV6-eGFP. Scale bars: 100 μm

Fig. 6.

AAV8-eGFP expression in the lungs infected by AAV8 in mice. a Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SCGB1A1 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. b Immunostaining for eGFP (green), RFX3 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. c Immunostaining for eGFP (green), Acetylated-α-tubulin (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. d Immunostaining for eGFP (green), CGRP (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. e Immunostaining for eGFP (green), HOPX (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. f Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SFTPC (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. g Immunostaining for eGFP (green), α-SMA (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. h Immunostaining for eGFP (green), ERG (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV8-eGFP. Scale bars: 100 μm

Fig. 7.

AAV9-eGFP expression in the lungs infected by AAV9 in mice. a Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SCGB1A1 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. b Immunostaining for eGFP (green), RFX3 (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. c Immunostaining for eGFP (green), Acetylated-α-tubulin (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. d Immunostaining for eGFP (green), CGRP (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. e Immunostaining for eGFP (green), HOPX (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. f Immunostaining for eGFP (green), SFTPC (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. g Immunostaining for eGFP (green), α-SMA (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. h Immunostaining for eGFP (green), ERG (red), and DAPI staining (blue) of 2-month-old mouse lungs infected with AAV9-eGFP. Scale bars: 100 μm

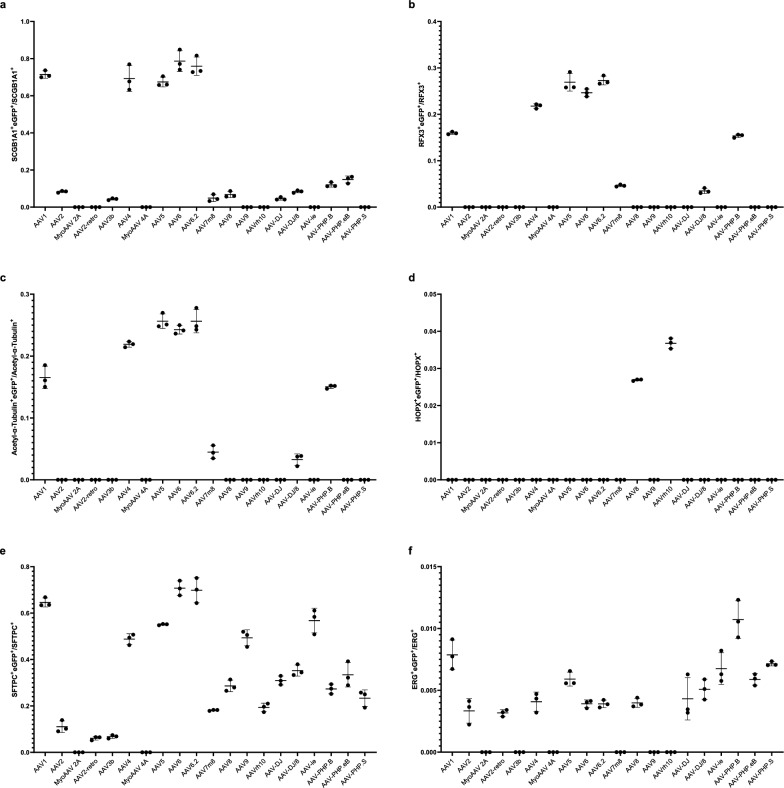

AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6 and AAV6.2 highly transduce airway epithelial club cells

The respiratory epithelium comprises several epithelial cell types, mainly including club cells, ciliated cells, and neuroendocrine cells in the conducting airway, and alveolar type I (ATI) cells and alveolar type II (ATII) cells in the alveoli. Stromal cells mainly include smooth muscle cells, vascular endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. To investigate which cell type(s) can be infected by each AAV in the lungs, we carried out double immunofluorescence staining by using antibodies of SCGB1A1 (a marker of club cells), RFX3 and acetylated-α-tubulin+ (markers of ciliated cells), CGRP (a marker of neuroendocrine cells), HOPX (a marker of ATI cells), SFTPC (a marker of ATII cells), ERG (a marker of endothelial cells) and α-SMA (a marker of smooth muscle cells) with the eGFP antibody, respectively. First, we examined which AAV infects club cells using SCGB1A1 and eGFP antibody immunofluorescence stainingand observed that eGFP was highly expressed in club cells after infection by several AAVs, including AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, and AAV6.2. The percentage of club cells with eGFP expression in these AAV infections was 71.17% for AAV1 (Fig. 2a and Fig. 8a), 8.29% for AAV2 (Fig. 3a and Fig. 8a), 70.87% for AAV4 (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Fig. 8a), 67.43% for AAV5 (Supplementary Fig. 5a and Fig. 8a), 79.05% for AAV6 (Fig. 5a and Fig. 8a), 76.16% for AAV6.2 (Supplementary Fig. 6a and Fig. 8a), 4.98% for AAV7m8 (Supplementary Fig. 7a and Fig. 8a), 6.86% for AAV8 (Fig. 6a and Fig. 8a), 4.86% for AAV-DJ (Supplementary Fig. 9a and Fig. 8a), 8.59% for AAV-DJ/8 (Supplementary. Fig. 10a and Fig. 8a), 11.97% for AAV-PHP.B (Supplementary Fig. 12a and Fig. 8a) and 14.91% for AAV-PHP.eB (Supplementary Fig. 13a and Fig. 8a), respectively. These results suggest that AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, and AAV6.2 might be more efficient tools for gene delivery into airway club cells.

Fig. 8.

Quantification of pulmonary epithelial cells that are infected by AAVs. a Ratio of SCGB1A1+ cells that are eGFP+. 1754, 260, 0, 0, 94, 1308, 0, 1282, 1240, 1470, 74, 126, 0, 0, 126, 254, 0, 276, 366, 0 for eGFP+SCGB1A1+cells were analyzed for AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S, and 2456, 3116, 2478, 2856, 2094, 1904, 2226, 1904, 1586, 1932, 1724, 1940, 1204, 1372, 2824, 2996, 1778, 2300, 2460, 1736 for SCGB1A1+ cells, respectively. n = 3. b Ratio of RFX3+ cells that are eGFP+. 612, 0, 0, 0, 0, 496, 0, 802, 448, 634, 178, 0, 0, 0, 0, 176, 0, 712, 0, 0 for RFX3+eGFP+ cells were analyzed for AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S, and 3838, 3808, 5224, 5976, 6526, 2280, 4572, 2978, 1818, 2328, 3848, 2734, 2602, 2800, 4156, 5136, 3778, 4634, 4940, 4376 for RFX3+ cells, respectively. n = 3. c Ratio of Acetyl-α-Tubulin+ cells that are eGFP+.778, 0, 0, 0, 0, 642, 0, 822, 562, 666, 174, 0, 0, 0, 0, 178, 0, 616, 0, 0 for Acetyl-α-Tubulin+eGFP+ cells were analyzed for AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S, and 4704, 4590, 6018, 6834, 8024, 2930, 5508, 3204, 2320, 2634, 3974, 3672, 5916, 5032, 5270, 5780, 4216, 4090, 4046, 5678 for Acetyl-α-Tubulin+ cells, respectively. n = 3. d Ratio of HOPX+ cells that are eGFP+. 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 78, 0, 132, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 for HOPX+eGFP+ cells were analyzed for AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S, and 1470, 3780, 2478, 3136, 3234, 2828, 2226, 4074, 2996, 3052, 3780, 2898, 2772, 3606, 3262, 2142, 1778, 1148, 1890, 1302 for HOPX+ cells, respectively. n = 3. e Ratio of SFTPC+ cells that are eGFP+. 1020, 408, 0, 252, 444, 766, 0, 2242, 2534, 2330, 1668, 1512, 1054, 1040, 950, 1144, 2142, 662, 860, 490 for SFTPC+eGFP+ cells were analyzed for AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S, and 1586, 3782, 2478, 4250, 6468, 1568, 2226, 4070, 3582, 3348, 9194, 5282, 5366, 5340, 3070, 3260, 3728, 2436, 2600, 2120 for SFTPC+ cells, respectively. n = 3. f Ratio of ERG+ cells that are eGFP+. 66, 58, 0, 72, 0, 52, 0, 96, 98, 76, 0, 78, 0, 0, 76, 76, 114, 122, 64, 70 for ERG+eGFP+ cells were analyzed for AAV1, AAV2, MyoAAV 2A, AAV2-retro, AAV3b, AAV4, MyoAAV 4A, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S, and 8364, 19,142, 10,392, 22,746, 13,582, 12,748, 9490, 16,240, 26,052, 19,534, 11,782, 20,028, 8488, 8262, 16,880, 14,944, 15,482, 11,352, 10,870, 9828 for ERG+ cells, respectively. n = 3

AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2 and AAV-PHP.B highly transduce ciliated cells in the airway

Next, we examined which AAV infects airway-ciliated cells using RXF3/Acetylated-α-Tubulin (Supplementary Fig. 15a) and eGFP antibody immunofluorescence staining. We observed that eGFP was highly expressed in ciliated cells after infection by several AAVs, including AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, and AAV-PHP.B. The percentage of RXF3+ ciliated cells that expressed eGFP in these AAV infections was 16.08% for AAV1 (Fig. 2b and Fig. 8b), 22.21% for AAV4 (Supplementary Fig. 3b and Fig. 8b), 26.78% for AAV5 (Supplementary Fig. 5b and Fig. 8b), 24.60% for AAV6 (Fig. 5b and Fig. 8b), 27.09% for AAV6.2 (Supplementary. Figure 6b and Fig. 8b), 4.65% for AAV7m8 (Supplementary Fig. 7b and Fig. 8b), 3.58% for AAV-DJ/8 (Supplementary Fig. 10b and Fig. 8b) and 15.49% for AAV-PHP.B (Supplementary Fig. 12b and Fig. 8b), respectively. Consistently, the percentage of Acetylated-α-Tubulin+ ciliated cells that expressed eGFP in these AAV infections was 16.64% for AAV1 (Fig. 2c and Fig. 8c), 22.17% for AAV4 (Supplementary Fig. 3c and Fig. 8c), 25.89% for AAV5 (Supplementary Fig. 5c and Fig. 8c), 24.30% for AAV6 (Fig. 5c and Fig. 8c), 26.46% for AAV6.2 (Supplementary Fig. 6c and Fig. 8c), 4.67% for AAV7m8 (Supplementary Fig. 7c and Fig. 8c), 3.62% for AAV-DJ/8 (Supplementary Fig. 10c and Fig. 8c) and 15.47% for AAV-PHP.B (Supplementary Fig. 12c and Fig. 8c), respectively. These results suggest that AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, and AAV6.2 may be more efficient tools for gene delivery into airway ciliated cells.

AAVs barely infect neuroendocrine cells

Subsequently, we examined which AAV infects neuroendocrine cells using CGRP and eGFP antibody immunofluorescence staining. We observed that almost no eGFP was expressed in neuroendocrine cells after infection by several AAVs (Figs. 2d, 3d, 4d, 5d, 6d, 7d and Supplementary Fig. 1d–19d). These results suggest that these current AAVs are unsuitable for gene delivery into airway neuroendocrine cells.

AAV8 and AAVrh10 lowly infect alveolar type I cells

Furthermore, we examined which AAV infects alveolar type I (ATI) cells using HOPX and eGFP antibody immunofluorescence staining. We observed that eGFP was highly expressed in a few ATI cells after infection by several AAVs, including AAV8 and AAVrh10. The percentage of ATI cells that expressed eGFP in these AAV infections is very low (Fig. 8d).

AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, and AAV-PHP.S highly infect alveolar type II cells

Additionally, we examined which AAV infects alveolar type II (ATII) cells using SFTPC and eGFP antibody immunofluorescence staining. We observed that eGFP was highly expressed in ATII cells after infection by several AAVs including AAV1, AAV2, AAV2-retro, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, and AAV-PHP.S. The percentage of ATII cells that expressed eGFP in these AAV infections was: 64.85% for AAV1 (Fig. 2f and Fig. 8e), 11.26% for AAV2 (Fig. 3f and Fig. 8e), 6.18% for AAV2-retro (Supplementary Fig. 2f and Fig. 8e), 49.12% for AAV4 (Supplementary Fig. 3f and Fig. 8e), 55.04% for AAV5 (Supplementary Fig. 5f and Fig. 8e), 70.93% for AAV6 (Fig. 5f and Fig. 8e), 69.85% for AAV6.2 (Supplementary Fig. 6f and Fig. 8e), 18.14% for AAV7m8 (Supplementary Fig. 7f and Fig. 8e), 28.54% for AAV8 (Fig. 6f and Fig. 8e), 19.79% for AAV9 (Fig. 7f and Fig. 8e), 19.32% for AAVrh10 (Supplementary Fig. 8f and Fig. 8e), 30.91% for AAV-DJ (Supplementary Fig. 9f and Fig. 8e), 35.26% for AAV-DJ/8 (Supplementary Fig. 10f and Fig. 8e), 56.73% for AAVie (Supplementary Fig. 11f and Fig. 8e), 28.35% for AAV-PHP.B (Supplementary Fig. 12f and Fig. 8e), 35.04% for AAV-PHP.eB (Supplementary Fig. 13f and Fig. 8e) and 24.68% for AAV-PHP.S (Supplementary Fig. 14f and Fig. 8e), respectively. These results suggest that AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV7m8, AAV8, AAV9, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, and AAV-PHP.S may be more efficient delivery tools for gene delivery into ATII cells in the lungs.

AAVs rarely infect airway smooth muscle

Moreover, we examined which AAV infects airway smooth muscle cells using α-SMA and eGFP antibody immunofluorescence staining. We observed that almost no eGFP was expressed in airway smooth muscle cells after infection by several AAVs (Figs. 2g, 3g, 4g, 5g, 6g, 7g and Supplementary Figs. 1 g–19 g). These results suggest that these current AAVs may be not efficient gene delivery tools for airway smooth muscle.

Several AAVs exhibit very low infection efficiency in pulmonary endothelial cells

Afterwards, we examined which AAV infects the lung endothelium using ERG and eGFP antibody immunofluorescence staining. We observed that eGFP was highly expressed in a few lung endothelial cells after infection by several AAVs, including AAV1, AAV2, AAV2-reteo, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV8, AAV-DJ, AAV-DJ/8, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB and AAV-PHP.S. The percentage of lung endothelial cells that expressed eGFP in these AAV infections was 0.78% for AAV1 (Fig. 2h and Fig. 8f), 0.34% for AAV2 (Fig. 3h and Fig. 8f), 0.31% for AAV2-retro (Supplementary Fig. 2h and Fig. 8f), 0.41% for AAV4 (Supplementary Fig. 3h and Fig. 8f), 0.59% for AAV5 (Supplementary Fig. 5 h and Fig. 8f), 0.40% for AAV6 (Fig. 5h and Fig. 8f), 0.39% for AAV6.2 (Supplementary Fig. 6 h and Fig. 8f), 0.40% for AAV8 (Fig. 6h and Fig. 8f), 0.42% for AAV-DJ (Supplementary Fig. 9 h and Fig. 8f), 0.54% for AAV-DJ/8 (Supplementary Fig. 10 h and Fig. 8f), 0.70% for AAVie (Supplementary Fig. 11 h and Fig. 8f), 1.05% for AAV-PHP.B (Supplementary Fig. 12 h and Fig. 8f), 0.59% for AAV-PHP.eB (Supplementary Fig. 13 h and Fig. 8f) and 0.74% for AAV-PHP.S (Supplementary Fig. 14 h and Fig. 8f), respectively. These results suggest that these current AAVs are inefficient for gene delivery into the lung endothelium.

Discussion

AAV vectors have attracted significant attention due to the lack of pathogenicity, low immunogenicity and toxicity, and long-term transgene expression [21–23]. Given the importance of AAVs in gene therapies, especially their great potential application in pulmonary diseases, it is important to understand which specific cell type(s) AAVs can efficiently infect the lungs. Our systematic analysis of pulmonary infection rates and tropism of twenty commercial serotypes of AAVs in mice suggests that different AAVs have distinct infection characteristics. For gene delivery in the mouse model, it will be necessary to consider which AAV(s) is a suitable choice depending on which cell type(s) to infect and how many gene levels to express. This study found that AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, and AAV6.2 exhibit high infection in club cells. AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, and AAV-PHP.B efficiently infect ciliated cells. AAV1, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV9, and AAVie can highly infect alveolar type II cells. Notably, AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh10 show more specific infection in alveolar type II cells. Considering that gene mutations can affect lung epithelial cell function. For example, some patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) or pulmonary fibrosis carries gene mutations, affecting the function of ciliated cells or alveolar type II cells. It is thus possible that AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, and AAV-PHP.B are more suitable for gene delivery into airway epithelial cells, especially ciliated cells, for potential gene therapy of PCD. AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh10 may be more suitable for specific gene delivery into alveolar type II cells for a potential gene therapy of pulmonary fibrosis. These gene therapies may promote cilia beating to facilitate mucus clearance in PCD or reduce fibrosis progression in pulmonary fibrosis. However, we have not identified AAVs that specifically infect airway smooth muscle or neuroendocrine cells in the lungs. Considering the need for precise gene delivery into specific cell type(s) in gene therapies in pulmonary diseases, it remains necessary to develop novel AAV serotypes with cell-type specific infections in the future.

Several pulmonary diseases show dysfunction of stromal cells [24]. For example, patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) exhibit impaired vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells [25]. Asthmatic patients show thickened airway smooth muscle (ASM) layers caused by airway smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia [26]. Genetic studies have shown that mutations of several genes are associated with or contribute to the development of PAH [27]. It is thus possible to use AAV-mediated gene editing for PAH intervention. However, we have not identified any AAV serotype that can highly infect smooth muscle or endothelial cells. It will be necessary to generate AAV(s) that can efficiently infect these lung stromal cells for future studies of gene therapies of these pulmonary diseases.

Several AAV serotypes in mice exhibit high infection in respiratory epithelium in our analysis. However, it should be emphasized that these serotypes may not behave similarly in the human lungs. Previous studies show that AAV serotypes exhibit species-specific differences in airway epithelial cell transduction efficiencies between mice and humans, possibly due to differences in their airway biology [19]. In order to accurately imitate tropisms for these AAV serotypes in the human lungs for the development of AAV-mediated gene therapies, it will be necessary to evaluate pulmonary infections of AAV serotypes in human lung organoids in vitro and in other animal models such as non-human primate models in vivo. The structure and cell types of the lungs in pigs and ferrets are more similar to those of humans compared with mice [28]. Interestingly, cystic fibrosis models have been developed in pigs and ferrets, which places these models in a special position for the development of gene therapies for cystic fibrosis using AAV vector-mediated gene delivery [29, 30]. It remains interesting also to examine airway infections in these cystic fibrosis models using these AAVs, which can highly infect the airway epithelium identified in our study. Moreover, since patients with COPD, asthma, or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis also show pulmonary epithelial cell dysfunction or injury, it will be also worth testing epithelial cell infection of AAVs in animal models of these diseases.

AAV delivery via intratracheal instillation has several advantages over systemic injection through the tail vein. First, AAV intratracheal instillation makes it directly target cells in the respiratory tract, which enhances its tissue-specific infection and reduces its nonspecific transportation in the body. This local AAV delivery can also reduce the amount of AAV used for gene therapy compared with systemic injection. Second, intratracheal instillation may be a safer way of performing AAV-mediated gene therapy for pulmonary diseases. It may reduce potential damage to the vasculature system and cause less immune responses. Third, intratracheal instillation may be more efficient for AAV delivery into the lungs, as these delivered AAVs directly contact the lung cells without being diluted by the blood.

Altogether, this study offers a systematic analysis of the tropism of AAVs in the lungs of mice, which may help generate effective AAV-mediated gene therapy strategies for treating lung diseases.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Yonghua Wei and Hongsheng Chen for imaging assistance.

Author contributions

W.Y. initiated and supervised the whole project. H.W., A.Z., W.Y. and H.L. performed experiments and data analysis. H.L., Y.B., Y.Z. and D.Y. performed data analysis. H.W. and W.Y. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970019, 82160008), R&D Program of Guangzhou Laboratory (GZNL2024A02005, SRPG22-016 and SRPG22-021), Open Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering, Fudan University (No. SKLGE-2305) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (2023GXNSFAA026454).

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to this publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aneja MK, Geiger JP, Himmel A, Rudolph C. Targeted gene delivery to the lung. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:567–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikeda Y, Sun Z, Ru X, Vandenberghe LH, Humphreys BD. Efficient gene transfer to kidney mesenchymal cells using a synthetic adeno-associated viral vector. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:2287–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen H, Durinck S, Patel H, Foreman O, Mesh K, Eastham J, Caothien R, Newman RJ, Roose-Girma M, Darmanis S, Warming S, Lattanzi A, Liang Y, Haley B. Population-wide gene disruption in the murine lung epithelium via AAV-mediated delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022;27:431–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz M, Levy DI, Petropoulos CJ, Bashirians G, Winburn I, Mahn M, Somanathan S, Cheng SH, Byrne BJ. Binding and neutralizing anti-AAV antibodies: detection and implications for rAAV-mediated gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2023;31:616–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challis RC, Ravindra Kumar S, Chan KY, Challis C, Beadle K, Jang MJ, Kim HM, Rajendran PS, Tompkins JD, Shivkumar K, Deverman BE, Gradinaru V. Systemic AAV vectors for widespread and targeted gene delivery in rodents. Nat Protoc. 2019;14:379–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He X, Zhang Z, Xue J, Wang Y, Zhang S, Wei J, Zhang C, Wang J, Urip BA, Ngan CC, Sun J, Li Y, Lu Z, Zhao H, Pei D, Li CK, Feng B. Low-dose AAV-CRISPR-mediated liver-specific knock-in restored hemostasis in neonatal hemophilia B mice with subtle antibody response. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickles RJ. Physical and biological barriers to viral vector-mediated delivery of genes to the airway epithelium. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu CJ, Chen LC, Huang WC, Chuang CL, Kuo ML. Alleviation of lung inflammatory responses by adeno-associated virus 2/9 vector carrying CC10 in OVA-sensitized mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2013;24:48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santiago-Ortiz JL, Schaffer DV. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors in cancer gene therapy. J Control Release. 2016;240:287–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zabaleta N, Dai W, Bhatt U, Herate C, Maisonnasse P, Chichester JA, Sanmiguel J, Estelien R, Michalson KT, Diop C, Maciorowski D, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Cavarelli M, Gallouet AS, Naninck T, Kahlaoui N, Lemaitre J, Qi W, Hudspeth E, Cucalon A, Dyer CD, Pampena MB, Knox JJ, LaRocque RC, Charles RC, Li D, Kim M, Sheridan A, Storm N, Johnson RI, Feldman J, Hauser BM, Contreras V, Marlin R, Tsong Fang RH, Chapon C, van der Werf S, Zinn E, Ryan A, Kobayashi DT, Chauhan R, McGlynn M, Ryan ET, Schmidt AG, Price B, Honko A, Griffiths A, Yaghmour S, Hodge R, Betts MR, Freeman MW, Wilson JM, Le Grand R, Vandenberghe LH. An AAV-based, room-temperature-stable, single-dose COVID-19 vaccine provides durable immunogenicity and protection in non-human primates. Cell Host Microb. 2021;29(1437–53): e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan Z, Keiser NW, Song Y, Deng X, Cheng F, Qiu J, Engelhardt JF. A novel chimeric adenoassociated virus 2/human bocavirus 1 parvovirus vector efficiently transduces human airway epithelia. Mol Ther. 2013;21:2181–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Z, Feng Z, Sun X, Zhang Y, Zou W, Wang Z, Jensen-Cody C, Liang B, Park S-Y, Qiu J, Engelhardt JF. Human bocavirus type-1 capsid facilitates the transduction of ferret airways by adeno-associated virus genomes. Hum Gene Ther. 2017;28:612–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopes-Pacheco M, Kitoko JZ, Morales MM, Petrs-Silva H, Rocco PRM. Self-complementary and tyrosine-mutant rAAV vectors enhance transduction in cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2018;372:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zabner J, Seiler M, Walters R, Kotin RM, Fulgeras W, Davidson BL, Chiorini JA. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surfaces of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer. J Virol. 2000;74:3852–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbert CL, Allen JM, Miller AD. Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of AAV2 vectors. J Virol. 2001;75:6615–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell CL, Vandenberghe LH, Bell P, Limberis MP, Gao GP, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. The AAV9 receptor and its modification to improve in vivo lung gene transfer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2427–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlon M, Toelen J, Van der Perren A, Vandenberghe LH, Reumers V, Sbragia L, Gijsbers R, Baekelandt V, Himmelreich U, Wilson JM, Deprest J, Debyser Z. Efficient gene transfer into the mouse lung by fetal intratracheal injection of rAAV2/6.2. Mol Ther. 2010;18:2130–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Luo M, Guo C, Yan Z, Wang Y, Engelhardt JF. Comparative biology of rAAV transduction in ferret, pig and human airway epithelia. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1543–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Yan Z, Luo M, Engelhardt JF. Species-specific differences in mouse and human airway epithelial biology of recombinant adeno-associated virus transduction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin W, Liontos A, Koepke J, Ghoul M, Mazzocchi L, Liu X, Lu C, Wu H, Fysikopoulos A, Sountoulidis A, Seeger W, Ruppert C, Gunther A, Stainier DYR, Samakovlis C. An essential function for autocrine hedgehog signaling in epithelial proliferation and differentiation in the trachea. Development. 2022;149(3):dev199804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verdera HC, Kuranda K, Mingozzi F. AAV vector immunogenicity in humans: a long journey to successful gene transfer. Mol Ther. 2020;28:723–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Challis RC, Ravindra Kumar S, Chen X, Goertsen D, Coughlin GM, Hori AM, Chuapoco MR, Otis TS, Miles TF, Gradinaru V. Adeno-associated virus toolkit to target diverse brain cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2022;45:447–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabatino DE, Bushman FD, Chandler RJ, Crystal RG, Davidson BL, Dolmetsch R, Eggan KC, Gao G, Gil-Farina I, Kay MA, McCarty DM, Montini E, Ndu A, Yuan J, American Society of G, Cell Therapy Working Group on AAVI. Evaluating the state of the science for adeno-associated virus integration: an integrated perspective. Mol Ther. 2022;30:2646–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West J, Fagan K, Steudel W, Fouty B, Lane K, Harral J, Hoedt-Miller M, Tada Y, Ozimek J, Tuder R, Rodman DM. Pulmonary hypertension in transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative BMPRII gene in smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2004;94:1109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lechartier B, Berrebeh N, Huertas A, Humbert M, Guignabert C, Tu L. Phenotypic diversity of vascular smooth muscle cells in pulmonary arterial hypertension: implications for therapy. Chest. 2022;161:219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James A, Mauad T, Abramson M, Green F. Airway smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:568 (author reply 9). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrell NW, Aldred MA, Chung WK, Elliott CG, Nichols WC, Soubrier F, Trembath RC, Loyd JE. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basil MC, Cardenas-Diaz FL, Kathiriya JJ, Morley MP, Carl J, Brumwell AN, Katzen J, Slovik KJ, Babu A, Zhou S, Kremp MM, McCauley KB, Li S, Planer JD, Hussain SS, Liu X, Windmueller R, Ying Y, Stewart KM, Oyster M, Christie JD, Diamond JM, Engelhardt JF, Cantu E, Rowe SM, Kotton DN, Chapman HA, Morrisey EE. Human distal airways contain a multipotent secretory cell that can regenerate alveoli. Nature. 2022;604:120–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun X, Yan Z, Yi Y, Li Z, Lei D, Rogers CS, Chen J, Zhang Y, Welsh MJ, Leno GH, Engelhardt JF. Adeno-associated virus-targeted disruption of the CFTR gene in cloned ferrets. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1578–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogers CS, Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Ostedgaard LS, Rokhlina T, Taft PJ, Rogan MP, Pezzulo AA, Karp PH, Itani OA, Kabel AC, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Davis GJ, Hanfland RA, Smith TL, Samuel M, Wax D, Murphy CN, Rieke A, Whitworth K, Uc A, Starner TD, Brogden KA, Shilyansky J, McCray PB, Zabner J, Prather RS, Welsh MJ. Disruption of the CFTR gene produces a model of cystic fibrosis in newborn pigs. Science. 2008;321:1837–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.